Abstract

Growth factor receptor (GFR) signaling controls epithelial cell growth by responding to various endogenous or exogenous stimuli and subsequently activating downstream signaling pathways including Stat3, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MAPK, and c-Src. Environmental chemical toxicants and UVB irradiation cause enhanced and prolonged activation of GFR signaling and downstream pathways that contributes to epithelial cancer development including skin cancer. Recent studies, especially those using tissue-specific transgenic mouse models, have demonstrated that GFRs and their downstream signaling pathways contribute to all three stages of epithelial carcinogenesis by regulating a wide variety of biological functions including proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, cell adhesion and migration. Inhibiting these signaling pathways early in the carcinogenic process results in reduced cell proliferation and survival, leading to decreased tumor formation. Collectively, these studies suggest that GFR signaling and subsequent downstream signaling pathways are potential targets for the prevention of epithelial cancers including skin cancer.

Keywords: PI3K, Akt, Stat3, Src, MAPK, epithelial carcinogenesis, growth factor signaling

INTRODUCTION

The multistage model of mouse skin carcinogenesis is one of the best-defined experimental models and has provided an important tool in understanding the multistage nature of epithelial cancer development [1]. In particular, this model has aided in identifying underlying cellular, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms associated with the various stages of epithelial carcinogenesis [1–4]. In this model, tumor development occurs via three distinct stages: initiation, promotion, and progression. Tumor initiation by a single topical subcarcinogenic dose of a genotoxic carcinogen, such as 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA), induces a mutation in a critical gene or genes and typically, this stage does not produce morphological changes in mouse skin [1–3]. The Ha-ras gene appears to be a primary target gene for the initiation stage in this carcinogenesis model and is mutated following exposure to DMBA [2]. Following initiation, tumor promotion occurs by repeatedly applying a nonmutagenic tumor promoter, such as 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), which affects gene expression and stimulates epidermal cell proliferation and hyperplasia. Many genes that encode growth regulatory molecules are upregulated transcriptionally while many other proteins are activated by post-translational modification or in some cases enzymatic activities are directly stimulated in response to skin tumor promoter treatment (reviewed in [1,3–6]). Some of these molecules include: protein kinase C (PKC), transforming growth factor (TGF) α, TGFβ, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), erbB2, Stat3, c-Src, Akt, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), glucocorticoid receptor, cytokines, prostaglandins, c-myc, c-fos, egr-1 and E2F1. During the promotion stage, initiated cells undergo clonal expansion, resulting in the development of premalignant papillomas. These premalignant lesions have been shown to overexpress a variety of genes that contribute to their ability to grow and progress in the absence of further external stimuli. A number of these genes have been found to be similar to those that are upregulated during tumor promotion [1,3,4,6–8].

The progression of papillomas into malignant squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) occurs stochastically and is independent of tumor promoter treatment. An increased probability of genetic alterations in the expanded population of initiated cells and subsequent selection converts papillomas to SCCs [2,4,9,10]. Numerous gene expression changes are believed to contribute to tumor progression in this model including those involved in epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) [11]. Recently, a gene expression signature that is associated with high risk for malignant conversion of papillomas was reported [12]. This gene expression profile was identified in a two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol using SENCAR mice and distinguished early stage papillomas likely to convert to SCC from those with a lower probability of malignant conversion.

Our laboratory has been using the two-stage mouse skin carcinogenesis model for investigating molecular mechanisms contributing to human epithelial cancer development, including skin cancer. As noted above, growth factor signaling plays an important role in both the development and progression of skin tumors in this model system. One such growth factor receptor system, the erbB family and in particular the EGFR (erbB1) has been shown to play a significant role in epithelial carcinogenesis in multiple tissues [13–15]. Elevated expression of EGFR and/or its ligands is common in many types of epithelial cancer, and such changes have been shown to be an important component for maintaining the proliferative capacity of the tumor cells. In this review, we summarize evidence for the involvement of the EGFR and other erbB family members as well as several other growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and their downstream signaling pathways, including Stat3, PI3K/Akt/mTOR, MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), and c-Src in epithelial carcinogenesis (see Figure 1). Furthermore, evidence is presented demonstrating these pathways are potential targets for prevention of epithelial carcinogenesis.

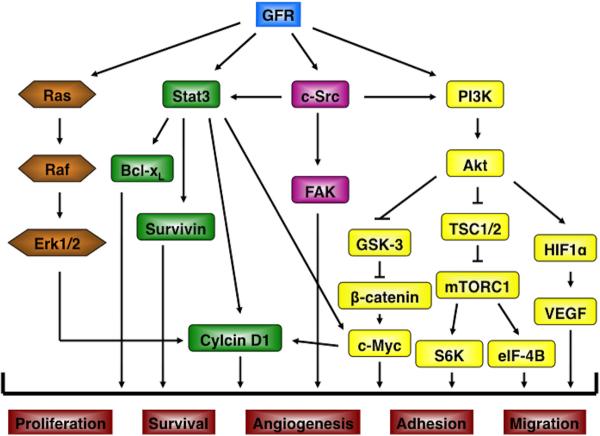

Figure 1.

GFR signaling pathways in epithelial carcinogenesis. GFR signaling regulates multiple downstream signaling pathways. Several important pathways are shown in this Figure, including: Ras, Stat3, c-Src, and PI3K/Akt. These downstream pathways contribute to increase cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, adhesion and migration during epithelial carcinogenesis by regulating target gene expression.

ERBB FAMILY RTK SIGNALING PATHWAYS AND EPITHELIAL CARCINOGENESIS

RTKs are involved in growth control and alterations in several of these ligand/receptor systems may result in uncontrolled growth and oncogenic transformation [16,17]. One of the best-studied RTK families is the erbB family. The erbB family includes erbB1 (EGFR), erbB2, erbB3 and erbB4. Although all of the erbB family members share similarities in primary structure, receptor activation mechanisms, and signal transduction patterns, they bind to different ligands and ligand-dependent activation of erbB family receptors can lead to both homodimerization and heterodimerization [18]. The EGFR (or erbB1) was the first member to be cloned and showed considerable homology to the avian erythroblastosis virus transforming protein, v-erbB [19]. ErbB2 is the human homolog of the neu oncogene that was initially isolated from chemically induced rat neuroblastomas [20,21] and shares close homology with the EGFR [22]. To date, no ligand has been identified for erbB2 (also named HER2 in humans and neu in rodents); it can only act as part of a heterodimer with a ligand-bound receptor, often EGFR or erbB3 (also named HER3 in humans) [23,24]. In contrast, erbB3 cannot generate signals in isolation because the kinase function of this receptor is impaired, thus relying on interaction with erbB2 for subsequent downstream signaling events [25]. The expression of erbB family members except erbB4 has been reported in mouse and human skin, and A431 skin carcinoma cells [26,27]. As noted, the level of erbB4 expression appears to be very low (or not at all) in mouse epidermis and in cultured mouse keratinocytes [26,28]. Recently, Prickett and collegues identified erbB4 mutations in cutaneous metastatic melanoma resulting in increased kinase activity and transformation activity [29].

As the erbB family signaling pathways are central to regulating epithelial cell growth, it is not surprising that they are dysregulated during mouse skin carcinogenesis. In this regard, multiple EGFR ligands (e.g., TGFα, amphiregulin and HB-EGF) are coordinately upregulated during skin tumor promotion, leading to EGFR activation [30–32]. Previous studies from our laboratory also demonstrated that activation of the EGFR is a common response in mouse epidermis following treatment with diverse skin tumor promoters including TPA, okadaic acid, and chrysarobin [26,33]. Moreover, the EGFR is overexpressed and constitutively activated in skin tumors (papillomas and SCCs) generated via the two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol [34]. Transgenic mice overexpressing TGFα or erbB2 have epidermal hyperplasia and are highly sensitive to two-stage skin carcinogenesis [35–39]. In addition to the EGFR, both erbB2 and c-src (see below) are activated in tumor promoter treated mouse epidermis [26]. In contrast, blockade of EGFR kinase inhibited TPA-mediated epidermal hyperproliferation [26] and transgenic mice expressing a dominant negative EGFR showed resistance to two-stage carcinogenesis [40]. The dual EGFR/erbB2 Inhibitor, GW2974 (200 ppm in the diet) inhibited skin tumor promotion in both BK5.erbB2 transgenic mice and non-transgenic mice during a two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol (Kiguchi and DiGiovanni, unpublished data). Furthermore, increasing evidence exists demonstrating that signaling through the EGFR and/or erbB2 is rapidly activated in response to ultraviolet (UV) irradiation leading to increased keratinocyte proliferation and epidermal hyperplasia [41–43]. UV-induced tumorigenesis in mouse skin was blocked by topical treatment of an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor and an erbB2 inhibitor, suggesting an important role of erbB family members including EGFR and erbB2 during epithelial carcinogenesis by UV irradiation [41,44].

Similar to both chemically-induced and UVB-induced epithelial tumors in mice, autocrine signaling through the EGFR plays an important role in the process of tumor development in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (SCCHN) [45]. Moreover, EGFR signaling is associated with malignant progression in breast cancers [46,47]. Collectively, these data suggest a critical role for EGFR signaling pathways in epithelial cancers. In the mouse skin model, EGFR signaling appears to play a critical role in mediating tumor promoter-induced epidermal hyperproliferation and epithelial tumor growth. Furthermore, as noted above the available data suggest that the EGFR and erbB2 represent important targets for prevention of epithelial cancers especially where these RTKs are activated early in the carcinogenic process.

INSULIN-LIKE GROWTH FACTOR-1 RECEPTOR (IGF-1R) SIGNALING AND EPITHELIAL CARCNOGENESIS

The importance of IGF-1R signaling in carcinogenesis is evident by the fact that IGF-1 and/or its receptor are overexpressed in many human tumors, including lung [48], breast [49,50] and colon [51]. Furthermore epidemiologic evidence has suggested that elevated serum levels of IGF-1 are a risk factor for the development of breast, colon, and prostate cancer in humans [52,53]. When over-expressed, IGF-1 can provide cancer cells from many tumor types protection against a variety of chemotherapeutic and radiation therapies [54]. It has been demonstrated in many in vitro systems that increased IGF-1R signaling leads to increased mitogenesis, cell cycle progression, and protection against different apoptotic stresses [55–57].

The IGF-1R belongs to the family of transmembrane RTKs and shares 70% homology with the insulin receptor [58]. IGF-1, IGF-II, and insulin all bind to and activate the IGF-1R [59], although higher concentrations of insulin are necessary to activate the IGF-1R. Upon activation, the IGF-1R undergoes autophosphorylation on tyrosine residues, which leads to activation of many different signaling pathways (again see Figure 1). Activation of these signaling pathways, in turn, results in many complex cellular functions including cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, cell differentiation, chemotaxis, hormone and neurotransmitter secretion, amino acid and glucose uptake, and protection against apoptosis [60]. A number of proteins bind to specific phosphorylated tyrosine residues in the C-terminal portion of the IGF-1R β-subunit and in turn become phosphorylated, including IRS1, SHC, and Crk. Activated IRS1 and SHC provide docking sites for src-homology (SH2) containing proteins including the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K, and the guanine-nucleotide exchange factor GRB2/SOS [61], respectively.

Activation of GRB2/SOS activates the MAPK pathway that has also been shown to provide anti-apoptotic properties [61,62], besides its well-characterized mitogenic actions. Other signaling molecules that have been shown to be activated upon ligand binding to the IGF-1R include Syp, Nck, and Crk [55,61,62]. Signaling through PI3K also has been shown to play a role in the mitogenic potential of many growth factor receptors including IGF-1R [63]. Activation of PI3K can also lead to an inhibition of apoptosis through activation of the serine/threonine kinase Akt [64–67]. Upon activation, Akt conveys a wide variety of cellular responses including increasing protein synthesis, proliferation, and cell survival [67] (see below).

Data have accumulated indicating that signaling through Akt via the IGF-1R, EGFR, or other growth factor receptors plays an important role in epithelial carcinogenesis in the mouse skin model. In this regard, overexpression of IGF-1 in the epidermis of transgenic mice using the human keratin 1 (HK1) promoter or the bovine keratin 5 (BK5) promoter (i.e., BK5.IGF-1 transgenic mice) led to epidermal hyperplasia and enhanced susceptibility to two-stage skin carcinogenesis [68,69]. BK5.IGF-1 transgenic mice also exhibited spontaneous skin tumor formation [68,69]. In addition, upregulation of epidermal PI3K and Akt activities as well as upregulation of cell cycle regulatory proteins also was observed in epidermis of BK5.IGF-1 transgenic mice [68,70]. Further studies revealed that topical application of the PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, directly inhibited these constitutive biochemical changes observed in the epidermis of BK5.IGF-1 transgenic mice and inhibited IGF-1-mediated skin tumor promotion in these mice in a dose-dependent manner [68,70]. Finally, recent work from our laboratory has shown that reduction in circulating levels of IGF-1 can significantly block the development of skin tumors in mice induced via the two-stage protocol [71]. This dramatic reduction in susceptibility to skin tumor development correlated with reduced signaling through the IGF-1R and PI3K/Akt. These data support the hypothesis that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is involved in regulating skin tumor promotion by IGF-1. Further evidence, described below, indicates that activation of Akt signaling is an extremely important event in tumor promotion and tumor progression, in general, in mouse skin carcinogenesis.

c-met SIGNALING AND EPITHELIAL CARCNOGENESIS

c-met is a heterodimer RTK composed of disulfide-linked subunits of alpha (extracellular domain) and beta (extracellular, transmembrane, and intracellular catalytic domain) [72]. The ligand for c-met, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/scatter factor (SF), was first identified as a mitogen for hepatocytes [73,74] and a cytokine for epithelial cells to stimulate cell motility as a scatter factor [75,76]. HGF binding to its receptor, c-met induces dimerization followed by autophosphorylation at tysosine residues, leading to activation of c-met downstream signaling pathways [77] (again see Figure 1). Phosphorylated c-met receptor provides multiple docking sites for the adaptor proteins such as Grb2 and Shc as well as PI3K leading to activation of MAPK, Akt, Stat3 and other signaling pathways [78,79].

HGF has also been described as a modulating growth factor for keratinocytes, kidney cells and several cell lines [80–82]. Several groups have reported that epithelial cells produced HGF as well as fibroblasts [83,84]. Recently, several studies have shown that c-met/HGF plays an essential role during wound repair in the skin [85,86] and autocrine HGF production was observed in injured skin keratinocytes [85]. Moreover, defects in the regeneration of skin wounds were shown in c-met-deficient keratinocytes and conditional c-met mutant mice [86].

The c-met receptor tyrosine kinase and its ligand, HGF are overexpressed and/or activated in a wide variety of human malignancies and c-met is amplified during the transition stage from primary tumors to metastatic tumors [87], suggesting that enhanced activation of c-met contributes to increased tumor progression. “Humanized” HGF transgenic mice generated using a metallothionein gene promoter spontaneously developed malignant melanoma [88]. Interestingly, UV irradiation three times a week to the skin of HGF transgenic mice significantly elevated sensitivity to the development of non-melanoma skin tumors including SCC, but not to melanoma compared to wild type mice [89]. This enhanced sensitivity of the HGF transgenic mice to SCC by UV irradiation may be explained, in part, by the observation that HGF inhibits UV-induced apoptosis in culture human keratinocytes via activated PI3K/Akt signaling [90]. Notably, several different epithelial tumor cell lines expressing the uncleavable HGF (inactive precursor) that inhibits HGF-induced c-met activation using a lentaviral vector, showed suppressed tumor growth and decreased metastases [91].

In addition, increasing evidence has demonstrated that cross-talk between c-met and other cell RTKs such as the EGFR family contribute to the development of tumor invasiveness and drug resistance in tumors [92,93]. Interestingly, Ron, a member of the c-met family, isolated from a human foreskin keratinocyte cDNA library [94] is expressed in several epithelial cell types as well as granulocytes and monocytes [95]. HGF-induced activation of c-met also leads to activation of Ron by transphosphorylating tyrosine residues, showing cross-talking between c-met and Ron and coordinated intracellular signaling networks [96]. Recently, studies using a mouse with a tyrosine kinase deficient mutant (TK−/−) of Ron have shown a role for this RTK in the mouse skin model for both papilloma development and for papilloma progression to SCCs [97].

DOWNSTREAM SIGNALING PATHWAYS AS TARGETS FOR CANCER PREVENTION

Src

Src (v-src) was the first oncogene discovered as the transforming protein of the avian Rous sarcoma virus [98]. The c-src gene, the cellular homologue of v-src, encodes an intracellular non-receptor tyrosine kinase with a molecular weight of 60 kDa [99]. c-Src is the prototypical member of the Src family kinases that include Fyn, Yes, Hck, Lck, Lyn, Blk, Yrk, and Fgr [100,101]. c-Src structurally contains four Src homology (SH) domains. The SH1 domain contains the kinase domain and a conserved tyrosine residue for autophosphorylation. The SH2 domain binds to specific sites of tyrosine phosphorylation. The SH3 domain binds to specific proline-rich sequences. Thus, these latter two SH domains (i.e., SH2 and SH3) are involved in the regulation of Src activity. The SH4 domain contains a myristoylation site needed for membrane localization. In addition, c-Src contains a unique tyrosine phosphorylation site (Tyr 529 in mouse and Tyr 530 in human) located near the C-terminus that negatively regulates its activity [102].

Src is one of the major kinases that are downstream of many RTKs including growth factor receptors, and is activated by the EGFR, erbB2, erbB3, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) [102,103]. After activation, Src subsequently activates its downstream targets including focal adhesion kinase, PI3K, and Stat3 [104,105]. Src plays important roles in various cellular processes including proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, motility, migration, and invasion [106]. With regard to its cellular regulation related to growth factor signaling, studies have shown that Src activation is involved in oncogenic processes and constitutive activation of Src is detected in a variety of human cancers including colon, breast, head and neck, pancreas, and lung cancers [107,108]. In particular, increased Src expression and/or activity has been highly linked to progression, invasion, and metastasis [109].

Src is also highly expressed in human skin cancers, including melanomas [110,111]. Recent studies using several epidermal-specific Src transgenic mouse models have shown that Src activation plays a role in tumor promotion, malignant progression and metastasis during skin carcinogenesis [26,112–114]. Src kinase activity was elevated in cultured mouse keratinocytes stimulated with EGFR. Elevated Src activity was also found in the epidermis of mice treated with TPA, and in the epidermis of HK14.TGFα transgenic mice where expression of human TGFα was targeted to basal keratinocytes using the HK14 promoter [26]. HK1.src529 transgenic mice that overexpress a constitutively active mouse c-src mutant (src529) in the suprabasal layer of the epidermis showed enhanced susceptibility to tumor promotion by TPA [114]. Studies using another transgenic mouse model (i.e., HK14.src530) showed that expression of a constitutively active human src530 mutant in basal keratinocytes led to a severe epidermal hyperplasia and early death [112]. However, overexpression of wild-type human c-src cDNA (referred to as srcwt) under control of the BK5 promoter led to generation of several mouse lines with a milder skin phenotype suitable for long term tumor experiments [112]. In particular, two-stage skin carcinogenesis experiments using BK5.srcwt line B mice demonstrated that these mice were hypersensitive to the tumor promoting effects of TPA. Further observation indicated that malignant conversion of papillomas to SCCs occurred more rapidly in BK5.srcwt line B mice compared with nontransgenic littermates. SCCs that developed in BK5.srcwt line B mice also had a higher tendency to metastasize to other organs [112]. In addition, more recent studies using “gene-switch” src530 transgenic mice (ML.GLVPc/TK.src530 and HK14.GLp65/TK.src530 bitrangenic mice), where the src530 mutant transgene expression was induced by topical treatment of a progesterone receptor antagonist RU486, confirmed these earlier observations [113]. Collectively, these studies have provided strong evidence that Src plays an important role in tumor promotion. In addition, src activation also appears to play an important role in malignant progression and metastasis in this model of epithelial carcinogenesis. Thus, targeting src alone or in combination with other growth factor signaling pathways may be an effective strategy for prevention of certain epithelial cancers.

STAT3

Signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) are latent cytoplasmic proteins that are activated by growth factors, cytokines, and hormones and participate in various cellular functions including cell proliferation, survival, and angiogenesis. [115,116]. There are seven members of the mammalian STAT family that have been identified, which are encoded by seven distinct genes [117]; Stat1, Stat2, Stat3, Stat4, Stat5a, Stat5b and Stat6. STATs consist of six functional domains that are shared by all seven STAT family members and contain an N-terminal domain, coiled-coil domain, DNA-binding domain, linker domain, SH-2 domain and tyrosine activation motif, and transcriptional activation domain. Upon activation by a wide variety of cell surface receptors, such as growth factor receptors, STATs are phosphorylated and then dimerize. Activated STAT dimers translocate to the nucleus, bind to consensus DNA sequences, and modulate the expression of target genes [116,118]. Studies using knockout or tissue specific knockout mouse models of STATs have revealed their crucial roles in a wide variety of biological functions, including development, cell growth, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and cell motility [116,118].

Among the STAT family members, Stat3 regulates the expression of target genes involved in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, angiogenesis, cell invasion, and metastasis [119]. For example, Stat3-mediated regulation of cyclin D1 and c-myc expression contributes to increased cell proliferation in cancer cells [120–122]. Stat3-mediated regulation of anti-apoptotic genes, such as Mcl-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and survivin, contributes to cell survival [123–126]. In addition, Stat3-mediated regulation of the expression of VEGF and matrix metalloproteinases contributes to angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and metastasis [127–129]. In accordance with its critical roles in the regulation of cellular processes associated with carcinogenesis, Stat3 is constitutively activated in many epithelial cancers including head and neck, breast, lung, skin, and prostate [130–133]. Inhibition of Stat3 by anti-sense oligonucleotides or dominant negative Stat3 protein can lead to growth inhibition of epithelial cancer cells [45,134]. Collectively, these studies indicate that Stat3 is required for the maintenance of proliferation and survival of various epithelial cells, including epithelial cancer cells.

The development of Stat3 knockout (KO) and skin specific Stat3 KO mice led to the discovery that Stat3 is involved in wound healing [135,136]. As a result, further studies have shown that Stat3 activation plays critical roles in skin carcinogenesis [137,138]. In this regard, Stat3 was found to be activated in mouse epidermis following treatment with different classes of tumor promoters including TPA, okadaic acid, and chrysarobin [139]. Studies using epidermal-specific Stat3-deficient mice showed that Stat3 is required for both the initiation and promotion stages of epithelial carcinogenesis [139]. At the time of initiation with DMBA, keratinocytes undergoing apoptosis were significantly increased in Stat3-deficient mice compared with nontransgenic littermates. In these initial experiments, keratinocytes undergoing apoptosis were noted in or near the bulge region [the site of the major population of keratinocyte stem cells (KSCs)] in Stat3-deficient mice during tumor initiation with DMBA [139]. Based on this observation, we recently generated bulge-region KSC-specific Stat3-deficient mice (i.e., K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice) and have provided further evidence that Stat3 is required for survival of bulge-region KSCs during the initiation stage of skin carcinogenesis [140]. In these studies, the number of apoptotic KSCs in the bulge-region was significantly increased in K15.CrePR1 × Stat3fl/fl mice by inducible deletion of Stat3 prior to tumor initiation compared with control littermates. In addition, the frequency of Ha-ras codon 61 A182→T mutations was also decreased [140]. Furthermore, the number of skin tumors that developed in a two-stage skin carcinogenesis protocol was dramatically reduced by targeted deletion of Stat3 in bulge region KSCs at the time of initiation [140].

Stat3 is also required for the tumor promotion stage of two-stage skin carcinogenesis as noted above. In this regard, deletion of Stat3 significantly reduced epidermal hyperproliferation induced by TPA [139]. Stat3 deletion also reduced the levels of cyclin D1 and c-myc required to support epidermal proliferation during the early stages of tumor promotion and clonal expansion of initiated cells. Further studies using inducible Stat3-deficient mice (K5.Cre-ETT2 × Stat3fl/fl) confirmed its critical roles in tumor development during both the initiation and promotion stages of carcinogenesis [141].

Finally, using transgenic mice in which the expression of a constitutively active/dimerized form of Stat3 (Stat3C) was targeted to the basal layer of epidermis (using the BK5 promoter), we demonstrated a role for Stat3 in tumor progression during two-stage skin carcinogenesis [142]. In these studies, skin tumors developed in BK5.Stat3C mice at a much higher rate. Furthermore, these tumors bypassed the premalignant stage and initially developed as carcinoma in situ [142]. Ultimately, all of the tumors in BK5.Stat3C mice rapidly became SCCs. The rapid progression of tumors in this model correlated with increased expression of Twist and loss of expression of E-cadherin which are changes associated with EMT [142].

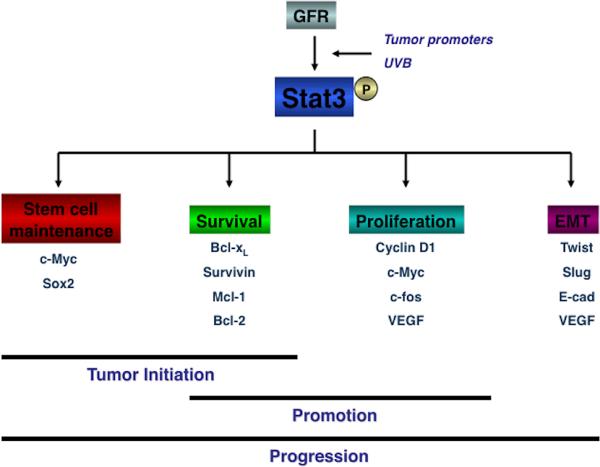

In addition to chemically induced two-stage skin carcinogenesis, Stat3 plays a critical role in UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis. Stat3 is phosphorylated at tyrosine residue 705 (Tyr705) following UVB exposure [143]. Stat3 is also phosphorylated at serine residue 727 (Ser727) in transgenic mice overexpressing protein kinase Cε(PKCε) following UVB irradiation [144]. Recent studies using skin-specific gain and loss of function transgenic mice have provided further evidence that Stat3 plays an important role in the development of UVB-induced skin tumors by regulating keratinocyte survival and proliferation following UVB irradiation [133,140]. In this regard, BK5.Stat3C mice were more sensitive to UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis compared with wild-type mice, whereas Stat3-deficient mice were resistant to UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis compared with wild-type mice [140]. Collectively, these studies using various Stat3 transgenic mouse models have suggested that Stat3 has a critical role in all three stages of epithelial carcinogenesis induced by either chemical exposure or UVB irradiation as depicted in Figure 2. The fact that Stat3 plays such an important role early in the carcinogenic process suggests that it is potentially an excellent target for prevention strategies.

Figure 2.

Role of Stat3 in epithelial carcinogenesis. Stat3 has an important role in all three stages of epithelial carcinogenesis induced by either chemical exposure or UVB irradiation. Stat3 regulates the expression of target genes (e.g., c-Myc, cyclin D1, Bcl-xL, VEGF) that are involved in stem cell maintenance, proliferation, survival and EMT, respectively.

Studies focusing on targeting Stat3 through different approaches have shown that Stat3 is a promising target protein for the inhibition of cancer cell growth [134,139,145]. Treatment of cells with antisense oligonucleotides or siRNA for Stat3 inhibited the growth of cancer cells including breast and prostate cancer cells [124,145]. Abrogation of Stat3 activation using a decoy oligonucleotides caused a delay in appearance of papillomas in TG:AC mice treated with TPA [139]. Furthermore, Stat3 oligonucleotide decoy injected directly into existing papillomas induced by a two-stage protocol induced tumor regression [139]. Small MW compounds targeting Stat3, such as indirubin derivatives and platinum compound IS3 295 also showed inhibitory effects on cancer cell growth by inducing apoptosis [146–148]. In addition, several natural dietary agents including the green tea compound epigallocatechin-3-gallate, as well as resveratrol and curcumin have been shown to inhibit Stat3 phosphorylation and suppress cancer cell growth [149–153], including skin tumor promotion by TPA in the two-stage model [154,155].

PI3K/ Akt / mTOR

Akt is a serine/threonine kinase involved in a variety of cellular responses [156–159]. Three Akt isoforms have been found in mammals (Akt1, Akt2, Akt3). Activation of this critical signaling molecule is achieved via a phosphorylation cascade resulting from activation of PI3K by RTKs, such as the EGFR and IGF1-R. Binding of growth factor to the RTK phosphorylates scaffolding adaptor proteins, such as IRS, which then act as a docking site for PI3K thus enabling activation via the receptor. Once activated, PI3K phosphorylates PIP2 (Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate) to produce PIP3 (Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate). PTEN, a lipid phosphatase that acts as a tumor suppressor can reverse this phosphorylation reaction [160–162]. Akt and PDK1 bind PIP3 and translocate to the membrane [158,159]. PDK1 then activates Akt via phosphorylation of the Thr308 residue [158,159] and phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 is mediated by mTORC2, which is activated via a still as yet unknown mechanism [163]. Following activation, Akt regulates a number of cellular processes including: protein translation, glucose metabolism, cell growth and proliferation, and cell survival. As the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is a central regulator of cell metabolism, proliferation, and survival, it is commonly altered in human tumors. PI3K/Akt signaling alteration by gene amplification or overexpression leading to increased Akt activity has been observed in various human cancers including glioblastomas, breast, endometrial, and prostate cancers [164]. PTEN is a crucial negative regulator of this signaling pathway and loss of function mutations or deletions occur in a variety of human cancers [165]. In addition, increased signaling through RTKs by constitutive activation (mutation or ligand overexpression) enhances downstream signaling pathways including PI3K/Akt activity in many types of tumors [165].

In work from our laboratory as noted above, overexpression of IGF-1 in the epidermis of transgenic mice (BK5.IGF-1) induced epidermal hyperplasia, enhanced susceptibility to two-stage skin carcinogenesis and led to spontaneous skin tumor formation [68,69]. Biochemical alterations in the epidermis of these transgenic mice included significantly elevated levels of PI3K, Akt, and cell cycle regulatory proteins. Inhibition of PI3K by topical application of LY294002, a PI3K specific inhibitor, not only directly inhibited these constitutive epidermal biochemical changes, but also inhibited IGF-1–mediated skin tumor promotion in a dose-dependent manner [69]. Segrelles et al reported constitutive activation of epidermal Akt throughout the entire two-stage carcinogenesis process of mouse skin [166]. Overexpression of Akt also led to transformation of a mouse keratinocyte cell line through transcriptional and posttranscriptional processes [167]. More data published by this same group and others [168,169] have further confirmed the involvement of Akt-mediated cellular proliferation in mouse skin tumorigenesis. Recently, additional studies from our laboratory have shown that diverse tumor promoters, including TPA, okadaic acid, or chrysarobin upregulate Akt activity and downstream Akt signaling pathways in epidermis of nontransgenic mice after single and multiple topical treatments [170]. Akt activation following tumor promoter treatment occurred primarily in the basal layer of mouse epidermis including the outer root sheath of hair follicles [170]. Structure-activity studies with phorbol ester analogues also revealed that the magnitude of Akt activation paralleled tumor-promoting activity [170]. Collectively, these data have suggested that Akt and several Akt downstream signaling pathways are activated by diverse skin tumor promoters (including IGF-1) and that some of these pathways may be critical for the process of tumor promotion [170,171].

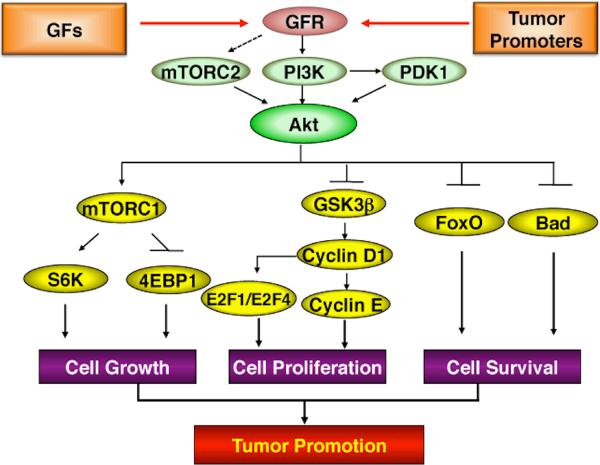

To further evaluate the effects of elevated epidermal Akt activation on multistage epithelial carcinogenesis in mouse skin, transgenic mice overexpressing either Akt1wt or constitutively active Akt1myr in the basal layer of stratified epithelia using the BK5 promoter (BK5.Akt1wt and BK5.Akt1myr) were developed [171]. These mice displayed alterations in epidermal proliferation and differentiation. In addition, transgenic mice with the highest levels of Akt expression developed spontaneous epithelial tumors in multiple organs with age. All of these Akt transgenic lines displayed heightened sensitivity to the epidermal proliferative effects of TPA [171]. In this regard, both hemizygous and homozygous Aktwt and Aktmyr transgenic mice exhibited increased epidermal hyperplasia and epidermal labeling index following treatment with TPA at several doses. In addition, all of the lines displayed a dramatic increase in sensitivity to two-stage skin carcinogenesis using DMBA as the initiator and TPA as the promoter [171]. Collectively, the data from two-stage carcinogenesis experiments using both IGF-1 and Akt transgenic mice support the hypothesis that elevated Akt signaling plays an important role in epithelial carcinogenesis (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Akt signaling pathways contributing to epithelial tumor development. Activation of Akt can be initiated by the binding of growth factors to their receptors or by tumor promoters. Activated PI3K recruits Akt and PDK-1 to the cell membrane, and then Akt is phosphorylated by PDK1 at Thr308 site and mTORC2 at Ser473 site, respectively. Activated Akt mediates signaling pathways downstream to regulate diverse cellular processes. Activated Akt promotes cell proliferation by increased activity of cell cycle proteins, cell growth by enhanced protein synthesis through mTORC1 signaling, and cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis. Thus, elevated Akt activity contributes significantly to epithelial tumor promotion through multiple downstream signaling pathways.

In the Akt transgenic mouse models, overexpression or constitutive activation of Akt led to enhanced epidermal proliferation that correlated with significant elevations of G1 to S phase cell cycle proteins, including cyclin D1, c-myc and E2Fs [171]. In conjunction with these changes, Akt transgenic mice showed elevations in phosphorylation of GSK3β, Bad, FoxO, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and mTOR downstream signaling (e.g., eIF4G, eIF4E and S6K) both in the absence and presence of TPA treatment [171]. Taken together, these data provide direct support for an important role for Akt signaling in epithelial carcinogenesis in vivo, especially during the tumor promotion stage. In addition, these data suggest that elevated Akt activity leads to elevation of several key cell cycle regulatory proteins, possibly in concert with alterations in survival pathways driving both spontaneous tumor development and the increased sensitivity to skin tumor promotion [171]. Figure 3 summarizes how elevated Akt activity contributes to skin tumor promotion through activation of multiple downstream signaling pathways.

The primary mechanism(s) for activation of Akt in mouse epidermis by diverse skin tumor promoters appears to involve activation of erbB family members. In this regard, previous studies demonstrated that treatment with TPA leads to elevated tyrosine phosphorylation of both the EGFR and erbB2 and an increase of EGFR:erbB2 heterodimer formation in mouse epidermis [26,33]. In cultured mouse keratinocytes, increased phosphorylation of the EGFR and erbB2 at tyrosine residues was also seen following TPA treatment [170]. Activation of the EGFR appeared to be integral to TPA-induced activation of Akt. Both PD153035, an inhibitor of EGFR, and GW2974, a dual-specific inhibitor of EGFR and erbB2, effectively reduced activation of Akt and a downstream effector, Fox01/03 (forkhead family of transcription factor), following treatment with TPA as well as TPA-stimulated EGFR and erbB2 tyrosine phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner in mouse skin [170]. Furthermore, TPA-induced activation of Akt was mediated by the PI3K and PDK-1-dependent pathways, not by MAPK pathways [170]. TPA-induced PKC activation in cultured mouse keratinocytes results in increased HB-EGF production, followed by phosphorylation of the EGFR. The pan PKC inhibitor, bisindolylmaleimide I abrogated HB-EGF production and EGFR phosphorylation. However, PKC inhibition by bisindolylmaleimide I before or after TPA treatment stabilized Akt phosphorylation even in the presence of reduced EGFR activation. A serine/threonine phosphatase, PP2A, has been shown to regulate Akt activity [172] and the physical interaction between Akt and the catalytic subunit of PP2A (PP2A C) is induced by TPA in cultured mouse primary keratinocytes [170]. However, the inhibition of PKC also led to a decreased association of Akt with the PP2A catalytic subunit, leading to increased Akt phosphorylation. When used in combination, the EGFR and PKC inhibitors completely abrogated TPA-induced activation of Akt. The above data support a model in which signaling through the EGFR via the formation of EGFR homodimers or EGFR/erbB2 heterodimers may be the primary event leading to Akt activation during tumor promotion in mouse skin [170]. Phosphorylation of mTOR, an Akt downstream target was also induced by TPA treatment in a biphasic manner; early activation of mTOR appeared to be PKC-mediated and then later phosphorylated through activation of Akt (Rho and DiGiovanni, unpublished data). These observations support the hypothesis that elevated Akt activity and subsequent activation of downstream signaling pathways is a common event in mouse keratinocytes following treatment with diverse skin tumor promoters. In addition, signaling through the EGFR via PI3K and PDK-1 dependent pathways may be the primary event leading to Akt activation during tumor promotion in mouse skin. Finally, these data suggested that activation of mTOR may also be critical for mouse skin tumor promotion. This observation is discussed in more detail in the next paragraph.

mTOR is a highly conserved protein serine/ threonine kinase that regulates many cellular responses, including mRNA translation, cell growth, and autophagy [173]. It exists in two large multi-protein complex, mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTORC1 consists of the three proteins mTOR, mLST8 and raptor and largely controls translation and cell growth in response to nutrients. mTORC2 consists of mTOR, mLST8 and rictor to control actin cytoskeleton dynamics. Although mutations or amplifications in mTOR have not been found in many human cancers, aberrant activation of mTOR signaling by deregulation of upstream and downstream regulators has frequently been observed in cancer, including SCCs [174,175]. Tumor suppressors, TSC2 and PTEN have loss of function mutations that lead to upregulation of mTOR activity. As described above, mTORC1 activity is elevated in epidermis of Akt transgenic mice and in wild type mice following topical treatment with diverse skin tumor promoters [170,171]. Activation of mTORC1 signaling is also induced by TPA treatment in cultured mouse primary keratinocytes and mouse epidermis (Rho and DiGiovanni, unpublished data). Furthermore, a known inhibitor of mTOR, rapamycin, significantly reduces TPA-induced epidermal cell proliferation and two-stage mouse skin carcinogenesis (Sandifer, Rho and DiGiovanni, unpublished data). Thus, mTOR signaling appears to also play an important role in mediating in part epidermal hyperplasia and proliferation during skin tumor promotion.

MAPK

MAPKs are a well-conserved signaling family of serine/threonine kinases regulating many intracellular processes such as cell proliferation, growth, differentiation, angiogenesis, migration, and survival [176]. The MAPK signal transduction pathway can be activated in response to a diverse range of extracellular stimuli including mitogens, growth factors, and cytokines. Upon stimulation, signaling via MAPKs is mediated by sequential activation of a protein kinase cascade, consisting of a MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK, e.g., B-Raf, Raf-1, A-Raf), a MAPK kinase (MAPKK, e.g., Mek-1, Mek-2), and a MAPK [177].

Six different MAPKs have been identified, including extacellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) 1/2, 3/4, 5, and 7/8, p38 α/β/γ (Erk-6)/d and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) 1/2/3 [178]. Dimerization between MAP kinase family members also occurs upon activation [179]. Activated Erks phosphorylate approximately 160 substrates, which participate in transcriptional regulation in the nucleus or cellular processes in the cytosol including protein translation and mitosis [176].

The components of the Ras/Raf/MEK/MAPK signaling pathway show significant functional redundancy as well as isoform-specific activities. Ras-deficient mice, (i.e., H-Ras-, N-Ras-, or H-Ras/N-Ras deficient mice), have no phenotypes, while K-Ras null mice are embryonic lethal [180–183]. A-Raf-knockout mice are viable, but both B-Raf-and Raf-1 null mice are embryonic lethal [184–186]. Mek-1 null mice are embryonic lethal at day 10.5, whereas Mek-2 deficient mice have no abnormal phenotype [187,188]. Knockout mice of the targets of Mek-1 and 2 (Erk-1 and Erk-2, respectively) exhibit discrepancy in phenotypes; Erk-2 knockout mice die at embryo, whereas Erk-1 knockout mice are viable, fertile, and of normal size [189–191].

In epithelial tissue, the Ras/Raf/MEK/MAPK signaling plays an important role in epidermal homeostasis as well as epidermal tumor development. Epidermal specific-conditional Mek-1 homozygous null mice exhibit reduced tumor formation with delayed tumor latency compared to wild-type mice using the DMBA/TPA treatment regimen, however, deletion of either Mek-1/2 MAPKK alone did not lead to an observable phenotype and no effects on two-stage skin carcinogenesis [192,193]. Erk-1 knockout mice have significant reduction in epidermal inflammation and proliferation in response to TPA treatment [194]. In addition, skin carcinogenesis by DMBA and TPA in Erk-1 null mice is inhibited [194]. On the other hand, overexpression of constitutively active oncogenic Ras, Raf-1, Mek-1, but not Mek-2 leads to epidermal proliferation and hyperplasia [195,196]. Transgenic mice expressing a constitutively active Mek-1 in epidermis under the control of human keratin 14 promoter (K14-Mek1 transgenic mice) exhibit elevated Mek protein and Erk-1/2 phosphorylation [197]. Skin of K14-Mek1 transgenic mice exhibited a moderately hyperplastic phenotype and these mice developed 100% incidence of well-differentiated papillomas [197]. In the multistage mouse skin carcinogenesis model, tumor initiation with DMBA leads to mutations in the Ha-ras gene that confers a selective growth advantage to skin keratinocytes during tumor promotion [1]. Approximately 90% of the skin papillomas induced by initiation with DMBA contain the H-Ras mutations at condon 61 [198]. Thus, activation of this pathway plays an important role throughout multistage epithelial carcinogenesis in mouse skin.

The activator protein-1 (AP-1) is a transcription factor composed of either homodimers of Jun protein family or heterodimers of Jun protein family and Fos protein family [199] and is rapidly activated by TPA [200]. AP1 can be phosphorylated by the Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) mediated by MAPK signaling cascade [201]. Upon activation, AP-1 binds to the TPA responsive element (TRE) and regulates genes involved in proliferation, differentiation, survival, angiogenesis, and transformation [202]. Previous studies have implicated activation of AP-1 in tumor promotion [200,203]. The expression of a dominant-negative form of c-Jun (TAM67) blocks skin tumor promoter-induced AP-1 activation by dimerization with other AP-1 components, resulting inhibition of transformation in mouse epidermal cells and tumor promotion in mouse skin carcinogenesis [204–207]. In TAM-67 transgenic mice (TAM-67 under the control of keratin 14 promoter) skin tumor promotion induced by TPA or okadaic acid is suppressed [206,207]. Moreover, expression of TAM67 in epidermis also inhibits UV-induced SCC formation in hairless mice, demonstrating that AP-1 activity plays a role in UV-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis [208]. Recently, several specific AP-1 target genes were found to be required for carcinogenesis [209–211], suggesting that AP-1 regulated genes might also be targets for cancer prevention.

The components of the Ras/Raf/MEK/MAPK signaling are frequently altered in many human cancers. [178,212]. MAPK pathway activation has been associated with about 30% of human cancers [213]. Although there has been conflicting evidence on the role of the Ras/Raf/MEK/MAPK pathway in proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, targeting this pathway most likely in combination with agents that target other pathways may represent a promising and desirable anticancer strategy.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Research in understanding biochemical and molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis has given insights into developing strategies to treat and to prevent cancer. Deregulated growth factor receptor signaling pathways is a common feature of most, if not all, epithelial cancers. Studies using the well-established mouse skin model of multistage epithelial carcinogenesis have revealed that a number of growth factor signaling pathways contribute to tumor development. Major RTKs involved in epithelial carcinogenesis include: the erbB family, especially the EGFR; the insulin/insulin-like receptor family, especially the IGF-IR and the c-met family, especially c-met. Furthermore, a number of downstream pathways including Src, Stat3, PI3K/Akt, mTOR and MAPK have been identified as potential targets for treatment of epithelial cancers. Data presented and reviewed in this article provide strong evidence that these pathways also represent viable targets for cancer prevention. In recent years, there have been intense efforts to identify and develop efficacious agents that interfere with such crucial signaling processes including small molecular compounds, naturally occurring compounds, dietary components, antisense oligonucleotides, siRNAs and shRNAs, etc. Moreover, several studies have shown that using combinations of agents that allow targeting multiple pathways may be more effective than single agents in terms of effectiveness (i.e., additive or synergistic effects) and safety (free of side effects). In conclusion, future research focusing on the modulation of growth factor signaling pathways by cancer preventive agents should provide promising new approaches for preventing or controlling epithelial cancers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NCI grant CA037111 and CA76520 (to J. DiGiovanni) and Funding as an Odyssey Fellow was supported by the Odyssey Program and The H-E-B Award for Scientific Achievement at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (to D. J. Kim).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel EL, Angel JM, Kiguchi K, DiGiovanni J. Multi-stage chemical carcinogenesis in mouse skin: fundamentals and applications. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(9):1350–1362. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiGiovanni J. Multistage carcinogenesis in mouse skin. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;54(1):63–128. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90051-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuspa S, Dlugosz A, Cheng C, et al. Role of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes in multistage carcinogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:908–958. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12399255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kemp CJ. Multistep skin cancer in mice as a model to study the evolution of cancer cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15(6):460–473. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer S, DiGiovanni J. Mechanisms of tumor promotion: epigenetic changes in cell signaling. Cancer Bul. 1995;47:456–463. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukhtar H. In: Skin Cancer: Mechanisms and Human Relevance. Mukhtar H, editor. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiGiovanni J. Multistage skin carcinogenesis. In: Ward J, Waalkes MP, editors. Carcinogenesis. Raven Press; New York, NY: 1994. pp. 265–299. (Target Organ Toxicology Series). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer SM, DiGiovanni J. Mechanisms of tumor promotion: epigenetic changesin cell signaling. Cancer Bul. 1995;47:456–463. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowden G, Finch J, Donann F, Krieg P. Molecular mechanisms involved in skin tumor initiation, promotion, and progression. In: Mukhtar H, editor. Skin Cancer: Mechanisms and Human Relevance. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1995. pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conti CJ, Aldaz CM, O'Connell J, Klein-Szanto AJ, Slaga TJ. Aneuploidy, an early event in mouse skin tumor development. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7(11):1845–1848. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.11.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwatsuki M, Mimori K, Yokobori T, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer development and its clinical significance. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(2):293–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darwiche N, Ryscavage A, Perez-Lorenzo R, et al. Expression profile of skin papillomas with high cancer risk displays a unique genetic signature that clusters with squamous cell carcinomas and predicts risk for malignant conversion. Oncogene. 2007;26(48):6885–6895. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yates RA, Nanney LB, Gates RE, King LE., Jr Epidermal growth factor and related growth factors. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30(10):687–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb02609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(2):127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicholson RI, Hutcheson IR, Harper ME, et al. Modulation of epidermal growth factor receptor in endocrine-resistant, oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8(3):175–182. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. Signal transduction by receptors with tyrosine kinase activity. Cell. 1990;61:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90801-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aaronson SA. Growth factors and cancer. Science. 1991;254:1146–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.1659742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinkas-Kramarski R, Soussan L, Waterman H, et al. Diversification of Neu differentiation factor and epidermal growth factor signaling by combinatorial receptor interactions. Embo J. 1996;15(10):2452–2467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ullrich A, Coussens L, Hayflick JS. Human epidermal growth factor receptor cDNA sequence and aberrant expression of the amplified gene in A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells. Nature. 1984;309:418–424. doi: 10.1038/309418a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih C, Shilo B-Z, Godfarb M, Dannenberg A, Weinberg R. Passage of phenotypes of chemically transformed cells via transfection of DNA and chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5714–5718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shih C, Padhy L, Murray M, Weinberg R. Transforming genes of carcinomas and neuroblastomas introduced into mouse fibroblasts. Nature. 1981;290:261–264. doi: 10.1038/290261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bargmann C, Hung M, Weinberg R. The neu oncogene encodes an epidermal growth factor receptor-related protein. Nature. 1986;319:226–230. doi: 10.1038/319226a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graus-Porta D, Beerli RR, Daly JM, Hynes NE. ErbB-2, the preferred heterodimerization partner of all ErbB receptors, is a mediator of lateral signaling. Embo J. 1997;16(7):1647–1655. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karunagaran D, Tzahar E, Beerli RR, et al. ErbB-2 is a common auxiliary subunit of NDF and EGF receptors: implications for breast cancer. Embo J. 1996;15(2):254–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Citri A, Skaria KB, Yarden Y. The deaf and the dumb: the biology of ErbB-2 and ErbB-3. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284(1):54–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xian W, Rosenberg MP, DiGiovanni J. Activation of erbB2 and c-src in phorbol ester-treated mouse epidermis: possible role in mouse skin tumor promotion. Oncogene. 1997;14(12):1435–1444. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoll SW, Kansra S, Peshick S, et al. Differential utilization and localization of ErbB receptor tyrosine kinases in skin compared to normal and malignant keratinocytes. Neoplasia. 2001;3(4):339–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panchal H, Wansbury O, Parry S, Ashworth A, Howard B. Neuregulin3 alters cell fate in the epidermis and mammary gland. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prickett TD, Agrawal NS, Wei X, et al. Analysis of the tyrosine kinome in melanoma reveals recurrent mutations in ERBB4. Nat Genet. 2009;41(10):1127–1132. doi: 10.1038/ng.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imamoto A, Beltran L, DiGiovanni J. Evidence of autocrine/paracrine growth stimulation by transforming growth factor α during the process of skin tumor promotion. Mol Carcinog. 1991;4:52–60. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940040109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiguchi K, Beltran LM, You J, Rho O, DiGiovanni J. Elevation of transforming growth factor-alpha mRNA and protein expression by diverse tumor promoters in SENCAR mouse epidermis. Mol Carcinog. 1995;12(4):225–235. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940120407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiguchi K, Beltran L, Rupp T, DiGiovanni J. Altered expression of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands in tumor promoter-treated mouse epidermis and in primary mouse skin tumors induced by an initiation-promotion protocol. Mol Carcinog. 1998;22(2):73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xian W, Kiguchi K, Imamoto A, Rupp T, Zilberstein A, DiGiovanni J. Activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by skin tumor promoters and in skin tumors from SENCAR mice. Cell Growth Diff. 1995;6:1447–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rho O, Beltran LM, Gimenez-Conti IB, DiGiovanni J. Altered expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and transforming growth factor-alpha during multistage skin carcinogenesis in SENCAR mice. Mol Carcinog. 1994;11(1):19–28. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940110105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vassar R, Hutton M, Fuchs E. Transgenic overexpression of transforming growth factor bypasses the need for c-Ha-ras mutations in mouse skin tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4643–4653. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dominey AM, Wang X-J, Gagne TA. Targeted overexpression of TGFα in the epidermis of transgenic mice elicits anomalous differentiation and spontaneous, self-regressing papillomas. Cell Growth Diff. 1993;4:1071–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jhappan C, Takayama H, Dickson R, Merlino G. Transgenic mice provide genetic evidence that transforming growth factor a promotes skin tumorigenesis via H-Ras-dependent and H-Ras-independent pathways. Cell Growth Diff. 1994;5:385–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang XJ, Greenhalgh DA, Eckhardt JN, Rothnagel JA, Roop D. Epidermal expression of TGF-alpha in transgenic mice: induction of spontaneous and TPA-induced papillomas via a mechanism independent of Ha-ras activation or overexpression. Mol Carcinog. 1994;10(1):15–22. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bol D, Kiguchi K, Beltran L, et al. Severe follicular hyperplasia and spontaneous papilloma formation in transgenic mice expressing the neu oncogene under the control of the bovine keratin 5 promoter. Mol Carcinog. 1998;21(1):2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casanova ML, Larcher F, Casanova B, et al. A critical role for ras-mediated, epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent angiogenesis in mouse skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62(12):3402–3407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Abaseri TB, Putta S, Hansen LA. Ultraviolet irradiation induces keratinocyte proliferation and epidermal hyperplasia through the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(2):225–231. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madson JG, Lynch DT, Tinkum KL, Putta SK, Hansen LA. Erbb2 regulates inflammation and proliferation in the skin after ultraviolet irradiation. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(4):1402–1414. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han CY, Lim SC, Choi HS, Kang KW. Induction of ErbB2 by ultraviolet A irradiation: potential role in malignant transformation of keratinocytes. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(3):502–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00718.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madson JG, Lynch DT, Svoboda J, et al. Erbb2 suppresses DNA damage-induced checkpoint activation and UV-induced mouse skin tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(6):2357–2366. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song JI, Grandis JR. STAT signaling in head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19(21):2489–2495. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berclaz G, Altermatt HJ, Rohrbach V, Siragusa A, Dreher E, Smith PD. EGFR dependent expression of STAT3 (but not STAT1) in breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2001;19(6):1155–1160. doi: 10.3892/ijo.19.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia R, Bowman TL, Niu G, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 by the Src and JAK tyrosine kinases participates in growth regulation of human breast carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2001;20(20):2499–2513. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minuto F, Del Monte P, Barreca A, et al. Evidence for an increased somatomedin-C/insulin-like growth factor 1 content in primary human lung tumors. Cancer Res. 1986;46:985–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yee D, Paik S, Lebovic G, et al. Analysis of insulin-like growth factor I gene expression in malignancy: evidence for a paracrine role in human breast cancer. Mol Endo. 1989;3:509–517. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-3-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kazer RR. Insulin resistance, insulin-like growth factor I and breast cancer: a hypothesis. Int J Cancer. 1995;62(4):403–406. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tricoli J, Rall L, Karakousis C, et al. Enhanced levels of insulin-like growth factor messenger RNA in human colon carcinomas and liposarcomas. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6169–6173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan JM, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, et al. Plasma insulin-like growth factor-I and prostate cancer risk: a prospective study. Science. 1998;279:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peyrat JP, Bonneterre J, Hecquet B, et al. Plasma insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) concentrations in human breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(4):492–497. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turner BC, Haffty BG, Narayanan L, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor overexpression mediates cellular radioresistance and local breast cancer recurrence after lumpectomy and radiation. Cancer Res. 1997;57(15):3079–3083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adams TE, Epa VC, Garrett TP, Ward CW. Structure and function of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57(7):1050–1093. doi: 10.1007/PL00000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grimberg A, Cohen P. Role of insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in growth control and carcinogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200004)183:1<1::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pollak M. Insulin-like growth factor physiology and cancer risk. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(10):1224–1228. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ullrich A, Gray A, Tam AW, et al. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor primary structure: comparison with insulin receptor suggests structural determinants that define functional specificity. Embo J. 1986;5(10):2503–2512. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lowe WL. Biological actions of the insulin-like growth factors. In: LeRoith D, editor. Insulin-Like Growth Factors: Molecular and Cellular Aspects. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1991. pp. 49–85. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones JI, Clemmons DR. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: biological actions. Endocrine Rev. 1995;16:3–34. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Werner H, Le Roith D. New concepts in regulation and function of the insulin-like growth factors: implications for understanding normal growth and neoplasia. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57(6):932–942. doi: 10.1007/PL00000735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parrizas M, LeRoith D. Insulin-like growth factor-1 inhibition of apoptosis is associated with increased expression of the bcl-xL gene product. Endocrinology. 1997;138(3):1355–1358. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.5103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liscovitch M, Cantley LC. Lipid second messengers. Cell. 1994;77(3):329–334. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kulik G, Klippel A, Weber M. Anti-apoptotic signaling by the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and AKT. Molec Cell Biol. 1997;17:1595–1606. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ahmed NN, Grimes HL, Bellacosa A, Chan TO, Tsichlis PN. Transduction of interleukin-2 antiapoptotic and proliferative signals via Akt protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(8):3627–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kennedy SG, Wagner AJ, Conzen SD, et al. The PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway delivers an anti-apoptotic signal. Genes Dev. 1997;11(6):701–713. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marte BM, Downward J. PKB/Akt: connecting phosphoinositide 3-kinase to cell survival and beyond. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22(9):355–358. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DiGiovanni J, Bol DK, Wilker E, et al. Constitutive expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 in epidermal basal cells of transgenic mice leads to spontaneous tumor promotion. Cancer Res. 2000;60(6):1561–1570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilker E, Lu J, Rho O, Carbajal S, Beltran L, DiGiovanni J. Role of PI3K/Akt signaling in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) skin tumor promotion. Mol Carcinog. 2005;44(2):137–145. doi: 10.1002/mc.20132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bol D, Kiguchi K, Gimenez-Conti I, Rupp T, DiGiovanni J. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-1 induces hyperplasia, dermal abnormalities, and spontaneous tumor formation in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1997;14:1725–1734. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moore T, Carbajal S, Beltran L, et al. Reduced susceptibility to two-stage skin carcinogenesis in mice with low circulating IGF-1 levels. Cancer Res. 2008;68(15):3680–3688. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dean M, Park M, Le Beau MM, et al. The human met oncogene is related to the tyrosine kinase oncogenes. Nature. 1985;318(6044):385–388. doi: 10.1038/318385a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakamura T, Nawa K, Ichihara A. Partial purification and characterization of hepatocyte growth factor from serum of hepatectomized rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;122(3):1450–1459. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bottaro DP, Rubin JS, Faletto DL, et al. Identification of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor as the c-met proto-oncogene product. Science. 1991;251(4995):802–804. doi: 10.1126/science.1846706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stoker M, Gherardi E, Perryman M, Gray J. Scatter factor is a fibroblast-derived modulator of epithelial cell mobility. Nature. 1987;327(6119):239–242. doi: 10.1038/327239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weidner KM, Behrens J, Vandekerckhove J, Birchmeier W. Scatter factor: molecular characteristics and effect on the invasiveness of epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1990;111(5 Pt 1):2097–2108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.5.2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gherardi E, Sandin S, Petoukhov MV, et al. Structural basis of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor and MET signalling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(11):4046–4051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W, Gherardi E, Vande Woude GF. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(12):915–925. doi: 10.1038/nrm1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bertotti A, Burbridge MF, Gastaldi S, et al. Only a subset of met-activated pathways are required to sustain oncogene addiction. Sci Signal. 2009;2(102):er11. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2102er11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Igawa T, Kanda S, Kanetake H, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor is a potent mitogen for cultured rabbit renal tubular epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;174(2):831–838. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91493-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kan M, Zhang GH, Zarnegar R, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor/hepatopoietin A stimulates the growth of rat kidney proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTE), rat nonparenchymal liver cells, human melanoma cells, mouse keratinocytes and stimulates anchorage-independent growth of SV-40 transformed RPTE. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;174(1):331–337. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90524-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsumoto K, Tajima H, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor is a potent stimulator of human melanocyte DNA synthesis and growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;176(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90887-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Olivero M, Rizzo M, Madeddu R, et al. Overexpression and activation of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor in human non-small-cell lung carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1996;74(12):1862–1868. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tuck AB, Park M, Sterns EE, Boag A, Elliott BE. Coexpression of hepatocyte growth factor and receptor (Met) in human breast carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1996;148(1):225–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nayeri F, Xu J, Abdiu A, et al. Autocrine production of biologically active hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) by injured human skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;43(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chmielowiec J, Borowiak M, Morkel M, et al. c-Met is essential for wound healing in the skin. J Cell Biol. 2007;177(1):151–162. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakamura Y, Matsubara D, Goto A, et al. Constitutive activation of c-Met is correlated with c-Met overexpression and dependent on cell-matrix adhesion in lung adenocarcinoma cell lines. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Otsuka T, Takayama H, Sharp R, et al. c-Met autocrine activation induces development of malignant melanoma and acquisition of the metastatic phenotype. Cancer Res. 1998;58(22):5157–5167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Noonan FP, Otsuka T, Bang S, Anver MR, Merlino G. Accelerated ultraviolet radiation-induced carcinogenesis in hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2000;60(14):3738–3743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mildner M, Eckhart L, Lengauer B, Tschachler E. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor inhibits UVB-induced apoptosis of human keratinocytes but not of keratinocyte-derived cell lines via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(16):14146–14152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mazzone M, Basilico C, Cavassa S, et al. An uncleavable form of pro-scatter factor suppresses tumor growth and dissemination in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(10):1418–1432. doi: 10.1172/JCI22235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316(5827):1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lai AZ, Abella JV, Park M. Crosstalk in Met receptor oncogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(10):542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ronsin C, Muscatelli F, Mattei MG, Breathnach R. A novel putative receptor protein tyrosine kinase of the met family. Oncogene. 1993;8(5):1195–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gaudino G, Follenzi A, Naldini L, et al. RON is a heterodimeric tyrosine kinase receptor activated by the HGF homologue MSP. EMBO J. 1994;13(15):3524–3532. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06659.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Follenzi A, Bakovic S, Gual P, Stella MC, Longati P, Comoglio PM. Cross-talk between the proto-oncogenes Met and Ron. Oncogene. 2000;19(27):3041–3049. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chan EL, Peace BE, Collins MH, Toney-Earley K, Waltz SE. Ron tyrosine kinase receptor regulates papilloma growth and malignant conversion in a murine model of skin carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24(3):479–488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brugge JS, Erikson RL. Identification of a transformation-specific antigen induced by an avian sarcoma virus. Nature. 1977;269:346–348. doi: 10.1038/269346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Collett M, Erikson E, Purchio AF, Brugge JS, Erikson RL. A normal cell protein similar in structure and function to the avian sarcoma virus transforming gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:3159–3163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Okada M, Nakagawa H. Identification of a novel protein tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates pp60c-src and regulates its activity in neonatal rat brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;154:796–802. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Brickell PM. The p60csrc family of protein-tyrosine kinases: structure, regulation, and function. Crit Rev Oncogenesis. 1992;3:401–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brown MT, Cooper JA. Regulation, substrates and functions of src. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1996;1287:121–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Scaltriti M, Baselga J. The epidermal growth factor receptor pathway: a model for targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(18):5268–5272. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yeatman TJ. A renaissance for SRC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(6):470–480. doi: 10.1038/nrc1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Summy JM, Gallick GE. Treatment for advanced tumors: SRC reclaims center stage. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(5):1398–1401. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Courtneidge SA. Role of Src in signal transduction pathways. The Jubilee Lecture. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30(2):11–17. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Irby RB, Yeatman TJ. Role of Src expression and activation in human cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19(49):5636–5642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wheeler DL, Iida M, Dunn EF. The role of Src in solid tumors. Oncologist. 2009;14(7):667–678. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Summy JM, Gallick GE. Src family kinases in tumor progression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22(4):337–358. doi: 10.1023/a:1023772912750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Barnekow A, Paul E, Schartl M. Expression of the c-src protooncogene in human skin tumors. Cancer Res. 1987;47(1):235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.O'Connor TJ, Bjorge JD, Cheng HC, Wang JH, Fujita DJ. Mechanism of c-SRC activation in human melanocytes: elevated level of protein tyrosine phosphatase activity directed against the carboxy-terminal regulatory tyrosine. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6(2):123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Matsumoto T, Jiang J, Kiguchi K, et al. Targeted expression of c-Src in epidermal basal cells leads to enhanced skin tumor promotion, malignant progression, and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2003;63(16):4819–4828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Matsumoto T, Kiguchi K, Jiang J, et al. Development of transgenic mice that inducibly express an active form of c-Src in the epidermis. Mol Carcinog. 2004;40(4):189–200. doi: 10.1002/mc.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Matsumoto T, Jiang J, Kiguchi K, et al. Overexpression of a constitutively active form of c-src in skin epidermis increases sensitivity to tumor promotion by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Mol Carcinog. 2002;33(3):146–155. doi: 10.1002/mc.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Darnell JE., Jr STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277(5332):1630–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Levy DE, Lee CK. What does Stat3 do? J Clin Invest. 2002;109(9):1143–1148. doi: 10.1172/JCI15650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Akira S. Functional roles of STAT family proteins: lessons from knockout mice. Stem Cells. 1999;17(3):138–146. doi: 10.1002/stem.170138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kisseleva T, Bhattacharya S, Braunstein J, Schindler CW. Signaling through the JAK/STAT pathway, recent advances and future challenges. Gene. 2002;285(1–2):1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Haura EB, Turkson J, Jove R. Mechanisms of disease: Insights into the emerging role of signal transducers and activators of transcription in cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2(6):315–324. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kiuchi N, Nakajima K, Ichiba M, et al. STAT3 is required for the gp130-mediated full activation of the c-myc gene. J Exp Med. 1999;189(1):63–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sinibaldi D, Wharton W, Turkson J, Bowman T, Pledger WJ, Jove R. Induction of p21WAF1/CIP1 and cyclin D1 expression by the Src oncoprotein in mouse fibroblasts: role of activated STAT3 signaling. Oncogene. 2000;19(48):5419–5427. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Leslie K, Lang C, Devgan G, et al. Cyclin D1 is transcriptionally regulated by and required for transformation by activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Cancer Res. 2006;66(5):2544–2552. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Epling-Burnette PK, Liu JH, Catlett-Falcone R, et al. Inhibition of STAT3 signaling leads to apoptosis of leukemic large granular lymphocytes and decreased Mcl-1 expression. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(3):351–362. doi: 10.1172/JCI9940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]