SUMMARY

Setting

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB) has emerged as a significant public health threat in South Africa.

Objective

To describe treatment outcomes and determine risk factors associated with unfavorable outcomes among MDR-TB patients admitted to the provincial TB referral hospital in KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa.

Design

Retrospective observational study of MDR TB patients admitted from 2000–2003.

Results

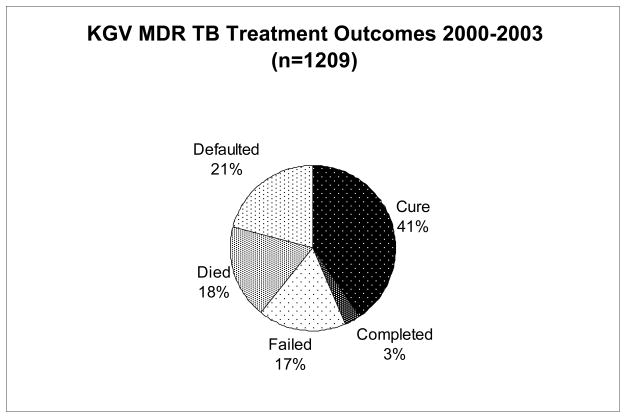

Of 1209 MDR TB patients with documented treatment outcomes, 491 (41%) were cured, 35 (3%) completed treatment, 208 (17%) failed treatment, 223 (18%) died and 252 (21%) defaulted. 52% of patients with known HIV status were HIV-infected. Treatment failure, death and default each differed in their risk factors. Greater baseline resistance (AOR 2.3–3.0), prior TB (AOR 1.7), and diagnosis in years 2001, 2002 or 2003 (AOR 1.9–2.3) were independent risk factors for treatment failure. HIV co-infection was a risk factor for death (AOR 5.6) and both HIV (AOR 2.0) and male sex (AOR 1.9) were risk factors for treatment default.

Conclusion

MDR TB treatment outcomes in KwaZulu-Natal were substantially worse than those published from other MDR TB cohorts. Interventions, such as individualized treatment, concurrent antiretroviral therapy and decentralized MDR TB treatment must be considered to improve MDR TB outcomes in this high HIV-prevalence setting.

Keywords: drug resistance, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, treatment outcomes, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB), defined as Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, is a rapidly-emerging disease that is characterized by difficult treatment and high rates of morbidity and mortality. There were an estimated 489,000 new cases of MDR TB worldwide in 2006, of which only a small fraction were ever diagnosed and received treatment.1 Although many countries have increased efforts to provide MDR TB treatment, the recent global emergence of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR TB; defined as MDR TB with resistance to a fluoroquinolone and either kanamycin, amikacin or capreomycin) has highlighted the possibility that it may be worse to provide inadequate treatment for MDR TB than to provide no treatment at all. To prevent mismanagement of MDR TB, the Green Light Committee (GLC) was established in 2000 to provide access to affordable treatment and quality control for national MDR TB programs. In 2006, however, fewer than 10% of patients treated for MDR TB received their care in GLC-approved programs.2 The quality of care in non-GLC programs is, therefore, of considerable concern.

The province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa has one of the largest burdens of MDR TB worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of 30 MDR TB cases per 100,000 population.3 Although the last systematic drug-resistance survey in KwaZulu-Natal in 2002 revealed only a 1.7% prevalence among new TB patients,4 the MDR TB caseload has risen nearly four-fold from 2002 to over 3000 cases in 2007.3 Additionally, the discovery of XDR TB in KwaZulu-Natal in 2005 has focused world attention on the drug-resistant TB epidemic in the province, and prompted investigation regarding its cause.5

Several important factors have contributed to the drug-resistant TB epidemic. The drug-susceptible TB program in KwaZulu-Natal has had high treatment default rates, which likely resulted in the creation of large numbers of MDR TB strains.4 The recent exponential rise in MDR TB cases, however, is difficult to explain by inadequate treatment alone. Primary transmission of MDR TB has probably also played a critical role.6 South Africa has the world’s largest number of HIV-infected individuals, and such patients are significantly more likely to develop active TB disease following initial infection.7 Factors which allow for ongoing MDR TB transmission, such as high rates of failure or default of MDR TB treatment, may have created the ideal milieu for MDR TB dissemination. Until 2007, King George V Hospital (KGV) in Durban had the only TB program in KwaZulu-Natal province with the capability of treating MDR TB patients. The program has long been under-resourced, and left to tackle the rapid rise in MDR TB caseload.

With these factors in mind, we sought to describe the treatment outcomes for MDR TB cases in this high-HIV prevalence setting at King George V Hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Specifically, we wanted to examine outcomes prior to the rapid rise in MDR TB caseload and the “discovery” of XDR TB in 2005. We also sought to identify risk factors for unfavorable outcomes of MDR TB treatment, in order to improve the program’s future performance.

METHODS

Study setting

KwaZulu-Natal is the most populous of South Africa’s nine provinces, with approximately 10 million people and the highest HIV prevalence in the country. King George V Hospital (KGV) is a 160-bed specialist TB referral center located in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal. Until 2007, KGV was the only source of treatment for MDR TB in the province. MDR TB cases from all regions of KwaZulu-Natal were referred to KGV for admission and management.

Study population

All patients with culture-proven MDR TB who were admitted to KGV between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2003 were eligible for inclusion. Patients with no documented treatment outcome were excluded from analysis.

Management of MDR TB

KGV used a modified standardized treatment regimen for MDR TB; on admission, patients were started on a regimen of kanamycin, ofloxacin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and ethionamide. Cycloserine was substituted for ethambutol if the isolate was known to be resistant to ethambutol. During the study period, all patients were admitted until they completed the intensive phase of treatment--usually four to six months. They were then discharged home with monthly follow-up in the outpatient clinic at KGV, and plans to complete another 18 months of oral treatment (pyrazinamide, ethambutol, ofloxacin and ethionamide). The continuation phase of therapy was not directly-observed. Sputum cultures and drug susceptibility testing (DST) were performed monthly for the duration of treatment.

Susceptibility Testing

DST was performed on all positive sputum cultures at the KGV laboratory using Lowenstein□Jensen media,8 with the following concentrations of antibiotics: isoniazid, 0.2 and 1 mg/L; rifampicin, 40 mg/L; ethambutol, 2 mg/L; streptomycin, 4 mg/L; ethionamide, 20 mg/L; kanamycin, 20 mg/L; ciprofloxacin, 5 mg/L; ofloxacin, 2.5 mg/L; and thiacetazone, 2 mg/L.

Data Collection

Baseline information, including demographics, HIV status (if known), prior history of TB, and most recent TB drug susceptibility results, was collected for all patients admitted to KGV and entered into a database. Information regarding treatment outcome was updated by the hospital data manager when patients were discharged from the hospital and periodically thereafter.

Treatment Outcome Definitions

MDR TB treatment outcome was classified according to standardized definitions.9 Cure was defined as completion of treatment while remaining consistently culture-negative (with at least five results) in the final 12 months of treatment. Treatment completion was defined as completion of the entire treatment course but without bacteriologic documentation of cure. Treatment failure was defined as having more than one positive culture in the last 12 months of treatment, with a minimum of five monthly cultures performed during the last 12 months. Treatment was also considered to have failed if one of the last three cultures taken during treatment was positive, or if the patient was persistently culture positive and a clinical decision was made to terminate treatment. Default was defined as treatment interruption for 2 or more consecutive months for any reason. Death was defined as death from any cause during MDR TB treatment.

For the purposes of analysis, “unfavorable outcome” was defined as treatment failure, default or death from any cause. Patients who were cured or who successfully completed treatment were considered to have had a “favorable outcome.”

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes were identified for all patients and were described using simple frequencies, medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Bivariate analysis was performed to examine for associations between specific baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes using chi-square tests. The baseline characteristics examined were age (categorized as≤20, 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, and≥51), sex, HIV status, admission year, previous history of treatment for TB, and employment status. The TB drugs to which the initial isolate was resistant was also examined in several ways: number of drugs (categorized as 2, 3, 4 or ≥5 drugs), resistance to specific drugs (e.g., ethambutol), and combinations of drug resistance (e.g. isoniazid plus rifampin plus ethambutol plus streptomycin). Variables with a p value less than 0.1 on bivariate analysis were then incorporated into a multivariate logistic regression model for the composite “unsuccessful outcome” as well as for individual unsuccessful outcomes: “treatment failure,” “death” and “default.” Subjects with each of these unsuccessful outcomes were compared to those who had had a favorable outcome. Models were built forward and backward in stepwise fashion as well as with all variables forced into the model.

Because HIV test results were not available for more than 40% of subjects, we performed a sensitivity analysis, imputing either positive or negative HIV results for the missing patients, to determine the influence of missing HIV data on the effect size of other variables in our model.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees at the University of KwaZulu-Natal and Montefiore Medical Center.

RESULTS

From 2000–2003, a total of 1261 patients diagnosed with MDR TB were admitted to King George V Hospital (KGV) in Durban. Fifty-two (4.1%) patients had no recorded final outcome and were excluded from the final analysis. Baseline characteristics for the remaining 1209 patients are shown in Table 1. Of these patients, 472 (39%) were women and the median age was 33 years (IQR: 26–41). HIV status was available for 699 patients (58%), of whom 362 (52%) were HIV-positive. Information about prior TB was available for 1191 (99%) patients, of whom 959 (81%) had a history of previous TB. At baseline, 26% of patients were resistant only to isoniazid and rifampin, while 32%, 18%, and 23% of patients were resistant to 3, 4 and 5 or more drugs respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (N=1209)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Total N | 1209 |

| Female | 472 (39.0) |

| Age, years: median (IQR) | 33.0 (26–41) |

| Age <20 years | 120 (9.6) |

| Age 21–30 years | 375 (32.2) |

| Age 31–40 years | 373 (30.9) |

| Age 41–50 years | 233 (18.4) |

| Age >50 years | 100 (8.6) |

| HIV status available | 699 (57.8) |

| HIV-positive | 362 (51.8) |

| HIV-negative | 337 (48.2) |

| Prior TB treatment status available | 1191 (98.5) |

| Previous TB | 959 (80.5) |

| No previous TB | 232 (19.5) |

| # resistant TB drugs: median (range) | 3 (2–9) |

| Resistant to 2 drugs | 315 (26.1) |

| Resistant to 3 drugs | 391 (32.3) |

| Resistant to 4 drugs | 223 (18.4) |

| Resistant to ≥5 drugs | 280 (23.2) |

| Employed | 277 (22.9) |

| Unemployed | 704 (58.2) |

| Unknown employment status | 228 (18.9) |

(IQR=interquartile range)

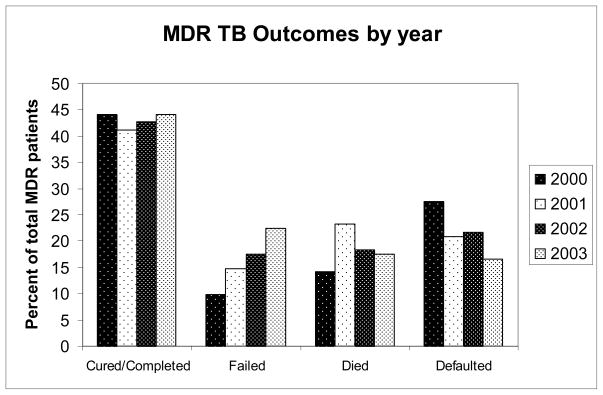

Of the 1209 patients with known MDR TB treatment outcomes, 491 (41%) were cured, 35 (3%) completed treatment, 208 (17%) failed treatment, 223 (18%) died while on treatment, and 252 (21%) defaulted on treatment (Figure 1). Overall, 526 (44%) had a favorable outcome (cure or completed), while 683 (56.5%) had an unfavorable outcome (failed, died or defaulted). There was no significant difference in the percentage of patients with a favorable treatment outcome from 2000 to 2003 (p=0.42), however there was a trend towards more patients with treatment failure and fewer with default in 2003, as compared with 2000 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

MDR TB Treatment outcomes 2000–2003

Figure 2.

MDR TB final treatment outcomes by year of diagnosis.

HIV infection, resistance to 3 or 5 TB drugs, resistance to ethambutol, and age between 31 and 40, were all risk factors for the composite “unfavorable” outcome, but analysis of individual unfavorable outcomes revealed that each individual unfavorable outcome (i.e. failure death or default) had unique, specific risk factors. No one risk factor was found for all three. Thus, we present risk factor data from multivariable analysis for each outcome separately (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted predictors of unfavourable outcomes

| Failed Treatment | Died | Defaulted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | n (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | n (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Previous TB | 51 (25) | 1.7 (1.0–2.8)* | 160 (17) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | -- | -- |

| 2001 | 38 (15) | 2.0 (1.1–3.7)* | 60 (23) | 1.2 (0.6–2.5) | 54 (21) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) |

| 2002 | 63 (18) | 1.9 (1.1–3.4)* | 66 (18) | 1.5 (0.7–3.0) | 78 (22) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) |

| 2003 | 87 (23) | 2.3 (1.3–4.1)† | 68 (18) | 1.5 (0.7–3.0) | 64 (17) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) |

| 3 Resistant drugs | 78 (20) | 2.3 (1.3–4.1)† | -- | -- | 89 (23) | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) |

| 4 Resistant drugs | 29 (13) | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | -- | -- | 40 (18) | 1.2 (0.6–2.7) |

| 5+ Resistant drugs | 71 (25) | 3.0 (1.5–5.7)† | -- | -- | 47 (17) | 0.7 (0.3–1.9) |

| Ethambutol | 143 (20) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 138 (20) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | -- | -- |

| HIV | -- | -- | 90 (25) | 5.6 (3.3–9.4)† | 81 (22) | 2.0 (1.3–3.1) † |

| Male sex | -- | -- | -- | -- | 175 (24) | 1.9 (1.2–3.1) † |

| Age 21–30 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 74 (20) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) |

| Age 31–40 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 91 (24) | 1.5 (0.7–3.2) |

| Age 41–50 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 44 (19) | 0.8 (0.4–1.8) |

| Age >50 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 18 (18) | 0.9 (0.3–2.7) |

(Dash denotes non-significance on bivariate analysis)

p<0.05

p<0.01

For treatment failure, previous TB treatment (AOR 1.7), diagnosis in years 2001 (AOR 2.0), 2002 (AOR 1.9) and 2003 (AOR 2.3), and resistance to either 3 or 5 TB drugs (AORs 2.3 & 3.0, respectively) were all significant independent risk factors on multivariable analysis. In contrast, the only significant risk factor for death on multivariate analysis was HIV co-infection (AOR 5.6). Previous TB and diagnosis in 2001 were risk factors for death on bivariate analysis, but neither remained significant in the multivariable model. For treatment default, many factors were significant on bivariate analysis, but on multivariate analysis, only HIV (AOR 2.0) and male sex (AOR 1.9) remained significant risk factors. Full details of adjusted odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p-values for these factors are displayed in Table 2.

Because HIV was a major risk factor for death and default, we performed sensitivity analysis to determine what influence, if any, the more than 40% of patients with unknown HIV status would have on other risk factors. Imputation of positive or negative HIV results did not significantly affect the direction or magnitude of effect of the other covariates in each the models (data not shown). Even when negative results were imputed for all of the subjects with unknown HIV status, HIV infection remained a very strong predictor of death (p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe treatment outcomes from the largest cohort of MDR TB patients reported from a high HIV prevalence setting to date. Compared with published reports from low HIV prevalence settings, treatment outcomes in our cohort were very poor, with fewer than 45% of patients achieving cure or treatment completion.10 The unsuccessful outcomes were evenly divided among death, treatment failure and default, but the risk factors for each of these outcomes varied. HIV co-infection was a major risk factor for death and default, but not treatment failure. Conversely, a greater number of resistant drugs, prior TB treatment, and later year of diagnosis were risk factors for treatment failure, but not for death or default. Efforts to improve MDR TB outcomes in this setting must therefore be multifaceted to address such differing risks.

MDR TB is a marker of a TB control program’s inability to adequately manage drug-susceptible TB. The South African TB program has been severely under-resourced to handle the 3-fold rise in TB case load over the past 15 years. As a result, there is now a massive MDR TB epidemic in KwaZulu-Natal, with a prevalence of more than 30 cases per 100,000 population.3, 11 Because culture and DST are only performed for retreatment cases and patients failing first-line therapy, these numbers are likely a substantial underestimate of the actual current MDR TB burden.

Fewer than half of the subjects in our cohort achieved cure or treatment completion, making these treatment completion rates among the worst seen in the published literature. A recent meta-analysis examined treatment outcomes from 34 published MDR TB cohorts in 20 countries.10 The pooled treatment success rate was 62% (range 40%–79%) and other published cohorts, such as from California, USA12 and a DOTS-Plus program in Tomsk, Russia,13 also demonstrate treatment success rates of greater than 65%.

Although most of the published MDR TB cohorts are from low HIV-prevalence countries, the inferior outcomes in KwaZulu-Natal cannot be explained by HIV alone. The “unfavorable outcomes” in our cohort were almost evenly divided among treatment failures, deaths, and defaults. Although these three categories are typically combined and considered together, our data suggest that each differed in its risk factors.

The principal risk factor for failure was baseline resistance to a greater number of TB medications and nearly 25% of patients in this study were resistant to 5 or more drugs. Current MDR TB guidelines14 emphasize using regimens which contain at least four susceptible TB drugs. The modified, standardized treatment regimen at KGV may, therefore, have been inadequate for patients with such severe drug resistance. Given the high rates of treatment failure in our study, consideration should be given to either individualizing treatment regimens or increasing the number of medications in the standardized regimen.

Our study took place before the availability of antiretroviral therapy in the public sector in South Africa and it is thus, no surprise that HIV was a risk factor for death. Efforts to reduce mortality among MDR TB patients in high HIV prevalence settings must include integration of antiretroviral therapy with second-line TB therapy.15

The risk factors for default, HIV-infection and male sex, suggest two ends of a spectrum for why individuals default. A large proportion die, but the treatment program lacks the resources to trace patients who miss clinic appointments.16, 17 Others improve sufficiently to once again seek employment, often in distant cities or provinces. Regardless of the reasons for defaulting, however, the MDR TB treatment program must have the resources to track and prevent defaults, as treatment interruption is a significant cause for amplifying resistance. As a centralized treatment program, the KwaZulu-Natal program is unable to trace defaulters, or even provide directly-observed therapy in the continuation phase, for patients’ homes and communities are often hundreds of kilometers away. To reduce the number of MDR TB defaults, decentralization of the MDR TB treatment should be considered, either by creating community-based treatment programs or satellite inpatient centers.18–20

Although this cohort demonstrates the burden of MDR TB in KwaZulu-Natal, our study is not without limitations. First, the study was performed retrospectively, relying upon complete and accurate entry of treatment outcomes. Although more than 95% of patients did have a final outcome reported, we were unable to confirm the accuracy of the data. Second, the KGV database provides no information on the use of surgical pulmonary resection. An important adjunctive treatment for localized disease, this procedure is available to certain patients admitted to KGV and may have been an important predictor of treatment success.21, 22 Third, we were unable to demonstrate the development of XDR TB while receiving MDR TB treatment because end-of-treatment drug susceptibility patterns were not available. Despite high rates of drug resistance in our cohort, only 11 patients had XDR TB on admission. Given the recent alarming rates of XDR TB in KwaZulu-Natal5 and the demonstration of nosocomial spread of XDR TB,6 it is likely that the source of the current XDR TB epidemic was one of a few XDR TB cases seen before 2005 and was the result of a failing MDR TB treatment program. Finally, nearly 40% of the patients in our cohort were not tested for HIV. Public access to antiretrovirals was not available in South Africa until 2004 and many patients prior to this were reluctant to be tested for HIV. HIV, however, remained a significant predictor of death even when all of the unknown results were imputed to be negative.

The incidence of MDR TB continues to increase in KwaZulu-Natal, and although some of this rise may be attributed to increased use of sputum culture and drug-susceptibility testing, the additional cases will further tax the TB control program. Only by strengthening the MDR program with increased staff and resources, providing integrated treatment for HIV, and addressing the many different risk factors for poor treatment outcomes, will South Africa be able to control this dire and growing epidemic.

References

- 1.Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world – Report No. 4, The WHO/IUATLD global project on anti-tuberculosis drug resistance surveillance. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Global Tuberculosis Control 2008: Surveillance, Planning, Financing. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buthelezi SSS. Situational Analysis of TB Drug Resistance in KwaZulu-Natal Province: Republic of South Africa. 2nd Meeting of the Global XDR TB Task Force; Geneva, Switzerland. April 9, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weyer K, Lancaster J, Brand J, Van der Waltm MJL Medical Research Council of South Africa. Technical report to the Department of Health. Jun, 2003. Survey of tuberculous drug resistance in South Africa, 2001–2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi NR, Moll A, Sturm AW, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis as a cause of death in patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV in a rural area of South Africa. Lancet. 2006;368:1575–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews JR, Gandhi NR, Moodley P, et al. Exogenous reinfection as a cause of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in rural South Africa. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2008;198:1582–9. doi: 10.1086/592991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selwyn PA, Hartel D, Lewis VA, et al. A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. The New England journal of medicine. 1989;320:545–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903023200901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleeberg HH, Koornhof HJ, HP . Susceptibility testing. In: Nel EE, Kleeberg HH, Gatner EMS, editors. Laboratory manual of tuberculosis methods. 2. Pretoria, South Africa: South African Medical Research Council; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laserson KF, Thorpe LE, Leimane V, et al. Speaking the same language: treatment outcome definitions for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:640–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orenstein EW, Basu S, Shah NS, et al. Treatment outcomes among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2009;9:153–61. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zager EM, McNerney R. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee R, Allen J, Westenhouse J, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in california, 1993–2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:450–7. doi: 10.1086/590009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keshavjee S, Gelmanova IY, Farmer PE, et al. Treatment of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Tomsk, Russia: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2008;372:1403–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. WHO/HTM/TB/2008.402. Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Donnell MR, Padayatchi N, Master I, Osburn G, Horsburgh CR. Improved Early Results for Patients with Extensively Drug Resistant Tuberculosis and HIV in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009 (in press) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holtz TH, Lancaster J, Laserson KF, Wells CD, Thorpe L, Weyer K. Risk factors associated with default from multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment, South Africa, 1999–2001. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng EH, Emenyonu N, Bwana MB, Glidden DV, Martin JN. Sampling-based approach to determining outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy scale-up programs in Africa. JAMA. 2008;300:506–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padayatchi N, Friedland G. Decentralised management of drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR- and XDR-TB) in South Africa: an alternative model of care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:978–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scano F, Vitoria M, Burman W, Harries AD, Gilks CF, Havlir D. Management of HIV-infected patients with MDR- and XDR-TB in resource-limited settings. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:1370–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitnick C, Bayona J, Palacios E, et al. Community-based therapy for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Lima, Peru. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348:119–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HJ, Kang CH, Kim YT, et al. Prognostic factors for surgical resection in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:576–80. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00023006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pomerantz BJ, Cleveland JC, Jr, Olson HK, Pomerantz M. Pulmonary resection for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2001;121:448–53. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.112339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]