Abstract

Over the past two decades, designed metallopeptides have held the promise for understanding a variety of fundamental questions in metallobiochemistry; however, these dreams have not yet been realized because of a lack of structural data to elaborate the protein scaffolds before metal complexation and the resultant metallated structures which ultimately exist. This is because there are few reports of structural characterization of such systems either in their metallated or non-metallated forms and no examples where an apo structure and the corresponding metallated peptide assembly have both been defined by x-ray crystallography. Herein we present x-ray structures of two de novo designed parallel three-stranded coiled coils (designed using the heptad repeat (a→g)) CSL9C (CS = Coil Ser) and CSL19C in their non-metallated forms, determined to 1.36 Å and 2.15 Å resolutions, respectively. Leucines from either position 9 (a site) or 19 (d site) are replaced by cysteine to generate the constructs CSL9C and CSL19C, respectively, yielding thiol-rich pockets at the hydrophobic interior of these peptides, suitable to bind heavy metals such as As(III), Hg(II), Cd(II) and Pb(II). We use these structures to understand the inherent structural differences between a and d sites to clarify the basis of the observed differential spectroscopic behavior of metal binding in these types of peptides. Cys side chains of (CSL9C)3 show alternate conformations and are partially preorganized for metal binding, whereas cysteines in (CSL19C)3 are present as a single conformer. Zn(II) ions, which do not coordinate or influence Cys residues at the designed metal sites but are essential for forming x-ray quality crystals, are bound to His and Glu residues at the crystal packing interfaces of both structures. These “apo” structures are used to clarify the changes in metal site organization between metallated As(CSL9C)3 and to speculate on the differential basis of Hg(II) binding in a versus d peptides. Thus, for the first time, one can establish general rules for heavy metal binding to Cys-rich sites in designed proteins which may provide insight for understanding how heavy metals bind to metallochaperones or metalloregulatory proteins.

Introduction

Due to the inherent complexity of proteins, it is often difficult to discern the sequence determinants that confer structural stability and function to the biopolymer. Hence, a complete understanding of how a protein’s primary amino acid sequence defines its three dimensional structure and function has eluded many researchers for decades and still it is not very well understood. One approach to simplify this problem is the de novo design of model proteins and peptides which are less complex than their natural counterparts, yet contain sufficient information in their sequences to clarify protein structure-function relationships.1–3 Current studies in protein design are focused on unveiling important structural features in natural protein systems with the ultimate goal of using this knowledge to design novel proteins that are tailor-made to carry out receptor, sensory, and catalytic functions.4–9 De novo design of proteins and metalloproteins has been dominated by α-helical coiled coil and bundle domains; however, secondary structural motifs other than α helices have also been used such as β2α,10–12 small peptides that bind metal clusters at loop region,13–15 γ turns,16 β-hairpin peptides17,18 and β sheet structures.19–21

Research in our laboratory focuses on the broad areas of heavy metal biochemistry and metalloprotein design. The systems that are used to understand these fundamental issues are the TRI,22 GRAND23 and Coil Ser24 series of peptides, designed based on the well known heptad repeat (Table 1 shows the sequences) and form well folded three-stranded parallel coiled coils in solution and solid state. One of our major goals has been to develop models that provide a foundational understanding of the interactions of heavy metals with different metalloregulatory proteins such as MerR, ArsR/Smtb and to develop effective heavy meal sequestering agents. We have reported numerous successes using the de novo protein design strategy to further understand heavy metal biochemistry using peptide systems based on the three-stranded coiled coil motif (TRI series), including the first water soluble spectroscopic model of the MerR protein25, the first trigonal pyramidal As(III) bound to three cysteines as a model of ArsR26 (Coil Ser series) and the first example of a trigonal thiolate Cd(II).27,28 From a metalloprotein design perspective we have provided a quantitative thermodynamic evaluation of Hg(II) binding demonstrating cooperative metalloprotein folding23 and using the GRAND series we have been able to design for the first time heterochromic peptides that sequester Cd(II) as 4-coordinate CdS3O at one site and as trigonal planar CdS3 structure at a second site within the same peptide construct.29,28 The TRI and GRAND series of peptides are related to VaLd, in which valine occupies all a positions and leucine all d positions, which was shown30 using x-ray crystallography to be a parallel three stranded coiled coil. Substitution of one or more Leu residues from a and/or d position of TRI or GRAND peptides with Cys or Penicillamine (Pen) generate thiol-rich sites at the interior of the coiled coil which bind heavy metals such as Hg(II), Cd(II), As(III), Pb(II) and Bi(III).22,23,25–27,29,31–36 While effective protein based heavy metal sequestering agents, these series of peptides are not easily crystallizable. For structural studies we have used the structurally similar substituted Coil Ser (CS) series of peptides (Table 1) which are also based on a heptad repeat, and which can crystallize as parallel or anti-parallel three-stranded coiled coils. Coil Ser was first crystallized by Lovejoy and DeGrado et al, as an anti parallel coiled coil at low pH.24 It was suggested that the steric clash between the N-terminal Trp residues led to the antiparallel orientation. Subsequent NMR work demonstrated that Coil Ser formed parallel three stranded coiled coils in slightly basic solution.37 We have subsequently characterized both metallated and apo derivatives of Coil Ser peptides which have been shown to be parallel three stranded coiled coils. This orientation may reflect the pH, the sequence modification, the presence of metals bound in the hydrophobic interior, the presence of Zn(II) ions that bind to external His and Glu residues at the crystal packing interfaces or a combination of these factors.26,38

Table 1.

Peptide sequences used in this study

| Peptide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| TRI | Ac-G LKALEEK LKALEEK LKALEEK LKALEEK G-NH2 |

| Grand | Ac-G LKALEEK LKALEEK LKALEEK LKALEEK LKALEEK G-NH2 |

| Coil Ser | Ac-E WEALEKK LAALESK LQALEKK LEALEHG-NH2 |

| CSL9C | Ac-E WEALEKK CAALESK LQALEKK LEALEHG-NH2 |

| CSL19C | Ac-E WEALEKK LAALESK LQACEKK LEALEHG-NH2 |

| CSL16Pen | Ac-E WEALEKK LAALESK XQALEKK LEALEHG-NH2 |

| CSL16DPen | Ac-E WEALEKK LAALESK XQALEKK LEALEHG-NH2 |

X = Penicillamine. Residues in red indicate substitutions from parent peptides

D-Pen = D- Penicillamine

Despite the fact that there are a significant number of studies using de novo designed peptide systems by many different groups, there are only few examples of structurally characterized de novo designed constructs available in literature. The most well characterized systems are four helix bundle motifs consisting of dimers of helix-turn-helix peptides known as Dueferri (DF), designed by DeGrado. These peptides serve as paradigms for di-iron, di-zinc and di-manganese containing natural proteins and contain carboxylate (Glu) bridged dinuclear metal sites at the center of the four helix bundle.39 Various Zn(II), Cd(II) and Mn(II) derivatives of DF have been characterized crystallographically.40–42 To determine the extent to which the active site is preorganized in the absence of metals, NMR structure of apo DF1 was solved which suggested that the native fold and metal binding site are largely preorganized in the apo protein.43 Active sites of metalloproteins are frequently preorganized in the absence of metals, which requires burial of polar amino acids at the interior at the expense of folding free energy.44 Preorganization requires that proteins impart their own structural preference on metals to bind in a specific geometry.

We have been directing our efforts towards the structural characterization of various three-stranded coiled coils. Recently we reported the x-ray structure26 of As(CSL9C)3 where As(III) is coordinated to three Cys residues in an endo conformation within a protein environment. This construct served as the first structural model for As(III) binding to ArsR or ArsD.45,46 We have also successfully obtained the structures of both L- and D- versions of unmetallated (apo) Pen derivatives (CSL16LPen and CSL16DPen) which are both substituted in the a heptad position.38 The sulfur atoms of L- thiol containing residues appear to be orientated in a similar way when the mutation occurs at an a site and appear to be independent of both the place of substitution in the coiled coil, 9 vs. 16, the nature of the coordinating ligand, L-Cys vs. L-Pen, as well as the state of metallation. A comparison of the structures of apo (CSL16LPen)3 and metallated As(CSL9C)3 show that the sulfurs appear to be pre-organized for metal binding. The major differences in the Pen vs. Cys structures are the packing of the two methyl groups on the Pen. The plane below the Cys is blocked by one set of methyl groups which point towards the interior of the coiled coil below the sulfurs, the second set of methyl groups point away from the center in-between the helical interfaces. The D-Pen points down towards the C-terminus and most interestingly appears to point away from the interior of the coiled coil towards the helical interfaces. The dramatically different Cd(II) binding to CSL16LPen and CSL16DPen has been correlated with the structural differences. Furthermore we have demonstrated that the affinities and selectivities of metal binding to a vs. d site substituted peptides are different in solution.36,47 Cd(II) binds selectively to a site and has 10 fold higher binding affinity over d site.34 Pb(II) on the other hand has 4 times higher affinity for binding to d site over a site.48 Evidently structural information about a and d sites within these coiled coils is sorely-required.

In this article we present the structures of two apo peptides, (CSL9C)3 which is an a site peptide, and (CSL19C)3 which is a d substituted peptide. With the apo structure of the a site peptide (CSL9C)3 we address local/global structural differences with the metallated analogue As(CSL9C)326, effect of arsenic binding on the overall structure of the peptide and answer questions as to whether As(III) binding changes significantly the conformation of the coordinating Cys residues, the extent of the degree of preorganization of the coordinating residues at the metal binding site and finally whether large amounts of water are extruded on metal coordination. The structure of apo (CSL9C)3 now provides a comprehensive basis for a direct comparison of the metallated and apo three-stranded coiled coils in these types of designed polypeptide systems. The apo (CSL19C)3 structure allows us to address whether there are major conformational differences between the orientation of Cys sulfurs in a vs. d sites, which thiol site generates more void space in the hydrophobic interior, how different are the packing of hydrophobes above and below the Cys site and what are the consequences of the observed differences. The (CSL9C)3 structure shows that the Cys side chains have conformational flexibility and the orientation is partitioned between the coiled coil interior and helical interface. Based on the structural analysis of these two apo peptides we also hypothesize possible modes in which Hg(II) would coordinate to these peptides. With the knowledge gained from this study we now have access to the rules for the de novo design of metal binding sites within the interior of coiled coils, as well as a deeper understanding of heavy metal binding in designed proteins, potentially providing significant insight into metal binding in metalloregulatory proteins and metallochaperones.

Results

Overall Structure

The X-ray structures of well folded three-stranded parallel coiled coil peptides (CSL9C)3 and (CSL19C)3 have been determined to 1.36 Å and 2.15 Å resolution, respectively. The final model of (CSL9C)3 contains 816 protein atoms, 59 water molecules, 5 Zn(II) ions, 1 Ca(II) ion and 3 ethylene glycol molecules. (CSL19C)3 contains 699 protein atoms, 19 water molecules and six Zn(II) ions. The RMSD between the 29 amino acids of CSL16L-Pen (PDB code 3H5F)38 as the search model and the final refined structure of (CSL9C)3 is 0.024 Å. Leu 9 of CSL16L-Pen were mutated to Cys and the side chains of Pen 16 were modified in such a way that they resembled Leu residues containing only Cβ and Cγ atoms before using it as a search model for Molecular Replacement. After one round of refinement the methyl groups of Leu were built in using the density present in Fo-Fc electron density map. Using the first 26 amino acids of the single helix of Coil VaLd (PDB code 1COI)30 as the search model the RMSD for the final refined structure of (CSL19C)3 is 0.025 Å. All non-glycine residues for both the structures fall in the right handed α helical region of the Ramachandran plot.49 The carbonyls of N-terminal capping acetyl groups in both structures are hydrogen bonded to Ala 4 of respective main chains. In (CSL9C)3 the amide NH2 groups of chains A and C are hydrogen bonded to the main chain CO of Ala 25 from respective chains. All side chains in both the structures except those involved in metal binding or hydrogen bonding to solvent molecules are present in their preferred rotameric conformation as analyzed by rotamer check utility in Coot.50

Cysteine Sites

Side chains of all three cysteine residues of CSL9C display alternate conformations. The cysteine side chains in all three helices are oriented in essentially equal proportion between the coiled coil interior and the helical interface (in chain C the cysteine side chain is oriented towards the interior and helical interface at what is best modeled as a 60:40 ratio). Thus, there is an ensemble of different combinations of cysteine side chain orientations between three peptide helices. Out of these different orientations of three Cys side chains, 15% (0.5×0.5×0.6×100%) of the time all the cysteine side chains are exclusively oriented towards the interior of the coiled coil and 10% of the time all of them are oriented towards the helical interface. The orientations of the two conformers of Cys residues are shown in Figure 1. The separation between the Sγ atoms (S-S) of the three cysteines for the interior conformation is 3.32 Å, whereas the Sγ atoms for the exterior conformation are separated at a distance of 6.85 Å with respect to each other. It can be seen from Figure 1 that the thiol groups of cysteine side chains in the interior conformation are directing towards the N-termini of the helices, whereas those in the exterior conformation are pointing towards the C-termini. The distance between the planes formed by the Sγ atoms of the two conformers of cysteines is 1.11 Å. The β-methylene carbons of all Cys residues are pointing towards the N-terminus of the helical scaffold. The distance between the Cα and Cβ planes of cysteines is 1.07 Å. The Sγ atoms in the interior orientation of cysteines are in a plane which is at a distance of 0.59 Å above from the Cβ plane of cysteines. On the other hand, the Sγ atoms in the exterior orientation of cysteines are in a plane which is 0.52 Å below from the Cβ plane of cysteines. The χ1 dihedral angles (N-Cα-Cβ-Sγ) for the interior orientation of cysteines are −70.3 ± 3.9 which are close to the value of −65.2° for most common cysteine rotamers.51 The χ1 values for the outer conformer are 171.4° ± 6.2. The leucine layers above (Leu 5) and below (Leu 12) Cys 9, both of which are d sites of the heptad, are oriented differently (Figure 2). Leu 5 is oriented more towards the center of the coiled coil with the Leu 12 layer being oriented away from the center. One methyl group of both Leu 5 and Leu 12 is pointing towards the N termini and the other one is directing towards the C termini. The distances between the planes formed by the Cγ atom of Leu 5 and Leu 12 and the Sγ of interior cysteines conformer are 3.85 Å and 5.29 Å, respectively. The distances for the exterior cysteine conformer are 4.99 Å and 4.24 Å from Leu 5 and Leu 12 planes formed by the Cγ atoms, respectively.

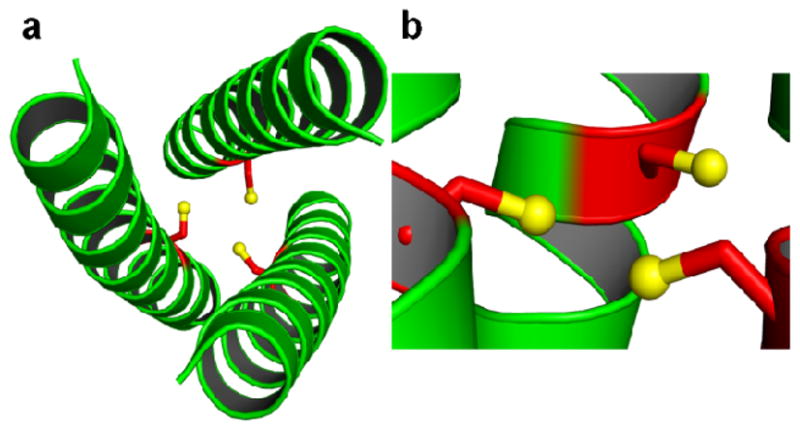

Figure 1.

Ribbon diagrams of (CSL9C)3 showing the orientation of Cys side chains. Main chain atoms are shown as green ribbon and the Cys side chain as red stick with the thiol groups being shown as yellow spheres. Top-down view from N termini showing the exclusive orientation of the a) major conformer (15%) where all the Cys side chains are pointing towards the interior of the coiled coil and b) minor conformer (10%) where all Cys side chains are oriented towards the helical interface. Side views show that the thiol groups are pointing towards the N- termini and C- termini of the helical scaffold in the interior c) and d) exterior Cys conformers, respectively.

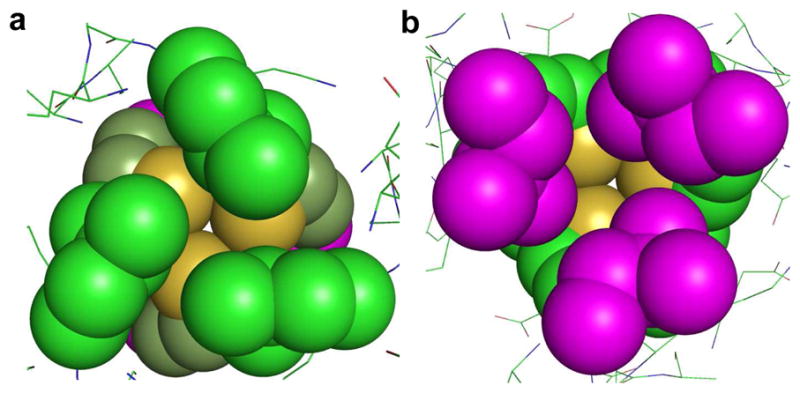

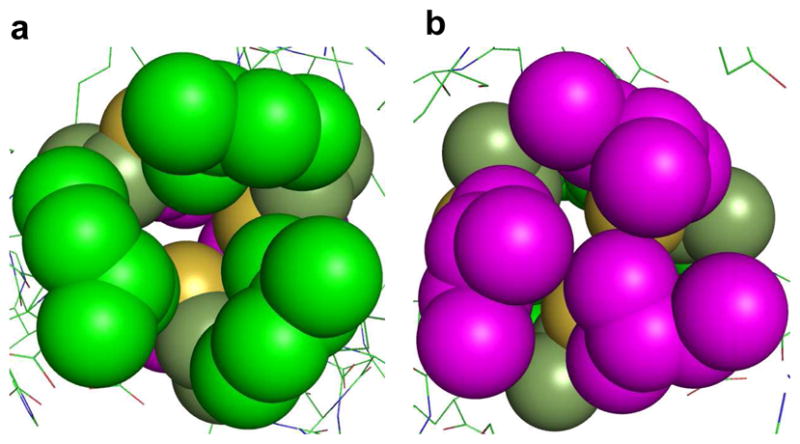

Figure 2.

Packing of Leu layers above and below the Cys site of CSL9C trimer shown as spheres. a) Top-down view from N–termini, showing the Leu 5 layer (green) and b) Leu 12 layer (magenta), viewing from C-termini up the helical axis. It shows that metals with stereochemically active lone pair such as As(III), would bind to a coiled coil in an a site such that the lone pair would be housed in the open space towards the C-termini.

The orientation of the cysteine side chains in (CSL19C)3 is depicted in Figure 3. β-methylene groups of three cysteines are pointing towards the N-termini. The χ angles for the three cysteines are −90.53°, −165.92° and 164.33° for chains A, B, and C, respectively. All three cysteines are present as a single rotamer. Thiol groups of both Cys B and C are oriented toward the interior of the helices and towards the C-termini, while Cys A is oriented toward the helical interface and almost perpendicular to the helical axis. The latter orientation towards the helical interface is in accordance with previous predictions22 which were based on the Coil VaLd structure.30 Electron density in the center of the coiled coil corresponding to a heavy atom was not found in Fo-Fc maps down to a contour level of 2 σ. The cysteine sulfhydryl groups were found to be greater than 3 Å from one another, excluding the possibility of disulfide bridge formation, which would not be likely at pH 6.5 where the cysteines are more likely to be protonated than deprotonated. The S-S distances for Cys A - Cys B, Cys B - Cys C and Cys C - Cys A are 4.64 Å, 3.40 Å and 4.59 Å, respectively.

Figure 3.

Ribbon diagrams of (CSL19C)3 showing the orientation of Cys side chains. Main chain atoms are shown as green ribbon and the Cys side chain as red sticks with the thiol groups being shown as yellow spheres. a) Top-down view from N termini showing that two Cys side chains are pointing towards the interior of the coiled coil with the third thiol directed towards the helical interface. b) Side view shows that two thiol groups are pointing towards the C- termini of the helical scaffold and the third thiol is almost perpendicular to the helical axis.

Non-covalent Interactions

The structure of (CSL9C)3 has seven interhelical salt bridge interactions. Glu 3 B forms an intrahelical salt bridge with Lys 7. In addition to interhelical salt bridge interactions between side chains of e and g residues Glu and Lys commonly found in coiled coils, there is also an unusual interhelical salt bridge present, between b and g residues involving Glu 24 A and Lys 22 C. There is an interhelical water mediated hydrogen bonding interaction between Lys 22 A/Glu 20 B. The indole NH of Trp 2 B is involved in hydrogen bonding with Glu 6 B side chain. There are many hydrogen bonding interactions involving side chain and main chains such as, Glu 3 A and Glu 3 C to main chain NH of same residues, Ser 14 C to the main chain CO of Ala 10 and Ser 14. Finally, there are some intrahelical hydrogen bonds involving side chains such as Glu 20 C to Gln 17 C. There are five inter-helical electrostatic interactions in (CSL19C)3. Glu 24 B and Lys 22 B are an example of the e-g salt bridge typically found in three-stranded coiled coils. An interaction between Glu 1 C and Glu 6 B is mediated by a water molecule. Glu 1 C is hydrogen bonded to Trp 2 B and Glu 1 B is hydrogen bonded to Trp 2 A. Helical wheel diagrams of (CSL9C)3 and (CSL19C)3 summarize these interactions in Figure S1 and S2 of Supporting Information.

External Metal Binding Sites

Four out of the five Zn(II) ions in (CSL9C)3 are bound at the crystal packing interfaces. One of them (ZN1) has its ligands as Glu 24 B (Oε2), His 28 B (Nε2), a water molecule and Glu 24 A (Oε2) from a symmetry related peptide trimer. The other Zn(II) (ZN2) is bound to His 28 A (Nε2) and Glu 3 B (Oε1, A/Oε2, B), Glu 20 B (Oε1) and Glu 24 B (Oε1) from a symmetry related peptide molecule. ZN3 is bound to Glu 1 B (Oε2), Glu 6 C (Oε2) and two water molecules. ZN4 has two water molecules, Glu 6 A (Oε1) and His 28 C (Nε2) from a symmetry related molecule as its ligands. ZN5 is bound to one water molecule, His 28 B (Nδ1) and Glu 20 A (Oε2) from a symmetry related trimer. The Ca(II) ion is bound to Glu 1 A (Oε2) and Glu 6 B (Oε1, Oε2).

Zn(II) ion sites at the crystal packing interfaces of (CSL19C)3 are very different than that of (CSL9C)3. The six fold screw axis and crystal packing of the structure is shown in Figure S3 in Supporting Information. There are six Zn(II) ions per asymmetric unit, which form two dinuclear Zn(II) sites and two other Zn(II) ions not directly connected by side chain ligands that are 7.6 Å apart. Detailed views of the Zn(II) binding sites are shown in Figure S4 in Supporting Information. The first site, shown in Panel B which is not dinuclear, has one Zn(II) ion coordinated by Glu 27 C, Glu 24 C, and Lys 22 B from one molecule and Glu 3A from another trimer. The neighboring Zn(II) ion is coordinated by His 28 C from one trimer and Glu 1 C and Glu 6 A from another trimer plus one water molecule. The dinuclear Zn(II) site in Panel C contains a bridging glutamate, Glu 6 B, and the coordination sphere of one Zn(II) ion is filled by His 28 A and Glu 24 A from one helix as well as Glu 1 A from the same trimer as Glu 6 B. The other Zn(II) ion of this cluster is coordinated by Glu 3 B, and weakly coordinated by Glu 24 A and the other carbonyl oxygen of Glu 6 B. All three tryptophan residues are closely associated with the Zn(II) sites on the exterior, and are hydrogen bonded to the Zn(II) ligands. The indole nitrogen of Trp 2 A, Trp 2 B Trp 2 C are all 3.8–4.2 Å from a Zn(II) ion.

Discussion

The nomenclature used to define our “apo” and “metallated” peptides is given in ref [52].

(CSL9C)3 and As(CSL9C)3. The α helical backbones of apo and As(III) bound CSL9C are extremely similar and, as shown in Figure 4, overlay very well. This observation demonstrates that As(III) binding does not perturb the overall secondary structure of the coiled coil. Both the apo and As(CSL9C)3 crystallize with 4 Zn(II) ions at the crystal packing interfaces coordinated to His and Glu ligands. In the As(CSL9C)3 structure all four Zn(II) ions in the asymmetric unit are present at the crystal packing interfaces; whereas in apo (CSL9C)3, four (ZN1, ZN2, ZN4 and ZN5) out of five Zn(II) ions in the asymmetric unit are bound at the crystal packing interfaces. The same number of interhelical electrostatic interactions are present in (CSL9C)3 as there are in As(CSL9C)3 except the interaction between Glu 6 B and Glu 1 C which is present only in the latter structure.26 The β methylene carbons of both the apo and metallated (CSL9C)3 structures are pointing towards the N termini of the helices. The thiol groups of As(CSL9C)3 and the major interior conformer of (CSL9C)3 are pointing towards the N termini, with the S-S distance for the major conformer of apo (CSL9C)3 being 3.32 Å, which is 0.07 Å longer than the metallated peptide (3.25 Å). The χ1 dihedral angles for the metallated construct are −60° ± 1 as opposed to −70.3° ± 3.9 for the major conformer of the apo structure. Smaller S-S distance and χ1 dihedral angles in As(CSL9C)3 compared to the apo structure where all cysteines are oriented towards the interior, suggests that the metal binding induces only minor changes in the geometry of the cysteine residues, making them slightly more constrained upon metal binding. The major change, however, is observed in the conformations of cysteine side chains in the metallated structure compared to the apo peptide where the cysteines are orientated towards the helical interface. The apo structure shows sufficient conformational flexibility of the cysteine side chains as out of an ensemble of many different orientations of Cys side chains, only 15% of the time all the cysteines are exclusively oriented in a conformation where they are preorganized for metal binding. It may, however, be noted that the 15% population of preorganized Cys conformers for metal binding is observed in the solid state where the protein is 45% hydrated (Matthews Coefficient 2.25) and it may not necessarily represent situations that may be occurring in solution. The rapid motion between different cysteine conformers results in favorable entropic contribution in the apo structure. Upon metal binding this local conformational motion is restricted to a single cysteine conformer which makes the process entropically unfavorable. Moreover, there is reorganization energy required to orient the thiols to the interior for metal binding. The entropic penalty and the cost of required reorganization energy is overcome by the enthalpic gain upon formation of bonds between the soft thiolate ligands and the As(III) ion. The smaller size of As(III) with ionic radius of 0.72 Å fits well within the smaller cavity generated by the interior cysteine conformer resulting in As-S bond distance of 2.28 Å and mean S-As-S angle of 89°.26 Because of these geometrical restraints, As(III) binding is not suitable to the exterior cysteine conformer. It may be noted that when Cys in an a site is replaced by its bulkier analogue Pen (β, β dimethyl cysteine) in CSL16L-Pen the thiol groups of the major rotamer (95%) are found to be positioned towards the interior of the coiled coil preorganized for metal binding. Improved packing of the methyl groups and restricted rotation due to the additional sterics of the bulky methyl groups, are believed to lead to this enhanced preorganization and rigidity of the thiols.38 This begins to explain the different metal binding properties of Cys vs. Pen sites that we have observed in solution with various metal ions.

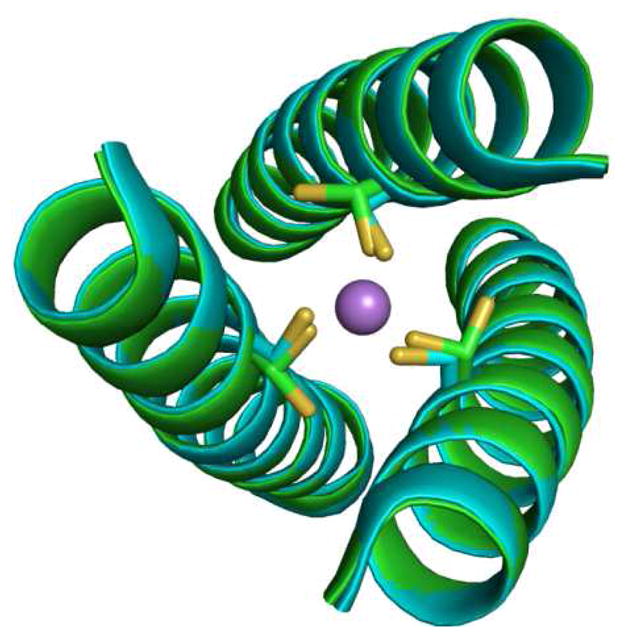

Figure 4.

Ribbon diagram showing top-down view of an overlay of apo (CSL9C)3 (green) and As(CSL9C)3 (cyan) structures. Cysteine side chains are shown in stick form with As(III) as purple sphere. It can be noted that there is no change in the overall secondary structures of apo and metallated peptide. The major change can be noted from the apo structure where Cys side chains are present as alternate conformers which is locked into a single conformer in As(CSL9C)3 upon metal binding.

The degree of preorganization of metal binding ligands in metalloproteins varies depending on the functional requirement of the protein active site. Zinc finger proteins feature a metal binding site where Zn(II) binding induces overall folding of the protein.53 On the contrary, the R2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase displays significantly smaller geometrical changes around metal binding region in the apo versus different dimetallated forms.54–56 Structural comparison between As(CSL9C)3 and (CSL9C)3 shows that As(III) binding does not induce folding of the overall secondary structures of the peptide but the metal binding thiolate ligands in the apo structure show significant local conformational motion which is restricted upon metal binding and locked into a single conformation. The observed dynamics of Cys side chains in the apo structure suggests a mechanism for insertion of metals into the hydrophobic interior of coiled coils and helical bundles. Initial binding of a metal to a ligand such as cysteine located at the helical interface followed by a breathing motion of the helices coupled with the movement of the amino acid side chain to the interior conformer would internalize the metal within the protein’s hydrophobic core.

Intriguingly, the Leu layers above and below the Cys 9 site are oriented in a similar way in both the apo and metallated (CSL9C)3 structures. The Leu 5 layer is tucked in towards the center of the helical axis and the Leu 12 layer is oriented away from the center, thus opening up space below the metal binding site. It is believed that As(III) binds in a hemidirected endo conformation26 to (CSL9C)3 so that the stereochemically active lone pair can be housed in the open space generated by the outward orientation of the Leu 12 layer below Cys 9.

(CSL9C)3 and (CSL19C)3. Once again the peptide backbones of the two apo structures CSL9C and CSL19C overlay very well as shown in Figure 5. The Cβ atoms of cysteines in both the structures are pointing towards the N termini of the helical scaffold. Cysteine side chains of CSL19C appear to be present in single conformers and show sufficient rigidity as opposed to CSL9C. The S-S separations in CSL19C vary from each other; however, they do generate a larger cavity with which to bind metals with larger ionic radii such as Pb(II). In this structure of CSL19C the cysteines are oriented in such a way that the thiol plane formed by Sγ atoms is not parallel to the planes formed by the Cγ atoms of Leu 16 and Leu 23. The angle between the thiol plane and Leu 16, Leu 23 planes are 8.28° and 3.02°, respectively (Figure S5 in Supporting Information). On the contrary the thiol plane for CSL9C is parallel to Leu 5 and 12. Leucines above and below Cys 19 site are at positions 16 and 23 of the peptide chain and both correspond to a sites of the heptad. The Leu residues at the 16 layer are positioned away from the center of the helical axis whereas those at layer 23 are directing towards the center of the helical axis, see Figure 6. Thus, the Leu 16 layer generates more open space compared to that of the Leu 23 layer. The orientation of these Leu layers above and below the thiol site is exactly opposite compared to those of Leu 5 and Leu 12 of CSL9C as mentioned earlier. These differential orientations of Leu layers above and below the cysteine a and d sites represent one of the important factors that define site selectivity and binding mode preferences of some metals to such sites.

Figure 5.

Ribbon diagram showing the overlay of apo (CSL9C)3 (green) and (CSL19C)3 (red). The secondary structures in both the constructs are unperturbed.

Figure 6.

Packing of Leu layers above and below the Cys site of CSL19C trimer shown as spheres. a) Top-down view from N–termini of Leu 16 layer (green) and b) Leu 23 layer (magenta), viewing from C-termini up the helical axis.

Cys vs. Pen Structures

Recently we have reported the X-ray structures of CSL16L-Pen and its diastereomeric counterpart CSL16D-Pen where the chirality of one amino acid is altered from L- to D- within the coiled coil.38 Figure S6 in the Supporting Information shows the overlay of the α-helical backbones of the two Cys structures (CSL9C, CSL19C) and two Pen structures (CSL16L-Pen, CSL16D-Pen). The β-methylene carbons and thiol groups of CSL16L-Pen are oriented towards the N-termini similar to CSL9C. Thiol groups of the major rotamer (95%) of each Pen residue in CSL16L-Pen are positioned towards the interior of the coiled coil with S-S distances of 3.7 Å as if preorganized for metal binding like the major rotamer of CSL9C (15%, for all Cys side chains). Enhanced degree of preorganization in the Pen structure compared to the Cys structure is believed to be incurred by improved packing of the methyl groups above and below the sulfur plane (one methyl group is pointing towards the N-termini and helical interface whereas the other one is directed towards the C-termini and the interior of the coiled coil) and restricted rotation of the bulky methyl groups. The thiols in the lower abundance rotamers in Pen (5%, each side chain) and Cys (10%, for all side chains) structures are oriented away from the helical axis, towards the helical interface. In CSL16D-Pen the thiols are directing towards the C-termini similar to the two thiol side chains in CSL19C. All the thiols in CSL16D-Pen are positioned away from the helical axis, towards the helical interface and thus this site is not preorganized for metal binding within the coiled coil interior. With one thiol group being oriented towards the helical interface in CSL19 the resulting thiol pockets in both D-Pen and CSL19 structures are large in general. This analysis suggests that there is some similarity in side chain orientation and the resulting thiol site in CSL19C with an L-amino acid in a d site and in CSL16D-Pen with a D-amino acid in an a site. Because of opposite chirality of D-Pen and L-Cys, the Cβ atoms in these two structures are oriented differently. Additionally, the effect of methyl groups in the D-Pen structure might have a significant impact on the observed differential orientation of the thiol groups in the two structures.

Implications of Binding Hg(II)

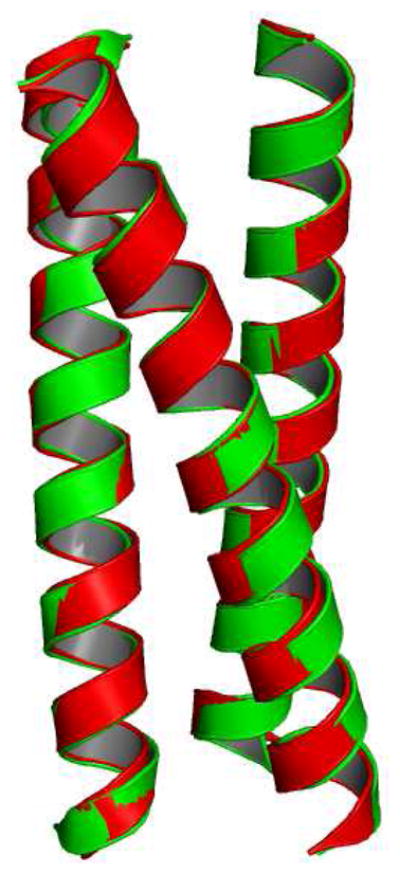

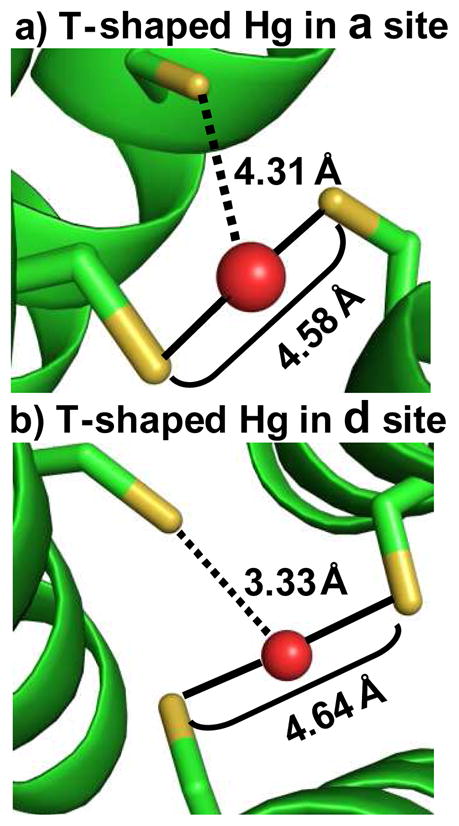

We have shown previously using 199Hg NMR and 199mHg PAC spectroscopic techniques that Hg(II) coordinates to a site TRI peptides as linear dithiolate HgS2 complex at the interior of a three stranded coiled coil at pH 6.5 in the presence of 1:3 ratio of Hg(II):peptide.57 This dithiolate-Hg(II) complex is different than Hg(peptide)2 as the presence of a third helix with a protonated cysteine breaks the axial symmetry of the Hg(peptide)2 complex making the Hg(II) adopt a T-shaped geometry. Studies with d site peptides also indicate the formation of T-shaped Hg(II) complex at the interior of three-stranded coiled coils under similar conditions (V.L.Pecoraro et al., unpublished results). However, with 199Hg NMR chemical shift δ = −895 ppm the d site is believed to be more T-shaped than the corresponding a site which has a 199Hg NMR chemical shift δ = −908 ppm. When the pH is raised, a trigonal Hg(peptide)3− complex is formed. The conversion from the Hg-dithiolate to Hg-trithiolate complex occurs with a pKa of 8.6 for the d site which is one pKa unit higher than the corresponding a site value of 7.6. The analysis of apo structures of (CSL9C)3 and (CSL19C)3 reveal that two thiols in each structure are at optimal distances of 4.58 Å and 4.64 Å, respectively, to accommodate Hg(II) in linear coordination, the ideal Hg-S distance for linear HgS2 being 2.32 Å.34 One of these thiols in each structure is oriented towards the interior of the helical scaffold and the other thiol to the helical interface. It is possible that linear coordination of Hg(II) in either a or d substituted peptides consists of these two types of thiols as ligating residues forming a preformed 2-coordinate site for Hg(II). Figure 7 shows the models of T-shaped Hg(II) complexes with CSL9C and CSL19C. It can be seen that the third thiol is at a distance of 4.31 Å and 3.33 Å from linear Hg(II) in (CSL9C)3 and (CSL19C)3, respectively. This difference in distances indicates that the geometry of the two T-shaped Hg-complexes are not same and may serve as structural models to explain the observed difference in 199Hg NMR δ values between a and d sites. Our models from this study suggest that Hg(II) fits better in an a site as a trigonal HgS3 at high pH than in a d site which is confirmed by 199Hg NMR (δ = −185 ppm for a site and δ = −313 ppm for d site).57,58 This observation may also serve as a plausible explanation for the higher pKa for HgS2-SH → HgS3 complex formation for the d site compared to the a site. These structures provide important insight into explaining observed differences in metal binding to these sites in solution.

Figure 7.

Models of T-shaped Hg(II) complexes inside three-stranded coiled coils. Shown are possible coordination modes of Hg(II) with the two thiols in a) CSL9C and b) CSL19C where one thiol is pointing towards the interior and the other towards the helical interface. Peptide backbone is shown as green ribbon, Cys residues as ball and stick and Hg(II) as red sphere. Solid lines between sulfur atoms and Hg(II) in the two models represent S-Hg-S bonds; whereas the dotted lines from the third sulfur to the Hg(II) represent situations where this third sulfur may or may not be coordinated to the Hg(II) ion. With S-S separation of 4.58 Å and 4.64 Å these two thiols are well suited to bind Hg(II) in linear coordination. The third thiol in CSL19C being at a shorter distance than in CSL9C may explain why Hg(II) in d sites is believed to be more T-shaped than in a site.

Presence of Zn(II) at the Crystal Packing Interfaces

Crystallization of CSL9C and CSL19C was not successful in the absence of Zn(II). Binding of Zn(II) to His and Glu residues at the crystal packing interfaces links the coiled coils together and provides a third dimension to the crystals and thus generates better diffraction quality crystals for x-ray studies. In the absence of Zn(II), however, 2D plate-like crystals are obtained which are not suitable for x-ray structural studies. As Zn(II) has intermediate polarizability (hard-soft character), it uses both hard ligands such as His, Glu, Asp and water molecules and soft ligands such as Cys in naturally occurring metalloproteins. However, in the majority (65%) of the Zn(II) containing metalloproteins, Zn(II) uses amino acids such as His, Glu, Asp and water molecules as all of its first coordination sphere ligands.59 Zn(II) binding to His and Glu residues and waters at the crystal packing interfaces of our peptides is not an exception of this later situation.

To examine the effect of external Zn(II) ions on the physical and spectroscopic properties of the bound metal at the designed metal binding site in solution, we have performed studies with CSL9C peptide and monitored the physical properties of Hg(II) in the presence of a varying concentration of Zn(II). Measures taken to remove ubiquitous Zn(II) ions from solution is described in the Materials and Methods. These studies were performed both at low pH, where the HgS2 complex is formed within the three-stranded coiled and at high pH where the HgS3 complex is formed. Given that the solubility product60 of Zn(OH)2 is 2.1×10−16 and the high peptide concentrations (milimolar) used in the solution studies at low pH, experiments were not possible at pH values higher than 6.5 for the UV-Vis and 5 for 199Hg NMR experiments due to hydrolysis of Zn(II) leading to the formation of ZN(OH)2 as precipitate. For the same reason, Zn(OH)2 experiments at pH 8.6 where the HgS3 complex is formed, were not possible to perform above 10 μM CSL9C and 30 μM Zn(II) concentrations. Due to the low concentrations of peptide used at high pH experiments, it was not possible to obtain 199Hg NMR measurements.

The UV-Vis titration in Figure S7 of the Supporting Information shows that addition of up to 21 equivalents of Zn(II) (per monomer) to 2.5 mM CSL9C in the presence of 1 eq of Hg(II) (per trimer) at pH 6.5 does not seem to cause any changes in the HgS2 signal at 247 nm as at this low pH condition Hg(II) coordinates to the peptide as linear HgS2 within a three-stranded coiled coil.34,57,58,61 The overall UV-Vis spectra overlay very well in the presence of varying concentrations of Zn(II) except in the Trp absorbance region ~280 nm. The crystallographic conditions for CSL9C : Zn(II) is 5.1 mM : 17 mM, i.e. 1 : 3. For the UV-Vis experiments the CSL9C : Zn(II) ratio is 2.5 mM : 52.5 mM, i.e. 1 : 21. Although the absolute concentration of the peptide is half that which is present in crystals, this data shows that a 7 fold relative excess of Zn(II) compared to the crystallographic conditions has no effect on binding of Hg(II) to CSL9C. Titration of Hg(II) to CSL9C in the presence of 21 equivalents Zn(II) (per monomer) (Figure S8, A) and in the absence of Zn(II) (Figure S8, B) show that the stoichiometry of CSL9C : Hg(II) is unchanged (3 : 0.95) in the presence of Zn(II). Additionally, the molar extinction coefficient (2050 M−1cm−1 at 247 nm) in the presence of Zn(II) is similar to the value of 2000 M−1cm−1 observed in the absence of Zn(II). Similar values of molar extinction coefficient have been observed for linear HgS2 within a three-stranded coiled coil for TRI peptides.58,61 Hg(II) binding titration data both in the presence and absence of Zn(II) were analyzed by non-linear least squares fits. Because of strong binding, the minimum affinities obtained for Hg(II) binding to CSL9C in the presence and absence of Zn(II) are 1.4×107 M−1 and 2.3×107 M−1, respectively. 199Hg NMR chemical shift of 12 mM CSL9C and 252 mM Zn(II) (1 : 21 CSL9C : Zn(II), a 6 fold absolute excess of Zn(II) compared to crystallographic conditions) in the presence of 1 equivalent Hg(II) (per trimer) at pH 5 is −926 ppm (Figure S9, A), expected for a T-shaped Hg(II) complex within a three-stranded coiled coil. The same chemical shift is observed under similar conditions in the absence of Zn(II) (Figure S9, B). These studies show that the presence of Zn(II) up to a concentration that is several fold excess compared to what is present under crystallographic conditions does not influence the stoichiometry, affinity and coordination number of Hg(II) bound at the designed metal site.

Titration of HgCl2 to 10 μM CSL9C in 50 mM CHES buffer in the presence (Figure S10, A) and absence (Figure S10, B) of 30 μM Zn(OAC)2 at pH 8.6 shows that the stoichiometry of CSL9C : Hg(II) is not influenced by the presence of 3 fold excess of Zn(II). The molar extinction coefficient of HgS3 complex is similar in the presence and absence of Zn(II) at pH 8.6, the values being 18000 and 19500 M−1 cm−1, respectively, at 247 nm. Hg(II) titration data were fit using non-line least square analysis. Due to strong binding the minimum values of binding constants obtained are 6.6×107 M−1 and 4.3×107 M−1 in the presence and absence of Zn(II), respectively. These results show that the presence of a 3 fold excess of Zn(II) does not influence the stoichiometry and affinity of Hg(II) bound at the Cys site as HgS3.

Conclusions

Having solved the crystal structures of apo CSL9C, an a site, apo CSL19C, a d site peptide, as well as our previously reported apo L-Pen (an analogue of Cys) and D-Pen a site structures, we are now in a unique position to evaluate the structural implications on modifying backbone chirality vs. the subtle differences we have just reported between a vs. d sites. At first glance, there is a striking similarity between the D-Pen in an a site and a L-amino acid (Cys) in a d site. Though these sites are not identical, (most significantly the beta-C points towards the C-terminus for the D-amino acid) qualitatively, the orientation of thiols leads to larger thiol pockets in both the structures. From this similarity one can envision that a D-amino acid in a d site may resemble an a site with L- amino acid. Furthermore, this approach may allow us to alter the various types of a vs. d site specificity we have previously reported. Using the lessons learned from the structures of apo CSL9C and CSL19C, we have discussed the possible coordination modes in which heavy metals such as As(III) and Hg(II) can be sequestered by these peptides. Clearly, additional structures of metallated constructs would give direct evidence of the possible ways of metal coordination to these peptides. This article, which details the salient features of two de novo designed apo structures, can now serve as a basis for understanding solution behavior of metal encapsulation and physical properties of metallo derivatives of Coil Ser and related de novo designed family of peptides.

Materials and Methods

Peptide Synthesis and Purification

Peptides CSL9C and CSL19C were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems 433A automated peptide synthesizer using standard Fmoc protocols62 and purified by reverse-phase HPLC on a C18 column at a flow rate of 10 mL/min using a linear gradient that was varied from 0.1% TFA in water to 0.1% TFA in 9:1 CH3CN:H20 over 50 minutes. Purified peptides were characterized by electro spray mass spectroscopy.

Crystallization

Crystals of CSL9C were grown by vapor diffusion on a hanging drop at 20°C containing equal volumes (2 μL) of peptide (19.15 mg/mL CSL9C, 17 mM Zn(OAc)2, 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer at pH 6.0) and precipitant (100 mM Ca(OAc)2 and 24% PEG 3350). Crystals were soaked in the mother liquor and cryo protectant (20% ethylene glycol) prior to freezing in liquid N2. CSL19C was crystallized by vapor diffusion in a sitting drop with equal volumes of peptide (10 mg/mL in 20 mM Zn(OAc)2) and a precipitant solution (100 mM MES pH 6.5 and 40 % Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-200). The hexagonal plate-like crystals obtained were mounted in a 0.15 mm robotic loop and frozen in their mother liquor in liquid N2 for data collection.

Data Collection and Refinement

Data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source of the Argonne National Laboratory on the LS-CAT Beamline 21-ID, equipped with a Mar 225 CCD detector. 360° frames of data were collected with a rotation of 1° and exposure time of 1s. The data were processed and scaled with HKL 2000.63 The space group of CSL9C was determined to be C2. The structure of CSL9C was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser in CCP4 suite of programs64,65 by using 29 amino acids of CSL16L-Pen (PDB code 3H5F)38 as the search model. Leu 9 of CSL16L-Pen were mutated to Cys and the side chains of Pen 16 were modified in such a way that they resembled Leu residues containing only Cβ and Cγ atoms before using it as a search model for Molecular Replacement. The generated model was refined with restrained refinement by Refmac 5 in CCP4 suite of programs66 and built in and completed in Coot67 by using the 2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc electron density maps generated in Refmac 5. After one round of refinement the methyl groups of Leu were built in using the density present in Fo-Fc electron density map. The final structure was refined to 1.36 Å resolution (Rworking = 18.2%, Rfree = 21.5 %). The coordinates and structure factors of CSL9C have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the ID code 3LJM.

For CSL19C the space group was determined to be P61 or P65. Molecular replacement with both potential space groups was performed in the program Phaser in the CCP4 suite of programs64,65 with the first 26 amino acids of a single helix of Coil VaLd (PDB code 1COI)30 as a search model. The top 65% of rotation function solutions were included in the translation search. In two separate trials three and six helices were searched for with zero allowed backbone clashes. The molecular replacement was successful for three helices per asymmetric unit in the space group P61 with a Z-score of 14.9 and a Log Likelihood Gain of 195. The Matthews coefficient was determined to be 3.65 which correspond to a solvent content of 65 %. The molecular replacement solution was used as input for the Auto Build feature of Phenix,68 followed by refinement in Refmac.66 Fo-Fc and 2Fo-Fc electron density maps generated with the CCP4 map utility FFT and with the mtz phase file in Coot50 were used for iterative building in of side chains, Zn(II) ions, and water molecules. The structure was refined to 2.15 Å resolution (Rworking = 21.9 %, Rfree = 26.4 %). The validity of the model was verified with a composite omit map generated in CNS.69 The coordinates and structure factors of CSL19C have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the ID code 2X6P. The data processing and refinement statistics for CSL9C and CSL19C are given in Table S1 and S2 in the Supporting Information. Figures were generated in Pymol.70 Angles between thiol plane of CSL19C and planes formed by the Cγ atoms of Leu 16 and Leu 23 were measured using the program Mercury from Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center.71

UV-Vis and 199Hg NMR Spectroscopy

To remove ubiquitous Zn(II) from solution, peptide stock solutions and buffers were prepared in deionized water treated with Chelex-100 resin (BioRad). All plasticware and glassware were soaked in 5 mM EDTA overnight followed by several thorough rinses with deionized water. Only metal free pipette tips (Fisher) were used. All solutions were purged with argon before use to minimize chances of Cys oxidation. Peptide concentration was determined by quantization of Cys thiols using Ellman’s test.72 UV-Vis experiments were performed at room temperature on a Cary 100 Bio spectrophotometer. Quartz cuvettes of path length 1 mm and 1 cm were used for the experiments at pH 6.5 and 8.6, respectively. Zn(II) titrations were performed by adding aliquots of 1M stock solution of Zn(OAc)2 to solutions containing 2.5 mM CSL9C and 50 mM MES buffer at pH 6.5 and 1 equivalents of HgCl2 (per trimer). Appropriate background spectrum was subtracted prior to addition of HgCl2. Hg(II) titrations were performed by adding aliquots of 7.37 mM stock solution of HgCl2 to solutions containing 2.5 mM CSL9C, 50 mM MES buffer at pH 6.5 in the presence of 21 equivalents of Zn(OAc)2 (per monomer) and with no Zn(II) present. For experiments at pH 8.6 same stock solution of HgCl2 was added to solutions containing 10 μM CSL9C, 50 mM CHES buffer in the presence and absence of 30 μM Zn(OAc)2. Direct Hg(II) titration data were analyzed by non-linear least squares fits to the equation similar to what has been described previously35,58:

where A is the observed absorbance on addition of Hg(II) to peptide solution, Kb is the binding constant of Hg(II) to be determined, Pt is the total concentration of peptide trimer, M0 is the concentration of Hg(II) used during titration, Δε is the difference molar extinction coefficient of the complex formed during titration and b is the path length of the cuvette. As the absorbance at 247 nm decreases in the presence of more than stoichiometric amount of Hg(II) due to formation of HgS2 in two stranded coiled coil, it was necessary to assume that the absorbance stays constant in order to fit the binding data. 199Hg NMR experiments were performed at room temperature on a Varian Inova 500 spectrometer (89.5 MHz for 199Hg) equipped with a 5 mm broadband probe as previously described.73 The samples for 199Hg NMR experiments contained a) 12 mM CSL9C, 4 mM 199Hg(NO3)2 (prepared from 91% isotopically enriched 199HgO, Oak Ridge), 252 mM Zn(OAC)2 and b) 14 mM CSL9C and 4.6 mM 199Hg(NO3)2. pH of both the samples were adjusted to 5 using concentrated solutions of KOH and HCl. pH of the solutions were also measured after the experiment. The data were analyzed using the software MestRe-C.74 The free induction decay was processed by applying a linear prediction from 1–32 points out of 120 basis points with a coefficient of 32 followed by zero filling and exponential line broadening of 200 Hz prior to Fourier transformation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

V.L.P. thanks the National Institute of Health for support of this research (ES012236) and J.A.S. thanks the University of Michigan, Center for Structural Biology.

Footnotes

Suporting Information Available: Helical wheel diagrams of (CSL9C)3, (CSL19C)3, location of Zn(II) ions at crystal packing interfaces of (CSL19C)3, orientation of Cys Sγ plane with respect to Leu 16 and Leu 23 layers of (CSL19C)3, the overlay of α-helical backbones of (CSL9C)3, (CSL19C)3, (CSL16LPen)3 and (CSL16DPen)3, UV-Vis titrations of Zn(II) to CSL9C and Hg(II), UV-Vis titrations of Hg(II) to CSL9C in the presence and absence of Zn(II) and 199Hg NMR spectra of CSL9C with 199Hg(II) in the presence and absence of Zn(II). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Contributor Information

Mr. Saumen Chakraborty, Department of Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (USA), Fax: (+1) 734-936-7628

Dr. Debra S. Touw, Department of Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (USA), Fax: (+1) 734-936-7628.

Dr. Anna F. A. Peacock, Department of Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (USA), Fax: (+1) 734-936-7628.

Prof. Jeanne Stuckey, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (USA)

Prof. Vincent L. Pecoraro, Email: vlpec@umich.edu, Department of Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (USA), Fax: (+1) 734-936-7628.

References

- 1.Regan L, DeGrado WF. Science. 1988;241:976–978. doi: 10.1126/science.3043666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeGrado WF, Wasserman ZR, Lear JD. Science. 1989;243:622–628. doi: 10.1126/science.2464850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryson JW, Betz SF, Lu ZX, Suich DJ, Zhou HX. Science. 1995;270:935–941. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuchscherer G, Scheibler L, Dumy P, Mutter M. Biopolymers. 1998;47:63–73. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1998)47:1<63::AID-BIP7>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baltzer L, Nilsson J. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2001;12:355–360. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeGrado WF. Nature. 2003;423:132–133. doi: 10.1038/423132a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu Y. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9930–9940. doi: 10.1021/ic052007t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koder RL, Dutton PL. Dalton Trans. 2006:3045–3051. doi: 10.1039/b514972j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan J, DeGrado WF. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2004;101:11566–11570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404387101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krizek BA, Merkle DL, Berg JM. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:937–940. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Struthers MD, Cheng RP, Imperiali B. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3073–3081. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Struthers MD, Cheng RP, Imperiali B. Science. 1996;271:342–345. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill CL, Steenkamp DJ, Holm RH, Singer TP. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 1977;74:547–551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibney BR, Rabanal F, Skalicky JJ, Wand AJ, Dutton PL. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4952–4960. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daugherty RG, Wasowicz T, Gibney BR, DeRose VJ. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:2623–2632. doi: 10.1021/ic010555a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonomo RP, Casella L, Gioia LD, Molinari H, Impellizzeri G, Jordan T, Pappalardo G, Rizzarelli E. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1997:2387–2389. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng RP, Fisher SL, Imperiali B. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1996;118:11349–11356. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenblatt MM, Wang JY, Suslick KS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;100:13140–13145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2231273100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider JP, Kelly JW. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:2533–2546. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Platt G, Chung C, Searle M. Chem Commun. 2001:1162–1163. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venkatraman J, Naganagowda GA, Sudha R, Balaram P. Chem Commun. 2001:2660–2661. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dieckmann GR, McRorie DK, Lear JD, Sharp KA, DeGrado WF, Pecoraro VL. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:897–912. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh D, Pecoraro VL. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:7902–7915. doi: 10.1021/ic048939z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovejoy B, Choe S, Cascio D, McRorie D, DeGrado W, Eisenberg D. Science. 1993;259:1288–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.8446897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dieckmann GR, McRorie DK, Tierney DL, Utschig LM, Singer CP, O’Halloran TV, Penner-Hahn JE, DeGrado WF, Pecoraro VL. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6195–6196. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Touw DS, Nordman CE, Stuckey JA, Pecoraro VL. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2007;104:11969–11974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701979104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KH, Cabello C, Hemmingsen L, Marsh ENG, Pecoraro VL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:2864–2868. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peacock AFA, Hemmingsen L, Pecoraro VL. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:16566–16571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806792105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iranzo O, Cabello C, Pecoraro VL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:6688–6691. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogihara NL, Weiss MS, DeGrado WF, Eisenberg D. Protein Sci. 1997;6:80–88. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrer B, McClure C, Penner-Hahn JE, Pecoraro VL. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:5422–5423. doi: 10.1021/ic0010149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrer BT, Harris NP, Balchus KE, Pecoraro VL. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14696–14705. doi: 10.1021/bi015649a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farrer B, Pecoraro VL. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2003;100:3760–3765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336055100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matzapetakis M, Farrer BT, Weng TC, Hemmingsen L, Penner-Hahn JE, Pecoraro VL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8042–8054. doi: 10.1021/ja017520u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matzapetakis M, Ghosh D, Weng TC, Penner-Hahn JE, Pecoraro VL. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:876–890. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matzapetakis M, Pecoraro VL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:18229–18233. doi: 10.1021/ja055433m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wendt H, Berger C, Baici A, Thomas RM, Bosshard HR. Biochem. 1995;34:4097–4107. doi: 10.1021/bi00012a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peacock AFA, Stuckey JA, Pecoraro VL. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2009;48:7371–7374. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calhoun JR, Nastri F, Maglio O, Pavone VAL, DeGrado WF. Peptide Sci. 2005;80:264–278. doi: 10.1002/bip.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lombardi A, Summa CM, Geremia S, Randaccio L, Pavone V, DeGrado WF. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2000;97:6298–6305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lahr SJ, Engel DE, Stayrook SE, Maglio O, North B, Geremia S, Lombardi A, DeGrado WF. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;346:1441–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costanzo LD, Wade H, Geremia S, Randaccio L, Pavone V, DeGrado WF, Lombardi A. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12749–12757. doi: 10.1021/ja010506x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maglio O, Nasti F, Pavone V, Lombardi A, DeGrado WF. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA. 2003;100:3772–3777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730771100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasternak A, Kaplan J, Lear JD, Degrado WF. Protein Science. 2001;10:958–969. doi: 10.1110/ps.52101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi W, Dong J, Scott RA, Ksenzenko MY, Rosen BP. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9291–9297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin YF, Yang J, Rosen BP. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16783–16791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700886200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matzapetakis M. Chemistry. University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2005. p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Touw DS. PhD Thesis. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramachandran GN, Ramakrishnan C, Sasisekharan V. J Mol Biol. 1963;7:95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(63)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Cryst D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ponder JW, Richards FM. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1987;193:775–791. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.NOMENCLATURE: While previously describing in detail the nomenclature for peptide modifications, we have not fully provided descriptors for metal complexation to these peptides. We will provide these definitions here with respect to Cd(II) and the exogenous ligand water; however, the nomenclature is general for any metal or non-protein bound ligand. We refer to an “apo peptide” as one which does not have metal in the designed metal coordination site within the hydrophobic interior of the coiled coils. We do not refer to an “apo peptide” to represent situations without the presence of any cofactors. Metals that may be bound non-specifically to the exterior hydrophilic residues are not considered to be metallated proteins/peptides in this context. d(II)(TRIL16C)3− indicates that Cd(II) is bound to the three stranded coiled coil; however, the metal coordination environment is either unknown or is a mixture of species (e.g., Cd(II)(TRIL16C)3− contains a 55:45 mixture of CdS3O and CdS3, respectively). When the metal is placed within brackets, as in [Cd(II)(H2O)](TRIL12AL16C)3−, we specify the coordination environment (in this case CdS3O) and the possible exogenous ligand (herewater). If the site has only protein ligands, then it would be represented as [Cd(II)](TRIL16Pen)3−. At low pH, one can encounter the situation where the cysteine sulfurs are protonated and may, or may not, be directly coordinated to the metal. In this case, we indicate this situation as [Cd(II)](TRIL16Pen[S,(SH)2])3− in which one cysteine is bound as a thiolate and the remaining two cysteines are protonated. When a peptide contains more than one binding site, we use the above nomenclature, but specify which site is being discussed by adding a superscript outside of the bracket to indicate the amino acid residues coordinating the specific metal (e.g., [Cd(II)]16[Cd(II)(H2O)]30(GRANDL16PenL26AL30C)3−2). Finally for cases where dual site peptides exhibit specificity for metal complexation, we will utilize [apo] to designate an empty site (e.g., [apo]16[Cd(II)(H2O)]30(GRANDL16PenL26AL30C)3−).

- 53.Berg JM. Acc Chem Res. 1995;28:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Logan DT, deMare F, Persson BO, Slaby A, Sjoberg BM, Nordlund P. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10798–10807. doi: 10.1021/bi9806403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andersson ME, Hogbom M, Rinaldo-Matthis A, Andersson KK, Sjoberg BM, Nordlund P. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1999;121:2346–2352. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Atta M, Nordlund P, Aberg A, Eklund H, Fontecave M. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:20682–20688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iranzo O, Thulstrup PV, Ryu SB, Hemmingsen L, Pecoraro VL. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:9178–9190. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iranzo O, Ghosh D, Pecoraro VL. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9959–9973. doi: 10.1021/ic061183e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bertini ISA, Sigel H. Handbook of Metalloproteins. Marcel Dekker Inc; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ebbing DD, Gammon SD. General Chemistry. 8. Houghton Mifflin; New York, Boston: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pecoraro VLP, Anna FA. Bioinorganic Chemistry. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2009. Iranzo Olga; Luczkowski Marek; pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan WC, White PD. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. In: Methods in Enzymology: Macromolecular Crystallography, part A. Carter CWJ, Sweet RM, editors. Vol. 276. Academic Press; New York: 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Potterton E, Briggs P, Turkenburg M, Dodson E. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 2003;59:1131–1137. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903008126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PV, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Acta Cryst D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; Palo Alto, California, USA: 2005. http://www.pymol.org. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Macrae CF, Bruno IJ, Chisholm JA, Edgington PR, McCabe P, Pidcock E, Rodriguez-Monge L, Taylor R, van de Streek J, Wood PA. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2008;41:466–470. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ellman GL. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Luczkowski M, Stachura M, Schirf V, Demeler B, Hemmingsen L, Pecoraro VL. Inorganic Chemistry. 2008;47:10875–10888. doi: 10.1021/ic8009817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cobas C, Cruces J, Sardina FJ. 2.3. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela; Spain: 2000. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.