Abstract

Behavior analysts are obligated by the conventions of the academic discipline and guidelines of professional conduct to stay in close contact with the scholarly literature. However, a number of variables can interfere with this obligation. We discuss several barriers to searching the literature, accessing journal content, and making contact with the contemporary literature and provide solutions for eliminating them.

Keywords: evidence-based practice, information literacy

Aubiquitous notion in applied behavior analysis is that practitioners should base their professional activities on the research literature. For example, the Guidelines for Responsible Conduct of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board® (BACB, 2010a) states that behavior analysts must base professional decisions on the scholarly literature (1.01–Reliance on Scientific Knowledge; 2.10–Treatment Efficacy) and maintain competence by making contact with the scholarly literature (1.03–Professional Development). Furthermore, the Association for Behavior Analysis International's (ABAI) position statements on the right to effective behavioral treatment (Van Houten et al., 1988) and the right to effective education (Barrett et al., 1991) assert that individuals who receive therapeutic and educational services are entitled to programs that are based on empirical evidence.

We assume that most practitioners acquire repertoires for critically consuming the scholarly literature during graduate school. This assumption is indirectly supported by the discipline's certification and accreditation requirements. For instance, the BACB requires applicants for the Board Certified Behavior Analyst exam to have successfully completed graduate coursework in experimental evaluation and measurement (BACB, 2010b). Similarly, current ABAI guidelines for the accreditation of graduate programs require a course in within-subjects research methodology (ABAI, 2010). It is particularly easy to access the literature while enrolled in a graduate program. For example, graduate students are routinely assigned numerous readings pertinent to their discipline and being a university student comes with access to searchable databases and journal content through the library. In addition, some graduate students may be exposed to verbal communities that further shape their ability to access and critically consume the literature. Unfortunately, graduation all too often means the end of these mechanisms and, thus, contact with the literature may become considerably more effortful. The purpose of this article is to illustrate strategies and tactics practitioners can use to search literature databases, access and read journal content, and potentially increase the likelihood of meeting their obligation to maintain a current and evidence-based practice repertoire. We should note that the following recommendations are based on the assumption that the practitioner has acquired a repertoire for critically evaluating the literature after making contact with it.

Searching the Literature

One of the most important repertoires for making contact with the discipline's scholarly work is searching the literature for writings relevant to an immediate practice or research need. A number of barriers impact the ease with which practitioners can search the literature or affect the success of the searches.

Barriers

Some journals (e.g., Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis; JABA) include searchable databases on their web sites that permit users to conduct keyword searches of prior issues. Through such databases, users can locate abstracts of articles and, in some cases, electronic versions of the articles themselves. However, searching journal databases is an inefficient way of accessing the published literature because each journal's database must be searched. As a result of this high effort, we suspect that many individuals who only use this strategy limit their searches to one or two journals and potentially miss relevant research published elsewhere.

The second readily available mechanism for searching the literature is an Internet search engine, such as Google or Yahoo. Such broad search engines might reduce the effort associated with searching multiple journal databases and allow the user to locate articles and books from multiple disciplines. Unfortunately, search engines are likely to produce many “false positive” hits, including sites that are nonacademic in nature (e.g., a treatment clinic) and writings that are not peer reviewed (Piotrowski, 2007). In addition, the effort associated with filtering large and diverse search results might be prohibitive for some. Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com) mitigates some of the concerns with general search engines by restricting its search to scholarly work. However, it does not limit content to the behavioral sciences, often includes nonpeer-reviewed content (e.g., workshop materials, technical reports) in its results, and has somewhat limited search parameters.

A more exhaustive, better controlled, and potentially more efficient method for searching the broad scholarly literature is the PsycINFO database. PsycINFO, published by the American Psychological Association (APA), is the primary database of the psychological and behavioral sciences. The PsycINFO database includes the vast majority of scholarly journals (currently more than 2,450), books, book chapters, and dissertations published in psychology and related areas such as education and medicine as far back as the 1800s for some journals (APA, 2010). With effective search strategies, PsycINFO contains a wealth of information that can be obtained to assist practitioners in obtaining evidence relevant to their practice. Although virtually every graduate student has access to PsycINFO through his or her university library, this low-effort and free access is typically lost after graduation, resulting in a substantial barrier to searching the literature.

Solutions

Although individual subscriptions to PsycINFO are available, they are somewhat expensive. For APA members, full access (the GOLD package) to PsycINFO costs $149 per year. PsycINFO is available to nonmembers through the PsycNET database package, which also includes electronic access to journals and books published by the APA. The cost of PsycNET is $500 per year. An alternative to the individual subscription would be to convince an employer to purchase an organizational subscription. This is an especially relevant option for organizations that employ multiple behavior analysts and who have a commitment to evidence-based practice. It is possible that such an organizational subscription could be negotiated as part of an initial offer of hire. An organizational subscription to PsycINFO costs $1,700 per year and provides access for up to 49 users. A third option for obtaining access to PsycINFO is through the library of the practitioner's alma mater. Although the APA does not permit universities to provide online PsycINFO access as part of their alumni association memberships (which often include library access), if one happened to work near his or her alma mater such a membership should allow on-site access to the library and, thus, PsycINFO and journal content. Alumni association memberships generally cost about $50 per year. Finally, practitioners who hold adjunct appointments teaching courses or providing practicum supervision for a college or university would likely have online and local access to library resources.

We acknowledge that our recommended solution to barriers associated with searching the literature—a subscription to PsycINFO—comes with its own financial barriers. However, these costs might be minimized for the individual by arranging for an organizational subscription or an alumni-association membership, or, in the United States, by declaring the expense as a Schedule C deductible on his or her annual federal tax return.

Accessing Journal Content

There are likely a number of journals relevant to a practitioner's scope of practice. As an illustration, Table 1 includes a sample journal list for a behavior analyst working in the area of developmental disabilities. These journals span the academic domains of applied behavior analysis (ABA; e.g., Behavior Analysis in Practice, JABA), developmental disabilities (e.g., Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders), and the ABA subspecialty, organizational behavior management (e.g., Journal of Organizational Behavior Management). Although a given practitioner might not regularly follow all of these journals, all of them would likely contain articles that are relevant to the practitioner on at least an occasional basis.

Table 1.

A sample journal list illustrating titles relevant to the practice of applied behavior analysis in developmental disabilities

| Journals | # of Issues per Year | Individual Subscription Cost | Indexed in PsycINFO | Searchable Web Site | In Press Articles Online | Articles Freely Available Online | TOC E-mail Alerts | RSS Feed Available |

| American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (formerly American Journal on Mental Retardation) | 6 | Free ^ | ||||||

| The Analysis of Verbal Behavior | 1 | $45 |

|

|||||

| Behavior Analysis in Practice | 2 | $46 |

|

|||||

| The Behavior Analyst | 2 | $64♦ |

|

|||||

| The Behavior Analyst Today | 4 | Free+ | ||||||

| Behavior Modification | 6 | $150 | ||||||

| Behavioral Interventions | 4 | $248 | ||||||

| Child and Family Behavior Therapy | 4 | $113 | ||||||

| Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities | 4 | $40 | ||||||

| Education and Treatment of Children | 4 | $45 | ||||||

| Exceptional Children | 4 | $86 | ||||||

| Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities | 4 | $59 | ||||||

| Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis | 4 | $32 |

|

|||||

| Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders | 12 | $226 | ||||||

| Journal of Behavior Assessment and Intervention in Children (formerly Journal of Early Intensive Behavior Intervention) | 4 | Free+ | ||||||

| Journal of Behavioral Education | 4 | $508 | ||||||

| Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities | 6 | $878 | ||||||

| Journal of Organizational Behavior Management | 4 | $124 | ||||||

| Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions | 4 | $59 | ||||||

| Journal of Precision Teaching & Celeration | 2 | Free▴ | ||||||

| Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Applied Behavior Analysis | 4 | Free+ | ||||||

| The Psychological Record | 4 | $50 | ||||||

| Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders | 4 | $56 | ||||||

| Research in Developmental Disabilities | 6 | $149 |

^with American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Membership ($150)

♦ free with Association for Behavior Analysis International Membership

+ online only

▴ with Standard Celeration Society Membership ($100)

*all issues except for the two most recent years available at www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov

Barriers

Assuming an individual has an effective search repertoire and the ability to access searchable databases such as PsycINFO, there still exists an additional barrier to accessing journal articles after their titles and/or abstracts have been obtained. Unless a practitioner has an affiliation with a university library, he or she might not have reliable access to journals and, thus, would be unable to locate desired articles. Although journals can be obtained through individual subscriptions, the number of journals that might need to be followed and the expense of some of them would likely be prohibitive. As an illustration, annual subscriptions to Child and Family Behavior Therapy and Journal of Behavioral Education are $113 and $508, respectively.

Solutions

We recommend the practitioner compile a list of relevant journals to follow on a routine basis. We also recommend some practitioners consult with senior practitioners (perhaps their clinical supervisors) or established researchers in their area because they might not be aware of all of the journals that are directly and indirectly related to their work. The journals listed in Table 1 might be a good starting point for some practitioners (see also Carr & Stewart, 2005). It is possible that some of a practitioner's target journals are inexpensive or even free. For example, three journals in Table 1 are available online free of charge (The Behavior Analyst Today, Journal of Behavior Assessment and Intervention in Children, Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Applied Behavior Analysis). In addition, other journals are available for quite modest subscription rates. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis is relatively inexpensive ($32 per year), primarily because it is published by an academic society whose sole mission is to disseminate behavioral science rather than by a profit-seeking entity. Similarly, The Analysis of Verbal Behavior ($45 per year), Behavior Analysis in Practice ($46 per year), and The Behavior Analyst ($64) are also relatively inexpensive because they are published by the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI). Currently, ABAI members receive a subscription to The Behavior Analyst as part of their annual membership.

In addition to subscribing to journals that are relatively inexpensive and following freely available online journals, there are at least four other ways to access journal content. First, practitioners can access archived back issues of JABA, The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, and The Behavior Analyst via PubMed Central (http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov) up to the two most recent years. Second, as mentioned earlier, some individuals might have on-site or online access to the library (including interlibrary loan services) of their alma mater through an alumni association membership. Third, practitioners can always contact authors who are usually quite willing to share reprints of their work via electronic or regular mail. E-mail addresses can generally be obtained from an article's PsycINFO record and journal web site record. Admittedly, this option should not constitute a practitioner's primary method of accessing journal content, but it is a useful one for articles that are especially important or difficult to locate. Finally, journal content can occasionally be accessed via Google Scholar. Google Scholar's coverage is quite exhaustive and some of its searches produce electronic versions of articles from various web sites (e.g., an author's web site).

Contacting the Contemporary Literature

In addition to securing access to searchable databases and journal content, practitioners need a method for making contact with the new literature that is published on an ongoing basis to ensure that their clinical repertoires are informed by the latest scientific developments.

Barriers

Contacting the contemporary literature can be a daunting task for at least three reasons. First, as mentioned earlier, there will likely be many journals that are relevant to a given practitioner's work. Deciding which ones to follow can be difficult, as one may not be aware of all of the journals or knowledgeable about related areas that should also be followed. In addition, behavioral studies are frequently published in nonbehavioral journals. For example, a recent and important replication of the seminal Lovaas (1987) outcome study of early and behavioral intervention for childhood autism was published in a journal devoted to research on intellectual disabilities—American Journal on Mental Retardation (now American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; Sallows & Graupner, 2005). Unless a practitioner in this area followed this particular journal, he or she would probably not make contact with this particular publication until being made aware of it by others.

A second barrier to making contact with the contemporary literature is the effort associated with following multiple journals. The vast number of journals that are available and the cumulative frequencies with which issues are published can make this a demanding task. For example, if one were to follow all of the journals depicted in Table 1, an average of two new journal issues would be published each week. Without a systematic method for making contact with such a volume of activity, we suspect that many practitioners would simply opt out of the process altogether.

The final, and perhaps most important, barrier to making contact with the contemporary literature is the absence of workplace contingencies that support such activity. We are aware of many practitioners who work in environments where competing workplace demands appear to displace efforts to routinely make contact with the literature. In such cases, unless the practitioner's supervisor or peers arrange contingencies for locating, reading, and critically consuming journal articles, we suspect there is a low probability that these activities will occur. Of course, it is possible that a practitioner's graduate-training program did a superb job training such skills, as well as programming for their maintenance and generalization. Unfortunately, we suspect that this scenario is probably more the exception than the rule.

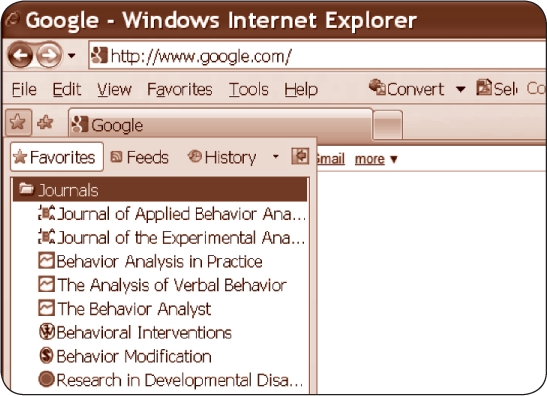

Solutions

We recommend four general methods for overcoming the aforementioned barriers so that contacting the contemporary literature is more manageable. First, we recommend that practitioners organize the bookmark panel on their web browser so that the effort for accessing key web sites is minimized (see Figure 1 for an example). A number of journal web sites make available electronically “in press” articles that have been accepted for publication but have not yet appeared in print. For example, 10 of the 24 journals listed in Table 1 make in-press articles available on their web sites. Routinely checking these web sites would allow the practitioner to access the contemporary literature before it is published. Although the number of in-press articles available on these pages varies, some journals include dozens of such articles prior to publication. Indeed, over 100 in-press articles are routinely available on the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities web site. Organizing bookmarks to the in-press pages of journal web sites would probably increase the likelihood of one checking these sites on a regular basis. In addition, links to PsycINFO and journal web sites that contain electronic versions of published articles could be similarly bookmarked to prompt regular traffic to those sites.

Figure 1.

An illustration of a web browser's bookmark panel organized to prompt regular contact with journal web sites.

Second, we recommend practitioners sign up for e-mail alerting services for their journals of interest. Many journal web sites freely offer a table of contents (TOC) alerting service (17 of the 24 journals in Table 1 offer such a service). After a user signs up for the service, every time an issue of the journal is published, its TOC is e-mailed to the user. When TOC e-mails are received, we recommend the practitioner review the issue's content for articles of potential interest. The reference information for these articles could then be copied and pasted to a Word file for subsequent review (e.g., every two weeks), at which point the article abstracts can be reviewed on the journal's web site. If after reviewing an abstract, the practitioner deems the article of further interest, it can be sought using the methods described in the Accessing Journal Content section.

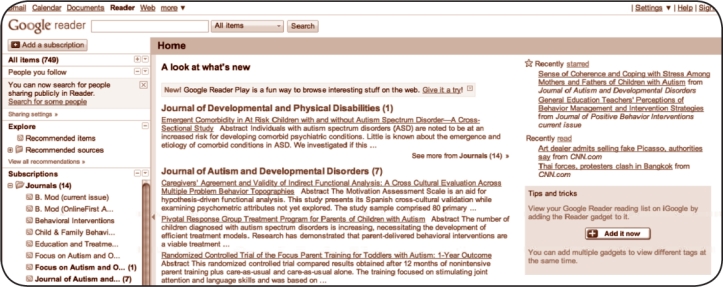

As an alternative or supplement to TOC alerting services, practitioners can use web-based aggregators (e.g., Google Reader) to be alerted when journal web pages are updated. Aggregators monitor a web page's Really Simple Syndication (RSS) feed for updated material and pull its content to the program for the user to review. Journals are increasingly making RSS feeds available (e.g., 11 of 24 journals in Table 1). This strategy reduces the time and effort needed to regularly check journal web sites for updated content (e.g., new issues or in-press articles). Using a program such as Google Reader, the user would first subscribe to the RSS web feed provided by the journal of interest. The aggregator would then organize and display recently released content (e.g., article title, author, and abstract) for the user to review at his or her convenience (see Figure 2 for an example). Google Reader also provides a link to the web site hosting the content and allows the user to “star” content as a prompt for subsequent viewing.

Figure 2.

An illustration of recently updated journal web pages on Google Reader.

Finally, we recommend that practitioners (and those who employ them) arrange contingencies in the work environment to more explicitly promote contact with the scholarly literature. For example, employees could routinely hold a “journal club” wherein all attendees would meet to discuss recently published articles germane to their practice. In addition, an agency could assign a supervisor to act as a “liaison” to the literature who would be responsible for gathering and disseminating scholarly information to other employees, perhaps during portions of regularly scheduled staff meetings or trainings. There are undoubtedly other tactics that could be employed toward similar ends. However, in order for such a “culture” to emerge, the attendant contingencies would need to be explicitly arranged, perhaps even being written into formal job descriptions. To the extent that the practitioner does not work in a social community willing to participate in such activities, or works alone, he or she might be able to employ self-management procedures such as goal setting, self-monitoring, and contingency contracts to increase the likelihood that regular contact with the contemporary literature is maintained.

Conclusion

There are likely multiple strategies for staying current on the relevant literature in one's area. It is important that the practitioner develops an explicit set of practices and arranges contingencies that enable sufficient access to the archived and contemporary literature with the least effort possible. We have found the strategies described in the present article personally effective and have heard similar evaluations from colleagues and students (see Table 2 for a summary of the strategies). It should be noted that some information provided in this article will undoubtedly change over time. Alerting services, URLs, costs, etc. are not likely to remain static for long. Furthermore, some of the specific tactics we recommend (e.g., checking web sites for in-press articles) might soon become outdated as technology changes. However, we suspect the general strategies that we recommend—(a) generating a core list of journals to follow, (b) securing access to journal content, and (c) developing a system and contingencies for making contact with the newly published literature—will be relevant for some time. We hope that practitioners are able to use these recommendations to make more frequent and reliable contact with the scholarly literature such that their practices and, ultimately, their consumers benefit from the latest and most relevant evidence available.

Table 2.

Some barriers and proposed solutions for searching, accessing, and contacting the research literature.

| Task | Barriers | Solutions |

| Accessing Journal Content |

|

|

| Contacting the Contemporary Literature |

|

|

Footnotes

The first author is affiliated with the Behavior Analyst Certification Board® (BACB®), which has not reviewed or approved the content of this article, nor does it endorse its content.

Action Editor: Jennifer L. Austin, Ph.D., BCBA

References

- American Psychological Association. PsycINFO®. 2010. Retrieved from www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/index.aspx.

- Association for Behavior Analysis International. Guidelines for the accreditation of graduate programs in behavior analysis. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.abainternational.org/BA/education/AP_11.asp.

- Barrett B. H, Beck R, Binder C, Cook D. A, Engelmann S, Greer R. D, Watkins C. L. The right to effective education. The Behavior Analyst. 1991;14:79–82. doi: 10.1007/BF03392556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. Behavior Analyst Certification Board ® guidelines for responsible conduct. 2010a. Retrieved from http://www.bacb.com/pages/conduct.html.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. Third edition task list contact hour requirement per content area. 2010b. Retrieved from http://www.bacb.com/pages/301webhourallocation.html.

- Carr J. E, Stewart K. K. Citation performance of behaviorally oriented journals. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2005;6:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lovaas O. I. Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young autistic children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:3–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski C. Sources of scholarly and professional literature in psychology and management. The Psychologist-Manager Journal. 2007;10:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sallows G. O, Graupner T. D. Intensive behavioral treatment for children with autism: Four-year outcome and predictors. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2005;110:417–438. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110[417:IBTFCW]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten R, Axelrod S, Bailey J. S, Favell J. E, Foxx R. M, Iwata B. A, Lovaas O. I. The right to effective behavioral treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21:381–384. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]