Abstract

The orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 is an immediate-early response gene whose expression is rapidly induced by various extracellular stimuli. The aims of this study were to study the role of Nur77 expression in the growth and survival of colon cancer cells and the mechanism by which Nur77 expression was regulated. We showed that levels of Nur77 were elevated in a majority of human colon tumors (9/12) compared to their nontumorous tissues and that Nur77 expression could be strongly induced by different colonic carcinogens including deoxycholic acid (DCA). DCA-induced Nur77 expression resulted in up-regulation of antiapoptotic BRE and angiogenic VEGF, and it enhanced the growth, colony formation, and migration of colon cancer cells. In studying the mechanism by which Nur77 was regulated in colon cancer cells, we found that β-catenin was involved in induction of Nur77 expression through its activation of the transcriptional activity of AP-1 (c-Fos/c-Jun) that bound to and transactivated the Nur77 promoter. Together, our results demonstrate that Nur77 acts to promote the growth and survival of colon cancer cells and serves as an important mediator of the Wnt/β-catenin and AP-1 signaling pathways.—Wu, H., Lin, Y., Li, W., Sun, Z., Gao, W., Zhang, H., Xie, L., Jiang, F., Qin, B., Yan, T., Chen, L., Zhao, Y., Cao, X., Wu, Y., Lin, B., Zhou, H., Wong, A.S.-T., Zhang, X.-K., Zeng, J.-Z. Regulation of Nur77 expression by β-catenin and its mitogenic effect in colon cancer cells.

Keywords: AP-1, PI3K, JNK, bile acid

Nur77 (also known as TR3 and NGFI-B) is an orphan member of the nuclear receptor superfamily and an immediate-early response gene (1–4). Like other nuclear receptors, Nur77 can function as a transcriptional factor that binds to its DNA response elements either as monomer, homodimer, or heterodimer (5, 6). Nur77 was originally recognized for its proactive role in cell proliferation and differentiation (4, 7). It is often overexpressed in a variety of malignant tissues (8–10), and its expression can be rapidly induced by a number of growth factors and mitogens in cancer cells (11, 12), suggesting that Nur77 acts to support the growth and survival of cancer cells. Consistently, ectopic expression of Nur77 stimulates cell cycle progression and proliferation in lung cancer cells (11), whereas suppression of Nur77 expression inhibits the transformation phenotype of several cancer cell lines of different origins by promoting their apoptosis (13). Paradoxically, Nur77 also exerts a death effect, perhaps being the most potent proapoptotic member in the nuclear receptor superfamily (2, 3, 14). Nur77 expression is rapidly induced during apoptosis of immature thymocytes and T-cell hybridomas (15, 16). It is also a key mediator of apoptosis of cancer cells induced by chemotherapeutic agents (8, 14, 17–20). Translocation of Nur77 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and its subsequent interaction with Bcl-2 and association with mitochondria have been shown to account for the apoptotic effect of Nur77 in response to a variety of apoptotic stimuli and in several different cell types (14, 15, 21). Nur77 is overexpressed in colon cancer cells (8, 20), and its expression levels are often elevated in human colon tumors as compared with the corresponding nontumorous tissues (8). Induction of Nur77 nuclear export by butyrate resulted in extensive apoptosis of colon cancer cells (20). However, butyrate-induced cytoplasmic Nur77 did not target mitochondria (20), suggesting that mitochondrial targeting of Nur77 was unlikely responsible for butyrate-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Thus, it is possible that nuclear Nur77 serves as a critical survival factor of colon cancer cells and that alteration of its subcellular localization inhibits its survival function, leading to cell death. Consistently, treatment of colon cancer cells with Nur77-active compounds C-DIMs that altered Nur77 transcriptional activity induced apoptosis of colon cancer cells (8). However, direct evidence supporting a survival function of Nur77 in colon cancer cells is lacking, and how Nur77 expression is induced during colon carcinogenesis remains unknown.

Colon cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide, which is largely associated with high-fat diet and causatively linked to the increased production of colonic bile acids (22–24). Deoxycholic acid (DCA), a cytotoxic secondary bile acid, is believed to be a major risk factor for colon cancer. DCA can potently promote the formation of chemically induced colonic aberrant crypt foci and is involved in the malignant transformation of adenoma into carcinoma (25–27). At the molecular level, the most notable alteration in colon cancer is the increased nuclear activity of β-catenin (23, 28, 29). β-Catenin is a key mediator of Wnt signaling (30, 31) and a converging point of multiple signal transduction pathways implicated in tumorigenesis, including the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (32, 33). β-Catenin is predominantly localized at cell membranes, and its cytoplasmic level is tightly controlled by 2 APC-dependent proteasomal degradation pathways (28, 30, 34). Elevation of a free, signaling pool of endogenous β-catenin can result in its nuclear translocation, where it acts as a coactivator of numerous transcription factors to modulate cell cycle and proliferation (28–30). β-Catenin is abnormally activated in most of human colon cancer as a result of frequent mutations in its regulatory tumor suppressor APC gene or in β-catenin itself (29, 35). In addition to Wnt signaling stimulation, various colonic carcinogens including DCA, 1,2-dimethylhydrazine (DMH), and azoxymethane (AOM) are able to stabilize β-catenin and induce its nuclear translocation through different mechanisms (27, 33, 36, 37), suggesting that targeting β-catenin is a common event during colonic carcinogenesis.

In this study, we examined the role of Nur77 expression in colon cancer cells and the mechanism by which Nur77 expression was regulated by colonic carcinogens. Our results showed that Nur77 was overexpressed in human colon tumors and during colon carcinogenesis in animals. Overexpression of Nur77 promoted the growth and survival of colon cancer cells, which was associated with induction of antiapoptotic BRE (brain and reproductive organ-expressed protein) (18) and angiogenic VEGF expression (38). Interestingly, Nur77 up-regulation by DCA was due to its activation of PI3K/Akt and JNK pathways, leading to nuclear translocation of β-catenin and its interaction with c-Fos and c-Jun. Interaction of β-catenin with c-Fos and c-Jun resulted in formation of a complex that bound to AP-1 binding sites in the Nur77 promoter, leading to activation of Nur77 transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Lipofectamin 2000 and Trizol LS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA); enhanced chemilumienescence (ECL) reagents, goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Thermo, Rockford, IL, USA); fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-rabbit IgG and anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Cy3 (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA); polyclonal antibodies against Nur77 and p-Akt1/2 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), p-JNK1/2, c-Fos, c-Jun, and p-c-Jun (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); monoclonal antibodies against c-Myc (9E10), β-catenin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); PARP (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), β-actin, α-tubulin, and GAPDH (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA); chemicals LY294002, SP600125, DCA, DMH, and AOM (Sigma); protein-A beads (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA); PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA); and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (80–6501-23) (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) were used in this study.

siRNAs

For transient transfection, siRNA sequences against c-Jun 5′-CUGAUAAUCCAGUCCAGCA-3′, c-Fos 5′-GGUUCAUUAUUGGAAUUAA-3′, and β-catenin 5′-GGUGGUGGUUAAUAAGGCU-3′ (Ribobio Co., Guangzhou, China) (39, 40) were used. Nur77 siRNAs used in this study were a mixture of the following sequences: 5′-UCGAGGACUUCCAGGUGUA-3′, 5′-GGACAGAGCAGCUGCCCAA-3′, 5′-GAAGGCCGCUGUGCUGUGU-3′, and 5′-CGGCUACACAGGAGAGUUU-3′ (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA). To establish a stable HCT116/siNur77 cell line, HCT116 cells were transfected with hairpin expression construct pSuper.gfp/neo (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA, USA) containing Nur77 siRNA (5′-ACAGTCCAGCCATGCTCCT-3′) cloned at XhoI/BglII sites, and stable lines were selected with 1 mg/ml G418 (Sigma).

Tissue samples

Tumor and the surrounding tissues of human colon cancer were collected immediately after surgical resection. The study was approved by the Xiamen University Institute for Biomedical Research Ethics Committee, and all patients gave their informed consent.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse colon tissue and human colon tumor tissue sections were immunostained with anti-Nur77 (1:100), anti-β-catenin (1:100), or anti-PCNA (1:200) antibodies. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. For fluorescent confocal microscopy, SW480 cells were immunostained with anti-Nur77 (1:100) and anti-β-catenin (1:100) antibodies and detected by anti-Cy3 and anti-FITC antibodies, respectively. Cells were also costained with 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize nuclei.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNAs were purified by Trizol LS. First-strand cDNA was generated with RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kits (Fermentas, Burlington, ON, Canada). PCR reactions were carried out to amplify Nur77, BRE, and VEGF, while amplification of β-actin was served as a control. Primers used for Nur77 and β-actin were those described previously (14). Primers used for BRE were the following: forward, 5′-ATCTTGCCTCCTGGAATCCT-3′, and reverse, 5′-ACGTACTGCACCTTGTTGG-3′; and for VEGF, forward, 5′-AGGAGGGCAGAATCATCACG-3′, and reverse, 5′-CAAGGCCCACAGGGATTTTCT-3′.

MTT assays

SW620 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with increasing concentrations of DCA for 72 h. Cells were stained with 0.05 mg/ml 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) and measured at 570 nm with an automated microplate reader (Thermo).

In vitro cell wound-healing assays

Cells were cultured on glass coverslips in 24-well plates. The confluent monolayers were wounded in a line across the slides with a sterile 20-μl plastic pipette tip and incubated in serum-free medium containing 10 μM DCA or vehicle for 12 h. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with DAPI. Cell migration, indicating wound healing effect, was evaluated by comparing the remaining cell-free area with that of the initial wound.

Colony formation assays

Cells were cultured in 6-well plates with or without DCA (10 μM) for 14 days and then subjected to Giemsa staining. Number of foci containing >50 cells was scored.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cells treated with vehicle or DCA in serum-free medium for 24 h were collected and stained with Annexin V/propidium iodide using Vybrant Apoptosis Assay Kit no. 2 and analyzed by flow cytometry (Epics Altra; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Animal studies

Male Kunming mice (18–22 g, aged 4–6 wk) were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China. The animals were treated with DCA (20 mg/kg, intrarectal instillation, n=6/group) or vehicle for 1 wk, or treated with DMH (25 mg/kg, weekly intraperitoneal injection) alone or in combination with DCA (2.0 g/L in drinking water) for 6 wk (n=6/group). The mice were sacrificed after treatment, and colon and small intestine tissues were removed for further analysis.

Immunoprecipitations

Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 2 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, and 1% IGEPAL. Whole cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies against β-catenin, c-Fos, or c-Jun in protein-A beads.

Western blotting

Protein extracts were fractionated on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Protein expression was detected by primary and secondary antibodies and visualized with the ECL system. Subcellular fractionation assays were conducted as described (14).

Nur77 promoter constructs and luciferase assays

Human genomic DNA was isolated from HEK293T cells using a Qiagen DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The promoter fragments of Nur77 were generated by PCR and cloned into EcoR I and XhoI sites of pGL3-basic luciferase reporter. Individual and simultaneous mutations of AP-1 sites in the Nur77 promoter were generated using the Quick Change site-mutagenesis kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan). Expression of luciferase reporter genes containing the Nur77 promoter and pAP-1 promoter was determined in SW480 cells. Each transfection also included β-galactosidase for normalization of the luciferase activities.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

SW480 cells were treated with or without 10 μM DCA for 2 h and then processed with a Chip Assay Kit protocol (Millipore). Briefly, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and quenched with 125 μM glycine. Cross-linked chromatin was sonicated to an average length of ∼500 bp and subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies against β-catenin, c-Fos, c-Jun, or TCF4 or with nonimmune IgG as controls. The chromatin-antibody complexes were precipitated with protein-A beads and digested with proteinase K to remove proteins. The purified DNA was subjected to PCR amplification using primers flanking the AP-1 site or the distal sequence as control in the Nur77 promoter as indicated.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± sd from ≥3 experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test. Differences were considered statistically significant with P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Nur77 is overexpressed in human colon tumors and is strongly induced in mice colonic epithelium by colonic carcinogens

To determine the role of Nur77 in colon cancer cells, we first examined the expression levels of Nur77 in surgical specimens prepared from 12 patients with colon cancer by immunoblotting. Among them, 9 patients showed higher levels of Nur77 in their tumor tissues than their corresponding nontumorous tissues (Fig. 1A), demonstrating that Nur77 is overexpressed in a majority of colon cancer, consistent with a recent report (8).

Figure 1.

Nur77 expression in human colon tumors and mouse colon tissues exposed to colonic carcinogens. A) Enhanced expression of Nur77 in colon tumor tissues. Lysates prepared from tumor tissues (T) and the surrounding colon tissues (S) of patients with colon cancer were analyzed for Nur77 expression by immunoblotting. B) Induction of Nur77 expression during colonic carcinogenesis. Colon and small intestine tissues prepared from mice coexposed to DCA (2.0 g/L in drinking water) and DMH (25 mg/kg, i.p. weekly) for 6 wk were analyzed for Nur77 expression by immunoblotting. C) Colon tissue sections prepared from mice received intrarectal instillation of DCA (20 mg/kg) or water (control) daily for 1 wk were immuostained with antibodies against Nur77 and PCNA.

DMH is a specific colonic carcinogen, which is widely used alone or in combination with DCA to induce colon cancer in animals (27, 36). We next investigated the effect of these agents on inducing Nur77 expression in animals. Figure 1B shows that treatment of mice with DMH for 6 wk resulted in strong induction of Nur77 expression in various segments of the colon, which could be further enhanced when mice were coadministered with DCA. In contrast, DMH combination with DCA was much less effective on inducing Nur77 expression in the small intestine. Treatment of mice with DCA alone through intrarectal instillation for 1 wk also resulted in significant increase in Nur77 expression in colonic epithelium, as indicated by strong nuclear immunostaining of Nur77 in ∼40% of colonic epithelial population (Fig. 1C). Together, these results demonstrate that Nur77 is induced during colonic carcinogenesis.

Survival and proliferative actions of Nur77

When treated with DCA, we noticed that DCA induction of Nur77 expression in colonic epithelial cells was accompanied with enhanced PCNA expression (Fig. 1C), suggesting that Nur77 might play a role in cellular proliferation. To further determine the role of Nur77 in the regulation of the growth and survival of colon cancer cells, we examined the expression of Nur77 in SW620 colon cancer cells in the absence or presence of DCA. Consistent with our observation in mice colonic epithelium, our immunoblotting assays showed that DCA strongly induced Nur77 expression in SW620 colon cancer cells in dose- and time-dependent manners (Fig. 2A, B). Nur77 protein level was increased by ∼2.1-fold when SW620 cells were treated with 10 μM DCA for 5 h (Fig. 2A). Further increase of Nur77 expression up to 3.7-fold was seen when 50 μM DCA was used. In the time course study, a significant induction of Nur77 (∼2.3-fold) was observed when cells were treated with 10 μM DCA for as short as 3 h, which peaked (∼4.4-fold) at 9 h and returned to baseline at 12 h (Fig. 2B). We noticed that DCA-treated SW620 cells reached confluence when cultured for 24 h, whereas the vehicle control cells seeded at the same density needed more than 30 h to grow to confluence. Interestingly, Nur77 expression was diminished in the confluent cells when treated with DCA for 24 h or longer (Fig. 2B). The correlation of high levels of Nur77 with rapid growth rates of colon cancer cells in response to DCA treatment suggested that Nur77 expression might play an active role in promoting cell growth. Indeed, our MTT assay showed that DCA induction of Nur77 expression was associated with its growth-stimulatory effect within the concentration range of 5∼50 μM (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, DCA-induced Nur77 expression was correlated with increased expression of BRE mRNA (Fig. 2D), an antiapoptotic protein recently identified as a direct target gene of Nur77 (18), and VEGF (Fig. 2F), a potent angiogenic factor that promotes cancer cell growth (38). The expression of both BRE and VEGF genes in response to DCA treatment was abrogated by siRNA-mediated knocking down of Nur77 expression, demonstrating that DCA induction of BRE and VEGF was dependent on Nur77 expression (Fig. 2E, F). The dose-dependent induction of Nur77, BRE, and VEGF by DCA was closely correlated with its promotion of colon cancer cell growth (Fig. 2C). To further determine the effect of Nur77 on inducing colon cancer cell growth, we conducted colony formation assays. Similar to its effect in SW620 cells, DCA strongly induced Nur77 expression in HCT116 colon cancer cells (Fig. 2G). Treatment of HCT116 cells with DCA increased their ability to form colonies (Fig. 2H). When Nur77 expression was inhibited by siRNA (Fig. 2G), the basal and DCA-induced colony formation of HCT116 cells was greatly impaired (Fig. 2H). Interestingly, instead of stimulating cell growth, DCA treatment almost completely inhibited the colony formation of HCT116/siNur77 stable cells (Fig. 2H), suggesting that Nur77 expression was essential for the survival of cells in the presence of the cytotoxic DCA. To directly address the role of Nur77, we stably transfected Nur77 into SW480 cells and examined their ability to form foci. The colony foci number of SW480 cells stably expressing Nur77 was almost doubled as compared to the parental SW480 cells (Fig. 2I). To further address the survival effect of Nur77, we examined the apoptosis of HCT116 cells and HCT116 cells stably expressing Nur77 siRNA. Cells were treated with or without DCA, and apoptosis was measured by Annexin V staining. Flow cytometry analysis of Annexin V binding showed that inhibition of Nur77 expression by siRNA resulted in extensive apoptosis of the cells, which could be further enhanced by DCA treatment (Fig. 3A, B). The survival role of Nur77 was confirmed by comparing the effect of DCA on inducing colony formation of MEF cells and MEF Nur77−/− cells. Figure 3C shows that DCA treatment greatly increased the number and size of colonies produced by MEF cells, while it inhibited rather than promoted the colony formation of MEF Nur77−/− cells. We also examined the effect of DCA on migration of these cells by in vitro wound-healing assays. DCA treatment significantly enhanced the migration of MEF cells but not that of MEF Nur77−/− cells (Fig. 3D). Together, these results demonstrate that Nur77 expression is essential for the growth and survival of colon cancer cells and suggest that the tumor-promoting effect of DCA may involve its induction of Nur77.

Figure 2.

Growth-promoting effect of Nur77 in colon cancer cells. A) Nur77 expression in colon cancer cells. SW620 cells were treated with vehicle or with 10, 20, or 50 μM DCA for 5 h. B) Time course-dependent induction of Nur77 protein. SW620 cells were treated with vehicle or with 10 μM DCA for various intervals as indicated. Relative expression levels of Nur77 were normalized to those of β-actin. C) Induction of colon cancer cell growth by DCA. SW620 cells treated with vehicle or increasing concentrations of DCA for 48 h were analyzed by the MTT method. D) DCA induces BRE mRNA expression. SW620 cells were treated with DCA with the indicated concentrations for 6 h. E) Induction of BRE mRNA expression by DCA requires Nur77 expression. HCT116 and HCT116/siNur77 cells treated with 20 μM DCA for 6 h were subjected to RT-PCR analysis. F) DCA-induced VEGF mRNA expression was assayed by real-time PCR in HCT116 and HCT116/siNur77 cells. **P < 0.01 vs. basal level; ##P < 0.01 vs. corresponding control. G, H) Effect of Nur77 expression on colony formation of colon cancer cells. Nur77 expression in HCT116 cells and HCT116 cells transfected with Nur77 siRNA (HCT116/siNur77) was evaluated by Western blotting (G). Cells were grown in medium containing 10 μM DCA for 14 d, and the number of foci containing more than 50 cells was scored (H, left panel). Mean number of foci formed by parental HCT116 cells in the vehicle control was normalized to 100%; all other colonies were compared (H, right panel). I) Overexpression of Nur77 promotes colony formation. SW480 and SW480/GFP-Nur77 cells were used for colony formation assays as described above.

Figure 3.

DCA induction of Nur77 expression is essential for cell survival, migration, and colony formation. A) Suppression of Nur77 expression induces apoptosis. HCT116 and HCT116/siNur77 cells treated with vehicle or the indicated concentrations of DCA for 24 h were stained with PI/Annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry. B) Apoptotic cells with Annexin V+/PI− staining from 3 independent experiments were quantitated. C) Nur77 is required for DCA induction of colony formation. MEF and MEF Nur77−/− cells were cultured in the serum-containing medium with or without 10 μM DCA for 14 d (left panel). The mean number of foci formed by MEF cells without treatment was normalized to 100%, whereas the other colonies were compared (right panel). D) Nur77 is required for DCA induction of cell migration. MEF and MEF Nur77−/− cells were wounded by a 20-μl plastic pipette tip and cultured in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of 10 μM DCA for 12 h. Cells were stained with DAPI, and cell migration into the wounded area was evaluated.

DCA induces Nur77 expression through PI3K and JNK pathways

To determine the mechanism by which DCA induced Nur77 expression, we first examined the involvement of several signal pathways by using various kinase inhibitors. SW620 cells were preincubated with kinase inhibitor before treatment with 15 μM DCA for 3 h. Immunoblotting showed that induction of Nur77 expression by DCA was strongly inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and the JNK inhibitor SP600125, while pretreatment with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 and the MEK inhibitor PD98059 had little effect (Fig. 4A). The inhibitory effect of LY294002 and SP600125 was also illustrated by real-time PCR analysis (Fig. 4B). Together, these results demonstrate that both PI3K and JNK pathways play a role in the induction of Nur77 transcription by DCA.

Figure 4.

Activation of PI3K/Akt and JNK pathways is involved in Nur77 induction. A) Effect of kinase inhibitors on DCA induction of Nur77 expression. SW620 cells preincubated with 10 μM of the indicated kinase inhibitors before treatment with 15 μM DCA for 3 h were analyzed for Nur77 expression by immunoblotting. B) Effect of PI3K and JNK inhibitors on DCA induction of Nur77 mRNA expression. SW620 cells treated with 15 μM DCA in combination with 10 μM LY294002 or 10 μM SP600125 for 1 h were subjected to real-time PCR analysis. C) SW620 cells treated 15 μM DCA in the presence of either 10 μM PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or 10 μM JNK inhibitor SP600125 for 3 h were analyzed by immunoblotting. D) Inhibition of Akt activation impairs the effect of DCA on inducing Nur77 expression. SW480 cells were transfected with increasing amounts of dn-Akt expression vector and subjected to 15 μM DCA treatment for 3 h. Levels of phosphorylated Akt and Nur77 expression were determined by immunoblotting. E) Effect of dn-Akt on DCA induction of Nur77 expression in SW480 cells was analyzed by immunostaining analysis. F) Inhibition of c-Fos and c-Jun expression by siRNA impairs the effect of DCA on inducing Nur77 expression. Control and transfected SW480 cells were treated with 10 μM DCA for 3 h.

The role of PI3K pathway in the DCA up-regulation of Nur77 was further demonstrated by our observation that DCA induction of Nur77 expression was associated with Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 4C, lanes 2 vs. 1), which was inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Fig. 4C, lanes 4 vs. 3). Furthermore, transfection of SW480 cells with the dominant-negative Akt mutant dn-Akt largely impaired the ability of DCA to induce Nur77 expression (Fig. 4D, E). We also examined the involvement of JNK activation by DCA in its induction of Nur77. DCA activation of JNK was mainly due to its activation of JNK2, whereas the JNK1 activity was only slightly increased (Fig. 4C, lanes 2 vs. 1), which was accompanied by increased phosphorylation of c-Jun, a direct substrate of JNK (41). DCA also induced c-Fos expression, and the induction was abrogated by the JNK inhibitor SP600125, suggesting that c-Fos is another target of JNK (42). To determine whether c-Fos and c-Jun were involved in DCA up-regulation of Nur77, siRNA sequences against c-Jun and c-Fos genes were synthesized and evaluated. Our results showed that knocking down c-Jun and c-Fos expression by an siRNA approach profoundly inhibited the effect of DCA on inducing Nur77 expression (Fig. 4F). Thus, DCA activation of JNK and its induction of AP-1 (c-Fos/c-Jun) are involved in DCA induction of Nur77 expression.

β-Catenin induces Nur77 expression in colon cancer cells

β-Catenin is aberrantly activated in most colon tumors due to altered proteasome-dependent protein degradation pathways. Interestingly, our immunohistochemistry analysis showed that increased Nur77 expression in human colon tumor tissue was coincident with nuclear accumulation of β-catenin (Fig. 5A). We therefore determined whether β-catenin activation could contribute to Nur77 induction by studying the effect of several upstream activators of β-catenin on Nur77 expression. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared from SW480 cells treated with either DCA, AOM, a colonic carcinogen, or lithium chloride (LiCl), a known Wnt signaling agonist (28), and examined for Nur77 expression by immunoblotting (Fig. 5B). The purity of our subcellular fractions was confirmed by the presence of the nuclear protein PARP in the nuclear but not the cytoplasmic factions. Treatment of the cells with these agents resulted in enhanced accumulation of β-catenin in the nuclear fractions, which was accompanied with induction of Nur77 expression (Fig. 5B). It is noteworthy that Nur77 induced by these agents resided mainly in the nucleus, suggesting that the nuclear actions of Nur77 might account for its biological effects in colon cancer cells. DCA-induced β-catenin nuclear translocation and Nur77 expression were further illustrated by our immunostaining assays showing that Nur77 was predominantly increased in cells displaying strong nuclear immunostaining of β-catenin (Fig. 5C). When cells were preincubated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, the effects of DCA on inducing β-catenin nuclear translocation and Nur77 expression were significantly inhibited. Thus, DCA activation of β-catenin might be due to its activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. To further study the role of β-catenin, we examined the effect of β-catenin/S33Y, a degradation-resistant constitutively active mutant, on Nur77 expression. Transfection of HEK293T cells with β-catenin/S33Y resulted in strong induction of Nur77 expression as revealed by immunoblotting (Fig. 5D). Conversely, DCA-induced Nur77 expression was remarkably inhibited in SW480 cells transfected with β-catenin siRNA (Fig. 5E). Together, these results demonstrate that β-catenin activation plays an important role in the induction of Nur77 expression in colon cancer cells.

Figure 5.

Association of nuclear β-catenin with Nur77 induction. A) Immunostaining of colon tumor tissues (T) and the surrounding tissues (S) with antibodies against β-catenin and Nur77. B) Nuclear accumulation of β-catenin is associated with Nur77 induction. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions prepared from SW480 cells treated with 10 μM DCA, 2 mM AOM, or 10 mM LiCl for 3 h were analyzed for expression of β-catenin and Nur77 by immunoblotting. N, nuclear fraction; C, cytoplasmic fraction. PARP expression was included to confirm the purity of the nuclear fraction. C) Activation of β-catenin induces Nur77 expression. SW480 cells treated with 10 μM DCA in the presence or absence of 10 μM PI3K inhibitor LY294002 for 3 h were coimmunostained with Nur77 (red) and β-catenin (green) antibodies. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nuclei. D) Nur77 up-regulation by β-catenin/S33Y. SW480 cells transfected with empty vector or with 1 or 2 μg of β-catenin/S33Y expressing vector for 30 h were analyzed by immunoblotting. E) Inhibition of β-catenin expression impaired DCA-induced Nur77 expression. SW480 and SW480/siβ stable cells treated with 10 μM DCA for 5 h were analyzed by immunoblotting.

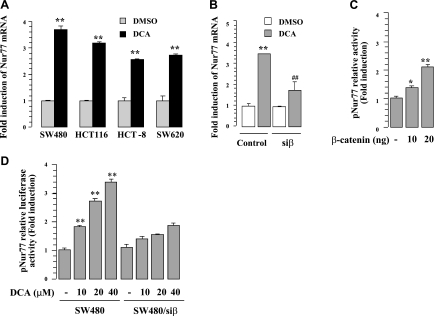

Induction of Nur77 expression by β-catenin occurs at transcriptional level

To determine the mechanism by which β-catenin induced Nur77 expression, we first address whether β-catenin induced Nur77 gene transcription by conducting real-time PCR and Nur77 promoter reporter assays. Real-time PCR analysis showed that DCA treatment strongly induced Nur77 mRNA expression, which occurred as early as 1 h in several colon cancer cell lines, including SW620, SW480, HCT-116, and HCT-8 cells (Fig. 6A). The induction of Nur77 mRNA by DCA in HCT116 cells was impaired by β-catenin siRNA (Fig. 6B), suggesting that β-catenin could regulate Nur77 gene transcription. Consistently, we observed that transcription of the Nur77 promoter (pNur77, containing ∼2.0 kb upstream of the ATG site) could be dose-dependently activated by β-catenin and DCA (Fig. 6C, D). In contrast, inhibition of β-catenin expression by siRNA transfection suppressed the effect of DCA on inducing pNur77 promoter activity (Fig. 6D). Thus, β-catenin induction of Nur77 expression is mainly mediated through its activation of the Nur77 gene promoter.

Figure 6.

Induction of Nur77 by DCA. A) Real-time PCR analysis. Indicated colon cancer cell lines were treated with 10 μM DCA for 1 h. **P < 0.01 vs. corresponding controls. B) Knocking down β-catenin inhibits the effect of DCA on inducing Nur77 expression. Levels of Nur77 mRNA in SW480 and SW480/siβ stable cells treated with 10 μM DCA for 1 h were examined by real-time PCR. C) Induction of Nur77 promoter activity by β-catenin. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with pNur77 reporter together with 10 ng or 20 ng β-catenin for 30 h and then subjected to analysis of luciferase activity. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vector control. D) Knocking down β-catenin inhibits the effect of DCA on inducing Nur77 promoter activity. SW480 and SW480/siβ stable cells were transfected with pNur77 reporter and subjected to 10 μM DCA treatment for 20 h. For reporter assays, β-galactosidase expression vector was also included to normalize the luciferase activity. **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle control.

Synergistic activation of the Nur77 promoter by β-catenin, c-Fos, and c-Jun

We previously reported that AP-1 was involved in induction of Nur77 transcription (43). The above observation that β-catenin played a role in regulating Nur77 transcription prompted us to determine the effect of β-catenin and AP-1 alone or together on Nur77 transcription. To this end, expression vectors for β-catenin, c-Jun, and c-Fos were transfected into HEK293T cells and evaluated for their regulation of pNur77 promoter activity by the reporter assays. Cotransfection of c-Fos and c-Jun induced pNur77 promoter activity, which was further enhanced by β-catenin cotransfection and DCA treatment (Fig. 7A). Such action was also demonstrated in an artificial AP-1 reporter gene (pAP-1) (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Synergistic activation of Nur77 promoter activity by β-catenin and AP-1. A, B) Effect of β-catenin and AP-1. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with pNur77 (A) or pAP-1 (B) reporter gene together with expression vectors for c-Fos, c-Jun, and β-catenin as indicated. Cells were then treated with vehicle or 10 μM DCA for 20 h and assayed for reporter activity. β-Galactosidase expression vector was also included in each transfection. Relative luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity. C) Interaction of endogenous β-catenin with c-Fos and c-Jun. Lysates from SW480 cells treated with vehicle or 10 μM DCA were analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation assays using anti-β-catenin antibody or control IgG. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted using antibodies for c-Fos, c-Jun, and β-catenin. D, E) Interaction of transfected β-catenin and AP-1. HEK293T cells transfected with HA-β-catenin, c-Fos, and c-Jun were subjected to 10 μM DCA treatment for 3 h. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with either anti-HA (D), anti-c-Jun or anti-c-Fos (E) antibodies. IgG served as control in each coimmunoprecipitation.

We next studied whether the synergistic induction of Nur77 promoter activity by β-catenin and AP-1 was due to their interaction. Immunoprecipitation assays using anti-β-catenin showed that a significant amount of c-Fos and c-Jun was coimmunoprecipitated together with endogenous β-catenin from SW480 cells (Fig. 7C). The interaction between β-catenin and c-Jun and c-Fos was enhanced when cells were exposed to DCA. To confirm the interaction, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with expression vectors for HA-β-catenin, c-Fos, and c-Jun. Our coimmunoprecipitation assays showed that transfected c-Fos and c-Jun were coimmunoprecipitated with HA-β-catenin by anti-HA antibody but not by IgG control (Fig. 7D). Similarly, immunoprecipitation of either c-Fos or c-Jun resulted in coimmunoprecipitation of HA-β-catenin, both of which was enhanced by DCA (Fig. 7E). As expected, cotransfection of c-Fos and c-Jun led to their mutual coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 7E). Thus, the synergistic induction of Nur77 promoter activity by β-catenin and AP-1 in response to DCA is likely due to their interaction.

AP-1 binding sites on the Nur77 promoter mediate the effect of β-catenin and DCA

As the Nur77 promoter contained no typical sequence for Lef/Tcf-binding but possessed 4 putative AP-1 binding sites within the first 200 bp upstream of the Nur77 ATG site (Fig. 8A) (44, 45), we examined whether the AP-1-site-containing region could be bound by β-catenin, c-Fos, and c-Jun in the presence of DCA by ChIP assays. Our results showed that treatment of SW480 cells with DCA resulted in strong amplification of the AP-1-binding region in the immunoprecipitates of β-catenin, c-Fos, or c-Jun, but not in that of TCF4 (Fig. 8B). As a control, the distal upstream sequence between −1650 and −1450 bp was not detected in any of the above chromatin immunoprecipitates.

Figure 8.

Identification of DCA-response elements in the Nur77 promoter. A) Schematic representation of AP-1-binding sites in the Nur77 promoter. B) Binding of β-catenin and AP-1 to the Nur77 promoter by ChIP assays. PCR amplifications using the indicated primers (see panel A) were conducted in chromatin-immunoprecipitated DNA purified from immunoprecipitates using antibody against β-catenin, c-Fos, c-Jun, or TCF4. C) Mutation analysis of the Nur77 promoter. Individual or simultaneous mutations were introduced into the pNur77/wt reporter containing 4 AP-1 binding sites to generate pNur77/m1, pNur77/m2, pNur77/m3, and pNur77/m4 as indicated. SW480 cells transfected with the indicated reporter gene were treated with 10 μM DCA for 20 h and analyzed for reporter activity. Relative luciferase reporter activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity. **P < 0.01 vs. control; ▴▴P < 0.01, ■■P < 0.01 vs. corresponding wt.

To further study the role of AP-1-binding sites in the Nur77 promoter, luciferase reporter assays were performed after transfection of SW480 cells with Nur77 promoter reporters containing the first 200-bp sequences with either intact (pNur77/wt) or mutated AP-1 sites. The core AP-1 sequences and the mutated forms were indicated in Fig. 8C. We found that DCA could dose-dependently induce pNur77/wt activity, whereas the effect of DCA was greatly impaired when pNur77/m1 with mutation made at the AP-1 site between −200 and −194 bp was used (Fig. 8C). Similar results were obtained when mutations were introduced into the second AP-1-binding site between −180 and −174 bp (pNur77/m2), whereas other AP-1 site mutations, either between −37 and −31 bp (pNur77/m3) or −8 and −2 bp (pNur77/m4), showed no apparent effect on DCA-induced luciferase activity. Simultaneous mutations of m1 and m2 (pNur77/m1,2) completely impaired the effect of DCA on inducing Nur77 promoter activity (Fig. 8C). Thus, our results demonstrate that 2 AP-1 binding sites within the region between −200 and −174 bp on the Nur77 promoter are crucial for induction of Nur77 promoter activity by DCA.

DISCUSSION

We showed that Nur77 was overexpressed in human colon tumor tissues (Figs. 1A and 5A) and that Nur77 expression was significantly enhanced during colon carcinogenesis in animals (Fig. 1B, C). These results are consistent with previous observation (8), suggesting that Nur77 expression may contribute to the development of this disease. Overexpression of Nur77 was also observed in several other tumor types, including bladder and pancreatic carcinomas (9, 10), and was demonstrated to have oncogenic potential in lung and cervical cancer cells (11, 13). Thus, inappropriate overexpression of Nur77 may have a general role in tumorigenesis.

In this study, we provide convincing evidence that Nur77 expression serves to promote the growth and survival of colon cancer cells. We showed that DCA-induced Nur77 expression was associated with its effects on stimulating colon cancer cell growth (Fig. 2C), cell migration (Fig. 3D), colony formation (Fig. 2H), and PCNA expression (Fig. 1C). The DCA induction of Nur77 was also followed by up-regulation of antiapoptotic protein BRE (Fig. 2D, E) and angiogenic factor VEGF (Fig. 2F), whose expression could be greatly inhibited by Nur77 siRNA. Inhibition of Nur77 expression also abrogated the effect of DCA on inducing colony formation (Fig. 2H) and caused extensive apoptosis of colon cancer cells (Fig. 3A, B). It is therefore conceivable that disturbance of Nur77 activity may affect the survival of colon cancer cells. Consistently, induction of Nur77 nuclear export led to apoptosis of colon cancer cells despite the fact that cytoplasmic Nur77 failed to target mitochondria (20). Similarly, treatment of colon cancer cells with Nur77-active C-DIMs that appeared to enhance Nur77 transcriptional activity directly or indirectly resulted in death of colon cancer cells (8). Although the mechanism by which Nur77 acts to maintain the growth and survival of colon cancer cells remains to be fully determined, we found that Nur77 induced by DCA, LiCl, and AOM was accumulated in the nucleus (Fig. 5B) and that Nur77 expression was associated with induction of BRE and VEGF. Thus, it is likely that Nur77 acts to promote colon cancer cell growth and survival through its nuclear action, consistent with our observation made in lung cancer cells (11).

An important finding reported here is our demonstration that β-catenin is involved in the up-regulation of Nur77 in colon cancer cells. β-Catenin, a key signaling molecule of the Wnt signaling pathway, is crucial for colon cancer development because it is aberrantly activated in >90% of colon tumors (23, 28, 29). We found that nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in human colon tumor tissues was closely associated with elevated Nur77 expression (Fig. 5A). In addition, transfection of β-catenin/S33Y, an undegradable constitutively active β-catenin mutant, strongly increased Nur77 expression (Fig. 5D), while inhibition of β-catenin by siRNA impaired the effect of DCA on inducing Nur77 expression (Fig. 5E). In colon cancer cells, DCA, AOM and LiCl, which are known to activate β-catenin (27, 28, 33, 37), potently induced Nur77 expression (Fig. 5B), suggesting that elevated levels of Nur77 contribute to the development of colon cancer. This notion is supported by a recent report demonstrated that levels of NR4A2, a member of Nur77 family, were considerably increased in intestinal epithelium from Apc−/+ mouse adenomas and sporadic colorectal carcinomas (46).

DCA is a major risk factor for colon cancer, which was shown to potently activate several intracellular signal cascades, including PI3K and JNK pathways (33, 47–49). Altered regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling often occurs in cancers, including colon carcinoma (49–51). PI3K/Akt activation could lead to β-catenin nuclear translocation via inactivation of the Akt substrate GSK-3β (28, 49) or through direct Akt-mediated site-specific phosphorylation of β-catenin by a GSK-independent mechanism (32). Our results demonstrated that DCA-induced Nur77 expression required PI3K/Akt-dependent activation of β-catenin as DCA induction of Nur77 expression was suppressed by transfection of dn-Akt (Fig. 4D, E) and treatment with PI3K inhibitor (Fig. 5C). In addition to activation of PI3K and β-catenin, our results showed that DCA induction of Nur77 required activation of JNK pathway (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, we showed that DCA activation of JNK pathway was mainly due to its activation of JNK2, whereas the JNK1 activity was only slightly affected (Fig. 4C), indicating that JNK2 plays a major role in regulation of DCA-induced Nur77 expression. Previous studies showed that activation of JNK1 was associated with caspase activation and cell death, and JNK2 activation led to cell protection (52–54), which is in agreement with our finding that JNK2-dependent up-regulation of Nur77 by DCA correlated with colon cancer cell survival and proliferation (Figs. 2 and 3). Because both PI3K/Akt/β-catenin and JNK/AP-1 pathways are often abnormally activated in colon cancer (50, 51, 55), our finding that Nur77 serves as a downstream target of both pathways suggests that Nur77 may mediate some biological effects of these signaling cascades during the development of this disease.

An interesting observation described here is the convergency of β-catenin and AP-1 signaling pathways on inducing Nur77 expression. Indeed, many target genes involved in cancer cell growth and invasion, such as c-Jun, Fra-1, c-myc, cyclin D1, cd44, WNTs, AKT1, laminin-5γ2, osteopontin, uPA, and MMPs, are subjected to coregulation by both pathways through different mechanisms (55–60). For instance, c-Jun is critically involved in the canonical Wnt pathway by cooperating with Dvl to activate β-catenin/TCFs transcription activity (61). Also, β-catenin was shown to directly interact with both c-Fos and c-Jun, leading to activation of cyclin D1 and c-myc genes through the typical TCF-binding element (57). On the other hand, induction of laminin-5γ2 and MMP-7 expression by β-catenin and AP-1 required both AP-1 and TCF binding sites in their promoters (58, 59). Interestingly, several β-catenin target genes such as c-Jun and Fra-1 are also the components of AP-1 complex, whose expression in turn enhanced the transcriptional activity of β-catenin, forming a positive feedback circuit to amplify the β-catenin signaling (60). AP-1 and β-catenin are often simultaneously overactivated in many tumors, including colon carcinoma (55, 57), indicating that their synergism is of pathological and clinical importance. Our analysis of the synergistic effect of β-catenin and AP-1 on inducing Nur77 promoter activity revealed a strong physical interaction between β-catenin and AP-1 (c-Fos/c-Jun) (Fig. 7).

The Nur77 promoter contains no typical Lef/Tcf binding sites for canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In addition, inhibition of TCF-4 by siRNA did not significantly inhibit the effect of DCA on inducing Nur77 expression (data not shown). In studying the mechanism by which β-catenin activated Nur77 gene transcription, we showed that β-catenin could potently potentiate the AP-1 (c-Fos/c-Jun) on activating an artificial AP-1 reporter gene (Fig. 7B). The function synergism between β-catenin and AP-1 on inducing Nur77 gene expression was dependent on AP-1 binding sites, and we identified 2 AP-1 response elements (−200 to −194 and −180 to −174 bp) on the Nur77 promoter that were active in response to DCA and could be activated by β-catenin/AP-1 (Fig. 8C and data not shown). These AP-1 binding sites, together with other downstream AP-1 sites in the Nur77 promoter region, were previously identified; their activity was induced in response to various stimuli, including serum, nerve growth factor, 8 Br-cAMP, human T-lymphotropic virus type I Tax protein, and chemotherapeutic agent n-butylenephthalide (19, 44, 45, 62, 63). Data presented here showed for the first time that activated β-catenin in colon cancer cells could potentiate and optimize the AP-1 transcriptional activity on inducing Nur77 gene expression through the AP-1 sites.

In summary, our results demonstrate that Nur77 is a highly susceptible target for colonic carcinogenic stimuli and serves to mediate some biological effects of Wnt/β-catenin and AP-1 signaling pathways. Our findings thus provide not only a new molecular basis for understanding the biological properties of colon cancer, but also useful resources for future development of new therapeutic strategy to combat colon cancer by targeting Nur77.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by grants to J.-Z.Z. from the 863 Program (2007AA09Z404), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; 30971445), the Key Science and Technology Planning Project (2007I0023), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (2009J01198), and the NSFC/Hong Kong Research Grants Council (RGC; 30931160431), a grant to A.S.-T.W. (N_HKU 735/09), and grants to X.Z. from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (CA109345, CA140980, GM089927), the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command (PCRPW81XWH-08-1-0478), and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2008Y0062). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fahrner T. J., Carroll S. L., Milbrandt J. (1990) The NGFI-B protein, an inducible member of the thyroid/steroid receptor family, is rapidly modified posttranslationally. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 6454–6459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang X. K. (2007) Targeting Nur77 translocation. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 11, 69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zeng J. Z., Zhang X. K. (2007) Nongenomic actions of retinoids: role of Nur77 and RXR in the regulation of apoptosis and inflammation. Anti-Inflamm. Anti-Allergy Agents Med. Chem. 6, 315–331 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hazel T. G., Nathans D., Lau L. F. (1988) A gene inducible by serum growth factors encodes a member of the steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85, 8444–8448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilson T. E., Fahrner T. J., Johnston M., Milbrandt J. (1991) Identification of the DNA binding site for NGFI-B by genetic selection in yeast. Science 252, 1296–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Philips A., Lesage S., Gingras R., Maira M. H., Gauthier Y., Hugo P., Drouin J. (1997) Novel dimeric Nur77 signaling mechanism in endocrine and lymphoid cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5946–5951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Milbrandt J. (1988) Nerve growth factor induces a gene homologous to the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Neuron 1, 183–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cho S. D., Yoon K., Chintharlapalli S., Abdelrahim M., Lei P., Hamilton S., Khan S., Ramaiah S. K., Safe S. (2007) Nur77 agonists induce proapoptotic genes and responses in colon cancer cells through nuclear receptor-dependent and nuclear receptor-independent pathways. Cancer Res. 67, 674–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cho S. D., Lee S. O., Chintharlapalli S., Abdelrahim M., Khan S., Yoon K., Kamat A. M., Safe S. (2010) Activation of nerve growth factor-induced B alpha by methylene-substituted diindolylmethanes in bladder cancer cells induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth. Mol. Pharmacol. 77, 396–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee S. O., Abdelrahim M., Yoon K., Chintharlapalli S., Papineni S., Kim K., Wang H., Safe S. H. (2010) Inactivation of the orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 inhibits pancreatic cancer cell and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 70, 6824–6836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kolluri S. K., Bruey-Sedano N., Cao X., Lin B., Lin F., Han Y. H., Dawson M. I., Zhang X. K. (2003) Mitogenic effect of orphan receptor TR3 and its regulation by MEKK1 in lung cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 8651–8667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee M. O., Kang H. J., Cho H., Shin E. C., Park J. H., Kim S. J. (2001) Hepatitis B virus X protein induced expression of the Nur77 gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 288, 1162–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ke N., Claassen G., Yu D. H., Albers A., Fan W., Tan P., Grifman M., Hu X., Defife K., Nguy V., Meyhack B., Brachat A., Wong-Staal F., Li Q. X. (2004) Nuclear hormone receptor NR4A2 is involved in cell transformation and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 64, 8208–8212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu J., Zhou W., Li S. S., Sun Z., Lin B., Lang Y. Y., He J. Y., Cao X., Yan T., Wang L., Lu J., Han Y. H., Cao Y., Zhang X. K., Zeng J. Z. (2008) Modulation of orphan nuclear receptor Nur77-mediated apoptotic pathway by acetylshikonin and analogues. Cancer Res. 68, 8871–8880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thompson J., Winoto A. (2008) During negative selection, Nur77 family proteins translocate to mitochondria where they associate with Bcl-2 and expose its proapoptotic BH3 domain. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1029–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rajpal A., Cho Y. A., Yelent B., Koza-Taylor P. H., Li D., Chen E., Whang M., Kang C., Turi T. G., Winoto A. (2003) Transcriptional activation of known and novel apoptotic pathways by Nur77 orphan steroid receptor. EMBO J. 22, 6526–6536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhan Y., Du X., Chen H., Liu J., Zhao B., Huang D., Li G., Xu Q., Zhang M., Weimer B. C., Chen D., Cheng Z., Zhang L., Li Q., Li S., Zheng Z., Song S., Huang Y., Ye Z., Su W., Lin S. C., Shen Y., Wu Q. (2008) Cytosporone B is an agonist for nuclear orphan receptor Nur77. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 548–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu J. J., Zeng H. N., Zhang L. R., Zhan Y. Y., Chen Y., Wang Y., Wang J., Xiang S. H., Liu W. J., Wang W. J., Chen H. Z., Shen Y. M., Su W. J., Huang P. Q., Zhang H. K., Wu Q. (2010) A unique pharmacophore for activation of the nuclear orphan receptor Nur77 in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Res. 70, 3628–3637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen Y. L., Jian M. H., Lin C. C., Kang J. C., Chen S. P., Lin P. C., Hung P. J., Chen J. R., Chang W. L., Lin S. Z., Harn H. J. (2008) The induction of orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 expression by n-butylenephthalide as pharmaceuticals on hepatocellular carcinoma cell therapy. Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 1046–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilson A. J., Arango D., Mariadason J. M., Heerdt B. G., Augenlicht L. H. (2003) TR3/Nur77 in colon cancer cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 63, 5401–5407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin B., Kolluri S. K., Lin F., Liu W., Han Y. H., Cao X., Dawson M. I., Reed J. C., Zhang X. K. (2004) Conversion of Bcl-2 from protector to killer by interaction with nuclear orphan receptor Nur77/TR3. Cell 116, 527–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Imray C. H., Radley S., Davis A., Barker G., Hendrickse C. W., Donovan I. A., Lawson A. M., Baker P. R., Neoptolemos J. P. (1992) Faecal unconjugated bile acids in patients with colorectal cancer or polyps. Gut 33, 1239–1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Markowitz S. D., Dawson D. M., Willis J., Willson J. K. (2002) Focus on colon cancer. Cancer Cell 1, 233–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chiu B. C., Ji B. T., Dai Q., Gridley G., McLaughlin J. K., Gao Y. T., Fraumeni J. F., Jr., Chow W. H. (2003) Dietary factors and risk of colon cancer in Shanghai, China. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 12, 201–208 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mai V., Colbert L. H., Berrigan D., Perkins S. N., Pfeiffer R., Lavigne J. A., Lanza E., Haines D. C., Schatzkin A., Hursting S. D. (2003) Calorie restriction and diet composition modulate spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis in Apc(Min) mice through different mechanisms. Cancer Res. 63, 1752–1755 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin C. X., Umemoto A., Seraj M. J., Mimura S., Monden Y. (2001) Effect of bile acids on formation of azoxymethane-induced aberrant crypt foci in colostomized F344 rat colon. Cancer Lett. 169, 121–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Flynn C., Montrose D. C., Swank D. L., Nakanishi M., Ilsley J. N., Rosenberg D. W. (2007) Deoxycholic acid promotes the growth of colonic aberrant crypt foci. Mol. Carcinog. 46, 60–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bienz M., Clevers H. (2000) Linking colorectal cancer to Wnt signaling. Cell 103, 311–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Van de Wetering M., Sancho E., Verweij C., de Lau W., Oving I., Hurlstone A., van der Horn K., Batlle E., Coudreuse D., Haramis A. P., Tjon-Pon-Fong M., Moerer P., van den Born M., Soete G., Pals S., Eilers M., Medema R., Clevers H. (2002) The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell 111, 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clevers H. (2006) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127, 469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. MacDonald B. T., Tamai K., He X. (2009) Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell 17, 9–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fang D., Hawke D., Zheng Y., Xia Y., Meisenhelder J., Nika H., Mills G. B., Kobayashi R., Hunter T., Lu Z. (2007) Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by AKT promotes beta-catenin transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11221–11229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pai R., Tarnawski A. S., Tran T. (2004) Deoxycholic acid activates beta-catenin signaling pathway and increases colon cell cancer growth and invasiveness. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2156–2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mimori-Kiyosue Y., Tsukita S. (2001) Where is APC going? J. Cell. Biol. 154, 1105–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Phelps R. A., Chidester S., Dehghanizadeh S., Phelps J., Sandoval I. T., Rai K., Broadbent T., Sarkar S., Burt R. W., Jones D. A. (2009) A two-step model for colon adenoma initiation and progression caused by APC loss. Cell 137, 623–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Blum C. A., Xu M., Orner G. A., Fong A. T., Bailey G. S., Stoner G. D., Horio D. T., Dashwood R. H. (2001) beta-Catenin mutation in rat colon tumors initiated by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine and 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline, and the effect of post-initiation treatment with chlorophyllin and indole-3-carbinol. Carcinogenesis 22, 315–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hirose Y., Kuno T., Yamada Y., Sakata K., Katayama M., Yoshida K., Qiao Z., Hata K., Yoshimi N., Mori H. (2003) Azoxymethane-induced beta-catenin-accumulated crypts in colonic mucosa of rodents as an intermediate biomarker for colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 24, 107–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hashizume H., Falcon B. L., Kuroda T., Baluk P., Coxon A., Yu D., Bready J. V., Oliner J. D., McDonald D. M. (2010) Complementary actions of inhibitors of angiopoietin-2 and VEGF on tumor angiogenesis and growth. Cancer Res. 70, 2213–2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stein U., Arlt F., Walther W., Smith J., Waldman T., Harris E. D., Mertins S. D., Heizmann C. W., Allard D., Birchmeier W., Schlag P. M., Shoemaker R. H. (2006) The metastasis-associated gene S100A4 is a novel target of beta-catenin/T-cell factor signaling in colon cancer. Gastroenterology 131, 1486–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ikari A., Sanada A., Okude C., Sawada H., Yamazaki Y., Sugatani J., Miwa M. (2010) Up-regulation of TRPM6 transcriptional activity by AP-1 in renal epithelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 222, 481–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eferl R., Wagner E. F. (2003) AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Silvers A. L., Bachelor M. A., Bowden G. T. (2003) The role of JNK and p38 MAPK activities in UVA-induced signaling pathways leading to AP-1 activation and c-Fos expression. Neoplasia 5, 319–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li Y., Lin B., Agadir A., Liu R., Dawson M. I., Reed J. C., Fontana J. A., Bost F., Hobbs P. D., Zheng Y., Chen G. Q., Shroot B., Mercola D., Zhang X. K. (1998) Molecular determinants of AHPN (CD437)-induced growth arrest and apoptosis in human lung cancer cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 4719–4731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Uemura H., Mizokami A., Chang C. (1995) Identification of a new enhancer in the promoter region of human TR3 orphan receptor gene: a member of steroid receptor superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 5427–5433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yoon J. K., Lau L. F. (1994) Involvement of JunD in transcriptional activation of the orphan receptor gene nur77 by nerve growth factor and membrane depolarization in PC12 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 7731–7743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Holla V. R., Mann J. R., Shi Q., DuBois R. N. (2006) Prostaglandin E2 regulates the nuclear receptor NR4A2 in colorectal cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2676–2682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jean-Louis S., Akare S., Ali M. A., Mash E. A., Jr., Meuillet E., Martinez J. D. (2006) Deoxycholic acid induces intracellular signaling through membrane perturbations. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14948–14960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Debruyne P. R., Bruyneel E. A., Karaguni I. M., Li X., Flatau G., Muller O., Zimber A., Gespach C., Mareel M. M. (2002) Bile acids stimulate invasion and haptotaxis in human colorectal cancer cells through activation of multiple oncogenic signaling pathways. Oncogene 21, 6740–6750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Raufman J. P., Shant J., Guo C. Y., Roy S., Cheng K. (2008) Deoxycholyltaurine rescues human colon cancer cells from apoptosis by activating EGFR-dependent PI3K/Akt signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 215, 538–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Luo J., Manning B. D., Cantley L. C. (2003) Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell 4, 257–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vivanco I., Sawyers C. L. (2002) The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 489–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tournier C., Hess P., Yang D. D., Xu J., Turner T. K., Nimnual A., Bar-Sagi D., Jones S. N., Flavell R. A., Davis R. J. (2000) Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science 288, 870–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu J., Minemoto Y., Lin A. (2004) c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase 1 (JNK1), but not JNK2, is essential for tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced c-Jun kinase activation and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 10844–10856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jaeschke A., Karasarides M., Ventura J. J., Ehrhardt A., Zhang C., Flavell R. A., Shokat K. M., Davis R. J. (2006) JNK2 is a positive regulator of the cJun transcription factor. Mol. Cell 23, 899–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Saadeddin A., Babaei-Jadidi R., Spencer-Dene B., Nateri A. S. (2009) The links between transcription, beta-catenin/JNK signaling, and carcinogenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 1189–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mann B., Gelos M., Siedow A., Hanski M. L., Gratchev A., Ilyas M., Bodmer W. F., Moyer M. P., Riecken E. O., Buhr H. J., Hanski C. (1999) Target genes of beta-catenin-T cell-factor/lymphoid-enhancer-factor signaling in human colorectal carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 1603–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Toualbi K., Guller M. C., Mauriz J. L., Labalette C., Buendia M. A., Mauviel A., Bernuau D. (2007) Physical and functional cooperation between AP-1 and beta-catenin for the regulation of TCF-dependent genes. Oncogene 26, 3492–3502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Brabletz T., Jung A., Dag S., Hlubek F., Kirchner T. (1999) beta-catenin regulates the expression of the matrix metalloproteinase-7 in human colorectal cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 155, 1033–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hlubek F., Jung A., Kotzor N., Kirchner T., Brabletz T. (2001) Expression of the invasion factor laminin gamma2 in colorectal carcinomas is regulated by beta-catenin. Cancer Res. 61, 8089–8093 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dihlmann S., Kloor M., Fallsehr C., von Knebel Doeberitz M. (2005) Regulation of AKT1 expression by beta-catenin/Tcf/Lef signaling in colorectal cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 26, 1503–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gan X. Q., Wang J. Y., Xi Y., Wu Z. L., Li Y. P., Li L. (2008) Nuclear Dvl, c-Jun, beta-catenin, and TCF form a complex leading to stabilization of beta-catenin-TCF interaction. J. Cell. Biol. 180, 1087–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Williams G. T., Lau L. F. (1993) Activation of the inducible orphan receptor gene nur77 by serum growth factors: dissociation of immediate-early and delayed-early responses. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 6124–6136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Inaoka Y., Yazawa T., Uesaka M., Mizutani T., Yamada K., Miyamoto K. (2008) Regulation of NGFI-B/Nur77 gene expression in the rat ovary and in Leydig tumor cells MA-10. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 75, 931–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]