Abstract

Sleep fragmentation (SF) and intermittent hypoxia and hypercapnia are the primary events associated with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). We previously found that SF eliminates ventilatory long-term facilitation and attenuates poikilocapnic hypoxic ventilatory responses (HVR). This study examined the effect of SF on isocapnic HVR and hypercapnic ventilatory responses (HCVR), and investigated the time course of and the role of adenosine A1 receptors in these SF effects in conscious adult male Sprague-Dawley rats. SF was achieved by periodic, forced locomotion in a rotating drum (30 s rotation/90 s stop for 24 h). Ventilation during baseline, isocapnic hypoxia (11% O2 plus 4% CO2) and hypercapnia (6% CO2) was measured using plethysmography. About 1 h after 24 h SF, resting ventilation, arterial blood gases and isocapnic HVR (control: 169.3 ± 11.5% vs. SF: 170.0 ± 10.3% above baseline) were not significantly changed, but HCVR was attenuated (control: 172.8 ± 17.5% vs. SF: 129.5 ± 9.6%; P=0.003). This attenuated HCVR then returned spontaneously to the control level ~4 h after SF (168.9 ± 12.1%). This HCVR attenuation was also reversed (184.0 ± 17.5%) by systemic injection of the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist 8-CPT (2.5 mg/kg) shortly after SF, while 8-CPT at this dose had little effect on HCVR in control rats (169.9 ± 11.8%). Collectively, these results suggest that: (1) 24 h SF does not change isocapnic HVR but causes an attenuation of HCVR; and (2) this attenuation lasts for only a few hours and requires activation of adenosine A1 receptors.

Keywords: Respiratory control, Sleep fragmentation, Chemoresponsiveness, Hypercapnia, Adenosine receptors, Plasticity

1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a major sleep disorder, affects at least 2–4% of the adult American population (Young et al., 1993) and leads to many pathological consequences, e.g., daytime sleepiness, neurocognitive deficits and cardiovascular diseases (Brooks et al., 1997; Lavie et al., 2000; Nieto et al., 2000; Peppard et al., 2000; Faccenda et al., 2001; Shahar et al., 2001). OSA is characterized by recurrent upper airway collapse due to decreases in upper airway dilator muscle activity during sleep in those who are anatomically predisposed. Collapse causes intermittent hypoxemia and hypercapnia, and sleep fragmentation (SF). OSA, sleep disruption (including SF and sleep deprivation) and chronic intermittent hypoxia have been extensively studied in terms of their effects on some of the pathological consequences and other physiological functions. However, the effects of sleep disruption on hypoxic (HVR) and hypercapnic (HCVR) ventilatory responses have not been adequately studied. Results of different studies are also not very consistent; some of them are even contradictory.

Several studies have examined the effect of sleep deprivation on respiratory chemoreflexes during wakefulness in healthy adults, and they found that 24–36 h sleep deprivation significantly decreased HVR (White et al., 1983) and HCVR (Cooper and Phillips, 1982; Schiffman et al., 1983; White et al., 1983). However, a more recent study found no significant change in HCVR over 24 h sleep deprivation when subjects are kept under strictly controlled behavioral and environmental conditions (Spengler and Shea, 2000). Also, a single night of sleep deprivation did not produce any change in HCVR in healthy young subjects (Ballard et al., 1990). In contrast, there have been only a few studies investigating the effects of SF on respiratory chemoreflexes. In one study, 2–3 nights of SF had minimal effect on HVR and HCVR in dogs during subsequent afternoon sleep (Bowes et al., 1980). In the other study, 2 nights of SF did not change the slope or position of the HCVR curve in healthy humans (Espinoza et al., 1991). To our knowledge, however, the time course of those sleep disruption-induced impairments in ventilatory chemoreflexes has not been studied. The above studies measured HVR and HCVR several hours after sleep disruption. Thus it is unclear whether SF did not produce any impairment or the produced impairment had disappeared when the measurement was made. In addition, the neurochemical mechanisms mediating the potential sleep disruption-induced changes in HCVR have never been explored.

A recent study in our laboratory has demonstrated that ventilatory long-term facilitation is eliminated and poikilocapnic HVR is attenuated shortly after 24 h SF, and that the SF-impaired ventilatory long-term facilitation and poikilocapnic HVR are restored and improved, respectively, by systemic adenosine A1 receptor antagonism (McGuire et al., 2008b). In that study, however, PaCO2 was not controlled and HCVR was not measured. The present study was thus designed to examine: (1) the effects of 24 h SF on isocapnic HVR and HCVR, (2) their potential time courses, and (3) the role for adenosine A1 receptors in the SF-induced effects. We hypothesized that 24 h SF attenuates both ventilatory chemoreflexes, and the attenuation can be reversed by adenosine A1 receptor antagonism.

2. Methods

All experimental procedures used herein were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals. Experiments were conducted on adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–475 g, about 3–5 month old; colony CDIGS, Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA). These rats were housed in cages under controlled room temperature (~22 °C) with a 12 h light–12 h dark cycles (light-on from 08.00 h to 20.00 h). Rats had ad libitum access to food and water.

2.1. Sleep fragmentation (SF) treatment

Individual rats were placed in a rotating drum made of Plexiglas (~30 cm in length and diameter) with food and water ad libitum. The 24 h SF was achieved by periodic, forced locomotion (30 s rotation followed by 90 s stop) at a speed of ~1.5 rotation/min for a 24 h period (started at 08.00 h and ended at 08.00 h on the following morning), as previously described (McGuire et al., 2008b). This SF protocol successfully produced up to ~30 sleep interruptions per hour (McGuire et al., 2008b), a frequency often observed in OSA patients (Wiegand and Zwillich, 1994). Before SF treatment, rats were given 2 days to acclimatize to the drum (~30 min periodic rotation in each day).

Repeated arousals/awakenings and relatively short quiescent periods do not allow for the development of normal stages 3 and 4 deep sleep, and disrupt other stages of sleep. This SF protocol was continued for 24 h to prevent rats from sleep compensation during their active period. OSA patients usually do not nap extensively during the daytime, but rats tend to get more sleep in their usual active period, if they are sleep deprived during their inactive period (Lancel and Kerkhof, 1989). The purpose of this SF treatment is not to produce sustained sleep deprivation but to mimic the SF experienced by OSA patients, while excluding other concomitant events of OSA, such as hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Thus we aimed to design our SF protocol to repeatedly interrupt sleep while avoiding important changes in total sleep time.

2.2. Locomotion control (LC) treatment

The 24 h LC treatment was also achieved by periodic, forced locomotion in the same drums as previously described (McGuire et al., 2008b). Both rotation and stop times were lengthened (15 min rotation/45 min stop) to allow for deep and consolidated sleep during the 45 min stop periods. The ratio of the rotation and stop times (1:3), the rotation speed (~1.5 rotation/min) and overall treatment time (24 h) remained the same. This LC protocol was specifically designed to rule out possible confounding effects from exercise/movement or other non-specific stresses experienced from being housed in the drum (note that the control intervention for all other parts of the study was 24 h normal cage housing, see Experimental protocols below).

2.3. Ventilatory measurement

Ventilation was measured in awake rats using whole body plethysmography (Buxco Electronics, Sharon, CT, USA) as previously described (McGuire et al., 2008a; McGuire et al., 2008b). The apparatus consisted of two chambers, an animal chamber (~3 liters) and a reference chamber. A differential pressure transducer was used to measure the pressure differences between the two chambers and was connected to an amplifier whose output was fed into a digital data acquisition system (Buxco Biosystem XA, Sharon, CT). The plethysmographic system was calibrated by injecting a known volume (5 ml) of air into the animal chamber with a syringe. Barometric pressure, rats’ rectal temperature and body weight were measured before each experiment and inputted to the data acquisition system. The temperature and humidity of the animal chamber were also measured. These parameters were used in calculating tidal volume in milliliters per 100 g (BTPS). The flow of air or gas mixture delivered to the animal chamber was kept constant at 3 l/min. The rat was placed in the animal chamber with air flowing through and allowed to adapt to the chamber for about 30 min before the start of the measurements. Before experiments, rats were also given 1–2 days to acclimatize to the animal chamber (~30 min staying in the chamber each day).

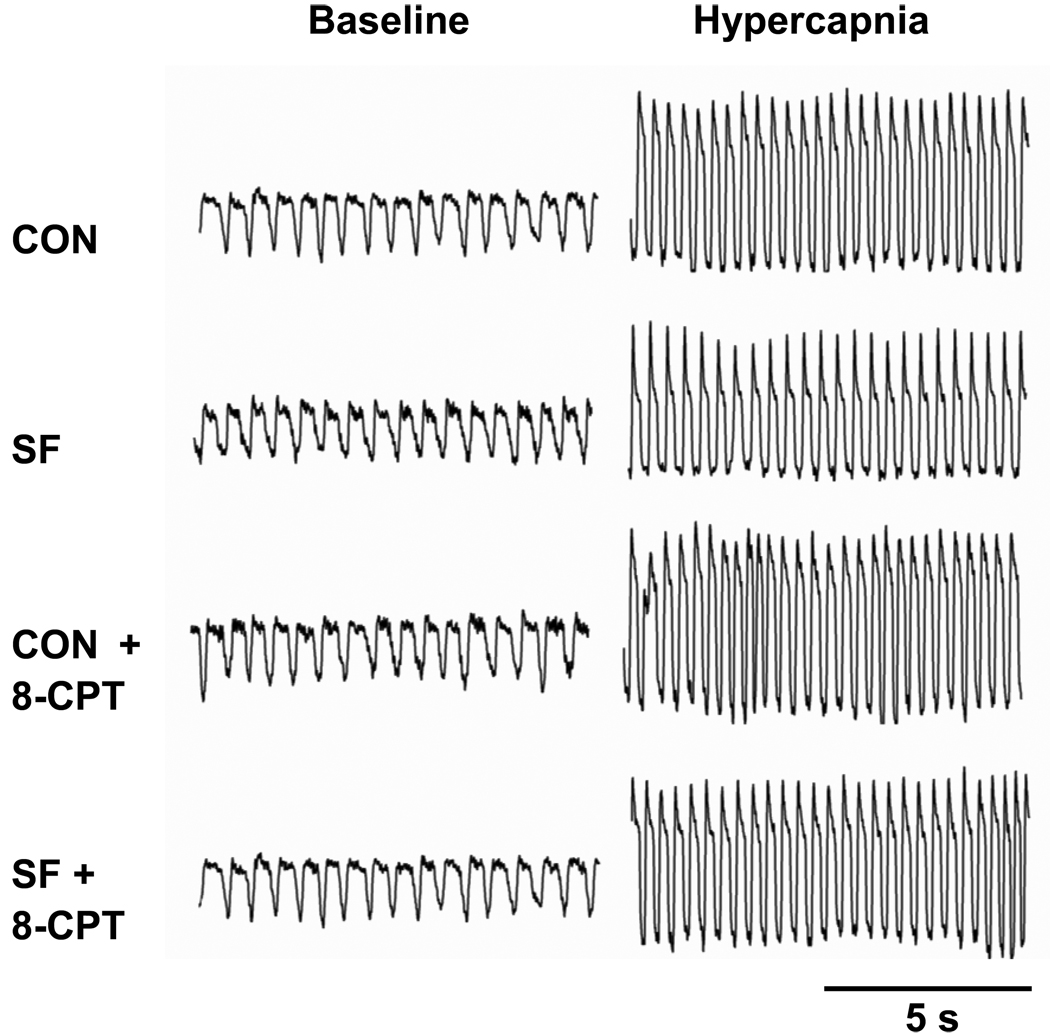

During designated time periods, ventilatory parameters were measured continuously in 10 s time bins following a strict rule, i.e., these parameters were measured only when rats were observed to be awake and in a quiet state. Our criteria for data acceptance are the combination of (1) open eyes, (2) no body movement, and (3) a normal breathing pattern displayed continuously on the computer screen (see Fig. 1). These strict rejection criteria helped to generate more consistent results. If the normal breathing pattern was disturbed by anything (e.g., rats’ moving, sniffing or sighing) during recording, the whole data set collected in that 10 s bin (or bins) would be rejected from the analysis. If rats were observed to be sleeping (or in a sleepy state), we would awaken them before collecting data or have the collected data rejected. Thus all the data presented were collected when rats were in a quiet and completely awake state.

Fig. 1.

Representative traces of breathing pattern (airflow) recorded by plethysmography before (baseline) and during hypercapnia (6% CO2) from one rat. Inspiration is represented by the downward deflection of the recording. These traces were recorded ~1 h after 4 different treatments [control (CON), sleep fragmentation (SF), CON + 8-CPT and SF + 8-CPT], separated by one-week intervals. 8-CPT is a selective antagonist of adenosine A1 receptors.

2.4. Isocapnic hypoxic and hypercapnic exposures

Ventilatory parameters were measured for about 10 min as baseline controls prior to each hypoxic exposure. During this resting period, air flowed into the animal chamber. During hypoxia, a gas mixture of 11% O2 and 4% CO2 balanced with N2 flowed into the chamber for 10 min. It took less than 1 min to shift from normoxia to the target hypoxia level inside the chamber. Hypoxia data were recorded during the last 5 min (i.e., between 5–10 min) of those 10-min isocapnic hypoxic exposures and then averaged. The procedure of hypercapnic exposure was identical to that of isocapnic hypoxic exposure except that the hypoxic gas mixture was replaced by the hypercapnic gas mixture of 6% CO2 in air. The O2 and CO2 concentration inside the chamber were continuously monitored.

2.5. Adenosine A1 receptor antagonism

The selective adenosine A1 receptor antagonist 8-cyclo-pentyl-theophylline (8-CPT) (Sigma-Aldrich, Natick, MA, USA) was systemically injected (2.5 mg/kg in DMSO, 1 ml, i.p.) shortly after SF treatment and ~30 min before the measurements. The vehicle (1 ml DMSO, i.p.) was also injected in drug control trials. 8-CPT is a widely used specific adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, which easily dissolves in DMSO solution and crosses the blood-brain barrier (Appel et al., 1995).

2.6. Experimental protocols

The present study included four series of experiments with modest numbers of rats undergoing multiple different treatments. Thus a counterbalanced crossover design was used for all. Series 1 investigated the effect of SF on isocapnic HVR. In this series (n=6), 3 rats underwent 24 h SF treatment and then 24 h normal cage housing (CON treatment) with one-week interval between them, while the other 3 rats underwent the opposite treatment sequence (i.e., first CON and then SF treatment). Isocapnic HVR was measured at 1 h and 4 h after SF or CON treatment. Series 2 (n=5) examined the time course of the change in HCVR after 24 h SF. Three rats underwent 24 h SF and then 24 h CON with one-week interval, while the other 2 rats received the opposite sequence. HCVR was repeatedly measured at 1 h, 2.5 h, 4 h and 5.5 h after either treatment. Series 3 (n=7) explored the role of A1 receptors in the SF effect on HCVR. Rats (n=2, 2, 2, 1) were randomly selected to receive the same 4 treatments but in 4 different fixed orders (1: CON, SF, CON+drug, SF+drug; 2: SF, CON+drug, SF+drug, CON; 3: CON+drug, SF+drug, CON, SF; and 4: SF+drug, CON, SF, CON+drug) with one-week intervals between any two of the treatments. HCVR was measured at 1 h and 4 h after each treatment. Series 4 (n=4) tested the effect of LC treatment on HCVR. Two rats underwent 24 h LC and 24 h CON with one-week interval, while the other 2 rats received the opposite order. HCVR was measured at 1 h and 4 h after either treatment.

2.7. Blood gas analysis

Separate rats (n=4) were anesthetized (pentobarbital sodium, 50 mg/kg, i.p.). An arterial catheter was inserted into the iliac artery via femoral artery. It was sutured in place and tunneled beneath the dorsal skin with the exit between the scapulae. The catheter was flushed with sterile, heparinized saline (100 Units/ml) to maintain patency and packaged in rat jacket. Antibiotic and analgesic were used for the first 24 hours after the surgery. Rats were allowed to recover for at least 1 week after surgery. The collection of blood samples was started ~30 min after SF or CON treatment. Arterial blood samples (0.2–0.3 ml) were taken during baseline (air) and during the last 2 minutes of the 10-min isocapnic hypoxia and 10-min hypercapnia, separated by ~30-min intervals. The blood samples were collected in heparinized 1 ml syringes and were analyzed immediately for blood gases and pH (Opti CCA-TS, Osmetech, Roswell, Georgia, USA) with correction for rectal body temperature. These rats underwent 24 h SF and CON treatment with one-week interval and counterbalanced order.

2.8. Statistical analysis

A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures, followed by the Student-Newman-Kuels post-hoc tests (SigmaStat version 3.0, Jandel Corporation), was used statistically to analyze within-subject differences between treatments in: (1) the blood gases (baseline vs. hypoxia or hypercapnia; CON vs. SF); (2) HCVR in the LC study (1 h vs. 4 h; CON vs. LC); (3) ventilatory parameters (ventilation, frequency and tidal volume) during baseline and hypoxia, and their isocapnic hypoxic responses (1 h vs. 4 h; CON vs. SF); (4) HCVR in the time course study (at 4 different time points; CON vs. SF); and (5) ventilatory parameters during baseline and hypercapnia, and their hypercapnic responses (drug vs. vehicle; CON vs. SF) 1 h (also 4 h) after SF. The within-subject differences in body weight and rectal temperature were statistically analyzed by a one-way ANOVA in the isocapnic HVR study, and by the two-way ANOVA in the (SF/drug) HCVR study. All results are means ± SE. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Arterial blood gases

The baseline blood gases were not significantly changed after 24 h SF treatment (P > 0.266 for both overall group effects; Table 1). In isocapnic hypoxia, PaCO2 was not significantly different from baseline (P=0.906), while PaO2 was decreased from baseline (P<0.05), with and without SF treatment (Table 1). However, PaO2 during isocapnic hypoxia was not significantly changed after SF treatment. These results suggest that isocapnia was maintained in the experiments and hypoxic levels were similar in control and SF rats. In hypercapnia, PaCO2 was significantly increased from baseline in control and SF rats (P<0.05). However, PaCO2 during hypercapnia was not significantly different between control and SF rats. PaO2 was also significantly increased from baseline in control and SF rats (P<0.05). However, there was no significant difference in PaO2 during hypercapnia between control and SF rats (Table 1). These results show that both PaCO2 and PaO2 were similar during hypercapnia in control and SF rats, suggesting that blood gas responses to isocapnic hypoxia or hypercapnia are not changed after 24 h SF treatment.

Table 1.

Arterial blood gases in rats with (SF) and without sleep fragmentation (CON) treatment

| Baseline (air) |

Isocapnic hypoxia (11% O2 + 4% CO2) |

Hypercapnia (6% CO2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaCO2 | CON | 40.7 ± 0.7 | 40.5 ± 0.9 | 51.4 ± 0.8* |

| (mmHg) | SF | 40.0 ± 0.9 | 40.0 ± 1.0 | 52.9 ± 1.0* |

| PaO2 | CON | 103.8 ± 1.4 | 64.0 ± 1.6* | 124.4 ± 2.5* |

| (mmHg) | SF | 101.6 ± 1.8 | 61.0 ± 1.4* | 122.2 ± 2.6* |

Data are means ± SE. (all n=4).

Significant difference from the corresponding baseline value (P<0.05).

3.2. Isocapnic HVR after 24 h SF treatment

Resting rectal temperature was not significantly changed after 24 h SF treatment (P=0.865, Paired t-test; Table 2). Resting ventilation was also not significantly changed 1 h or 4 h after 24 h SF treatment (P=0.892 for the overall SF effect; Table 2). The isocapnic HVR was not significantly different among the 4 conditions (1 h CON, 4 h CON, 1 h SF and 4 h SF; P>0.625 for the SF factor, time factor and their interaction; Fig. 2), neither were isocapnic hypoxic responses in frequency and tidal volume (Table 2). Collectively, these data suggest that 24 h SF treatment has minimal effect on the isocapnic HVR in awake rats.

Table 2.

Ventilatory responses to isocapnic hypoxia (11% O2 plus 4% CO2) in control (CON) and sleep fragmentation (SF) rats

| CON | SF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 4 h | 1 h | 4 h | ||

| Ventilation (ml/100g/min) |

Baseline | 47.9 ± 0.7 | 44.2 ± 0.9 | 47.9 ± 2.1 | 43.6 ± 1.9 |

| Hypoxia | 129.0 ± 6.8 | 117.8 ± 6.0 | 129.0 ± 6.0 | 116.4 ± 4.0 | |

| HR (%increase above baseline) |

169.3 ± 11.5 | 165.6 ± 8.2 | 170.0 ± 10.3 | 1 67.8 ± 6.9 | |

| Frequency (breaths/min) |

Baseline | 100.6 ± 3.4 | 94.7 ± 7.1 | 95.4 ± 5.8 | 88.7 ± 5.9 |

| Hypoxia | 169.1±7.4 | 159.7 ± 6.5 | 162.1±9.0 | 160.6 ± 6.9 | |

| HR (%increase above baseline) |

68.1±4.0 | 71.2 ± 8.4 | 70.8 ± 5.8 | 82.9 ± 6.7 | |

| Tidal Volume (ml/100g) |

Baseline | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 0.51±0.02 | 0.50 ± 0.02 |

| Hypoxia | 0.77 ± 0.02 | 0.74 ± 0.03 | 0.80 ± 0.02 | 0.73 ± 0.02 | |

| HR (%increase above baseline) |

59.4 ± 4.5 | 56.5 ± 6.4 | 57.7 ± 4.9 | 46.8 ± 6.7 | |

| Body weight (g) | 349.3 ± 33.6 | 321.2 ± 18.9 | |||

| Rectal temperature (°C) | 38.0 ± 0.3 | 38.1±0.2 | |||

Data are means ± SE. (all n=6). 1 h/4 h, measurements made at 1 h/4 h after CON or SF treatment; HR, hypoxic response (to 10-min 11% O2 plus 4% CO2) in ventilation, frequency and tidal volume: a % increase above baseline in the respective hypoxic value, calculated by the equation: 100 × (hypoxic value – baseline value)/baseline value. There is no significant difference in any parameters between 1 h and 4 h or between CON and SF groups (all P>0.05).

Fig. 2.

Isocapnic hypoxic ventilatory responses (HVR) in control (CON) and sleep fragmentation (SF) treated rats (n=6). The isocapnic HVR (to 10-min 11% O2 plus 4% CO2) was measured 1 h and 4 h after the CON or SF treatment, and was not significantly different between any 2 of the 4 groups (1 h CON, 4 h CON, 1 h SF and 4 h SF). These data are expressed as means ± SE.

3.3. HCVR after 24 h SF treatment

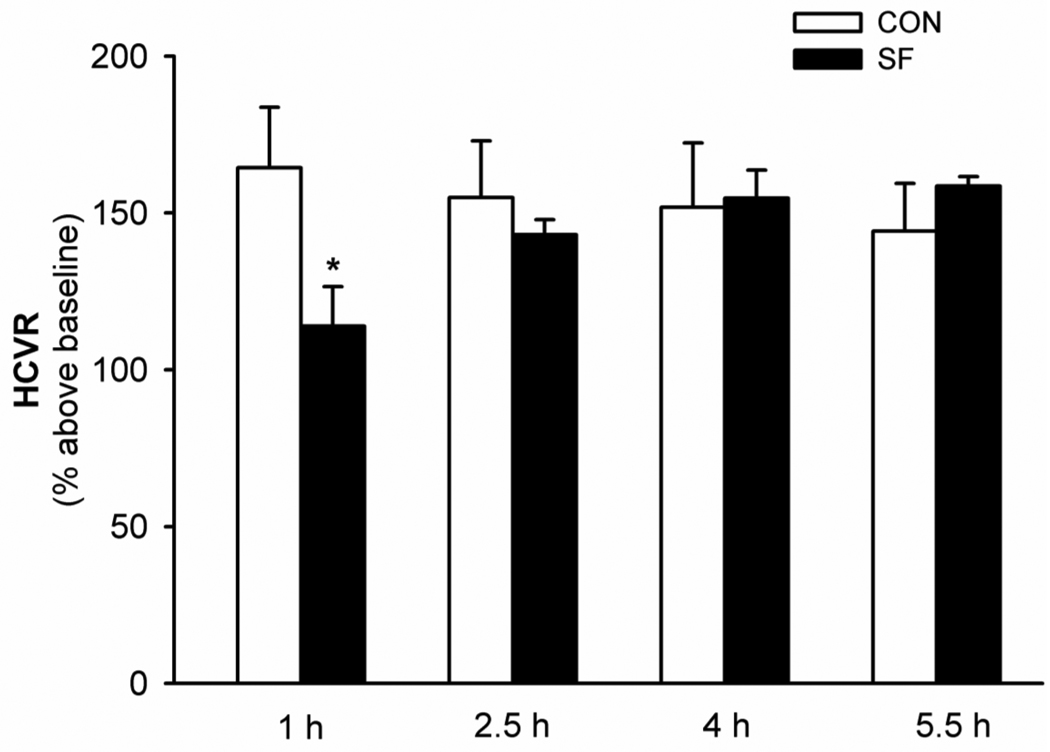

Time course of changes in HCVR after 24 h SF

There were no significant differences in HCVR measured at 4 different time points in CON rats (all P>0.283; Fig. 3). But, the 2-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction effect (F3,12=18.772; P<0.0001) between SF factor and time factor in HCVR data; HCVR was significantly decreased 1 h after SF compared with the control and other time points after SF (all P<0.018; Fig. 3). The HCVR after SF appeared to increase gradually and reach a plateau in ~4 h (Fig. 3). These data suggest that 24 h SF causes an attenuation of HCVR but the attenuated HCVR recovers spontaneously in a few hours.

Fig. 3.

The impaired hypercapnic ventilatory response (HCVR) after sleep fragmentation (SF) and its spontaneous recovery (n=5). HCVR (to 10-min 6% CO2) was measured 4 times repeatedly, at 1 h, 2.5 h, 4 h, and 5.5 h after CON or SF treatment. These data are expressed as means ± SE. * Significant difference from 1 h CON group and all other SF groups (all P<0.05).

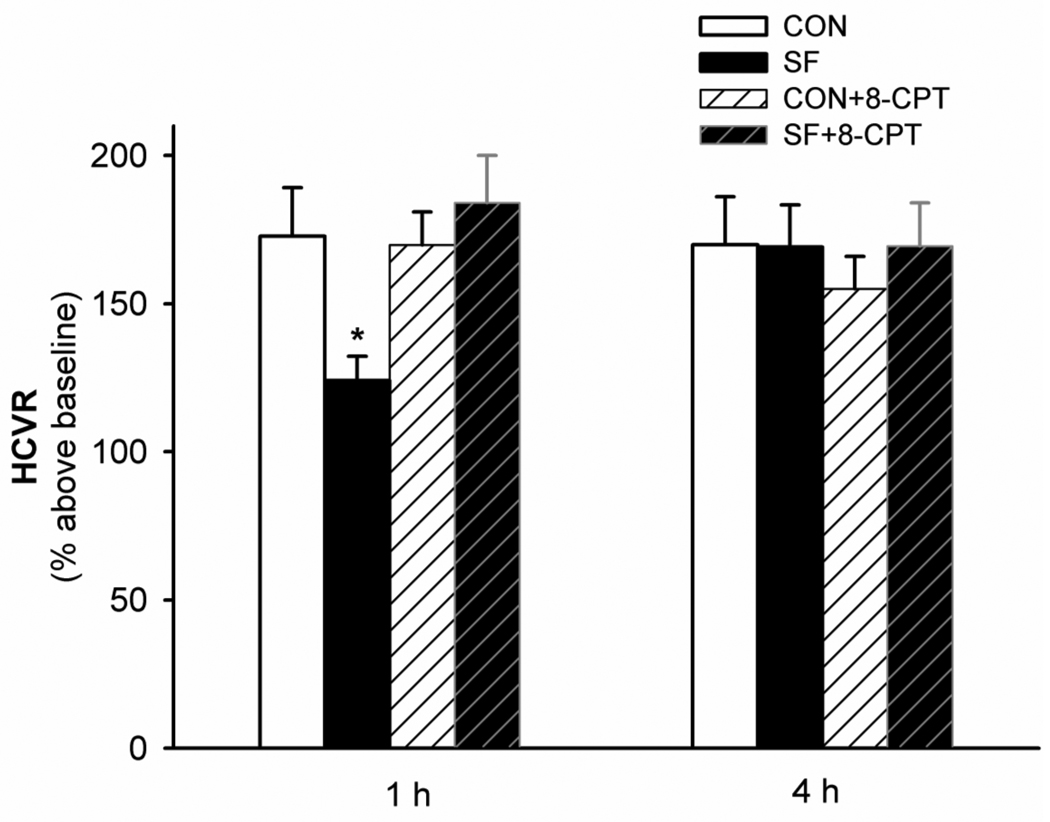

Role of A1 receptors in the SF-attenuated HCVR

Rectal temperature was not significantly changed after 24 h SF treatment and/or administration of 8-CPT, neither was resting ventilation (all P>0.1; Table 3). The 2-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction effect (F1,6=11.21; P=0.015) between the drug factor and SF factor, and a significant drug effect (F1,6=14.442; P=0.009) in the 1 h HCVR data (Fig. 4; Table 3). HCVR was significantly attenuated (P=0.003) 1 h after 24 h SF treatment (Figs. 1 and 4). Systemic injection of 8-CPT (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) shortly after SF reversed the attenuation of HCVR observed 1 h after SF (184.0 ± 17.5%; P<0.001 vs. SF; P=0.247 vs. CON+8-CPT), while the same 8-CPT injection had minimal effect on HCVR (169.9 ± 11.8%; P=0.795 vs. CON) in rats without SF. There were no significant differences in HCVR among the four groups (CON, SF, CON+8-CPT and SF+8-CPT) 4 h after 24 h SF treatment (all P>0.158; Fig. 4 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Ventilatory responses to hypercapnia (6% CO2) in rats with or without sleep fragmentation (SF) and/or adenosine A1 receptor antagonism (8-CPT)

| 1 h | 4 h | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | SF | CON+ 8-CPT |

SF+ 8-CPT |

CON | SF | CON+ 8-CPT |

SF+ 8-CPT |

||

| Ventilation (ml/100g/min) |

Baseline | 43.2±2.4 | 47.6±1.8 | 46.4±2.1 | 45.8±1.9 | 40.4±1.7 | 42.5±1.2 | 41.7±1.4 | 46.3±2.3 |

| Hypercapnia | 117.6±8.5 | 109.3±6.2 | 125.9±9.1 | 129.8±9.0 | 108.7±7.5 | 113.7±3.6 | 106.2±5.7 | 123.3±5.1 | |

| HCR(% increase above baseline) |

172.8±16.4 | 129.5±8.8* | 169.9±11.1 | 184.0±16.0 | 169.9±16.2 | 168.9±12.0 | 155.0±10.9 | 169.3±14.7 | |

| Frequency (breaths/min) |

Baseline | 105.3±4.4 | 98.6±3.7 | 114.9±3.9 | 92.7±3.2 | 94.0±3.6 | 94.6±3.4 | 99.7±2.1 | 100.6±5.5 |

| Hypercapnia | 166.5±7.3 | 140.7±9.3 | 184.3±7.3 | 159.5±7.4 | 162.7±5.8 | 151.4±6.3 | 160.1±5.8 | 163.5±5.1 | |

| HCR(% increase above baseline) |

58.5±4.4 | 42.3±6.5* | 61.0±6.4 | 71.9±4.3 | 73.6±5.4 | 60.9±8.2 | 61.3±8.3 | 64.7±8.3 | |

| Tidal Volume (ml/100g) |

Baseline | 0.41±0.01 | 0.49±0.02 | 0.40±0.01 | 0.50±0.02 | 0.43±0.01 | 0.46±0.02 | 0.42±0.01 | 0.47±0.04 |

| Hypercapnia | 0.71±0.04 | 0.79±0.04 | 0.69±0.05 | 0.82±0.06 | 0.67±0.04 | 0.76±0.03 | 0.66±0.03 | 0.76±0.04 | |

| HCR(% increase above baseline) |

71.7±7.6 | 61.7±4.6 | 70.2±11.5 | 64.3±8.7 | 56.9±11.3 | 68.6±10.2 | 58.8±5.1 | 64.8±9.1 | |

| Body weight (g) | 371.9±24.7 | 332.1 ±17.2 | 363±24.3 | 343.0±14.0 | |||||

| Body temperature (°C) | 38.1 ±0.2 | 38.2±0.1 | 38.0±0.2 | 38.4±0.1 | |||||

Data are means ± SE. (all n=7). CON, control rats; 1 h/4 h, measurements made at 1 h/4 h after SF; HCR, hypercapnic response (to 10-min 6% CO2) in ventilation, frequency and tidal volume: a % increase above baseline in the respective hypercapnic value, calculated by the equation: 100 × (hypercapnic value – baseline value)/baseline value.

Significant difference from all other corresponding 1 h groups (P<0.05).

Fig. 4.

The effect of systemic adenosine A1 receptor antagonism (8-CPT, 2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) on the sleep fragmentation (SF)-attenuated hypercapnic ventilatory response (HCVR). HCVR (to 10-min 6% CO2) was measured twice, at 1 h and 4 h after each of the 4 treatments (CON, SF, CON+8-CPT and SF+8-CPT). These data are expressed as means ± SE. * Significant difference from all other 1 h groups (P<0.05).

The SF-attenuated HCVR resulted mainly from changes in respiratory frequency, as there was also a significant interaction effect (P=0.009) between the drug and SF factor and a significant drug effect (P=0.032) in the 1 h hypercapnic frequency response data (Table 3). Hypercapnic frequency response was significantly attenuated 1 h after 24 h SF (P=0.027). The 8-CPT injection reversed this attenuation (P=0.002 vs. SF; P=0.112 vs. CON+8-CPT), while having minimal effect on hypercapnic frequency responses (P=0.722 vs. CON) in rats without SF. Although there also appeared to be a decrease in the hypercapnic tidal volume response 1 h after SF, this decrease was not significant (P=0.686 for the interaction effect; Table 3). These results suggest that 24 h SF treatment attenuates HCVR mainly via reducing hypercapnic frequency responses, and the SF-induced attenuation of both HCVR and the hypercapnic frequency response requires activation of adenosine A1 receptors.

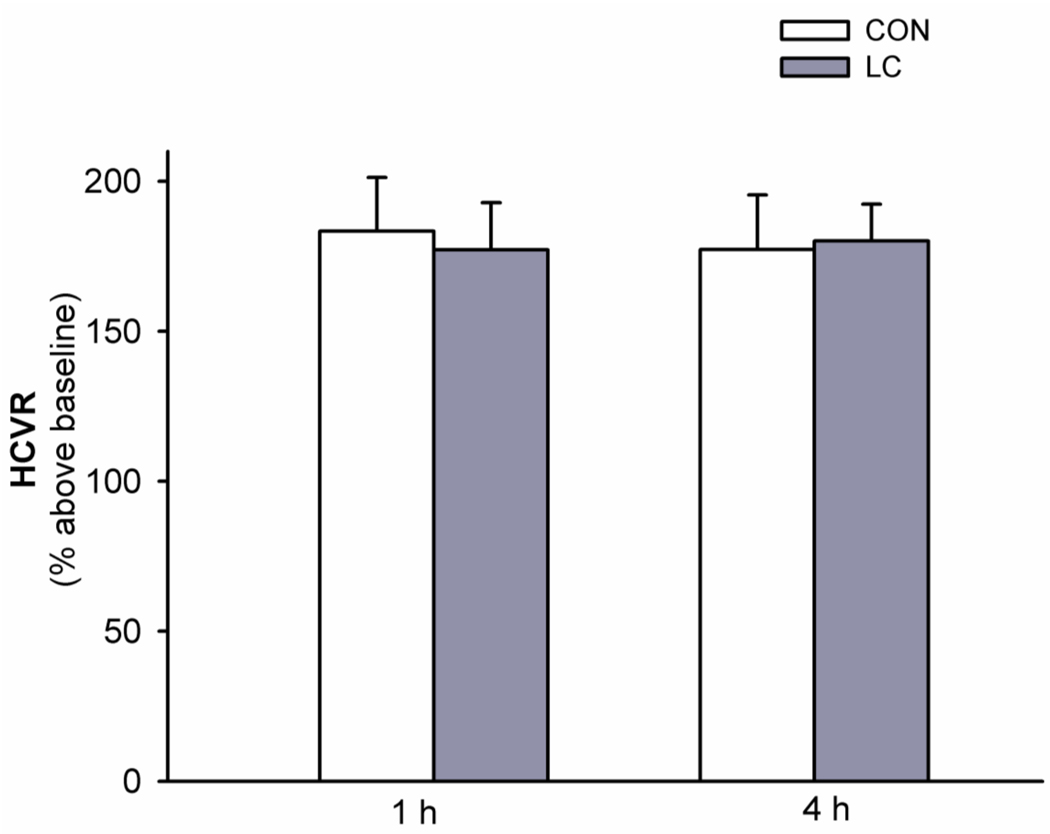

3.4. HCVR after 24 h locomotion control (LC) treatment

The 24 h LC treatment did not cause significant changes in rectal temperature (P=0.41, Paired t-test) or resting ventilation (all P>0.105). The control (i.e., without LC treatment) HCVR were similar to those in the above two hypercapnia studies (one-way ANOVA, F2,13 = 0.20; P= 0.821; Figs. 3, 4 and 5). HCVR was not significantly changed 1 h or 4 h after 24 h LC treatment (all P>0.21; Fig. 5). These results suggest that possible effects from locomotion per se and non-specific stresses associated with the rotating drum are not important factors causing the SF-induced HCVR attenuation.

Fig. 5.

The effect of locomotion control (LC) treatment on hypercapnic ventilatory responses (HCVR). HCVR (to 10-min 6% CO2) was measured twice, at 1 h and 4 h after the control (CON) and LC treatments. HCVR was not significantly different between any 2 of the 4 groups (1 h CON, 4 h CON, 1 h LC and 4 h LC). These data are expressed as means ± SE.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that isocapnic HVR was not significantly changed after 24 h SF treatment achieved by periodic, forced locomotion in a rotating drum (30 s rotation/90 s stop). In contrast, HCVR was attenuated 1 h after 24 h SF treatment, but spontaneously returned to its control level 4 h after SF. This attenuation of HCVR was also reversed by systemic injection of the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist 8-CPT (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) shortly after SF, while 8-CPT alone had minimal effect on HCVR in control rats. Possible confounding effects from forced locomotion per se and non-specific stress associated with the drum could be ruled out, as HCVR was not attenuated by the 24 h LC treatment. Collectively, these results suggest that 24 h SF attenuates HCVR but not isocapnic HVR in conscious rats, and this attenuation lasts for only a few hours and requires activation of adenosine A1 receptors.

4.1. Methodological consideration

In the present study, experiments were conducted on conscious, spontaneously breathing, freely moving rats, which provided a physiologically relevant way to study the SF effect on ventilatory chemoreflexes in the absence of confounding effects related to anesthesia, surgery and restraint. A complete within-subject design was adopted for all studies to reduce data variability and the total number of rats used. The potential confounding sequence and carryover effects were minimized by randomly assigning rats to different treatments (e.g., CON, SF, CON+drug and SF+drug in the hypercapnia study) in a counterbalanced order and by separating these treatments with 1-week interval(s). These measures, whose effects are somewhat reflected in the body weight, HVR and HCVR data (Figs. 1–5, Tab 2 and 3), appear to be proper for the purpose of minimizing the confounding factors. The LC effects on the time course of HCVR change or isocapnic HVR were not examined because we later found that the LC treatment had no effect on HCVR and even SF treatment did not change isocapnic HVR (our previous study has showed that 24 h SF, but not 24 h LC, attenuates poikilocapnic HVR; McGuire et al., 2008b).

Sleep-wake electroencephalogram (EEG) and electromyogram (EMG) recordings, which were not conducted in the present study, were conducted in our previous study in rats undergoing 24 h SF or LC treatment with the same rotating drums, and the same SF and LC protocols (McGuire et al., 2008b). The analysis of sleep architecture demonstrated that our SF treatment is very similar to other successful forms of experimental SF using periodic, forced locomotion with the same SF protocol, and mimics some important aspects of the clinical SF observed in OSA patients (McGuire et al., 2008b). Although the 24 h SF protocol caused sleep deprivation (the accumulative sleep loss during the entire process was ~3 h, ~25% of total sleep time) and it was difficult to rule out this confounding factor completely, evidence for a SF effect on respiratory control was unequivocal (McGuire et al., 2008b). Since we did not record EEG and EMG signals in the present study and the SF treatment would elevate the homeostatic sleep drive, one may question whether the parameters were indeed measured only during quiet wakefulness. We argue that possible undetected sleep was unlikely to play an important role. First, it is very unusual that rats sleep with eyes open (we followed a very strict rule during measurements, see the methods). Second, even if there were microsleep episodes, which usually last a few seconds or less, they were unlikely to change our results markedly, which were recorded in ~5 min. Finally, had sleep played a role in the attenuation of HCVR, isocapnic HVR should also have been attenuated since HVR is similarly attenuated during sleep (Douglas et al., 1982).

Plasma corticosterone (a stress hormone in rats) was also measured in that previous study (McGuire et al., 2008b) but not in the present study. There was a similar trend towards an elevated corticosterone level after both SF and LC treatments, although both were statistically insignificant due to the fact that the corticosterone level was highly variable among rats (McGuire et al., 2008b). These results suggest that both 24 h SF and LC treatments somewhat cause stress at least in some rats. We argue, however, that the SF-related stress was unlikely to play an essential role in the SF-induced HCVR attenuation in the present study because: (1) mean corticosterone levels are similar (McGuire et al., 2008b) but HCVR results are quite different between SF and LC rats (Figs. 4 and 5); and (2) the SF-attenuated HCVR could be readily reversed by the A1 receptor antagonism with 8-CPT injection (Fig. 4), which has little to do with overall stress. In addition, despite probable increases in plasma corticosterone, 24 h LC treatment had minimal effects on poikilocapnic HVR and ventilatory long-term facilitation in that previous study (McGuire et al., 2008b).

Theoretically, hypercapnic PaCO2 should have been a little higher in SF vs. control rats since the blood samples were drawn during hypercapnea ~1 h after SF, and HCVR and hypercapnic ventilation were suppressed by SF during that time. However, our hypercapnic PaCO2 data showed no significant difference between groups (Table 1). Given that the rat number (n=4) is small and the SF-induced attenuation is also relatively small [although HCVR was markedly attenuated after SF treatment (control: ~173% vs. SF: ~130%), ventilation during hypercapnia was only reduced by ~7%, see Table 3], we believe that the present study was statistically underpowered to detect a difference.

4.2. HVR and HCVR after 24 h SF treatment

In the present study, the resting ventilation was not significantly changed after 24 h SF, which is consistent with our previous study (McGuire et al., 2008b) and other studies with healthy humans (Cooper and Phillips, 1982; White et al., 1983), and neither was body temperature. Although metabolic rate was not measured in the present study, it was measured in our previous study, in which the resting metabolic rate (defined by CO2 production) was not significantly changed after 24 h SF (McGuire et al., 2008b). Thus the SF-induced attenuation of HCVR is unlikely due to changes in the resting ventilation, body temperature or metabolic rate.

In contrast to HCVR, isocapnic HVR was not affected by 24 h SF treatment in the present study. We were a little surprised by the result, since poikilocapnic HVR was significantly decreased after 24 h SF (McGuire et al., 2008b). We are not sure why the SF affects poikilocapnic and isocapnic HVR differently, but it may be related to different PaCO2 levels, as the magnitude of HVR is affected by the PaCO2 level at which HVR is determined (Bisgard and Neubauer, 1995). One major difference in our present and previous studies is whether CO2 level was controlled during hypoxic exposures. In the present study, the PaCO2 level was carefully controlled and there was no significant difference in mean PaCO2 between the resting and hypoxic trials, or before and after SF treatment, while in that previous study, the CO2 level was not controlled and PaCO2 was not measured.

The present results appear to be inconsistent with some published data. It has been reported that two consecutive nights of SF induced by auditory stimuli did not significantly change HCVR in healthy humans (Espinoza et al., 1991). Similarly, 2–3 nights of the auditory stimuli-induced SF also did not impair HCVR in sleeping dogs (Bowes et al., 1980). We noticed, however, that in the above two studies, HCVR was measured several hours after SF. Therefore, it is possible that the SF-attenuated HCVR had recovered when HCVR was measured, as the SF-induced attenuation lasts for only a few hours (Fig. 3). In a long-term canine model of OSA with sleep-triggered tracheal occlusion, which produced ~57 occlusions/h of sleep, a striking reduction in isocapnic HVR but a slight increase in HCVR was observed during wakefulness after ~15 weeks of OSA (Kimoff et al., 1997). However, unlike our SF, that airway occlusion apparatus not only induced SF but also produced intermittent hypercapnia and hypoxia. The other discrepancies also include the animal species (rats vs. dogs) and the duration of treatment (24 h vs. 15 weeks). As 24 h sleep deprivation caused a marked reduction in isocapnic HVR as well as HCVR (Cooper and Phillips, 1982; Schiffman et al., 1983; White et al., 1983), we speculate that a longer SF treatment might possibly cause attenuation of isocapnic HVR in these rats. In that previous study (McGuire et al., 2008b), we found that 6–12 h sleep deprivation was more efficient than SF to cause impairment in ventilatory long-term facilitation.

4.3. Adenosine and A1 receptors

Considerable evidence suggests that endogenous adenosine is a homeostatic sleep factor, which promotes the transition from wakefulness to sleep; extracellular adenosine accumulates selectively in the basal forebrain and cortex during prolonged wakefulness, and declines slowly during recovery sleep (Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 1997). Sleep deprivation and SF also increase adenosine levels in several brain areas (Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 1997; McKenna et al., 2007). Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that adenosine induces its somnogenic effects primarily via inhibiting specific basal forebrain cholinergic neurons that promote wakefulness. This somnogenic effect and the neuronal inhibition can be blocked by adenosine A1 receptor antagonism (Thakkar et al., 2003). There is also evidence suggesting that adenosine promotes sleep by disinhibiting the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) neurons (Chamberlin et al., 2003).

As a ubiquitous neuromodulator, adenosine acts via several membrane receptors (Fredholm, 1995). One of its most prominent actions is inhibition of release of several transmitters from nerve terminals via activation of its pre-synaptic A1 receptors on the terminals. Anatomically, a high density of A1 receptors has been identified in areas that are important for respiratory control, e.g., the hypoglossal nuclei in the brainstem, the ventral horns in the cervical spinal cord where phrenic motoneurons are located (Reppert et al., 1991; Nantwi et al., 2003) and the rostral ventrolateral medulla, an area known to contain the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN, the primary central chemoreceptors; see Mulkey et al., 2004).

The role of adenosine A1 receptors in HCVR has been studied previously. One recent study demonstrated that systemic injection of the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX (4 mg/kg, i.p.) increased HCVR by 60% in awake 20-day-old rats (Montandon et al., 2007). In the present study, however, the injection of 8-CPT (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) had little effect on HCVR in control rats (Fig. 4). It is unclear why the same systemic antagonism of adenosine A1 receptors caused different effects on HCVR in these 2 studies. This discrepancy might be related to differences in age (adults vs. 20 days old), drug (8-CPT vs. DPCPX) and/or hypercapnic level (6% vs. 5% CO2). We believe, however, that the most likely cause for this discrepancy is the different antagonist dose. Although both drugs have high selectivity for A1 over other adenosine receptor subtypes, DPCPX is about 10-fold more potent than 8-CPT on A1 receptors (cf. Daly, 1993). Thus they used a much higher drug dose than ours. In the present study, the dose of 8-CPT was carefully selected as a compromise to minimize the drug effect on the baseline variables and HCVR in control rats, and to achieve the total restoration of HCVR in SF rats. We speculate that HCVR would have been enhanced had the 8-CPT dose been substantially increased. These results also suggest that the SF-induced attenuation of HCVR is more sensitive to the A1 receptor antagonism than HCVR per se.

4.4. Potential mechanism

Our previous study showed that systemic A1 receptor antagonism restored the SF-eliminated ventilatory long-term facilitation and improved the SF-attenuated poikilocapnic HVR (McGuire et al., 2008b). We thus hypothesized that 24 h SF increases extracellular adenosine concentration near major inspiratory (e.g. phrenic, intercostal and hypoglossal) motoneurons, which reduces the serotonin (from the raphe serotonin neuron nerve terminals) and glutamate release (from the premotor neurons) via A1 receptor-mediated pre-synaptic inhibition (Bellingham and Berger, 1994; Dong and Feldman, 1995), thereby eliminating ventilatory long-term facilitation and attenuating poikilocapnic HVR, respectively (McGuire et al., 2008b). However, since this old model emphasizes the SF effect at the motoneuron level (a convergent route for both HVR and HCVR), it is seriously challenged by the present results, which demonstrated that HCVR and (isocapnic) HVR were differentially affected by 24 h SF. Thus, the inspiratory motoneurons might not be the major location (at least not the only major location) where SF affects ventilatory chemoresponsiveness.

One possible alternative location is the RTN. The RTN CO2-sensitive glutamatergic neurons innervate the major components of the respiratory rhythm and pattern generating circuit, including the pre-Bötzinger and ventral respiratory group neurons (Mulkey et al., 2004). We speculate that if SF induces accumulation of adenosine in that area and if there are rich A1 receptors on the RTN neuron nerve terminals, then SF could attenuate HCVR while having little effect on HVR. In addition, since the extracellular adenosine level is gradually increased during sleep deprivation or SF, and this elevated adenosine level appears to decline gradually during several hours of recovery sleep (Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 1997; McKenna et al., 2007), we speculate that the spontaneous recovery of HCVR was due to declines of adenosine levels after SF terminated.

4.5. Implications

The SF-induced attenuation of HCVR, in theory, can affect upper airway patency control in several different ways. Hypercapnic chemoreceptor stimulation is known to decrease upper airway resistance (Badr et al., 1991). Thus SF may undermine the crucial upper airway dilators motor output via attenuating HCVR, thus exacerbating OSA. On the other hand, the decrease in HCVR may reduce the respiratory control system loop gain, thus helping to stabilize respiration and consequently the upper airway (Wellman et al., 2008). Additionally, the decrease in HCVR may also prolong the time to arousal by reducing the chance of respiratory effort-induced arousals (Eikermann et al., 2009), allowing relatively more time for genioglossus and other upper airway dilator muscles to develop and generate more anti-collapse forces, thus alleviating some symptoms. Therefore the overall effect of the SF-attenuated HCVR on the development of respiratory failure in those patients with OSA or with other respiratory disorders is probably a complex interplay between these distinct and often opposing mechanisms, and is also likely to be associated with individual differences.

In conclusion, the 24 h experimental SF, which successfully interrupts sleep continuity up to 30 times per hour, but avoids important changes in total sleep time and intermittent hypoxia and hypercapnia (McGuire et al., 2008b), produced an attenuation of HCVR but caused minimal change in isocapnic HVR in awake, spontaneously breathing rats. This attenuation of HCVR lasts for only a few hours and requires activation of adenosine A1 receptors.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 HL64912. We wish to thank Dr. Nancy L. Chamberlin for her careful critique of the manuscript. Dr. Malhotra is funded by NIH grants K24 HL93218 and P01 HL95491.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Appel S, Mathot RA, Langemeijer MW, IJzerman AP, Danhof M. Modelling of the pharmacodynamic interaction of an A1 adenosine receptor agonist and antagonist in vivo: N6-cyclopentyladenosine and 8-cyclopentyltheophylline. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:1253–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr MS, Skatrud JB, Simon PM, Dempsey JA. Effect of hypercapnia on total pulmonary resistance during wakefulness and during NREM sleep. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:406–414. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.2.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard RD, Tan WC, Kelly PL, Pak J, Pandey R, Martin RJ. Effect of sleep and sleep deprivation on ventilatory response to bronchoconstriction. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:490–497. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellingham MC, Berger AJ. Adenosine suppresses excitatory glutamatergic inputs to rat hypoglossal motoneurons in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1994;177:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgard GE, Neubauer JA. Peripheral and central effects of hypoxia. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bowes G, Woolf GM, Sullivan CE, Phillipson EA. Effect of sleep fragmentation on ventilatory and arousal responses of sleeping dogs to respiratory stimuli. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:899–908. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks D, Horner RL, Kozar LF, Render-Teixeira CL, Phillipson EA. Obstructive sleep apnea as a cause of systemic hypertension. Evidence from a canine model. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:106–109. doi: 10.1172/JCI119120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin NL, Arrigoni E, Chou TC, Scammell TE, Greene RW, Saper CB. Effects of adenosine on gabaergic synaptic inputs to identified ventrolateral preoptic neurons. Neuroscience. 2003;119:913–918. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper KR, Phillips BA. Effect of short-term sleep loss on breathing. J Appl Physiol. 1982;53:855–858. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly JW. Mechanism of action of caffeine. In: Garattini S, editor. Caffeine, Coffee and Health. New York: Raven Press, Ltd; 1993. pp. 97–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dong XW, Feldman JL. Modulation of inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons by presynaptic adenosine A1 receptors. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3458–3467. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03458.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas NJ, White DP, Weil JV, Pickett CK, Martin RJ, Hudgel DW, Zwillich CW. Hypoxic ventilatory response decreases during sleep in normal men. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;125:286–289. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.125.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikermann M, Eckert DJ, Chamberlin NL, Jordan AS, Zaremba S, Smith S, Rosow C, Malhotra A. Effects of pentobarbital on upper airway patency during sleep. Eur Respir J. 2009 Dec 23; doi: 10.1183/09031936.00153809. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 20032012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza H, Thornton AT, Sharp D, Antic R, McEvoy RD. Sleep fragmentation and ventilatory responsiveness to hypercapnia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1121–1124. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faccenda JF, Mackay TW, Boon NA, Douglas NJ. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in the sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:344–348. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2005037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB. Adenosine receptors in the central nervous system. News Physiol Sci. 1995;10:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kimoff RJ, Brooks D, Horner RL, Kozar LF, Render-Teixeira CL, Champagne V, Mayer P, Phillipson EA. Ventilatory and arousal responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia in a canine model of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:886–894. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9610060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancel M, Kerkhof GA. Effects of repeated sleep deprivation in the dark- or light-period on sleep in rats. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:289–297. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie P, Herer P, Hoffstein V. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome as a risk factor for hypertension: population study. Bmj. 2000;320:479–482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire M, Liu C, Cao Y, Ling L. Formation and maintenance of ventilatory long-term facilitation require NMDA but not non-NMDA receptors in awake rats. J Appl Physiol. 2008a;105:942–950. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01274.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire M, Tartar JL, Cao Y, McCarley RW, White DP, Strecker RE, Ling L. Sleep fragmentation impairs ventilatory long-term facilitation via adenosine A1 receptors. J Physiol. 2008b;586:5215–5229. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.158121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna JT, Tartar JL, Ward CP, Thakkar MM, Cordeira JW, McCarley RW, Strecker RE. Sleep fragmentation elevates behavioral, electrographic and neurochemical measures of sleepiness. Neuroscience. 2007;146:1462–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montandon G, Kinkead R, Bairam A. Disruption of adenosinergic modulation of ventilation at rest and during hypercapnia by neonatal caffeine in young rats: role of adenosine A(1) and A(2A) receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1621–R1631. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00514.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey DK, Stornetta RL, Weston MC, Simmons JR, Parker A, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1360–1369. doi: 10.1038/nn1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantwi KD, Basura GJ, Goshgarian HG. Effects of long-term theophylline exposure on recovery of respiratory function and expression of adenosine A1 mRNA in cervical spinal cord hemisected adult rats. Exp Neurol. 2003;182:232–239. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, Shahar E, Samet JM, Redline S, D'Agostino RB, Newman AB, Lebowitz MD, Pickering TG. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. Jama. 2000;283:1829–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porkka-Heiskanen T, Strecker RE, Thakkar M, Bjorkum AA, Greene RW, McCarley RW. Adenosine: a mediator of the sleep-inducing effects of prolonged wakefulness. Science. 1997;276:1265–1268. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Stehle JH, Rivkees SA. Molecular cloning and characterization of a rat A1-adenosine receptor that is widely expressed in brain and spinal cord. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5:1037–1048. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-8-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman PL, Trontell MC, Mazar MF, Edelman NH. Sleep deprivation decreases ventilatory response to CO2 but not load compensation. Chest. 1983;84:695–698. doi: 10.1378/chest.84.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, Lee ET, Newman AB, Javier Nieto F, O'Connor GT, Boland LL, Schwartz JE, Samet JM. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:19–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler CM, Shea SA. Sleep deprivation per se does not decrease the hypercapnic ventilatory response in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1124–1128. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9906026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar MM, Winston S, McCarley RW. A1 receptor and adenosinergic homeostatic regulation of sleep-wakefulness: effects of antisense to the A1 receptor in the cholinergic basal forebrain. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4278–4287. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04278.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman A, Malhotra A, Jordan AS, Stevenson KE, Gautam S, White DP. Effect of oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea: role of loop gain. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;162:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DP, Douglas NJ, Pickett CK, Zwillich CW, Weil JV. Sleep deprivation and the control of ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:984–986. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand L, Zwillich CW. Obstructive sleep apnea. Dis Mon. 1994;40:197–252. doi: 10.1016/0011-5029(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]