Abstract

Background

Despite higher rates of stabbing and shooting violence among black men, healthcare systems have not demonstrated an efficacious response to these patients. This study describes challenges and promotive factors for engaging black male violence victims of violence with medical and mental healthcare.

Methods

Black male victims of stabbings and shootings were recruited through fliers and word of mouth, and were interviewed individually (n = 12) or in pairs (n = 4) using a semistructured guide. A racially diverse multidisciplinary team analyzed the data using Grounded Theory methods.

Results

Challenges to engagement with healthcare included the following: (1) Disconnect in the aftermath; e.g. participants reported not realizing they were seriously injured (“just a scratch” “poke”), were disoriented (“did not know where I was”), or were consumed with anger. (2) Institutional mistrust: blurred lines between healthcare and police, money-motivated care. (3) Foreshortened future: expectations they would die young. (4) Self-reliance: fix mental and substance abuse issues on their own. (5) Logistical issues: postinjury mental health symptoms, disability, and safety concerns created structural barriers to recovery and engagement with healthcare. Promotive factors included the following: (1) desire professionalism, open personality, and shared experience from clinicians; (2) turning points: injury or birth of a child serve as a “wake up call”; and (3) positive people, future-oriented friends and family.

Conclusions

For black male violence victims, medical treatment did not address circumstances of and reactions to injury. Policies delineating boundaries between medical care and law enforcement and addressing postinjury mental health symptoms, disability, and safety concerns may improve the recovery process.

Keywords: Black male, Community violence, Qualitative research

Hand gun and stabbing violence disproportionately affects young African American men in the United States.1,2 Although homicides are the most extreme health effect of violence, injuries, with their attendant physical and psychologic morbidity, greatly impact survivors.3,4

Despite the burden of violence on young black males, limited literature describes effective healthcare responses to shooting and stabbing violence. An opportunity exists to engage those injured from violence while receiving care in acute hospital settings. Existing hospital-based programs focus on case management approaches when working with violence survivors, often referring them for community-based services,5–8 such as education and vocational help.9 These programs showed reduced criminal activity and re-injury compared with patients receiving care as usual.6–8

Although the literature specifically examining the effectiveness of healthcare response to black male victims of violence is limited, there is an extensive literature outlining disparities in healthcare treatment among different racial and ethnic groups. For instance, an Institute of Medicine 2002 report suggested that aspects of the clinical encounter, patient preferences, physician stereotyping, and system structure may contribute to these disparities.10 Also, in a study to understand perceived barriers to and preferences for general healthcare among black men, Ravenell et al.11 found that trauma survivors cited cultural differences, as well as a lack of awareness of medical concerns, as barriers to care. They also noted fear of serious conditions and fatalism (“I’m not going to make it anyway”) as reasons to avoid medical care.

We performed a qualitative study using Grounded Theory methods to understand the experiences of survivors of gun shot and stab wounds, to gain insight for planning interventions in hospitals that treat victims of community violence. The data from the following study describes the potential challenges to and promotive factors for, engaging black male victims of gun shot and stabbing injuries with medical and mental healthcare.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional study of an urban, community-based sample of black male victims of gunshot or stabbing injuries. Qualitative data were collected through semistructured interviews and analyzed using a Grounded Theory approach.12 This study obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board and a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health.

Selection of Participants

Participants were recruited via fliers posted in the community and through word of mouth. Eligibility criteria included a history of emergency medical treatment for a stabbing or shooting injury, aged 18 years to 38 years, male gender, and self-identified black race. Eligible participants provided written informed consent before an interview and received $25 compensation following the interview.

Procedures

Trained interviewers conducted 14 semistructured interviews (12 individual interviews and 2 interviews with 2 participants each) from January 2008 to December 2008. The interviewers were two community-based, black, male, mental health professionals (seven interviews), a white female research assistant (three interviews), a black male research assistant (three interviews), and the principal investigator (one interview). The digitally recorded interviews lasted 45 minutes to 120 minutes. The interview guide was developed to include open-ended questions about the injury, experiences with healthcare after the injury, encounters with primary care, and views on mental health treatment, substance use, and research. Interviewers also inquired about experiences with race and gender if not spontaneously mentioned by participants. Audio-recordings were professionally transcribed and all identifying information was removed to protect the participants. The research team reviewed the interviews and then updated the interview guide so that future participants could clarify concepts found in earlier interviews. Participants also filled out a survey including demographics, posttraumatic stress symptoms (Posttraumatic Checklist-Civilian),13–15 and alcohol use (AUDIT).16

Primary Data Analysis

The primary data analysis was conducted by an interdisciplinary and racially diverse research team consisting of two physicians (Emergency Medicine, Internal Medicine), two research assistants, a clinical psychologist, a mental health counselor, and two patient advocates working with victims of violence. Three members of the team were white and five were black. Additionally, one member of the team had a history of gun shot injury. The study used Grounded Theory12 to analyze semi-structured interviews. Transcripts were read and audio-recordings listened to multiple times by the research team to identify common words and phrases of similar meaning to classify and create concepts. Researchers developed a coding scheme through discussion of each concept identified and placed excerpts from the transcripts into the codes with the aid of N-VIVO version 7 software.17 At least two authors coded each transcript, and the research team discussion resolved coding discrepancies. The entire research team together grouped codes to create larger conceptual themes. For the final analysis, the research team generated theoretical constructs by examining these themes in the context of published literature from public health, medicine, social science, and psychology. The clinicians and advocates had extensive experience treating patients with stabbing and shooting injuries, which helped inform their interpretations of the themes. The findings were then placed into the context of published literature for the final analysis and presentation.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Subjects

Of the 16 participants enrolled in the study, the median age was 31 years (range, 25–38 years). Three were victims of gunshot, five of stab wounds, and eight of both injuries. The median length of time since the most recent injury was 5.5 years (range, 4 months–20.1 years). The median Posttraumatic Checklist-Civilian score was 43 (range, 22–69) and the median AUDIT score was 9 (range, 0–32).

Main Results

Researchers were struck by a lack of descriptions of interactions with healthcare clinicians, even when asked specifically about care after injury. For example, one participant described in exquisite detail all aspects of a stabbing assault. He summed up his medical treatment as, “let me see,… they took me to the emergency room. After that, for follow-up appointments…” This lack of detail in the narratives may indicate a sense of disconnection from the healthcare setting experienced by these men. Several themes, described in detail below, may elucidate the potential causes of this divide, and potential facilitators for future engagement with healthcare personnel. Table 1 provides illustrative quotations of the main themes.

TABLE 1.

Barriers to and Promotive Factors for Engaging Black Male Community Violence Victims With Health Care

| Theme | Subconcepts | Participant Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Physical and emotional disconnect | Not realizing that they had been injured | “I seen my cousin fall first, and I was askin’ him, ‘Are you a’right? And then I just noticed that he was bleedin, I was like, ‘Yo, you know you’re bleedin’?’ He was like, ‘No, I think that’s you.’ I checked myself, I didn’t see nothin,’ so I said, ‘No, it must be you,’ and it was … he got shot twice in his legs. I got up and I felt somethin’ warm on my side, and he was like, ‘Yo I think you (got) shot too,’ and I looked and I was, I was hit in the side.” |

| Confusion after waking up | “When I first woke up out the coma, I didn’t know what the f**k was goin’ on, I didn’t even know WHERE I was at. I woke up, like, ‘Damn!’ I’m lookin’ around … can’t even talk … and then I looked down at my stomach … ‘Oh, what the f**k???’ Now my heart’s racin,’ like, ‘Damn!’ I’m lookin’ at my insides,” and like, my f**kin’ stomach’s this wide … open!” | |

| Anger | “When I was in the hospital, there was nothin’ nobody could tell me, like, “Naw, like f**k this. Like, I’m through with it. Like, I’m gonna kill everybody … like, anybody who have problems with me, I was gonna deal with, or if anybody looked at me wrong, I was gonna have … I was gonna do somethin’ to.” | |

| Institutional mistrust | Police | “Well, the cops, as usual, were a**holes. Like it was our fault we got shot. First question they asked is, “Do you know who did it?” And then, “What did you do to the person that did it to you? Whose your enemies?” … they was actin’ like you just don’t get shot, it couldn’t be an accident, that we was walkin’ to the block and they got the wrong person; or they were lookin’ for somebody else. And that was the case! The dude who shot us, it had nuttin’ to do with us.” |

| Suspicion of clinician motives | “But they were happy to have people of color to patch up and profit off of. So, I guess they were grateful for that way. But, other than that, I was treated indifferently, especially by the nurses and the, um, after-care portion, the few days I spent in the hospital, I might as well have been a piece of meat.” | |

| Foreshortened future | Expect to die young | “When I was growin’ up, lot of cats and neighborhood people used to say most kids wasn’t gonna make it to see twenty-one.” |

| Self-reliance | Mental health | “And, especially from the ‘hood, if that’s what you want to call the inner city, they think that the counselors don’t care. They don’t care about what’s really goin’ on in my life, or how I feel … Like, they’re gettin’ paid to sit here and play with my life like a yo-yo, and then people feel like, ‘Oh, they don’t care.’” |

| Substance abuse | “Well, I cope with [PTSD symptoms] … through the grace of god, beer, and weed … (laughs). Well, that’s not the right solution, but I told you, I ain’t had no help, no counselin’ or nothin’ like that.” | |

| Preferred clinician characteristics | Race | “Like I said, I never had no problems with the doctors. It was just like they was … they was basically there for me It was just like … to me, it was a surprise, and like, different people, like … different colors, different race, you come through, they really don’t care about you, but … these people showed me they’re sorta like, ‘We save everybody’s life. Just not our own.’” |

| Shared experience | “They need someone to relate. Again, they don’t need to be an ex-drug addict; they don’t need to be straight from the penitentiary; they don’t need to be ANY of those things. Just be able to relate.” | |

| Wake-up call | Motivation for change | “If this didn’t happen and, the way that I dealt with myself after it happened, if I didn’t take that time to really put in work and to get myself to the point I am now, then I probably would have been in the streets with a gun right now, doing something ridiculous.” |

| Positive person | Social support | “To have a positive person in your life can make a world of difference in it supports your belief in yourself and what you stand for, what you’re tryin’ to achieve. It’s that affirmation that you can go on, despite tragedy and trauma. Now it’s like your spirit is bein’ ministered to. And, with anything that you do in life, you have to surround yourself with people who believe in you.” |

Barriers to Care

Disconnect

Perceptions of the injury may be the source of a lack of participation and cooperation with clinicians. Eight participants reported not realizing they were injured in the moment of trauma or the extent of the injury. The language to describe the injury may also typify this disconnect: “scratch” (a liver laceration and a gunshot wound to the arm) and “poked” (multiple stabbings in abdomen).

Participants may not necessarily perceive the life-threatening aspect of injuries in the immediate aftermath. Their experience of the injury and the foreign environment of the hospital may lead to the development of a different injury awareness, which when considering the severity of the clinical observations, may cause both patients and clinicians to misinterpret each other. As described by one participant, “I know it’s a real serious injury, but I saw I was alive, and, … I didn’t think it was a big deal at that time, ‘cause I’m like, “I’m alive!” … And y’all over here, actin’ like… it was real serious.”

A range of emotions flooded participants once they realized what occurred. All participants described an overwhelming sense of anger in the immediate aftermath of the injury. For many, thoughts of anger, and possible retaliation, were all consuming, “But, when you first get stabbed, your mind goes blank. You don’t think about anything but just revenge.” One consequence of the anger was a desire to leave the hospital against medical advice to deal with their feelings. “[I was in the hospital] only three days, ‘cause I was so mad that I wanted to leave.” Furthermore, waking up from emergent surgery or lost consciousness, experienced by eight participants, contributed to the heightened emotional state by creating confusion and surprise.

Institutional Mistrust

The context of “street culture” infused the injury and healthcare narratives of all participants to varying degrees. In particular, suspicion of dominant-culture institutions, such as police and healthcare, was common. The mistrust was exemplified by interactions with the police while receiving medical care for the injury. The participants saw that healthcare personnel (e.g., ambulance, emergency department, or inpatient setting) would allow the police to question them while getting treatment. The police interrogation during medical treatment made some feel as if they were being treated as the perpetrator, and increased their sense of vulnerability. According to one participant, “…the only visitors I had was the police, comin’ and talk to me… I felt like somebody was tryin’ to murder ME, and I’m in jail, havin’ all these cops comin’ to see me and talk to me like (I’m the suspect in) a murder investigation.”

Because this line between police and healthcare institution was blurred, in at least one case, it led to minimization of symptoms so that the healthcare personnel would not report this to the police. This participant discussed his presentation for treatment for a gun shot, “I just cut it short ‘cause I wasn’t too comfortable at tellin’ ‘em how I felt because if I tell ‘em too much… next thing you know, the police is comin,’ knockin’ at my door.”

Some of the institutional mistrust was based on a perception that healthcare clinicians are more motivated by money than by performing appropriate care, “… all the doctors and nurses and people in the healthcare field, when they first started out, they had genuine intentions. But, as years go on, big business corrupt their mind.”

One manifestation of this mistrust was an unwillingness to give out accurate contact information to healthcare personnel. One participant explained this as, “the G-code,” meaning gangster-code, a behavior in which the patient will be polite but not actually engage in the care, e.g. not give phone number, not attend follow-up appointments.

Foreshortened Future

Some participants reported that they had expected they would die at an early age. These feelings were reinforced by peers who were injured or died, and messages from adults, “A lot of my friends, they died when they were 15, 18 and, our teachers used to (say), “You guys, ya’ll aint never gonna make it past 18 years old.”

The injury reinforced expectations that getting shot or stabbed was inevitable. One participant said, “I left the hospital feeling like what happened to me is not a tragedy. It’s just a way of life.’”

Participants heavily involved in street culture reported embracing this fate, “We had a gung-ho attitude about it. It’s guns, violence, drugs… Today might be my day, so live it to the fullest.” This apparent attitude suggests that clinicians appealing to self-preservation instincts in patients as motivation for treatment might not be successful.

Self-Reliance

Participants expected that individuals and families rely on themselves for help. “As a young Black male… I’m not one to go to somebody and say, … ‘I need some help, I need to talk.” I rather… try to find out what to do, on my own. Get rid of my own stress.” In particular, discussions of treatment for mental health issues were peppered with the language of stigma; one compared mental health treatment to putting a pacifier in a baby’s mouth.

Others felt that mental health treatment is ineffective, partly because the therapist does not know the patient. One participant noted, “…spillin’ your beans about everything personal to somebody who barely even knows you, and is giving you feedback and telling you what to do about YOUR situations…just ‘cause it’s their job.”

Participants discussed forms of self-treatment, such as heavy use of substances, particularly alcohol and marijuana. “At times I cried, and then I started… breakin’ up with my family, started usin’ more drugs from alcohol to messin’ with cocaine, with weed, then from there to messin’ with heroin… to self-medicate myself. I figured if I self-medicate myself, I won’t be in that mind.”

Although 15 participants reported hazardous alcohol use or regular marijuana use, many reported that if they had a problem, they could stop on their own “My addiction is not so uncontrollable… I think my addiction is not worse than… quote/unquote ’hard core addicts’… I’m pretty much in control most of the time, when I make these bad decisions.” While some participants did report mental health symptoms and a perceived need for treatment, few reported actively seeking or having received therapy. Some reported that they would have liked (or even now would like) therapy, but did not know how to obtain such help.

Logistical Issues

Several logistical barriers to obtaining medical and mental healthcare were noted. Participants discussed a lack of safety they felt after the injury, “I continued to work, but then I was always in the house, so it was like, I was hidin,’ like I was a criminal…. And that’s why, eventually, I just saved my money and moved on outside of the city.”

Fear of public venues, such as public transportation, was common. This was particularly intense for those with newly acquired disabilities, including post-traumatic stress symptoms. “They wanted me to come to court and testify against him, … but, …after somethin’ like this happen, there’s no way you expect me just to get on the regular public transportation and come on down to the courthouse… That was like a death trap right there.” Money struggles were common in the participants, including difficulty obtaining safe and affordable housing, and lack of employment.

Facilitators to Care

Desired Clinician Characteristics

All participants were specifically asked about racial and gender preferences for treating physicians and mental health professionals. None of the participants reported a need for the treating physician to be black. “If you’re white, black, green, yellow, orange, as long as you’re professional and you know how to do your job… It doesn’t matter about race. I didn’t have no black people on my team. A straight cracker saved my life.” Medical competence, professionalism, and an “open-minded personality” that conveyed respect were cited as desirable characteristics of a clinician.

However, three did report wanting a mental health clinician to be black. One participant declared, “…she or he would definitely have to be the same color, hopefully, or nationality… I’d definitely feel more comfortable with somebody in my, [background].” Five said they preferred clinicians to be one gender over another, with mixed opinions about which gender. Despite only a few requesting a black clinician, another eight participants wanted a mental health clinician who could relate to their experiences in the street, “It’d be nice to have someone who has experience, … like, they can say, ‘Oh, I’ve been there,’ or, ‘I know someone who has been there.’”

Turning Point

Participants did report experiences and factors which promoted positive engagement with healthcare clinicians and motivated positive life changes. Despite feelings of a foreshortened future described by many participants, a number spoke about experiences which caused them to re-examine their lives. For some, the injury itself was a turning point in their life. It gave them time to think about past and future, and to see how their own actions might place them at risk. As one explains, “I was thinkin’ about my future. I’m thinkin’ about not doing the things that I had done in the past–sellin’ drugs, doing drugs, goin’ to jail, doing stupid stuff in the streets… God was tellin’ me this was somethin’ that may happen. It was a wake up call for me.” More commonly the birth of a child or recognition of their importance to their children inspired personal change, “when (the baby) is yours and you’re sittin’ there, you’re like, “Um, naw… I can’t do this [street life] no more. I can’t live like that.”

Positive People

A number of participants used the phrase “positive person” to describe people who helped them with their mental recovery from the trauma (or other issues). These positive people included friends, neighbors, family members, bosses, religious communities, and a barber. Positive people focused on moving in a future direction, rather than dwelling in the past. It included people who spoke honestly and respectfully with the participant about their problems. According to one, “They need to be around a positive person, like a friend, and let them know like, ‘Look, you need help, you need to, see somebody.’”

DISCUSSION

Among a group of black male victims of violence, the social environment strongly influenced engagement with medical and mental healthcare after an injury. These men perceived the importance of the medical treatment for their trauma. However, it did neither appear to integrate their reactions to the injury nor did it fully address the daily challenges they faced including mental health symptoms, disability, and safety concerns after the injury. Additionally, an underlying suspicion of institutions may interfere with taking advantage of potential resources of care. Beliefs about treatment for mental health and substance abuse may also have prevented them from accessing professional help. Engaging participants with supportive and forward social networks may best facilitate recovery.

The first sign of disengagement to healthcare may start at the moment of injury, with peritraumatic dissociation, a mental disconnect from the injury documented in studies of other violent injuries.18,19 Just after the injury, thoughts centered on anger at the perpetrator and the circumstances of the injury. These two phenomena, and the foreign environment of the healthcare setting, may contribute to the patient being physically present but mentally and emotionally disconnected from the medical and surgical care. The narratives suggest that this chasm between the patient experience and medical care delivery has the potential to result in poorly planned discharges and preventable readmissions. While some factors may be beyond the control of medical personnel, knowledge of potential patient concerns, and challenges can facilitate development of potential responses.

While mistrust of healthcare institutions among black populations has been documented previously,20–22 it has unique implications for victims of stabbing and shooting. Within inner-city black communities, suspicion of mainstream institutions may be explained in part by what sociologist Elijah Anderson calls, “The Code of the Street.”23 According to Anderson, this Code is a set of rules in response to the perceived failure of mainstream institutions to serve the needs of inner-city communities. The Code encourages an attitude of self-reliance, such as self-defense through neighborhood or gang affiliations, and aversion to asking for help, an attitude that may follow these youth into a healthcare setting. Cooperating with police may be interpreted as defying the Code and be a risk for further injury. Venkatesh,24 in his book Gang Leader for a Day, substantiates the theme that poor black urban populations experience mainstream institutions as not serving their needs. Patients may view medical institutions as an extension of the legal system. For example, routine interviewing of patients by police detectives occurs during receipt of emergent treatment in both ambulances as well as Emergency Departments (EDs). Given this experience, patients may not view the postinjury care experience as a secure and trusting environment, rather- it has potential for worsening safety after discharge.

Emergency medical services should consider instituting policies about asking patient permission before allowing police to question patients. While this may not be possible before entering hospital EDs, instituting such policies could be considered in hospital EDs, in the same way that patients may refuse other visitors. In addition, medical personnel should clearly delineate what patient information is available to police (or others) and what is confidential.

Physical disabilities stemming from the injury increase the vulnerability already engendered by injury itself and subsequent encounters with police. This may lead to a decreased sense of safety, particularly heightened in venues such as public transportation. The fear of public transportation may be a major obstacle for these men to obtain postinjury care and to take advantage of available resources. Providing patients with private and safe transportation may help to improve follow-up care.

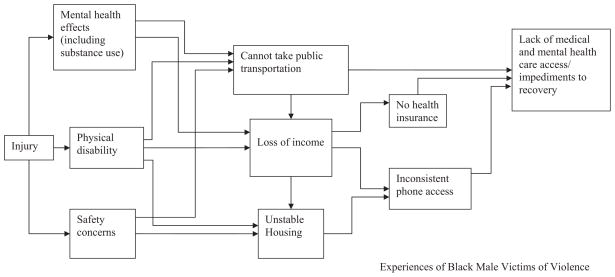

Appropriate and safe housing is also a challenge for a number of these men. Prior housing arrangements may not be appropriate due to physical limitations (e.g. not wheelchair accessible). They also may not feel safe from either gang-related retaliation (to keep victim from disclosing to police), high family tensions, difficulty paying rent due to loss of income, or posttraumatic stress symptoms from fear of injury in the same neighborhood. These survival issues compete with medical needs, especially in a group of young men who hold self-reliance as a core value. Future programs on preventing further postinjury morbidity should consider providing supported and safe housing to allow the participant to recover. Figure 1 depicts a theoretical model of how logistical barriers stemming from injury may affect access to healthcare.

Figure 1.

Postinjury barriers to medical and mental healthcare for black male victims of community violence.

The easy availability of substances, particularly alcohol and marijuana, provided an escape from the emotional toll of stabbing and shooting for some study participants. As noted by Rich and Grey,25 substance use is one link on the pathway to re-injury. Getting professional help for substance use or mental health symptoms would entail overcoming a variety of barriers for black male violence victims. The nature of treatment involves asking for help, acknowledging weakness and trusting of mainstream institutions, which contradicts a core value of self-reliance. Inaccurate information about effectiveness of treatment contributes to these barriers. Contradictorily, most study participants desired relief from mental suffering but did not know how to access such help, suggesting that a public health campaign about substance abuse and mental health treatment, along with expanded access, may decrease some barriers.

The power of the social network suggests another route that medical clinicians might draw on: working (with patient permission) on engaging a circle of positive people in the recovery plan. This may help encourage patients to engage in self-care and use the available treatments.

Limitations

Qualitative studies, by design, are meant to generate ideas and not provide conclusions generalized to other populations. A common drawback of qualitative research is related to bias, including bias of the interviewers who may have unknowingly influenced participant responses and bias of the researchers analyzing the data. To counter those biases, interviewers were extensively trained. As well, a large diverse, interdisciplinary team performed the analyses and formulated the conclusions with participation from all team members. It is not known whether this sample differed greatly from those unwilling to participate in research projects. Additionally, the participants’ memories may have evolved since the actual events took place, and thus, the reporting may not reflect actual experiences. While interviews were scheduled with black male interviewers, participants who arrived at unscheduled times and did not have adequate phone access to reschedule were interviewed by available trained personnel. It is not clear how this affected study results.

CONCLUSIONS

Effective emergency care for black male victims of stabbing and shooting should go beyond stopping the acute bleeding, and encompass methods to build bridges to patients’ needs. This would include delineating clear boundaries between patient rights and law enforcement needs, and then assessing for safety, transportation, and housing issues after discharge. Campaigns to educate and decrease stigma of mental and substance abuse care combined with facilitated access to such treatment may also improve outcomes.

References

- 1.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Leading Causes of Death Reports. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox J, Swatt M. The Recent Surge in Homicides involving Young Black Males and Guns: Time to Reinvest in Prevention and Crime Control. Boston, MA: Northeastern University; 2008. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holbrook TL, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza B, Sise M, Anderson JP. Long-term posttraumatic stress disorder persists after major trauma in adolescents: new data on risk factors and functional outcome. J Trauma. 2005;58:764–769. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000159247.48547.7d. discussion 769–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adesanya AA, da Rocha-Afodu JT, Ekanem EE, Afolabi IR. Factors affecting mortality and morbidity in patients with abdominal gunshot wounds. Injury. 2000;31:397–404. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(99)00247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker MG, Hall JS, Ursic CM, Jain S, Calhoun D. Caught in the Crossfire: the effects of a peer-based intervention program for violently injured youth. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper C, Eslinger DM, Stolley PD. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. J Trauma-Injury Infect Crit Care. 2006;61:534–537. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000236576.81860.8c. discussion 537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zun LS, Downey L, Rosen J. The effectiveness of an ED-based violence prevention program. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shibru D, Zahnd E, Becker M, Bekaert N, Calhoun D, Victorino GP. Benefits of a hospital-based peer intervention program for violently injured youth. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:684–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zun LS, Downey LV, Rosen J. Violence prevention in the ED: linkage of the ED to a social service agency. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:454–457. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravenell JE, Whitaker EE, Johnson WE., Jr According to him: barriers to healthcare among African-American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1153–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications; 1990. p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman JA, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity and diagnostic utility. Annual Conference of the ISTSS; San Antonio, TX. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Huska JA, Keane TM. PCL-C for DSM. IV. Boston, MA: N.C.F.P.B.S. Division; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NVIVO version7. Victoria, Australia: QSR International; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fein JA, Kassam-Adams N, Vu T, Datner EM. Emergency department evaluation of acute stress disorder symptoms in violently injured youths. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:391–396. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.118225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall GN, Schell TL. Reappraising the link between peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD symptom severity: evidence from a longitudinal study of community violence survivors. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:626–636. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong K, McMurphy S, Dean LT, et al. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:827–833. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halbert CH, Armstrong K, Gandy OH, Jr, Shaker L. Racial differences in trust in health care providers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:896–901. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson E. The code of the streets. Atlantic Monthly. 1994;273:81–94. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkatesh S. Gang Leader for a Day. London, England: Penguin Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rich JA, Grey CM. Pathways to recurrent trauma among young black men: traumatic stress, substance use, and the “code of the street”. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:816–824. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]