Abstract

Background

Hyperglycemia in the adult inpatient population remains a topic of intense study in U.S. hospitals. Most hospitals have established glycemic control programs but are unable to determine their impact. The 2009 Remote Automated Laboratory System (RALS) Report provides trends in glycemic control over 4 years to 576 U.S. hospitals to support their effort to manage inpatient hyperglycemia.

Methods

A proprietary software application feeds de-identified patient point-of-care blood glucose (POC-BG) data from the Medical Automation Systems RALS-Plus data management system to a central server. Analyses include the number of tests and the mean and median BG results for intensive care unit (ICU), non-ICU, and each hospital compared to the aggregate of the other hospitals.

Results

More than 175 million BG results were extracted from 2006–2009; 25% were from the ICU. Mean range of BG results for all inpatients in 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009 was 142.2–201.9, 145.6–201.2, 140.6–205.7, and 140.7–202.4 mg/dl, respectively. The range for ICU patients was 128–226.5, 119.5–219.8, 121.6–226.0, and 121.1–217 mg/dl, respectively. The range for non-ICU patients was 143.4–195.5, 148.6–199.8, 145.2–201.9, and 140.7–203.6 mg/dl, respectively. Hyperglycemia rates of >180 mg/dl in 2008 and 2009 were examined, and hypoglycemia rates of <40 mg/dl (severe) and <70 mg/dl (moderate) in both 2008 and 2009 were calculated.

Conclusions

From these data, hospitals can determine the current state of glycemic control in their hospital and in comparison to other hospitals. For many, glycemic control has improved. Automated POC-BG data management software can assist in this effort.

Keywords: blood glucose, hospital, hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, ICU

Introduction

The impact of aggressive glucose control in hospitals, and the critical care setting in particular, continues to be an area of intense study. While the general clinical consensus regards hyperglycemia as a dangerous condition that should be carefully managed, ongoing research has produced variable results related to disparate patient populations, blood glucose (BG) targets, and insulin treatment strategies.1–7 Consequently, expert opinions regarding optimal target range and management strategies have not been definitive.8,9 Additionally, questions have been raised about the safety of intensive insulin therapy due to the potential harm of iatrogenic hypoglycemia.10–12 Regardless of this ongoing inquiry, many hospitals have implemented or are moving toward establishing glycemic control programs in an effort to manage inpatient hyperglycemia, particularly in the critically ill.13,14 These programs are most successful with multidisciplinary involvement; extensive, coordinated, multipronged clinician education; and measurement through quality improvement approaches.15,16 While someprograms have been in place for several years now, reports on the current state of glycemic control in hospitals have demonstrated that considerable opportunity exists for improvement.17,18 A critical finding from surveys directed at determining current glycemic control practices indicates that most hospitals are, in fact, unable to determine their current glucose metrics17–19 and to measure the impact of their glycemic control programs because the hospitals do not have access to data to track the current state and improvement.20,21

The Remote Automated Laboratory System (RALS) Report software [Medical Automation Systems (MAS), Charlottesville, VA] was designed to meet this need.17 The RALS Report enables participants to review their facilities’ glucose metrics compared to a national benchmark of data gathered from 576 U.S. hospitals. This benchmarking initiative utilizes BG measures captured by point-of-care (POC) glucose meters to provide high-level analyses of the state of glycemic control in hospitalized patients.

Methods

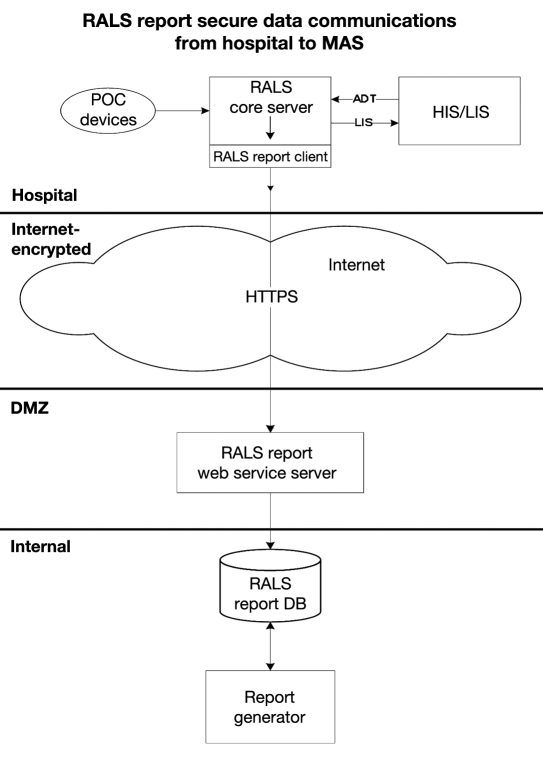

The hospitals in this analysis employed standard bedside glucose meters (ACCU-CHEK® Inform, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) downloaded to the RALS-Plus (MAS, Charlottesville, VA) a well-established POC test information management system.22 A proprietary software application was added to the existing RALS-Plus data management system in each hospital site, with subscription to the benchmarking reports. This application automatically extracts de-identified patient BG levels, which are then transferred via a secured internet connection to MAS, where reports are created and sent to the subscribers electronically. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

A proprietary software application is added to the existing RALS-Plus data management system in each hospital site. This application automatically extracts de-identified patient BG data, which are transferred via a secured internet connection to MAS, where reports are created and sent to the subscribers electronically. DMZ refers to “demilitarized zone”, a computer term referring to a server outside the MAS company firewall that provides an extra layer of security.

Participating hospital data include date, time, result of BG measure, and download location (nursing unit). Patient-specific data, such as age, sex, race, diagnosis, level of illness severity, or outcomes data, are not available. For this report, adult inpatient BG data from January 2006 through December 2009 was extracted. Out-of-range values of “LO” (<10 mg/dl) and “HI” (>600 mg/dl) were discarded as an exact measure was not available. The number of HI/LO values totaled <0.4% of the measurements. Additionally, all pediatric and outpatient data were excluded from this analysis as they reflect clinically different patient populations.

Hospital Selection

Participating hospitals were included through self-selection based on interest and willingness to complete a business agreement allowing de-identified data streaming to a central server prior to a data collection deadline. More than 1500 hospitals with RALS-Plus capability were invited to participate in the RALS-Annual Report. Confidentiality was guaranteed for the identity of participating hospitals and their data.

Statistical Analysis

Intensive care unit (ICU) and non-ICU download locations were analyzed separately and in combination. Glucose metrics included the mean and median BG results and the mean of all BG means and the mean of all BG medians for three separate categories per hospital (1) all inpatients combined, (2) ICU patient population only, and (3) non-ICU patients only. Rates of hyper-glycemia and hypoglycemia were analyzed in the same manner. Due to variations in the definition of recommended inpatient glucose levels,13 hyperglycemia was defined as BG >180 mg/dl; hypoglycemia was defined as BG <40 mg/dl (severe hypoglycemia) and <70 mg/dl (moderate hypoglycemia). Lowest mean BG and highest mean BG were determined by rank-ordering the hospital-level mean of all measurements. All analyses used measurement-level data rather than by-patient-level data to calculate individual hospital metrics. A comparison of each hospital results with the aggregate of all hospitals and quartile ranking was also provided to the participant. Quartile 1 includes those hospitals with the lowest mean, while quartiles 2, 3, and 4 include hospitals with increasing hospital-level mean values. Aggregate results for the individual years 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009 are presented in this report. All descriptive analyses were done using structured query language server data management system.

Results

A cumulative total of >175 million BG measurements collected from 576 hospitals were submitted from 2006 to 2009. A majority of the hospitals had ICUs (n = 533), were small (<200 beds, 47.4%), and located in urban areas (71.5%) in the southern U.S. region (47.7%). See Table 1 for participating hospital characteristics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study and U.S. Hospitalsa

| Study hospitals (N= 576) | U.S. hospitals (N = 4936b) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of beds, n (%) | ||

| <200 | 273 (47.4) | 3532 (71.6) |

| 200–299 | 125 (21.7) | 619 (12.5) |

| 300 –399 | 80 (13.9) | 368 (7.5) |

| ≥400 | 98 (17.0) | 417 (8.4) |

| Hospital type, n (%) | ||

| Academic | 15 (2.6) | 413 (8.4) |

| Urban | 412 (71.5) | 2514 (50.9) |

| Rural | 148 (25.7) | 2009 (40.7) |

| Region, n (%) | ||

| Northeast | 73 (12.7) | 680 (13.8) |

| Midwest | 117 (20.3) | 1422 (28.8) |

| South | 275 (47.7) | 1919 (38.9) |

| West | 110 (19.1) | 915 (18.5) |

Based on American Hospital Association (AHA) Hospital Statistics, published by 2007 Health Forum LLC, USA, 2009.

This encompasses all U.S. community hospitals, defined as nonfederal, short-term general, and specialty hospitals, whose facilities and services are available to the public. The AHA Hospital Statistics categorizes hospitals into urban and rural, but does not report academic status of hospitals. Study sample differs from national population of hospital in size, type, and region (p < .05).

Mean BG results remained relatively constant for the entire hospital inpatient population and the separate ICU (25%) and non-ICU (75%) populations over the 4 study years (Table 2). Mean BG levels varied widely among the hospitals, with the range of lowest and highest ICU means being significantly wider (lower and higher) than the range of the non-ICU means (p < .001) and likely reflective of the intensity of glycemic control and the severity of illness in the ICU patients.

Table 2.

2009 RALS-Annual Report Analyses for All Hospital Participantsa

| Participating hospital statistics (mg/dl) | All measurements | ICU measurements | Non-ICU measurements | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

| Lowest mean BGa | 142 | 146 | 141 | 141 | 128 | 119 | 122 | 121 | 143 | 149 | 145 | 141 |

| Highest mean BGb | 202 | 201 | 206 | 202 | 227 | 220 | 226 | 217 | 196 | 200 | 202 | 204 |

| Mean BG (displayed on .ppt)c | 163 | 164 | 162 | 165 | 153 | 150 | 152 | 157 | 166 | 168 | 166 | 168 |

| Median- mean BGd | 167 | 166 | 168 | 169 | 162 | 159 | 161 | 168 | 168 | 170 | 169 | 171 |

| Mean- mean BGe | 166 | 167 | 167 | 170 | 163 | 161 | 163 | 168 | 168 | 170 | 169 | 171 |

Assumptions: (1) BG data used is de-identified patient POC-BG data contained within the hospital RALS-Plus database, (2) ICU locations were identified according to the locations provided by the hospital, and (3) pediatric, neonatal, nursery, neonatal ICU, emergency room, and outpatient areas were excluded.

Value was determined by obtaining the mean result from each hospital and determining the lowest mean of all hospital means.

Value was determined by obtaining the mean result from each hospital and determining the highest mean of all hospital means.

Value was determined by adding all the results together and calculating the mean (average) result.

Value was determined by adding the mean result obtained from each of the hospitals and determining the median of all hospital means.

Value was determined by adding the mean result obtained from each of the hospitals and determining the mean of all hospital means.

While even minor differences are statistically significant due to the sample size effect, the majority (62% of ICU, 84% of non-ICU) of hospital means can be found within the recommended acceptable glucose range (140–180 mg/dl) for hospital patients.13

An example of an individual hospital summary is presented in Table 3. As can be noted for this hospital, the number of ICU BG measurements in 2008 nearly doubled from the previous year, and the mean ICU BG decreased from 142 to 136 mg/dl (p < .001). The quartile limits are also provided in this table for hospital reference in the range of BG means within this large sample.

Table 3.

2009 RALS-Annual Report for Individual Hospital Participants (Quartile Ranking 1a)

| All measurements (mg/dl) | ICU measurements (mg/dl) | Non-ICU measurements (mg/dl) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

| Mean BG | 158 | 155 | 152 | 151 | 146 | 142 | 136 | 142 | 160 | 157 | 158 | 159 |

| Total POC-BG test results | 99,253 | 113,958 | 127,910 | 129,567 | 15,569 | 17,697 | 34,589 | 36,454 | 83,684 | 96,261 | 93,321 | 93,113 |

The hospital’s quartile is a number from 1 to 4. Quartiles provide a rough approximation of a hospital’s performance relative to all participating hospitals. If hospital mean BG levels are arranged in order from lowest to highest, then one-quarter of hospitals with the lowest mean BG levels are assigned a quartile of 1, representing superior relative performance. Successive quarters are assigned quartiles of 2, 3, and 4. The quartile ranges are listed in Table 3a.

Hypoglycemia and Hyperglycemia

As shown in Table 4, mean hospital hypoglycemia rates were significantly lower for both severe and moderate hypoglycemia in 2009 in both ICU and non-ICU measures (p < .001). The reverse was seen with hyperglycemia, which increased during that same duration by significantly more (p < .0001).

Table 3a.

Hospital Quartile Ranges, by Category, from 2006-2009.

| Category | Quartile | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 1 | 142–160 | 142–161 | 141–159 | 141–162 |

| All | 2 | 162–167 | 161–166 | 159–167 | 162–169 |

| All | 3 | 167–173 | 167–174 | 167–174 | 169–177 |

| All | 4 | 172–202 | 174–201 | 174–206 | 177–202 |

| ICU | 1 | 125–150 | 109–149 | 122–149 | 121–155 |

| ICU | 2 | 150–162 | 149–159 | 149–161 | 155–168 |

| ICU | 3 | 163–174 | 159–173 | 161–174 | 168–181 |

| ICU | 4 | 174–227 | 173–220 | 174–252 | 181–217 |

| Non-ICU | 1 | 143–163 | 142–164 | 145–162 | 141–164 |

| Non-ICU | 2 | 163–168 | 164–170 | 162–169 | 164–171 |

| Non-ICU | 3 | 168-174 | 170–175 | 169–175 | 171–177 |

| Non-ICU | 4 | 174-196 | 175–200 | 175–202 | 177–204 |

Table 4.

RALS-Annual Report 2008 & 2009: Hypoglycemia and Hyperglycemia Analysis

| Test Category | 2008 | 2009 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of tests | % of total tests | Number of tests | % of total tests | |

| Total BG levels | ||||

| All | 29,771,581 | 100 | 49,924,503 | 100 |

| ICU | 7,684,118 | 100 | 12,345,519 | 100 |

| Non-ICU | 22,087,464 | 100 | 37,578,984 | 100 |

| BG <40 mg/dl | ||||

| All | 143,928 | 0.48 | 196,700 | 0.39 |

| ICU | 35,604 | 0.46 | 47,500 | 0.38 |

| Non-ICU | 108,324 | 0.49 | 149,200 | 0.40 |

| BG <70 mg/dl | ||||

| All | 1,031,261 | 3.46 | 1,544,799 | 3.09 |

| ICU | 238,710 | 3.11 | 325,191 | 2.63 |

| Non-ICU | 792,551 | 3.59 | 1,219,608 | 3.25 |

| BG >180 mg/dl | ||||

| All | 8,939,608 | 30.03 | 15,721,327 | 31.49 |

| ICU | 1,810,873 | 23.57 | 3,211,117 | 26.01 |

| Non-ICU | 7,128,735 | 32.28 | 12,510,210 | 33.29 |

Discussion

These data represent the largest inpatient database of BG results in the United States and allow a unique view of the state of inpatient glycemic control. The data are supported by other evaluations of hospital glycemic control in U.S. hospitals, where there was wide variation in hospital performance, hyperglycemia was common, and glucose control was suboptimal.18,22 A distinct advantage of this type of analysis is the complete automation of data collection without the need for hospital manual intervention and manipulation in order to monitor improvement in glycemic management.

The mean BG in ICU patients was lowest in 2007 (149.8 mg/dl), increased slightly in 2008 (151.6 mg/dl), and increased again in 2009 (157.3 mg/dl) (p < .001). This may reflect the emerging evidence from the Normoglycemia in Intensive Care Evaluation-Survival Using Glucose Algorithm Regulation (NICE-SUGAR) study.8 NICE-SUGAR reported that glucose levels between 140 and 180 mg/dl in critically ill patients were tolerated and safer than lower targets that added risk of hypoglycemia.8 However, overall there has been little clinically meaningful change, suggesting that hospitals are maintaining their glycemic control initiatives, with roughly 60% achieving the standard advised by the consensus report of the American Diabetes Association/American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (ADA/AACE).13

Total hospital mean results were lowest in 2008 (162.0 mg/dl) and increased in 2009 (165.3 mg/dl) (p < .001). Note that the lowest mean BG for ICU in an institution was relatively stable in 2008 and 2009, with results of 121.6 mg/dl compared to 121.1 mg/dl, respectively, while hypoglycemia rates for both ICU and non-ICU patients dropped from 2008 to 2009, as seen in Table 2. The hypoglycemia rate of <40 mg/dl for all tests decreased from 0.48% in 2008 to 0.39% in 2009, and the <70 mg/dl range decreased from 3.46% in 2008 to 3.09% in 2009 (p < .0001). This same trend occurred in the ICU areas. The <40 mg/dl range went from 0.46% in 2008 to 0.38% in 2009, and the <70 mg/dl range went from 3.11% in 2008 to 2.63% in 2009 (p < .001) (see Table 4).

The study was limited by the self-selection of the participants in agreeing to allow data aggregation in return for their benchmarked data. The current participants represent approximately 38% of the total RALS-Plus user hospital population and are not necessarily representative of the U.S. hospital population. Interpretations of these findings are constrained by the absence of specific patient characteristics such as diagnosis and severity of illness, which would allow further subgroup analyses. Additionally, details of glycemic control program information, such as BG target ranges and management protocols, are not known for this report, although evidence in the measurement frequency and time between measures allows for patient-level analyses and examination of BG trends in individual hospital ICUs. These analyses were beyond the intent of this article to describe an automated reporting technology for hospitals. A second Web-based benchmarking report, GlucometricsTM, is available to hospitals without RALS connectivity and will offer reports in the future.21

Currently, there is no consensus on how to best measure and summarize glycemic control (glucometrics) in the hospital, and a variety of reporting measures have been suggested.18,19,22 These reports are the first means for a hospital to determine its current and ongoing state of glucose control with reference to an external benchmark. A database of this size and scope is also useful in allowing high-level metrics of inpatient glycemic control in U.S. hospitals, as reported by Cook and colleagues.17 Although there is no standardized approach toward glucose control in the inpatient setting, there is scientific consensus that severe hyperglycemia has deleterious consequences for patients. The 2009 RALS Report revealed that over 31.4% of all adult inpatients had mean BG values >180 mg/dl, and over 26% of ICU patients had mean BG values >180 mg/dl. This demonstrates that a significant number of patients continue to be exposed to hyperglycemia and related complications.2,3,8 Hospitals can use their institution’s reports to examine their current glucose control as it relates to their quality of care and then adjust clinical practice as it pertains to patient glycemic management. Finally, the metrics presented here can assist in defining performance standards as a step toward improving glycemic managagment for individual hospitals and across health systems.

Conclusion

The RALS Report is designed to give caregivers and hospital administrators the ability to monitor BG trends in their hospital and track the impact of implementing glycemic control protocols for improving patient outcomes. The volume of test results automatically extracted for this mean BG analysis supersedes manual applications and provides a multihospital benchmark for best practices in glycemic control. Inpatient glycemic management remains an area of intense discussion in hospital patient care and is increasingly examined by national hospital quality agencies.14 This national benchmarking initiative offers the potential for further in-depth examination and creates opportunity for extended research.

Abbreviations

- (AHA)

American Hospital Association

- (BG)

blood glucose

- (ICU)

intensive care unit

- (MAS)

Medical Automation Systems

- (NICE-SUGAR)

Normoglycemia in Intensive Care Evaluation-Survival Using Glucose Algorithm Regulation

- (POC)

point of care

- (RALS)

Remote Automated Laboratory System

References

- 1.Malmberg K, Rydén L, Efendic S, Herlitz J, Nicol P, Waldenström A, Wedel H, Welin L. Randomized trial of insulin-glucose infusion followed by subcutaneous insulin treatment in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI study): effects on mortality at 1 year. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00126-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, Ferdinande P, Lauwers P, Bouillon R. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1359–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krinsley J. Association between hyperglycemia and increased hospital mortality in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1471–1478. doi: 10.4065/78.12.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furnary A, Gao G, Grunkemeier G, Wu Y, Zerr KJ, Bookin SO, Floten HS, Starr A. Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:1007–1021. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Meersseman W, Wouters PJ, Milants I, Van Wijngaerden E, Bobbaers H, Bouillon R. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Eng J Med. 2006;354:449–461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krinsley J. Effect of an intensive glucose management protocol on the mortality of critically ill patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:992–1000. doi: 10.4065/79.8.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, Meier-Hellmann A, Ragaller M, Weiler N, Moerer O, Gruendling M, Oppert M, Grond S, Olthoff D, Jaschinski U, John S, Rossaint R, Welte T, Schaefer M, Kern P, Kuhnt E, Kiehntopf M, Hartog C, Natanson C, Loeffler M, Reinhart K. Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):125–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, Blair D, Foster D, Dhingra V, Bellomo R, Cook D, Dodek P, Henderson WR, Hébert PC, Heritier S, Heyland DK, McArthur C, McDonald E, Mitchell I, Myburgh JA, Norton R, Potter J, Robinson BG, Ronco JJ. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1283–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiner RS, Weiner DC, Larson RJ. Benefits and Risks of Tight Glucose Control in Critically Ill Adults: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:933–944. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krinsley JS, Grover A. Severe hypoglycemia in critically ill patients: risk factors and outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2262–2267. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000282073.98414.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Krumholz HM, Xiao L, Jones PG, Fiske S, Masoudi FA, Marso SP, Spertus JA. Glucometrics in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: defining the optimal outcomes-based measure of risk. Circulation. 2008;117:1018–1027. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mowery NT, Guillamondegui OD, Gunter OL, Diaz JJ, Collier BR, Dossett LA, Dortch MJ, May AK. Severe hypoglycemia while on intensive insulin therapy is not an independent predictor of death after trauma. J Trauma. 2010;68:342–347. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181c825f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, DiNardo M, Einhorn D, Hellman R, Hirsch IB, Inzucchi SE, Ismail-Beigi F, Kirkman MS, Umpierrez GE, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. American Diabetes Association American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1119–1131. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 1):S13–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braithwaite SS, Magee M, Sharretts JM, Schnipper JL, Amin A, Maynard G, (Society of Hospital Medicine Glycemic Control Task Force) The case for supporting inpatient glycemic control programs now: the evidence and beyond. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(Suppl 5):S6–S16. doi: 10.1002/jhm.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moghissi E. Hospital management of diabetes: beyond the sliding scale. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71:801–808. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.71.10.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook CB, Kongable GL, Potter DJ, Abad VJ, Leija DE, Anderson MA. Inpatient glucose control: a glycemic survey of 126 U.S. hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:E7–E17. doi: 10.1002/jhm.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boord JB, Greevy RA, Braithwaite SS, Arnold PC, Selig PM, Brake H, Cuny J, Baldwin D. Evaluation of hospital glycemic control in US academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:35–44. doi: 10.1002/jhm.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg PA, Bozzo JE, Thomas PG, Mesmer MM, Sakharova OV, Radford MJ, Inzucchi SE. “Glucometrics”- assessing the quality of inpatient glucose management. Diabetes Technol Thera. 2006;8:560–569. doi: 10.1089/dia.2006.8.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badawi O, Yeung SY, Rosenfeld BA. Evaluation of glycemic control metrics for intensive care unit populations. Am J Med Quality. 2009;24:310–320. doi: 10.1177/1062860609336366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas P, Inzucchi S. An internet service supporting quality assessment of inpatient glycemic control. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2(3):402–408. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook CB, Elias B, Kongable GL, Potter DJ, Shepherd KM, McMahon D. Diabetes and hyperglycemia quality improvement efforts in hospitals in the United States: current status, practice variation, and barriers to implementation. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:219–230. doi: 10.4158/EP09234.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menke G, Anderson M, Zito D, Kongable GL. Medical Automation Systems and a brief history of point-of-care informatics. Point of Care. 2007;6:154–159. [Google Scholar]