Abstract

This study examines the educational consequences for those children of emigrants who are left behind in Fujian Province, China. Specifically, we compare the school enrollment for children from emigrant households with the school enrollment for children from non-emigrant households. The data are drawn from the 1995 China 1% Population Sample Survey. We find consistent evidence that emigration affects educational opportunity for children in a positive way. First, children from emigrant households are more likely to be enrolled in schools than children from non-emigrant households. Second, emigration also has positive consequences in reducing gender gap in education. Although girls from non-emigrant households still experience a lower enrollment rate, for the emigrant households the overall school enrollment for boys and girls has been approaching convergence.

Since the beginning of a market transition in 1978, China has sent a salient number of migrants to a multitude of different foreign destinations. One of the social consequences of this emigration is the issue with education of children who are left behind in migrant-sending communities. It is not uncommon for children to live in their hometowns with only one of their parents or with other relatives or family members. Until recently, there was speculation about the educational consequences of these single parent emigrant households. As the educational attainment of children is a compelling indicator of their future upward socio-economic mobility, it is of utmost concern for parents, and especially for those living apart because of emigration.

The issue of education of migrant children who are left behind has been a topic of research in other contexts. For example, in the case of Mexico, Kandel and Massey (2002) contend that children from households with a significant cultural influence pushing towards migration to the United States have a higher likelihood of abandoning their plans of pursuing an education in their native country. As such, children tend to drop out of school because their motivation is diluted, with the greatest concentration of effort directed towards moving abroad. We are interested in investigating whether or not this argument holds true for similar emigrant households in China and have chosen Fujian Province for this purpose. In addition, we reveal the salient factors that facilitate educational attainment through empirical analysis, as well as the consequences of the emigration of parents or household members and how they impact educational opportunity of the children.

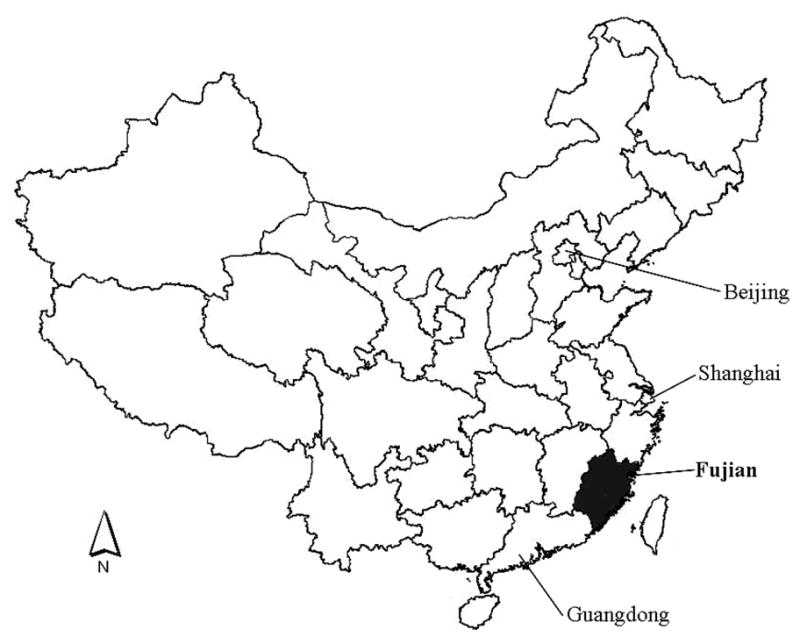

The primary focus of this study is the examination of the educational consequences of emigration for children in China, particularly in Fujian Province, located in the southeastern coastal region. Specifically, we will compare the school enrollment status in compulsory education for children from emigrant households to that of children from non-emigrant households. An examination of this issue is not quite straightforward because data on left behind children are often not unavailable. Fortunately, the 1995 China 1% Population Sample Survey contains relevant information that allows us to conduct this research.

MIGRATION AND EDUCATION OF MIGRANT CHILDREN

Derived from the findings from the study of Mexican emigration by Kandel and Massey (2002), we suggest that the children of emigrants intentionally leave school and commence language training in China in order to more smoothly adjust into schools abroad. We develop hypotheses that reflect both potentially positive and negative impacts on children from households with emigrants. Emigrants from Fujian Province tend to leave their spouses and children in their hometown or with relatives, because many of them still do not possess permanent residency in their destination country. As for migration from villages in Mexico, close to 50 percent of Mexican men migrate to the United States leaving their family members in their village (Cerrutti and Massey, 2001). The similar trend has been observed in the case of internal migration within China that migrant parents go on their destination entrusting their children to the elderly in their place of origin (Murphy, 2000; Roberts, 2002). Murphy documented through her fieldwork conducted in Western China that migrant parents often place their children under care of grandparents in the community so that they can go back to work in the city as short as half a year after childbearing. As a result, there is a practice in the community for the elderly to help raise the children of migrants, sometimes taking care of them reluctantly. Thus, we argue that the trend that migrants leave their children with relatives in their place of origin could be rather a common practice. Children and spouse may come in a later period of time once emigrants get settled in their destination.

Remittances from emigrants abroad are key resources in enabling their families to avoid poverty, while simultaneously enriching the household’s financial resource and establishing the premise for upward mobility with regard to their socioeconomic status in their local community (Liang, 2001). Kandel and Kao (2000) assert that the remittances from emigrants enhance positive educational outcomes, particularly for younger children. Curran et al. (2004) substantiate that remittances from migrants contribute significantly to raising educational opportunities for girls to a level closer to those for boys. Benefits of higher income would be likely to result in releasing children, especially those in rural areas, from obligatory labor by hiring temporary migrant farmers and providing ample educational opportunities as well as better health and nutrition for their children (Kandel and Kao, 2001). In fact, higher remittances resulting from high levels of emigration contribute to improving the overall well-being of children in their communities of origin (Kanaiaupuni and Donato, 1999). Furthermore, one of the benefits of the emigrant parent’s absence is that it seems to promote a greater sense of independence for these children. It has also been suggested that children from households with a history of emigration are more likely to emigrate by following their network.

On the other hand, there are also indications that migration could have a negative impact on the education of children. There are disadvantages in earning higher income such that some members of their communities of origin may come to rely heavily on remittances from emigrants rather than actively establishing investment and development. Spending money on children’s education may not be the first priority for some people, even though they have high income most likely gained from remittances. It is possible, then, that these households may spend the remittances on capital goods in addition to housing and consumer products instead of investing in the education, and the future, of their children (Croll and Ping, 1997; Durand et al., 1996; Massey, 1988; Taylor et al., 1996). Nevertheless the obvious benefits of earning high income do not always bring parity. Remittances induce some degrees of envious feeling among the locals in a community and discourage them from working due to an idea of relative deprivations (Russell, 1986). Households with a history of remittances put themselves at greater risk of envy and even harm from their neighbors, relatives, or both, particularly for those households located in rural communities. For children, they could become a target for hazing and bullying at school.

Moreover, the absence of parents could generate more harm than good because parents residing abroad are greatly compromised in terms of being less able to give sufficient attention to their children or to maintain adequate control over them. Children, for example, may feel emotionally distanced and fall prey to being teased by other children at school and in their neighborhoods. To that end, with an increased sense of loneliness concomitant with elevated stress levels, these children may begin to experience emotional and behavioral problems, especially during adolescence. Health concerns also increase. According to Dawson (1991), children from single parent households are physically more vulnerable where accidental injury and asthma are top sources of anxiety for the children of divorced or single parents, respectively.

The negative effects can be especially poignant in cases where children have changed schools and simultaneously received less parental involvement (Astone and McLanahan, 1991; Hagen et al., 1996). Not only do children in single parent households or households in which a stepparent, grandparents, or other family members have assumed parental roles and responsibilities, show relatively lower educational performance and aspirations, these children also have a propensity to cause problems at school (Coleman, 1988; Astone and McLanahan, 1991; Dawson, 1991; Jonsson and Gahler, 1997; Thomson et al., 1994). Thus, the impact of parental absence can be severe, particularly for preschool children and especially for boys than for girls (Krein and Beller, 1988). Consequently, when compared to children from households in which both parents are present, children from single parent households face a higher risk of early withdrawal from school; even greater is the risk for children living with stepfamilies (Astone and McLanahan, 1994; Pong, 1996). On the contrary, Pong (1996) simultaneously states that strong kinship positively matters on enrollment as well as performance of children in school. When a household is tightly united and appropriate material support is offered, it makes disadvantages disappear.

As children plan to emigrate to be reunited with their parents abroad in the near future, they may become discouraged from furthering their education in their home countries because the new host society may underrate the value of education acquired in migrant-sending countries (Kandel and Kao, 2001). Also, it is possible that the majority of children of emigrants in Fujian who go to local schools are insufficiently prepared to enter schools abroad, because a high percentage of them reside in rural part of the province and their household head is more likely to possess substantially low educational attainment level. The situation may be particularly applicable to children who are entering the labor market on their arrival in migrant-receiving countries. In this case then, these children may focus on English language training rather than on academics. Those types of thoughts could result in a sanctioning of the neglect of the children’s educational needs by their legal guardians and often inevitably cause a delay or termination of their primary or secondary education.

The Case of Fujian Province

Fujian Province has a population of nearly 35 million and is located in the southeastern part of the country, along the coastline of the East China Sea across from Taiwan. The province is heretofore considered one of the principal emigrant-sending provinces in China, with a dramatic increase in the number of emigrants leaving Fujian over the last twenty years. In 1995, emigrants from Fujian made up approximately 28 percent of the entire emigrant population from China (Liang, 2001). One of the distinctive features of Fujian emigration is a highly structured transnational organization known as the snakeheads. This organization has developed an immense network that engages in the clandestine business of human smuggling, imposing transport fees that normally range between $47,000 and $65,000 in U.S. currency (Holmes, 1998; Liang, 2001). Transport fees steadily rise year after year. A significant proportion of these Fujianese emigrants eventually arrive in North America, in particular to New York City’s Chinatown, via various risky relay points with the promise of jobs in Chinese restaurants or as garment industry laborers.

One would wonder what motivates these individuals to undertake emigration with the inherent risks and concomitant hardships. Liang (2001) contends that one of the strongest motivations compelling the Fujianese to leave for destinations abroad is the relative deprivation which is heightened when viewed against the backdrop of the magnitude of foreign money they witness being brought back to their province by those who have dared to emigrate. Their hope is that they, too, may be able to realize the dream of great financial success by going abroad, a dream which fuels their desire to emigrate. Eluding poverty is less likely to be the reason for the Fujianese to emigrate because Fujian Province is located on the coastline region that enjoys economic parity from a China’s market-oriented economy in recent few decades. The increase of emigration from Fujian began concomitantly with China’s transition to a more market-oriented economy, which in and of itself, resulted in a dramatic increase in the amount of foreign capital investments in China.

As international migration has become a progressively less selective process for the Fujianese, so have the socio-demographic characteristics of these emigrants changed. Consequently, a change in the patterns in the place of origin among the emigrant population from city to countryside occurred in the early 1990s. It is obvious then that not only has the educational attainment profile of emigrants from Fujian Province become much lower but also the overall socio-economic status of these emigrants is significantly worse than that of emigrants from other popular emigrant-sending areas in China, such as Beijing and Shanghai. As such, the socio-demographic profiles of Fujianese emigrants in 1995 were comprised mainly of young males from rural areas, over 60% of whom were married with the majority leaving their family members in their place of origin (Liang, 2001).

In addition to a rapid increase in the number of emigrants from Fujian over the last twenty years rendering its status as the number one emigrant-sending province in China, the uniqueness of Fujianese emigrants, when compared to those from other popular emigrant-sending areas, is attributable to the large number of married male emigrants going abroad leaving the equally large number of children behind. Moreover, there is a discernable difference in the increasing number of new, very handsomely appointed homes, which have recently been built in Fujian with the help of the remittances sent back by emigrants. To this end, we endeavored to examine the association between household wealth and children’s educational attainment and the ensuing opportunities for advancement; hence, the unique type of emigration in addition to widespread community-level trends makes Fujian Province ideal as the focus of this study.

DATA AND METHODS

Data for this study were drawn from the Fujian portion of the 1995 China 1% Population Sample Survey (China Population Sample Survey Office, 1997), which is the successor of the first nationally represented sample survey, the 1987 Population Sample Survey. The dataset includes information necessary to capture the characteristics in population movements within and from China. It contains a great number of socio-demographic information by household registration and is believed to have included the number of both documented and undocumented emigrants (Liang, 2001). As the majority of emigrants from Fujian are considered undocumented, we do not believe that legal status induces a potential bias to the results. We first determine if an individual is in suspended household registration status. It reflects the fact that at least one family member in the household was residing abroad at the time the survey was conducted. After determining this, we can then successfully identify households that have produced emigrants at any time. In measuring the influence of school enrollment status for children, we focus on students in the first through the ninth grades (i.e., elementary and junior high school levels), which are considered the minimum level of education under China’s Compulsory Education Law (PRC, 1998). Thus, we identify and select children between the ages of 6 and 15 years who fall within this compulsory education framework and should be enrolled in school by government regulations.1 In terms of the relationship with the head of household variable, we include any individual who falls within the specific age category for which we can assume he or she is a child, grandchild, or any other variation of the definition of dependent minor. In order to accommodate “children of emigrants” in the broadest possible sense, we attempt to accommodate children staying with their grandparents, uncles, aunts, or other family members. These children are then separated into two groups divided by whether or not they belong to an emigrant or non-emigrant household; at which point they are again grouped by enrollment status. Children registered as household heads, as well as those originating from institutional households, are excluded from this study.

We would like to stress that the dataset we used in this project is a 1% sample; in addition, the version that we have is actually a 50% of the 1% sample dataset. However, compared to alternative data sources, our dataset is preferable. Some may be wondering if our research endeavor would be better served if we were to use micro-level data from the 2000 Chinese Population Census. The answer is no. The version of the micro-level data from the 2000 Chinese Population Census, provided to selected number of researchers by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, is a 1/1000 sample. As it turned out, the 2000 Chinese Census is certainly more updated, but the dataset generated a much smaller number of international migrants from Fujian Province than our sample from the 1995 China 1% Population Sample Survey. Thus, until other alternative data sources become available, the 1995 China 1% Population Sample Survey is probably the most appropriate choice for our purpose.

Because our dependent variable is dichotomous (i.e., enrolled or not enrolled in school), the multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the likelihood of the effect of various socio-demographic factors on the school enrollment status of children within the compulsory education framework in Fujian Province. The explanatory factors incorporated for our models include: gender and age of a child, the presence of any emigrants in a household, the relationship of these emigrants to the household’s children, the educational attainment level of the household head, and finally, place of residence. Age was treated as a continuous variable. Because of the explicit male dominance in the demographic profiles of Fujianese emigrants, it is presumably meaningful to categorize the household relationship of emigrants with children into the three groups: (1) father and/or mother (parent) emigrants; (2) a relative in the household other than the parent(s) of the children; and (3) households in which no emigrants are present. It is noteworthy to mention that a male emigrant is often recorded as a spouse and wife of the emigrant as a household head in household registration. The educational attainment levels of the head of household are grouped into four categories: (1) those without formal education; (2) those with an elementary school education; (3) those with a junior high school education; and (4) those with at least high school education. It should be noted that we separated the last category into high school and college-educated groups for the descriptive tables. Place of residence is comprised of three distinct locations: city, town, and rural.

As our interest expanded to estimate the effect of household wealth on school enrollment and the educational opportunities available to children, in Model 4 we added to the overall model the factors that reflect household wealth, for example, the total housing area in square meters. Though public education is accessible at no cost for children whose parents possess local hukou, we hypothesize that the cost of school supplies and other goods such as uniforms, satchels, and stationery along with associated fees may pose a significant financial strain for low-income households. Therefore, the affordability of such items may indeed influence school enrollment. To this end, a lack of capital, in part, may result in the delayed entrance to or early withdrawal from school for children of low-income households. We selected the first two factors because we determined that such housing characteristics proportionally reflected the wealth of a household and could, therefore, be considered reasonable indicators of household wealth given a lack of an ideal measure of wealth. We selected the number of children in the school age group as a variable in light of the hypothesis that in families where there are siblings, resources may be diluted which leads to lower school enrollment. The total housing area and the number of rooms in the house are transformed into the natural logarithms of the raw count upon inclusion in the logistic regression model. When we consider housing characteristics, we exclude institutional households and any observations that indicated the total housing area and the number of rooms in a house as zero.

RESULTS

Of the 40,777 children initially considered for this study, 34,678 children were enrolled in school whereas 6,099 children were not. Counts for the children of emigrants and non-emigrants extracted from the sample were 270 and 40,507, respectively; 91 percent of the 270 children from households with emigrants were reportedly enrolled in school when compared to an 85 percent enrollment rate for children of non-emigrant households. As evidenced in this dataset, children of emigrants appear to have higher overall percentage of school enrollment rates.

The socio-demographic profiles of children from households with and without emigrants are shown in Table 1. Table 1 provides the distributions within a category of each variable by school enrollment status and the presence of emigrants in households. A large proportion of adults achieved between an elementary and junior high school level education and the majority were rural residents. Among 40,507 cases of children from non-emigrant households, 7,880 (19.3%) cases were confirmed as missing values for the total housing area and the number of rooms in a house.

TABLE 1.

Socio-Demographic Profiles of Children from Households with and without Emigrants in Fujian Province by School Enrollment Status, 1995 (Column Percentages)

| Variables | Children of emigrants |

Children of non-emigrants |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled (%) | Not enrolled (%) | Enrolled (%) | Not enrolled (%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Boy | 52.0 | 54.2 | 53.2 | 42.8 |

| Girl | 48.0 | 45.8 | 46.8 | 57.2 |

| Age | ||||

| 6–9 | 46.3 | 87.5 | 40.9 | 61.4 |

| 10–12 | 31.7 | 0.0 | 34.2 | 5.1 |

| 13–15 | 22.0 | 12.5 | 24.9 | 33.5 |

| Educational attainment of household head | ||||

| No formal education | 6.9 | 4.2 | 11.5 | 15.1 |

| Elementary school | 43.9 | 41.7 | 49.7 | 53.3 |

| Junior high school | 34.2 | 41.7 | 26.0 | 23.8 |

| High school | 13.8 | 12.5 | 11.9 | 7.1 |

| Some college+ | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Place of origin | ||||

| City | 10.6 | 8.3 | 11.0 | 6.5 |

| Town | 19.9 | 16.7 | 7.8 | 5.8 |

| Rural | 69.5 | 75.0 | 81.2 | 87.6 |

| Number of children ages 6–15 in household | ||||

| 1 | 23.6 | 41.7 | 23.7 | 34.1 |

| 2 | 38.6 | 20.8 | 42.5 | 34.6 |

| 3 | 27.2 | 20.8 | 23.4 | 20.4 |

| 4+ | 10.6 | 16.7 | 10.4 | 11.0 |

| Housing area (sq-meter) | ||||

| Up to 50 | 20.3 | 20.8 | 27.1 | 32.0 |

| 50–100 | 33.7 | 54.2 | 34.7 | 36.3 |

| 100–150 | 21.5 | 8.3 | 18.0 | 15.4 |

| 150+ | 24.4 | 16.7 | 20.2 | 16.3 |

| Number of rooms in house | ||||

| 1 | 9.8 | 25.0 | 17.3 | 22.8 |

| 2 | 33.3 | 41.7 | 30.5 | 31.7 |

| 3 | 15.4 | 8.3 | 16.1 | 15.6 |

| 4 | 15.4 | 16.7 | 16.1 | 14.1 |

| 5+ | 26.0 | 8.3 | 20.1 | 15.8 |

| Number of observations | 246 | 24 | 34,432 | 6,075 |

Source: The 1995 China 1% Population Sample Survey

The two descriptive tables are paired. Table 1 mainly shows vertical distributions (column percentages) by enrollment status and the existence of emigrants in a household for each variable listed. For example, there were 270 children of emigrants; 246 of whom were enrolled, with 52 percent of the boys vs. 48 percent of the girls. However, Table 1 does not display what proportion of boys from emigrant households was actually enrolled among all the boys from emigrant households. Of the 24 children not enrolled, approximately 54 percent were boys and 46 percent were girls. While Table 1 only shows the distribution of boys and girls of emigrants within “enrolled” versus “not enrolled” groups, Table 2 emphasizes the proportions within each variable category and enables us to make a comparison of school enrollment status between boys and girls from emigrant households. Also, a comparison of school enrollment status between the boys and girls from emigrant and non-emigrant households can be observed. Of 270 children of emigrants, 90.8 percent of the boys and 91.5 percent of the girls were reported enrolled. Overall, 91.1 percent of the children from emigrant households were enrolled in school, whereas 8.9 percent of the children from emigrant households were not. Comparing the percentages in Table 2, higher school enrollment rates are observed among children of emigrants than among those of non-emigrants in almost all the categories, including gender, age, educational background of the head of household, and some wealth indicators. The age groups of children not enrolled in school seem bipolarized into younger and older groups for emigrant children, though the youngest age group shows the larger percentage. This could imply an age delay in school enrollment among the younger children of emigrants.

TABLE 2.

Socio-Demographic Profiles of Children from Households with and without Emigrants in Fujian Province by School Enrollment Status, 1995 (Row Percentages)

| Variables | Children of emigrants |

Children of non-emigrants |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled (%) | Not enrolled (%) | Enrolled (%) | Not enrolled (%) | |

| Total | 91.1 | 8.9 | 85.0 | 15.0 |

| Gender | ||||

| Boy | 90.8 | 9.2 | 87.6 | 12.4 |

| Girl | 91.5 | 8.5 | 82.3 | 17.7 |

| Age | ||||

| 6–9 | 84.4 | 15.6 | 79.1 | 20.9 |

| 10–12 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 97.4 | 2.6 |

| 13–15 | 94.7 | 5.3 | 80.8 | 19.2 |

| Educational attainment of household head | ||||

| No formal education | 94.4 | 5.6 | 81.1 | 18.9 |

| Elementary school | 91.5 | 8.5 | 84.1 | 15.9 |

| Junior high school | 89.4 | 10.6 | 86.1 | 13.9 |

| High school | 91.9 | 8.1 | 90.4 | 9.6 |

| Some college+ | 100.0 | 0.0 | 88.6 | 11.5 |

| Place of origin | ||||

| City | 92.9 | 7.1 | 90.5 | 9.5 |

| Town | 92.5 | 7.6 | 88.4 | 11.6 |

| Rural | 90.5 | 9.5 | 84.0 | 16.0 |

| Number of children ages 6–15 in household | ||||

| 1 | 85.3 | 14.7 | 79.8 | 20.3 |

| 2 | 95.0 | 5.0 | 87.5 | 12.5 |

| 3 | 93.1 | 6.9 | 86.7 | 13.3 |

| 4+ | 86.7 | 13.3 | 84.3 | 15.7 |

| Housing area (sq-meter) | ||||

| Up to 50 | 90.9 | 9.1 | 82.9 | 17.1 |

| 50–100 | 86.5 | 13.5 | 84.5 | 15.5 |

| 100–150 | 96.4 | 3.6 | 87.0 | 13.0 |

| 150+ | 93.8 | 6.3 | 87.6 | 12.4 |

| Number of rooms in house | ||||

| 1 | 80.0 | 20.0 | 81.2 | 18.8 |

| 2 | 89.1 | 10.9 | 84.6 | 15.4 |

| 3 | 95.0 | 5.0 | 85.5 | 14.5 |

| 4 | 90.5 | 9.5 | 86.7 | 13.3 |

| 5+ | 97.0 | 3.0 | 87.9 | 12.1 |

| Number of observations | 246 | 24 | 34,432 | 6,075 |

Source: The 1995 China 1% Population Sample Survey

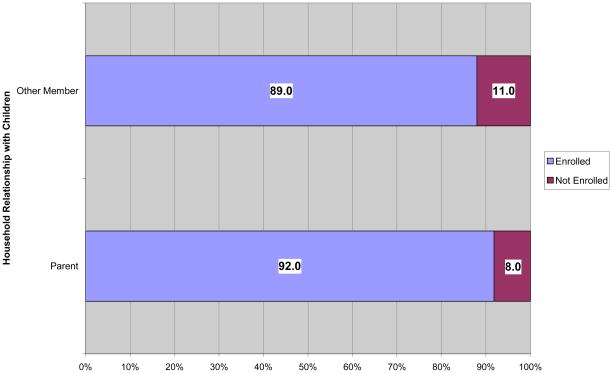

Not surprisingly, in the majority of the cases, it is the father who went abroad. As we examined the household relationship for children from households with emigrants, among the 246 children who were enrolled in school, about 70 percent of the households had either one or both parents residing abroad. Additionally, about 62 percent reportedly lived apart from their fathers who had emigrated. The enrollment rate for children whose fathers lived abroad at the time that the survey was taken was slightly higher (92%) than children whose non-parent family member lived abroad (89%), as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

A Comparison of School Enrollment Status by Household Relationship between Children and Emigrants

In Table 4, there are four logistic regression models shown. Recall our dependent variable is whether or not a child is enrolled in school at time of the survey. Model 1 is the simplest model and incorporated to calculate the probabilities of school enrollment based on only gender and the household relationship between children and emigrants. Model 2 includes the various basic socio-demographic variables with a place of origin. Along with all the variables in Model 2, Model 3 includes the interaction terms between gender and emigrant’s household relationship with a child so as to measure the effect of the gender differential in school enrollment, particularly among the children of emigrants. As the effect in our model is not statistically significant, the difference in school enrollment between boys and girls appears to be alleviated when parents or household members reside abroad. Then in Model 4, we add the two wealth indicator variables to Model 2, including the total housing area measured in square meters and the number of rooms in a house, and controlling for the number of children in a household between the ages of 6 and 15 years. Based on the outcomes from the logistic regression models in Table 4, we found a negative association with school enrollment among girls and a positive association in all of the other explanatory variables, such as child’s age, emigrant’s household relationship with a child, household head’s educational attainment level, place of origin, the number of children in a household aged 6 to 15, the housing area, and the number of rooms in a house.

TABLE 4.

Logistic Regression of School Enrollment for Children in Fujian Province, China, 1995

| Variables | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Girl | −0.42*** | 0.03 | −0.42*** | 0.03 | −0.42*** | 0.03 | −0.39*** | 0.03 |

| Boy (Reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Age | 0.16*** | 0.01 | 0.16*** | 0.01 | 0.17*** | 0.01 | ||

| Household relationship of emigrant | ||||||||

| Parent | 0.70** | 0.27 | 0.64* | 0.27 | 0.39* | 0.35 | 0.63* | 0.27 |

| Other family member | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.36 |

| Non-emigrant HH (Reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Household head educational attainment | ||||||||

| No formal education (Reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Elementary school | 0.20*** | 0.04 | 0.20*** | 0.04 | 0.18*** | 0.05 | ||

| Junior high school | 0.41*** | 0.05 | 0.41*** | 0.05 | 0.38*** | 0.05 | ||

| High school+ | 0.77*** | 0.06 | 0.77*** | 0.06 | 0.75*** | 0.07 | ||

| Place of origin | ||||||||

| City | 0.49*** | 0.06 | 0.49*** | 0.06 | 0.68*** | 0.06 | ||

| Town | 0.32*** | 0.06 | 0.32*** | 0.06 | 0.41*** | 0.06 | ||

| Rural (Reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Interaction term | ||||||||

| Gender × Parent | 0.55 | 0.55 | ||||||

| Gender × Other family member | 0.53 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Number of children ages 6–15 in household | 0.44*** | 0.04 | ||||||

| Housing area (Logged) | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Number of rooms in house (Logged) | 0.15*** | 0.04 | ||||||

| Constant | 1.95*** | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.68*** | 0.14 |

| Pseudo R-square | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | ||||

| Number of observations | 40,777 | 40,777 | 40,777 | 32,897 | ||||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

There is a high likelihood that school enrollment increases as the total number of rooms in a house. Likewise, a similar trend is implied when considering the total housing area. As the increasing number of children in households is also positively associated with school enrollment, it can be inferred that any competition among siblings of school enrollment is non-existent. Focusing on the school enrollment status of children of emigrants predicted based on Model 4 in Table 4, the results confirm our hypothesis that household wealth significantly accounts for school enrollment for the children of emigrants, although we could not ascertain a statistical significance in terms of the total housing area.

The most important finding from Table 4 is that children from households with at least one emigrant parent are more likely to be enrolled in school. To ease interpretation and give a better sense of the magnitude of the differences in school enrollment, we generated predicted probabilities of school enrollment using the result from Table 4 (Model 4). For predictors other than gender and place of origin, we assume that an individual possesses a socio-demographic background of a typical resident of Fujian Province. In other words, we substitute the mean values for the continuous variables such as age, the number of children in a household, the housing area, and the number of rooms in a house and the mode for such nominal variables as educational attainment level of the head of household.

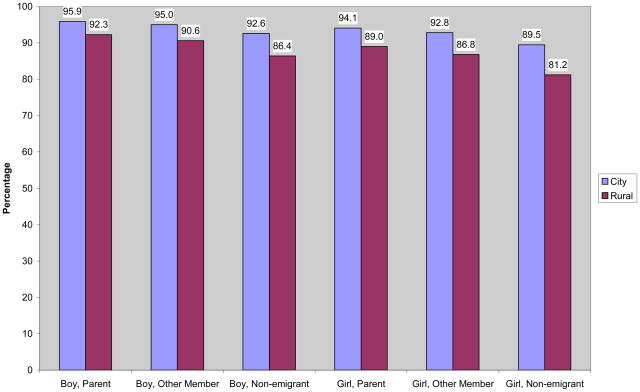

The results suggest that the children of emigrants are better off than their non-emigrant counterparts. The predicted school enrollment percentages for children of emigrants with one or both parents living abroad, children of emigrants whose non-parental family member lives abroad, and children of non-emigrants are [95.9% and 95.0% vs. 92.6%, respectively] for boys living in cities and [92.3% and 90.6% vs. 86.4%] for boys living in rural areas as well as [94.1% and 92.8% vs. 89.5%] for girls in cities and [89.0% and 86.8% vs. 81.2%] for girls in rural areas. In short, the differences in predicted enrollment scores between children from emigrant households and non-emigrant households show 3.3 percent for city boys, 5.9 percent for rural boys, 4.6 percent for city girls, and 7.8 percent for rural girls. The improvement in school enrollment for rural girls is the most striking.

As might have been expected, children residing in cities consistently demonstrate a higher likelihood of school enrollment when compared to those living in rural areas. The differences in predicted scores between urban and rural children exist for both genders within emigrant and non-emigrant groups. The discrepancies between city and rural areas are remarkable. In terms of gender differences, boys generally exhibit a higher likelihood of being enrolled in school than girls. In fact, when we compared boys and girls in cities whose parents lived abroad, we found that boys tended to enjoy a slightly higher probability of enrollment.

The results also suggest that girls of emigrant households seem to be as likely enrolled in school as boys of emigrants based on our findings from Model 4 in Table 4. In contrast, notable gender differences exist among children of non-emigrants in school enrollment, whereby girls living in rural areas suffer the most serious consequences. Our results are consistent with studies conducted by researchers in the past, which examined the educational discrepancies between genders in China. The previous studies documented that the girls have lower educational participation rate than boys, and that children in rural area are less likely to be enrolled in school (Hannum and Xie, 1994; Hannum, 1999; Lavely et al., 1990). However, our results indicate that emigrant children, both boys and girls, excel in predicted school enrollment percentages compared to non-emigrant children. Even the supposedly oppressed group, girls living in rural areas, shows a similar outcome of predicted enrollment percentages when contrasted to boys of non-emigrants living in cities.

Moreover, consistent with earlier studies, rural children of both genders are at a definite disadvantage in terms of school enrollment when compared to children from urban areas. This difference in degree becomes even more apparent as we prepare the predicted scores of school enrollment for children from non-emigrant households in rural areas. The likelihood of rural girls from non-emigrant households being enrolled in school is dramatically lower, in fact the lowest among all twelve groups considered, than that of rural boys from similar households, a difference of 5.2 percent. Simultaneously, a rather undisputed disparity of 12.9 percent emerges between city girls whose parents have emigrated and rural girls from non-emigrants households. The educational attainment level of the head of non-emigrant households living in rural areas is lower than that of city residents (Liang, 2001). Particularly applicable to residents in rural areas, education for children can sometimes be considered an unaffordable item. Even though school enrollment is mandatory within the period of compulsory education, it is in reality that certain additional fees are imposed for textbooks, school supplies, and so on. As we recall the profile of the heads of household in Fujian in Table 1, it shows that a high proportion of those household heads seem to possess somewhat low level of educational attainment. It has been convincingly demonstrated that the educational attainment of a male parent plays a major role for girls. For example, daughters of peasants with low educational attainment experience substantial educational gender inequality (Bauer et al., 1992; Broaded and Liu, 1996; Curran et al., 2004; Haveman et al., 1991). In some cases, even urban residents would rather provide more educational opportunities and expenses to sons than to daughters if they had children of both genders (Tsui and Rich, 2002).

Although we initially expected to see higher enrollment rates for children from households with fewer children as argued in previous studies (Blake, 1981; Knodel et al., 1990), we were surprised to see that the higher number of children in a household contributes considerably to increasing the likelihood of school enrollment for children in this context. Our speculation is that since China’s One-Child Policy was still in place in the mid-1990s in Fujian, individuals who have more than one child tend to have more resources that can be used to pay for things such as the fines for violation of the policy or good connections with local cadres, both of which help to keep their children enrolled in school.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we made innovative use of a unique source of data to examine the impact of international migration on education of children who are left behind in their place of origin. We highlight the key findings here. The results from our analysis suggest that international migration is associated with positive outcomes for education of children who are left behind. Our results also suggest that children from households with emigrants are more likely to be enrolled in school than children from non-emigrant households. Moreover, in terms of children of emigrants, those who reside in urban areas are more likely to remain enrolled in school than those in rural areas. It is also evident that household wealth reinforces the likelihood of educational well-being among all children, including those of emigrants. To the extent that our research portrait a positive influence of international migration on migrant-sending communities, we join other scholars in documenting the positive role of international migration in improving the chance of survivals of infants, releasing the financial constraints of the households, and building and maintaining community infrastructure.

The paper also leaves us with a sense of optimism in terms of reducing the gender gap in education in rural China, a finding that has been well documented by others. Gender and migration issues are a strategic research direction that has caught the attention of an increasingly large number of scholars. As Portes (1999:31) argued recently focusing on gender “can yield novel insights into many phenomena.” Looking at this issue from the perspective of migrants, both men and women, who work in destination societies, there is some evidence that women gain more of equality by migration (Pessar, 1999). Our research suggests that a more equalized gender relationship may be translated into the next generation due to migration of the parents, i.e. increased attention to the education of girls.

One caveat is also in order. Due to the limitations of the survey data, our paper examined only one measure of educational outcome: school enrollment. Admittedly, this is one of many measures of children’s educational outcome. It is possible that the left behind children attend school but are not doing well in school. Our fieldwork in selected schools in Fujian Province suggests that some children of emigrants are not paying enough attention to school work because they perceive that their future is ready to be in the United States with their parents. Others may be motivated to learn but suffer from a lack of support and supervision. Future research should consider other aspects of these children’s educational experience by considering other factors such as school transcripts, interviews with teachers and peer students, and measures of psychological development.

Finally, we want to underscore our methodological innovation of examining educational well-being of children of emigrants who have been left behind by using data collected in migrant-sending communities. With some modification, the methodology can be replicated in to other migration-sending communities as well. In addition, there has been a boom of studies of second generation immigrants. These studies, for the most part, rely on data collected in the United States and often do not consider educational characteristics of children prior to immigration. We see that our research complements this line of research through the lens of educational experience prior to immigration. This ultimately gives a more complete picture of migrant children’s educational experience.

FIGURE 2.

Predicted Percentages of School Enrollment by Gender and Emigrant Status of Household Relationship with Children by Place of Origin

MAP 1.

Location of Fujian Province in China

TABLE 3.

A Household Relationship of Emigrant with Children by School Enrollment Status

| Emigrant in a household | Children of emigrants |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled |

Not enrolled |

Total |

||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Father | 152 | 61.8 | 14 | 58.3 | 166 | 61.5 |

| Mother | 15 | 6.1 | 1 | 4.2 | 16 | 5.9 |

| Both parents | 6 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 2.2 |

| Other family member | 73 | 29.7 | 9 | 37.5 | 82 | 30.4 |

| Number of observations | 246 | 100.0 | 24 | 100.0 | 270 | 100.0 |

Footnotes

We were initially concerned that standard errors of estimates could be biased if we used two or more children present in the same households. To avoid any possible selection bias that could occur, we randomly selected only one child from each household so that we would properly capture characteristics and determinants of children’s school enrollment status at household level. However, the results from statistical analysis did not differ significantly from what we present in this paper. Details are available from the authors upon request.

Contributor Information

Hideki Morooka, Email: hmorooka@uncfsu.edu, Department of Sociology, Fayetteville State University, 1200 Murchison Road, Fayetteville, NC 28301.

Zai Liang, Email: zliang@albany.edu, Department of Sociology, University at Albany, State University of New York, 1400 Washington Ave. Albany, NY 12222.

References

- Astone Nan Marie, McLanahan Sara S. Family Structure, Parental Practices and High School Completion. American Sociological Review. 1991;56(2):309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Astone Nan Marie, McLanahan Sara S. Family Structure, Residential Mobility, and School Dropout: A Research Note. Demography. 1994;31(4):575–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer John, et al. Gender Inequality in Urban China: Education and Employment. Modern China. 1992;18(3):333–370. [Google Scholar]

- Blake Judith. Family Size and the Quality of Children. Demography. 1981;18(4):421–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broaded C Montgomery, Liu Chongshun. Family Background, Gender, and Educational Attainment in Urban China. The China Quarterly. 1996;145:53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrutti Marcela, Massey Douglas S. On the Auspices of Female Migration from Mexico to the United States. Demography. 2001;38(2):187–200. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China Population Sample Survey Office. Tabulations of China 1995 1% Population Sample Survey. Beijing: China Statistical Publishing House; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S94–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Croll Elisabeth J, Ping Huang. Migration for and against Agriculture in Eight Chinese Villages. The China Quarterly. 1997;149:128–146. [Google Scholar]

- Curran Sara R, et al. Boys and Girls’ Changing Educational Opportunities in Thailand: The Effects of Siblings, Migration, and Village Remoteness. In: Baker D, Fuller B, Hannum E, Werum R, editors. Inequality Across Societies: Families, Schools and Persisting Stratification. Vol. 14. Oxford UK: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 59–102. Research in Sociology of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson Deborah A. Family Structure and Children’s Health and Well-Being: Data from the 1988 National Health Interview Survey on Child Health. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53(3):573–584. [Google Scholar]

- Durand Jorge, Parrado Emilio A, Massey Douglas S. Migradollars and Development: A Reconsideration of the Mexican Case. International Migration Review. 1996;30(2):423–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen John, MacMillan Ross, Wheaton Blair. New Kid in Town: Social Capital and The Life Course Effects of Family Migration on Children. American Sociological Review. 1996;61(3):368–385. [Google Scholar]

- Hannum Emily, Xie Yu. Trends in Educational Gender Inequality in China, 1949–1985. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 1994;13:73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hannum Emily. Political Change and the Urban-Rural Gap in Basic Education in China, 1949–1990. Comparative Education Review. 1999;43(2):193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Haveman Robert, Wolfe Barbara, Spaulding James. Childhood Events and Circumstances Influencing High School Completion. Demography. 1991;28(1):133–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes Steven A. Ring is Cracked in Smuggling of Illegal Chinese Immigrants: Route Ran Through Indian Land in New York. The New York Times. 1998 December 11; Metro Section. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson Jan O, Gahler Michael. Family Dissolution, Family Reconstitution, and Children’s Educational Careers: Recent Evidence for Sweden. Demography. 1997;34(2):277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaiaupuni Shawn Malia, Donato Katharine M. Migradollars and Mortality: The Effects of Migration on Infant Survival in Mexico. Demography. 1999;36(3):339–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel William, Kao Grace. Shifting Orientations: How U.S. Labor Migration Affects Children’s aspirations in Mexican Migrant Communities. Social Science Quarterly. 2000;81(1):16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel William, Kao Grace. The Impact of Temporary Labor Migration on Mexican Children’s Educational Aspiration and Performance. International Migration Review. 2001;35(1):205–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel William, Massey Douglas S. The Culture of Mexican Migration: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Social Forces. 2002;80(3):981–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Knodel John, Havanon Napaporn, Sittitrai Werasit. Family Size and the Education of Children in the Context of Rapid Fertility Decline. Population and Development Review. 1990;16(1):31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Krein Sheila Fitzgerald, Beller Andrea H. Educational Attainment of Children From Single-Parent Families: Differences by Exposure, Gender, and Race. Demography. 1988;25(2):221–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavely William, et al. The Rise in Female Education in China: National and Regional Patterns. The China Quarterly. 1990;121:61–93. [Google Scholar]

- Liang Zai. Demography of Illicit Emigration From China: A Sending Country’s Perspective. Sociological Forum. 2001;16(4):677–701. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. International Migration and Economic Development in Comparative Perspective. Population and Development Review. 1988;14(3):383–414. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy Rachel. Migration and Inter-Household Inequality: Observations from Wanzai County, Jiangxi. The China Quarterly. 2000;164:965–982. [Google Scholar]

- Pessar Patricia R. The Role of Gender, Households, and Social Networks in the Migration Process: A Review and Appraisal. In: Hirschman Charles, Kasinitz Philip, DeWind Josh., editors. The Handbook of International Migration: The American Experience. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Republic of China (PRC) The Law of Compulsory Education of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: Law Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pong Suet-Ling. School Participation of Children from Single-Mother Families in Malaysia. Comparative Education Review. 1996;40(3):231–249. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro. Immigration Theory for a New Century: Some Problems and Opportunities. In: Hirschman Charles, Kasinitz Philip, DeWind Josh., editors. The Handbook of International Migration: The American Experience. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Russell Sharon Stanton. Remittances from International Migration: A Review in Perspective. World Development. 1986;14(6):677–696. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts Kenneth. Female Labor Migrants to Shanghai: Temporary ‘Floaters’ or Potential Settlers? International Migration Review. 2002;36(2):492–519. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J Edward, et al. International Migration and Community Development. Population Index. 1996;62(3):397–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Elizabeth, Hanson Thomas, McLanahan Sara. Family Structure and Child Wellbeing: Economic Resources vs. Parental Behaviors. Social Forces. 1994;73(1):221–243. doi: 10.1093/sf/sos119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui Ming, Rich Lynne. The Only Child and Educational Opportunity for Girls in Urban China. Gender and Society. 2002;16(1):74–92. [Google Scholar]