Abstract

Background

Collaborative working relationships (CWRs) between community pharmacists and physicians may foster the provision of medication therapy management services, disease state management, and other patient care activities; however, pharmacists have expressed difficulty in developing such relationships. Additional work is needed to understand the specific pharmacist-physician exchanges that effectively contribute to the development of CWR. Data from successful pairs of community pharmacists and physicians may provide further insights into these exchange variables and expand research on models of professional collaboration.

Objective

To describe the professional exchanges that occurred between community pharmacists and physicians engaged in successful CWRs, using a published conceptual model and tool for quantifying the extent of collaboration.

Methods

A national pool of experts in community pharmacy practice identified community pharmacists engaged in CWRs with physicians. Five pairs of community pharmacists and physician colleagues participated in individual semistructured interviews, and 4 of these pairs completed the Pharmacist-Physician Collaborative Index (PPCI). Main outcome measures include quantitative (ie, scores on the PPCI) and qualitative information about professional exchanges within 3 domains found previously to influence relationship development: relationship initiation, trustworthiness, and role specification.

Results

On the PPCI, participants scored similarly on trustworthiness; however, physicians scored higher on relationship initiation and role specification. The qualitative interviews revealed that when initiating relationships, it was important for many pharmacists to establish open communication through face-to-face visits with physicians. Furthermore, physicians were able to recognize in these pharmacists a commitment for improved patient care. Trustworthiness was established by pharmacists making consistent contributions to care that improved patient outcomes over time. Open discussions regarding professional roles and an acknowledgment of professional norms (ie, physicians as decision makers) were essential.

Conclusions

The findings support and extend the literature on pharmacist-physician CWRs by examining the exchange domains of relationship initiation, trustworthiness, and role specification qualitatively and quantitatively among pairs of practitioners. Relationships appeared to develop in a manner consistent with a published model for CWRs, including the pharmacist as relationship initiator, the importance of communication during early stages of the relationship, and an emphasis on high-quality pharmacist contributions.

Keywords: Pharmacists, Physicians, Collaborative working relationships, Pharmacist-physician collaborative index, Community

Introduction

The recent proliferation of medication therapy management (MTM) services offered through Medicare Part D1,2 has put a spotlight on patient care opportunities for pharmacists, particularly those who practice in the community setting. Activities, such as community pharmacist-provided MTM and disease state management, are enhanced when an effective collaborative working relationship (CWR) exists between the pharmacist and the patient’s physicians. The potential benefits of physicians and pharmacists working together have been documented.3–7 Nevertheless, community pharmacists struggle to establish relationships with physicians. Lounsbery et al surveyed 970 pharmacists from various outpatient practice settings regarding their agreement with potential barriers in providing MTM services and found that community pharmacists were more likely than pharmacists in other ambulatory settings to agree that establishing CWRs with physicians was a barrier to service provision.8

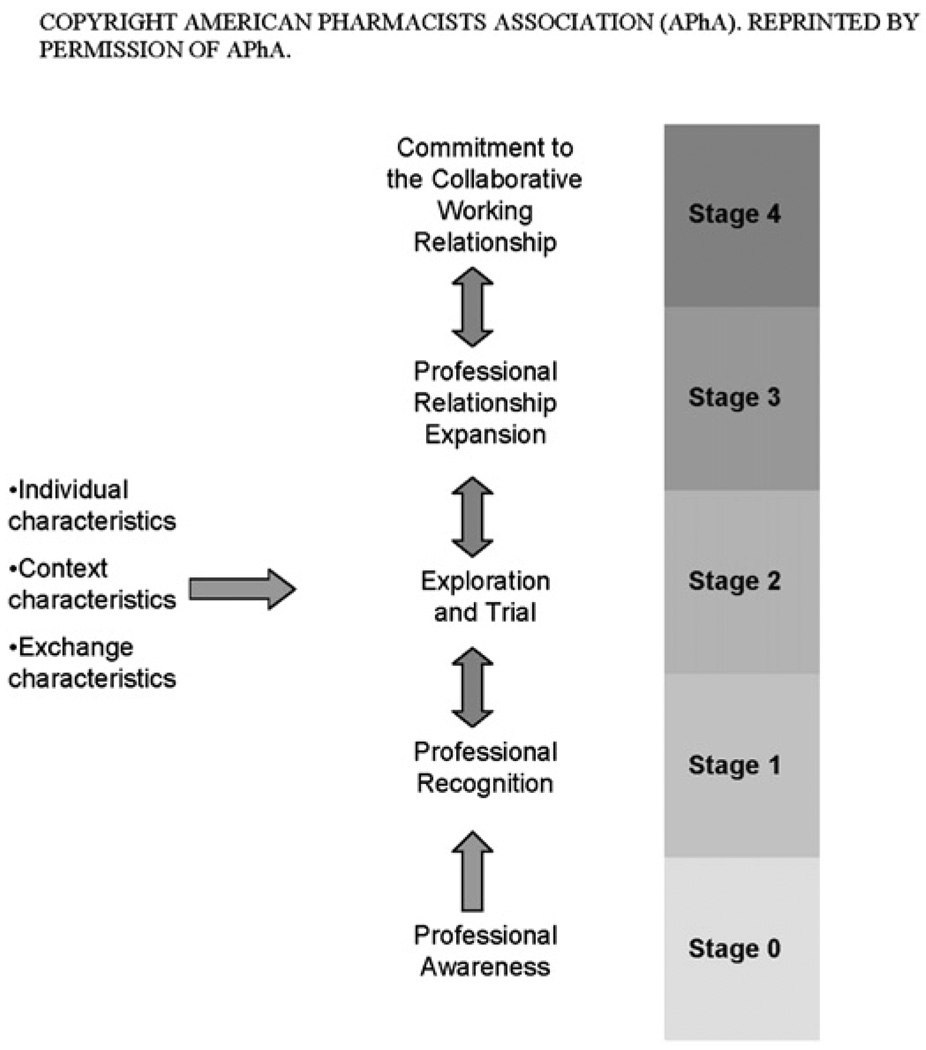

To assist practitioners and researchers interested in pharmacist collaborations, McDonough and Doucette have proposed a conceptual model for the development of pharmacist-physician CWRs (Fig. 1).9 The CWR model was synthesized from models of interpersonal relationships, business relationships, and collaborative care from nursing/physician relationships.10–15 This framework illustrates how individual, context, and exchange characteristics influence movement along a collaboration continuum, from stage 0 (professional awareness) to stage 4 (commitment to the CWR).9 Individual characteristics are those specific to each collaborating professional, such as age and educational background. Context characteristics, such as the proximity of the professionals and shared organizational structures, are associated with the practice site of the collaborators. Exchanges are the personal interactions that occur between physicians and pharmacists.

Fig. 1.

Model for physician-pharmacist collaborative working relationships. Reprinted with permission from American Pharmacists Association (APhA). Copyright APhA.

Using the CWR model as a guide, Zillich et al demonstrated that, although select participant and contextual characteristics influenced relationship development, exchange characteristics are the principal drivers in the development of pharmacist-physician collaborations.16 In 2005, Zillich et al found that these exchanges can be grouped into 3 domains: relationship initiation, trustworthiness, and role specification.17 The extent of professional collaboration can be quantified through the administration of the Pharmacist-Physician Collaborative Index (PPCI), a 14-item Likert scale that measures collaboration within the 3 exchange domains.16–18 This quantitative measure, however, does not reveal the specific exchanges that have occurred to reach a high level of collaboration.

The purpose of the present study was to describe the professional exchanges that occurred between community pharmacists and physicians engaged in successful CWRs, using the aforementioned conceptual model and tool for quantifying the extent of collaboration among the professionals as guides. Insights from this study may assist researchers interested in understanding collaborative care models and pharmacists interested in developing collaborations in their practice, while further validating the CWR model proposed by McDonough and Doucette.9 To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to explore, quantitatively and qualitatively, the professional exchanges occurring among pairs of community pharmacists and physicians engaged in highly CWRs.

Methods

Study design and participant recruitment

The first step in studying the professional exchanges occurring among highly collaborative pharmacist-physician pairs is to identify examples of these pairs to serve as research participants. In qualitative research, participants are selected for their familiarity with the concept in question19 — in this example, the professional exchanges that have led to successful collaborations. Therefore, a nonrandom, purposeful sampling technique was used for participant identification and recruitment. 19 In this study, because the objective was to learn specifically about the exchanges occurring in uniquely collaborative examples (rather than among “typical” cases of pharmacists and physicians), purposeful sampling was used to identify only highly collaborative pharmacist-physician pairs in community settings.

To identify community pharmacist-physician pairs who have established highly successful collaborations, “community pharmacy experts” (n = 178) from throughout the United States were contacted, and each was asked to identify 1–2 community-based pharmacists whom they perceived to be engaged in an effective professional collaboration with a physician colleague. Community pharmacy experts were defined as individuals who are well positioned to be knowledgeable about a variety of community pharmacist practitioners, particularly those in their respective geographic area. Experts were not provided with specific guidelines or definitions for “successful,” “effective,” or “highly collaborative” relationships; rather, it was anticipated that experts could identify uniquely collaborative community pharmacists based on their familiarity with community pharmacy practice and the “typical” relationships that exist between community pharmacists and physicians. Similar recruitment approaches using pharmacy leaders to identify innovative community pharmacists have been described by other authors who have studied these relationships.20,21

Contacted “experts” included select faculty from colleges/schools of pharmacy (n = 102), pharmacy clinical services managers (n = 15), and leaders of major pharmacy organizations (n = 61). The pharmacy faculty included experiential learning program directors from each college/school and others engaged in community-based initiatives. These faculties were selected because of their familiarity with community pharmacist preceptors. Clinical service managers and pharmacy association leaders were included because of their familiarity with pharmacists providing direct patient care services as employees of their company (for the former) or as active members in the organization (for the latter.) A total of 47 national “experts” responded to the queries and identified 87 community pharmacists for potential inclusion in the study. Of note, some of these pharmacists were identified by more than 1 source (eg, a faculty member and an association leader may have identified the same individual).

To be included in this study, these 87 pharmacists had to be currently engaged in an active community-based patient care practice, with at least some time devoted to nondispensing, patient care activities (although the exact amount of time was not defined). For the purpose of this study, community-based practices (ie, traditional community pharmacies) were considered distinct from traditional ambulatory care, primary care, or family medicine pharmacist practice settings. This distinction was made to control for contextual factors (such as shared physical space) that may influence the development of pharmacist-physician relationships. Second, the pharmacists needed to have a collegial relationship with a physician, as initially perceived by expert referral and confirmed by the pharmacist’s willingness to identify that colleague for potential participation in the study. It was not required that the practitioners be engaged in any form of legal collaborative practice agreement or other practice protocol. Finally, the physician colleagues identified by the pharmacists had to agree to participate in an individual semistructured interview. The study protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

First, each of the identified pharmacists was contacted and asked to complete both an online survey of basic background and demographic information along with the PPCI16–18 (Appendix 1). A link to both surveys was included in the body of the e-mail. Survey responses were collected in Survey Monkey®, an Internet-based survey tool. All informants gave electronic consent before completing the survey.

Demographic information was collected to describe the participant and context characteristics that may influence the relationships being studied. Demographic information collected from pharmacist informants included age and years in practice, education and training, size of community served, weekly hours of pharmacy operation and time spent each week on dispensing versus patient care, position title, number of prescriptions filled per hour, number of pharmacists/technicians on duty at one time, academic affiliation, type and location of pharmacy, and currently established patient care services.

As described earlier, the PPCI is a validated 14-item Likert scale tool that quantifies the extent of practitioner collaboration within the exchange domains of relationship initiation, trustworthiness, and role specification. The PPCI provides a summary score from 14 to 98, with a higher score indicating a greater extent of collaboration. 16–18 Although the intention was to use PPCI scores as a guide for choosing which practitioners to interview (ie, inviting interviews first from practitioners with the highest scores), because of the small sample size, all responding practitioners meeting study eligibility criteria were invited to participate in the interviews, and the PPCI was used to provide quantitative information about the professional exchanges occurring between the pharmacists and their physician colleagues.

When completing the PPCI, all pharmacists were asked to use 1 physician as a frame of reference for an effective professional collaboration and provide that individual’s name and contact information electronically. These physician colleagues were then contacted and asked to complete similar survey tools: a background/demographic survey and the PPCI from the physician perspective (Appendix 2). Demographic data collected from physicians included age and years in practice, education and training, number of total hours worked per week and number of those hours spent on patient care activities, size of community served, physician work position, number of patients seen per week, academic affiliation, and type and location of practice. Each physician was asked to complete the PPCI using his/her pharmacist colleague as the frame of reference. Both practitioner participants were also asked to briefly describe, in their own words, their professional collaboration with the other professional (either pharmacist or physician).

To gather qualitative information about the specific interactions that occurred, these practitioner pairs were then asked to participate in individual interviews with study investigators. Both practitioners (pharmacists and physicians) in each pair were interviewed independently. During the interviews, participants were asked a standardized set of open-ended questions to extract information about actions taken in the exchange domains of relationship initiation, the development of trustworthiness, and professional role specification (Appendices 3 and 4). Interview questions were tested for face validity through review by clinically trained pharmacist and physician investigators. Pilot testing was performed through individual interviews with a small group of community pharmacist practitioners.

Interviews were conducted face-to-face at the practitioner’s practice site, a common meeting place, or by means of telephone. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Most of the interviews were conducted by the principal investigator (M.E.S.), with the remaining interviews completed by a research assistant, trained by the principal investigator. Interviews were audio (in the case of telephone) or audio- and video-recorded when conducted face-to-face. Investigators took field notes during each interview. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed by investigators for accuracy.

Data analysis

SPSS (version 16.01; Chicago, IL) was used to calculate descriptive statistics of demographic variables and PPCI scores. A systematic approach was used to evaluate the responses obtained from the semistructured interviews. Transcripts were entered into ATLAS.ti software (version 4.1; Berlin, Germany) for content analysis. A coding scheme was developed based on the topics addressed in the semistructured interviews, and this scheme was used to identify common themes discussed by participants. Transcripts were first read and coded independently by 2 investigators (M.E.S. and K.R.), and a codebook was developed to track and define variables throughout the coding process. After independently coding each transcript, the investigators met to discuss coding decisions and finalize code assignments. Any discrepancies were resolved by group consensus. Repeating themes under each question domain are described later, with representative quotations provided.

Results

Sample

There were 87 identified pharmacists representing a minimum of 29 states and Puerto Rico. Of these identified pharmacists, 24 provided consent and completed the online survey tools. Ten of these pharmacists were excluded, because they did not practice in a traditional community setting. Two pharmacists were excluded for incorrectly completing the survey tools (eg, not providing the name of a physician colleague). Two pharmacists did not respond to the request for participation in the qualitative interview. Five pharmacists were interviewed but then excluded from data analysis, because their physician partner declined to participate. A total of 5 pharmacist-physician pairs completed individual semistructured qualitative interviews. One physician did not complete the background survey and PPCI, but their qualitative results are included in the following section.

Individual and context characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 summarize individual and contextual characteristics of pharmacists and physicians obtained from the demographic surveys. All of the physicians providing information were males, had received a Doctor of Medicine (in contrast to a Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine and most were in private practice. Most of the pharmacists were males and had received a Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD). Most pairs practiced in a relatively small community (ie, population of less than 50,000). On average, the physicians were older and had been in practice longer than the pharmacists.

Table 1.

Pharmacist characteristics (n = 5)

| Pharmacist characteristics | Results |

|---|---|

| Age in years, median (range) | 34 (28–56) |

| Sex, no. | |

| Men | 4 |

| Women | 1 |

| Years in practice, median (range) | 5 (3.5–33) |

| Highest education, no. | |

| BS, pharmacy | 1 |

| PharmD | 4 |

| Residency training, no. | 2 |

| Community served, no. | |

| <10,000 | 0 |

| 10,001–49,999 | 3 |

| 50,000–499,999 | 1 |

| ≥500,000 | 1 |

| Type of pharmacy, no. | |

| Independent | 3 |

| Chain | 2 |

| Total hours worked per week, median (range) | 50 (45–55) |

| Hours spent dispensing (weekly), median (range) | 8 (0–20) |

| Hours spent on patient care (weekly), median (range) | 25 (16–30) |

| Pharmacists on duty, median (range) | 2 (2–5) |

| Technicians on duty, median (range) | 4 (2–5) |

| Student training site, no. | 5 |

| Resident training site, no. | 3 |

| Established clinical servicesa, no. | |

| Anticoagulation | 0 |

| Diabetes | 4 |

| Hypertension | 2 |

| Asthma | 0 |

Not mutually exclusive.

Table 2.

Physician characteristics (n = 4a)

| Physician characteristics | Results |

|---|---|

| Age in years, median (range) | 51 (36–55) |

| Sex, no. | |

| Men | 4 |

| Women | 0 |

| Years in practice, median (range) | 18 (5–27) |

| Education, no. | |

| Doctor of Medicine | 4 |

| Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine | 0 |

| Community served, no. | |

| <10,000 | 0 |

| 10,001–49,999 | 3 |

| 50,000–499,999 | 1 |

| ≥500,000 | 0 |

| Type of practice, no. | |

| Private | 3 |

| Academic | 1 |

| Specialty, no. | |

| Family practice | 2 |

| Internal medicine | 1 |

| Other | 1 |

| Number of patients seen per week, median (range) | 47 (20–130) |

| Hours spent on patient care per week, median (range) | 34 (20–65) |

| Total hours worked per week, median (range) | 50 (28–65) |

| Student training site, no. | 2 |

| Resident training site, no. | 1 |

One physician did not complete background survey.

Exchange domains

A summary of PPCI total and domain scores is provided in Table 3. On the trustworthiness domain of the PPCI, pharmacist and physician participants appeared to score similarly; however, physicians appeared to score higher, on average, than their pharmacist colleagues in the domains of relationship initiation and role specification. Because of the small sample size, no statistical comparisons were made. Table 4 triangulates the qualitative (ie, representative quotations) and quantitative (PPCI scores) findings specific to each exchange domain and pharmacist-physician pair.

Table 3.

Participant PPCI scoresa

| PPCI score (possible range) | Mean ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacists, n = 5 | ||

| Total score (14–98) | 79.4 ± 10.2 | 62–88 |

| Domain | ||

| Trustworthiness (6–42) | 39.2 ± 3.1 | 35–42 |

| Relationship initiation (3–21) | 16.2 ± 2.9 | 12–19 |

| Role specification (5–35) | 24.6 ± 6.9 | 15–32 |

| Physicians, n = 4b | ||

| Total score (14–98) | 89.8 ± 4.6 | 85–96 |

| Domain | ||

| Trustworthiness (6–42) | 39.8 ± 1.7 | 38–42 |

| Relationship initiation (3–21) | 20.3 ± 1.0 | 19–21 |

| Role specification (5–35) | 29.8 ± 2.9 | 26–33 |

SD, standard deviation.

PPCI scores range from 14 to 98, with higher scores representing a more advanced relationship.

One physician did not complete.

Table 4.

PPCI scores and participant quotations

| Pair | RPh PPCI domain score | RPh quotations | MD PPCI domain score | MD quotations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship initiationa | ||||

| 1 | 15 | “I really think … relationships have developed because of working for a common goal and so when I say that, I mean patient care goals ….” “… the quality of the intervention I am providing and I provide it in a very concise way and the same way as if I was face-to-face … it is patient focused.” |

21 | “And what he did that was extraordinary was he went out of his way to get to know the patients …” “And a person with good communication skills … and an honest intent to do what is right for the patient.” “… I think being able to articulate your recommendation and in a succinct way support your recommendation comes in very helpful … ” |

| 2 | 12 | “… There is a small group of physicians … so we pretty much hit them all.” [referring to when visiting physicians in the community] “…we did go to every physician in the area and did a little breakfast or little lunch explaining to them the things that we would be trying to do.” “… we’re in a pharmacy that has been in the community for a long time …” “… just making sure my intentions were positive …” |

21 | “… we both have different jobs but we both have an end goal and that is to take care of the patient …” “Just being receptive to their comments and their knowledge …” |

| 3 | 16 | “So his ideals and our ideals matched very well.” “… our patient focused activities when we decided we were going to be involved in that, approaching physicians was where we started …” “… we had a long standing tradition in the community …” “His bottom line is he wants to improve patient care …” |

19 | “He came to my office and said, … this is what I do and this is who I am and this is where my pharmacy is …” “That was the icebreaker and it made it so easy after that. But clearly it was his initiative that made it happen.” “He is sincere. He does a good job for the patients and it was very obvious.” |

| 4 | 19 | “The first thing that I did was to visit like 20 or 25 physicians around the town … I went to explain to them the program, the service that we were planning to give …” “I would do more personal contact with the physicians, not by phone, not even by letter …” “I always explained it very clearly, what the vision was …” |

20 | “He established contact with me over the phone and he explained to me that he was planning to develop a plan with diabetic patients. Then I went to the pharmacy, and he explained to me how we can work collaboratively together.” “He asked me to participate educating the patients together with him …” “Well, I studied medicine for patient care and I am also very interested in the educational period.” |

| 5 | 19 | “… we probably did a lot of lunches just to let them know what we had to offer for their patients.” “Well you have to go in with the attitude … it’s not really I want referrals, I want to help your patient …” |

n/a | “… one of our local drug stores had a PharmD come in and he is doing a lot of educational stuff with my patients. And so it just created a bridge for us to talk about my patients a little more and get them you know more their medicines better regulated especially for diabetes.” “They came by and did lunches to start with.” |

| Mean (SD) | 16.2 (2.9) | 20.3 (1.0) | ||

| Trustworthinessb | ||||

| 1 | 40 | “… from what I can gather is that physician saw the quality of intervention … I think that is the reason why trust developed with them.” “… I think physicians see one that I’ve done my background information …” |

38 | “They demonstrate their knowledge … when you bring something meaningful to the table … it is very clear.” “Getting to know the patient is huge. Huge because it really demonstrates and makes clear where your alliances are.” |

| 2 | 35 | “I’m not a name without a face.” “ … trying to continue to communicate with physicians … keep them involved …” |

42 | “… have good outcomes …” [referring to patient clinical outcomes] “… just by providing a good service and then the patient outcomes are what we like … trust is … something you earn through time …” |

| 3 | 42 | “Because we are good at it [patient care] … I think the physicians in the area understand that and expect that because they have been doing it for a long time.” | 40 | “… you could tell he was a bright guy and he … related to the patients very well … That to me was very important; the ability to communicate with that one patient at that time and get the message across. That was how those pharmacists won my confidence.” “Well by knowing the other pharmacists … they came in already vouched for …” |

| 4 | 42 | “All the physicians know the pharmacies in town … as a son of a pharmacist, I am known … So probably that helps me because my mom as a pharmacist has a good reputation …” “And when the patient has good results, the physician is happy and trusts us.” “To maintain that trust … just keeping in touch with the physicians …” |

39 | “… he has a genuine concern.” [for patients] “… trust starts with the individual and continues with the professional aspect. If … a trustworthy person and is a respected professional and respectful with other professionals and with the patients, and at the same time demonstrates that is knowledgeable on his field, up-to-date, shares his knowledge …” “ … comes from an excellent family … parents work also in a pharmacy …” “… principal interest is the patient …” |

| 5 | 37 | “… you have to go in every now and then just to revisit …” “… making sure you keep them in communication.” |

n/a | “Because they get things right and they pick up the telephone …” “I would say consistency and accuracy.” [describing their interactions with their pharmacist collaborator] “… they seem willing to work with me and they got it right. They consistently got it right.” |

| Mean (SD) | 39.2 (3.1) | 39.8 (1.7) | ||

| Role specificationc | ||||

| 1 | 25 | “I focus on the drug therapy. Iam not involved in the diagnostics or anything like that.” “My responsibility is to take care of the patient. I would never let that [physician resistance] stop me from doing that.” |

26 | “… there is … a cultural expectation of the physician that is different or distinct from the pharmacist. I think there is a sense that the physician carries a higher burden of executive responsibility. So when the prescribing is ultimately done, the ultimate executor of that prescription decision is the physician.” “So it may very well be that my clinical pharmacist has more knowledge at the point of … decision making than I do and I make a decision because that is my job … that can create stress and … friction.” |

| 2 | 15 | “… we have to explain that our job is to do all of this and we are going to look at the medications and evaluate the appropriateness of these medications and see if there is a way to optimize them. And then we are going to provide you with that feedback that you can disregard … you definitely have that right.” “My role is definitely different … physicians are there diagnosing … they are the prescribers. My role is to support that. One is education.” |

33 | “Well, the pharmacist’s primary role I think is to help educate the patient in their medications.” “But still it is ultimately my decision and my authority that the recommendations come from. The patient is not going to implement them without me.” “To my knowledge they don’t make recommendations to the patient, they make recommendations to me.” |

| 3 | 30 | “What I think pharmacists now are trying to do is support that physician’s role …” “The physician is still absolutely essential in driving that patient’s health care.” |

30 | “… I practice medicine and some of the practice of medicine has to do with dispensing or prescribing medications. I think that is different from what the pharmacist does which is dispensing medications, evaluating medications, and collaborating in management of disease states.” “They are really helpful but they’re not trying to practice medicine. I think that is a misconception on the part of some physicians.” |

| 4 | 21 | “…we have to give more service besides the distribution of drugs to the patient … We can solve many drug related problems …” “We cannot make a diagnosis but we can make a good screen and send the patient to the physician.” “Our role is about the same [when working with physicians of varying levels of acceptance of pharmacist collaboration] but the results are going to be different … ” |

30 | “… I don’t think that any health provider is over the other one. Each one has its role. Here I do my educational practice above all. I treat the patient … when the pharmacist receives the patient, they are being treated under his area of expertise, the same with the nutritionist and the other health providers.” “[in describing a specific patient] … It seems like he didn’t ask for the pharmacist’s advice because he bought stuff without prescription. If he had asked the pharmacist, he would get advice and the patient would come earlier to me.” |

| 5 | 32 | “I do everything but prescribe.” “Secondary to their care in conjunction. I’m basically between their office visits.” “… I still communicate to both of them [physicians that are accepting and those that are resistant]” |

n/a | “… they make suggestions to me usually first. So if it is not something that I want to do, the patient is not calling me saying ‘well the pharmacist thinks whatever.’ ” “I think my patients have been very, very excited about the educational part that they are getting … from the pharmacy. And I think we just supplement each other very well.” |

| Mean (SD) | 24.6 (6.9) | 29.8 (2.9) |

RPh, pharmacist; MD, Physician.

Scored on 7-point Likert scale from 1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree; possible range of domain scores is 3–21.

Scored on 7-point Likert scale from 1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree; possible range of domain scores is 6–42.

Scored on 7-point Likert scale from 1 = very strongly disagree to 7 = very strongly agree; possible range of domain scores is 5–35.

Relationship initiation

In the domain of relationship initiation, it was found that pharmacists were the primary initiator of these CWRs, and this role was acknowledged by both types of practitioners during the interviews. Generally, pharmacists approached each of the physicians in their geographic area (rather than targeting specific physicians). Initial conversations were usually (but not always) conducted face-to-face and often scheduled in advance by the pharmacist. Many of the participants described the use of face-to-face visits as a mechanism for developing a “personal” relationship with their collaborator. One physician emphasized the importance of these encounters, “… Right now in at least one of the healthcare settings in which I work, I could not tell you the name of the clinical pharmacist that gives me advice and I would not be able to recognize them if I was four feet from them. So that to me is a bit of a problem.” A pharmacist echoed this sentiment, “You have to get the face-to-face. They are not going to refer [patients] to someone they don’t know or they’ve never met before. Even if you have all the credentialing in the world they are not going to do that. So you have to get in front of them. You have to tell them what your goals are …” Professionals who ultimately became collaborators shared a similar value set in the sense that improved patient care was their primary motivator. Along with an enhanced professional role for pharmacists, this was often the only expectation that either professional had for collaborating.

Some pharmacists scheduled these preliminary meetings over lunch or dinner. Although the discussions clearly involved the physician, other members of the office staff were sometimes present. Other mechanisms for establishing initial contact with physicians included involvement in community organizations and sending written notes. Recognizing that relationships are built over time and that it was important to take things “slow,” either with regard to asking for appointments with physicians or in making drug therapy recommendations, were noted. One physician described the process he observed in his pharmacist collaborator, “Well, he started slow. He was, this fellow, was very, very good at winning confidence and he took a little time to win mine. He just initially introduced himself. That was the first thing. He knew I was busy and he knew he was busy and then he just came back once or twice a week for the first several months just to make sure things were going well. He didn’t try to lecture me or educate me or anything other than he knew the community and that was really obvious.”

During these early conversations with physicians, the pharmacists explained their preferred role and the clinical services they offered. Some pharmacists also brought educational materials that would be used during their visits to patients. Reflecting back on this first encounter, 1 pharmacist also made the suggestion that it would have been helpful to bring an example of the specifically written documentation the physician can expect to see after each patient visit. From the physician’s perspective, this may be especially useful in ensuring that recommendations are more likely to be accepted. As 1 physician described, “I think that sometimes the way they [pharmacists] frame their advice can be framed in different ways. So frequently, especially if recommendations come in a written form, we’ll sit down and say, ‘Look if you could reframe this in a different way in the future I think it would be easier for we physicians to respond to it constructively rather than in a knee jerk fashion.’ So I think strategizing about ways to frame the recommendations can also be very helpful.”

Trustworthiness

In discussing the trust between these pharmacists and physicians, the conversations centered around actions taken by the pharmacist to gain the physician’s trust (rather than the physician needing to gain the pharmacist’s). Of primary importance for establishing trust was the provision of high-quality clinical recommendations that improved patient outcomes. Both professionals commented on how seeing these positive outcomes was key to the success of their relationship. These recommendations needed to be provided consistently over time to develop an expectation for the level of care provided by the pharmacists.

In addition to demonstrating competence, ongoing communication with the physician (ie, “keeping them in the loop”) was very important. One pharmacist described this, “… he [the physician] needs to know what we are doing so if he is queried by fellow physicians, the medical society, or ‘why are you supporting what they [pharmacists] are doing?’ He needs to know exactly what we are doing … and vice versa, we need to know that he is going to be able to supply us information or support at the level we need.” However, unlike when the professionals were asked about relationship initiation, this communication did not usually happen face-to-face. More often, this communication occurred by means of written recommendations that were sent by fax for the physician to review at their convenience. As 1 pharmacist described, “… making sure you keep them [physicians] in communication. You know like sending progress notes … just keeping them in the loop because when you don’t keep them in the loop they really wonder what is actually going on.” The ability to vary communication methods appropriately was also noted as important in the relationship process, that is, respecting the urgency of a situation and using clinical judgment to respond with a phone call if necessary, or if less urgent, the faxed note.

Preexisting relationships between the pharmacist and other community members or the pharmacist and the patient were also discussed. Some of the pharmacists were introduced to their collaborator through another pharmacist and commented that trust came more easily in these situations. Physicians also commented that trust was enabled, because the pharmacist had personally gotten to know the patient.

Role specification

The interviews revealed that both professionals were generally in agreement regarding the patient care role of the pharmacist as compared with the physician. Specifically, it was noted that pharmacists “focus on the drug therapy” and provide patient education while supporting the physician. Although physicians valued these professional contributions, they emphasized that the role of the pharmacist was quite different from their own roles. Physicians reported that even while engaged in a highly CWR, they were still the team members ultimately responsible for the patients’ outcomes and, in that role, functioned as the decision makers.

Pharmacists also described situations where they have encountered physicians (not their physician partner who was interviewed) who were resistant to collaboration. Resistance manifested passively, as lack of physician response to recommendations, and actively, as refusal to provide patient laboratory data in spite of signed medical releases and hesitations to provide referrals for clinical services beyond patient education. When asked how their patient care role was affected by these encounters, the pharmacists emphasized that the professional service they provided did not vary. They stressed that, because the patient (rather than the physician) was their priority, they provided the same level of care to the patient and communication to the physician that they did with physicians with whom they had a highly collaborative relationship. The physicians then have the choice whether to carry out or not to carry out the recommendation. One pharmacist describes this situation in his practice, “My responsibility is to take care of the patient. I would never let that stop me from doing that. So they may get upset that I keep sending them notes and recommendations, but I have found out even in those physicians who may not be responding (as long as they’re not calling me and telling me to stop doing this and I haven’t had anybody do that) sometimes things get changed without me getting an actual recommendation back. So I realize that someone is reading it along the way. I do think I have that responsibility to take care of the patient so it doesn’t change.”

Discussion

The process for identifying community pharmacist-physician pairs engaged in effective CWRs was fruitful. Despite not providing experts with a clear case definition of “effective” or “successful,” the pharmacist PPCI scores were comparable with the highest scores reported in earlier studies, indicating high levels of collaboration among the identified sample.18 In addition, the physicians’ PPCI scores were higher across each domain compared with previously reported scores among a large, cross-sectional sample of primary care physicians.16,17

The qualitative exploration of the CWR exchange domains revealed several exchanges that occurred among the professionals when relationships were initiated, trust was established, and professional roles were clarified. Many of these findings (eg, pharmacist as initiator, the importance of communication at early stages of the relationship, and the emphasis on high-quality pharmacist contributions) support the CWR model proposed by McDonough and Doucette9 and provide opportunity for future study.

Specifically, the role of the pharmacist as relationship initiator has been described in earlier work examining these collaborations.20 The study’s qualitative findings of the pharmacist as the primary relationship initiator likely influenced the quantitative results for this exchange domain. On the relationship initiation domain of the PPCI, physicians scored higher than pharmacists. Recognizing that relationship initiation depends largely on their actions, pharmacists may have been critical of their actions, resulting in lower scores on these items. On the other hand, the physicians who recognized that they would not have taken the initiative for relationship development were pleased with the approaches taken by pharmacists. Notably, the mean physician PPCI score for this domain was 20.3 out of a maximum possible score of 21, suggesting high physician satisfaction with the specific initiating behaviors described by the pharmacists in this study. However, other authors who studied CWRs from the pharmacist perspective have not found a relationship among exchanges within this domain and successful collaborations.21 Therefore, more work is needed to determine whether pharmacists initiating relationships in the manner described by participants have greater success in developing collaborations than those using other methods.

Both the qualitative and quantitative findings suggest that community pharmacists and physicians engaged in highly collaborative relationships view trustworthiness in a similar fashion. Both professionals scored similarly on the PPCI and emphasized similar characteristics of the relationship that resulted in a high level of trust. In particular, the importance of establishing a “track record” through consistent, high-quality contributions (by the pharmacist) to patient care was emphasized by both types of professionals.

For role specification, the qualitative findings suggested congruence between how each professional viewed his or her respective roles. However, the discrepancy in PPCI scores between the pharmacists and physicians imply that pharmacists feel less strongly than physicians that both professionals are mutually dependent on each other and that pharmacists are able to successfully negotiate their role in patient care. This apparent discrepancy between the qualitative and quantitative results of this exchange domain warrant further study, because other authors have found that role specification is an important aspect of successful CWRs.16,21

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to triangulate PPCI scores with qualitative perspectives from both professionals. Several of the findings support the work of Brock and Doucette, 20 who conducted an in-depth case study with 10 pharmacists engaged in varying levels of collaboration with physicians. The purpose of the inquiry was to identify variables that distinguish between highly collaborative and less collaborative relationships. Similar to the current results, these authors found that the pharmacist was the relationship initiator, that face-to-face communication was important, and that the relationships developed over time.20 However, they did not find that initiating behaviors, trust, conflict resolution, an assessment (by the physician) of the pharmacists’ competence, or a history of a prior relationship among professionals differentiated between the pharmacists in high-level collaborations versus those at a lower stage of the CWR. In the present study, each of these exchanges was discussed by both professionals (across the pairs) during the qualitative interviews. This warrants further study, because Brock and Doucette20 collected data only from the pharmacist perspective, whereas the current study elicited both perspectives. Nevertheless, differences in perspectives of pairs engaged in high-level versus lower-level collaborations were not assessed. Consequently, more work is needed to understand the importance of these exchanges on developing relationships from the physician perspective.

Limitations

This study had a relatively low response rate; 26% of the “experts” responded to the request for pharmacist identification, and fewer physicians than pharmacists agreed to participate in the online surveys and interviews. This may be because of “expert” misinterpretation of study-inclusion criteria. For example, the first author received several e-mails from “experts” stating that they could not identify a pharmacist, because the state they reside in does not allow legal collaborative practice agreements. Furthermore, a lower physician response may be because of the methodology used for recruitment, and/or the lack of compensation for time associated with participation, because the interviews averaged 30–60 minutes. Although an attempt was made to increase participant enrollment through follow-up contacts with identified pharmacists and physicians, there was no attempt to identify and recruit new pharmacist-physician pairs. This approach could have resulted in a greater sample size.

Although analysis of the qualitative data revealed repeating themes, it is unknown if additional themes would have emerged with a greater number of interviews. More interviews also may have provided greater insights into the qualitative and quantitative discrepancies we found for the role specification domain. Furthermore, the design and sampling strategy for this study only included participants with high levels of collaboration. This study did not explore outliers who do not collaborate or struggle to collaborate. Future studies among a group of low collaborators may provide additional information important in developing relationships. In addition, given the small sample size, inferences from the quantitative data are speculative. Future studies with larger sample sizes should explore variations in the magnitude of the difference between pharmacist and physician PPCI scores. Finally, although some of the participants have been informally exposed to the current findings after participation in the interviews, a formal process for confirming the authors’ interpretations of the qualitative findings with study participants and allowing participant commentary may have strengthened the study results and enhanced confidence in the authors’ interpretations of the qualitative data.

Conclusion

The study findings support and extend the literature on pharmacist-physician CWRs by examining the exchange domains of relationship initiation, trustworthiness, and role specification qualitatively and quantitatively among pairs of practitioners. It was observed that relationships appeared to develop in a manner consistent with the CWR model, including the pharmacist as relationship initiator, the importance of communication during early stages of the relationship, and an emphasis on high-quality pharmacist contributions. Future studies on relationship dyads using both quantitative and qualitative methods are warranted to understand how CWRs are developed and sustained over time.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Brittany DeVoge, Pharm.D., Gladys Garcia, Pharm.D., and Cheri Hill for assistance with data collection and management; Lois Edmondston for assistance with tables and figures; and the American Pharmacists Association Foundation and the Community Pharmacy Foundation for grant support.

Funding: This study was supported by the American Pharmacists Association Foundation and the Community Pharmacy Foundation. Also, Dr. Zillich was supported by a Research Career Development grant from the Veterans’ Affairs Health Services Research and Development (#RCD 06-304-1).

Appendix 1

Physician-Pharmacist Collaborative Index for pharmacists

Consider your working relationship with 1 physician you work closely with. Think, in general, about the interactions you have had with this physician over time. Please indicate your agreement with each of the following statements by using the scale listed as follows. Please circle the number that represents your agreement with the item.

SCALE: 1—very strongly disagree; 2—strongly disagree; 3—disagree; 4—neutral; 5—agree; 6—strongly agree; 7—very strongly agree

| For our practices, I need this physician as much as this physician needs me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This physician is credible. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| My interactions with this physician are characterized by open communication by both parties. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I can count on this physician to do what he/she says. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This physician depends on me as much as I depend on him/her. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This physician and I are mutually dependent on each other in caring for patients. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This physician and I negotiate to come to an agreement on my activities in managing drug therapy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This physician will work with me to overcome disagreements on my role in managing drug therapy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I intend to keep working together with this physician. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I trust this physician. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Communication between this physician and myself is two-way. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I spend time trying to learn how I can help this physician provide better care. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I provide information to this physician about specific patients. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I try to understand the needs of this physician’s practice. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Appendix 2

Physician-Pharmacist Collaborative Index for physicians

Consider your working relationship with 1 pharmacist you work closely with. Think, in general, about the interactions you have had with this pharmacist over time. Please indicate your agreement with each of the following statements by using the scale listed as follows. Please circle the number that represents your agreement with the item.

SCALE: 1—very strongly disagree; 2—strongly disagree; 3—disagree; 4—neutral; 5—agree; 6—strongly agree; 7—very strongly agree

| In providing patient care, I need this pharmacist as much as this pharmacist needs me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| The pharmacist is credible. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| My interactions with this pharmacist are characterized by open communication of both parties. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I can count on this pharmacist to do what he/she says. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This pharmacist depends on me as much as I depend on him/her. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This pharmacist and I are mutually dependent on each other in caring for patients. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This pharmacist and I negotiate to come to agreement on our activities in managing drug therapy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I will work with this pharmacist to overcome disagreements on his/her role in managing drug therapy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I intend to keep working together with this pharmacist. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| I trust this pharmacist’s drug expertise. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Communication between this pharmacist and myself is two-way. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This pharmacist has spent time trying to learn how he/she can help you provide better care. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This pharmacist has provided information to you about a specific patient. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| This pharmacist has showed an interest in helping you improve your practice. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Appendix 3

Pharmacist interview guide

Relationship initiation questions

How did you begin to work with physicians?

What were some of the challenges you faced?

How did you choose the physicians to work with?

What was your vision for the relationship?

How did you determine the physician’s needs?

How did you go about meeting those needs?

How would you describe your relationship with physicians when you first began to provide patient care?

How has this relationship changed?

Compare and contrast your early relationships with current ones. Have you done anything differently?

Trustworthiness questions

How important do you feel trust is to relationship development with the physicians with whom you work?

Why do you think physicians trust you?

Why do you trust physicians?

How was this trust established?

How has this trust been maintained?

Role specification questions

How would you describe your role in patient care?

If you think of 2 physicians with whom you work—one with whom you work closely [physician A] and the other with whom you work less closely [physician B]: How does your role differ from that of the physician [A] or [B] with whom you work? Why do you think your role differs among physicians?

Who determines the role each of you play?

Who initiates contact between the 2 of you or any given patient?

How do you maintain your patient care relationship?

How has your role changed over time?

How would your patients describe the work you do?

Appendix 4

Physician interview guide

Relationship initiation questions

How did you begin to work with pharmacists?

What were some of the challenges you faced?

How did you choose the pharmacists to work with?

What was your vision for the relationship?

How did you determine the pharmacist’s needs?

How did you go about meeting those needs?

How would you describe your relationship with pharmacists when you first began to provide patient care?

How has this relationship changed?

Compare and contrast your early relationships with current ones. Have you done anything differently?

Trustworthiness questions

How important do you feel trust is to relationship development with the pharmacists with whom you work?

Why do you think pharmacists trust you?

Why do you trust pharmacists?

How was this trust established?

How has this trust been maintained?

Role specification questions

How would you describe your role in patient care?

If you think of 2 pharmacists with whom you work—one with whom you work closely [pharmacist A] and the other with whom you work less closely [pharmacist B]: How does your role differ from that of the pharmacist [A] or [B] with whom you work? Why do you think your role differs among pharmacists?

Who determines the role each of you play?

Who initiates contact between the 2 of you or any given patient?

How do you maintain your patient care relationship?

How has your role changed over time?

How would your patients describe the work you do?

Footnotes

Financial isclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest or financial interests in any product or service mentioned in this article, including grants, employments, gifts, stock, holdings, or honoraria.

Previous Presentations: This study was presented previously at the American Pharmacists Association Annual Meeting, March 18, 2007, Atlanta, Georgia, and at the 2007 Eastern States Pharmacy Residency Conference, May 11, 2007, Baltimore, Maryland.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare prescription drug benefit final rule. [Accessed January 4, 2010];Federal Register. 2005 January 28;vol. 70(no. 18):4279–4283. Available at: http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2005/pdf/05-1321.pdf. [PubMed]

- 2.American Pharmacists Association, National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication therapy management in pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service model. Version 2.0. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48:341–353. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.08514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD, et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 1999;281:267–270. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schumock GT, Meek PD, Ploetz PA, Vermeulen LC. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services—1988–1995. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16:1188–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cranor CW, Bunting BA, Christensen DB. The Asheville project: long term clinical and economic outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43:173–184. doi: 10.1331/108658003321480713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. JAMA. 2006;296:2563–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baggs JG, Ryan SA, Phelps CE, Richeson JF, Johnson JE. Comparing standard care with a physician and pharmacist team approach for uncontrolled hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:740–745. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lounsbery J, Green C, Bennett M, Pederson C. Evaluation of pharmacists' barriers to the implementation of medication therapy management services. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49:51–58. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.017158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonough RP, Doucette WR. Developing CWRs between pharmacists and physicians. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2001;41:682–692. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scanzoni J. Social exchange and behavioral interdependence. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social Exchange in Developing Relationships. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 61–98. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwyer FR, Schurr PH, Oh S. Developing buyer-seller relationships. J Mark. 1987 April;51:11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabarro JJ. The development of working relationships. In: Lorsch J, editor. Handbook of Organizational Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1987. pp. 172–189. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baggs JG, Ryan SA, Phelps CE, et al. The association between interdisciplinary collaboration and patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Heart Lung. 1992;21(1):18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baggs JG. Development of an instrument to measure collaboration and satisfaction about care decisions. J Adv Nurs. 1994;20(1):176–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20010176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH. Nurses’ and resident physicians’ perceptions of the process of collaboration in an MICU. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20:71–80. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199702)20:1<71::aid-nur8>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zillich AJ, McDonough RP, Carter BL, Doucette WR. Influential characteristics of physician/pharmacist collaborative relationships. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:764–770. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zillich AJ, Doucette WR, Carter BL, Kreiter CD. Development and initial validation of an instrument to measure physician-pharmacist collaboration from the physician perspective. Value Health. 2005;8:59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.03093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zillich AJ, Milchak JL, Carter BL, Doucette WR. Utility of a questionnaire to measure pharmacist-physician collaborative relationships. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2006;46:453–458. doi: 10.1331/154434506778073592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. 1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. pp. 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brock KA, Doucette WR. CWRs between pharmacists and physicians: an exploratory study. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:358–365. doi: 10.1331/154434504323063995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doucette WR, Nevins J, McDonough RP. Factors affecting collaborative care between pharmacists and physicians. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2005;1:565–578. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]