Abstract

Background

Early identification of individuals at risk of developing persistent pain is important to decrease unnecessary treatment costs and disability. However there is scant comprehensive information readily available to assist clinicians to choose appropriate assessment instruments with sound psychometric and clinical properties.

Objective

A national insurer commissioned the development of a compendium of assessment instruments to identify adults with, or at-risk of developing, persistent pain. This paper reports on the instrument identification and review process.

Methods

A comprehensive systematic literature review was undertaken of assessment instruments for persistent pain of noncancer origin, and their developmental literature. Only assessment instruments which were developed for patients with pain, or tested on them, were included. A purpose-built ‘Ready Reckoner’ scored psychometric properties and clinical utility.

Results

One hundred sixteen potentially useful instruments were identified, measuring severity, psychological, functional and/or quality of life constructs of persistent pain. Forty-five instruments were short-listed, with convincing psychometric properties and clinical utility. There were no standard tests for psychometric properties, and considerable overlap of instrument purpose, item construct, wording, and scoring.

Conclusion

No one assessment instrument captured all the constructs of persistent pain. While the compendium focuses clinicians’ choices, multiple instruments are required for comprehensive assessment of adults with persistent pain.

Keywords: persistent pain, assessment, psychometric properties, evidence-base, clinical utility

Background

An evidence-based practitioner integrates the best available research evidence with clinical judgment and patient preferences, when assessing and treating.1 Standardized assessment instruments are available for many health conditions. These initially served as checklists for health practitioners to consider essential elements in history taking.2 Nowadays, they are used to predict disability, assess risk, and identify appropriate treatment strategies.2–4 A comprehensive health assessment should incorporate information from relevant standardized instruments with a sound history, clinical tests and clinical judgment.1–4

This paper deals with assessment instruments for ‘persistent’, or ‘chronic pain’. Different health care providers use different philosophies and techniques when assessing patients with extended pain histories.2–4 Siddall and Cousins5 defined ‘persistent (or extended) pain’ as “pain that exists beyond three months” (p. 511), a definition recently reiterated by Cousins.6 However Blyth, Cousins, and colleagues applied a similar definition to ‘chronic pain’.7–10 For this paper, we use the term ‘persistent pain’ to identify “pain that persisted beyond expected healing times.”

Inappropriate treatment for patients with persistent pain results in higher costs.9–11 There is convincing evidence that early identification of patients at-risk of developing persistent pain reduces disability and increases return-to-work rates.9–14 This paper reports on a systematic literature review that identified and critically appraised assessment instruments for persistent pain. The review was commissioned by the New Zealand Accident Compensation Corporation, New Zealand’s sole, 24-hour, no fault injury insurer and rehabilitation purchaser. This organization is committed to providing health care providers with evidence-based resources. The outcome of this review was a compendium of high quality assessment instruments to assist health practitioners to identify patients with, or at risk of, persistent pain.

Methods

Project purpose

The systematic literature review identified psychometrically sound, clinically-useful assessment instruments for persistent pain, for use by multidisciplinary health care teams, or individual practitioners, in face-to-face or telephone situations, and in different locations (large hospitals, rural practices, primary and secondary health care environments).

Reference group

An expert multidisciplinary reference group assisted the literature review team.

Search strategy

A comprehensive approach was taken to identify persistent pain assessment instruments (Appendix 1). The search identified 1) any published questionnaire, survey, instrument or rating scale developed primarily to assess persistent (noncancer) pain in adults, as well as instruments which had been developed for other purposes, and subsequently tested on this patient group and 2) relevant peer-reviewed published background literature for each identified instrument.

Background literature

Developmental literature reported the instrument’s psychometric properties. This usually reflected results of psychometric testing, the instrument’s performance with different patient groups, and/or validation of instrument translation in other languages. Epidemiological literature reported threshold/cut points or population norms from population-application of the instrument.

Exclusion criteria

Instruments were excluded if they dealt with specific health conditions or body areas, were unavailable in English, were not fully described for clinical application, did not specifically assess noncancer persistent pain, and/or had no background literature.

Critical appraisal

Psychometric properties are reported and interpreted differently.2–4 Terminology differs depending on health discipline, philosophy of pain mechanisms, the research paradigm used, the purpose of testing, and common usage. This review applied a published classification of psychometric tests for consistency of interpretation.4

Project-specific scoring system

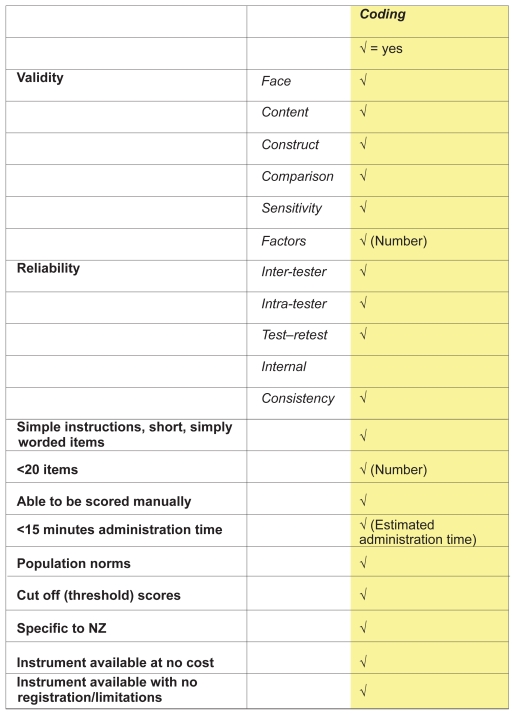

The lack of any published scoring system to rate the quality of assessment instruments for psychometric properties and clinical utility prompted the development of a purpose-built scoring system for this review (Ready Reckoner). This system gave equal weighting to 19 elements of psychometric properties and clinical utility (total score 19) (Figure 1), comprising:

Figure 1.

Ready Reckoner developed to review persistent pain assessment measures.

Evidence of validity testing (face, content and construct validity, sensitivity, factor analysis)

Evidence of reliability testing (inter-tester, intra-tester, test–retest, internal consistency)

Availability of instructions for administration, and ease of literacy

Efficiency of administration using limited number of items

Capacity of manual score

Efficient (short) instrument administration time

Published thresholds/cut points, and/or normative values, specific (or able to be extrapolated) to New Zealand (NZ) persistent pain patients

Relevance to NZ clinical settings, and

No cost, and/or no professional membership, instrument registration or training requirements.

Instrument identification, assessment, and short-listing

Step 1: Finding and collating instruments

A comprehensive list of potentially relevant assessment instruments was identified from iterative searches of the literature following discussions between the project team and expert reference group.

Step 2: Preparation for short-listing

The Step 1 instruments were reviewed and considered for short-listing (Step 3) if they met these conditions:

The instrument was primarily reported for assessment, rather than outcome measurement

At least four psychometric property measures were reported in background literature (reflecting any testing for validity, reliability, sensitivity, factor analysis or comparison with other measures)4

The instrument authors could be contacted.

Step 3: Short-listing

The purpose, psychometric properties, and clinical utility of each instrument was critically considered using the reporting framework4 and the Ready Reckoner. Instruments which survived Step 3 were included in the compendium.

Results

Overview

Instrument classification

Assessment instruments were classified into the category that best described their purpose. These classifications were largely self-reported from the background literature, and comprised pain severity, psychological, functional, or multidimensional assessment of persistent pain, and general health status/quality of life.

Instrument inclusion

Step 1 identified 116 instruments from approximately 350 publications (see row 1 of Table 1, and Appendix 2). In four instrument classification categories, sub-groups of specific instrument purpose were identified.

Table 1.

Consort diagram of instrument inclusion at each step

| Pain severity | Psychological | Functional | Multidimensional | General health/Quality of life | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | CPG, DN4, IDPain, LANSS, LF-MPQ, SF-MPQ, NPQ_LF, NPQ_SF, NPS, NPSI, Unidimensional VAS, NRS, VRS | BDI, BPCI, BPP, CCSI-R, CES-D, CPAQ, CPCI_65, CPCI partner, CPCI_42, CPCI_ abbreviated, CPS-ES, CPVI, CRPP, CSQ_50, CSQ_24, CSQ_R(27), CSQ_abbrev, DAPOS, DRAM, FABQ, FAPS, FPC, HADS, INTRP, K10, MLPC, MPRCQ, MSPQ, PAIRS, PAQ-R, PASS-40, PASS-72, PASS-SF, PBC, PBPI, PBQ, PCI, PCL, PCQ, PCS, PCS-S, PCSI, PDI, P3, PSCQ, PSEQ, PaSolQ, PVAQ, SCL-27, SOPA-35, SOPA-57, SOPA-short, TSK, TSK-11, VMDPMI, ZSRD | BPI_I, COPM, FACS, FASQ, FIE, FIPS, IFS-CP, KSMBJC, OccRQ, PDI, PDQ, PGPQ, PSFS, RADL, RFQ, SRI, WL_26, WLQ | BPI, BPI_SF, DPQ, GPQ, HBQ-P, HIPSPSQ, MRFA, ORQ, ÖMPSQ, PCOQ, PCP:S, PCP:EA, POP, POQ, POQ-42, POQ-SF, POQ-DC-28, POQ-FU-34, POQ-DC-5, VDPQ, WDDI, WHYMPI, WHYMPI_S | EQ-5D, HSQ, NHP, QWBS, WHOQOL, WHOQOLBref, SF-36, SIP | |

| Total | 11 | 56 | 18 | 23 | 8 | 116 |

| Step 2 | CPG, DN4, LANSS, LF-MPQ, SF-MPQ, NPQ_LF, NPQ_SF, Unidimensional | BDI, BPP, CES-D, CPAQ, CPCI_65, CPCI partner, CPCI_42, CPCI_abbreviated, CPVI, CRPP, CSQ_50, CSQ_24, CSQ_R(27), CSQ_abbrev, FABQ, HADS, K10, MPRCQ, MSPQ, PBC, PCI, PSEQ, TSK, TSK-11, ZSRD | BPI_I, COPM, FACS, FASQ, FIPS, OccRQ, PDI, PGPQ, PSFS, RADL, SRI, WL_26, WLQ | BPI, BPI_SF, DPQ, GPQ, ORQ, ÖMPSQ, WDDI, WHYMPI, WHYMPI_S | HSQ, NHP, SF-36, SIP | |

| Total | 8 | 25 | 13 | 9 | 4 | 59 |

| Step 3 | CPG, DN4, LANSS, SF-MPQ, NPQ_LF, NPQ_SF, Unidimensional | BDI, BPP, CES-D, CPAQ, CPCI_65, CPCI partner, CPCI_42, CPCI_abbreviated, CPVI, CRPP, CSQ_24, FABQ, HADS, K10, MSPQ, PBC, PCI, PSEQ, TSK-11, | BPI_I, COPM, FACS, FIPS, OccRQ, PDI, PGPQ, PSFS, RADL, SRI, WLQ | BPI_SF, GPQ, ORQ, ÖMPSQ, WHYMPI, WHYMPI_S | NHP, SF-36 | |

| Total | 7 | 19 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 45 |

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BPCI, Brief Pain Coping Inventory; BPI (BPI_SF), Brief Pain Inventory; BPI_I, Brief Pain Inventory-Interference; BPP, Biobehavioral Pain Profile; CCSI-R, Cognitive Coping Strategies Inventory- Revised; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale; COPM, Canadian Occupational Performance Measure; CPAQ, Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire; CPCI_65, CPCI_partner, CPCI_42, CPCI_ abbreviated, Chronic Pain Coping Inventory suite; CPG, Chronic Pain Grade; CPS-ES, Chronic Pain Self-efficacy Scale; CPVI, Chronic Pain Values Inventory; CRPP, Cognitive Risk Profile for Pain; CSQ_50, CSQ_R(27), CSQ24, CSQ_abbreviated, Coping Strategies Questionnaire; DAPOS, Depression, Anxiety and Positive Outlook; DN4, Douleur Neuropathique 4; DPQ, Dartmouth Pain Questionnaire; DRAM, Distress and Risk Assessment Method Pain; EQ-5D, EuroQol; FABQ, Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire; FACS, Functional Abilities Confidence Scale; FAPS, Fear Avoidance of Pain Scale; FASQ, Functional Assessment Screening Questionnaire; FIE, Functional Interference Estimate; FIPS, Family Impact of Pain Scale; FPC, Fear of Pain Comparisons; GPQ, Glasgow Pain Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HBQP, Health Background Questionnaire for Pain; HIPSPSQ, Hunter Integrated Pain Service (HIPS) Patient Screening Questionnaire; HSQ, Health Status Questionnaire 2.0; IFS-CP, Inventory of Functional Status – Chronic Pain; INTRP, Inventory of Negative Thoughts in Response to Pain; K10, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; KSMBJC, Kempsey Survey of Muscle, Joint and Bone Conditions; LANSS, Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs; MLPC, Multidimensional Locus of Pain Control Questionnaire; MRFA, Medical Rehabilitation Follow Along measure – Musculoskeletal Form; MPQ_LF, McGill Pain Questionnaire Long Form; MPQ_SF, McGill Pain Questionnaire Short Form; MPRCQ, Multidimensional Pain Readiness to Change Questionnaire; MSPQ, Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire; NHP, Nottingham Health Profile; NPQ_LF, Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire Long Form; NPQ_SF, Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire Short Form; NPS, Neuropathic Pain Scale; NPSI, Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; OccRQ, Occupational Role Questionnaire; ObsRWQ, Obstacles to Return-to-Work Questionnaire; ÖMPSQ, Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire; PAIRS, Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale; PAQ-R, Pain Attitudes Questionnaire-Revised; PASS, PASS-SF(20), PASS- 40, PASS-72, Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale; PBC, Pain Behavior Checklist; PBPI, Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory; PBQ, Pain Beliefs Questionnaire; PCI, Pain Coping Inventory; PCL, Pain Cognition List; PCOQ, Patient Centered Outcomes Questionnaire; PCP:S, PCP:ES, Profile of Chronic Pain: Screen, and Extended Assessment Battery; PCQ, Pain Cognitions Questionnaire; PCS (PCS_S), Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PCSI, Pain Coping Style Inventory; PDI, Pain Distress Inventory (in Psychological); PDI, Pain Disability Index (in Functional); PDQ, Pain Disability Questionnaire; PGPQ, Patient Goal Priority Questionnaire; POP, Pain Outcomes Profile; POQ, POQ-42, POQ-SF, POQ-DC-28, POQ-FU-34, POQ-DC-5, Pain Outcomes Questionnaire suite; PPP, Pain Patient Profile; PSCQ, Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire; PSEQ, Pain Self Efficacy Questionnaire; PSFS, Patient-Specific Functional Scale; PaSolQ, Pain Solutions Questionnaire; PVAQ, Pain Vigilance and Awareness Questionnaire; QWBS, Quality of Well-Being Scale – Self-Administered; RADL, Resumption of Activities of Daily Living Scale; RFQ, Risk Factor Questionnaire; SCL_27, Symptoms of Chronic Pain List; SF36, Short Form-36 Health Survey; SIP, Sickness Impact Profile; SOPA_57 SOPA_35 SOPA_S, Survey of Pain Attitudes; SRI, Spouse Response Inventory; TSK (TSK-11), Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia; VMDPMI, Vanderbilt Multidimensional Pain Management Inventory; VRS, Verbal Rating Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; VDPQ, Vermont Disability Prediction Questionnaire; WDDI, Work Disability Diagnosis Interview; WHOQOL, WHOQOL-Bref, World Health Organization Quality of Life; WHYMPI, WHYMPI_S, West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory; WL-26, Work Limitations-26; WLQ, Work Limitations-Questionnaire; ZSRD, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale.

For pain severity assessment, there were three sub-groups (uni-dimensional; multidimensional; neuropathic; and nonneuropathic pain discrimination).

For psychological assessment, there were nine sub-groups (general psychological states; anxiety, depression and mood; physiological manifestations of anxiety and depression relative to persistent pain; pain cognition; catastrophizing, negative thoughts and fear; risk factor identification; pain function; coping and management; and behavioral change readiness).

For functional assessment, there were six sub-groups (occupation focus; general function; interference [disability] in activities; impact on others; patient-specific instruments; and functional performance).

For multidimensional assessment of persistent pain, there were seven subgroups (occupational issues; expectations; yellow flags; pain dimensions; prediction of future disability; pain profiling; outcome prediction instruments).

No sub-groups were identified in the general health/quality of life instruments, as all measured similar constructs.

Step 2 retained 59 instruments. Appendix 3 outlines the excluded instruments and the primary reason for exclusion. Step 3 short-listed 45 instruments. Reasons for short-listing (or excluding) instruments at this step are outlined in the ‘Short-listing decisions’ section of this paper.

Table 1 outlines the review consort diagram. Instrument abbreviations are expanded in Appendix 2.

Psychometric properties

There was no consistency regarding research methods or statistics for psychometric testing. This constrained development of a general picture of psychometric performance, and questioned whether one statistic was preferable to another, in demonstrating desirable characteristics of instrument performance. Table 2 reports the frequency of psychometric statistical tests, and their reported purpose, from Step 2 (considering 59 instruments).

Table 2.

Frequency of use, and purpose, of statistics to describe psychometric property

| Test | Purpose | % | Test | Purpose | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cronbach’s alpha | Internal consistency | 56.4% | 13. Face validity | 7.3% | |

| 2. Student t-test/ANOVA | Responsiveness | 38.2% | 14. Kappa | Internal consistency | 5.5% |

| 3. Criterion validity | Concurrent and predictive | 32.7% | 15. Wilcoxin rank test | Responsiveness | 3.6% |

| 4. Construct validity | Convergent and divergent validity OR ability to differentiate between groups | 32.7% | 16. Spearman correlation coefficient | Inter-rater reliability | 1.8% |

| 5. Pearson r | Intra-rater reliability | 20.0% | 17. Spearman correlation coefficient | Test–retest | 1.8% |

| 6. Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) | Intra-rater reliability | 16.4% | 18. Percent agreement | Inter-rater reliability | 1.8% |

| 7. Cut point | Sensitivity and specificity | 16.4% | 19. Percent agreement | Test-retest | 1.8% |

| 8. Effect size | Responsiveness | 14.5% | 20. ICC | Inter-rater reliability | 1.8% |

| 9. Pearson r | Test–retest | 2.7% | 21. ICC | Internal consistency | 1.8% |

| 10. Pearson r | Internal consistency | 10.9% | 22. Pearson r | Inter-rater reliability | 0.0% |

| 11. Area under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve | Responsiveness | 9.1% | 23. Spearman correlation coefficient | Intra-rater reliability | 0.0% |

| 12. Kappa | Test–retest | 7.3% | 24. Percent agreement | Intra-rater reliability | 0.0% |

Short-listing decisions (Step 3)

Pain severity assessment instruments

Unidimensional scales

There is considerable detail regarding the psychometric properties of pain severity scales (Visual Analog Scale [VAS]/Verbal Rating Scale [VRS]/Numeric Rating Scale [NRS]).15,16 These instruments are useful for quick initial assessment of one pain dimension.

Multidimensional pain severity assessment instruments

The Chronic Pain Grade (CPG) scores the severity of persistent pain in three domains (characteristic pain intensity, disability, and persistence). The developmental literature17–21 provides evidence of strong psychometric properties in terms of high intra-rater reliability, internal consistency for a range of health conditions and construct validity compared to other instruments. Normative data is available.

The McGill Pain Questionnaire (Long Form) (LF-MPQ) has strong psychometric properties and normative data.22 It includes a univariate pain scale (NRS). The instructions for completing the pain adjectives section are complex and it is recommended that they should be read to patients. There are several methods of scoring, and little information as to which is most appropriate. The McGill Pain Questionnaire (Short Form) (SF-MPQ)23 does not contain the long-form body chart, and includes a VAS rather than an NRS. The short form version is less complex, quicker to administer and easier to score and interpret than the LF-MPQ. It covers the main elements of the LF-MPQ, and thus would appear to be preferable.

Distinguishing between neuropathic and nonneuropathic pain

Self-report and interview administration

The Douleur Neuropathique 4 Questions (DN4) is a 10-item instrument with high inter-rater reliability, high Kappa on retest, strong face validity and moderate correlation with health practitioners’ diagnosis.24–26 An interview contributes three items, using Yes/No responses, the remainder using a 0–100 scale. This instrument is appropriate for telephone administration.

Self-report and consultation administration

The Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) Pain Scale is a seven-item instrument which includes five self-report items and two sensory tests.27 The self-report questions use Yes/No responses, and the sensory testing requires the health practitioner to be with the patient for testing. Literature reports moderate Kappa test-retest scores and moderate Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency.27–31 Its cut-point of 12 is sensitive (83%), and specific (87%) for differentiating between neuropathic and nonneuropathic pain.27 It assesses five types of pain (thermal, dysesthesia, paroxysmal, evoked and autonomic dysfunction), and is appropriate to primary health care settings.

Self-report administration

The Neuropathic Questionnaire, Long Form (NPQ_LF) is a 12-item self-report instrument.32 The NPQ_LF has sound discriminant capacity between different pain-type groups.26 Its cut-point of 0 is reported to be moderately sensitive (66.6%) and specific (74.4%).26 There is a short form of three items (NPQ_SF), reported to have similar psychometric properties and discriminant capacity.32

Table 3 reports the consistently high Ready Reckoner scores for the short-listed pain severity instruments with respect to psychometric properties and clinical utility.

Table 3.

Ready Reckoner for short-listed pain severity assessment measures

| CPG | DN4 | LANSS | MPQ_SF | NPQ_LF | NPQ_SF | Unidimensional | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validity | Face | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Content | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Construct | ✓ | |||||||

| Comparison | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Sensitivity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Factors | 2 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 1 | |

| Reliability | Inter-tester | ✓ | ||||||

| Intra-tester | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Test–retest | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Internal | ✓ | |||||||

| Consistency | ||||||||

| Simple instructions, short, simply worded items | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| <20 items | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| • Number of items | 7 | 10 | 7 | 17 | 12 | 12 | 1 | |

| Able to be scored manually | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| <15 minutes administration time | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| • Estimated average time to administer | 15 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 2 | |

| Norms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Cut off scores | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Specific to NZ | ||||||||

| No cost | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| No registration/limitations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Total ✓ | 12 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 13 |

Abbreviations: CPG, Chronic Pain Grade; DN4, Douleur Neuropathique 4; LANSS, Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs; MPQ_SF, McGill Pain Questionnaire Short Form; NPQ_LF, Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire Long Form; NPQ_SF, Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire Short Form.

Category 2: Psychological pain assessment instruments

The number and range of instruments in this category highlights the importance of considering the purpose, strengths and limitations of psychological assessment instruments prior to choosing the most appropriate one to use.

Anxiety, depression, and mood

The review found five relevant instruments measuring anxiety, depression and/or mood (Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], Kessler Psychological Distress Scale [K10], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS], Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [CES-D], Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale [ZSRD]). Preference was given to clinically flexible, multi-construct psychological instruments relevant to persistent pain, thus ZSRD (a generic measure of depression) was excluded from further consideration.

The BDI is a well established 21-item self-report rating inventory measuring characteristic attitudes and symptoms of depression and mood. It has high internal consistency for both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric patients.33 The BDI has comparable sensitivity and specificity with CES-D for persistent pain patients.

The K10 is a widely reported two-domain, 10-item measure of nonspecific psychological distress, primarily intended as a measure of mood, anxiety, and depression.34 Its developmental literature reported high sensitivity and specificity, internal consistency and intra-rater reliability. It has been used extensively in population surveys in Australia.35 The K10 is appropriate for primary health care settings, and for telephone delivery.

The CES-D is a 20-item measure of anxiety, depression, and depressed mood symptoms, with demonstrated sensitivity and responsiveness to change.36 It has been validated in different languages. It has shorter forms (CES-D-10 (10 item), Revised Form (eight item), Iowa Form (11 item) and Boston Form (10 item), however the original CES-D is the best researched.37,38

The HADS is a two-domain, 14-item measure designed to detect anxiety and depression, independent of somatic symptoms.39 The instrument has high internal consistency and strong correlations with quality of life measures (eg, Life Satisfaction Questionnaire). It has limited background literature for persistent pain patients. It has been validated in different languages. The HADS can only be used by psychologists with appropriate training.40

Physiological manifestations of anxiety and depression relative to persistent pain

The Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire (MSPQ) is a 13-item measure of heightened somatic and autonomic awareness related to anxiety and depression.41 It was developed to identify clinically significant psychological distress in patients with persistent back pain. It has strong internal consistency, evidence of convergent and divergent validity with measures of anxiety and depression (eg, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory [MMPI], ZSRD, LF-MPQ) and significant discriminant validity within different groups of pain sufferers.41,42 It is one of the few instruments linking physical and psychological symptoms and thus adds important information to persistent pain assessments. It uses short wording which is appropriate for primary health care settings and telephone delivery.

Pain cognition and risk factor identification

No instrument was retained for short-listing.

Catastrophizing, negative thoughts, fear

Three instruments were retained for short-listing.

The Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) is a 16-item, short-worded, work-focused measure of patients’ beliefs about how physical activity and work affect their pain.43,44 The FABQ developmental literature reports high intra-tester reliability and test–retest, high internal consistency, and sound criterion and construct validity, tested against work time lost in the last 12 months, self-reported disability and poor behavioral performance. The FABQ is moderately correlated with the MSPQ, and highly correlated with the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-11).43 It is appropriate for primary health care settings and telephone delivery.

The TSK is available in long (17 items) and short (11 items) versions. Both instruments have similar high intra-rater reliability and internal consistency, and are sensitive to differences between patients, and interventions.45 The shorter version (TSK-11) is more relevant for primary health care assessment, and for telephone administration. The TSK has been validated in other languages.

The Pain Distress Inventory (PDI) measures pain-related interference with role functioning, using domains of family/home responsibilities, recreation, social activity, occupation, sexual behavior, self-care and life-support activity.46 It has sound internal consistency and content validity, and is sensitive to responses from different patient sub-groups. It correlates strongly with the Oswestry Disability Index and moderately with the BDI. The PDI is relevant to primary and secondary settings.

Behavioral change readiness

Four instruments were retained in this sub-group.

The Pain Behavior Checklist (PBC) is a 49-item, short-worded self-report about behaviors related to pain, assessing avoidance, complaint, and help-seeking.47 The PBC has moderate evidence of intra-rater reliability, low correlations with measures of depression, good discriminant validity between different types of headache sufferers, and low correlations with measures of noise sensitivity.47 Population norms reflect 1. 5 standard deviations around the mean.47,48

The Chronic Pain Values Inventory (CPVI) is a patient-centered six-domain instrument assessing family, intimate relations, friends, work, health, and growth or learning.49 The CPVI is based on a values-based cognitive-behavioral approach to assessing persistent pain. The developmental literature reports strong correlations with other pain measures (Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale [PASS], Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire [CPAQ], work capacity, and medications), and significant discriminant abilities.49 This instrument evaluates the discrepancy between importance and success in patient values related to functioning in different environments (family, intimate relations, friends, work, health and growth and learning).

The Multidimensional Pain Readiness to Change Questionnaire (MPRCQ) scored highly on psychometric properties (convergent and discriminant validity, intra-rater reliability and internal consistency). However, the authors advised that at present, this instrument was available only for research purposes.50 It was thus excluded from further consideration for the compendium.

The Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) is a 10-item short-worded instrument which measures self-confidence in performing functional and social activities, despite the presence of pain.51 The PSEQ is relevant to assess pain cognition in primary health care settings and can be administered by telephone. It has high intra-rater reliability, internal consistency and stability over retest.

Pain function, coping and management

Twelve instruments (six sets of instruments) were short-listed. Three measured persistent pain coping (Chronic Pain Coping Inventory [CPCI] suite of four instruments, Coping Strategies Questionnaire [CSQ] suite of four instruments, and the Pain Coping Inventory [PCI]). The other instruments comprised the CPAQ which measures acceptance of persistent pain, the Cognitive Risk Profile for Pain (CRPP) which considers persistent pain management beliefs, and the Biobehavioral Pain Profile (BPP) which measures reactions to persistent pain.

The CPCI suite (CPCI_65 [original], CPCI_partner, CPCI_42, CPCI_abbreviated) measures persistent pain coping strategies.52–54 The original CPCI includes domains of guarding, resting, asking for assistance, relaxation, task persistence, exercise/stretch, seek support, and coping self-statements. All versions of the CPCI demonstrate moderate to high internal consistency, and strong evidence of convergent, divergent and criterion validity tested within-instrument domains, and with other instruments (eg, CES-D and Numerical Pain Rating Scale [NRS]). An advantage of this instrument is its ‘partner’ version, and the shorter versions which may be used for primary care assessment, or for retest. The instruments have relatively complex wording which may not be appropriate for people of low literacy. The instrument has been validated in other languages.

The CSQ suite assesses persistent pain coping.55,56 It contains a long form (CSQ_LF of 50 items), a revised form (CSQ_R of 27 items) and an abbreviated 24 item form (CSQ-24). All forms have similarly strong internal consistency, and strong concurrent and divergent validity with VAS and HADS. The CSQ_LF and the CSQ_R are wordy, thus they may not be suitable for some persistent pain patients with low literacy. Scoring instructions are published for the abbreviated version, which appeared most appropriate for clinical use.

The PCI is a multi-domain, simply-worded 33-item instrument which measures active and passive pain coping strategies using specific cognitive and behavioral strategies (pain transformation, distraction, reducing demands, retreating, worrying, and resting).57 It has moderate intra-rater reliability and internal consistency, strong inter-domain correlation, and varying degrees of convergent and discriminant validity when compared with VAS, age, and illness states.

The CPAQ is a 20-item measure of pain acceptance.59 It has two domains that measure activity engagement (pursuit of life activities regardless of pain) and pain willingness (recognition that avoidance and control are often unworkable methods of dealing with persistent pain). Acceptance of persistent pain is believed to allow patients to focus on engaging in meaningful and valued activities and goals. The CPAQ demonstrates moderate internal consistency, and divergent validity with the BDI.59 This instrument uses wordy items which may not be suitable for self-report from patients with low literacy.

Persistent pain management beliefs

Persistent pain management beliefs could be measured by the nine domain instrument CRPP, or the BPP.

The CRPP is a commercially available instrument which explores beliefs and attitudes that could interfere with pain management.60 The CRPP domains deal with philosophic beliefs about pain, denial that mood affects pain, denial that pain affects mood, perception of blame, inadequate support, disability entitlement, desire for medical breakthrough, scepticism of multidisciplinary approach and conviction of hopelessness. It has high internal consistency, and divergent validity with the PDI, CSQ, and MPQ.

The BPP is a composite measure of behavioral, physiological, and cognitive reactions to pain.61 It has six domains of health care avoidance, physiological responsivity, thoughts of disease progression, environmental influences, past and current treatment, and loss of control. The initial intent of the instrument was to use each patient’s answers to create a profile that predicts what nondrug methods might work best for managing pain. In the developmental literature the BPP showed poor intra-rater reliability, high internal consistency, and divergent validity with the BDI and body consciousness.61 This instrument appears worded for patients of usual literacy levels.

Table 4 provides the Ready Reckoner scores for short-listed psychological persistent pain assessment instruments, and highlights their variable quality in terms of psychometric properties and clinical utility.

Table 4.

Ready Reckoner for the short-listed psychological persistent pain assessment measures

| BDI | BPP | CES-D | CPAQ | CPCI suite | CPVI | CRPP | CSQ_24 | FABQ | HADS | K10 | MSPQ | PBC | PCI | PSEQ | TSK-11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validity | Face | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Content | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Construct | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Comparison | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Sensitvity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Factors | 5 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Reliability | Inter-tester | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Intra-tester | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Test–retest | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Internal | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Consistency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Simple instructions, short, simply worded items | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| <20 items | (✓) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| • Number of items | 21 | 41 | 20 | 20 | 65 (abbrev) | 12 | 53 | 24 | 16 | 14 | 10 | 13 | 49 | 33 | 10 | 17 (11) | |

| Able to be scored manually | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| <15 minutes administration time | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| • Estimated average time to administer | 18 | 20 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| Norms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Cut off scores | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Specific to NZ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| No cost | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| No registration/limitations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Total ✓ | 14 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 8(9) | 9 | 4 | 10 | 14 | 9 | 14 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 13 |

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BPP, Biobehavioral Pain Profile; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale; CPAQ, Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire; CPCI suite, Chronic Pain Coping Inventory suite; CPVI, Chronic Pain Values Inventory; CSQ_24, Coping Strategies Questionnaire; FABQ, Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; K10, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; MSPQ, Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire; PBC, Pain Behavior Checklist; PCI, Pain Coping Inventory; PSEQ, Pain Self Efficacy Questionnaire; TSK-11, Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia.

Category 3: Functional performance assessment instruments

A range of instruments which purported to measure function in persistent pain patients were considered for short-listing.

Instrument redundancy

The Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) and the Work Limitations-26 (WL-26) were developed by the same group of researchers, and share over 90% items and wording.62,63 The WLQ is a 25-item measure of on-the-job impact of persistent health problems and/or treatment on work limitations (measuring capacity to work whilst workers are at work). The WLQ has four demand domains: physical, time, mental-interpersonal and output. It has been tested using a two and four-week recall period. It scores each item using a five-point Likert Scale: 0%, health makes the job demand difficult none of the time; 25%, a little of the time; 50%, some of the time; 75%, a great deal of the time; and 100%, health makes the job demand difficult all of the time. The WLQ correlates well with adverse events in the workplace such as employee injuries and sick leave. The instrument has high internal consistency and moderate criterion and construct validity with the Short Form Health-36 Survey Questionnaire (SF-36). It is useful for self-reporting. The WL-26 has 26-items of similar style, purpose and scoring to the WLQ. It defines the middle category on the Likert scale differently, as ‘approximately half the time’. Contact with the authors indicated that either instrument could be used to assess limitations in work functioning, however, they recommended the WLQ as the more robust measure. Both instruments require registration prior to use.

Occupation focus

Two instruments (WLQ and Occupational Role Questionnaire [OccRQ]) were identified, measuring different aspects of occupation. The OccRQ is an eight-item, two-domain instrument which tests attitudes to returning/remaining at work.64 It has two domains, assessing productivity and satisfaction. This instrument is suitable for self-report and administration in primary health care settings. The OccRQ has strong evidence of test-retest reliability and high internal consistency. It is moderately correlated with pain intensity (VAS).

General function

Three instruments were measures of general function, relevant in both primary and secondary health care settings: the 15-item Functional Abilities Confidence Scale (FACS), the 12-item Resumption of Activities of Daily Living (RADL) scale and the seven-item PDI.

The FACS measures confidence with general functional activities related to movements and postures affected by low back pain.65 The RADL measures self-reported resumption of usual daily activities estimating confidence regarding return to usual activities.66 These instruments were developed by the same research group, are strongly correlated, and have high internal consistency.

The PDI estimates impact on everyday activities and relationships.67 It is a measure of pain-related interference with role functioning, in domains of family/home responsibilities, recreation, social activity, occupation, sexual behavior, self-care and life-support activity. It is sensitive to responses from different patient groups, and correlates moderately with the BDI.

Patient-specific instruments

The importance of considering the patient’s perspective when measuring function was highlighted by Kliempt and colleagues.68 Two patient-specific instruments were identified, both with strong psychometric properties and tested across health conditions.

The Patient Goal Priority Questionnaire (PGPQ) is a patient-specific measure of patients’ behavioral goals.69 There are three measures: a questionnaire for assessing goals at baseline, a follow-up questionnaire, and a questionnaire for priority revision that can be used at any time after the commencement of treatment. The PGPQ can be used to identify and assess behavioral treatment goals, elaborate individual functional behavioral analyses relevant for everyday life functioning and determine the clinical signifiance of treatment. It is negatively and moderately correlated with the PDI, and is not intended for group analyses.

The Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS) is a patient-specific clinical tool for eliciting, measuring and recording patients’ descriptions of their disabilities.70 It has strong evidence of construct validity, intra-rater reliability, sensitivity and specificity, and has an estimated amount of clinically significant change.71,72

Interference (disability) in functional activities

Two instruments measured the extent of interference in usual function (measures of disability); the Functional Assessment Screening Questionnaire (FASQ) and the Brief Pain Inventory–Interference (BPI_I).

The FASQ is a simply-worded 15-item instrument.73 It had reports of high internal consistency, good ability to differentiate between pain subgroups, and moderate divergence with pain intensity (VAS). No contact could be made with the developer, thus this instrument was excluded from consideration.

The BPI_I is a 7-item derivative of BPI_long form (BPI_LF), which is considered in the next section.74 The BPI_I measures interference in general activity, sleep, mood, and relationships. It can be quickly self- or interviewer-administered and is validated in other languages. Its wording may challenge patients of low-literacy. It has high internal consistency and moderate discriminant validity. The BPI_I has been modified into a 12-item instrument, adding items relevant to disability (self care, recreation, social activities, finding out information and communication).75 The BPI suite requires registration prior to use.

Impact on others

Two instruments assessed the influence of pain, and people close to the patient. One instrument assessed the impact of the patient’s pain on others (Family Impact of Pain Scale [FIPS]), and the other assessed the impact of the spouse (‘significant other’) on a patient’s pain responses (Spouse Response Inventory [SRI]).

The FIPS is a 10-item instrument measuring the extent to which family activities and interactions are affected by the patient’s persistent pain.76 It has two domains showing moderate test–retest and internal consistency. It is sensitive in identifying patients whose behavior significantly impacts on family members. It moderately correlates with the VAS, the BDI, and the CSQ.

The SRI assesses the extent to which spouse responses contribute to a patient’s pain and disability.77 It has four domains (solicitous and negative spouse response pain behaviors, and facilitating and negative spouse response well behaviors). It has moderate intra-rater reliability and poor to moderate construct validity with several other instruments (eg, PBC, VAS, BDI). The SRI requires registration with the author prior to use.

Functional performance

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) is a patient-centered measure of performance of activities and tasks of daily living.78–82 It is a semi-structured interview in which patients identify and rate areas of difficulty in occupational performance. It is a broad-ranging comprehensive instrument with strong evidence of construct and content validity, reliability in administration, test–retest, and correlation with other performance measures. It is a commercial product designed to be used by registered occupational therapists.

Table 5 reports the Ready Reckoner for the functional pain assessment instruments, highlighting their variable psychometric properties and clinical utility.

Table 5.

Ready Reckoner for the short-listed functional persistent pain assessment measures

| BPI_I | COPM | FACS | FIPS | OccRQ | PDI | PGPQ | PSFS | RADL | SRI | WLQ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validity | Face | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Content | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Construct | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Comparison | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Sensitivity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | |||||

| Reliability | Inter-tester | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Intra-tester | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Internal | ||||||||||||

| Consistency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Simple instructions, short, simply worded items | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| <20 items | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| • Number of items | 7 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 22 | 3 | 12 | 39 | 25 | ||

| Able to be scored manually | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| <15 minutes administration time | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| • Estimated average time to administer | 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 15 | 5 | 7 | 20 | 15 | ||

| Norms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NA | NA | ✓ | ||||||

| Cut off scores | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NA | NA | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Specific to NZ | ||||||||||||

| No cost | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| No registration/limitations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Total ✓ | 8 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 5 | 10 |

Abbreviations: BPI_I, Brief Pain Inventory-Interference; COPM, Canadian Occupational Performance Measure; FACS, Functional Abilities Confidence Scale; FIPS, Family Impact of Pain Scale; OccRQ, Occupational Role Questionnaire; PDI, Pain Distress Inventory; PGPQ, Patient Goal Priority Questionnaire; PSFS, Patient-Specific Functional Scale; RADL, Resumption of Activities of Daily Living Scale; SRI, Spouse Response Inventory; WLQ, Work Limitations-Questionnaire.

Category 4: Multidimensional pain assessment instruments

Exclusions

Two instruments were excluded on grounds of redundancy. The Dartmouth Pain Questionnaire (DPQ) is a five-domain instrument adjunctive to the MPQ. It assesses the impact of pain on function.83 Other instruments measure this construct more comprehensively (eg, BPI). The BPI (32 items) and BPI_SF (15 items) are multidimensional psychometrically-sound measures of persistent pain features including pain severity, impact of pain on daily function, location of pain, pain medications and amount of pain relief in the past 24 hours or past week.74 The BPI has been validated in several languages. There is significant overlap between BPI and BPI_SF items, and therefore the BPI_SF was short-listed. The BPI suite is free to use after registration.

The Work Disability Diagnosis Interview (WDDI) was excluded on the basis of complexity and administration time. It includes several standard assessment instruments, a physical examination and an interview.84 Its estimated completion time exceeds three hours, constraining its utility in most clinical settings. This instrument however offers a comprehensive approach to persistent pain assessment, and may be useful in multidimensional multidisciplinary specialized assessment settings.

Retained instruments

The Obstacles to Return-to-work Questionnaire (ObsRWQ) measures prognosis for return to work, pain intensity and depression.85 It is moderately sensitive and specific around a cut-point of 150. Part I assesses depression and pain intensity; Part II assesses six domains of difficulties at work return, physical workload and harmfulness, social support at work, worry due to sick leave, work satisfaction, and family situation and support; and Part III is a single scale dealing with perceived prognosis of work return. The items in Part I and some of the items in Part III are taken from the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire (ÖMPSQ). This instrument correlates moderately with BDI.

The ÖMPSQ, if applied 4–12 weeks after injury, identifies the likelihood that workers with soft tissue injury will develop long-term disability.86 This provides an early opportunity to intervene to reduce the risk of long term disability in injured workers. Specific to low back pain, the instrument has been tested in several settings, providing thresholds for predicting risk of long-term disability with moderate evidence of validity.87–90

The West Haven–Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI) is a two-instrument suite (patient and ‘significant other’ versions). The patient version has 52 items in 12 domains divided into three parts, evaluating perceived interference of pain in occupational, social and family functioning; perceptions of responses of others to the patient’s pain, and participation in common daily activities.91 There are extensive norms, and strong psychometric properties. The ‘significant other’ version (WHYMPI_S) evaluates the influence of the patients’ pain on the partner/spouse, and partner influence on the patient.92 The WHYMPI requires registration prior to use.

Table 6 provides the Ready Reckoner for multidimensional pain assessment instruments. The generally high scores for these instruments indicate their value for health practitioners, in using one instrument to assess a number of constructs related to persistent pain.

Table 6.

Ready Reckoner for the short-listed multidimensional persistent pain assessment measures

| BPI_SF* | GPQ | OccRQ | ÖMPSQ | WHYMPI | WHYMPI_S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validity | Face | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Content | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Construct | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Comparison | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Sensitivity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Factors | 2 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Reliability | Inter-tester | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Intra-tester | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Test–retest | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Internal | ✓ | ||||||

| Consistency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Simple instructions, short, simply worded items | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| <20 items | ✓ | ||||||

| • Number of items | 15 | 24 | 55 | 56 | 52 | 52 | |

| Able to be scored manually | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| <15 minutes administration time | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| • Estimated average time to administer | 10 | 12 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Norms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Cut off scores | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Specific to NZ | ✓ | ||||||

| No cost | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| No registration/limitations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Total ✓ | 14 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 13 |

Abbreviations: BPI_SF, Brief Pain Inventory; GPQ, Glasgow Pain Questionnaire; OccRQ, Occupational Role Questionnaire; ÖMPSQ, Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire; WHYMPI, WHYMPI_S, West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory.

Category 5: Quality of life/general health assessment instruments

A number of instruments were identified in this category, with different purposes in persistent pain assessment.

Exclusions

The EuroQol (EQ-5D), World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL; WHOQOL-Bref) and Quality of Well Being Scale (QWBS) instruments were developed specifically for population-health research and clinical trials.93–95 They were not intended for clinical application, and were thus excluded from further consideration.

The remaining instruments are all commercial, and could be used for clinical assessments. Prior to the development of the SF-36, the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) was the best available quality-of-life measure.96 It assesses sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior and communication. These domains can be aggregated into broader physical and psychosocial domains. As it has now largely been superseded by the SF-36, the SIP was excluded from consideration. The Health Status Questionnaire (HSQ 2.0) contains the same items and domains as the SF-36, relevant to persistent pain.97 Given the lack of normative data, and overlap with the SF-36, the HSQ was also excluded from further consideration.

Retained instruments

The SF-36 contains eight domains (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, social functioning, mental health, role limitations due to emotional problems, vitality, and overall/general health).98 International population and health condition norms are reported.99 Given its normative data, the large number of publications which report use of the SF-36, and its wide use in clinical and research environments, it was short-listed.

The Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) measures pain intensity, and impact of pain on general life areas.100 It has strong evidence of reliability, validity, sensitivity to change and domain construction (physical activities, pain, sleep, social isolation, emotional reactions, energy level, and whether their present level of health affects their life in occupation, personal relationships, hobbies etc). In a publication which compared the NHP and SF-36 for patients with lower limb ischaemia,101 the NHP was more sensitive in discriminating between ischemia levels. This highlights the importance of considering the sensitivity of any instrument for patients with different types of persistent pain.

Table 7 provides the Ready Reckoner scores for the general health/quality of life assessment instruments.

Table 7.

Ready Reckoner for the short-listed general health/quality of life persistent pain assessment measures

| NHP | SF-36 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Validity | Face | ✓ | ✓ |

| Content | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Construct | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Comparison | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Sensitivity | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Factors | 5 | 9 | |

| Reliability | Inter-tester | ✓ | ✓ |

| Intra-tester | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Test–retest | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Internal | |||

| Consistency | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Simple instructions, short, simply worded items | ✓ | ✓ | |

| <20 items | |||

| Number of items | 38 | 36 | |

| Able to be scored manually | |||

| <15 minutes administration time | ✓ | ||

| Estimated average time to administer | 10 | 20 | |

| Norms | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Cut off scores | |||

| Specific to NZ | ✓ | ||

| No cost | |||

| No registration/limitations | |||

| Total score | 12 | 12 |

Abbreviations: NHP, Nothngham Health Profile; SF-36, Short Form Health Survey-36.

Discussion

This review identified many assessment instruments published over the past 20 years, dealing with many constructs related to persistent pain presentations and behaviors. Only a few instruments were specific to single health disciplines, or single persistent pain constructs. The publication of assessment instruments appears to mirror developments in under-standing persistent pain behaviors and presentations, in terms of neuroanatomy, biology, physiology, psychology, and social science.5–14 However, no one instrument currently appears to assess all features of persistent pain, and thus multiple instruments are required to provide a comprehensive description of an individual with persistent pain. This is perhaps not surprising, as given the variability in etiology, location and nature of persistent pain presentations, and the variable individual time taken for such pain to develop, it would be a challenge to develop one instrument which addressed all aspects of persistent pain for all patients.6–10 Given the time required to administer even the shortest instrument in every assessment category identified in this review, this could be daunting and burdensome for patients and health providers. Thus, health practitioners using persistent pain assessment instruments for the first time would be advised to start with a multidimensional instrument which provides an overview of the patient. Once core areas of concern have been identified, more specific assessment instruments could be used.

There was considerable overlap in item intent and wording within- and between-persistent pain assessment categories in the short-listed instruments. It appears that instruments measuring similar constructs have been developed by different research groups with apparently little reflection on already published instruments. Choosing between similarly worded and constructed instruments with similar purposes, and similar psychometric properties, thus provides a challenge for health practitioners. The review ighlighted how some instruments changed over time, with little explanation of wording change, change in item order, or addition or removal of items. This suggests an opportunity for international research groups to collaborate on collating, critically appraising and then distilling essential items from key instruments, in order to develop a comprehensive battery of assessment questions which would address all aspects of persistent pain presentation.

The generalizability of many instruments was constrained by the size of study samples, and/or the specific nature of populations on which instruments were tested. This reduced the usefulness of many instrument’s population norms, or cut-points, and raised concerns that if these were inappropriately applied, patients may be inaccurately classified regarding persistent pain behaviors. This highlights the need for instrument developers to research their instrument’s performance in different patient subgroups, with different demographic characteristics and health conditions. This review also flagged the importance of improved understanding of the social and cultural implications of describing pain experiences, to test the stability and generalizability of persistent pain descriptors across population groups and settings.

There was little consistency in choices of statistics tests for psychometric properties, or ways in which psychometric properties were reported. This meant that, despite the volume of published research in this area, little information was presented in useful terms to encourage clinical uptake of any persistent pain assessment instrument. Thus for many health practitioners, the wealth and variability of published material on persistent pain assessment may be overwhelming with respect to instrument choice. For instance, there was little convincing evidence to support the use of many long versus short/revised instruments, in terms of psychometric properties. Choice would appear to be based on personal preference, and/or clinical imperatives. This finding highlights the need for developers of new instruments to justify item intent, number, and wording, and to provide evidence of psychometric properties to convince users that their instrument provides the most useful assessment information in specific circumstances.

Fewer than 25% of instruments initially identified in the literature search were short-listed. The short-listing process relied on the quality of background literature reporting. Had more detail been available on psychometric properties or clinical utility, other instruments may have been short-listed. Some instruments, whilst appearing promising, reported psychometric properties in unpublished conference proceedings or research theses. As these were often not available via library databases, the instrument was excluded in line with the review criteria. Some instruments showed promise on initial test results published in one or two research papers, however there was little subsequent research to support its use. On the other hand, some instruments with less robust psychometric properties were regularly reported as research tools, and would be thus more familiar to health practitioners. Most instrument developers could be contacted, and many willingly provided additional (although often unpublished) details on their instrument’s performance.

The Ready Reckoner, although unvalidated, provided a comprehensive way of collating key information on psychometric properties and clinical utility for efficient clinical decision-making. It highlighted that many instruments did not have good clinical utility despite having sound psychometric properties. Clinical utility could be constrained by lengthy or unwieldy questions, complex wording, or multiple intentions in one question. Administration time for such instruments often precluded their ready clinical use. This review sought to identify instruments relevant to primary health care settings. These were generally short, efficient to deliver and score and sensitive to persistent pain problems. A resource of high quality instruments for primary care providers should increase the frequency with which persistent pain patients are identified early.

The importance of considering the patient in an holistic manner was supported not only by the different categories of persistent pain assessment, but also by the availability of assessment instruments for ‘significant others’. These instruments recognize that patients with persistent pain rarely exist in isolation, and that their pain behaviors have an effect on, and are influenced by, the behaviors of people around them.

Conclusion

Early identification of patients at-risk of developing persistent pain is essential to ensure appropriate and timely intervention, and reduce avoidable individual, social, community and work-related costs. No one assessment instrument captured all the constructs of persistent pain. While the compendium focuses clinicians’ choices on high quality, clinically useful instruments, clinicians should use multiple instruments to ensure comprehensive assessment of adults with persistent pain.

The compendium is available from New Zealand Accident Compensation Corporation. Health practitioners who have not, to date, used standard assessment instruments for persistent pain patients are encouraged to choose instruments from those provided in the compendium.

Appendix 1

Search strategy

The search strategy incorporated all possible variations of nomenclature relating to persistent pain assessment. The search sought to identify:

all questionnaires, surveys, instruments and rating scales developed to assess persistent pain in adults who had noncancer pain, and

developmental literature including psychometric testing of these instruments.

Concurrently, background literature was sought on:

biomedical, functional, behavioral, and psychosocial aspects relevant to persistent pain assessment

risk factors for developing persistent (noncancer) pain

special populations (indigenous, rural, and remote) and instruments specifically developed to address their needs, and

different methods of administration of assessment instruments (in person, via telephone or mail).

Search terms

MeSH subject headings: pain measurement, persistent pain, questionnaires, indigenous population

Non-MeSH search terms: tool*, scale*, inventor*, questionnaire*, protocol*, survey*, profile*, model*, drawing*, checklist*, index, pain, pain assessment, persist*, functional, biomedical, psychosocial, psycholog*, behaviour*, behavior*, risk, assess*, screen*, rural, indigenous, maori, postal, telephone, psychometric, valid, reliab*, respons*. The search terms and strategies were amended as required for other databases.

Library databases and internet sites

All available databases were accessed through university library sources. The ‘parent’ data bases sourced mainstream academic databases which list the peer reviewed literature, including OVID (AMED, CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE) and INFORMIT (AUSThealth, INFORMIT Plus Text [Meditext], INFORMIT e-library). These principal databases were interrogated first and publications sourced from these databases contributed more than 95% of the literature reviewed. To ensure rigor in searching of literature, other secondary databases to validate the initial findings were then searched, including, but not limited to, PsychINFO, PsycARTICLES, Science Direct, Web of Science, PubMed, etc. Interrogation of these databases revealed mostly redundant duplicate publications, already identified from the larger databases.

Appendix 2

Persistent pain severity

| Unidimensional measure of pain severity | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) [10 cm line] (reported,22 discriminant values102 Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) [word descriptors]15 Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) [0–10 categories]15 |

| Multidimensional pain assessment instruments | Chronic Pain Grade (CPG)17 McGill Pain Questionnaire Long form (MPQ_LF)22 McGill Pain Questionnaire Short form (MPQ_SF)23 Neuropathic Pain Scale (NPS)103 Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI)104 |

| Discriminating neuropathic and nonneuropathic pain | Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4)25 IDPain105 Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS)27 (PHC) Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire Long Form (NPQ_LF)106 Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire Short Form (NPQ_SF)106 |

Psychological assessment of chronic pain

| Psychological states not directly related to persistent pain | Depression, Anxiety, and Positive Outlook (DAPOS)107 |

| Measurement of anxiety, depression, and mood | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)108 (peer reviewer) |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D)36 | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)109 (ACC Pain Focus Group) | |

| Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10)34 | |

| Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (ZSRD)110 | |

| Physiological manifestations of anxiety and depression relative to persistent pain | Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire (MSPQ)41 |

| Pain cognition | Cognitive Coping Strategies Inventory-Revised (CCSI-R)111 |

| Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS-SF(20), PASS-40, PASS-72)112 | |

| Pain Cognition List (PCL)113 | |

| Pain Cognitions Questionnaire (PCQ)114 | |

| Catastrophizing, negative thoughts, fear | Negative thoughts about pain |

| Inventory of Negative Thoughts in Response to Pain (INTRP)115 | |

| Catastrophizing | |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) (includes a scale for the significant other/partner PCS_S)116 | |

| Persistent pain fear | |

| 1. Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ)43 | |

| 2. Fear Avoidance of Pain Scale (FAPS)117 | |

| 3. Fear of Pain Comparisons (FPC_11)118 | |

| 4. Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK)119 | |

| 5. Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia Short version (TSK-11)45 | |

| Pain distress | |

| Pain Distress Inventory (PDI)46 | |

| Vigilance, preoccupation, and awareness of pain | |

| Pain Vigilance and Awareness Questionnaire (PVAQ)120 | |

| Psychopathology in persistent pain | |

| Symptoms of Chronic Pain List (SCL_27)121 | |

| Risk factor identification | Distress and Risk Assessment Method (DRAM)122 |

| Pain function, coping & management | Ability to function with persistent pain |

| Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale (PAIRS)123 | |

| Persistent pain coping | |

| 1. Chronic Pain Coping Inventory suite (CPCI_65 (CPCI_significant other, CPCI_42, and CPCI_abbreviated)52 | |

| 2. Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ_50)124 which also includes a revised (CSQ_R(27)), a shorter version (CSQ24)56 (and an abbreviated version (CSQ_abbreviated)54 | |

| 3. Stoicism (Pain Attitudes Questionnaire-Revised (PAQ-R)) 125 Pain-Coping Inventory (PCI)57 | |

| 4. Pain Coping Style Inventory (PCSI)126 | |

| 5. Vanderbilt Multidimensional Pain Management Inventory (VMDPMI)127 | |

| Acceptance of persistent pain | |

| Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (CPAQ)128 | |

| Persistent pain management beliefs | |

| Cognitive Risk Profile for Pain (CRPP)60 | |

| Reactions to persistent pain | |

| 1. Brief Pain Coping Inventory (BPCI)129 | |

| 2. Biobehavioral Pain Profile (BPP)61 | |

| Pain attitudes | |

| Survey of Pain Attitudes (SOPA_57),130 which includes a 35 item version (SOPA_35) and a short version (SOPA_S) | |

| Pain beliefs and consequences | |

| Pain Beliefs Questionnaire (PBQ)131 | |

| Pain beliefs and knowledge | |

| Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory (PBPI)132 | |

| Psychological pain functioning | |

| 1. Multidimensional Locus of Pain Control Questionnaire (MLPC)133 | |

| 2. Pain Solutions Questionnaire (PaSolQ)134 | |

| 3. Pain Patient Profile (PPP)135 | |

| Behavioral change readiness | Chronic pain self-efficacy scale (CPS-ES)136 |

| Chronic Pain Values Inventory (CPVI)49 | |

| Multidimensional Pain Readiness to Change Questionnaire (MPRCQ)50 | |

| Pain Behavior Checklist (PBC)137 | |

| Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire (PSCQ)138 | |

| Pain Self Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ)139 |

Eighteen instrument suites (25 instruments) were identified, these being BDI, BPP, CES-D, CPAQ, CPCI suite of four instruments, CPVI, CRPP, CSQ suite of four instruments, FABQ, HADS, K10, MPRCQ, MSPQ, PBC, PCI, PSEQ, TSK suite of 2 instruments, ZSRD.

Functional capacity

| Occupation focus | Work Limitations Questionnaire suite (WLQ)62 |

| Work Limitations-26 (WL-26)140 | |

| Occupational Role Questionnaire (OccRQ)64 | |

| Risk Factor Questionnaire (RFQ)141 | |

| General function (women only) | Inventory of Functional Status – chronic pain (IFS-CP)142 |

| General function | Functional Abilities Confidence Scale (FACS)65 |

| Resumption of Activities of Daily Living Scale (RADL)66 | |

| General function (Indigenous health) | Kempsey Survey of Muscle, Joint and Bone Conditions (KSMBJC)143 |

| Interference (disability) in functional activities | Brief Pain Inventory-Interference (BPI_I)144 (7-item derivative of BPI_LF,74 developed into a 12-item instrument75 for disabled persons) |

| Functional Assessment Screening Questionnaire (FASQ)73 | |

| Functional Interference Estimate (FIE)145 | |

| Pain Disability Index (PDI)146 | |

| Pain Disability Questionnaire (PDQ)147 | |

| Impact on others | Family Impact of Pain Scale (FIPS)76 |

| Spouse Response Inventory (SRI)148 | |

| Patient-specific instruments | Patient Goal Priority Questionnaire (PGPQ)69 |

| Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS)70 | |

| Performance | Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)78 |

Multidimensional assessment of persistent pain

| Occupational issues | Obstacles to Return-to-Work Questionnaire (ObsRWQ)85 |

| Expectations | Patient Centered Outcomes Questionnaire (PCOQ)149 |

| Medical Rehabilitation Follow Along measure (MRFA) – Musculoskeletal form150 | |

| Yellow flags | Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire (ÖMPSQ). This uses exactly the same wording as the Acute Low Back Screening Questionnaire (Yellow Flgs) already in use by ACC in the Acute Low Back Pain guidelines.151 |

| The ÖMPSQ includes a wide range of body parts likely to be affected by musculoskeletal pain. | |

| Obstacles to Return-to-Work Questionnaire (ObsRWQ) (listed above)85 contains items relating to depression | |

| Pain dimensions | Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)144 (original (also known as the long form)) |

| Brief Pain Inventory (BPI-SF)144 (short form) | |

| Glasgow Pain Questionnaire (GPQ)152 | |

| Health Background Questionnaire for Pain (HBQP)153 | |

| Hunter Integrated Pain Service (HIPS) Patient Screening Questionnaire (HIPSPSQ) (no published reference)154 | |

| Obstacles to Return-to-Work Questionnaire (ObsRWQ)85 (listed above and reporting pain experiences). | |

| Pain Outcomes Questionnaire suite of six instruments (POQ) Intake and Pain Outcomes Questionnaire-Short Form (POQ-42, POQ-SF, POQ-DC-28 [discharged from acute care], POQ-FU-34 [at follow-up], POQ-DC-5 [satisfaction scale extracted from POQ-DC-28])155 | |

| West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI)91 including the WHYMPI_S (Significant Other Instrument) | |

| Prediction of future disability (LBP only) | Vermont Disability Prediction Questionnaire (VDPQ)156 |

| Pain profiling and outcome prediction instruments | Profile of Chronic Pain: Screen (PCP:S)157 |

| Profile of Chronic Pain: Extended Assessment Battery (PCP:ES)158 | |

| Pain Outcomes Profile (POP)155 | |

| Compilation or adaptation of existing instruments | Dartmouth Pain Questionnaire (DPQ) (enhancing items from McGill Pain Questionnaire [MPQ])83 |

| Work Disability Diagnosis Interview (WDDI)84 involves interview which consists partly of questions compiled by instrument authors and partly of a range of standardised questionnaires such as the Oswestry Disability Index, Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire and Work APGAR. |

General health/Quality of life assessment

| EuroQol (EQ-5D)93 |

| Health Status Questionnaire 2.0 (HSQ)159 |

| Nottingham Health Profile (NHP)160 |

| Quality of Well-Being Scale – Self-Administered (QWBS)95 |

| World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL)94 (including a short form WHOQOL-Bref) |

| Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF36)98 |

| Sickness Impact Profile (SIP)96 |

Appendix 3

Excluded instruments

Persistent pain severity

Lack of published literature

At the time of the review, there was no published literature on psychometric properties of the instrument IDPain, and this instrument was excluded from further consideration.

Contact with author

Despite repeated attempts, no contact was able to be made with the author of the NPS (Galer) and thus this instrument was excluded after psychometric property evaluation.

Primary function

The NPSI is mainly reported in the literature as an outcome measure, not an assessment instrument, and it was thus excluded from further consideration.

Psychological assessment of persistent pain

Twenty-six instrument suites (31 instruments) were excluded during Step 2. The instruments, and primary reasons for exclusion, are listed below.

Brief Pain Coping Inventory (BPCI) no information on administration or scoring

Cognitive Coping Strategies Inventory-Revised (CCSI-R) no psychometric properties

Chronic Pain Self-Efficacy Scale (CPS-ES) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Depression, Anxiety and Positive Outlook (DAPOS) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Distress and Risk Assessment Method (DRAM) replicates questions in MSPQ and Zung instruments, minimum psychometric properties

Fear Avoidance of Pain Scale (FAPS) No information on psychometric properties

Fear of Pain Comparisons (FPC) uncertain clinical utility161. Found it was less useful than the PASS and FABQ for understanding chronic pain

Inventory of Negative Thoughts in Response to Pain (INTRP) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Multidimensional Locus of Pain Control Questionnaire (MLPC) authors stated that further work is required on the instrument’s psychometric properties, particularly aspects of validity. The PSCQ covers this area better.

Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale (PAIRS) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Pain Attitudes Questionnaire-Revised (PAQ-R) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Pain Solutions Questionnaire (PaSolQ) validity untested in English language

Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS-20, PASS-40, PASS-72) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties, wordy instrument with multiple items in the long forms, uncertain psychometric properties in the short form

Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory (PBPI) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Pain Beliefs Questionnaire (PBQ) unable to trace authors, minimum evidence of psychometric properties

Pain Cognition List (PCL) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties, scoring instructions only available in Dutch

Pain Cognitions Questionnaire (PCQ) unable to trace the authors

Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Pain Coping Style Inventory (PCSI) uses AVAS for scoring all items, minimum psychometric properties, replicates other more readily scored instruments

Pain Distress Inventory (PDI) could not contact developers

Pain Patient Profile (PPP) limited information on psychometric testing

Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire (PSCQ) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Pain Vigilance and Awareness Questionnaire (PVAQ) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Symptoms of Chronic Pain List (SCL_27) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Survey of Pain Attitudes (SOPA) (including SOPA_35, SOPA_57, SOPA_short) limited evidence of strong psychometric properties

Vanderbilt Multidimensional Pain Management Inventory (VMDPMI) limited access to background documentation, limited evidence of psychometric properties, overlaps with other better credentialed instruments

Functional assessment of persistent pain

The excluded instruments during Step 2 comprised FIE, IFS_CP, KSMBJC, PDQ, RFQ (all for poor evidence of psychometric testing).

Multidimensional assessment of persistent pain