Abstract

Endocytosis of nutrient transporters is stimulated under various conditions, such as elevated nutrient availability. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, endocytosis is triggered by ubiquitination of transporters catalyzed by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Rsp5. However, how the ubiquitination is accelerated under certain conditions remains obscure. Here we demonstrate that closely related proteins Aly2/Art3 and Aly1/Art6, which are poorly characterized members of the arrestin-like protein family, mediate endocytosis of the aspartic acid/glutamic acid transporter Dip5. In aly2Δ cells, Dip5 is stabilized at the plasma membrane and is not endocytosed efficiently. Efficient ubiquitination of Dip5 is dependent on Aly2. aly1Δ cells also show deficiency in Dip5 endocytosis, although less remarkably than aly2Δ cells. Aly2 physically interacts in vivo with Rsp5 at its PY motif and also with Dip5, thus serving as an adaptor linking Rsp5 with Dip5 to achieve Dip5 ubiquitination. Importantly, the interaction between Aly2 and Dip5 is accelerated in response to elevated aspartic acid availability. This result indicates that the regulation of Dip5 endocytosis is accomplished by dynamic recruitment of Rsp5 via Aly2.

The amount of nutrient transporters at the cell surface is tightly regulated in response to environmental cues in order to maintain cellular homeostasis. One way to reduce transporters from the plasma membrane (PM) is via endocytosis. For instance, some of the amino acid transporters are endocytosed from PM to be downregulated when the availability of ambient nutrients changes (12, 17, 20).

Prior to being endocytosed, transporters are subjected to ubiquitination, which acts as an endocytosis signal (3, 18, 20). In yeast, ubiquitination of proteins at PM is generally catalyzed by Rsp5, a HECT-type E3 ubiquitin ligase (6). Rsp5 possesses three WW domains, which recognize PY motifs (PXY or PPXY) in the substrates and thereby ubiquitinates them (3, 8, 21). However, most of the nutrient transporters lack PY motifs, indicating the presence of some adaptors that mediate interaction between Rsp5 and transporters. Only recently, several members in the family of arrestin-like proteins were shown to play such a role in recruiting Rsp5 to substrate transporters and to regulate their endocytosis (12, 16, 17). Proteins of this family, which are also referred to ARTs for arrestin-related trafficking adaptors, contain an arrestin domain and PY motifs in common. Consistent with the presence of PY motifs in these proteins, most of the members have already been reported to bind to Rsp5 and to be ubiquitinated in vitro (4, 10). On the other hand, the arrestin domain might be involved in the association with transporters, similarly to β-arrestin in mammals. β-Arrestin binds to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) upon their ligand binding and facilitates their endocytosis via several mechanisms such as mediating ubiquitination or promoting interaction with endocytic machineries to downregulate the receptors (11, 14). However, in yeast, the precise mechanism by which ubiquitination and endocytosis of transporters are accelerated in response to a variety of stimuli remains largely unknown.

There are 10 members of the arrestin-like protein family in yeast. To date, five members (Ldb19/Art1, Ecm21/Art2, Csr2/Art8, Rod1/Art4, and Art5) have been associated with endocytosis of transporters, although only a few of them are characterized in detail (12, 16, 17). Each member targets distinct transporters, while some target transporters are shared among more than one member. The characterization of each arrestin-like protein, especially the identification of their target transporters, will be necessary to clarify unified regulatory modes dictated through these proteins.

In this report, we demonstrate that one of the yet-uncharacterized arrestin-like proteins, Aly2/Art3, serves as an Rsp5 adaptor to mediate endocytosis of the aspartic acid/glutamic acid transporter Dip5. The closest relative of Aly2, Aly1/Art6, is also shown to participate in Dip5 endocytosis. More importantly, we found that the interaction between Aly2 and Dip5 is accelerated, concomitant with the promotion of Dip5 ubiquitination, when the availability of ambient aspartic acid increases. This result reveals that dynamic regulation of Dip5 endocytosis is achieved by its substrate-dependent interaction with Aly2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study, all derived from S288C, are listed in Table 1. Deletion mutants and tagged strains were constructed by standard methods (9, 13). To generate the aly2ΔC-PY mutant, a PCR-mediated mutagenesis method was performed. Plasmids used in this study are pRS413 (CEN HIS3) (23), pRS415 (CEN LEU2) (23), pRS416 (CEN URA3) (23), pRS425 (2μm LEU2) (2), pRK145 (CEN URA3 TRP1) (this study), pMK116 (2μm LEU2 PGPD-GST-ALY2) (this study), pMK131 (CEN TRP1 PADH-GST-ALY2) (this study), pMK139 (CEN TRP1 PADH-GST-aly2ΔC-PY) (this study), pHY22 (2μm URA3 PGPD-myc-RSP5) (kindly provided by Tomoko Andoh) (26), pRK219 (CEN URA3 PGPD-DIP5-EGFP) (this study), pRK220 [CEN URA3 PGPD-DIP5(6S2T-A)-EGFP] (this study), and pRK221 [CEN URA3 PGPD-DIP5(6S2T-D)-EGFP] (this study). For all experiments except for those shown in Fig. 2A and D, cells were grown to mid-log phase in synthetic dextrose (SD) medium supplemented with amino acids and nucleotide bases required for growth. For Fig. 2A, 50 μg/ml l-aspartic acid or 50 μg/ml l-glutamic acid was added as a sole nitrogen source to ammonium-free YNB glucose medium. For Fig. 2D, ammonium sulfate in SD medium was replaced with 2 mg/ml urea. The nutrient supplement used in Fig. 1 consists of 40 μg/ml adenine, 20 μg/ml l-arginine, 100 μg/ml l-aspartic acid, 100 μg/ml l-glutamic acid, 30 μg/ml l-lysine, 20 μg/ml l-methionine, 50 μg/ml l-phenylalanine, 375 μg/ml l-serine, 200 μg/ml l-threonine, 40 μg/ml l-tryptophan, 30 μg/ml l-tyrosine, and 150 μg/ml l-valine (final concentrations).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| TM141 | MATaura3-52 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 | Lab stock |

| MK191 | TM141 aly2::kanMX | This study |

| MK563 | TM141 can1::kanMX | This study |

| RK902 | TM141 ldb19::hphNT1 | This study |

| RK904 | TM141 ldb19::hphNT1 aly2::kanMX | This study |

| RK349 | TM141 CAN1-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK356 | TM141 aly2::kanMX CAN1-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK907 | TM141 ldb19::hphNT1 CAN1-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK910 | TM141 ldb19::hphNT1 aly2::kanMX CAN1-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK724 | TM141 dip5::kanMX CAN1-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK807 | TM141 gap1::HIS3 | This study |

| RK811 | TM141 gap1::HIS3 dip5::kanMX | This study |

| RK809 | TM141 gap1::HIS3 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK821 | TM141 gap1::HIS3 DIP5-3HA::TRP1 | This study |

| RK592 | TM141 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK599 | TM141 aly2::kanMX DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK694 | TM141 sla1::hphNT1 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK703 | TM141 end3::hphNT1 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK899 | TM141 kanMX::PGPD-ALY2-13myc::HIS3 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK733 | TM141 ALY2-13myc::HIS3 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK913 | TM141 aly2::HIS3 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK598 | TM141 aly1::HIS3 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK601 | TM141 aly2::kanMX aly1::HIS3 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK595 | TM141 rsp5-1 DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| RK637 | TM141 DIP5-3HA::TRP1 | This study |

| RK639 | TM141 rsp5-1 DIP5-3HA::TRP1 | This study |

| RK789 | TM141 aly2::kanMX DIP5-3HA::TRP1 | This study |

| RK835 | TM141 aly2ΔC-PY DIP5-EGFP::TRP1 | This study |

| MK350 | TM141 ALY2-13myc::HIS3 | This study |

| RK768 | TM141 rsp5-1 ALY2-13myc::HIS3 | This study |

| RK633 | TM141 ALY2-13myc::HIS3 DIP5-3HA::TRP1 | This study |

| RK722 | TM141 dip5::kanMX | This study |

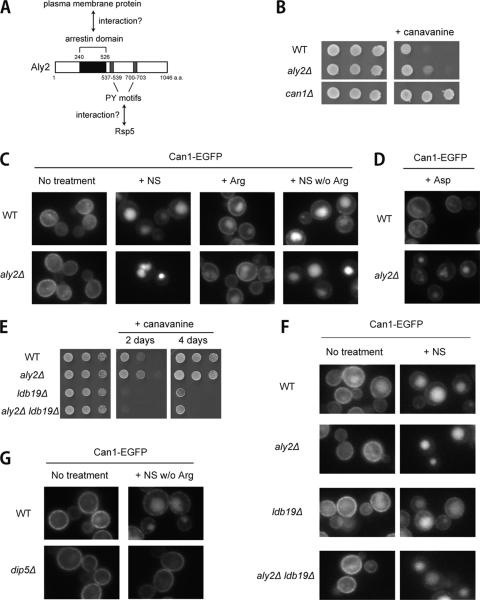

FIG. 1.

Effects of ALY2 gene disruption on Can1 sorting in response to Dip5-mediated amino acid incorporation. (A) Schematic representation of Aly2 protein. (B) Canavanine resistance of aly2Δ cells. TM141 (WT), MK191 (aly2Δ), and MK563 (can1Δ) were grown on SD plates with or without 1 mg/liter canavanine. (C) Effects of ALY2 gene disruption on vacuolar sorting of Can1 in response to changes in nutrient availability. Strains whose endogenous Can1 was fused with EGFP, RK349 (WT) and RK356 (aly2Δ), were treated with the nutrient supplement for SC medium (NS), 20 μg/ml arginine, or NS lacking arginine for 180 min. The localization of Can1-EGFP was examined by fluorescence microscopy. (D) Effects of ALY2 gene disruption on vacuolar sorting of Can1 in response to aspartic acid treatment. RK349 (WT) and RK356 (aly2Δ) were treated with 1 mg/ml aspartic acid for 120 min. (E) Contributions of Aly2 to the canavanine sensitivity of ldb19Δ cells. TM141 (WT), MK191 (aly2Δ), RK902 (ldb19Δ), and RK904 (aly2Δ ldb19Δ) were grown on SD plates with or without 1 mg/liter canavanine. (F) Contributions of Aly2 and Ldb19 to Can1 sorting. Strains whose endogenous Can1 was fused with EGFP, RK349 (WT), RK356 (aly2Δ), RK907 (ldb19Δ), and RK910 (aly2Δ ldb19Δ), were treated with NS for 180 min. (G) Effects of DIP5 gene disruption on vacuolar sorting of Can1 in response to a change in nutrient availability. RK349 (WT) and RK724 (dip5Δ), whose endogenous Can1 was fused with EGFP, were treated or not with NS lacking arginine.

Fluorescence microscopy.

All cell images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (BX51; Olympus). In live-imaging experiments, cells whose Can1 or Dip5 was fused with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in mid-log phase were stimulated with the indicated nutrients and then collected by centrifugation and resuspended in a 10% volume of the same medium. Fluorescence signals of EGFP were detected using a U-MNIBA2 filter (Olympus). In the immunostaining experiment, cells whose Dip5 was tagged with triple-hemagglutinin (HA) epitope in mid-log phase were fixed with formaldehyde and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer and subsequently once with PS buffer (PBS buffer containing 1.2 M sorbitol). Then cells were incubated in PS buffer containing 100 μg/ml Zymolyase and 30 mM β-mercaptoethanol and washed once with PST buffer (PS buffer containing 1% Triton X-100) and then three times with PS buffer. After blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), immunolabeling was performed using anti-HA antibody (12CA5, ascites fluids) and anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes). The fluorescence signals were detected using a U-MNIBA2 filter.

Aspartic acid uptake assay.

Mid-log-phase cells (200 μl) were treated with 28 μg/ml [14C]aspartic acid (0.025 μCi). After 5 min, uptake was stopped by adding 400 μl of 10 mg/ml ice-cold nonradioactive aspartic acid. Then cells were collected on a glass fiber filter (GF/C; Whatman), washed three times with ice-cold water, dried, and counted in a scintillation counter (LSC-5101; Aloka). The specific activity of Dip5 was calculated by subtracting the uptake rates of dip5Δ strains from those of corresponding DIP5 strains. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cell lysate preparation.

For immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting experiments, cell lysates were prepared as follows. Cells treated with trichloroacetic acid (final concentration, 7.2% [vol/vol]) were collected by centrifugation and washed with 70% ethanol. Then cell pellets were suspended in urea buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM EDTA, 6 M urea, 1% SDS, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and disrupted with glass beads. Obtained cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and total protein concentrations were normalized using a DC protein assay (Bio-Rad).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Cell lysates were incubated with Laemmli SDS sample buffer for 30 min at 37°C and then subjected to SDS-PAGE. After transfer and blocking with 1% skim milk, membranes were immunoblotted with the following primary antibodies: anti-GFP (7.1 and 13.1; Roche), anti-PGK (22C5; Molecular Probes), anti-HA (12CA5, ascites fluids), antiubiquitin (P4D1; Cell Signaling), anti-GST (Z-5; Santa Cruz), or anti-myc (9E10, ascites fluids). Then membranes were treated with secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, anti-mouse IgG (NA931; GE Healthcare) or anti-rabbit IgG (NA934; GE Healthcare), and developed with ECL Plus (GE Healthcare).

Immunoprecipitation.

Cell lysates were diluted with a 10× volume of immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 40 μg/ml leupeptin, 40 μg/ml aprotinin, 20 μg/ml pepstatin A) and rotated overnight at 4°C either with anti-myc agarose beads (A7470; Sigma) or with anti-HA antibody (Y-11; Santa Cruz) and protein A-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). After being washed with IP buffer three times, beads were incubated with SDS sample buffer for 30 min at 37°C, and the protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Cross-linking with DSP.

In Aly2-Dip5 interaction assays (see Fig. 6), cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline buffer and concentrated to a 10% volume. After stimulation with aspartic acid, cells were treated with dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) (DSP) (final concentration, 2.5 mM) for 30 min at room temperature and subsequently quenched with Tris-HCl (pH 8.0; final concentration, 20 mM). Cell lysate preparation and immunoprecipitation were performed as described above. To cleave DSP completely, beads were incubated with SDS sample buffer as described above and then additionally incubated with SDS sample buffer including dithiothreitol (final concentration, 50 mM) for 30 min at 37°C.

In vitro phosphatase treatment.

Following immunoprecipitation, beads were washed three times with IP buffer and additionally three times with 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and then incubated with 6.7 U/μl λ-phosphatase (New England Biolabs) in phosphatase buffer (New England Biolabs) for 30 min at 30°C. Beads were incubated with SDS sample buffer for 30 min at 37°C, and the protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE.

RESULTS

Aly2 affects Can1 localization through acting in Dip5-mediated amino acid response.

Aly2 has an arrestin domain and two PY motifs (Fig. 1A) and thus is presumed to serve as an Rsp5 adaptor to mediate endocytosis of target proteins at PM. Amino acid transporters are among the potential targets of Aly2. Therefore, we first investigated sensitivities of an ALY2-disrupted strain toward various toxic amino acid analogs that are transported through corresponding amino acid transporters. Of several compounds tested, aly2Δ cells displayed moderate resistance to canavanine, an arginine analog, compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 1B). Because canavanine is exclusively transported through the arginine transporter Can1, we next examined the localization of EGFP-tagged Can1 (Can1-EGFP) in wild-type and aly2Δ cells. The localizations of Can1 in both cells were similar under the minimal medium (SD) condition; however, they significantly differed upon addition of the nutrient supplement for SC medium consisting of several amino acids and nucleotide bases: some Can1 was retained at PM in wild-type cells, whereas almost all of Can1 was lost from PM in aly2Δ cells (Fig. 1C). Thus, the localization of Can1 appears to be affected by Aly2. The addition of arginine alone at the concentration in the nutrient supplement only slightly induced vacuolar sorting of Can1 in both wild-type and aly2Δ cells, while addition of the nutrient supplement lacking arginine caused different localizations of Can1 between wild-type and aly2Δ cells, similar to results with the complete nutrient supplement (Fig. 1C). Therefore, the excessive vacuolar sorting of Can1 in aly2Δ cells seems to be irrelevant to its own transport activity but indirectly regulated by other nutrients.

We further examined which components of the nutrient supplement could cause the different vacuolar sorting of Can1 between wild-type and aly2Δ cells and found that either aspartic acid or glutamic acid contributes to the excessive sorting of Can1 into the vacuole in aly2Δ cells (Fig. 1D and data not shown).

We then tested the relationship between Aly2, which antagonizes Can1 endocytosis, and Ldb19/Art1, which was reported to mainly mediate Can1 endocytosis (12). As shown in Fig. 1E, the ALY2 gene disruption only marginally suppressed the canavanine sensitivity of ldb19Δ cells (ldb19Δ aly2Δ, 4 days). Conversely, the enhanced vacuolar sorting of Can1 in aly2Δ cells upon the addition of complete nutrient supplement occurred even without Ldb19 (Fig. 1F). The different contributions of two arrestin-like proteins may be attributed to different stimulations to induce endocytosis (see Discussion).

Aspartic acid and glutamic acid are transported through Dip5 (19); thus we next investigated the effect of DIP5 gene disruption on Can1 sorting. In dip5Δ cells, the delivery of Can1 to the vacuole after treatment with the nutrient supplement lacking arginine was remarkably suppressed (Fig. 1G). These results suggest that the vacuolar sorting of Can1 is indirectly triggered by uptakes of aspartic acid and/or glutamic acid through Dip5 and that Aly2 plays a role in regulating the amount and/or activity of Dip5 at PM, where Dip5 transports these amino acids.

Aly2 is required for efficient Dip5 endocytosis.

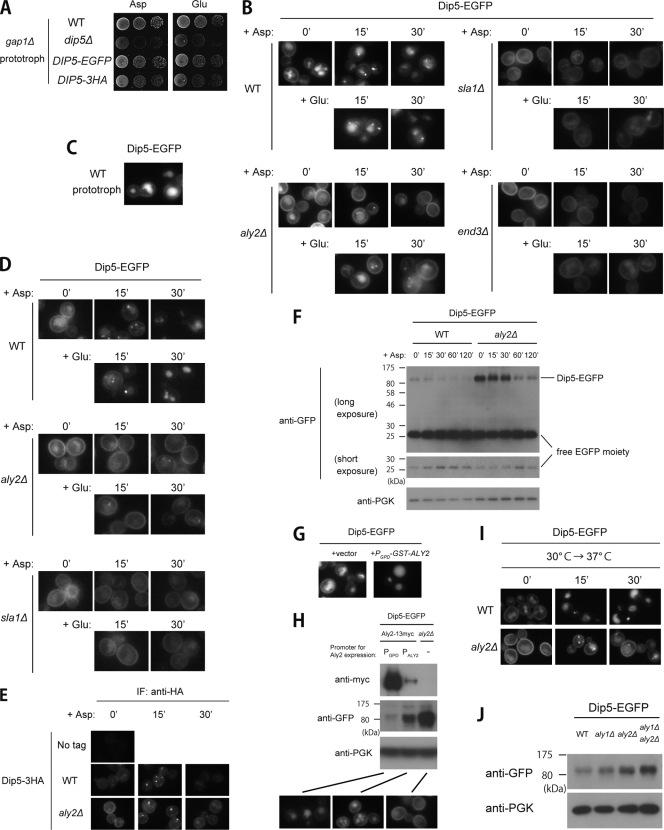

To examine the role of Aly2 in Dip5 localization, we compared the localizations of EGFP-tagged Dip5 (Dip5-EGFP) between wild-type and aly2Δ cells. Dip5-EGFP was functional, as judged by the good growth of the tagged strain on media containing aspartic acid or glutamic acid as a sole nitrogen source (Fig. 2A). Dip5 localized at both PM and the vacuole in wild-type cells (Fig. 2B, WT, 0 min). Similar localization was observed when prototroph cells were grown in the SD medium not containing any supplements (Fig. 2C), and therefore the basal vacuolar trafficking of Dip5 was not due to the existence of nonsubstrate nutrient supplements added to complement auxotrophy of the strains, i.e., uracil, leucine, and histidine. We focused on the levels of the EGFP fluorescence at PM and their change, because EGFP is highly resistant to vacuolar degradation and thus the vacuolar EGFP pool reflects various parameters in addition to the rate of Dip5 endocytosis. Treatment with aspartic acid or glutamic acid caused Dip5 on PM to be sorted initially to dot-like compartments (Fig. 2B, WT, +Asp/+Glu, 15 min) and subsequently to the vacuole (Fig. 2B, WT, +Asp/+Glu, 30 min). The vacuolar localization of Dip5 in the normal growth condition as well as following the addition of aspartic acid/glutamic acid was noticeably prevented in mutants defective in endocytosis (sla1Δ and end3Δ) (Fig. 2B), suggesting that Dip5 is delivered into the vacuole via the regular endocytic pathway.

FIG. 2.

Roles of Aly2 and Aly1 in Dip5 endocytosis. (A) Functionality of two tagged versions of Dip5. Strains whose GAP1 gene was disrupted, RK807 (WT), RK811 (dip5Δ), RK809 (DIP5-EGFP), and RK821 (DIP5-3HA), cotransformed with pRS415 and pRK145, pRS415 and pRK145, pRS415 and pRS416, and pRS415 and pRS416, respectively, were grown on a medium containing aspartic acid or glutamic acid as a sole nitrogen source. (B) Effects of ALY2, SLA1, or END3 gene disruption on vacuolar sorting of Dip5 in a normal growth condition and after aspartic acid/glutamic acid treatment. Strains whose endogenous Dip5 was fused with EGFP, RK592 (WT), RK599 (aly2Δ), RK694 (sla1Δ), and RK703 (end3Δ), were treated with 200 μg/ml aspartic acid or 200 μg/ml glutamic acid for the indicated time periods. The localization of Dip5-EGFP was examined by fluorescence microscopy. (C) Dip5 localization in an amino acid-free medium. RK592 cotransformed with pRS413, pRS415, and pRS416 was grown in SD medium without any nutrient supplements. (D) Effects of ALY2 or SLA1 gene disruption on vacuolar sorting of Dip5 in a urea-containing medium. RK592 (WT), RK599 (aly2Δ), and RK694 (sla1Δ) were treated with 200 μg/ml aspartic acid or 200 μg/ml glutamic acid for the indicated time periods. The localization of Dip5-EGFP was examined by fluorescence microscopy. (E) The localization of Dip5-3HA. TM141 (No tag) and strains whose endogenous Dip5 was fused with 3HA, RK637 (WT) and RK789 (aly2Δ), were treated with 200 μg/ml aspartic acid for the indicated time periods. The localization of Dip5-3HA was examined by immunostaining with anti-HA antibody. (F) Effects of ALY2 gene disruption on vacuolar degradation of Dip5 after aspartic acid treatment. RK592 (WT) and RK599 (aly2Δ) were treated with 200 μg/ml aspartic acid for the indicated time periods. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (G) Effects of ALY2 overexpression on vacuolar sorting of Dip5. RK592 was transformed with pRS425 (vector) or pMK116 (PGPD-GST-ALY2). (H) Effects of ALY2 overexpression on vacuolar sorting and degradation of Dip5. Strains whose endogenous Dip5 was fused with EGFP, RK899 (PGPD-ALY2-13myc), RK733 (PALY2-ALY2-13myc), and RK913 (aly2Δ), were subjected to immunoblotting analysis and fluorescence microscopy. (I) Effects of ALY2 gene disruption on vacuolar sorting of Dip5 in response to heat stress. RK592 (WT) and RK599 (aly2Δ) were grown at 30°C and then shifted to 37°C. (J) Effects of aly2Δ, aly1Δ, or their double gene disruption on the amount of Dip5. Cell lysates from RK592 (WT), RK598 (aly1Δ), RK599 (aly2Δ), and RK601 (aly1Δ aly2Δ), whose endogenous Dip5 was fused with EGFP, were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

Compared with results in wild-type cells, Dip5 accumulated at PM to a greater extent in aly2Δ cells (Fig. 2B). Moreover, Dip5 remained at PM even 30 min after the aspartic acid/glutamic acid treatment (Fig. 2B). The different localization was confirmed by two alternative experiments. First, the localization of Dip5-EGFP was examined under an alternative growth condition, in which urea was used as a nitrogen source instead of ammonium (Fig. 2D). This replacement of the nitrogen source intensified the fluorescence of Dip5-EGFP on PM in the absence of aspartic acid/glutamic acid. Under this growth condition, Dip5 was also rapidly sorted to the vacuole in response to the treatment with aspartic acid or glutamic acid in wild-type cells, whereas it remained at PM in aly2Δ cells (Fig. 2D). Second, Dip5 was alternatively tagged, C terminally, with a triple-HA epitope (Dip5-3HA). Dip5-3HA was functional (Fig. 2A), and its localization was in good agreement with that of Dip5-EGFP (Fig. 2E; note the absence of signal in the vacuole, which differs from the case with Dip5-EGFP and is likely due to the sensitivity of the HA epitope to vacuolar degradation). All these results indicate that Aly2 promotes both constitutive and aspartic acid/glutamic acid-induced Dip5 endocytosis. Consistent with the cellular localization of Dip5 in wild-type cells, the amount of full-length Dip5-EGFP decreased during 30 min after aspartic acid treatment and simultaneously the amount of free EGFP moiety, which is resistant to vacuolar proteases, cleaved from Dip5-EGFP increased as a consequence of the vacuolar degradation of Dip5 (Fig. 2F). On the other hand, Dip5-EGFP was significantly more abundant in aly2Δ cells than in wild-type cells and mostly remained in the full-length form even 30 min after aspartic acid treatment (Fig. 2F). Still, a slight decrease in the full-length Dip5-EGFP signal was observed in this time span, but it seems not to be due to the vacuolar degradation because the amount of free EGFP moiety appeared constant. We reason that this apparent decrease in the full-length signal on the immunoblotting analysis may result from upward extension of the band caused by polyubiquitination, which partially occurs even in aly2Δ cells (Fig. 3C). We note that, however, the vacuolar sorting of Dip5 in response to aspartic acid treatment was not completely eliminated but seemed to occur at a low rate even in aly2Δ cells, as the transition of Dip5-EGFP from the full-length form to the cleaved form started to be observed 60 min after the treatment (Fig. 2F). Nevertheless, the remarkable delay in the Dip5 degradation in aly2Δ cells indicates a crucial role of Aly2 in the endocytic sorting of Dip5.

FIG. 3.

Roles of Rsp5 and Aly2 in Dip5 ubiquitination. (A) Effects of RSP5 temperature-sensitive mutation on vacuolar sorting of Dip5 in a normal growth condition and after aspartic acid treatment. Strains whose endogenous Dip5 was fused with EGFP, RK592 (WT) and RK595 (rsp5-1), were grown at 24°C or 30°C and treated with 200 μg/ml aspartic acid for the indicated time periods. (B) Electrophoretic mobility shifts of Dip5 in response to aspartic acid treatment. Wild-type strain TM141 (−) and a strain whose endogenous Dip5 was fused with 3HA, RK637 (+), were treated with 200 μg/ml aspartic acid for the indicated time periods. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. (C) Effects of Rsp5 and Aly2 impairment on Dip5 ubiquitination in a normal growth condition and after aspartic acid treatment. TM141 (WT −) and strains whose endogenous Dip5 was fused with 3HA, RK637 (WT +), RK639 (rsp5-1), and RK789 (aly2Δ), were treated or not with 200 μg/ml aspartic acid for 5 min. Immunoprecipitated Dip5-3HA from cell lysates was subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

Next, we examined the effect of Aly2 overexpression on Dip5 localization. Dip5 became constitutively sorted to the vacuole when glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Aly2 was expressed using an expression plasmid with the strong GPD promoter (Fig. 2G). A decrease in Dip5 at PM was also confirmed by assaying the Dip5 activity measured by aspartic acid uptake in nanomoles per minute per optical density at 600 nm (OD600), as follows: vector control, 1.04 ± 0.22; GST-Aly2 overexpression, 0.77 ± 0.12. The overexpression of 13myc-tagged Aly2 (Aly2-13myc) using the GPD promoter integrated in the chromosomal ALY2 locus also caused constitutive sorting of Dip5 to the vacuole, and the amount of Dip5 was inversely correlated with that of Aly2-13myc (Fig. 2H). These results further demonstrate a positive role of Aly2 in Dip5 endocytosis.

Aly2 not only is involved in aspartic acid-stimulated Dip5 endocytosis but also has a more general effect on Dip5 endocytosis, because Dip5 endocytosis induced by heat stress was also prevented in aly2Δ cells (Fig. 2I). Collectively, these results suggest that Dip5 is a direct target of Aly2.

There are 10 arrestin-like proteins in yeast. Each arrestin-like protein might either function on specific target proteins or share the same target proteins. Previously, it was reported that different arrestin-like proteins, such as the two closest relatives, target the same transporter (12, 16, 17). Therefore, we examined the effect of gene disruption of ALY1, the closest relative of ALY2, on the amount of Dip5-EGFP. As shown in Fig. 2J, Dip5-EGFP was slightly more abundant in aly1Δ cells, although the increase was less remarkable than in aly2Δ cells. Correspondently, Dip5-EGFP showed slightly increased localization at PM in aly1Δ cells (data not shown). Furthermore, the amount of Dip5-EGFP became even more abundant in aly1Δ aly2Δ double-disrupted cells (Fig. 2J). Therefore, Aly1 might also function in Dip5 endocytosis. On the other hand, each single disruption of any of the other 8 arrestin-like proteins, i.e., Ldb19, Ecm21, Csr2, Rod1, Art5, Rog3, Rim8, or Art10, did not apparently alter the localization pattern of Dip5-EGFP (data not shown). Thus, Dip5 endocytosis seems to be mediated mainly by Aly2 and partially by Aly1.

Rsp5 and Aly2 mediate Dip5 ubiquitination.

To clarify the molecular function of Aly2, we next tried to examine which step in Dip5 endocytosis is mediated by Aly2. Ubiquitination of Dip5 is a possible process in which Aly2 is involved, because PM proteins are known to be ubiquitinated prior to endocytosis (3, 18, 20).

Previous studies have demonstrated that ubiquitination of various PM proteins is catalyzed by the Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase (6). To elucidate whether Rsp5 also mediates Dip5 endocytosis, we investigated the localization of Dip5 in rsp5-1 (a temperature-sensitive mutant of RSP5) cells (25). As in aly2Δ cells, Dip5 excessively accumulated at PM and was not endocytosed efficiently after aspartic acid treatment in rsp5-1 cells grown at 30°C (Fig. 3A). The impairment in Dip5 endocytosis was relieved at a lower temperature (Fig. 3A, 24°C), seemingly in proportion to the activity of Rsp5. Thus, Rsp5 contributes to Dip5 endocytosis.

To estimate Dip5 ubiquitination by an immunoblotting analysis, we used strains expressing Dip5-3HA. As shown in Fig. 3B, Dip5-3HA showed a smeared pattern in the immunoblotting analysis (lane 2). Upon aspartic acid treatment, slow-migrating species of Dip5-3HA were initially observed (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4) and subsequently diminished (Fig. 3B, lane 5). We reasoned that this mobility shift results from ubiquitination prior to endocytosis, and we then investigated the ubiquitination status of Dip5 with an immunoblotting analysis using an antiubiquitin antibody. The smeared antiubiquitin signal, extending from the position corresponding to the major Dip5 signal to a far-higher-molecular-weight region, was detected in Dip5-3HA immunoprecipitates (Fig. 3C, lane 2), suggesting the constitutive polyubiquitination of Dip5 under the normal growth conditions. The ubiquitination was further accelerated by aspartic acid treatment (Fig. 3C, lane 3). In rsp5-1 cells, however, both constitutive and stimulation-accelerated ubiquitination of Dip5 was decreased (Fig. 3C, lanes 4 and 5; note that the total Dip5 was significantly more abundant in rsp5-1 cells than in wild-type cells), indicating that ubiquitination of Dip5 is catalyzed at least in part by Rsp5.

The degrees of ubiquitination of Dip5 in the normal growth condition as well as after stimulation were also remarkably decreased in aly2Δ cells (Fig. 3C, lanes 6 and 7). This result reveals that Aly2 is involved in Dip5 ubiquitination.

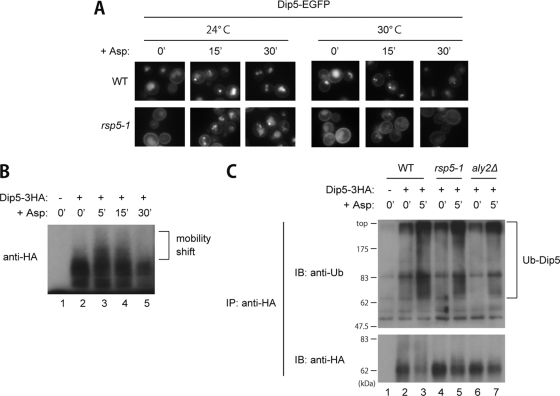

Aly2 functions via the physical interaction with Rsp5.

Similar roles of Rsp5 and Aly2 in ubiquitination and endocytosis of Dip5 suggest that they work cooperatively. The physical interaction between Aly2 and Rsp5 has actually been reported (10, 12). We confirmed the interaction. Both GST-tagged Aly2 (GST-Aly2) and myc epitope-tagged Rsp5 (myc-Rsp5) were coexpressed in wild-type cells and subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-myc antibody. As shown in Fig. 4A, GST-Aly2 was coprecipitated with myc-Rsp5, indicating their physical interaction in vivo. There are two PY motifs, which are possible binding sites with Rsp5 (21), in Aly2 (Fig. 1A). Thus, we used a GST-Aly2 mutant (GST-Aly2ΔC-PY), in which four residues constituting the C-terminal PY motif (PPSY) are replaced with alanine residues, for a coprecipitation experiment and found that GST-Aly2ΔC-PY lost the ability to interact with myc-Rsp5 (Fig. 4A), suggesting that this motif serves as a binding site. We were not able to evaluate the contribution of the N-terminal PY motif for the interaction with Rsp5, because of poor expression of GST-Aly2 with mutations in the N-terminal motif (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Requirement of the interaction with Rsp5 for the Aly2 function. (A) Physical interaction between Aly2 and Rsp5 via an Aly2 PY motif. Wild-type strain TM141 was cotransformed with pMK131 (PADH-GST-ALY2) and pRS416 (vector) (WT −), pMK131 and pHY22 (PGPD-myc-RSP5) (WT +), or pMK139 (PADH-GST-aly2ΔC-PY) and pHY22 (ΔC-PY +). myc-Rsp5 immunoprecipitates from cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) Effects of Aly2 PY motif disruption on vacuolar sorting of Dip5. The localization of Dip5-EGFP in strains whose endogenous Dip5 was fused with EGFP, RK592 (WT), RK599 (aly2Δ), and RK835 (aly2ΔC-PY), was examined by fluorescence microscopy.

As in aly2Δ cells, Dip5-EGFP excessively accumulated at PM in aly2ΔC-PY cells (Fig. 4B). Different degrees of Dip5 accumulation between wild-type, aly2Δ, and aly2ΔC-PY cells were also confirmed by measuring the Dip5 activity (nmol/min/OD600), as follows: wild-type cells, 1.01 ± 0.15; aly2Δ cells, 1.34 ± 0.07; aly2ΔC-PY cells, 1.50 ± 0.20. These results indicate that the physical interaction with Rsp5 is necessary for Aly2 to function in Dip5 endocytosis.

Aly2 is ubiquitinated by Rsp5.

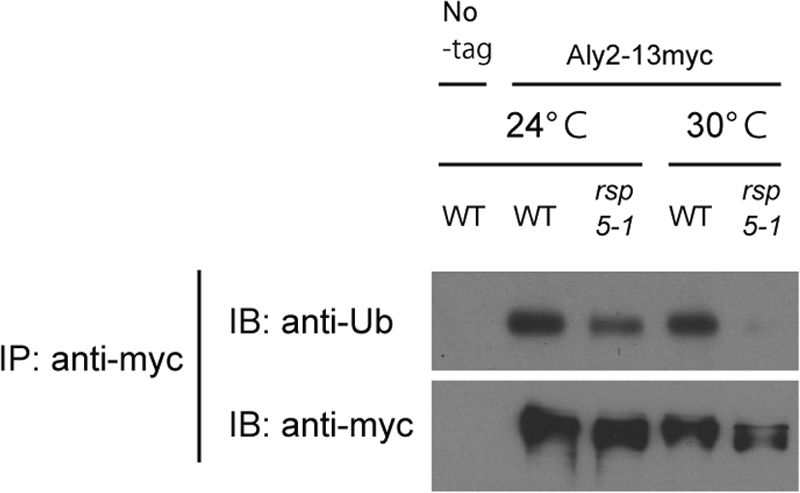

The coexpression with myc-Rsp5 shifted the band of GST-Aly2 to slower migration in the immunoblotting analysis, whereas GST-Aly2ΔC-PY showed only a fast-migrating band, together with an even faster-migrating band (Fig. 4A). Such different mobilities may arise from a difference in ubiquitination status of Aly2 associated with Rsp5. In addition, Aly2 was reported to be a good substrate for Rsp5 in vitro (4). To address the possibility that Aly2 is ubiquitinated by Rsp5 in vivo, we assessed the ubiquitination status of Aly2 in rsp5-1 cells with an antiubiquitin antibody immunoblotting analysis. The anti-ubiquitin signal was detected in Aly2 immunoprecipitates from wild-type cells, and the signal significantly diminished in those from rsp5-1 cells (Fig. 5, upper panel). Moreover, the fastest-migrating Aly2, which was detected in rsp5-1 cells but absent in wild-type cells, was not reactive with the antiubiquitin antibody, suggesting that it represents the unubiquitinated form (Fig. 5, lower panel). These changes were more remarkable at a higher temperature (Fig. 5). These results strongly suggest that Aly2 is ubiquitinated by Rsp5 in vivo.

FIG. 5.

Aly2 ubiquitination by Rsp5. TM141 (No-tag) and strains whose endogenous Aly2 was fused with 13myc, MK350 (WT) and RK768 (rsp5-1), were grown at 24°C or 30°C. Aly2-13myc immunoprecipitates from cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

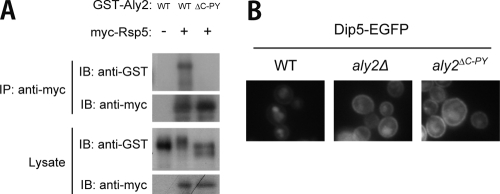

Aly2 interacts with Dip5 in an aspartic acid-dependent manner.

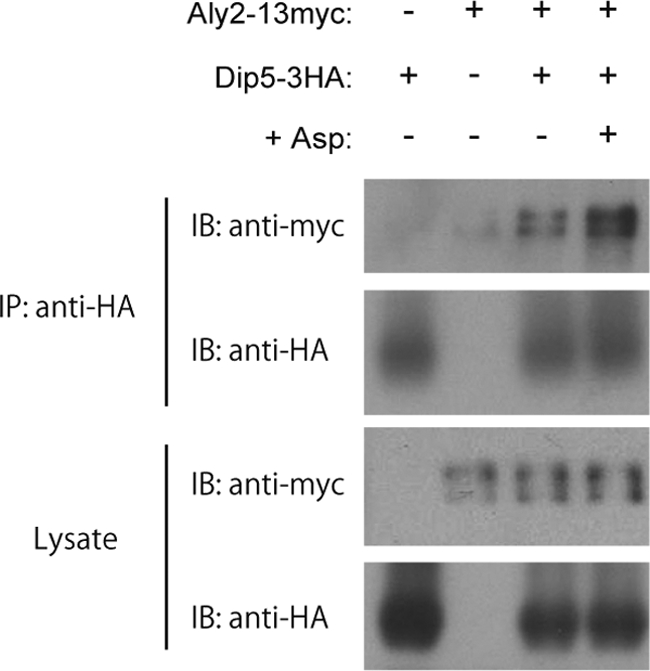

The physical interaction between Aly2 and Rsp5 suggested that Aly2 mediates ubiquitination of Dip5 by recruiting Rsp5 to Dip5 and thereby regulates endocytosis of Dip5. Thus, we next examined whether Aly2 also interacts with Dip5. To this end, we coexpressed chromosomally 13myc-tagged Aly2 (Aly2-13myc) and 3HA-tagged Dip5 (Dip5-3HA), and their interaction was examined in the presence of the cross-linking reagent dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) (DSP). A small amount of Aly2-13myc was coprecipitated with Dip5-3HA prior to aspartic acid treatment (Fig. 6), indicating the interaction between Aly2 and Dip5 under the normal growth condition, which is consistent with the constitutive ubiquitination and endocytosis of Dip5. Remarkably, the interaction between Aly2 and Dip5 was enhanced after aspartic acid treatment (Fig. 6). This strongly suggests that the induction of Dip5 ubiquitination and endocytosis by aspartic acid treatment results from the accelerated interaction between Aly2 and Dip5.

FIG. 6.

The substrate-dependent interaction between Aly2 and Dip5. Cell lysates from RK637 (− +), whose endogenous Dip5 was fused with 3HA, MK350 (+ −), whose endogenous Aly2 was fused with 13myc, and RK633 (+ +), whose endogenous Aly2 and Dip5 were fused with 13myc and 3HA, respectively, were subjected to immunoprecipitation. In the fourth lane, RK633 was treated with 200 μg/ml aspartic acid for 5 min before being lysed. Dip5-3HA immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

Phosphorylation in the N-terminal tail of Dip5 might contribute to its endocytosis.

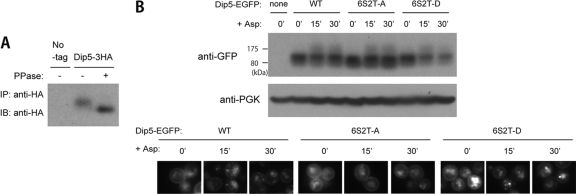

To address the mechanism by which Aly2 targets Dip5, we examined phosphorylation of Dip5, because mammalian β-arrestin interacts with GPCRs in a manner dependent on phosphorylation within the cytosolic tail of receptors (11, 14). Indeed, Dip5 is phosphorylated, because an in vitro phosphatase treatment converted the electrophoretic mobility of the Dip5 immunoprecipitate faster (Fig. 7A). Dip5 has a serine- and threonine-rich region in its cytosolic N-terminal tail (TSTSPRNSSSLDS, from the 10th to the 22nd residues in the amino acid sequence), and a phosphoproteomic survey demonstrated that at least five serine residues and one threonine residue other than 10T and 11S are phosphorylated (1). In order to examine the contribution of phosphorylation in this region toward Dip5 endocytosis, we constructed Dip5-EGFP mutants in which all six serine and two threonine residues (10T, 11S, 12T, 13S, 17S, 18S, 19S, and 22S) in this region were replaced with alanine (6S2T-A, mimicking the dephosphorylated state) or aspartic acid (6S2T-D, mimicking the phosphorylated state). Upon aspartic acid stimulation, the 6S2T-D mutant was endocytosed/degraded slightly more than the wild type, whereas the 6S2T-A mutant showed moderate resistance to the endocytosis/degradation (Fig. 7B). Thus, phosphorylation of these residues may promote the stimulated endocytosis of Dip5.

FIG. 7.

Possible roles of the N-terminal phosphorylation in Dip5 endocytosis. (A) Phosphorylation of Dip5. Cell lysates from TM141 (No-tag) or RK637 (Dip5-3HA) cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody. Then the immunoprecipitates were treated or not with λ-phosphatase in vitro, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. (B) The effects of mutations mimicking dephosphorylation or phosphorylation of the N-terminal tail of Dip5 on its endocytosis and degradation. dip5Δ strain RK722 transformed with pRK416 (none), pRK219 (WT), pRK220 (6S2T-A), or pRK221 (6S2T-D) was treated with 200 μg/ml aspartic acid for the indicated time periods. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. The images of fluorescence microscopy at each time point are shown in the lower panel.

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate that Aly2 mediates Dip5 endocytosis (Fig. 2). In our current model, as schematized in Fig. 8, ubiquitination of Dip5 required for endocytosis is accomplished by the formation of a transient ternary complex through physical interactions of Aly2 with both Dip5 and Rsp5. Thus, Aly2 serves as an adaptor that mediates interaction between Rsp5 and Dip5. Intriguingly, our results also have elucidated that Aly2 interacts with Dip5 in response to elevated aspartic acid availability. To our knowledge, this is the first example in yeast showing that substrate-dependent association of an arrestin-like protein with a PM protein is a key regulatory step of endocytosis. The closest relative Aly1 is likely to play a partially redundant role with Aly2 in the Dip5 endocytosis (Fig. 2J). This work, together with previous works revealing involvement of Ldb19, Ecm21, Csr2, Rod1, and Art5 in targeted endocytosis (12, 16, 17), proves that a total of seven arrestin-like proteins mediate endocytosis in yeast.

FIG. 8.

Schematic representation of the Aly2 function in Dip5 endocytosis. Aly2 interacts with Rsp5 via its C-terminal PY motif and is ubiquitinated by Rsp5. Aly2 also interacts with phosphorylated Dip5 in an aspartic acid-dependent manner, therefore serving as an Rsp5 adaptor to mediate Dip5 ubiquitination, which then accelerates endocytosis.

Despite the fact that arrestin-like proteins can, in common, function in recruiting Rsp5 to target PM proteins, they have distinct target specificities (12, 16, 17). Aly2 seems to selectively associate with Dip5, since none of the PM proteins tested by Pelham's group was targeted by Aly2 (17). In addition, Dip5 also showed remarkable preference for Aly2 over other arrestin-like proteins (Fig. 2J and data not shown). This stringent correspondence of arrestin-like proteins makes a striking contrast with Rsp5, which is involved in almost all known endocytosis events (6), suggesting that the fates of individual PM proteins, being endocytosed or not, essentially rely on their specific interaction with arrestin-like proteins.

In mammals, there exist at least six proteins in the ARRDC family which also contain both the arrestin domain and PY motifs. Although the significance of ARRDCs in endocytosis is yet to be examined, structural conservation with yeast arrestin-like proteins may imply the common mode of action of this family of proteins in regulating endocytosis of PM proteins in mammals. In fact, our preliminary studies have confirmed that TXNIP (15), one of the ARRDC family proteins, binds to Nedd4 and Nedd4-2, the Rsp5 homologs in mammals (data not shown).

The interaction between Aly2 and Dip5 was accelerated by aspartic acid treatment (Fig. 6), revealing the substrate-dependent recruitment of Rsp5 to Dip5. This result changes the question of how ubiquitination of a PM protein is accelerated by a stimulus into how the interaction with an arrestin-like protein is enhanced. One possible mechanism underlying this regulation is phosphorylation of Dip5 (Fig. 7A). Several lines of evidence suggest that phosphorylation of the cytosolic tail of PM proteins plays an important role in the endocytosis process and/or interaction with arrestin-like proteins in yeast as well as in mammals (5, 16). Mutations mimicking constitutive dephosphorylation or phosphorylation of the N-terminal serine/threonine-rich region of Dip5 caused moderate resistance or sensitivity, respectively, of Dip5 endocytosis to aspartic acid stimulation (Fig. 7B), and thus phosphorylation in this region seems to have positive roles in Dip5 endocytosis. However, because the effects of these mutations were not determinative, some additional events, e.g., phosphorylation in another region or specific conformational changes of Dip5, might be required for recognition of Dip 5 by Aly2.

We observed phosphorylation and ubiquitination of Aly2 (Fig. 5 and data not shown), although the physiological roles of these modifications remain unknown. Interestingly, Aly2 is supposed to be a substrate for cyclin-dependent kinases Cdc28 and Pho85 (7, 22, 24), suggesting that Aly2 function is regulated through cell cycle progression. On the other hand, Rsp5-dependent ubiquitination of arrestin-like proteins appears to have some impact on their function, since this property is shared among them, and in one case, Ldb19, a point mutation on the ubiquitination site abolishes its proper function in Can1 endocytosis (12). More extensive analyses, including identification of phosphorylation and ubiquitination sites on Aly2, are required to clarify the significance of these modifications in endocytosis processes.

It should also be pointed out that there seems to be a complex relationship between different arrestin-like proteins. As presented in Fig. 1, Aly2 negatively affects Can1 endocytosis whereas Ldb19 affects it positively. The degree of contribution of each protein depends on conditions: canavanine resistance was dominantly affected by LDB19 gene (Fig. 1E) as reported previously (12), whereas Can1 sorting in response to nutrient supplements was affected by LDB19 only partially and LDB19 disruption did not overcome the effect of ALY2 disruption under this condition (Fig. 1F). Previous reports also demonstrate that the endocytosis of a single transporter promoted by different stimulations often requires different arrestin-like proteins (12, 17). Further comprehensive analysis on the regulation of endocytosis of PM proteins by different arrestin-like proteins might provide a unified model by which cells properly reorganize PM proteins to adapt to various conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tomoko Andoh for a plasmid, Yutaka Hoshikawa for antibodies, Eric Hanson and Matthew Linden for checking the manuscript, and all members of the Maeda laboratory for various supports and discussion.

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (KAKENHI 14086203 and 21025008) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) (to T.M.) and a Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (to R.H.). R.H. and T.T. were the recipients of the Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for Young Scientists.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 October 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bodenmiller, B., J. Malmstrom, B. Gerrits, D. Campbell, H. Lam, A. Schmidt, O. Rinner, L. N. Mueller, P. T. Shannon, P. G. Pedrioli, C. Panse, H. K. Lee, R. Schlapbach, and R. Aebersold. 2007. PhosphoPep—a phosphoproteome resource for systems biology research in Drosophila Kc167 cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christianson, T. W., R. S. Sikorski, M. Dante, J. H. Shero, and P. Hieter. 1992. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene 110:119-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupre, S., D. Urban Grimal, and R. Haguenauer Tsapis. 2004. Ubiquitin and endocytic internalization in yeast and animal cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695:89-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta, R., B. Kus, C. Fladd, J. Wasmuth, R. Tonikian, S. Sidhu, N. J. Krogan, J. Parkinson, and D. Rotin. 2007. Ubiquitination screen using protein microarrays for comprehensive identification of Rsp5 substrates in yeast. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hicke, L., B. Zanolari, and H. Riezman. 1998. Cytoplasmic tail phosphorylation of the alpha-factor receptor is required for its ubiquitination and internalization. J. Cell Biol. 141:349-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hicke, L., and R. Dunn. 2003. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19:141-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt, L. J., B. B. Tuch, J. Villen, A. D. Johnson, S. P. Gygi, and D. O. Morgan. 2009. Global analysis of Cdk1 substrate phosphorylation sites provides insights into evolution. Science 325:1682-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horak, J. 2003. The role of ubiquitin in down-regulation and intracellular sorting of membrane proteins: insights from yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1614:139-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janke, C., M. M. Magiera, N. Rathfelder, C. Taxis, S. Reber, H. Maekawa, A. Moreno Borchart, G. Doenges, E. Schwob, E. Schiebel, and M. Knop. 2004. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast 21:947-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krogan, N. J., G. Cagney, H. Yu, G. Zhong, X. Guo, A. Ignatchenko, J. Li, S. Pu, N. Datta, A. P. Tikuisis, T. Punna, J. M. Peregrín-Alvarez, M. Shales, X. Zhang, M. Davey, M. D. Robinson, A. Paccanaro, J. E. Bray, A. Sheung, B. Beattie, D. P. Richards, V. Canadien, A. Lalev, F. Mena, P. Wong, A. Starostine, M. M. Canete, J. Vlasblom, S. Wu, C. Orsi, S. R. Collins, S. Chandran, R. Haw, J. J. Rilstone, K. Gandi, N. J. Thompson, G. Musso, P. St Onge, S. Ghanny, M. H. Lam, G. Butland, A. M. Altaf-Ul, S. Kanaya, A. Shilatifard, E. O'Shea, J. S. Weissman, C. J. Ingles, T. R. Hughes, J. Parkinson, M. Gerstein, S. J. Wodak, A. Emili, and J. F. Greenblatt. 2006. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 440:637-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lefkowitz, R. J., K. Rajagopal, and E. J. Whalen. 2006. New roles for beta-arrestins in cell signaling: not just for seven-transmembrane receptors. Mol. Cell 24:643-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin, C. H., J. A. MacGurn, T. Chu, C. J. Stefan, and S. D. Emr. 2008. Arrestin-related ubiquitin-ligase adaptors regulate endocytosis and protein turnover at the cell surface. Cell 135:714-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchese, A., M. M. Paing, B. R. Temple, and J. Trejo. 2008. G protein-coupled receptor sorting to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 48:601-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muoio, D. M. 2007. TXNIP links redox circuitry to glucose control. Cell Metab. 5:412-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikko, E., J. A. Sullivan, and H. R. Pelham. 2008. Arrestin-like proteins mediate ubiquitination and endocytosis of the yeast metal transporter Smf1. EMBO Rep. 9:1216-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikko, E., and H. R. Pelham. 2009. Arrestin-mediated endocytosis of yeast plasma membrane transporters. Traffic 10:1856-1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paiva, S., N. Vieira, I. Nondier, R. Haguenauer Tsapis, M. Casal, and D. Urban Grimal. 2009. Glucose-induced ubiquitylation and endocytosis of the yeast Jen1 transporter: role of lysine 63-linked ubiquitin chains. J. Biol. Chem. 284:19228-19236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regenberg, B., S. Holmberg, L. D. Olsen, and M. C. Kielland Brandt. 1998. Dip5p mediates high-affinity and high-capacity transport of L-glutamate and L-aspartate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 33:171-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Risinger, A. L., and C. A. Kaiser. 2008. Different ubiquitin signals act at the Golgi and plasma membrane to direct GAP1 trafficking. Mol. Biol. Cell 19:2962-2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shcherbik, N., Y. Kee, N. Lyon, J. M. Huibregtse, and D. S. Haines. 2004. A single PXY motif located within the carboxyl terminus of Spt23p and Mga2p mediates a physical and functional interaction with ubiquitin ligase Rsp5p. J. Biol. Chem. 279:53892-53898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi, X. Z., and S. Z. Ao. 2002. Analysis of phosphorylation of YJL084c, a yeast protein. Sheng Wu Hua Xue Yu Sheng Wu Wu Li Xue Bao (Shanghai) 34:433-438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ubersax, J. A., E. L. Woodbury, P. N. Quang, M. Paraz, J. D. Blethrow, K. Shah, K. M. Shokat, and D. O. Morgan. 2003. Targets of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1. Nature 425:859-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, G., J. Yang, and J. M. Huibregtse. 1999. Functional domains of the Rsp5 ubiquitin-protein ligase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:342-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yashiroda, H., D. Kaida, A. Toh-e, and Y. Kikuchi. 1998. The PY-motif of Bul1 protein is essential for growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae under various stress conditions. Gene 225:39-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]