Abstract

Circadian rhythms are common to most organisms and govern much of homeostasis and physiology. Since a significant fraction of the mammalian genome is controlled by the clock machinery, understanding the genome-wide signaling and epigenetic basis of circadian gene expression is essential. BMAL1 is a critical circadian transcription factor that regulates genes via E-box elements in their promoters. We used multiple high-throughput approaches, including chromatin immunoprecipitation-based systematic analyses and DNA microarrays combined with bioinformatics, to generate genome-wide profiles of BMAL1 target genes. We reveal that, in addition to E-boxes, the CCAATG element contributes to elicit robust circadian expression. BMAL1 occupancy is found in more than 150 sites, including all known clock genes. Importantly, a significant proportion of BMAL1 targets include genes that encode central regulators of metabolic processes. The database generated in this study constitutes a useful resource to decipher the network of circadian gene control and its intimate links with several fundamental physiological functions.

Many physiological phenomena in almost all of organisms are regulated in a circadian manner. This is possible through the function of an intrinsic biological clock or pacemaker. The circadian clock operates independently of external cues, but it has remarkable plasticity and so can adapt to changing environmental conditions. Dysfunctions of the circadian clock are associated with a wide variety of disorders in humans, including insomnia, depression, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer (13, 35, 40). The central circadian pacemaker in mammals is located within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the anterior hypothalamus (13).

A critical advance in the field has been the discovery of circadian clocks present in peripheral tissues and in cultured cells (13). The SCN appears to function by orchestrating peripheral clocks (37), likely by using a specific group of humoral signals as synchronizing elements, including glucocorticoids and retinoic acid (12). This complex network relies on a highly controlled system of gene expression, in which interlocked transcriptional-translational feedback loops operate (20, 31, 50). Also, microarray studies have revealed that ca. 10 to 15% of all transcripts in different tissues display circadian oscillation (3, 9, 26, 38). More recent data suggest that the expression of as much as 50% of all genes oscillates in a circadian manner (30). These notions indicate that global mechanisms of gene expression, specifically chromatin remodeling (23), must operate to accommodate these genome-wide oscillations.

The transcriptional-translational feedback loops that constitute the core circadian oscillator have been dissected. At the core of the circadian machinery lies the BMAL1 protein, a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) type transcription factor that forms hetero-complexes with either CLOCK or NPAS2, two other bHLH nuclear activators with different tissue distributions (10, 50). These dimers activate the transcription of clock-controlled genes (CCGs) and of genes encoding other elements of the clock machinery, specifically the Per and Cry genes. Once synthesized, PERs and CRYs inhibit CLOCK/BMAL1 activation potential, resulting in the downregulation of their own transcription (31). The circadian transcription of the Bmal1 gene is itself regulated by nuclear receptors positively by RORs and negatively by REV-ERBs (2, 29, 36). Importantly, Bmal1-deficent mice exhibit arrhythmic locomotor activity in constant darkness, a unique case as single-gene ablation among all clock genes (5), indicating that BMAL1 is indeed indispensable to generate circadian gene expression.

DNA microarray analyses in both SCN and peripheral tissues (26, 38, 46) and further bioinformatic analyses determined that circadian transcription may be elicited through three promoter elements (E-box, RORE, and DBPE) (47, 52). Among these, the E-box appears to play a major role as it is highly abundant in the mammalian genome and responsible in driving the expression of most CCGs (47). However, with the exception of a limited number of individually studied genes (11, 24), the extent of BMAL1-mediated control of circadian transcription at a genome-wide level remains unknown.

We describe here results obtained by a systematic analysis using a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-based technology and a genome-wide microarray. We have applied ChIP-on-chip (ChIP-chip) (17) and ChIP coupled with ultra-high-throughput DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq) methods (4, 7, 15, 33) to reveal BMAL1 target genes at a whole genome level. All known CCGs driven by E-boxes are present in our systematic ChIP results and the profiling of BMAL1 targets reveals strict relationship with metabolism. Our analysis has revealed unexpected features of circadian gene control and constitutes a valuable resource to study the link between clock control and cellular metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

NIH 3T3 and WI38 cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) supplemented with 10% newborn bovine serum (NBS; ICN Biomedicals, Inc.) and antibiotics.

Animals.

Male BALB/c mice purchased 5 weeks postpartum from Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan) were exposed to 2 weeks of 12:12 light-dark (LD) cycles and then kept in complete darkness as a continuation of the dark phase of the last LD cycle. Liver mRNA levels were examined in the third dark-dark (DD) cycle. Adult Bmal1−/− (5) and wild-type mice were kept in a LD cycle and killed at Zeitgeber time 0 (ZT0) and ZT12. Tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until processed for RNA. All protocols of experiments using animals in the present study were approved by the OBI (Osaka Bioscience Institute) Animal Research Committee.

Antibody.

Purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)-mBMAL1 N-terminal (amino acids 1 to 100) antigen (41) was produced to immunize rabbits. After removing possible GST-recognizing antibody by using HiTrap-NHS conjugated with GST, the antiserum was subjected to affinity purification using HiTrap-NHS conjugated with the antigen. The anti-mBMAL1 antibody specifically recognizes its target protein in immunochemical analysis (see Fig. S10 [all supplemental material may be found at this URL at http://home.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/anatomy2/]). Normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as a control.

ChIP.

NIH 3T3 cells were cultured in 10-cm plates to 1.5 × 107 cells, and 10 plates were used per immunoprecipitation. WI38 cells were cultured in 10-cm plates to 1.5 × 106 cells, and five plates were used per immunoprecipitation. Cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature with swirling. Glycine was added to a final concentration of 0.125 M, and the incubation was continued for an additional 15 min. After washing twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were harvested by scraping, pelleted, and resuspended in 500 μl of ice-cold cell lysis buffer (5 mM PIPES [pH 8.0], 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40, and protease inhibitors). After incubation at 4°C for 15 min, samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm at 4°C for 5 min, and the precipitations were resuspended in 1 ml of nuclei lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and protease inhibitors). After incubation on ice for 20 min, the samples were sonicated 10 times for 10 s each time at intervals of 50 s with a Microson (Misonix, Inc.). Samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. After removal of a control aliquot (whole-cell extract), supernatants were diluted 10-fold in ChIP dilution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 167 mM NaCl, 1.1% Triton X-100, 0.11% sodium deoxycholate, protease inhibitor). Nonspecific background was removed by incubating samples with a salmon sperm DNA/protein A-agarose slurry at 4°C for 2 h with rotation. The samples were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm at 4°C for 2 min, and a 0.1 volume of the recovered supernatants was stored as an input sample, whereas the rest was incubated overnight with 3 μg of indicated antibodies at 4°C with rotation. The immunocomplexes were collected with 70 μl of salmon sperm DNA/protein A-agarose at 4°C for 3 h with rotation. The beads were sequentially washed with the following buffers: radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer-150 mM NaCl, RIPA buffer-500 mM NaCl, and LiCl wash solution. Finally, the beads were washed twice with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM EDTA. The immunocomplexes were then eluted by the addition of 200 μl of ChIP direct elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS) and rotated for 15 min at room temperature and incubated for 4 h at 65°C. The DNA was recovered by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extraction and ethanol precipitation.

Sequencing.

Bmal1-bound DNA was purified by SDS-PAGE to obtain 150- to 250-bp fragments and sequenced on an Illumina GA sequencer. About 15,000 to 20,000 clusters were generated per “tile,” and 26 cycles of the sequencing reactions were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Tiling array.

ChIP and control samples were amplified by two cycles of in vitro transcription and hybridized on separate Affymetrix human promoter 1.0 oligonucleotide tiling arrays as described previously (49). Enrichment values (ChIP/control) were calculated with the MAT algorithm as described previously (16, 49).

Data processing.

The obtained sequences were mapped onto mouse genomic sequences (mm9 as of UCSC Genome Browser [http://genome.ucsc.edu/]) using the sequence alignment program Eland. Unmapped or redundantly mapped sequences were removed from the data set. For uniquely mapped sequences, relative positions to RefSeq genes were calculated based on the respective genomic coordinates. Genomic coordinates of exons and other information of the RefSeq transcripts are as described in mm9 as of UCSC Genome Browser. GO (as of 14 June 2007) and KEGG (release 42) terms were associated with RefSeq genes by using loc2go (as of 14 June 2007) using NCBI Entrez Gene database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=gene). Details and rationalization of the procedure were as described previously (43).

Motif analysis.

MEME (for Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation) with default parameters was used to identify statistically overrepresented consensus motifs within the inferred binding sites.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Each quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed using the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system as described previously (25), The PCR primers were designed with Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems), and the sequences of the primers are shown in Table S5 at the URL in “Antibody,” above. The reaction was first incubated at 50°C for 2 min and then at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

Rhythmicity and acrophase estimation.

We use similarity between data and the best-fitting cosine as a measure of rhythmicity. This is in line with the popular method for testing rhythmicity in microarray data, where a cosine fit is selected that gives maximal correlation with data (51). We find the cosine fits first and use Pearson correlation coefficient to quantify the closeness to the ideal oscillation, which we call “rhythmicity.” Rhythmicity is directly related to robustness of circadian gene cycling. Each set, not average, of PCR data is fit for a cosine curve using nonlinear linear squares as the following equation, where bi represents the acrophase: si (t) = ai cos [2π (t − bi)/24] + ci.

The circadian rhythmicity is assumed for all samples, and the period is fixed to 24 h (51). A higher correlation means a higher rhythmicity, which reaches a maximum at 1. Higher sample variance implies less robustness of oscillation and poorer rhythmicity. Statistical significance of the rhythmicity is tested against random surrogates of the same sample size and dynamic range as PCR data. P values from one-sided t test estimate separation between the data and the surrogate. A nonoverlapping linear trend exists between rhythmicity and the P value in rhythmicity interval between 0.7 and 1.0, which corresponds to P value below 0.2 (see Fig. S6 at the URL in “Antibody,” above). This implies the rhythmicity above 0.7 is above the chance level.

IV-ROMS.

NIH 3T3 cells at 105 plated in Opti-MEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% NBS in 35-mm dishes were transfected with the desired plasmids by using Lipofectamine and Plus reagent (Invitrogen). At 24 h after transfection, the medium was exchanged for 100 nM dexamethasone containing medium, and 2 h later this medium was replaced with Opti-MEM supplemented with 1% NBS and 0.1 mM luciferin-10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). Bioluminescence was measured by using in vitro real-time oscillation monitoring system (IV-ROMS; Hamamatsu Photonics) as described previously (2, 22, 52).

Luciferase assay.

NIH 3T3 cells were cultured and transfected with the desired plasmids by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection, and cell lysates were prepared and then used in the dual luciferase assay system (Promega).

Microarray analysis.

Applied Biosystems mouse genome survey arrays were used to analyze the transcriptional profiles of liver samples as described previously (48). Digoxigenin-UTP-labeled cRNA was generated and linearly amplified from 2 μg of total RNA using Applied Biosystems Chemiluminescent RT-IVT Labeling Kit V2.0 according to the manufacturer's protocol. Portions (10 μg) of labeled cRNA were hybridized to each pre-hybridized microarray in a 1.5-ml volume at 55°C for 16 h. Array hybridization and chemiluminescence detection were performed with a Applied Biosystems chemiluminescence detection kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. Images were collected for each microarray using a 1700 analyzer. Images were auto-gridded, and the chemiluminescent signals were quantified, corrected for background and spot, and spatially normalized.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed in a single step by PCR to modify the specific hDbp CCAATG element or CATGTG to AGTCAT or CATTGG, respectively. Mutated DNA was identified by DpnI selection for hemimethylated DNA, and the sequences were checked. The oligonucleotide primers used were 5′-CGG ACC CAG AGG CCC TAC TGA CTG TGC GTC TCA AGG (631mut), 5′-CCC CCA GTA CCG CCT CCT ACT GAG CAA ATG TAG GTC AGT G (738 mut), 5′-CCC CTC CCG CCT GCC TTA CTG ACC CAA ACT GGG (784 mut), and 5′-GCA CGA GCA GAG CCA TTG GCT TCC CCC TCC C (E-box-like, CATTGG).

RESULTS

ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq identify BMAL1 targets.

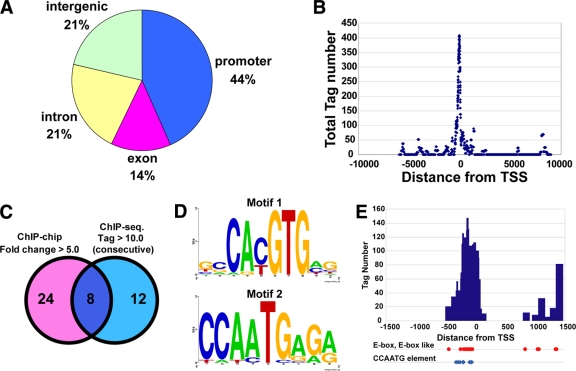

For ChIP experiments, we generated specific antibody against BMAL1. To identify the BMAL1-binding sites at a genome-wide level, we performed a ChIP-chip analysis. We used WI38 human fibroblasts from which we immunoprecipitated BMAL1 (or IgG as control) to use it for hybridization on human promoter tiling arrays. The number of sites with the ratio of BMAL1/IgG, >5.0 and >3.0 were 32 and 183, respectively (>5.0 in Table S1 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods; >3.0 with ChIP-seq signals in Table S2 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). As predicted, the clock genes—Per1, Per2, Cry1, and Cry2—were identified among the genes with >5.0 ratio (Table 1). To further identify and confirm the BMAL1-DNA interaction at high resolution, we performed ChIP-seq using NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblasts. We obtained 2,990 tags from BMAL1-bound DNA compared to 1,248 tags in the control whole-cell lysate. We then collected 172 ChIP-seq signals with more than 10 consecutive tags (1 tag consists of 100 bp; consecutive tags were defined as tags situated directly adjacent to each other). Most of BMAL1-binding sites (44%) were located in promoter regions (Fig. 1A), and almost all of these sites were close to the TSS (transcriptional start site) (Fig. 1B). We uncovered 32 BMAL1-binding sites on promoters with a >5.0-fold change from ChIP-chip analysis (see Table S1 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods), whereas 20 sites with more than 10.0 consecutive tags from ChIP-seq (Table 1). Eight overlapped sites were found in the promoter regions of the genes Per1, Per2, Cry1, Cry2, Rev-erbα (Nr1d1), Dbp, and Tef, as well as in the promoter of an as-yet-unidentified gene, Gm129 (Fig. 1C, Table 1). Substantial tags were accumulated in each site where BMAL1 binds (see Fig. S1 to S4 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). Motif analysis by MEME (using motif's length of 5 to 10 bp) on identified BMAL1-binding sites from ChIP-seq unexpectedly revealed two consensus DNA-binding motifs (Fig. 1D). The first consensus motif (Motif1) was CACGTG (E-value = 2.9e−14), which predictably corresponded to the E-box. The second motif (Motif2) was CCAATG (E-value = 5.5e−1), a motif highly similar to the so-called CCAAT-box, a well-characterized promoter element (21). In eight common BMAL1-binding sites from both ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip analyses, most of the two consensus motifs (E-box or E-box-like and CCAATG elements) were located upstream to the TSS (Fig. 1E; also see Table S3 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). This result is consistent with studies (24, 47) indicating that the CLOCK/BMAL1 complex positively regulates the activity of E-box containing promoters.

TABLE 1.

Result of ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip analysesa

| Analysis details (ChIP-chip fold change) and geneb | Chromosome (mouse) | Position |

Distribution | Tag no. | ChIP-chip fold change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | |||||

| ChIP-seq, tag > 10.0, c (>5.0) | ||||||

| Per2 | 1 | 93355701 | 93355800 | Exon 1, intron 1 | 10 | 20.49 |

| 93355801 | 93355900 | Exon 1 | 52 | |||

| 93355901 | 93356000 | Promoter | 34 | |||

| 93356001 | 93356100 | Promoter | 50 | |||

| Cry2 | 2 | 92264001 | 92264100 | Intron 3 | 10 | 5.81 |

| 92274301 | 92274400 | Promoter | 28 | |||

| 92274401 | 92274500 | Promoter | 13 | |||

| Gm129 | 3 | 95686101 | 95686200 | Promoter exon 1 | 19 | 31.91 |

| 95686201 | 95686300 | Promoter | 17 | |||

| Dbp | 7 | 52960101 | 52960200 | Promoter | 20 | 9.07 |

| 52960201 | 52960300 | Promoter | 7 | |||

| 52960301 | 52960400 | Promoter | 5 | |||

| 52960401 | 52960500 | Promoter | 10 | |||

| 52961401 | 52961500 | Intron 1 | 11 | |||

| 52963001 | 52963100 | Intron 2 | 11 | |||

| 52963101 | 52963200 | Intron 2 | 15 | |||

| Cry1 | 10 | 84647801 | 84647900 | Promoter | 19 | 8.75 |

| 84647901 | 84648000 | Promoter | 5 | |||

| 84648001 | 84648100 | Promoter | 16 | |||

| 84648101 | 84648200 | Promoter | 27 | |||

| Per1 | 11 | 68908301 | 68908400 | Intergenic | 52 | 87.65 |

| 68908401 | 68908500 | Intergenic | 24 | |||

| 68908501 | 68908600 | Intergenic | 15 | |||

| 68908601 | 68908700 | Intergenic | 22 | |||

| 68908701 | 68908800 | Intergenic | 8 | |||

| 68912201 | 68912300 | Promoter | 12 | |||

| 68912301 | 68912400 | Promoter | 10 | |||

| 68912401 | 68912500 | Exon 1 | 10 | |||

| Rev-erbα | 11 | 98635101 | 98635200 | Intron 1 | 81 | 10.3 |

| 98635201 | 98635300 | Intron 1 | 18 | |||

| 98635301 | 98635400 | Intron 1 | 5 | |||

| 98635401 | 98635500 | Intron 1 | 32 | |||

| 98636501 | 98636600 | Promoter exon 1 | 12 | NDc | ||

| 98636601 | 98636700 | Promoter | 27 | |||

| 98644601 | 98644700 | Intergenic | 17 | |||

| 98644701 | 98644800 | Intergenic | 50 | |||

| 98644801 | 98644900 | Intergenic | 19 | |||

| Tef | 15 | 81641301 | 81641400 | Intron 1 | 64 | 5.02 |

| 81641401 | 81641500 | Intron 1 | 69 | |||

| 81641501 | 81641600 | Intron 1 | 10 | |||

| 81641601 | 81641700 | Intron 1 | 24 | |||

| ChIP-seq, tag > 10.0, c (<5.0) | ||||||

| Igsf8 | 1 | 174240201 | 174240300 | Intergenic | 13 | 2.66 |

| 174240301 | 174240400 | Intergenic | 15 | |||

| E530001K10RikMir670 | 2 | 94113401 | 94113500 | Promoter | 14 | ND |

| 94113501 | 94113600 | Promoter | 17 | |||

| 2310035K24Rik | 2 | 131030401 | 131030500 | Intergenic | 13 | ND |

| 131030501 | 131030600 | Intergenic | 26 | |||

| 131030601 | 131030700 | Intergenic | 8 | |||

| 6 | 91549101 | 91549200 | Intergenic | 49 | ND | |

| 91549201 | 91549300 | Intergenic | 15 | |||

| Dec2 | 6 | 145804301 | 145804400 | Intergenic | 44 | 3.57 |

| 145804401 | 145804500 | Intergenic | 32 | |||

| Crispld2 | 8 | 122570301 | 122570400 | Intron 1 | 11 | ND |

| 122570401 | 122570500 | Intron 1 | 10 | |||

| Nptn | 9 | 58429801 | 58429900 | Promoter | 11 | ND |

| 58429901 | 58430000 | Promoter | 26 | |||

| Hlf | 11 | 90279301 | 90279400 | Intergenic | 7 | ND |

| 90279401 | 90279500 | Intergenic | 26 | |||

| 90279501 | 90279600 | Intergenic | 22 | |||

| Rsad1 | 11 | 94410201 | 94410300 | Intron 1 | 12 | ND |

| 94410301 | 94410400 | Exon 1 | 26 | |||

| Rev-erbβ | 14 | 19071001 | 19071100 | Intron 1 | 22 | ND |

| 19071101 | 19071200 | Intron 1 | 43 | |||

| 19071201 | 19071300 | Intron 1 | 23 | |||

| Ighmbp2 | 19 | 3282901 | 3283000 | Promoter | 10 | ND |

| Mrpl21 | 3283001 | 3283100 | Promoter exon 1 | 11 | ||

| X | 137054801 | 137054900 | Intergenic | 10 | ND | |

| 137054901 | 137055000 | Intergenic | 13 | |||

| ChIP-seq, tag > 10.0, nc (>2.0) | ||||||

| Cops7b | 1 | 88483601 | 88483700 | Promoter | 15 | 2.42 |

| 88483701 | 88483800 | Exon 1 | 6 | |||

| Per3 | 4 | 150418701 | 150418800 | Promoter exon 1 | 29 | 2.65 |

| 150418801 | 150418900 | Promoter | 7 | |||

| 150418901 | 150419000 | Promoter | 5 | |||

| C030048B08Rik Pex1 | 5 | 3596001 | 3596100 | Exon 1, promoter | 10 | 5.04 |

| 3596101 | 3596200 | Exon 1 | 7 | |||

| Krr1 | 10 | 111409701 | 111409800 | Promoter | 12 | 3.88 |

| Pex13 | 11 | 23566301 | 23566400 | Promoter | 11 | 3.15 |

| Pus10 | Exon 2 | |||||

| Thra | 11 | 98608901 | 98609000 | Intron 1 | 13 | 3.16 |

| Klf11 | 12 | 25336001 | 25336100 | Promoter | 11 | 5.16 |

| Ccdc85b | 19 | 5457501 | 5457600 | Promoter exon 1 | 11 | 2.53 |

Eight genes are overlapped from ChIP-seq with high tags (more than 10 tags and consecutive) and ChIP-chip with a >5.0-fold change. Eleven genes and 1 micro-RNA are extracted from ChIP-seq with more than 10 tags (consecutive) and ChIP-chip with a <5.0-fold change. Ten genes are extracted from ChIP-seq with more than 10 tags (nonconsecutive) and ChIP-chip with a >2.0-fold change. The 2-kb region upstream of transcription start site is defined as the promoter. The chromosome, start, end, distribution, and tag number columns indicate ChIP-seq data from mouse fibroblasts. The ChIP-chip fold change shows ChIP-chip data from human fibroblasts.

c, consecutive; nc, nonconsecutive. The ChIP-chip fold change for each type of analysis is indicated in parentheses.

ND, not determined.

FIG. 1.

High-resolution genome-wide mapping of the BMAL1 target with ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip. (A) Distribution of binding sites across the genome. The 2-kb region upstream of transcription start site (TSS) is defined as the promoter. (B) Distribution of tags from ChIP-seq relative to the TSS. (C) BMAL1 binds 20 sites from ChIP-seq in NIH 3T3 cells (tag numbers were more than consecutive 10.0) and 32 sites from ChIP-chip in WI38 cells (fold change is more than 5.0). Eight sites are overlapped in ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip. (D) Logo of the BMAL1 binding element that is identified as 20 sites from ChIP-seq. Motif 1: width, 10; sites, 50; log likelihood, 407; E-value, 2.9e−14. Motif 2: width, 9; sites, 16; log likelihood, 158; E-value, 5.5e−1. (E) Distribution of tags from eight genes and locations of E-box, E-box-like, and CCAATG elements.

In the ChIP-chip analysis with the human lung fibroblast cells, high signals were detected in the Per1 promoter region (87.65-fold change versus IgG) and in the intron region of Rev-erbα (10.3-fold change versus IgG) on human chromosome 17. ChIP-seq analysis with mouse embryonic fibroblasts revealed the positions of BMAL1 occupancy at higher resolution. Two clusters were detected upstream of Per1 and three clusters were detected on the Rev-erbα locus on mouse chromosome 11 (see Fig. S3 and S4 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). By focusing further on the 5 kb upstream of the Per1 gene TSS, two E-box and two CCAATG elements were located with high tag numbers (see Fig. S3 and S4 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). The precise locations of ChIP-seq tags for other 6 genes (Per2, Cry1, Cry2, Dbp, Tef, and Gm129) are also represented in Fig. S1 to S4 and Table S3 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods. It is notable that these elements are highly conserved in the genomes of vertebrates, underscoring the importance of these regions during evolution.

BMAL1 target genes display circadian expression.

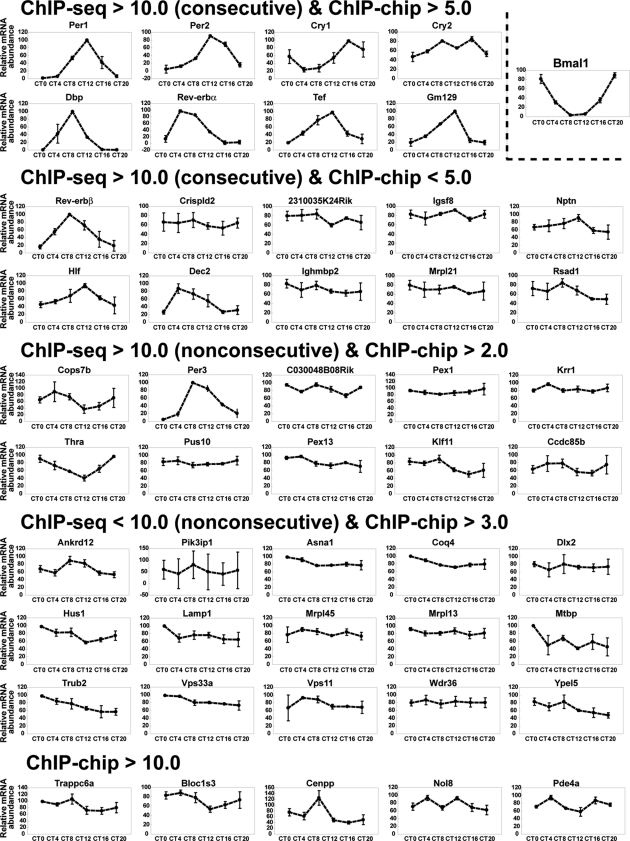

To determine whether BMAL1 target genes are expressed in a circadian manner, we performed quantitative RT-PCR using mouse liver tissues sampled every 4 h. All eight overlapped genes (categorized as ChIP-seq > consecutive 10.0 and ChIP-chip > 5.0) displayed robust circadian oscillation with high amplitudes in the liver (Fig. 2). In the other category (ChIP-seq > consecutive 10.0 and ChIP-chip < 5.0, ChIP-seq > nonconsecutive 10.0 and ChIP-chip > 2.0), several genes such as Rev-erbβ (Nr1d2), Hlf, Dec2 (Bhlhe41), Per3, Thra, and Klf11 exhibited clear circadian expression. In the lower category (ChIP-seq < nonconsecutive 10.0 and ChIP-chip > 3.0, ChIP-chip > 10.0 without ChIP-seq signals), some genes such as Asna1, Coq4, Hus1, Mrpl45, Vps33a, Vps11, and Bloc1s3 displayed weak circadian expression and very small amplitude in oscillation. The analysis by cosine fitting confirmed theses features of cyclic expression (see Fig. S5 to S7 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods).

FIG. 2.

Temporal mRNA expression of BMAL1-regulating genes. The temporal mRNA expression of selected genes in mouse liver was measured by using quantitative RT-PCR. The abscissa indicates the circadian time (CT), and ordinate indicates the mRNA amounts. The relative level of each mRNA is normalized to the corresponding G3-PDH RNA level. The maximum RNA amount is set to 100. The data are presented as means ± the standard errors (SE) of triplicate samples.

The CCAATG element contributes to robust circadian expression.

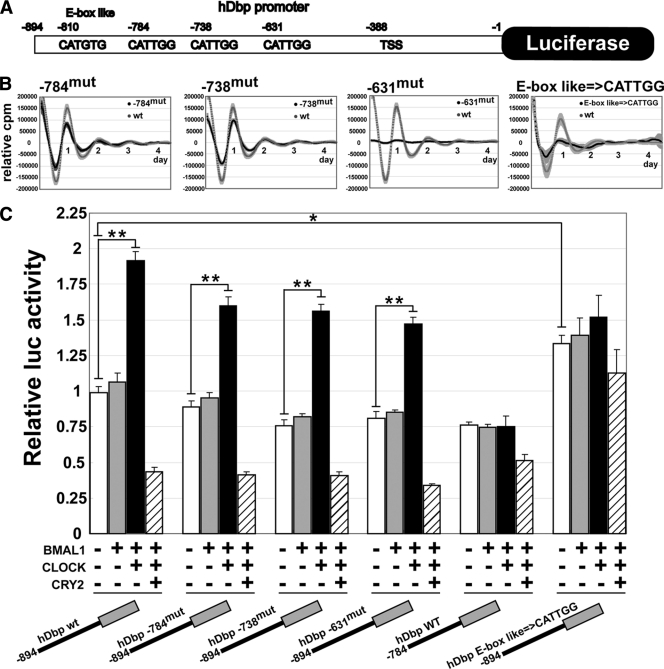

Since the CCAATG element identified in the present study has not been examined as a clock element to date, we sought to determine whether the CCAATG element located in the predicted BMAL1-binding sites is indeed functional. To do so, we generated mutations within the CCAATG elements to AGTCAT in a hDbp:luciferase reporter construct (hDbp/pGL3B, Fig. 3A). In the hDbp promoter region (−894 to −1 from the translational start site), one E-box-like and three CATTGG elements are located with adequate tag numbers from ChIP-seq (see Table S3 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with the hDbp/pGL3B reporter or its mutated forms and then stimulated with 100 nM dexamethasone. Light emission was measured in the presence of luciferin after dexamethasone treatment. Although mutations at the bp −784 or bp −738 (−784mut or −738mut) site had little effect on the amplitude of circadian oscillation, mutation at bp −631 (−631mut) caused a loss of robust circadian oscillation and a drastic decrease in the amplitude compared to hDbp (wt) (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, disruption of circadian oscillation was observed by using a promoter construct in which the E-box-like sequence was replaced by the CATTGG element. These results were consistent with those of additional luciferase (luc) assays (Fig. 3C). hDbp-784mut, hDbp-738mut, and hDbp-631mut expressing BMAL1 and CLOCK displayed a lower luciferase activity compared to −894 hDbpwt (P < 0.005, Fig. 3C, black bar [Student t test]). A deletion construct with −784 to −1 of hDbp/pGL3B (−784 hDbpwt), which did not include E-box-like sequence, also exhibited a reduced luciferase activity. Interestingly, a promoter construct with mutation from the E-box-like sequence to the CATTGG element (hDbpE-C) displayed a high luciferase activity. Ectopic coexpression of BMAL1 and CLOCK stimulated transcription from the basal reporter, whereas they had no effect on the −784 hDbpwt and hDbpE-C mutant reporters. In addition, CRY2 inhibited the BMAL1/CLOCK-mediated transactivation in all of the CCAATG-based reporters, indicating that CRY-mediated negative regulation is through a pathway independent of the E-box-like sequence on promoters (see Fig. S8 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). These results suggest that the CCAATG element contributes to activate hDbp transcription and that the E-box-like sequence is critical for the regulation of circadian oscillation.

FIG. 3.

E-box-like and CATTGG elements on the hDbp promoter required for circadian oscillation and transactivation. (A) Schematic representation of E-box-like and CATTGG elements on hDbp promoter. +1 corresponds to the translational start site. TSS, transcriptional start site. (B) −784mut and −738mut hDbp:Luc exhibit a low-amplitude oscillation, and −631mut exhibits a dampened oscillation of very low amplitude compared to the wild type (wt). Mutated construct that is converted from E-box-like to CATTGG disrupted circadian activity. Black and gray lines indicate the bioluminescence of mutants and the wild type, respectively. Each shadow indicates the standard error of five or six samples. The abscissa indicates the day, and the ordinate indicates the relative luciferase intensity. (C) The effects of overexpression of BMAL1 and/or CLOCK and CRY2 protein on the transactivation of each hDbp construct are evaluated by using a luciferase assay. The basal transcriptional activity of hDbp promoter wild type (WT) (bp −894 to −1 from the translational start site)/pGL3B was set to 1. The data represent the means ± the SE of eight samples (*, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.0001; Student t test).

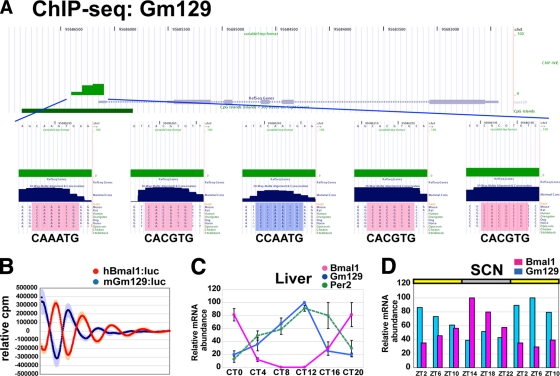

Gm129 is a novel CCG.

Our ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip analyses pointed at Gm129 as a novel candidate for a BMAL1-regulated gene. The promoter region of Gm129 includes three E-box elements, one E-box-like element, and one CCAATG element with mild tag numbers of ChIP-seq (Fig. 4A). We hypothesized that the circadian expression of Gm129 is linked to activation elicited by BMAL1. To test this hypothesis, we subcloned a DNA fragment corresponding to the region from bp −2033 to −1 upstream of the ATG and generated a luciferase reporter construct (Gm129/pGL3B) to perform an in vitro real-time luminescence monitoring. Gm129/pGL3B exhibited a robust circadian oscillation that was antiphasic to hBmal1/pGL3B (Fig. 4B). mRNA levels of Gm129 in the liver also showed a circadian oscillation with an amplitude as high as Per2 (Fig. 4C). Gm129 and Bmal1 are almost antiphasic in expression, with acrophases separated by 10 h (see Fig. S5B at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). In the SCN, the mammalian circadian central pacemaker, Gm129 expression displayed a circadian oscillation as robust as Bmal1 (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that Gm129 is a novel CCG.

FIG. 4.

Gm129 shows circadian expression. (A) BMAL1 binding promoter of Gm129 from ChIP-seq in UCSC genome browser view. (B) Gm129 and Bmal1 promoter-luciferase reporter activities in NIH 3T3 cells. (C) Temporal mRNA expression of Bmal1, Per2, and Gm129 in mouse liver by quantitative RT-PCR. The abscissa indicates the time circadian time (CT), and ordinate indicates the mRNA amounts. The relative level of each mRNA is normalized to the corresponding G3-PDH RNA levels. The maximum RNA amount is set to 100. The data are presented as the means ± the SE of triplicate samples. Gm129 shows circadian expression. The expression of Gm129 and Bmal1 is almost anti-phasic with acrophases separated by 10 h. The temporal profiles of Gm129 and Bmal1 expression are distinct [gene × time = F(5, 24) = 60.421, P < 0.0001, analysis of variance]. (D) Temporal mRNA expression of Bmal1 and Gm129 in mouse suprachiasmatic nuclei as determined by quantitative RT-PCR. The abscissa indicates the Zeitgeber time (ZT), and the ordinate indicates the mRNA amounts. The relative levels of each mRNA are normalized to the corresponding G3-PDH RNA levels. The maximum RNA amount is set to 100. The data are presented as means.

Two groups of CCGs under BMAL1 control.

We then studied the expression profiles for representative liver genes at ZT0 and ZT12, the trough and peak of Bmal1 expression, respectively (46), comparing wild-type and Bmal1−/− mice (Fig. 5). While Bmal1 was highly expressed at ZT0 and at almost undetectable levels at ZT12 in wild-type mice, all BMAL1 target genes except Cry1 were expressed in an anti-phase manner (Fig. 5, solid line). In contrast, the expression of Dbp, Rev-erbα, Rev-erbβ, Gm129, and Dec2 was drastically decreased at both ZT0 and ZT12 in Bmal1−/− mice (Fig. 5, dashed line). Importantly, this loss of expression was not observed for Per1, Per2, Cry1, Cry2, Tef, and Hlf. Thus, at least two distinct groups of CCGs appear to be controlled differentially by BMAL1. The first group (including Dbp, etc.,) strictly requires BMAL1 to display circadian oscillation, since expression is virtually abolished in Bmal1−/− mice. The second group (including Per1, etc.) of genes, although circadian, undergoes a rhythmic regulation that is BMAL1 independent. To gain further insights into the molecular regulation by BMAL1, we performed comparative whole-genome microarrays at ZT0 and ZT12 in the liver of wild-type and Bmal1−/− mice. We identified 23 genes that fluctuated in wild-type mice and displayed reduced expression levels in Bmal1−/− mice (Table 2). Because 20 genes, besides Per3, Rev-erbβ, and Dbp, were not found in our ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip analyses, we conclude that these genes are located downstream of BMAL1 but are not directly regulated by BMAL1.

FIG. 5.

Expression patterns of BMAL1-regulating genes in Bmal1−/− mouse. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of selected genes whose expression is dependent on Bmal1 was performed. Solid lines with circles and dotted lines with triangles represent wild-type and Bmal1−/−, respectively. The relative levels of each mRNA are normalized to the corresponding G3-PDH RNA level. The minimum RNA amount is set to 1. The data are presented as the means ± the SE of three samples.

TABLE 2.

Results of competitive microarray analysis of Bmal1-regulated genes in the livers of wild-type and Bmal1−/− micea

| Gene | Description | Wild-type mice |

Bmal1−/− mice |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZT0 | ZT12 | ZT0 | ZT12 | ||

| Mfsd2 | Major facilitator superfamily domain containing 2 | 11.07 | 101.98 | 16.81 | 18.49 |

| Mafb | v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family, protein B (avian) | 39.76 | 142.58 | 36.71 | 32.20 |

| Maff | v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family, protein F (avian) | 2.42 | 13.94 | 2.59 | 2.35 |

| Brunol5 | Bruno-like 5, RNA-binding protein (Drosophila) | 0.46 | 2.21 | 0.65 | 1.00 |

| Gpr64 | G-protein-coupled receptor 64 | 1.15 | 3.27 | 0.26 | 0.62 |

| Gdap10 | Ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated-protein 10 | 11.88 | 31.82 | 15.75 | 13.28 |

| Slc2a5 | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 5 | 5.58 | 17.69 | 5.09 | 2.83 |

| Per3 | Period homolog 3 (Drosophila) | 1.29 | 22.34 | 6.81 | 4.00 |

| 4631416L12Rik | Riken cDNA 4631416L12 gene | 35.00 | 113.73 | 45.38 | 39.85 |

| 3010003L21Rik | Riken cDNA 3010003L21 gene | 1.67 | 5.72 | 2.11 | 1.85 |

| Rev-erbβ | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 | 1.74 | 10.86 | 1.62 | 1.18 |

| Nrg4 | Neuregulin 4 | 2.55 | 9.18 | 1.21 | 0.74 |

| Ibrdc3 | IBR domain containing 3 | 3.34 | 8.98 | 2.27 | 3.76 |

| Dbp | D-site albumin promoter binding protein | 4.25 | 249.19 | 12.37 | 7.80 |

| Gys2 | Glycogen synthase 2 | 266.31 | 851.86 | 206.32 | 275.26 |

| Cxcl1 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 | 8.89 | 21.82 | 7.20 | 4.28 |

| Homer2 | Homer homolog 2 (Drosophila) | 49.03 | 99.04 | 36.85 | 40.74 |

| Klf13 | Kruppel-like factor 13 | 2.42 | 20.41 | 1.56 | 9.56 |

| Cabyr | Calcium-binding tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation regulated (fibrousheathin 2) | 2.33 | 20.03 | 4.11 | 8.88 |

| Spry2 | Sprouty homolog 2 (Drosophila) | 1.53 | 3.19 | 1.41 | 1.35 |

| 6430710M23Rik | Riken cDNA 6430710M23 gene | 2.28 | 5.06 | 1.64 | 2.29 |

| Coq10b | Coenzyme Q10 homolog B (S. cerevisiae) | 5.66 | 14.73 | 5.96 | 6.08 |

| Ccrn4l | CCR4 carbon catabolite repression 4-like (S. cerevisiae) | 9.83 | 33.54 | 8.00 | 6.50 |

These genes were altered by at least 2.0-fold compared to ZT0 to ZT12 in the livers of wild-type mice and are decreased by at least 2.0-fold at both ZT0 and ZT12 of Bmal1−/− mice compared to the ZT12 of the wild type. The values indicate signal intensities after global normalization from microarrays.

BMAL1 target genes are related to metabolism.

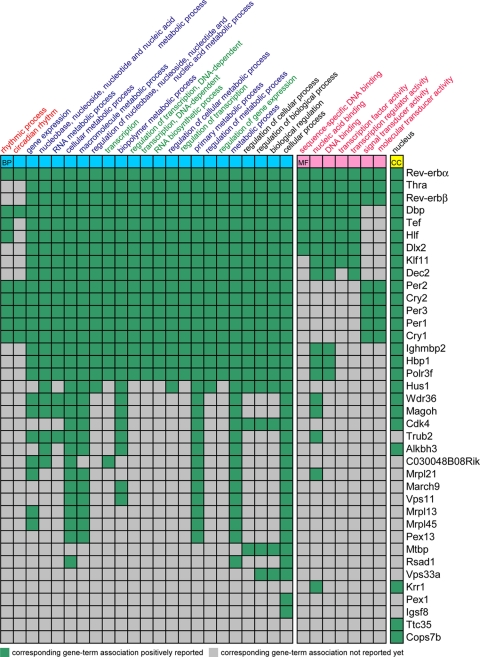

To establish a systematic classification of the BMAL1 target genes identified by the ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq approaches, we analyzed gene ontology by DAVID Bioinformatics Database for associations with particular gene ontology terms (Fig. 6; see Table S4 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). The outcome of this analysis revealed that BMAL1 target genes are related to rhythmic processes, metabolic pathways and transcription as a biological process, DNA binding or transcription as a molecular function, and nucleus as a cellular component. Furthermore, the expressions of key genes related to glucose metabolism such as Glut2, Por, Pck1 and Gys2 were greatly diminished in the livers of Bmal1−/− mice compared to wild-type mice. Also, genes relevant to drug and cholesterol metabolism (Cyp2a4, Cyp2a5, Cyp4a14, Cyp7a1, and Cyp2c55) were differently expressed in Bmal1−/− mice compared to the wild-type littermates (see Fig. S9 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods), although we could not find these genes in ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq signals. It is therefore possible that these genes related to metabolism are downstream targets of BMAL1.

FIG. 6.

Gene ontology terms from BMAL1-regulating genes. Fifty-three genes identified in ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip results were analyzed by using the DAVID Bioinformatics Database (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) for associations with particular Gene Ontology terms. The result reveals an enrichment of genes related to rhythmic process, metabolic process and transcription. BP (blue), MF (pink), and CC (yellow) indicate the biological process, molecular function, and cellular component, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Circadian regulation is exerted mostly at transcriptional level and is critical for a wide range of physiological and metabolic functions. Deciphering how the circadian clock machinery operates at the genome-wide level is thereby a critical step toward the understanding of cellular physiology. Our systematic analyses by ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq uncovered hundreds of targeted candidates for the core clock transcription factor BMAL1. Importantly, all known CCGs driven by E-boxes were present in our systematic ChIP results, validating our experimental approach.

In order to obtain highly reliable data, we used the combination of two methods to reveal binding sites for BMAL1. We identified eight common BMAL1-binding sites that contain both E-box and CATTGG motifs. Luciferase reporter experiments demonstrated that E-box and/or E-box-like sequences are essential to drive circadian gene expression and that the CATTGG element regulates transcriptional activity for the hDbp promoter. It is recognized that the ChIP-chip approach has some limitations, such as the construction of specific probes and pseudo-signals of hybridization (14), whereas ChIP-seq provides markedly precise locations in a genome-wide analysis. Our results confirm this view since we revealed precise locations of the BMAL1-binding sites in the ChIP-seq analysis. Correlation between ChIP signals and rhythmic expression also supports this view (see Fig. S7 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). Specifically for Per1, Dbp, Rev-erbα, and Tef, these sites were found not only in the proximal promoter region but also within intergenic regions and introns. This result suggests that other genomic sequences of these genes, besides the proximal promoter regions, may be involved in driving robust circadian oscillation. This is not necessarily the case for all CCGs. In the case of Per2, the proximal region is solely sufficient in accordance with previous studies (1, 24, 55). In addition, robustness of oscillation directly correlates with the strength of BMAL1 binding, suggesting that oscillation is generated by occupancy of BMAL1 (see Fig. S5 to S7 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). Interestingly, the detected tags in ChIP-seq for BMAL1 were located at the same region from ChIP-seq of RNA polymerase II and H3K4me3, a histone modification generally associated with transcriptional activation (4). These results suggest that transcriptional factor BMAL1, RNA polymerase II, and a histone methyltransferase responsible for H3K4me3 are recruited in a coordinate manner, confirming the notion that circadian transcription and chromatin modifications are intimately linked (8, 23, 32).

Our analysis identified Gm129, a BMAL1 target whose function is as yet unknown and absent in the database. Expression of Gm129 in the SCN and liver displays a robust circadian rhythm with a profile similar to Per2 and anti-phasic to Bmal1. Our preliminary data show that coexpression of Gm129 results in inhibition of E-box driven transcription. Thus, the protein encoded by the Gm129 might operate in a manner similar to CRY and could thereby participate in the circadian loop. Gm129-null mice will help understanding what role of Gm129 may play in circadian and physiological functions. Other BMAL1-regulated genes with rhythmicities of >0.7 (see Fig. S5 and S6 at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods) possess E-box and E-box-like sequences in their promoters. Further studies will provide valuable information on the physiological roles of these clock-controlled genes.

Many genes that normally show oscillatory expression lost their rhythmicity in the liver of Bmal1−/− mice. Importantly, our ChIP analysis revealed two distinct classes of BMAL1-regulated genes. Genes in the first group, which include Dbp, show a total loss of cyclic transcription in Bmal1−/− mice. Genes in the second group still have substantial and rhythmic expression in Bmal1−/− mice. We concluded that cyclic expression of the genes in the second group defines a set of CCGs in the liver which does not solely utilize the canonical CLOCK/BMAL1 core clock complex. These observations may be related to previous studies implicating cyclic AMP-response element binding protein (CREB) in the coregulation of CCGs. Indeed, CREB has been reported to activate the same group of genes that we identify not to be transcriptionally silenced in the liver of Bmal1−/− mice (56). Furthermore, a similar regulation is seen in the SCN with a light pulse and in the retina of Bmal1−/− mice (28, 39). Therefore, core circadian genes such as Per1, Per2, Cry1, and Cry2 appear to be regulated by a combination of BMAL1 with other transcription factors for which many binding elements exist in their promoter regions (18, 24, 42).

Recent studies have revealed intimate links between clock control and cellular metabolism (10, 12, 44, 50). Our results of gene ontology support this view. Previous transcriptome analysis has revealed global changes in metabolic pathways in a circadian manner (26). Furthermore, mice deficient in either Bmal1 or Clock gene display abnormal metabolic activities (34, 45). Our study uncovered additional molecular couplings between circadian and metabolic transcription networks. Moreover, our genome-wide profile can contribute to the discovery of new key genes in metabolic pathways coupled with BMAL1 in a manner similar to what reported for REV-ERBα (19, 54). Genes whose expression was downregulated in Bmal1−/− mice but were not found in the ChIP analyses could be candidates to be downstream from BMAL1. However, further studies are needed in order to provide a comprehensive interpretation of the data. In the liver of Bmal1−/− mice, many genes relevant to glucose and drug metabolism seem to be differently expressed compared to wild-type tissues (see Fig. S9A at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). It has been reported that a large proportion of nuclear receptors (NRs) display circadian expression in key metabolic tissues (53). Importantly, other than Rev-erbs, no other NRs appear to be expressed differently in the livers of Bmal1−/− mice (see Fig. S9B at the URL given in “Antibody” in Materials and Methods). While this could appear surprising, considering the drastic changes in the expression of metabolic genes in the Bmal1−/− livers, one interpretation may be that NR expression is prominently entrained by feeding (6) or that Bmal1−/− mice show robust food anticipatory activity (27). Altogether, our findings indicate that the hierarchical transcriptional system based on the circadian clock coordinates physiological functions in metabolism. In this scenario, the specific contribution of the core clock component BMAL1 appears to be central, although a number of genes commonly thought to be under its control may utilize alternative pathways of regulation. Future genome-wide studies with combinations of antibodies for CLOCK, NPAS2, REV-ERB, and other regulators will provide additional insight into the whole transcriptional network of clock genes and their diverse functions in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technicians of the Takumi laboratory for their valuable assistance. We also acknowledge T. Ishibashi and H. Kimura for their contribution at the initial stages of this project, T. Tamaru and Y. Nakahata for their providing information on the BMAL1 antibody, T. Akagi for WI38 cells, and C. Bradfield for Bmal1 (Mop3) knockout mice.

This study was supported in part by the MEXT, the Sumitomo Foundation, the Takeda Foundation, Sony Corporation, and Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 October 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akashi, M., T. Ichise, T. Mamine, and T. Takumi. 2006. Molecular mechanism of cell-autonomous circadian gene expression of Period2, a crucial regulator of the mammalian circadian clock. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:555-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akashi, M., and T. Takumi. 2005. The orphan nuclear receptor RORα regulates circadian transcription of the mammalian core-clock Bmal1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhtar, R. A., A. B. Reddy, E. S. Maywood, J. D. Clayton, V. M. King, A. G. Smith, T. W. Gant, M. H. Hastings, and C. P. Kyriacou. 2002. Circadian cycling of the mouse liver transcriptome, as revealed by cDNA microarray, is driven by the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Curr. Biol. 12:540-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barski, A., S. Cuddapah, K. Cui, T. Y. Roh, D. E. Schones, Z. Wang, G. Wei, I. Chepelev, and K. Zhao. 2007. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129:823-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunger, M. K., L. D. Wilsbacher, S. M. Moran, C. Clendenin, L. A. Radcliffe, J. B. Hogenesch, M. C. Simon, J. S. Takahashi, and C. A. Bradfield. 2000. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell 103:1009-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canaple, L., J. Rambaud, O. Dkhissi-Benyahya, B. Rayet, N. S. Tan, L. Michalik, F. Delaunay, W. Wahli, and V. Laudet. 2006. Reciprocal regulation of brain and muscle Arnt-like protein 1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha defines a novel positive feedback loop in the rodent liver circadian clock. Mol. Endocrinol. 20:1715-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, X., H. Xu, P. Yuan, F. Fang, M. Huss, V. B. Vega, E. Wong, Y. L. Orlov, W. Zhang, J. Jiang, Y. H. Loh, H. C. Yeo, Z. X. Yeo, V. Narang, K. R. Govindarajan, B. Leong, A. Shahab, Y. Ruan, G. Bourque, W. K. Sung, N. D. Clarke, C. L. Wei, and H. H. Ng. 2008. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell 133:1106-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doi, M., J. Hirayama, and P. Sassone-Corsi. 2006. Circadian regulator CLOCK is a histone acetyltransferase. Cell 125:497-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duffield, G. E., J. D. Best, B. H. Meurers, A. Bittner, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2002. Circadian programs of transcriptional activation, signaling, and protein turnover revealed by microarray analysis of mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 12:551-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckel-Mahan, K., and P. Sassone-Corsi. 2009. Metabolism control by the circadian clock and vice versa. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:462-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gekakis, N., D. Staknis, H. B. Nguyen, F. C. Davis, L. D. Wilsbacher, D. P. King, J. S. Takahashi, and C. J. Weitz. 1998. Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science 280:1564-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green, C. B., J. S. Takahashi, and J. Bass. 2008. The meter of metabolism. Cell 134:728-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hastings, M. H., A. B. Reddy, and E. S. Maywood. 2003. A clockwork web: circadian timing in brain and periphery, in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4:649-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson, D. S., W. Li, D. B. Gordon, A. Bhattacharjee, B. Curry, J. Ghosh, L. Brizuela, J. S. Carroll, M. Brown, P. Flicek, C. M. Koch, I. Dunham, M. Bieda, X. Xu, P. J. Farnham, P. Kapranov, D. A. Nix, T. R. Gingeras, X. Zhang, H. Holster, N. Jiang, R. D. Green, J. S. Song, S. A. McCuine, E. Anton, L. Nguyen, N. D. Trinklein, Z. Ye, K. Ching, D. Hawkins, B. Ren, P. C. Scacheri, J. Rozowsky, A. Karpikov, G. Euskirchen, S. Weissman, M. Gerstein, M. Snyder, A. Yang, Z. Moqtaderi, H. Hirsch, H. P. Shulha, Y. Fu, Z. Weng, K. Struhl, R. M. Myers, J. D. Lieb, and X. S. Liu. 2008. Systematic evaluation of variability in ChIP-chip experiments using predefined DNA targets. Genome Res. 18:393-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, D. S., A. Mortazavi, R. M. Myers, and B. Wold. 2007. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science 316:1497-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson, W. E., W. Li, C. A. Meyer, R. Gottardo, J. S. Carroll, M. Brown, and X. S. Liu. 2006. Model-based analysis of tiling-arrays for ChIP-chip. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12457-12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, T. H., and B. Ren. 2006. Genome-wide analysis of protein-DNA interactions. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 7:81-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumaki, Y., M. Ukai-Tadenuma, K. D. Uno, J. Nishio, K. H. Masumoto, M. Nagano, T. Komori, Y. Shigeyoshi, J. B. Hogenesch, and H. R. Ueda. 2008. Analysis and synthesis of high-amplitude Cis-elements in the mammalian circadian clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:14946-14951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Martelot, G., T. Claudel, D. Gatfield, O. Schaad, B. Kornmann, G. L. Sasso, A. Moschetta, and U. Schibler. 2009. REV-ERBalpha participates in circadian SREBP signaling and bile acid homeostasis. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, A. C., W. G. Lewis, and S. A. Kay. 2007. Mammalian circadian signaling networks and therapeutic targets. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3:630-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell, P. J., and R. Tjian. 1989. Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science 245:371-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakahata, Y., M. Akashi, D. Trcka, A. Yasuda, and T. Takumi. 2006. The in vitro real-time oscillation monitoring system identifies potential entrainment factors for circadian clocks. BMC Mol. Biol. 7:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakahata, Y., B. Grimaldi, S. Sahar, J. Hirayama, and P. Sassone-Corsi. 2007. Signaling to the circadian clock: plasticity by chromatin remodeling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19:230-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakahata, Y., M. Yoshida, A. Takano, H. Soma, T. Yamamoto, A. Yasuda, T. Nakatsu, and T. Takumi. 2008. A direct repeat of E-box-like elements is required for cell-autonomous circadian rhythm of clock genes. BMC Mol. Biol. 9:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakatani, J., K. Tamada, F. Hatanaka, S. Ise, H. Ohta, K. Inoue, S. Tomonaga, Y. Watanabe, Y. J. Chung, R. Banerjee, K. Iwamoto, T. Kato, M. Okazawa, K. Yamauchi, K. Tanda, K. Takao, T. Miyakawa, A. Bradley, and T. Takumi. 2009. Abnormal behavior in a chromosome-engineered mouse model for human 15q11-13 duplication seen in autism. Cell 137:1235-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panda, S., M. P. Antoch, B. H. Miller, A. I. Su, A. B. Schook, M. Straume, P. G. Schultz, S. A. Kay, J. S. Takahashi, and J. B. Hogenesch. 2002. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell 109:307-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pendergast, J. S., W. Nakamura, R. C. Friday, F. Hatanaka, T. Takumi, and S. Yamazaki. 2009. Robust food anticipatory activity in BMAL1-deficient mice. PLoS One 4:e4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porterfield, V. M., H. Piontkivska, and E. M. Mintz. 2007. Identification of novel light-induced genes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. BMC Neurosci. 8:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Preitner, N., F. Damiola, L. Lopez-Molina, J. Zakany, D. Duboule, U. Albrecht, and U. Schibler. 2002. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell 110:251-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ptitsyn, A. A., S. Zvonic, S. A. Conrad, L. K. Scott, R. L. Mynatt, and J. M. Gimble. 2006. Circadian clocks are resounding in peripheral tissues. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2:e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reppert, S. M., and D. R. Weaver. 2002. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 418:935-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ripperger, J. A., and U. Schibler. 2006. Rhythmic CLOCK-BMAL1 binding to multiple E-box motifs drives circadian Dbp transcription and chromatin transitions. Nat. Genet. 38:369-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robertson, G., M. Hirst, M. Bainbridge, M. Bilenky, Y. Zhao, T. Zeng, G. Euskirchen, B. Bernier, R. Varhol, A. Delaney, N. Thiessen, O. L. Griffith, A. He, M. Marra, M. Snyder, and S. Jones. 2007. Genome-wide profiles of STAT1 DNA association using chromatin immunoprecipitation and massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Methods 4:651-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudic, R. D., P. McNamara, A. M. Curtis, R. C. Boston, S. Panda, J. B. Hogenesch, and G. A. Fitzgerald. 2004. BMAL1 and CLOCK, two essential components of the circadian clock, are involved in glucose homeostasis. PLoS Biol. 2:e377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahar, S., and P. Sassone-Corsi. 2009. Metabolism and cancer: the circadian clock connection. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:886-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato, T. K., S. Panda, L. J. Miraglia, T. M. Reyes, R. D. Rudic, P. McNamara, K. A. Naik, G. A. FitzGerald, S. A. Kay, and J. B. Hogenesch. 2004. A functional genomics strategy reveals Rora as a component of the mammalian circadian clock. Neuron 43:527-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schibler, U., and P. Sassone-Corsi. 2002. A web of circadian pacemakers. Cell 111:919-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Storch, K. F., O. Lipan, I. Leykin, N. Viswanathan, F. C. Davis, W. H. Wong, and C. J. Weitz. 2002. Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart. Nature 417:78-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Storch, K. F., C. Paz, J. Signorovitch, E. Raviola, B. Pawlyk, T. Li, and C. J. Weitz. 2007. Intrinsic circadian clock of the mammalian retina: importance for retinal processing of visual information. Cell 130:730-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi, J. S., H. K. Hong, C. H. Ko, and E. L. McDearmon. 2008. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9:764-775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamaru, T., Y. Isojima, G. T. van der Horst, K. Takei, K. Nagai, and K. Takamatsu. 2003. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and phosphorylation of BMAL1 are regulated by circadian clock in cultured fibroblasts. Genes Cells 8:973-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Travnickova-Bendova, Z., N. Cermakian, S. M. Reppert, and P. Sassone-Corsi. 2002. Bimodal regulation of mPeriod promoters by CREB-dependent signaling and CLOCK/BMAL1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7728-7733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuchihara, K., Y. Suzuki, H. Wakaguri, T. Irie, K. Tanimoto, S. Hashimoto, K. Matsushima, J. Mizushima-Sugano, R. Yamashita, K. Nakai, D. Bentley, H. Esumi, and S. Sugano. 2009. Massive transcriptional start site analysis of human genes in hypoxia cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:2249-2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tu, B. P., and S. L. McKnight. 2006. Metabolic cycles as an underlying basis of biological oscillations. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:696-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turek, F. W., C. Joshu, A. Kohsaka, E. Lin, G. Ivanova, E. McDearmon, A. Laposky, S. Losee-Olson, A. Easton, D. R. Jensen, R. H. Eckel, J. S. Takahashi, and J. Bass. 2005. Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian Clock mutant mice. Science 308:1043-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ueda, H. R., W. Chen, A. Adachi, H. Wakamatsu, S. Hayashi, T. Takasugi, M. Nagano, K. Nakahama, Y. Suzuki, S. Sugano, M. Iino, Y. Shigeyoshi, and S. Hashimoto. 2002. A transcription factor response element for gene expression during circadian night. Nature 418:534-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ueda, H. R., S. Hayashi, W. Chen, M. Sano, M. Machida, Y. Shigeyoshi, M. Iino, and S. Hashimoto. 2005. System-level identification of transcriptional circuits underlying mammalian circadian clocks. Nat. Genet. 37:187-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe, Y., K. Inoue, A. Okuyama-Yamamoto, N. Nakai, J. Nakatani, K. Nibu, N. Sato, Y. Iiboshi, K. Yusa, G. Kondoh, J. Takeda, T. Terashima, and T. Takumi. 2009. Fezf1 is required for penetration of the basal lamina by olfactory axons to promote olfactory development. J. Comp. Neurol. 515:565-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wendt, K. S., K. Yoshida, T. Itoh, M. Bando, B. Koch, E. Schirghuber, S. Tsutsumi, G. Nagae, K. Ishihara, T. Mishiro, K. Yahata, F. Imamoto, H. Aburatani, M. Nakao, N. Imamoto, K. Maeshima, K. Shirahige, and J. M. Peters. 2008. Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature 451:796-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wijnen, H., and M. W. Young. 2006. Interplay of circadian clocks and metabolic rhythms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40:409-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamada, R., and H. R. Ueda. 2007. Microarrays: statistical methods for circadian rhythms. Methods Mol. Biol. 362:245-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamamoto, T., Y. Nakahata, H. Soma, M. Akashi, T. Mamine, and T. Takumi. 2004. Transcriptional oscillation of canonical clock genes in mouse peripheral tissues. BMC Mol. Biol. 5:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang, X., M. Downes, R. T. Yu, A. L. Bookout, W. He, M. Straume, D. J. Mangelsdorf, and R. M. Evans. 2006. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell 126:801-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yin, L., N. Wu, J. C. Curtin, M. Qatanani, N. R. Szwergold, R. A. Reid, G. M. Waitt, D. J. Parks, K. H. Pearce, G. B. Wisely, and M. A. Lazar. 2007. Rev-erbα, a heme sensor that coordinates metabolic and circadian pathways. Science 318:1786-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoo, S. H., C. H. Ko, P. L. Lowrey, E. D. Buhr, E. J. Song, S. Chang, O. J. Yoo, S. Yamazaki, C. Lee, and J. S. Takahashi. 2005. A noncanonical E-box enhancer drives mouse Period2 circadian oscillations in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:2608-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang, X., D. T. Odom, S. H. Koo, M. D. Conkright, G. Canettieri, J. Best, H. Chen, R. Jenner, E. Herbolsheimer, E. Jacobsen, S. Kadam, J. R. Ecker, B. Emerson, J. B. Hogenesch, T. Unterman, R. A. Young, and M. Montminy. 2005. Genome-wide analysis of cAMP-response element binding protein occupancy, phosphorylation, and target gene activation in human tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:4459-4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]