Abstract

Factors that influence the activity of prefrontal cortex (PFC) pyramidal neurons are likely to play an important role in working memory function. One such factor may be the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Here we investigate the hypothesis that metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs)-mediated waves of internally released Ca2+ can regulate the intrinsic excitability and firing patterns of PFC pyramidal neurons. Synaptic or focal pharmacological activation of mGluRs triggered Ca2+waves in the dendrites and somata of layer V medial PFC pyramidal neurons. These Ca2+ waves often evoked a transient SK-mediated hyperpolarization followed by a prolonged depolarization that respectively decreased and increased neuronal excitability. Generation of the hyperpolarization depended on whether the Ca2+wave invaded or came near to the soma. The depolarization also depended on the extent of Ca2+ wave propagation. We tested factors that influence the propagation of Ca2+ waves into the soma. Stimulating more synapses, increasing inositol trisphosphate concentration near the soma, and priming with physiological trains of action potentials all enhanced the amplitude and likelihood of evoking somatic Ca2+waves. These results suggest that mGluR-mediated Ca2+waves may regulate firing patterns of PFC pyramidal neurons engaged by working memory, particularly under conditions that favor the propagation of Ca2+ waves into the soma.

Keywords: calcium release; inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; neocortex/physiology; SK channels; slow afterdepolarization

Introduction

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays an integral role in higher cognitive function (Fuster 1973; Goldman-Rakic 1995). Fundamental to this role is the capacity for PFC to mediate the short-term storage of mental representations and to process those representations. This ability is commonly referred to as working memory. When information is first stored in working memory, the firing rates of some PFC neurons increase, and their increased firing rates persist until the information is no longer needed (Fuster 1973; Funahashi et al. 1989; Narayanan and Laubach 2006). Disruption of neuronal activity in the PFC leads to disruption of working memory performance (Sawaguchi and Goldman-Rakic 1991; Murphy et al. 1996; Zahrt et al. 1997). Although much progress has been made in understanding the local circuit interactions that underlie working memory–related patterns of activity in neocortex, relatively little is known about how glutamatergic synaptic transmission affects intrinsic cellular properties during these processes. Of particular interest is how the activation of postsynaptic group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) and consequent Gq protein–mediated events such as the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and Ca2+ waves contribute to the regulation of excitability of PFC pyramidal neurons.

Few studies have examined the basic properties of mGluR-mediated internal Ca2+ release in neocortical neurons (Larkum et al. 2003), much less the functional consequences of internal Ca2+ release and Ca2+ waves. Synaptic activation of postsynaptic mGluRs in particular, and Gq proteins in general, can lead to the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores through the activation of inositol trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) located primarily on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in pyramidal neurons of the neocortex and hippocampus (Nakamura et al. 1999, 2002; Kapur et al. 2001; Power and Sah 2002; Larkum et al. 2003; Watanabe et al. 2006) and in dopamine neurons of the midbrain (Morikawa et al. 2003). Neurotransmitters such as glutamate and acetylcholine are coupled via Gq proteins to phospholipase C, which cleaves phosphatidyl-inositol bisphosphate to produce diacylglycerol and inositol trisphosphate (IP3). IP3 binds to IP3Rs, causing their Ca2+-permeable channels to open and allowing Ca2+ to diffuse from the ER into the cytosol (reviewed in Berridge 1998). Ca2+ can also be released from the ER via ryanodine receptors, but these receptors have no apparent role in synaptically elicited internal Ca2+ release in pyramidal neurons (Nakamura et al. 1999; Kapur et al. 2001; Larkum et al. 2003).

Consistent with a role for intracellular Ca2+ waves in regulating the activity of neurons in PFC, previous studies suggest that internal Ca2+ release may influence the firing patterns of pyramidal neurons (Yamamoto et al. 2002; Stutzmann et al. 2003; Yamada et al. 2004; Gulledge and Stuart 2005; Gulledge et al. 2006) and midbrain dopamine neurons (Morikawa et al. 2000, 2003). For example, internal Ca2+ release and Ca2+ waves triggered by mGluR activation (Morikawa et al. 2003) in midbrain dopamine neurons or directly by photolysis of caged IP3 in PFC neurons (Stutzmann et al. 2003) activate an outward current that inhibits action potential generation. Whether or not such inhibition occurs in PFC neurons after synaptic activation of mGluRs has not been tested.

Here we report that synaptic and focal pharmacological activation of mGluRs can trigger Ca2+ waves in layer V PFC pyramidal neurons and that these waves can result in an outward current followed by an inward current that respectively decrease and increase neuronal excitability. We also find that Ca2+ waves must propagate into or close to the soma to produce the outward current. Finally, we show that Ca2+ wave propagation into the soma can be facilitated by stimulating more synapses, by increasing the amount of IP3 mobilized near the soma, and through priming with physiologically realistic spike trains. Our results suggest that glutamate-triggered Ca2+ waves may play an important role in regulating the firing patterns of PFC pyramidal neurons and set the stage for understanding under what circumstances internal Ca2+ release may contribute to the regulation of working memory processes.

Materials and Methods

Slice Preparation

Brain slices were prepared from P18–49 male Sprague–Dawley rats (mean age = P26; 5 animals < P21 and 6 animals > P41; n = 140 animals) and 7- to 14-week-old ferrets (n = 16 animals) in adherence with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Yale University School of Medicine and consistent with experimental procedures outlined in National Institutes of Health publication 91-3207, Preparation and Maintenance of Higher Animals During Neuroscience Experiments. Ferret slices were prepared as described previously (Gao and Goldman-Rakic 2006). Rats were injected intraperitoneally with anesthetic (125 mg/kg ketamine, 6.5 mg/kg xylazine, and 1.25 mg/kg acepromazine) and were decapitated when no longer responsive to a foot pinch. Brains were quickly removed into ice-cold dissecting solution continuously bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 and containing (in mM) 87 NaCl, 75 sucrose, 10 dextrose, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 7.0 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, adjusted with sucrose to 295–305 mOsm. Brains were then blocked and glued to a precooled slicing chamber insert. Coronal slices (320 μm) including the prelimbic, infralimbic, and cingulate cortices anterior to the genu of the corpus callosum (Paxinos and Watson 1998) were cut using a Vibratome in a peltier-cooled slicing chamber filled with dissecting solution and maintained at a temperature between 0.5 °C and 3.0 °C. After cutting, rat and ferret slices were incubated for 10–20 min in 34–37 °C dissecting solution and then transferred to 34–37 °C recording artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) and allowed to cool to room temperature for at least 1 h prior to recording. Standard recording ACSF contained (in mM) the following: 124 NaCl, 10 dextrose, 2.5 NaHCO3, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 2.0 MgCl2, and 2.0 CaCl2, adjusted with sucrose to 295–300 mOsm. During synaptic stimulation experiments where γ-aminobutyric acid A (GABAA) and GABAB antagonists were used, MgCl2 and CaCl2 concentrations were increased to 4.0 mM and 5.0 mM, respectively, to decrease excitability and lower the possibility of polysynaptic input onto the recorded neuron.

Whole-Cell Recordings and Solutions

For recording, individual slices were transferred to a custom-made recording chamber (volume ~1 mL) that was continuously perfused with 95% O2/5% CO2–saturated recording ACSF (flow rate 1–2 mL/min) and maintained at 31–34 °C. Visualized whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed using infrared differential interference contrast microscopy on an upright microscope (Zeiss Axioskop or Olympus BX51WI) with patch pipettes (2–5 MΩ) pulled from 2.0-mm outer diameter thick-walled borosilicate glass with filament. The pipette solution contained (in mM) the following: 134 KMeOSO3, 10 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 3.0 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 4.0 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Na-GTP, 5.0 K2-phosphocreatine, 5.0 Na2-phosphocreatine, pH adjusted with KOH to 7.52–7.55, 285–290 mOsm, as well as 50 units/mL creatine phosphokinase, 5–15 μM Alexa 488 or Alexa 568 for visualization of filled processes under fluorescent illumination, and one of the following Ca2+ indicator dyes, as indicated, 100 μM bis-fura-2, 75–100 μM fluo-4, or 100 μM Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-2. KMeOSO3, Mg-ATP, Na-GTP, Na2-phosphocreatine, and creatine phosphokinase were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO). K2-phosphocreatine was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Alexa 488, Alexa 568, bis-fura-2, fluo-4, and Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-2 were purchased from Molecular Probes/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). For uncaging experiments, the internal solution was supplemented with 50–100 μM D-myo-inositol-1,4,5 triphosphate, p(4(5)-(1-nitrophenyl) ethyl) ester, tris (trimethyl ammonium) salt (NPE-caged IP3; Calbiochem/EMD Biosciences). Electrical signals were acquired at 1 kHz using an SEC 05LX amplifier (npi electronic, Tamm, Germany) in bridge or discontinuous voltage-clamp mode, digitized, and analyzed on- and offline using custom software developed in IGOR Pro (WaveMetrics; Portland, OR). Whole-cell series resistance ranged from 8 to 30 MΩ and was compensated for by adjusting the bridge balance. Data were not corrected for junction potential (~10 mV). Layer V pyramidal neurons were selected from a region approximately halfway between the subcortical white matter and the pial surface and were identified by their large, ovoid- or pyramidal-shaped somata and prominent apical dendrites. Cells were held at approximately −65 mV for the duration of the experiment, except during periods of stimulation, where the holding potential was typically adjusted to −55 mV for a short time beginning about 5 s before and ending about 5 s after the 5- to 10-s stimulation period. This was done to increase the amplitude of the hyperpolarization that usually accompanied Ca2+ waves. The 280 rat and 33 ferret neurons included in this study had an average resting membrane potential of −62.1 ± 0.3 mV (cells were discarded if greater than −50 mV) and an average input resistance of 96.7 ± 2.3 MΩ, exhibited spike frequency adaptation in response to prolonged (300 ms) supra-threshold current injection, and had firing patterns consistent with the regular spiking phenotype described by McCormick et al. (1985).

Ca2+ Fluorescence Imaging

Ca2+ indicator dye diffused into the recorded neuron via the patch pipette. Bis-fura-2 (100 μm) was used in experiments involving afferent stimulation or pressure application of mGluR agonist, whereas 75–100 μm fluo-4 or 100 μm Oregon Green BAPTA-2 was used with photolysis of NPE-caged IP3. A different Ca2+ indicator was used during IP3 uncaging experiments because the excitation spectrum of unbound bis-fura-2 (peak excitation at 380 nm) falls within the spectrum of wavelengths used for photolysis of NPE-caged IP3 (320–400 nm). Dye fluorescence was imaged using a cooled CCD camera (Quantix 57 or Cascade 512B; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Images were collected at 50 or 25 Hz with 5 × 5 or 4 × 4 pixel binning. Epifluorescence illumination was provided by a 150 W xenon bulb (Optiquip, Highland Mills, NY). Relative changes in the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) were quantified as changes in ΔF/F, where F represents baseline fluorescence intensity prior to stimulation and ΔF represents the magnitude of fluorescence change during activity. Data representing tissue autofluorescence were collected at the end of each experiment from a region of the slice close to the dye-filled cell but not containing any of its processes. Autofluorescence data were routinely, though not always, subtracted from raw fluorescence data prior to calculation of ΔF/F. All optical data were smoothed with 5-frame averaging. Optical data were not corrected for dye bleaching. Relative changes in fluorescence are displayed using 2 methods. In one method, colored optical traces correspond to changes in fluorescence over time in regions of interest over the soma and dendritic processes. In the other method, a variation on the pseudo-linescan, changes in fluorescence along a line are displayed in pseudocolor as a function of time (Nakamura et al. 2000).

Stimulation of Synaptic Afferents

Synaptic afferents were electrically stimulated using a glass microelectrode (5–10 μm tip diameter) with a fine tungsten rod glued to its side. Stimulation electrodes were filled with standard recording ACSF and placed approximately 20–60 μm away from the recorded cell body and approximately 20–50 μm to one side of its primary apical dendrite. This stimulation location was chosen in an effort to activate synapses on the plexus of oblique dendrites that branch from the primary proximal apical dendrite and receive input from layer II/III PFC neurons and from the intralaminar nucleus of the thalamus (Berendse and Groenewegen 1991). Such proximal stimulation resulted in the generation of Ca2+ waves that could propagate into the soma and could lead to changes in membrane potential. In some cases, we stimulated more distally (~200 μm from the soma; see Larkum et al. 2003), but under these circumstances, Ca2+ waves failed to propagate into the soma (data not shown). Trains of unipolar pulses (20–50 stimuli, 15–150 μA, 50–100 Hz, 0.1 ms duration) were delivered to elicit internal Ca2+ release. A Ca2+ transient always accompanied synaptic trains that gave rise to action potentials. This transient exhibited a rapidly rising and decaying component presumably deriving from depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs). Synaptic stimulation often also triggered a longer lasting component with delayed onset and propensity to travel as a wave along the dendrite and within the soma. Ca2+ transients with late onset, slow decay, and continued rise after the end of the stimulation were attributed to internal Ca2+ release, whereas exponentially decaying transients whose on- and offset correlated with action potentials were attributed to voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space.

Pressure Application of Agonist

For focal agonist application (puffing), a 2–5 MΩ pipette was filled with the group I/II mGluR agonist (±)-1-aminocyclopentane-trans-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (ACPD, 400 μM; Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO) in standard recording solution or in recording solution where 10 mM HEPES replaced 10 mM dextrose and positioned approximately 20–60 μm away from the soma and <10 μm to one side of the primary apical dendrite. Brief applications of pressure (10–200 ms, 8–20 p.s.i.) nearly always resulted in brief movement of the tissue near the pressure application pipette. Such movements appear as an artifact in the optical signal that is correlated in time with pressure ejection of agonist.

Photolysis of NPE-Caged IP3

NPE-caged IP3 diffused into the recorded neuron via the patch pipette. Photolysis of NPE-caged IP3 (uncaging) was accomplished with 50–500 ms flashes of UV light (320–400 nm) produced by a 100 W mercury lamp (HBO ebq 100 isolated; Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY). The photolysis beam was directed onto the soma or proximal apical dendrite of the recorded cell using a custom-made fiber optic spot illumination system (Rapp OptoElectronic GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) fitted to the aperture stop port in the epi-illumination pathway of an Olympus BX51WI microscope. Exposure of the slice to the photolysis beam sometimes resulted in a large optical artifact whose on- and offset correlated in time with the opening and closing of the spot illumination shutter. This artifact appeared to be due to tissue autofluorescence, as it was observed even when the beam was aimed at locations away from the dye-filled cell. Because the artifact did not interfere with interpretation of the data, it was only corrected for in data selected for figures as indicated. Photolysis beam size was estimated from images of tissue autofluorescence to be ~20 μm.

Pharmacology

In some experiments, 50 mM BAPTA (Sigma Aldrich) or cesium methanesulfonate (Sigma Aldrich) replaced equiosmolar concentrations of KMeOSO3 in the patch pipette solution. All other drugs were bath applied, as indicated. The following drugs were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (stock solution in parentheses): 100 μM 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane (2-APB; 10 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]), 50 μM DL-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (dl-APV; 25 mM in H2O), 1 μM CGP55845 (20 mM in DMSO), 100 μM CPCCOEt (100 mM in DMSO), 50 μM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; 100 mM in DMSO), 20 μM 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX; 40 mM in DMSO), 100 μM 2-methyl-6-(phenylethyl) pyridine hydrochloride (DNQX; 40 mM in DMSO), 15 μM ryanodine (20 mM in DMSO), and 10 μM SR95531 (gabazine; 10 mM in H2O). The following drugs were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (stock solution in parentheses): 100 nM apamin (0.25 mM in H2O), 1 μM atropine (5 mM in H2O), 100 nM charybdotoxin (23.8 μM in H2O), 250 μM flufenamate (83 mM in DMSO), and 10 mM tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA; made fresh in recording ACSF).

Data Analysis

Input resistance was calculated from the average voltage response to a train of 3 hyperpolarizing current pulses (150 pA, 300 ms duration, at 0.3 Hz). Voltage responses were measured during the last 20 ms of each 300-ms square-pulse current injection and compared with baseline membrane potential in the 20 ms prior to current injection. The amplitude of internal Ca2+ release in a given region of interest was quantified using the maximum ΔF/F and was calculated as the difference between the peak ΔF/F following stimulation and the average baseline ΔF/F prior to stimulation. The onset time of the internal Ca2+ release in a given region of interest was defined as the time of the most negative value in the first derivative of the associated optical data. The magnitude of the release-associated hyperpolarization was calculated as the difference between the minimum membrane potential after stimulation and the average membrane potential prior to stimulation. The onset time of the hyperpolarization was defined as the time of the most negative value in the smoothed first derivative of the smoothed electrical data. Electrical data and differentiated electrical data were smoothed by calculating a moving average using a square window 50–100 ms wide, and this smoothing was repeated 10 times. The magnitude of the release-associated depolarization was measured from the difference between the average membrane potential prior to stimulation and the average membrane potential after the evoked hyperpolarization had subsided, typically between 3 and 5 s after stimulus delivery. Neurons were judged to exhibit a hyperpolarization or depolarization if the appropriate change in membrane potential was both greater than the level of the noise and observed at least twice.

Statistics

As there were no obvious differences in responses across ages or species, data were pooled. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was tested using unpaired Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney (WMW) ranked sum tests, unpaired Student’s t-tests assuming unequal variance (t-test), paired Student’s t-tests (paired t-test), or Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) tests, as appropriate. Statistical correlations were evaluated using linear regression analyses.

Results

The goal of this study was to examine how mGluR-mediated internal Ca2+ release and Ca2+ waves may contribute to the regulation of intrinsic excitability and patterns of activity in PFC neurons. To this end, we investigated the characteristics of Ca2+ waves and their consequences on membrane potential and excitability in layer V pyramidal neurons of the medial PFC (mPFC) and also what influences the propagation of Ca2+ waves into the soma. Ca2+ waves were elicited using 3 different techniques, depending on the question being addressed: stimulation of synaptic afferents, focal pressure application of an mGluR agonist (ACPD), and focal photolysis of NPE-caged IP3.

Internal Ca2+ Release and Ca2+ Waves in Layer V mPFC Pyramidal Neurons

Synaptically Elicited, mGluR-Mediated Internal Ca2+ Release

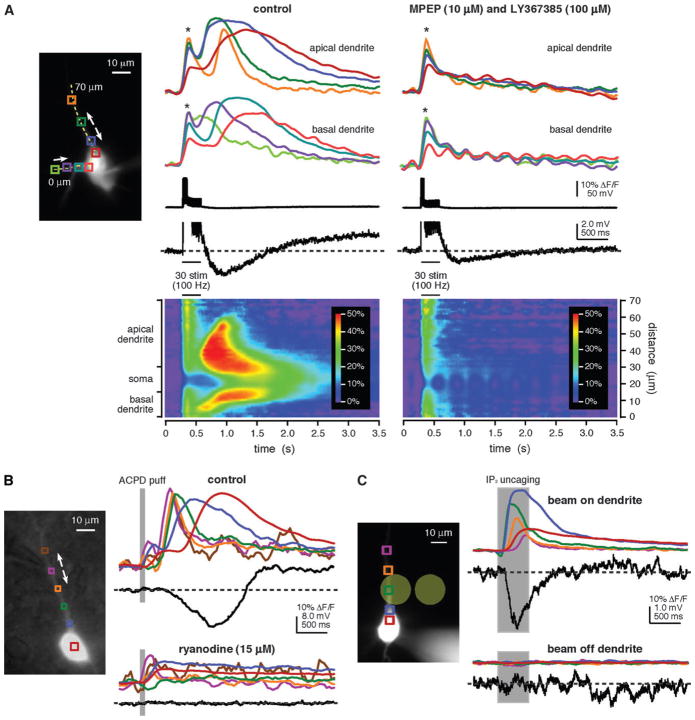

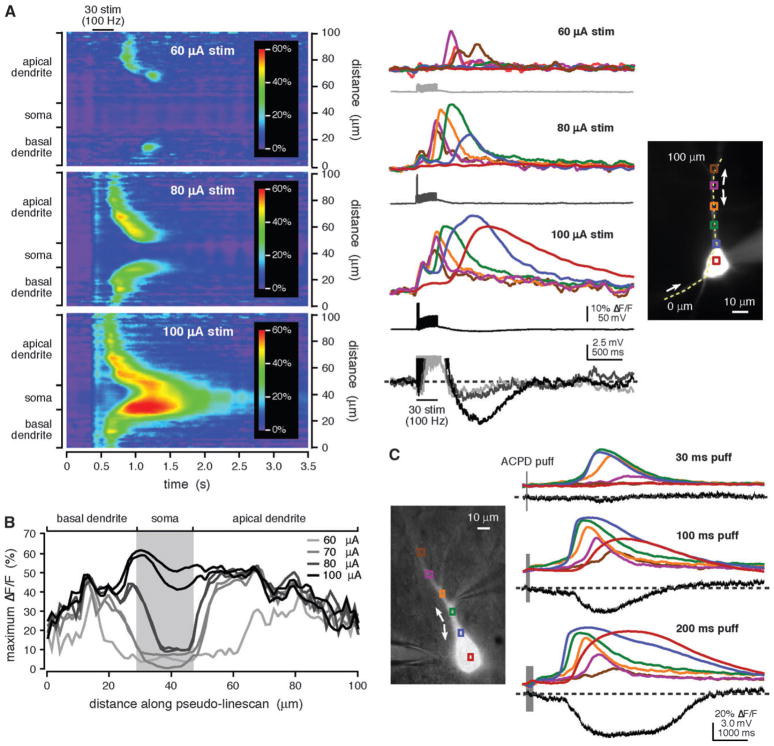

As described previously for hippocampal and neocortical pyramidal neurons (Nakamura et al. 1999, 2002; Kapur et al. 2001; Larkum et al. 2003; Watanabe et al. 2006), brief trains of synaptic stimulation (20–50 pulses at 50–100 Hz) evoked internal Ca2+ release and consequent Ca2+ waves in layer V rat mPFC pyramidal neurons (n = 63). Ca2+ waves were typically observed in the primary apical dendrite (n = 55/63) but were also observed in the basal dendrites (n = 23/63). The waves propagated bidirectionally along the dendrites and frequently invaded the soma. Synaptic stimulation evoked Ca2+ waves in the presence of antagonists to NMDA receptors (DL-APV, 50 μM; n = 17) and GABAA and GABAB receptors (gabazine, 10 μM; CGP55845, 1 μM; n = 16). In many cases, the stimuli that triggered Ca2+ waves also evoked action potentials. In these cases, there were 2 components to the Ca2+ response: a [Ca2+]i rise due to presumed influx of Ca2+ through VGCCs and a propagating Ca2+ wave (Fig. 1A). These 2 components could be distinguished based on their temporal, spatial, and pharmacological properties. Presumed VGCC-dependent [Ca2+]i rises coincided with action potentials and were relatively simultaneous in all regions of the soma and primary apical dendrite. Waves of rising [Ca2+]i, on the other hand, initiated after a delay, exhibited continued rise after the stimulation was completed, and had a prolonged duration and slow decay (Nakamura et al. 1999; Kapur et al. 2001; Larkum et al. 2003). Furthermore, consistent with studies showing that synaptically elicited internal Ca2+ release in pyramidal neurons is due to mGluR activation and depends on IP3R activation (Nakamura et al. 1999, 2002; Kapur et al. 2001; Larkum et al. 2003), Ca2+ waves were blocked by the group I mGluR antagonists MPEP and LY367385 (10 and 100 μM, respectively; n = 8; Fig. 1A) and by the IP3R antagonist 2-APB (100 μM; n = 3; data not shown).

Figure 1.

Multiple methods for eliciting propagating Ca2+ waves in mPFC layer V pyramidal neurons. (A) Synaptically evoked internal Ca2+ release. Left, Alexa fluorescence image of a bis-fura-2–filled rat neuron (the patch pipette tip is visible on the soma). Colored boxes indicate regions of interest (ROIs) corresponding to the optical traces on right. The dashed yellow line identifies the position of the pseudo-linescan. Right, optical and electrical traces and pseudo-linescans show fluorescence changes and electrical responses to synaptic stimulation (50 pulses at 100 Hz) under control conditions and following bath application of the group I mGluR antagonists MPEP (10 μM) and LY367385 (100 μM). Stimulation under control conditions triggered EPSPs and 5 action potentials. These were followed by a brief membrane hyperpolarization and a prolonged membrane depolarization. [Ca2+]i rises associated with action potentials, which are marked by asterisks, occurred almost simultaneously in all regions of the soma and dendrites. Ca2+ waves initiated after a delay in both the primary apical dendrite (near the blue and green regions) and in a basal dendrite (near the lime-colored region) and propagated into the soma. Stimulation following bath application of mGluR antagonists triggered 5 action potentials and associated rises in [Ca2+]i, but it neither triggered Ca2+ waves nor gave rise to a hyperpolarization or depolarization. The recording ACSF contained DL-APV (50 μM), gabazine (10 μM), and CGP55845 (1 μM) to block NMDA, GABAA, and GABAB receptors, respectively, throughout this experiment. (B) Pharmacologically elicited internal Ca2+ release. Left, Alexa fluorescence image of a bis-fura-2–filled rat neuron with differential interference contrast overlay showing the position of the pressure application pipette adjacent to the primary apical dendrite. Right, ACPD puffs (80 ms) triggered bidirectionally propagating Ca2+ waves that invaded the soma and were accompanied by a hyperpolarization and a depolarization. Puff-evoked rises in [Ca2+]i, the hyperpolarization, and the depolarization were all absent after bath application of ryanodine (15 μM) to deplete internal stores. (C) Internal Ca2+ release triggered by focal photolysis of NPE-caged IP3. Left, Alexa fluorescence image of a rat neuron filled with fluo-4 and 97 μM NPE-caged IP3. The pale yellow circles show the approximate size (~20 μm diameter) and positions of the UV uncaging beam. Right, brief UV flashes (500 ms) triggered bidirectionally propagating Ca2+ waves and a transient hyperpolarization when the uncaging beam was directed at the primary apical dendrite. Neither a release nor a hyperpolarization was observed when the beam was directed at an adjacent region of the slice approximately 27 μm away from the cell. The top set of traces represents an average of 2 trials. The bottom set of traces represents data from a single trial. Optical data shown in this figure were corrected for the tissue autofluorescence that arises from exposure to the uncaging beam.

Pharmacological Activation of mGluRs Triggers Propagating Waves of Internal Ca2+ Release

We next tested whether focally applied ACPD, a broad-spectrum mGluR agonist, could elicit internal Ca2+ release and Ca2+ waves. Consistent with other reports (Jaffe and Brown 1994; Kapur et al. 2001; Morikawa et al. 2003), brief “puffs” of ACPD (400 μM, 8–20 p.s.i., 20–200 ms) onto the primary apical dendrites of rat and ferret layer V pyramidal neurons triggered rises in [Ca2+]i that displayed the characteristics of propagating internal Ca2+ release (n = 180; Fig. 1B). Pharmacologically evoked Ca2+ waves originated near the pressure application pipette tip, propagated bidirectionally, and frequently invaded the soma. ACPD-elicited rises in [Ca2+]i were not affected by antagonists of ionotropic glutamate receptors (20 μM DNQX to block AMPARs and 50 μM DL-APV to block NMDARs; n = 9), GABAA and GABAB receptors (10 μM gabazine and 50μM CGP55845, respectively; n = 9), or muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs; atropine, 1 mM; n = 20). ACPD-evoked waves of internal Ca2+ release were blocked by depletion of internal stores with ryanodine (15 μM; n = 11; Fig. 1B) or CPA (50 μM; n = 6), by antagonism of IP3Rs with 2-APB (100 μM; n = 9), or by chelation of cytosolic Ca2+ with BAPTA (50 mM) in the patch pipette solution (n = 5). These results show that waves of internal Ca2+ release triggered by direct mGluR activation are, in every aspect examined, similar to Ca2+ waves triggered by synaptic stimulation.

Photolysis of NPE-Caged IP3 Elicits Internal Ca2+ Release

We also elicited internal Ca2+ release by focal photolysis of NPE-caged IP3 (Finch and Augustine 1998; Morikawa et al. 2000; Power and Sah 2002, 2005; Stutzmann et al. 2003). This method allowed us to bypass the activation of synapses, mGluRs, and the complex signal transduction mechanisms involved in the generation of internal Ca2+ release with our other methods. Also, through uncaging, we were able to dissociate the consequences of IP3 mobilization from the effects of mGluR activation. Internal Ca2+ release was triggered in rat neurons filled with NPE-caged IP3 (50–100 μM) via the patch pipette and exposed to brief flashes of UV light (330–400 nm, 30–500 ms) from a focused beam (~20 μm diameter) directed at their primary apical dendrites or somata (n = 41/44; Fig. 1C). Rises in [Ca2+]i triggered by photolysis of NPE-caged IP3 typically initiated at the site of the uncaging beam. When triggered in the primary apical dendrite, [Ca2+]i rises spread as waves in both directions along the dendrite and sometimes invaded the soma. Flashes that elicited internal Ca2+ release when the photolysis beam was aimed at the apical dendrite did not evoke [Ca2+]i rises when the beam was moved at least 15 μm off the dendrite (n = 5; Fig. 1C). Flashes never triggered a change in [Ca2+]i in cells without NPE-caged IP3 (n = 3; data not shown).

Internal Ca2+ Release Evokes a Hyperpolarization Followed by a Depolarization

Internal Ca2+ release was often accompanied by a membrane hyperpolarization (0.6–14.8 mV) (Jaffe and Brown 1994; Morikawa et al. 2000, 2003; Stutzmann et al. 2003; Rae and Irving 2004; Gulledge and Stuart 2005; Gulledge et al. 2006). In some cases, we also observed a sustained membrane depolarization (0.4–11.0 mV). Unlike the hyperpolarization, which generally lasted from 0.2 to 3.0 s and was highly correlated with the duration of rises in [Ca2+]i, the depolarization persisted considerably longer than the rise in [Ca2+]i (Congar et al. 1997; Rae and Irving 2004; Gulledge and Stuart 2005; Gulledge et al. 2006). In 3/6 cells for which extended recordings were made, the depolarization did not decay to less than 37% of its peak magnitude after 50 s (5–81% of peak depolarization remaining after 50 s; n = 6). Although the depolarization usually followed the hyperpolarization, it was occasionally observed in the absence of a hyperpolarization (Rae and Irving 2004; Gulledge and Stuart 2005). The hyperpolarization could be evoked with all 3 stimulation methods, suggesting that it was due to IP3R activation and internal Ca2+ release (synaptic stimulation, n = 17/46; puffing, n = 144/179; uncaging, n = 36/39; e.g., Fig. 1A–C). The depolarization, however, was elicited only when internal Ca2+ release was triggered by synaptic stimulation or focal ACPD application and not when internal Ca2+ release was triggered by IP3 uncaging (synaptic stimulation, n = 19/55; puffing, n = 149/178; uncaging, n = 0/39; e.g., Fig. 1A–C). Neither the hyperpolarization nor the depolarization was sensitive to inhibitors of GABAA/B receptors, mAChRs, or ionotropic glutamate receptors (summarized in Table 1), yet both were blocked by inhibitors of internal Ca2+ release and mGluRs (Fig. 1; summarized in Table 2). These data suggest that generation of the hyperpolarization requires IP3R stimulation and subsequent internal Ca2+ release, whereas the depolarization requires both mGluR activation and an IP3R-mediated rise in [Ca2+]i.

Table 1.

Generation of the internal Ca2+ release–associated hyperpolarization and depolarization did not require activation of GABAA and GABAB, muscarinic acetylcholine, or NMDA and AMPA receptors

| Drugs Applied | Hyperpolarization Present |

Depolarization Present |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Stimulation | puffing | Uncaging | Synaptic Stimulation | puffing | |

| control | 17/46 | 144/179 (26/33) | 36/39 | 19/55 | 149/178 (26/33) |

| gabazine and CGP55845 | 7/13 | 8/9 (4/5) | — | 8/15 | 6/9 (4/5) |

| atropine | — | 17/21 | — | — | 17/21 |

| DNQX and DL-APV | 1/1a | 8/9 (4/5) | — | 1/1a | 6/9 (4/5) |

DL-APV only.

Values represent the fractions of total cells and ferret cells (where applicable, in parentheses) for which a hyperpolarization or depolarization was observed using each stimulation technique and in the presence of each listed pharmacological agent. Data are shown for recordings made in control ACSF and in the presence of bath-applied antagonists: 10 μM gabazine and 1 μM CGP55845, 1 μM atropine, or 20 μM DNQX and 50 μM DL-APV; to block GABAA/B, muscarinic acetylcholine and AMPA and NMDA receptors, respectively.

Table 2.

The hyperpolarization and depolarization were blocked by inhibitors of internal Ca2+ release and mGluRs

| Drugs Applied | Hyperpolarization Blocked |

Depolarization Blocked |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Stimulation | puffing | Uncaging | Synaptic Stimulation | puffing | |

| BAPTA | — | 5 | — | — | 5 |

| CPA | — | 4 | — | 1 | 6 |

| ryanodine | — | 11 (7) | — | — | 9 (5) |

| 2-APB | 2 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| MPEP and LY367385 | 5 | — | — | 6 | — |

Values represent the numbers of total cells and ferret cells (where applicable, in parentheses) for which a hyperpolarization or depolarization was blocked by inclusion of the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA (50 mM) in the patch pipette solution or by bath application of the SERCA pump inhibitor CPA (50 μM), the ryanodine receptor agonist ryanodine (15 μM), the IP3R inhibitor 2-APB (100 μM), or the group I mGluR antagonists MPEP and LY367385 (10 and 100 μM, respectively).

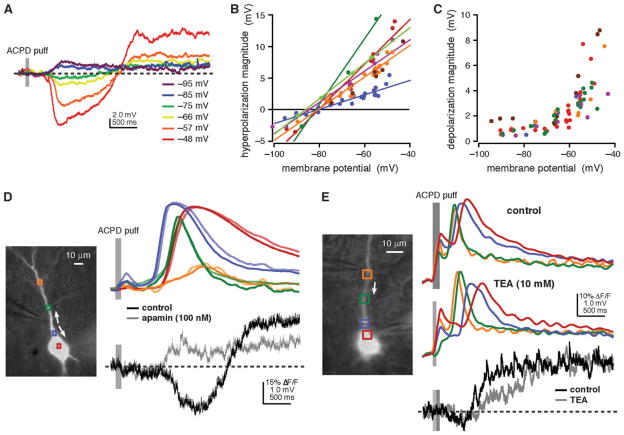

Internal Ca2+ Release–Mediated Hyperpolarization

To gain insight into the ionic mechanism underlying the hyperpolarization, we triggered release at different membrane potentials. The hyperpolarization increased in magnitude as the cell was depolarized (n = 7) and reversed when the cell was hyperpolarized (n = 6; Fig. 2A,B). The hyperpolarization reversed at −82.5 ± 1.0 mV (uncorrected for junction potential), which is near the Nernst potential for K+, suggesting that it was mediated by a Ca2+-activated K+ current. We therefore tested whether the hyperpolarization could be blocked by antagonists to small-conductance and large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (SK and BK, respectively). In the presence of the BK antagonist charybdotoxin (100 nM), the hyperpolarization was diminished, though not blocked (73.0 ± 2.5% of control; n = 4). By contrast, the SK antagonist apamin (100 nM) completely blocked the hyperpolarization in all cells tested (n = 9 rat cells, n = 4 ferret cells; Fig. 2D). These data indicate that the hyperpolarization is primarily mediated by SK channels that are activated by Ca2+ released from internal stores.

Figure 2.

The hyperpolarization was mediated by SK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channels. The depolarization had characteristics consistent with activation of a nonspecific cationic current. (A) ACPD puffs (60 ms) triggered Ca2+ waves (not shown) and a hyperpolarization and depolarization while this rat cell was held in current clamp at different membrane potentials. At depolarized potentials, both the hyperpolarization and the depolarization increased in magnitude. At hyperpolarized potentials, the hyperpolarization and depolarization both became smaller. Only the hyperpolarization reversed. (B) Ca2+ waves and a hyperpolarization were triggered by ACPD puffs onto rat neurons at different membrane potentials. Hyperpolarization magnitude increased with depolarization in all cells tested and reversed (−82.5 ± 1.0 mV) in all cells for which Ca2+ waves were triggered at potentials more negative than −80 mV. (C) Ca2+ waves and a depolarization were triggered by ACPD puffs onto rat neurons at different membrane potentials. Depolarization magnitude increased with depolarization and decreased with hyperpolarization in all cells tested but did not apparently reverse. (D) ACPD puffs (100 ms) onto this ferret neuron triggered Ca2+ waves with standard recording ACSF and following addition of the SK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channel antagonist, apamin (100 nM). In control recording ACSF, puffs of ACPD triggered a brief membrane hyperpolarization followed by a sustained membrane depolarization. Following application of apamin, the depolarization persisted, but the hyperpolarization was no longer detectable. (E) Ca2+ waves and a depolarization were triggered by puffs of ACPD (50–100 ms) onto this rat neuron in normal recording ACSF (100 ms puff) and following addition of the broad-spectrum K+ channel antagonist, TEA (10 mM; 50 ms puff). The depolarization was not inhibited by TEA exposure.

Internal Ca2+ Release–Mediated Depolarization

We also examined the depolarization at different membrane potentials. Depolarizing the neuron increased the amplitude of the depolarization (n = 6). Unlike the hyperpolarization, however, the depolarization did not reverse when the neuron was hyperpolarized (n = 6; Fig. 2A,C). To further characterize the depolarization, we examined underlying changes in membrane conductance. Whole-cell membrane conductance, which was assessed by measuring the voltage deflection in response to brief somatic current injections (200 ms, −150 to −250 pA), decreased during the depolarization (− 0.42 ± 0.08 pS or −6.0 ± 1.3%; n = 7; data not shown), suggesting that the depolarization results from the closing of ion channels (e.g., Benardo and Prince 1982; Crepel et al. 1994; Guerineau et al. 1995). An alternative explanation of these observations is that the depolarization results from the activation of a Na+-carrying conductance with a strong voltage dependence near rest (e.g., Hasuo et al. 1990; Crepel et al. 1994; Guerineau et al. 1995; Haj-Dahmane and Andrade 1996; Congar et al. 1997; Klink and Alonso 1997; Gee et al. 2003).

To distinguish between these possibilities, we tested whether the depolarization could be occluded by antagonism of K+ channels using either a cesium methanesulfonate–based intracellular solution or bath-applied TEA (10 mM). Neither intracellular cesium nor bath-applied TEA had a significant effect on the maximum depolarization magnitude (cesium, P > 0.5, WMW; n = 5; data not shown; TEA, P > 0.1, WMW; n = 3; Fig. 2E), despite significantly increasing action potential half-width (cesium, 269 ± 23% compared with 11 control cells from the same experimental time period, P < 0.005, t-test; n = 4; data not shown; TEA, 206 ± 13% compared with 11 control cells from the same experimental time period, P < 0.005, t-test; n = 3; data not shown). These data argue against inhibition of a K+ conductance as the source of the depolarization and support a mechanism involving a nonspecific cationic current (Haj-Dahmane and Andrade 1996, 1998). To test this possibility, we added flufenamate (250 μM) to the bath. Flufenamate has been reported to block a nonspecific cationic current (Haj-Dahmane and Andrade 1999) and a Ca2+-activated nonspecific cationic or ICAN current (Partridge and Valenzuela 2000; Schiller 2004). While flufenamate did indeed block the depolarization, it also blocked both internal Ca2+ release and the hyperpolarization (n = 3; data not shown). Thus, this experiment did not add any insight into the mechanism underlying the depolarization.

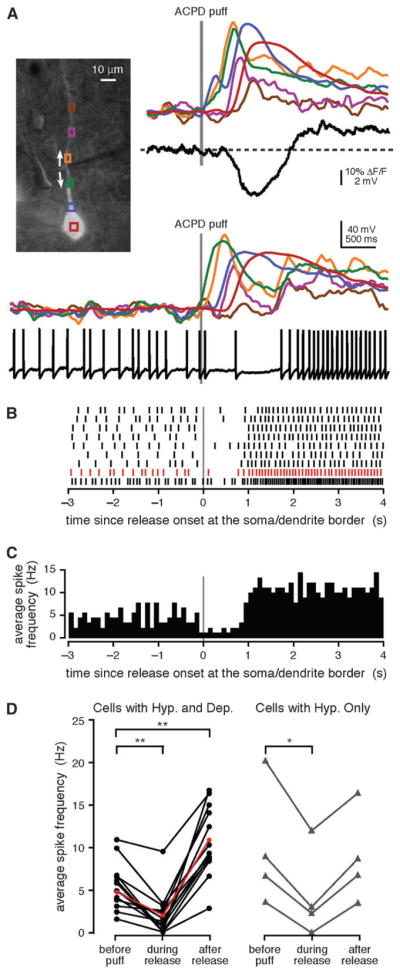

Internal Ca2+ Release–Dependent Hyperpolarization and Depolarization Modulate Excitability

To determine whether internal Ca2+ release might contribute to the modulation of patterns of activity in layer V mPFC pyramidal neurons, we tested whether depolarization-elicited spike trains were altered by the internal Ca2+ release–mediated hyperpolarization and depolarization (Morikawa et al. 2003; Stutzmann et al. 2003; Gulledge and Stuart 2005; Gulledge et al. 2006). To do this, we triggered action potentials by depolarizing the cell and then puffing ACPD onto the dendrite (Fig. 3). We found that, if in the absence of spiking, a puff resulted in a hyperpolarization followed by a depolarization, in the presence of spiking, a puff first resulted in a significant decrease in the rate of spiking (P < 0.001, paired t-test) followed by a significant increase (P < 0.001, paired t-test) in all cells tested (n = 14 rat cells). Likewise, puffs that produced only a hyperpolarization and no depolarization resulted in a significant decrease (P < 0.05, paired t-test), but not an increase (P > 0.10, paired t-test), in the rate of spiking in all cells tested (n = 4 ferret cells). The results of this experiment suggest that internal Ca2+ release in the mPFC may regulate the output of layer V pyramidal neurons.

Figure 3.

The hyperpolarization and depolarization modulated the firing of mPFC layer V pyramidal neurons. (A) Left, Alexa fluorescence image of a bis-fura-2–filled rat neuron with differential interference contrast overlay showing the position of the pressure application pipette adjacent to the primary apical dendrite. Right, a puff of ACPD (40 ms) evoked a Ca2+ wave, a hyperpolarization, and a depolarization. Bottom, when depolarized with positive somatic current injection (300 pA), the cell fired action potentials at an average rate of 6.2 Hz. A puff of ACPD (30 ms) given during the spike train triggered a Ca2+ wave that was accompanied by a decrease in the mean firing rate to 1.3 Hz. After the dendritic Ca2+ wave had subsided, the mean firing rate increased to 14.0 Hz. (B) Spike rasters depicting trains of action potentials evoked by 250–300 pA current injections and modulated following 30- to 40-ms puffs of ACPD for the cell shown in (A). Spike rasters are aligned with the onset of internal Ca2+ release at the soma–dendrite border. The spike raster for the event depicted in (A) is shown in red. (C) Average spike frequency histogram with 100-ms bins for the 9 events depicted in (B). (D) The average frequency of action potentials evoked by depolarizing current injection prior to APCD application, during Ca2+ release, and after the dendritic Ca2+ wave had subsided for 14 rat cells that exhibited both a hyperpolarization and a depolarization (left) and for 4 ferret cells that exhibited a hyperpolarization but no depolarization (right). Average spike frequency decreased during Ca2+ release in 18/18 cells that exhibited a hyperpolarization, and subsequently increased above the baseline in 14/14 cells that exhibited a depolarization, and in 0/4 cells that did not exhibit a depolarization. Data for the cell depicted in (A–C) are shown in red. Statistical significance was determined using paired Student’s t-tests; statistically significant changes in firing frequency relative to baseline are indicated with asterisks (**P < 0.001, *P <0.05).

The Hyperpolarization Depends on Internal Ca2+ Release in or Near the Soma

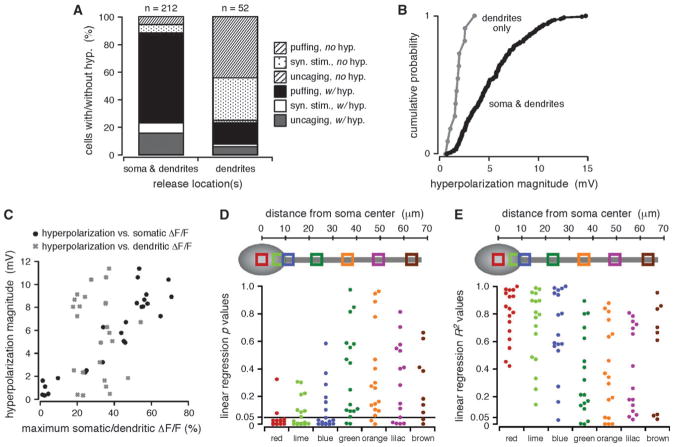

Based upon numerous reports showing a differential distribution of K+ channels on pyramidal neuron dendrites (Sah 1996; Poolos and Johnston 1999; Bekkers 2000; Johnston et al. 2000; Korngreen and Sakmann 2000; Yuan and Chen 2006) and also based upon immunohistochemical evidence for the somatic and proximal apical dendritic localization of apamin-sensitive SK channels in layer V neocortical pyramidal neurons (Sailer et al. 2002, 2004), we examined our data to determine whether production of the hyperpolarization or depolarization depended on the spatial distribution of internal Ca2+ release. Consistent with this possibility, and as shown by others for SK and BK channel localization (Poolos and Johnston 1999; Gulledge et al. 2006), our analysis revealed that rises in [Ca2+]i in or near the soma were associated with a membrane hyper-polarization. In particular, we discerned a hyperpolarization in 87% of all cells for which waves of internal Ca2+ release invaded the soma (n = 185/212 total cells; synaptic stimulation, n = 16/29; puffing, n = 136/148; uncaging, n = 33/35) but in only 23% of all cells where release was confined to the dendrites (n = 12/52 total cells; synaptic stimulation, n = 1/17; puffing, n = 8/31; uncaging, n = 3/4; Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the maximum amplitude of evoked hyperpolarizations was significantly greater for cells with somatic release than for cells with no somatic release (with somatic release, 0.7–14.8 mV, 5.5 ± 0.2 mV; no somatic release, 0.6–3.6 mV, 1.8 ± 0.2 mV; P < 0.001, KS; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

The hyperpolarization depended on somatic and perisomatic [Ca2+]i rises. (A) Cells are divided into 2 groups: those in which Ca2+ waves were observed in both the dendrites and the soma and those in which Ca2+ waves were confined to the dendrites. Plotted are the percentage of cells in each group for which a hyperpolarization was observed or not observed, broken down according to the type of stimulus used to evoke internal Ca2+ release. Cells in which Ca2+ waves invaded the soma were more likely to exhibit a hyperpolarization than cells in which Ca2+ waves were confined to the dendrites. (B) Plotted in ascending order are the magnitudes of the maximum hyperpolarization measured for the 2 groups of cells described in (A). The maximum magnitudes of hyperpolarizations evoked in cells for which Ca2+ waves propagated from the dendrites into the soma were significantly greater than those of hyperpolarizations evoked in cells for which Ca2+ waves were confined to the dendrites alone (P <0.001, KS). (C) Hyperpolarization magnitude versus the maximum amplitude of [Ca2+]i rises in the somata or in the primary apical dendrites for multiple trials in 5 representative cells. Maximum ΔF/F amplitudes were calculated for the red (soma) and green (dendritic) regions shown in (D, E). The hyperpolarization magnitude varied with somatic, but not dendritic, [Ca2+]i rises. (D) Top, approximate region of interest (ROI) locations over the soma and primary apical dendrite of a schematic cell. Bottom, P values from linear regression analyses comparing hyperpolarization magnitudes with the maximum amplitudes of [Ca2+]i rises in 5–7 ROIs spaced at approximately even intervals in 11 rat and 6 ferret cells. The hyperpolarization magnitude consistently correlated with the maximum ΔF/F amplitude for somatic and perisomatic (red, lime, and blue) but not dendritic (green, orange, purple, and brown) ROIs. (E) Approximate ROI locations and R2 values from the same linear regression analyses described in (D).

We next examined whether there was a linear correlation between the magnitude of the hyperpolarization and the amplitude of [Ca2+]i rises in the soma and along the primary apical dendrite. The hyperpolarization magnitude correlated significantly with the amplitude of internal Ca2+ release within the soma and at the soma–dendrite border (perisomatic regions) but not in parts of the primary apical dendrite over 10 μm from the soma–dendrite border (dendritic regions). In particular, there was a significant correlation between hyperpolarization magnitude and the maximum amplitude of internal Ca2+ release in 69% (35/51) of somatic and perisomatic regions but in only 17% (10/58) of dendritic regions (n = 11 rat cells, n = 6 ferret cells; Fig. 4C–E). Taken together, these data suggest that the hyperpolarization depends on somatic and perisomatic, but not dendritic, internal Ca2+ release.

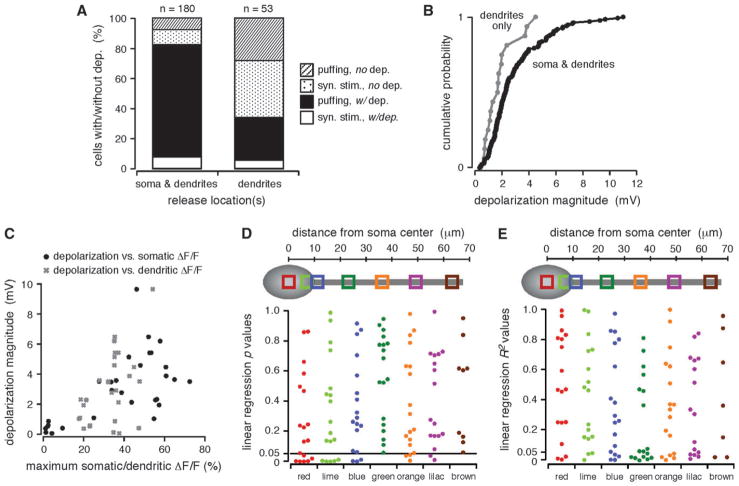

The Depolarization Depends on the Extent of Internal Ca2+ Release

The depolarization was also influenced by the extent of Ca2+ wave propagation; 82% of all cells with somatic release exhibited a membrane depolarization (n = 148/180 total cells; synaptic stimulation, n = 14/32; puffing, n = 134/148), whereas only 34% of all cells with no somatic release did so (n = 18/53 total cells; synaptic stimulation, n = 3/23; puffing, n = 15/30; Fig. 5A). Additionally, the maximum amplitude of evoked depolarizations was greater for cells with somatic release than it was for cells with no somatic release, although this difference was not statistically significant (with somatic release, 0.4–11.0 mV, 3.0 ± 0.2 mV; no somatic release, 0.4–4.5 mV, 1.8 ± 0.3 mV; P > 0.05, KS; Fig. 5B). Further, like the hyperpolarization, the depolarization generally increased with greater amplitude [Ca2+]i rises (Fig. 5C). Unlike the hyperpolarization, however, the magnitude of the depolarization was not well correlated with the amplitude of internal Ca2+ release in any particular region of the neuron. More specifically, in only 26% (14/54) of somatic and perisomatic regions and 14% (5/35) of dendritic regions did we observe a significant positive linear correlation between the magnitude of the depolarization and the amplitude of internal Ca2+ release (n = 10 rat cells, n = 7 ferret cells; Fig. 5D,E). Therefore, although the depolarization was more frequently detected and its magnitude generally greater when Ca2+ waves invaded the soma, it did not seem to depend on somatic and perisomatic rises in [Ca2+]i. Rather, these properties of the depolarization appear to reflect a general dependence on the total extent of Ca2+ wave propagation.

Figure 5.

The depolarization depended on the spatial extent of propagating Ca2+ waves. (A) Cells are divided into 2 groups: those in which Ca2+ waves were observed in both the dendrites and the soma and those in which Ca2+ waves were confined to the dendrites. Plotted are the percentage of cells in each group for which a depolarization was observed or not observed, broken down according to the type of stimulus used to evoke internal Ca2+ release. Cells in which Ca2+ waves invaded the soma were more likely to exhibit a depolarization than cells in which Ca2+ waves were confined to the dendrites. (B) Plotted in ascending order are the magnitudes of the maximum depolarization measured for the 2 groups of cells described in (A). The maximum magnitudes of depolarizations evoked in cells for which Ca2+waves propagated from the dendrites into the soma were generally, but not significantly, greater than those of depolarizations evoked in cells for which Ca2+waves were confined to the dendrites alone (P>0.05, KS). (C) Depolarization magnitude versus the maximum amplitude of [Ca2+]i rises in the somata or in the primary apical dendrites for multiple trials in 5 representative cells. Maximum ΔF/F amplitudes were calculated for the red (soma) and green (dendritic) regions shown in (D, E). The depolarization magnitude increased with the maximum amplitude of [Ca2+]i rises. (D) Top, approximate region of interest (ROI) locations over the soma and primary apical dendrite of a schematic cell. Bottom, P values from linear regression analyses comparing depolarization magnitudes with the maximum amplitudes of [Ca2+]i rises in 5–7 ROIs spaced at approximately even intervals in 10 rat and 7 ferret cells. The depolarization magnitude correlated more frequently with somatic and perisomatic than with dendritic [Ca2+]i rises. (E) Approximate ROI locations and R2 values from the same analyses described in (D).

Factors that Influence the Propagation of mGluR-Mediated Ca2+ Waves into the Soma

We have shown that internal Ca2+ release can hyperpolarize neurons and suppress action potential generation and that it can depolarize neurons and boost action potential generation. We have also shown that the hyperpolarization occurs only when Ca2+ is released at or near the soma and that its magnitude covaries with the amplitude of somatic internal Ca2+ release. Furthermore, we found that the depolarization depends on the extent of Ca2+ wave propagation. It follows that the potency of internal Ca2+ release for the modulation of excitability and patterns of activity in layer V mPFC pyramidal neurons is likely to depend on factors contributing to the extent of propagation of Ca2+ waves toward and into the somatic and perisomatic regions. We therefore investigated what contributes to Ca2+ wave propagation into the soma.

Extent of mGluR Activation Contributes to Ca2+ Wave Propagation

We first tested the prediction that increasing the strength of synaptic stimulation can cause a Ca2+ wave to propagate into the soma. For example, in the experiment shown in Figure 6A,B, we applied a brief stimulation train (30 pulses at 100 Hz) at 4 different intensities. At threshold stimulation intensity (60 μA), a rise in [Ca2+]i occurred in restricted portions of the apical and basal dendrites. With greater stimulation intensity (70 μA), Ca2+ waves propagated along both dendrites but did not reach the soma. As stimulation intensity was increased further (80 μA), Ca2+ waves from both dendrites propagated into the soma. The highest stimulation intensity tested (100 μA) elicited Ca2+ waves that propagated into and through the soma. We obtained similar results in 13/13 cells. One hypothesis for explaining this result is that stronger stimulation activates more afferent fibers and synapses and thus activates more mGluRs distributed over greater areas of the dendritic tree. Greater mGluR activation then leads to the mobilization of greater amounts of IP3 over a larger region, resulting in greater and more extensive internal Ca2+ release (Nakamura et al. 2002; Watanabe et al. 2006). To test this hypothesis, we applied ACPD puffs of variable duration to vary the extent of mGluR activation. Consistent with the results of synaptic stimulation experiments, we found that longer puffs also evoked larger and more reliable somatic [Ca2+]i rises (n = 53 rat cells, n = 5 ferret cells; Fig. 6C). For both synaptic and pharmacological stimulation, the amplitude of somatic internal Ca2+ release was more sensitive to changes in stimulus magnitude than the amplitude of dendritic internal Ca2+ release (Fig. 6A–C). Importantly, larger somatic internal Ca2+ release elicited by more robust synaptic and pharmacological mGluR stimulation evoked greater membrane hyperpolarizations (Fig. 6A,C) and depolarizations (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Increased stimulus intensity promoted the propagation of Ca2+ waves into the soma. (A) Trains of synaptic stimulation (30 pulses at 100 Hz) triggered Ca2+ waves in the primary apical dendrite and in a basal dendrite of the rat cell shown at right. The weakest stimulation intensity (60 μA) evoked threshold-level [Ca2+]i rises that were confined to the dendrites. When a stronger stimulation was used (80 μA), the Ca2+ waves were exhibited more extensive spread. The 80 μA stimulation intensity evoked 2 action potentials in the trial shown here and one action potential in a second trial. The strongest stimulation intensity (100 μA) triggered Ca2+ waves that invaded and passed through the soma. The 100 μA stimulation intensity also triggered 3 action potentials. For only the strongest stimulation intensity were Ca2+ waves accompanied by a distinct hyperpolarization. (B) Maximum ΔF/F is plotted versus position along the analysis line for Ca2+ waves evoked by stimuli of varying intensity in the cell shown in (A). As stimulation intensity increased, so did the extent to which Ca2+ waves propagated toward and into the soma. The 70 μA stimulus evoked one action potential in one trial and no action potentials in a second trial. (C) Puffs of ACPD (30–200 ms) onto the ferret cell shown at left triggered Ca2+ waves that originated in the primary apical dendrite and propagated bidirectionally. Longer puffs triggered more extensively propagating Ca2+ waves and larger somatic [Ca2+]i rises. Longer puffs also evoked greater membrane hyperpolarizations.

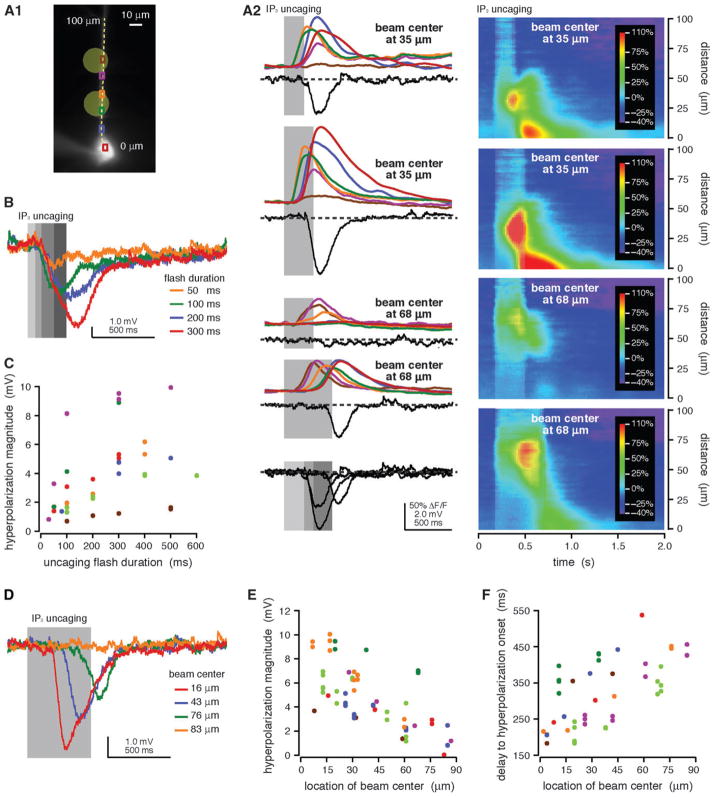

The Site and Duration of IP3 Photolysis Flashes Influence the Amplitude of Somatic Internal Ca2+ Release

A similar series of experiments was performed using focal photolysis of NPE-caged IP3, which provides better control over where IP3 is generated than do either synaptic stimulation or focal pressure application of ACPD. In these experiments, we wanted to determine how variations in the site and amount of mobilized IP3 might influence somatic internal Ca2+ release and the release-dependent hyperpolarization. We first examined the effects of increasing flash duration. Longer flashes evoked more substantial somatic internal Ca2+ release (n = 25/25) and greater magnitude membrane hyperpolarizations (n = 27/31) than did shorter flashes (Fig. 7A–C; Stutzmann et al. 2003). We next investigated how moving the uncaging beam away from the soma affects somatic internal Ca2+ release and the hyperpolarization. Both somatic internal Ca2+ release (n = 21/21) and the hyperpolarization (n = 21/21, R2 = 0.85 ± 0.03) decreased as the uncaging beam was moved away from the soma (Fig. 7A,D,E). Hyperpolarizations evoked by distal photolysis flashes also exhibited later onset than those triggered by proximal photolysis flashes (R2 = 0.75 ± 0.06; n = 18/21; Fig. 7A,D,F). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that the generation of a release-associated hyperpolarization depends on internal Ca2+ release in and near the soma. Furthermore, they suggest that IP3 mobilized close to the soma is more likely to evoke substantial somatic internal Ca2+ release and a release-dependent hyperpolarization than is distally produced IP3.

Figure 7.

Long uncaging flashes close to the soma evoked more substantial somatic [Ca2+]i rises and hyperpolarizations than did shorter or more distal uncaging flashes. (A1) Alexa fluorescence image of a rat neuron filled with fluo-4 (100 μM) and NPE-caged IP3 (97 μM) showing regions of interest (ROIs) and the location of the pseudo-linescan. (A2) UV flashes (200, 300, and 500 ms durations) from a beam directed at the primary apical dendrite (35 and 68 μm from the soma center) triggered Ca2+ waves and transient membrane hyperpolarizations. The amplitude of somatic [Ca2+]i rises and the magnitude of evoked hyperpolarizations were greater for longer flashes and smaller when the uncaging beam was moved away from the soma. The delay to hyperpolarization onset increased when the uncaging beam was moved away from the soma but was approximately constant for all flashes at a given location. Electrical traces are overlaid for comparison at the bottom of the figure. (B) Hyperpolarizations were evoked by UV flashes of variable duration (50, 100, 200, and 300 ms) from a beam directed at the primary apical dendrite 23 μm from the soma center in a different rat cell filled with NPE-caged IP3 (97 μM). Longer UV flashes evoked hyperpolarizations with greater magnitudes. The delay to hyperpolarization onset was approximately constant for all flash durations. Data for this cell are plotted in red in (C). (C) Hyperpolarization magnitude versus flash duration for 7 rat cells. Longer uncaging flashes evoked greater hyperpolarizations. (D) UV flashes of constant duration from a beam directed at variable locations (16, 43, 76, and 83 μm from the soma center) evoked hyperpolarizations in a different rat cell filled with NPE-caged IP3 (97 μM). Hyperpolarization magnitude decreased and delay to hyperpolarization onset increased as the uncaging beam was moved away from the soma. Data for this cell are plotted in red in (E, F). (E) Hyperpolarization magnitude versus uncaging location for 7 rat cells. Flashes proximal to the soma evoked greater hyperpolarizations than more distal flashes. (F) Delay to hyperpolarization onset versus uncaging location for the same 7 cells shown in (E). The delay to hyperpolarization onset was smaller for proximal flashes than for distal flashes.

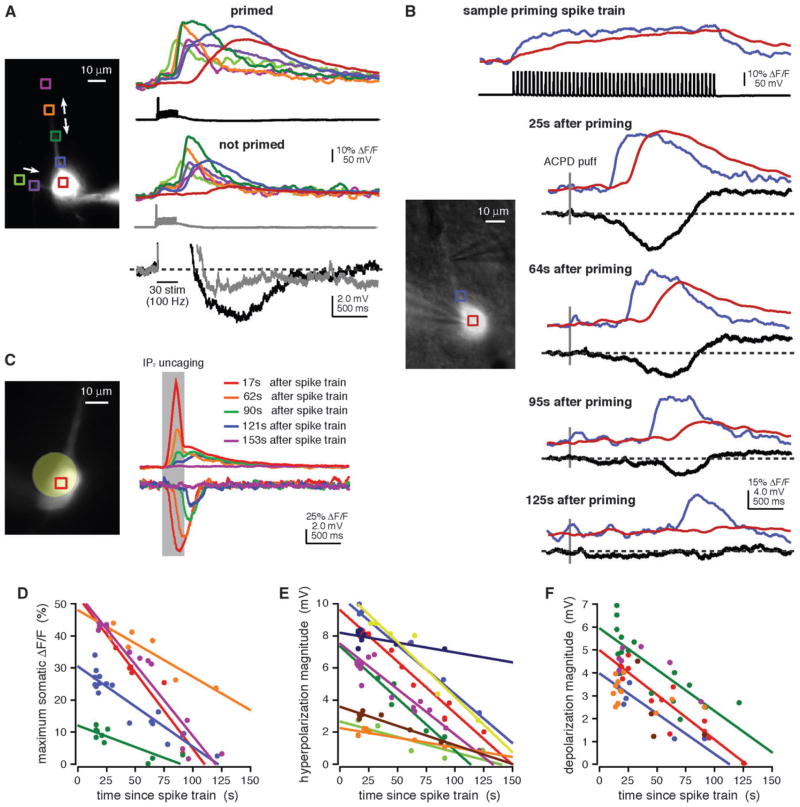

Previous Neuronal Activity Influences Internal Ca2+ Release and the Propagation of Ca2+ Waves

Numerous reports have demonstrated that depolarization-mediated Ca2+ influx through VGCCs (priming) enhances internal Ca2+ release (Friel and Tsien 1992; Jaffe and Brown 1994; Pozzo-Miller et al. 1996; Morikawa et al. 2000; Rae et al. 2000; Larkum et al. 2003; Stutzmann et al. 2003; Gulledge and Stuart 2005; Power and Sah 2005; Gulledge et al. 2006; Watanabe et al. 2006). We wanted to test whether priming could be accomplished with physiologically realistic trains of action potentials and as a consequence could lead to enhanced internal Ca2+ release–mediated changes in membrane potential. Regardless of the method used for triggering internal Ca2+ release, we found that priming with trains of action potentials (17 Hz, 3 s) that mimic PFC delay activity during working memory tasks (Fuster 1973; Funahashi et al. 1989; Narayanan and Laubach 2006) consistently facilitated Ca2+ wave propagation into the soma and enhanced the magnitude of release-associated hyperpolarizations (synaptic stimulation, n = 12/12; puffing, n = 58/63; uncaging, n = 15/17; Fig. 8A,B,C, respectively). The depolarization was consistently of greater magnitude following priming, as well (synaptic stimulation, n = 11/11; puffing, n = 61/63; Fig. 7B).

Figure 8.

Priming facilitated the propagation of Ca2+ waves into and through the soma and enhanced the hyperpolarization and depolarization. (A) Trains of synaptic stimulation (30 pulses at 100 Hz) evoked Ca2+ waves in the primary apical dendrite and a basal dendrite of the rat cell shown at left. When the stimulus was preceded by a spike train (17 Hz, 3 s), the Ca2+ waves propagated into and through the soma and were accompanied by a distinct hyperpolarization. Ca2+ waves triggered by the same stimulation but without prior spike train priming propagated shorter distances, had smaller amplitude in the soma, and were not accompanied by distinct hyperpolarizations. (B) Puffs of ACPD (30 ms) were applied onto this rat neuron at variable intervals following priming spike trains (17 Hz, 3 s). The maximum amplitude of somatic [Ca2+]i rises, as well as the magnitudes of the hyperpolarization and depolarization, decreased as the amount of time since priming increased. (C) UV flashes over the soma of a rat cell filled with NPE-caged IP3 (97 μM) triggered [Ca2+]i rises and hyperpolarizations. Both the maximum amplitude of somatic [Ca2+]i rises and the hyperpolarization magnitude decreased as the amount of time since priming increased. Optical data shown here were corrected for the tissue autofluorescence that results from exposure to the uncaging beam. (D) Maximum amplitude of ACPD puff-evoked somatic [Ca2+]i rises versus time since priming for 5 rat cells. The amplitude of [Ca2+]i rises in the soma correlated negatively (P <0.05) with the amount of time since priming for all 5 cells. (E) The magnitude of the hyperpolarization triggered by puffs of ACPD or by uncaging of NPE-caged IP3 versus time since priming for 9 rat cells. Hyperpolarization magnitude correlated negatively (P <0.05) with the amount of time since priming for all 9 cells. (F) The magnitude of the ACPD puff–evoked depolarization versus time since priming for 6 rat cells. Depolarization magnitude decreased as the amount of time since priming increased for all 6 cells. A negative correlation (P<0.05) was seen for only 3 of the 6 cells.

To further explore how the previous history of neuronal activity might influence Ca2+ waves, we tested whether the potency of priming spike trains depended on the time interval between delivery of the spike train and delivery of the release-triggering stimulus. More specifically, we examined the relationship between the time since priming and the amplitude of somatic internal Ca2+ release or the magnitudes of release-associated changes in membrane potential. We observed a statistically significant negative linear correlation between time since priming and somatic internal Ca2+ release in 5/5 cells (R2 = 0.84 ± 0.03; Fig. 8B,D) and between time since priming and hyperpolarization magnitude in 9/9 cells (R2 = 0.85 ± 0.03; Fig. 8B,C,E). The depolarization magnitude also decreased with time since delivery of the priming spike train, though in only 3/6 cells did we find a statistically significant negative linear correlation (R2 = 0.58 ± 0.10; Fig. 8B,F). These findings support the hypothesis that Ca2+ entry into pyramidal neurons enhances internal Ca2+ release by filling IP3-sensitive internal Ca2+ stores (reviewed in Verkhratsky and Petersen 1998; Friel 2004) and demonstrate a potential time dependence for the facilitation of internal Ca2+ release–dependent changes in membrane potential by priming. Furthermore, the approximately linear dependence of both evoked somatic [Ca2+]i rises and internal Ca2+ release-dependent hyperpolarizations on time since priming suggests a time-dependent depletion of luminal Ca2+ and is consistent with the existence of a constant leak from the IP3-sensitive Ca2+ pool (reviewed in Camello et al. 2002).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that mGluR-mediated waves of internal Ca2+ release can influence the excitability of layer V pyramidal neurons in the rodent and ferret mPFC via activation of Ca2+-dependent conductances. Specifically, our data show that Ca2+ waves can evoke a transient, SK-mediated hyperpolarization followed by a prolonged depolarization. The magnitude of these changes in membrane potential depends on the amplitude and spatial extent of propagating Ca2+ waves, such that large Ca2+ waves that invade the soma produce greater hyperpolarizations and depolarizations than do waves that have small amplitude or are confined to the dendrites. Our findings also point to a number of factors that are likely to influence whether an mGluR-mediated Ca2+ wave invades the soma. These include the intensity of synaptic stimulation, the site and amount of subsequently mobilized IP3, and the history of cell firing. Our results underline the potential importance of mGluR-mediated Ca2+ waves for the transient inhibition or prolonged excitation of neocortical pyramidal neurons and set the stage for understanding the conditions under which internal Ca2+ release contributes to the regulation of activity patterns and working memory in PFC.

Ca2+ Waves Influence Neuronal Excitability

We found that mGluR-mediated and IP3R-dependent Ca2+ waves triggered a transient membrane hyperpolarization in layer V mPFC pyramidal neurons. This finding is consistent with a number of reports describing a hyperpolarization in response to Gq protein–coupled receptor activation, IP3 mobilization, and internal Ca2+ release (Jaffe and Brown 1994; Fiorillo and Williams 1998; Morikawa et al. 2000, 2003; Stutzmann et al. 2003; Yamada et al. 2004; Gulledge and Stuart 2005; Gulledge et al. 2006). The hyperpolarization we observed in mPFC was dependent upon rises in intracellular [Ca2+]i, reversed near the Nernst potential for K+, and was blocked by the K+ channel antagonist apamin, indicating that it was mediated by SK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ channels.

In addition to the hyperpolarization, mGluR-mediated Ca2+ waves evoked a prolonged membrane depolarization in layer V mPFC pyramidal neurons. This depolarization was similar to mGluR- or mAChR-mediated inward currents or depolarizations that have been observed in multiple cell types, including somatosensory pyramidal neurons, CA1 and CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neurons, and midbrain dopamine neurons (e.g., Benardo and Prince 1982; Crepel et al. 1994; Haj-Dahmane and Andrade 1996; Fiorillo and Williams 1998; Gee et al. 2003; Rae and Irving 2004; Gulledge and Stuart 2005). The mechanisms reported to underlie these depolarizations are diverse and include the inhibition of K+ channels and the activation of Ca2+-dependent nonspecific cationic channels (reviewed in Anwyl 1999; Cobb and Davies 2005). The depolarization we observed depended on mGluR activation and rises in [Ca2+]i, increased in magnitude with depolarization and decreased with hyperpolarization, and was not occluded by K+ channel antagonists. These characteristics suggest that the depolarization described here is mediated by the Gq protein– and Ca2+-dependent activation of a nonspecific cationic current (e.g., Haj-Dahmane and Andrade 1996, 1998).

The hyperpolarization and depolarization depended on the extent of propagation of the Ca2+ waves that underlie their generation. In order to produce the SK-mediated hyperpolarization, for instance, it was necessary for Ca2+ waves to propagate close to or into the soma. Moreover, the magnitude of the hyperpolarization was both greater in cells for which Ca2+ waves invaded the soma and was consistently correlated with the amplitude of somatic and perisomatic, but not dendritic, [Ca2+]i rises. These findings are consistent with immunohistochemical data suggesting that SK channels are localized to the soma and proximal apical dendrites of layer V neocortical pyramidal neurons (Sailer et al. 2002, 2004) and with functional data reporting that SK-mediated hyperpolarizations are generated within or close to the soma (Sah 1996; Fiorillo and Williams 1998; Poolos and Johnston 1999; Johnston et al. 2000; Gulledge et al. 2006; Yuan and Chen 2006). The occurrence of the depolarization also depended on the extent of Ca2+ wave propagation. In particular, cells for which Ca2+ waves propagated into the soma were more likely to exhibit a depolarization and generally had larger depolarizations than cells for which Ca2+ waves were limited to the primary apical dendrite. The magnitude of the depolarization also generally increased with the increasing somatic internal Ca2+ release. It did not, however, correlate consistently with the amplitude of [Ca2+]i rises within or near the soma. These observations indicate that, unlike the hyperpolarization, the depolarization does not likely depend exclusively on somatic [Ca2+]i rises. Rather, its variability with somatic internal Ca2+ release suggests a dependence on the total spatial extent of propagating Ca2+ waves, such that more robust Ca2+ waves produce greater depolarizations because they propagate farther and encounter greater total amounts of somatodendritic membrane.

Factors that Influence the Propagation of Ca2+ Waves in mPFC

Our observation that the hyperpolarization and depolarization triggered by mGluR-mediated internal Ca2+ release depended on the propagation of Ca2+ waves toward and into the soma raises the possibility that factors influencing Ca2+ wave propagation may contribute to the regulation of excitability and patterns of activity in layer V PFC pyramidal neurons. To test this possibility, we examined factors that influence Ca2+ wave propagation in these cells. Although it is known that IP3R-mediated internal Ca2+ release depends on coincident activation of IP3Rs by both IP3 and Ca2+ (Bezprozvanny and Ehrlich 1994; Parker et al. 1996; Adkins and Taylor 1999), the basic mechanisms of Ca2+ waves in neurons have not been identified. Modeling studies and investigations of Ca2+ waves in non-neuronal cells report that Ca2+ waves can propagate by successive diffusion of Ca2+ between release sites where IP3 is bound (Parker and Ivorra 1990; Bootman et al. 1997; Callamaras et al. 1998). These studies suggest that important limitations on the extent of Ca2+ wave propagation might include the concentration and distribution of IP3 in the cytosol, the driving force on Ca2+ ions released from the ER into the cytosol, the physical distance between Ca2+ release sites, and the biophysical state of IP3Rs. These limitations translate into a number of different experimental factors that are likely to influence the propagation of mGluR-mediated Ca2+ waves, including the number of active glutamatergic afferents, the location and amount of mobilized IP3, and the size of the readily releasable ER Ca2+ pool.

We employed both synaptic stimulation and focal pharmacological activation of mGluRs to examine how increasing the number of active glutamatergic afferents might influence Ca2+ wave propagation. Increasing the intensity of synaptic and pharmacological stimulation, manipulations that presumably result in the activation of greater numbers of synapses and mGluRs over a larger area resulted in more extensive spread of Ca2+ waves and promoted their propagation into the soma. Because it was not possible with either of these methods to manipulate the precise distribution of activated mGluRs, we used focal photolysis of NPE-caged IP3 to test the influence of the location and amount of IP3 mobilization on the propagation of Ca2+ waves toward and into the soma. As predicted, Ca2+ waves triggered by large boluses of IP3 mobilized close to the soma were more likely to invade the soma than were Ca2+ waves triggered by IP3 mobilization at more distal locations. In combination, these 2 sets of experiments suggest that the simultaneous activation of many glutamatergic afferents with synapses on the proximal apical and basal dendrites is likely to generate mGluR-mediated Ca2+ waves that invade the soma and are capable of triggering the transient inhibition and prolonged excitation of layer V PFC pyramidal neurons.

The depolarization of neurons during spike trains allows Ca2+ to enter the cytosol through VGCCs on the plasma membrane, from where it is subsequently sequestered into the lumen of ER, replenishing the ER Ca2+ pool (reviewed in Pozzo-Miller et al. 2000; Camello et al. 2002). This priming of the ER suggests that information about a neuron’s recent firing history is stored in the concentration of calcium within the lumen of the ER (reviewed in Berridge 1998; Verkhratsky and Petersen 1998). Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that priming neurons with spike trains that mimic the elevated activity of some PFC neurons during working memory tasks promoted the propagation of Ca2+ waves into the soma (but see Watanabe et al. 2006). We further found that facilitation by priming of Ca2+ wave propagation decayed with time. These results suggest that the incidence of internal Ca2+ release and the propagation of Ca2+ waves into the soma of layer V PFC pyramidal neurons may be linked, both causally and temporally, to their activity.

Functional Significance

The role that the PFC plays in complex cognitive functions such as decision making, impulse control, reward valuation, and emotional regulation depends upon its ability to support working memory processes (Malmo 1942; Bartus and Levere 1977; Fuster 1985; Goldman-Rakic 1995). Working memory—the ability to hold information in mind or to retrieve and manipulate information to guide behavior—is determined by the spatial and temporal firing patterns of interconnected populations of neurons. The ability of Ca2+ waves to change the firing patterns of PFC neurons suggests that Ca2+ waves may contribute to working memory. The specific consequences of changing the firing rates of layer V pyramidal neurons involved in working memory depend on the role that these neurons play during working memory tasks. This role is not precisely known. Some pyramidal neurons begin to fire more rapidly when a stimulus is presented and continue to do so until this information has been used to guide behavior; the activity of these “delay cells” is thought to be essential for information storage. The firing rates of other groups of pyramidal neurons remain unchanged while information is held in mind only to increase when a behavior is executed. Still other pyramidal neurons actually decrease their firing rates while information is held in memory (e.g., Kubota and Niki 1971; Fuster 1973; Funahashi et al. 1989; Batuev et al. 1990; Narayanan and Laubach 2006). Thus, interpreting the role of a Ca2+ wave and its consequent effects on firing rates during specific periods of working memory tasks is not straightforward.

The time courses of the hyperpolarization and depolarization might provide some insight into the potential role of Ca2+ waves in working memory. For example, the transient nature of the hyperpolarization suggests that it might contribute to a relatively rapid resetting of activity or “erasure” of a memory, whereas the sustained depolarization might contribute to stabilizing persistent activity against so-called distractors (reviewed in Durstewitz et al. 2000; Wang 2001). Other aspects of our results are more difficult to interpret. For example, our observation that the hyperpolarization preceded the depolarization, resulting first in a decrease and then an increase in firing rate, is inconsistent with the expectation that firing rates would first increase and then decrease when information is stored and then lost. Furthermore, the duration of the depolarization has the capacity to exceed the duration of a working memory. To address these issues, additional experiments need to be performed to identify the rules determining whether Ca2+ waves occur and the extent to which these waves propagate during different phases of working memory. A Ca2+ wave may occur when the stimulus is present, when it is absent but remembered, or when the memory of the stimulus is used to guide behavior. A Ca2+ wave at each of these different times would have different effects on the activity of a pyramidal neuron involved in the working memory system.

Speculation on the role of Ca2+ waves in working memory is further complicated by at least 2 factors. First, while we have focused on the effects of Ca2+ waves on action potential generation, the converse is also true: action potentials affect Ca2+ waves by increasing the concentration of both intracellular and luminal Ca2+. The complete set of reciprocal interactions between Ca2+ waves and action potentials has not been characterized (Nakamura et al. 1999, 2000; Kapur et al. 2001). Second, reverberatory activity among recurrently connected PFC neurons may form the basis for the persistent activity of pyramidal neurons during working memory tasks (reviewed in Durstewitz et al. 2000; Wang 2001). Such reverberatory activity might be susceptible to perturbations in a single cell or a small group of cells in the circuit. If this is true, changes to the firing rate produced by a Ca2+ wave in one pyramidal neuron may ripple through the network, changing network behavior in an unknown manner. All in all, it is unrealistic to expect a simple relationship between a complex cellular phenomenon such as Ca2+ waves and a complicated system phenomenon such as working memory and much work remains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Hertle and Amy Arnsten for many thoughtful discussions and Tibor Koos for advice on recording from neocortical neurons. Funded by the Whitehall Foundation, the Kavli Foundation, the Dart Foundation, NIMH (RO1-MH067830 and P50-MH068789; MFY), and an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (AMH).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

For permissions, please: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org

References

- Adkins CE, Taylor CW. Lateral inhibition of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors by cytosolic Ca(2+) Curr Biol. 1999;9:1115–1118. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwyl R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: electrophysiological properties and role in plasticity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999;29:83–120. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartus RT, Levere TE. Frontal decortication in rhesus monkeys: a test of the interference hypothesis. Brain Res. 1977;119:233–248. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batuev AS, Kursina NP, Shutov AP. Unit activity of the medial wall of the frontal cortex during delayed performance in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1990;41:95–102. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(90)90145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers JM. Distribution of slow AHP channels on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1756–1759. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benardo LS, Prince DA. Cholinergic excitation of mammalian hippocampal pyramidal cells. Brain Res. 1982;249:315–331. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendse HW, Groenewegen HJ. Restricted cortical termination fields of the midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei in the rat. Neuroscience. 1991;42:73–102. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90151-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]