Abstract

Objective:

Allied health assistants (AHAs) are an emerging group in allied health practice with the potential to improve quality of care and safety of patients. This systematic review summarizes the evidence regarding the roles and responsibilities of AHAs and describes the benefits and barriers to utilizing AHAs in current health care settings.

Methods:

A systematic process of literature searching was undertaken. A search strategy which included a range of electronic databases was searched using key terms. Studies which examined the roles and responsibilities of AHAs (across all allied health disciplines) were included in the review. Only publications written in the English language were considered, with no restriction on publication date. Two reviewers independently assessed eligibility of the articles. Data extraction was performed by the same reviewers. A narrative summary of findings was presented.

Results:

Of the initial 415 papers, 10 studies were included in the review. The majority of papers reported roles performed by general health care assistants or rehabilitation assistants who work in multiple settings or are not specifically affiliated to a health discipline. All current AHAs duties have elements of direct patient care and indirect support via clerical and administrative or housekeeping tasks. Benefits from the introduction of the AHA role in health care include improved clinical outcomes, increased patient satisfaction, higher-level services, and more “free” time for allied health professionals to concentrate on patients with complex needs. Barriers to the use of AHAs are related to blurred role boundaries, which raises issues associated with professional status and security.

Conclusions:

There is consensus in the literature that AHAs make a valuable contribution to allied health care. Whilst there are clear advantages associated with the use of AHAs to support allied health service delivery, ongoing barriers to their effective use persist.

Keywords: allied health assistants, health care assistants, rehabilitation assistants, allied health workforce

Introduction

In recent years, there have been numerous changes in health care service delivery, increasing the pressure and demand placed on primary and secondary health care services, both nationally and internationally. There has also been a widespread move towards the implementation of health care practices underpinned by research evidence and guided by principles of safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity.1 Along with these changes are emerging issues related to the demographic shift, science and technological advancements, increased patient expectations, and a shortage of health care professionals. The international trend of an ageing population means that health care consumers are increasingly presenting with chronic and complex diseases. Patients’ expectations have changed as well, with patients becoming active participants rather than passive receivers of care. With these changes, health care services are increasingly faced with the need to ensure that there is an adequate number of health professionals and paraprofessionals who can provide the most appropriate and timely services to patients.

There is evidence that highly qualified health care providers are increasingly allocating tasks to other practitioners in order to allow management of patients with more complex conditions and needs.3,4 The boundaries between groups of health professionals are shifting, for example, between doctors and physiotherapists in orthopedic clinics. Specially trained physiotherapists work in an extended role by being involved with the assessment and management of referrals from orthopedic surgeons.5 This concept of extended scope practice combines “role enhancement” and “role substitution”. Role enhancement is defined as increasing the depth of the job by extending the roles or skills of a particular group of workers. Role substitution, on the other hand, involves expanding the breadth of a job in particular, by working across professional divides or exchanging one type of worker for another.6 Extended scope of practice has led to task redistribution resulting in other staff fulfilling roles traditionally performed by other health professionals.7,8

Currently, the health system is challenged to accommodate these changes in the workforce and to provide an adequate number of appropriately skilled health care workers to meet the changing needs of health care consumers and organizations. The development of the allied health assistant (AHA) role is one method to address these challenging issues of health care delivery. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the introduction of “assistant practitioners” to complement the work of professionals is one of the initiatives which emerged out of policies that encouraged modernization of the professions and challenged traditional working practices.9–12 Traditional health care professionals are increasingly allocating tasks to allied health assistants or support workers, freeing the highly qualified practitioners to manage clients with more complex issues.13–15

While there is an increasing recognition of the importance of the role of AHAs, to date there has not been a systematic analysis of this workforce. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to provide evidence on the roles and responsibilities of AHAs as reported in the literature, and where possible, briefly describe the benefits of and barriers to utilizing AHAs in current health care settings.

Methods

For the purpose of this review, an AHA is defined as a person who assists or provides any type of support to the work of a qualified allied health professional. Studies which reported AHAs or other terminologies such as generic assistants, community rehabilitation assistants, multidisciplinary assistants, therapy assistants/supports, aides, technicians and support workers aligned with defined allied health professional groups, and indigenous support workers, were included in this review. Because the aim of this systematic review was targeted towards allied health assistants particularly, publications which described people working in the paramedical ambulance context, medical assistants, physician assistants, nursing assistants, drug and alcohol support workers, and postnatal and midwifery support workers were excluded.

This systematic review considered only peer reviewed literature in which the primary objective or the main focus was related to the roles or responsibilities of an AHA. Articles which have training, education and supervision as their focus were excluded from this review. Only those publications which were written in the English language were included, and no publication date restrictions were set.

Search strategy

A three-step search strategy was utilized in this systematic review. An initial search using the key words “health care assistant, allied health assistant, and health technician” was done in Medline, followed by examination of the titles and abstracts of relevant hits to identify related terms and synonyms. A second extensive search using all identified search terms was then undertaken in all of the following databases: Cochrane, AMED, Medline, Ageline, Ovid, EMBASE, PEDro, PubMed, CINAHL, and Web of Science. An extensive list of key search terms, grouped into two key concepts, was utilized for literature searching. Concept one represented key words within the category “allied health”. Concept two represented key words within the category “assistant”. These two concepts were combined in the electronic search in order to capture the most number of relevant articles.

Concept One: Physiotherap*; Physical Therap*; Occupational Therap*; Speech Therap* or speech pathology*; Diet* OR nutrition*; Allied Health; Social work*; Podiatr*/chiropody; Radiograph*/medical radiation/diagnostic imaging/nuclear medicine; Indigenous worker OR Aboriginal support workers; Audiology; Prosthetic* OR orthotic*; Pharmacy; Psychology; Orthoptic*.

Concept Two: Support work*; Health work*; Assistant Aid*; Technician; Helper; Health care assistant; Auxiliary personnel.

Finally, the reference lists of retrieved papers were scrutinized for additional studies that may not have been indexed in any of the electronic databases.

Selection of studies

The titles and abstracts identified from the above search strategy were independently assessed by the first two authors (LL, SK). Full texts of potentially relevant papers were then retrieved for a more detailed examination. The decision to include or exclude studies based on the criteria set was made independently by the same authors. Differences in opinion regarding adherence to inclusion criteria were resolved by discussion.

The methodologic quality of the included papers was not examined for two reasons. First, this review was aimed at exploring the evidence regarding the roles and responsibilities of AHAs rather than a review of evidence of effectiveness. Second, the diversity of the evidence sources found for this review did not allow the reviewers to identify a critical appraisal tool which would be applicable to a range of study designs.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from each of the included studies, such as author, year of publication, type of study, country of origin, roles and responsibilities, barriers and benefits of introducing AHA in the health workforce. A narrative summary of the synthesized findings is presented.

Results

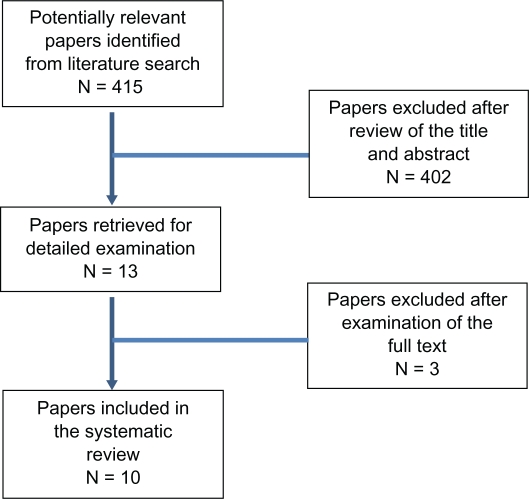

The electronic search yielded a total of 896 citations from the databases searched. After removal of duplicate records, there were 415 potentially eligible papers for inclusion. All 415 papers were evaluated for inclusion by the two reviewers based on title and abstract. A total of 402 were found to be irrelevant to this review. Reasons for exclusion included not satisfying the inclusion criteria (n = 365), focused on education, training and competencies (n = 31), and related to supervision and ethical standards (n = 15). Thirteen papers were retrieved for full examination, three of which discussed the roles of nursing assistants and were therefore excluded. The reference lists of the 10 included papers were carefully examined for additional literature. No further studies were found eligible, yielding a total of 10 papers for this systematic review. Figure 1 illustrates the process involved in the selection of articles for review.

Figure 1.

Publication selection process.

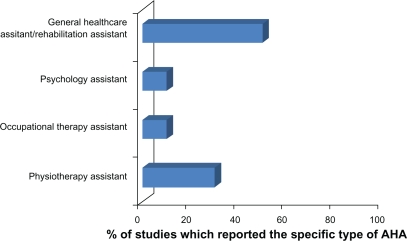

Types of allied health assistants

There was a great deal of variability in the retrieved literature regarding the affiliation of AHAs with the different allied health professions. As indicated in Figure 2, the majority of papers were related to the roles performed by general health care assistants or rehabilitation assistants who worked in multiple settings or were not specifically affiliated to a health discipline.

Figure 2.

Health discipline affiliation of assistants.

The majority of reported roles concerned AHAs in outpatient and community care settings. Discipline-specific studies that have analyzed the workforce have identified that the largest percentage of AHAs are employed in the geriatric field, although a variety of clinical settings have also been utilized. These include acute care, pediatrics, acquired brain injury, and orthopedics. There is a range of generic or multidisciplinary support worker roles within the context of acute, intermediate, and community care.

A brief summary of the main findings from individual studies considered in the review is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of findings from individual studies

| Author, Date | Type of Study | Country | Role | Barriers | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General health care assistant/rehabilitation assistant | |||||

| Conway and Kearin16 | Survey | Australia |

|

|

|

| Lin et al17 | Survey | Australia |

|

||

| Pullenayegum et al18 | Audit | UK | Assists in speech therapy

|

Rehabilitation assistants provide consistent and goal-directed rehabilitation to patients who received treatment from a multidisciplinary team | |

| Stanmore and Waterman19 | Qualitative ethnographic | UK |

|

||

| Knight et al20 | Mixed | UK |

|

|

|

| Nancarrow et al21 | Survey | UK |

|

||

| Psychology assistant | |||||

| Woodruff and Wang22 | Mixed (survey, literature review and qualitative) | UK |

|

||

| Occupational therapy assistant | |||||

| Nancarrow and Mackey23 | Qualitative approach | UK |

|

|

|

| Physical therapy assistant | |||||

| Conti et al24 | Narrative | US | Facilitates treatment plan by physiotherapist | Successful patient outcomes: skin breakdown rates decreased, average ventilator days per patient and pneumonia rate declined, complete continuity of therapy, early intervention of each patient and family, a dramatic increase in mobilization and overall fewer complications | |

| Ellis et al25 | Survey | UK | Tasks routinely performed by more than 75%

|

||

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; OT, occupational therapist; UL, upper limb; LL, lower limb; ROM, range of movement.

Findings for each type of allied health assistant

General health care assistant/rehabilitation assistant

Conway and Kearin surveyed 21 assistants, and their results have shown consistency in the activities they most frequently performed.16 These included bulk cleaning, general assistance or housekeeping duties and providing physical assistance to nurses, medical, and physiotherapy staff, primarily for manual handling of heavy or difficult patients. These tasks are devoid of direct therapy or clinical components. In another survey, 98 multidisciplinary therapy assistants practicing in rural and remote areas participated in the study.17 Therapy assistants provided assistance to allied health professionals, and spent time on different program delivery such as individual therapy, group therapy, administration duties, and health promotion. Similar findings were reported by Pullenayegum et al following a small scale audit to assess the role and effectiveness of rehabilitation assistants.18 The assistants operated only on weekends to maintain the rehabilitation process over a seven-day period. The role of a rehabilitation assistant was created after a negative change in a patient’s condition (mobility, motivation, and attitude towards rehabilitation) was observed by nurses and therapy staff when therapy ceased over the weekend. Their responsibility was to facilitate the carry-over and maintenance of the rehabilitation program.

A qualitative, ethnographic approach was undertaken by Stanmore and Waterman to examine the role of rehabilitation assistants.19 A total of 55 semistructured interviews of patients, associated professionals, and rehabilitation assistants were conducted to examine this new role. Common elements of the role, irrespective of workplace or organization, included working with patients towards individual rehabilitation goals, supporting and supervising patients in activities of daily living, carrying on therapy as delegated by professionals, promoting independence, promoting patients’ rights and identity, monitoring progress, providing feedback to professionals on patient progress and service provision, assisting clinicians in the safe use of equipment for patients/carers, and maintaining records of work undertaken with patients. Variations in the role appeared to be a consequence of the demands of the organizational context and the relationships between rehabilitation assistants and the associated professionals and support staff.

A descriptive evaluation using a case study approach of 13 rehabilitation assistants was carried out by Knight et al.20 The assistants’ roles in different rehabilitation teams (general medical, general surgical, hospital and community, orthopedics and rheumatology, outpatients, stroke, and vascular and general rehabilitation) mostly involved facilitating mobility, washing and dressing, and activities of daily living of patients. Whilst there were similarities in the tasks, the role of the rehabilitation assistant differed according to the team focus, structure, and process within which the team operated. There were some assistants who were required to spend time on administrative duties which, in turn, reduced the time spent on clinical duties. An interesting finding from this study was that all of the rehabilitation assistants displayed the ability to operate at a level beyond simply following instructions and seemed to have a good overview of the rehabilitation process.

Support worker roles in intermediate care were reported by Nancarrow et al.21 This study presented data from a survey of 33 intermediate care services which employed 794 support workers and 368 professionally qualified staff. The roles constituted working in multidisciplinary settings, meeting rehabilitation needs, providing personal care, and enablement. Some workers were also involved in providing administrative support.

Psychology assistant

Woodruff and Wang examined the roles and tasks of assistant psychologists through a functional job analysis which determined both functions within the organization (organizational analysis) and at the individual level (personal analysis).22 The roles included assisting in the provision of clinical psychology services, maintenance of equipment and resources, liaising with other staff, and audit activities. The authors have reported that while the roles of a psychology assistant were clearly articulated in the job description, in practice the roles varied a great deal due to the differing interpretations and perceptions of supervisors and managers. Another possible reason for the variation was the competency and experience of the psychology assistants themselves.

Occupational therapy assistant

Nancarrow and Mackey described the roles and responsibilities of the occupational therapy support worker.23 Focus group interviews with four groups of stakeholders, namely assistant practitioners (n = 5), supervisors (n = 5), managers (n = 4), and service users (n = 3) were conducted. The role changed according to the setting in which they worked (health or social care setting), their relationship with their supervising occupational therapist and the supervisory arrangement within the service. Discharge home visits were the only task identified that an assistant could not do. This task needs to be performed by an occupational therapist.

Physical therapy assistant

Conti et al described the role of a physical therapy assistant (PTA) who was a new inclusion in their critical care team.24 The PTA facilitated the treatment plan designed by the physical therapist and treated the patients daily. Similar findings were obtained by Ellis et al but in addition to direct patient care, PTAs also engaged in clerical/administration work, record keeping, and domestic tasks.25

Synthesis of roles and responsibilities

Overall, a narrative synthesis of the literature indicates that the roles of AHAs can be divided into two key categories, ie, clinical and nonclinical duties. Table 2 summarizes the different duties assumed by AHAs in each category. Clinical duties encompassed tasks which required direct patient contact, such as administration of clinical services, preparation of patients, patient education, and supervision of patients. It is not surprising to note that many of these duties undertaken by AHAs correspond to duties undertaken by allied health professionals as well. This is to be expected because assistants’ roles are inherently linked to the health professionals’ roles. Nonclinical duties, on the other hand, do not require direct patient contact and include administrative and clerical duties.

Table 2.

Clinical and nonclinical duties and responsibilities of AHAs as reported in the literature

| Clinical duties | Nonclinical duties |

|---|---|

|

|

Key terms used in describing AHA duties were assisting, supporting, administrating, monitoring, and maintaining. This was in stark contrast with the key terms used by allied health professional staff such as evaluating, assessing, diagnosing, planning, and implementing. Key terms used to denote AHAs’ duties in direct patient care are reflective of their scope of practice. Duties such as diagnosing and planning of treatments are beyond the scope of AHAs and are hence exclusive to allied health professionals.

Benefits of introducing AHAs within the allied health workforce

Positive changes to processes and outcomes of health care were reported as a result of introducing AHAs. Knight et al evaluated the role of rehabilitation assistants and found that the assistant’s role served to link all the disciplines within the multidisciplinary team and integrate community rehabilitation.20 The team leaders felt that inclusion of assistants in the team would improve the quality of service by being more patient-focused. Rehabilitation assistants, on the other hand, saw their role mainly as being organized to offer patients a more continuous, holistic and patient-focused service while at the same time allowing health professionals extra time to carry out more complex tasks. Similarly, the results of an evaluation conducted by Pullenayegum et al demonstrated the valuable contribution of rehabilitation assistants in providing consistent and goal-directed rehabilitation to patients who received treatment from a multidisciplinary team.18 Improved communication and interdisciplinary working between nurses, therapists, and rehabilitation assistants has created a well-coordinated and integrated approach to rehabilitation.

Improved outcomes were also described from patients and allied health professionals’ perspectives. Conti et al described the improvements in patient clinical outcomes as a result of the introduction of a physical therapy assistant in the critical care team.24 These included reduction in skin breakdown rates, ventilator days per patients, ventilator pneumonia rate, and overall fewer complications. In a qualitative study by Nancarrow and Mackey, patients expressed satisfaction with the amount of time spent with them by the staff member which was facilitated through the introduction of occupational therapy assistants.23 The ability to identify better with patients, because of a similarity in background and less use of complicated language, was also identified as contributing to improved patient satisfaction. From a health professional perspective, Nancarrow and Mackey reported reduced burden on occupational therapists because occupational therapy assistants could manage their own case load, which allowed them to undertake other tasks.23

Barriers to introduction of AHAs

The literature also points to key barriers associated with AHA roles. In the study by Nancarrow and Mackey, concerns were raised by supervising occupational therapists that assistant practitioners may be seen by service users as a cheap way of delivering occupational therapy services.23 Whilst the occupational therapists felt that they could benefit from delegating a wide range of tasks to the assistant practitioners, the roles were not clear enough to comfortably “let go” much of their work. Findings from a survey conducted by Conway and Kearin revealed the lack of clarity amongst staff in terms of the scope of the assistant’s role in supporting direct patient care.16 This could lead to an unrealistic expectation for AHAs to provide care for which they have had no training and/or which is beyond the scope of their role. There were other challenges voiced by assistants, such as being expected to achieve both allocated cleaning tasks and provide patient support, being requested to assist with aggressive patients, and working with other assistants. The issue of role confusion was also reported by Knight et al.20 These authors also highlighted other barriers, such as time management and feelings of inadequacy, due to the complex and often multidisciplinary nature of the work.

Discussion

The development of AHA roles has emerged as a response to meet the challenges associated with changes in health care demand and service delivery. The aim of this systematic review was to provide evidence on the roles and responsibilities of AHAs and the benefits and barriers to introducing AHAs in current health care settings. This review found consistent evidence that all current AHA duties have elements of direct patient care and indirect support via clerical and administrative or housekeeping tasks. This is similar to other assistant roles in health care such as nursing and medical assistants.26,27 Based on the evidence, the scope of practice for AHAs is limited to duties of assisting, supporting, monitoring, and maintaining rather than evaluating, assessing, diagnosing, and planning. These latter duties are typically expected of allied health professionals. The commonly reported duties that relate to direct patient care fit within this AHA’s scope of practice. The balance between direct patient care duties and indirect support varied considerably and was influenced by several variables, including work setting, the profession, the relationship between assistant and therapist, perceived competency of the AHA, and the organizational hierarchy. Recent initiatives in Australia to establish formal training and qualifications through registered training organizations for AHAs may minimize variability and formalize duties undertaken by AHAs.28

Evidence from the literature highlights health care benefits from introducing AHAs, in terms of both process and service outcomes. These include increased patient satisfaction, increased intensity of clinical care, more free time for allied health professionals to concentrate on complex tasks, and improved clinical outcomes. Some of these benefits have also been reported in the medical literature. Medical assistants were described to optimize patient flow which enables physicians to check more patients and conduct more robust visits.27 There are, however, some barriers to introducing AHAs in health care settings. These include ongoing uncertainty regarding the scope of AHA roles and responsibilities, protectionism of allied health professions, and feelings of inadequacy by AHAs themselves. Such concerns may have implications to the quality of care being delivered which may potentially affect patient safety. This is consistent with the barriers described by Bosley and Dale et al who reported that the boundaries between assistant and nursing roles are unclear and that the development of the health care assistant’s role challenges the nurse’s professional identity.2 A clear demarcation of the roles and responsibilities should therefore address the issue of professional status and security, which can lead to adequate and appropriate utilization of AHA services, and ultimately safe and high quality health care for patients.

Implications for policy and practice

The existing literature highlights many advantages associated with the use of AHA roles to support allied health service delivery. The employment of AHAs provides a strategic approach to dealing with current and projected allied health workforce shortages. However, there continues to be ambiguity in terms of role definition, accountability, and clarity. As the capacity of the allied health workforce requires expansion to meet the future needs of the community, these issues concerning AHAs need to be addressed.

This review also highlights the importance of recognizing local settings and contexts because AHA roles and responsibilities seem to be driven by local needs and organizational requirements. Therefore, a “one size fits all” approach may not be appropriate across all settings. Key determinants, such as staffing mix of AHAs and allied health professionals, need to consider local contexts.

Implications for research

Currently, there are significant knowledge gaps pertinent to AHAs and further research is required to address these gaps and inform policy and practice. Knowledge gaps include how AHAs are used to supplement, complement, or replace allied health professionals, the optimal mix of assistants to professional staff, impact on outcomes as a result of changing roles in patient care, and how best to ensure AHAs gain appropriate competencies.

Cost effectiveness of alternate workforce models which incorporate AHAs are rarely reported in the literature. It is important that future research consider cost effectiveness as an integral measure of outcome to demonstrate the impact (or lack thereof) of AHAs in the workforce.

Given the variety of roles assumed by AHAs, it is possible that the level of education and training received by AHAs is also variable. Future research should explore the competencies required for this practice and establish an educational program that utilizes a skills escalation framework that will provide career opportunities to AHAs.

It is apparent that much of the research underpinning AHAs is based upon small-scale, quality improvement (case study) approaches rather than large-scale, multicenter research initiatives. While large scale research initiatives are to be encouraged, small-scale case study approaches do provide key learnings for similar allied health settings and can contribute to the growing body of evidence for AHAs. Therefore, a mixture of small-scale case studies and large-scale multicenter studies are equally valuable.

Conclusion

There are different types of allied health assistants described in the literature and most of the evidence relates to the roles performed by rehabilitation assistants who are not exclusively affiliated with a health discipline. There is consistency in the literature regarding the roles assumed by AHAs, and these can be divided into clinical and nonclinical or administrative duties. There is emerging evidence that introduction of AHAs in the allied health workforce can improve the processes and outcomes of health care. However, barriers to their use persist and need to be addressed to maximize the benefits.

Acknowledgments

This review was commissioned by the Allied Health Workforce Reform Project – a collaborative project involving several government agencies and nongovernment organizations in the health and community services sectors in South Australia between February 2008 and November 2009. The project was managed by the South Australian Health and Community Services Skills Board, with the South Australian Health Allied and Scientific Health Office playing a leading role in project activities. The Allied Health Workforce Reform Project was jointly funded through the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, Targeting Skills Needs in Regions Programme, and the Department of Further Education, Employment, Science and Technology through the South Australia Works Initiative.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosley S, Dale J. Healthcare assistants in general practice: Practical and conceptual issues of skill-mix change. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(547):118–124. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X277032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardiner J, Wagstaff S. Extended scope physiotherapy. The way towards consultant physiotherapists? Physiotherapy. 2001;87(1):2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kersten P, McPherson K, Lattimer V, George S, Breton A, Ellis B. Physiotherapy extended scope of practice: Who is doing what and why? Physiotherapy. 2007;93(4):235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daker-White G, Carr AJ, Harvey I, et al. A randomised controlled trial: Shifting boundaries of doctors and physiotherapists in orthopaedic outpatient departments. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:643–650. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.10.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sibbald B, Shen J, McBride A. Changing the skill-mix of the healthcare workforce. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(1):28–38. doi: 10.1258/135581904322724112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woodford AJ. An investigation of the impact/potential impact of a four-tier profession on the practice of radiography: A literature review. Radiography. 2006;12(4):318–326. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPherson K, Kersten P, George S, et al. A systematic review of evidence about extended roles for allied health professionals. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11(4):240–247. doi: 10.1258/135581906778476544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health . Meeting the Challenge: A Strategy for the Allied Health Professions. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health . The NHS Plan (No CM 4818-I) London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health . HR in the NHS Plan – A Consultation Document. London: Department of Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Changing Workforce Programme . Developing Support Worker Roles in Rehabilitation in Intermediate Care Services. London: NHS Modernisation Agency; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson AJ, DePalma MT, McCall M. Physical therapist assistants’ perceptions of the documented roles of the physical therapist assistant. Phys Ther. 1995;75(12):1054–1066. doi: 10.1093/ptj/75.12.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper RA. Health care workforce for the twenty-first century: The impact of non-physician clinicians. Annu Rev Med. 2001;52:51–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.52.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford P. The role of support workers in the department of diagnostic imaging – service managers’ perspectives. Radiography. 2004;10:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conway J, Kearin M. The contribution of the patient support assistant to direct patient care: An exploration of nursing and PSA role perceptions. Contemp Nurse. 2007;24:175–188. doi: 10.5172/conu.2007.24.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin I, Goodale B, Vilanueva K, Spitz S. Supporting an emerging workforce: Characteristics of rural and remote therapy assistants in Western Australia. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15:334–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pullenayegum S, Fielding B, Du Plessis E, Peate I. The value of the role of the rehabilitation assistant. Br J Nurs. 2005;14(14):778–784. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2005.14.14.18556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanmore E, Waterman H. Crossing professional and organizational boundaries: The implementation of generic rehabilitation assistants within three organizations in the northwest of England. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(9):751–759. doi: 10.1080/09638280600902836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight K, Larner S, Waters K. Evaluation of the role of the rehabilitation assistant. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2004;11(7):311–317. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nancarrow SA, Shuttleworth P, Tongue A, Brown L. Support workers in intermediate care. Health Soc Care Community. 2005;13(4):338–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodruff G, Wang M. Assistant psychologists and their supervisors: Role or semantic confusion? Clin Psychol. 2005;48:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nancarrow S, Mackey H. The introduction and evaluation of an occupational therapy assistant practitioner. Aust Occup Ther J. 2005;52:293–301. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conti S, LaMartina M, Petre C, Vitthuhn K. Introducing a vital new member to the critical care team. Our physical therapy assistant. Crit Care Nurse. 2007;27(4):67–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellis B, Connell NAD, Ellis-Hill C. Role, training and job satisfaction of physiotherapy assistants. Physiotherapy. 1998;84(12):608–616. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thornley C. A question of competence? Re-evaluating the roles of the nursing auxiliary and healthcare assistant in the NHS. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9:451–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tache S, Chapman S. The expanding roles and occupational characteristics of medical assistants. J Allied Health. 2006;35:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chief Health Professions Office . Discussion Paper: Allied Health Assistants, Assistants in Allied Health and Health Science Workforce Project. Perth: Department of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]