Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to quantify changes in refractive status over time in children with infantile esotropia and to analyse a number of clinical factors associated with infantile esotropia to determine how they may affect emmetropisation.

Methods

Longitudinal cycloplegic refraction data were collected for 5-12 years from 143 consecutive children enrolled in a prospective study of infantile esotropia by 6 months of age. Changes in refractive error with age were summarized with descriptive statistics and the influence of amblyopia, undercorrection of hypermetropia, accommodation, and binocular factors on emmetropisation were evaluated by ANOVA and t-tests.

Results

Most had low to moderate hypermetropia on the initial visit (55% had <+3.00 D). While the initial refractive error is similar to normative data, the rapid decrease in hypermetropia that characterizes normal development during the first 9 months of life is absent in children with infantile esotropia. After 9 months of age, children with infantile esotropia follow a developmental course that is similar to the normative course; there is little change in hypermetropia during years 1-7, followed by a decline of approximately -0.5 D/yr beginning at age 8 years. None of the clinical factors examined had a statistically significant effect on the course of refractive changes with age.

Conclusions

Children with infantile esotropia exhibit a different pattern of refractive development than that seen in normative cohorts. The long term changes in refraction observed in children with infantile esotropia suggest that there is a need for long-term clinical follow-up of these children.

Keywords: infantile esotropia, refractive error, emmetropisation, hypermetropia, accommodative esotropia, amblyopia

Introduction

Defective emmetropisation has been reported in children with strabismus1 and it has been hypothesized that the onset of strabismus results from persistent hypermetropia.2 Ingram reported that emmetropisation was defective in both eyes of more than 80% of children with either a microtropia or heterotropia, regardless of their early refractive status.1 However, because the follow up period was limited to the first 3.5 years of life, it is not known whether the strabismus was associated with slower/delayed eye growth or whether the effect on eye growth persisted in the long term.

Prescribing glasses for hypermetropia in early childhood may impede emmetropisation1 but, in children with strabismus, emmetropisation may fail irrespective of refractive correction.3 This finding is somewhat difficult to interpret, though, because all cases of microtropia and heterotropia were considered together and this prevents understanding of the impact of type of strabismus, visual acuity, and the level of binocular vision on emmetropisation. One study that did analyse esotropia (ET) and exotropia (XT) separately found an increase in the refractive error before the onset of ET, but no consistent relationship between refractive error and the onset of XT.2 However, the considerable variability in concomitance, constancy of the heterotropia, age of onset, and fusion/stereoacuity among children with ET makes it difficult to apply findings from this study to clinical care.

Concomitant ET has a bimodal age-of-onset distribution, with onset < 6 months of age in about 40% and 18-48 months in 60%.4 One of the most common types of concomitant ET is infantile ET, with an incidence of 0.2-0.6% in the U.K.5-7 and U.S.8-11 Nearly all children with infantile ET have surgery to align their eyes and over 80% require occlusion therapy and/or spectacle correction to treat amblyopia.12 Many require repeated interventions. In addition, sequelae of infantile ET include recurrent ET, consecutive XT, dissociated vertical deviation, and latent nystagmus.12-15 Recurrent ET is found in 60% of children who had surgery for infantile ET during the first 2 years of life even though >80% have refractive error <+3.00 dioptre sphere (DS). It typically occurs after a 12-24 month period of post-surgical orthotropia and usually is accommodative or partially accommodative.16-20 It has been hypothesized that the poor binocular sensory outcome associated with infantile ET allows accommodative ET to develop at low to moderate levels of hypermetropia.17 While the distribution of refractive errors in children with infantile ET has been described, with the most common refractive error in the range 0.00 to +2.00 DS (46.4% to 61%),14, 20-22 little is known about longitudinal changes in refractive status.

In children with low to moderate hypermetropia without strabismus, the bulk of emmetropisation occurs between 3 and 9 months of age.23-25 Predetermined genetic factors clearly playa role in this early period of eye growth.26 However, there is also evidence for active coordination between the optical and structural development of the growing eye that depends on the ability of the eye to detect hypermetropic defocus and respond to its refractive error; namely, the amount of refractive change and axial growth during this early period is proportional to the initial amount of hypermetropia.24, 27 The information provided to the developing eye by hypermetropic defocus will depend on both the underlying refractive error and on accommodation.

The aim of this study was to quantify changes in refractive status over time in children with infantile ET and to analyse a number of factors associated with infantile ET to determine how they may affect emmetropisation.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 143 consecutive patients enrolled in a prospective study of infantile ET at the time of diagnosis, by 6 months of age. They were referred to the study by 16 Dallas-Fort Worth paediatric ophthalmologists. All were followed up for a minimum of 5 years. None of the patients had known developmental delay, concurrent ophthalmic or systemic diseases. None of the children were born preterm (≤36 weeks).

Statement of Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from a parent prior to the infant's enrolment. This research protocol observed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Patient Care

Patient care was at the discretion of the referring ophthalmologists, within the guidelines of the American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern: Esotropia and Exotropia.28 Briefly, initial management included spectacle correction of hypermetropia ≥+3.00 DS, prescribing the full cycloplegic retinoscopy findings (lesser amounts of hypermetropia were corrected at the ophthalmologist's discretion) and amblyopia treatment. Only after refractive and amblyopia treatment commenced, if needed, was surgery undertaken to correct ocular alignment. Post-operatively, glasses were prescribed whenever residual or recurrent ET was present and the hypermetropia was ≥+3.00 DS prior to 12 months, ≥+2.00 DS at 1-2 years, and ≥+ 1.5 DS at ≥2 years; glasses were prescribed for lesser amounts of hypermetropia at the ophthalmologist's discretion. Some of the referring ophthalmologists attempted to wean patients from spectacle wear gradually by initiating undercorrection by 0.50 to 1.00 DS at 5-7 years of age and progressively decreasing the hypermetropic correction in 0.50 or 1.00 DS increments at 6-month intervals. Hypermetropic correction was reduced only if the child maintained adequate alignment at distance and near with the current spectacle correction and remained aligned with the reduced correction when tested in the office with trial lenses. Compliance with glasses and amblyopia therapy was monitored by parent interview at the research laboratory visits. Perhaps because parents had voluntarily enrolled their children as research participants in the study (located at a site separate from where the child received medical care), they were highly motivated to comply with treatment and generally reported excellent (>75%) compliance.

Onset and Duration of Esotropia

The age at onset of ET was calculated based on information in medical records and a standardised parent questionnaire as described previously.13 Age at alignment was defined as the age in months at which alignment within the 0 to 8Δ range was first achieved and maintained for at least 12 months (stable alignment). The duration of misalignment was calculated as the difference in months between the age at onset and the age at alignment.

Refractive error

Cycloplegic retinoscopy (1% cyclopentolate) was performed by the referring paediatric ophthalmologists as part of routine medical care. Data were recorded in the traditional format of sphere (S), plus cylinder (C), and axis (α). These raw data were converted into power vector components:29 M (spherical equivalent), J0 (positive J0 indicates with-the-rule astigmatism; negative J0 indicates against-the-rule astigmatism) and J45 (oblique astigmatism):

While standard notation is limited to reports of spherical equivalent and cylinder power without regard to precise axis, power vector notation can be used to track changes in refractive error with age as simple, linear differences between independent vector components.

Statistical Methods

With the exception of anisometropia, all refractive error data are reported for right eyes only. Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation, except for angle of deviation which is reported as the median ± interquartile interval because prism measurement is on a non-interval scale. Change in refraction over time was calculated as the difference in refraction at the last visit in the 5-7-year-age interval and the last visit in the 8-12-year-age interval divided by the number of years between the two visits (DS/yr). T-tests were used for two-group comparisons and one-way ANOVAs for comparisons among multiple groups. Two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the interaction between change in refractive error by year and age at which amblyopia was present (never, infantile, age 2-5 years, persistent long-term). Linear regression was used to define the relationship between initial refractive error and refractive error at 5-7, 8-10, and 11-12 years.

Results

Clinical Factors

The mean age (±SD) at onset of the ET was 2.8±1.3 months. Eighty-six (60%) of the participants had onset at age 2 months, 29 (20%) at age 3 monts, 12 (8%) at age 4 months, 9(6%) at age 5 months, and 7 (5%) at age 6 months. The mean age at initial visit was 4.5±1.7 months. The median angle of ET at the initial visit, measured to the nearest 5Δ, was 45Δ(IQR±10Δ).

Thirteen (9%) of the participants had resolution of their ET before 12 months of age with (n=9, ET only present without glasses) or without (n=4, no ET; excluded from the analysis) spectacle correction. The remaining 130 (91%) participants had surgery at a mean age of 9.9±5.6 months. The age at initial surgery was ≤12 months for 114 (80%) participants, 12-24 months for 9 (6%) participants, and >24 months for 7 (5%) participants. Among the 114 participants who had surgery prior to age 12 months, 97 were aligned within 8Δ post-operatively, 3 improved to ≤8Δwith spectacle correction, and 14 had residual ET ≥ 10Δ post-operatively (11 of these 14 had a second surgery at age 10.4±1.9 months). Among the 16 participants who had surgery after 12 months of age, 15 were aligned within 8Δ post-operatively and 1 improved to ≤8Δ with spectacle correction. During the follow up period of 5-12 years, 57% (n=82) required additional surgery for recurrent esotropia (n=17; age at surgery =43.5±35.9 months), for consecutive exotropia (n=29; age at surgery =57.7±36.2 months), or for dissociated vertical deviation, hypertropia, or oblique muscle overaction (n=53; age at surgery =40.5±21.6 months); note that some children had more than one type of surgery.

The mean duration of ET prior to attaining stable alignment (≤8Δ for a minimum of 12 months) was 5.4±8.3 months. Seventy-two (50%) of the participants had duration of ≤3 months and 71 (50%) had duration of 4 months or more. Mean age at follow up was 8.7±3.2 years (range 5 to 12 years).

Eighty-two (57%) participants were classified as amblyopic by fixation preference testing at the initial visit, either by absence of steady, central fixation by one eye (n=12; 8%) or failure to maintain fixation through a blink with one eye (n=70; 49%). These participants were treated for amblyopia with occlusion therapy of 0.5-4 hours/day for 1-3 months prior to surgery. Overall, 55 (38%) participants were never found to be amblyopic during the 5-12 year follow-up period, 54 (38%) participants had only one episode of amblyopia treatment (30 prior to 12 months of age, 12 at 2-5 years of age, 12 at >5 years of age), and 18 (13%) had longterm amblyopia that persisted beyond 7 years of age despite treatment with occlusion therapy and/or atropine.

Refractive Error on the Initial Visit

On the initial visit, most infants with infantile ET had low to moderate hypermetropic refractive errors; 55% had a spherical equivalent <+3.00 DS, 27% had a spherical equivalent of +3.00 to +4.99 DS, and only 19 (13%) had a spherical equivalent ≥+5 .00 DS. Eight (6%) had a myopic spherical equivalent. Anisometropia ≥1.00 DS was rare (n=13; 9%) but astigmatism ≥1.00 DC was common (n=52; 36%, including 15% WTR, 10% ATR, and 10% oblique astigmatism). On the initial visit, 57 (40%) children had refractive error sufficient to require spectacle correction according to the AAO guidelines described previously.28

Forty of the 57 were prescribed glasses on the initial visit. Seven infants who were≤3 months of age at the time of the initial visit and/or presented with a variable angle of deviation were prescribed glasses at the second visit, 2-8 weeks later. The remaining 10 infants either were not prescribed glasses (ET ≥50Δ with ≤+3.50 DS and anisometropia <1.00 DS; n=8) or the parents refused treatment with glasses (n=2).

Based on power vector analyses of the raw cycloplegic refraction data, mean spherical error (M) at the initial visit was +2.54±1.83 DS for right eyes and +2.55±1.82 DS for left eyes. Mean astigmatic error was negligible (J0= 0.05±0.37 DC; J45 = -0.12±0.26 DC). Mean anisometropia (|Mright-Mleft|) was 0.28±0.60DS.

Longitudinal Changes in Refractive Error

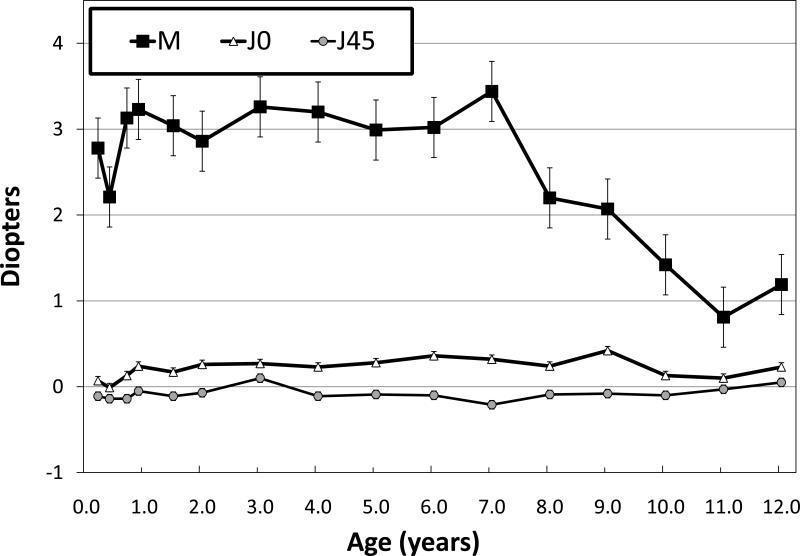

Children with infantile ET remained moderately hypermetropic through age 7 years (at 7 years, M = +3.18 ±1.78 DS; Figure 1). Most children had either no change or an increase in the amount of hypermetropia at 5 to 7 years compared to their initial visit; only 28% had a decrease of ≤0.5 DS over this age range. After age 7 years, refractive error decreased by approximately -0.50 DS/year so that, at age 11-12 years, M = +1.00 D±2.22 DS.

Figure 1.

Mean ± standard error right eye refractive error as a function of age expressed in power vector notation (see text for details).

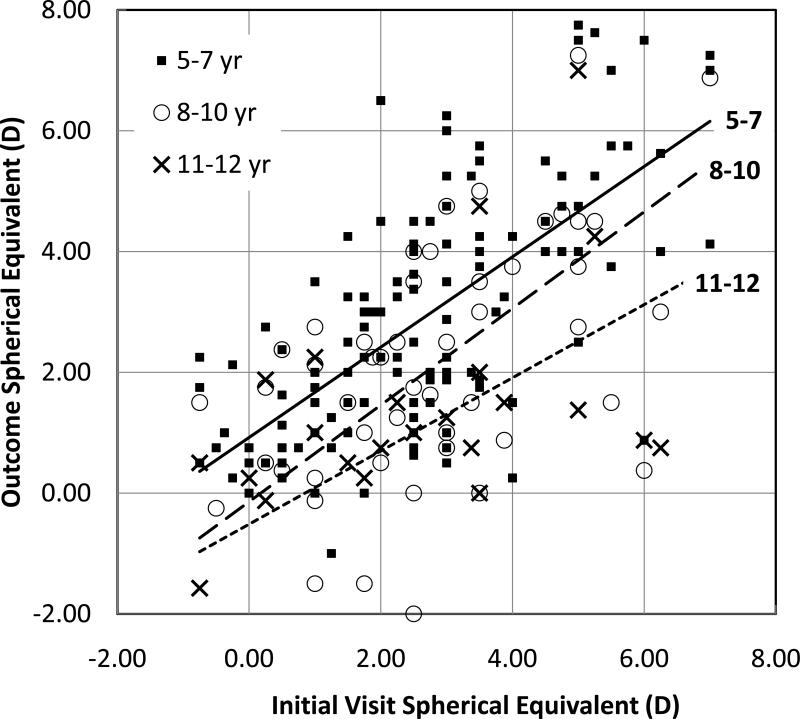

Half (50%) of the children had a decrease in the amount of hypermetropia at 8 to 10 years compared to their initial visit and 71% had a decrease in the amount of hypermetropia at 11 to 12 years compared to their initial visit. Children with more hypermetropia on the initial visit showed larger decreases in hypermetropia during follow-up (Figure 2). Nonetheless, children who had ≤+5.00 on their initial visit (n=19) had a mean decrease in of only 1.1±2.4 DS by 8-10 years (approximately 0.5DS/yr) and all 19 remained hypermetropic at the final visit.

Figure 2.

Spherical equivalent of the right eye at the 5-7, 8-10, and 11–12 year outcome visits related to spherical equivalent at the initial visit. Lines show the best fit linear regression for each outcome visit on initial visit refraction. The best fit lines for regression of outcome refractive error on initial refractive error was y=0.75×+0.92 (r=0.67) for outcome at 5-7 years, y=0.80×-0.14 (r=0.61) for outcome at 8-10 years, and y=0.61×-0.52 (r=0.56) for outcome at 11-12 years.

Mean astigmatic error remained negligible throughout age 7 years (J0 = 0.27±0.47 DC; J45 = -0.07±0.26 DC; Figure 1). The prevalence of anisometropia remained approximately constant throughout follow-up (7-11%). Most anisometropia that was present during infancy (9 of 13 cases; 69%; range of anisometropia on initial visit: 1.00 to 3.75 DS) resolved during follow-up but new cases developed, including 10 new cases of anisometropia with onset ≥5 years of age (range of anisometropia on most recent visit: 1.00 to 2.25 DS).

Comparison to Normal Growth of the Eye

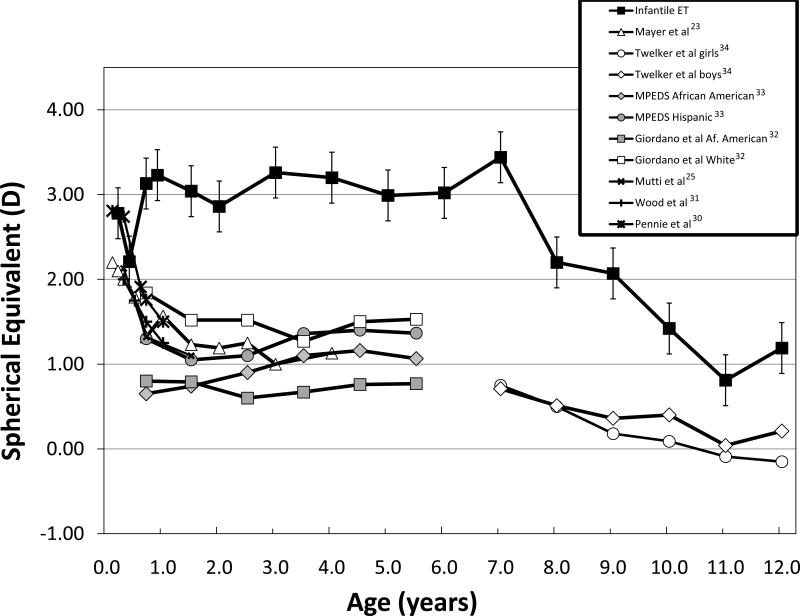

Compared to the normal rapid decline in hypermetropia during the first 9-12 months of life reported in the literature,23, 25, 30, 31 children with infantile ET showed little change in hypermetropia during infancy (Figure 3). On the other hand, the 0.50 DS/year myopic trend that was present in children with infantile ET between 7 and 12 years of age is similar to normative data.32-34

Figure 3.

Mean ± standard error spherical error (M) of right eyes of children with infantile ET (current study) and in previously published normative data.23, 25, 30-34

Amblyopia

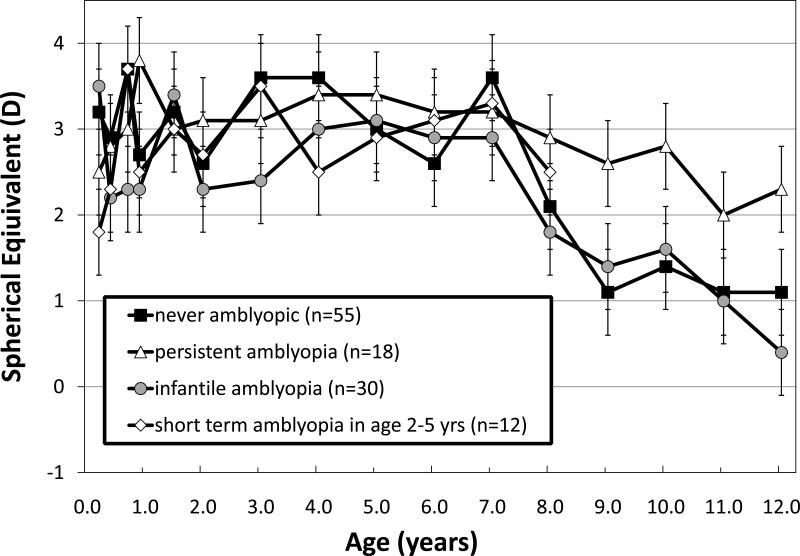

Similar changes in refractive error with age were found for subgroups of patients with infantile ET who were never amblyopic, were diagnosed with amblyopia only during infancy (by fixation preference), or had short-term amblyopia at age 2-5 years (Figure 4). All subgroups remained moderately hypermetropic through age 7 years and, after age 7 years, refractive error decreased by approximately -0.50 DS/year. For the subgroup of children who had persistent amblyopia that was present from age 5 years until the final visit, there was a suggestion of a smaller total change or slower rate of change with age after 7 years of age, averaging about -0.25 DS/year but this was not statistically significant (Subgroup × Age interaction for ages 5-12 years: F6,117=0.38; p=0.68).

Figure 4.

Mean ± standard error spherical error (M) for right eyes of children with infantile ET who were never amblyopic, were diagnosed with amblyopia only during infancy (by fixation preference), had short-term amblyopia at age 2-5 years, or who had amblyopia that persisted beyond 5 years of age despite longterm and/or multiple attempts to treat.

Weaning from Spectacles

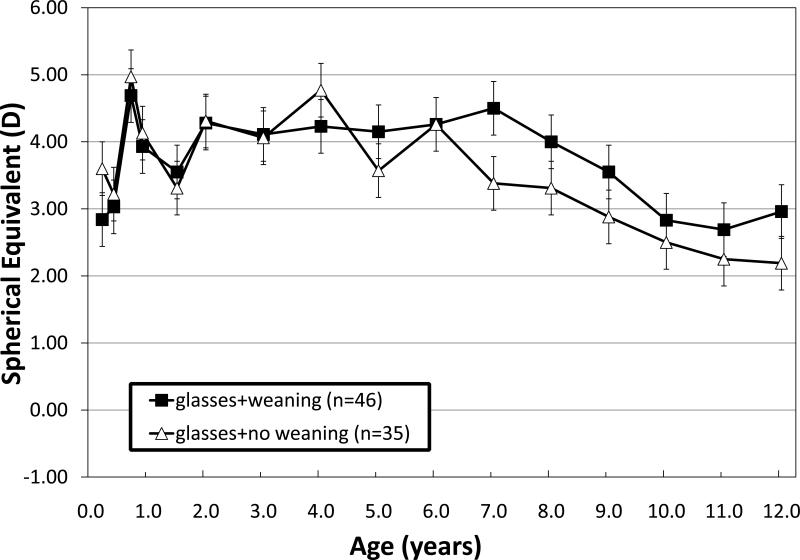

In addition to the 47 children who received spectacle correction for hypermetropia at the first or second visit, an additional 35 began spectacle wear postoperatively (beginning at 1.5-4 years of age) for a total of 82 children with longterm spectacle wear. Of these 82 children, 46 had an attempt to wean from spectacle wear gradually by initiating undercorrection by 0.50 to 1.00 DS at 5-7 years of age and progressively decreasing the hypermetropic correction in 0.50 DS or 1.00 DS increments at every 6-month intervals as long as the child was able to maintain adequate alignment at distance and near with the reduced power. Figure 5 shows the course of refractive changes in the group that had weaning attempted and in the group that did not. The refractive changes as a function of age were similar in both groups. In the weaning group, 32% of the children with an initial refractive error >+3.00 DS had a final refractive error of 0.00 to +1.00 OS, which was not statistically significantly different from the prevalence of 25% in the no weaning group.

Figure 5.

Mean ± standard error spherical error (M) for right eyes of children with infantile ET who wore hypermetropic spectacle correction with an attempt to wean with progressive undercorrection beginning at 5-7 years of age or without an attempt to wean.

Accommodation

Children with nonaccommodative infantile ET, with initial visit refractive error ranging from -0.75 to +3.00DS, had a slight increase in hypermetropia during the first 5 years of life (+0.5±0.3DS) followed by a progressive decrease in hypermetropia (0.50±0.41 DS/yr) during years 8-12. Children with infantile accommodative ET had higher refractive errors on their initial visit (range +3.00 to +7.00DS) and showed little change during the first 5 years, but experienced similar decreases in hypermetropia (0.61±0.32 DS/yr) during years 8-12. Children with partially accommodative ET experienced a mean decrease of 0.38±0.66 DS/yr. There were no statistically significant differences among nonaccommodative, accommodative, and partially accommodative groups in the rate of change in refractive error during years 8-12 (F2,142 = 0.92, p=0.40).

Binocular Factors

Children with anisometropia on the initial visit had statistically significantly more hypermetropia than children without anisometropia in the more hypermetropic eye (+3.52±1.81 vs +2.52±1.83 DS; t141=2.07; p=0.04) and trended toward statistically significantly less hypermetropia than children without anisometropia in the less hypermetropic eye (+1.69±1.81 vs +2.52±1.83 DS t141=1.80; p=0.07). Anisometropic children showed statistically significant decreases in hypermetropia during follow-up and, in 9 of 13 (69%), loss of anisometropia.

Children with normal stereoacuity at≥5 yr of age (≤60 arc sec on the Preschool Randot Stereoacuity test) had statistically significantly more hypermetropia at their initial visit than those with reduced (3.95±1.99 vs 2.25±1.78 DS, t60=3.13, p=0.003) or nil stereoacuity (3.95±1.99 vs 2.43±1.84 DS, t74=2.78, p=0.007, respectively) and at their 5-7 year visit (3.97±1.47 vs 2.67±1.88 DS, t60=2.13, p=0.04 and 3.97±1.99 vs 2.69±1.93 DS, t74=2.15, p=0.04, respectively). Beyond 7 years of age, there were no statistically significant differences.

Regardless of motor outcome following the initial surgery or duration of ET prior to stable alignment, a similar trend in refractive development was found, with stable or slightly increasing hypermetropia through age 7 years followed by progressive decreases in hypermetropia through age 12 years.

Discussion

Most children with infantile ET had low to moderate hypermetropia on the initial visit prior to 6 months of age, and the hypermetropia either remained stable or increased through at least age 5 years. Beginning at age 8 years and continuing through age 12 years, hypermetropia decreased by 0.5 DS/yr on average. The pattern of refractive development in children with infantile ET was distinctly different from that previously reported for normative cohorts of children.23-25, 30-35 In normative cohorts, children typically undergo a rapid decrease in hypermetropic refractive error between 3 and 9 months, followed by long period of near-emmetropia from 1 to 5 years of age. On the other hand, after age 5 years, the children with infantile ET are similar to the reported normative cohorts in that both show myopic shifts of -0.5DS/yr after 7 years of age and those with the highest initial amounts of hypermetropia show greater myopic shift.

Children with an accommodative ET show a similar trend of little change or slight increase in hypermetropia prior to 7 years, then decreasing hypermetropia after age 7 years;36-39 however, they show slower rate of change (0.11-0.18DS/yr) in hypermetropia than our infantile ET cohort.36-39 This is surprising because, at least in infancy, the rate of change is correlated with degree of refractive error25, 27 and the accommodative ET cohorts have higher initial hypermetropia than our infantile ET cohort.36-39 Within our cohort of infantile ET, even those with high hypermetropia on the initial visit (≥+5.00 DS) had approximately the same 0.5DS/yr rate of decrease in hypermetropia after age 7 years.

There is some evidence that amblyopia may affect emmetropisation in strabismic amblyopia and moderate to high hypermetropia.40 However, in agreement with Rutstein and Corliss,41 we found that amblyopia had no statistically significant impact on the change in hypermetropia over time in children with strabismic amblyopia. Our data were presented for right eyes, regardless of which eye was amblyopic, but re-analysis of amblyopic and fellow eye separately yielded similar results. Taken together, these two studies suggest that amblyopia is not a major factor in refractive change over the first 12 years of life in strabismic amblyopia with low to moderate hypermetropia; whether this finding can be generalized to other forms of strabismic amblyopia is unknown.

Based on evidence that infant rhesus monkeys who wear plus lenses become more hypermetropic,42, 43 it has been suggested that providing the full hypermetropic spectacle correction may interfere with emmetropisation.39 Our weaning data (Figure 5) do not support this hypothesis. There were no statistically significant differences among patients with nonaccommodative ET, accommodative ET, and partially accommodative ET groups in the lack of change in hypermetropia during the first 5-7 years of life or in the rate of change in refractive error during years 8-12. In addition, although the success of undercorrection of hypermetropia in children with acquired accommodative ET in reducing hypermetropia has been reported to be 60% in a small series of 10 patients,37 we found that undercorrection of hypermetropia did not affect the rate of decrease in hypermetropia that began after 7 years of age nor did weaning affect the proportion of children with initial refraction >+3.00DS who achieved a final refraction of 0.00 to +1.00DS. This result is similar to a recent study of 285 children with accommodative ET, in which weaning had no effect on rate of decrease of hypermetropia after age 7 years.36 None of the factors associated with binocular function (anisometropia, stereoacuity, duration of misalignment prior to achievement of stable alignment) affected the developmental changes in refractive error in children with infantile ET.

In summary, children with infantile ET exhibit a different pattern of refractive development in comparison with normative cohorts. During the first 9 months, the axial growth of the eye normally reduces hypermetropia because its dioptric effects exceed the effects of losses in corneal and lens power.24, 44 Whether the different pattern of refractive development observed in children with infantile ET is due to differences in maturation of axial length, cornea, and/or lens is unknown. The decline of hypermetropia at a rate of approximately -0.5 DS/yr beginning at age 8 years, whether or not the child wore full spectacle correction of hypermetropia, suggests that spectacle wear does not disadvantage the growing eye of children with infantile ET. Due to changes in refraction after age 7 years, there is a need for long-term follow-up of these children.

Acknowledgements

Christina Cheng assisted with database design and data entry. This study was supported by a grant from the National Eye Institute (EY05236).

Supported by a grant from the National Eye Institute (EY05236)

Footnotes

The study was conducted at: Retina Foundation of the Southwest

None of the authors has a commercial interest in any of the tests or procedures described herein.

Presented as a poster at the 2008 ARVO meeting in Ft. Lauderdale, FL

References

- 1.Ingram RM, Gill LE, Lambert TW. Emmetropisation in normal and strabismic children and the associated changes of anisometropia. Strabismus. 2003;11:71–84. doi: 10.1076/stra.11.2.71.15104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrahamsson M, Fabian G, Sjostrand J. Refraction changes in children developing convergent or divergent strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:723–727. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.12.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingram RM, Gill LE, Lambert TW. Effect of spectacles on changes of spherical hypermetropia in infants who did, and did not, have strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:324–326. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.3.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tychsen L. Visual cortex mechanisms of strabismus: Development and maldevelopment. In: Lorenz B, Brodsky M, editors. Pediatric Ophthalmology, Neuro-Ophthalmology, Genetics. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg: 2010. pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anker S, Atkinson J, Braddick O, Ehrlich D, Hartley T, Nardini M, et al. Identification of infants with significant refractive error and strabismus in a population screening program using noncycloplegic videorefraction and orthoptic examination. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:497–504. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams C, Northstone K, Harrad RA, Sparrow JM, Harvey I. Amblyopia treatment outcomes after screening before or at age 3 years: follow up from randomised trial. Br Med J. 2002;324:1549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7353.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams C, Northstone K, Howard M, Harvey I, Harrad RA, Sparrow JM. Prevalence and risk factors for common vision problems in children: data from the ALSPAC study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:959–964. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.134700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, Giordano L, Ibironke J, Hawse P, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in white and African American children aged 6 through 71 months the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2128–2134. e2121–2122. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg AE, Mohney BG, Diehl NN, Burke JP. Incidence and types of childhood esotropia: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louwagie CR, Diehl NN, Greenberg AE, Mohney BG. Is the incidence of infantile esotropia declining?: a population-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1965 to 1994. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:200–203. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Multi-ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in African American and Hispanic children ages 6 to 72 months the multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1229–1236. e1221. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birch EE, Stager DR, Sr., Berry P, Leffler J. Stereopsis and long-term stability of alignment in esotropia. J AAPOS. 2004;8:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birch EE, Fawcett S, Stager DR. Why does early surgical alignment improve stereoacuity outcomes in infantile esotropia. J AAPOS. 2000;4:10–14. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(00)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birch EE, Felius J, Stager DR, Sr., Weakley DR, Jr., Bosworth RG. Preoperative stability of infantile esotropia and post-operative outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birch EE, Stager DR., Sr. Long-term motor and sensory outcomes after early surgery for infantile esotropia. J AAPOS. 2006;10:409–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker JD, DeYoung-Smith M. Accommodative esotropia following surgical correction of congenital esotropia, frequency and characteristics. Graefes Archives of Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 1988;226:175–177. doi: 10.1007/BF02173312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birch EE, Fawcett SL, Stager DR., Sr. Risk factors for the development of accommodative esotropia following treatment for infantile esotropia. J AAPOS. 2002;6:174–181. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2002.122962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiles DA, Watson BA, Biglan AW. Characteristics of infantile esotropia following early bimedial rectus recession. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:697–703. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020030691008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raab EL. Etiologic factors in accommodative esodeviation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1982;80:657–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robb RM, Rodier DW. The broad clinical spectrum of early infantile esotropia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1986;84:103–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birch EE, Stager DR, Wright K, Beck R. The natural history of infantile esotropia during the first six months of life. J AAPOS. 1998;2:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(98)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costenbader FD. Essential infantile esotropia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1961;59:397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer DL, Hansen RM, Moore BD, Kim S, Fulton AB. Cycloplegic refractions in healthy children aged 1 through 48 months. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1625–1628. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.11.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, jones LA, Friedman NE, Frane SL, Lin WK, et al. Axial growth and changes in lenticular and corneal power during emmetropization in infants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3074–3080. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Jones LA, Friedman NE, Frane SL, Lin WK, et al. Accommodation, acuity, and their relationship to emmetropization in infants. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:666–676. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181a6174f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarczy-Hornoch K. The epidemiology of early childhood hyperopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84:115–123. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318031b674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saunders KJ. Early refractive development in humans. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;40:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(95)80027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preferred Practice Pattern: Esotropia and Exotropia. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thibos LN, Wheeler W, Horner D. Power vectors: an application of Fourier analysis to the description and statistical analysis of refractive error. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74:367–375. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199706000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennie FC, Wood IC, Olsen C, White S, Charman WN. A longitudinal study of the biometric and refractive changes in full-term infants during the first year of life. Vision Res. 2001;41:2799–2810. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wood IC, Hodi S, Morgan L. Longitudinal change of refractive error in infants during the first year of life. Eye. 1995;9(Pt 5):551–557. doi: 10.1038/eye.1995.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giordano L, Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, Ibironke J, Hawes P, et al. Prevalence of refractive error among preschool children in an urban population: the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:739–746. 746, e731–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group Prevalence of myopia and hyperopia in 6- to 72-month-old African American and Hispanic children: the multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:140–147. e143. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Twelker JD, Mitchell GL, Messer DH, Bhakta R, Jones LA, Mutti DO, et al. Children's Ocular Components and Age, Gender, and Ethnicity. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:918–935. doi: 10.1097/opx.0b013e3181b2f903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Twelker JD, Mutti DO. Retinoscopy in infants using a near noncycloplegic technique, cycloplegia with tropicamide 1%, and cycloplegia with cyclopentolate 1%. Optom Vis Sci. 2001;78:215–222. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Black BC. The influence of refractive error management on the natural history and treatment outcome of accommodative esotropia (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;104:303–321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutcheson KA, Ellish NJ, Lambert SR. Weaning children with accommodative esotropia out of spectacles: a pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:4–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raab EL. Persisting accommodative esotropia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1986;84:94–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Repka MX, Wellish K, Wisnicki HJ. Changes in the refractive error of 94 spectacle-treated patients with acquired accommodative esotropia. Binocul Vis. 1989;4:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lepard CW. Comparative changes in the error of refraction between fixing and amblyopic eyes during growth and development. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:485–490. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rutstein RP, Corliss DA. Long-term changes in visual acuity and refractive error in amblyopes. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81:510–515. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200407000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith EL, Hung LF, Harwerth RS. Effects of optically induced blur on the refractive status of young monkeys. Vision Res. 1994;34:293–301. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith EL, Hung LF, Harwerth RS. Developmental visual system anomalies and the limits of emmetropization. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1999;19:90–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones LA, Mitchell GL, Mutti DO, Hayes JR, Moeschberger ML, Zadnik K. Comparison of ocular component growth curves among refractive error groups in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2317–2327. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]