Abstract

TET2 is a close relative of TET1, an enzyme that converts 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) in DNA1,2. The gene encoding TET2 resides at chromosome 4q24, in a region showing recurrent microdeletions and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH) in patients with diverse myeloid malignancies3. Somatic TET2 mutations are frequently observed in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), MDS/MPN overlap syndromes including chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), acute myeloid leukemias (AML) and secondary AML (sAML)4–12. We show here that TET2 mutations associated with myeloid malignancies compromise TET2 catalytic activity. Bone marrow samples from patients with TET2 mutations displayed uniformly low levels of 5-hmC in genomic DNA compared to bone marrow samples from healthy controls. Moreover, small hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated depletion of Tet2 in mouse haematopoietic precursors skewed their differentiation towards monocyte/macrophage lineages in culture. There was no significant difference in DNA methylation between bone marrow samples from patients with high 5-hmC versus healthy controls, but samples from patients with low 5-hmC showed hypomethylation relative to controls at the majority of differentially-methylated CpG sites. Our results demonstrate that TET2 is important for normal myelopoiesis, and suggest that disruption of TET2 enzymatic activity favours myeloid tumorigenesis. Measurement of 5-hmC levels in myeloid malignancies may prove valuable as a diagnostic and prognostic tool, to tailor therapies and assess responses to anti-cancer drugs.

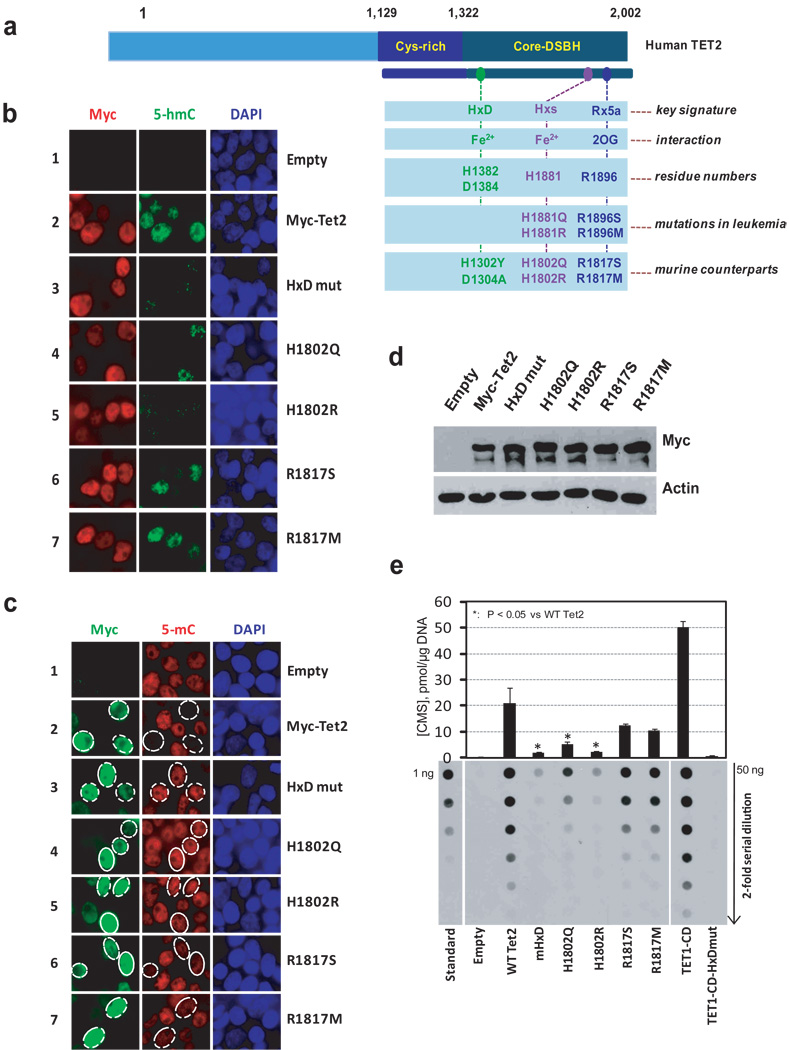

We transiently transfected HEK293T cells with Myc-tagged murine Tet2 and assessed 5-mC and 5-hmC levels by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 1, Suppl. Figs. 1–4). Myc-Tet2-expressing cells displayed a strong increase in 5-hmC staining and a concomitant decrease in 5-mC staining in the nucleus (Fig. 1b, c, quantified in Suppl. Fig. 4). In contrast, 5-hmC was undetectable or barely detected in nuclei of cells expressing mutant Tet2 with H1302Y, D1304A substitutions in the signature HxD motif1,12,17 involved in coordinating Fe2+, and there was no obvious decrease in nuclear 5-mC staining (Fig. 1b, c, Suppl. Fig. 4). These studies confirm13 that Tet2 is a catalytically active enzyme that converts 5-mC to 5-hmC in genomic DNA.

Figure 1. The catalytic activity of Tet2 is compromised by mutations in predicted catalytic residues.

a, Schematic representation of TET2. The catalytic core region contains the cysteine-rich (Cys-rich) and double-stranded beta-helix (DSBH) domains. Three signature motifs conserved among 2OG- and Fe2+-dependent dioxygenases are shown1,2. Substitutions in the HxD signature that impair the catalytic activity of TET11, leukemia-associated mutations in the C-terminal signature motifs, and corresponding substitutions introduced into murine Tet2 are indicated.

b, Tet2 expression results in increased 5-hmC by immunocytochemistry. HEK293T cells transfected with Myc-tagged wild type and mutant Tet2 were co-stained with antibody specific for the Myc epitope (red) and antiserum against 5-hmC (green). DAPI (blue) indicates nuclear staining.

c, Tet2 expression results in loss of nuclear 5-mC staining. HEK293T cells transfected with wild type and mutant Myc-tagged Tet2 were co-stained with antibody specific for the Myc epitope (green) and antiserum against 5-mC (red).

d, Equivalent expression of wild type and mutant Myc-Tet2. CD25+ cells were isolated from HEK293T cells transfected with bicistronic Tet2-IRES-human CD25 plasmids, and Tet2 expression in whole cell lysates was detected by immunoblotting with anti-Myc. β-actin serves as a loading control.

e, Genomic DNA purified from CD25+ HEK293T cells over-expressing wild type or mutant Tet2 was treated with bisulfite to convert 5-hmC to CMS (Suppl. Fig. 5a). CMS was quantified by dot blot assay using anti-CMS and a synthetic bisulphite-treated oligonucleotide containing a known amount of CMS. As positive and negative controls, we included DNA from CD25+ HEK293T cells transfected with TET1 catalytic domain (TET1-CD) or TET1-CD with mutations in the HxD motif (TET1-CD-HxDmut)1.

Mutations in TET2 residues H1881 and R1896, predicted to bind Fe2+ and 2OG, respectively, have been identified repeatedly in patients with myeloid malignancies4,5,7,10. HEK293T cells expressing Tet2 mutants H1802R and H1802Q (Fig. 1a, Suppl. Fig. 2) showed greatly diminished 5-hmC staining and no loss of 5-mC staining, consistent with participation of this residue in catalysis (Fig. 1b, c, Suppl. Fig. 4a, b). We analysed missense mutations identified in TET2 in our own (Suppl. Table S1) and other3–6, 11 studies (P1367S, W1291R, G1913D, E1318G and I1873T). HEK293T cells expressing Tet2 mutants P1287S, W1211R or C1834D (Suppl. Figs. 2, 3a) displayed low 5-hmC staining and strong 5-mC staining (Suppl. Figs. 3b, 3c, 4c, 4d), suggesting a role for these residues in the integrity of the catalytic or DNA binding domains. Cells expressing Tet2 R1817S/M (Fig. 1a, Suppl. Figs. 2, 3a) were positive for 5-hmC staining but changes in 5-mC staining could not be reliably assessed (Figs. 1b,c, Suppl. Figs. 3b, 3c, 4).

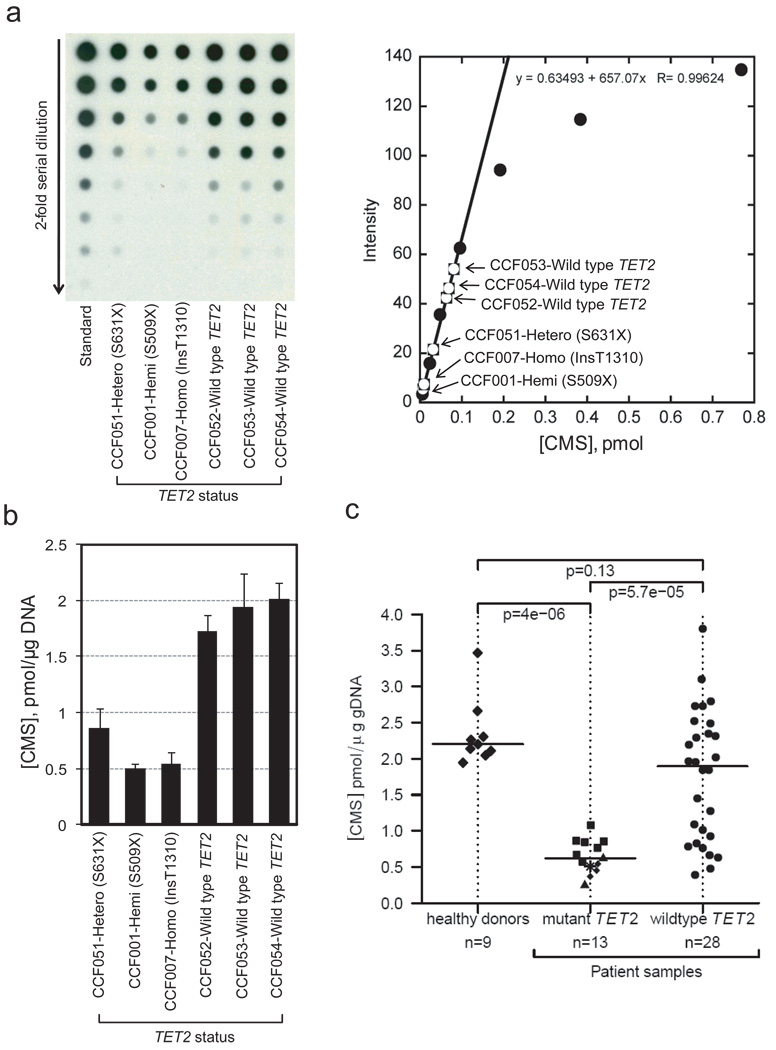

To quantify these findings, we developed dot blot assays to detect 5-hmC in genomic DNA (Suppl. Fig. 5). In the first assay format, the blot was developed with a specific antiserum to 5-hmC (Suppl. Fig. 5b, left), whose ability to recognize 5-hmC depended strongly on the density of 5-hmC in DNA (Suppl. Fig. 5c, top). We therefore developed a more sensitive and quantitative assay in which DNA was treated with bisulfite to convert 5-hmC to cytosine 5-methylenesulfonate (CMS) 14 (Suppl. Fig. 5a), after which CMS was measured with a specific anti-CMS antiserum (Suppl. Fig. 5b, right). Unlike anti-5-hmC which reacted efficiently only with DNA containing high densities of 5-hmC, the anti-CMS antiserum recognized DNA with an average of only a single 5-hmC per 201 bp (Suppl. Fig. 5c, bottom). This lack of density dependence allowed us to plot the signal obtained with 2-fold dilutions of a standard oligonucleotide containing a known amount of 5-hmC against the amount of CMS obtained after bisulfite conversion. We assumed 100% conversion efficiency15 and used the linear portion of the standard curve to compute the amount of CMS, and therefore 5-hmC, in the DNA samples (e.g. see Fig. 2a, right).

Figure 2. TET2 mutational status correlates with 5-hmC levels in patients with myeloid malignancies.

a, Quantification of 5-hmC by anti-CMS dot blot. Left, A representative dot blot of genomic DNA isolated from bone marrow aspirates of patients with MDS/MPN and TET2 mutational status as indicated. A synthetic oligonucleotide with a known amount of CMS was used as standard. Right, The linear portion of the standard curve was used to estimate the amount of 5-hmC in DNA from patient samples.

b, Bar graph of data from Fig. 2a. The three patients with TET2 mutations show lower 5-hmC levels than the three patients with wild type TET2. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n=3).

c, Correlation of 5-hmC levels with TET2 mutational status. CMS levels in bone marrow samples from healthy donors and patients with myeloid malignancies (Suppl. Table S1) are shown as the median of triplicate measurements (Suppl. Fig. 7b). In the TET2 mutant group, squares, triangles, diamonds and the star indicate homozygous, hemizygous, heterozygous and biallelic heterozygous mutations, respectively (for detail definition, see online methods). The horizontal bar indicates the median for each group. p-values for group comparisons were calculated by a two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test. Patients bearing TET2 mutations show uniformly low 5-hmC expression levels.

To assess 5-hmC levels, we obtained uniform populations of Tet2-expressing HEK293T cells by transfection with Tet2-IRES-CD25 plasmid followed by magnetic isolation of CD25-expressing cells1. Wild type and mutant Tet2 proteins were expressed at comparable levels (Fig. 1d, Suppl. Fig. 3d). Anti-5-hmC/ CMS dot blots of genomic DNA revealed, as expected, that 5-hmC was barely detectable in DNA from cells transfected with empty vector; DNA from cells expressing wild type Tet2 showed a substantial increase in 5-hmC and a corresponding decrease in 5-mC; and DNA from cells expressing the HxD mutant Tet2 protein had very low 5-hmC (Fig. 1e, Suppl. Figs. 3e, 6). DNA from cells expressing 7 of the 9 mutant Tet2 proteins tested -- H1802Q/R, R1817S/M, W1211R, P1287S and C1834D -- contained significantly less 5-hmC than DNA from cells expressing wild type Tet2 (Fig. 1e, Suppl. Figs. 3e, 6), confirming our previous conclusion that these mutations impair enzymatic activity.

We measured 5-hmC (CMS) levels in genomic DNA extracted from bone marrow or blood (with >20% immature myeloid cells) of 88 patients with myeloid malignancies and 17 healthy controls (Suppl. Table S1). In blinded experiments, DNA was treated with bisulfite and CMS levels were evaluated. TET2 mutations were strongly associated with low genomic 5-hmC (Fig. 2, Suppl. Fig. 7a). To confirm these conclusions in a statistically rigorous fashion, we tested samples for which a sufficient amount of DNA was available to make independent dilutions in triplicate, so that a median and standard deviation for 5-hmC (CMS) levels in each patient could be derived (Suppl. Fig. 7b). Analysis of DNA from 9 healthy donors and 41 patients (28 with wild type TET2 and 13 with TET2 mutations, Suppl. Table S1) revealed a strong, statistically significant correlation of TET2 mutations with low 5-hmC (Fig. 2c). In contrast, samples from patients with wild type TET2 showed a bimodal distribution, with 5-hmC levels ranging from ~0.4 to ~3.8 pmol/µg DNA (Fig. 2c; Suppl. Fig. 7; also see Fig. 4).

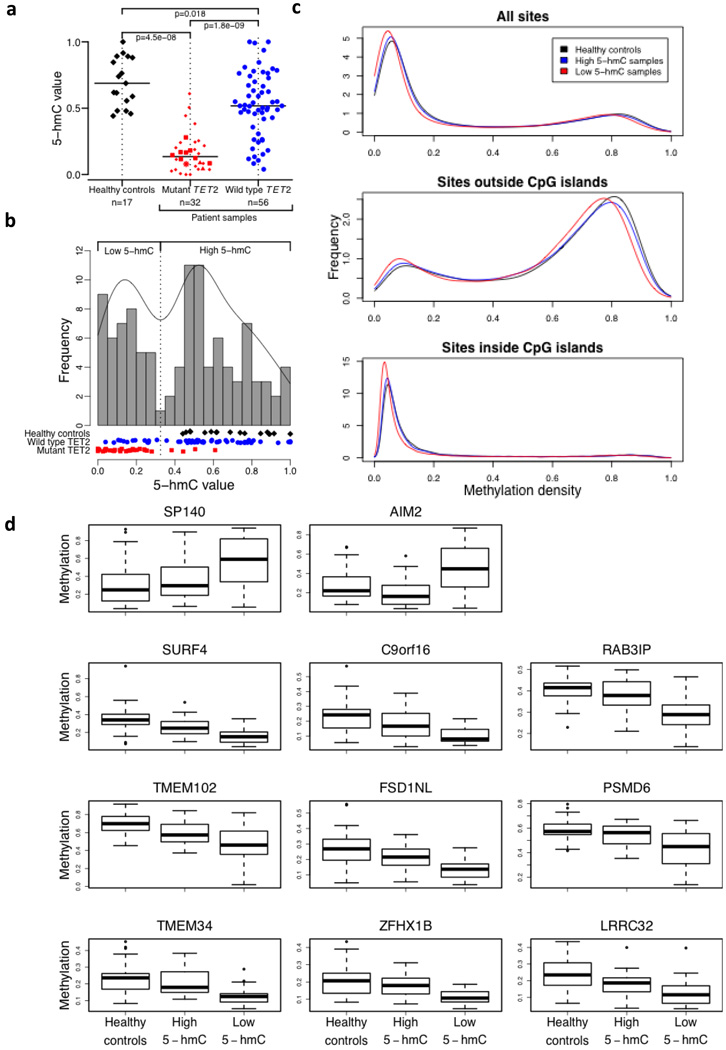

Figure 4. Relation of 5-hmC levels to DNA methylation status.

a, Normalised 5-hmC (CMS) levels in DNA from three different groups: healthy controls (black diamonds), patients with mutant TET2 (red symbols) and patients with wild type TET2 (blue circles). Among TET2 mutants, we distinguish homozygous (squares), hemizygous (triangles), heterozygous (small diamonds) and biallelic heterozygous (star) mutations (for definitions see Online Methods). The horizontal bar indicates the median for each group. The number of samples in each group is indicated.

b, Histogram of normalised 5-hmC (CMS) levels in DNA from healthy donors (black diamonds), patients with mutant TET2 (red rectangles) and patients with wild type TET2 (blue circles). The frequency was calculated based on a Gaussian kernel estimator. The local minimum between both modes was used as a threshold (vertical dotted line) between low and high 5-hmC values.

c, Density of methylation values for healthy controls (black), high 5-hmC samples (blue) and low 5-hmC samples (red) of all sites (top panel), sites outside CpG islands (middle panel) and sites inside CpG islands (lower panel).

d, Boxplot for group-specific methylation for the only two hypermethylated sites (SP140, AIM2; top panel) and the top nine hypomethylated sites (lower panels) between healthy controls and low 5-hmC samples (total number of differentially sites was 2512).

We examined Tet2 expression in haematopoietic cell subsets isolated from bone marrow and thymus of C57BL/6 mice (Suppl. Figs. 8, 9). Tet2 mRNA was highly expressed in lineage-negative (Lin−) Sca-1+c-Kithi multipotent progenitors (LSK), at levels similar to those in embryonic stem cells (ESC). Expression was maintained at high levels in myeloid progenitors (common myeloid progenitors, CMPs, and granulocyte-monocyte progenitors, GMPs), was low in mature granulocytes (Gr-1+Mac-1+) and high in monocytes (Gr-1− Mac-1+) (Suppl. Fig. 9a, middle panel).

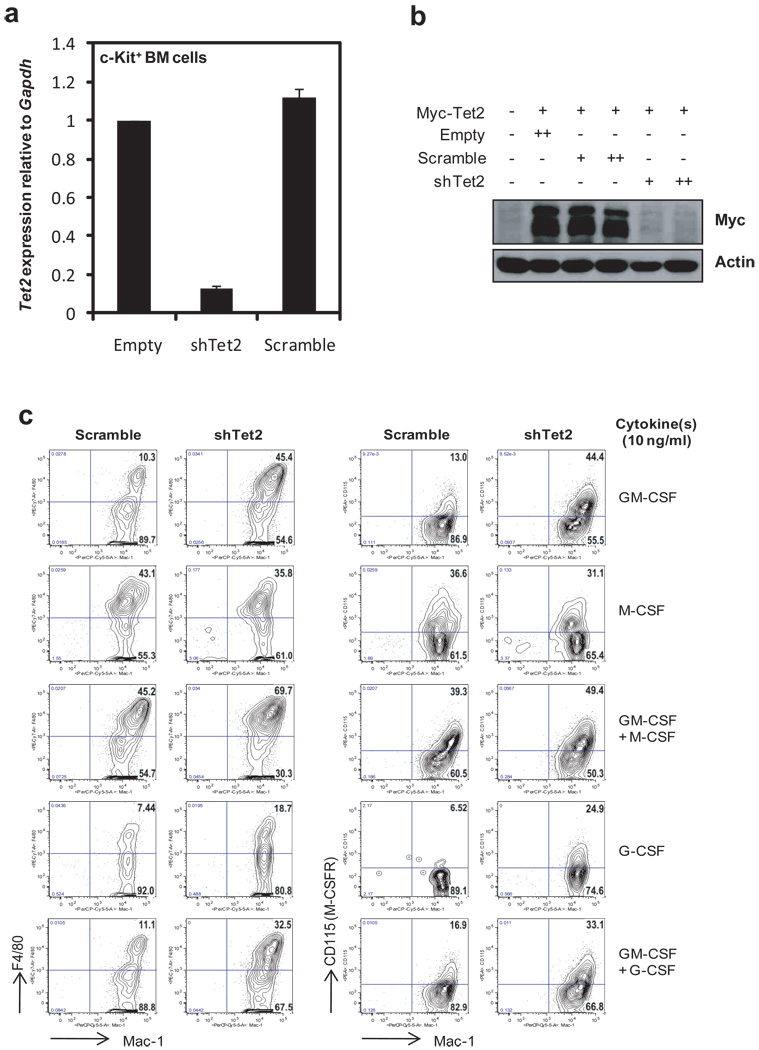

To test the role of Tet2 in myelopoiesis, we transduced bone marrow stem/progenitor cells with Tet2 shRNA (Suppl. Fig. 10a), effectively downregulating Tet2 mRNA and protein relative to control cells transduced with empty vector or scrambled shRNA (Fig. 3a, b) (refer to Suppl Fig. 10 b for choice of Tet2 shRNA). Tet2 depletion promoted expansion of Mac-1+ F4/80+ and Mac1+ CD115+ monocyte/macrophage cells in the presence of G-CSF or GM-CSF, cytokines that support granulocyte and granulocyte/ monocyte development respectively, but not in the presence of M-CSF, which promotes growth of monocytic progenitors (Fig. 3c; Suppl. Fig. 10d). Simultaneous treatment with GM-CSF and M-CSF, or GM-CSF and G-CSF, also led to increased numbers of monocyte/macrophage cells (Fig. 3c). These results indicate that Tet2 plays an important role in normal myelopoiesis. However, Tet2 does not markedly influence short-term proliferation of myeloid-lineage cells: when shRNA-transduced Lin− cells were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and pulse-labeled with BrdU, Tet2 depletion promoted monocyte/ macrophage expansion but CD115+ (M-CSFR+) cells from the two cultures showed no difference in acute BrdU incorporation (Suppl. Fig. 11).

Figure 3. Tet2 regulates myeloid differentiation.

a, b, Tet2 shRNA represses Tet2 mRNA and protein expression. a, c-Kit+ stem/progenitor cells from bone marrow of C57BL/6 mice were transduced with retroviruses (Suppl. Fig. 10). After selection with puromycin for 3 days, Tet2 mRNA expression was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. Error bars show the range of duplicates. b, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with expression plasmids encoding Myc-tagged Tet2 and retroviral shRNAs. 48 h later, Tet2 protein expression was quantified by anti-Myc immunoblotting of whole cell extracts.

c, Effect of Tet2 depletion on myeloid differentiation. Lin− cells purified from bone marrow of C57BL/6 mice were transduced with control (scramble) or shTet2 retroviruses, then cultured in the presence of 50 ng/ml stem cell factor (SCF), puromycin (2 µg/ml) and cytokines (10 ng/ml) as indicated (also see Suppl. Fig. 10). After 4 days, flow cytometric analysis of Mac-1 vs. F4/80 (left panel) or CD115 (also known as M-CSFR, right panel) was performed. All cells were GFP+ at the day of analysis.

We asked whether 5-hmC levels in tumour samples correlated with DNA methylation status. A histogram of normalised values from 88 patients and 17 healthy individuals showed the expected bimodal distribution (see Online Methods): healthy controls and most patient samples with wild type TET2 had high 5-hmC, while the majority of patient samples with mutant TET2 had low 5-hmC (Fig. 4b). The DNA methylation status of 62 samples was interrogated at 27,578 CpG sites. As expected16, the resulting histograms were strikingly bimodal, with sites within and outside CpG islands showing low and predominantly high methylation respectively (Fig. 4c). Comparison of 28 control samples with 24 high 5-hmC tumour samples (22 TET2 wild type, 2 TET2 mutant) showed no significant difference in DNA methylation; in contrast comparison of the control samples with 29 low 5-hmC tumour samples (7 TET2 wild type, 22 TET2 mutant) yielded 2512 differentially methylated sites, of which the majority (2510 sites) were hypomethylated compared to controls (Fig. 4d, Suppl. Table S2 online). Thus TET2 loss-of-function is predominantly associated with decreased methylation at CpG sites.

To summarise, our studies demonstrate a strong correlation between myeloid malignancies and loss of TET2 catalytic activity. The leukemia-associated missense mutations associated with diminished 5-hmC levels provide clues to the structure of the TET2 catalytic domain. The W1211R, P1287S and C1834D mutations affect positions that are highly conserved within the catalytic domain of the TET subfamily of dioxygenases2: W1211 is located at the beginning of the strand just N-terminal to the core of the DSBH, and is predicted to constitute part of the “mouth” of the active site pocket of the enzyme; P1287 is predicted to stabilize the conformation of the junction between the N-terminal helix and the first core strand of the DSBH; and G1913/ C1834 is predicted to be the N-terminal capping residue of a helix that lines the “mouth” of the DSBH and potentially interacts with substrate DNA2. The E1238G mutation had no detectable effect on 5-hmC production in our overexpression assays, however, the patient with this mutation also showed CN-LOH spanning 4q24, a feature that likely contributes to the significant reduction in 5-hmC levels observed in the bone marrow.

Low 5-hmC levels were observed in a subset of patients with apparently wild type TET2, whose clinical phenotypes resembled those of patients with mutant TET2. In several of these patients, TET2 mRNA expression was not significantly different from controls; mutations in other TET proteins have not been described (Suppl. Text). Some patients in the wild type TET2/ low 5-hmC category may harbour mutations in regulatory or partner proteins for TET2, or in cis-regulatory regions controlling TET2 mRNA expression. Alternatively, the primary event in some of these patients may be CpG hypomethylation, resulting in decreased 5-hmC secondary to depletion of the substrate, 5-mC.

There is little consensus on whether TET2 mutations correlate with clinical outcome. One study reported an association with decreased survival in AML4, whereas others report little prognostic value in MPN diseases7,10,12. Assays for 5-hmC may increase our options for the molecular classification of myeloid malignancies, making it possible to ask whether patients with high or low levels of genomic 5-hmC show differences in disease progression or therapeutic response. Notably, histone deacetylase and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors show clinical efficacy in patients with CMML and AML17; and genomic 5-hmC levels could potentially be a useful prognostic indicator or predictor of patient responses or refractoriness to “epigenetic” therapy with demethylating agents.

DNA methylation is highly aberrant in cancer18–20. Since TET operates on 5-mC, we were surprised to find that TET2 loss-of-function in myeloid tumours was associated with widespread hypomethylation rather than the expected hypermethylation at differentially-methylated CpG sites. Tumour samples with low 5-hmC may have expanded cells with localized hypomethylation at these sites; or TET2 may control DNA methylation indirectly, for instance by regulating the expression or recruitment of one or more DNA methyltransferases, perhaps via 5-hmC-binding proteins. Alternatively, if TET2 and 5-hmC are required for cells to exit the stem cell state, loss of TET2 function in myeloid neoplasms may reactivate a stem-like state characterized by generalized hypomethylation and consequent genomic instability21,22. Indeed, hypomorphic DNMT1 mutations associated with genome-wide DNA hypomethylation skew haematopoietic differentiation toward myelo-erythroid lineages23, and promote the development of aggressive T cell lymphomas due to activation and insertion of endogenous retroviruses24,25. Further studies of the role of TET2 in haematopoietic differentiation should uncover the relation between TET2 loss-of-function, DNA methylation changes and myeloid neoplasia.

Methods Summary

Patient samples

Genomic DNA was extracted from bone marrow/ peripheral blood samples from healthy donors and patients with MDS, MDS/MPN, primary and secondary AMLs. Clinical features and other detailed information pertaining to the patient samples are summarized in Suppl. Table 1.

Quantitative analysis of 5-hmC and CMS levels using dot-blot

For CMS detection, genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite using the EpiTect Bisulfite kit (QIAGEN). DNA samples were denatured and 2-fold serial dilutions were spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane in an assembled Bio-Dot apparatus (Bio-Rad). The blotted membrane was washed, air-dried, vacuum-baked, blocked, and incubated with anti-5-hmC or anti-CMS antibody (1:1,000) and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. To ensure equal spotting of total DNA on the membrane, the same blot was stained with 0.02% methylene blue in 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2). To compare results obtained in different experiments, we used the normalisation procedure described in Online Methods (see Figs. 4a, b, which incorporate data from Fig. 2 and Suppl. Fig. 6).

Methylation analysis

The DNA methylation status of bisulfite-treated genomic DNA was probed at 27,578 CpG dinucleotides using the Illumina® Infinium® 27k array (Illumina, San Diego, CA)26. Methylation status was calculated from the ratio of methylation-specific and demethylation-specific fluorophores (β-value) using BeadStudio® Methylation Module (Illumina, San Diego, CA). We removed sites on the Y and X chromosomes from the analysis because of inconsistent methylation status with respect to gender (a known problem based on communication with Illumina. Calculations are based on β values, which correspond to the methylation status of a site ranging from 0 to 1, returned by Illumina's BeadStudio software. We tested sites for differential methylation using an empirical Bayes approach employing a modified t-test (limma). The false discovery rate (FDR) is controlled at a level of 5% by the Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI44432 and RC1 DA028422 (to A.R.), NIH grants K24 HL077522 and R01 HL098522, an Established Investigator award from the Aplastic Anemia & MDS Foundation, and an award from the Bob Duggan Memorial Research Fund (to J.P.M), NIH grant R01 HG4069 (to X.S.L.) and a pilot grant from Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH Grant #1 UL1 RR 025758-02, to S.A.). Y.H. was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the GlaxoSmithKline-Immune Disease Institute (GSK-IDI) Alliance and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of America. H.S.B. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the GSK-IDI Alliance.

Footnotes

Author contributions

M.K. analysed the biochemical effects of patient-associated TET2 mutations and performed the in vitro differentiation studies; Y.H. generated and characterized the anti-CMS antiserum, developed the quantitative dot-blot assay and quantified 5-hmC in DNA samples from patients and healthy controls. A.M.J., R.G. and J.P.M. provided patient and control DNA for 5hmC quantification, performed DNA methylation arrays and analysed TET2 mutational status in patients. U.J.P. and X.S.L. carried out the statistical analysis of 5-hmC levels and methylation data; M.T., H.S.B. and K.P.K. provided critical reagents; J.A. and E.D.L. contributed to molecular cloning and mouse maintenance respectively; and L.A. and S.A. provided essential intellectual input. A.R. set overall goals and coordinated the collaborations.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Tahiliani M, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324(5929):930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iyer LM, Tahiliani M, Rao A, Aravind L. Prediction of novel families of enzymes involved in oxidative and other complex modifications of bases in nucleic acids. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(11):1698–1710. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viguie F, et al. Common 4q24 deletion in four cases of hematopoietic malignancy: early stem cell involvement? Leukemia. 2005;19(8):1411–1415. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Wahab O, et al. Genetic characterization of TET1, TET2, and TET3 alterations in myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2009;114(1):144–147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delhommeau F, et al. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(22):2289–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jankowska AM, et al. Loss of heterozygosity 4q24 and TET2 mutations associated with myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 2009;113(25):6403–6410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langemeijer SM, et al. Acquired mutations in TET2 are common in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):838–842. doi: 10.1038/ng.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine RL, Carroll M. A common genetic mechanism in malignant bone marrow diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(22):2355–2357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0902257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullighan CG. TET2 mutations in myelodysplasia and myeloid malignancies. Nat Genet. 2009;41(7):766–767. doi: 10.1038/ng0709-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tefferi A, et al. Frequent TET2 mutations in systemic mastocytosis: clinical, KITD816V and FIP1L1-PDGFRA correlates. Leukemia. 2009;23(5):900–904. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tefferi A, et al. Detection of mutant TET2 in myeloid malignancies other than myeloproliferative neoplasms: CMML, MDS, MDS/MPN and AML. Leukemia. 2009;23(7):1343–1345. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tefferi A, et al. TET2 mutations and their clinical correlates in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia and myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2009;23(5):905–911. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito S, et al. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010;466(7310):1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature09303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayatsu H, Shiragami M. Reaction of bisulfite with the 5-hydroxymethyl group in pyrimidines and in phage DNAs. Biochemistry. 1979;18(4):632–637. doi: 10.1021/bi00571a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Y, et al. The behaviour of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in bisulfite sequencing. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lister R, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462(7271):315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tefferi A. Epigenetic alterations and anti-epigenetic therapy in myelofibrosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(12):2231–2232. doi: 10.1080/10428190802578866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith LT, Otterson GA, Plass C. Unraveling the epigenetic code of cancer for therapy. Trends Genet. 2007;23(9):449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1148–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gal-Yam EN, Saito Y, Egger G, Jones PA. Cancer epigenetics: modifications, screening, and therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:267–280. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061606.095816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehrlich M. DNA hypomethylation in cancer cells. Epigenomics. 2009;1(2):239–259. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lengauer C. Cancer. An unstable liaison. Science. 2003;300(5618):442–443. doi: 10.1126/science.1084468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broske AM, et al. DNA methylation protects hematopoietic stem cell multipotency from myeloerythroid restriction. Nat Genet. 2009;41(11):1207–1215. doi: 10.1038/ng.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaudet F, et al. Induction of tumors in mice by genomic hypomethylation. Science. 2003;300(5618):489–492. doi: 10.1126/science.1083558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh CP, Chaillet JR, Bestor TH. Transcription of IAP endogenous retroviruses is constrained by cytosine methylation. Nat Genet. 1998;20(2):116–117. doi: 10.1038/2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang Y, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation is a dominant mechanism in MDS progression to AML. Blood. 2009;113(6):1315–1325. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-163246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.