Abstract

Entamoeba histolytica, an intestinal amoeba that causes dysentery and liver abscesses, acquires nutrients by engulfing bacteria in the colonic lumen and phagocytoses apoptotic cells during tissue invasion. In preliminary studies to identify ligands that stimulate amoebic phagocytosis, we used ovalbumin immobilized on latex particles as a potential negative control protein. Surprisingly, ovalbumin strongly stimulated E. histolytica particle uptake. Experiments using highly purified ovalbumin confirmed the specificity of this finding. The mechanism of particle uptake was actin-dependent, and the Entamoeba phagosome marker amoebapore A localized to ovalbumin-bead containing vacuoles. The most well described amoebic receptor is a Gal/GalNAc-specific lectin, but d-galactose had no effect on ovalbumin-stimulated phagocytosis. Ovalbumin has a single N-glycosylation site (Asn292) and is modified with oligomannose and hybrid-type oligosaccharides. We used both trifluoromethanesulfonic acid and N-glycanase to deglycosylate ovalbumin and tested the effect. Both methods substantially reduced the stimulatory effect of ovalbumin. Biotinylated ovalbumin bound the surface of fixed E. histolytica trophozoites saturably; furthermore, denatured ovalbumin and native ovalbumin both specifically inhibited ovalbumin-biotin binding, but deglycosylated ovalbumin had no effect. Collectively, these data suggest that E. histolytica has a previously unrecognized surface lectin activity that binds to carbohydrates on ovalbumin and stimulates phagocytosis.

Keywords: Entamoeba histolytica, Amoebiasis, Phagocytosis, Lectin, Ovalbumin, Deglycosylation, Trifluoromethanesulfonic acid, N-glycanase

1. Introduction

Entamoeba histolytica is the intestinal protozoan parasite that causes amoebiasis, a disease characterized by dysentery and liver abscesses (Haque et al., 2003). Phagocytosis of host erythrocytes and immune cells is a prominent pathological feature of invasive amoebiasis, and E. histolytica mutant strains defective in phagocytosis have reduced virulence in animal models of disease (Griffin, 1972; Orozco et al., 1983; Rodriguez and Orozco, 1986). Phagocytosis of bacteria, furthermore, serves as an essential source of nutrition for amoebic trophozoites in the colonic lumen (Rees et al., 1941; Jacobs, 1947; Nakamura, 1953).

Entamoeba histolytica induces host cell apoptosis using a contact-dependent mechanism, and it phagocytoses apoptotic cells more efficiently than healthy cells (Huston et al., 2000, 2003). At least two features present on the surface of apoptotic cells stimulate E. histolytica phagocytosis: phosphatidylserine, which is exposed during apoptosis and following calcium ionophore-treatment of erythrocytes, and the human serum protein C1q, which becomes concentrated on apoptotic blebs (Huston et al., 2003; Boettner et al., 2005; Teixeira et al., 2008). Induction of host cell apoptosis requires adherence that is mediated by a galactose/N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (Gal/GalNAc)-specific lectin on the amoebic surface (Petri et al., 1987; Huston et al., 2000). However, d-galactose at concentrations that almost completely inhibit amoebic adherence to and killing of host cells only inhibits phagocytosis of already apoptotic cells by approximately 40%, indicating the existence of phagocytosis receptors in addition to the Gal/GalNAc-specific lectin (Huston et al., 2003). Additional amoebic surface proteins that have been implicated in phagocytosis of host cells include a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored serine-rich E. histolytica protein (the SREHP), a 112 kDa adhesin that is comprised of two proteins and possesses proteinase activity, and a recently identified phagosome-associated transmembrane kinase (Garcia-Rivera et al., 1999; Boettner et al., 2008; Teixeira and Huston, 2008).

Here, we present data indicating that E. histolytica has at least one previously unrecognized surface lectin activity that facilitates phagocytosis. We attempted to use hen egg white albumin (ovalbumin; Ova) as a negative control protein in preliminary studies using protein-coated latex beads as targets for E. histolytica phagocytosis, and were surprised to find that Ova is a strong and specific stimulant of E. histolytica phagocytosis. Of course, there is no reason to believe that E. histolytica interacts with Ova in the human colon. However, Ova has a single N-glycosylation site (Asn292) with a heterogeneous mixture of attached neutral glycans, mostly of the unprocessed high-mannose type or partially processed hybrid variety (Man5GlcNAc2, Man5GlcNAc3, Man5GlcNAc4, and Man6GlcNAc2 collectively account for more than 60%) (Nisbet et al., 1981; Thaysen-Andersen et al., 2009). Given this and the prevalence of lectin-carbohydrate pairings that mediate host-microbe and microbe-microbe interactions, we hypothesized that E. histolytica has a surface lectin activity that facilitates phagocytosis and serendipitously recognizes carbohydrates on Ova. Consistent with this, we demonstrated that deglycosylation of Ova eliminates its ability to stimulate amoebic phagocytosis, and that labeled Ova shows saturable and specific binding to the surface of amoebic trophozoites.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (USA) unless otherwise noted. Ova (90% pure, Grade III), BSA (fraction V), d-mannose, d-maltose, d-fucose, d-lactose, d-xylose, heparin sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, porcine stomach mucin, N-acetylglucosamine, cytochalasin D and anhydrous trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TFMS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). N-glycanase (PNGaseF) was purchased from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc)-BSA was obtained from Accurate Chemicals (Westbury, NY, USA), and EndoGrade Ovalbumin (>98% pure; endotoxin concentration < 1 EU/mg)(E-Ova) was purchased from Profos AG (Regensburg, Germany). Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin was purchased from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL, USA). Streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 488 and the goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 633 antibody were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the anti-amoebapore A polyclonal rabbit IgG was a gift from Matthias Leippe (Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Kiel, Germany).

2.2. Cultivation of E. histolytica

Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites (strain HM-1:IMSS) were grown axenically in trypticase-yeast extract-iron serum (TYI-S-33) medium supplemented with 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate and 100 U/ml penicillin at 37°C as previously described (Diamond, 1978). Trophozoites were used during log-phase growth and harvested for experiments by incubation on ice for 10 min, centrifugation at 200 × g, washing twice with PBS, and resuspended in PBS.

2.3. Preparation of single-ligand fluorescent particles

Fluorescent latex particles coated with a single protein were used to examine the ability of potential protein ligands to stimulate E. histolytica phagocytosis (Teixeira et al., 2008). For this, proteins were biotinylated using Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin, dialyzed against PBS, and bound to streptavidin-coated 2 µm fluorescent latex particles (Polysciences, Inc. (Warrington, PA, USA)). The biotin-labeling reactions were conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Streptavidin-coated latex particles were then washed four times with PBS containing 1% BSA (PBS/BSA), resuspended in PBS/BSA at a concentration of 5 × 108 beads/ml, and incubated with 20 µg/ml of biotinylated protein for 30 min at 4°C. Coated particles were washed three more times with PBS/BSA prior to use.

2.4. Deglycosylation of protein ligands

Chemical deglycosylation was performed with TFMS according to the method of Edge et al. (1981). Briefly, 1 mg of endotoxin-free Ova was placed in a dry glass reaction vial and capped with a Teflon-faced seal (Thermo Scientific). Sixty µl of toluene was added to a glass ampoule containing 540 µl of anhydrous TFMS using a dry glass syringe (Hamilton) and stainless steel needle. The protein sample was cooled using a dry ice/ethanol bath for approximately 20 s, 50 µl of the TFMS/toluene mixture was added and the vial was placed in the freezer (−20°C). It was agitated at 5 and 10 min, and then incubated for 4 h at −20°C. After incubation, the vial was placed back on dry ice/ethanol and a mixture of pyridine/methanol/water (3:1:1 by volume) was added slowly. The vial was transferred to dry ice for 5 min and then wet ice for an additional 15 min, after which the reaction was stopped by addition of 400 µl of 0.5% [w/v] ammonium bicarbonate. The sample was then centrifuged (16,000 × g, 15 min, room temperature), the supernatant was removed and discarded, and the protein pellet was resuspended in PBS. Enzymatic deglycosylation was performed using PNGaseF according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For this, 600 µg of E-Ova was denatured in 0.5% SDS and 40 mM DTT for 10 min at 100°C. PNGaseF (3500 units) was added and a manufacturer supplied reaction buffer was added to achieve a final concentration of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) and 1% NP-40. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Protein integrity and deglycosylation were assessed as in section 2.5.

2.5. Protein analysis

Where indicated, protein ligands to be immobilized on single-ligand particles were analyzed for purity, integrity, success of deglycosylation and success of biotinylation. Protein ligands were resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, boiled for 5 min and separated by SDS-PAGE on 12% polyacrylamide gels (Laemmli, 1970). The effectiveness of protein deglycosylation was determined by staining gels with Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) stain (GelCode Glycoprotein Staining Kit, Pierce Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This method uses periodic acid to oxidize glycols present on glycoproteins to aldehydes, which are then revealed by treatment with a reducing reagent. After PAS staining, the purity and integrity of non-deglycosylated and degycosylated proteins were assessed by silver staining the same gel to visualize all proteins (Rabilloud, 1992). Successful biotinylation of proteins to be bound to streptavidin-coated latex particles was confirmed by immunoblotting. Following biotinylation using Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin, equal quantities of the protein ligands were separated as above by SDS-PAGE on 12% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore Corp.), blocked for 1 h at room temperature with Tris-buffered saline-1% Tween 20 (pH 7.4) containing 5% BSA, and probed overnight with a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Amersham Pharmacia). Bound streptavidin-HRP was visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia).

2.6. Phagocytosis assays

Unless otherwise noted, phagocytosis experiments were conducted in the presence of d-galactose to inhibit the amoebic Gal/GalNAc-specific surface lectin. The flow cytometry phagocytosis assay has been described elsewhere (Huston et al., 2003). Briefly, E. histolytica trophozoites in PBS with 110 mM d-galactose were mixed with single-ligand fluorescent latex beads (E. histolytica:bead = 1:10), centrifuged (200 g, 4°C, 5 min), and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. Trophozoites were then washed with an ice cold solution of PBS with 110 mM d-galactose to remove most adherent beads, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, washed again and analyzed using a Beckman Coulter EPICS XL-MCL flow cytometer and WinMDI software (version 2.9). Amoebas were distinguished from non-phagocytosed beads on the basis of forward and side scatter characteristics. Amoebas with fluorescence above background levels were considered phagocytic, and both the percentage and the mean fluorescence of positive amoebas were measured. Data are presented as representative histograms showing amoebic fluorescence, and as a calculated phagocytic index, defined as the percentage of positive amoebas times the mean fluorescence of positive amoebas (Fadok et al., 1992; Huston et al., 2003; Teixeira et al., 2008).

In some cases, phagocytosis was quantified by microscopy to verify results obtained with the flow cytometry assay. For this, fluorescent latex beads were centrifuged onto trophozoites adherent to glass coverslips (200 g for 5 min at room temperature) followed by incubation for 30 min at 37°C. The coverslips were then washed three times with 110 mM d-galactose in PBS to remove adherent beads, and inverted onto Biomeda Gel Mount medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). Phagocytosis was quantitated by a blinded observer using an epifluorescent microscope, scoring a minimum of 100 trophozoites per sample as positive or negative for phagocytosis and, if positive, counting the number of beads phagocytosed. A phagocytic index was again calculated, but here it was defined as the percentage of amoebas positive for phagocytosis times the mean number of beads phagocytosed per positive amoeba.

2.7. Immunofluorescent microscopy

Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites in TYI-S-33 medium were allowed to adhere to glass coverslips for 30 min at 37°C prior to addition of green fluorescent latex beads coated with heat-denatured E-Ova (approximately 10 beads per amoeba) and incubation for 10, 20, 40 or 60 min. The cover slips were then washed twice with warm PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, blocked with 20% goat serum/5% BSA in PBS, and stained for immunofluorescent microscopy using a rabbit polyclonal anti-amoebapore A IgG antibody (1:500 dilution) and goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 633 (1:1000 dilution)(far red; pseudocolored red). Image z-stacks with a spacing of 0.3 µm were acquired using a 60× 1.4 NA oil immersion differential interference contrast (DIC) objective, and a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with a Qimaging ExiBlue CCD camera and a motorized stage. Epifluorescent images were deconvolved using AutoQuant X (MediaCybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA) using a blind deconvolution algorithm and 30 iterations. Images were exported as TIF files, and labels were added using Adobe Illustrator software.

2.8. Binding studies

Binding assays were performed using biotinylated Ova (Ova-biotin). Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites were fixed with paraformaldehyde and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS (BSA/PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. All binding and competition assays were performed using 2×105 trophozoites in a final volume of 1 ml of PBS. Ova-biotin was added to the trophozoites at the concentrations indicated in Fig. 4A and allowed to bind for 1 h at room temperature before washing twice with BSA/PBS. Bound Ova-biotin was stained with streptavidin-Alexa 488 (1:1000 dilution in BSA/PBS) and detected by flow cytometry. For competition experiments, 565 µM Ova-biotin was mixed with the competitors indicated in Fig. 4B at 5.65 mM prior to incubation with trophozoites and measuring binding as above. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using WinMDI software (version 2.9), and specific mean fluorescence was calculated by subtraction of fluorescence measured following incubation with streptavidin-Alexa 488 alone. Curve fitting was performed using Graphpad Prism 5 software (GraphPad, Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA).

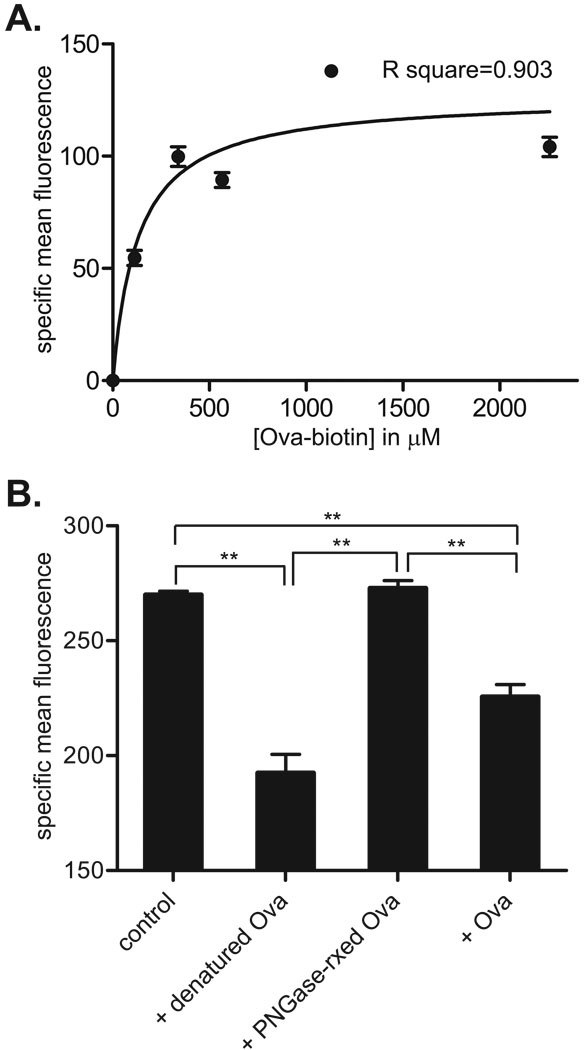

Fig. 4.

Ovalbumin (Ova) binding to the Entamoeba histolytica surface is saturable and specific. (A) Single-site-specific binding curve describing binding of the indicated concentration of Ova-biotin to 2×105 fixed E. histolytica trophozoites. Specific binding of biotin-labeled Ova was detected with streptavidin-Alexa 488 and flow cytometry. The curve was generated by least squares fit of the data to a rectangular hyperbola after subtraction of non-specific binding. Data points are specific mean fluorescence (mean and S.D., n=3). (B) Specific inhibition of Ova-biotin binding. Binding assays were performed using 2×105 fixed trophozoites and 565 µM Ova-biotin in the presence of 5.65 mM of the indicated competitor. Ova-biotin binding was significantly reduced by unlabeled Ova (+ Ova) and denatured Ova (+ denatured Ova), but PNGaseF-treated Ova (+ PNGase-rxed Ova) had no effect. Ova-biotin binding under each condition is shown as specific mean fluorescence (mean and S.D., n = 3). ** indicates P < 0.001.

2.9. Statistics

All quantitative data were expressed as the mean and S.D. rounded to two significant digits. Statistical analyses and graphs were prepared using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Significance was determined using the unpaired Student’s t test or, for experiments with multiple groups for comparison, using a one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. All data are representative of at least two independent experiments. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Ova specifically stimulates E. histolytica phagocytosis

We previously demonstrated that human C1q and the related family of collectin pattern recognition molecules stimulate E. histolytica phagocytosis and chemotaxis (Teixeira et al., 2008). In order to isolate the effect of a single ligand, biotinylated C1q and other proteins were bound to 2 µm, streptavidin-coated, fluorescent latex beads for use as target particles in E. histolytica phagocytosis assays. Preliminary experiments to identify suitable negative control proteins yielded a surprising result; E. histolytica phagocytosed beads coated with Ova with high efficiency compared with control particles. The phagocytic index for uptake of Ova-coated beads, which reflects both the percentage of amoebas engaged in phagocytosis and the relative number of fluorescent particles phagocytosed, was more than 21 times that of BSA-coated beads (phagocytic index = 89,000 ± 8600 versus 4100 ± 2000; Ova versus BSA control; means and S.D.; n = 3; P = 0.0001). Confocal microscopy was used to verify uptake of the particles by E. histolytica, ensuring that the increased amoebic fluorescence measured by flow cytometry was not due to non-phagocytosed beads adherent to the amoebic surface (data not shown; see also Fig. 2).

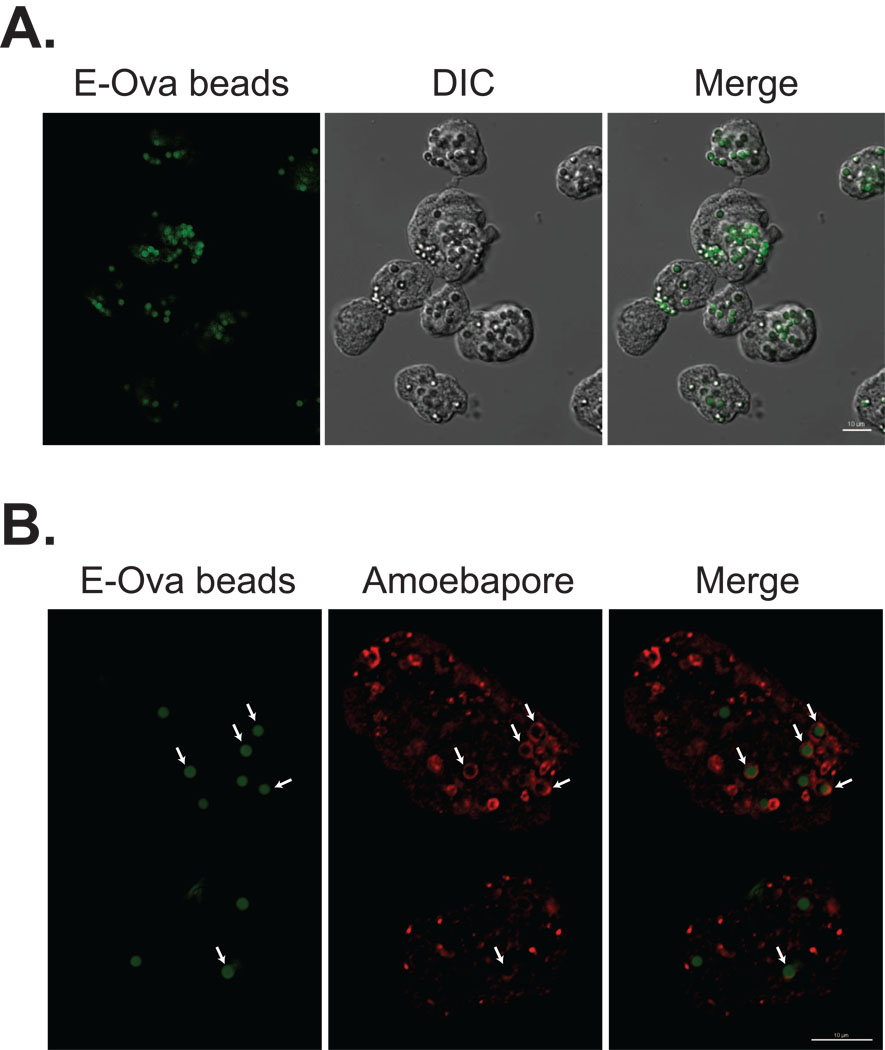

Fig. 2.

Presence of E-ovalbumin (E-Ova) beads within bona fide Entamoeba histolytica phagosomes. Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites were adhered to glass coverslips prior to addition of E-Ova-coated fluorescent beads (bead:amoeba = 10:1) and incubation for 20 min. (A) A single optical slice with E-Ova beads (green) and the corresponding differential interference contrast (DIC) image midway through multiple trophozoites is shown. Although some beads appeared to be clumped, numerous single beads were present within amoebae, excluding the possibility that the effect of Ova was simply an artifact of bead clumping or of the flow cytometry assay. (B) Localization of the phagosome marker amoebapore A to E-Ova bead containing vacuoles. Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites incubated with E-Ova-beads (green) as above were stained for immunofluorescent microscopy using a rabbit polyclonal anti-amoebapore-A IgG antibody and goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 633 (far red; pseudocolored red). A single slice midway through two trophozoites is shown (see Supplementary Fig. S1 for an orthogonal view and Supplementary Movie S1 to view the entire z-stack). Amoebapore was present within numerous E-Ova bead containing vacuoles, seen as thin circular rims surrounding the beads (arrows). Scale bars = 10 µm.

The Ova used for these initial studies was only 90% pure and contained traces of lipopolysacharide, raising the possibility that the observed effect was due to a contaminant and not due to Ova itself. Additional phagocytosis assays using beads coated with a highly purified preparation of E-Ova (>98% pure by protein; endotoxin concentration <1 EU/mg) addressed this possibility. As assessed using flow cytometry, E. histolytica trophozoites phagocytosed E-Ova-coated beads more than 16 times more efficiently than BSA-coated control beads (phagocytic index = 42,000 ± 2800 versus 2600 ± 540; E-Ova versus BSA control; means and S.D.; n = 3; P = 0.00002) (Fig. 1A). These results indicated that the observed effect was specific for Ova.

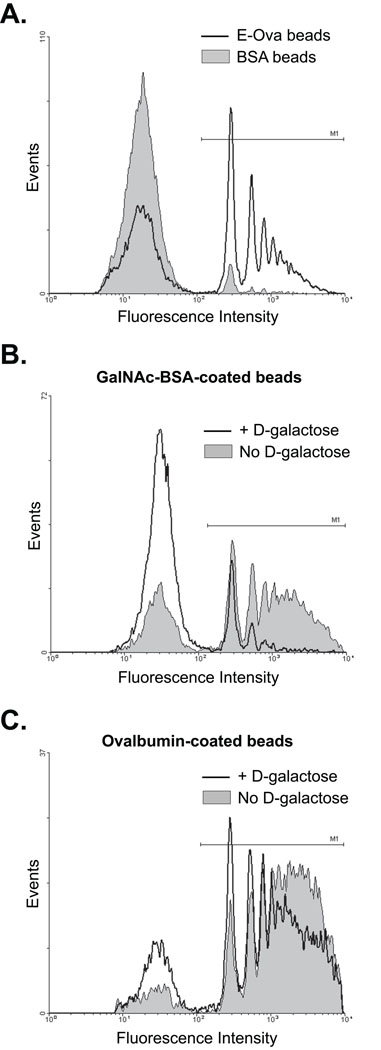

Fig. 1.

Galactose-independent Entamoeba histolytica phagocytosis of single-ligand particles coated with highly purified E-ovalbumin. Streptavidin-coated 2 µm fluorescent latex beads were coated with biotinylated E-ovalbumin (E-Ova), N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (GalNAc)-BSA or BSA as indicated and incubated with E. histolytica trophozoites. Phagocytosis was assayed using flow cytometry in the presence or absence of 110 mM d-galactose. Representative flow cytometry histograms of amoebic fluorescence are shown. In each case, the M1 gate indicates phagocytic trophozoites. (A) Specific uptake of E-Ova beads compared with BSA beads in the presence of d-galactose. (B) Effect of d-galactose on phagocytosis of GalNAc-BSA coated-beads. (C) Effect of d-galactose on phagocytosis of ovalbumin-coated beads.

As a confirmatory test, we assayed Ova-bead phagocytosis independently using an epifluorescent microscope; scoring was conducted by a blinded observer. Results from this assay were similar to those obtained with the flow cytometry assay (phagocytic index (here calculated using the method for the microscopy-based assay) = 90 ± 20 versus 2 ± 2; Ova versus BSA control; means and S.D.; n = 5; P = 0.001) (Fig. 1B). These data also eliminated the possibility that the results were due to an artifact of bead clumping. We performed a number of additional controls to ensure that uptake of Ova-coated particles was via bona fide phagocytosis. First, z-sections and image deconvolution were used to ensure that the E-Ova-coated particles were present within E. histolytica trophozoites (Fig. 2A). Although it appeared that a small error (less than 10%) could be attributed to adherence of particles to the surface of trophozoites, multiple E-Ova-coated particles were present within the majority of trophozoites. We next examined the effect of cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization. Consistent with a phagocytic mechanism of particle uptake, 10 µM cytochalasin D inhibited uptake of Ova-beads by 86 ± 4% (mean and S.D.; n = 3; P = 0.001 versus DMSO treated control). This dose of cytochalasin D inhibited phagocytosis of apoptotic Jurkat T lymphocytes to the same degree (data not shown). Finally, we co-stained for the phagosome marker amoebapore A to determine whether it was recruited to E-Ova bead-containing vacuoles. For this, trophozoites adherent to coverslips were incubated with beads coated with heat denatured E-Ova for 10, 20, 40 or 60 min prior to immunofluorescent staining and microscopy. Fig. 2B shows a 20 min time point, demonstrating a thin rim of amoebapore A surrounding numerous engulfed E-Ova beads (see also Supplementary Fig. S1 for an orthogonal view of this z-stack and Supplementary Movie S1 to pan through the z-stack). The kinetics of amoebapore A recruitment were consistent with a prior study examining E. histolytica phagocytosis of erythrocytes, with numerous vacuoles positive even at the 10 min time point (data not shown) (Saito-Nakano et al., 2004). Collectively, the data indicated that Ova is a strong and specific stimulant of E. histolytica phagocytosis.

3.2. Phagocytosis of Ova-coated particles is independent of Gal/GalNAc-specific lectin activity

The most well characterized E. histolytica receptor is a heterodimeric Gal/GalNAc-specific surface lectin which is critical for adherence to host cells and cell killing, and participates in phagocytosis (Ravdin and Guerrant, 1981; Petri et al., 1987; Huston et al., 2000, 2003). Expression of the cytoplasmic domain of the heavy subunit of this lectin reduces amoebic adherence to host cells and in vivo virulence, suggesting that it has an important signaling function (Vines et al., 1998). We examined the effect of d-galactose on phagocytosis of Ova-coated particles to determine whether Gal/GalNAc-specific lectin activity was required. Beads coated with GalNAc-BSA were used as a positive control. Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites phagocytosed GalNAc-BSA-coated beads efficiently and 110 mM d-galactose inhibited phagocytosis of GalNAc-BSA-coated beads by more than 90% (phagocytic index = 82,000 ± 8700 versus 7500 ± 610; no galactose versus with galactose; means and S.D.; n = 3; P = 0.0001) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, 110 mM d-galactose had no statistically significant effect on phagocytosis of Ova-coated beads (phagocytic index = 140,000 ± 33,000 versus 100,000 ± 17,000; no galactose versus with galactose; means and S.D.; n = 3; P = 0.14) (Fig. 1C). Although the Gal/GalNAc lectin protein may participate in phagocytosis of Ova-coated particles, these results indicated that its galactose lectin activity is not required.

3.3. Effect of soluble carbohydrates on phagocytosis of Ova-coated particles

As a first step to address the possibility that carbohydrates on Ova stimulate E. histolytica phagocytosis via interaction with a surface lectin activity with specificity other than for Gal/GalNAc, we used flow cytometry to assay the effect of a variety of readily available carbohydrates or carbohydrate containing products on phagocytosis of Ova-coated beads. As an initial screen, mono- and disaccharides were used at a concentration of 110 mM. As noted in section 3.2, this concentration of d-galactose inhibited phagocytosis of GalNAc-coated particles by approximately 90%, but had no statistically significant effect on phagocytosis of Ova-coated beads. Chondroitin sulfate, porcine stomach mucin and heparin sulfate were used at 20 mg/ml. As shown in Table 1, d-lactose, d-maltose, porcine stomach mucin and heparin sulfate all significantly reduced phagocytosis of the Ova-coated particles (P ≤ 0.01). These effects were reproducible and were not simply osmotic in nature, since not all of the carbohydrates reduced phagocytosis of the Ova-coated particles. Nevertheless, partial inhibition by so many carbohydrates at this relatively high concentration was difficult to interpret. It was not possible to test the effect of the high mannose and hybrid-type carbohydrates known to modify Ova. Given this and the confusing results, a more direct approach was needed to test whether carbohydrate modifications of Ova were the basis for its ability to stimulate E. histolytica phagocytosis.

Table 1.

Effect of selected carbohydrates on phagocytosis of ovalbumin-coated particles.

| Carbohydrate | % of trophozoites positive for phagocytosis |

Mean fluorescence of phagocytic trophozoites |

Phagocytic index |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 71 ± 2 | 2600 ± 130 | 180,000 ± 15,000 |

| d-Galactose | 73 ± 3 | 2500 ± 91 | 180,000 ± 13,000 |

| d-Mannose | 69 ± 3 | 2300 ± 170 | 160,000 ± 18,000 |

| d-Maltose | 64 ± 2 | 2000 ± 110 a | 130,000 ± 12,000 a |

| d-Fucose | 67 ± 3 | 2200 ± 130 | 150,000 ± 15,000 |

| d-Lactose | 49 ± 3 a | 2000 ± 80 a | 97,000 ± 8100 a |

| N-acetylglucosamine | 67 ± 3 | 2100 ± 110 | 140,000 ± 13,000 |

| d-Xylose | 68 ± 3 | 2200 ± 110 | 150,000 ± 13,000 |

| Heparin sulfate | 59 ± 7 | 2000 ± 110 a | 120,000 ± 20,000 a |

| Chondroitin sulfate | 68 ± 4 | 2700 ± 23 | 180,000 ± 12,000 |

| Porcine stomach mucin | 57 ± 3 a | 2100 ± 13 a | 120,000 ± 4900 a |

All mono- and disaccharides were used at 110 mM. Heparin, chondoitin sulfate and porcine stomach mucin were used at 20 mg/ml. Data are means and S.D. (n = 3).

P ≤ 0.01 compared with a no carbohydrate control.

3.4. Deglycosylation of Ova reduces uptake of Ova-coated particles

Under anhydrous conditions, TFMS removes carbohydrate modifications from proteins regardless of the type of linkage or carbohydrate. It does so without degrading the proteins themselves, though the method does denature the protein and deaminate Asn and Gln (Edge et al., 1981; Edge, 2003). We treated E-Ova with TFMS using an established protocol and confirmed successful deglycosylation of the protein by SDS-PAGE followed by PAS staining, which stains carbohydrates (Fig. 3A). Untreated E-Ova stained strongly for carbohydrates, while TFMS-treated E-Ova showed no staining. The same gel was subsequently silver stained, revealing approximately equal quantities of protein in the lanes containing untreated and TFMS-treated E-Ova. In addition, TFMS-treatment did not cause any detectable protein degradation (Fig. 3A). A slight increase in mobility consistent with removal of the carbohydrate residues further supported successful deglycosylation of the E-Ova by TFMS treatment. Prior to construction of single-ligand particles with deglycosylated Ova for use in phagocytosis assays, we confirmed successful biotinylation of both the TFMS-treated and untreated E-Ova by Western blot using streptavidin-HRP as the secondary detection reagent (data not shown). For phagocytosis assays, we also used single-ligand particles made with heat-denatured Ova to control for the possibility that differences in stimulation of phagocytosis might be due to denaturing the protein and unrelated to the removal of carbohydrate residues.

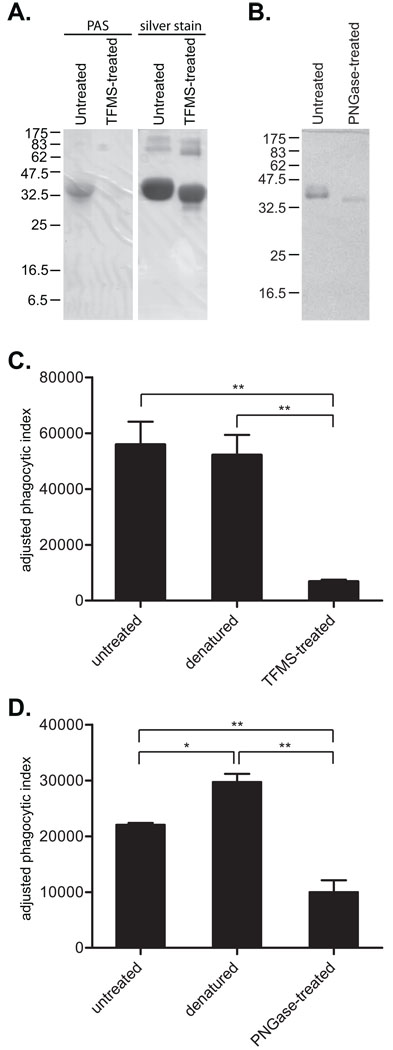

Fig. 3.

Entamoeba histolytica phagocytosis of E-ovalbumin (E-Ova)-coated beads is carbohydrate-dependent and independent of the tertiary structure of ovalbumin. (A and B) E-Ova was deglycosylated either chemically or enzymatically, biotinylated and used to coat 2 µm streptavidin-latex beads for use in phagocytosis assays. (A) Chemical deglycosylation of E-Ova using trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TFMS), with a 12% SDS-PAGE gel stained by periodic acid Schiff (PAS) to reveal carbohydrates and the same gel after silver staining to reveal all proteins. Successful degylcosylation of E-Ova by TFMS treatment was indicated by absence of PAS staining and faster migration of TFMS-treated E-Ova visualized by silver staining. (B) Enzymatic deglycosylation of E-Ova using N-glycanase (PNGaseF). A Coomassie blue stained 10% SDS-PAGE gel is shown. Successful deglycosylation was evident from the observed increase in protein mobility. (C) Entamoeba histolytica phagocytosis of single-ligand particles coated with E-Ova (untreated), heat-denatured E-Ova and TFMS-treated E-Ova. Single-ligand particles were incubated with E. histolytica trophozoites and phagocytosis was assayed using flow cytometry. (D) Entamoeba histolytica phagocytosis of single-ligand particles coated with E-Ova (untreated), E-Ova denatured with SDS, and PNGaseF-treated E-Ova For both (C) and (D), graphs show the phagocytic index adjusted by subtracting background phagocytosis of BSA-coated beads (mean and S.D., n = 3). * indicates P < 0.01 and ** indicates P < 0.001.

We next used flow cytometry to compare E. histolytica phagocytosis of beads coated with untreated E-Ova, heat-denatured E-Ova and deglycosylated E-Ova. Again, E-Ova stimulated E. histolytica phagocytosis and, importantly, heat-denatured E-Ova had an equal effect (Fig. 3C). These data suggested that the tertiary structure of Ova was not the basis for its ability to stimulate E. histolytica phagocytosis. Deglycosylation of E-Ova by TFMS-treatment, on the other hand, reduced phagocytosis by over 85% compared with beads coated with untreated E-Ova.

Because TFMS deaminates Gln and Asn in addition to removing carbohydrates, we also deglycosylated E-Ova using PNGaseF, which cleaves between the innermost GlcNAc and Asn residues of N-linked high mannose and hybrid-type carbohydrates and is much more specific. Following PNGaseF treatment, an increase in protein mobility as was seen following TFMS treatment and consistent with successful deglycosylation was readily detected by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 3B). Since successful PNGaseF treatment required denaturing E-Ova with SDS (data not shown), we constructed single-ligand beads coated with native Ova, SDS-treated Ova, and PNGaseF-treated Ova, and used those to compare phagocytosis. Similar to treatment with TFMS, PNGaseF treatment of E-Ova reduced its ability to stimulate E. histolytica phagocytosis by over 60% (Fig. 3D). In fact, Ova denatured with SDS was a significantly better stimulant than non-denatured Ova. Collectively, the data indicated that the carbohydrate modifications of Ova were the likely basis for its ability to stimulate E. histolytica phagocytosis.

3.5. E-Ova binding to the surface of E. histolytica trophozoites is saturable and specific

We conducted binding and competition experiments using Ova-biotin and 2×105 fixed E. histolytica trophozoites per condition to determine whether E. histolytica has a specific surface lectin activity that mediates phagocytosis of Ova-coated particles. Bound Ova-biotin was detected using streptavidin-Alexa 488 and flow cytometry. Specific Ova-biotin binding was readily detected at the lowest doses used and was saturable. After subtraction of non-specific binding, the binding data fit a single-site receptor-ligand binding curve, generated by least squares fit of the data to a rectangular hyperbola, with a calculated KD of 130 ± 76 µM and Bmax of 130 ± 16 (specific relative fluorescence) (Fig. 4A). In competition experiments using 565 µM Ova-biotin and unlabeled competitors at 10-fold excess, both native and denatured Ova significantly inhibited Ova-biotin binding, but PNGaseF-treated Ova had no effect (Fig. 4B). We concluded that a specific amoebic receptor binds carbohydrate modifications on Ova and facilitates phagocytosis of Ova-coated particles.

4. Discussion

This work demonstrates that E. histolytica has a previously unrecognized surface lectin activity that binds carbohydrates on Ova and facilitates phagocytosis. The serendipitous finding that the glycoprotein Ova is a strong and specific stimulant of E. histolytica phagocytosis led us to compare uptake of Ova-coated beads with uptake of beads coated with Gal/GalNAc-BSA. The data indicate that uptake of Ova-coated particles occurs via a distinct mechanism, since d-galactose at concentrations that almost completely block engulfment of GalNAc-BSA-coated beads did not significantly reduce phagocytosis of Ova-coated beads. Chemical and enzymatic deglycosylation of Ova both substantially reduced its ability to stimulate E. histolytica phagocytosis. Furthermore, binding of Ova-biotin to the surface of fixed E. histolytica trophozoites is saturable and has kinetics that fit a single-site receptor-ligand binding curve. Specificity is further indicated by the abilities of unlabeled native and denatured Ova to compete for binding, while deglycosylated Ova does not compete. Given these data, the logical conclusion is that E. histolytica has a lectin activity which recognizes carbohydrate modifications on Ova, and this activity is independent of the Gal/GalNAc-specific binding ability of the Gal/GalNAc-lectin.

Ova is the most abundant protein in hen egg white. Although it has sequence and structural homology to members of the Serine Protease Inhibitor (Serpin) protein family, Ova does not inhibit serine proteases; in fact, its exact function is unknown but it is believed to be a storage protein (reviewed in Huntington and Stein, 2001). Given this and the fact that there is no reason to believe E. histolytica interacts with Ova in nature, our first thought when we observed aggressive uptake of Ova-coated beads was that it was an artifact. Numerous control experiments confirmed the specificity of the initial observation and that uptake of Ova-coated particles occurs via genuine phagocytosis. First, to ensure that the flow cytometry assay was truly measuring particle uptake, the results were confirmed independently by microscopy and a blinded observer. Second, presence of Ova-coated particles within E. histolytica and not simply adherent to the surface of amoebae was evident from microscopy and z-sectioning. Third, uptake of Ova-coated beads required actin polymerization, since it was inhibited by cytochalasin D and, therefore, was not due to a non-actin-dependent process such as clathrin-dependent endocytosis. Fourth, recruitment of amoebapore A to E-Ova bead containing vacuoles suggested typical Entamoeba phagosome maturation. Fifth, since the same findings were replicated with highly purified Ova, it is unlikely that a contaminant in the Ova preparations is the stimulant of E. histolytica phagocytosis. Finally, heat denatured Ova stimulated E. histolytica phagocytosis and inhibited binding of labeled Ova, at least as well as native Ova, indicating that the effect is not related to the tertiary structure of Ova and further supporting the specificity of the inhibitory effect of deglycosylation.

Based on the dependence of E. histolytica on phagocytosis of bacteria for acquisition of nutrients in the colonic lumen (Rees et al., 1941; Jacobs, 1947; Nakamura, 1953), the simplest explanation for the observed stimulatory effect is that a feature of Ova-coated particles makes them resemble bacteria. Consistent with this possibility, mature Ova is 3.2% carbohydrate by weight (Nisbet et al., 1981). It has a single glycosylation site at Asn 292, and the N-glycans on Ova are either of the unmodified branched mannose variety or partially processed hybrid types.

Man5GlcNAc2, Man5GlcNAc3, Man5GlcNAc4 and Man6GlcNAc2 account for more than 60% of the total (Thaysen-Andersen et al., 2009). Although it has traditionally been held that bacteria do not glycosylate proteins, protein glycosylation in prokaryotes is now recognized to occur and N-linked branched mannose structures reminiscent of those found on Ova have been demonstrated on the surface of some bacteria (Schmidt et al., 2003; Cambi et al., 2005). We cannot completely eliminate the possibility that E. histolytica binds to something that Ova carries. This would seem unlikely, since denatured (but still glycosylated) Ova stimulated E. histolytica phagocytosis to at least the same degree that unaltered Ova did (Fig. 3). Entamoeba histolytica takes up several iron-containing proteins by endocytosis (Lopez-Soto et al., 2009a, b), and one publication suggests that Ova may function to transfer trace elements from the oviduct to the egg in the developing avian embryo (Richards and Steele, 1987). Indeed, egg white was an ingredient in early E. histolytica culture media prior to its replacement with ferrous sulfate (Diamond, 1961, 1978). However, ovotransferrin is the major iron storage protein in egg white (Williams et al., 1978), and we have found no studies that directly demonstrate that Ova chelates iron or other trace elements. Finally, in addition to glycosylation, Ova is modified by N-terminal acetylation and by two phosphorylated serines, raising the possibility that treatment with TFMS altered these modifications (Nisbet et al., 1981). Several publications have demonstrated that protein deglycosylation using TFMS has no effect on phosphoryl linkages (Lower and Kennelly, 2002; Horvath et al., 2004). Furthermore, our results were very similar using PNGaseF to deglycosylate Ova, which is a much more specific method.

The identity of the amoebic lectin activity that binds Ova remains unknown. We cannot fully exclude the possibility that the Gal/GalNAc lectin has a second lectin activity, although this in itself would be quite interesting. Our findings suggest a method for affinity purification of amoebic membrane proteins that bind heat denatured Ova, but not deglycosylated Ova. Considerable work would then be required to examine the potential role of any such receptor in E. histolytica phagocytosis of bacteria and apoptotic cells. Obviously, it would also be of interest to examine its role in other virulence-related phenotypes. The work presented here lays the groundwork for such studies.

In summary, the major conclusion of this paper is that E. histolytica has a previously unrecognized surface lectin activity that is capable of mediating phagocytosis. It is clear from previously published work that numerous receptors in addition to the well described Gal/GalNAc-specific lectin have important contributions to this virulence-associated process (Garcia-Rivera et al., 1999; Huston et al., 2003; Boettner et al., 2008; Teixeira et al., 2008; Teixeira and Huston, 2008). The data suggest a method for future identification of the receptor that binds carbohydrates present on Ova.

Supplementary Material

Orthogonal view of z-stack shown in Fig. 2, demonstrating E-ovalbumin-coated latex beads (green) within amoebapore-A containing vacuoles (far red; pseudocolored red).

Movie animation panning through the z-stack shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a student fellowship to B.T.H. from the Vermont Immunobiology and Infectious Diseases Center, USA (NIH P20 RR021905), and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, USA (NIAID R01 AI072021) to C.D.H. Microscopy and image deconvolution were made possible by NIAID ARRA supplement R01 AI072021-02S1. We are grateful to Scott Tighe at the Vermont Cancer Center’s Flow Cytometry Facility for expert advice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Note: Supplementary data associated with this article.

References

- Boettner DR, Huston CD, Sullivan JA, Petri WA. Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar utilize externalized phosphatidylserine for recognition and phagocytosis of erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:3422–3430. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3422-3430.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettner DR, Huston CD, Linford AS, Buss SN, Houpt E, Sherman NE, Petri WA. Entamoeba histolytica phagocytosis of human erythrocytes involves PATMK, a member of the transmembrane kinase family. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:122–133. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambi A, Koopman M, Figdor CG. How C-type lectins detect pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:481–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LS. Axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica. Science. 1961;134:336–337. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3475.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LS, Harlow DR, Cunnick C. A new medium for axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica and other Entamoeba. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1978;72:431–432. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(78)90144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge AS. Deglycosylation of glycoproteins with trifluoromethanesulphonic acid: elucidation of molecular structure and function. Biochem. J. 2003;376:339–350. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge ASB, Faltynek CR, Hof L, Reichert LE, Weber P. Deglycosylation of glycoproteins by trifluoromethanesulfonic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1981;118:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, Voelker DR, Campbell PA, Cohen JJ, Bratton DL, Henson PM. Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes triggers specific recognition and removal by macrophages. J. Immunol. 1992;148:2207–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rivera G, Rodriguez MA, Ocadiz R, Martinez-Lopez MC, Arroyo R, Gonzalez-Robles A, Orozco E. Entamoeba histolytica : a novel cysteine protease and an adhesin form the 112 kDa surface protein. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;33:556–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JL. Human amebic dysentery: Electron microscopy of Entamoeba histolytica contacting, ingesting, and digesting inflammatory cells. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1972;21:895–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA. Amebiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1565–1573. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath E, Edwards AM, Bell JC, Braun PE. Chemical deglycosylation on a micro-scale of membrane glycoproteins with retention of phosphoryl-protein linkages. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;24:398–401. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490240309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington JA, Stein PE. Structure and properties of ovalbumin. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 2001;756:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(01)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston CD, Houpt ER, Mann BJ, Hahn CS, Petri WA. Caspase 3-dependent killing of host cells by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Cell. Microbiol. 2000;2:617–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston CD, Boettner DR, Miller-Sims V, Petri WA. Apoptotic killing and phagocytosis of host cells by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:964–972. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.964-972.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs L. The elimination of viable bacteria from cultures of Endamoeba histolytica and the subsequent maintenance of such cultures. Am. J. Hyg. 1947;46:172–176. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Soto F, Gonzalez-Robles A, Salazar-Villatoro L, Leon-Sicairos N, Pina-Vazquez C, Salazar EP, de la Garza M. Entamoeba histolytica uses ferritin as an iron source and internalises this protein by means of clathrin-coated vesicles. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009a;39:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Soto F, Leon-Sicairos N, Reyes-Lopez M, Serrano-Luna J, Ordaz-Pichardo C, Pina-Vazquez C, Ortiz-Estrada G, de la Garza M. Use and endocytosis of iron-containing proteins by Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2009b;9:1038–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lower BH, Kennelly PJ. The membrane-associated protein-serine/threonine kinase from Sulfolobus solfataricus is a glycoprotein. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:2614–2619. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.10.2614-2619.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M. Nutrition and physiology of Endamoeba histolytica. Bacteriol. Rev. 1953;17:189–212. doi: 10.1128/br.17.3.189-212.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet AD, Saundry RH, Moir AJG, Fothergill LA, Fothergill JE. The complete amino-acid sequence of hen ovalbumin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1981;115:335–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco E, Guarneros G, Martinez-Palomo A. Entamoeba histolytica: Phagocytosis as a virulence factor. J. Exp. Med. 1983;158:1511. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.5.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri WA, Jr, Smith RD, Schlesinger PH, Murphy CF, Ravdin JI. Isolation of the galactose binding lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. J. Clin. Invest. 1987;80:1238–1244. doi: 10.1172/JCI113198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabilloud T. A comparison between low background silver diammine and silver nitrate protein stains. Electrophoresis. 1992;13:429–439. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150130190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravdin JI, Guerrant RL. Role of adherence in cytopathogenic mechanisms of Entamoeba histolytica. Study with mammalian tissue culture cells and human erythrocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 1981;68:1305–1313. doi: 10.1172/JCI110377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees CW, Reardon LV, Jacobs L. The cultivation of the parasitic protozoa without bacteria. Am. J. Trop. Med. 1941;21:695–716. [Google Scholar]

- Richards MP, Steele NC. Trace element metabolism in the developing avian embryo: a review. J. Exp. Zool. 1987 Suppl. 1:39–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MA, Orozco E. Isolation and characterization of phagocytosis- and virulence-deficient mutants of Entamoeba histolytica. J. Infect. Dis. 1986;154:27–32. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito-Nakano Y, Yasuda T, Nakada-Tsukui K, Leippe M, Nozaki T. Rab5-associated vacuoles play a unique role in phagocytosis of the enteric protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:49497–49507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MA, Riley LW, Benz I. Sweet new world: glycoproteins in bacterial pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:554–561. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira JE, Heron BT, Huston CD. C1q- and collectin-dependent phagocytosis of apoptotic host cells by the intestinal protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198:1062–1070. doi: 10.1086/591628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira JE, Huston CD. Participation of the serine-rich Entamoeba histolytica protein in amebic phagocytosis of apoptotic host cells. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:959–966. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01455-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaysen-Andersen M, Mysling S, Hørjup P. Site-specific glycoprofiling of N-linked glycopeptides using MALDI-TOF MS: strong correlation between signal strength and glycoform quantities. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:3933–3943. doi: 10.1021/ac900231w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vines RR, Ramakrishnan G, Rogers JB, Lockhart LA, Mann BJ, Petri WA., Jr Regulation of adherence and virulence by the Entamoeba histolytica lectin cytoplasmic domain, which contains a beta2 integrin motif. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:2069–2079. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Evans RW, Moreton K. The iron-binding properties of hen ovotransferrin. Biochem. J. 1978;173:533–539. doi: 10.1042/bj1730533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Orthogonal view of z-stack shown in Fig. 2, demonstrating E-ovalbumin-coated latex beads (green) within amoebapore-A containing vacuoles (far red; pseudocolored red).

Movie animation panning through the z-stack shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1.