Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is a major target in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). In addition to ACE, ACE2 – which is a homolog of ACE and promotes the degradation of angiotensin II (AngII) to Ang (1–7) – has been recognized recently as a potential therapeutic target in the management of CVDs. This article reviews different metabolic pathways of ACE and ACE2 (AngI-AngII-AT1 receptors and AngI-Ang (1–7)-Mas receptors) in the regulation of cardiovascular function and their potential in new drug development in the therapy of CVDs. In addition, recent progress in the study of angiotensin and ACE in fetal origins of cardiovascular disease, which might present an interesting field in perinatal medicine and preventive medicine, is briefly summarized.

Introduction

It has been well established that the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) is an important regulator of cardiovascular function and has a pivotal role in the pathophysiological development of various cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). In addition to the systematic RAS, many tissues in the body, including the brain, contain their own local RAS [1].

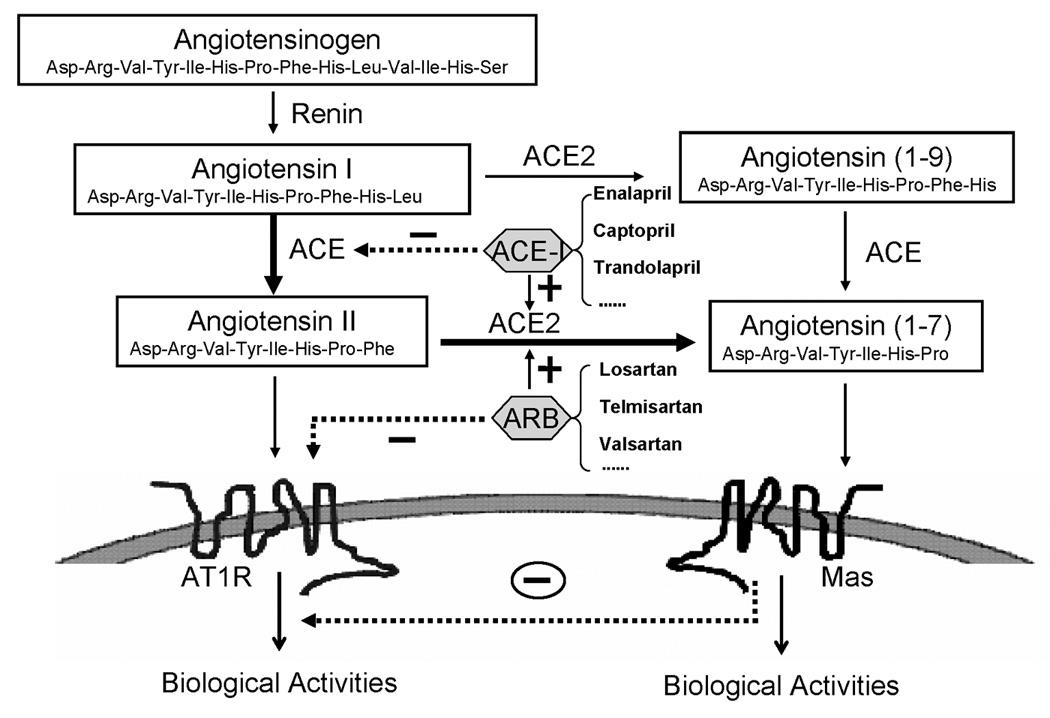

Classically, the substrate of RAS – angiotensinogen (AGT), a glycoprotein – is cleaved by renin to generate decapeptide angiotensin (Ang) I. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE; peptidyl dipeptidase A; EC 3.4.15.1) is a membrane-bound metalloprotease that converts Ang I to octapeptide Ang II (Figure 1). Ang II is the most active known peptide of the RAS and acts on various tissues in the body via selective binding to two major subtypes of G-protein-coupled receptors: Ang II type 1 (AT1R) and type 2 (AT2R) receptors [1,2]. Although other types of Ang II receptors, such as AT4R, have been identified in some tissues, most of the ‘classical’ actions of Ang II in the regulation of blood pressure (BP) and blood volume, as well as body fluid balance, are mediated by AT1R [3]. AT2R seems to have an important functional role in development [4]. AT2R-mediated actions have been suggested to counteract both short- and long-term effects of AT1R, such as vasoconstriction and cell proliferation [5]. Increasing evidence supports a role for AT2R in the regulation of cellular growth, differentiation, apoptosis and regeneration of neuronal tissues [4]. Several studies, therefore, have aimed at Ang II receptors, and drugs such as AT1R antagonist losartan have been used in both basic research and clinical applications in the treatment of CVDs. Besides pharmacological targets on Ang II receptors, ACE has been recognized as one of the major targets in the treatment of hypertension and other CVDs. In clinical and basic research, therefore, ACE inhibitors (ACE-Is) and/or specific AT1R blockers (ARBs) have been used as effective drugs to inhibit the ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis in the management of CVDs [6].

Figure 1.

Angiotensinogen is transformed to Ang I by renin and subsequently converted by ACE into Ang II or by ACE2 into Ang (1–7). ACE2 also cleaves Ang I to Ang (1–9), which is further converted by ACE into Ang (1–7). Ang II acting on AT1R leads to physiological or pathophysiological activities. Acting on Mas receptors, Ang (1–7) might attenuate the actions of the ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis. Solid or dashed lines indicate positive or negative effects, respectively. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AT1R, angiotensin II type 1 receptor; Mas, Ang (1–7) receptor; ACE-I, ACE inhibitor; ARB, AT1R blocker.

The RAS is far more complex than initially anticipated, however. In recent years, several novel components of the RAS have been discovered, such as (pro)renin receptors [7,8], ACE2 [9] and the G-protein-coupled receptor Mas [10], which add to the complexity of the RAS. One of these new aspects for potential drug development is the identification of ACE2 [11,12] (Figure 1). ACE2 is a new homolog of ACE that favors the degradation of Ang II to Ang (1–7). Ang (1–7) binds to Mas receptors and is considered to be a beneficial peptide of the RAS cascade in the cardiovascular system. Actions of the ACE2-Ang (1–7)-Mas axis are often opposite to those of the well-documented ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis [8]. Accordingly, several studies have suggested that the activation of the ACE2-Ang (1–7)-Mas axis prevents and even reduces the damage observed in CVDs [13,14]. Unlike the ubiquitous ACE, ACE2 was originally thought to be predominantly expressed in the heart, kidney, testis and other tissues [11,12]. Subsequent studies, however, showed a much more widespread distribution of ACE2 in the lung, liver, small intestine and brain, although its levels were lower than those in the kidney [15,16]. It seems that both peripheral and central ACE2 might be involved in cardiovascular regulation.

In addition, many recent epidemiological studies have demonstrated the fetal origins of hypertension and CVDs. The abnormal development of the RAS in the fetus plays an important part in an increased risk of CVD in the adult [17,18]. Studies over the past two decades have shown that the RAS is crucial, not only in the control of fetal cardiovascular responses, body fluid balance and neuroendocrine regulation but also in postnatal health or illness [17,18]. Alterations of the normal development of the fetal RAS by environmental insults during pregnancy might have a significant[E1] impact on the in utero ‘programming’ of hypertension and CVDs in later life [19,20].

In this article, we briefly review the recently discovered physiological and pathophysiological effects of peripheral and brain ACEs in cardiovascular homeostasis. ACE-Is and ACE2 and their clinical relevance to CVDs are discussed. In addition, we summarize new progress in the study of the fetal RAS during development in the link with ACEs[E2], which might present an interesting field in perinatal medicine and preventive medicine.

The chemical structure and biochemical properties of ACEs

The structure and biochemical properties of ACE

ACE is a zinc metallopeptidase that converts inactive Ang I to active Ang II by cleaving the dipeptide histidine-leucine from the C terminal of Ang I[E3]. It is a key enzyme in the RAS for the production of Ang II. ACE is distributed throughout the body, including the central nervous system (CNS) [21]. ACE exists in both membrane-bound and soluble forms. The latter exists in blood plasma, amniotic fluid, seminal plasma and other body fluids [22]. There are two distinct isoenzymes of ACE. The endothelial isoenzyme (the somatic form) is present throughout the body and is composed of two highly similar domains, each of which bears a functional catalytic site. The other isoenzyme (the germinal form) is found exclusively in the testis and, with the exception of approximately 67 amino acids at the N terminus, is identical to the C-terminal domain of endothelial ACE, thus containing only a single catalytic site. Both forms of ACE function at the cell surface as ectoenzymes to hydrolyze circulating peptides.

ACE, or kininase II, was originally named for its ability to convert Ang I into Ang II or to inactivate bradykinin. ACE acts as a peptidyl dipeptidase removing COOH-terminal dipeptides from active peptides containing a free COOH terminus. However, many studies have demonstrated that it also can act as an endopeptidase on other substrates, such as substance P and the luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone [23]. Indeed, physiological substrates of ACE are broad and include not only Ang I, bradykinin and substance P but also hemoregulatory peptide N-acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro [24]. N-acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro, a putative bone marrow suppressor, is a hematopoietic factor that is a natural substrate for the NH2-terminal domain of ACE. It might have a role in hemopoietic[E4] cell differentiation, whereas both domains are thought to be important for regulating tissue and blood levels of the vasoactive hormones Ang II and bradykinin. Proangiotensin-12, or Ang (1–12), was found a few years ago. Ang (1–12) also could be a substrate of ACE and was identified as a propeptide of the RAS in plasma and tissues by Nagata et al. [25].[E5] This AGT-derived product is a previously unrecognized important precursor peptide to the RAS cascade. When injected intravenously in rats, Ang (1–12) immediately raised BP, and its vasoconstrictor and pressor effect mostly disappeared after administration of an ACE-I or Ang receptor blockers. Previous studies [25–27] suggested that the direct enzymatic conversion of ANG[E6] (1–12) into Ang I seems to be mediated by serum ACE. Prosser and colleagues [28], however, demonstrated recently that Ang (1–12) is converted to Ang II by cardiac chymase in rats. This enzyme is expressed in tissue mast cells and increased during ACE-I therapy. Inhibition of ACE activities has proved to be important in the treatment of hypertension and other CVDs [29].

The structure and biochemical properties of ACE2

Both ACE and ACE2 are endothelium-bound carboxypeptidases and can be cleaved by distinct metalloproteases located on the cell surface and released in soluble forms. They share many biochemical properties with each other. In contrast to the wide-expressed ACE, however, expression of ACE2 was initially described in the heart, kidney and testis [11,12,30]. Its expression was initially thought to be limited mainly to endothelial cells of the arteries, arterioles, venules in the heart and kidney [11,12,30], and renal tubular epithelium and vascular smooth muscle cells of the intrarenal arteries and coronary blood vessels [11]. Recent studies have shown that ACE2 expression is also ubiquitous in the brain and most cardiovascular-relevant tissues. Unlike ACE, ACE2 functions as a strict carboxypeptidase and cleaves a single C-terminal residue from a distinct range of substrates rather than a dipeptide; therefore, ACE2 is able to cleave the decapeptide Ang I to Ang (1–9) and octapeptide Ang II to Ang (1–7) in vitro [12,31] (Figure 1). The major role of ACE2 in Ang peptides metabolism is to produce Ang (1–7), however, which opposes actions of Ang II and mediates vasodilatation and antiproliferation. Therefore, through the Ang (1–7) pathway, ACE2 may[E7] counterbalance physiological and pathophysiological effects of the ACE-Ang II pathway [32]. It seems that conversion of Ang I to Ang (1–9) via ACE2 is not normally of physiological importance, except under conditions that raise Ang II levels[E8] (e.g. during ACE-I or ARB treatments). In addition to Ang I and Ang II, ACE2 also shows broad substrate specificity. It participates in the metabolism of other peptides not related to the RAS, such as neurotensin-(1–11), dynorphin A-(1–13), β-casomorphin-(1–7), ghrelin, [des-Arg9]-bradykinin and [Lys-des-Arg9]-bradykinin [31]. However, the physiological significance of ACE2 in the regulation of these peptides is unclear [33]. Despite sharing many biochemical properties with ACE, ACE2 is insensitive to classic ACE-Is [11,12].

ACE genes

As a homolog of ACE, ACE2 shares 42% sequence identity with ACE in the metalloprotease catalytic regions [12]. Comparison of their genomic structures indicates that the two genes are very similar. Collectrin is another homolog of ACE2 expressed exclusively in the kidney. Human collectrin has 47.8% identity with non-catalytic extracellular, transmembrane and cytosolic domains of ACE2; however, unlike ACE and ACE2, collectrin lacks active dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase catalytic domains [34]. ACE gene is located on chromosome 17, but ACE2 and collectrin genes are located close to each other in the same region of the X chromosome. It has been shown that the ACE2 gene is localized in a hypertension-related quantitative trait locus on the X chromosome [20]. Increasing evidence shows that ACE2 has a crucial role in the regulation of BP and cardiovascular function. For example, recent studies have suggested a strong association between the ACE2 gene polymorphism and hypertension in patients with metabolic syndrome [35], essential hypertension [36], left ventricular hypertrophy with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction [37].

The effects of two ACEs on the cardiovascular system

The effect of peripheral ACE and ACE2 on the cardiovascular system

The distribution of ACEs in the periphery

As mentioned above, a significant[E9] body of evidence has demonstrated that ACE is widely expressed not only in the lung but also in many other tissues [1], including renal proximal tubular epithelium, vascular adventitia, gut, macrophages and selected portions of the brain [38,39]. For example, cardiac ACE mRNA can be detected easily in both rat and human hearts [40,41]. ACE activity is also readily detectable by several methods, such as autoradiography or enzymatic assay. It has been demonstrated that ACE is present in viable cardiomyocytes, cardiac blood vessels, and the endocardium, either under normal conditions or after myocardial infarction [42].

ACE is detectable in vasculatures and is present in the endothelial cells of all vascular beds. There are, however, many reports of the converting enzyme activity in blood vessels not associated with the endothelium [43]. Indeed, in different layers of vascular wall, the data are not very consistent with each other. Wilson et al. [44] and Rogerson et al. [43] reported a predominant labeling of ACE in the endothelium and adventitia. Arnal et al. [45] showed high levels of expression in ACE mRNA and protein in the media of rat aorta, where the expression levels are almost as high as in the endothelium, whereas the expression is relatively low in the adventitia. Hamming et al. [46] investigated the localization of ACE2 protein in various human organs and found that ACE2 was present in arterial and venous endothelial cells and arterial smooth muscle cells in all organs studied. Additional studies are required for further clarification.

Accumulating data show that the kidney also contains a local tissue RAS that plays an important part in the control of renal functions and BP regulation [47,48]. ACE is expressed in the proximal tubular brush border in the kidney [39].

ACE2 expression has also been demonstrated in the heart [12,30,49] and vasculatures. It is localized to the endothelial and smooth muscle cells of intramyocardial vessels and on cardiac myocytes [11,12,49]. It has also been found in the thoracic aorta, carotid arteries and veins. In the kidney, ACE2 is predominantly expressed in the proximal tubular brush border [50], where it co-localizes with ACE. ACE2 is also found in endothelial and smooth muscle cells of renal vessels and in glomerular visceral and parietal epithelial cells [51].

Peripheral ACE and cardiovascular function

The studies with targeted homologous recombination in mouse embryonic stem cells have provided a surprising series of insights into the action and functional importance of the RAS [52–54]. ACE.1 (null) mice are null for all expression of ACE. These mice have shown a profound reduction in BP, the inability to concentrate urine and a maldevelopment of the kidney. By contrast, ACE.2 (tissue null) mice produce approximately 34% of the normal ACE enzymatic activity but completely lack tissue ACE. They also have low BP. Reduced BP is a key feature of ace deficient (no ACE) mice [53,54]. To investigate the fine control of body physiology by the RAS, Cole et al. [52] developed a novel promoter swapping approach to generate a more selective tissue knockout of ACE expression. With this approach, ACE.3 (liver ACE) mouse model was produced, which selectively expressed ACE in the liver but lacked all ACE within the vasculature [52]. Surprisingly, studies on these mice showed that endothelial expression of ACE was not required for BP control or normal renal function.

It has been demonstrated that ace-deficient mice are neither defective in heart development nor prone to heart disease [53,54]. In ace-deficient mice, hearts are histologically normal and no defect in heart function is detected [53,54]. Nonetheless, ACE plays an important part in vascular remodeling during vascular injury and restenosis, hypertension and atherosclerosis [55].

Peripheral ACE2 and cardiovascular function

Increasing evidence indicates that ACE2 has a crucial role in cardiovascular homeostasis, and its altered expression is associated with major cardiac and vascular pathophysiology. It has been shown that patients with hypertension show a marked ACE upregulation but ACE2 downregulation in both the heart and kidney [56,57]. This suggests that disruption of the balance between ACE and ACE2 results in abnormal BP control, thus ACE2 might protect against the increase in BP and the ACE2 deficiency might lead to hypertension. Crackower et al. [30] were the first to test ACE2 as the gene underlying the BP locus on the X chromosome and reported low ACE2 levels in the kidneys of three hypertensive rat stains[E10]. In salt-sensitive Sabra hypertensive rats, ACE2 mRNA and protein expression was lower than that in salt-resistant Sabra normotensive rats. In both spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) and spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rats, kidney ACE2 expression was also decreased, as compared with that of Wistar-Kyoto control rats [30,58]. A recent finding in a new congenic hypertensive rat strain, Lew.Tg (mRen2), derived from transgenic Ren-2 shows that the treatments with ACE-I lisinopril or ARB losartan induce an increase in cardiac and renal ACE2 expression and/or activity and a decrease in BP [59]. Taken together, these findings indicate that ACE2 is a key element in the regulation of BP. Nonetheless, its significance in hypertension needs to be studied further.

Previous studies have shown that the deletion of ACE2 results in significant[E11] alterations in cardiac and vascular functions, observed mainly from the ACE2 knockout animals [60,61]. For example, Crackower et al. [30] first demonstrated that ace2 null mice exhibited severe reduction in cardiac contractility and decreased aortic and ventricular pressure. Interestingly, these animals showed no changes in BP, although their plasma and tissue levels of Ang II were increased significantly[E12]. The cardiac contractile dysfunction was completely reversed by the concomitant deletion of the ACE gene in ace2 knockout (ACE2-/y) mice, suggesting that the cardiac function is modulated by the balance between ACE and ACE2 and that the increase in local cardiac Ang II is involved in these abnormalities [30]. By contrast, Gurley et al. [60] demonstrated that their ACE2 null mice lacked cardiac structural or functional changes but exhibited a small elevation of baseline BP and enhanced susceptibility to Ang II-induced hypertension. Their recent studies have shown that there are no changes in ACE2-/y with a 129/SvEv background and variable changes in mixed animals [60,62]. In another study, Yamamoto et al. [61] also failed to identify cardiac abnormalities in their ace2 knockout mice. They did, however, demonstrate reduced cardiac contractility after transverse aortic constriction, a model of pressure overload. The transverse aortic constriction in the ace2 knockout mice was associated with a marked increase in cardiac Ang II levels and increased fibrosis, left ventricular dilation and myofibrillar disarray, as compared with wild-type mice subjected to the same procedure [61].

ACE2 might influence the electrical pathways of the heart, however. Indeed, Donoghue and colleagues showed spontaneous lethal episodes of ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation developed in ACE2 transgenic mice [63]. The level of ACE2 upregulation correlated with the severity of the conduction disturbance. This supports a previous study that demonstrated that high concentrations of Ang (1–7) in the heart induced cardiac arrhythmias [64]. These findings suggest an important role for ACE2 in counteracting the effects of accumulating Ang II.

Other studies further demonstrated the important role of ACE2 in cardiac function. Burrell et al. [49] showed that ACE2 increased after myocardial infarction, suggesting that enzyme plays a part in the negative modulation of the RAS in the metabolism of Ang peptides after myocardial injury. Cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and hypertension have been found to be associated with an increase in cardiac ACE2 gene expression and ACE2 activity in rats [65]. Ang (1–7)-forming activity has also been observed in patients with either idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy or primary pulmonary hypertension, which is inhibited by the ACE2-specific inhibitor MLN4760 [66]. Recent studies on myocardial infarcted animals have shown that the use of Ang II formation inhibitors (i.e. ACE-Is)[E13] or ARBs results in an increase in ACE2 transcription and translation [32,65,67,68]. These observations imply that upregulation of ACE2 is a compensatory response to inhibition of Ang II, demonstrate that peripheral ACE2 exerts a pivotal role in cardiovascular functions and indicate great potential for drug development targeting of ACE2.

The effects of central ACE and ACE2 on the cardiovascular system

Brain ACE and cardiovascular function

In the brain, ACE mRNA is expressed in the choroid plexus, caudate putamen, cerebellum, brain stem and hippocampus in the rat [69]. The localization of ACE protein in the CNS was verified by quantitative autoradiography with high levels in the choroid plexus, blood vessels, subfornical organ (SFO) and organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis, and lower levels in the thalamus, hypothalamus, basal ganglia and posterior pituitary gland [70].

A large body of evidence shows that a hyperactive brain RAS plays a crucial part in the development and maintenance of hypertension. Although the precise mechanisms by which Ang II triggers hypertension are not clear, they seem to be involved in an increased sympathetic vasomotor tone and altered cardiac baroreflex function [71]. Ang II acting on brain AT1R [72,73] induces an increase in BP by promoting vasoconstriction, renal sodium and water reabsorption, increasing cardiac output, sympathetic tone [74] and arginine vasopressin (AVP) release [75] and stimulating the sensation of thirst in the CNS. In SHRs, the upregulation of brain RAS components such as AGT, Ang II, ACE and AT1R precedes and sustains the development of hypertension [72].

Brain ACE2 and cardiovascular function

Many recent studies have shown that ACE2 is widespread throughout the brain [11,12]. In addition, studies performed in brain cell cultures have demonstrated that ACE2 was expressed predominantly in glial cells [76]. After these initial studies, evidence of ACE2 and its role in the CNS emerged rapidly. For example, using a selective antibody, Doobay et al. [15] found that ACE2 was present not only in nuclei like the cardio-respiratory neurons of the brainstem involved in the central regulation of cardiovascular function but also in non-cardiovascular areas, such as the motor cortex and raphe. In addition, Lin et al. [16] showed the presence of ACE2 mRNA and protein in the mouse brainstem. These findings suggest a broad effect of ACE2 in the CNS, in addition to its regulation of cardiovascular function.

Now, it is well established that the ACE2-Ang (1–7)-Mas axis is a new avenue of actions of the RAS [77]. Emerging evidence clearly supports the principle that the ACE2-Ang-(1–7)-Mas axis is a physiologically relevant arm of the RAS in counterbalancing the actions of the ACE-Ang II-AT1R pathway [77]. ACE2 can metabolize Ang II to the vasodilatory peptide Ang (1–7) and, therefore, to some extent, the physiological role of central Ang (1–7) indicates some roles of brain ACE2. Ang (1–7) acts through binding to its receptor Mas, which has been demonstrated to be highly expressed in the brain[E14] [78]. There is a large body of evidence for the role of Ang (1–7) in the CNS. Ang (1–7) has been shown to be the pleiotropic bioactive component of the RAS. It exerts effects that can be identical to, different to or the opposite of those displayed by Ang II [79,80]. For example, it mimics Ang II stimulation of AVP and prostaglandin release, as well as peripheral norepinephrine outflow [80]. By contrast, Ang (1–7) causes natriuresis, diuresis and vasodilatation, as well as inhibiting angiogenesis and cellular growth [79]. In many cases, this peptide acts as an endogenous antagonist of Ang II. Ang (1–7) has been suggested to have an antihypertensive effect, as well as counterbalancing pressor and proliferative actions of Ang II, because its effects that oppose those of Ang II are enhanced in rat models of hypertension [79]. Intracerebroventricular infusion of Ang (1–7) induced a significant[E15] increase in baroreceptor control of heart rate sensitivity for reflex bradycardia [10,81]. Central Ang (1–7) exerts the antihypertensive effect in many ways. Gironacci et al. [78] demonstrated that central Ang (1–7) decreased sympathetic nervous system activity by inhibiting norepinephrine release from the hypothalamus in SHR and acting through a bradykinin/nitric oxide-mediated mechanism that stimulates the cGMP/protein kinase G signaling pathway. It might also participate in the potentiation of bradykinin release and the kinin receptor expression [82].

Accordingly, it is widely accepted that ACE2 plays a pivotal part in the central control of cardiovascular homeostasis. Diz et al. [83] reported recently that ACE2 activity, as well as ACE and neprilysin activities, were present in plasma membrane fractions of the dorsomedial medulla in Sprague-Dawley rats. Injections of the Ang (1–7) antagonist [D-Ala(7)]-Ang (1–7) into the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) reduced the baroreceptor reflex sensitivity for control of heart rate by 40%, whereas injections of the AT1R antagonist candesartan increased the baroreceptor reflex sensitivity by 40%, when reflex bradycardia was assessed. Consistently, injections of MLN4760, the most potent and selective ACE2 inhibitor currently available, into the NTS reduced the baroreceptor reflex sensitivity. These findings support the concept that within the NTS, local synthesis of Ang (1–7) from Ang II is required for normal sensitivity for the baroreflex control of the heart rate in response to increases in arterial pressure.

Xia et al. [84] reported that activation of central AT1R reduced ACE2 activity in hypertensive mice, thereby impairing baroreflex function and promoting hypertension. Overexpression of ACE2 in the brain reduces hypertension by improving arterial baroreflex and autonomic function. This supports the idea that brain ACE2 plays a crucial part in the central regulation of BP and the development of hypertension. Moreover, ACE2 overexpression in the SFO also impairs Ang II-mediated pressor and dipsogenic responses, which is[E16] mediated – at least in part – by inhibiting AT1R expression [85]. All of these experimental results have offered a new target for the treatment of hypertension and other CVDs.

The studies about the brain ACE2 and its role in the cardiovascular system are still limited, however, although some important information has come out in recent years.[E17] Doobay and co-workers [15] recently examined ACE2 immunostaining in transgenic mouse brain sections from neuron-specific enolase-AT(1A) (overexpressing AT(1A) receptors), R(+)A(+) (overexpressing AGT and renin) and control (nontransgenic littermates) mice. These studies showed that ACE2 staining was widely distributed throughout the brain and was localized to the cytoplasm of neuronal cells. In the SFO, ACE2 was increased significantly[E18] in the transgenic mice, whereas in the brainstem, ACE2 mRNA and protein expression were inversely changed when comparing transgenic to nontransgenic mice. This is supported by subsequent studies by Lin et al. [16], who demonstrated that a reduction in AT1R mRNA was associated with a reduction in ACE2 mRNA in the brainstem by using a gene silencing approach. These findings suggest that ACE2 levels are tightly regulated by other components of the RAS, supporting the notion that ACE2 acts as a compensatory mechanism to limit brain RAS hyperactivity. Moreover, ACE2 expression in brain areas involved in the control of cardiovascular functions suggests its crucial role in the central regulation of BP and diseases involving the autonomic nervous system, such as hypertension [15]. In addition, Feng et al. [85] showed recently that ACE2 overexpression in the SFO impaired Ang II-mediated pressor and drinking responses at least by inhibiting AT1R expression, which indicates ACE2 has an effect on the downregulation of AT1R in this region. Further studies are needed to address the details of the phenomenon observed.

ACE-Is, ACE2 and their clinical relevance to the CVD

ACE-Is and their therapeutic effects on CVD

The ACE-Ang II-AT1R axis has long been thought to be the main path for the RAS in controlling cardiovascular function; therefore, specific ACE-Is and ARBs have been the major therapeutic strategies for the treatment of hypertension and other CVDs [6]. Many potent ACE-Is have been synthesized and subsequently evaluated in clinical trials. As is well known, ACE is a key enzyme of the RAS, which converts Ang I to Ang II and degrades bradykinin into inactive peptides. In many CVDs, levels of ACE are increased [86]. This results in increased circulating and tissue levels of Ang II and decreased levels of bradykinin. The imbalance of Ang II and bradykinin will induce harmful effects on myocardial or vascular functions and structures, including vasoconstriction, salt and water retention, ventricular hypertrophy, sympathetic nervous system overstimulation, and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. ACE-Is block the conversion of Ang I to Ang II and inhibit the breakdown of bradykinin, which can recover the balance of Ang II and bradykinin. Evidence from clinical trials demonstrates that ACE inhibition has this impact on almost all classes of cardiovascular drugs, reducing the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes mellitus and renal impairment [87]. They have been shown to benefit patients with hypertension, heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, postmyocardial infarction, nephropathy, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, stroke and transient ischemic attack [88,89]. A novel functional role of ACE involved in outside-in signaling has been identified by Fleming and co-workers [90]. These investigators showed that binding of an ACE-I to ACE led to the activation of signal events that were likely to affect the expression of several proteins. The characterization of the novel signaling pathway via ACE also suggests that some of the beneficial effects of ACE-Is can be attributed to the activation of a distinct ACE signaling cascade, rather than to changes in Ang II and bradykinin levels [90].

In addition to ACE inhibition, the RAS also can be inhibited by ARBs. ACE-Is and ARBs have significant[E19] protective effects on myocardial and vascular functions, in addition to their anti-hypertensive effects. Several studies noted a marked increase in cardiac ACE2 expression in response to RAS blockade by ACE-Is [32] or ARBs [32,67,68] (Figure 1). The cardioprotection by RAS blockade is caused not only by the reduced Ang II-mediated effects but also by a local increase of Ang (1–7) that has beneficial effects on the heart by binding to its putative receptor Mas [10]. However, several clinical investigations found that both classes of drugs have some limitations. For example, in some patients, increased plasma Ang II concentrations were observed during the ACE-Is therapy. This was partly because of the production of Ang II via non-ACE pathways. Moreover, elevated aldosterone concentrations can also occur in a significant[E20] proportion of patients during the ACE-Is therapy. By contrast, ARBs block the deleterious effects of Ang II at AT1R, whereas the beneficial effects of kinins might be diminished.[E21] The ARB therapy can result in the activation of AT2R, resulting in potentially beneficial anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic and antiproliferative effects. The combination therapy with ACE-Is plus ARBs offers the potential for effective BP control, decreased aldosterone production and enhanced kinin activity and, thus, is the focus of recent clinical trials and is currently being investigated [88,89]. In addition, it also is possible to consider a single drug that contains both ACE-Is and ARBs with various concentrations of the two inhibitors.

ACE2, a potential target for CVD therapeutics

For several years, ACE has been thought to be the major regulatory enzyme in the RAS. After the discovery of ACE2, it has gained recognition as an important regulator of cardiovascular function. Emerging evidence clearly supports the concept that the ACE2-Ang (1–7)-Mas axis is a physiologically cardioprotective pathway of the RAS in counterbalancing actions of the ACE-Ang II-AT1R pathway. Expression and activity of ACE2 are altered in several CVDs, including hypertension, renal damage, heart failure and vascular remodeling; therefore, the ACE2-Ang (1–7)-Mas pathway offers an opportunity to develop a new and refined therapeutic strategy for CVDs. Before embarking on the therapeutic aspects, however, more investigations are needed to elucidate the details and exact mechanisms of ACE2 in the regulation of cardiovascular function. MLN4760 is an inhibitor against ACE2. New and selective drugs or activators targeting ACE2 should be explored. Because ACE2 opposes the vasoactive and proliferative actions of Ang II and shows the beneficial effects for the cardiovascular system, the upregulation of ACE2 expression or activity is a desirable characteristic in the treatment of CVDs. Increasing ACE2 levels by stimulating its expression or the exogenous application of recombinant ACE2 might have beneficial effects in several disease conditions and should be the scope of future studies.

Actually, recent data from several groups have shown that ACE2 gene therapy provides beneficial effects on cardiovascular functions. Researchers have overexpressed ACE2 in the heart of adult animals using gene transfer techniques. They found that ACE2 gene delivery is able to protect the heart against myocardial injuries induced by Ang II infusion [91], ischemia [92] or damages elicited by high BP in SHRs [93]. In addition, recent studies have shown that administration of ACE2 activators might be a valid strategy for antihypertensive therapy. Prada et al. [94] demonstrated that xanthenone, a compound that enhances ACE2 activity, causes considerable reduction in BP and a striking reversal of cardiac and renal fibrosis in hypertension of the SHR model. They presented for the first time a structure-based drug discovery approach to enable the development of enzyme activators. The clinical ramifications of their study are significant[E22] for CVD and other diseases associated with hypertension, such as obesity and diabetes.

The ACEs in the fetus

Compared with the extensive studies of the RAS in the adult, the investigations related to the RAS in the fetus are substantially fewer[E23]. Since the concept of the ‘fetal origins of adult health and diseases’ was introduced [95], however, the development of the RAS in normal and abnormal patterns before birth has attracted great attention. Increasing evidence suggests that an overactivated RAS, including increased ACE activity [17,18], contributes significantly[E24] to fetal programming of hypertension in the adult.

Functional development of ACE on fetal cardiovascular response and body fluid homeostasis

The ACE immunoreactivity has been demonstrated in human fetal brain [96]. Both ACE mRNA and protein were detected in the choroid plexus and other brain regions in fetal rats and rabbits [69,70]. In rat fetal brain on day 19 of gestation, ACE was detected in the choroid plexus, SFO and posterior pituitary but not in extrapyramidal structures and the anterior pituitary [95]. After birth, ACE was identified in the caudate-putamen [96]. By contrast, ACE2’s expression in the brain was absent until embryonic day 15, when a prompt increase in expression followed [30].

A physiological question was raised immediately after the discovery of ACE in the fetal brain (i.e. whether and when the brain ACE in the fetus is functional during development). Although ACEs expressed in the developing fetus before birth, the functional development of these enzymes was less understood. In recent studies, we investigated the functional development of brain ACE related to the cardiovascular regulation in utero in the chronically prepared near-term ovine fetus with intracerebroventricular injection of Ang I. An in utero survival surgery was exerted in the ovine fetuses [97,98]. An intracranial cannulae was placed in the fetal lateral ventricle at 70%–90% gestation. After recovery for 4–5 days, the fetal sheep was tested. We found that intracerebroventricular injection of Ang I, the substrate of ACE, induced Ang II-like physiological actions, including an increase of fetal BP and plasma AVP concentrations, as well as c-fos expression in the putative cardiovascular nuclei such as the paraventricular nuclei. Captopril, an inhibitor of ACE, suppressed the Ang I-induced responses significantly[E25]. These results indicate that the functional development of central endogenous ACE is established at least at the last third of gestation and that endogenous brain RAS-stimulated pressor responses and AVP release by acting at the sites are consistent with the cardiovascular network in the hypothalamus (Shi et al., unpublished data).

Because the last third of gestation is crucial in functional development and might serve as a vulnerable ‘window’ in the face of environmental insults leading to disease programming, this novel information gained in fetal sheep contributes not only to the understanding of normal neurophysiologic development in the fetal brain but also to the knowledge of RAS-mediated hypertension development of fetal origins.

Alterations in ACEs in fetal programming of hypertension

Increasing evidence supports the concept that adverse events in the perinatal environment predispose an individual to diseases later in life [95]. ACE and ACE2 are coexpressed in many tissues, and alterations in their expressions and activities might participate in fetal programming of hypertension [99,100]. For example, in an animal model of a low-protein diet during pregnancy, elevated BP in adult offspring was associated with increased pulmonary and plasma ACE activity [17], and ACE-Is prevented the increase of BP [101]. In addition, hypertension in lambs exposed to low protein in utero was associated with an enhanced renal ACE protein expression [102].

Although glucocorticoid exposure can acutely increase ACE expression in vascular smooth muscle [103], chronic upregulation of the RAS components might also occur as a result of inappropriate exposure to glucocorticoids in utero. Recently, Shaltout et al. [100] investigated the effect of antenatal betamethasone given to sheep at a dose and gestational time point similar to the therapy that women at risk for preterm delivery receive. They found that the antenatal betamethasone treatment increased mean arterial pressure (97 ± 3 versus 83 ± 2 mmHg, P < 0.05) in the adult offspring, and this increase in BP was blocked by an AT1R antagonist, candesartan. This suggests a higher vasoconstrictor tone in the betamethasone-treated animals than in the control animals. They further evaluated several key enzymes that are crucial for maintaining the balance between Ang II and Ang (1–7). They showed that the betamethasone treatment was associated with a higher serum ACE activity but lower serum ACE2 activity, which supports a shift toward greater synthesis (ACE) and reduced metabolism (ACE2) of Ang II, as well as reduced formation of Ang (1–7). The alterations in the ratio of these peptides would favor an elevation of BP. Antenatal betamethasone treatment was also associated with reduced ACE2 activity in the isolated proximal tubules and in the urine. The reduction in the ACE2 activity in both of these compartments suggests a reduced expression of the enzyme, rather than increased shedding of the enzyme into the tubular fluid. Moreover, an ACE2 immunoblot of the proximal tubules revealed lower protein levels consistent with the lower ACE2 activity in the tubules. ACE and neprilysin activities in the proximal tubules were not altered by the antenatal betamethasone treatment. Taken together, these data indicate that antenatal steroid treatment results in the chronic alteration of ACE and ACE2 in the circulatory and tubular compartments, which might contribute to the increased BP in fetal programming of hypertension.

ACE-Is regulate blood vessel formation during development

The RAS has an essential role in pathological development in blood vessel growth [55]. Cooper and colleagues found that infants born to women who took ACE-Is during the first trimester of pregnancy had an excess of major congenital malformations compared with unexposed women, supporting the notion that inhibition of blood vessel formation might account for congenital abnormalities owing to exposure to ACE-Is during the first trimester [104]. However, mice lacking ACE showed no evidence of congenital abnormalities such as those seen in human fetuses exposed to ACE-Is [54]. The differences are not currently fully understood. The developing brain and heart in the fetus are major sites for the formation of blood vessels, and the pattern of the recently reported malformations resulting from exposure to ACE-Is during the first trimester are consistent with the impairment of vasculogenesis and early angiogenesis. However, the precise roles of the different constituents of this system remain poorly understood.

It is anticipated that prenatal medicine in the prevention of diseases in fetal origins will attract more and more attention given that several adult diseases can be developed originally at prenatal stages. Recent progress has been made in showing that the RAS plays an important part in programming diseases initiated in the fetal period; therefore, future directions for the prevention of RAS-mediated diseases of fetal origins might focus on ACEs and their inhibitors at both prenatal and postnatal stages.

Concluding remarks

Different metabolic avenues leading Ang I to the Ang II-AT1R/AT2R pathway via ACE or the Ang (1–7)-Mas pathway via ACE2 have been demonstrated in the past decade. The important point for such a difference between the two pathways lies in their opposite effects, which could either harm or benefit cardiovascular regulation, inducing or preventing certain CVDs. Accumulating evidence for the effects of ACEs from both basic and clinical studies has opened new opportunities for the further development of new drugs based on different metabolic effects of ACE and ACE2. Furthermore, in the prevention of certain types of hypertension or reducing the risk of CVDs of fetal origins, drugs targeting ACE and ACE2 could be considered as a preventive tool in prenatal medicine in the future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH grants HL82779 (to L.Z.), HL83966 (to L.Z.) and HL090920 (to Z.X.); NSFC (30973211) (to Z.X.); and Jiangsu/Suzhou Grants (90134602 and SZS0602) (to Z.X. and C.M.). We apologize to all authors whose work could not be cited owing to space limitations.

Biographies

Prof Zhice Xu

Graduated from Suzhou Medical College, PhD (University of Cambridge), Postdoctoral fellow (University of Iowa), Assistant Professor(UCLA), Associate Professor (Loma Linda University), Professor, Director, Institute for Fetal Origin-Diseases, 1st Hospital & Perinatal Biology Center of Soochow University; Director, Suzhou Key Lab for Perinatal Medicine; this is the first lab in the world to study herb medicine in the fetus in conscious animal models. Main research interests: development of renin-angiotensin-system & its physiological/pathophysiological changes from fetal stages; safety evaluation and development of perinatal medicine; development of central pathways in cardiovascular and body fluids regulations, fetal origins of adult health and diseases.

Prof Lubo Zhang

Dr. Zhang received his PhD in Pharmacology from Iowa State University in 1990 and is professor of Pharmacology and Physiology at Loma Linda University School of Medicine. He was the President of the Western Pharmacology Society in the US in 2007–2008, and has been members in the various study sections for grant review in US National Institutes of Health and American Heart Association for more than 10 years. Dr. Zhang is the author/coauthor of over 450 scientific articles, book chapters and abstracts. His research focuses on epigenetic mechanisms in fetal programming of adult cardiovascular disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Teaser: ACE2-AngI-Ang (1–7)-Mas pathway presents a new area for drug discovery in the treatment of cardiovascular disease, as well as in perinatal medicine and preventive medicine against diseases of fetal origins.

References

- 1.Paul M, et al. Physiology of local renin-angiotensin systems. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:747–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brede M, Hein L. Transgenic mouse models of angiotensin receptor subtype function in the cardiovascular system. Regul. Pept. 2001;96:125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy BI. Can angiotensin II type 2 receptors have deleterious effects in cardiovascular disease? Implications for therapeutic blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Circulation. 2004;109:8–13. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096609.73772.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steckelings UM, et al. The AT2 receptor: a matter of love and hate. Peptides. 2005;26:1401–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoll M, et al. The angiotensin AT2-receptor mediates inhibition of cell proliferation in coronary endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:651–657. doi: 10.1172/JCI117710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eberhardt RT, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blockade: an innovative approach to cardiovascular pharmacotherapy. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993;33:1023–1038. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen G, Danser AHJ. Prorenin and (pro)renin receptor: a review of available data from in vitro studies and experimental models in rodents. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:557–563. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos RAS, et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) and its receptor as a potential targets for new cardiovascular drugs. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2005;14:1019–1031. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.8.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazartigues E, et al. The two fACEs of the tissue renin-angiotensin systems: implication in cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007;13:1231–1245. doi: 10.2174/138161207780618911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos RAS, et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:8258–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432869100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donoghue M, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1–9. Circ. Res. 2000;87:E1–E9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tipnis SR, et al. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33,238–33,243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diez-Freire C, et al. ACE2 gene transfer attenuates hypertension-linked pathophysiological changes in the SHR. Physiol. Genomics. 2006;27:12–19. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00312.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreira AJ, et al. The nonpeptide angiotensin-(1–7) receptor Mas agonist AVE-0991 attenuates heart failure induced by myocardial infarction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;292:H1113–H1119. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00828.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doobay MF, et al. Differential expression of neuronal ACE2 in transgenic mice with overexpression of the brain renin-angiotensin system. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007;292:R373–R381. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00292.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Z, et al. RNA interference shows interactions between mouse brainstem angiotensin AT1 receptors and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:676–684. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.041657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langley-Evans SC, Jackson AA. Captopril normalises systolic blood pressure in rats with hypertension induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Physiol. 1995;110:223–228. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(94)00177-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherman RC, Langley-Evans SC. Antihypertensive treatment in early postnatal life modulates prenatal dietary influences upon blood pressure in the rat. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2000;98:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langley SC, Jackson AA. Increased systolic pressure in adult rats induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diet. Clin. Sci. 1994;86:217–222. doi: 10.1042/cs0860217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langley-Evans SC, et al. Intrauterine programming of hypertension: the role of the renin-angiotensin system. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1999;27:88–93. doi: 10.1042/bst0270088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang HYT, Neff NH. Distribution and properties of angiotensin converting enzyme of rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1972;19:2443–2450. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erdos EG, Skidgel RA. The angiotensin-I-converting enzyme. Lab. Invest. 1987;56:345–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skidgel RA, Erdoes EG. Novel activity of human angiotensin I converting enzyme: release of the NH2 and COOH terminal tripeptides from the luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1985;82:1025–1029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rousseau A, et al. The hemoregulatory peptide N-acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro is a natural and specific substrate of the N-terminal active site of human angiotensin-converting enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:3656–3661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagata S, et al. Isolation and identification of proangiotensin-12, a possible component of the renin-angiotensin system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;350:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chappell MC, et al. Distinct processing pathways for the novel peptide angiotensin-(1–12) in the serum and kidney of the hypertensive mRen2.Lewis rat (Abstract) Hypertension. 2007;50:e139. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trask AJ, et al. Angiotensin-(1–12) is an alternate substrate for angiotensin peptide production in the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;294:H2242–H2247. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00175.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prosser HC, et al. Cardiac chymase converts rat proangiotensin-12 (PA12) to angiotensin II: effects of PA12 upon cardiac haemodynamics. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;82:40–50. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ondetti MA. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Hypertension. 1991;18 Suppl. 5:III134–III135. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.18.5_suppl.iii134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crackower MA, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417:822–828. doi: 10.1038/nature00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vickers C, et al. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14838–14843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrario CM, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111:2605–2610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia H, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in the brain: properties and future directions. J. Neurochem. 2008;107:1482–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H, et al. Collectrin, a collecting duct-specific transmembrane glycoprotein, is a novel homolog of ACE2 and is developmentally regulated in embryonic kidneys. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:17132–17139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhong J, et al. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 gene A/G polymorphism and elevated blood pressure in Chinese patients with metabolic syndrome. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2006;147:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan X, et al. Polymorphisms of ACE2 gene are associated with essential hypertension and antihypertensive effects of captopril in women. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;82:187–196. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang W, et al. Association study of ACE2 (angiotensin I-converting enzyme 2) gene polymorphisms with coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction in a Chinese Han population. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2006;111:333–340. doi: 10.1042/CS20060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cushman DW, Cheung HS. Concentration of the angiotensin-converting enzyme in tissues of rat. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1971;250:261–265. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(71)90142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sibony M, et al. Gene expression and tissue localization of the two isoforms of angiotensin I converting enzyme. Hypertension. 1993;21:827–835. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirsch AT, et al. Tissue-specific activation of cardiac angiotensin converting enzyme in experimental heart failure. Circ. Res. 1991;69:475–482. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paul M, et al. Gene expression of the components of the renin-angiotensin system in human tissues: quantitative analysis by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;91:2058–2064. doi: 10.1172/JCI116428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hokimoto S, et al. Expression of angiotensin converting enzyme in remaining viable myocytes in human ventricles after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1996;94:1513–1518. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.7.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogerson FM, et al. Presence of angiotensin converting enzyme in the adventitia of large blood vessels. J. Hypertens. 1992;10:615–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson SK, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme labeled with [3H]captopril. Tissue localizations and changes in different models of hypertension in the rat. J. Clin. Invest. 1987;80:841–851. doi: 10.1172/JCI113142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnal JF, et al. ACE in three tunicae of rat aorta: expression in smooth muscle and effect of renovascular hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1994;267:H1777–H1784. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.5.H1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamming I, et al. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sigmund CD. Genetic manipulation of the renin-angiotensin system in the kidney. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2001;173:67–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stec DE, Sigmund CD. Physiological insights from genetic manipulation of the renin-angiotensin system. News Physiol. Sci. 2001;16:80–84. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.2.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burrell LM, et al. Myocardial infarction increases ACE2 expression in rat and humans. Eur. Heart J. 2005;26:369–375. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sluimer JC, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and activity in human carotid atherosclerotic lesions. J. Pathol. 2008;215:273–279. doi: 10.1002/path.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lely AT, et al. Renal ACE2 expression in human kidney disease. J. Pathol. 2004;204:587–593. doi: 10.1002/path.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cole JM, et al. New approaches to genetic manipulation of mice: tissue-specific expression of ACE. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F599–F607. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00308.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Esther CR, et al. Mice lacking angiotensin-converting enzyme have low blood pressure, renal pathology, and reduced male fertility. Lab. Invest. 1996;74:953–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krege JH, et al. Male-female differences in fertility and blood pressure in ACE-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;375:146–148. doi: 10.1038/375146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heeneman S, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and vascular remodeling. Circ. Res. 2007;101:441–454. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koka V, et al. Angiotensin II up-regulates angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE), but down-regulates ACE2 via the AT1-ERK/p38 MAP kinase pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;172:1174–1183. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wakahara S, et al. Synergistic expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and ACE2 in human renal tissue and confounding effects of hypertension on the ACE to ACE2 ratio. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2453–2457. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tikellis C, et al. Developmental expression of ACE2 in the SHR kidney: a role in hypertension? Kidney Int. 2006;70:34–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jessup JA, et al. Effect of angiotensin II blockade on a new congenic model of hypertension derived from transgenic Ren-2 rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;291:H2166–H2172. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00061.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gurley SB, et al. Altered blood pressure responses and normal cardiac phenotype in ACE2-null mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2218–2225. doi: 10.1172/JCI16980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamamoto K, et al. Deletion of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 accelerates pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction by increasing local angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2006;47:718–726. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000205833.89478.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gurley SB, Coffman TM. Altered blood pressure responses and normal cardiac phenotype in ACE2-null mice. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:538–542. doi: 10.1172/JCI16980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Donoghue M, et al. Heart block, ventricular tachycardia, and sudden death in ACE2 transgenic mice with downregulated connexins. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2003;35:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neves LAA, et al. Effect of angiotensin-(1–7) on reperfusion arrhythmias in isolated rat hearts. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1997;30:801–809. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1997000600016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burchill L, et al. Acute kidney injury in the rat causes cardiac remodeling and increases angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:622–630. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zisman LS, et al. Increased angiotensin-(1–7)-forming activity in failing human heart ventricles: evidence for up regulation of the angiotensin-converting enzyme homologue ACE2. Circulation. 2003;108:1707–1712. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000094734.67990.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ishiyama Y, et al. Upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 after myocardial infarction by blockade of angiotensin II receptors. Hypertension. 2004;43:970–976. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000124667.34652.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karram T, et al. Effects of spironolactone and eprosartan on cardiac remodeling and angiotensin-converting enzyme isoforms in rats with experimental heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;289:H1351–H1358. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01186.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Whiting P, et al. Expression of angiotensin converting enzyme mRNA in rat brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1991;11:93–96. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90026-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rogerson FM, et al. Localization of angiotensin converting enzyme by in vitro autoradiography in the rabbit brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 1995;8:227–243. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(95)00049-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chapleau MW, Abboud FM. Neuro-cardiovascular regulation: from molecules to man. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;940:xiii–xxii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fink GD, et al. Area postrema is critical for angiotensin-induced hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 1987;9:355–361. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gutkind JS, et al. Increased concentration of angiotensin II binding sites in selected brain areas of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Hypertens. 1988;6:79–84. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Falcon JC, et al. Effects of intraventricular angiotensin II mediated by the sympathetic nervous system. Am. J. Physiol. 1978;235:H392–H399. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.235.4.H392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Unger T, et al. Central blood pressure effects of substance P and angiotensin II: role of the sympathetic nervous system and vasopressin. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1981;71:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gallagher PE, et al. Distinct roles for ANG II and ANG-(1–7) in the regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in rat astrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C420–C426. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00409.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Phillips MI, de Oliveira EM. Brain renin angiotensin in disease. J. Mol. Med. 2008;86:715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0331-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gironacci MM, et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) inhibitory mechanism of norepinephrine release in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2004;44:783–787. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000143850.73831.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ferrario CM, et al. Counterregulatory actions of angiotensin-(1–7) Hypertension. 1997;30:535–541. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gironacci MM, et al. Effects of angiotensin II and angiotensin-(1–7) on the release of [3H]-norepinephrine from rat atria. Hypertension. 1994;24:457–460. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.24.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Campagnole-Santos MJ, et al. Differential baroreceptor reflex modulation by centrally infused angiotensin peptides. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:R89–R94. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.1.R89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu J, et al. Effects of intracerebroventricular infusion of angiotensin-(1–7) on bradykinin formation and the kinin receptor expression after focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Brain Res. 2008;1219:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Diz DI, et al. Injections of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibitor MLN4760 into nucleus tractus solitarii reduce baroreceptor reflex sensitivity for heart rate control in rats. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:694–700. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xia H, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-mediated reduction of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity in the brain impairs baroreflex function in hypertensive mice. Hypertension. 2009;53:210–216. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.123844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Feng Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 overexpression in the subfornical organ prevents the angiotensin II-mediated pressor and drinking responses and is associated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor downregulation. Circ. Res. 2008;102:729–736. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.169110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pinto YM, et al. Selective and time related activation of the cardiac renin–angiotensin system after experimental heart failure: relation to ventricular function and morphology. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:1933–1938. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.11.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.White HD. Should all patients with coronary disease receive angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors? Lancet. 2003;362:755–757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gradman AH, Papademetriou V. Combined renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition in patients with chronic heart failure secondary to left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Am. Heart J. 2009;157 Suppl. 6:S17–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Papademetriou V. Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system to prevent ischemic and atherothrombotic events. Am. Heart J. 2009;157:S24–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fleming I, et al. New fACEs to the renin-angiotensin system. Physiology (Bethesda) 2005;20:91–95. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00003.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huentelman MJ, et al. Protection from angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis by systemic lentiviral delivery of ACE2 in rats. Exp. Physiol. 2005;90:783–790. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Der Sarkissian S, et al. Cardiac overexpression of ACE2 protects the heart from ischemia-induced pathophysiology. Hypertension. 2008;51:712–718. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.100693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Díez-Freire C, et al. ACE2 gene transfer attenuates hypertension-linked pathophysiological changes in the SHR. Physiol. Genomics. 2006;27:12–19. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00312.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Prada JAH, et al. Structure-based identification of small-molecule angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activators as novel antihypertensive agents. Hypertension. 2008;51:1312–1317. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.108944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barker DJ, Osmond C. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet. 1986;1:1077–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Strittmatter SM, et al. Differential ontogeny of rat brain peptidases: prenatal expression of enkephalin converytase and postnatal development of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Brain Res. 1986;394:207–215. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(86)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shi L, et al. Central cholinergic mechanisms mediate swallowing, renal excretion, and c-fos expression in the ovine fetus near term. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009;296:R318–R325. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90632.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shi L, et al. Central cholinergic signal-mediated neuroendocrine regulation of vasopressin and oxytocin in ovine fetuses. BMC Dev. Biol. 2008;8:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Brosnihan KB, et al. Does the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)/ACE2 balance contribute to the fate of angiotensin peptides in programmed hypertension? Hypertension. 2005;46:1097–1099. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000185149.56516.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shaltout HA, et al. Alterations in circulatory and renal angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in fetal programmed hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;53:404–408. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.124339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sherman RC, Langley-Evans SC. Early administration of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor captopril, prevents the development of hypertension programmed by intrauterine exposure to a maternal low-protein diet in the rat. Clin. Sci. 1998;94:373–381. doi: 10.1042/cs0940373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gilbert JS, et al. Maternal nutrient restriction in sheep: hypertension and decreased nephron number in offspring at 9 months of age. J. Physiol. 2005;565:137–147. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fishel RS, et al. Glucocorticoids induce angiotensin-converting enzyme expression in vascular smooth muscle. Hypertension. 1995;25:343–349. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cooper WO, et al. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:2443–2451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Khakoo AY, et al. Does the renin-angiotensin system participate in regulation of human vasculogenesis and angiogenesis? Cancer Res. 2008;68:9112–9115. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0851. [E26] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]