Abstract

Background:

Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) is associated with psychological distress and long-term disability. Underlying diagnoses causing long-term sickness absence due to CMP have not been explored enough. In a somatic health care setting, it is important to identify mental health comorbidity to facilitate the selection of appropriate treatment. The objectives of this study were to compare the scores of depressed mood obtained on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) with the diagnosis of depression made by a psychiatrist, and to study the prevalence of undiagnosed mental health comorbidity in these patients.

Methods and patients:

83 consecutive patients on sick leave (mean duration 21 months) due to CMP who had been referred by the Social Insurance Office to an orthopedist and a psychiatrist for assessment of the patient’s diagnoses and capacity to work. The mean age was 45 (23–61) years, 58% were women and 52% were immigrants. The accuracy of measurements was calculated using the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV as the Gold standard.

Results:

Psychiatric illness was diagnosed in 87% of the patients. The diagnosis was depression in 56%, other psychiatric illnesses in 31%, whereas 13% were mentally healthy. Of all the patients, only 10% had a previous psychiatric diagnosis. The median value of the BDI score was 26 points in depressed patients, whereas it was 23 in patients with other psychiatric diagnoses. The sensitivity of the BDI to detect depression was 87.5%. We found good agreement between the BDI score and a diagnosis of depression.

Conclusion:

Undiagnosed psychiatric disorders were commonly seen in patients with CMP. The high sensitivity of the BDI scores enables the screening of mental health comorbidity in patients with a somatic dysfunction. The test is a useful tool for detecting distress in patients who are on long-term sick leave due to CMP and who need additional treatment.

Keywords: agreement, disability, underlying diagnoses

Introduction

Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) has been strongly associated with high test scores for psychological distress and fatigue.1 The main defining attributes of psychological distress are inability to cope, change in emotional state, experienced emotional discomfort, experienced harm, and symptoms of depression and/or anxiety.2 Between 40% and 100% of patients who attend primary health care with distress express more than 1 type of physical symptoms related to pain.3 In particular, depression predicts a poor outcome of treatment and disability in patients with CMP.4–6 Further, the perception of pain by patients with CMP determines a patient’s activity level and mood.7,8

Changing social and economic conditions, stress-related illness, and psychological problems have all been shown to explain the increasing number of patients with long-term sickness such as back pain in Sweden.9 In the presence of CMP and disability, underlying diagnoses causing long-term sick leave has not been explored enough.10,11 Therefore, in a somatic health care setting, it is important to identify mental health comorbidity, to select the appropriate treatment, and to facilitate return to work of patients with CMP.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) provides health care professionals with a practical tool to assess depression.12–16 The BDI score gives a measure of the severity of symptoms, which can be used to improve diagnosis and to select treatment.17 The instrument has excellent construct validity and internal consistency when assessing depression in chronic pain populations.18 However, little is known about the performance of the instrument to assess depression in patients on long-term sick leave due to CMP seen in a somatic health care setting.

Given that CMP is a complex complaint of major magnitude in Sweden, causing high cost, disability, and psychosocial detriment in these patients, it is important to screen the associated factors that contribute to delay the recovery of patients with CMP.

The aim of this study was to compare the scores obtained on the BDI with the diagnosis of depression made by a psychiatrist in this group of patients. Furthermore, we studied the prevalence of undiagnosed mental health comorbidity among patients on long-term sick leave due to CMP.

Methods

Patients

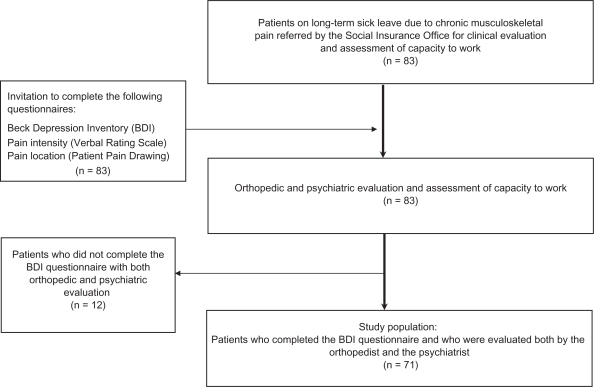

We carried out an observational study, namely a cross-sectional study. The Social Insurance Office in Göteborg referred 83 consecutive patients during the period 2003–2004, at the Capio Lundby Hospital, for an analysis of their biological and psychological functioning. The patients were recruited from the Västra Götaland region that includes the city of Göteborg. All patients were on sick leave due to a somatic (orthopedic) diagnosis. Most patients had been extensively investigated by their primary physician and by other specialists because of CMP. The Social Insurance Office had requested that the patients undergo a team assessment by an orthopedist and a psychiatrist to establish their diagnoses and capacity to work (Figure 1). The mean age of the patients was 45 (23–61) years, 47 (57%) were women and 43 (52%) were patients with a non-Swedish background. Of them, 25 (58%) were women. There was no difference for age by origin of the patients (t-test, P < 0.05). All the patients had been on sick leave for an average duration of 21 (3–96) months, due to CMP.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram 1.

Evaluation of sick-leave allowance

In Sweden, patients on long-term sick leave (which is defined as sick leave that exceeds 3 months) may be referred to one of the several diagnostic centers to establish the cause of their sickness absence, to estimate their capacity to work, to determine the sick leave allowance, and to follow a rehabilitation plan (www.socialstyrelsen.se).19 Normal work capacity is defined as either the ability to perform the same task, or the ability to earn the same income, as prior to sickness. Our study was part of a more extensive study that was approved by the Ethics Committee at the University of Göteborg Dnr 7–94. Only patients who could read and write Swedish were invited to complete all questionnaires before undergoing the clinical evaluation (Figure 1).

Orthopedic evaluation

All patients underwent a thorough orthopedic evaluation made by the orthopedist (Jorma Styf). Measurements of physical function included the range of motion (ROM) of the cervical and lumbar spine, and the motion of all major joints and all painful joints of the upper and lower extremities. Furthermore, imaging methods were taken into account in the physical evaluation. All patients had a diagnosis according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10. The main locations of pain causing disability were the neck and shoulders (76% of patients), the back (18%), and other locations in 6%. Most patients suffered from nonspecific cervicalgia (M54.2). Seventy-eight patients (94%) experienced pain also in a subsidiary location. The results of the physical examination and pain location have been published elsewhere.20

Assessment of depressed mood (BDI score)

The degree of depressed mood was measured by the BDI-1A.21–23 This version was a revision of the original instrument, published by Beck in 1971. The BDI provides a quantitative assessment of depressive symptoms, considering components of cognitive, affective, and behavioral distress in different populations as well as in patients with CMP.24,25 The BDI has excellent construct validity and internal consistency for psychiatric and nonpsychiatric populations.15–18,26 This score can be used to improve diagnosis and the selection of treatment.26 The BDI-1A version of the test is more popular than the BDI-II version, and its psychometric performance is satisfactory in different study populations.27 Nevertheless, several authors have argued that the BDI total score can be inflated, overestimating depression in patients with chronic pain because of the over-representation of certain somatic symptoms reported by these patients.28,29

One question in the full questionnaire that dealt with sexual activity was excluded for the whole study population. This has also been considered in previous studies.30 Thus, an item mean substitution method for the whole sample was performed.31

We compared the BDI scores, with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Disorders (SCID), the Swedish version,32 as the gold standard. The orthopedist and the psychiatrist were both blinded for each other’s findings and for the BDI-score. We applied the following BDI cutoff scores to classify depression in agreement with previous studies,25,32 below 13 for none or minimal depression, 14–20 for mild depression, 21–30 for moderate depression, and above 30 for severe depression.

Twelve patients of the 83, 5 were women and 5 were immigrants, did not answer the BDI questionnaire, leaving 71 patients in the sample (Figure 1). Five of the 12 patients were diagnosed with psychiatric conditions other than depression and 3 of the 12 patients with depression. Four of the 12 had no psychiatric illness.

Psychiatric assessment

Psychiatric illness was assessed by a psychiatrist (Torgny Persson) employing the SCID31 which investigated whether the patient’s syndrome fulfils the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode. The main clinical diagnoses found in our patients were major depressive episode (n = 40). Other main psychiatric diagnoses found: post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 6), psychosis (n = 1), stress syndrome (n = 2), adjustment disorder (n = 1), alcohol dependence (n = 3), pain disorder (n = 6), conversion disorder (n = 1), borderline personality disorder (n = 1), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (n = 1), and 9 patients had no psychiatric illness.

Statistical analysis

Data from the 71 patients who completed the BDI questionnaire and who underwent psychiatric and orthopedic evaluations were analyzed by statistical methods. Results are given as mean and median values and by categories (percentages). Groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskall–Wallis test, and categorical data were compared using the x 2 test. All P values reported are two-sided and significant at the 5% level (P < 0.05).

Assessment of the accuracy of measurements

The following indices of the accuracy, reliability, and validity were calculated in two groups: case 1 (total = 49): patients with only clinical depression (n = 40) compared with patients diagnosed not to have a psychiatric illness (n = 9); case 2 (total = 31): patients with psychiatric illness, ie, other than depression (n = 22) compared with patients diagnosed not to have a psychiatric illness (n = 9).

We calculated accuracy values, sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios for dichotomous tests (positive and negative) of the BDI questionnaire. The percentage agreements were calculated for the two cases described above, in order to test the diagnostic concordance between clinical depression or psychiatric illness diagnosed by the psychiatrist and mood determined by the BDI scores. The ratio between the number of items that agreed to the total number of observations gave the degree of agreement. Inter-rater agreement was determined by comparing the psychiatric diagnosis and the BDI scores, calculating Cohen’s kappa (κ) for categorical judgments. Inter-rater agreement was determined by carrying out the McNemar’s test which compares two diagnostic tests in the same sample of individuals (where P > 0.05 indicates inter-rater agreement). SPSS (version 17; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used in all statistical analyses.

Results

Orthopedic and psychiatric assessment

Normal neuromuscular function was observed in 69% (49/71) of the patients at clinical investigation. Minor impairment was found in 31% (22/71). Decreased joint ROM and muscular weakness were the impairments most commonly seen.

Psychiatric illness was diagnosed in 87% (62/71) of the patients. Different grades of major depressive episode, was the main diagnosis, being made for 56% (40/71) of these patients. Other psychiatric diagnoses were given for 31% (22/71) of the patients, whereas 13% (9/71) had no psychiatric illness (Table 1). The prevalence of psychiatric illness was not statistically different between patients with normal neuromuscular and joint function and patients with impairment (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.816).

Table 1.

Mean and median values of the BDI scores for groups having different psychiatric diagnoses (DMS-IV-RT) in patients with long-term sick leave due to chronic musculoskeletal pain

| Psychiatric diagnosis (number of patients) | BDI score (mean/median values) | Percentage of the total (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Depression (n = 40) | 28/26* | 17 |

| Mild (n = 12) | 20/20 | 33 |

| Moderate to severe (n = 24) | 29/29 | 6 |

| Extreme depression (n = 4) | 48/44 | |

| Other psychiatric diagnoses (n = 22) | 24/23 | 31 |

| No psychiatric illness (n = 9) | 18/21 | 13 |

| Total (n = 71) | 26/23** | 100 |

Notes:

Comparisons between degrees of clinical depression: Kruskall–Wallis and median test, p < 0.005;

Group comparisons: Kruskall–Wallis test, p < 0.01 (clinical depression and other psychiatric illness vs no psychiatric illness).

Abbreviation: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

Despite signs of prior presence of psychological illness in most of our patients, only 10% (7/71) of them had been diagnosed with psychiatric illness before this investigation. Thus, psychiatric illness was from the diagnostic point of view a hidden comorbidity in 89% (55/62) of the patients on sick leave due to CMP.

Assessment of depressed mood by the BDI

Depressed mood was seen in 83% (59/71) of the patients. The median values of the BDI score were 26 points for patients with clinical depression and 23 for patients with other psychiatric diagnoses. Patients with no psychiatric illness had 21 points. Patients with severe or moderate depression had higher scores of BDI than patients with mild or no depression (Kruskall–Wallis and median test, P < 0.005; Table 1). According to the BDI scores, 28% (20/71) of the patients were classified with the equivalent of severe depression, 27% (19/71) with moderate depression, 28% (20/71) with mild depression, and 17% (12/71) were not depressed nor had minimal depression (Table 2). Furthermore, scores on BDI exceeding 21 points were seen in 39/40 patients diagnosed by the psychiatrist with moderate or severe depression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparisons between the BDI scores and the diagnosis of depression or other psychiatric illness according to the psychiatrist in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain

| Levels of depression according to the BDI cut-scores (% of all patients with and without depression, n = 71) | Psychiatric diagnoses (DMS-IV-RT; % of all patients with and without depression, n = 71) |

|---|---|

| Severe depression: BDI >30 points | Depression |

| n = 20 (28%) | n = 40 (56%) |

| Moderate depression: BDI 21–30 points | |

| n = 19 (27%) | |

| Mild depression: BDI 13–20 points | Other psychiatric diagnoses |

| n = 20 (28%) | n = 22 (31%) |

| Minimal depression: BDI < 13 points | No psychiatric diagnosis |

| n = 12 (17%) | n = 9 (13%) |

Abbreviation: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

Assessment of the accuracy of measurements

Table 3 presents the distribution of the BDI scores for both cases of comparison among the psychiatric diagnoses. The accuracy and agreement were higher when screening depression (case 1) than they were when screening other psychiatric illnesses (case 2) as expected. The sensitivity of the BDI questionnaire to detect depression was 87.5% in case 1 and 86% in case 2 (Table 4). The specificity remained the same in both cases (<50%), whereas the accuracy was higher in case 1 compared with case 2 (82% vs 77%). According to the Positive likelihood ratio, higher scores on BDI (≥13) were 1.6 times more likely to occur in patients with depression, and in patients with other psychiatric diagnoses than in those with no psychiatric illness (Table 4). The agreement between the BDI score and the diagnosis of major depressive episode (SCID) was 80% (39/49) in case 1 and 74% (23/31) in case 2 (Table 4).

Table 3.

The psychiatric diagnoses and the distribution of the BDI score for case 1 and case 2 among patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain

| Psychiatric assessment | Case 1 Depression | No psychiatric illness | Case 2 Other psychiatric illness | No psychiatric illness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI cut-off | n = 40 | n = 9 | n = 22 | n = 9 |

| BDI ≥ 13 | 35 (72%) | 5 (10%) | 19 (61%) | 5 (16%) |

| BDI < 13 | 5 (10%) | 4 (8%) | 3 (10%) | 4 (13%) |

Notes: Case 1: depression compared with no psychiatric illness; case 2: other psychiatric illness irrespective of depression compared with no psychiatric illness. The figures given are percentages of the total within the group.

Abbreviation: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

Table 4.

Diagnostic analyses of the BDI scores and psychiatric evaluation in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain

| BDI cut-off point | Sensitivity (%) | LR (+)/LR (−)a | Percent agreement | Kappa (κ)b | McNemar test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | |||||

| BDI ≥ 13 | 87.5 | 1.58/0.28 | 80.0 | 0.32* | 2.6** |

| Case 2 | |||||

| BDI ≥ 13 | 86.0 | 1.55/0.31 | 74.0 | 0.33* | 0.69** |

Notes: Case 1: depression compared with no psychiatric illness (n = 49); case 2: other psychiatric illness irrespective of depression compared with no psychiatric illness (n = 31).

LR (+) = sensitivity/1-specificity; LR (−) = 1-sensitivity/specificity;

Cohen’s Kappa for dichotomous variables; McNemar’s test.

Statistically significant p < 0.05;

Statistically significant p > 0.05.

Abbreviation: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

Discussion

This study has shown that the BDI scores agree well with a psychiatric assessment of depression in orthopedic patients. Further, psychiatric disorders seem to be an important non-diagnosed comorbidity in patients on long-term sick leave due to a somatic diagnosis of CMP.

Assessment of depression by the BDI-scores

In the present study, the agreement between the psychiatric diagnosis of depression and the scores of BDI (BDI ≥ 13) was much better when depression was classified into three classes – mild, moderate, and severe – than it was when depression was defined simply as “minimal” in line with previous findings.16,21,32,33 Previous studies have shown that a psychiatric diagnosis of depression agrees well with BDI scores in patients with CMP.24,25 However, there is no previous study making this validation among patients on long-term sick leave due to CMP in a somatic health care setting.

Methodological considerations

The BDI test does not perform uniformly in nonclinical populations. Thus, higher BDI cut-off scores have been recommended to obtain the highest levels of sensitivity and specificity.34,35 We applied a cut-off value of 13 for the classification of depression rather than the original value of 10. This ensured that all groupings contained sufficient numbers of patients. Otherwise, the traditional sensitivity/specificity test methodology might have been problematic. Similar results (ie, high sensitivity and low specificity values) have been found using a BDI cut-off value of 13 points in patients with chronic pain.25,27 In this context, a good sensitivity appears to be indispensable according to several researchers.32,34,35 Furthermore, the high sensitivity of the BDI scores reduces the probability of false negatives, which may have serious consequences for orthopedic patients who need appropriate treatment for an undetected depression. In conclusion, our findings validate the BDI scores obtained by our patients. The BDI consists of two subscales, negative view and physical function. However, the results of the present study are based on the total BDI score. Consequently, we expect that the percentage agreement will improve only when the negative affect subscale is correlated with the psychiatric diagnosis of depression. Using the total BDI score as well as the high prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses may reduce the inter-rater agreement. It is documented, for instance, that the value of κ depends upon the proportion of subjects (prevalence) in each category.36 Nevertheless, the agreement in diagnosis in this study was high considering that the BDI score is a result of self-reported depression. Certainly, the BDI score can be exaggerated or minimized by the person completing it, as is also the case for other self-report inventories. Four of 9 patients had BDI scores that were greater than 21 points which is equivalent of moderate depression. However, psychiatric evaluation revealed no psychiatric diagnosis in these patients. This can possibly be explained first, because of the BDI score overestimation of depression previously referred28,29 second, when sickness-related pain and disability are at issue or in the context of symptoms medically unexplained.37

Psychiatric assessment

It is well known that the experience of pain is accompanied by emotional reactions. Emotions such as anger, frustration, fear, and sadness often occur simultaneously with depression in patients with CMP.14 The psychiatric evaluation in this study revealed that approximately 90% of patients who were sick-listed due to somatic diagnoses had mental health comorbidity that was not diagnosed before this consultation. A high prevalence of mental health comorbidity may be expected in other somatic health care settings which treat patients with CMP, and in other clinical settings of Social Insurance Medicine.38–41 Our study raises the question whether a substantial number of patients with unspecific CMP have been labeled and sick-listed under incomplete diagnoses. In this context, Sweden has the highest rate of morbidity and duration of sick leave caused by CMP in Europe.42 It is possible that sick leave reported in Sweden due to a diagnosis of CMP alone may be overestimated.

Limitations

It is possible that there are more immigrant patients among our patients than there are in the usual flow of patients in general clinical settings. Furthermore, our patients constitute a special cohort that had been on long-term sick leave and referred by the Social Insurance Office for clinical evaluation and assessment of capacity to work. Therefore, our results can be extrapolated only to similar patient populations in similar circumstances.

Clinical implications

Self-reported depression predicts disability. It is, therefore, important to identify mental health comorbidity in patients on long-term sick leave due CMP, in order to be able to select the appropriate treatment and facilitate a return to work. A biopsychosocial approach is helpful in recognizing comorbidity that is affecting the recovery process of these patients. This approach is necessary in a somatic health care setting for referring properly a patient with these symptoms. The majority of our patients were suffering from nonspecific musculoskeletal pain with an additional nondiagnosed psychiatric disorder.

Conclusion

The BDI score agrees well with a diagnosis of depression in patients on long-term sick leave due to CMP. The sensitivity of the BDI is good enough, to enable the orthopedist to detect symptoms of depression in the case that psychiatric assessment is not accessible. Nondiagnosed psychiatric disorder seems to be a prevalent problem among patients sick-listed for an extended period of time due to CMP.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.McBeth J, Macfarlane G, Hunt I, Silman A. Risk factors for persistent chronic widespread pain: a community-based study. Rheumatology. 2001;40:95–101. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ridner SH. Psychological distress: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(5):536–545. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stahl SM. Does depression hurt? J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):273–274. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currie SR, Wang J. Chronic back pain and major depression in the general Canadian population. Pain. 2004;107(1–2):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton A, Tillotson K, Main C. Psychosocial predictors of outcome in acute and subchronic low back trouble. Spine. 1995;20:722–728. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199503150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klenerman L, Slade P, Stanley I. The prediction of chronicity in patients with an acute attack of low back pain in a general practice setting. Spine. 1995;20:478–484. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199502001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leeuw M, Goossens ME, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JW. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med. 2007;30(1):77–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamé IE, Peters ML, Vlaeyen JW, Kleef M, Patijn J. Quality of live in chronic pain is more associated with beliefs about pain, than with pain intensity. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andren D. Long-term absenteeism due to sickness in Sweden. How long does it take and what happens after? Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8(1):41–50. doi: 10.1007/s10198-006-0005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudy T, Kerns R, Turk D. Chronic pain and depression: toward a cognitive-behavioral mediation model. Pain. 1988;35:129–140. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linton SJ, Andersson T. Can chronic disability be prevented? A randomized trial of a cognitive-behavior intervention and two forms of information for patients with spinal pain. Spine. 2000;25(21):2825–2831. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011010-00017. discussion 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aben I, Verhey F, Lousberg R, Lodder J, Honig A. Validity of the beck depression inventory, hospital anxiety and depression scale, SCL-90, and hamilton depression rating scale as screening instruments for depression in stroke patients. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(5):386–393. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.5.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wedding U, Koch A, Rohrig B, et al. Requestioning depression in patients with cancer: contribution of somatic and affective symptoms to Beck’s Depression Inventory. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(11):1875–1881. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estlander AM, Knaster P, Karlsson H, Kaprio J, Kalso E. Pain intensity influences the relationship between anger management style and depression. Pain. 2008;140(2):387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morley S, Williams AC, Black S. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Beck Depression Inventory in chronic pain. Pain. 2002;99(1–2):289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter P, Werner J, Heerlein A, Kraus A, Sauer H. On the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory. A review. Psychopathology. 1998;31(3):160–168. doi: 10.1159/000066239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk DC. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review. Pain. 1992;49(2):221–230. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris CA, D’Eon JL. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory – second edition (BDI-II) in individuals with chronic pain. Pain. 2008;137(3):609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogstedt CBM, Marklund S, Palmer E, Theorell T. Den höga sjukfrånvaron – sanningen och konsekvens. Stockholm, Sweden: Sandviken Publisher; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olaya-Contreras P, Styf J. Illness behavior in patients on long-term sick leave due to chronic musculoskeletal pain. Acta Orthop. 2009;80(3):380–385. doi: 10.3109/17453670902988352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT, Steer RA. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol. 1984;40(6):1365–1367. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198411)40:6<1365::aid-jclp2270400615>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner JA, Romano JM. Self-report screening measures for depression in chronic pain patients. J Clin Psychol. 1984;40(4):909–913. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198407)40:4<909::aid-jclp2270400407>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geisser ME, Roth RS, Robinson ME. Assessing depression among persons with chronic pain using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory: a comparative analysis. Clin J Pain. 1997;13(2):163–170. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199706000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT, Guth D, Steer RA, Ball R. Screening for major depression disorders in medical inpatients with the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(8):785–791. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bedi RP, Maraun MD, Chrisjohn RD. A multisample item response theory analysis of the Beck Depression Inventory-1A. Can J Behav Sci. 2001;33(3):176–187. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pincus T, Santos R, Morley S. Depressed cognitions in chronic pain patients are focused on health: evidence from a sentence completion task. Pain. 2007;130(1–2):84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams AC, Richardson PH. What does the BDI measure in chronic pain? Pain. 1993;55(2):259–266. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90155-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrne BM, Stewart SM, Lee PWH. Validating the Beck Depression Inventory-II for Hong Kong community adolescents. Int J Testing. 2004;4:199–216. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Downey RG, King C. Missing data in Likert ratings: A comparison of replacement methods. J Gen Psychol. 1998;125:175–191. doi: 10.1080/00221309809595542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herlofson J, Landqvist M. Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim Press; 2002. MINI-D IV: diagnostiska kriterier enligt DSM-IV-TR/[översättning till svenska] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steer RA, Cavalieri TA, Leonard DM, Beck AT. Use of the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care to screen for major depression disorders. Gen Hos Psychiatry. 1999;21(2):106–111. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turk DC, Melzack R. Handbook of Pain Assessment. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammond S. An IRT investigation of the validity of non-patient analogue research using the Beck Depression Inventory. Eur J Psychol Assess. 1995;11(1):14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newman TB, Kohn MA. Evidence-based Diagnoses. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2009. p. 87. First published 2009 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greer J, Halgin R. Predictors of physician-patient agreement on symptom etiology in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(2):277–282. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000203239.74461.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyrehag LE, Widerstrom-Noga EG, Carlsson SG, et al. Relations between self-rated musculoskeletal symptoms and signs and psychological distress in chronic neck and shoulder pain. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1998;30(4):235–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: the predictive validity of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain. 2003;19(2):80–86. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200303000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lundberg U. Stress responses in low-status jobs and their relationship to health risks: musculoskeletal disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:162–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bergstrom G, Bodin L, Bertilsson H, Jensen IB. Risk factors for new episodes of sick leave due to neck or back pain in a working population. A prospective study with an 18-month and a three-year follow-up. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64(4):279–287. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):287–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]