Abstract

Genome-wide location analysis, also known as ChIP-Chip, combines chromatin immunoprecipitation and DNA microarray analysis to identify protein-DNA interactions that occur in living cells. Protein-DNA interactions are captured in vivo by chemical crosslinking. Cell lysis, DNA fragmentation and immunoaffinity purification of the desired protein will co-purify DNA fragments that are associated with that protein. The enriched DNA population is then labeled, combined with a differentially labeled reference sample and applied to DNA microarrays to detect enriched signals. Various computational and bioinformatic approaches are then applied to normalize the enriched and reference channels, to connect signals to the portions of the genome that are represented on the DNA microarrays, to provide confidence metrics and to generate maps of protein-genome occupancy. Here, we describe the experimental protocols that we use from crosslinking of cells to hybridization of labeled material, together with insights into the aspects of these protocols that influence the results. These protocols require approximately 1 week to complete once sufficient numbers of cells have been obtained, and have been used to produce robust, high-quality ChIP-chip results in many different cell and tissue types.

INTRODUCTION

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) has become a widely used method for studying how proteins interact with the genome. The ChIP technique identifies physical interactions between proteins and DNA that occur within living cells1-3 and ChIP can provide a whole-genome view of protein-DNA interactions when combined with DNA microarray analysis4-14. Our goal here is to share our ChIP-Chip protocol, suggest useful quality-control tests, identify the most likely sources of trouble and suggest solutions to problems with experiments. The protocol presented here has been in use for several years and has been used by many different individuals using a broad range of different mammalian cell types and tissues.

Overview of the ChIP-Chip technique

In a typical experiment (Figure 1), protein-DNA interactions are first captured in vivo by treating cells with a small, reversible crosslinker that is capable of rapidly diffusing into cells. After cell lysis, the DNA is fragmented and protein-DNA complexes can be enriched by immunoaffinity capture of the desired protein. As the DNA is fragmented prior to the capture, the DNA fragments that are most proximal to the binding event are enriched. Often, an aliquot of the input DNA is saved prior to immunoprecipitation for use as a reference sample. The crosslinks for both the enriched and input DNA are then reversed, and the DNA is purified away from RNA and protein components. The enrichment relative to a reference sample can then be measured by one of several techniques, such as PCR, comparative sequencing or DNA microarray analysis. For most DNA microarray experiments, the enriched and reference samples must be amplified first to provide sufficient material. In this protocol, the ends of the DNA are blunted and ligated to small DNA linkers that are subsequently used in priming PCR. This ligation-mediated PCR (LM-PCR) results in expanded pools of the enriched and reference DNA that are then differentially labeled and hybridized to the microarrays. The arrays are washed and then scanned. Various algorithms are then used to normalize the enriched and reference channels, to calculate the degree of enrichment and confidence metrics for each feature, to incorporate the information gained from having multiple probes representing contiguous regions of the genome and to generate maps of protein-genome occupancy.

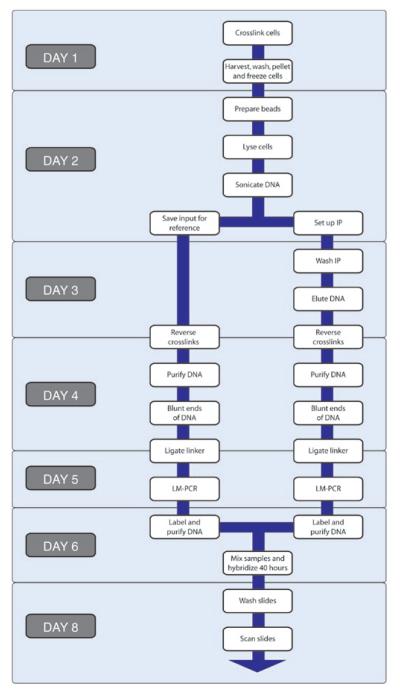

Figure 1.

A sample timeline for the ChIP-Chip protocol. Individual steps are shown in white boxes. Steps that are typically performed on the same day are grouped by day, which is indicated in gray boxes. IP, immunoprecipitation; LM-PCR, ligation-mediated PCR.

Applications of ChIP-Chip

The range of applications for ChIP-Chip is broad but still expanding. The method has recently been used to investigate DNA-binding transcription factors and the networks formed by these factors (reviewed in refs. 15-18), the distributions of chromatin-modifying machinery, histones, histone variants and histone modifications (reviewed in refs. 16, 19), factors involved in DNA replication, DNA repair and DNA methylation (reviewed in refs. 20-22), and the linkage between transcription and nuclear-export machinery23-25. Immunoprecipitation has been coupled with microarrays to identify interactions between proteins and RNA26-30 and ChIP has recently been used to study RNA-binding proteins that become associated with the genome through their interactions with RNA31. We anticipate that many new biological insights will emerge from protein-DNA and protein-RNA interactions that are identified using ChIP.

Limitations of ChIP-Chip

There are several features of ChIP-Chip that currently limit its utility and make it a challenging technique32-34. The primary limitation is the quality of antibodies that are available for a protein of interest. The antibody, ideally, has high avidity and specificity for an epitope that is accessible in the crosslinked chromatin. Because this is not always the case, the investigator must be cautious about interpreting the lack of detection as reflecting the absence of an interaction. A second limitation is that a substantial number of cells (107–108) are generally needed to obtain a robust result. With current methods, using fewer cells can reduce signals, leading to an underestimation of protein-DNA interactions. High-quality, whole-genome DNA microarray platforms are expensive. As array manufacturers continue to make improvements in designs and manufacturing, more cost-effective experiments will be possible. Finally, the experimental process is long and can be challenging to troubleshoot.

Experimental design

Background

The sections below describe several issues that we have found to be critical to consider in the early stages of planning and designing ChIP-Chip experiments.

Antibodies

ChIP-Chip is highly dependent on the antibody used for the immunoprecipitation. As individual antibodies can perform differently in the ChIP assay, it is helpful to screen a wide variety of available antibodies before launching a full-scale ChIP-Chip experiment. We generally start with antibodies, for which there is previous evidence for use in ChIP, or we use a variety of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies from several sources.

The most reliable way to test the antibodies is to use them in small-scale ChIPs and to test for enrichment at a gene-specific level, although this approach depends entirely on the number of known binding sites, the strength of the evidence for the binding event and the comparability with your specific cell type, growth conditions and treatments. For small-scale ChIPs, we prepare material as described below, but instead of using all the material for a single reaction, we will split it into five to ten aliquots and use each aliquot in an immunoprecipitation. This lower amount of material seems adequate for gene-specific analysis, but does not usually work for microarray analysis. If no binding sites are known, it is much more difficult to screen for a useful antibody. Western blot analysis may be informative but is unreliable, as the antibody may recognize the denatured protein in a western blot but may still fail to recognize the native form in vivo.

If there are no antibodies for a specific protein, it is possible to use epitope-tagged versions of proteins, provided the tagged version does not radically affect protein function. We have used myc, TAP and FLAG epitope-tagged versions of various proteins with success.

Reference samples

Chromatin immunoprecipitation is an enrichment relative to a reference and not an absolute measurement, thus the choice of reference sample can be an important element of experimental design. Although it is most common to use unenriched, genomic DNA as the reference, it is sometimes more useful to hybridize an immunoprecipitation of one factor against an immunoprecipitation of a second factor to capture subtle effects. For instance, this approach can be useful when studying histone modifications. An immunoprecipitation against a core histone sub-unit is used as the reference to normalize the signal of the modification against the amount of histone. This can help to determine whether a perceived gain or loss of the modification is due to actual changes in modification or due to changes in histone density.

Replicates

ChIP-Chip, like many other forms of genome-wide analysis, requires the use of replicate samples to account for experimental noise that is inherent to high-throughput approaches and biological complexity due to the many factors influencing protein and nucleic-acid interactions. In particular, biological replicates (independently grown and treated pools of cells or tissue) or replicates with different antibodies against the same factor are valuable. The number of replicates needed depends on the noise that is inherent in the platform and the type of analysis to be performed, but triplicate experiments are preferred and duplicate experiments should be considered to be the minimum requirement whenever feasible.

Experimental controls

The use of a positive control and negative control for the experiment can be useful, both for trouble-shooting and for calibrating the analysis. The positive control should be a high-quality antibody against a protein that is likely to be present in any cell type. For example, in mammalian cells, we regularly use antibodies against the ubiquitous cell-cycle regulator E2F4. The most common negative control is an immunoprecipitation using a non-specific antibody that matches the isotype of the experimental antibody.

Choice of arrays

There are a number of options available for array hybridization, including self-printed oligonucleotide or PCR amplicon arrays, and commercial arrays and services. The choice of array platform ultimately depends on the need to balance performance, ease of use, resolution, cost of arrays and investment in equipment, and will vary from lab to lab. Due to the variety of options, a fully detailed protocol for our specific hybridization, washing, scanning and analysis steps is unlikely to be generally useful. However, we have included the relevant details for hybridization and washing and offer general guidelines that we try to follow for scanning and data analysis. This protocol was developed based on our work with both self-printed PCR amplicon arrays and commercially available oligonucleotide arrays, and reflects our most recent experience with oligonucleotide arrays13,14,35,36. A number of useful ChIP-Chip protocols have been published that describe protocols similar to this one, but which cover more specific aspects of dealing with different array platforms37–44.

Normalization controls on the array

As ChIP measures enrichment in one sample compared with another, it is essential to define an appropriate baseline for a particular experiment — one that reflects the signal from the background of all sequences from the whole genome and reflects lack of enrichment in the immunoprecipitation. This requirement can affect the sets of controls that are needed on the array. When there are a small number of features expected to show enrichment, the enrichment ratios of the majority of features can serve to represent the baseline level; the large size of this latter set strengthens the statistical significance of the enrichment. In other situations, for example, when examining RNA polymerase II binding at promoter regions using arrays focused only on promoter regions, we found that it was more difficult to determine the baseline enrichment that represented ‘no binding’. RNA polymerase II bound at a relatively high fraction of probes, making it more difficult to distinguish bound and unbound probes with as high a degree of statistical signifi-cance. In these cases, we found it useful to have a set of control probes designed against ‘gene deserts’, genomic regions that are devoid of known open reading frames and for which there is no evidence of noncoding transcripts. We assumed that these control probes would be generally unenriched for RNA polymerase II and could therefore serve as a normalization baseline. Similarly, we use control probes to subtract out a baseline level of non-specific hybridization signal and, for multislide arrays, control probes to normalize between slides.

Data analysis and bioinformatics

The ChIP-Chip analysis generates a large amount of data that requires some investment in statistical, computational and bioinformatics infrastructure.

Statistical analysis is required to account for experimental noise that is inherent to high-throughput approaches, but more importantly, to deal with the biological complexity of protein and nucleic-acid interactions. We expect that a protein of interest will be distributed across many different sites in a single cell in a manner that is dependent on protein concentration, its affinities for each site and other variables such as the presence of proteins that compete for similar sites. As a result, the output of ChIP-Chip is a distribution of enrichment ratios representing DNA or RNA occupancy, as opposed to two distinct sets of ‘bound’ and ‘not bound’. Statistical methods are needed to identify the statistically significant set of enrichment ratios, to provide a measure of confidence at the level of individual probe features and to incorporate data from multiple features to build models for binding that are both sensitive and specific. As there are a wide variety of options for statistical analysis7,12,45–51 and the needs of individual labs will vary, a fully detailed description of our analysis methods is unlikely to be generally useful. However, we have included a basic outline of the approach that we have used in the past.

The volume and complexity of the data from ChIP-Chip analysis may require access to resources that are capable of creating or adapting programming code to manipulate and analyze the data. Even if most of the early steps are handled by a commercially available analysis package, there is almost always a need for additional analyses that need to be customized in some way. The capacity to handle and display the data using common programming languages, such as Visual Basic, MATLAB, Perl, R, Java or Python, is highly useful.

Along these lines, the need to be able to map ChIP-Chip data back to genomic location and genomic features often requires the development of bioinformatics resources, such as access to genome annotation and transcription-factor databases, and the ability to handle and cross-reference genome-wide expression data. Commonly used databases include the UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/); the NCBI databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), particularly RefSeq, Gene and GEO datasets; the EMBL-EBI data-bases (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/services/); GO functional annotation (http://www.geneontology.org/); and TRANSFAC (http://www.gene-regulation.com/pub/databases.html).

Protocol Tips

Background

The sections below describe a few key steps of the protocol for which we have some experience with variables that are particularly critical to the success of the experiment. The steps are presented in order, with those most likely to cause problems being presented first.

Sonication

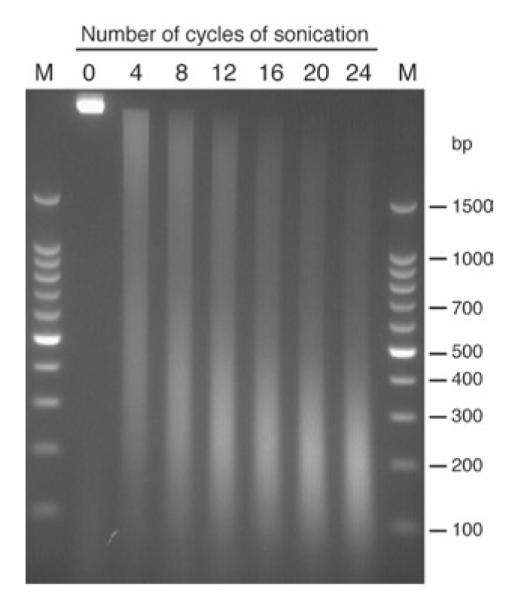

Sonication is the most variable step in the process and will vary greatly depending on cell type, cell culture conditions used, quantity of cells, volume of sonication, degree of crosslinking and specifics of the sonicator being used. As a result, conditions must usually be optimized for each situation. Sonication fulfills two roles, solubilization of chromatin and shearing of chromatin, both of which are essential for successful ChIP analysis. Solubilization is achieved relatively easily. However, the degree of shearing requires more care. Undersonication results in a loss of resolution of binding events. Smaller DNA fragments allow for more precise localization of a specific binding event, as a smaller region of DNA will be pulled down in the immunoprecipitation. We have also found that oversonication must be avoided as it results in more noise in the microarray analysis and difficulty in identifying legitimate targets. As a guide, most protocols suggest sonication until reaching an average fragment size (different protocols suggest a value varying from 350 to 1,000 bp) or until the fragment sizes are within a certain range. Undersonication relative to these kinds of guidelines is easy to identify: the size of the reverse crosslinked, purified DNA fragments will be too large. Oversonication is more difficult to quantify. Most crosslinked material has a physical limit of sonication, and additional sonication past this point will not result in further visible shearing but will affect microarray results. Thus, it is possible that researchers trying to match previously published descriptions that were optimized for different conditions may inadvertently over-sonicate their DNA. As an alternative, we suggest sonication using the lowest power and time settings that result in sheared DNA, of which at least a quarter of the total DNA is sized from 200 to 600 bp in size, with less emphasis on the average size or overall spread of fragment sizes. One way to identify these conditions is to run a small time course of sonications. We will set up a sample of cells, as described below, with a default power setting but with an extended time of sonication. We then remove small aliquots (100 μl out of 3.5 ml of material) at discrete time points. After crosslink reversal and purification, as described in the protocol below, the DNA can be run on a 2% agarose gel to estimate the degree of sonication. A sample sonication time course is shown in Figure 2.

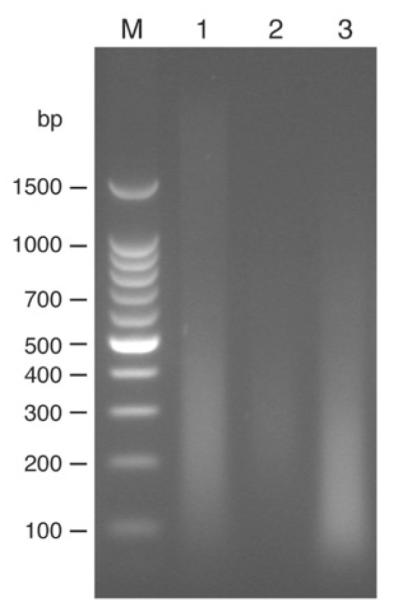

Figure 2.

Results of varying degrees of sonication on fragment size. A total of 2 × 108 crosslinked Jurkat cells were sonicated using the following conditions: Misonix 3000 sonicator with microtip; power 7; 24 cycles (30 s sonication, 90 s rest). Samples were removed at various times, crosslinks were reversed and DNA-purified, and run on a 2% agarose gel. Lanes with molecular weights are labeled M and lanes with sonicated material are labeled with the number of cycles of sonication. Sizes of molecular-mass markers are indicated. Twelve cycles of sonication provide a good degree of sonication. Four cycles of sonication results in undersonicated DNA. Note that sonication beyond 16 cycles results in little change in fragment size and is likely to result in oversonicated material.

Immunoprecipitation conditions

Antibody performance can be optimized by adjusting a number of variables, but we find that the simplest, most effective adjustment has been modifying the amount of salt in the immunoprecipitation. If gene-specific or microarray analysis indicates that antibody performance is poor (two-fold enrichment or less), but a positive control experiment indicates that the protocol is working well, it may be useful to perform a set of small-scale immunoprecipitations over a range of salt concentrations (typically starting with 0, 50, 100 and 250 mM sodium chloride). Prepare input DNA as described below but use only one-fifth to one-tenth of the material in an immunoprecipitation. This small-scale immunoprecipitation usually suffices for gene-specific analysis, but does not usually work for microarray analysis. If there is previous evidence indicating specific salt conditions that are optimal for a particular antibody, we will supplement the lysate with additional sodium chloride to approximate those conditions.

Washing

Following ChIP, it is possible to overwash the beads. This usually results in noise in the microarray analysis. In general, this occurs due to extensive wash times rather than too many washes. Five washes (as presented below) are adequate for most antibodies. If signal:noise ratios are low, increasing the number of washes (as high as 8) may help, although if you suspect low anti-body affinity, a lower number of washes (as few as 3) may be more appropriate.

Crosslinking

In practice, we have found that the crosslinking times and formaldehyde concentrations provided in this protocol are generally applicable and have been used successfully with a variety of proteins in human, mouse, yeast, fruit fly and zebra-fish model systems. But crosslinking times could theoretically be optimized for each protein. Insufficient crosslinking can result in the inability to capture protein-DNA contacts. Over-crosslinking can actually denature the protein of interest or cause over-aggregation, thus obscuring the epitope. Unfortunately, these problems are sometimes difficult to diagnose as the primary readout is the failure to detect enrichment, which could also result in problems at any number of other steps. One other sign would be unusual ease or difficulty in obtaining a range of sonicated material when testing a range of sonication conditions.

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

1 M HEPES-KOH, pKa 7.55 (Invitrogen/Gibco; Cat. no.: 15630-080)

5 M NaCl (Sigma S-5150)

500 mM EDTA (Invitrogen/Gibco; Cat. no: 15575-038)

500 mM EGTA (Sigma, Cat no: E3889)

37% formaldehyde (J.T. Baker; Cat. no: 2106-01)

CAUTION Formaldehyde is flammable; highly toxic by inhalation, contact with skin or if swallowed; causes burns; and is potentially carcinogenic. Formaldehyde should be used with appropriate safety measures, such as protective gloves, glasses and clothing, and adequate ventilation. Formaldehyde waste should be disposed of according to regulations for hazardous waste.

CAUTION Formaldehyde is flammable; highly toxic by inhalation, contact with skin or if swallowed; causes burns; and is potentially carcinogenic. Formaldehyde should be used with appropriate safety measures, such as protective gloves, glasses and clothing, and adequate ventilation. Formaldehyde waste should be disposed of according to regulations for hazardous waste.2.5 M glycine (Sigma; Cat. no: G8790)

10× Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Invitrogen/Gibco; Cat. no.: 14200-075)

Dynabeads (Dynal)

CRITICAL Although it is possible to use other types of beads for the immunoprecipitation, we find that Dynabeads give us very low background and are easy to use. We use Dynabeads that come pre-coated with secondary antibody (e.g., PanMouse IgG, which is a monoclonal human anti-mouse IgG) or pre-coated with protein G. The exact type of bead used will depend on the primary antibody being used)

CRITICAL Although it is possible to use other types of beads for the immunoprecipitation, we find that Dynabeads give us very low background and are easy to use. We use Dynabeads that come pre-coated with secondary antibody (e.g., PanMouse IgG, which is a monoclonal human anti-mouse IgG) or pre-coated with protein G. The exact type of bead used will depend on the primary antibody being used)Block Solution: 1× PBS, 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma; Cat. no: A7906)

CRITICAL Should be made fresh and kept cold.

CRITICAL Should be made fresh and kept cold.Primary antibody of choice

25× solution Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail: 1 tablet dissolved in 2 ml of double distilled water (can store up to 12 weeks at −20 °C) (Roche; Cat. no.: 1 697 498)

50% glycerol (Sigma; Cat. no.: G5516)

10% Igepal CA-360 (Sigma; Cat. no.: I8896)

10% Triton X-100 (Sigma; Cat. no.: T8787)

1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 (Invitrogen/Gibco; Cat. no.: 15568-025)

5% Na-Deoxycholate (Sigma; Cat. no.: D5760)

5% N-lauroylsarcosine (Fluka; Cat. no.: 61743)

CRITICAL An ultrapure version of this reagent is not required for lysis steps, but is required for hybridizations. Lower grades can leave fluorescent residue on slides.

CRITICAL An ultrapure version of this reagent is not required for lysis steps, but is required for hybridizations. Lower grades can leave fluorescent residue on slides.5 M LiCl (Sigma; Cat. no.: L7026)

10% SDS (Invitrogen/Gibco; Cat. no.: 15553-035)

10 mg ml−1 RNAseA (Sigma; Cat. no.: R6513)

Proteinase K solution (Invitrogen; Cat. no.: 25530-049)

-

Phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (Fluka; Cat. no.: 77617)

CRITICAL If this solution is old or is at low pH, there will be degradation of DNA.

CRITICAL If this solution is old or is at low pH, there will be degradation of DNA.  CAUTION Phenol is toxic when in contact with skin or if swallowed; causes burns; and is irritating to eyes, the respiratory system and skin. Chloroform is harmful by inhalation or if swallowed; is irritating to skin; and is potentially carcinogenic. Isoamyl alcohol is flammable; and is irritating to eyes, the respiratory system and skin. The phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol should be used with appropriate safety measures, such as protective gloves, glasses and clothing, and adequate ventilation.

CAUTION Phenol is toxic when in contact with skin or if swallowed; causes burns; and is irritating to eyes, the respiratory system and skin. Chloroform is harmful by inhalation or if swallowed; is irritating to skin; and is potentially carcinogenic. Isoamyl alcohol is flammable; and is irritating to eyes, the respiratory system and skin. The phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol should be used with appropriate safety measures, such as protective gloves, glasses and clothing, and adequate ventilation.The phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol waste should be disposed of according to regulations for hazardous waste.

20 mg ml−1 glycogen (Roche; Cat. no.: 901 393)

100% ethanol (Aaper)

80% ethanol (diluted from 100% ethanol)

T4 DNA polymerase, 3 U μl−1 (New England Biolabs; Cat. no.: M0203S)

10× NE Buffer 2 (supplied with T4 DNA Polymerase)

1 μg μl−1 BSA (diluted from 10 mg ml−1 stock supplied with T4 DNA Polymerase)

2.5 mM dNTP mix (2.5 mM each dNTP) (GE Healthcare Life Sciences; Cat. no.: 27-2035-03)

3 M sodium acetate (Sigma; Cat. no.: S-7899)

T4 DNA ligase, 400 U μl (New England Biolabs; Cat. no.: M0202S)

5× T4 DNA Ligase buffer (Invitrogen; Cat. no.: 46300-018)

40 μM solution oligo oJW102 (MWG Biotech; 5′-GCGGTGACCCGGGAGATCTGAATTC-3′)

40 μM solution oligo oJW103 (MWG Biotech; 5′-GAATTCAGATC-3′)

15 μM Linker (see REAGENT SETUP)

10× ThermoPol buffer (New England Biolabs; Cat. no.: B9004S)

Double-distilled water

AmpliTaq polymerase (Applied Biosystems)

7.5 M ammonium acetate (Sigma; Cat. no.: A2706)

BioPrime Array CGH Genomic Labeling System (Invitrogen; Cat. no.: 18095-011; includes Labeling Module and Purification Module)

CRITICAL We have experimented with other purification methods, but have found that these kits gave us the best yield while efficiently removing smaller DNA products. We have found that these small DNA products increased the background noise at lower signal intensity levels on our arrays.

CRITICAL We have experimented with other purification methods, but have found that these kits gave us the best yield while efficiently removing smaller DNA products. We have found that these small DNA products increased the background noise at lower signal intensity levels on our arrays.1 mM Cy3-dUTP (PerkinElmer/NEN; Cat. no.: NEL578)

1 mM Cy5-dUTP (PerkinElmer/NEN; Cat. no.: NEL579)

Formaldehyde Solution (see REAGENT SETUP)

Lysis Buffer 1 (see REAGENT SETUP)

Lysis Buffer 2 (see REAGENT SETUP)

Lysis Buffer 3 (see REAGENT SETUP)

Wash Buffer (RIPA) (see REAGENT SETUP)

Elution Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1.0% SDS

TE: 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA

TE + NaCl: 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl (keep cold)

2× Blunting Mix (See Step 44)

CRITICAL Should be made fresh before use.

CRITICAL Should be made fresh before use.2× Ligase Mix (See Step 52)

CRITICAL Should be made fresh before use. Linkers used in this mix should be thawed on ice, used immediately and not re-used.

CRITICAL Should be made fresh before use. Linkers used in this mix should be thawed on ice, used immediately and not re-used.LMPCR Mix A (See Step 58)

LMPCR Mix B (See Step 58)

Label Mix (Nucleotide Mix and Klenow are from Invitrogen labeling kit) (See Step 70)

The following reagents are specific to our hybridization and washing protocol; as different laboratories will select different array platforms, these are intended as a reference: 200 ng μl−1 sheared herring sperm DNA (Promega; Cat. no.: D1815); 8 μg μl−1 yeast tRNA (Invitrogen; Cat. no.: 15401-029); 1 μg μl−1 Cot-1 DNA (Invitrogen; Cat. no.: 15279-011; use species-specific Cot-1 DNA)

10× Control Targets (Agilent; Cat. no.: 5185-5976-P) (Reconstitute per manufacturer’s directions. Used in protocol at 0.1×, not 1× as recommended by manufacturer)

500 mM Na-MES, pH 6.9 (Sigma; Cat. no.: M5287) (Adjust pH with 10 N sodium hydroxide)

CRITICAL MES can go off. As a precaution, make small batches of the stock solution and use within 3 months. Store in the dark at 4 °C.

CRITICAL MES can go off. As a precaution, make small batches of the stock solution and use within 3 months. Store in the dark at 4 °C.100% formamide (Sigma; Cat. no.: F9037)

CAUTION Formamide is harmful by inhalation, in contact with skin or if swallowed; and causes burns. Formamide should be used with appropriate safety measures, such as protective gloves, glasses and clothing, and adequate ventilation. The formamide waste should be disposed of according to regulations.

CAUTION Formamide is harmful by inhalation, in contact with skin or if swallowed; and causes burns. Formamide should be used with appropriate safety measures, such as protective gloves, glasses and clothing, and adequate ventilation. The formamide waste should be disposed of according to regulations.100% acetonitrile (J.T. Baker; Cat. no.: 9017-03)

CAUTION Acetonitrile is highly flammable; and is toxic by inhalation, in contact with skin or if swallowed. Acetonitrile should be used with appropriate safety measures, such as protective gloves, glasses and clothing, and adequate ventilation. The acetonitrile waste should be disposed of according to regulations.

CAUTION Acetonitrile is highly flammable; and is toxic by inhalation, in contact with skin or if swallowed. Acetonitrile should be used with appropriate safety measures, such as protective gloves, glasses and clothing, and adequate ventilation. The acetonitrile waste should be disposed of according to regulations.Hybridization Control Mix (See Step 80)

Hybridization Buffer Master Mix (See Step 82)

CRITICAL Should be made fresh before use.

CRITICAL Should be made fresh before use.20× SSPE (Invitrogen; Cat. no.: 15591-027)

Wash I: 6× SSPE, 0.005% N-lauroylsarcosine

Wash II: 6× SSPE

Wash III (Stabilization and Drying Buffer; Agilent; Cat. no.: 5185-5979)

CAUTION This solution contains acetonitrile, which is flammable and hazardous and should be used in a fume hood.

CAUTION This solution contains acetonitrile, which is flammable and hazardous and should be used in a fume hood.

EQUIPMENT

Cell strainer, 100 μm nylon (if using tissues) (e.g., BD Falcon)

Rotator (e.g., Fisher Hematology/Chemistry Mixer)

Magnetic particle collector (MPC; Dynal)

Sonicator (e.g., Misonix 3000 sonicator equipped with microtip)

Phase lock, heavy, pre-dispensed into 2.0 ml microfuge tubes (Eppendorf) (Although these could be replaced with standard liquid organic solvent extractions, the ease of use factor makes these ideal)

NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (This is highly useful as it allows you to assay DNA concentrations and dye incorporations by using low volumes (1.5 μl) of sample)

Thermal cycler (e.g., MJ Research PTC-225) (For large-scale set-ups, it is useful to have a cycler that can handle 96-well plates)

Swinging bucket centrifuge, variable temperature (e.g., Sorvall Legend RT)

Rocking platform (e.g., Bellco Rocker Platform)

Liquid nitrogen and appropriate container

65 degree oven (e.g., Techne Hybridiser HD-1B) (Ovens or warm rooms are preferred for longer incubations as the evenly applied heat limits condensation forming on tube lids)

REAGENT SETUP

15 μM Linker

Mix 250 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 375 μl of 40 μM oJW102 and 375 μl of 40 μM oJW103. Make 50 or 100 μl aliquots in PCR tubes. Place tubes in thermal cycler. Set up and run the following program: 95 °C for 5 min; 70 °C for 1 min; ramp down to 4 °C (0.4 °C/min); 4 °C Hold. Remove linkers and store at −20 °C.  CRITICAL Linkers must be thawed on ice and used immediately. The linkers are labile and will dissociate, causing low-efficiency ligation. Aliquots of partially used linkers should not be re-frozen and re-used.

CRITICAL Linkers must be thawed on ice and used immediately. The linkers are labile and will dissociate, causing low-efficiency ligation. Aliquots of partially used linkers should not be re-frozen and re-used.

Formaldehyde Solution

Should be made fresh. Consists of 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA and 11% formaldehyde.

Lysis Buffer 1

Add protease inhibitors just before use, filter and keep cold. Consists of 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 0.25% Triton X-100, 1× protease inhibitors

Lysis Buffer 2

Add protease inhibitors just before use, filter and keep cold. Consists of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1× protease inhibitors

Lysis Buffer 3

Add protease inhibitors just before use, filter and keep cold. Consists of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.1% Na-Deoxycholate, 0.5% N-lauroylsarcosine, 1× protease inhibitors

Wash Buffer (RIPA)

Keep cold. Consists of 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pKa 7.55, 500 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1.0% NP-40, 0.7% Na-Deoxycholate

EQUIPMENT SETUP

Sonicator

We most commonly use a Misonix 3000 sonicator with microtip. The settings we typically begin with are power setting 7 (~35 W) and 12 cycles (where each cycle is a 30 s burst of sonication, followed by a 90 s pause). The range of settings will vary based on cell type, cell number, growth conditions and crosslinking. For comparison, the range of settings we have used for specific experiments is: power settings from 6 to 9; cycle number from 8 to 15; burst times of 20 to 30 s and pause times of 60 to 90 s.

Array scanning

As the specifics of scanning depend on the platform chosen and the scanner available, it is less useful to provide a detailed protocol on how to scan arrays using any one specific set-up. However, there are a few guidelines that we have found to be useful for two-color hybridizations. In selecting scanner settings, the primary variable we change is photomultiplier tube (PMT) gain, which adjusts the sensitivity of the PMT that converts photons to a digitized electrical signal for the Cy3 and Cy5 channels.

A higher PMT gain creates a brighter image. We try to select PMT settings for each of the lasers in a two-color scanner that maximize signal intensity from features, without creating excessive background signal from the glass surface. Our current array platform has extremely low background signal, so our main concern is maximizing signal intensity. PMT gains are also set such that the distributions of signal intensities for each channel are similar. In addition, the settings should not result in a large number of signals that exceed, and are therefore thresholded at, the maximum detection range of the scanner. This can result in loss of detection of enrichment for features with high signal intensities.

PROCEDURE

Formaldehyde crosslinking cells  TIMING Day 1, 1–4 h

TIMING Day 1, 1–4 h

-

1| For formaldehyde-crosslinking of cells, three procedures are described that can be used, depending on whether your cells are: adherent to culture apparatus (A); growing in suspension (B); or obtained fresh from tissues (C). The procedure given in (C) has been used with mouse and human tissues. Specifics vary from tissue to tissue, and this extraction procedure will therefore require some optimization — these steps are, therefore, general guidelines for extracting and crosslinking cells from tissues.

CAUTION See REAGENTS for precautions when using formaldehyde.

CAUTION See REAGENTS for precautions when using formaldehyde. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING- For adherent cells:

- Use 5 × 107 − 1 × 108 cells for each immunoprecipitation.

- Add 1/10 volume of fresh 11% Formaldehyde Solution to plates. Swirl briefly.

- Incubate cells with Formaldehyde Solution for 10 min at room temperature.

- Add 1/20 volume of 2.5 M glycine to quench formaldehyde.

- Rinse cells twice with 10 ml of 1× PBS. Harvest cells using silicon scraper.

- Pool cells in 50 ml conical tubes and spin at 700g for 5 min at 4 °C. Discard supernatant and resuspend pellet in 10 ml of 1× PBS per 108 cells with gentle inversion (cells may stick to pipettes at this stage).

- Aliquot 5 × 107 − 1 × 108 cells to individual 15 ml conical tubes and spin at 700g for 5 min at 4 °C. Discard supernatants.

- For suspension cells:

- Use 5 × 107 − 1 × 108 cells for each immunoprecipitation.

- Add 1/10 volume of fresh 11% Formaldehyde Solution to flasks. Swirl briefly.

- Incubate cells with Formaldehyde Solution for 20 min at room temperature.

- Add 1/20 volume of 2.5 M glycine to quench formaldehyde.

- Pool cells in required number of 50 ml conical tubes and spin at 700g for 5 min at 4 °C. Discard supernatant.

- Resuspend cells in 50 ml of 1× PBS with gentle inversion (cells may stick to pipettes at this stage). Spin at 700g for 5 min at 4 °C to pellet cells. Discard supernatant. Repeat once. Resuspend final cell pellet in 10 ml of 1× PBS per 108 cells.

- Aliquot 5 × 107 − 1 × 108 cells to individual 15 ml conical tubes and spin at 700g for 5 min at 4 °C. Discard supernatants.

- For tissues:

- Harvest tissues. For human tissues, this involves an arrangement to obtain transplant-grade tissue that has been released for research and will depend on the tissue. Whenever possible, tissues are crosslinked as close to collection as possible and then shipped. If not possible, tissues are shipped on ice, allowed to recover briefly and then crosslinked and processed as described below. For mouse tissues, this entails euthanizing the mice and then immediately harvesting the desired tissues.

- Mince tissues very finely. Transfer to 50 ml tube and add 2× volume of 1× PBS. Add 1/10 volume of fresh 11% Formaldehyde Solution.

- Incubate cells with Formaldehyde Solution for 10 min at room temperature. Swirl tubes occasionally. Add 1/20 volume of 2.5 M glycine to quench formaldehyde. Immediately place cells on ice.

- Homogenize cells. We typically use douncing or hand-held, mechanical homogenizers. Pass material through a 100-μm nylon cell strainer.

- Pool cells in required number of 50 ml conical tubes and spin at 1,100g for 5 min at 4 °C. Discard supernatant.

- Resuspend cells in 50 ml 1× PBS with gentle inversion (cells may stick to pipettes at this stage). Spin at 1,100g for 5 min at 4 °C to pellet cells. Discard supernatant. Resuspend final cell pellet in 10 ml of 1× PBS per 108 cells.

- Aliquot 5 × 107 − 1 × 108 cells to individual 15 ml conical tubes and spin at 1,350g for 5 min at 4 °C. Discard supernatants.

-

2| Flash-freeze cells in liquid nitrogen and store pellets at −80 °C.

PAUSE POINT Once cells are crosslinked, they may be stored frozen at −80 °C indefinitely.

PAUSE POINT Once cells are crosslinked, they may be stored frozen at −80 °C indefinitely.

Preparing magnetic beads  TIMING Day 2, 7–8 h

TIMING Day 2, 7–8 h

-

3| Add 100 μl of Dynal beads to a 1.5 ml microfuge tube. Set up 1 tube of beads per immunoprecipitation. Add 1 ml Block Solution.

CRITICAL STEP Steps 3–9 are all performed at 4 °C.

CRITICAL STEP Steps 3–9 are all performed at 4 °C. 4| Collect beads using Dynal MPC. Place tubes in rack. Allow beads to collect on side of tube. This should take approximately 15 s. Invert rack once or twice to help collect all beads. Remove supernatant with aspirator or pipettor.

5| Add 1.5 ml Block Solution and gently resuspend beads. This can be done by removing the tubes from the rack and inverting the tubes 10–20 times until the beads are evenly resuspended or by removing the magnetic strip from the rack and inverting the rack, with the tubes still in place — either 10–20 times or until the beads are evenly resuspended. Collect beads as above (Step 4). Remove supernatant with aspirator or pipettor.

6| Wash beads in 1.5 ml Block Solution, as in Step 5, one more time.

-

7| Resuspend beads in 250 μl Block Solution and add 10 μg of antibody. Incubate at 4 °C for a minimum of 6 h, or overnight, on a rotator.

PAUSE POINT This step can be extended to overnight at 4 °C. If so, beads should be prepared starting on Day 1.

PAUSE POINT This step can be extended to overnight at 4 °C. If so, beads should be prepared starting on Day 1. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 8| Wash beads three times in 1 ml Block Solution, as described in Step 5.

9| Resuspend each aliquot of beads in 100 μl Block Solution.

Cell sonication  TIMING Day 2, 2 h

TIMING Day 2, 2 h

10| Remove frozen cell pellets from −80 °C and resuspend each pellet of ~108 cells in 10 ml of Lysis Buffer 1. Rock at 4 °C on platform rocker for 10 min.

11| Spin at 1,350g for 5 min at 4 °C in a table-top centrifuge. Discard supernatant.

12| Resuspend each pellet in 10 ml of Lysis Buffer 2. Rock gently at room temperature for 10 min.

13| Pellet nuclei in table-top centrifuge by spinning at 1,350g for 5 min at 4 °C. Discard supernatant.

14| Resuspend each pellet in each tube in 3.5 ml Lysis Buffer 3. Transfer cells to tubes for sonication. We currently prefer to use the bottom half of a standard polypropylene, 15 ml conical tube for sonication. We cut the tube into two pieces at the 7 ml mark and discard the upper half. Tubes can be covered with parafilm while setting up. You may also wish to save a 50 μl aliquot for use as a pre-sonication control.

-

15| Using a clamp, position tube so the sonicator probe sits approximately 0.5–1.0 cm above the bottom of the tube. Take care that the probe is centered and does not contact the sides of the tube.

CRITICAL STEP Probe positioning can affect whether the solution foams or not during sonication. Typically, foaming indicates that the sonicated DNA will be poorly sheared.

CRITICAL STEP Probe positioning can affect whether the solution foams or not during sonication. Typically, foaming indicates that the sonicated DNA will be poorly sheared. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 16| Immerse tube in an ice-water bath. This is most easily done by keeping the sonicator probe and tube fixed, placing the bath on a height-adjustable platform and raising it into position.

-

17| Sonicate suspension. Samples should be kept in an ice-water bath during sonication. To decrease foaming, initially set output power to 4 and increase manually to final power during first burst.

CRITICAL STEP If there is significant foaming, we recommend removing all bubbles by centrifugation at 20,000g followed by gentle resuspension of all material, leaving no foam bubbles.

CRITICAL STEP If there is significant foaming, we recommend removing all bubbles by centrifugation at 20,000g followed by gentle resuspension of all material, leaving no foam bubbles. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 18| Add 1/10 volume of 10% Triton X-100 to sonicated lysate. Split into two 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes. Spin at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet debris.

-

19| Combine supernatants from the two 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes in a new 15 ml conical tube for immunoprecipitation.

CRITICAL STEP From here on, keep lysates on ice.

CRITICAL STEP From here on, keep lysates on ice. -

20| Save 50 μl of cell lysate from each sample as input DNA. Store at −20 °C. At least one input DNA aliquot should be kept per batch of sonicated lysate. Note that the effects of the sonication and the resulting distribution of fragment sizes can only be checked at Step 42 after crosslink reversal and purification of DNA.

PAUSE POINT Lysates can be frozen at −80 °C and used the next day.

PAUSE POINT Lysates can be frozen at −80 °C and used the next day.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation  TIMING Day 2, 15 min and overnight incubation

TIMING Day 2, 15 min and overnight incubation

-

21| Add 100 μl antibody/magnetic bead mix from Step 9 to cell lysates from Step 19. Incubate overnight on rotator at 4 °C.

CRITICAL STEP Antibody performance can be affected by the amount of salt in the reaction. If there is previous evidence indicating specific salt conditions that are optimal for a particular antibody, we will supplement the lysate with additional sodium chloride to approximate those conditions. In this case, the salt concentrations of wash buffers used in Steps 25–26 should also be adjusted.

CRITICAL STEP Antibody performance can be affected by the amount of salt in the reaction. If there is previous evidence indicating specific salt conditions that are optimal for a particular antibody, we will supplement the lysate with additional sodium chloride to approximate those conditions. In this case, the salt concentrations of wash buffers used in Steps 25–26 should also be adjusted. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING

Wash  TIMING Day 3, 2 h

TIMING Day 3, 2 h

-

22| Set up 1.5 ml microfuge tubes on ice, one tube for each immunoprecipitation. Transfer half of each immunoprecipitation from the 15 ml conical tube to its assigned microfuge tube.

CRITICAL STEP All wash steps are performed at 4 °C. Buffers should be kept cold.

CRITICAL STEP All wash steps are performed at 4 °C. Buffers should be kept cold. 23| Collect beads using Dynal MPC. Place tubes in rack. Allow beads to collect on side of tube. This should take approximately 15 s. Invert rack once or twice to help collect all beads. Remove supernatant with aspirator or pipettor, changing tips between samples.

24| Add second half of immunoprecipitation to tube. Let tubes sit again in magnetic stand to collect the beads. Remove supernatant with aspirator or pipettor, changing tips between samples.

-

25| Add 1 ml Wash Buffer (RIPA) to each tube and gently resuspend beads. This can be done by removing the tubes from the rack and inverting the tubes 10–20 times or by removing the magnetic strip from the rack and inverting the rack, with tubes still in place — 10–20 times or until the beads are evenly resuspended. Collect beads. Remove supernatant by aspirator or pipettor. Repeat this wash four more times, changing tips between washes.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 26| Wash once with 1 ml TE + 50 mM NaCl.

27| Spin at 960g for 3 min at 4 °C and remove any residual TE buffer.

Elution  TIMING Day 3, 30–45 min

TIMING Day 3, 30–45 min

28| Add 210 μl of Elution Buffer and elute material from beads by incubating tubes in a 65 °C water bath for 15 min. Vortex briefly every 2 min. This incubation can be extended as long as 30 min, which can help improve recovery of the eluate.

29| Spin down beads at 16,000g for 1 min at room temperature.

-

30| Remove 200 μl of supernatant and transfer to new tube.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −20 °C and stored overnight.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −20 °C and stored overnight.

Crosslink reversal  TIMING Day 3, 6 h or overnight

TIMING Day 3, 6 h or overnight

-

31| Reverse crosslink the immunoprecipitation DNA from Step 30 by incubating at 65 °C for a minimum of 6 h. This incubation is usually done in an oven so that the tube is heated evenly and there is less condensation formed.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

32| Thaw 50 μl of input DNA reserved after sonication (Step 20), add 150 μl (3 volumes) of elution buffer and mix. Reverse crosslink this input DNA by incubating at 65 °C as in Step 31. From this point, every tube of immunoprecipitation or input DNA is considered to be a separate tube or sample for later processing steps.

PAUSE POINT If the wash was performed early in the day, the crosslink reversal can be stopped after a minimum of 6 h and the material can be frozen at −20 °C and stored overnight. If the wash was performed later in the day, the crosslink reversal can be extended up to 15 h and performed overnight with little effect on the reaction.

PAUSE POINT If the wash was performed early in the day, the crosslink reversal can be stopped after a minimum of 6 h and the material can be frozen at −20 °C and stored overnight. If the wash was performed later in the day, the crosslink reversal can be extended up to 15 h and performed overnight with little effect on the reaction. CRITICAL STEP Longer times of crosslink reversal (18 h or more) usually result in increased noise in the microarray analysis.

CRITICAL STEP Longer times of crosslink reversal (18 h or more) usually result in increased noise in the microarray analysis. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING

Purification of DNA  TIMING Day 4, 6 h

TIMING Day 4, 6 h

33| Add 200 μl of TE to each tube to dilute SDS in Elution Buffer. We have found that high levels of SDS can inhibit RNAse activity.

-

34| Add 8 μl of 10 mg ml−1 RNaseA (0.2 mg ml−1 final concentration), mix by inverting the tube several times and incubate at 37 °C for 2 h.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −20 °C and stored overnight.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −20 °C and stored overnight. 35| Add 4 μl of 20 mg ml−1 Proteinase K (0.2 μg ml−1 final concentration) and mix by inverting the tube several times and incubate at 55 °C for 2 h.

-

36| Add 400 μl phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (P:C:IA), vortex and separate phases with 2 ml Heavy Phaselock tube (follow instructions provided by Eppendorf).

CRITICAL STEP If the P:C:IA solution is old or is at low pH, there will be degradation of DNA, causing noise in the microarray analysis and loss of detection of valid targets.

CRITICAL STEP If the P:C:IA solution is old or is at low pH, there will be degradation of DNA, causing noise in the microarray analysis and loss of detection of valid targets. CAUTION see REAGENTS for precautions when using phenol and chloroform.

CAUTION see REAGENTS for precautions when using phenol and chloroform. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 37| Transfer aqueous layer to new centrifuge tube containing 16 μl of 5M NaCl (200 mM final concentration) and 1.5 μl of 20 μg μl−1 glycogen (30 μg total).

38| Add 800 μl EtOH. Incubate for 30 min at −20 °C.

39| Spin at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet DNA. Wash pellets by adding 500 μl of 80% EtOH, vortexing to resuspend pellet and spinning again at 20,000g for 5 min at 4 °C.

-

40| Remove any remaining 80% EtOH. Spin the tubes briefly to collect any remaining liquid and remove liquid with a pipetteman, avoiding the pellet. Let tubes air dry until pellets are just dry: pellets should still retain a moist appearance. Resuspend each pellet in 70 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0.

CRITICAL STEP Overdrying of these pellets can make them difficult to resuspend, or liable to flake and peel away from the side of the tube.

CRITICAL STEP Overdrying of these pellets can make them difficult to resuspend, or liable to flake and peel away from the side of the tube. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 41| Save 15 μl of immunoprecipitation sample for future use. This material can be used to perform gene-specific PCR confirmation of microarray results.

-

42| Measure DNA concentration of input DNA with NanoDrop and dilute input DNA to 100 ng μl−1. Run purified input DNA on a 2% agarose gel to check distribution of fragment sizes and digestion of RNA. The immunoprecipitation DNA will usually be too dilute to measure or visualize at this point. If possible, this is a good opportunity to check for enrichment in the immunoprecipitation sample using gene-specific PCR.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −80 °C and stored indefinitely.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −80 °C and stored indefinitely. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING

T4 polymerase blunting of ends  TIMING Day 4, 2 h

TIMING Day 4, 2 h

-

43| Set up 1.5 ml microfuge tubes for each immunoprecipitation and input DNA sample. For each input DNA sample, mix 2 μl (200 ng) input DNA and 53 μl ddH2O in an individual tube. For each immunoprecipitation, aliquot 55 μl into an individual tube.

CRITICAL STEP Steps 43−45 should be performed on ice, unless otherwise stated.

CRITICAL STEP Steps 43−45 should be performed on ice, unless otherwise stated. - 44| Make 2× Blunting Master Mix according to the table below:

Component Amount (per reaction) Final amount/concentration 10× NEB buffer 2 11.0 μl 1× 1 μg μl−1 BSA 5.5 μl 50 μg ml−1 2.5 mM dNTP mix 4.4 μl 100 μ M each dNTP T4 DNA polymerase (3 U μl−1) 0.5 μl 1.5 U ddH2O 33.6 μl TOTAL volume 55.0 μl -

45| Add 55 μl of 2× Blunting Master Mix to all tubes. Incubate for 20 min at 12 °C in a water bath that is set up in a 4 °C cold room.

CRITICAL STEP The reaction should be kept at 12 °C and promptly removed after incubation. Theoretically, the low temperature, short reaction time and high concentrations of nucleotides favor the polymerase activity of the T4 DNA polymerase and not the exonuclease activity, resulting in blunt ends and not 5′ overhangs. If no reliable water bath/cold room set-up exists, set up PCR tubes at Step 43 and use a thermal cycler to incubate reactions at 12 °C. Use of PCR tubes will require transferring the samples to microfuge tubes for Steps 46–47.

CRITICAL STEP The reaction should be kept at 12 °C and promptly removed after incubation. Theoretically, the low temperature, short reaction time and high concentrations of nucleotides favor the polymerase activity of the T4 DNA polymerase and not the exonuclease activity, resulting in blunt ends and not 5′ overhangs. If no reliable water bath/cold room set-up exists, set up PCR tubes at Step 43 and use a thermal cycler to incubate reactions at 12 °C. Use of PCR tubes will require transferring the samples to microfuge tubes for Steps 46–47. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 46| Add 11.5 μl of 3 M sodium acetate and 0.5 μl of 20 μg μl glycogen (10 μg total).

-

47| Add 120 μl P:C:IA, vortex samples and transfer samples to room temperature Phaselock tubes. Extract once (follow instructions provided by Eppendorf).

CRITICAL STEP If the P:C:IA solution is old or is at low pH, there will be degradation of DNA, causing noise in the microarray analysis and loss of detection of valid targets.

CRITICAL STEP If the P:C:IA solution is old or is at low pH, there will be degradation of DNA, causing noise in the microarray analysis and loss of detection of valid targets. CAUTION See REAGENTS for precautions when using phenol and chloroform.

CAUTION See REAGENTS for precautions when using phenol and chloroform. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 48| Transfer aqueous layer to new centrifuge tube containing 250 μl EtOH. Incubate for 30 min at −20 °C.

49| Spin at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet DNA. Wash pellets by adding 500 μl of 80% EtOH, vortexing to resuspend pellet and spinning again at 20,000g for 5 min at 4 °C.

-

50| Remove any remaining 80% EtOH. Spin the tubes briefly to collect any remaining liquid and remove liquid with a pipetteman, avoiding the pellet. Let tubes air dry until pellets are just dry: pellets should still retain a moist appearance.

CRITICAL STEP Overdrying of these pellets can make them difficult to resuspend, or liable to flake and peel away from the side of the tube.

CRITICAL STEP Overdrying of these pellets can make them difficult to resuspend, or liable to flake and peel away from the side of the tube. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

51| Carefully resuspend each pellet in 25 μl H2O with pipetting. Adding the water and then allowing the pellets to sit on ice for some time can help. Chill on ice after resuspending.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −80 °C and stored indefinitely.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −80 °C and stored indefinitely.

Blunt-end ligation  TIMING Day 4, 1 h and overnight incubation; Day 5, 2 h

TIMING Day 4, 1 h and overnight incubation; Day 5, 2 h

-

52| Make 2× Ligase Master Mix according to the table below:

Component Amount (per reaction) Final amount/concentration 5× T4 DNA ligase buffer 10.0 μl 1× 15 μM linker 6.7 μl 2 μM T4 DNA ligase (400 U μl−1) 0.5 μl 200 U ddH2O 7.8 μl TOTAL volume 25.0 μl  CRITICAL STEP Steps 52–57 should be done on ice, unless otherwise stated.

CRITICAL STEP Steps 52–57 should be done on ice, unless otherwise stated. 53| Add 25 μl Ligase Master Mix to 25 μl of sample and incubate for 16 h in a 16 °C water bath.

54| Add 6 μl of 3 M sodium acetate and 130 μl EtOH. Incubate for 30 min at −20 °C.

55| Spin at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet DNA. Wash pellets by adding 500 μl of 80% EtOH, vortexing to resuspend pellet and spinning again at 20,000g for 5 min at 4 °C.

-

56| Remove any remaining 80% EtOH. Spin the tubes briefly to collect any remaining liquid and remove liquid with a pipetteman, avoiding the pellet. Pellet may appear as a translucent smear on the side of the tube. Let tubes air dry until pellets are just dry: pellets should still retain a moist appearance.

CRITICAL STEP Overdrying of these pellets can make them difficult to resuspend, or liable to flake and peel away from the side of the tube.

CRITICAL STEP Overdrying of these pellets can make them difficult to resuspend, or liable to flake and peel away from the side of the tube. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

57| Carefully resuspend each pellet in 25 μl H2O with pipetting. Adding the water and then allowing the pellets to sit on ice for some time can help. Store on ice after resuspending.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −80 °C and stored indefinitely.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −80 °C and stored indefinitely.

Ligation-mediated PCR  TIMING Day 5, 3–6 h

TIMING Day 5, 3–6 h

- 58| Make LMPCR Mix A and LMPCR Mix B according to the tables below. Mixes should be prepared on ice.

LMPCR Mix A Component Amount (per reaction) Final amount/concentration 10× ThermoPol buffer 4.0 μl 1× 2.5 mM dNTP mix 5.0 μl 250 μM each dNTP 40 μM oJW102

oligonucleotide1.25 μl 1 μM ddH2O 4.75 μl TOTAL volume 15.0 μl LMPCR Mix B Component Amount (per reaction) Final amount/concentration 10× ThermoPol buffer 1.0 μl 1× Taq polymerase (5 U μl−1) 0.5 μl 2.5 U ddH2O 8.5 μl TOTAL volume 10.0 μl 59| Add 15 μl of LMPCR Mix A to each 25 μl sample, on ice. Transfer tubes to the thermal cycler.

- 60| If an additional expansion step is required to increase the amount of material for labeling, follow (A) below. If no expansion is required, run the program described in (B).

- Expansion required

- Program the thermocycler as follows:

Cycle Denature Anneal Extend 1 55 °C, 4 min 72 °C, 3 min 2 95 °C, 2 min 3–15 95 °C, 30 s 60 °C, 30 s 72 °C, 1 min - Start program. Midway through the 55 °C step of cycle 1, add 10 μl Mix B to each tube to hot-start reactions. If necessary, pause the program so the tubes remain at 55 °C while adding Mix B.

-

After the 15-cycle program has finished, remove the samples and add 475 μl of double-distilled water. This diluted material can then be used as template for subsequent LMPCR reactions (Steps 58–60 (B)). A total of 5 μl of diluted material should be adequate for a new 50-μl reaction. Adjust the amount of water in the recipes listed above accordingly.

CRITICAL STEP It is strongly recommended that you do not use this expansion until comfortable with the procedure. It is important to first calibrate the number of cycles in the first-round PCR to ensure that 15 cycles of amplification are still in the linear range. We used both real-time PCR and array hybridization of material expanded once with 25 cycles versus material expanded with the 15/25 protocol to ensure that our results were not affected by the first-round expansion.

CRITICAL STEP It is strongly recommended that you do not use this expansion until comfortable with the procedure. It is important to first calibrate the number of cycles in the first-round PCR to ensure that 15 cycles of amplification are still in the linear range. We used both real-time PCR and array hybridization of material expanded once with 25 cycles versus material expanded with the 15/25 protocol to ensure that our results were not affected by the first-round expansion.

- No expansion required

-

If no expansion step is required, program the thermocycler as follows:

Cycle Denature Anneal Extend 1 55 °C, 4 min 72 °C, 3 min 2 95 °C, 2 min 3–27 95 °C, 30 s 60 °C, 30 s 72 °C, 1 min 28 72 °C, 5 min The sample can be kept at 4 °C by adding a HOLD step at the end of the program. - Start program. Midway through the 55 °C step of cycle 1, add 10 μl of Mix B to each tube to hot-start reactions. If necessary, pause the program so the tubes remain at 55 °C while adding Mix B.

-

61| After PCR is completed, transfer reactions to individual 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. Pool samples if appropriate. For each 50 μl of PCR reaction, add 25 μl of 7.5 M ammonium acetate and 225 μl of cold EtOH. Incubate for 30 min at −20 °C.

62| Spin at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet DNA. Wash pellets with 500 μl of 80% EtOH. Wash pellets by adding 500 μl of 80% EtOH, vortexing to resuspend pellet and spinning again at 20,000g for 5 min at 4 °C.

-

63| Dry pellets as described above (Step 56) and resuspend each pellet in 50 μl H2O.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

64| Measure DNA concentration with NanoDrop (use 10-fold dilutions, if necessary) and normalize all samples to 500 ng μl−1. Run a 2% agarose gel to check size of LMPCR products.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −80 °C and stored indefinitely.

PAUSE POINT Material can be frozen at −80 °C and stored indefinitely.

Cy3/Cy5 labeling of IP/WCE material  TIMING Day 6, 6 h

TIMING Day 6, 6 h

65| Preheat thermal cycler to 95 °C.

66| For each labeling reaction, aliquot 2 μl (1 μg) of LMPCR-amplified immunoprecipitated or input DNA into a PCR tube.

67| Add 35 μl of 2.5× random primer solution and 38 μl of double-distilled water. This is a random-primed, Klenow-based extension protocol derived from Invitrogen’s CGH kit. Our protocol varies from the instructions provided by Invitrogen in both reaction volume and reagent concentrations. We perform 20 reactions per ‘30 reaction’ Invitrogen kit. A pair of reactions (one for immunoprecipitation and one for its reference input DNA) yields enough material for 1–2 hybridizations. To scale-up for more arrays, we increase number — not volume — of individual reactions.

68| Vortex samples for 30 s.

69| Place tubes in pre-heated thermal cycler. After 5 min at 95 °C, immediately transfer samples to an ice-water slurry bath for 10 min to flash-cool reagents.

- 70| While reagents are cooling, make up Label Mix. One mix is required for immunoprecipitation samples (usually Cy5). A second mix is required for input DNA samples (usually Cy3). If reagents permit, a dye swap can provide a useful comparison (a second set of replicates where the immunoprecipitate is labeled with Cy3 and the input DNA is labeled with Cy5).

Label Mix: Component Amount (per reaction) Final amount/concentration 10× dUTP Nucleotide mix 8.2 μl 1× Cy5 (or Cy3) 1.5 μl 17 μM Klenow (40 U μl−1) 1.5 μl 60 U ddH2O 1.8 μl TOTAL volume 13.0 μl 71| Vortex samples for 30 s.

72| Add 13 μl of Label Mix to each sample. Pipette up and down multiple times to mix reagents.

-

73| Incubate samples for 3 h at 37 °C.

CRITICAL STEP Keep samples in dark as Cy dyes are sensitive to exposure to light. Other incubation times and conditions have been tried, but we find that these conditions offer the best yield, while limiting the accumulation of smaller DNA fragments (<100 bp) that can contribute to noise in the microarray analysis.

CRITICAL STEP Keep samples in dark as Cy dyes are sensitive to exposure to light. Other incubation times and conditions have been tried, but we find that these conditions offer the best yield, while limiting the accumulation of smaller DNA fragments (<100 bp) that can contribute to noise in the microarray analysis. 74| Add 9 μl stop buffer to each well and mix by pipetting gently.

-

75| Clean up DNA using the DNA purification columns provided with the CGH kit. Follow manufacturer’s instructions.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

76| After eluting labeled DNA from the column into a microfuge tube, spin tubes at 15,000g for 2 min at room temperature to pellet any fine particulates. Carefully transfer supernatants to fresh tubes. Repeat if necessary to ensure that the solution is clear.

CRITICAL STEP It is particularly important to thoroughly remove the particulates at this step. Particulates from the purification column can bind to some slide surfaces, making it difficult, if not impossible, to successfully scan the slide.

CRITICAL STEP It is particularly important to thoroughly remove the particulates at this step. Particulates from the purification column can bind to some slide surfaces, making it difficult, if not impossible, to successfully scan the slide. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

77| Measure DNA concentration and dye incorporation with NanoDrop. Optional: Run a 2% agarose gel to check size of labeling products.

PAUSE POINT If this DNA is going to be used within the next day, it can be stored at −20 °C. If the DNA will be stored for longer, we recommend storing it as a pellet. Precipitate the DNA by adding 25 μl of ammonium acetate and 300 μl of ice-cold EtOH and placing the tubes at −80 °C for 10 min. Spin at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet DNA. Wash pellets with 500 μl of 80% EtOH. Remove excess ethanol. Allow pellets to air-dry briefly and store tubes at −80 °C in a light-proof box or wrapped in aluminum foil.

PAUSE POINT If this DNA is going to be used within the next day, it can be stored at −20 °C. If the DNA will be stored for longer, we recommend storing it as a pellet. Precipitate the DNA by adding 25 μl of ammonium acetate and 300 μl of ice-cold EtOH and placing the tubes at −80 °C for 10 min. Spin at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet DNA. Wash pellets with 500 μl of 80% EtOH. Remove excess ethanol. Allow pellets to air-dry briefly and store tubes at −80 °C in a light-proof box or wrapped in aluminum foil. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING

Array hybridization  TIMING Day 6, 1−2 h, plus 40-h incubation

TIMING Day 6, 1−2 h, plus 40-h incubation

78| For each hybridization, combine 5 μg of the Cy5-labeled immunoprecipitated DNA and 5 μg of the appropriate Cy3-labeled reference DNA. Keep all tubes on ice. The hybridization can be performed with less DNA (we have used as little as 3 μg of each Cy5-labeled and Cy3-labeled), but better signal:noise ratios are seen with larger amounts of DNA. If working with frozen pellets, resuspend each pellet first in 50 μl of double-distilled water and then combine however much you need for the hybridization.

79| For each hybridization, bring the combined DNA up to a total volume of 120 μl. Keep all tubes on ice. If the DNA solutions are dilute, this volume can be extended as high as 170 μl and water can be removed from the hybridization buffer mix as necessary.

- 80| Make Hybridization Control Master Mix.

Hybridization Control Master Mix Component Amount (per reaction) Final amount/concentration Sheared herring sperm DNA

(200 ng μl−1)4.0 μl 1.6 μg ml−1 Yeast tRNA (8 μg μl−1) 5.0 μl 80 μg ml−1 Cot-1 DNA (1.6 μg μl−1) 10.0 μl 20 μg ml−1 Control oligonucleotides (1×) 5.0 μl 0.1× TOTAL volume 24.0 μl - 81| Add 24 μl of Hybridization Control Master Mix to each hybridization. Mix by pipetting gently. Keep all tubes on ice.

Hybridization Buffer Master Mix Component Amount (per reaction) Final amount/concentration ddH2O 50.0 μl 500 mM Na-MES, pH 6.9 50.0 μl 50 mM 5 M NaCl 50.0 μl 500 mM 500 mM EDTA 6.0 μl 6 mM 5 % N-lauroylsarcosine 50.0 μl 0.5% Formamide 150.0 μl 30% TOTAL volume 356.0 μl -

82| Make Hybridization Buffer Master Mix. This solution should be made fresh before use and kept at room temperature.

CAUTION See REAGENTS for precautions when working with formamide.

CAUTION See REAGENTS for precautions when working with formamide. 83| Add 356 μl of Hybridization Buffer Master Mix to each hybridization. Mix by pipetting gently. After mixing, do not return samples to ice. Instead, leave tubes at room temperature until all samples have been processed. Keep all samples protected from light.

84| Heat samples for 3 min in a heat block that has been set to 95 °C. Cover with foil to prevent exposure to light.

85| Transfer tubes to a 40 °C heat block for 15 min. Cover with foil to prevent exposure to light. At this point, start preparing hybridization chambers for assembly, aiming to handle 4−6 slides at a time. If there are more slides than this, samples can sit at this 40 °C step for at least 1 h.

-

86| After 15 min, spin tubes at 14,000g for 45 s to pellet any particulates.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 87| Assemble hybridizations according to manufacturer’s instructions. Use 490 μl of hybridization mix per hybridization.

88| Incubate at 40 °C in rotating oven for 40 h. Ensure free rotation of liquid throughout the chamber. We find the best results are obtained with an incubation time of 38–42 h.

Array washing  TIMING Day 8, 1–2 h

TIMING Day 8, 1–2 h

-

89| Before disassembling hybridization chambers, prepare Wash I (6× SSPE, 0.005% H-lauroylsarcosine) and Wash II (6× SSPE). Filter Wash I and Wash II before use. Place Wash III at 37 °C to dissolve solute. Swirling the bottle of Wash III occasionally will help to dissolve the solute. Allow the solution to cool to room temperature before use.

CAUTION As Wash III is volatile, avoid temperatures that are higher than 45 °C.

CAUTION As Wash III is volatile, avoid temperatures that are higher than 45 °C. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

90| Prepare and wash all glassware and equipment that is required for slide disassembly (follow manufacturer’s instructions) and for washes described in Steps 91–95. We usually use standard glass 10-slide microscope slide racks and dishes.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

91| After hybridization, disassemble hybridization chambers individually following the manufacturer’s instructions. Batches of 4–6 slides are convenient. Slides are placed in slide racks in dishes containing a magnetic stir bar (thin enough to spin freely when slides and slide rack are added) and sufficient Wash I to cover the slides.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

92| Once all slides for this batch are in the dish, place dish on stir plate and gently stir for 5 min at room temperature. On a typical stir plate with settings from 1 to 10, use setting 3 or 4. The surface of the liquid should barely dimple. During this wash, prepare two dishes with 270 ml of Wash II, one with a stir bar.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

93| After the 5-min wash in Wash I, remove rack from Wash I, quickly dip it into a dish containing Wash II and immediately transfer to the second dish containing 270 ml of Wash II and stir bar.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

94| Place this dish on a stir plate and gently stir for 5 min at room temperature. Use stir plate settings as described in Step 92. During this wash, prepare the washes for the next step in the fume hood. Pour 270 ml of 100% acetonitrile (FPLC grade) into a small rectangular dish. Pour 250 ml (one half bottle) of room temperature Wash III into a second, small rectangular dish, add a stir bar and place on a stir plate. Cover both dishes when not in use to prevent evaporation.

CAUTION See REAGENTS for precautions when using acetonitrile.

CAUTION See REAGENTS for precautions when using acetonitrile. TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

95| Turn off stir plate and carry dish containing the slides to the hood. Turn on stir plate in the hood to begin agitating Wash III. Remove rack, quickly dip it into dish containing 100% acetonitrile, and immediately transfer to a final dish containing Wash III and a rotating stir bar.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 96| After 15 s, turn off the stir plate. This allows particulates to settle, and helps prevent them from sticking to your slide as you pull the slides out. Wait another 15 s.

-

97| Slowly and smoothly remove rack and slides from Wash III — it should take approximately 10 s to lift the rack from the solution (the slides should be dry at this point). If you move the rack abruptly as you are removing it, you may create visible lines of Wash III precipitate. If this happens, re-dip the slide momentarily and try to pull it out again.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING -

98| Scan immediately. As fluorescent dyes are sensitive to exposure to atmosphere, it is best to scan slides as soon as possible after washing. Various ozone-scavenging treatments, such as Wash III, extend the life of hybridized slides, but still eventually fail. Slides can be stored in vacuum-sealed bags or a high nitrogen environment for short times (2–5 h) until needed.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING

Array analysis

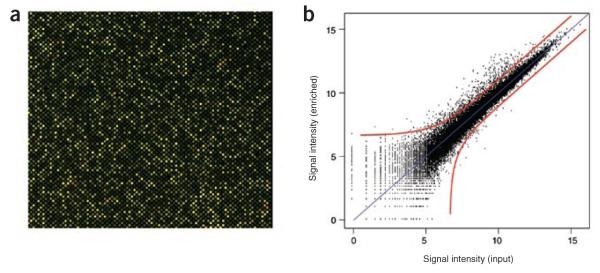

99| As described above, each lab is likely to have specific preferences for analysis of the array. A very brief, general outline is provided here as an example and a more detailed explanation is available in Lee et al.14. Scan slides (we use an Agilent DNA microarray scanner) at wavelengths of 532 nm for input (Cy3) and 635 nm for enriched (Cy5).

100| Use GenePix feature-identification software to automatically identify features and to extract data for fluorescence at each wavelength by calculating the average intensities for all pixels within the feature boundaries.

101| Subtract local background signal for each feature. Normalize the signal intensities of the slide across the entire set of slides using signals from a set of common features that are printed on every slide in the set. Then, subtract the signal intensities from a set of negative controls for hybridization.

102| Median normalize the data from the two channels and generate a log ratio of signal intensities for each feature.

-

103| Process the log ratios using a whole chip error model52, which incorporates signal intensity and background noise to calculate a P-value for the statistical significance of the enrichment ratio that is seen at each feature. We also calculate the P-value for enrichment for sets of three adjacent features and incorporate information about the enrichment at both individual features and sets of features to identify genomic regions that qualify as being bound by the protein in question.

TROUBLESHOOTING

TROUBLESHOOTING 104| Identify distinct binding events by collapsing adjacent bound regions.

TIMING

TIMING

Day 1: Steps 1–2 (approximately 1–4 h, depending on numbers of cells or tissues being collected)

Day 2: Steps 3–9 (approximately 8 h, should be started first)

Day 2: Steps 10–21 (approximately 2 h and overnight incubation)

Day 3: Steps 22–32 (approximately 8–9 h, or approximately 2 h and overnight incubation)

Day 4: Steps 33–53 (approximately 9 h and overnight incubation)

Day 5: Steps 54–64 (approximately 6–7 h)

Day 6: Steps 65–88 (approximately 7–8 h and 40-h hybridization)

Day 8: Steps 89–98 (approximately 1–2 h and scanning time)

TROUBLESHOOTING

Troubleshooting advice can be found in Table 1.

ANTICIPATED RESULTS

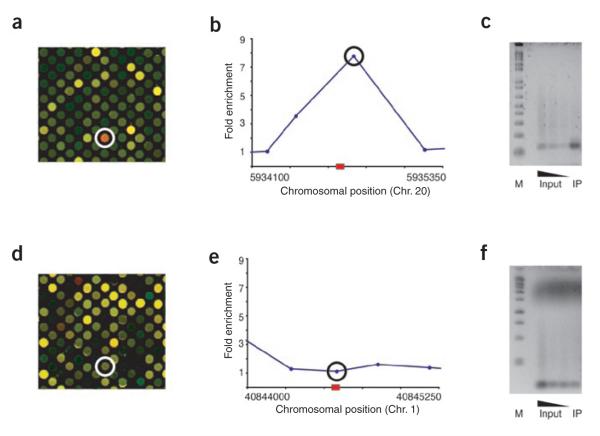

Step 42 (i)

Measure DNA concentration of input DNA (from Step 20) with NanoDrop. Input DNA samples should be approximately 70 μl total volume with a DNA concentration of 300–500 ng μl−1. Immunoprecipitation samples are usually too dilute to detect reliably and measurements are sometimes skewed due to the glycogen that is added to the sample, but we have pooled and precipitated several immunoprecipitates and, after adjusting for changes in volume, expect a DNA concentration of 2–6 ng μl−1. The immunoprecipitated DNA concentration may be higher if the immunoprecipitation is directed against an abundant protein.

Step 42 (ii)

Run a 2% agarose gel of the input DNA that is saved prior to immunoprecipitation (Step 20). This allows you to visually check the distribution of fragment sizes that result from sonication, and to confirm digestion of RNA. Examples of different distributions of fragment sizes resulting from different degrees of sonication are shown in Figure 2. We would first try ChIP with the fragment distribution that is seen with 12 cycles of sonication, as this is the lowest amount of sonication that results in a majority of fragments, ranging from 200–600 bp. The fragment distribution that is seen with eight cycles of sonication is also likely to yield reasonable ChIP results, but this material has generally larger fragments that could reduce the ability to resolve binding events. The fragment distribution that is seen with 16 cycles of sonication is similar to the 12-cycle material, but we would default to the lower amount of sonication. Note that different cell types, growth conditions and crosslinking conditions will change the appearance of similar sonication time courses. However, the basic principle of finding a setting that minimizes sonication while maximizing fragments in the range of 200–600 bp should still be a useful starting point.