Regulatory T cells control the in vivo expansion and response of antigen-specific CD4 T cell in an injury-dependent manner.

Keywords: inflammation, immunization, danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), SIRS, CARS

Abstract

Injury initiates local and systemic host responses and is known to increase CD4 Treg activity in mice and humans. This study uses a TCR transgenic T cell adoptive transfer approach and in vivo Treg depletion to determine specifically the in vivo influence of Tregs on antigen-driven CD4 T cell reactivity following burn injury in mice. We report here that injury in the absence of recipient and donor Tregs promotes high antigen-driven CD4 T cell expansion and increases the level of CD4 T cell reactivity. In contrast, CD4 T cell expansion and reactivity were suppressed significantly in injured Treg-replete mice. In additional experiments, we found that APCs prepared from burn- or sham-injured, Treg-depleted mice displayed significantly higher antigen-presenting activity than APCs prepared from normal mice, suggesting that Tregs may suppress injury responses by controlling the intensity of APC activity. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Tregs can actively control the in vivo expansion and reactivity of antigen-stimulated, naïve CD4 T cells following severe injury.

Introduction

A primary task of the immune system is to protect the host from infection and disease. However, the immune system also plays a vital role in controlling the host response to the tissue damage and cell death that occurs during burn and traumatic injuries, infections, cancer, and autoimmune responses. In the case of injury caused by major trauma or burns, the host immune response is triggered by extensive tissue damage rather than a pathogen or tumor cells. Consequently, we believe that injury may evoke a unique type of an immune response to specifically help protect the injured host from excessive inflammation and continued tissue destruction. In support of this hypothesis, it is generally agreed that injury promotes a dynamic shift in innate and adaptive immune system phenotypes, whereby the innate system displays a proinflammatory phenotype, and the adaptive system displays a counter-inflammatory phenotype [1–4].

These conclusions concerning the host response to injury are drawn from clinical observational studies and controlled animal experiments, which clearly indicate that cells and mediators of the innate and adaptive immune systems respond to severe injury [5–13]. Innate immune cells show a progressive increase in inflammatory behavior characterized by enhanced cellular reactivity to TLR agonists and increased host responsiveness to infectious challenge [14, 15]. We and others have described this heightened innate system response that occurs after injury as the “two-hit” response [1, 16]. This inflammatory condition that arises post-injury is also referred to as the systemic inflammatory response syndrome [17]. In marked contrast to the innate response to injury, the adaptive immune system displays a counter-inflammatory phenotype characterized as increased Th2-type cytokine production, enhanced Treg activity, and reduced Th1-type reactivity [18–23]. We believe that it is this injury-induced imbalance between innate and adaptive immune function that predisposes the injured patient to developing infections and inflammation-mediated complications following severe injury or major surgery.

As enhanced CD4+CD25+ Treg potency has been documented to occur in burn-injured mice and in trauma patients, the influence of injury on Treg activation and function has become a central focus of our research efforts [18, 23]. Several fundamental observations concerning the effects of injury on Tregs suggested to us that Tregs might be an injury-responsive immune cell subset. First, we found that the enhanced Treg activity of CD25+CD4 T cells from burn-injured, as compared with sham-injured, mice was restricted to the LNs draining the injury site [23]. This implies that Tregs might be activated locally, rather than systemically, by burn injury. Second, we found that the injury-induced increase in Treg potency was significant at Day 7 but not Day 1 after injury, suggesting that the Treg response may be a developed immune response similar to what occurs following immunization [23]. Third, we reported that a subset of CD4 T cells with phenotypic similarity to Tregs—CD25+ and CD152+—was detected as undergoing an early activation and proliferative response in the LNs but not spleen of burn-injured mice at 12 h post-injury [24]. Taken together, these observations form the foundation for the hypothesis that Tregs are activated by injury and may act to suppress CD4 T cell responses in an injury-specific manner.

This study uses DO-11 TCR transgenic mice and an adoptive transfer approach to determine if Tregs control antigen-driven CD4 T cell reactivity following burn injury [25]. DO-11 TCR transgenic mice were used as a source of donor CD4 T cells for this study, as in addition to having a high percentage of CD4 T cells expressing TCR with specificity to OVA323–339, ∼10% of the transgenic CD4 T cells expresses phenotypic markers indicative of natural Tregs, cell surface CD25, and the FoxP3 [26]. This provided us the opportunity to investigate whether the presence or absence of DO-11 Tregs in an adoptive transfer mouse injury model might influence the activation and proliferation of conventional (non-Treg) DO-11 T cells. The findings reported here indicate that Tregs can efficiently limit the in vivo expansion and activation of antigen-specific CD4 T cells following injury. Although this study uses the transgenic CD4 T cells as a way to study Treg effects on naïve CD4 T cell reactivity, we believe the findings reported here have wider implications and suggest that Treg activation might be a fundamental feature of the natural host response to severe injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Five-week-old BALB/c mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). DO-11 transgenic mice, originally obtained from Dr. Kenneth Murphy (Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA), were maintained as a breeding colony in our animal facility [27]. Transgene-positive mice were identified by staining 0.1 ml tail blood samples with anti-CD4 Ab and the DO-11 TCR-specific mAb (clone KJ-126.1) [28]. All mice were maintained in our accredited virus-Ab-free animal facility in accordance with the guidelines of the Harvard Medical School Standing Committee on Animal Research (Boston, MA, USA). The BALB/c mice used in these studies were acclimated for at least 1 week before being used for experiments at 6–9 weeks of age.

Reagents

Fluorescently labeled Abs for flow cytometry, including anti-CD4, -CD80, and -CD86, were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). The FcR-blocking reagent, TruStain fcX™ anti-CD16/32 Ab, was also purchased from BioLegend. Biotin-labeled anti-CD25 Ab was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The anti-DO-11 TCR mAb, clone KJ-126.1, and the anti-FoxP3 mAb, clone FkJ-16 s, were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). The OVA323–339 ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR used in these studies was custom-made for us by New England Peptide (Gardner, MA, USA). Mouse pan T magnetic beads used to prepare T cell-depleted spleen cells and the Vybrant CFDA cell tracer kit to label purified CD4+ DO-11 T cells were purchased from Invitrogen. Culture medium referred to as C5 was prepared by supplementing RPMI 1640 with 5% heat-inactivated FCS, 1 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 μM nonessential amino acids, 10 mM HEPES, penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone, and 2.5 × 10−5 β-ME, all purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA).

Mouse injury model

The mouse burn injury protocol, approved by the Harvard Medical School Standing Committee on Animal Research, was performed as described previously [29]. In brief, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection with keta-mine (175 mg/kg; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA, USA) and xylazine (20 mg/kg; Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, IA, USA). The dorsal fur was shaved, and the mouse was placed in an insulated plastic mold to expose 25% of its total body surface area. The exposed dorsum was then exposed to 90°C water for 9 s. This treatment causes full-thickness injury to the skin and is, therefore, considered to be an anesthetic injury as a result of complete damage of the nerve cells at the injury site. Thus, mice do not require post-burn analgesic treatment. The mortality of this injury protocol is routinely <5%. Sham (control) mice were treated exactly as burn mice, except mice were exposed to isothermic water. Immediately after the procedure, mice were resuscitated by an i.p. injection of 1 ml pyrogen-free normal saline.

Purification of DO-11 TCR transgenic CD4- and CD25-depleted CD4 T cells

Male DO-11 transgenic mice were killed to harvest LNs—inguinal, axillary, brachial, and cervical—and spleens. Following mincing to prepare single cell suspensions, RBCs were lysed using RBC lysis buffer, and cell suspensions were washed once in C5 medium by centrifugation (250 g for 10 min). We purified CD4+ T cells by a negative-selection approach using Miltenyi MACS CD4 T cell isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). CD25-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells were prepared by positive depletion using biotin-labeled anti-CD25 mAb (clone PC-61), anti-biotin Ab-coupled Miltenyi MACS beads, and MACS column depletion. For adoptive transfer, anesthetized mice were given 5 × 106 cells by intracardiac injection.

Anti-CD25 Ab treatment for in vivo Treg depletion/deactivation

The mAb, clone PC-61, which is specific for mouse CD25, was used to deplete and deactivate Tregs in mice [30], and mice were treated with anti-CD25 mAb by i.p. injection in 0.25 ml pyrogen-free saline 3 days prior to performing experiments. Preliminary studies were performed to determine the minimal, optimal dose for Treg depletion and deactivation. We determined 1 mg/kg to be the minimal effective dose for efficient in vivo CD25+ T cell depletion for at least 10 days without having measureable effects on normal T cell activation (see Fig. 2).

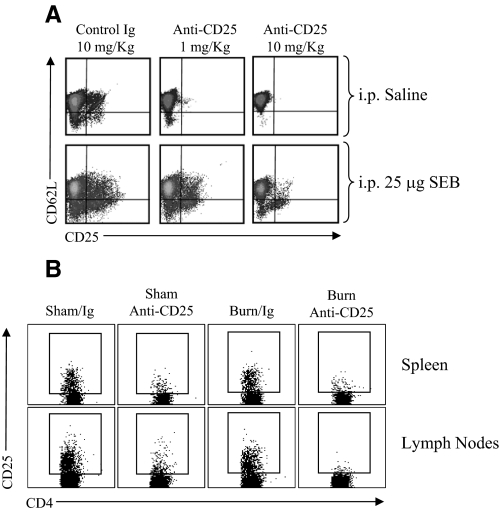

Figure 2. Optimization of an in vivo Treg-depletion protocol.

Mice were treated by i.p. injection with a low (1 mg/kg) or high (10 mg/kg) dose of anti-CD25 mAb (clone PC-61) or control rat IgG. Three days later, mice were challenged by i.p. injection with 25 μg SEB superantigen or saline to test for in vivo CD4 T cell activation capacity. (A) The FACS plots illustrate the level of CD25 and CD62L expression on CD4 T cells prepared from the LNs and spleen of mice at 48 h after SEB treatment. Activated CD4 T cells are identified by low CD62L and induced CD25 expression. These FACS plots are representative of two experiments; n = 3 mice/group. (B) The FACS plots illustrate the extent of CD25+CD4+ T cell depletion in the spleen and LNs of sham and burn mice at 10 days after i.p. treatment with 1 mg/kg anti-CD25 mAb or control rat IgG. These FACS plots are representative of three experiments; n = 4 mice/group.

Preparation of immune cell suspensions from LNs and spleen

Recipient mice were killed at 7 days after sham or burn injury. Their LNs—inguinal, axillary, and brachial—and spleens were harvested and minced in C5 medium on sterile, stainless-steel mesh to disperse the tissue and to prepare single cell suspensions. After sieve-filtering to remove debris (cell strainer, BD Falcon, Bedford, MA, USA), cell suspensions were washed twice in C5 medium. Cells were then plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well in a 96-well round-bottom cell culture plate (Costar, Corning, NY, USA). LNs and spleen cell suspensions were stained for cell surface markers by flow cytometry using FITC, PE, PE-Cy5.5, or allophycocyanin-labeled Abs specific for CD4, the DO-11 transgenic TCR (KJ-126.1), CD25, CD11c, F4/80, CD80, or CD86. Intracellular staining for the FoxP3 transcription factor was performed using anti-FoxP3-specific mAb (clone FJK-16, eBioscience) and the fix/perm buffer reagents (BioLegend) to stain cells for intracellular antigen detection.

Costimulatory molecule expression on macrophages and DCs

At 1 or 7 days after sham or burn injury, LNs or spleen cells from individual mice were stained with FITC-labeled Abs specific for F4/80 or CD11c to identify macrophages or DCs and counterstained with PE-labeled Abs specific for CD80 or CD86. Changes in costimulatory molecule expression were judged by FACS analysis using the CellQuest Pro software program (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Ex vivo cell cultures

LNs or spleen cell suspensions prepared from recipient sham or burn mice were cultured at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well of a 96-well round-bottom plate (Costar) in a final volume of 0.2 ml. Differing concentrations of OVA323–339 peptide (0, 0.01, 0.1, or 1 μg/ml final concentration) were added to individual wells. Supernatants were harvested 48 h later and tested for IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13 by our custom-made Luminex multiplex cytokine-detection bead assay platform using a Luminex 200 instrument (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX, USA). These Luminex bead multiplex cytokine assays had a detection sensitivity range of 5–25,000 pg/ml. For in vitro antigen-presentation assay, DO-11 T cells were mixed with T cell-depleted spleen cells, prepared by magnetic bead-mediated depletion, which was accomplished by incubating spleen cells with pan T cell-specific magnetic beads for 45 min at 4°C, followed by magnet exposure for 4 min. Specifically, purified CD4+CD25– T cells (2×105 cells) were cultured with T cell-depleted spleen cells (5×104 cells) and increasing doses of OVA323–339 peptide (0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μg/ml) in wells of a 96-well round-bottom plate. After 48 h, supernatants were harvested and tested for cytokine levels by Luminex multiplex cytokine assays.

Statistical analysis

The results presented in the study were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey multiple comparison tests using Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Optimization of a Treg-deficient mouse adoptive transfer model

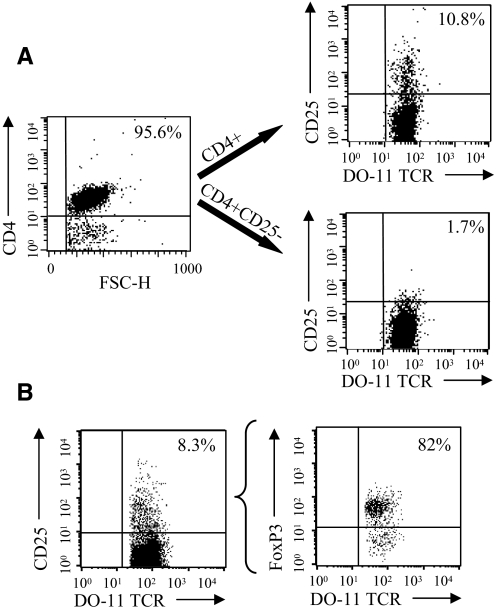

Prior to performing these CD4 T cell adoptive transfers, we carried out preliminary experiments to validate our CD4 T cell purification and CD25+CD4 T cell depletion procedures. We also wished to optimize an in vivo method for generating Treg-deficient mice by anti-CD25 Ab treatment. To prepare T cells for adoptive transfer, we used a magnetic bead-sorting approach with the objective to purify total “untouched” CD4+ DO-11 T cells and CD25-depleted CD4+ DO-11 T cells. These two CD4 T cell populations were prepared for adoptive transfer studies as a result of concern over the effect of cotransferring DO-11 Tregs. DO-11 CD4 T cells were sorted by negative selection, and CD25+ T cells were removed from total CD4 T cells by a positive-selection approach. As shown in Fig. 1A, this purification scheme allowed us to obtain highly purified CD4+ and CD4+CD25– T cells from DO-11 mice to be used in adoptive-transfer studies. As anticipated, 82% of the CD25+ DO-11 transgenic CD4 T cells expressed FoxP3, the most robust marker for Tregs (Fig. 1B). This finding confirmed that DO-11 mice do have a significant population of DO-11 TCR-expressing Tregs, which could influence the OVA323–339 peptide immunization response when cotransferred into Treg-depleted mice.

Figure 1. DO-11 CD4 T cell purification for adoptive transfer experiments and identification of CD4+CD25+ FoxP3+ DO-11 T cells.

LNs and spleen CD4 T cells were purified from DO-11 TCR transgenic mice by negative selection using Miltenyi MACS CD4 isolation kits. Purified CD4 T cells were depleted of CD25+ cells by biotinylated anti-CD25 mAb and anti-biotin-coupled Miltenyi MACS beads. (A) The FACS plots illustrate the purity of DO-11 TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells and CD25-depleted CD4 T cells that were prepared for the adoptive transfer studies described in this report. Purified CD4 T cells were stained with anti-DO-11 TCR mAb (clone KJ-126.1) and counterstained with anti-CD25 mAb. The percentages indicate the percent of CD25+CD4+ DO-11+ T cells in the indicated purified CD4 T cell preparations. FSC-H, Forward-scatter-height. (B) The FACS plots are included to demonstrate that a majority of the DO-11 CD4+CD25+ T cells expresses FoxP3 (82%). Purified DO-11 CD4 T cells were surface-stained with anti-DO-11 TCR mAb and anti-CD25 mAb and then stained to detect intracellular FoxP3 using anti-FoxP3 mAb (clone FKJ-16 s).

We next sought to determine the effectiveness of using anti-CD25 Ab treatment to deplete mice of CD25+ T cells. This same approach had been used by others to study Treg function in vivo, but as we wished to examine the influence of Tregs on antigen-driven T cell activation and expansion in vivo, we felt it necessary to carefully titrate the Ab treatment dose to the lowest possible level that causes CD25+CD4 T cell depletion without affecting the T cell activation process in immunized mice [30–32]. Therefore, the level of CD4+CD25+ T cell depletion, as well as the capacity to stimulate in vivo CD4 T cell responses, was evaluated in anti-CD25 mAb-treated mice. To test for in vivo T cell reactivity, mice were challenged with SEB superantigen, and T cell activation markers were measured 48 h later. We found that 1 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg anti-CD25 Ab treatment caused significant CD4+CD25+ T cell depletion. Mice that were treated with 1 mg/kg anti-CD25 mAb showed near-normal reactivity to challenge with SEB, as measured by the conversion of cell surface CD62L from high- to low-density flow cytometry staining (Fig. 2A). In contrast, mice that were given the higher dose of anti-CD25 Ab (10 mg/kg) responded poorly to SEB, which suggests that residual anti-CD25 Ab interfered with CD4 T cell activation or deleted, newly activated CD4+CD25+ T cells. We also found that giving mice higher than 1 mg/kg anti-CD25 Ab suppressed SEB-induced T cell activation (2.5 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg), and treatment with <1 mg/kg anti-CD25 Ab did not effectively deplete CD4+CD25+ T cells (data not shown). Thus, in all subsequent experiments, we used 1 mg/kg anti-CD25 Ab to generate Treg-deficient mice to minimize influencing the normal CD4 T cell activation process in vivo. The FACS plots shown in Fig. 2B illustrate the level of CD4+CD25+ T cell depletion achieved in the spleen and LNs (axillary, brachial, inguinal) at 10 days following anti-CD25 Ab treatment of sham- and burn-injured mice. These results indicate that Treg depletion by this method lasts for at least 10 days, the duration of our burn injury and immunization studies.

Tregs influence the expansion of antigen-specific CD4 T cells in injured mice

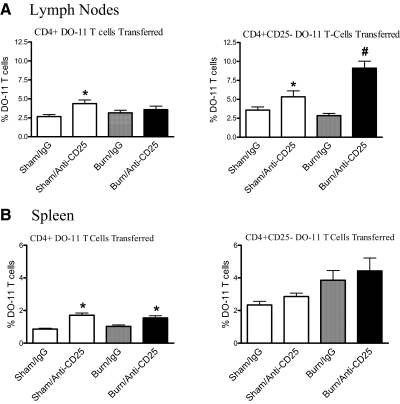

We reported previously that CD4+CD25+ T cells isolated from the LNs, but not spleen, of burn-injured mice showed higher Treg activity than those prepared from sham control mice [23]. This suggested to us that Tregs might actively control the activation and expansion of antigen-stimulated CD4 T cells following burn injury, especially in the LNs that drain the injury site. To test this possibility, groups of mice were treated with anti-CD25 mAb to deplete and inactivate Tregs or were given control rat IgG Ab. Three days later, mice received DO-11 CD4 T cells by adoptive transfer and were immunized s.c. with OVA323–339 peptide mixed 1:1 with IFA. The effect of injury and Treg depletion on antigen-specific CD4 T cell expansion in the LNs and spleen was then judged 7 days later by flow cytometry using a mAb (clone KJ-126.1) that specifically recognizes the DO-11 TCR. An additional variable was to transfer CD25-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells into recipient Treg-depleted or control mice to determine whether the cotransfer of DO-11 Tregs might affect antigen-induced CD4 T cell expansion in vivo. As shown in Fig. 3, DO-11 T cells expanded by 7 days after OVA323–339 peptide immunization, and Treg-depleted mice showed a higher level of antigen-induced CD4 T cell expansion than control, IgG-treated mice. We did not observe a significant difference in expansion between sham and burn groups when mice were given purified, total DO-11 CD4 T cells. In contrast, we observed a large burn injury-induced increase in DO-11 CD4 T cell expansion in the LNs of mice that were given Treg-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells. These data indicate that DO-11 T cells expanded to a significantly higher percentage in injured mice that received Treg-depleted DO-11 T cells and suggest that the cotransfer of DO-11 CD25+ T cells suppressed the antigen-induced expansion of CD4+ T cells following injury.

Figure 3. Injury enhances antigen-driven DO-11 CD4 T cell expansion in the LNs of Treg-deficient mice.

Mice received DO-11 CD4 T cells or CD25-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells by adoptive transfer. Mice underwent sham or burn injury and were immunized s.c. with 10 μg OVA323–339 peptide mixed 1:1 in IFA. Seven days later, LNs (A) and spleens (B) were harvested from individual mice to prepare cell suspensions to detect the in vivo expansion of DO-11 T cells (CD4+, KJ-126.1+). The results shown are representative of three experiments; n = 4 mice/group. *P < 0.05 sham or burn IgG-treated versus anti-CD25 Ab-treated mice. #P < 0.05 sham anti-CD25 versus burn anti-CD25 mAb-treated mice.

Adoptive transfer studies using CFSE-labeled DO-11 CD4+CD25– T cells were also performed to test whether we could detect a difference in antigen-induced proliferation by DO-11 T cells in Treg-depleted or Treg-replete sham and burn mice. In these experiments, we examined the percentage of transferred DO-11 T cells that proliferated in the LNs and spleen of mice by 36 h after OVA323–339 peptide immunization. The FACS plots shown in Fig. 4 illustrate that a relatively high percentage of DO-11 T cells proliferated in the LNs and spleens of immunized mice. The transferred DO-11 CD4 T cells proliferated multiple times (greater than two rounds of proliferation) by 36 h after immunization, and their proliferative response appeared to be synchronous. However, we did not detect significant differences in proliferation between Treg-depleted or control IgG-treated sham and burn mice. These findings suggest that Tregs suppress antigen-induced expansion but do not suppress the early proliferative response of antigen-stimulated CD4 T cells in burn-injured mice.

Figure 4. Treg depletion does not influence the early proliferation of DO-11 CD4 T cells in the LNs and spleens of OVA323–339 peptide-immunized sham or burn mice.

Groups of anti-CD25 mAb or control rat IgG-treated mice received CFSE-labeled, CD25-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells by adoptive transfer and underwent sham or burn injury. Mice were immunized s.c. with 10 μg OVA323–339 peptide mixed 1:1 in IFA at the time of injury. After 36 h, LNs and spleens were harvested from individual mice (n=4) to prepare cell suspensions. Cells were stained with allophycocyanin-labeled anti-CD4 Ab and PE-Cy5.5-labeled anti-DO-11 TCR mAb (clone KJ-126.1) to identify the transferred DO-11 CD4 T cells. (A) The FACS plots represent the CFSE intensity in gated CD4+/KJ126.1+ cells, and the boxed area within the FACS scatter plots identifies the DO-11 CD4 T cells that proliferated in response to immunization. FL1-H, Fluorescence 1-height. (B) The data graphs show the percentage of DO-11 CD4 T cells that proliferated in the LNs or spleen at 36 h after OVA323–339 peptide immunization. There were no significant differences between experimental groups.

Tregs control the level of CD4 T cell activation and reactivity following injury

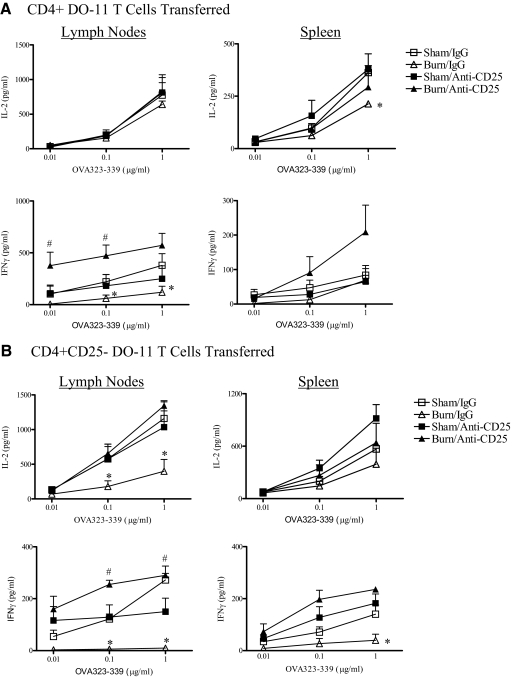

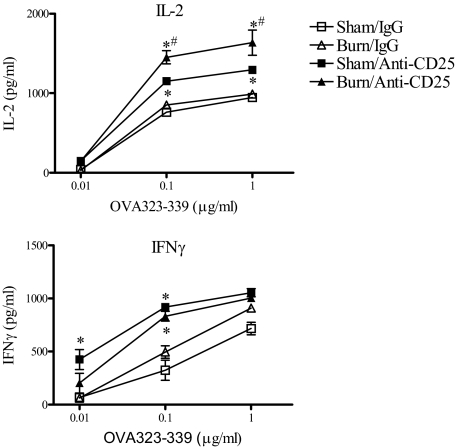

The increased DO-11 CD4 T cell expansion seen in burn-injured, Treg-deficient mice suggests that Tregs might govern the extent of CD4 T cell activation that occurs after injury. To address this possibility, we tested the ex vivo antigen response of adoptively transferred DO-11 T cells from groups of immunized sham and burn mice to test the effect of Treg depletion on antigen reactivity. LNs or spleen cells from recipient mice harvested at 7 days after sham or burn injury were cultured with titrated concentrations of OVA323–339 peptide (0.01, 0.1, 1 μg/ml), and cytokine production levels were measured. As shown in Fig. 5, LNs and spleen cells from burn-injured mice that received DO-11 CD4+ T cells or CD25-depleted DO-11 T cells produced significantly lower levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ than OVA323–339 peptide-stimulated cells from sham mice. In marked contrast, OVA323–339 peptide-stimulated LNs and spleen cells from Treg-depleted burn mice produced much higher levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ than cells from control burn mice. This enhanced OVA peptide response from Treg-depleted mice was evident at low peptide concentrations, indicating that Treg deficiency also led to an increase in antigen reactivity by the transferred DO-11 T cells. Mice given Treg-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells, as compared with total CD4 T cells, showed a similar burn-injury enhancement of OVA323–339 peptide reactivity. Interestingly, antigen-specific CD4 T cell responses were not markedly affected by Treg depletion in sham mice. Thus, Tregs appear to control CD4 T cell-dependent immune responses following injury and play a lesser role in modulating CD4 T cell responses in uninjured, immunized mice.

Figure 5. Treg depletion releases the injury-induced suppression of antigen-specific Th1 reactivity.

Groups of anti-CD25 mAb or control rat IgG-treated mice received DO-11 CD4 T cells or CD25-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells by adoptive transfer and underwent sham or burn injury. Mice were immunized s.c. with 10 μg OVA323–339 peptide mixed 1:1 in IFA at the time of injury. Seven days later, LNs and spleens were harvested from individual mice to prepare cell suspensions. Cells were cultured in the presence of the indicated concentrations OVA323–339 peptide (0.01, 0.1, 1 μg/ml), and supernatants were harvested 48 h later to be tested for IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13 levels by Luminex multiplex assays. Cells cultured without OVA323–339 peptide addition did not produce any detectable cytokines, and IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13 were not detected (<10 pg/ml) in culture supernatants. *, Significant differences between burn/IgG and sham/IgG groups and burn/IgG versus sham or burn anti-CD25 Ab-treated groups, P < 0.05; #significant difference between burn/anti-CD25 and sham/anti-CD25 treatment groups, P < 0.05. The results are representative of three independent experiments using four mice/group.

The effects of Treg depletion on APC function

As we found that Treg depletion reversed the injury-induced suppression of IL-2 and IFN-γ production, we next wanted to determine if Tregs might control CD4 T cell activation by influencing APC function. To address this question, spleen cells were harvested from normal or Treg-depleted sham and burn mice at 7 days post-injury. We prepared T cell-depleted splenic APCs, which were mixed with naïve, CD25-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells and OVA323–339 peptide. Supernatants were then tested for IL-2 and IFN-γ levels after 48 h in culture. We observed that splenic APCs prepared from anti-CD25 Ab-treated sham and burn mice were able to stimulate higher levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ at lower OVA peptide concentrations than splenic APCs from sham or burn control mice at 7 days after injury (Fig. 6). We also observed that APCs prepared from Treg-depleted burn mice stimulated significantly higher IL-2 production from OVA323–339 peptide-stimulated cells than APCs from Treg-depleted sham mice. These findings indicate that Treg deficiency caused a systemic increase in APC function. We noticed that these results from unimmunized mice contrasted with what we found in experiments where LNs or spleen cells from immunized, burn-injured mice showed markedly reduced IL-2 and IFN-γ production (Fig. 5). These opposing findings provide evidence to suggest that the suppressed Th1 reactivity following burn injury may happen by an antigen-dependent mechanism.

Figure 6. Treg depletion augments APC activity for naïve CD4 T cells.

Mice were treated with anti-CD25 mAb (clone PC-61) or control rat IgG. Three days later, mice underwent sham or burn injury, and then at 7 days post-injury, T cell-depleted spleen cells were prepared from the indicated groups of mice. These cells were tested for APC activity by mixing 5 × 104 T cell-depleted spleen cells with 2 × 105 CD25-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells and OVA323–339 peptide (0.01, 0.1, or 1 μg/ml). Supernatants were collected 48 h later and tested for IL-2 and IFN-γ levels. *Significant differences between IgG and anti-CD25 mAb groups, P < 0.05; #significant differences between sham and burn anti-CD25 mAb-treated groups, P < 0.05. The results represent the mean ± sem of three individual mice.

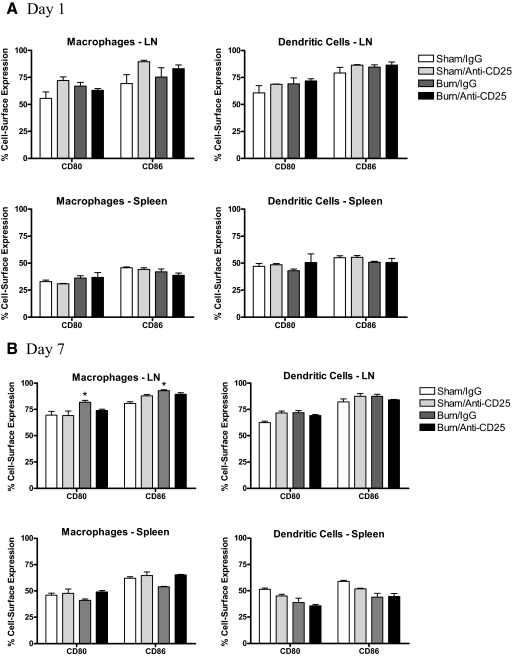

The increase in APC function observed in Treg-depleted sham and burn mice prompted us to determine if in vivo Treg depletion might affect the expression of the major costimulatory molecules, CD80 or CD86, on APCs. To test this possibility, LNs and spleens were prepared from anti-CD25 mAb or IgG-treated mice at 1 and 7 days after sham or burn injury and stained to measure CD80 or CD86 expression levels on macrophages and DCs. To our surprise, we found that Treg depletion did not markedly change the expression of CD80 or CD86 on macrophages or DCs in these immune tissues at Days 1 or 7 after burn injury (Fig. 7). Thus, the increased antigen-presenting activity and subsequent increase in CD4 T cell reactivity seen in Treg-depleted mice cannot be explained easily by changes in CD80 or CD86 expression levels on macrophages or DCs.

Figure 7. The effect of Treg depletion on CD80 and CD86 expression by LNs and spleen macrophages and DCs.

Mice were treated with anti-CD25 mAb (clone PC-61) or control rat IgG Ab. Three days later, mice underwent sham or burn injury, and at 1 or 7 days after injuries, LNs and spleen cells were prepared from the indicated groups of mice. Cells were surface-stained using FITC-labeled Abs specific for macrophages, anti-F4/80 mAb, or DCs and CD11c mAb and then counterstained with PE-labeled Abs specific for CD80 or CD86. The data represent the mean ± sem percent expression of CD80 or CD86 on live-gated F4/80+ or CD11c+ cells. *Significant differences between sham- and burn-injured groups; P < 0.05 for three mice/group.

DISCUSSION

It is now well established that Tregs regulate the development of autoimmune reactions and inflammatory diseases by defusing inflammation, deactivating APCs, and blocking CD4 and CD8 T cell reactivity [33–35]. These features of Treg biology were best-demonstrated in Treg-deficient mouse models [36, 37]. In general, Treg-deficient mice showed exacerbated, inflammatory-type reactions and heightened CD4 or CD8 T cell-mediated immune pathology [38]. These fundamental features of Tregs initially sparked our interest in testing whether they might be involved in controlling the host response to severe injury.

Our initial studies addressing the influence of injury on Tregs showed that burn injury could dramatically increase the potency of Tregs as determined by suppressing CD4 T cell proliferation in a standard Treg function assay [23]. In another study, we reported that burn-injured, CD4-deficient mice developed a higher inflammatory response phenotype, which could be reversed by the adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25+ T cells into CD4-deficient mice prior to burn injury [39]. Subsequently, other groups have reported and confirmed that other sorts of injuries to the eyes, kidney, liver, brain, heart, and skin could also activate Tregs and that Tregs appeared to limit the extent of tissue damage and inflammation [40–46]. These observations support the hypothesis that Tregs might represent an injury-responsive immune cell that functions to control the host response to tissue injury.

The work performed in this report centers on using a TCR transgenic mouse adoptive transfer experimental system to investigate how Tregs control antigen-specific CD4 T cell responses in injured mice. The advantage of performing adoptive transfer studies with CD4 T cells from TCR transgenic mice is that it allows for specific tracking of antigen-driven CD4 T cell responses in vivo [47]. Moreover, this CD4 T cell adoptive transfer approach used in combination with a Treg-depletion protocol allowed us to test whether Tregs can influence antigen immunization responses in sham- versus burn-injured, Treg-deficient and -replete mice. We report here several basic observations. First, we found that Treg-deficient, burn-injured mice showed an injury-dependent expansion of transferred CD4+CD25– DO-11 T cells in the LNs draining the injury site, whereas this did not occur in mice given total CD4+ DO-11 T cells by adoptive transfer. Second, we show that Treg depletion restored Th1-type cytokine responses in burn-injured mice, as characterized by normal and super-normal production of IFN-γ by OVA323–339 peptide-stimulated LNs or spleen cells. Third, we demonstrate that the suppressive effect of injury on antigen-specific CD4 T cell responses is dependent on the presence of functional Tregs at the time of injury. These findings are novel and provide new mechanistic insights into how injury suppresses CD4 T cell-mediated immune responses. These data also suggest that tissue injury and stress may act as physiological triggers for Treg activation and function.

As it is known that DO-11 TCR transgenic mice have a population of CD25+CD4 T cells with specificity for the OVA323–339 peptide, we reasoned that the cotransfer of contaminating DO-11 or non-TCR transgenic donor CD4+CD25+ would make the results of our adoptive transfer experiments difficult to interpret [26, 48]. We demonstrate here that Treg-depleted recipient burn mice given total CD4 T cells by adoptive transfer showed no significant burn increase in DO-11 T cell expansion at 7 days after injury and immunization. In contrast, Treg-depleted recipient burn mice given CD25-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells displayed a remarkable increase in DO-11 T cell expansion in the LNs as compared with similarly treated sham mice. These results provide new evidence to indicate that antigen-driven CD4 T cell activation and proliferation are augmented following injury in the absence of endogenous (recipient) and transferred DO-11 Tregs. Moreover, the effect of Treg depletion on DO-11 T cell expansion appears to be injury-specific and localized to those LNs that drain the injury site. Taken together, these data are consistent with the idea that Tregs may be activated by an injury-specific mechanism, which makes them more effective at blocking antigen-driven CD4 T cell activation and expansion. As Tregs control the development of self-antigen-driven autoimmune pathology, we speculate that the enhanced ability of Tregs to control CD4 T cell proliferation following injury may have evolved to protect the host from responding to endogenous antigens or factors that may be released by the extensive tissue damage. Antigen-independent factors could also influence Treg activity [49]. A significant future research challenge will be to determine if Tregs are activated by injury by antigen-dependent or -independent mechanisms.

In addition to testing for differences in DO-11 CD4 T cell expansion in immunized groups of sham or burn Treg-deficient or -replete mice, we tested whether Tregs might influence the early antigen-driven T cell activation and proliferation process. This was accomplished by performing adoptive transfer experiments using CFSE-labeled, CD25-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells transferred into anti-CD25 Ab or control IgG-treated sham or burn mice and measuring changes in the CFSE fluorescence in DO-11 CD4 T cells in the LNs or spleens of OVA323–339 peptide-immunized mice. This approach is a popular method to determine antigen-driven CD4 T cell proliferation in vivo. Nevertheless, the major limitation of using this method to measure in vivo CD4 T cell proliferation is that the studies can only be conducted at early time-points postimmunization. This is because the assay measures the dilution of CFSE fluorescence in proliferated cells, and after multiple rounds of proliferation, the fluorescence CFSE label is low. Accordingly, these studies were performed at 36 h after adoptive transfer and immunization, as we found that CFSE staining was of too low intensity at later time-points after immunization. In contrast to what we found at 7 days after immunization, we observed that DO-11 T cell proliferation was not significantly different between sham- and burn-injured mice. Surprisingly, we also found that Treg deficiency did not influence the early proliferative response to immunization in sham or burn mice. We interpret these findings to suggest that the early proliferative response to immunization is not affected by burn injury or Tregs. Instead, Tregs have a greater influence on antigen-driven CD4 T cell expansion.

We also found that burn injury caused a significant reduction in antigen-induced cytokine production. This was evident in experiments where DO-11 T cells from burn mice produced significantly lower IFN-γ in response to OVA323–339 peptide stimulation than those prepared from sham mice. This finding agrees with the results of prior studies addressing the phenotypic effects of injury on Th1 versus Th2 responses in vivo [19, 50]. However, the novel feature of this study is the observation that eliminating Tregs in mice significantly enhanced the antigen reactivity of CD4 T cells. This is supported by the observation that ex vivo OVA323–339 peptide-stimulated LNs and spleen cells from burn-injured, Treg-deficient mice produced markedly higher levels of IFN-γ than similarly prepared cells from control, Treg-replete mice. Taken together, these findings suggest that Tregs play an important role in controlling the intensity of conventional antigen-driven CD4 T cell responses following severe injury.

One aspect of this study that was difficult to test fully was the influence of injury on DO-11 T cells in unimmunized mice. This is because without OVA323–339 peptide immunization following adoptive transfer of DO-11 T cells, there are few DO-11 T cells left in the LNs and spleen of recipient mice at 7 days post-transfer (data not shown). However, we have reported in a prior study that unimmunized, burn-injured TCR transgenic mice showed no apparent signs of suppressed Th1 responses [51]. In that study, immunized or unimmunized DO-11 and/or TCR transgenic mice underwent sham or burn injury, and 7 days later, LNs and spleen cells were tested for their ability to produce Th1 versus Th2 cytokines in response to OVA323–339 or PCC peptide stimulation, respectively. We found that cells from unimmunized DO-11 and/or mice produced higher levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ in response to peptide stimulation than similarly prepared cells from immunized TCR transgenic mice. At the time that those studies were performed, we reasoned that injury did not suppress CD4 T cell responses in vivo in the absence of endogenous antigen stimulation. As mice do not have endogenous OVA or PCC, we also concluded that self-antigens may be central to driving the phenotypic changes in CD4 T cells seen after injury. The data presented here also suggest that antigen stimulation may be required for Treg activation, as we failed to see increased DO-11 CD4 T cell expansion in the LNs of burn mice given DO-11 CD4 T cells as opposed to Treg-depleted DO-11 CD4 T cells. The results of a related study also showed that DO-11 Tregs had the capacity to control the development of oral tolerance against T cell-mediated colitis by an antigen-specific mechanism [48]. Thus, further exploitation of TCR transgenic mouse models will help us better define the antigen dependence of injury-induced changes in Treg function. This work presented in this report does not contrast with the idea that burn injury results in the release of molecules from damaged cells, which can be immunostimulatory [52, 53]. As discussed by Seong and Matzinger [54], these molecules, which are released from damaged cells and tend to be hydrophobic, could act as danger or alarm signals to alert the immune system. These molecules were given the name DAMPs, in keeping with the terminology first proposed by Medzhitov and Janeway [55], who coined the term PAMPs as molecules from pathogens that are recognized by innate immune receptors. Although most investigators believe that innate immune cells are the primary cell types that recognize and respond to DAMPs, Tregs may also be activated by DAMPs. As Tregs have been shown to express TLRs, which are PRRs for DAMPs and PAMPs, TLR signaling might play a contributory role in driving the Treg-mediated Th1 suppression, which we describe in this report [56, 57]. We intend to devote future research efforts toward identifying danger or alarm signals that might influence the activation and function of Tregs.

In summary, we report that Tregs can control the development of antigen-specific CD4 T cell responses in mice. Injured mice with normal levels of Tregs showed a marked suppression of CD4 T cell expansion and Th1-type cytokine production, and Treg-deficient mice demonstrated higher in vivo CD4 T cell expansion and augmented cytokine responses to ex vivo antigen stimulation. We interpret these findings to indicate that Tregs respond to injury and that they act to suppress conventional/naïve CD4 T cell activation. We speculate that tissue antigens that are released by injury may drive this injury-induced Treg activation. An increased understanding of what factors initiate the activation of Tregs will provide us with a better understanding of the how injury influences the mammalian immune system. Thus, a future challenge will be to define whether injury-specific Treg activation is a result of self-antigen recognition or antigen-independent mechanisms, such as T cell costimulatory pathways, cytokines, stress-induced factors, or DAMPs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant numbers 5RO1GM057664 and 5R01GM035633. This project was also supported by the Brook Fund for Surgical Research and Julian and Eunice Cohen Research Fund.

Footnotes

- C5

- complete 5

- CD62L

- CD62 ligand

- DAMP

- danger-associated molecular pattern

- FoxP3

- forkhead box protein P3 transcription factor

- OVA323–339

- OVA 323–339 aa peptide

- PCC

- pigeon cytochrome C

- SEB

- Staphylococcal enterotoxin B

- Treg

- regulatory T cell

AUTHORSHIP

All listed authors contributed significantly to the data presented in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Moore F. A., Moore E. E., Read R. A. (1993) Postinjury multiple organ failure: role of extrathoracic injury and sepsis in adult respiratory distress syndrome. New Horiz. 1, 538–549 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baue A. E., Durham R., Faist E. (1998) Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), multiple organ failure (MOF): are we winning the battle? Shock 10, 79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baue A. E. (2006) MOF, MODS, and SIRS: what is in a name or an acronym? Shock 26, 438–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bone R. C. (1996) Sir Isaac Newton, sepsis, SIRS, and CARS. Crit. Care Med. 24, 1125–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kirchhoff C., Biberthaler P., Mutschler W. E., Faist E., Jochum M., Zedler S. (2009) Early down-regulation of the pro-inflammatory potential of monocytes is correlated to organ dysfunction in patients after severe multiple injury: a prospective cohort study. Crit. Care 13, R88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heizmann O., Koeller M., Muhr G., Oertli D., Schinkel C. (2008) Th1- and Th2-type cytokines in plasma after major trauma. J. Trauma 65, 1374–1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levy R. M., Prince J. M., Yang R., Mollen K. P., Liao H., Watson G. A., Fink M. P., Vodovotz Y., Billiar T. R. (2006) Systemic inflammation and remote organ damage following bilateral femur fracture requires Toll-like receptor 4. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 291, R970–R976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kohl B. A., Deutschman C. S. (2006) The inflammatory response to surgery and trauma. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 12, 325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schwacha M. G. (2003) Macrophages and post-burn immune dysfunction. Burns 29, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murphy T., Paterson H., Rogers S., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (2003) Use of intracellular cytokine staining and bacterial superantigen to document suppression of the adaptive immune system in injured patients. Ann. Surg. 238, 401–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adams J. M., Hauser C. J., Livingston D. H., Lavery R. F., Fekete Z., Deitch E. A. (2001) Early trauma polymorphonuclear neutrophil responses to chemokines are associated with development of sepsis, pneumonia, and organ failure. J. Trauma 51, 452–456, discussion 456–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Faist E., Schinkel C., Zimmer S., Kremer J. P., Alkan S., Rordorf C., von Donnersmarck H., Schildberg F. W. (1993) The influence of major trauma on the regulatory levels of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-2 in human mononuclear leukocytes. Zentralbl. Chir. 118, 420–431 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miller C. H., Quattrocchi K. B., Frank E. H., Issel B. W., Wagner F. C., Jr. (1991) Humoral and cellular immunity following severe head injury: review and current investigations. Neurol. Res. 13, 117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schwacha M. G., Somers S. D. (1999) Thermal injury-induced enhancement of oxidative metabolism by mononuclear phagocytes. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 20, 37–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paterson H. M., Murphy T. J., Purcell E. J., Shelley O., Kriynovich S. J., Lien E., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (2003) Injury primes the innate immune system for enhanced Toll-like receptor reactivity. J. Immunol. 171, 1473–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sauaia A., Moore F. A., Moore E. E., Lezotte D. C. (1996) Early risk factors for postinjury multiple organ failure. World J. Surg. 20, 392–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levy M. M., Fink M. P., Marshall J. C., Abraham E., Angus D., Cook D., Cohen J., Opal S. M., Vincent J. L., Ramsay G. (2003) 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive Care Med. 29, 530–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. MacConmara M. P., Maung A. A., Fujimi S., McKenna A. M., Delisle A., Lapchak P. H., Rogers S., Lederer J. A., Mannick J. A. (2006) Increased CD4+ CD25+ T regulatory cell activity in trauma patients depresses protective Th1 immunity. Ann. Surg. 244, 514–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guo Z., Kavanagh E., Zang Y., Dolan S. M., Kriynovich S. J., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (2003) Burn injury promotes antigen-driven Th2-type responses in vivo. J. Immunol. 171, 3983–3990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zedler S., Faist E., Ostermeier B., von Donnersmarck G. H., Schildberg F. W. (1997) Postburn constitutional changes in T-cell reactivity occur in CD8+ rather than in CD4+ cells. J. Trauma 42, 872–880, discussion 880–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kelly J. L., Lyons A., Soberg C. C., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (1997) Anti-interleukin-10 antibody restores burn-induced defects in T-cell function. Surgery 122, 146–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mack V. E., McCarter M. D., Naama H. A., Calvano S. E., Daly J. M. (1996) Dominance of T-helper 2-type cytokines after severe injury. Arch. Surg. 131, 1303–1308, discussion 1308–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ni Choileain N., MacConmara M., Zang Y., Murphy T. J., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (2006) Enhanced regulatory T cell activity is an element of the host response to injury. J. Immunol. 176, 225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Purcell E. M., Dolan S. M., Kriynovich S., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (2006) Burn injury induces an early activation response by lymph node CD4+ T cells. Shock 25, 135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kearney E. R., Pape K. A., Loh D. Y., Jenkins M. K. (1994) Visualization of peptide-specific T cell immunity and peripheral tolerance induction in vivo. Immunity 1, 327–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walker L. S., Chodos A., Eggena M., Dooms H., Abbas A. K. (2003) Antigen-dependent proliferation of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 198, 249–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hsieh C. S., Heimberger A. B., Gold J. S., O'Garra A., Murphy K. M. (1992) Differential regulation of T helper phenotype development by interleukins 4 and 10 in an α β T-cell-receptor transgenic system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 6065–6069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haskins K., Kubo R., White J., Pigeon M., Kappler J., Marrack P. (1983) The major histocompatibility complex-restricted antigen receptor on T cells. I. Isolation with a monoclonal antibody. J. Exp. Med. 157, 1149–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ni Choileain N., Macconmara M., Zang Y., Murphy T. J., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (2006) Enhanced regulatory T cell activity is an element of the host response to injury. J. Immunol. 176, 225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kohm A. P., McMahon J. S., Podojil J. R., Begolka W. S., DeGutes M., Kasprowicz D. J., Ziegler S. F., Miller S. D. (2006) Cutting edge: anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody injection results in the functional inactivation, not depletion, of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 176, 3301–3305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ko K., Yamazaki S., Nakamura K., Nishioka T., Hirota K., Yamaguchi T., Shimizu J., Nomura T., Chiba T., Sakaguchi S. (2005) Treatment of advanced tumors with agonistic anti-GITR mAb and its effects on tumor-infiltrating Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 202, 885–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McHugh R. S., Shevach E. M. (2002) Cutting edge: depletion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is necessary, but not sufficient, for induction of organ-specific autoimmune disease. J. Immunol. 168, 5979–5983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sakaguchi S., Sakaguchi N., Shimizu J., Yamazaki S., Sakihama T., Itoh M., Kuniyasu Y., Nomura T., Toda M., Takahashi T. (2001) Immunologic tolerance maintained by CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells: their common role in controlling autoimmunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 182, 18–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fehérvari Z., Sakaguchi S. (2004) CD4+ Tregs and immune control. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 1209–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hori S., Sakaguchi S. (2004) Foxp3: a critical regulator of the development and function of regulatory T cells. Microbes Infect. 6, 745–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Josefowicz S. Z., Rudensky A. (2009) Control of regulatory T cell lineage commitment and maintenance. Immunity 30, 616–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu L. F., Rudensky A. (2009) Molecular orchestration of differentiation and function of regulatory T cells. Genes Dev. 23, 1270–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sakaguchi S. (2005) Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat. Immunol. 6, 345–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murphy T. J., Ni Choileain N., Zang Y., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (2005) CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control innate immune reactivity after injury. J. Immunol. 174, 2957–2963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ashour H. M., Niederkorn J. Y. (2006) γδ T cells promote anterior chamber-associated immune deviation and immune privilege through their production of IL-10. J. Immunol. 177, 8331–8337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kinsey G. R., Sharma R., Huang L., Li L., Vergis A. L., Ye H., Ju S. T., Okusa M. D. (2009) Regulatory T cells suppress innate immunity in kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 1744–1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lin C. Y., Tsai M. C., Huang C. T., Hsu C. W., Tseng S. C., Tsai I. F., Chen Y. C., Yeh C. T., Sheen I. S., Chien R. N. (2007) Liver injury is associated with enhanced regulatory T-cell activity in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J. Viral Hepat. 14, 503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Offner H., Subramanian S., Parker S. M., Wang C., Afentoulis M. E., Lewis A., Vandenbark A. A., Hurn P. D. (2006) Splenic atrophy in experimental stroke is accompanied by increased regulatory T cells and circulating macrophages. J. Immunol. 176, 6523–6531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kipnis J., Schwartz M. (2005) Controlled autoimmunity in CNS maintenance and repair: naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cells at the crossroads of health and disease. Neuromolecular Med. 7, 197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kvakan H., Kleinewietfeld M., Qadri F., Park J. K., Fischer R., Schwarz I., Rahn H. P., Plehm R., Wellner M., Elitok S., Gratze P., Dechend R., Luft F. C., Muller D. N. (2009) Regulatory T cells ameliorate angiotensin II-induced cardiac damage. Circulation 119, 2904–2912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Teige I., Hvid H., Svensson L., Kvist P. H., Kemp K. (2009) Regulatory T cells control VEGF-dependent skin inflammation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 1437–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kearney E. R., Walunas T. L., Karr R. W., Morton P. A., Loh D. Y., Bluestone J. A., Jenkins M. K. (1995) Antigen-dependent clonal expansion of a trace population of antigen- specific CD4+ T cells in vivo is dependent on CD28 costimulation and inhibited by CTLA-4. J. Immunol. 155, 1032–1036 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhou P., Borojevic R., Streutker C., Snider D., Liang H., Croitoru K. (2004) Expression of dual TCR on DO11.10 T cells allows for ovalbumin-induced oral tolerance to prevent T cell-mediated colitis directed against unrelated enteric bacterial antigens. J. Immunol. 172, 1515–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Szymczak-Workman A. L., Workman C. J., Vignali D. A. (2009) Cutting edge: regulatory T cells do not require stimulation through their TCR to suppress. J. Immunol. 182, 5188–5192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kelly J. L., O'Suilleabhain C. B., Soberg C. C., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (1999) Severe injury triggers antigen-specific T-helper cell dysfunction. Shock 12, 39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kavanagh E. G., Kelly J. L., Lyons A., Soberg C. C., Mannick J. A., Lederer J. A. (1998) Burn injury primes naive CD4+ T cells for an augmented T-helper 1 response. Surgery 124, 269–276, discussion 276–277 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Matzinger P. (1994) Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12, 991–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Matzinger P. (1998) An innate sense of danger. Semin. Immunol. 10, 399–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Seong S. Y., Matzinger P. (2004) Hydrophobicity: an ancient damage-associated molecular pattern that initiates innate immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 469–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Medzhitov R., Janeway C., Jr. (2000) Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunol. Rev. 173, 89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mollen K. P., Levy R. M., Prince J. M., Hoffman R. A., Scott M. J., Kaczorowski D. J., Vallabhaneni R., Vodovotz Y., Billiar T. R. (2008) Systemic inflammation and end organ damage following trauma involves functional TLR4 signaling in both bone marrow-derived cells and parenchymal cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 83, 80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lee K. M., Seong S. Y. (2009) Partial role of TLR4 as a receptor responding to damage-associated molecular pattern. Immunol. Lett. 125, 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]