Abstract

Protein arginine N-methyltransferase (PRMT) dimerization is required for methyl group transfer from the cofactor S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) to arginine residues in protein substrates, forming S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (AdoHcy) and methylarginine residues. In this study, we use Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) to determine dissociation constant (KD) values for dimerization of PRMT1 and PRMT6. By attaching monomeric Cerulean and Citrine fluorescent proteins to their N-termini, fluorescent PRMTs are formed that exhibit similar enzyme kinetics to unconjugated PRMTs. These fluorescent proteins are used in FRET-based binding studies in a multi-well format. In the presence of AdoMet, fluorescent PRMT1 and PRMT6 exhibit 4- and 6-fold lower dimerization KD values, respectively, than in the presence of AdoHcy, suggesting that AdoMet promotes PRMT homodimerization in contrast to AdoHcy. We also find that the dimerization KD values for PRMT1 in the presence of AdoMet or AdoHcy are, respectively, 6- and 10-fold lower than the corresponding values for PRMT6. Considering that the affinity of PRMT6 for AdoHcy is 10-fold higher than for AdoMet, PRMT6 function may be subject to cofactor-dependent regulation in cells where the methylation potential (i.e., ratio of AdoMet to AdoHcy) is low. Since PRMT1 affinity for AdoMet and AdoHcy is similar, however, a low methylation potential may not affect PRMT1 function.

Keywords: PRMT1, PRMT6, Förster resonance energy transfer, dimerization, methylation potential

Introduction

Protein arginine N-methyltransferases (PRMTs) are a family of enzymes that transfer methyl groups from the co-substrate S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) onto the terminal guanidino nitrogen atoms on arginine residues within protein substrates, resulting in the formation of methylarginine residues and S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (AdoHcy).1 All PRMTs produce ω-NG-monomethylarginine (MMA) residues as an intermediate to the formation of either asymmetric ω-NG,NG-dimethylarginine (aDMA) residues, referred to as Type I activity, or ω-NG,N′G-dimethylarginine (sDMA) residues, referred to as Type II activity. Currently, the eukaryotic PRMT family is comprised of nine enzymes that share a set of highly conserved catalytic core sequences comprised of an N-terminal five-strand twisted β-sheet for AdoMet binding, and a C-terminal β-barrel that together form a cleft for protein substrate binding.2–6 PRMT1, 2, 3, co-activator associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1/PRMT4), 6, and 8 exhibit Type I activity,7–13 PRMT5 exhibits Type II activity.14,15 Conflicting reports suggest that PRMT7 falls in the later category.16–18 PRMT9(4q31) activity has yet to be determined.

Structures of PRMTs reveal a common mode of dimerization between catalytic subunits.2–6 Each subunit contains a dimerization helix-turn-helix that protrudes from the C-terminal β-barrel and rests upon the N-terminal AdoMet binding domain of the other subunit, forming a central anionic cavity with two opposing active sites. Removing the dimerization helix-turn-helix from Rmt1p and PRMT1 has been shown to eliminate homodimerization, AdoMet binding, and methyltransferase activity.3,4 More recently, Higashimoto et al.19 have shown that CARM1 is phosphorylated on S229 on the dimerization helix-turn-helix, and a phosphoserine mimic S229E mutation significantly reduced AdoMet binding, enzyme activity in vitro, homodimerization, and CARM1-mediated transactivation of estrogen receptor-dependent transcription.19 Taken together these results underscore the important relationship between PRMT homodimerization and methyltransferase activity. Although PRMT1 and 6 possess 60% sequence similarity in the dimer arm that may imply a similar structure-function relationship, the physiological role of homodimerization has not yet been demonstrated for PRMT6.

PRMT 1–8 have been successfully expressed in mammalian cells as green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusions, and for the most part behave similarly to their endogenous counterparts.12,20 In this study, we use fluorescent proteins to quantify homodimerization for recombinant human PRMT1 and PRMT6 to observe cofactor-dependent effects on protein binding using of Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). Through FRET, light is absorbed and transferred non-radiatively between two fluorophores, and the acceptor fluorophore emits transferred energy at its own fluorescence emission maximum.21 The efficiency of FRET is contingent upon factors such as the degree of overlap between donor emission and acceptor absorption spectra (i.e., integral overlap), as well as the distance between donor and acceptor fluorophores.

In the present study, PRMT1 and PRMT6 are made with either monomeric Cerulean (mCer) or monomeric Citrine (mCit) fluorescent proteins on their N-termini. These fluorescent PRMTs exhibit methyltransferase activity (i.e., kinetic parameters) similar to that observed for their nonfluorescent counterparts. Using fluorescent PRMT pairs, binding studies are employed to calculate the dissociation constant (KD) values of PRMT1 and PRMT6 homodimers in the presence and absence of either AdoMet or AdoHcy. Based on the observed differences in homodimer affinities under various conditions, we provide a model for how some PRMTs may be regulated by intracellular cofactor concentrations.

Results

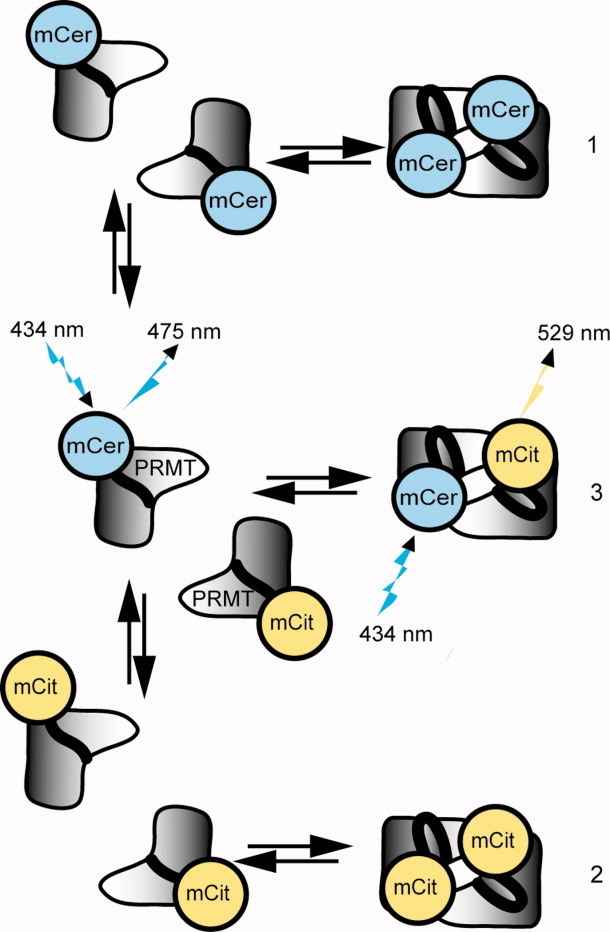

This study focuses on the quantification of PRMT homodimerization using FRET. We create fusion proteins of PRMT1 and PRMT6 bearing either mCer or mCit on their N-termini to measure FRET interactions between subunits using the absorption maximum at 434 nm for mCer and the emission maximum at 529 nm for mCit,22 thus providing a simple method for quantifying homodimer binding affinity. The FRET response is produced when a mCer-PRMT dimerizes with a mCit-PRMT (Fig. 1). In the absence of this pair forming, all of the radiative energy from mCer emits at its own emission maximum at 475 nm, and FRET will not occur. Implicit in Figure 1, mCer-PRMT and mCit-PRMT homodimers must dissociate into monomers and then re-associate into a mCer/mCit-PRMT dimer to observe a FRET signal.

Figure 1.

Formation of PRMT FRET pairs. Upon addition of mCer-PRMT (1) and mCit-PRMT (2), the populations of homodimers will dissociate into monomers and recombine into mixed homodimers, bringing mCer and mCit in close proximity as an active FRET pair (3). When excited with 434-nm light, only (3) will produce a FRET signal at 529 nm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Fluorescent PRMT spectral properties and enzymatic activities

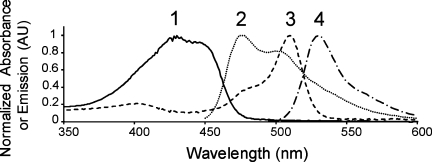

Prior to performing FRET experiments, all fluorescent fusion proteins are investigated for appropriate spectral characteristics and enzymatic activity. The absorption and emission spectra for fluorescent PRMTs are recorded from 450 to 650 nm using a 434-nm excitation wavelength, and normalized to a value of 1.0 for comparison (Fig. 2). The absorption and emission wavelengths for all conjugated proteins are consistent with those of unconjugated mCer and mCit.23,24 These data demonstrate that the fluorescent components of the conjugated PRMTs are properly folded and possess functional fluorophores.

Figure 2.

Normalized absorption and emission spectra for mCerulean and mCitrine-PRMTs. Normalized spectra are overlaid for mCer-PRMT1 absorption (1) and emission (2), as well as mCit-PRMT1 absorption (3) and emission (4). The emission spectra are collected for both mCer-PRMTs and mCit-PRMTs using a 434-nm excitation wavelength. Fluorescent PRMT6 produces identical spectra, whereas PRMT1 and PRMT6 without attached fluorophores do not possess intrinsic fluorescence within this range using 434-nm excitation (data not shown).

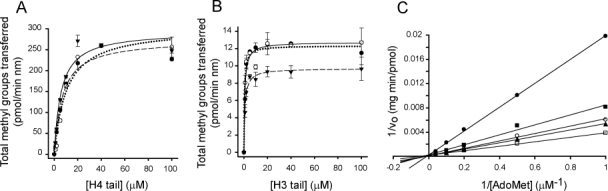

Using a UPLC tandem mass spectrometry assay (described in Materials and Methods) the activities of mCer- and mCit-PRMTs are compared to those of their respective unconjugated proteins (Fig. 3). The apparent Vmax and KM values (Table I) are similar for respective fluorescent and nonfluorescent PRMTs, suggesting that the PRMT component of each fluorescent fusion protein is properly folded, and that the fluorescent attachment has little or no effect on the activity of the conjugated PRMT.

Figure 3.

Activities of PRMT1 and PRMT6 with and without mCerulean or mCitrine and double-reciprocal plot of PRMT1 product inhibitor analysis. The initial velocity of reactions is determined as described in the Materials and Methods section. (A) Methylation assays using PRMT1 (•), mCit-PRMT1 (○), or mCer-PRMT1 (▾) with increasing concentrations of the H4 tail peptide are shown. (B) Methylation assays using PRMT6 (•), mCit-PRMT6 (○), or mCer-PRMT6 (▾) with increasing concentrations of the H3 tail peptide are shown. The initial rate is calculated as pmol per min per nanomole of enzyme to accommodate the differences in molecular weights between fluorescent and nonfluorescent PRMTs, and kinetic parameters are listed in Table I. (C) In the presence of a constant 80-μM H4 tail peptide concentration, variable concentrations of 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10, and 25 μM AdoMet are incubated in methylation buffer. These reactions are repeated in the presence of fixed AdoHcy concentrations of 0 μM (□), 0.5 μM (▴), 1.0 μM (○), 5.0 μM (▪), and 20 μM (•). The pattern of intersecting lines on the y-axis is indicative of competitive inhibition for the product inhibitor AdoHcy.

Table I.

Apparent Kinetic Parameters for Fluorescent and Nonfluorescent PRMTs

| Enzyme | Substrate | Vmax (pmol/min nmol)a | KM (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRMT1 | H4 tail | 274.5 (5.9) | 6.9 (0.2) |

| mCit-PRMT1 | H4 tail | 302 (26) | 10.3 (1.9) |

| mCer-PRMT1 | H4 tail | 294.1 (6.2) | 5.8 (0.1) |

| PRMT6 | H3 tail | 13.2 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.1) |

| mCit-PRMT6 | H3 tail | 12.8 (0.4) | 0.5 (0.1) |

| mCer-PRMT6 | H3 tail | 9.7 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.3) |

Vmax is calculated as pmol per min per nmol of enzyme to account for mass differences between fluorescent and nonfluorescent PRMTs. Numbers in parentheses represent standard deviations.

FRET from fluorescent PRMT homodimerization

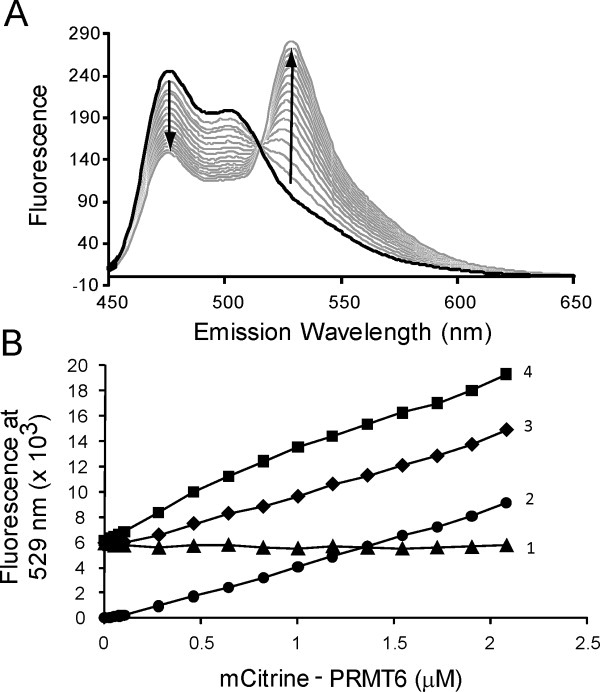

To test the feasibility of using FRET to measure PRMT homodimerization as outlined in Figure 1, up to 3.5-μM mCit-PRMT1 is titrated into a solution of 1.0-μM mCer-PRMT1 while scanning the fluorescence emission wavelengths from 450 to 650 nm [Fig. 4(A)]. The initial spectrum of mCer-PRMT1 is consistent with the spectrum of mCer alone.24 As mCit-PRMT1 is titrated into mCer-PRMT1, a peak appears at the emission maximum for mCit-PRMT1 (529 nm). For each increase in mCit-PRMT1 concentration, a corresponding drop is observed in mCer-PRMT1 emission at 475 nm greater than that which can be accounted for by dilution alone. Energy transfer from 434 nm to 529 nm is demonstrated by an increase in 529-nm fluorescence with a concomitant decrease in 475-nm fluorescence (i.e., donor emission). These spectral changes are a direct demonstration of the FRET phenomenon. Similar results are observed for fluorescent PRMT6 proteins (data not shown).

Figure 4.

mCerulean and mCitrine-PRMTs produce FRET. (A) A 1.0-μM solution of mCer-PRMT1 is added to a cuvette to a final volume of 1.5 mL. mCit PRMT1 is then titrated for sixteen 10-μL additions into the sample, covering a concentration range of 0–3.5 μM. After each addition, the solution is allowed to stir for 2 min prior to scanning for wavelength emission between 450 and 650 nm using a Varian benchtop fluorometer as described in the Materials and Methods section. (B) The emission at 529 nm is measured using a Biotek micro-plate reader as described in the Materials and Methods section. The background fluorescence from 0.5-μM mCer-PRMT6 alone (▴) remains constant, and the background fluorescence contributions from 0- to 2.08-μM mCit-PRMT6 alone (•) increases linearly with increasing protein. The combination of a fixed concentration of mCer-PRMT6 (0.5 μM) with varying concentrations of mCit-PRMT6 (▪) shows greater fluorescence intensity than the sum of both background signals (♦).

When excited using 434 nm light, both mCer- and mCit-PRMTs are able to produce 529 nm emissions not attributable to FRET. To ensure the signal produced from protein mixing is due to FRET and not background fluorescence, a multi-well plate assay is performed with the inclusion of background controls [Fig. 4(B)]. The sum of mCer- and mCit-PRMT6 fluorescence emissions (i.e., total background signal) is less than the fluorescence observed when the two fluorescent PRMTs are combined, thus demonstrating that additional fluorescence at 529 nm is produced from FRET as a result of PRMT6 homodimerization. These background controls are also employed in FRET experiments with fluorescent PRMT1 proteins (data not shown).

PRMT dissociation constants

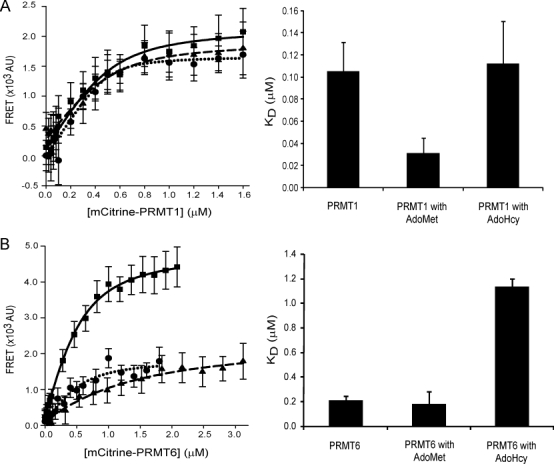

We determine the KD values for PRMT dimerization by varying the mCit-PRMT concentration with a fixed mCer-PRMT concentration. A broad range of mCit-PRMT concentrations are initially used to estimate a KD value for each set of experimental conditions. Each experiment is then repeated with an appropriate range of mCit-PRMT concentrations that produce data points above and below each estimated KD value to best fit the data in subsequent binding curves (Fig. 5). We note that using the same mCit concentration range for all experimental conditions (e.g., with or without cofactor) would result in inaccurate KD value estimation. Fluorescence readings are acquired using multi-well plate format and the data fit to Eq. (1), producing a hyperbolic fit for equimolar binding.25 The background-corrected FRET signal is proportional to the ratio of the fluorescent PRMT FRET pair concentration ([Dimer]) to the total PRMT concentration ([PRMT]total), which can also be expressed in terms of the concentrations of PRMTs conjugated to mCer ([mCer]) and mCit ([mCit]), as well as the KD value. Based on the kinetic data presented above, we make the assumption that the dimerization KD values are the same irrespective of the fluorescent attachment. It is important to note that the KD value is not calculated as ½ of the FRET maximal signal, but rather as a function of best fit using Eq. (1), which takes into account both monomeric and dimeric PRMT populations.

Figure 5.

Steady-state FRET binding for fluorescent PRMTs. FRET measurements are performed as described in the Materials and Methods section between mCer- and mCit-PRMTs. Protein binding curves are shown for (A) PRMT1 (▪), PRMT1 with 500-μM AdoMet (•), PRMT1 with 20-μM AdoHcy (▴), (B) PRMT6 (▪), PRMT6 with 500-μM AdoMet (•) and PRMT6 with 20-μM AdoHcy (▴). All experimental groups contain 0.5 μM mCer-PRMT1 or mCer-PRMT6. The dissociation constants derived from protein binding curves for fluorescent PRMT1 and PRMT6 are shown with their standard deviations.

| (1) |

The calculated KD values for all multi-well FRET assays are listed in Table II. The presence of AdoMet decreases the KD of dimerization for PRMT1 by 4-fold compared to PRMT1 alone or with AdoHcy. In contrast, the presence of AdoHcy increases the KD of dimerization for PRMT6 by 6-fold compared to PRMT6 alone or with AdoMet. Interestingly, the KD values for both PRMT1 and PRMT6 are greater in the presence of AdoHcy than in the presence of AdoMet. These results demonstrate that the presence of cofactors can differentially affect PRMT dimerization.

Table II.

Dissociation Constants for Fluorescent PRMT1 and PRMT6 with and without Cofactor

| Enzyme | Cofactor | KD (nM)a |

|---|---|---|

| PRMT1 | — | 110 (26) |

| PRMT1 | AdoMet | 30 (14) |

| PRMT1 | AdoHcy | 110 (38) |

| PRMT6 | — | 210 (34) |

| PRMT6 | AdoMet | 180 (104) |

| PRMT6 | AdoHcy | 1100 (67) |

Numbers in parentheses represent standard deviations.

PRMT6 dimerization appears to be more sensitive to the presence of AdoHcy than PRMT1. Thus, we compare AdoHcy dissociation constant (KI) values for PRMT1 and PRMT6 to expose a possible regulatory mechanism for PRMT-selective inhibition. We use the mass spectrometry-based assay to determine the KI value for PRMT1, since we have previously established the AdoHcy KI value for PRMT6.26 As expected the double-reciprocal plot of the inhibition data reveal a series of lines increasing in slope with increasing AdoHcy concentrations that intersect on the y-axis [Fig. 3(C)], indicating that the inhibition is competitive. The AdoHcy KI = 5.8 ± 0.5 μM for PRMT1, which is 4-fold higher than the KI value previously calculated for PRMT6.26 Therefore, not only is PRMT6 dimerization more sensitive to AdoHcy concentration than PRMT1 dimerization, but the enzyme activity is more sensitive as well.

PRMT dimer contribution to FRET

PRMT1 has been shown to form high order oligomers under purification and crystallographic conditions.3,4 To investigate whether FRET signals from fluorescent PRMT1 and PRMT6 proteins are attributed to complexes larger than dimers under our experimental conditions, we measure the efficiency of energy transfer between fluorophores using excitation at 434 nm and emission at 475 nm to capture the quenching of mCer-PRMT fluorescence caused by mCit-PRMT, thus allowing us to assess the oligomeric contribution to FRET. Here, efficiency (E) is defined as the magnitude of energy transfer from donor to acceptor [Eq. (2)], where DA is the 475-nm emission of the donor/acceptor pair, and D is the 475-nm emission of the donor alone.27

| (2) |

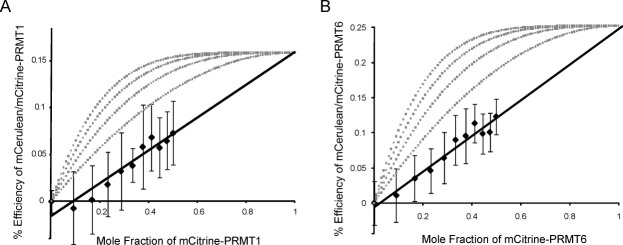

As the concentration of mCit-PRMT increases, more donor/acceptor pairs form and the efficiency increases. Efficiency increases are linearly related to the mole fraction of the FRET acceptor when dimeric complexes are formed, which is observed for PRMT1 and PRMT6 as shown in Figure 6 where efficiency data fit linearly with R2 values of 0.91 and 0.96, respectively. Unlike the case for dimers, the contribution to FRET for larger oligomeric complexes shows a hyperbolic curve when efficiency is plotted against the mole fraction of FRET acceptor. Efficiency curves for various oligomers are plotted (Fig. 6) using a simplified binomial model [Eq. (3)] where %Q is the quenching from FRET, α is an efficiency constant unique to each FRET system, PA is the mole fraction of acceptor, and n is the number of oligomers.28,29 Our PRMT1 and PRMT6 efficiency data support the formation of dimer FRET complexes.

Figure 6.

FRET efficiency subunit contribution. Up to 1.0-μM mCit-PRMT1 or -PRMT6 is mixed with 1.0-μM mCer-PRMT1 or -PRMT6 and 475-nm emissions were collected. (A) Efficiency measurements for the mCer/mCit-PRMT1 FRET pair indicate a linear relationship when plotted against mole fraction of mCit-PRMT1. (B) Similar results are shown for the mCer/mCit-PRMT6 FRET pair. Both PRMT1 and PRMT6 theoretical efficiencies are obtained by extrapolating to a mole fraction of one. Percent (%) efficiencies for trimer, tetramer, pentamer, and hexamer are modeled from right to left for both enzymes and plotted in gray.

| (3) |

Quenching is extrapolated to the mole fraction of one for PRMT1 and PRMT6 to estimate maximum efficiency of 16% and 25%, respectively (Fig. 6). Extrapolated maximal efficiencies for PRMT1 and PRMT6 demonstrate a higher efficiency energy transfer for PRMT6. It is possible that the mCer/mCit portions of the fusion proteins are held in closer proximity for PRMT6 than for PRMT1.

Dimer subunit specificity

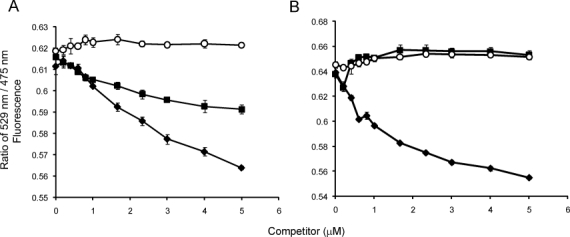

To demonstrate that FRET pairs are established through the binding of two PRMT subunits, nonfluorescent PRMTs are used to disrupt FRET from mCer/mCit-PRMTs. In these experiments, increasing concentrations of nonfluorescent PRMT1 and PRMT6 are mixed with FRET pairs and fluorescence is measured at emission wavelengths of 475 nm and 529 nm to capture the change in energy transfer. As shown in Figure 7(A), the presence of nonfluorescent PRMT1 results in a concentration-dependent decrease in energy transfer between mCer/mCit-PRMT1, whereas the addition of buffer has no effect. Interestingly, nonfluorescent PRMT6 also disrupts the mCer/mCit-PRMT1 FRET pair, but to a lesser extent. When nonfluorescent PRMT6 is added to mCer/mCit-PRMT6 [Fig. 7(B)], the energy transfer between the FRET pair is decreased in a concentration-dependent manner. The addition of buffer or nonfluorescent PRMT1 does not disrupt the mCer/mCit-PRMT6 FRET. We can conclude from these experiments that PRMT1 and PRMT6 can compete with their own FRET pairs, demonstrating specificity of the FRET signals.

Figure 7.

Nonfluorescent PRMT competition with FRET pairs. (A) The 529 nm/475 nm ratio of the mCer/mCit-PRMT1 FRET pair is plotted with addition of buffer (○), increasing nonfluorescent PRMT6 (▪), and increasing nonfluorescent PRMT1 (♦) concentrations. (B) The 529 nm/475 nm ratio of the mCer/mCit-PRMT6 FRET pair is also plotted with addition of buffer (○), increasing nonfluorescent PRMT1 (▪), and increasing nonfluorescent PRMT6 (♦) concentrations. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Given that PRMT6 can weakly disrupt PRMT1 FRET pairs, we proceeded to test for PRMT1/PRMT6 heterodimerization. Varying concentrations of mCit-PRMT6 with a fixed mCer-PRMT1 concentration are used to detect FRET consistent with dimerization. Although a weak FRET signal is detected above background (Supporting Information Fig. S1), the protein concentrations required to reach a saturation point adequate to fit a dissociation curve and calculate a KD value are not achievable under our assay conditions. PRMT1/6 heterodimers are not likely to compose an appreciably large population in vivo given the relatively tight association between their respective homodimers (Table II).

Discussion

FRET to measure PRMT homodimerization

Spectroscopic techniques utilizing FRET provide a useful and accurate means of quantifying protein–protein interactions.22 Until now this technique has not been applied to the measurement of PRMT homodimers. In this work, we show that PRMT dimerization can indeed be measured under various conditions using FRET. The major advantage of this technique is its compatibility with a multi-well plate format so that uniform sample equilibration can be achieved over multiple PRMT concentrations, avoiding sources of time-dependent fluctuations in fluorescence. This assay is made possible by attaching mCer and mCit to the N-termini of PRMT1 and PRMT6. Even though different human PRMT1 splice variants, differing in N-terminal length and sequence have been shown to exhibit differential enzyme activity and substrate specificity,30 we do not observe any differences in kinetic constants (Table I) or substrate specificity (Supporting Information Fig. S4) between fluorescent and nonfluorescent PRMTs. Our study shows that the attachment of additional sequence on the N-termini of PRMT1 and PRMT6 does not affect their enzyme functions, suggesting that dimerization is also not affected.

For the purpose of fitting FRET data, we have made the assumption that the purported PRMT interaction is a 1:1 dimer unaffected by the presence of either N-terminal fluorescent protein mCer or mCit. This necessary assumption implies that during FRET experiments, the pool of monomeric PRMT is the same regardless of the accessory fluorescent protein. Without this assumption it would be necessary to attribute the FRET signal to two separate dissociation constants to determine individual monomer and dimer concentrations. Under the parameters used in this study, the concentration of all three homodimerized species in Figure 1 are the same at the equivalence point for mCer- and mCit-PRMTs.

PRMT oligomerization

The structure of yeast Rmt1p has been shown to form a trimer of dimers (i.e., hexamer) within its crystal lattice, but in solution, it exists mostly as a dimer and its propensity to oligomerize occurs mostly at higher concentrations (0.1–4.0 mg/mL),3 well above concentrations used in this study. Its mammalian homolog PRMT1 exists as a dimer within its crystal structure lattice.4 Dynamic light scattering and size exclusion analyses have estimated the PRMT1 molecular weight to be nearly 6-fold greater than the molecular weight of a dimer and 9-fold greater in the presence of AdoHcy.4 These molecular weights are not consistent with dimeric or hexameric structures, but are more likely caused by high molecular weight aggregates that form as a result of the high concentrations needed for native size determination. In addition, the mobile phase used to perform these experiments contained 5% glycerol, which can reduce PRMT1 activity (Supporting Information Fig. S2). In this study, glycerol concentrations are kept below 1% (final concentration) and [PRMT]total does not exceed 2.1 μM for PRMT1. Aside from PRMT1, no evidence exists currently to suggest that PRMT6 is capable of forming high order oligomers beyond dimers. Efficiency data (Fig. 6) provide evidence that FRET occurs between two PRMT subunits. It is important to note that the relationship derived by Adair and Engelman (1994) applies to relatively small oligomeric complexes and assumes that each subunit can interact with all surrounding subunits.28 We cannot rule out the possibility that FRET between dimers occurs within a higher order oligomer, yet the spectral data from which we derive PRMT dissociation constants is generated from a 1:1 binding interaction between fluorescent PRMTs.

Regulatory implications for PRMT dissociation constants

Our previous kinetic investigation of PRMT6 has demonstrated that it uses a Bi-Bi sequential ordered enzyme mechanism in which AdoMet associates first and AdoHcy dissociates last from the enzyme during a catalytic cycle.26 This mechanism is largely supported by crystal structures of PRMT1, 3, and 4 in complex with AdoHcy that show the cofactor buried underneath N-terminal α-helices (αX and/or αY).2,4–6 Once positioned over the cofactor these α-helices serve as an upper ridge along one side of an acidic groove into which a methyl-accepting polypeptide can dock, and αY also establishes a portion of the contact surface for PRMT dimerization believed to be critical for enzyme activity. We find that PRMT1 and PRMT6 subunits discriminate between AdoMet and AdoHcy in the formation of homodimers consistent with facilitating enzyme turnover. The presence of AdoMet favors PRMT1 dimerization 4-fold and PRMT6 dimerization 6-fold over the presence of AdoHcy [Table II and Fig. 5(B)], suggesting that the PRMT in complex with AdoMet facilitates dimer association in preparation for additional reaction steps to proceed, and the PRMT in complex with AdoHcy triggers dimer dissociation so that the product inhibitor can be released.

The results of this study also point to some differences between PRMT1 and PRMT6 in response to AdoMet or AdoHcy. While the PRMT1 affinities towards AdoMet and AdoHcy are similar (dissociation constants  = 3.5 μM for AdoMet8 and KI = 5.8 ± 0.5 μM for AdoHcy), the PRMT6 affinity towards AdoHcy (KI = 1.4 μM) is ∼10-fold higher than its affinity towards AdoMet (

= 3.5 μM for AdoMet8 and KI = 5.8 ± 0.5 μM for AdoHcy), the PRMT6 affinity towards AdoHcy (KI = 1.4 μM) is ∼10-fold higher than its affinity towards AdoMet ( = 16.5 μM).26 These affinity differences suggest that PRMT6 activity can be more susceptible to the feedback inhibition of AdoHcy than PRMT1 activity. Relative intracellular levels of AdoMet and AdoHcy can also impact enzyme activity. The cellular [AdoMet]/[AdoHcy] ratio, also referred to as methylation potential, has been shown to vary in different human cell lines. For example, this ratio was measured at 53.4 in liver cancer HepG2 cells, 21.1 in liver cancer SK-HEP-1 cells, 14.4 in breast cancer MCF-7 cells, 7.1 in embryonic kidney HEK293 cells, and 6.6 in cervical cancer HeLa cells.31 If we consider the ratio of dissociation equilibrium constants

= 16.5 μM).26 These affinity differences suggest that PRMT6 activity can be more susceptible to the feedback inhibition of AdoHcy than PRMT1 activity. Relative intracellular levels of AdoMet and AdoHcy can also impact enzyme activity. The cellular [AdoMet]/[AdoHcy] ratio, also referred to as methylation potential, has been shown to vary in different human cell lines. For example, this ratio was measured at 53.4 in liver cancer HepG2 cells, 21.1 in liver cancer SK-HEP-1 cells, 14.4 in breast cancer MCF-7 cells, 7.1 in embryonic kidney HEK293 cells, and 6.6 in cervical cancer HeLa cells.31 If we consider the ratio of dissociation equilibrium constants  and KI, then the expression rearranges to yield Eq. (4), where the concentration of PRMT bound to AdoMet is [PRMT • AdoMet], the concentration of PRMT bound to AdoHcy is [PRMT • AdoHcy], and the methylation potential is MP. Using Eq. (4), we calculate that the ratio of PRMT6-bound AdoMet to AdoHcy is 0.56 in HeLa cells (i.e., more PRMT6 is bound to AdoHcy than AdoMet), whereas the same ratio for PRMT1-bound cofactors is 11, thus demonstrating that in cells with lower methylation potential PRMT6 is susceptible to inhibition as a result of its higher affinity for AdoHcy over AdoMet.

and KI, then the expression rearranges to yield Eq. (4), where the concentration of PRMT bound to AdoMet is [PRMT • AdoMet], the concentration of PRMT bound to AdoHcy is [PRMT • AdoHcy], and the methylation potential is MP. Using Eq. (4), we calculate that the ratio of PRMT6-bound AdoMet to AdoHcy is 0.56 in HeLa cells (i.e., more PRMT6 is bound to AdoHcy than AdoMet), whereas the same ratio for PRMT1-bound cofactors is 11, thus demonstrating that in cells with lower methylation potential PRMT6 is susceptible to inhibition as a result of its higher affinity for AdoHcy over AdoMet.

| (4) |

Alterations in the methylation potential can also affect protein–protein interactions as demonstrated by Herrmann et al.,20 who reported recently that GFP fusion proteins of PRMT1 and PRMT6 expressed in HEK293T cells exhibited diffusion characteristics consistent with high molecular weight complexes in fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments. In the presence of adenosine dialdehyde, which is an AdoHcy hydrolase inhibitor that causes intracellular AdoHcy accumulation and subsequent inhibition of AdoMet-dependent methylation, a portion of GFP-PRMT1 became immobilized in the nucleus, whereas diffusion of nuclear GFP-PRMT6 increased.20 The authors propose that PRMTs respond differently to the accumulation of unmethylated substrates, yet our results add another possibility that PRMTs respond differently to increased intracellular AdoHcy. The dimerization KD values for PRMT6 in the presence of either AdoMet or AdoHcy are respectively 6- and 10-fold higher for the corresponding values for PRMT1 (Table II). As the major methyltransferase in cells,32,33 PRMT1 may require a tight subunit interaction as a means to withstand changes in cellular methylation potential, whereas other PRMTs may be more sensitive to different cofactor concentrations for regulatory purposes.

Materials and Methods

Expression plasmids

Plasmids harboring enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (eCFP) were generously donated by Drs. Judy Wong (Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, The University of British Columbia) and Louis Lefebvre (Department of Medical Genetics, The University of British Columbia), respectively. The expression vector for human PRMT6 in pET28a(+) was previously described.12 Rat PRMT1 in pGEX-2T8 was humanized through a H161Y mutation to make PRMT1v1 (isoform 1),30,34 and then sub-cloned into pET28a(+) using BamHI and XhoI restriction sites. PRMT1v1 (isoform 1) is used in all fluorescent constructs with PRMT1. Plasmids pET28a(+)-eGFP-PRMT6 and pET28a(+)-eCFP-PRMT6 were generated by sub-cloning eGFP and eCFP sequences into an NdeI site 5′ to the PRMT6 gene within the pET28a(+) vector using the primers 5′-GGA ATT CCA TAT GGT GAG CAA GGG CGA GGA GC-3′ and 5′-GGA ATT CCA TAT GCT TGT ACA GCT CGT CCA TGC CGA G-3′. Expression plasmids pmCer-PRMT6 and pmCit-PRMT6, which code for mCer- and mCit-PRMT6 fusions, were generated through multiple rounds of site directed mutagenesis on pET28a(+)-eGFP-PRMT6 and pET28a(+)-eCFP-PRMT6 templates using primer sequences (listed in Supporting Information Table SI). To generate pmCer-PRMT1 and pmCit-PRMT1 expression vectors, sequences coding for mCer and mCit were PCR-amplified and sub-cloned into the NdeI site 5′ to PRMT1 within the pET28a(+)-PRMT1 vector using identical primers to those used to amplify eGFP above since the 5′ and 3′ sequences are identical. All of the fluorescent fusions code for the protein sequence AMSTGGQQMGR as a linker between the N-terminal fluorescent protein and the PRMT.

Protein expression and isolation

Expression of both fluorescent (mCer or mCit attached) and nonfluorescent PRMT1 and PRMT6 are induced with 1.0 μM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside at 30°C in BL21(DE3) pLysS gold cells (Stratagene) overnight in LB medium (Fisher Scientific) containing an additional 1.0% glucose, 50-μg/mL kanamycin, and 35-μg/mL chloramphenicol. The cells are harvested via centrifugation in a Beckman model J2-21 centrifuge at 10,000g for 15 min and are immediately frozen at −80°C until purification. After resuspension in lysis buffer (50-mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 1.0-M NH4Cl, 10-mM MgCl2, 0.1% lysozyme, 25-U/mL DNase I, 0.2-μM Triton X-100, 7.0-mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1.0-mM phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride, and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche product code 04693132001) according to volume requirements) at 2 mL per gram wet weight of cells, cells are sonicated using a Branson Sonifier 450 on ice for eight 30-s pulses at 50% duty cycle with 30-s pauses in between. Each protein is first purified via a 1.0-mL HisTrap FF affinity column (GE Healthcare) per 2.0-L bacterial culture using an established method.8 The eluent from the first step is purified using a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 pg column (GE Healthcare). Each sample is collected and exchanged into a storage buffer (100-mM HEPES-KOH, pH 8.0, 200-mM NaCl, 1-mM DTT, 10% glycerol, and 2-mM EDTA) using Amicon Ultra ultracentrifugal filters with a 10-kDa molecular weight cut-off (Millipore), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.8

Protein quantification and spectral characteristics

The concentration of fluorescent fusion proteins is measured using the extinction coefficients for mCit (ɛ516 nm = 77,000 M−1 cm−1) or mCer (ɛ434 nm = 43,000 M−1 cm−1).22,24 The concentrations of unconjugated PRMT1 and PRMT6 are determined by separation of purified proteins on SDS-PAGE and subsequent densitometry of Coomassie blue-stained bands as described previously.8 This method was also used to confirm the concentrations of PRMT fluorescent fusion proteins. A comparison of equal concentrations of fluorescent and nonfluorescent enzymes is shown in Supporting Information Figure S1.

The emission spectra of mCit and mCer fusion proteins, excited at 434 nm, are recorded in methylation buffer consisting of 50-mM HEPES-KOH, pH 8.0, 10-mM NaCl, and 1.0-mM DTT in 3-mL polystyrene cuvettes (Sarstedt) on a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Varian) using medium gain, medium scan speed, a 5-nm excitation slit width, and 10-nm emission slit width.

PRMT activity assays

Nonfluorescent PRMT1, mCer-PRMT1, or mCit-PRMT1 at a concentration of 400 nM are incubated at 37°C for 1 h with increasing histone H4 tail peptide (SGRGKGGKGLGKGGAKRHRKVW)8 and a constant saturating concentration of AdoMet (250 μM) in methylation buffer in a final volume of 80 μL. The H4 tail peptide is used at concentrations of 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10, 20, 40, and 100 mM. Similar reactions are also carried out with 400-nM nonfluorescent PRMT6, mCer-PRMT6, or mCit-PRMT6 using the histone H3 tail peptide (ARTKQTARKSTGGKAPRKQLATKAAW).8 Reactions are stopped by heating at 80°C for 5 min and the reaction samples are dried in a vacuum centrifuge, acid hydrolyzed in the vapor phase with 6.0-M HCl at 110°C in vacuo as described previously.26 Samples are reconstituted in 0.1% aqueous formic acid and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid, and the amount of MMA, aDMA and the total methylation are measured according to a previously described UPLC-MS/MS assay.8 The resulting data is fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation using Sigma Plot 8 (SYSTAT) to generate apparent KM values for the above peptides.

To establish an AdoHcy KI value for PRMT1, methylation assays with 400-nM PRMT1 and the product inhibitor AdoHcy at concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, and 20 μM are performed with constant 80-μM H4 tail peptide and variable concentrations of 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10, and 25-μM AdoMet. The samples are treated as described above, and data are analyzed according to previously described methods.35

FRET measurements

All steady-state FRET measurements are performed in a microplate format on a Synergy Mx Monochromator-based Multi-mode Microplate Reader (Biotek). Measurements are taken using excitation and emission slit widths of 9 nm. Sample wells are filled to an 80-μL final volume in a 384-well black polystyrene non-binding surface microplate (Corning #3575). The mCer donor is excited at 434 nm and fluorescence emitted from the mCit acceptor is measured at 529 nm in absolute fluorescence. Sensitivity is adjusted with an 8-mm height correction from the upper plane of the sample wells.

For KD measurements each plate contain five rows comprised of sixteen different fluorescent protein concentrations (four rows are used for samples with fluorescent PRMT6 and AdoMet), and two additional rows for mCit and mCer background signal. Sample wells are prepared in quintuplicate and contain a 0.5-μM mCer-PRMT1 or 0.5-μM mCer-PRMT6 solution to which varying concentrations of mCit-PRMT1 or mCit-PRMT6 are added to saturate FRET signal. Plate readings are acquired after 60 min incubation at 37°C. Background signals are determined by measuring fluorescence of individual fluorescent proteins at concentrations corresponding to experimental samples, and these background signals are subtracted from the experimental FRET signals to generate background-corrected data, which is fit using Caligator set to a 1:1 ratio for protein binding to calculate KD values.25

For efficiency measurements used to assess subunit contributions to FRET, 11 solutions are premixed containing either 1.0-μM mCer-PRMT1 or 1.0-μM mCer-PRMT6, as well as varying concentrations up to 1.0-μM mCit-PRMT1 or 1.0-μM mCit-PRMT6, respectively. These solutions are then preincubated at 37°C for 1 h and transferred in 80-μL aliquots into 384-well plates in triplicate. Efficiency measurements are performed with 434-nm excitation and 475-nm emission wavelengths.

PRMT1 and PRMT6 FRET specificity assays are performed by premixing mCer-PRMT1 with mCit-PRMT1 or mCer-PRMT6 with mCit-PRMT6 at 1.0-μM each fluorescent protein along with varying concentrations up to 5.0 μM of nonfluorescent PRMT1, PRMT6, or methylation buffer as a control. The solutions are incubated for 60 min at 37°C prior to exciting samples at 434 nm and measuring fluorescence at both 475 nm and 529 nm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Judy Wong and Louis Lefebvre from The University of British Columbia for their generous donations of eGFP- and eCFP-containing vectors. D.T. is a recipient of the University Graduate Fellowship Award from The University of British Columbia.

References

- 1.Bedford MT, Clarke SG. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: who, what, and why. Mol Cell. 2009;33:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Zhou L, Cheng X. Crystal structure of the conserved core of protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT3. EMBO J. 2000;19:3509–3519. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss VH, McBride AE, Soriano MA, Filman DJ, Silver PA, Hogle JM. The structure and oligomerization of the yeast arginine methyltransferase, Hmt1. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1165–1171. doi: 10.1038/82028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Cheng X. Structure of the predominant protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 and analysis of its binding to substrate peptides. Structure. 2003;11:509–520. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00071-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue WW, Hassler M, Roe SM, Thompson-Vale V, Pearl LH. Insights into histone code syntax from structural and biochemical studies of CARM1 methyltransferase. EMBO J. 2007;26:4402–4412. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troffer-Charlier N, Cura V, Hassenboehler P, Moras D, Cavarelli J. Functional insights from structures of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 domains. EMBO J. 2007;26:4391–4401. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin WJ, Gary JD, Yang MC, Clarke S, Herschman HR. The mammalian immediate-early TIS21 protein and the leukemia-associated BTG1 protein interact with a protein-arginine N-methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15034–15044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakowski TM, Frankel A. Kinetic analysis of human protein arginine N-methyltransferase 2: Formation of monomethyl- and asymmetric dimethylarginine residues on histone H4. Biochem J. 2009;421:253–261. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang J, Gary JD, Clarke S, Herschman HR. PRMT 3, a type I protein arginine N-methyltransferase that differs from PRMT1 in its oligomerization, subcellular localization, substrate specificity, and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16935–16945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen D, Ma H, Hong H, Koh SS, Huang SM, Schurter BT, Aswad DW, Stallcup MR. Regulation of transcription by a protein methyltransferase. Science. 1999;284:2174–2177. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schurter BT, Koh SS, Chen D, Bunick GJ, Harp JM, Hanson BL, Henschen-Edman A, Mackay DR, Stallcup MR, Aswad DW. Methylation of histone H3 by coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5747–5756. doi: 10.1021/bi002631b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frankel A, Yadav N, Lee J, Branscombe TL, Clarke S, Bedford MT. The novel human protein arginine N-methyltransferase PRMT6 is a nuclear enzyme displaying unique substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3537–3543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108786200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee YH, Stallcup MR. Minireview: protein arginine methylation of nonhistone proteins in transcriptional regulation. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:425–433. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branscombe TL, Frankel A, Lee JH, Cook JR, Yang Z, Pestka S, Clarke S. PRMT5 (Janus kinase-binding protein 1) catalyzes the formation of symmetric dimethylarginine residues in proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32971–32976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105412200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollack BP, Kotenko SV, He W, Izotova LS, Barnoski BL, Pestka S. The human homologue of the yeast proteins Skb1 and Hsl7p interacts with Jak kinases and contains protein methyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31531–31542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miranda TB, Miranda M, Frankel A, Clarke S. PRMT7 is a member of the protein arginine methyltransferase family with a distinct substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22902–22907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JH, Cook JR, Yang ZH, Mirochnitchenko O, Gunderson SI, Felix AM, Herth N, Hoffmann R, Pestka S. PRMT7, a new protein arginine methyltransferase that synthesizes symmetric dimethylarginine. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3656–3664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Straubinger RM, Aletta JM, Cao J, Duan X, Yu H, Qu J. Accurate localization and relative quantification of arginine methylation using nanoflow liquid chromatography coupled to electron transfer dissociation and orbitrap mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;20:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higashimoto K, Kuhn P, Desai D, Cheng X, Xu W. Phosphorylation-mediated inactivation of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12318–12323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610792104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrmann F, Pably P, Eckerich C, Bedford MT, Fackelmayer FO. Human protein arginine methyltransferases in vivo—distinct properties of eight canonical members of the PRMT family. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:667–677. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsien RY. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaner NC, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2005;2:905–909. doi: 10.1038/nmeth819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heikal AA, Hess ST, Baird GS, Tsien RY, Webb WW. Molecular spectroscopy and dynamics of intrinsically fluorescent proteins: coral red (dsRed) and yellow (Citrine) Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11996–12001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizzo MA, Springer GH, Granada B, Piston DW. An improved cyan fluorescent protein variant useful for FRET. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:445–449. doi: 10.1038/nbt945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andre I, Linse S. Measurement of Ca2+-binding constants of proteins and presentation of the CaLigator software. Anal Biochem. 2002;305:195–205. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakowski TM, Frankel A. A kinetic study of human protein arginine N-methyltransferase 6 reveals a distributive mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10015–10025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews DL, Demidov AA. Resonance energy transfer. New York: Wiley; 1999. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adair BD, Engelman DM. Glycophorin A helical transmembrane domains dimerize in phospholipid bilayers: a resonance energy transfer study. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5539–5544. doi: 10.1021/bi00184a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li M, Reddy LG, Bennett R, Silva ND, Jr, Jones LR, Thomas DD. A fluorescence energy transfer method for analyzing protein oligomeric structure: application to phospholamban. Biophys J. 1999;76:2587–2599. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goulet I, Gauvin G, Boisvenue S, Cote J. Alternative splicing yields protein arginine methyltransferase 1 isoforms with distinct activity, substrate specificity, and subcellular localization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33009–33021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermes M, Osswald H, Mattar J, Kloor D. Influence of an altered methylation potential on mRNA methylation and gene expression in HepG2 cells. Exp Cell Res. 2004;294:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang J, Frankel A, Cook RJ, Kim S, Paik WK, Williams KR, Clarke S, Herschman HR. PRMT1 is the predominant type I protein arginine methyltransferase in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7723–7730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pawlak MR, Scherer CA, Chen J, Roshon MJ, Ruley HE. Arginine N-methyltransferase 1 is required for early postimplantation mouse development, but cells deficient in the enzyme are viable. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4859–4869. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4859-4869.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osborne TC, Obianyo O, Zhang X, Cheng X, Thompson PR. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1: positively charged residues in substrate peptides distal to the site of methylation are important for substrate binding and catalysis. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13370–13381. doi: 10.1021/bi701558t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segel IH. Enzyme kinetics: behavior and analysis of rapid equilibrium and steady-state enzyme systems. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1975. pp. 506–841. [Google Scholar]