Abstract

BACKGROUND

CEACAM1, CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 represent three of the CEACAM subfamily members expressed on intestinal epithelial cells (IECs). Deficiency in their expression, as seen in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), results in the lack of activation of CD8+ regulatory T cells in the mucosa. Since CEACAM expression was shown to be regulated by the transcription factor SOX9, we sought to determine whether the defect in CEACAM expression in IBD was related to aberrant SOX9 expression.

METHODS

IECs and lamina propria lymphocytes (LPLs) were freshly isolated from colonic tissues. T84 and HT29 16E cells were co-cultured with LPLs. SOX9 and CEACAM subfamily member expression was assessed by Real-Time PCR, Western Blot, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence.

RESULTS

In Crohn’s disease (CD) but not in ulcerative colitis (UC), a significant reduction in mRNA and protein expression for CEACAM1 and 5 was noted, in contrast, no difference in SOX9 mRNA expression was seen. However, nuclear SOX9 immunostaining was increased in CD IECs. Furthermore, SOX9 protein was reduced in the cytoplasm of LPL stimulated- T84 and HT29 16E cells, while CEACAM5 expression was increased.

CONCLUSIONS

The defect in CEACAM family members in CD IECs appears to be related to the aberrant nuclear localization of SOX9. Changes in SOX9 expression in the CD mucosa relate to local microenvironment and altered IEC:LPL crosstalk.

Keywords: CEACAM, epithelial cells, Crohn’s disease

INTRODUCTION

It is well recognized that the nature of the immune response in the intestinal tract is different than in peripheral lymphoid organs. The immunologic tone of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue is one of the suppression rather than active immunity while still being capable of distinguishing pathogens from normal flora. Failure to control mucosal immune responses may lead to inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). It has been suggested that this normally immunosuppressed state may relate to unique antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and unique T-cell populations. Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) have been proposed to act as nonprofessional APCs. The interaction of IECs with T cells through a unique complex, formed by a CEACAM subfamily member (gp180) and the non classical class I molecule CD1d (1-9), results in the expansion of CD8+ Tregs (TrE).

CEACAM family members are typically cell membrane associated glycoproteins, and are part of the immunoglobulin superfamily. CEACAM1 (BGP), CEACAM5 (CEA) and CEACAM6 (NCA) are expressed on IECs. CEACAM1 contains a hydrophobic transmembrane domain followed by either a short or long cytoplasmic domain, whereas CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 attach to the cell membrane via a GPI-anchor. They represent markers of IEC differentiation and play a role in cell adhesion, signal transduction and innate immunity (10). CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 are upregulated in epithelial derived tumors such as colorectal cancer (11, 12). Using B9, a monoclonal antibody directed against gp180, we documented defective expression of this glycoprotein in IBD (13). In CD, there was absence of staining on IECs derived from both inflamed or non-inflamed areas. In UC, the pattern of expression was patchy and there was a loss of basolateral staining. B9 recognizes a common epitope in the N domain of several CEACAM family members (data not published). Thus, it is unclear which of the CEACAM family members is involved in the activation of CD8+ T cells. Additionally, the mechanism underlying the defect in CEACAM family member expression in IBD has not been defined.

CEACAM5 is overexpressed in many types of human cancers and is commonly used as a clinical marker of colon cancer (14, 15). In colon cancer, this over-expression protects cells against apoptosis and contributes to carcinogenesis (16, 17). The transcription factor SOX9, a crypt cell expressed transcription factor, can down-regulate CEACAM5 gene expression (18). SOX9 is well known for its role in the differentiation of several tissues including chondrocytes, male gonads, neural crest and spinal cord glial cells (19). SOX9 belongs to the high motility group box (HMG) transcription factor family and is regulated by the Wnt pathway (20). Recent studies have emphasized the role of SOX9 in Paneth cell differentiation (21, 22). Two reports have demonstrated that after inactivating the SOX9 gene Paneth cells were not seen in vivo. Although some differences were seen in goblet cell differentiation and the morphology of the colonic epithelium was altered, the differentiation of other intestinal epithelial cell lineages was not affected. Furthermore, CEACAM1, the only CEACAM family member expressed on mouse IECs, has been directly linked to SOX9 transcriptional activity (23). SOX9 was found to transcriptionally repress CDX2, that is normally expressed in the mature villus cells of the intestinal epithelium (24). We have recently described that CDX2 expression was increased in crypt CD IECs leading to an enhancement of IEC differentiation (25). Given its role in the process of differentiation and its documented expression in mouse intestine, we postulated a possible role for SOX9 in IEC differentiation and in the regulation of CEACAM family member expression in IBD (24, 26).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of human intestinal epithelial cells and lamina propria lymphocytes

Surgical specimens from patients undergoing colon resection for cancer (at least 10 cm from the tumor), diverticulitis and IBD or biopsies from patients undergoing endoscopy at Mount Sinai and the S. Orsola Medical Center were used as a source of IECs and LPLs. IECs and LPLs were isolated as described previously (27). The tissue was washed in PBS and digested several times with Dispase II (3 mg/ml) (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After each treatment, the supernatant (releasing IECs or LPLs) was collected and washed in medium (RPMI). The viability of isolated IECs and LPLs was at least 95%.

Cell lines

T84 cell line, a human cell line derived from a colon carcinoma, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). T84 cells were cultured in Dulbecco-Vogt modified Eagle’s medium and Ham’s F12 medium (DMEM/F12) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). HT29 Clone 16E (HT29 16E), a goblet cell line and derivative of the HT29 human colonic cancer cell line was a gift of Pr. C. L. Laboisse (28). This cell line was cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% FCS.

IEC line: LPL co-cultures

T84 and HT29 16E cell lines were co-cultured with freshly isolated LPLs. The co-cultures were set up with a ratio of 1 IEC/1 LPL for 4 days. The IEC lines alone served as negative controls. Adherent cells were washed with PBS to remove the LPLs and then processed as follow.

RNA purification and Real-Time PCR

IECs were processed for Trizol extraction (Invitrogen) using a previously described protocol (29). Briefly, 5 μg of total RNA was converted into cDNA and was used for a 40 cycle three-step PCR using an ABI Prism 7900 (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.4, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5x SYBR Green I (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR), 200 nM each primer, and 0.5 U Platinum Taq (Invitrogen). The number of target copies in each sample was extrapolated from its detection threshold (CT) value using a plasmid or purified PCR product standard curve included on each plate. Three different housekeeping genes were used as controls. Each transcript in each sample was assayed three times, and the median CT values were used to calculate the fold increase in gene expression as 2-ΔΔCT where the ΔΔCT corresponds to (Mean CTTARGET NORMAL- CTTARGET UC/CD)-(Mean CTCONTROL NORMAL-CTCONTROL UC/CD) for mRNA expression in freshly isolated IECs, or (Mean CTTARGET IEC line alone- CTTARGET IEC line+LPL)-(Mean CTCONTROL IEC line alone- CTCONTROL IEC line+LPL) for mRNA expression in IEC lines co-cultured with freshly isolated LPLs. By definition ΔΔCT in the control group equals 0 and 20 equals 1. With this method, we normalized our results to the reference genes and to the control group. The primers used in this study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for Real-Time PCR

| CEACAM1 (BGP) | Sense | TGACACAGGACCCTATGAGT |

| anti-sense | ACTGTGCAGGTGGGTTAGAG | |

| CEACAM5 (CEA) | Sense | GGTGCATCCCCTGGCAGA |

| anti-sense | GGTTGCCATCCACTCTTTCA | |

| CEACAM6 (NCA) | Sense | GCATGTCCCCTGGAAGGA |

| anti-sense | CGCCTTTGTACCAGCTGTAA | |

| SOX9 | sense | GACCTTTGGGCTGCCTTATA |

| anti-sense | GTCTGTCAGTGGGCTGATCC | |

| β-actin | sense | ACTGGAACGGTGAAGGTGAC |

| anti-sense | GTGGACTTGGGAGAGGACTG | |

| Rps11 | sense | GCCGAGACTATCTGCACTAC |

| anti-sense | ATGTCCAGCCTCAGAACTTC | |

| α-tubulin | sense | GCCTGGACCACAAGTTTGAC |

| anti-sense | TGAAATTCTGGGAGCATGAC |

Immunofluorescence staining of paraffin embedded sections

Paraffin embedded sections derived from surgical specimens and biopsies were dewaxed and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating for 10 min at 100 °C in 0.01 mol/L sodium citrate. Immunofluorescence staining was performed using murine mAb 5F4 anti-CEACAM1, murine mAb T84.66 anti-CEACAM5 and an Alexa-594 labeled anti-mouse Ig antibody (Invitrogen). The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). The slides were covered using Fluoromount-G mounting media (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL). All the samples were analyzed with a Leica SP5-DM Confocal microscope at 40x magnification. All experiments were repeated at least 5 times, and a representative result is shown for each experiment.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin embedded sections derived from surgical specimens and biopsies with a rabbit anti-SOX9 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Paraffin sections were dewaxed and rehydrated, and endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 1.5% H2O2 in methanol for 15 min. Antigen retrieval was performed by using 0.1% hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS at 37 °C for 5 min. The stainings were done according to the manufacturer’s protocol using a rabbit Histostain-Plus kit (Invitrogen). The sections were counterstained with Mayer’s Hematoxylin Solution (Sigma-Aldrich), dehydrated and covered. All the samples were analyzed with a Zeiss Axioskop light microscope at 20x and 40x magnification. All experiments were repeated at least 5 times and a representative result is shown for each experiment.

Western Blot analysis

Adherent cells were scraped from the plastic at 4°C into lysis buffer as previously described (25). The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using a Bio-Rad DC kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal protein concentrations of whole cell lysates were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Billerica, MA) and incubated overnight at 4°C with either a mouse anti-ERK2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), a murine mAb T84.66 anti-CEACAM5, or a rabbit anti-SOX9 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (Cell Signaling) respectively. The presence of bands was revealed with the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (ECL, Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA). All experiments were repeated at least 5 times, and a representative result is shown for each experiment.

Immunofluorescence staining of cell lines

Adherent cells were fixed with methanol at 4°C for 10 min. Immunofluorescence detection of SOX9 was performed using a rabbit anti-SOX9 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and a FITC labeled anti-rabbit Ig antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). The slides were covered using Vectashield mounting media for fluorescence (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). All the samples were analyzed with a Leica SP5-DM Confocal microscope at 100x magnification. All experiments were repeated at least 5 times, and a representative result is shown for each experiment.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as the mean values +/- SEM. Statistical significance was determined by 1-way ANOVA followed by post-test Newman-Keuls test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

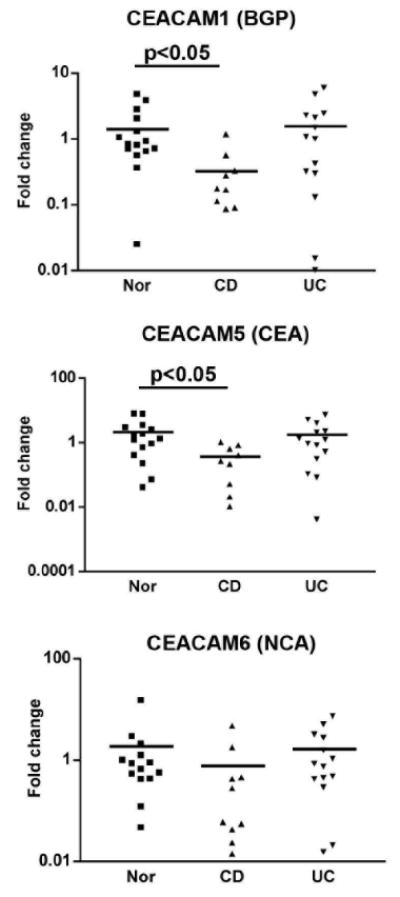

CD is associated with a reduction in CEACAM1, CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 mRNA in IECs

Previous work from our laboratory has demonstrated a role for gp180 in the activation of CD8+ regulatory T cells by IECs (1). Flow cytometric analyses documented defects in the expression of this molecule in IECs from CD and UC patients (13). The monoclonal antibody used in this study, B9, recognizes a number of CEACAM family members (11, 12). Thus, the expression of one or more CEACAM subfamily members may be affected in IBD IECs and the defect in expression may be transcriptional, post-transcriptional or reflect a defect in the glycosylation of these molecules. We therefore investigated CEACAM1, CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 mRNA expression (Figure 1). IEC mRNA was extracted from 13 normal (Nor), 8-10 CD and 13 UC samples and real-Time PCR was performed using specific primers for CEACAM1, CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 (Table 1). In Nor IECs, variable levels of CEACAM1, CEACAM5 and CEACAM6 mRNA expression were noted. In the CD group, there was less CEACAM1 mRNA expression versus the Nor group (0.33±0.12 versus 1.42±0.35 fold change, p<0.05); less CEACAM5 mRNA (0.37±0.12 versus 2.17±0.63 fold change, p<0.05); and a a decrease, albeit not significant, in CEACAM6 mRNA expression. In contrast, CEACAM1, 5 and 6 mRNA expression was comparable to the Nor group in UC IECs. Importantly, no differences were seen in CEACAM mRNA from CD IECs derived from active and inactive areas (data not shown). These data strongly support the probability that the defect in CEACAM1 and 5 expression in CD is at the transcriptional level.

Figure 1.

CEACAM1, 5 and 6 mRNA expression in surface epithelial cells of Nor, CD, and UC colonic tissues. The IECs were isolated and the mRNA was purified and analyzed by Real-Time PCR. The fold increase of mRNA expression was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods section.

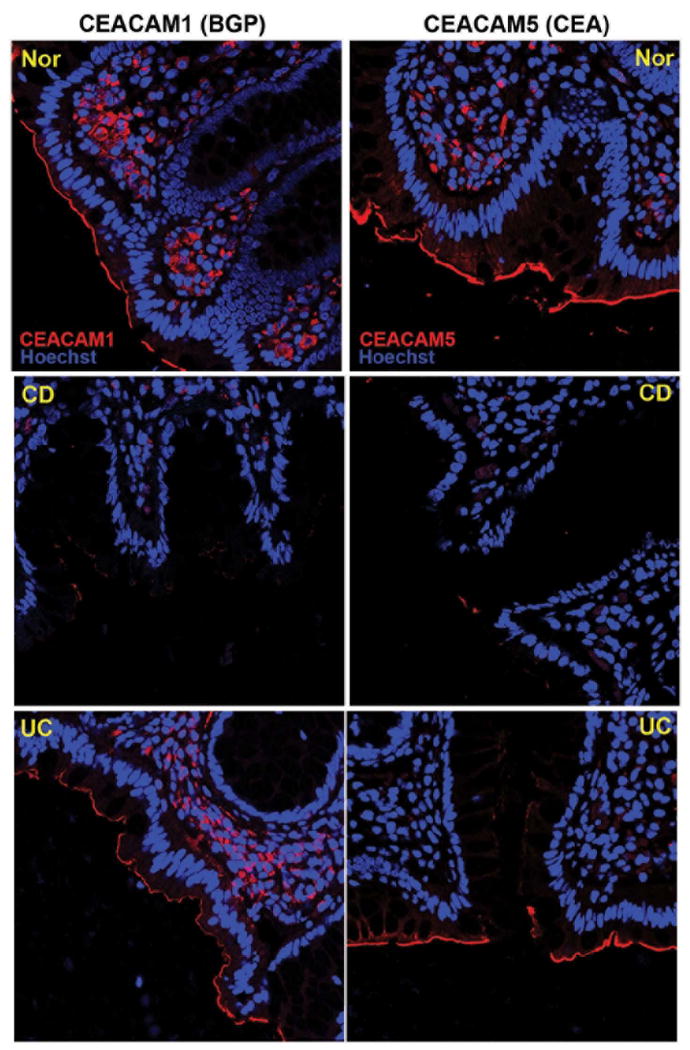

CEACAM1 and CEACAM5 staining of colonic specimens show different expression in Nor versus IBD mucosa

Given the differences noted above, we analyzed the protein expression of CEACAM1 and CEACAM5 by immunofluorescence staining in 6 normal, 5 CD and 5 UC specimens. The localization of CEACAM1 and 5 in normal colon revealed expression in surface IECs (Figure 2). There was a uniform decrease in CEACAM1 and CEACAM5 expression in CD mucosa. Thus, we confirmed and extended our previous findings demonstrating that CD IECs possess a defect in both CEACAM1 and 5 protein expression.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence staining for CEACAM1 and 5 antibodies (red) in Nor, CD and UC colonic tissues. The nuclei were staining with Hoechst 33342 (blue). All the samples were analyzed with a Leica SP5-DM Confocal microscope at 40x magnification. These data are representative of 5 experiments.

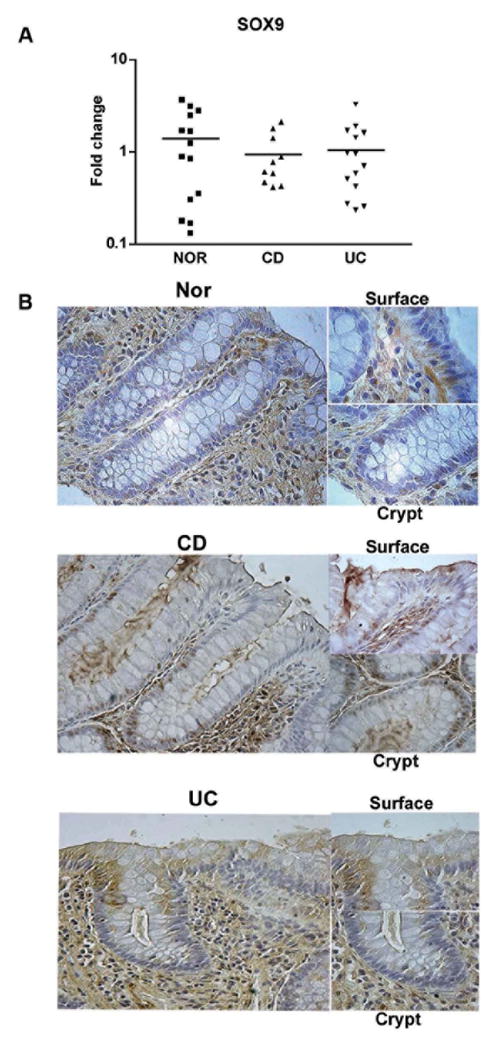

SOX9 protein but not mRNA expression is increased in CD mucosa

The downregulation of CEACAM gene expression by SOX9 was initially proposed by Blache’s group using the HT29 16E cell line (18). We therefore investigated if this link between SOX9 and CEACAM family members is involved in CEACAM family member expression in IBD IECs.

Freshly isolated IECs, used for the detection of CEACAM1, 5 and 6 mRNA, were further analyzed by Real-Time PCR for the expression of SOX9 mRNA (figure 3A). In contrast to the decrease in CEACAM transcripts noted before, SOX9 mRNA in IBD was comparable to normal controls. Therefore, there is no alteration in SOX9 gene expression in IBD.

Figure 3.

A. SOX9 mRNA expression in surface epithelial cells of Nor, CD, and UC colonic tissues. The IECs were isolated and the mRNA was purified and analyzed by Real-Time PCR. The fold increase in mRNA expression was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods section. B. Nor, CD and UC colonic tissue sections were immunostained using an anti-SOX9 antibody. The slides were counterstained with Mayer’s Hematoxylin solution and examined with a Zeiss Axioskop Light Microscope at 20x and 40x magnifications. These data are representative of 5 experiments.

To precisely localize SOX9 expression, we performed a series of histological analyses using paraffin sections from Nor, CD and UC colonic tissues (Figure 3B). In Nor controls, SOX9 expression along the crypt-surface axis was more evident in the cytoplasm with scattered nuclear staining. In CD, SOX9 was predominantly localized to the nucleus. SOX9 expression was greater in the lower two thirds of the crypt-surface axis in CD mucosa, whereas it was greater in the upper two thirds in UC. SOX9 expression extended from the crypt to the surface, exhibiting a significant nuclear and cytoplasmic pattern in association with active inflammation, especially in CD. These data suggest that this effect may be inflammation related.

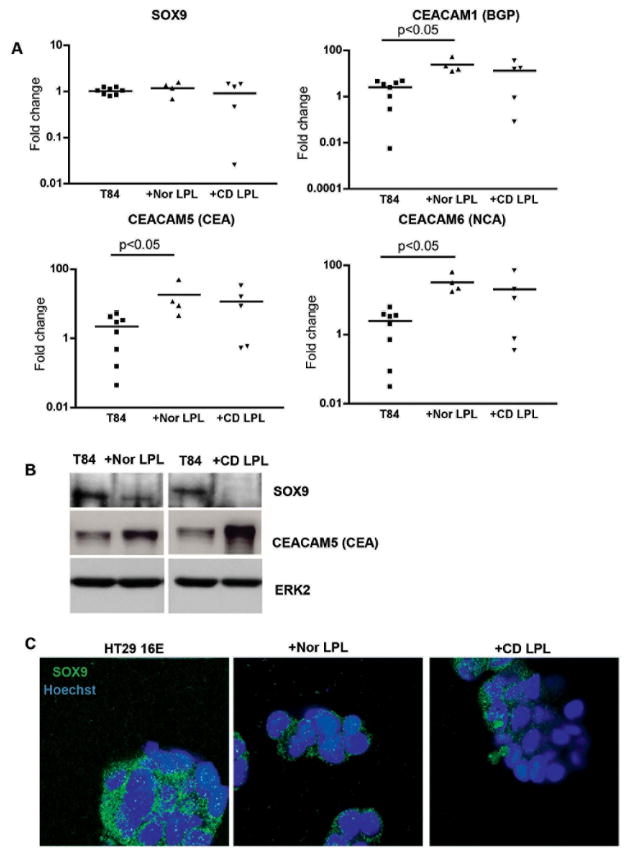

LPLs induce a reduction in cytoplasmic SOX9 in IEC lines

SOX9 expression is regulated by inflammatory cytokines inhibiting mesenchymal cell differentiation (30, 31). In these two studies, the authors introduced the concept that the regulation of SOX9, as a secondary effect of inflammation, may be responsible for tissue alterations in inflammatory diseases (e.g. suppression of the cartilage phenotype in inflammatory joint disease). It was also shown that CEACAM5 gene expression was inhibited when SOX9 translocated to the nucleus (18). We were wondering whether or not SOX9 localization could be affected in the setting of an inflammatory environment in IEC lines. The main source of inflammatory cytokines is the lymphocyte populations in the lamina propria. Based on our previous findings where we described that LPLs could elicit IEC differentiation in a contact dependent manner (25), we investigated the role of LPLs in SOX9 expression in IEC lines. We co-cultured T84 and HT29 16E cells with freshly isolated Nor or CD LPLs for 4 days and examined SOX9 mRNA by Real-Time PCR in T84 cells (Figure 4A). There was no significant difference between the groups. Similar results were obtained when HT29 16E cells were co-cultured with LPLs (data not shown). The results using UC LPL are not shown in this study, because these cells had a cytotoxic effect on the IEC lines at day 4.

Figure 4.

A. SOX9, CEACAM1, 5 and 6 mRNA expression in T84 cells co-cultured with Nor or CD LPL for 4 days. After removing the LPL, mRNA from T84 cells was purified and analyzed by Real Time-PCR. The fold increase in mRNA expression was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods section. B. Immunoblotting for SOX9, CEACAM5 and ERK2 in lysates obtained from T84 cells co-cultured with freshly isolated Nor or CD LPL for 4 days. These data are representative of 5 experiments. C. Immunoflurorescence staining for SOX9 (green) in HT29 16E cells co-cultured with Nor or CD LPL for 4 days. The nuclei were staining with Hoechst 33342 (blue). All the samples were analyzed with a Leica SP5-DM Confocal microscope at 100x magnification. These data are representative of 5 experiments.

The presence of LPLs did not influence the transcriptional level of SOX9 gene expression in IECs, consistent with the finding that there was no difference in SOX9 mRNA expression in Nor versus IBD IECs. We therefore measured SOX9 protein by WB. As seen in Figure 4B, the presence of Nor or CD LPLs decreased SOX9 protein in T84 cells at day 4 of co-culture. Western blotting using an antibody recognizing total ERK2 revealed the presence of comparable total protein in the analyzed samples. CD LPLs induced a greater decrease in SOX9 expression, possibly due to the fact that they are intrinsically more inflammatory. To confirm the nuclear translocation of SOX9 in the presence of the LPLs, we performed a series of anti-SOX9 immunofluorescence studies (Figure 4C). Interestingly, co-culture of LPLs with HT29 16E did not cause translocation of SOX9 to the nucleus. However, the cytoplasmic expression of SOX9 was diminished.

LPLs induce an increase in CEACAM family member expression in IEC lines

In order to correlate the decrease in cytoplasmic SOX9 in IEC lines with CEACAM family member expression, we co-cultured IEC lines with LPLs as above. As seen in Figure 4A, there was a significant increase in CEACAM 1, 5 and 6 mRNA expression in T84 cells co-cultured with Nor LPLs compared to T84 cells alone (24.5±9 versus 2.5±0.7 fold increase for CEACAM1, 18.2±10.2 versus 2.2±0.7 fold increase for CEACAM5, 32.7±10.2 versus 2.4±0.7 fold increase for CEACAM6; p<0.05). When IEC lines were co-cultured with CD LPL, we observed a similar but not significant trend. We therefore assessed the protein expression level of CEACAM5 by WB analysis (Figure 4B). The presence of LPLs increased CEACAM5 protein in T84 cells after 4 days of co-culture. Western blotting using an antibody recognizing total ERK2 revealed the presence of comparable total protein in the analyzed samples. Thus, CD LPLs induced a greater increase in CEACAM5 expression, possibly related to their inflammatory phenotype. However, in vivo, CD LPLs clearly do not affect CEACAM5 expression suggesting that the defects previously reported reflect abnormalities intrinsic to the IEC and not tot eh microenvironment.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies from our lab suggested that IECs function as APCs and, promote regulatory T-cell responses in the mucosa. Nor IECs activate CD8+ regulatory T cells (1, 2). This activation is restricted by the non classical class I molecule CD1d and a novel CD8 ligand, gp180. CD1d and gp180 form a complex on the surface of the IECs that allows CD1d to function in a class I-like manner: cross-linking the TcR with CD8 (32-34). Using B9, a monoclonal antibody directed against gp180, we documented the defective expression of this glycoprotein in IBD (13). This defect was associated with the inability of IBD IECs to activate CD8+ regulatory T cells. We have proposed that this subset of regulatory T cells helps to maintain normal gut homeostasis. B9 recognizes a common epitope in the N domain of several CEACAM family members (data not published). Thus, it is unclear which of the CEACAM family members is involved in the activation of CD8+ T cells.

In this study, we investigated the expression pattern of CEACAM1, 5 and 6 in human colonic mucosa. There are two different patterns of CEACAM family member expression in IBD IECs. In CD IECs, we showed a decrease in CEACAM family member mRNA supporting the concept that the reported defect was global and likely transcriptional. In UC IECs, CEACAM mRNA and protein levels were not affected, supporting a defect in post-transcriptional regulation.

The present and previous studies were restricted to colon IECs. It was recently reported that CEACAM6 is upregulated in the ileum of CD patients, and that this molecule acts as a receptor for adherent-invasive E. coli (35). The surrounding environment in the small bowel versus the large bowel is very different, especially with regard to commensal flora. This might explain the difference in the pattern of CEACAM family member expression in our study.

In colon cancer, CEACAM5 over-expression protects cells against apoptosis and contributes to carcinogenesis (16, 17). The transcription factor SOX9 can down-regulate CEACAM5 gene expression, and as a probable consequence, induce apoptosis in a human colon carcinoma cell line (18). Furthermore, CEACAM1, the only CEACAM family member expressed on mouse IECs, has been directly linked to SOX9 transcriptional activity (23).

While there was no difference in SOX9 mRNA expression in Nor vs. IBD IECs, we documented a different pattern of protein localization in IBD IECs. Indeed, SOX9 was clearly expressed in the nucleus of IBD IECs, especially in CD. In UC IECs, the nuclear localization of SOX9 was less striking, a finding consistent with the fact that the defect in CEACAM expression in UC is less likely to be transcriptionally regulated.

SOX9 expression is regulated by inflammatory cytokines inhibiting mesenchymal cell differentiation (30, 31). Moreover, CEACAM5 gene expression has been reported to be inhibited when SOX9 translocated to the nucleus (18). We investigated the pattern of SOX9 under influence of an inflammatory environment in IEC lines. The most important source of inflammatory cytokines within the lamina propria is the lymphocyte population. Given the fact that we previously described that LPLs could trigger and enhance IEC differentiation in a contact dependent manner (25), we decided to investigate the impact of LPLs on IECs in this actual context. When we co-cultured IEC lines with freshly isolated LPL, not only did we observe a decrease in cytosolic SOX9, but concomitantly, we demonstrated that LPLs could elicit an increase in CEACAM5 expression at a transcriptional level.

Our laboratory has shown that IECs may play an important role in regulating the immune responses toward luminal antigen. We described a specific subset of CD8+ T cells undergoes oligoclonal expansion in the intestinal mucosa, via their interaction with a unique complex expressed on IECs (CEACAM subfamily member (gp180) and CD1d). This subset, which has regulatory properties in vitro, may play a crucial role in the control of intestinal immune responses toward luminal antigens. We have also shown that IBD patients possess defects in CD1d and CEACAM subfamily member expression resulting in a decrease in these CD8+ Tregs in vivo (36) and that this defect correlates with an inability of these patients to be tolerized to orally administered antigens (37, 38). Furthermore, this defect correlates with SOX9 translocation to the IEC nucleus. Taken together, there are both intrinsic and extrinsic factors that affect the development of normal regulatory pathways in IBD. Understanding these pathways will lead to novel therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: This work was supported by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (LM and SD), the New York Crohn’s Foundation and NIH grants AI23504, DK58288, AI44236. The light microscopy was performed at the MSSM-Microscopy Shared Resource Facility, supported with funding from NIH-NCI shared resources grant (5R24 CA095823-04), NSF Major Research Instrumentation grant (DBI-9724504) and NIH shared instrumentation grant (1 S10 RR0 9145-01).

Abbreviations

- CEACAM

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule

- IECs

intestinal epithelial cells

- LPLs

lamina propria lymphocytes

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- Nor

normal

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- TCR

T cell antigen receptor

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Allez M, Brimnes J, Dotan I, et al. Expansion of CD8+ T cells with regulatory function after interaction with intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1516–1526. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allez M, Brimnes J, Shao L, et al. Activation of a unique population of CD8(+) T cells by intestinal epithelial cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1029:22–35. doi: 10.1196/annals.1309.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allez M, Mayer L. Regulatory T cells: peace keepers in the gut. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:666–676. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arosa FA, Irwin C, Mayer L, et al. Interactions between peripheral blood CD8 T lymphocytes and intestinal epithelial cells (iEC) Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:226–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Yio XY, Mayer L. Human intestinal epithelial cell-induced CD8+ T cell activation is mediated through CD8 and the activation of CD8-associated p56lck. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1079–1088. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer L. IBD: immunologic research at The Mount Sinai Hospital. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67:208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somnay-Wadgaonkar K, Nusrat A, Kim HS, et al. Immunolocalization of CD1d in human intestinal epithelial cells and identification of a beta2-microglobulin-associated form. Int Immunol. 1999;11:383–392. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Wal Y, Corazza N, Allez M, et al. Delineation of a CD1d-restricted antigen presentation pathway associated with human and mouse intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1420–1431. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yio XY, Mayer L. Characterization of a 180-kDa intestinal epithelial cell membrane glycoprotein, gp180. A candidate molecule mediating t cell-epithelial cell interactions. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12786–12792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray-Owen SD, Blumberg RS. CEACAM1: contact-dependent control of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:433–446. doi: 10.1038/nri1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frangsmyr L, Baranov V, Hammarstrom S. Four carcinoembryonic antigen subfamily members, CEA, NCA, BGP and CGM2, selectively expressed in the normal human colonic epithelium, are integral components of the fuzzy coat. Tumour Biol. 1999;20:277–292. doi: 10.1159/000030075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammarstrom S. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family: structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:67–81. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toy LS, Yio XY, Lin A, et al. Defective expression of gp180, a novel CD8 ligand on intestinal epithelial cells, in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2062–2071. doi: 10.1172/JCI119739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilantzis C, Jothy S, Alpert LC, et al. Cell-surface levels of human carcinoembryonic antigen are inversely correlated with colonocyte differentiation in colon carcinogenesis. Lab Invest. 1997;76:703–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Z, Deng X, Chen M, et al. Oncogenic c-Ki-ras but not oncogenic c-Ha-ras up-regulates CEA expression and disrupts basolateral polarity in colon epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27902–27907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ordonez C, Screaton RA, Ilantzis C, et al. Human carcinoembryonic antigen functions as a general inhibitor of anoikis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3419–3424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wirth T, Soeth E, Czubayko F, et al. Inhibition of endogenous carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) increases the apoptotic rate of colon cancer cells and inhibits metastatic tumor growth. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2002;19:155–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1014566127493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jay P, Berta P, Blache P. Expression of the carcinoembryonic antigen gene is inhibited by SOX9 in human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2193–2198. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefebvre V, de Crombrugghe B. Toward understanding SOX9 function in chondrocyte differentiation. Matrix Biol. 1998;16:529–540. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soullier S, Jay P, Poulat F, et al. Diversification pattern of the HMG and SOX family members during evolution. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:517–527. doi: 10.1007/pl00006495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bastide P, Darido C, Pannequin J, et al. Sox9 regulates cell proliferation and is required for Paneth cell differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:635–648. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mori-Akiyama Y, van den Born M, van Es JH, et al. SOX9 is required for the differentiation of paneth cells in the intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:539–546. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zalzali H, Naudin C, Bastide P, et al. CEACAM1, a SOX9 direct transcriptional target identified in the colon epithelium. Oncogene. 2008;27:7131–7138. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blache P, van de Wetering M, Duluc I, et al. SOX9 is an intestine crypt transcription factor, is regulated by the Wnt pathway, and represses the CDX2 and MUC2 genes. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:37–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahan S, Roda G, Pinn D, et al. Epithelial: lamina propria lymphocyte interactions promote epithelial cell differentiation. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:192–203. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walters JR. Recent findings in the cell and molecular biology of the small intestine. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:135–140. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000153309.13080.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer L, Shlien R. Evidence for function of Ia molecules on gut epithelial cells in man. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1471–1483. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Augeron C, Laboisse CL. Emergence of permanently differentiated cell clones in a human colonic cancer cell line in culture after treatment with sodium butyrate. Cancer Res. 1984;44:3961–3969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuen T, Zhang W, Ebersole BJ, et al. Monitoring G-protein-coupled receptor signaling with DNA microarrays and real-time polymerase chain reaction. Methods Enzymol. 2002;345:556–569. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)45047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami S, Lefebvre V, de Crombrugghe B. Potent inhibition of the master chondrogenic factor Sox9 gene by interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3687–3692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sitcheran R, Cogswell PC, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-kappaB mediates inhibition of mesenchymal cell differentiation through a posttranscriptional gene silencing mechanism. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2368–2373. doi: 10.1101/gad.1114503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell N, Yio XY, So LP, et al. The intestinal epithelial cell: processing and presentation of antigen to the mucosal immune system. Immunol Rev. 1999;172:315–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell NA, Kim HS, Blumberg RS, et al. The nonclassical class I molecule CD1d associates with the novel CD8 ligand gp180 on intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26259–26265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell NA, Park MS, Toy LS, et al. A non-class I MHC intestinal epithelial surface glycoprotein, gp180, binds to CD8. Clin Immunol. 2002;102:267–274. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnich N, Carvalho FA, Glasser AL, et al. CEACAM6 acts as a receptor for adherent-invasive E. coli, supporting ileal mucosa colonization in Crohn disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1566–1574. doi: 10.1172/JCI30504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brimnes J, Allez M, Dotan I, et al. Defects in CD8+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol. 2005;174:5814–5822. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraus TA, Toy L, Chan L, et al. Failure to induce oral tolerance in Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis patients: possible genetic risk. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1029:225–238. doi: 10.1196/annals.1309.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraus TA, Toy L, Chan L, et al. Failure to induce oral tolerance to a soluble protein in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1771–1778. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]