Abstract

Mutations in the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) gene are the most prevalent known cause of autosomal dominant Parkinson's disease (PD). The LRRK2 gene encodes a Roco protein featuring a ROC GTPase and a kinase domain linked by the C-terminal of ROC (COR) domain. Here, we explored the effects of the Y1699C pathogenic LRRK2 mutation in the COR domain on GTPase activity and interactions within the catalytic core of LRRK2. We observed a decrease in GTPase activity for LRRK2 Y1699C comparable to the decrease observed for the R1441C pathogenic mutant and the T1348N dysfunctional mutant. To study the underlying mechanism, we explored the dimerization in the catalytic core of LRRK2. ROC-COR dimerization was significantly weakened by the Y1699C or R1441C/G mutation. Using a competition assay we demonstrated that the intra-molecular ROC:COR interaction is favoured over ROC:ROC dimerization. Interestingly, the intra-molecular ROC:COR interaction was strengthened by the Y1699C mutation. This is supported by a 3D homology model of the ROC-COR tandem of LRRK2, showing that Y1699 is positioned at the intra-molecular ROC:COR interface. In conclusion, our data provides mechanistic insight into the mode of action of the Y1699C LRRK2 mutant: the Y1699C substitution, situated at the intra-molecular ROC:COR interface, strengthens the intra-molecular ROC:COR interaction, thereby locally weakening the dimerization of LRRK2 at the ROC-COR tandem domain resulting in decreased GTPase activity.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, leucine rich repeat kinase 2, GTPase, dimerization

INTRODUCTION

To date, the most prevalent known cause of Parkinson's disease are mutations in the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) gene, accounting up to 30% of all PD cases depending on ethnicity (Biskup & West 2009). Although over 45 mutations have been reported in the LRRK2 gene, thus far only six (R1441C/G/H, Y1699C, G2019S, I2020T) have been proven to segregate with autosomal dominant PD (Haugarvoll & Wszolek 2006, Gasser 2006, Healy et al. 2008, Greggio & Cookson 2009). Since the clinical and neuropathological manifestations of LRRK2 PD are mostly indistinguishable from those observed in sporadic cases of the disease, insight into the function of LRRK2 is very valuable in the study of the molecular pathogeneses of PD (Brice 2005).

The LRRK2 gene encodes a complex protein (2527 amino acids) that consists of several predicted domains. From the N- to the C-terminus, the protein contains LRRK2 specific repeats, a leucine rich repeat (LRR) region, a catalytic core, featuring a functional ROC (Ras Of Complex proteins) GTPase domain and a kinase domain linked by the C-terminal of ROC (COR), followed by a C-terminal WD40 domain (Mata et al. 2006). The presence of the ROC-COR bidomain in LRRK2 classifies the protein as a Roco family member (Bosgraaf & Van Haastert 2003). To date, much effort has been invested into the study of both the kinase and GTPase functionalities of LRRK2, their regulatory interplay and the effects of pathogenic mutations on these properties. On the other hand, the implications of the Y1699C substitution in the COR domain have not been studied in much detail and the function of the COR domain remains largely unknown.

It has been shown that LRRK2 possesses both auto-phosphorylation activity and phosphorylation activity towards generic substrates and that these activities are increased in the G2019S pathogenic mutant of LRRK2 in several in vitro assays. However there is still some controversy on the precise effects of other prevalent LRRK2 mutations, including Y1699C, on kinase activity (reviewed in Greggio & Cookson 2009). LRRK2 can bind GTP/GDP through its ROC domain (Smith et al. 2006, Guo et al. 2007, West et al. 2007, Lewis et al. 2007, Ito et al. 2007, Li et al. 2007) and also possesses weak GTPase activity (Guo et al. 2007, Lewis et al. 2007, Li et al. 2007). Several studies have been conducted on the effect of pathogenic ROC mutations (R1441C/G) on GTP-binding and GTPase activity of both full-length LRRK2 and the isolated ROC domain. All agree on the fact that these mutants cause a reduction in GTPase activity (Guo et al. 2007, Lewis et al. 2007, Xiong et al. 2010, Deng et al. 2008) with no or minor effects on steady state GTP-binding capacity (Guo et al. 2007, Lewis et al. 2007, Li et al. 2007, West et al. 2007, Xiong et al. 2010). So far effects of other mutants on GTPase activity have yet to be investigated in depth.

LRRK2 has been shown to self interact (Gloeckner et al. 2006, Dachsel et al. 2007) and a considerable fraction of the protein has been found to exist as a dimer (Greggio et al. 2008, Klein et al. 2009, Sen et al. 2009). Part of the self-interaction of LRRK2 is mediated through interactions involving the ROC domain (Greggio et al. 2008). Although the isolated human LRRK2 ROC domain self interacts in pulldown assays (Li et al. 2009) and can crystallize as a dimer (Deng et al. 2008), it has become clear that LRRK2 dimerization also involves other interactions. For instance, the ROC domain also interacts with other fragments of the protein, including the N-terminus, the LRR and WD40 domains (Greggio et al. 2008, Klein et al. 2009). In accordance with these findings, it has been shown that the ROC-COR bidomain is critically though not exclusively involved in LRRK2 dimerization (Klein et al. 2009). Finally, a potential function of the COR domain as a dimerization device has recently been suggested based on the structure of the COR domain in the LRRK2 homolog of the prokaryote C. tepidum (Gotthardt et al. 2008). Therefore, although several independent lines of evidence suggest a dimeric protein, the exact nature of the interactions that stabilize a dimer in full-length LRRK2 are still uncertain.

For many protein kinases, dimerization is a prerequisite for catalytic activity. In the case of LRRK2, there also seems to be a functional relation between dimerization and kinase activity (Greggio et al. 2008, Sen et al. 2009). The pathogenic mutants in the ROC (R1441C/G/H) and COR (Y1699C) domains have been linked to alterations of the dimerization properties. In the context of the isolated ROC-COR bidomain (Roco fragment), all 4 mutants have been shown to reduce self interaction in comparison with the wt fragment (Klein et al. 2009). Moreover, these Roco fragments have been shown to exert an inhibitory effect on the kinase activity of the full-length protein (both wt and G2019S). Next to the putative regulation of kinase activity by dimerization, it has been proposed, based on the behavior of the C. tepidum Roco protein, that GTPase activity of this class of proteins depends on dimer formation (Gasper et al. 2009).

In the present study, we have extensively investigated the effects of the Y1699C pathogenic mutation in the COR domain on GTPase activity, ROC-COR dimerization as well as interactions in the catalytic core of LRRK2. Our data allow us to propose a mechanism whereby Y1699C strengthens intra-molecular catalytic core interactions which alter the inter-molecular dimerization of ROC-COR ultimately leading to altered GTPase activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Homology Modeling

MODELLER 9v6 (Fiser & Sali 2003) was used to generate homology models. Target-template alignments were manually adapted from the mGenTHREADER method for fold recognition (Jones 1999), accessible from the PSIPRED Protein Structure Prediction Server (Bryson et al. 2005). Idealization of bond geometry and removal of unfavourable non-bonded contacts was performed by energy minimization with the BRUGEL software package (Delhaise et al. 1988). The dead-end elimination method (Desmet et al. 1992) was used to optimize the orientation of the side-chains. Visualization and least square fitting were done with PyMOL (DeLano 2002).

Constructs

All 3xflag-tagged constructs of LRRK2 or LRRK2 fragments were cloned into pCHMWS plasmid, an in house eukaryotic expression plasmid derived from multiple modifications of a pHR' plasmid (Baekelandt et al. 2002). First, a 3xflag-tag adaptor containing an N-terminal start codon and a C-terminal unique BamHI site in frame with the flag peptide sequence was inserted into the plasmid's multiple cloning site, generating a pCHMWS-3flag-MCS backbone plasmid. Full-length LRRK2 constructs were cloned into this plasmid by making use of the unique XbaI located at position 3734 of the human LRRK2 coding sequence (Genbank accession number NM_198578). An N-terminal LRRK2 fragment was amplified by PCR using a BamHI extended 5' primer at the start of the coding sequence and a 3' primer overlapping with the XbaI site (to position 3744). This fragment was cloned into pCHMWS-3flag-MCS at the BamHI and XbaI sites. The C-terminal fragment (position 3734 to end) was excised from cDNA constructs encoding LRRK2 (generous gift of Dr. G. Ito and Dr. T. Iwatsubo (Ito et al. 2007)) using XbaI and cloned into the pCHMWS plasmid containing the N-terminal part of LRRK2 to yield the pCHMWS-3flag-LRRK2 construct. For mutant Y1699C, a wild type version of the C-terminal fragment was first inserted into the XbaI site of pBluescript-KS-II plasmid. Using this plasmid, the mutation was generated via a double PCR based protocol (Kirsch & Joly 1998), and the mutated sequence was then transferred to the pCHMWS plasmid as described above. Constructs of shorter LRRK2 fragments were generated by insertion of PCR amplified cDNA (using 5' primers extended with a BamHI site and a start ATG and 3' primers extended with a stop codon (TGA) and NheI site, and abovementioned cDNA of LRRK2 as template). Fragment delimitations are as follows: ROC 1335–1548, COR 1550–1880, kinase 1880–2138, COR-kinase 1550–2138, ROC-COR-kinase 1335–2138, ROC-COR-kinase-WD40 1335–2527. Sequences were confirmed as the reference sequence of LRRK2 protein (Genbank NM_198578) on both strands using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit version 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the ABI Prism 3700 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Myc-tagged ROC domain, ROC-COR-kinase fragments and LRRK2 constructs were previously described (Greggio et al. 2008).

For the yeast two-hybrid (YTH) assays, LRRK2 ROC, COR and ROC-COR tandem domain cDNAs were amplified from human whole brain first-strand cDNA (Clontech) using Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and cloned into the YTH bait vector pDS-BAIT (pDS; Dualsystems Biotech) or the prey vector pACT2 (Clontech). Cloning resulted in an in-frame fusion of the LexA DNA binding domain (LexA-BD; vector pDS, DualSystems) or GAL4 activation domain (GALAD; vector pACT2, Clontech) epitope tags to the N-termini of all expressed proteins. Mutations were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum at 37°C and 5% CO2. Transient expression was performed by transfecting plasmids with linear polyethylenimine (Polysciences Europe GmbH, Eppelheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol for 48 h.

Co-immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells were transfected with 3xmyc-tagged ROCwt, 3xflag-tagged COR (wt or Y1699C) or 3xflag-tagged COR-kinase (wt or Y1699C) and lysed in co-IP buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (Sigma-Aldrich)). Lysates were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 20000g. Afterwards, lysates containing 3xmyc-tagged ROC were mixed with those containing 3xflag-tagged COR or 3xflag-tagged COR-kinase for one hour at 4°C. Anti-Myc agarose beads were added and these Co-IP reactions were incubated overnight at 4°C (Invitrogen). After four washes, immunoprecipitates were eluted by addition of SDS sample buffer and boiling and analysed by western blotting with anti-Myc antibodies (9E10, Roche) and anti-Flag (M2, Sigma) antibodies.

GST pulldown

HEK293T cells were transfected with 3xflag-tagged LRRK2 fragments and lysed in pulldown buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (Sigma-Aldrich)). Lysates were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 20000 g. Glutathione sepharose beads were loaded with GST-ROC, purified from E. coli, for 2 hours at 4°C. Afterwards beads were washed with pulldown buffer and incubated with an excess of total cell lysates overnight at 4°C. After three washes with pulldown buffer, co-purified proteins were analyzed by western blotting with anti-Myc (9E10, Roche), anti-Flag (M2, Sigma) or anti-GST antibodies. Blot signal was acquired in the linear range, using a cooled CCD camera (Fujifilm Las-3000, Tokyo, Japan). Densitometric analysis of the immunoreactivity bands was performed using Aida analyzer v1.0.

Nucleotide loading

Depending on the experimental conditions, lysates containing 3xmyc-tagged ROC or glutation sepharose beads loaded with GST-ROC were pretreated with 10mM Na2EDTA alone or combined with GDP or GTPγS in a final concentration of 1 mM and 0.1 mM respectively for 30 min at 37°C (Benard et al. 1999, Knaus et al. 1992). Nucleotide exchange was stopped by adding MgCl2 to a final concentration of 20 mM.

Competition assay

HEK293T cells were transfected with 3xflag-tagged ROC or 3xflag-tagged COR fragments, lysed in pulldown buffer and centrifuged as above. Glutathione sepharose beads were loaded with GST-ROC, purified from E. coli, for 2 hours at 4°C. Afterwards beads were washed with pulldown buffer and incubated with cell lysate containing 3xflag-ROC (dilution factor 1/2) for 2 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed 3 times, a sample was taken and a concentration range (dilution factor 1, 1/2, 1/10, 1/20) of cell lysate containing 3xflag-COR was added. Following incubation during 2 hours at 4°C, beads were washed three times before elution with SDS sample buffer. Co-purified proteins were analysed by western blotting as described under GST pulldown.

GTPase assay

HEK293T cells were transfected with 3xflag-tagged LRRK2, ROC-COR-kinase-WD40, ROC-COR-kinase, ROC-COR or ROC and lysed after 48–72 hours in GTPase lysis buffer (20 mM Tris/HC pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% Glycerol, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (Sigma-Aldrich)). Proteins were purified as described above, the protein bound beads were rinsed in GTPase buffer (20 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.02% Triton X-100) and proteins were eluted from beads with 3xflag peptide (Sigma) in GTPase buffer according to manufacturer's instructions. The purity of the purified proteins was assessed by Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE gel. GTPase activity was assayed using coupled enzymes pyruvate kinase (EC 2.7.1.40) and lactate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.27) in the presence of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and NADH (Margalit et al. 2004). GTPase assays were performed using 40–80 nM LRRK2 protein in GTPase buffer containing 20 U/ml pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase (Sigma), 600 μM NADH, 1 mM PEP and 500 μM GTP in a final volume of 200 μl. Reaction mixes were equilibrated to 30°C for 10 min before initiating the reactions by the addition of GTP and thorough mixing of the contents. Depletion of NADH was measured by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm over 60 min (one measurement every 5 min) using an Envision multi-well plate reader (Perkin Elmer). Functionality of the assay was confirmed for each run using the GTPase Gαo from the heterotrimeric G protein family as a control (generous gift of Dr. D. Siderovski, University of North Carolina, NC, USA, protein prepared as described in (Willard et al. 2005)). GTPase activity was confirmed in two independent experiments and results are depicted as the change in absorbance at 340 nm as a function of time.

GTP binding assay

HEK293T cells were transfected with 3xflag-tagged LRRK2 wt, T1348N, Y1699C or 3xflag-tagged ROC wt or T1348N. The GTP binding assay was performed as described in (Korr et al. 2006). Briefly, HEK293T cells were lysed in lysis buffer G (100 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 50mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) for 10 min on ice, and lysates were centrifuged at 20000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatants containing 100 μg protein each were incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with 30 μl of GTP-sepharose bead suspension (Jean Bioscnience GmbH, Jena, Germany) that was pre-treated with 100 μg/ml BSA in 1× Roti®-Block (Carl Roth GmbH) for 1 h at 4°C. Afterwards, nucleotides, i.e. GTP, GDP, ATP or CTP (all Sigma), were added to a final concentration of 2 mM, and the incubation was continued for another 60 min at 4°C. Samples were loaded onto 0.65 μm microcentrifuge filter units (Millipore), washed three times with 500 μl lysis buffer G, and bound protein was eluted by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heating for 10 min at 72°C. Proteins were analysed by western blotting as previously described.

Statistics

For co-IP and pulldown assays, values were corrected for IP and pulldown respectively and not for inputs since an excessive amount of target protein was still present in the sample after incubation. These values were then normalized to wild type and tested for significant differences with the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was set at the p<0.05.

Yeast two-hybrid assays

The yeast strain L40 (Invitrogen) was co-transformed with wt or mutant pDS-LRRK2 ROC, COR and ROC-COR tandem domain bait constructs together with wt or mutant pACT2-LRRK2 ROC, COR and ROC-COR tandem domain prey constructs. Transformations were plated on selective dropout media lacking either leucine, tryptophan and histidine supplemented with 0.5 mM 3-AT (for suppression of `leaky' histidine expression) for nutritional selection, or leucine and tryptophan for transformation controls. After incubation at 30°C for 3–6 days to allow prototropic colonies to emerge, LacZ reporter gene assays were performed as previously described (Harvey et al. 2004).

Quantitative yeast two-hybrid assays

Quantitative yeast assays were performed as described previously (Sancho et al. 2009). Briefly cell pellets were resuspended in Z-buffer containing 40mM β-mercaptoethanol followed by lysis in 0.1% (w/v) SDS and 0.1% (v/v) chloroform. All protein interactions were assayed in four independent experiments in triplicate. After addition of CPRG (chloropheno-red-β-D-galactopyranoside) the color change was recorded at 540 nm and readings were adjusted for turbidity of the yeast suspension at 620 nm. The background signal (co-transfected pACT2 negative control) was subtracted from each co-transformation reading and values were normalised to the wild-type LRRK2 response, which was set at 100%. Statistically significant differences in the interaction strength of two proteins were determined using a Student's two-tailed t-test.

RESULTS

Effect of pathogenic mutations in the ROC and COR domains on LRRK2 GTPase activity

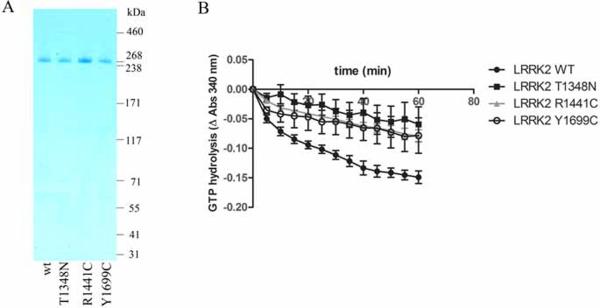

We first examined the impact of pathogenic mutations in the ROC (R1441C) and COR (Y1699C) domains on LRRK2 GTPase activity. Therefore, we used an enzyme coupled steady state GTPase assay and purified protein in solution. Proteins prepared in this way showed purity of >90% as shown in the Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 1A). For full-length protein we observed weak GTPase activity for wild type while activity measured for the Y1699C mutant was indistinguishable from background activity of the dysfunctional T1348N mutant (Fig. 1B). The same pattern of lower GTPase activity was observed for the R1441C mutant (Fig. 1B), confirming previous findings based on isotopic GTPase assays (Lewis et al. 2007, Guo et al. 2007). Finally, The GTPase activity of the full-length protein was compared to that of the shorter fragments including fragments containing the ROC domain such as the ROC-COR fragment (RC), the catalytic core fragment ROC-COR-Kinase (RCK) and a ROC to end fragment (RCKW) which is generally considered the minimal fragment for kinase activity. These 3xflag-tagged LRRK2 fragments, both wild type and negative control mutants (T1348N mutation which abolishes GTP binding), were prepared in the same way as the 3xflag-tagged full-length proteins for the GTPase assays (as given in materials and methods and supplementary Fig. 1). We found that purification of these fragments yielded proteins at comparable concentration to the full-length proteins, however with lower purity (supplementary Fig. 1 A & B). When submitted to the enzyme coupled GTPase assay, these proteins displayed background levels of activity (supplementary Fig. 1C). The finding that the 3xflag-ROC protein binds efficiently to GTP (supplementary Fig. 1D) suggests that this is not due to improper folding of the protein. While it is not excluded that the ROC fragments may possess GTPase activity at higher concentrations, these findings nevertheless show that GTPase activity is higher in the full-length protein compared to ROC or multidomain fragments containing ROC.

Fig 1.

GTPase activity of LRRK2. LRRK2 full-length proteins (WT, T1348N, R1441C, Y1699C) were affinity purified as described in materials and methods. Following elution from the affinity resin, purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE gel and Coomassie staining. These proteins were tested for GTPase activity via an enzyme coupled assay using GTP as a substrate. Plotted are changes in GTP levels as reflected by changes in absorption at 340 nm in function of time. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n=3).

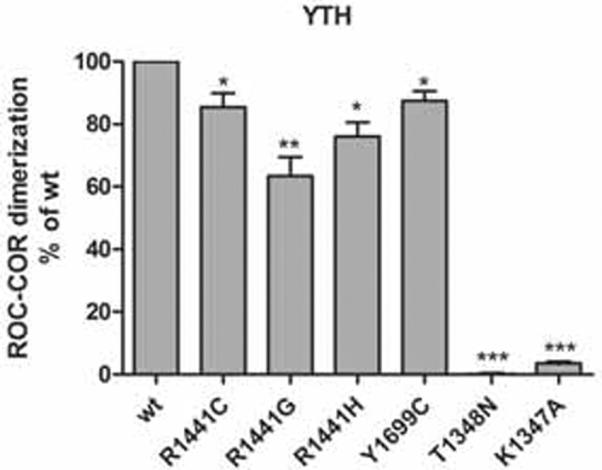

Pathogenic mutations in the ROC and COR domains weaken ROC-COR dimerization

It has been shown that dimerization is a prerequisite for GTPase activity for several G-proteins, including the prokaryotic C. tepidum Roco homolog of LRRK2 (Gotthardt et al. 2008, Gasper et al. 2009). In analogy, we wondered whether the observed reduction in LRRK2 GTPase activity by the Y1699C and R1441C pathogenic mutants could be related to an alteration of the local dimerization properties of LRRK2. Therefore, we assessed whether selected ROC-COR mutations (R1441C, R1441G, R1441H, Y1699C) have an influence on LRRK2 ROC-COR dimerization, using YTH assays. Differences in interaction strength were indicated by the difference in the intensity of the color change assessed by semiquantitative LacZ freeze-fracture (supplementary Fig. 2) and quantitative liquid assays. In these assays, all mutants weakened ROC-COR dimerization (Fig. 2). Moreover, introduction of the GTP-binding deficient mutants T1348N and K1347A led to a dramatic reduction in ROC-COR dimerization.

Fig 2.

Effect of pathogenic mutations on LRRK2 ROC-COR dimerization. Quantitative liquid YTH assays using CPRG (Chlorophenol-red-β-D-galactopyranoside) as substrate for β-galactosidase expression, reveal that the substitutions R1441C/G/H, Y1699C, T1348N and K1347A disrupt ROC-COR dimerization. Statistical significance was determined using a Student's t-test (two-tailed). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n=4). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

The ROC:COR interaction is favoured over the ROC-ROC dimerization

Since the above observations support a causal relation between ROC-COR dimerization and LRRK2 GTPase activity, we investigated the interactions in the catalytic core of LRRK2 in more detail.

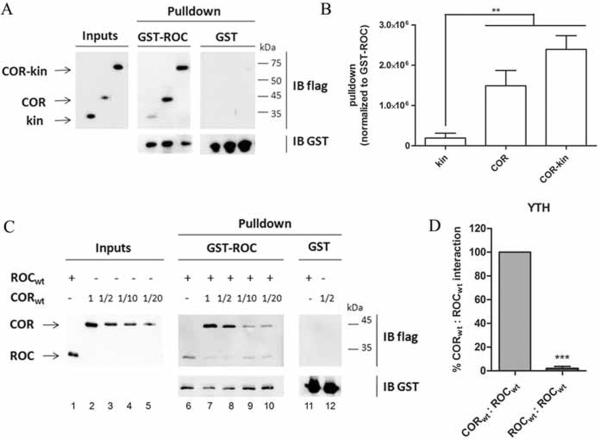

We first addressed the possible interactions between the ROC, COR and kinase domains. For this, we used GST pulldowns of different catalytic core fragments of LRRK2 with GST-ROC as bait. The stability of all protein fragments used, was confirmed under the employed conditions. Each of the COR, kinase and COR-kinase fragments could be pulled down with GST-ROC (Fig. 3A). The interaction between ROC and COR tended to be strengthened by inclusion of the kinase domain (Fig. 3B). However the kinase domain alone showed only very weak interaction with ROC, consistent with previous data (Greggio et al. 2008). These results show that the interaction between ROC and COR is stronger than the interaction between ROC and kinase, suggesting a prominent role of the ROC and COR domains in the internal organisation of the catalytic core. The kinase domain on the other hand seems to fulfil a stabilizing function on the ROC:COR interaction although without firmly interacting with the ROC domain.

Fig 3.

Interactions in the catalytic core of LRRK2 and competition assay between ROC and COR. A, GST pulldowns of 3xflag-COR, 3xflag-kin and 3xflag-COR-kinase transfected in HEK293T cells with GST-ROC as a bait. The left panel shows inputs, the central panel represents GST-ROC pulldowns, and the right panel represents GST pulldowns. Membranes were probed with Flag (M2; upper panels) and GST (bottom panels) antibodies. Recombinant ROC was expressed in E. coli as GST fusion protein and purified by glutathione affinity chromatography. Kin, kinase; IB, immunoblot. B, quantification shows that GST-ROC pulldown is slightly increased when the COR domain is expanded with the kinase domain. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n=5). C, Competition between the ROC:ROC interaction and the ROC:COR interaction was performed as described in materials and methods. Lane 1: input of 3xflag-ROC; lane 2–5 dilution series of input of 3xflag-COR. Lane 6 shows pulldown of 3xflag-ROC with GST-ROC. Lane 7–10: after addition of a concentration range of 3xflag-COR to the ROC pulldown sample (lane 6), 3xflag-ROC was eluted from GST-ROC while 3xflag-COR bound to GST-ROC in a concentration dependent way. D, Quantitative liquid YTH assays using CPRG (Chlorophenol-red-β-D-galactopyranoside) as substrate for β-galactosidase expression. The observed ROC:COR domain interaction is stronger than the interaction between two ROC domains. ROC dimerization was almost undetectable in this yeast assay. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n=4). ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Previous data suggest that ROC:ROC domain interactions occur, as well as ROC:COR interactions (Deng et al. 2008, Greggio et al. 2008). In order to determine the relative importance of these two interactions, we performed a competition assay. Using GST-ROC as bait we could pull down ROC. However, after addition of a concentration range of COR to the sample, the ROC:ROC interaction was outcompeted in a concentration dependent manner by the ROC:COR interaction (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the ROC:COR interaction could not be outcompeted by addition of ROC (supplementary Fig. 3). The difference in interaction strength between the ROC and COR domain and two ROC domains was also demonstrated using YTH assays: semiquantitative LacZ freeze-fracture (supplementary Fig. 2) and quantitative liquid assays (Fig. 3D). In these experiments, a stronger signal for the interaction between the ROC and COR domain than between two ROC domains was observed, the latter interaction being almost undetectable (Fig.3D). These results suggest that while ROC:ROC dimerization may occur for LRRK2, the ROC:COR interaction is stronger.

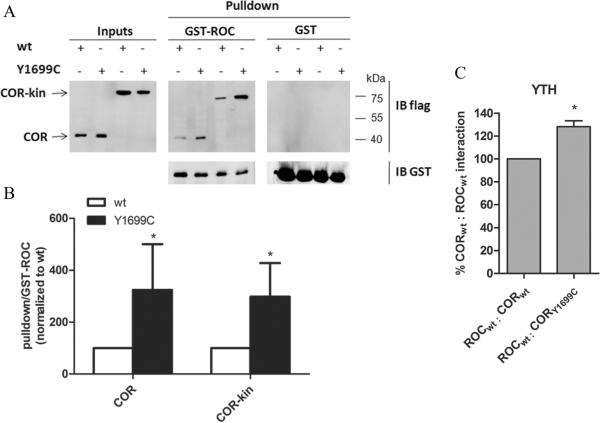

The Y1699C mutation strengthens the ROC:COR interaction

In a next step, we wanted to explore the mechanism underlying the alteration of ROC-COR dimerization, caused by the Y1699C mutation. Since the Y1699 residue is situated in the COR domain, we tested whether substitution of this residue might alter the ROC-COR dimerization through influencing the interaction between the ROC and COR domains. As shown in Fig. 4A and 4B the interaction between ROC and COR was significantly stabilized by the Y1699C mutation in the COR domain. This stabilizing effect of the Y1699C mutation was preserved when the COR domain was expanded with the kinase domain (Fig. 4A, B). These findings were confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation experiments (supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Effect of Y1699C pathogenic mutant on the interaction between ROC and COR or COR-kinase. A, GST pulldowns of 3xflag-COR (wt and Y1699C) and 3xflag-COR-kin (wt and Y1699C) transfected in HEK293T cells with GST-ROC as a bait. The left panel shows inputs, the central panel represents GST-ROC pulldowns, and the right panel represents GST pulldowns. Membranes were probed with Flag (M2; upper panels) and GST (bottom panels) antibodies. B, quantification shows that GST-ROC pulldown of COR and COR-kinase respectively is significantly increased upon the introduction of the Y1699C mutation into the COR domain. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n=4). C, Quantitative liquid YTH assays using CPRG (Chlorophenol-red-β-D-galactopyranoside) as substrate for β-galactosidase expression. Quantification of the interaction between a COR bait harboring the Y1699C mutation and a ROC prey showed a strengthened interaction. Statistical significance was determined using a Student's t-test (two-tailed). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n=4). * p<0.05.

Finally we used YTH assays as an alternative method to assess the ROC:COR interactions. The experiments showed a strengthening of the interaction between the COR bait harboring the Y1699C mutation and the ROC prey in comparison with the interaction of two wild-type proteins (Fig. 4C). Quantification of the interaction between COR baits and ROC preys confirmed the strengthening of the interaction through introduction of the Y1699C mutation by ~30%.

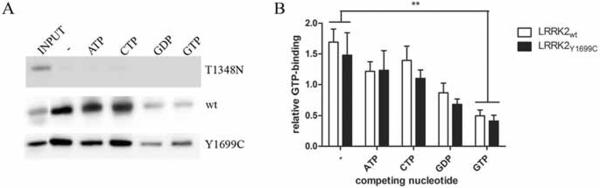

Effect of guanine nucleotide binding on the ROC:COR interaction

Our experimental data strongly suggest a causal link between the weakened ROC-COR dimerization, caused by the strengthening of the ROC:COR interaction, and a decrease in LRRK2 GTPase activity due to Y1699C mutation in the COR domain. However it cannot be excluded that the Y1699C mutation decreases GTPase activity by reducing the affinity for GTP of the full-length protein. Therefore, we conducted a GTP-binding assay on total cell extracts of HEK293T cells, previously transfected with 3xflag-tagged LRRK2 wt or Y1699C. The proportion of GTP bound LRRK2 was determined in the absence and presence of the competing nucleotides ATP, CTP, GDP or GTP (Fig. 5A). No significant differences in the GTP-binding affinity or specificity were observed between LRRK2wt and LRRK2Y1699C (Fig. 5B).

Fig 5.

Effect of Y1699C mutation on LRRK2 GTP binding capacity. A, Flag M2 immuno blot indicating input and GTP-bound LRRK2 levels in the absence (−) or presence of competing nucleotides (ATP, CTP, GDP, GTP). B, quantification of the GTP binding assay in A. GTP-bound LRRK2 levels were normalized to corresponding input levels. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n=6). ** p<0.01.

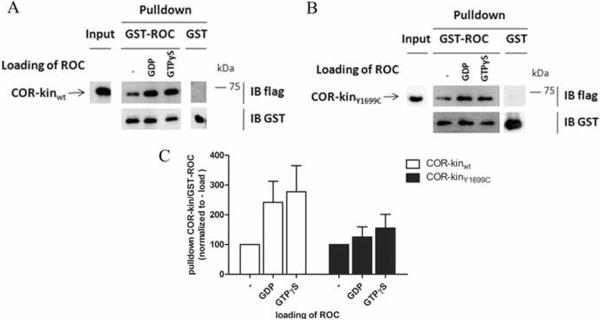

In a next step, we considered whether GDP or GTP binding to the ROC domain might in turn affect the ROC:COR interaction. Before GST pulldowns were performed, GST-ROC was subjected to a loading procedure with GDP, GTPγS or without nucleotides. In all conditions of loading of the ROC, there was pulldown of COR-kinasewt (Fig. 6A) and COR-kinaseY1699C (Fig. 6B). For both constructs, we observed a stabilization of the interaction between ROC and COR-kinase when ROC was in a loaded state, irrespective of the nucleotide (GDP or GTPγS) used. This trend was most pronounced for the ROC to COR-kinasewt interaction (Fig. 6C). The above data suggests, as previously proposed for the C. tepidum, that the ROC:COR interaction is modestly influenced by the presence of guanine nucleotides in the ROC domain.

Fig 6.

Effect of the activation status of ROC on the interaction between ROC and COR-kinase. A, B, GST pulldowns of 3xflag-COR-kinase wt and Y1699C respectively, transfected into HEK293T cells with GST-ROC, subjected to a loading procedure with GDP, GTPγS or without nucleotides, as a bait. The left panel shows input, the central panel represents GST-ROC pulldowns, and the right panel represents GST pulldowns. Membranes were probed with Flag (M2; upper panels) and GST (bottom panels) antibodies. C, Quantification of interactions in A and B. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n=5).

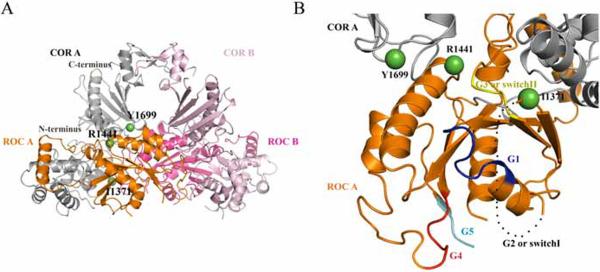

3D-homology model of LRRK2 ROC-COR tandem places Y1699 residue in the intra-molecular ROC:COR interface

To gain better structural insight into the ROC:COR interface and the positioning of the Y1699 residue, we generated a homology model for the ROC-COR domain tandem of human LRRK2 based on the ROC-COR domain tandem of the Roco protein of C. tepidum (PDB-code: 3DPU) (Gotthardt et al. 2008). The second ROC domain, namely ROC B, was modelled into the structure by positioning it analogously to ROC A. The sequence identity between target and template was around 18 % (supplementary Fig. 5). In this model of the LRRK2 ROC-COR tandem the pathogenic mutation Y1699C in the LRRK2 COR domain, is situated on the intra-molecular ROC:COR interface (Fig. 7A, B). The model also places the R1441 residue, a LRRK2 mutational `hot spot', in the same hydrophobic ROC:COR interaction area, near the Switch II loop. This loop, situated at the N-terminus of helix α2, links the Mg2+ binding site with the γ-phosphate of GTP. When comparing the wt homology model after fit on the Y1699C homology model, no large structural changes were seen, especially around amino acid 1699 which remains locked at the ROC:COR interface. This can be explained by the fact that residue 1699 is situated between two proline residues that keep the backbone rather rigid. The closest cysteine to residue 1699 is more than 20 Å away excluding the formation of a disulfide bond between the Y1699C mutant and a cysteine in ROC in this model (data not shown).

Fig 7.

Dimeric ROC-COR domain tandem of human LRRK2 and location of pathogenic mutations at the ROC-COR interface. A, Cartoon representation of the ROC and COR domains of the A and B subunits, of the dimeric ROC-COR domain tandem of human LRRK2. Two ROC-COR bidomains dimerize in a back to back conformation while the ROC:COR interface, containing PD-linked residues, is formed intra-molecularly and is located opposite to the dimer interface. Colour code: ROC A, orange; COR A, grey; ROC B, dark pink and COR B, light pink. I1371, R1441 and Y1699 of subunit A are shown as green labelled spheres. B, Close-up of the ROC-COR interface with indication of residues R1441, Y1699, I1371 as green spheres. The five polypeptide loops that form the nucleotide-binding site are color coded (G1 or P-loop: dark blue, proposed G2 or Switch I loop: black dotted line, G3 or Switch II loop: yellow, G4: red and G5: light blue).

DISCUSSION

The LRRK2 gene encodes a complex Roco protein, harboring both a kinase domain and a Ras-like GTPase domain termed, ROC (Mata et al. 2006). Although the pathogenic PD-linked mutations, described to date, are situated in the ROC (R1441C/G/H), COR (Y1699C) and kinase (G2019S, I2020T) domains, only these in the ROC and kinase domains have been studied extensively while the Y1699C substitution has stayed out of the limelight. Therefore, in this study, we explored the effects of the Y1699C pathogenic mutation on LRRK2 GTPase activity and catalytic core interactions. To this end, we have made use of single LRRK2 domains and bidomains to get an insight into the structural organisation of the protein.

Dimerization is a common regulatory theme among many protein kinases, e.g. receptor interacting protein kinases and MLK3 (Leung & Lassam 1998), which is considered a phylogenetic neighbour of LRRK2 (West et al. 2007). In analogy, LRRK2 has been shown to self interact (Gloeckner et al. 2006, Dachsel et al. 2007) and a considerable fraction of the protein has been found to exist as a dimer (Greggio et al. 2008, Klein et al. 2009, Sen et al. 2009). Moreover, evidence suggests a functional relation between LRRK2 dimerization and kinase activity. Kinase inactive mutants redistribute to higher order oligomers (Greggio et al. 2008, Sen et al. 2009) and the LRRK2 dimer fraction seems to be the most active one in terms of auto-phosphorylation and MBP phosphorylation, in comparison with the higher order oligomers (Sen et al. 2009, Anand et al. 2009). Next to the putative regulation of kinase activity by dimerization, it has been proposed, based on the behavior of the C. tepidum Roco protein, that GTPase activity of this class of proteins depends on dimer formation (Gotthardt et al. 2008, Gasper et al. 2009).

Using low concentrations (50 nM range) of purified LRRK2 recombinant protein in solution, we could measure low GTPase activity of LRRK2 and found that this activity was decreased to background levels in the Y1699C mutant. These results are consistent with the impaired GTPase activity observed in C. tepidum Roco when mutated at the residue equivalent to Y1699C (Gotthardt et al. 2008). The same effect of lowering GTPase activity was seen for LRRK2R1441C, as has been reported previously by several groups (Lewis et al. 2007, Guo et al. 2007, Xiong et al. 2010).

Based on the hypothesis that dimerization is important in the regulation of LRRK2 GTPase activity, we might expect a weakened dimeric protein to be less active as a GTPase. Our results show indeed that the observed reduction in LRRK2 GTPase activity, caused by the R1441C and Y1699C mutations, correlates with a weakening of the local ROC-COR dimerization for both mutants. A weakening effect of the Y1699C and R1441C/G/H mutations on ROC-COR dimerization has also recently been shown by Klein et al.(Klein et al. 2009). However, it should be noted that the effects of the R1441C and Y1699C substitutions on dimerization are local to the catalytic core since no alterations in dimerizing properties of the full-length protein have been observed for either of these mutants (Sen et al. 2009, Klein et al. 2009). This might be explained by the observation that the self interaction of LRRK2 is also mediated by interactions involving the N-terminal region and the LRR and WD40 domains (Greggio et al. 2008, Klein et al. 2009).

Our observations support the contention that dimerization of LRRK2 is important in the regulation of its GTPase activity. It has been shown previously that the ROC domain fulfils a principal role in both the intra- and/or inter-molecular interactions of LRRK2 (Gloeckner et al. 2006, Deng et al. 2008, Greggio et al. 2008). We found that the ROC domain strongly interacts with the COR domain and the COR-kinase tandem domain, while the interaction between ROC and kinase is rather weak. Although we also confirmed the propensity for the ROC domain to dimerize, we demonstrated that the ROC:COR interaction is favoured over ROC:ROC dimerization, showing that the ROC:COR interaction is a major interaction within the catalytic core region of LRRK2. The implications of this interaction are better understood in light of the 3D homology model of the LRRK2 ROC-COR tandem domain, based on the crystal structure of a Roco protein from the bacterium C.tepidum (Gotthardt et al. 2008). Indeed, the model shows that the inter-molecular interaction between 2 ROC-COR units is a back to back conformation while the intra-molecular ROC:COR binding interface occurs opposite to the dimer interface. Interestingly, the Y1699C mutant which strengthens the ROC:COR interaction in our co-immunoprecipation, GST-pulldown and YTH experiments, maps to the intra-molecular ROC:COR binding interface. This implies that the ROC:COR interaction is important in the regulation of ROC-COR dimerization which in turn regulates LRRK2 GTPase activity. Based on this model, also the R1441 residue is situated near the intra-molecular ROC:COR interface. However since this residue is not conserved between the C. tepidum Roco and LRRK2, this should be viewed with caution.

The ROC domain of LRRK2 shows homology with Ras proteins which function as molecular switches that relay signals in intracellular signaling cascades in a guanine nucleotide dependent manner (Bhattacharya et al. 2004, Vetter & Wittinghofer 2001). Therefore, we asked ourselves whether the decrease in GTPase activity, observed for the Y1699C mutant, could be due to a reduction in GTP binding capacity of the full-length protein. We did not observe a difference in the specificity or selectivity of GTP-binding of LRRK2Y1699C in comparison with the wild type protein. This is in line with the observation of West et al., showing even a slight increase in GTP-binding of LRRK2Y1699C in a similar GTP-binding assay (West et al. 2007). Secondly, we wondered whether the nucleotide bound state of ROC influences the ROC to COR-kinase interaction. Our results show that both GTPγS- and GDP-loaded ROC bind slightly more efficiently to COR-kinase (wt and Y1699C) than non-loaded ROC protein, indicating that both forms of guanosine nucleotides contribute to a stabilization of the ROC:COR interaction. However, only a subtle enhancement in ROC to COR-kinase binding of GTPγS-bound ROC compared to GDP-bound ROC was observed, suggesting that the ROC:COR interaction and activities regulated by this interaction are not significantly influenced by the activation state of ROC. This is in line with the moderate increase in LRRK2 auto-phosphorylation following GTPγS treatment and the lack of inhibition of auto-phosphorylation activity of LRRK2 following GDP treatment (West et al. 2007, Smith et al. 2006). These observations support a scenario on the internal LRRK2 regulation we have proposed recently, namely that as well as regulation of LRRK2 kinase by LRRK2 ROC GTPase the reverse may occur, namely that ROC GTPase functions are controlled by LRRK2 kinase activity (Taymans & Cookson 2010). Indeed, LRRK2 phosphorylates itself at multiple sites in the ROC domain (Greggio et al. 2009, Kamikawaji et al. 2009, Gloeckner et al. 2010), and ROC activity may therefore be influenced by LRRK2 kinase activity.

In conclusion, our data show that the Y1699C pathogenic mutation in the COR domain reduces LRRK2 GTPase activity, weakens ROC-COR dimerization and strengthens the intra-molecular ROC:COR interaction. Our data allow us to propose a scenario combining inter-and intra-molecular aspects: the Y1699C mutation, situated on the intra-molecular ROC:COR interface, strengthens the intra-molecular ROC:COR interaction, thereby weakening the local dimerization of LRRK2 at the ROC-COR domain tandem which results in a decrease of LRRK2 GTPase activity (supplementary Fig. 6). Therefore, the ROC:COR interaction may constitute a novel internal regulation mechanism of LRRK2 GTPase activity and allosteric modulation of the intra-molecular ROC:COR interaction may present a new target for LRRK2 based PD treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Fund for Scientific Research FWO Vlaanderen (G.0406.06, G. 0666.09, postdoctoral fellowship to J-MT and doctoral fellowships to VD, RV and EL), the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (project SBO 80020), the K.U.Leuven OT/08/052A and IOF-KP/07/001 and the Wellcome Trust (WT088145 to KH). This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging. We thank Rosa M Sancho for generating LRRK2 YTH constructs. We thank Petri Ollikainen for his contribution in the GTPase assays.

Abbreviations

- COR

C-terminal of ROC

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- HEK

human embryonal kidney

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- kin

kinase

- LRR

leucine rich repeat

- LRRK2

leucine-rich repeat kinase 2

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- ROC

Ras of complex proteins

- Roco

ROC-COR

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- YTH

yeast two-hybrid

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Anand VS, Reichling LJ, Lipinski K, et al. Investigation of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 : enzymological properties and novel assays. Febs J. 2009;276:466–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baekelandt V, Claeys A, Eggermont K, Lauwers E, De Strooper B, Nuttin B, Debyser Z. Characterization of lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer in adult mouse brain. Hum.Gene Ther. 2002;13:841–853. doi: 10.1089/10430340252899019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benard V, Bohl BP, Bokoch GM. Characterization of rac and cdc42 activation in chemoattractant-stimulated human neutrophils using a novel assay for active GTPases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13198–13204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV, Ferguson SS. Small GTP-binding protein-coupled receptors. Biochem Soc.Trans. 2004;32:1040–1044. doi: 10.1042/BST0321040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskup S, West AB. Zeroing in on LRRK2-linked pathogenic mechanisms in Parkinson's disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1792:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosgraaf L, Van Haastert PJ. Roc, a Ras/GTPase domain in complex proteins. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2003;1643:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brice A. Genetics of Parkinson's disease: LRRK2 on the rise. Brain. 2005;128:2760–2762. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson K, McGuffin LJ, Marsden RL, Ward JJ, Sodhi JS, Jones DT. Protein structure prediction servers at University College London. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:W36–38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dachsel JC, Taylor JP, Mok SS, et al. Identification of potential protein interactors of Lrrk2. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13:382–385. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics system on World Wide Web. 2002 http://www.pymol.org.

- Delhaise P, Bardiaux M, De Maeyer M, et al. The Brugel Package - Toward Computer-Aided-Design of Macromolecules. Journal Molecular Graphics. 1988;6:219–219. [Google Scholar]

- Deng J, Lewis PA, Greggio E, Sluch E, Beilina A, Cookson MR. Structure of the ROC domain from the Parkinson's disease-associated leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 reveals a dimeric GTPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1499–1504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709098105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet J, De Maeyer M, Hazes B, Lasters I. The Dead End Elimination theorem and its use in protein side chain positioning. Nature. 1992;356:539–542. doi: 10.1038/356539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser A, Sali A. Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Methods in enzymology. 2003;374:461–491. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasper R, Meyer S, Gotthardt K, Sirajuddin M, Wittinghofer A. It takes two to tango: regulation of G proteins by dimerization. Nature reviews. 2009;10:423–429. doi: 10.1038/nrm2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser T. Molecular genetic findings in LRRK2 American, Canadian and German families. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2006:231–234. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloeckner CJ, Boldt K, von Zweydorf F, Helm S, Wiesent L, Sarioglu H, Ueffing M. Phosphopeptide analysis reveals two discrete clusters of phosphorylation in the N-terminus and the Roc domain of the Parkinson-disease associated protein kinase LRRK2. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1738–1745. doi: 10.1021/pr9008578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloeckner CJ, Kinkl N, Schumacher A, Braun RJ, O'Neill E, Meitinger T, Kolch W, Prokisch H, Ueffing M. The Parkinson disease causing LRRK2 mutation I2020T is associated with increased kinase activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:223–232. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotthardt K, Weyand M, Kortholt A, Van Haastert PJ, Wittinghofer A. Structure of the Roc-COR domain tandem of C. tepidum, a prokaryotic homologue of the human LRRK2 Parkinson kinase. Embo J. 2008;27:2239–2249. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greggio E, Cookson MR. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 mutations and Parkinson's disease: three questions. ASN Neuro. 2009;1 doi: 10.1042/AN20090007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greggio E, Taymans JM, Zhen EY, et al. The Parkinson's disease kinase LRRK2 autophosphorylates its GTPase domain at multiple sites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;389:449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greggio E, Zambrano I, Kaganovich A, et al. The Parkinson disease-associated leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) is a dimer that undergoes intramolecular autophosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16906–16914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708718200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Gandhi PN, Wang W, Petersen RB, Wilson-Delfosse AL, Chen SG. The Parkinson's disease-associated protein, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), is an authentic GTPase that stimulates kinase activity. Experimental cell research. 2007;313:3658–3670. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey K, Duguid IC, Alldred MJ, et al. The GDP-GTP exchange factor collybistin: an essential determinant of neuronal gephyrin clustering. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5816–5826. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugarvoll K, Wszolek ZK. PARK8 LRRK2 parkinsonism. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2006;6:287–294. doi: 10.1007/s11910-006-0020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy DG, Falchi M, O'Sullivan SS, et al. Phenotype, genotype, and worldwide genetic penetrance of LRRK2-associated Parkinson's disease: a case-control study. Lancet neurology. 2008;7:583–590. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito G, Okai T, Fujino G, Takeda K, Ichijo H, Katada T, Iwatsubo T. GTP binding is essential to the protein kinase activity of LRRK2, a causative gene product for familial Parkinson's disease. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1380–1388. doi: 10.1021/bi061960m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT. GenTHREADER: an efficient and reliable protein fold recognition method for genomic sequences. Journal of molecular biology. 1999;287:797–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikawaji S, Ito G, Iwatsubo T. Identification of the autophosphorylation sites of LRRK2. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10963–10975. doi: 10.1021/bi9011379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch RD, Joly E. An improved PCR-mutagenesis strategy for two-site mutagenesis or sequence swapping between related genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1848–1850. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CL, Rovelli G, Springer W, Schall C, Gasser T, Kahle PJ. Homo-and heterodimerization of ROCO kinases: LRRK2 kinase inhibition by the LRRK2 ROCO fragment. Journal of neurochemistry. 2009;111:703–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus UG, Heyworth PG, Kinsella BT, Curnutte JT, Bokoch GM. Purification and characterization of Rac 2. A cytosolic GTP-binding protein that regulates human neutrophil NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23575–23582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korr D, Toschi L, Donner P, Pohlenz HD, Kreft B, Weiss B. LRRK1 protein kinase activity is stimulated upon binding of GTP to its Roc domain. Cellular signalling. 2006;18:910–920. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung IW, Lassam N. Dimerization via tandem leucine zippers is essential for the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase, MLK-3. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32408–32415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis PA, Greggio E, Beilina A, Jain S, Baker A, Cookson MR. The R1441C mutation of LRRK2 disrupts GTP hydrolysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:668–671. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Tan YC, Poulose S, Olanow CW, Huang XY, Yue Z. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2)/PARK8 possesses GTPase activity that is altered in familial Parkinson's disease R1441C/G mutants. Journal of neurochemistry. 2007;103:238–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Dunn L, Greggio E, Krumm B, Jackson GS, Cookson MR, Lewis PA, Deng J. The R1441C mutation alters the folding properties of the ROC domain of LRRK2. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1792:1194–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margalit DN, Romberg L, Mets RB, Hebert AM, Mitchison TJ, Kirschner MW, RayChaudhuri D. Targeting cell division: Small-molecule inhibitors of FtsZ GTPase perturb cytokinetic ring assembly and induce bacterial lethality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:11821–11826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404439101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata IF, Wedemeyer WJ, Farrer MJ, Taylor JP, Gallo KA. LRRK2 in Parkinson's disease: protein domains and functional insights. Trends in neurosciences. 2006;29:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho RM, Law BM, Harvey K. Mutations in the LRRK2 Roc-COR tandem domain link Parkinson's disease to Wnt signalling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3955–3968. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S, Webber PJ, West AB. Dependence of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) kinase activity on dimerization. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:36346–36356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WW, Pei Z, Jiang H, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ross CA. Kinase activity of mutant LRRK2 mediates neuronal toxicity. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1231–1233. doi: 10.1038/nn1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taymans JM, Cookson MR. Mechanisms in dominant parkinsonism: The toxic triangle of LRRK2, alpha-synuclein, and tau. Bioessays. 2010;32:227–235. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A. The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions. Science. 2001;294:1299–1304. doi: 10.1126/science.1062023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AB, Moore DJ, Choi C, et al. Parkinson's disease-associated mutations in LRRK2 link enhanced GTP-binding and kinase activities to neuronal toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:223–232. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard FS, Kimple AJ, Johnston CA, Siderovski DP. A direct fluorescence-based assay for RGS domain GTPase accelerating activity. Anal Biochem. 2005;340:341–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Coombes CE, Kilaru A, Li X, Gitler AD, Bowers WJ, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Moore DJ. GTPase activity plays a key role in the pathobiology of LRRK2. PLoS genetics. 2010;6:e1000902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.