Abstract

Ethylene-responsive element-binding factor (ERF) genes constitute one of the largest transcription factor gene families in plants. In Arabidopsis and rice, only a few ERF genes have been characterized so far. Flower senescence is associated with increased ethylene production in many flowers. However, the characterization of ERF genes in flower senescence has not been reported. In this study, 13 ERF cDNAs were cloned from petunia. Based on the sequence characterization, these PhERFs could be classified into four of the 12 known ERF families. Their predicted amino acid sequences exhibited similarities to ERFs from other plant species. Expression analyses of PhERF mRNAs were performed in corollas and gynoecia of petunia flower. The 13 PhERF genes displayed differential expression patterns and levels during natural flower senescence. Exogenous ethylene accelerates the transcription of the various PhERF genes, and silver thiosulphate (STS) decreased the transcription of several PhERF genes in corollas and gynoecia. PhERF genes of group VII showed a strong association with the rise in ethylene production in both petals and gynoecia, and might be associated particularly with flower senescence in petunia. The effect of sugar, methyl jasmonate, and the plant hormones abscisic acid, salicylic acid, and 6-benzyladenine in regulating the different PhERF transcripts was investigated. Functional nuclear localization signal analyses of two PhERF proteins (PhERF2 and PhERF3) were carried out using fluorescence microscopy. These results supported a role for petunia PhERF genes in transcriptional regulation of petunia flower senescence processes.

Keywords: ERF, ethylene, flower senescence, gene expression, petunia

Introduction

The gaseous phytohormone ethylene is involved in many aspects of plant growth and development (Abeles et al., 1992). Flower senescence is associated with increased ethylene production in many flowers. The climacteric rise of endogenous ethylene in these flowers has been shown to play a regulatory role in the events leading to the death of some of the flower organs (Iordachescu and Verlinden, 2005).

The expression of ethylene-related genes is induced through transduction of the ethylene signal from receptors to dedicated transcription factors (Giovannoni, 2004). Ethylene-responsive factors (ERFs) are uniquely present in the plant kingdom and belong to the AP2/EREBP-type transcription factors, which function as trans-acting factors at the last step of transduction (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1995). ERF proteins can specifically bind the GCC box cis-acting element (core sequence AGCCGCC) that is present in promoters of pathogenesis-related (PR) genes (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1995; Park et al., 2001). Although Arabidopsis has 122 predicted ERF genes (Nakano et al., 2006) and Oryza sativa (rice) has 139 predicted ERF genes, only a few have been characterized so far (Sakuma et al., 2002). In tomato, plum, kiwifruit, and apple, the role of ERF genes in fruit ripening has been reported. However, the characterization of ERF genes in flower senescence has not been reported.

Petunia, an important ornamental plant, often serves as a model for ethylene-sensitive flower senescence. Transgenic petunias constitutively expressing the mutant Arabidopsis ethylene receptor gene etr1-1 exhibit decreased ethylene sensitivity and delayed flower senescence (Wilkinson et al., 1997). The role of petunia EIN2 was reported by Shibuya et al. (2004). In the present work, 13 full-length ERF genes of petunia were identified and transcriptional regulation of the 13 ERF genes was investigated during natural flower senescence in petunia and in response to different plant hormones, in order to gain further insights into their roles in petunia flower senescence. Finally, the subcellular localization of two of the PhERF proteins was examined using green fluorescent protein (GFP).

Materials and methods

Plant material

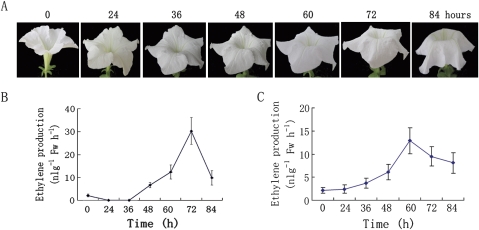

Petunia (Petunia hybrida ‘Carpet White’) plants were grown under normal greenhouse conditions (22 °C, 14 h light/10 h dark). Flowers were emasculated 1 d before flowers were fully open to prevent self-pollination. Eight to 10 petunia flowers were harvested at anthesis (corollas 90 ° reflexed) stages and then placed immediately in tap water. Within 1 h of harvest, the flowers were delivered to the laboratory; after the stems were cut to a length of 5 cm under water, the flowers were placed in distilled water for further processing. Corollas and gynoecia were collected from petunias at 0 (corollas 90 ° reflexed), 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, and 84 h after flower full opening (Fig. 3A). Stem, leaves, and roots were collected from plants at the vegetative stage when the plants were ∼10 cm in height. All tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C until used for RNA extraction. Fresh weights were measured immediately before freezing. At least six corollas or gynoecia were pooled for each time point. All experiments were conducted at least three times with independently collected and extracted tissues, unless otherwise noted.

Fig. 3.

Natural senescence of unpollinated wild-type (WT) Petunia hybrida ‘Carpet White’ flowers and changes in ethylene production of corollas and gynoecia. (A) Natural senescence of unpollinated WT P. hybrida ‘Carpet White’ flowers. (B) Changes in ethylene production of corollas. (C) Changes in ethylene production of gynoecia. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted according to previously described protocols (Woodson and Lawton, 1988; Iordachescu and Verlinden, 2005). Briefly, 2 g of frozen tissue was powdered under liquid nitrogen and homogenized in equal volumes (10 ml) of phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol (25:24:1, v/v/v) and an extraction buffer containing 50 mM TRIS-HCl (pH 8.0), 5% phenol (pH 8.0), 6% sodium p-aminosalicylate, and 1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol. Following phase separation, nucleic acids were precipitated by the addition of 1/20 vol. of 4 M sodium acetate (pH 6.0) and 2 vols of ethanol overnight at –20 °C. The precipitate was resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water, reprecipitated by the addition of 3 vols of 4 M sodium acetate (pH 6.0), and incubated on ice for 1.5 h. The precipitated RNA was dissolved in DEPC-treated water. RNA content was determined spectrophotometrically.

A 1 μg aliquot of total RNA was reverse transcribed at 42 °C for 1 h in 20 μl final volume reaction mixture containing reaction buffer, 20 mmol l−1 dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 mmol l−1 dNTP, 1 μg oligo(dT)15, and reverse transcriptase (AMV; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cloning of the petunia PhERF1–PhERF13 genes

The partial sequences of PhERF1–PhERF13 were obtained by a computational identification approach (Yang et al., 2010). Briefly, TBLASTN analysis against the GenBank EST database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) with AtERF2 identified 13 petunia clones, FN015325, FN032926, CV301184, FN004404, FN001585, FN006171, FN014682, CV297340, FN033374, FN000871, FN005346, FN040788, and CV300585, encoding putative proteins that displayed conservation with Arabidopsis ERFs. The remaining 5′ and 3′ cDNA sequences of PhERF1–PhERF13 were isolated by rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE). The Gene Race amplification system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and EXPAND Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA) were used for all RACE experiments. Once the sequence of the 5′ and 3′ ends of each cDNA had been determined, full-length cDNAs for PhERF1–PhERF13 were isolated by RT-PCR.

Sequence analysis

Alignments were carried out on DNAMAN software, and a phylogenetic tree was generated with MEGA version 3.1 (Kumar et al., 2004). An identity search for nucleotides and translated amino acids was carried out using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BLAST network server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/BLAST).

Ethylene measurements

To measure the ethylene production, corollas and gynoecia of each individual flower were collected and placed in a 200 ml airtight container according to the method of Ma et al. (2006). Thus, to avoid the contamination with wound-induced ethylene, the containers were capped and incubated at 25 °C for 1 h for corollas and gynoecia. Then a 2 ml sample of head-space gas was withdrawn using a gas-tight hypodermic syringe, and injected into a gas chromatograph (GC 17A, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) for ethylene concentration measurement. The gas chromatograph was equipped with a flame ionization detector and an activated alumina column. All measurements were performed with eight replicates.

Quantitative real-time PCR assays

Total RNA was extracted from the samples of corollas and gynoecia and digested with RNase-free DNase I followed by reverse transcription according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR analysis was performed with the cDNA extracted from different samples as a template. For real-time PCR, oligonucleotide primers were designed according to each gene's untranslated region with Primer3 (version 0.4.0; http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi). All primers were tested with melting peaks and dissociation curves to confirm that there was only one product for each pair of primers. In order to verify that primers were specific for amplifications of the target genes, all PCR products were purified and resequenced. The sequences of all primers used for real-time PCR analysis are described in Table 1. Petunia actin was used as the housekeeping gene to quantify cDNA abundance.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of PhERF1–PhERF13 used in quantitative real-time PCR

| Gene | Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) | PCR product size (bp) |

| PhERF1 | ATCAAGGTGGCATACAAGAAG | ACCTTCGTGAAATTATAGAGC | 145 |

| PhERF2 | GCATTTGAATCTGAGATGAAGT | ACTTAGTAGACACCTCCCATCA | 167 |

| PhERF3 | TGACTGCTCTGATTTTGGTTGG | CTTTGCACTGAATTGTTCGTAC | 156 |

| PhERF4 | GTATGTTGATGGCCAATCAGTG | ATAAATGAGCTGGGGACACTGG | 122 |

| PhERF5 | GATTCGGTGATTCTGACCCTCT | ATGCTACTACCCAAGGGCTAAC | 170 |

| PhERF6 | AGCCAAAGAAGACGGTGGATT | TCCGTCTTCGTCAGCTCTTTC | 165 |

| PhERF7 | GTGGATGATCGTTGCGATGTTG | GAGACATAACGCAGTAACATGTA | 135 |

| PhERF8 | GATTGCCGTAGCGACTGTGATT | AGCTCATCGGAGTCCACGTCAT | 161 |

| PhERF9 | TGACTCTGCAGCTTTCAAGATG | CTCGAAATCCCAACTACGTGGAG | 155 |

| PhERF10 | CTAGAGCTTATGATTGTGCTGC | TCACCATATCAATTCTCATGATCTC | 139 |

| PhERF11 | CGGGACGTATGAGACATCAGAG | ATGATTTTCAAACGCCTCTTCGG | 156 |

| PhERF12 | TAGATACTCCATTGACACCTTC | ATTATGAAACCAAAAGCTGAGAG | 138 |

| PhERF13 | AATTCTTGGGATGGGGTTGTGA | CCTTCAGCATGTTCATCACCAA | 158 |

The PCR was performed in an iCycler iQ™ Real-time Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). For each 25 μl reaction, 1 μl of sample cDNA was mixed with 12.5 μl of IQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), 0.5 μl of forward primer (12 μM, final concentration 240 nM), 0.5 μl of reverse primer (12 μM, final concentration 240 nM), and 10.5 μl of sterile water. Samples were subjected to thermal cycling conditions of DNA polymerase activation at 95 °C for 4 min, 40 cycles of 45 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 52 °C or 55 °C, 45 s at 72 °C, and 45 s at 80 °C; a final elongation step of 7 min at 72 °C was performed. The melting curve was designed to increase 0.5 °C every 10 s from 62 °C. Real-time PCR analysis was performed with two different cDNAs from the same time point (from two different RNAs), and each was carried out in triplicate. The amplicon was analysed by electrophoresis and sequenced once for identity confirmation. Quantification was based on analysis of the threshold cycle (Ct) value as described by Pfaffl (2001).

Ethylene treatment

Petunia flowers were treated with ethylene according to the previously described protocols (Iordachescu and Verlinden, 2005). Petunia flowers were harvested at anthesis and their stems re-cut to 5 cm, placed in flasks with distilled water, and subsequently treated with 2 μl l−1 ethylene for 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. Corollas and gynoecia from 8–10 flowers were collected at each time point, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C for later RNA extraction.

Silver thiosulphate (STS), abscisic acid (ABA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), salicylic acid (SA), methyl jasmonate (MeJA), 6-benzyladenine (BA), and sucrose treatment

Petunia flowers harvested at anthesis (corollas 90 ° reflexed), re-cut to 5 cm in length, were placed in 1.0 l flasks containing either distilled water or STS (1.6 mM Na2S2O3·5H2O, 0.2 mM AgNO3), an inhibitor of ethylene action, and held in controlled environmental conditions (12/12 h, 24 °C day/night temperature, 50 μmol m−2 s−1), or 50 μM ABA, 50 μM IAA, 0.6 mM SA, 50 μM MeJA, 50 μM BA, or 5% sucrose solution for 12 h. Then the flowers were transferred to distilled water and incubated at room temperature for 20 d. The distilled water was changed every day. After STS treatment at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h, the corollas and gynoecia were collected and frozen for later RNA extraction. After ABA, IAA, SA, MeJA, BA, or sucrose at 0, 6, and 24 h, the corollas were collected and frozen for later RNA extraction.

Subcellular localization and fluorescence microscopy

The coding sequences of PhERF2 and PhERF3 were cloned as a C-terminal fusion in-frame with GFP into the pGreen vector (Hellens et al., 2000) and expressed under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter. A high fidelity PCR system was used to amplify the full-length PhERF2 and PhERF3 clones. The corresponding open reading frames (ORFs) were cloned using the BamHI restriction site of the pGreen vector.

Particle bombardment with a Biolistic PDS-1000/He system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to introduce GFP fusion plasmids into onion epidermal cells. Tungsten particles were coated with the plasmids 35S:GFP:PhERF2, 35S:GFP:PhERF3, and 35S:GFP, and a helium pressure of 1100 psi was employed. Tungsten particles, 500 μg, coated with 0.8 μg of DNA were used in each shot. The target distance between the stop screen and piece of onion was set at 9 cm. Onions (Allium cepa L.) used for particle bombardment were obtained from a local supermarket. After bombardment, onion pieces were placed on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium and kept in darkness at 22 °C for 15 h. The onion epidermal cells were then examined under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and single optical sections were taken to visualize the resulting images for each transient expression.

Results

Identification of 13 ERF transcription factor genes in petunia

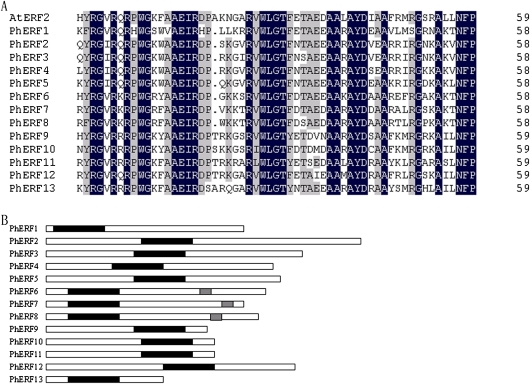

Thirteen ERF full-length cDNAs were isolated and designated as PhERF1–PhERF13. PhERF1–PhERF13 (GenBank accession nos HQ259595–HQ259607) were predicted to encode proteins of 231, 378, 363, 252, 266, 220, 207, 217, 185, 190, 207, 289, and 129 amino acids, with calculated mol. wts of 25.7, 41.9, 40.1, 28.6, 29.9, 24, 22.6, 24.0, 20.9, 21.3, 23.8, 32.9, and 14.7 kDa, respectively. The relationships between the predicted amino acid sequences, as indicated by percentage similarity over the whole sequence, are presented in Table 2. The similarities of the PhERFs varied from 21.6% (PhERF1 and PhERF2) to 76.7% (PhERF2 and PhERF3). The deduced amino acid sequences of PhERFs comprise a conserved DNA-binding ERF/AP2 domain (ranging from 58 to 59 amino acids), which is characteristic of the plant ERF gene family (Fig. 1A).

Table 2.

Amino acid sequence comparison between the predicted full-length ethylene response factor (PhERF) cDNAs

| Amino acid similarity (%) |

||||||||||||

| PhERF1 | PhERF2 | PhERF3 | PhERF4 | PhERF5 | PhERF6 | PhERF7 | PhERF8 | PhERF9 | PhERF10 | PhERF11 | PhERF12 | |

| PhERF2 | 21.6 | 100 | ||||||||||

| PhERF3 | 21.9 | 76.7 | 100 | |||||||||

| PhERF4 | 24.5 | 36.7 | 49.0 | 100 | ||||||||

| PhERF5 | 25.4 | 36.5 | 34.2 | 35.5 | 100 | |||||||

| PhERF6 | 28.2 | 23.2 | 23.7 | 25.7 | 30.4 | 100 | ||||||

| PhERF7 | 27.3 | 27.9 | 24.6 | 27.1 | 29.7 | 32.0 | 100 | |||||

| PhERF8 | 25.3 | 22.9 | 24.9 | 25.4 | 25.8 | 33.3 | 54.7 | 100 | ||||

| PhERF9 | 40.2 | 29.3 | 29.5 | 33.6 | 29.2 | 43.0 | 37.6 | 38.5 | 100 | |||

| PhERF10 | 41.2 | 33.1 | 31.7 | 32.9 | 32.7 | 40.6 | 40.8 | 39.8 | 59.2 | 100 | ||

| PhERF11 | 35.0 | 26.9 | 27.2 | 29.7 | 30.5 | 37.4 | 41.0 | 34.2 | 35.3 | 36.6 | 100 | |

| PhERF12 | 26.7 | 25.5 | 23.1 | 25.2 | 24.1 | 27.1 | 32.8 | 26.7 | 39.7 | 37.0 | 32.5 | 100 |

| PhERF13 | 36.1 | 37.0 | 33.8 | 35.4 | 45.5 | 36.5 | 33.1 | 35.2 | 41.8 | 41.7 | 42.7 | 36.4 |

Fig. 1.

Schematic analysis of PhERFs with ERF domains and EAR repressor domains. (A) Comparison of ERF domains by deduced amino acids sequences. Conserved residues are shaded in black. Grey shading indicates similar residues in 10 out of 14 of the sequences. (B) Location of ERF domains (black bars) and EAR repressor domains (grey bars).

The ERF domain of most PhERFs includes two key amino acid residues, the 14th alanine A (A) and the 19th aspartate (D), believed to contribute a functional GCC box-binding activity in many ERFs (Sakuma et al., 2002), with the exception of PhERF1, in which the two amino acid residues are instead the 14th valine (V) and the 19th histidine (H) (Fig. 1A).

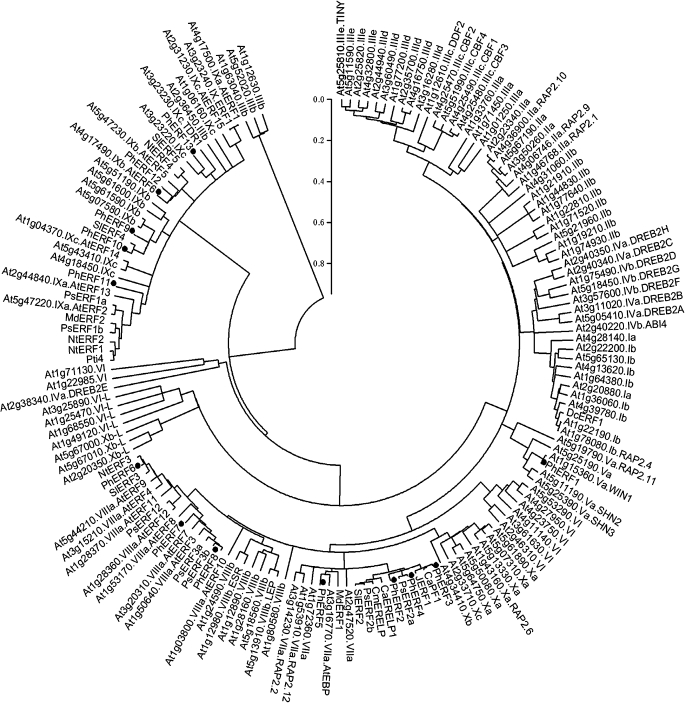

Phylogenetic analysis of PhERF proteins

Comparison of the amino acid sequence and phylogenetic analysis of PhERFs and 122 AtERFs revealed that PhERF sequences belong to four out of 12 groups of ERF proteins (Nakano et al., 2006) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of ERFs. Thirteen petunia PhERFs (black circles) were aligned with the Arabidopsis ERF family, Solanum lycopersicum [SlERF2 (GenBank accession number AAO34704), SlERF3 (AAO34705), SlERF4 (AAO34706), SlERF5 (AY559315.1), Pti4 (AAC50047), JERF1 (AAK95687)]; Nicotiana tabacum [NtERF1 (UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot accession no. Q40476), NtERF2 (Q40479), NtERF3 (Q40477), NtERF4 (Q40478)]; Capsicum annuum [CaPF1 (GenBank accession no. AAP72289), CaERELP1 (AAS20427)], Malusx domestica [MdERF1 (GenBank accession no. BAF43419), MdERF2 (BAF43420)]; Prunus salicina [PsERF1a (GenBank accession no. FJ026009), PsERF1b (FJ026008), PsERF2a (FJ026007]), PsERF2b (FJ026006), PsERF3a (FJ026005), PsERF3b (FJ026004), PsERF12 (FJ026003)]; Cucumis melo [CmERELP (GenBank accession no. BAD01556)]; and Dianthus caryophyllus [DcERF1 (GenBank accession no. AB517647)]. The amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis ERFs were obtained from the Arabidopsis Information Resource or the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. The amino acid sequences were analysed with Vector NTI (version 9.0.0; Invitrogen), and the phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA (version 3.1) using a bootstrap test of phylogeny with minimum evolution test and default parameters.

The predicted PhERF1 protein is classified as a members of group V ERFs (Nakano et al., 2006) (Fig. 2). The PhERF1 predicted protein contains an ERF domain consisting of 58 amino acids located near the middle of the sequences (Fig. 1B). The deduced amino acid sequence of PhERF1 shares 68.1, 57.1, and 56.2% identity with Arabidopsis At1g15360/SHN1, At5g11190/SHN2, and At5g25390/SHN3. The four genes, belonging to subgroup Va, share two motifs, CMV-1 and CMV-2, in the C-terminal regions (see Supplementary Fig. S1a available at JXB online).

PhERF2–PhERF5 encode proteins that belong to group VII ERFs (Nakano et al., 2006) (Fig. 2). These sequences share 33.7–50.0% similarity with their homologues in Arabidopsis, At1g53910/RAP2.12 and At3g14230/RAP2.2. The predicted PhERF2, PhERF3, and PhERF4 proteins share the CMVII-1 motif in the N-terminal regions with At1g53910/RAP2.12 and At3g14230/RAP2.2 (see Supplementary Fig. S1b at JXB online), but PhERF5 did not include this motif.

The predicted PhERF6–PhERF8 proteins are assigned to group VIII ERFs (Nakano et al., 2006) (Fig. 2). The three sequences share 36.0–63.1% similarity with their Arabidopsis homologues, At1g28370/AtERF11, At1g50640 /AtERF3, and At1g53170/AtERF8. The predicted PhERF6–PhERF8 proteins possess an ERF domain consisting of 57 amino acids located near the N-terminal regions (Fig. 1B) and comprise two motifs, the ERF-associated amphiphilic repression domain (EAR/CMVIII-1; Fig. 1B) and CMVIII-2, in the C-terminal region (Zhou et al., 1997; Fujimoto et al., 2000; Tournier et al., 2003; Nakano et al., 2006) (see Supplementary Fig. S1c at JXB online).

The predicted PhERF9–PhERF13 proteins are classified as members of group IX ERFs (Nakano et al., 2006) (Fig. 2). These sequences shared 27.3–46.0% similarity with their homologues in Arabidopsis, At3g23240/AtERF1 and At2g31230/AtERF15.

Ethylene production and PhERF gene expression in corollas and gynoecia of petunia during natural flower senescence

Ethylene measurement of corollas and gynoecia of the senescence stage of petunia flower used in this study showed a typical ethylene climacteric, and ethylene production was detected after full opening (0 h) of the flowers, attaining the maximum rate in corollas and gynoecia at 72 h and 60 h, respectively (Fig. 3B, C).

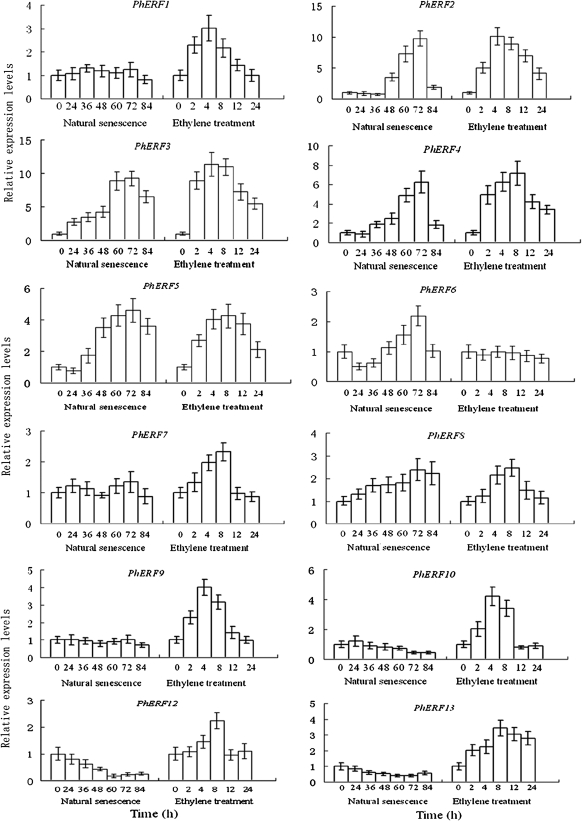

Changes in the PhERF gene mRNA levels were monitored by using quantitative real-time PCR analysis and mRNAs isolated from corollas and gynoecia.

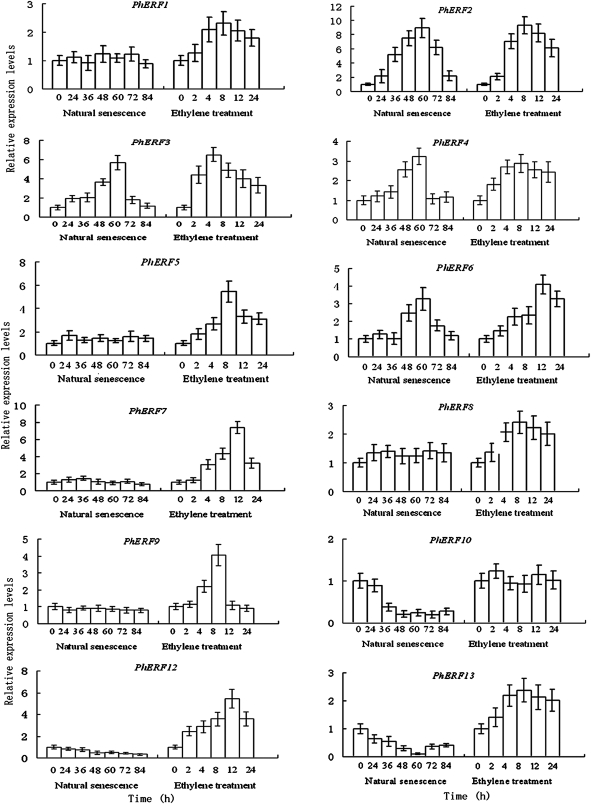

Figure 4 shows the expression profile of the different PhERF genes in corollas during natural flower senescence (0–84 h after harvest). The isolated sequences were differentially expressed throughout development and flower senescence. The levels of PhERF2, PhERF3, PhERF4, and PhERF5 mRNA were low before 36 h, increased significantly at 48 h, peaked at 72 h when ethylene production reached the maximum, and then decreased. A slight increase was found in the amount of mRNAs for PhERF8 in corollas during natural flower senescence in petunia (Fig. 4). PhERF1, PhERF6, PhERF7, and PhERF9 showed a constitutive expression pattern, and PhERF10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 expression showed a decreasing trend toward the late stage of senescence.

Fig. 4.

Expression profile of PhERF1-10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 during natural flower senescence, and effects of exogenous ethylene on the expression of these genes by quantitative PCR in petunia corollas. The mRNA level in corollas was measured by quantitative PCR. Relative expression levels are shown as fold change values (1=time 0). Data are means ±SD (n–3).

In gynoecia, the amount of PhERF2, PhERF3, and PhERF4 transcripts increased significantly at 48 h and peaked at 72 h, the change being consistent with ethylene production in gynoecia during natural flower senescence in petunia (Fig. 5). As in corollas, decreasing levels of PhERF10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 transcripts were found in gynoecia. The levels of PhERF1, PhERF5, PhERF7, PhERF8, and PhERF9 mRNAs were almost unchanged during natural flower senescence. However, the transcripts of PhERF11 were barely detected during natural flower senescence in both corollas and gynoecia and were not affected by exogenous ethylene (data not shown); therefore PhERF11 was not studied further.

Fig. 5.

Expression profile of PhERF1-10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 during natural flower senescence and effects of exogenous ethylene on the expression of these genes by quantitative PCR in petunia gynoecia. The mRNA level in gynoecia was measured by quantitative PCR. Relative expression levels are shown as fold change values (1=time 0). Data are means ±SD (n=3).

Expression of PhERF in corollas and gynoecia treated by exogenous ethylene

To determine whether PhERF genes are under ethylene regulation in petunia flowers, quantitative PCR was used to test their relative mRNA accumulation upon short-term exogenous ethylene treatment.

As shown in Fig. 4, ethylene treatment increased the abundance of transcripts of the various PhERF genes in corollas, excluding PhERF6 that was not significantly altered by the treatment. PhERF7, PhERF8, and PhERF12 expression was slightly induced by ethylene, and peaked at 8 h after ethylene treatment. The expression profiles of the other eight genes reached a high level at 4 h or 8 h after treatment.

Similarly, in gynoecia, the transcription of most PhERF genes was accelerated by ethylene treatment, excluding PhERF10 that remained almost unchanged by the treatment (Fig. 5). PhERF1, PhERF 4, and PhERF8 expression was slightly increased by ethylene, and peaked at 8 h after ethylene treatment. The expression profiles of the other eight genes reached a high level at 4 h or 8 h after treatment (Fig. 5).

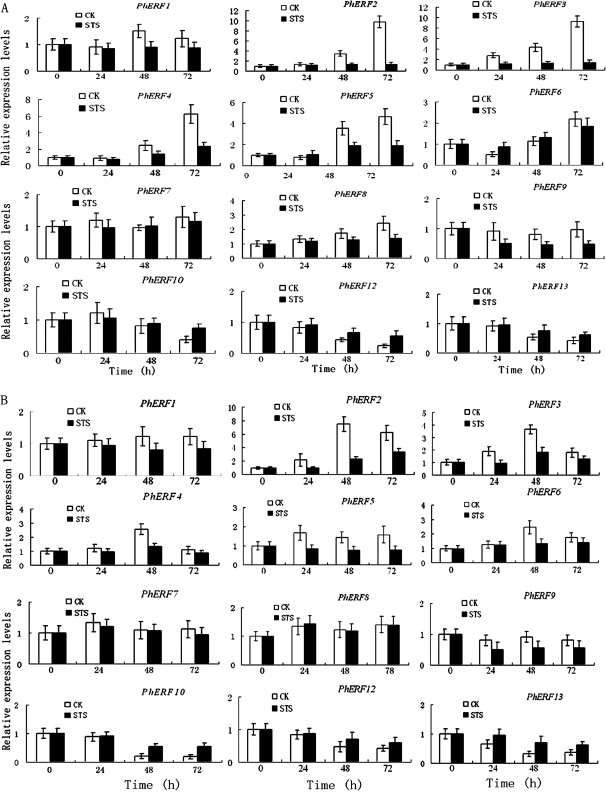

Expression of PhERF in corollas and gynoecia treated by STS

STS inhibits the climacteric increase of ethylene by blocking the ethylene-binding site of the ethylene receptor and activating the ethylene receptor (Veen, 1983; Woltering and Van Doorn, 1988). Petunia flowers treated with 0.2 mM STS delayed corolla senescence by 5 d, and no ethylene production was detected during the incubation period (data not shown). The effect of STS on the levels of mRNA for PhERF genes was investigated in corollas and gynoecia (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effects of STS on the expression of PhERF1-10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 by quantitative PCR in corollas and gynoecia. (A) Effects of STS on the expression of PhERF1-10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 in corollas. (B) Effects of STS on the expression of PhERF1-10, PhERF 12, and PhERF 13 in gynoecia. The mRNA level was measured by quantitative PCR. Relative expression levels are shown as fold change values (1=time 0). Data are means ±SD (n=3).

After STS treatment, the levels of PhERF1, PhERF2, PhERF3, PhERF4, PhERF5, PhERF8, and PhERF9 mRNA remained low and did not increase compared with the control; STS did not affect the levels of PhERF6 and PhERF7 mRNA. PhERF10, PhERF 12, and PhERF13 transcripts decreased slightly from 24 h to 72 h after STS treatment. It should be noted that in the non-treated flowers, PhERF10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 transcripts decreased significantly from 24 h to 72 h; therefore, after STS treatment, the decrease in their transcripts was delayed in corollas compared with the control (Fig. 6A).

Similar results were observed in gynoecia, with the exception of PhERF8, which did not change significantly compared with the control, and PhERF6, whose transcripts were decreased when compared with the control (Fig. 6B).

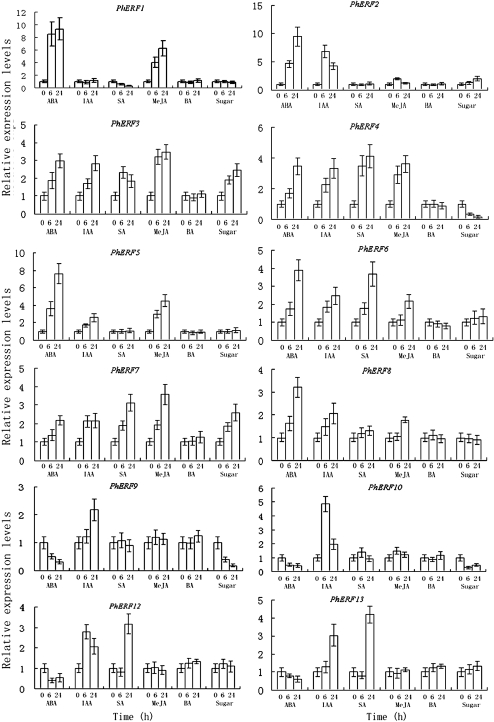

Effect of other hormones and sugar treatments on the expression of the PhERF genes in corollas

To investigate the control mechanisms of other hormones underlying PhERF gene expression, petunia flowers were treated with ABA, IAA, SA, and MeJA, and the changes in transcript abundance of these genes were analysed using quantitative PCR.

At 6 h after ABA treatment, PhERF1–PhERF6 and PhERF8 expression increased significantly, and PhERF7 expression did not increase significantly, while PhERF9, PhERF10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 expression decreased significantly (Fig. 7). The expression of PhERF1–PhERF8 kept increasing significantly, that of PhERF10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 did not change significantly, and that of PhERF9 kept decreasing from 6 h to 24 h after ABA treatment (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effects of ABA, IAA, SA, MeJA, BA, and sugar on the expression of PhERF1-10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 by quantitative PCR in corollas of petunia. The mRNA level in corollas was measured by quantitative PCR. Relative expression levels are shown as fold change values (1=time 0). Data are means ±SD (n=3).

After IAA treatment, most PhERF mRNAs showed accumulation at 6 h and 24 h, with the exception of PhERF1, which showed a constitutive expression pattern (Fig. 7).

As shown in Fig. 7, SA treatment did not affect the levels of PhERF3, PhERF4, PhERF6, PhERF7, PhERF12, and PhERF13, it up-regulated the expression of PhERF2, PhERF5, PhERF6, PhERF8, PhERF9, and PhERF10, and it down-regulated that of PhERF1 in corollas.

JA treatment increased the levels of PhERF1–PhERF8 mRNA in corollas and did not affect that of PhERF9, PhERF10, PhERF12, and PhERF13 mRNAs (Fig. 7).

None of the PhERF genes responded significantly to BA treatment at least under the conditions used in this study (Fig. 7).

Following treatment of flowers with 5% sucrose, the amount of PhERF1, PhERF5, PhERF6, PhERF8, PhERF12, and PhERF13 transcripts in corollas was not changed, and that of PhERF2, PhERF3, and PhERF7 increased, while that of PhERF4, PhERF9, and PhERF10 decreased at 6 and 24 h (Fig. 7).

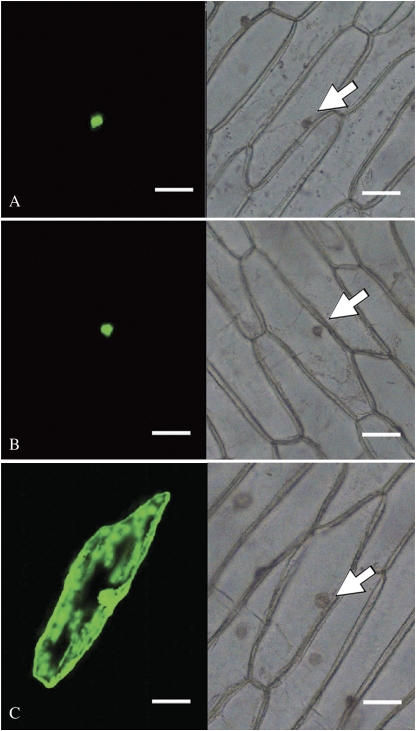

Nuclear localization of two PhERF proteins

To confirm that the PhERFs identified are indeed targeted to the nucleus, two PhERF genes of group VII were selected for analysis in vivo, based on their potential functions associated with senescence (Tournier et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2007; Yin et al., 2010). The coding regions of PhERF2 and PhERF3 were fused to the N-terminus of GFP and expressed in onion epidermal cells under the control of the constitutive CaMV 35S promoter. In two cases, green fluorescent signals were observed only in the nucleus (Fig. 8A, B). With the control vector alone, GFP signals were distributed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 8C). These results indicated that PhERF2 and PhERF3 are indeed nuclear-localized proteins, which is consistent with their predicted function as transcription factors.

Fig. 8.

Subcellular localization of PhERF2 and PhERF3 proteins. (A) Nuclear localization of GFP–PhERF2 fusion protein in onion epidermal cells. (B) Nuclear localization of GFP–PhERF3 fusion protein in onion epidermal cells. (C) Onion epidermal cells transformed with a translational construct of GFP as a positive control showed localization throughout the cell, with the strongest signals in the cytoplasm and nucleus. GFP fluorescence (left panel) and differential contrast imagery (right panel) were compared. The positions of nuclei are indicated by arrows. The scale bars indicate 100 μm.

Discussion

Flower senescence is associated with increased ethylene production in many flowers (Borochov and Woodson, 1989). In this study, 13 members of the AP2/ERF superfamily were identified from petunia. In Arabidopsis, 122 of the 147 genes identified as possibly encoding AP2/ERF domain(s) have been assigned to the ERF family, and the Arabidopsis ERF family was then classified into 12 groups, groups I–X, VI-L, and Xb-L (Nakano et al., 2006). The 13 PhERFs fall into four out of the12 different groups of the previously characterized ERF proteins (Fujimoto et al., 2000; Tournier et al., 2003; Nakano et al., 2006) (Fig. 2).

PhERF1 belongs to group V ERFs, which share two motifs, CMV-1 and CMV-2, in the C-terminal regions. PhERF2–PhERF5 belong to group VII ERFs. PhERF2–PhERF4 proteins shared the CMVII-1 motif while PhERF5 did not include this motif. PhERF6–PhERF8 belong to group VIII ERFs. The three predicted proteins comprise two motifs, EAR and CMVIII-2. The ERFs of tobacco, Arabidopsis, and rice, which contain the CMVIII-1 and CMVIII-2 motifs, have been shown to repress GCC box-mediated transcription via a transient assay (Fujimoto et al., 2000; Ohta et al., 2000, 2001). In addition, AtERF4 was shown to be a negative regulator in the expression of ethylene-, jasmonate-, and ABA-responsive genes (McGrath et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2005), and AtERF7 was shown to play an important role in ABA response in plants (Song et al., 2005). PhERF9–PhERF13 belong to group IX ERFs that have been shown to function as activators of transcription (Solano et al., 1998; Fujimoto et al., 2000; Tournier et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2007).

In addition, the ERF family is also grouped into two major subfamilies, ERF conserving the 14th alanine (A14) and the 19th aspartic acid (D19), and CBF/DREB in which valine (V14) and glutamic acid (E19) are present at the respective positions (Yang et al., 2002; Sakuma et al., 2002; Tournier et al., 2003; Nakano et al., 2006). The predicted amino acid sequences of PhERF2–PhERF13 contain A14 and D19, indicating that they belong to the ERF subfamily, and that of PhERF1 has V14 and H19, indicating that it belongs to the DRE subfamily.

In the present study, PhERF mRNAs, with the exception of PhERF11, which was below the detection limits in corollas and gynoecia, were present at different levels in different tissues and stages of petunia flower, and showed different responses to exogenous ethylene, indicating that their expression is spatially regulated. In particular, PhERF6 in corollas did not respond to exogenous ethylene but in gynoecia it increased gradually after ethylene, the expression of PhERF8 increased slightly from 24 h to 72 h but in gynoecia showed a constitutive expression, and that of PhERF10 in corollas increased gradually after ethylene but in gynoecia it did not respond to exogenous ethylene (Figs 4, 5).

In the ERF gene family, subfamilies III and IV have been associated with the stress response (Novillo et al., 2004; Sakuma et al., 2006; Qin et al., 2008), while subfamilies VII, VIII, and IX contain members that are ethylene responsive (Gu et al., 2000; Tournier et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2005; Onate-Sanchez et al., 2007; Champion et al., 2009; Yin et al., 2010). Subfamily VII genes have been particularly associated with fruit ripening and senescence; for example, the tomato LeERF2 (Tournier et al., 2003) and apple MdERF1 (Wang et al., 2007) genes accumulate during fruit ripening, plum PsERF2a and PsERF2b (El-Sharkawy et al., 2009) genes accumulate in flowers after fertilization, and kiwifruit AdERF4 and AdERF6 were markedly stimulated at the later fruit senescence stage (Yin et al., 2010). In this study, most PhERF genes, with the exception of PhERF11, showed increases in corollas or gynoecia after exogenous ethylene treatment (Figs 4, 5), which supported that subfamilies VII, VIII, and IX contain members that are ethylene responsive. In addition, PhERF2–PhERF5 which are group VII members, and in particular PhERF2 and PhERF3, showed a strong association with the rise in ethylene production in both petals and gynoecia, which was confirmed by a reduction in expression with STS treatment and the positive response to exogenous ethylene (Figs 4–6), a pattern that has been observed for some senescence-related genes, such as SR8 and SR12 in carnation (Lawton et al., 1989; Jones et al., 1995; Verlinden et al., 2002). This pattern of mRNA accumulation would also be expected of a gene regulating ethylene responsiveness and therefore timing of petal senescence. Therefore, PhERF2 and PhERF3 might be associated particularly with flower senescence in petunia. Future studies demonstrating functionality through in vitro and in vivo experiments including transgenic plants should confirm this.

It should be pointed out that several PhERF genes, for example PhERF12 and PhERF13, decreased during natural flower senescence, when ethylene production increased gradually, but increased with exogenous ethylene treatment (Figs 4, 5). This suggested that these PhERF genes were regulated not only by ethylene, but also by other factors. Similarly, kiwifruit AdERF1, AdERF7, AdERF11, and AdERF12 transcripts were slightly higher directly after harvest in control fruit and then declined during ripening (Yin et al., 2010).

Exogenous application of ABA accelerates flower senescence in ethylene-sensitive plants such as petunia (Vardi and Mayak 1989) and in ethylene-insensitive plants such as daylily (Panavas et al., 2000). The endogenous content of ABA increases during senescence in several flowers (Serrano et al., 1999; Hunter et al., 2004). ABA treatment increased ethylene production of the Rosa flower (Müller et al., 1999). In this study, PhERF1–PhERF5, PhERF7, and PhERF8 transcripts were increased by both ABA and ethylene (Fig. 7) and it is possible that these genes respond to ABA in an ethylene-dependent manner. The increase in transcripts of PhERF2–PhERF5 of group VII due to ABA treatment was consistent with the accelerating flower senescence caused by ABA treatment, which strengthens the idea that PhERF2–PhERF5 of group VII are actively involved in flower senescence.

In Arabidopsis, the expression of AtERF4 and AtERF7, members of group VIII, can be induced by ABA and were shown to play an important role in ABA response in plants (McGrath et al., 2005; Song et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2005). The expression of PhERF6, also a member of group VIII, which was not affected by ethylene, was increased by ABA (Fig. 7), showing that it might not respond to ABA in an ethylene-dependent manner. It is worth mentioning that the expression of three members of group IX, PhERF10, PhERF12, and PhERF13, which increased by ethylene treatment but decreased during natural flower senescence, was decreased by ABA treatment (Fig. 7), showing that the decrease in the transcripts of these gene during natural flower senescence might be associated with the increase in endogenous ABA of corellas in petunia (Vardi and Mayak, 1989). In addition, in the three members of group IX of soybean, GmERF069 was subjected to negative regulation by ABA, while GmERF061 and GmERF079 increased after ABA treatment (Zhang et al., 2008).

Treatment with auxin is useful to reduce drop of flower bracts in Bougainvillea (Chang and Chen, 2001). 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid is effective in improving post-harvest life of cut Eustoma flowers (Shimizu-Yumoto and Ichimura, 2010). In plum fruits, the high levels of accumulation of PsERF2a, PsERF2b, PsERF3a, and PsERF12 might be enhanced in an auxin-dependent manner (El-Sharkawy et al., 2009). In this study, treatment with the auxin IAA increased expression of most of the PhERF genes, with the exception of PhERF13 (Fig. 7), showing the direct or indirect response of PhERF genes of group VII, VIII, and IX to IAA.

SA can interfere with the biosynthesis and action of ethylene in plants (Raskin, 1992) and delay the ripening of some fruits, probably through inhibition of ethylene biosynthesis or action (Srivastava and Dwivedi, 2000; Zhang et al., 2003). However, in Arabidopsis the AtACS7 promoter was responsive to SA; treatment with SA increased the expression of AtACS7 (Tang et al., 2008). In this study, the expression of PhERF2, PhERF3, PhERF8, PhERF9, and PhERF10, as with ethylene treatment, increased after SA treatment (Fig. 7), which supported a positive interaction between SA and ethylene in petunia flower. Similarly, in soybean leaf, the expression levels of nine GmERF genes, belonging to groups V, VI VII, VIII, IX, and X, were all induced and increased after SA treatment (Zhang et al., 2008).

Jasmonates have been shown to be powerful promoters of plant senescence and there is some evidence that jasmonic acid (JA) or MeJA may promote senescence via ethylene (Sembdner and Parthier, 1993; Emery et al., 1996; Hung, 2006). In Arabidopsis, 10 members of the AP2/ERF family, primarily from the VIII and IX subclusters, were induced by both a pathogen and MeJA (McGrath et al., 2005). AtERF4 of group VIII acts as a negative regulator of JA-responsive defence gene expression and antagonizes JA inhibition of root elongation (McGrath et al., 2005). In contrast, AtERF2 of group IXa is a positive regulator of JA-responsive defence genes and enhances JA inhibition of root elongation (McGrath et al., 2005). In this study, MeJA treatment increased the levels of mRNA of all the four group VII PhERF genes, PhERF2–PhERF5, three group VIII PhERF genes, PhERF6–PhERF8, and PhERF1 in corollas (Fig. 7). The transcript increases of PhERF2–PhERF5 of group VII by MeJA were consistent with the accelerating flower senescence caused by MeJA treatment, which supported that PhERF2–PhERF5 of group VII are actively involved in flower senescence. It is not clear whether the response of PhERF1, PhERF6, PhERF7, and PhERF8 to JA depended on ethylene production. Also, for JA treatment, the expression of nine GmERF genes in soybean leaf all increased (Zhang et al., 2008).

Exogenous treatments with cytokinin may delay senescence of cut flowers (Cook et al., 1985; Van Staden et al., 1990; Lukaszewska et al., 1994). Overproduction of cytokinins in petunia flowers transformed with PSAG12-IPT delays corolla senescence and decreases sensitivity to ethylene (Chang et al., 2003). In plum, PsERF1a, PsERF1b, PsERF3a, and PsERF12 transcription levels were accelerated in response to cytokinin application, PsERF2a and PsERF3b were negatively regulated by the treatment, and PsERF2b did not respond significantly (El-Sharkawy et al., 2009). However, in this study, when treated with BA, the transcripts of PhERF1–PhERF13 all accumulated in a constitutive manner and did not respond to BA (Fig. 7). The difference between the responses of ERF genes of the two plants to BA need to be researched in the future.

Sucrose is a global regulator of growth and metabolism that is evolutionarily conserved in plants (Smeekens, 2000; Rolland et al., 2001). Sucrose has also been shown to decrease ethylene responsiveness in carnation petals, and sugars are known to extend the vase-life of flowers (Verlinden and Garcia, 2004). Sucrose prevented up-regulation of senescence-associated genes in carnation petals (Hoeberichts et al., 2007). In this study, after 5% sugar treatment, the amount of PhERF2, PhERF3, and PhERF7 transcripts increased slightly, and that of PhERF4, PhERF9, and PhERF10 decreased at 6 h and 24 h (Fig. 7), which showed that some PhERF genes might respond to sugar treatment and play a role in flower senescence.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Figure S1. Amino acid sequence alignment of group V ERFs (a) PhERF1, At1g15360/SHN1, At5g11190/SHN2, and At5g25390/SHN3; (b) PhERF2, PhERF3, PhERF4, At1g53910/RAP2.12, and At3g14230/RAP2.2; and (c) PhERF6, PhERF7, PhERF8, At1g28370/AtERF11, At1g50640/AtERF3, and At1g53170/AtERF8 using the DNAMAN program.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30800758 and 30972410) and the Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation (104031).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ABA

abscisic acid

- BA

6-benzylaminopurine

- ERF

ethylene-responsive element-binding factor

- IAA

indole-3-acetic

- JA

jasmonic acid

- MeJA

methyl jasmonate

- RACE

rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- SA

salicylic acid

- STS

silver thiosulphate

- TF

transcription factor

References

- Abeles FB, Morgan PW, Salveit MEJ. Ethylene in plant biology. 2nd edn. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Borochov A, Woodson WR. Physiology and biochemistry of flower petal senescence. Horticultural Reviews. 1989;11:15–43. [Google Scholar]

- Champion A, Hebrard E, Parra B, Bournaud C, Marmey P, Tranchant C, Nicole M. Molecular diversity and gene expression of cotton ERF transcription factors reveal that group IXa members are responsive to jasmonate, ethylene and Xanthomonas. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2009;10:471–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Jones ML, Banowetz GM, Clark DG. Overproduction of cytokinins in petunia flowers transformed with PSAG12:IPT delays corolla senescence. Plant Physiology. 2003;132:2174–2183. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.023945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YS, Chen HC. Variability between silver thiosulfate and 1-naphthaleneacetic acid applications in prolonging bract longevity of potted bougainvillea. Scientia Horticulturae. 2001;87:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Cook D, Rasche M, Eisinger W. Regulation of ethylene biosynthesis and action in cut carnation flower senescence by cytokinins. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 1985;110:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sharkawy I, Sherif S, Mila I, Bouzayen M, Jayasankar S. Molecular characterization of seven genes encoding ethylene-responsive transcriptional factors during plum fruit development and ripening. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2009;60:907–922. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RJN, Reid DM. Methyl jasmonate effects on ethylene synthesis and organ specific senescence in Helianthus annuus seedlings. Plant Growth Regulation. 1996;18:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto SY, Ohta M, Usui A, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box-mediated gene expression. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:393–404. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni JJ. Genetic regulation of fruit development and ripening. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:170–180. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu YQ, Yang CM, Thara VK, Zhou JM, Martin GB. Pti4 is induced by ethylene and salicylic acid, and its production is phosphorylated by the Pto kinase. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:771–785. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens RP, Edwards AE, Leyland NR, Bean S, Mullineaux P. pGreen: a versatile and flexible binary Ti vector for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;42:819–832. doi: 10.1023/a:1006496308160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeberichts FA, van Doorn WG, Vorst O, Hall RD, van Wordragen MF. Sucrose prevents up-regulation of senescence-associated genes in carnation petals. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:2873–2885. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung KT, Hsu YT, Kao CH. Hydrogen peroxide is involved in methyl jasmonate-induced senescence of rice leaves. Physiologia Plantarum. 2006;127:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DA, Ferrante A, Vernieri P, Reid MS. Role of abscisic acid in perianth senescence of daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus ‘Dutch Master’) Physiologia Plantarum. 2004;121:313–321. doi: 10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.0311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iordachescu M, Verlinden S. Transcriptional regulation of three EIN3-like genes of carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus L. cv. Improved White Sim) during flower development and upon wounding, pollination, and ethylene exposure. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2005;56:2011–2018. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ML, Larsen PB, Woodson WR. Ethylene-regulated expression of a carnation cysteine proteinase during flower petal senescence. Plant Molecular Biology. 1995;28:505–512. doi: 10.1007/BF00020397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton KA, Huang B, Goldsbrough PB, Woodson WR. Molecular cloning and characterization of senescence-related genes from carnation petals. Plant Physiology. 1989;90:690–696. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.2.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukaszewska AJ, Bianco J, Barthe P, Le Page-Degivry T. Endogenous cytokinin in rose petals and effect of exogenously applied cytokinins on flower senescence. Plant Growth Regulation. 1994;14:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ma N, Tan H, Liu XH, Xue JQ, Li YH, Gao JP. Transcriptional regulation of ethylene receptor and CTR genes involved in ethylene-induced flower opening in cut rose (Rosa hybrida) cv. Samantha. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:2763–2773. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath KC, Dombrecht B, Manners JM, Schenk PM, Edgar CI, Maclean DJ, Scheible WR, Udvardi MK, Kazan K. Repressor- and activator-type ethylene response factors functioning in jasmonate signaling and disease resistance identified via a genome-wide screen of Arabidopsis transcription factor gene expression. Plant Physiology. 2005;139:949–959. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.068544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller R, Stummann BM, Andersen AS, Serek M. Involvement of ABA in postharvest life of miniature potted roses. Plant Growth Regulation. 1999;29:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Suzuki K, Fujimura T, Shinshi H. Genome wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiology. 2006;140:411–432. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.073783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novillo F, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Salinas J. CBF2/DREB1C is a negative regulator of CBF1/DREB1B and CBF3/DREB1A expression and plays a central role in stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2004;101:3985–3990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303029101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. Ethylene-inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. The Plant Cell. 1995;7:173–182. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M, Matsui K, Hiratsu K, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. Repression domains of class II ERF transcriptional repressors share an essential motif for active repression. The Plant Cell. 2001;13:1959–1968. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M, Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. Three ethylene responsive transcription factors in tobacco with distinct transactivation functions. The Plant Journal. 2000;22:29–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onate-Sanchez L, Anderson JP, Young J, Singh KB. AtERF14, a member of the ERF family of transcription factors, plays a nonredundant role in plant defense. Plant Physiology. 2007;143:400–409. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panavas T, LeVangie R, Mistler J, Reid PD, Rubinstein B. Activities of nucleases in senescing daylily petals. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2000;38:837–843. [Google Scholar]

- Park JM, Park CJ, Lee SB, Ham BK, Shin R, Peak KH. Overexpression of the tobacco Tsi1 gene encoding an EREBP/AP2-type transcription factor enhances resistance against pathogen attack and osmotic stress in tobacco. The Plant Cell. 2001;9:49–60. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.5.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:2002–2007. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Sakuma Y, Tran LSP, Maruyma K, Kidokoro S, Fujita Y, Fujita M, Umezawa T, Sawano Y, Miyazono KI. Arabidopsis DREB2A-interacting proteins function as RING E3 ligases and negatively regulate plant drought stress-responsive gene expression. The Plant Cell. 2008;20:1693–1707. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin I. Role of salicylic acid in plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1992;43:439–463. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland F, Winderickx J, Thevelein JM. Glucose-sensing mechanisms in eukaryotic cells. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2001;26:310–317. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01805-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y, Liu Q, Dubouzet JG, Abe H, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaka K. DNA-binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of Arabidopsis DREBs, transcription factors involved in dehydration- and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2002;290:998–1000. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y, Maruyama K, Qin F, Osakabe Y, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi- Shinozaki K. Dual function of an Arabidopsis transcription factor DREB2A in water-stress-responsive and heat-stress-responsive gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2006;103:18822–18827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605639103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sembdner G, Parthier B. The biochemistry and physiological and molecular actions of jasmonates. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biolog y. 1993;44:569–589. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M, Martinez-Madrid MC, Romojaro F. Ethylene biosynthesis and polyamine and ABA levels in cut carnations treated with aminotriazole. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 1999;124:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya K, Barry KG, Ciardi JA, Loucas HM, Underwood BA, Nourizadeh S, Ecker JR, Klee HJ, Clark DG. The central role of PhEIN2 in ethylene responses throughout plant development in petunia. Plant Physiology. 2004;136:2900–2912. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu-Yumoto H, Ichimura K. Combination pulse treatment of 1-naphthaleneacetic acid and aminoethoxyvinylglycine greatly improves postharvest life in cut Eustoma flowers. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2010;56:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Smeekens S. Sugar-induced signal transduction in plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;51:49–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker JR. Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes and Development. 1998;12:3703–3714. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song CP, Agarwal M, Ohta M, Guo Y, Halfter U, Wang P, Zhu JK. Role of an Arabidopsis AP2/EREBP-type transcriptional repressor in abscisic acid and drought stress responses. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:2384–2396. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava MK, Dwivedi UN. Delayed ripening of banana fruit by salicylic acid. Plant Science. 2000;158:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9452(00)00304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang XN, Chang L, Wu SA, Li P, Liu G, Wang NN. Auto-regulation of the promoter activities of Arabidopsis 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase genes AtACS4, AtACS5, and AtACS7 in response to different plant hormones. Plant Science. 2008;175:161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Tournier B, Sanchez-Ballesta MT, Jones B, Pesquet E, Regad F, Latché A, Pech JC, Bouzayen M. New members of the tomato ERF family show specific expression pattern and diverse DNA-binding capacity to the GCC box element. FEBS Letters. 2003;550:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Staden J, Upfold SJ, Bayley AD, Drewes FE. Cytokinins in cut carnation flowers. IX. Transport and metabolism of iso-pentenyladenine and the effects of its derivatives on flower longevity. Plant Growth Regulation. 1990;9:255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Vardi Y, Mayak S. Involvement of abscisic acid during water stress and recovery in petunia flowers. Acta Horticulturae. 1989;261:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Veen H. Silver thiosulfate: an experimental tool in plant science. Scientia Horticulturae. 1983;181:155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Verlinden S, Boatright J, Woodson WR. Changes in ethylene responsiveness of senescence-related genes during carnation flower development. Physologia Plantarum. 2002;116:503–511. [Google Scholar]

- Verlinden S, Garcia JJV. Sucrose loading decreases ethylene responsiveness in carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus cv. White Sim) petals. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2004;31:305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, Tan D, Takahashi A, Li TZ, Harada T. MdERFs, two ethylene-response factors involved in apple fruit ripening. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:3743–3748. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson JQ, Lanahan MB, Clark DG, Bleecker AB, Chang C, Meyerowitz EM, Klee HJ. A dominant mutant receptor from Arabidopsis confers ethylene insensitivity in heterologous plants. Nature Biotechnology. 1997;15:444–447. doi: 10.1038/nbt0597-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltering EJ, Van Doorn WG. Expand+Role of ethylene in senescence of petals—morphological and taxonomical relationships. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1988;39:1605–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Woodson WR, Lawton KA. Ethylene-induced gene expression in carnation petals. Relationship to autocatalytic ethylene production and senescence. Plant Physiology. 1988;87:473–503. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.2.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HJ, Shen H, Chen L, Xing YY, Wang ZY, Zhang JL, Hong MM. The OsEBP-89 gene of rice encodes a putative EREBP transcription factor and is temporally expressed in developing endosperm and intercalary meristem. Plant Molecular Biology. 2002;50:379–791. doi: 10.1023/a:1019859612791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YW, Wu Y, Deng W, Pirrello J, Regad F, Bouzayen M, Li ZG. Silencing Sl-EBF1 and Sl-EBF2 expression causes constitutive ethylene response phenotype, accelerated plant senescence, and fruit ripening in tomato. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:697–708. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Tian L, Latoszek-Green M, Brown D, Wu K. Arabidopsis ERF4 is a transcriptional repressor capable of modulating ethylene and abscisic acid responses. Plant Molecular Biology. 2005;58:585–596. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-7294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Allan AC, Chen K, Ferguson IB. Kiwifruit EIL and ERF genes involved in regulating fruit ripening. Plant Physiology. 2010;153:1280–1292. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Chen M, Chen X, Xu Z, Guan S, Li L-C, Li A, Guo J, Mao L, Ma Y. Phylogeny, gene structures, and expression patterns of the ERF gene family in soybean (Glycine max L.) Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008;59:4095–4107. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen KS, Zhang SL, Ferguson L. The role of salicylic acid in postharvest ripening of kiwifruit. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2003;28:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Tang X, Martin GB. The Pto kinase conferring resistance to tomato bacterial speck disease interacts with proteins that bind a cis-element of pathogenesis-related genes. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:3207–3218. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.