Abstract

In recent years, combinations of pharmacological treatments have become common for the treatment of bipolar disorder type I (BP I); however, this practice is usually not evidence-based and rarely considers monotherapy drug regimen (MDR) as an option in the treatment of acute phases of BP I. Therefore, we evaluated comparative data of commonly prescribed MDRs for both manic and depressive phases of BP I. Medline, PsycINFO, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, the ClinicalStudyResults.org and other data sources were searched from 1949 to March 2009 for placebo and active controlled randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Risk ratios (RRs) for response, remission, and discontinuation rates due to adverse events (AEs), lack of efficacy, or discontinuation due to any cause, and the number needed to treat or harm (NNT or NNH) were calculated for each medication individually and for all evaluable trials combined. The authors included 31 RCTs in the analyses comparing a MDR with placebo or with active treatment for acute mania, and 9 RCTs comparing a MDR with placebo or with active treatment for bipolar depression. According to the collected evidence, most of the MDRs when compared to placebo showed significant response and remission rates in acute mania. In the case of bipolar depression only quetiapine and, to a lesser extent, olanzapine showed efficacy as MDR. Overall, MDRs were well tolerated with low discontinuation rates due to any cause or AE, although AE profiles differed among treatments. We concluded that most MDRs were efficacious and safe in the treatment of manic episodes, but very few MDRs have demonstrated being efficacious for bipolar depressive episodes.

Keywords: Anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, bipolar, bipolar depression, lithium, mania, monotherapy

Background

A recent systematic review of 913 papers, suggested that lithium, some anticonvulsants and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are valuable in the treatment of acute mania (Fountoulakis & Vieta, 2008). Up until recently, first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) were often the preferred choice for treatment of acute mania, especially in European countries (Tohen et al. 2001; Vestergaard, 1992); however, some reports suggest that they may induce or worsen depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder (Esparon et al. 1986; Zarate & Tohen, 2004). Furthermore, patients with bipolar disorder compared to patients with schizophrenia appear to be more susceptible to extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) (Cavazzoni et al. 2006; Mukherjee et al. 1986). For bipolar depressed patients, there is uncertainty about the role of antidepressants as they have been associated with manic relapse (Lewis & Winokur, 1982), lack of efficacy (Post et al. 2006; Sachs et al. 2007), and cycle acceleration (Wehr & Goodwin, 1979).

Although combination drug regimens (CDRs) have become ubiquitous in the treatment of non-refractory BP I around the world (Baldessarini et al. 2007; Blanco et al. 2002; Goldberg et al. 2009; Kupfer et al. 2002; Levine et al. 2000; Wolfsperger et al. 2007), the goal of this review was to examine the efficacy and safety of monotherapy drug regimens (MDRs). Despite treatment guidelines recommending the use of monotherapy as a first-line strategy (Grunze et al. 2009), polypharmacy often occurs without evidence-based support or sometimes without clear or adequate optimization. For instance, Perlis et al. (2006) found that differences in acute efficacy in the treatment of mania with SGAs are likely to be small, if any, between monotherapy and add-on therapy. However, the literature suggests that there are patients who do not respond to acute treatment with monotherapy, especially in bipolar depression (Blanco et al. 2002; Goldberg et al. 2009; Kupfer et al. 2002). A recent meta-analysis, however, compared co-therapy (antipsychotic plus mood stabilizer) with monotherapy (mood stabilizer alone) in the treatment of bipolar mania, and found higher response rates with co-therapy although with decreased tolerability (Smith et al. 2007). Cipriani et al. (2007) have suggested that the small sample sizes and the heterogeneity of the study designs lead to biased results favouring co-therapy.

Material and methods

Search strategy and study selection

We conducted a comprehensive literature search of all the articles published up to March 2009 incorporating results of searches of Medline (from 1950), PsycINFO (from 1949), EMBASE (from 1988), the Cochrane Library (2009 January Issue), LILACS (from 1982), the ClinicalStudyResults.org, and two Internet search engines: PsiTri (www.psitri.stakes..) and Google Scholar (scholar.google.com). A limited update literature search using Medline was performed from 15 March 2009 to 13 August 2009.

To capture articles relevant to the scope of our review, we cross-referenced terms like ‘bipolar disorder’, ‘manic depressive’, ‘mania’, ‘mixed’, or ‘bipolar depression’, with trial characteristics search phrases and generic names of medications (approved or non-approved by regulatory agencies for their use in bipolar disorder). The full electronic search strategy is available upon request.

We planned a priori the inclusion of studies meeting the following criteria: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing response and/or remission rates of a MDR with placebo or active treatment in patients with BP I (manic/mixed or depressive episodes). We chose discrete measures (response or remission rates) because they are clinically meaningful outcome measures (Lam & Kennedy, 2005). Exclusion criteria included: use of rating scales not validated in patients with bipolar mania, no clear definition of response or remission criteria, or inclusion of patients who had previously failed to respond to lithium or other mood stabilizers. Sample size was also an eligibility criteria to avoid weighting small studies inappropriately as suggested by Petitti (2000) when using random-effects models. The minimum median sample was 16.5 subjects in each group as suggested by a published empirical model (Richy et al. 2004). Additional information required included trial duration, and medication dosage ranges. In addition, trials had to be peer-reviewed and published.

All RCTs were identified and reviewed by two of the authors (J.T. and G.V.). Any disagreements were discussed in order to reach consensus. Names of authors, institutions, or journals were not kept blind.

Evidence-based data for MDRs

We analysed the evidence supporting a therapeutic advantage for each MDR individually and for all evaluable trials combined vs. placebo or other active medication if they were classified as responders (a reduction of at least 50% in the initial score with any appropriate symptom rating scale) or remitters (a predetermined minimum absolute score as recommended in the literature (Tohen et al. 2009); i.e. Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) ≤ 12 or Mania Rating Scale (MRS) ≤ 8 for patients with a manic/mixed episode, or Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) ≤ 12 or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) ≤ 8 for patients with a depressive episode). Rates of discontinuation due to any cause, lack of efficacy, or adverse events (AEs) were also extracted.

Data synthesis

Studies were first qualitatively summarized. When more than one RCT was available for each MDR-comparator contrast, a meta-analytical calculation was used for each MDR. Efficacy and safety dichotomous data were statistically combined using a random-effects model. The relative risk (RR), which is defined as the ratio of the risk of an unfavourable outcome (non-response or non-remission) among treatment-allocated participants to the corresponding risk of an unfavourable outcome among those in the control group, was estimated along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the Review Manager 5.0.21 version software (The Cochrane Collaboration, UK). We also calculated RRs along with their 95% CIs for discontinuation due to any cause or discontinuation due to AEs for each MDR. Effect sizes such as number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH) were also calculated. For this purpose we calculated risk differences (RDs), so NNT and NNH were estimated from the RD by the formula NNT or NNH=1/RD, with the 95% CI of NNT or NNH being the inverse of the upper and lower limits of the 95% CI of the RD. Only NNTs or NNHs <10 are considered clinically meaningful (Cook & Sackett, 1995; Kraemer & Kupfer, 2006).

Finally, we assessed the quality of the report on every RCT included in this review using a scale designed by Jadad et al. (1996). We performed χ2 and I2 statistics and the visual inspection of the forest plots derived from the χ2 values to test the proportion of total variation in study estimates that is due to heterogeneity. This analysis contrasts the RR of the individual trials with the pooled RR or the subgroups of trials. An I2 of at least 50% was taken as indicator of heterogeneity of outcome and considered inconclusive (Egger et al. 1997, 2001; Higgins & Thompson, 2002; Higgins et al. 2003).

Results

Included studies

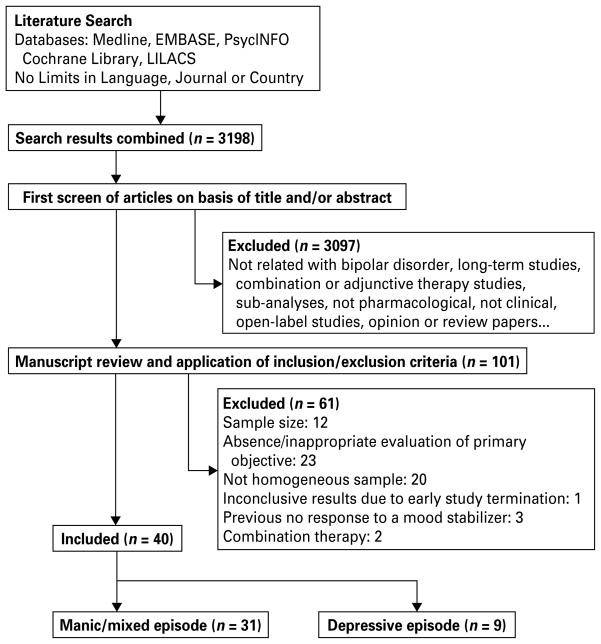

We identified 101 non-duplicated RCTs, of which 40 fulfilled search criteria (Fig. 1). Some of the RCTs used a three-arm design thus could be used to make two comparisons each. In some cases, two or more articles/references provide data for the same RCT. The duration of most studies was 3 wk and most of them used the YMRS for the assessment of severity of manic symptoms. For bipolar depression, most studies were at least 7 wk in duration and utilized either the HAMD or the MADRS for the assessment of severity of depressive symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Flow of information diagram through the different phases of the systematic review.

MDRs for acute mixed/mania episodes

Since the first evidence of lithium’s efficacy in mania reported by Cade (1949) a considerable number of RCTs evaluating the efficacy of lithium salts, anticonvulsants, FGAs and SGAs used as MDRs in patients with acute mania have been published. Many studies that were reviewed did not meet our inclusion criteria due to their small sample size. Other studies were excluded because they had used rating scales neither specific nor validated for mania, had not included a clear definition of response or remission criteria, or had included patients that had previously not responded to lithium or other mood stabilizers [Ballenger & Post (1978, 1980), Berk et al. (1999), Bradwejn et al. (1990), Brown et al. (1989), Clark et al. (1997), Cookson et al. (1981), DelBello et al. (2005), Esparon et al. (1986), Findling et al. (2007), Freeman et al. (1992), Garfinkel et al. (1980), Garza-Treviño et al. (1992), Goncalves & Stoll (1985), Goodwin et al. (1969), Harrison & Keating (2005), Ichim et al. (2000), Janicak et al. (1998), Johnson et al. (1968), Kowatch et al. (2000), Kudo et al. (1987), Lerer et al. (1987), Lyseng-Williamson & Perry (2004), McElroy et al. (1991), Mishory et al. (2000), Moreno et al. (2007), Okuma et al. (1979, 1990), Ortega et al. (1993), Platman (1970), Pope et al. (1991), Post et al. (1987), Prien et al. (1972), Segal et al. (1998), Shopsin et al. (1975), Small et al. (1991), Spring et al. (1970), Storosum et al. (2007), Takahashi et al. (1975), Vasudev et al. (2000), Walton et al. (1996), and Zajecka et al. (2002)]. Four RCTs with topiramate (n=433) vs. placebo (n=437) were presented in a combined analysis by Kushner et al. (2006) showing no significant efficacy difference between treatment groups. Two of those RCTs included lithium (n=227) as an active comparator. Unfortunately, separate data for our primary efficacy measures were not available.

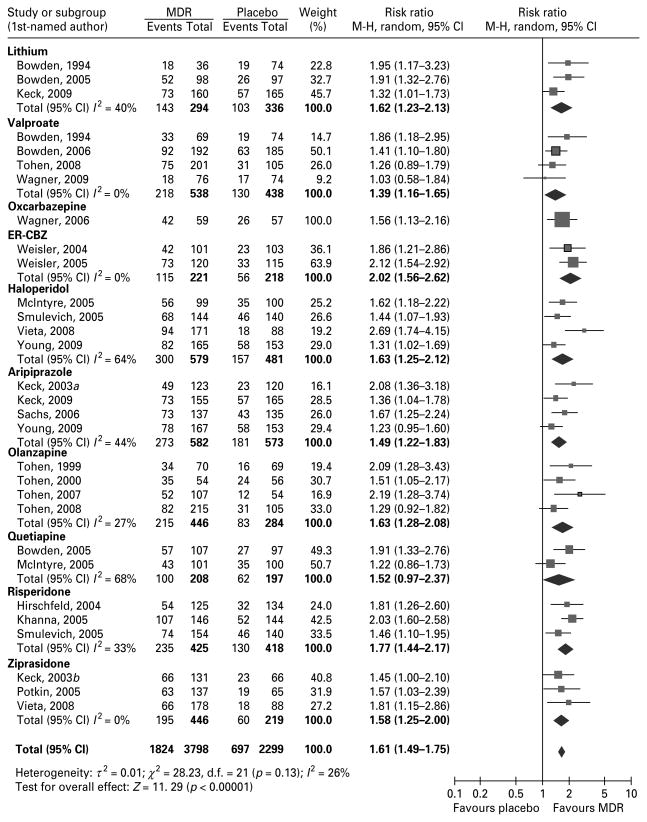

In summary, 31 RCTs in acute mania fulfilled our study criteria (Table 1). Patients treated with MDR (n=3798) had a 1.61 (95% CI 1.49–1.75, I2=26%) higher chance of response, a 0.86 (95% CI 0.77–0.95, I2=40%) lower risk of discontinuation due to any cause, and a 0.55 (95% CI 0.47–0.63, I2=30%) lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, but a 1.57 (95% CI 1.22–2.03, I2=18%) greater risk of discontinuation due to AEs than patients treated with placebo (n=2299). Additional comparisons showed that patients treated with mood stabilizers (n=1112) had a 1.57 (95% CI 1.36–1.81, I2=33%) higher chance of response, a 1.42 (95% CI 1.15–1.75) higher chance of remission (I2=40%), and a 0.55 (95% CI 0.41–0.74, I2=44%) lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, but a 2.07 (95% CI 1.46–2.93, I2=0%) greater risk of discontinuation due to AEs than those patients treated with placebo (n=975). Furthermore, patients treated with SGAs (n=2107) had a 1.59 (95% CI 1.44–1.75, I2=22%) higher chance of response, a 0.55 (95% CI 0.46–0.65, I2=16%) lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, and a 0.87 (95% CI 0.79–0.95, I2=0%) lower risk of discontinuation due to any cause, but a 1.36 (95% CI 1.03–1.79, I2=0%) higher risk of discontinuation due to AEs than patients treated with placebo (n=1691).

Table 1.

Features and results of randomized trials of monotherapy drug regimen in patients with a bipolar disorder type I

| Trial (in order of appearance in text) | Patient inclusion criteria | Duration (wk) | Number randomized | Start→exit dosage (mg/d) or plasma levels (mean) | RCT qualitya | Sponsored by industry? | Responders (%) | Remitters (%) | Significant AE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowden (1994) | H, 18–65 yr, AM (SADS), MRS≥14 | 3 | Li=36, VAL=69, PLA=74 | Li (1950 or 1.2 mmol/l), VAL (2000 or 93.2 μg/ml) | 4 | Yes | Li=49, VAL=48, PLA=25 | n.a. | Li – vomiting, twitching, fever VAL – vomiting |

| Bowden (2005) | H, ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | Li=98, QUE=107, PLA=97 | Li (900→ 0.73 mEq/l), QUE (400→586) | 4 | Yes | Li=53.1, QUE=53.3, PLA=27.4 | Li=49, QUE=46.7, PLA=22.1 | Li – tremor, headache, ↑ TSH QUE – dry mouth, somnolence, ↑ weight, dizziness |

| Keck (2009) | H, >18 yr, AM (DSM-IV-TR), YMRS≥20 | 3 | Li=160, ARI=155, PLA=165 | Li (900–1500) (0.76 mEq/l), ARI (15→23.2) | 4 | Yes | Li=45.8, ARI=46.8, PLA=34.4 | Li=40, ARI=40.3, PLA=28.2 | Li – constipation, nausea, tremor ARI – akathisia, constipation, nausea, sedation |

| Niufan (2008) | H, ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV-TR), YMRS≥20 | 4 | Li=71, OLZ=69 | Li (1110), OLZ (17.8) | 4 | Yes | Li=73, OLZ=87 | Li=70, OLZ=82 | Li – nausea OLZ – ↑ weight, constipation, somnolence |

| Li (2008) | H, 18–65 yr, AM (CCMD-3), YMRS≥20 | 4 | Li=77, QUE=78 | Li (0.8 mmol/l), QUE (648.2) | 3 | Yes | Li=46, QUE=60 | Li=25, QUE=40 | Li – nausea, constipation, vomiting, dizziness, diarrhoea QUE – constipation, dizziness, diarrhoea, ↑ ALT, ↑ AST, palpitations, dry mouth |

| Singh (2008) | H, ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 4 | Li=25, VER=25 | Li (900), VER (160→320) | 3 | No | Li=28, VER=32 | Li=48, VER=52 | Li – constipation VER – tremor |

| Weisler (2004) | H, ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | ER-CBZ=101, PLA=103 | ER-CBZ (400→756.44 or 8.9 mg/ml) | 4 | Yes | ER-CBZ=41.5, PLA=22.4 | n.a. | ER-CBZ – dizziness, nausea, somnolence, vomiting, dyspepsia, dry mouth, pruritus, speech disorder |

| Weisler (2005) | H, ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | ER-CBZ=120, PLA=115 | ER-CBZ (400→642.6) | 4 | Yes | ER-CBZ=61, PLA=29 | n.a. | ER-CBZ – dizziness, somnolence, nausea, ataxia, vomiting, blurred vision |

| Wagner (2006) | O, 7–18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 7 | OXC=59, PLA=57 | OXC (300→1515) | 4 | Yes | OXC=42, PLA=26 | n.a. | OXC – dizziness, nausea, somnolence, diplopia, fatigue, rash |

| Bowden (2006) | H, 18–65 yr, AM (DSM-IV), MRS≥18 | 3 | VAL=192, PLA=185 | VAL (3057 or 95.9 μg/ml) | 4 | Yes | VAL=48, PLA=34 | VAL=48, PLA=35 | VAL – somnolence, dizziness, GI complaints |

| Tohen (2008) | O+H, 18–65 yr, AM (DSM-IV-TR), YMRS=20–30 | 3 | VAL=201, OLZ=215, PLA=105 | VAL (848.4), OLZ (11.4) | 4 | Yes | VAL=40.3, OLZ=40.8, PLA=31.3 | VAL=40.3, OLZ=42.8, PLA=35.4 | VAL – nausea, insomnia, ↓ platelets, ↓ leukocytes, ↑ appetite OLZ – ↑ weight, ↑ TGl, ↑ Glu, ↑ Chol, ↑ prolactin, somnolence |

| DelBello (2006) | H, 12–18 yr, AM (DSM-IV-TR), YMRS≥20 | 4 | VAL=25, QUE=25 | VAL (20 mg/kg.d→101 μg/ml), QUE (100→412), | 3 | No | n.a. | VAL=60, QUE=28 | VAL – ↓platelets QUE – ↑ ALT |

| McElroy (1996) | H, 18–65 yr, AM (DSM-III-R), psychotic | 1 | VAL=21, HAL=15 | VAL (20 mg/kg.d→1625.8), HAL (0.2 mg/kg.d→15.5) | 3 | VAL=47.6, HAL=33.3 | n.a. | HAL – EPS | |

| Tohen (2002) | H, 18–65 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | VAL=123, OLZ=125 | VAL (750→1554.1 or 83.9 μg/ml), OLZ (15→16.2), | 4 | Yes | VAL=42.3, OLZ=54.4 | VAL=34.1, OLZ=47.2 | VAL – nausea, ↓ platelets OLZ – somnolence, dry mouth, ↑ appetite, tremor, speech disorder, rigidity, ↑ALT |

| Wagner (2009) | O, 10–17 yr, AM (DSM-IV-TR), YMRS≥20 | 4 | VAL=76, PLA=74 | VAL (15 mg/kg.d→1286) | 4 | Yes | VAL=24, PLA=23 | VAL=16, PLA=19 | VAL – nausea, abdominal pain, ↑ weight, ↓ platelets, ↑ serum ammonia |

| Kushner (2006) – PDMD-004, –005, –006, –008 | H, ≥16 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | TOP=433, PLA=427 | TOP (50→400) | n.a. | Yes | TOP=27, PLA=28 | TOP=24, PLA=23 | TOP – headache, paresthesia, ↓ appetite Li – diarrhoea, tremor |

| McIntyre (2005) | ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | HAL=99, QUE=101, PLA=100 | HAL (5.2), QUE (400→559) | 4 | Yes | HAL=56.1, QUE=42.6, PLA=35 | HAL=36.7, QUE=27.7, PLA=24 | HAL – tremor, akathisia, EPS QUE – somnolence |

| Smulevich (2005) | ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), MRS≥20 | 3 | HAL=144, RIS=154, PLA=140 | HAL (8.0), RIS (4.2) | 4 | Yes | HAL=47, RIS=48, PLA=33 | n.a. | RIS – EPS, hyperkinesia, somnolence, hypertonia, ↑ prolactinb HAL – EPS, hyperkinesia, tremor, hypertonia |

| Vieta (2008) | H, ≥18 yr, overweight, AM (DSM-IV-TR), MRS≥14 | 3 | HAL=171, ZIP=178, PLA=88 | HAL (8→16), ZIP (80→116.2) | 4 | Yes | HAL=54.7, ZIP=36.9, PLA=20.5 | HAL=31.9, ZIP=22.7 | ZIP – EPS, akathisia, dyspepsia, ↑ weight, headache HAL – EPS, akathisia, somnolence, dystonia, dizziness, hypotonia, anxiety, tremor, depression, hypokinesia |

| Young (2009) | ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV-TR), YMRS≥20 | 3 | HAL=165, ARI=167, PLA=153 | HAL (5→8.5), ARI (15→23.6) | 4 | Yes | HAL=49.7, ARI=47, PLA=38.2 | HAL=45.3, ARI=44, PLA=36.8 | HAL – EPS, akathisia, muscle rigidity, ↑ prolactin ARI – insomnia, akathisia, EPS |

| Tohen, 2003 | H & OP, ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 6 | HAL=219, OLZ=234 | HAL (10→7.1), OLZ (15→15) | 4 | Yes | HAL=62, OLZ=55 | HAL=46.1, OLZ=52.1 | OLZ – somnolence, ↑ weight, dizziness, fever HAL – salivation, EPS, akathisia, tremor, hypertonia, dystonia, dyskinesia |

| Vieta (2005) | ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | HAL=172, ARI=175 | HAL (10→11.6), ARI (10→22.6) | 4 | Yes | HAL=42.6, ARI=50.9 | HAL=31, ARI=35 | ARI – insomnia HAL – EPS, akathisia, ↑ prolactin |

| Keck (2003a) | H, ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | ARI=123, PLA=120 | ARI (30→27.9) | 4 | Yes | ARI=40, PLA=19 | n.a. | ARI – nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, constipation, somnolence, EPS, akathisia |

| Sachs (2006) | ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV-TR), YMRS≥20 | 3 | ARI=137, PLA=135 | ARI (30→27.7) | 4 | Yes | ARI=53, PLA=32 | n.a. | ARI – constipation, dyspepsia, nausea, somnolence, akathisia |

| Tohen (1999) | H, 18–65 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | OLZ=70, PLA=69 | OLZ (10→14.9) | 4 | Yes | OLZ=49, PLA=24 | n.a. | OLZ – somnolence, dry mouth, dizziness, ↑weight |

| Tohen (2000) | H, 18–70 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 4 | OLZ=54, PLA=56 | OLZ (15→16.4) | 4 | Yes | OLZ=64.8, PLA=42.9 | OLZ=61.1, PLA=35.7 | OLZ – somnolence |

| Tohen (2007) | H, 13–17 yr, AM (DSM-IV-TR), YMRS≥20 | 3 | OLZ=107, PLA=54 | OLZ (2.5→10.7) | 4 | Yes | OLZ=48.6, PLA=22.2 | OLZ=35.2, PLA=11.1 | OLZ – somnolence, ↑ weight, sedation |

| Perlis (2006) | H, 18–70 yr, AM (DSM-IV-TR), YMRS≥20 | 3 | OLZ=165, RIS=164 | OLZ (14.7), RIS (3.9) | 4 | Yes | OLZ=62, RIS=59.5 | OLZ=38.5, RIS=28.5 | OLZ – dry mouth, ↑ weight RIS – anxiety, joint stifiness, ↑ prolactin |

| Hirschfeld (2004) | ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 | 3 | RIS=125, PLA=134 | RIS (4.1) | 5 | Yes | RIS=43, PLA=24 | RIS=38, PLA=20 | RIS – somnolence, EPS, hyperkinesia, dyspepsia, nausea, ↑ prolactin, ↑ weight |

| Khana (2005); Gopal (2005) | ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), YMRS≥20 (mean score V1 =37) | 3 | RIS=146, PLA=144 | RIS (5.6) | 4 | Yes | RIS=73, PLA=36 | RIS=42, PLA=13 | RIS – EPS, tremor, dystonia, ↑ prolactinc |

| Keck (2003b) | H, ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), MRS≥14 | 3 | ZIP=131, PLA=66 | ZIP (80→130) | 3 | Yes | ZIP=50, PLA=35 | n.a. | ZIP – somnolence, headache, dizziness, hypertonia, akathisiad |

| Potkin (2005) | H, ≥18 yr, AM (DSM-IV), MRS≥14 | 3 | ZIP=137, PLA=65 | ZIP (80→112) | 4 | Yes | ZIP=46, PLA=29 | n.a. | ZIP – somnolence, EPS, dizziness, tremord |

| Calabrese (1999) | ≥18 yr, MDE (DSM-IV), HAMD≥18 | 7 | LAM50=64, LAM200=63, PLA=65 | LAM50(25→50), LAM200 (25→200) | 4 | Yes | LAM50=45, LAM200=51, PLA=37 | n.a. | LAM200 – headache |

| Calabrese (2008); Geddes (2009) – SCA40910 | ≥18 yr, MDE (DSM-IV), HAMD≥18 | 8 | LAM200=133, PLA=124 | LAM200 (25→200) | n.a. | Yes | LAM200=41.4, PLA=37.9 | n.a. | LAM200 – xerostomia |

| Calabrese (2008); Geddes (2009) – SCA30924 | ≥18 yr, MDE (DSM-IV), HAMD≥18 | 8 | LAM200=131, PLA=128 | LAM200 (25→200) | n.a. | Yes | LAM200=45.5, PLA=40 | LAM200=26.8, PLA=30 | LAM200 – diarrhoea, somnolence, dizziness, rash |

| Thase (2008) – CN138-096 | O, 18–65 yr, MDE (DSM-IV-TR), HAMD≥18 | 8 | ARI=186, PLA=188 | ARI (10→30) | 4 | Yes | ARI=43.2, PLA=39 | ARI=30.2, PLA=27.8 | ARI – akathisia, insomnia, nausea, fatigue, restlessness, dry mouth, vomiting, ↑ appetite, back pain |

| Thase (2008) – CN138-146 | O, 18–65 yr, MDE (DSM-IV-TR), HAMD≥18 | 8 | ARI=187, PLA=188 | ARI (10→30) | 4 | Yes | ARI=44.6, PLA=44.3 | ARI=25.7, PLA=29 | ARI – akathisia, nausea, fatigue, restlessness, anxiety, vomiting, ↑ appetite |

| Tohen (2003b) – 3077a S1 | ≥18 yr, MDE (DSM-IV), MADRS≥20 | 8 | OLZ=181, PLA=182 | OLZ (9.7) | 4 | Yes | OLZ=43.6, PLA=37.6 | OLZ=55, PLA=46.3 | OLZ – ↑appetite, ↑ weight, ↑ Chol, asthenia, dry mouth, somnolence |

| Tohen (2003b) – 3077a S2 | ≥18 yr, MDE (DSM-IV), MADRS≥20 | 8 | OLZ=169, PLA=174 | OLZ (9.7) | 4 | Yes | OLZ=53.3, PLA=34.7 | OLZ=57, PLA=44 | Combined data on Tohen (2003) above |

| MacFadden (2005); Calabrese (2005) | O, 18–65 yr, MDE (DSM-IV), HAMD≥20 | 8 | QUE300=116, QUE600=114, PLA=112 | QUE300 (50→300), QUE600 (50→600) | 4 | Yes | QUE300=62, QUE600=64, PLA=33 | Combined data on Weisler (2008) below | Combined data on Weisler (2008) below |

| Weisler (2008)e; Thase (2006) | O, 18–65 yr, MDE (DSM-IV-TR), HAMD≥20 | 8 | QUE300=104, QUE600=101, PLA=110 | QUE300 (50→300), QUE600 (50→600) | 4 | Yes | QUE300=59.6, QUE600=58.4, PLA=44.5 | QUE300=53.6, QUE600=55.3, PLA=31.5 | QUE300/600 – dry mouth, somnolence, sedation, dizziness, constipation, EPS, ↑ weight |

ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AM, acute mania; ARI, aripiprazole; CCMD-3, Chinese Classification and Diagnosis Criteria of Mental Disorder, 3rd version; Chol, cholesterol; EPS, extrapyramidal symptoms; ER-CBZ, extended-release carbamazepine capsules; GI, gastrointestinal; Glu, glucose; HAL, haloperidol; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; H, hospitalization; LAM, lamotrigine; LAM50, lamotrigine 50 mg/day; LAM200, lamotrigine 200 mg/d; Li, lithium; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDE, major depressive episode; MRS, Mania Rating Scale; n.a., non-available; O, outpatients; OLZ, olanzapine; OXC, oxcarbazepine; PLA, placebo; QUE, quetiapine; QUE300, quetiapine 300 mg/d; QUE600, quetiapine 600 mg/d; RCT, randomized clinical trial; RIS, risperidone; SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; TGl, triglycerides; TOP, topiramate 400 mg/d; TSH, thyroid stimulant hormone; VAL, valproate/divalproex; VER, verapamil; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; ZIP, ziprasidone.

RCT quality using Jadad et al. (1996) criteria (0=high chance of bias to 5=very low chance of bias) based on three questions: (1) was the study described as randomized? (2) Was the study described as double-blind? (3) Was there a description of withdrawals and dropouts?

No prolactin values reported.

Includes data from three participants of a site withdrawn because of concerns about quality data.

Mean prolongation of QTc (11 ms and 10.1 ms per trial): ZIP>PLA (no percentages informed).

Calculation based on the MacFadden et al. (2005) data.

Included studies were heterogeneous with respect to inclusion of patients with/without a rapid-cycling course, manic/mixed states, presence/absence of psychotic symptoms, severity of mania, rates of study completion, and proportion of mood stabilizer-naive subjects. Almost all the included RCTs were sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, therefore, there were not enough non-industry-sponsored studies to explore differences related to funding source. Of note, for tamoxifen, an experimental medication for the treatment of acute mania, we found two small RCTs (Yildiz et al. 2008; Zarate et al. 2007) including 40 patients treated with tamoxifen (dose range 40–80 mg/d) with a 7.46 (95% CI 1.90–29.32) higher chance of response and similar risk of discontinuation due to AEs than patients treated with placebo (n=34). Some analyses suggested marginal differences in favour of the MDR or the comparator. In these cases we decided to use the term ‘possibly’ to note that the difference was not conclusive.

We considered each MDR separately:

Lithium

We found (Fig. 2; Tables 1 and 2) six RCTs (Bowden et al. 1994, 2005; Keck et al. 2009; Li et al. 2008; Niufan et al. 2008; Singh, 2008). Patients treated with lithium (n=294) had a 1.65 (95% CI 1.23–2.21, I2=40%) higher chance of response, but possibly a greater risk of discontinuation due to AEs than patients treated with placebo (n=336). Inclusion of a combined analysis with two RCTs comparing lithium vs. placebo (Kushner et al. 2006) did not significantly change the RR of response (1.61, 95% CI 1.36–1.91, I2=12%). In comparison with other MDRs (n=503), patients treated with lithium (n=467) had a 0.90 (95% CI 0.81–1.00, I2=0%) lower chance of response.

Fig. 2.

Random risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for response rates with a monotherapy drug regimen (MDR) vs. placebo in the treatment of acute manic episodes. Response is defined as a reduction ≥50% in the baseline total score in the primary efficacy measure after 3–6 wk of treatment. ER-CBZ, Extended-release carbamazepine capsules; M-H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Table 2.

Secondary efficacy and safety measures of randomized trials using monotherapeutic drug regimen in patients with a bipolar disorder type I

| MDR and comparator | NNT response (95% CI) | NNT remission (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) | Relative risk of discontinuation due to any cause (95% CI) [I2] | Relative risk of discontinuation due to AE (95% CI) [I2] | Relative risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy (95% CI) [I2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manic/mixed episode | |||||||

| Li | PLA | 5 (3–8) | 6 (3–8) | 26 ( −27 to 79) | 0.78 (0.52–1.18) [84%] | 1.74 (1.00–3.02) [0%] | 0.53 (0.29–0.98) [67%] |

| MDR | −23 ( −56 to 11) | −23 ( −59 to 13) | −11 ( −18 to −3) | 1.25 (0.91–1.72) [61%] | 1.03 (0.65–1.64) [1%] | 1.36 (0.69–2.68) [55%] | |

| EC-CBZ | PLA | 4 (3–5) | n.a. | 4 (3–5) | 0.85 (0.69–1.03) [0%] | 1.97 (1.04–3.74) [0%] | 0.44 (0.20–1.00) [65%] |

| OXC | PLA | 4 (1–7) | n.a. | 9 ( −2 to 20) | 0.84 (0.52–1.35)a | 5.31 (1.23–22.93)a | 0.41 (0.17–1.00)* |

| VAL | PLA | 9 (4–14) | 12 (3–22) | 9 (4–14) | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) [26%] | 2.42 (1.28–4.56) [0%] | 0.63 (0.43–0.92) [27%] |

| MDR | −31 ( −99 to 36) | −12 ( −22 to −2) | −132 ( −∞ to ∞) | 0.93 (0.81–1.07) [0%] | 0.56 (0.32–0.98) [0%] | 1.01 (0.66–1.56) [0%] | |

| HAL | PLA | 5 (4–7) | 10 (2–17) | 2 (2–3)a | 0.82 (0.67–1.01) [18%] | 1.19 (0.40–3.53) [79%] | 0.52 (0.22–1.26) [77%] |

| MDR | 22 (1–44) | 118 ( −531 to 767) | 5 (4–7) | 1.15 (0.95–1.40) [62%] | 1.55 (0.96–2.48) [67%] | 0.72 (0.42–1.22) [69%] | |

| ARI | PLA | 7 (4–9) | 10 (2–19) | 8 (3–12) | 0.98 (0.83–1.17) [0%] | 1.21 (0.84–1.75) [7%] | 0.67 (0.33–1.38) [72%] |

| MDR | 41 ( −65 to 148) | 124 ( −∞ to ∞) | −3 ( −4 to −2) | 0.86 (0.65–1.14) [76%] | 0.86 (0.33–2.24) [89%] | 1.46 (0.72–2.95) [68%] | |

| OLZ | PLA | 6 (3–9) | 7 (3–12) | 6 (3–10) | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) [34%] | 1.93 (0.48–7.72) [28%] | 0.57 (0.42–0.77) [0%] |

| MDR | 57 ( −102 to 215) | 13 (5–22) | 15 ( −4 to 35) | 0.86 (0.69–1.07) [62%] | 1.01 (0.59–1.72) [44%] | 0.93 (0.66–1.31) [0%] | |

| QUE | PLA | 6 (3–9) | 7 (3–11) | n.a. | 0.66 (0.39–1.10) [78%] | 1.59 (0.48–5.25)a | 0.43 (0.21–0.87)* |

| MDR | −88 ( −724 to 548) | 32 ( −49 to 114) | 11 ( −5 to 26)a | 0.76 (0.38–1.50) [59%] | 0.62 (0.31–1.25) [0%] | 0.88 (0.36–2.17) [37%] | |

| RIS | PLA | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–6) | n.a. | 0.66 (0.41–1.08) [67%] | 1.18 (0.62– 2.27) [0%] | 0.44 (0.29–0.65) [0%] |

| MDR | −108 ( −1013 to 797) | −10 ( −20 to 1) | n.a. | 1.43 (1.04–1.97) [0%] | 1.51 (0.77–2.99) [0%] | 1.27 (0.53–3.02) [0%] | |

| ZIP | PLA | 6 (3–9) | n.a. | 6 (3–8) | 0.84 (0.73–0.96) [0%] | 2.40 (1.01–5.68) [0%] | 0.56 (0.44–0.72) [0%] |

| MDR | −6 ( −9 to −2)a | −10 ( −20 to −1) | −6 ( −10 to −3)a | 1.07 (0.89–1.29)a | 0.45 (0.27–0.78)a | 2.24 (1.41–3.57)a | |

| MS | PLA | 6 (5–8) | 9 (5–12) | 11 (6–16) | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) [65%] | 2.07 (1.46–2.93) [0%] | 0.55 (0.41–0.74) [44%] |

| SGA | PLA | 6 (5–7) | 8 (6:10) | 7 (5–10) | 0.87 (0.79–0.95) [0%] | 1.36 (1.03–1.79) [0%] | 0.55 (0.46–0.65) [16%] |

| MDR | PLA | 6 (5–7) | 7 (5–8) | 9 (6–12) | 0.81 (0.73–0.90) [51%] | 1.57 (1.22–2.03) [18%] | 0.55 (0.47–0.63) [30%] |

| Bipolar depressive episode | |||||||

| LAM | PLA | 16 ( −4 to 36) | −34 ( −159 to 91)a | 511 ( −∞ to ∞) | 1.35 (0.85–2.14) [0%] | 0.79 (0.38–1.62) [0%] | 1.10 (0.80–1.51) [51%] |

| ARI | PLA | 45 ( −100 to 190) | −174 ( −∞ to ∞) | 14 ( −2 to 29)* | 2.10 (1.32–3.35) [0%] | 0.45 (0.23–0.88) [0%] | 1.35 (1.13–1.63) [0%] |

| OLZ | PLA | 8 (3–14) | 9 (2–16) | n.a. | 0.72 (0.59–0.88) [63%] | 1.82 (1.06–3.13)b | 0.62 (0.48–0.80) [0%] |

| QUE | PLA | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6)** | n.a. | 1.01 (0.83–1.22)a | 1.95 (1.15–3.30)a | 0.18 (0.09–0.37)a |

| SGA | PLA | 8 (5–10) | 9 (6–13) | n.a. | 0.99 (0.73–1.32) [90%] | 1.97 (1.47–2.64) [0%] | 0.46 (0.29–0.71) [64%] |

| MDR | PLA | 9 (6–12) | 10 (6–15) | n.a. | 1.02 (0.81–1.28) [86%] | 1.77 (1.38–2.26) [0%] | 0.51 (0.36–0.73) [46%] |

ARI, Aripiprazole; CBZ, carbamazepine; CI, confidence interval; ER-CBZ, extended-release carbamazepine capsules; Li, lithium; LAM, lamotrigine; MDR, monotherapy drug regime; MS, mood stabilizers; n.a., non-available; NNH, number needed to harm; NNT, number needed to treat; OLZ, olanzapine; OXC, oxcarbazepine; PLA, placebo; QUE, quetiapine; RIS, risperidone; SGA, second-generation antipsychotics; VAL, valproate/divalproex; VER, verapamil; ZIP, ziprasidone.

Based on one RCT.

Based on combined data from two RCTs.

Carbamazepine

Two RCTs with the extended release formulation of carbamazepine (ER-CBZ) (Weisler et al. 2004, 2005) were included. Patients treated with ERCBZ (n=221) had a 2.02 (95% CI 1.56–2.62, I2=0%) higher chance of response and possibly a lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, but a greater risk of discontinuation due to AEs than patients treated with placebo (n=218). The NNH analysis suggested that four patients treated with carbamazepine instead of placebo are needed to observe an additional AE.

Oxcarbazepine

One 7-wk RCT with the use of oxcarbazepine in children and adolescents was included (Wagner et al. 2006). Although it was reported that oxcarbazepine did not significantly improve YMRS scores at endpoint compared with placebo, we found that patients treated with oxcarbazepine (n=59) had a 1.56 (95% CI 1.13–2.16) higher chance of response, although a greater risk of discontinuation due to AEs than patients treated with placebo (n=57). Nine patients are needed to observe an additional AE if patients are treated with oxcarbazepine instead of placebo.

Valproate/divalproex

Seven RCTs were included (Bowden et al. 1994, 2006; DelBello et al. 2006; McElroy et al. 1996; Tohen et al. 2002, 2008; Wagner et al. 2009). Patients treated with valproate (n=555) had a 1.39 (95% CI 1.16–1.65, I2=0%) higher chance of response, a 1.27 (95% CI 1.05–1.54) higher chance of remission (I2=72%) and a lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, but had a greater risk of discontinuation due to AEs than patients treated with placebo (n=457). Nine patients are needed to observe an additional AE if patients are treated with valproate instead of placebo. In comparison with other MDRs (n=416), patients treated with valproate (n=439) had a similar chance of response, but a lower risk of discontinuation due to AEs. The exclusion of RCTs in children and adolescents (DelBello et al. 2006; Wagner et al. 2009) does not change the RR for either response vs. placebo or remission vs. other MDRs.

Haloperidol

Seven RCTs with haloperidol were included (McElroy et al. 1996; McIntyre et al. 2005; Smulevich et al. 2005; Tohen et al. 2003a; Vieta et al. 2005, 2008; Young et al. 2009). Patients treated with haloperidol (n=579) had a 1.31 (95% CI 1.04–1.65, I2=0%) higher chance of remission and a 1.63 (95% CI 1.25–2.12) higher chance of response (I2=64%) than patients treated with placebo (n=481). Although patients treated with haloperidol showed no increased risk of discontinuation for any cause or AE, a study showed that only two patients treated with haloperidol instead of placebo are needed to observe an additional AE. In comparison with other MDRs (n=985), patients treated with haloperidol (n=1030) showed a similar chance of response (I2=62%) or remission (I2=51%). The NNT analyses indicated that five patients treated with haloperidol instead of another MDR are needed to observe an additional AE.

Aripiprazole

Five RCTs were included (Keck et al. 2003a, 2009; Sachs et al. 2006; Vieta et al. 2005; Young et al. 2009). Patients treated with aripiprazole (n=582) had a 1.50 (95% CI 1.22–1.84, I2=44%) higher chance of response and a 1.28 (95% CI 1.05–1.57, I2=0%) higher chance of remission than patients treated with placebo (n=573). Eight patients treated with aripiprazole instead of placebo are needed to observe an additional AE. In comparison with other MDRs (n=497), patients treated with aripiprazole (n=497) had a similar chance of response and remission.

Olanzapine

Eight RCTs were included (Niufan et al. 2008; Perlis et al. 2006; Tohen et al. 1999, 2000, 2002, 2003a, 2007a, 2008). Patients treated with olanzapine (n=446) had a 1.62 (95% CI 1.27–2.08, I2=27%) higher chance of response, a 1.68 (95% CI 1.06–2.64) higher chance of remission (I2=62%), and had a lower risk of discontinuation due to any cause or lack of efficacy than patients treated with placebo (n=284). Six patients treated with olanzapine instead of placebo are needed to observe an additional AE. In comparison with other MDRs (n=778), patients treated with olanzapine (n=808) had a 1.17 (95% CI 1.06–1.30, I2=0%) higher chance of remission, and a similar chance of response.

Quetiapine

Four RCTs were included (Bowden et al. 2005; DelBello et al. 2006; Li et al. 2008; McIntyre et al. 2005). Patients treated with quetiapine (n=208) had a similar chance of response (1.52, 95% CI 0.97–2.37, I2=68%) and remission (1.59, 95% CI 0.86–2.94, I2= 73%), but a lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy than patients treated with placebo (n=197) during the first 3 wk of treatment. However, the NNT was six (95% CI 3–9) and seven (95% CI 3–11) for response and remission vs. placebo, respectively. When data for the 12-wk studies were included, patients treated with quetiapine had a higher chance of response and remission vs. placebo. Differences between 3 and 12 wk may be due to the dose titration design in RCTs with quetiapine where the therapeutic dose is reached several days after the first study visit. In comparison with other MDRs (n=299), patients treated with quetiapine (n=310) had a similar chance of response (I2=69%) and remission (I2=69%).

Risperidone

Data from three RCTs available in four publications were included (Gopal et al. 2005; Hirschfeld et al. 2004; Khanna et al. 2005; Smulevich et al. 2005). Patients treated with risperidone (n=425) had a 1.77 (95% CI 1.44–2.17, I2=33%) higher chance of response, a 2.43 (95% CI 1.47–400) higher chance of remission (I2=63%), and a lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy in comparison with patients treated with placebo (n=418). In comparison with other MDRs (n=309), patients treated with risperidone (n=318) had a similar chance of response and remission, and a similar risk of discontinuation due to AEs, but a higher risk of discontinuation due to any cause.

Ziprasidone

Three RCTs were included (Keck et al. 2003b; Potkin et al. 2005; Vieta et al. 2008). Patients treated with ziprasidone (n=446) had a 1.58 (95% CI 1.25–2.00, I2=0%) higher chance of response and a lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or any cause, but a greater risk of discontinuation due to AE than those patients treated with placebo (n= 219). Six patients treated with ziprasidone instead of placebo are needed to observe an additional AE. Data from one RCT indicates that patients treated with haloperidol (n=171) had a 1.48 (95% CI 1.17–1.87) higher chance of response and a 1.43 (95% CI 1.01–2.03) higher chance of remission than patients treated with ziprasidone (n=178), but a 2.53 (95% CI 1.08–5.94) higher risk of discontinuation due to AEs.

MDRs for acute depressive episodes

Many mood stabilizers (Ballenger & Post, 1980; Baron et al. 1975; Davis et al. 2005; Donnelly et al. 1978; Fieve et al. 1968; Geddes et al. 2009 (Trial SCAA2010); Ghaemi et al. 2007; Goodwin et al. 1969, 1972; Mendels, 1976; Noyes et al. 1974; Post et al. 1986; Stokes et al. 1971), antidepressants (Baumhackl et al. 1989; Cohn et al. 1989; Grossman et al. 1999; Himmelhoch et al. 1991; Silverstone et al. 2001; Thase et al. 1992), antipsychotics (DelBello et al. 2009) or other medications (Smeraldi et al. 1999) have been evaluated as monotherapies in bipolar depression. Not one of those RCTs fulfilled our study criteria therefore they were all excluded from the present analyses.

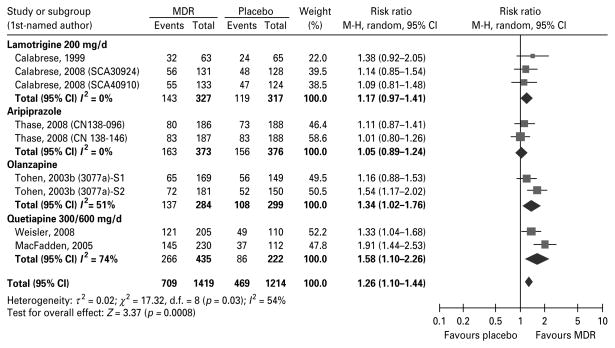

Nine RCTs fulfilling the study criteria on bipolar depression were included (Table 2). The overall RR for meta-analysis for response in bipolar depressed patients treated with MDR (n=1419) compared with placebo (n=1214) was 1.26 (95% CI 1.11–1.44, I2= 54%) (Fig. 3). Further, patients treated with MDR had a 0.51 (95% CI 0.36–0.73, I2=46%) lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, but a 1.77 (95% CI 1.38–2.26, I2=0%) greater risk of discontinuation due to AEs than those patients treated with placebo. We did not observe a significant difference vs. placebo for the RR for remission, nor for discontinuation due to any cause. Again, analyses including those trials with small sample sizes (n=3) did not significantly change the final results but increased their heterogeneity. The included studies were all sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry. They were heterogeneous with respect to inclusion of subjects with history of a rapidcycling course or manic/mixed states, proportion of people with/without psychotic symptoms, severity of depression, rates of study completion, and proportion of mood stabilizer-naive or antidepressant-naive subjects.

Fig. 3.

Random risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for response rates with a monotherapy drug regimen (MDR) vs. placebo in the treatment of depressive episodes Response is defined as a reduction ≥50% in the baseline total score in the primary efficacy measure after 7–10 wk of treatment. M-H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Considering each MDR separately, we did not find any trials fulfilling our inclusion criteria to confirm or reject any potential role for valproate as monotherapy in acute bipolar depression, although a small RCT suggests better remission rates for valproate vs. placebo (Davis et al. 2005). For other MDRs we found (Fig. 3; Tables 1 and 2) the following:

Lamotrigine

Data from three RCTs available in five publications/data sources were considered for analysis (Calabrese et al. 1999, 2008; Geddes et al. 2009; Trials SCA40910, SCA30924). We found that patients treated with lamotrigine (≥200 mg/d) (n= 327) had a similar chance of response (I2=0%) and remission (one study), and a similar risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or AEs than those patients treated with placebo (n=317). Similar results were observed when we included the BP I and BP II patients, and all the doses evaluated for lamotrigine.

Aripiprazole

Data from two RCTs available in three publications/data sources were included (Thase et al. 2008; Trials CN138-096, CN138-146). Patients treated with aripiprazole (n=373) had a similar chance of response (I2=0%) and remission (I2=0%), but greater risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or any cause than those patients treated with placebo (n=376).

Olanzapine

Data from two RCTs available in three publications/data sources were included (Tohen et al. 2003b; Trial 3077a). Patients treated with olanzapine (n=350) had a 1.34 (95% CI 1.02–1.76, I2=51%) higher chance of response, and a 1.24 (95% CI 1.05–1.46, I2=0%) higher chance of remission, and a lower risk of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, but a greater risk of discontinuation due to AEs than those patients treated with placebo (n=356).

Quetiapine

Data from two RCTs available in four publications/data sources were included (Calabrese et al. 2005; MacFadden et al. 2005; Thase et al. 2006; Weisler et al. 2008). Patients treated with quetiapine (n=435) had a 1.58 (95% CI 1.10–2.26, I2=74%) higher chance of response, a 1.73 (95% CI 1.40–2.14) (combined data) higher chance of remission, and a lower risk of discontinuation due lack of efficacy, but a greater risk of discontinuation due to AEs than those patients treated with placebo (n=222). Similar results were observed when we evaluated together the BP I and BP II patients in terms of response, remission or discontinuations due to lack of efficacy or AE.

Discussion

We found in most studies that MDRS are efficacious in the treatment of acute manic episodes. In these studies the entire range of confidence intervals exceeds the cut-off point below which the effect size is defined as no different to placebo (Fig. 2). We also found that it is necessary to treat six (95% CI 5–7) or seven (95% CI 5–8) patients to observe a significant difference in response or remission rates, respectively, with MDR over placebo in the treatment of acute manic episodes (Table 2). Finally, a combined analysis with several RCTS suggests that topiramate is not efficacious in the treatment of acute mania (Kushner et al. 2006). In patients with acute manic episodes, study discontinuation due to AEs was significantly more likely to be observed with a MDR than with placebo, but study discontinuation due to lack of efficacy or discontinuation to any cause were significantly lower with SGAS than with placebo. Regarding the comparisons between an active compound against another MDR (usually lithium, valproate or haloperidol), we did not find significant differences in terms of response, remission, or discontinuation due to AEs, lack of efficacy, or discontinuation due to any cause.

Regarding acute bipolar depressive episodes, we found that only olanzapine and quetiapine showed response and/or remission rates superior to those reported with placebo (substantial heterogeneity was observed with both analyses), although the effect size for quetiapine in response was almost double that for olanzapine (Fig. 3). Early RCTs have shown significant therapeutic effects with lithium for bipolar depression (Thase & Sachs, 2000), but small samples and other methodological shortcomings limits the evidence for its use as a MDR for BP I depressed patients.

Although some patients with a bipolar depressive episode may certainly benefit from a MDR, the evidence is still limited and many BP I patients with a depressive episode appear to require the addition of another mood stabilizer (Kramlinger & Post, 1989) or an antidepressant (Tamayo et al. 2009; Tohen et al. 2003b; Young et al. 2000). Interestingly, some RCTs comparing a CDR with a MDR with no previous lack of response did not report statistical differences favouring the CDR in BP I-depressed patients (Amsterdam & Shults, 2005; Brown et al. 2006; Nolen & Bloemkolk, 2000). On the other hand, although the literature supports the efficacy of lamotrigine in preventing bipolar depressive relapses (Goodwin et al. 2004), it does not provide evidence to support the efficacy of this medication in the acute depressive phase of BP I patients. Recently, a review concluded that lamotrigine monotherapy did not demonstrate efficacy in the acute treatment of bipolar depression in four out of five RCTs (Calabrese et al. 2008). However, a meta-analysis with the same RCT, reported a statistically significant small effect size of depressive symptom benefit only in patients with a HAMD score >24 (Geddes et al. 2009).

The relevance of different therapeutic interventions for BP I and their efficacy must be evaluated based on the best available evidence. Unfortunately, the treatment of patients with BP I is usually complex, and many treatment interventions implemented by clinicians at times may not be evidence-based. A survey in an acute general psychiatric ward indicated that <65% of treatment decisions were based on evidence from RCTs (Goldner et al. 2001). Studies in which pharmacological treatment is allocated by any method other than randomization tend to show larger (and frequently false-positive) treatment effects than do RCTs. Randomization prevents biased assignment of treatment and confounders that are unknown or unmeasured (Chalmers et al. 1983). However, caution is needed in drawing clear-cut generalizations to clinical practice based on our analyses due to the heterogeneity in trial designs, the methodological quality of included trials, and the nature, timing, and dose of mood stabilizers or SGAs. Additionally, the fact that almost all the RCTs in the field of bipolar disorder are aimed at registration approval, there may be a gap between the evidence base of patients who participate in clinical trials and clinical populations (Vieta & Carné, 2005).

We examined the results from available studies to determine the possibility of publication bias or selective reporting bias. We additionally, compared the data published with that reported on the trial registry or at ‘ClinicalStudyResults.org’, and we excluded trials with small sample sizes that would tend to show larger estimates of the effects of the intervention. However, the quality of the studies varied and we were not blinded to their quality when determining their inclusion. Several analyses showed a heterogeneity statistic I2>50% that ‘may represent substantial heterogeneity’ (Deeks et al. 2008) and the funnel plot for each of them showed evidence of considerable asymmetry. As noted by Higgins et al. (2003), regarding heterogeneity, ‘inconsistency of studies’ results in a meta-analysis with reduced confidence of recommendations about treatment’. Additionally, although we examined the ‘ClinicalStudyResults.org’ webpage and several conference proceedings using a combination of hand and electronic searching, we cannot exclude the possibility that there are unpublished negative studies that we were unable to access.

In conclusion, although there are patients who are unresponsive to acute treatment with monotherapy, these results suggest that MDRs should be considered as a first therapeutic option for the treatment of nonrefractory manic episodes. This approach may result in the reduction of direct costs of medications, the number and magnitude of AEs and may improve treatment adherence and patient compliance (Grunze et al. 2009). For depressive episodes, the new data with SGAs (quetiapine and olanzapine) suggest that these MDR, especially quetiapine, are efficacious and well tolerated.

Acknowledgments

The views held by Dr Zarate do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Government.

Footnotes

Statement of Interest

Dr Tamayo was an employee of Eli Lilly Laboratories during the first analyses for this paper and has received honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, and Wyeth. Dr Zarate is supported by the intramural research program at the NIMH and has not received any industry funding in the past year. Dr Vieta is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM), is a consultant to and received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bristol–Myers, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Sano., has received grant or research support from Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, and Novartis, and has been on the advisory board of AstraZeneca, Bristol–Myers, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Organon, and Pfizer. Dr Vázquez is a consultant to and received honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche and Eli Lilly. Dr Tohen was an employee of Eli Lilly Laboratories during the planning and analyses of this paper and has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bristol–Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Wyeth. His spouse in an employee and stockholder of Eli Lilly.

References

- Amsterdam JD, Shults J. Comparison of fluoxetine, olanzapine, and combined fluoxetine plus olanzapine initial therapy of bipolar type I and type II major depression–lack of manic induction. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;87:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini RJ, Leahy L, Arcona S, Gause D, et al. Patterns of psychotropic drug prescription for U.S. patients with diagnoses of bipolar disorders. Psychiatry Services. 2007;58:85–91. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Post RM. Therapeutic effects of carbamazepine in affective illness: a preliminary report. Communications in Psychopharmacology. 1978;2:159–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Post RM. Carbamazepine in manic-depressive illness: a new treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137:782–790. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron M, Gershon ES, Rudy V, Jonas WZ, et al. Lithium carbonate response in depression. Prediction by unipolar/bipolar illness, average-evoked response, catechol-O-methyl transferase, and family history. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1975;32:1107–1111. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760270039003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumhackl U, Biziere K, Fischbach R, Geretsegger C, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of moclobemide compared with imipramine in depressive disorder (DSM-III): an Austrian double-blind, multicentre study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;6 (Suppl):78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Ichim L, Brook S. Olanzapine compared to lithium in mania: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;14:339–343. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Laje G, Olfson M, Marcus SC, et al. Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1005–1010. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, et al. Efficacy of divalproex vs. lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271:918–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden CL, Grunze H, Mullen J, Brecher M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study of quetiapine or lithium as monotherapy for mania in bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:111–121. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden CL, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Rubenfaer LM, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of divalproex sodium extended release in the treatment of acute mania. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:1501–1510. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradwejn J, Shriqui C, Koszycki D, Meterissian G. Double-blind comparison of the effects of clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1990;10:403–408. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199010060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D, Silverstone T, Cookson J. Carbamazepine compared to haloperidol in acute mania. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1989;4:229–238. doi: 10.1097/00004850-198907000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EB, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, Deldar A, et al. A 7-week, randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination versus lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:1025–1033. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cade JF. Lithium salts in the treatment of psychiatric excitement. Medical Journal of Australia. 1949;2:349. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.06241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Ascher JA, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60:79–88. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Huffman RF, White RL, Edwards S, et al. Lamotrigine in the acute treatment of bipolar depression: results of five double-blind, placebocontrolled clinical trials. Bipolar Disorders. 2008;10:323–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Keck PE, MacFadden W, Minkwitz M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1351–1360. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzoni PA, Berg PH, Kryzhanovskaya LA, Briggs SD, et al. Comparison of treatment-emergent extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with bipolar mania or schizophrenia during olanzapine clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:107–113. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers TC, Celano P, Sacks HS, Smith H., Jr Bias in treatment assignment in controlled clinical trials. New England Journal of Medicine. 1983;309:1358–1361. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312013092204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani A, Signoretti A, Barbui C. Review: antipsychotic plus mood stabiliser co-therapy is more effective than mood stabiliser mono-therapy at reducing acute bipolar mania. Evidence-Based Mental Health. 2007;10:83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HM, Berk M, Brook S. A randomized controlled single blind study of the efficacy of clonazepam and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Human Psychopharmacology. 1997;12:325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn JB, Collins G, Ashbrook E, Wernicke JF. A comparison of fluoxetine, imipramine and placebo in patients with bipolar depressive disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1989;4:313–322. doi: 10.1097/00004850-198910000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. British Medical Journal. 1995;310:452–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson J, Silverstone T, Wells B. Double-blind comparative clinical trial of pimozide and chlorpromazine in mania. A test of the dopamine hypothesis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1981;64:381–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1981.tb00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LL, Bartolucci A, Petty F. Divalproex in the treatment of bipolar depression: a placebo-controlled study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;85:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Altman D. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analysis. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. pp. 243–298. [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Chang K, Welge JA, Adler CM, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of quetiapine for depressed adolescents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2009;11:483–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Findling RL, Kushner S, Wang D, et al. A pilot controlled trial of topiramate for mania in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:539–547. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000159151.75345.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Kowatch RA, Adler CM, Stanford KE, et al. A double-blind randomized pilot study comparing quetiapine and divalproex for adolescent mania. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:305–313. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000194567.63289.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly EF, Goodwin FK, Waldman IN, Murphy DL. Prediction of antidepressant responses to lithium. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;135:552–556. doi: 10.1176/ajp.135.5.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Dickersin K, Smith GD. Problems and limitations in conducting systematic reviews. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman GD, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care. London: BMJ Books; 2001. pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN. Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. British Medical Journal. 1997;315:1533–1537. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7121.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieve RR, Platman SR, Plutchik RR. The use of lithium in affective disorders, I: acute endogenous depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1968;25:487–491. doi: 10.1176/ajp.125.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL, Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, McNamara NK, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of divalproex monotherapy in the treatment of symptomatic youth at high risk for developing bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68:781–788. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis KN, Vieta E. Treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of available data and clinical perspectives. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;11:999–1029. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman TW, Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, Lesem MD, et al. A double-blind comparison of valproate and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:108–111. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel PE, Stancer HC, Persad E. A comparison of haloperidol, lithium carbonate and their combination in the treatment of mania. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1980;2:279–288. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(80)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Treviño ES, Overall JE, Hollister LE. Verapamil versus lithium in acute mania. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:121–122. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes JR, Calabrese JR, Goodwin GM. Lamotrigine for treatment of bipolar depression: independent meta-analysis and metaregression of individual patient data from five randomised trials. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;194:4–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN, Gilmer WS, Goldberg JF, Zablotsky B, et al. Divalproex in the treatment of acute bipolar depression: a preliminary double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68:1840–1844. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Brooks JO, 3rd, Kurita K, Hoblyn JC, et al. Depressive illness burden associated with complex polypharmacy in patients with bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70:155–162. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldner EM, Abass A, Leverette JS, Haslam DR. Evidence-Based Psychiatric Practice: Implications for Education and Continuing Professional Development. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Psychiatric Association Current Position Papers and Guidelines; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves N, Stoll KD. Carbamazepine in manic syndromes. A controlled double-blind study. Nervenarzt. 1985;56:43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Murphy DL, Bunney WE., Jr Lithium-carbonate in depression and mania: a longitudinal double blind study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1969;21:486–496. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1969.01740220102012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Murphy DL, Dunner DL, Bunney WE., Jr Lithium response in unipolar versus bipolar depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1972;129:44–47. doi: 10.1176/ajp.129.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GM, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Grunze H, et al. A pooled analysis of 2 placebo-controlled 18-month trials of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance in bipolar I disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:432–441. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal S, Steffens DC, Kramer ML, Olsen MK. Symptomatic remission in patients with bipolar mania: results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone monotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:1016–1020. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman F, Potter WZ, Brown EA, Maislin G. A double-blind study comparing idazoxan and bupropion in bipolar depressed patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;56:237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, Bowden C, et al. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2009;10:85–116. doi: 10.1080/15622970902823202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison TS, Keating GM. Extended-release carbamazepine capsules in bipolar I disorder. CNS Drugs. 2005;19:709–716. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519080-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelhoch JM, Thase ME, Mallinger AG, Houck P. Tranylcypromine versus imipramine in anergic bipolar depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:910–916. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.7.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RM, Keck PE, Jr, Kramer M, Karcher K, et al. Rapid antimanic effect of risperidone monotherapy: a 3-week multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1057–1065. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichim L, Berk M, Brook S. Lamotrigine compared with lithium in mania: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;12:5–10. doi: 10.1023/a:1009066725103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicak PG, Sharma RP, Pandey G, Davis JM. Verapamil for the treatment of acute mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:972–973. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G, Gershon S, Hekiman LJ. Controlled evaluation of lithium and chlorpromazine in the treatment of manic states: an interim report. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1968;9:563–573. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(68)80053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE, Jr, Marcus R, Tourkodimitris S, Ali M, et al. A placebo-controlled double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003a;160:1651–1658. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE, Jr, Versiani M, Potkin S, West SA, et al. Ziprasidone in the treatment of acute bipolar mania: a three-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003b;160:741–748. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE, Orsulak PJ, Cutler AJ, Sanchez R, et al. Aripiprazole monotherapy in the treatment of acute bipolar I mania: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and lithium-controlled study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;112:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna S, Vieta E, Lyons B, Grossman F, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;187:229–234. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowatch RA, Suppes T, Carmody TJ, Bucci JP, et al. Effect size of lithium, divalproex sodium, and carbamazepine in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:713–720. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramlinger KG, Post RM. The addition of lithium to carbamazepine. Antidepressant efficacy in treatment-resistant depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:794–800. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810090036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo Y, Ichimaru S, Kawakita Y, Saito M, et al. Comparison of therapeutic effect on mania of sultopride hydrochloride with haloperidol using double-blind hnique. Rinsho Hyoka. 1987;15:15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Grochocinski VI, Cluss PA, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals in a bipolar disorder case registry. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63:120–125. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SF, Khan A, Lane R, Olson WH. Topiramate monotherapy in the management of acute mania: results of four double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8:15–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam RW, Kennedy SH. Using metaanalysis to evaluate evidence: practical tips and traps. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;50:167–174. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerer B, Moore N, Meyendor E, Cho SR, et al. Carbamazepine versus lithium in mania: a double-blind study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1987;48:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J, Chengappa KN, Brar JS, Gershon S, et al. Psychotropic drug prescription patterns among patients with bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2000;2:120–130. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Winokur G. The induction of mania: a natural history study with controls. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39:303–306. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290030041007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ma C, Wang G, Zhu X, et al. Response and remission rates in Chinese patients with bipolar mania treated for 4 weeks with either quetiapine or lithium: a randomized and double-blind study. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2008;24:1–10. doi: 10.1185/030079908x253933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyseng-Williamson KA, Perry CM. Aripiprazole: in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:367–376. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFadden W, Calabrese J, Suppes T, McCoy R, et al. Quetiapine in bipolar I depression: Double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Poster NR802, presented at the 158th APA Annual Meeting; Atlanta, GA. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Keck PE, Pope HG, Hudson JI, et al. Correlates of antimanic response to valproate. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1991;27:127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Keck PE, Stanton SP, Tugrul KC, et al. A randomized comparison of divalproex oral loading versus haloperidol in the initial treatment of acute psychotic mania. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1996;57:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Brecher M, Paulsson B, Huizar K, et al. Quetiapine or haloperidol as monotherapy for bipolar mania. A 12-week, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;15:573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendels J. Lithium in the treatment of depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1976;133:373–378. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishory A, Yaroslavsky Y, Bersudsky Y, Belmaker RH. Phenytoin as an antimanic anticonvulsant: a controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:463–465. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno RA, Hanna MM, Tavares SM, Wang YP. A double-blind comparison of the effect of the antipsychotics haloperidol and olanzapine on sleep in mania. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2007;40:357–366. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2007000300011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Rosen AM, Caracci G, Shukla S. Persistent tardive dyskinesia in bipolar patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:342–346. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800040052008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niufan G, Tohen M, Qiuqing A, Fude Y, et al. Olanzapine versus lithium in the acute treatment of bipolar mania: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;105:101–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen WA, Bloemkolk D. Treatment of bipolar depression, a review of the literature and a suggestion for an algorithm. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;1 (Suppl):11–17. doi: 10.1159/000054845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes R, Jr, Dempsey GM, Blum A, Cavanaugh GL. Lithium treatment of depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1974;15:187–193. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(74)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuma T, Inanaga K, Otsuki S, Sarai K, et al. Comparison of the antimanic efficacy of carbamazepine and chlorpromazine: a double-blind controlled study. Psychopharmacology. 1979;66:211–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00428308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, Itoh H, et al. Comparison of the antimanic efficacy of carbamazepine and lithium carbonate by double-blind controlled study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1990;23:143–150. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega HA, Hernandez CA, Jasso A, Hasfura CA. Carbamazepine vs. haloperidol in the treatment of manic episodes: a controlled clinical trial. Salud Mental. 1993;16:44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Baker RW, Zarate CA, Jr, Brown EB, et al. Olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of manic or mixed States in bipolar I disorder: a randomized, double-blind trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:1747–1753. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitti DB. Meta-Analysis, Meta-Analysis, Decision Analysis, and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Methods for Quantitative Synthesis in Medicine. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 83–85.pp. 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Platman SR. A comparison of lithium carbonate and chlorpromazine in mania. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1970;127:351–353. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, Hudson JI. Valproate in the treatment of acute mania. A placebo-controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:62–68. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Altshuler LL, Leverich GS, Frye MA, et al. Mood switch in bipolar depression: comparison of adjunctive venlafaxine, bupropion and sertraline. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:124–131. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.013045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Uhde TW, Roy-Byrne PP, Joffe RT. Antidepressant effects of carbamazepine. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;3:29–34. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Uhde TW, Roy-Byrne PP, Joffe RT. Correlates of antimanic response to carbamazepine. Psychiatry Research. 1987;21:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(87)90064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potkin SG, Keck PE, Jr, Segal S, Ice K, et al. Ziprasidone in acute bipolar mania. A 21-day randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled replication trial. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;25:301–310. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000169068.34322.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prien RF, Caffey EM, Jr, Klett CJ. Comparison of lithium carbonate and chlorpromazine in the treatment of mania. Report of the Veterans Administration and National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study Group. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1972;26:146–153. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750200050011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richy F, Ethgen O, Bruyere O, Deceulaer F, et al. The Internet Journal of Epidemiology. 2004. From sample size to effect-size: small study effect investigation (SSEi) p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs G, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder: a 3-week placebo-controlled study. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2006;20:536–546. doi: 10.1177/0269881106059693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356:1711–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal J, Berk M, Brook S. Risperidone compared with both lithium and haloperidol in mania: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Clinical Neuropharmacology. 1998;21:176–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shopsin B, Gershon S, Thompson H, Collins P. Psychoactive drug in mania. A controlled comparison of lithium carbonate, chlorpromazine, and haloperidol. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1975;32:34–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760190036004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone T on behalf of the Moclobemide Bipolar Study Group. Moclobemide vs. imipramine in bipolar depression: a multicentre double-blind clinical trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;104:104–109. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GP. A double blind comparative study of clinical efficacy of verapamil versus lithium in acute mania. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2008;12:303–308. doi: 10.1080/13651500802209670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small JG, Klapper MH, Milstein V, Kellams JJ, et al. Carbamazepine compared with lithium in the treatment of mania. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:915–921. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810340047006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeraldi E, Benedetti F, Barbini B, Campori E, et al. Sustained antidepressant effect of sleep deprivation combined with pindolol in bipolar depression: a placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:380–385. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, Cornelius V, Warnock A, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and metaanalysis of co-therapy vs. monotherapy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;115:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulevich AB, Khanna S, Eerdekens M, Karcher K, et al. Acute and continuation risperidone monotherapy in bipolar mania: a 3-week placebo-controlled trial followed by a 9-week double-blind trial of risperidone and haloperidol. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;15:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring G, Schweid D, Gray C, Steinberg J, et al. A double-blind comparison of lithium and chlorpromazine in the treatment of manic states. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1970;126:1306–1309. doi: 10.1176/ajp.126.9.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes PE, Shamoian CA, Stoll PM, Patton MJ. Efficacy of lithium as acute treatment of manic-depressive illness. Lancet. 1971;1:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91886-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storosum JG, Wohlfarth T, Schene A, Elferink A, et al. Magnitude of effect of lithium in short-term efficacy studies of moderate to severe manic episode. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9:793–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R, Sakuma A, Itoh K, Itoh H, et al. Comparison of efficacy of lithium carbonate and chlorpromazine in mania. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1975;32:1310–1318. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760280108010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo JM, Sutton VK, Mattei MA, Diaz B, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the combination of fluoxetine and olanzapine in outpatients with bipolar depression. An open-label, randomized, flexible-dose study in Puerto Rico. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;29:358–361. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181ad223f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, MacFadden W, Weisler RH, Chang W, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in bipolar I and II depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study (the BOLDER II study) Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;26:600–609. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000248603.76231.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]