Abstract

Lysozyme (Lys) plays crucial roles in the innate immune system, and the detection of Lys in urine and serum has considerable clinical importance. Traditionally, the presence of Lys has been detected by immunoassays; however, these assays are limited by the availability of commercial antibodies and tedious protein modification, and prior sample purification. To address these limitations, we report here the design, synthesis and application of a competition-mediated pyrene-switching aptasensor for selective detection of Lys in buffer and human serum. The detection strategy is based on the attachment of pyrene molecules to both ends of a hairpin DNA strand, which becomes the partially complementary competitor to an anti-Lys aptamer. In the presence of target Lys, the aptamer hybridizes with part of the competitor, which opens the hairpin such that both pyrene molecules are spatially separated. In the presence of target Lys, however, the competitor is displaced from the aptamer by the target, subsequently forming an initial hairpin structure. This brings the two pyrene moieties into close proximity to generate an excimer, which, in turn, results in a shift of fluorescence emission from ca. 400 nm (pyrene monomer) to 495 nm (pyrene excimer). The proposed method for Lys detection showed sensitivity as low as 200 pM and high selectivity in buffer. When measured by steady-state fluorescence spectrum, the detection of Lys in human serum showed a strong fluorescent background, which obscured detection of the excimer signal. However, time-resolved emission measurement (TREM) supported the potential of the method in complex environments with background fluorescence by demonstrating the temporal separation of probe fluorescence emission decay from the intense background signal. We have also demonstrated that the same strategy can be applied to the detection of small biomolecules such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), sowing the generality of our approach. Therefore, the competition-mediated pyrene-switching aptasensor is promising to have potential for clinical and forensic applications.

Lysozyme (Lys) is the ubiquitous enzyme of innate immune system, that hydrolyzes the polysaccharide wall of bacteria and it is widely distributed in body tissues and secretions. Its primary sequence contains 129 amino acids, with a high isoelectric point (pI) value of 11.0. It has been discovered that increased Lys concentration in urine and serum is associated with leukemia,1 renal disease,2 and meningitis.3 Therefore, lysozyme detection is of considerable importance. Traditionally, the analysis of Lys has been accomplished by separation techniques such as polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)4 and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC),5 as well as immunoassays, including immunoelectrophoresis (IEP)6 and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).7 Despite their high sensitivity, immunoassays require tedious protein modification, and they are limited by the availability of commercial antibodies.

In place of commercial antibodies, the use of aptamers as the recognition elements may be an alternative strategy. aptamers are single-stranded oligonucleotides selected to bind essentially any molecular targets with high selectivity and affinity through an in vitro selection process called SELEX (selective evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment). 8-10 Aptamer sequences are easy to synthesize and modify, and they are more stable than antibodies under a wide range of conditions.11 Recently, an anti-Lys aptamer, which shows high affinity for Lys with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 31 nM,12 has been developed as a biosensor for the detection of Lys based on different detection techniques (Table 1).13-21 However, detection of Lys in its native environments is still a challenging task. Previous work in our group has shown that pyrene dual-labeled aptamer probes hold great potential for protein analysis in complex biological fluids.22 Yet that work has its own limitations: First, even slight modifications of aptamers would often lead to significant loss of the affinity and specificity toward targets.23, 24 Second, only those aptamers which can bring both ends into close proximity upon binding to the target, can be used in this strategy.

Table 1.

Summary of Aptamer-Based Lysozyme Sensors

| Method | Signal Output | Detection Limit |

|---|---|---|

| [Ru(NH3)6]3+-probe voltammetry13 | electrochemical | 35 nM |

| GNP-[Ru(NH3)6]3+-probe voltammetry14 | electrochemical | 700 pM |

| [Fe(CN)6]3--probe impendance15 | electrochemical | 14 nM |

| DNA-based electrooxidation16 | electrochemical | 18 nM |

| Aptamer-DNAzyme hairpins17 | absorbance | 0.5 pM |

| DNAzyme-aptamer conjugates18 | absorbance | 0.1 pM |

| CPE-aptamer-SiNP19 | fluorescence | 25 nM |

| Bead-based aptasensor20 | fluorescence | / |

| Perylene-probe aggregation21 | fluorescence | 70 pM |

| Competition-mediated pyrene-switching aptasensor | fluorescence | 200 pM |

GNP: Gold Nanopaticle; SiNP: Silica Nanoparticles; CPE: Conjugated Polyelectrolyte; the concentration was converted into a nanomolar or picomolar value for straightforward comparison (1 μg/mL = 70 nM for Lys).

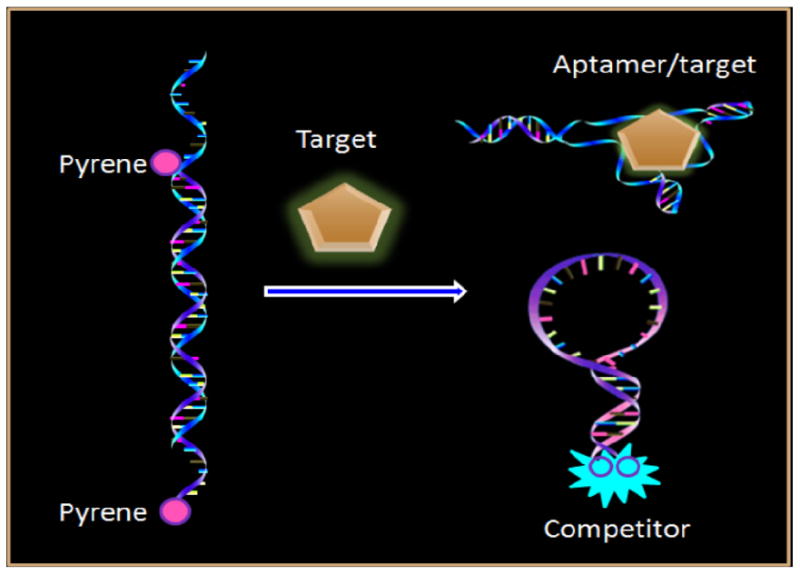

To address these challenges, we have molecularly engineered a competition-mediated pyrene-switching aptasensor for Lys detection in pure buffer or human serum using both steady-state and time-resolved measurement. Our approach involves two DNA strands, one is Lys aptamer and another one is a dual-pyrene-labeled hairpin sequence (competitor), which is partially complementary to the anti-Lys aptamer. In the absence of target Lys, the aptamer hybridizes with part of the competitor. As a result, the DNA hairpin opens, and both pyrene molecules are spatially separated. However, in the presence of the target Lys, the competitor is displaced from the aptamer by the target, subsequently forming an initial hairpin structure. This brings the two pyrene moieties into close proximity to form an excimer, which, in turn, results in a significant shift of fluorescence emission from ca. 400 nm (pyrene monomer) to 495 nm (pyrene excimer). Meanwhile, with time-resolved emission measurements (TREM), the pyrene excimer signal (tens to hundreds of ns) can be separated from biological background interference (mostly < 5 ns).22, 25

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

The sequences of prepared DNA oligonucleotides are listed in Table 2. DNA synthesis reagents were purchased from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). The succinimidyl ester of 1-pyrenebutanoic acid was purchased from Molecular Probes (Oregon, USA). A solution of 0.1 M triethylamine acetate (pH 6.5) was used as HPLC buffer A, and HPLC-grade acetonitrile (Fisher) was used as HPLC buffer B. The ATP, GTP, CTP, bovine serum albumin (BSA), human IgG and lysozyme were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Human α-thrombin was purchased from Haematologic Technologies Inc. (HTI).

Table 2.

Probes and oligonucleotides used in Lys binding study

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Competitor 1 | 5’-Py-(CH2)6-ATCAGGGCTTTAGCCCTGAT-(CH2)6-Py-3’ |

| Competitor 2 | 5’-Py-(CH2)6-ATCAGGGCTCTTTAGCCCTGAT-(CH2)6-Py-3’ |

| Competitor 3 | 5’-Py-(CH2)6-ATCAGGGCACTCTTTAGCCCTGAT-(CH2)6-Py-3’ |

| Competitor 4 | 5’-Py-(CH2)6-ATCAGGGCGCACTCTTTAGCCCTGAT-(CH2)6-Py-3’ |

| Anti-Lys aptamer | 5’-ATCAGGGCTAAAGAGTGCAGAGTTACTTAG-3’ |

Boldface type indicates the bases that form a stem after the aptamer binds to the protein Lys.

Instruments

An ABI 3400 DNA/RNA synthesizer (Applied Bio-Systems) was used for DNA synthesis. Probe purification was performed with a ProStar HPLC (Varian) equipped with a C18 column (Econosil, 5U, 250 × 4.6 mm) from Alltech Associates. UV-Vis measurements were performed with a Cary Bio-100 UV/Vis spectrometer (Varian) for probe quantification. Steady-state fluorescence measurements were performed on a Fluorolog-Tau-3 spectrofluorometer (Jobin Yvon, Edison, NJ). Time-resolved measurements were made on a Fluo Time 100-Compact Fluorescence lifetime spectrometer (PicoQuant, Germany).

Synthesis and Purification

Amine-modified DNA probe was synthesized using standard phosphoramidite chemistry and probes were purified using reversed phase HPLC (Figure S1 in Supporting Information). The purified DNAs were conjugated with the pyrene at the amino end by 5h incubation in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate/sodium carbonate buffer (pH 8.5) mixed with a 15-fold excess of the succinimidyl ester of 1-pyrene butanoic acid dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The unconjugated pyrene was removed by ethanol precipitation of DNA, repeated three times. The resulting crude mixture was separated by HPLC using a linear elution gradient with buffer B changing from 25% to 75% in 25min at a flow rate of 1mL/min. The last peak in chromatography that absorbed at 260 and 340 nm was collected as the product. The collected product was then vacuum-dried, desalted with an NAP™ 5 column (GE, Healthcare), and stored at -20 °C for future use.

Pretreatment of Human Serum

Human serum sample (Asterand), which was diluted to 50% by buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), was loaded into a centrifugal filtration device (10000 Da cutoff) and subjected to centrifugation (10000 rpm, 20 min).

Fluorescence Measurements

Before adding the target molecules for Lys detection, aptamers/competitors were diluted to 200 nM in buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and heated at 65 °C for 5 min. For the ATP assay, aptamers/competitors were diluted to 200 nM in buffer (300 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0) and heated at 65 °C for 5 min, followed by the addition of targets. The solutions were incubated at 25 °C for 30 min before fluorescence measurements with excitation at 340 nm. Time-resolved measurements were made with the Compact Fluorescence lifetime spectrometer (Fluo Time 100), where a pulsed diode laser (PDL 800-B) was used as the excitation source (λ = 355 nm) and photon counting instrumentation (PicoHarp 300) was used as a readout.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Working Principle of Competition-Based Pyrene-Switching Aptasensor

Some spatially sensitive fluorescent dyes, such as pyrene26-29 and BODIPY FL,30, 31 can form an excimer when an excited-state molecule is brought into close proximity with another ground-state molecule. The excimer formation results in a shift of the emission to a longer wavelength than that of the monomer. The formation of an excimer between two pyrene molecules connected by a flexible covalent chain, such as DNA, is very useful for probing spatial arrangements. Similar to FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer), the stringent distance-dependent property of excimer formation can be used as a unique signal transduction in the development of molecular probes.22, 32, 33, 34

The principle of our Lys detection method is shown in Figure 1. Pyrene molecules are attached to both ends of a hairpin DNA strand, which becomes the partially complementary competitor to an incorporated aptamer. In the absence of a target, the aptamer hybridizes with part of the competitor. As a consequence, two pyrene molecules are spatially separated, and only the monomer emission peaks (388 nm and 408 nm) can be observed. However, in the presence of a target, the competitor is gradually displaced from the aptamer by the target, subsequently forming a hairpin structure. This brings the two pyrene moieties into close proximity and allows the formation of an excimer that emits at 495 nm. The emission ratio (excimer/monomer) can be used as a signal for highly sensitive quantitation of Lys in homogeneous solutions.

Figure 1.

Working principle of competition-mediated pyrene-switching atasensor for aptamer/target binding assay.

Design of the Pyrene Dual-Labeled Competitor

To achieve the maximal signal desired, our design relies upon the competition among three events: aptamer/target binding, aptamer/competitor hybridization, and competitor self-hybridization. As seen in Figure1, in the absence of a target, aptamer and competitor form a duplex inducing the pyrene at two ends of the competitor to separate. In this state, the competitor needed a loop long enough to ensure that aptamer/competitor hybridization affinity would be stronger than the competitor self-hybridization. Otherwise, if the loop of the competitor is too long, aptamer/target binding in the presence of a target would be restricted. Hence the loop length of the competitor is critical to our design. An 8-bp-long stem was developed to make certain that the hairpin structure would resume once aptamer/target binding had occurred. In order to open a hairpin structure with such a long stem, a ‘shared-stem’35 mode was also designed, i.e. besides the loop region, eight bases of the stem at the 3’-end is complementary to the aptamer (Table 2). Four different lengths of competitor (Competitor1-4 in Table 2) were synthesized and compared by steady-state fluorescence measurements. The results showed that competitor 3, which contains an 8-bp-long stem and an 8-nt-long loop, had the maximal signal change after adding target (Figure S2 in Supporting Information). Therefore, competitor 3 was selected for use in the subsequent experiments.

Kinetics and Thermodynamic Studies

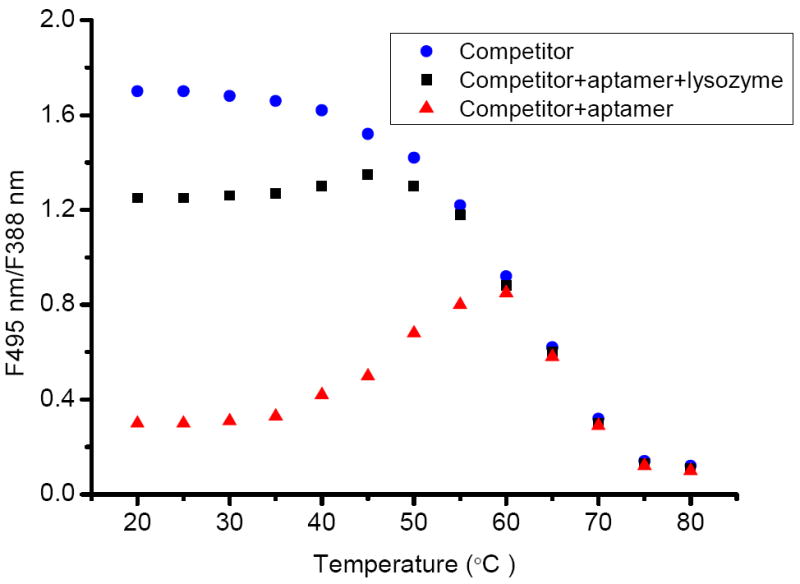

We investigated the thermodynamics of the method by monitoring the fluorescence intensity ratio (F495nm/F388nm) change over a temperature profile (Figure 2). For the competitor only (blue dots), the sequence is held in the “close” state with maximal excimer fluorescence at low temperature. Then the signal is gradually turned off along with the temperature elevation, resulted in the thermal destabilization of the stem-loop structure that separates the two pyrene moieties at both ends. For the competitor/aptamer (red triangle), minimal excimer fluorescence is initially detected at low temperature as a result of forming a competitor/aptamer duplex and opening the hairpin stem. When the temperature exceeds 40 °C, the duplex is dehybridized, and reformation of the hairpin holds the two pyrenes in close proximity, which leads to an increase of excimer signal. When the temperature rises, the signal decreases again because the stem-loop structure melts into extended random coils over 60 °C. The behavior of the competitor/aptamer/lysozyme (black square), is similar to that of the competitor only, meaning that the competitor is free throughout the formation of the aptamer/lysozyme complex.

Figure 2.

Thermodynamic studies of competitor (blue), competitor/aptamer (red) and competitor/aptamer/lysozyme (black). 200 nM each in buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4)

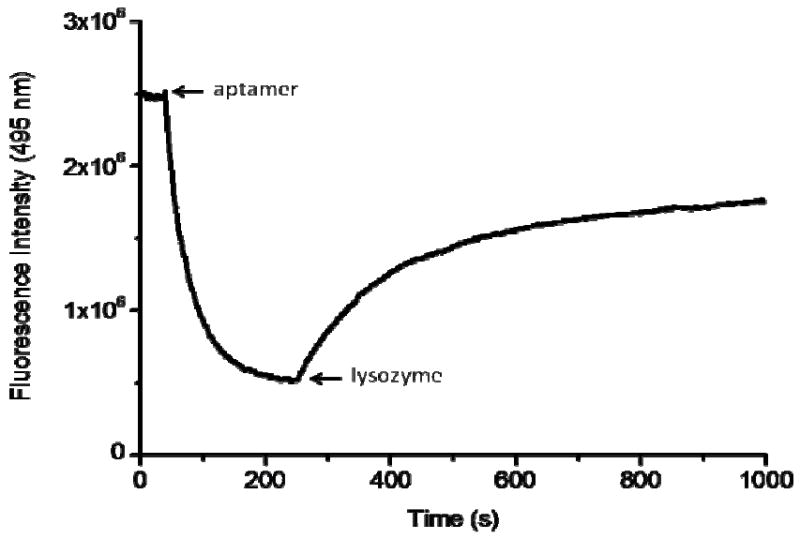

The kinetics of the method was also studied (Figure 3). Competitors stay in the “close” state and emit an excimer signal (495 nm) until they meet the aptamer which can open the hairpin structure. Indeed, once the aptamer was added, the duplex of competitor/aptamer was formed rapidly and achieved equilibrium within 3 min with the excimer signal decreasing. Finally, introduction of lysozyme to the solution results in an increase of the eximer signal as a result of reformation of the hairpin structure of the competitor, which brings the two pyrenes into close proximity.

Figure 3.

Kinetics study of the 200 nM competitor in buffer followed by adding 200 nM aptamer, and then 200 nM lysozyme at room temperature (25 °C).

Quantitative Detection of Lysozyme in Pure Buffer

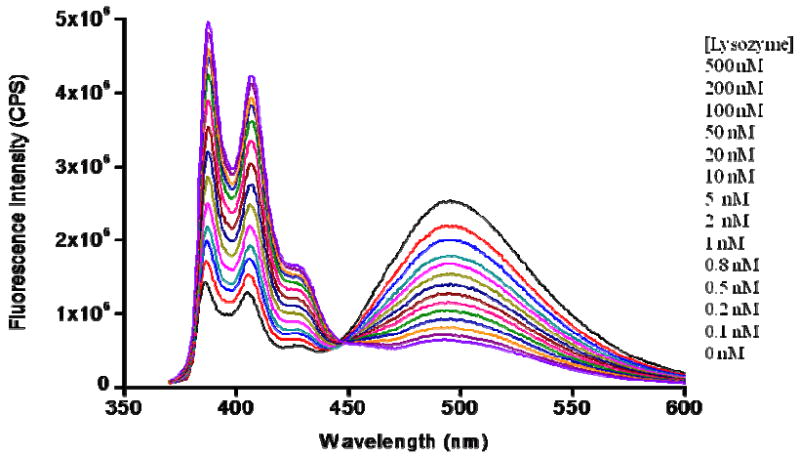

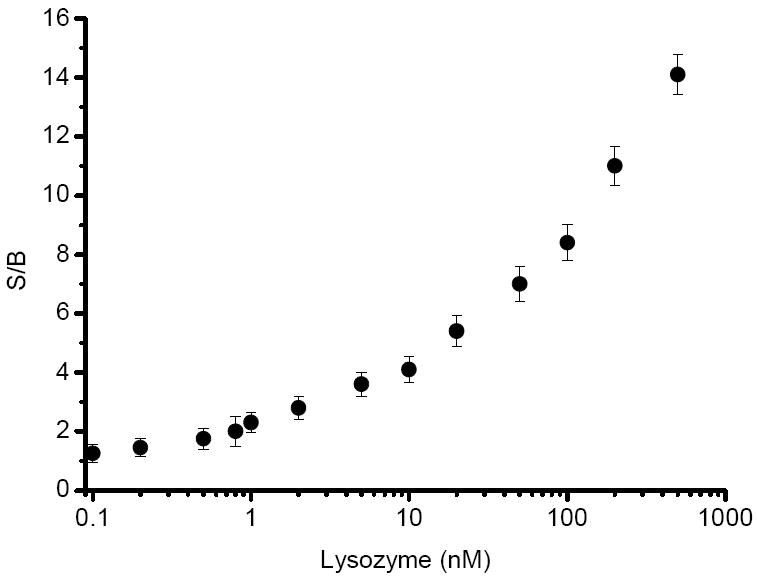

A pyrene dual-labeled competitor 3 and anti-Lys aptamer (sequence shown in Table 2) were prepared. To fully hybridize each other, 200 nM each of competitor 3 and anti-Lys aptamer were annealed, after which different concentrations of Lys were added to the solution, which was scanned by fluorometer with excitation at 340 nm after 0.5 h incubation. Upon addition of Lys into the solution, an aptamer/target complex was formed, allowing the competitor to freely self-hybridize with the pyrenes at 5’-end and 3’-end close to each other. The amount of target is proportional to the number of free competitors. In other words, with increasing amounts of target protein in the solution, the excimer intensity increased proportionally. Data shown in Figure 4 reveals that the excimer peak increases and two monomer peaks decrease with the increase of Lys concentration. The light-switching phenomenon allows ratiometric measurement. Therefore, by taking the intensity ratio of the excimer peak to either one of the monomer peaks, we could effectively eliminate signal fluctuation and minimize the impact of environmental quenching on the accuracy of the measurement.22 In order to eliminate the background signal, we defined signal to background ratio (S/B) by using the following equation:35, 36, 37

| (1) |

where the terms of (F495 nm/F388 nm) with target and (F495 nm/F388 nm) no target take into account the ratios of excimer fluorescence intensity to monomer fluorescence intensity of pyrene with and without target, respectively. As seen in Figure 5, it is easy to attain the S/B corresponding to the given target protein concentration. The sensitivity of the method for Lys quantitative detection can reach as low as 200 pM, which is comparable with most of the reported methods (Table 1). It can adequately satisfy the clinical requirement, in which the concentration of serum lysozyme is μg/mL (1 μg/mL = 70 nM) level.38-40

Figure 4.

Detection of Lys in homogeneous solution by steady-state fluorescence. 200 nM aptamer/competitor response to different concentrations of Lys in buffer (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) at 25 °C. With increase of Lys concentrations from 0 to 1000 μM, the excimer peak (495 nm) increases and the monomer peaks (388 nm and 408 nm) decrease.

Figure 5.

The response of fluorescence intensity ratio to the change of target Lys concentration.

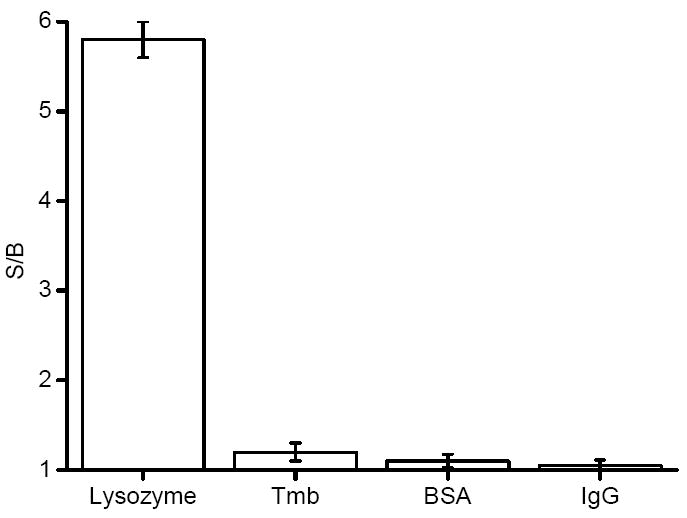

Selectivity of the Detection System

To detect Lys in human serum, the detection system has to selectively respond only to Lys, free from interference from other chemicals, especially proteins in the test sample. We chose some typical proteins in human serum, such as human α-thrombin (Tmb), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and human Immunoglobulin G (IgG). The results clearly showed that this method was highly selective for Lys (Figure 6). The anti-Lys aptamer sequence is intrinsically high specificity, but the results also derive from the stringent requirement for pyrene excimer formation, essentially because the two pyrene molecules have to be in very close proximity to each other (<0.5 nm) to give signal.41 This feature is an additional advantage for this detection system.

Figure 6.

Responses of the probes to lysozyme, Tmb, BSA, and IgG, respectively. Probes = (competitor/aptamer), [probes] = 200 nM, [each analyte] = 20 nM.

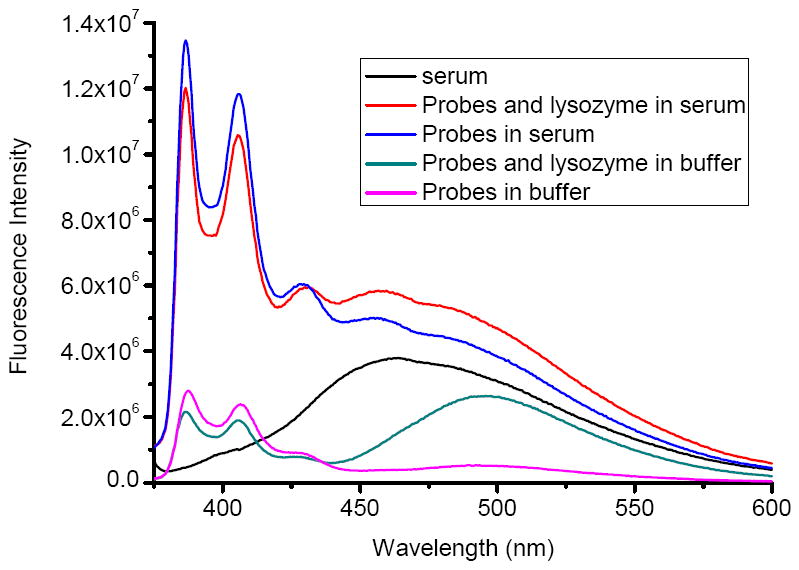

Direct Quantitative Detection of Lys in Human Serum

The method even showed good sensitivity and selectivity in pure buffer, but to be more useful in bioassay, the detection system should be able to tolerate any interference from real biological samples. Therefore, pretreated human serum was used to investigate its feasibility in biological samples.

Figure 7 shows the spectra of the probes (competitor/aptamer) in buffer solution and in human serum. In the buffer, the probe functioned well, with strong excimer emission was when target protein added. Unfortunately, in human serum, intense background fluorescence buried the signal response from the probe, making the probe signal indistinguishable from the indigenous background fluorescence. This result indicates that steady-state fluorescence measurement is not feasible for direct detection of Lys in complex biological samples.

Figure 7.

Investigating functions of the probes by steady-state fluorescence spectra in buffer and in serum, respectively. Probes = (competitor/aptamer), [probes] = 200 nM, [Lys] = 100 nM.

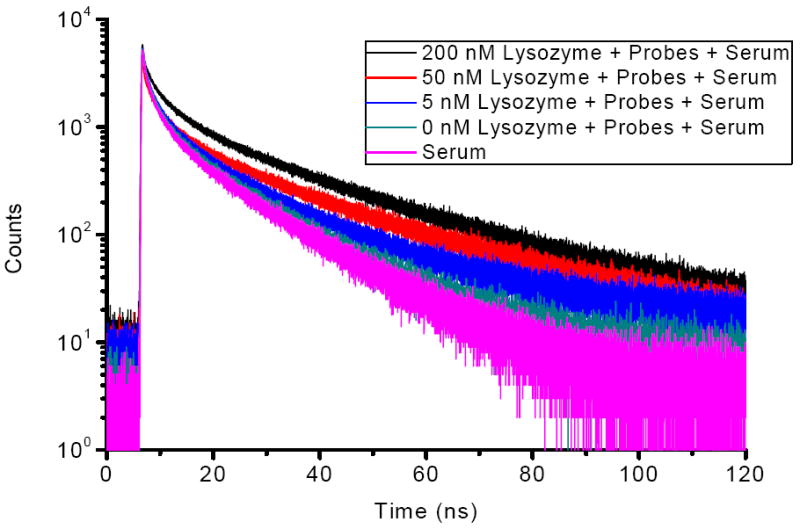

The monomer and excimer emissions of pyrene have much longer lifetime than most of the background fluorescent lifetime.22, 25 Such a large difference suggests that we could differentiate the probe signal from background by using time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy. With pulsed excitation, all chromophores, including pyrene and the fluoregenic molecules of serum, are excited. The time-correlated single photon counting technique was used to statistically measure the fluorescence emission decay. 42 If a population of molecules is instantaneously excited when photons are absorbed, then both the excited population and the fluorescence intensity, as a function of time I(t), gradually decay to the ground state. Decay Kinetics can be described by

| (2) |

where α is the intensity at time t = 0, t is the time after the absorption, and τ is the lifetime, which is the average time a molecule stays in its excited state prior to return to the ground state. This law of fluorescence decay implies that all excited molecules exist in a homogeneous environment, as is true for many single exponential fluorescence lifetime standards in solution. Thus, for our Lys assay in human serum, the decay kinetics should be described by

| (3) |

where α1 is the background fluorescence intensity at time t = 0, τ1 is the lifetime of background; α2 is the pyrene fluorescence intensity at time t = 0 and τ2 is the lifetime of pyrene.

Figure 8 shows the fluorescence decays (495 nm) of the 200 nM probes in human serum with various concentrations of Lys. It revealed a temporal separation of the probe signal from background noise. Equation (3) was used to fit the curve in Figure 8, and both τ1 and τ2 were calculated (Table S1 in Supporting Information). The background signal decayed within the first few nanoseconds after a short excitation pulse, and the remaining fluorescence after 10 ns should correspond to the long-lived pyrene fluorescence. Thus, photons emitted between 20 and 120 ns (because of the good separation from background fluorescence) were counted and integrated for each concentration to construct a calibration curve. The resulting photon counts were proportional to the Lys concentrations (Figure S3 in supporting Information). This linear response of counts to Lys in human serum demonstrated the feasibility of direct quantification of target protein in complex biological environment without any separation or purification. The detection limit of the method in human serum is about 5 nM, which still be able to satisfy the clinical requirement adequately.38-40

Figure 8.

Fluorescence decays (495 nm) of 200 nM probes in serum with various concentrations of Lys at excitation of 355 nm. Probes = (competitor/aptamer).

Generality of the Strategy

Since no sequence modification of aptamer is required and the hairpin competitor can be easily designed according to the aptamer sequence, we anticipated it to be a general strategy. To demonstrate that, the same principle was used to detect a small biomolecule, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is an important substrate in biological reaction. Since the binding affinity of ATP aptamer/ATP is relatively weak, the Kd is only 6 μM43 (sequence is shown in Table S2 in Supporting Information). The results showed effective response to different concentrations of ATP in buffer solution (Figure S4 in Supporting Information). Also, good sensitivity (LOD = 0.5 μM) and selectivity were demonstrated (Figure S5 and S6 in Supporting Information). The success of Lys and ATP detection, which represents a micro-biomolecule and a small biomolecule, respectively, unequivocally supports the feasibility and versatility of the competition-mediated pyrene-switching aptasensor.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, a competition-mediated pyrene-switching aptasensor for a target detection system was designed and tested. Lys and ATP were used as targets to prove its feasibility and versatility. As in other pyrene probes, the near-UV excitation (~340 nm) might be unfavorable for in vivo detection for a variety of reasons, including possible damage to cells. Nonetheless, this approach offers high selectivity and excellent sensitivity in buffer solution. More importantly, however, it can also be applied in complex biological samples (e. g. human serum) by using time-resolved measurement. The following five virtues of this novel detection system were proved in our demonstration: (1) By separating the molecular recognition element and signal transduction element, the label-free aptamer can preserve its original affinity and specificity. 44, 45 (2) The signal transduction of wavelength switching could effectively eliminate signal fluctuation and minimize the impact of environmental quenching on the accuracy of the measurement.22, 32 (3) The detection-without-separation method eliminates tedious washing and separating procedures and allows real-time monitoring. (4) The lifetime-based measurement holds promising potential applications in real biological samples.22, 25, 46 (5) Our competition-mediated pyrene-switching aptasensor is a universal strategy which can be extended to other DNA/RNA aptamers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Kathryn R. Williams for constructive discussions and manuscript review, and Dongpin Xie for help with fluorescence lifetime measurements. We also thank the NIH for funding and support. J.H. received financial support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE The route of synthesis and purification of pyrene-DNA-pyrene conjugates; competitor optimization data, fluorescence lifetime of probes with different concentrations of Lys in human serum; sequence used for ATP detection; detection of ATP in homogeneous solution by steady-state fluorescence; calibration curve of ATP assay; and selectivity of the method for ATP. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Levinson SS, Elin RJ, Yam L. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1131–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison JF, Lunt GS, Scott P, Blainey JD. Lancet. 1968;1:371–375. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)91350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klockars M, Reitamo S, Weber T, Kerttula Y. Acta Med Scand. 1978;203:71–74. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1978.tb14834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weth F, Schroeder T, Buxtorf UPZ. lebensm-Unters-Forsch. 1988;187:541–545. doi: 10.1007/BF01042386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao YH, Brown MB, Martin GP. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2001;53:549–554. doi: 10.1211/0022357011775668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson BG, Malmquist J. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1971;27:255–261. doi: 10.3109/00365517109080216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor DC, Cripps AW, Clancy RL. J Immunol Methods. 1992;146:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellington AD, Szostak JW. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson DL, Joyce GF. Nature. 1990;344:467–468. doi: 10.1038/344467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuerk C, Gold L. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayasena SD. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1628–1650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox JC, Ellington AD. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:2525–2531. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng AKH, Ge B, Yu HZ. Anal Chem. 2007;79:5158–5164. doi: 10.1021/ac062214q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng C, Chen J, Nie L, Nie Z, Yao S. Anal Chem. 2009;81:9972–9978. doi: 10.1021/ac901727z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez MC, Kawde AN, Wang J. Chem Commun. 2005:4267–4269. doi: 10.1039/b506571b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez MC, Rivas GA. Talanta. 2009;78:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teller C, Shimron S, Willner I. Anal Chem. 2009;81:9114–9119. doi: 10.1021/ac901773b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D, Shlyahovsky B, Elbaz J, Willner I. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5804–5805. doi: 10.1021/ja070180d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Pu KY, Liu B. Langmuir. 2010;26(12):10025–10030. doi: 10.1021/la100139p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirby R, Cho EJ, Gehrke B, Bayer T, Park YS, Neikirk DP, McDevitt JT, Ellington AD. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4066–4075. doi: 10.1021/ac049858n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang B, Yu C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:1485–1488. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang CJ, Jockusch S, Vicens M, Turro NJ, Tan W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17278–17283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508821102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jhaveri S, Rajendran M, Ellington AD. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:1293–1297. doi: 10.1038/82414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beyer S, Dittmer WU, Simmel FC. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2005;1:96–101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin AA, Li X, Jockusch S, Li Z, Raveendra B, Kalachikov S, Russo JJ, Morozova I, Puthanveettil SV, Ju J, Turro N. J Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3161–3168. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujimoto K, Shimizu H, Inouye M. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3271–3275. doi: 10.1021/jo049824f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birks JB. Photophysics of Aromatic Molecules. Whiley-Interscience; London: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winnik FM. Chem Rev. 1993;93:587–614. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescent Spectroscopy. Kluwer Academic/plenum; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dahim M, Mizuno NK, Li XM, Momsen WE, Momsen MM, Brokman HL. Biophys J. 2002;83:1511–1524. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73921-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pagano RE, Martin OC, Kang HC, Haugland RP. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:1267–1279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.6.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Yang CJ, Wu Y, Conlon P, Kim Y, Lin H, Tan W. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:355–359. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagatoishi S, Nojima T, Juskowiak B, Takenaka S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:5067–5070. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freeman Ronit, Li Yang, Tel-Vered R, Sharon E, Elbaz J, Willner I. Analyst. 2009;134:653–656. doi: 10.1039/b822836c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsourkas A, Behlkel MA, Bao G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4208–4215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marras SAE, Kramer FR, Tyagi S. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;212:111–128. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-327-5:111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng J, Li J, Gao X, Jin J, Wang K, Tan W, Yang R. Anal Chem. 2010;82:3914–3921. doi: 10.1021/ac1004713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lodha SC. Tubercle. 1980;61:81–85. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(80)90014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porstmann B, Jung K, Schmechta H, Evers U, Pergande M, Porstmann T, Kramm HJ, Krause H. Clin Biochem. 1989;22:349–355. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(89)80031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Near KA, Lefford MJ. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1105–1110. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1105-1110.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masuko M, Ohtani H, Ebata K, Shimadzu A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5409–5416. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.23.5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt W. Optical Spectroscopy in Chemistry and Life Sciences. WILEY-VCH; Germany: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huizenga DE, Szostak JW. Biochemistry. 1995;34:656–665. doi: 10.1021/bi00002a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li N, Ho C-M. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2380–2381. doi: 10.1021/ja076787b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li T, Fu R, Park HG. Chem Commun. 2010;46:3271–3273. doi: 10.1039/b923462d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Conlon P, Yang CJ, Wu Y, Chen Y, Martinez K, Kim Y, Stevens N, Marti AA, Jockusch S, Turro NJ, Tan W. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:336–342. doi: 10.1021/ja076411y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.