Abstract

The interaction between interleukin-7 (IL-7) and its α-receptor, IL-7Rα, plays fundamental roles in the development, survival, and homeostasis of B- and T-cells. N-linked glycosylation of human IL-7Rα enhances its binding affinity to human IL-7 by 300-fold over the nonglycosylated receptor through an allosteric mechanism. The N-glycans of IL-7Rα do not participate directly in the binding interface with IL-7. This biophysical study involves dissection of the binding properties of IL-7 to both nonglycosylated and glycosylated forms of the IL-7Rα extracellular domain (ECD) as functions of salt, pH, and temperature using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy. Interactions of IL-7 to both IL-7Rα variants display weaker binding affinities with increasing salt concentrations primarily reflected by changes in the first on-rates of a two-step reaction pathway. The electrostatic parameter of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction is not driven by complementary charge interactions through residues at the binding interface or N-glycan composition of IL-7Rα, but presumably by favorable global charges of the two proteins. Van’t Hoff analysis indicates both IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions are driven by large favorable entropy changes and smaller unfavorable (nonglycosylated complex) and favorable (glycosylated complex) enthalpy changes. Eyring analysis of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions reveals different reaction pathways and barriers for the transition-state thermodynamics with the enthalpy and entropy changes of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα. There were no discernable heat capacity changes for the equilibrium or transition-state binding thermodynamics of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions. The results here suggest that the unbound nonglycosylated IL-7Rα samples an extensive conformational landscape relative to the unbound glycosylated IL-7Rα, potentially explaining the switch from a “conformational” controlled reaction (k1 ~102 M−1s−1) for the nonglycosylated interaction to a “diffusion” controlled reaction (k1 ~106 M−1s−1) for the glycosylated interaction. Thus, a large favorable entropy change, a global favorable electrostatic component, and glycosylation of the receptor—albeit not at the interface—contribute significantly to the interaction between IL-7 and IL-7Rα ECD.

The development, proliferation, and homeostasis of immune cells is orchestrated through numerous signaling pathways. At the heart of these signaling pathways are the interactions of soluble cytokines to membrane bound cytokine receptors on cellular surfaces. The external stimulus of a cytokine binding a cytokine receptor is relayed across the cell membrane to intracellular events ultimately altering the behavior of the targeted cell. While these binding events between cytokines and cytokine receptors are conceptually straightforward, the structural and molecular recognition principles underlying these interactions are complex and unpredictable. A further layer of complexity of the cytokine/cytokine receptor field involves pleiotropy—where cytokines or receptors are programmed to bind and function through multiple ligands.

The interleukin-7 (IL-7) signaling pathway is one of these critical cascades of the immune system. The IL-7 signaling pathway is triggered when IL-7 binds to the extracellular domains (ECDs) of its own specific α-receptor, IL-7Rα (CD127), and the common gamma chain receptor, γc (CD132) (reviewed in (1, 2)). The bringing together of the two cytokine receptors by IL-7 activates kinases on the intracellular domains of the receptors to phosphorylate themselves and other sequence elements leading to subsequent recruitment of transcription factors. Once the transcription factors interact with the intracellular domains of the cytokine receptors, the kinases phosphorylate the transcription factors, which subsequently from the cytokine receptor, oligomerize, and localize to the nucleus to elevate transcription and the cellular response (reviewed in (1, 2)). The IL-7 signaling pathway utilizes the JAK/Stat, PI3/Akt, and Src pathways to regulate cellular responses of immune cells (reviewed in (1, 2)).

The IL-7 signaling pathway contributes to early and late events during the immunological response. The IL-7 pathway is fundamental to the development of B-cell pools in mice and T-cell pools in mice and humans (reviewed in (1, 2)). Mutations of the ECD of IL-7Rα lead to forms of severe combined immunodeficiencies (SCIDs) with the phenotype of T− B− NK+ in mice and T− B+ NK+ in humans (3). After development of B- or T-cells, expression of IL-7Rα is down-regulated, and other γc family members play roles in the proliferation and differentiation of these immune cells (reviewed in (1)). After an immune response, IL-7Rα expression is upregulated and signaling occurs, which triggers anti-apoptotic factors of the bcl2/mcl1 lineage to generate memory cells (reviewed in (1)). Another biological role of the IL-7 signaling pathway involves extracellular matrix remodeling (reviewed in (4)). The IL-7Rα is a pleiotrophic cytokine receptor and functions in the thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) signal pathway, thereby promoting activation of B-cells in mice and dendritic cells (DCs) in humans (5). The precise mechanisms of action of IL-7 and IL-7Rα are evolving.

IL-7 and IL-7Rα are both glycoproteins. No studies have reported any O-linked glycosylation sites of either IL-7 or IL-7Rα. While IL-7 comprises three potential N-linked glycosylation sites (N70, N91, and N116), glycosylation does not affect IL-7’s binding to its receptors or function (6). The same cannot be said of N-linked glycosylation of the IL-7Rα. We have demonstrated that the IL-7Rα ECD uses N-linked glycosylation to modulate its binding properties with IL-7 (7). The functional relevance of IL-7Rα glycosylation is currently under investigation. There are six potential N-linked glycosylation sites of the IL-7Rα ECD: N29, N45, N131, N162, N212, and N213. All of these sites on the IL-7Rα ECD are glycosylated to varying degrees (unpublished results). The binding affinity of IL-7 to the glycosylated IL-7Rα is enhanced 300-fold over its binding affinity to the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα (Kds of 60 nM vs. 18 µM) (7). The 300-fold enhancement in the Kd of IL-7 to glycosylated IL-7Rα results primarily from an 5,200-fold faster association rate (k1 of 1.1 × 106 vs. 2.1 × 102 M−1s−1) (7). The binding constants of IL-7 to glycosylated IL-7Rα are not affected by carbohydrate composition, as demonstrated by similar binding constants for paucimannose hybrid (Schneider S2 insect cells) or complex (CHO cells) N-glycan structures (7). The most critical N-glycan components to the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding constants are the first N-acetylglucosamines (GlcNAcs) of the α-receptors’ N-glycans (7).

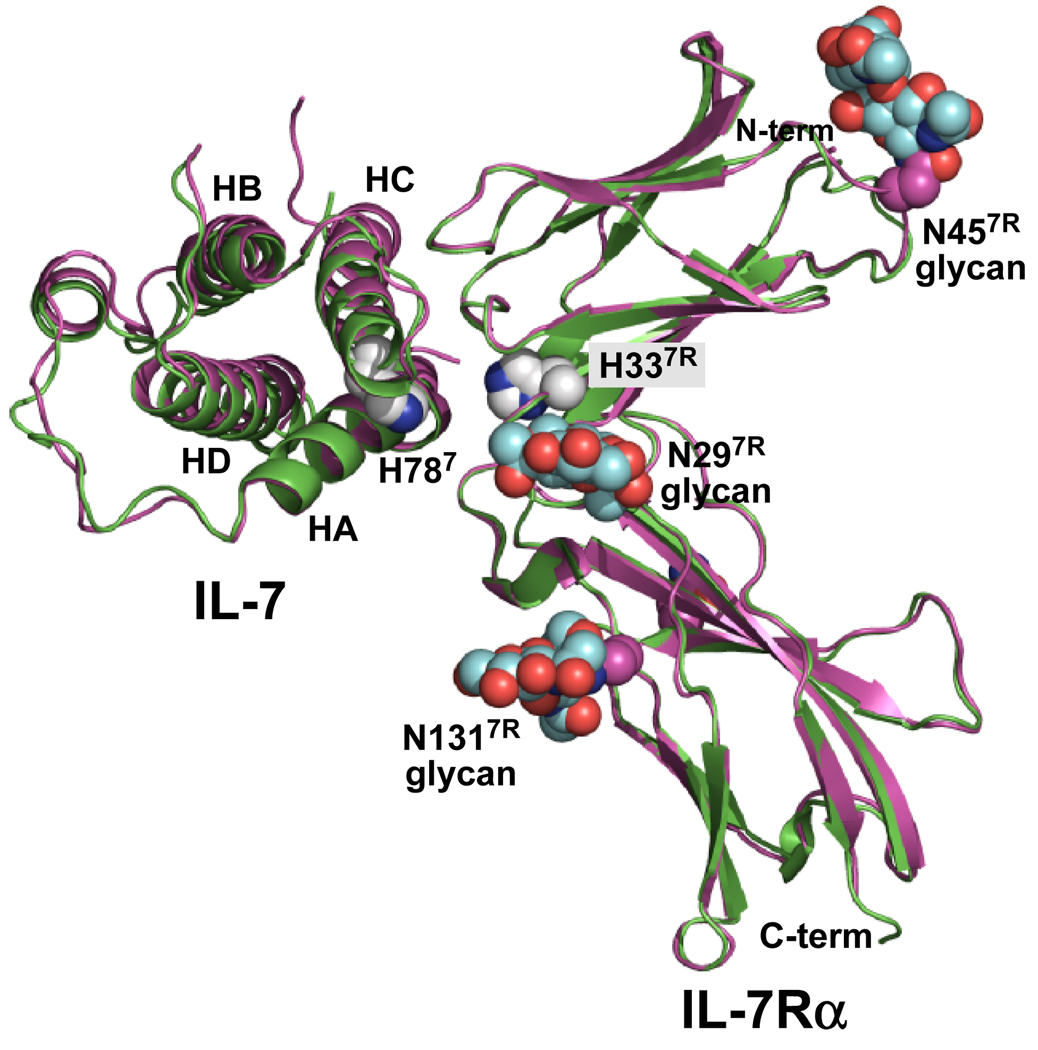

We also reported previously the crystal structure determinations of IL-7 bound to both nonglycosylated and glycosylated forms of the IL-7Rα ECD (7) (Fig. 1). Comparison of the two complex structures revealed no large conformational changes induced by glycosylation of IL-7Rα. Surprisingly, the N-glycans of IL-7Rα do not participate directly within the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interface. It was possible to visualize the first two GlcNAcs of the core N-glycans for N29, N45, and N131 of IL-7Rα. The closest N-glycan of N29 is >10 Å away from the closest atom of the interface. The other three N-glycans attached to N162, N212, and N213, although not observable in the electron density, are also distant from the IL-7/IL-7Rα interface. Thus, the contribution of glycosylation of IL-7Rα to the enhanced binding properties to IL-7 over the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα appears allosteric in nature.

Figure 1.

Ribbon diagrams of the complex structures of IL-7 bound to nonglycosylated (green, 3di2.pdb) and glycosylated (magenta, 3di3.pdb) forms of the IL-7Rα (7). The nonglycosylated complex was superimposed onto the glycosylated complex. The 4 α-helical bundle of IL-7 is labeled helix A (HA), B (HB), C (HC), and D (HD) accordingly. The N-glycans attached to N297R, N457R, and N1317R are colored as cyan CPK groups for the carbon atoms. The only histidine residues observed in the IL-7/IL-7Rα interface involve H787 and H337R. The histidine side chains are drawn as white CPK groups for the carbon atoms. Oxygen and nitrogen atoms are colored red and blue, respectively. This picture was created and rendered using PyMOL (58).

Providing further understanding into the allosteric mechanism of IL-7Rα glycosylation, this manuscript reports SPR binding studies of IL-7 to both nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα as functions of salt, pH, and temperature. The IL-7/IL-7Rα binding constants were probed by increasing sodium chloride concentrations to investigate the charge dependence and long-range electrostatic binding contributions. The effects of protonation on the binding constants were measured with increasing pH to investigate the two histidine residues in the binding interface (Fig. 1, one from IL-7, H787, superscript "7" denotes IL-7 residues, one from IL-7Rα, H337R, superscript "7R" denotes IL-7Rα residues). Temperature studies of the binding affinities using van't Hoff analysis provided a breakdown of IL-7 binding to both forms of IL-7Rα into the enthalpic and entropic components of the free energy changes. Temperature studies of the binding kinetics using Eyring analysis of IL-7 to IL-7Rα (EC = E. coli: for the nonglycosylated receptor; or CHO = for the glycosylated receptor) provided a quantitative analysis of the transition-state thermodynamics of the binding reaction pathways of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein expression and purification

The IL-7 proteins were expressed and purified from bacterial and S2 insect cells as described previously (8). Recombinant human IL-7Rα ECD from CHO cells was purchased from R&D Systems and used without further purification. The expression and purification of the wild-type human growth hormone receptor (hGHR) ECD from bacterial cells were performed as described previously (9, 10).

SPR data analysis

Experiments were performed using a Biacore 3000 SPR instrument. The IL-7Rα ECD coupling and binding kinetics were measured using CM5 sensor chips. Detailed SPR coupling strategies using amine or thiol chemistries have been described previously (7). Similar binding kinetics were observed for the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions using either amine- or thiol-coupled sensor chip surfaces (7).

Numerous SPR control experiments were performed for the binding interactions of IL-7 to both nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα, and they indicate mass transport effects were negligible. Non-specific binding was not observed when IL-7 was injected over the un-derivatized flow cell. SPR experiments were measured at a flow-rate of 50 µL min−1 and involved 2-fold serial dilutions of five IL-7 concentrations determined by the binding affinity to the IL-7Rα ECD. Each 250 µL protein or buffer injection was followed by a 400 sec dissociation period. The surfaces were regenerated for subsequent runs with a 5 µL injection of 4 M MgCl2. The running buffer was 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 0.005% Tween-20 for the temperature dependence experiments. The same buffer was used for the ionic strength dependence experiments with the exception of changing the NaCl concentrations. For the pH experiments, either 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 10 mM MES (pH 6.0–6.5), or 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.0–8.0) was used as the buffering chemical supplemented with 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 0.005% Tween-20. The salt and pH binding experiments were performed at 298 K.

Sensorgrams were trimmed and double referenced (11) using BIAevaluation 4.1 before data analysis. The IL-7 binding interaction to IL-7Rα coupled surfaces fit best to a two-step (three-state) reaction model (7) originally described for SPR analysis by (11):

| (1) |

Apparent equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

Sensorgrams were globally analyzed using ClampXP (12) and the binding kinetic parameters were determined from at least three separate experiments. Errors were propagated using Taylor series expansion described in detail by (13).

Circular dichroism

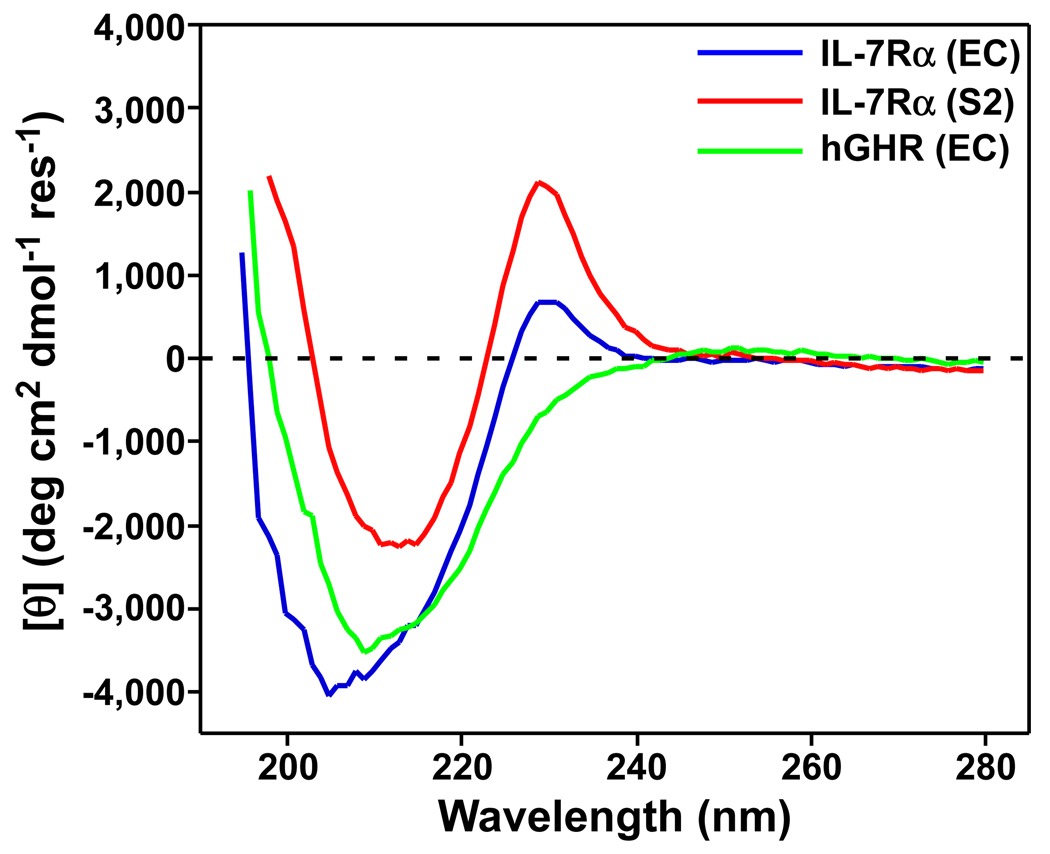

CD experiments were performed on an Aviv 62A DS spectropolarimeter (Aviv Biomedical, Inc.). The nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα from E. coli and S2 insect cells and the hGHR ECD were buffer-exchanged into 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4) using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare). CD wavelength scans were collected at 298 K from 186–280 nm with an 1 nm increment and a 20 sec averaging period. The receptor protein concentrations were 16 µM, 15 µM, and 13.2 µM for IL-7Rα (EC), IL-7Rα (S2), and hGHR, respectively. The CD wavelength scans were recorded in 0.1 cm cells and buffer wavelength scans were subtracted from the protein scans. Mean residue ellipticities were calculated using the relation, [θ] = θobs/10lcn, where θobs is the ellipticity measured in millidegrees, l is the path length of the cell in centimeters, c is the concentration in M, and n is the number of protein residues.

RESULTS

NaCl dependence of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions

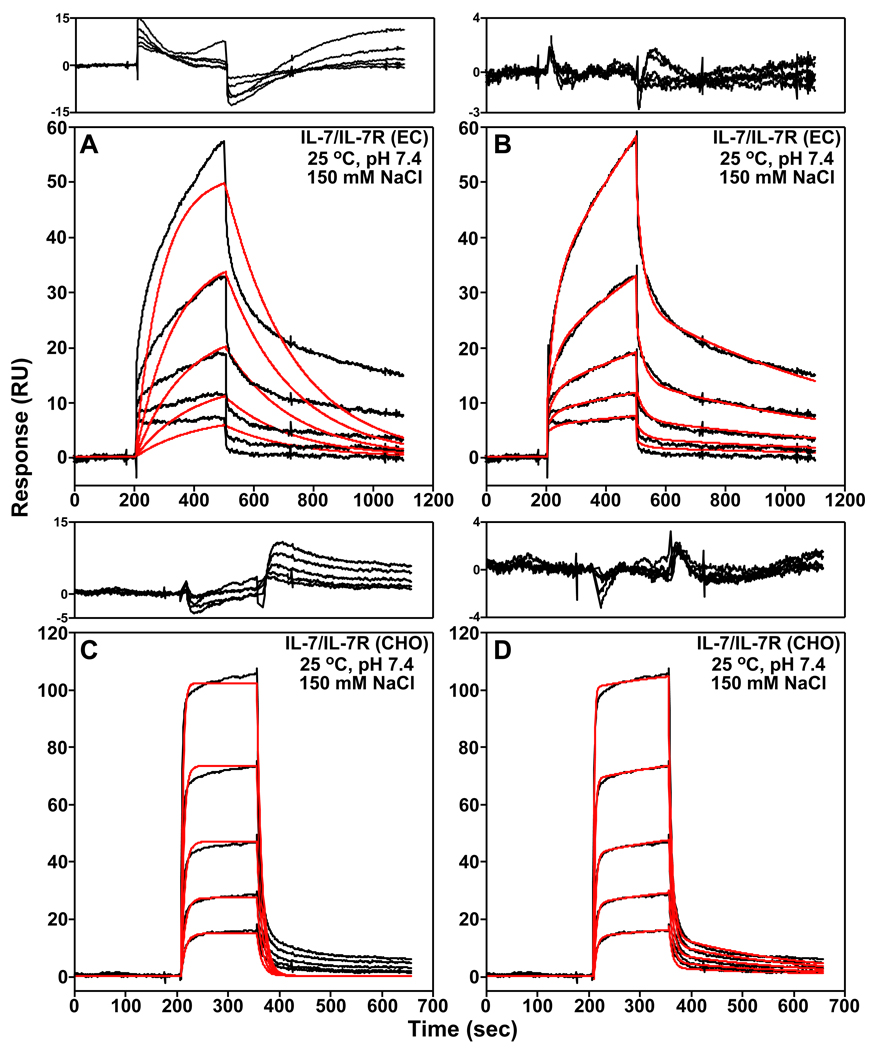

To assess the role of electrostatics to the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interaction, the binding kinetics and affinities of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα were measured as a function of increasing NaCl concentrations using SPR spectroscopy. Assays were performed in sodium chloride concentrations of 50, 150, 300, 600, and 1000 mM were assayed at 298 K. For the IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction, reliable binding constants could only be obtained up to a NaCl concentration of 300 mM because the IL-7 binding interaction to the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα (EC) becomes too weak at higher concentrations. Binding constants were obtained over the entire NaCl concentration range for the IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) glycosylated interaction. The SPR sensorgrams from all experiments fit best to a two-step binding kinetic reaction model where IL-7 and its receptor first form an "encounter complex" and second form the final IL-7/IL-7Rα complex. Fig. 2 displays representative SPR sensorgrams (150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, and 298 K) for the nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interactions and global analysis curve fitting to an one- and two-step binding reaction models. The binding constants are summarized in Tables S1 and S2 of the supporting information.

Figure 2.

Examples of the SPR binding kinetics of IL-7 to both nonglycosylated (EC, A and B) and glycosylated (CHO, C and D) forms of the IL-7Rα in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 0.005% Tween-20 at 298 K. The black curves are trimmed and buffer subtracted binding sensorgrams. Two-fold serial dilutions of IL-7 were performed starting at 2.5 µM for the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction and 100 nM for the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction. Also displayed is the global analysis of the sensorgrams analyzed to an one-step (A and C) or a two-step (B and D) binding reaction model using ClampXP (12) and depicted as red curves. The residuals of the global fitting analysis for each binding mechanism are plotted above the sensorgrams. Note that the residual y-axes scales for the two-step binding reactions models are smaller in A and C than the residual y-axes scales for the one-step binding reaction models in B and D.

At 150 mM NaCl and 298 K, the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα complex displays k1, k−1, k2, and k−2 rates of 3.26 ± 0.82 × 102 M−1s−1, 3.73 ± 0.40 × 10−2 s−1, 4.63 ± 0.35 × 10−3 s−1, and 1.44 ± 0.084 × 10−3 s−1, respectively. The binding affinity (Kd) determined using eq. 2 for this interaction is 27.1 ± 13 µM, which corresponds to a free energy change (ΔGo) of −6.2 ± 0.2 kcal mol−1. The glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) binding interaction displays 6900-fold faster k1 rate than the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interaction. The glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) complex has a Kd of 109 ± 15 nM, which corresponds to a ΔGo of −9.5 ± 0.1 kcal mol−1, a binding enhancement of −3.3 kcal mol−1 over the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα complex. These values are similar to our previously published results also performed at 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, and 298 K (7).

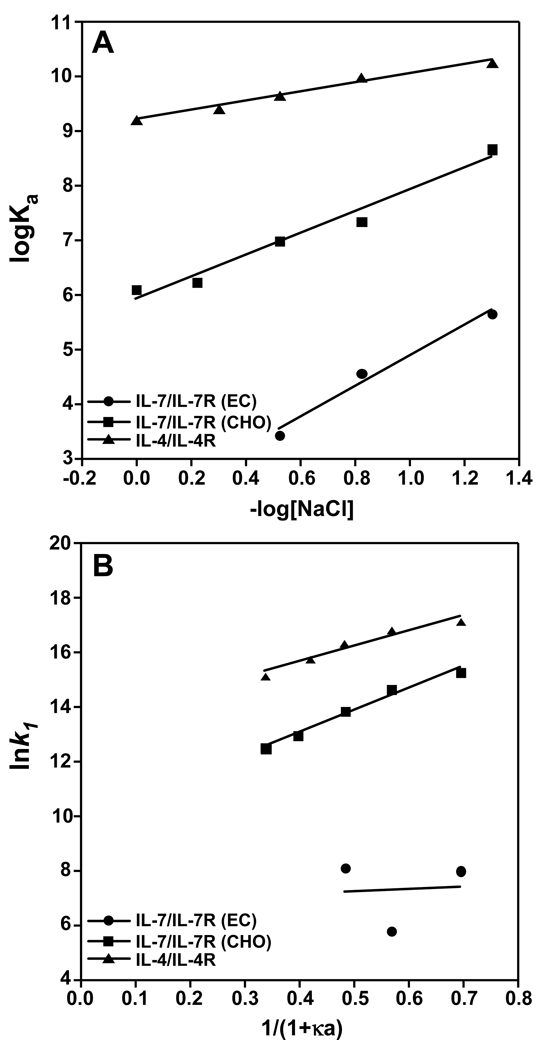

The NaCl binding data were analyzed using an ion-linkage mechanism (14) where the logarithm of the equilibrium constant, Ka (= 1/Kd), is plotted against the negative logarithm of the NaCl concentration. The data fit best to a linear function of the form

| (3) |

where the slope indicates weaker (positive) or stronger (negative) binding with increasing NaCl concentration. The slope, n, gives the number of sodium or chloride ions taken up or released upon complex formation during either the association or dissociation steps. Interactions of IL-7 to nonglycosylated (filled circles, R2 = 0.98) or glycosylated (filled squares, R2 = 0.97) IL-7Rα display linear dependencies with positive slopes, indicating weaker binding affinity with increasing NaCl concentrations (Fig. 3A). The nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) binding interaction has a slightly higher n value of 2.8 relative to 2.0 for the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) binding interaction. The binding interaction of IL-7 with IL-7Rα demonstrates a strong favorable electrostatic dependence that is independent of N-linked glycosylation of IL-7Rα.

Figure 3.

Binding interactions of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα and IL-4 to IL-4Rα as a function of salt at pH 7.4 and 298 K. The IL-4/IL-4Rα data were taken from Sebald and coworkers (15). (A) The equilibrium binding constants (Ka) plotted against increasing NaCl concentrations for nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC, filled circles), glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO, filled squares), and IL-4/IL-4Rα (filled triangles). The data displayed a linear correlation between Ka with increasing NaCl concentrations. (B) Natural logarithm of k1 versus NaCl concentration expressed as 1/(1+κa) displaying an electrostatic enhancement for the IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) and IL-4/IL-4Rα interactions. The data were fit using linear regression with the slopes (−U/RT) relating to the electrostatic energy of interaction to the first association phase (k1) and the intercept giving the basal on-rate, . The electrostatic contributions (−U/RT) and rate constants are listed in Table 1.

For a direct comparison to another γc cytokine/receptor interaction, the salt dependence of the IL-4/IL-4Rα binding interaction (filled triangle) from a previous study by Sebald and coworkers (15) was plotted in Fig. 3A. Of note, binding constants of IL-4 to either nonglycosylated or glycosylated forms of IL-4Rα (E. coli, insect, or CHO cells) were similar (15). IL-4 also displays a linear dependence (R2 = 0.98) with weaker binding affinity to IL-4Rα with increasing concentrations of NaCl, but has a smaller n value of 0.84 compared to the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interactions. In other binding interactions of a T-cell receptor ectodomain with peptide targets, these protein-peptide interactions displayed values ranging from 0.2 to 0.4 (16). The binding interactions of nucleic acid binding proteins to DNA or RNA are typically characterized by strong electrostatic components with n values on the order of 2–25 ions (14). The strength of the electrostatic component of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction is more similar to a nucleic acid-protein interaction than a cytokine/receptor interaction.

To provide further quantitative insights into the role of electrostatics in the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interaction, the individual rate constants were analyzed as a function of increasing NaCl concentrations from 50 mM to 1 M. Previous studies of protein-ligand interactions have demonstrated strong electrostatic components to the first kinetic k1 on-rates with increasing ionic strength (reviewed in (17)). A linear dependence has been observed for the k1 on-rates with increasing ionic strength that follows Debeye-Hückel theory using the following relationship:

| (4) |

where κ is the inverse of the Debeye-Hückel screening distance at a given salt concentration and a is 6 Å, the minimal distance of approach for protein-protein interactions in the transition-state (18–21). The value defines the basal on-rate in the absence of any electrostatic component. The electrostatic component to the k1 constant is defined as −U/RT under increasing salt concentration.

A plot of lnk1 versus 1/(1+κa) yields a y-intercept reflecting the basal rate constant and a slope reflecting the electrostatic energy as −U/RT. Fig. 3B shows this plot for the IL-7/IL-7Rα and IL-4/IL-4Rα binding interactions. For IL-7 binding to the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα (EC), only three data points could be analyzed because the binding kinetics and affinities are too weak above 300 mM NaCl. Poor linear regression (R2 = 0.11) of these data suggests a small electrostatic component (−U/RT) of 0.90 ± 0.1 and a basal rate of 8.6 ± 1.2 × 102 M−1 s−1 for IL-7 binding to nonglycosylated IL-7Rα (EC, Table 1). An −U/RT of 8.1 ± 0.7 and a basal rate of 1.8 ± 0.6 × 104 M−1 s−1 were obtained for IL-7 binding to glycosylated IL-7Rα (CHO, R2 = 0.98). In comparison to the IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction, the IL-4/IL-4Rα interaction has a smaller −U/RT value of 5.7 ± 0.8, but a 35-fold faster basal rate of 6.3 ± 2.7 × 105 M−1s−1 (R2 = 0.94). The electrostatic components (−U/RT) observed for glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) and IL-4/IL-4Rα binding interactions fall in the middle of observed values for a TCR-A6 peptide complex of 1.9 (16) to that of the nonglycosylated erythropoietin-receptor complex of 18 (22).

Table 1.

Electrostatic contribution to the k1 rate constant1

| Interaction | −U/RT (kcal mol−1) | (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| IL-7/IL-7R (EC) | 0.90 ± 0.1 | 8.6 ± 1.2 × 102 |

| IL-7/IL-7R (CHO) | 8.1 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.6 × 104 |

| IL-4/IL-4R | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 6.3 ± 2.7 × 105 |

−U/RT were obtained from the slopes of the lines from Fig. 3B. Binding kinetics were measured at pH 7.4 and 298 K.

There is a general trend of faster k−1 rates for IL-7 binding both the nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα with increasing ionic strength, which leads to faster dissociations of the encounter complexes (Supporting Fig. 1A). For example, the k−1 rates for IL-7 to IL-7Rα (EC) increased 3-fold as the concentration of NaCl increased from 50 mM to 300 mM (3.73 vs. 12.1 × 10−2 s−1). Similarly, the k−1 rates increased 15-fold as the concentration of NaCl increased from 50 mM to 1 M. For the IL-4/IL-4Rα interaction, which displays single-step Langmuir binding kinetics with a single kon and koff rate constants, the koff rates do not change significantly (2-fold, 1.54 vs. 2.25 × 10−3 s−1) as the concentration of NaCl increases from 50 mM to 1 M (15).

The second step of the binding kinetics (k2 and k−2)—the transition from the encounter complex to the final IL-7/IL-7Rα complex—displays smaller changes with increasing ionic strength than observed for k1 (Supporting Figs. 1B and 1C). The k2 rates change 2- and 9-fold from the lowest to highest NaCl concentrations for the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) and glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) complexes, respectively. The IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) nonglycosylated complex displays faster k−2 rates of 3-fold as the concentration of NaCl increased from 50 mM to 300 mM NaCl. In contrast, the IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) glycosylated complex displays slower k−2 rates of 15-fold as the concentration of NaCl increased from 50 mM to 1 M ( 15-fold slower). Thus, the data highlight a favorable long-range electrostatic contribution, primarily through the k1 rate, to the overall binding affinity (Kd) of the interaction of IL-7 with IL-7Rα.

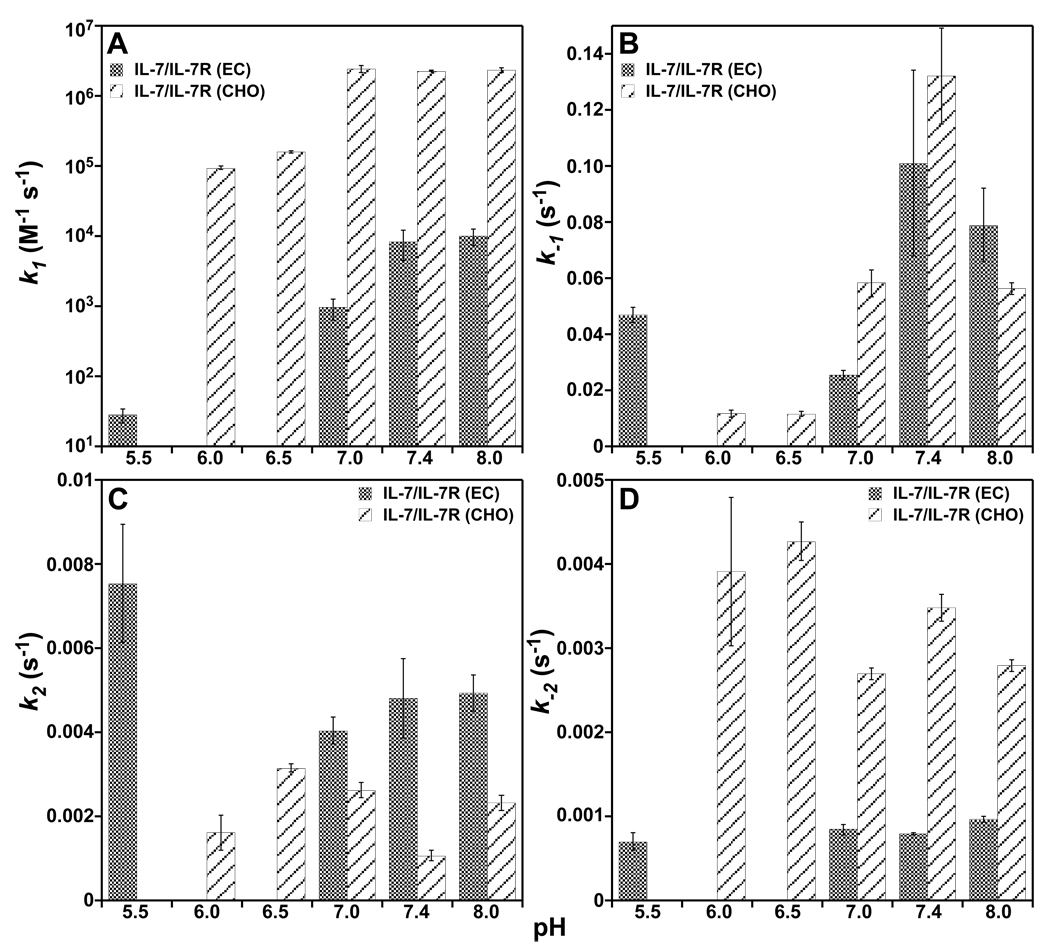

pH dependence of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions

Crystal structures of IL-7 bound to both nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα revealed two histidine residues in the binding interface, which may display a pH dependence upon interacting at physiological conditions. These histidine residues are H787 of IL-7 and H337R of IL-7Rα (Fig. 1) (7). For IL-7, the side chain Nδ1 of H787 forms an intramolecular hydrogen bond with side chain Oγ of S197 (2.9 Å) in both structures. His787 buries only 6 Å2 of surface area in both complex structures. Similarly, the side chain Nδ1 of H337R forms an intramolecular hydrogen bond to the backbone nitrogen of E277R (2.9 Å) in both structures. His337R also buries 5 Å2 of surface area in both complex structures. The binding kinetics of IL-7 interacting with nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα ECDs as a function of pH from 5.5 to 8.0 are displayed in Fig. 4, and binding constants are listed individually in Supporting Tables S1 and S2.

Figure 4.

Binding kinetic constants, k1, k−1, k2, and k−2, of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα as a function of pH at 150 mM NaCl and 298 K. (A) Bar graphs of k1 constants versus pH. (B) Bar graphs of the k−1 constants versus pH. (C) Bar graphs of k2 constants versus pH. (D) Bar graphs of the k−2 constants versus pH.

The largest magnitude changes in the rate constants as a function of pH are reflected in the k1 rates of IL-7 interacting with nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα. There was a 294-fold faster k1 rate going from pH 5.5 to 7.4 for nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) (0.282 × 102 vs. 83.0 × 102 M−1s−1). There was a smaller 24-fold faster change in the k1 rate going from pH 6.0 to 7.4 for the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) (0.0935 × 106 vs. 2.25 × 106 M−1s−1). The k−1, k2, and k−2 rates for the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction displayed less than 2-fold changes over the pH range of 5.5 to 8.0. The k−1, k2, and k−2 rates for the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction exhibited 2- to 11-fold changes over the pH range of 6.0 to 8.0. The rates constants are typically faster for the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction than the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction as a function of pH with the exception of the k2 rate (Fig. 4). Analysis of the pH data using a linkage mechanism as described above for the salt dependence yields linear fits from plots of logKa versus pH with slopes of 0.86 and 0.34 for the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC, R2 = 0.96) and glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO, R2 = 0.71) interactions, respectively. These results indicate that one proton is either taken up or released when IL-7 binds to the IL-7Rα, depending on the glycosylation state of the receptor. Further investigation into the pH dependence of IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions will be performed using isothermal titration calorimetry (23).

Equilibrium temperature dependence of the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interactions

The SPR binding kinetics and affinities of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα were measured over a temperature range from 283 to 308 K. The individual binding constants as a function of temperature are listed in Supporting Tables S1 and S2. The overall binding equilibrium constants (eq. 2) were plotted over the temperature range using van't Hoff analysis as described by following equation:

| (5) |

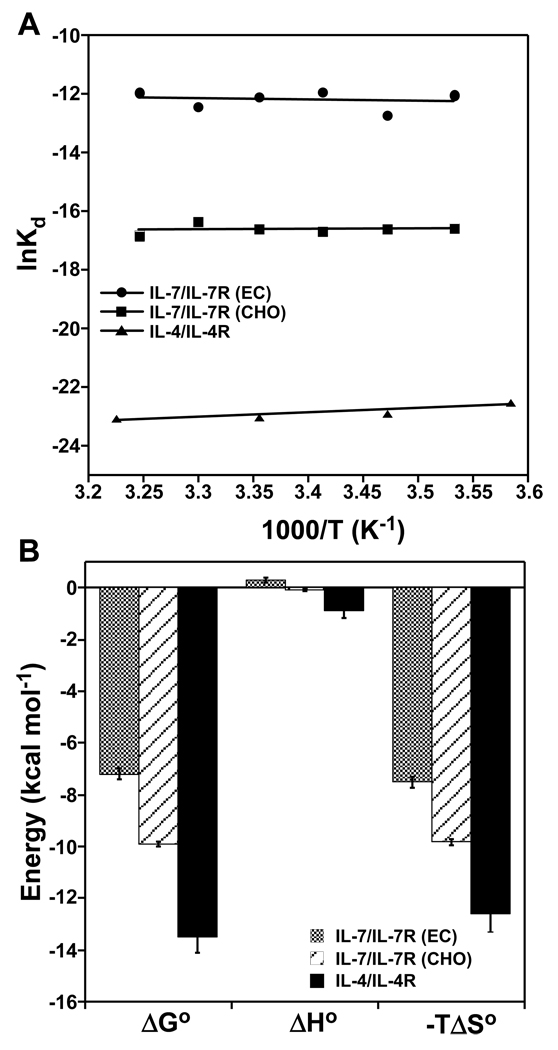

where the slope and y-intercept are the binding enthalpy (ΔHo) and entropy (ΔSo) changes, respectively. Fig. 5A illustrates van't Hoff plots for the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions, as well as analysis of the IL-4/IL-4Rα interaction using previously published temperature-dependent SPR binding constants (15). All three binding interactions fit well using linear regression, indicating that ΔHo is independent of temperature. Thus, there appears to be no or small heat capacity changes (ΔCp = ΔHo/ΔT) upon complex formation that can be detected using SPR analysis (discussed in greater detail below in the Discussion section).

Figure 5.

Equilibrium binding constants of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα and IL-4 to IL-4Rα as a function of temperature at 150 mM NaCl and pH 7.4. (A) van't Hoff analysis plotted as lnKd versus 1/T (K−1). Data fit well using linear regression for nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC, filled circles), glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO, filled squares), and IL-4/IL-4Rα (filled triangles). (B) Bar graphs of the equilibrium thermodynamic parameters obtained from van't Hoff analysis for these interactions. These parameters are listed in Table 2. The ΔGo values are reported at 298 K.

The thermodynamic parameters governing the binding interactions of IL-7 to nonglycosylated or glycosylated IL-7Rα are defined by large favorable entropic contributions rather than enthalpic components. The nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) binding interaction has a small unfavorable enthalpy (ΔHo) change of 0.31 ± 0.09 kcal mol−1 and a large favorable entropy (−TΔSo) change of −7.5 ± 0.2 kcal mol−1 (Fig. 5B and Table 2). The glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) binding interaction has a slightly favorable ΔHo of −0.079 ± 0.042 kcal mol−1 and a higher favorable −TΔSo of −9.8 ± 0.1 kcal mol−1. The IL-4/IL-4Rα interaction displays a small favorable ΔHo of −0.88 ± 0.31 kcal mol−1 and a large favorable −TΔSo of −12.6 ± 0.7 kcal mol−1.

Table 2.

Equilibrium binding thermodynamics for IL-7 and IL-4 interactions

| Interaction |

1ΔGo (kcal mol−1) |

ΔHo (kcal mol−1) |

−TΔSo2 (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-7/IL-7R (EC) | −7.2 ± 0.2 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | −7.5 ± 0.2 |

| IL-7/IL-7R (CHO) | −9.9 ± 0.1 | −0.079 ± 0.042 | −9.8 ± 0.1 |

| IL-4/IL-4R | −13.5 ± 0.63 | −0.88 ± 0.31 | −12.6 ± 0.7 |

ΔGo reported at 298 K. Experiments were performed with 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.4.

Calculated using −TΔSo = ΔGo − ΔHo.

Value taken from Table 2 from (15).

Temperature dependence of the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding kinetics

A deeper understanding into the IL-7 binding reactions to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα was gained through characterization of their transition-state binding thermodynamics. The free energy changes of activation for both reaction steps were broken down into their enthalpic and entropic components using Eyring analysis as described by the following equation (24, 25):

| (6) |

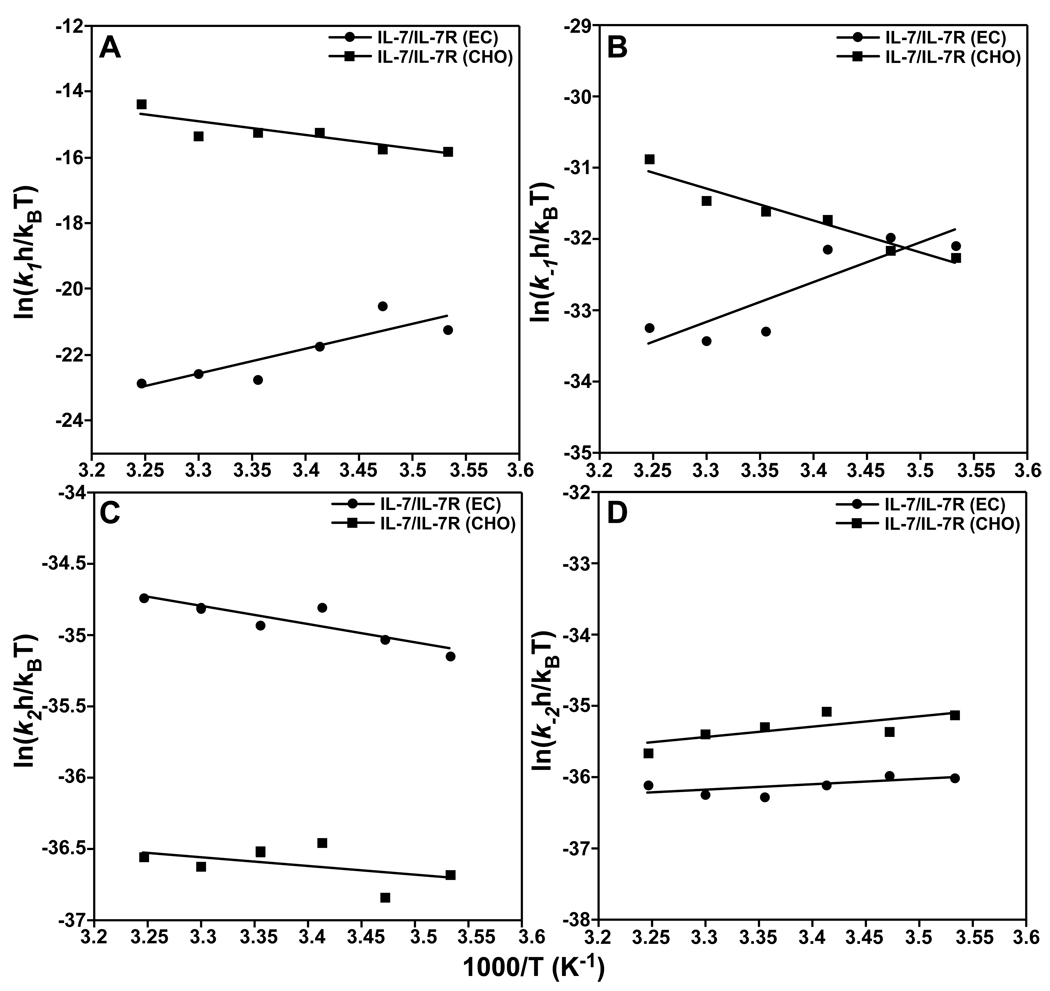

where k is the individual on- and off-rate constants (k1, k−1, k2, and k−2), h is Plank’s constant, kB is Boltzman’s constant. The slope of an Eyring plot (eq. 6 versus 1/T) gives ΔHo‡/R and the y-intercept gives ΔSo‡/R for the individual kinetic pathway. However, it is often more accurate to calculate the entropy of activation (ΔSo‡) from ΔGo‡ = ΔHo‡ – TΔSo‡ (25). Eyring plots of the transition-state binding thermodynamics of the IL-7/receptor interactions are provided in Fig. 6 and the individual values are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 6.

Eyring analysis of the kinetic rate constants of IL-7 to nonglycosylated (filled circles) and glycosylated (filled squared) IL-7Rα as a function of temperature at 150 mM NaCl and pH 7.4. The data were plotted as ln(kxh/kBT) versus 1/T (K−1) where kx are the individual rate constants (k1 (A), k−1 (B), k2 (C), and k−2 (D)), h is Plank’s constant, and kB is Boltzman’s constant (59). Data fit well using linear regression. The slopes and intercepts yield transition-state enthalpies (ΔHo‡/R) and entropies (ΔSo‡/R) for the individual association and disassociation pathways and are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Transition-state binding thermodynamics for IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions

| Reaction |

1ΔGo‡ (kcal mol−1) |

ΔHo‡ (kcal mol−1) |

−TΔSo‡2 (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-step k1 | |||

| IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) | 13.5 ± 0.2 | −15.1 ± 4.4 | 28.6 ± 2.4 |

| IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) | 9.04 ± 0.1 | 8.3 ± 2.4 | 0.75 ± 2.4 |

| First-step k−1 | |||

| IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) | 19.7 ± 0.1 | −11.1 ± 3.1 | 30.8 ± 2.4 |

| IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) | 18.7 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 9.8 ± 1.2 |

| Second-step k2 | |||

| IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) | 20.7 ± 0.04 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 18.1 ± 1.2 |

| IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) | 21.7 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 20.5 ± 1.0 |

| Second-step k−2 | |||

| IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) | 21.5 ± 0.1 | −1.5 ± 0.9 | 23.0 ± 1.0 |

| IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) | 20.9 ± 0.1 | −2.8 ± 1.3 | 23.7 ± 0.9 |

ΔGo‡ parameters reported for 298 K. Experiments were performed with 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.4.

Calculated using −TΔSo‡ = ΔG‡ − ΔH‡.

The binding of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα exhibits differing transition-state binding thermodynamics. The Eyring plots of the binding kinetics of IL-7/IL-7Rα reactions all fit well using linear regression, indicating no measurable transition-state heat capacity changes (ΔC‡p) during the association or dissociation phases. As with the equilibrium ΔCp changes above, there may be small ΔC‡p changes during the reaction pathways of IL-7/IL-7Rα, but they cannot be detected in the analysis of the SPR data. During the first-step of forming the encounter complex of IL-7 binding to IL-7Rα, the association ΔHo‡k1 values have opposite signs for the glycosylated and nonglycosylated IL-7Rα. The IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction has a ΔHo‡k1 of −15.1 ± 4.4 kcal mol−1 and the IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction has a ΔHo‡k1 of 8.3 ± 2.4 kcal mol−1. A similar trend is observed for the dissociation ΔHo‡k−1 changes for the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions. The IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction has a ΔHo‡k−1 of −11.1 ± 3.1 kcal mol−1 and the IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction has a ΔHo‡k−1 of 9.0 ± 1.2 kcal mol−1. The second step of the reaction going from the encounter complex to the final complex displays similar transition-state enthalpies (ΔHo‡k2 and ΔHo‡k−2) for both the association (2.6 vs. 1.2 kcal mol−1) and dissociation (−1.5 vs. −2.8 kcal mol−1) of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα.

The transition-state binding entropies (−TΔSo‡) demonstrate the largest differences, once again, in the first step going from the unbound proteins to the encounter complexes of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions. As noted previously, the transition-state entropies were calculated from −TΔSo‡ = ΔGo‡ − ΔHo‡ and not from the y-intercepts of the Eyring plots. During the association phase of the first step of the reaction, the IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction has a 38-fold higher −TΔSo‡k1 than the IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction (28.6 vs. 0.75 kcal mol−1). The IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction also has a 3-fold higher −TΔSo‡k−1 than the IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction during the dissociation phase (30.8 vs. 9.8 kcal mol−1). Similar transition-state entropies of the association and dissociation phases were observed for the second step of the reaction going from the encounter complexes to the final bound states. The −TΔSo‡k2 values were 18.1 ± 1.2 and 20.5 ± 1.0 kcal mol−1 for the IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) and IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interactions, respectively. The −TΔSo‡k−2 values were 23.0 ± 1.0 and 23.7 ± 0.9 kcal mol−1 for the IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) and IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interactions, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Electrostatics of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions

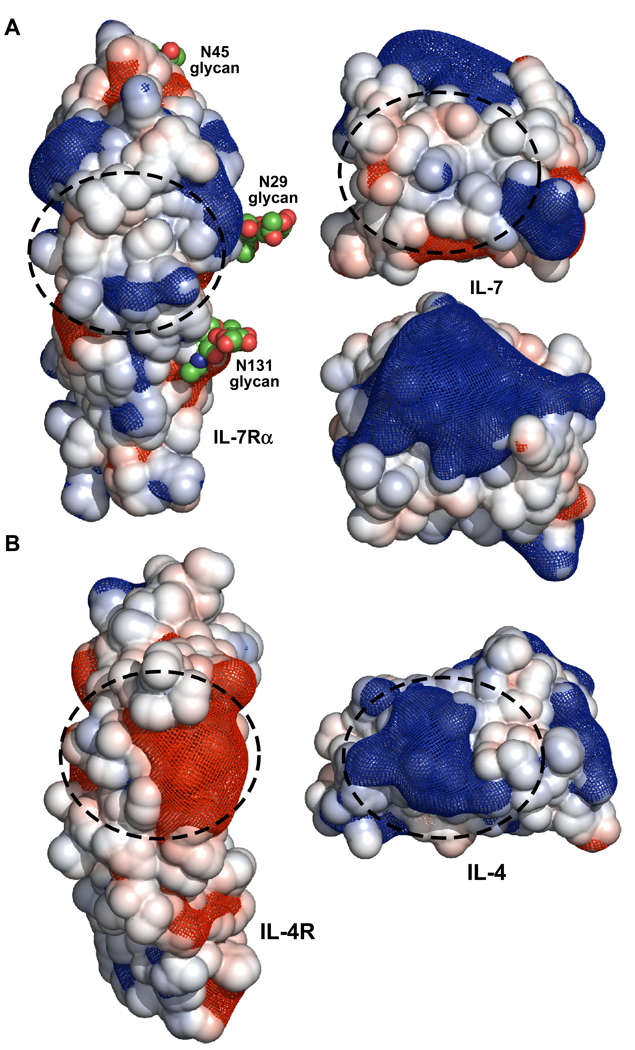

This study demonstrates that electrostatics play an influential role in the binding interaction between IL-7 and IL-7Rα, even though the IL-7/IL-7Rα interface does not consist of multiple complementary charged residues as typically seen for electrostatically tuned protein-ligand interfaces (reviewed in (17)). The complex structures of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα revealed the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interface to be the smallest (average of 740 Å2 of buried surface area), mostly apolar in nature (47% apolar vs. 33% polar residues), and least specific (4–5 intermolecular hydrogen bonds with one salt bridge and an average shape complementarity (Sc) value of 0.69) relative to other complex structures solved of γc family members (e.g. IL-2 and IL-4, Fig. 7) (7). The IL-4/IL-4Rα binding interaction, which serves as a model system for studying favorable electrostatic steering mechanisms (reviewed in (17)), allows for a direct comparison to another cytokine-receptor interaction in the same family. Structural analysis of IL-4/IL-4Rα complexes (binary and ternary complexes) shows the IL-4/IL-4Rα interface buries on average 807 Å2 of surface area (26, 27). The IL-4/IL-4Rα interface consists of polar residues (43% polar vs. 27% apolar), has 14–15 intermolecular hydrogen bonds (depending on complex structure analyzed), and Sc scores of 0.74 (26, 27). Furthermore, numerous complementary charged residues line the IL-4/IL-4Rα interface (26, 27) (Fig. 7B). Glycosylation of either IL-4 or IL-4Rα ECD does not alter their binding affinities or functional responses (15, 28).

Figure 7.

Open book view of the electrostatic surfaces and potentials for the IL-7/IL-7Rα (A) and IL-4/IL-4Rα (B) complexes. The linear Poisson-Boltzmann equation was solved for both protein complexes using APBS (33) with 150 mM monovalent salt at 298 K. The solvent accessible surface areas for each protein are displayed and colored blue (+5 kT/e) and red (−5 kT/e). The electrostatic potential gradients for each protein are displayed as a blue (+2 kT/e) and red (−2 kT/e) mesh. The structures and electrostatic potentials were displayed using PyMOL (58). The binding interfaces for both complexes are highlighted with dashed circles. The second view of IL-7 below the view with the dashed circle is rotated 90° in the vertical direction to illustrate the large positive surface on the top of the cytokine.

The electrostatic parameters of the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interactions were measured by SPR responses with increasing concentrations of salt. Increased ionic strength screens electrostatic effects of binding interactions. The Kds of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα decreased with increasing ionic strength (Fig. 3A). For example, the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) binding affinity change (ΔGo at 298 K) decreased from −7.72 to −4.68 kcal mol−1 as the concentration of NaCl increased from 50 to 300 mM. Above 300 mM NaCl, no binding of IL-7 to the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα (EC) was detected. Similarly, the binding affinity change (ΔGo at 298 K) of IL-7 to the glycosylated IL-7Rα (CHO) decreased from −11.8 to −8.33 kcal mol−1 as the concentration of NaCl increased from 50 mM to 1 M. Analyzing the binding affinities of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions versus salt concentrations using an ion-linkage mechanism (eq. 3) highlighted that 2–2.8 ions are taken up or released upon complex formation, which is higher ion uptake or release measured for the IL-4/IL-4Rα interaction of 0.8. The ion consumption or expulsion during IL-7/IL-7Rα formation approaches that of nucleic acid binding proteins (2–25 ions), which bind negatively charged surfaces of the phosphate backbones of nucleic acids (14). Future studies will investigate ion-linkage (salt and pH) mechanisms of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions using isothermal titration calorimetry (23).

The electrostatic attraction observed for the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions affects the first k1 on-rate more than the other kinetics rates of k−1, k2, or k−2. A linear dependence of k1 on increasing NaCl concentrations was reflected in a plot of lnk1 versus 1/(1+κa) following Debeye-Hückel theory (18) for the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) and IL-4/IL-4Rα interactions (Fig. 3B). The k1 dependence on NaCl of the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction could not be reliably measured due to weakened binding constants above 300 mM NaCl. The slope of the plot of lnk1 versus 1/(1+κa) gives −U/RT, which is the electrostatic energy enhancement. The −U/RT values of 8.1 and 5.7 for the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα and IL-4/IL-4Rα interactions, respectively, fall in the middle of the range observed for other protein-ligand interactions. For example, the interactions of barnase/barstar (20, 29), Ifnar2/Interferon α2 (30), TEM1/BLIP (20), hirudin/thrombin (19, 31), heterodimeric leucine zipper (32), and nonglycosylated EPO/EPOR (22) have −U/RT values of 7.5, 4, 2.5–3, 13.8, 12, and 18.0, respectively. Furthermore, a protein engineering study by Schreiber and coworker increased the −U/RT electrostatic energy of the TEM1/BLIP(+6) interaction to 11–12 by introducing several surface exposed basic residues into the BLIP protein sequence located outside of the binding interface, demonstrating the long-range non-specific nature of electrostatics (20).

The contribution of electrostatics to the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions suggests that global long-range electrostatic charges not localized at the binding interface are responsible for the observed effects. There is one salt bridge at the periphery of the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interface between D747 Oδ2 and K777R Nζ (ranging from 2.9–3.2 Å for the two nonglycosylated and one glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα structures) (7). By primary sequence analysis, IL-7 is a basic protein with an isoelectric point (pI) of 8.5 and the IL-7Rα ECD is an acidic protein with a pI of 5.4. A similar trend occurs with IL-4 (pI 9.0) and IL-4Rα ECD (pI 5.1). Using default parameters in APBS (33), the linear Poisson-Boltzman equation was solved for both IL-7/IL-7Rα and IL-4/IL-4Rα complexes at a concentration of 150 mM salt concentration (singly charged molecules) at 298 K. The electrostatic accessible surface areas (displayed at ±5 kT/e) and gradient field potentials (mesh contoured at ±2 kT/e) are displayed in Fig. 7 as open-book views of IL-7/IL-7Rα and IL-4/IL-4Rα interfaces. Clearly, the basic charged residues of IL-4 contact the acidic charged/hydrophobic residues of IL-4Rα at the binding interface, thus providing a clear rationale explanation of the observed electrostatic enhancement of the on-rate (Fig. 7B). Unlike the IL-4/IL-4Rα interface, the IL-7/IL-7Rα interface is predominately apolar in nature, and complementary electrostatic field gradients of the two binding surface do not drive the association (Fig. 7A). The negative charge and field potential of IL-7Rα is distributed throughout the molecule and concentrated on the backside of the receptor away from the binding interface with IL-7. The positive charge and field potential of IL-7 localizes to a few residues at the amino-terminus and to the top part of the molecule (in Fig. 7A the IL-7 molecule is rotated 90° to highlight this feature). The concentration of basic residues on the top of IL-7 is predicted to interact with negatively charged glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), such as heparin and heparin-sulfate (unpublished data). We have begun an alanine-scanning study of the basic residues of IL-7 to map the binding site to GAGs. Previously, Schreiber and coworkers demonstrated that increasing the number of basic residues of BLIP that were engineered outside the binding interface of TEM1/BLIP increased the binding affinity of these two proteins through faster kon rates (20). It will be interesting whether mutations of these basic residues to alanine on IL-7 for GAG interactions, which are outside the binding interface to IL-7Rα, alter the binding kinetics with IL-7Rα (especially k1 rates).

Binding reaction pathways and heat capacity changes of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions

The interactions between IL-7 and nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα involve more complex binding kinetics than previous cytokine-receptor interactions. The binding kinetics of IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions fit best to a two-step binding reaction model where an encounter complex is observed (Fig. 2). Other cytokine-receptor interactions, especially in the γc family members (IL-2, IL-4, IL-15, and IL-21), fit best to a single-step reaction model with single kon and koff rate constants (reviewed in (34, 35)). These cytokine-receptor interactions may experience encounter complexes, but are transient in nature and not observable during the experimental assays. Furthermore, extensive scanning mutagenesis studies of protein-ligand interactions show the absence of electrostatic enhancement in the systems described above where k1 on-rates do not change dramatically (less than 10-fold changes) (17, 35). The changes in overall binding affinities (Kd = koff/kon) of various protein-protein interactions are primarily driven through changes in off-rates (17, 35).

The IL-7 interactions with nonglycosylated and glycosylated forms of IL-7Rα deviate from these observed trends in protein-protein interactions and also from the behavior of γc family members. Of note, these trends above have been studied for nonglycosylated protein-protein interactions or where glycosylation has been determined not to be crucial to binding affinity. The 300-fold enhanced binding affinity of IL-7 to glycosylated IL-7Rα over nonglycosylated IL-7Rα results from a four order of magnitude faster k1 rate change at 150 mM NaCl and 298 K with minor changes in the other three rate-constants (k−1, k2, and k−2). The IL-7 association mechanism changes as a function of IL-7Rα glycosylation. Specifically, the changes in the k1 on-rates switch from a "conformational" search mechanism for the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction (k1 102 M−1s−1) to a "diffusion" controlled search mechanism for the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction (k1 106 M−1s−1) (17). The k1 rate of the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα complex is approximately an order of magnitude faster than the rotational and translational diffusion limit of 105 M−1s−1 for two proteins (17). To my knowledge, the changes in k1 on-rates as a function of IL-7Rα glycosylation are the largest reported differences for a protein-protein interaction that utilizes glycosylation for association. Previous binding studies of human granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (hGM-CSF) to its receptor reported an 46-fold slower k1 on-rate between nonglycosylated and glycosylated hGM-CSF (36). This resulted in a Kd to the hGM-CSF receptor that was weakened by 25-fold for glycosylated hGM-CSF versus the nonglycosylated form (820 vs. 33 pM at 4 °C) (36). In another example, EPO binding to EPOR displayed an 19-fold reduction in the k1 on-rates of nonglycosylated versus glycosylated EPO to EPOR (22). For both hGM-CSF and EPO, glycosylation weakens the binding affinities by slowing down the k1 on-rates to their receptors. An opposite role of glycosylation occurs in the IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction, where IL-7Rα glycosylation enhances binding affinity to IL-7 by dramatically accelerating the k1 association.

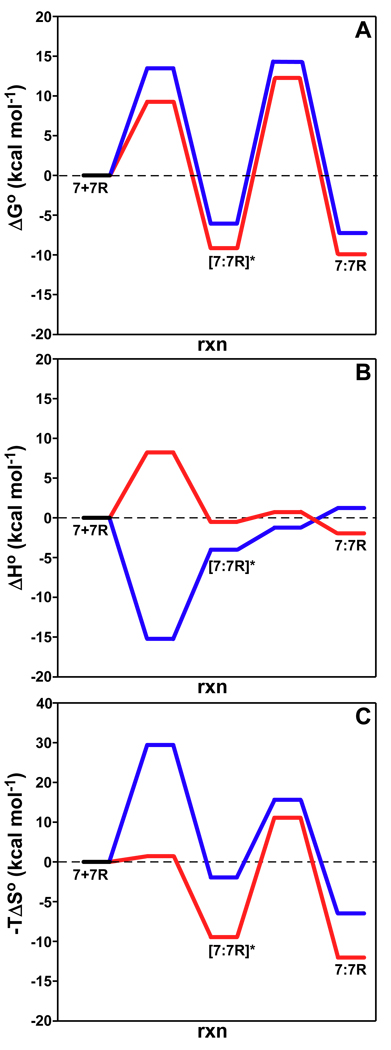

To probe further into the binding mechanisms of IL-7 interacting to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα, transition-state binding thermodynamics were investigated through analysis of the temperature dependence of the SPR binding kinetics. Determination of the absolute transition-state thermodynamic values from Eyring analysis of SPR biosensor kinetic data has come under considerable scrutiny (37, 38). Here, I highlight the relative transition-state binding thermodynamics for the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions since they show significant differences for the binding pathways of IL-7 to IL-7Rα with and without attached N-glycans. The reaction pathways of IL-7 binding to both forms of IL-7Rα as a function of ΔGo, ΔHo, and −TΔSo are displayed in Fig. 8. The rate-determining steps of ΔGo for both binding reactions occur in the second step moving from the transition and rearrangement of the encounter complexes to the final complex states at 298 K, 150 mM NaCl, and pH 7.4. The ΔGo changes of the reaction pathways are similar for the interactions of IL-7 to nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα except for the first step from the unbound states to the encounter complexes (ΔGo‡k1 of 13.5 vs. 9.04 kcal mol−1). This difference between the nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα interaction with IL-7 at the first transition-state is further propagated and not compensated for through the second transition-state. This accounts for the ΔΔGo of −3 kcal mol−1 (nonglycosylated – glycosylated) stabilization of the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα pathway over the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα pathway. The transition-state enthalpy and entropy changes further point to the first step of the two reaction pathways as responsible for the largest differences.

Figure 8.

Binding reaction pathways determined from Eyring analysis for IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions for ΔGo (A), ΔHo (B), and −TΔSo (C). The blue and red lines are for the nonglycosylated and glycosylated pathways, respectively. The transition-state thermodynamic values for the interactions are listed in Table 3.

Differing reaction pathways are observed in the breakdown of ΔGo changes for the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions into their transition-state enthalpies and entropies. Fig. 8B displays the ΔHo reaction pathways for both interactions. The ΔHo change from the unbound proteins to the encounter complex of the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (EC) interaction has a barrierless transition with a favorable ΔHo‡k1 of −15.1 kcal mol−1. On the other hand, the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) ΔHo binding change from the unbound proteins to the encounter complex encounters an enthalpic barrier (ΔHo‡k1 of 8.3 kcal mol−1) that is also the rate-determining step of the reaction coordinate. Moving from the encounter complexes to the final states, the ΔHo changes for both IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions display comparable energies (Table 3). The overall ΔHo changes, however, for both reactions are small and either have unfavorable or favorable energies for the nonglycosylated (0.31 kcal mol−1) and glycosylated (−0.079 kcal mol−1) reactions. The barrierless transition of ΔHo‡k1 for the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction is rather unique: other activation enthalpies of other protein-protein systems have values similar to the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction (reviewed in (21)).

With regard to entropy changes (−TΔSo), the rate-determining step for the IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interactions changes as a result of attached N-glycans to IL-7Rα. The rate-determining step for the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction is the first step going from the unbound proteins to the encounter complex (Fig. 8C). For the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction, there is a −TΔΔSo‡k1 (nonglycosylated - glycosylated) change of 27.9 kcal mol−1 lowering of the first step of the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα pathway. This changes the rate-determining step for the glycosylated reaction to the second step going from the encounter complex to the final bound state. The magnitudes of the −TΔSo‡ changes for both IL-7/IL-7Rα reactions for the second step have similar values (Table 3). As seen with the transition-state thermodynamics of ΔGo and ΔHo, the −TΔSo data also indicate the importance of the first step going from unbound proteins to the encounter complex for the differences between the interaction of IL-7 with the IL-7Rα forms, and specifically to the unbound IL-7Rα. The lowering of the −TΔSo energies from the nonglycosylated versus glycosylated pathway during the first step potentially results from the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα experiencing more conformational fluctuations than the glycosylated IL-7Rα. These conformational fluctuations of the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα may not allow for productive association with IL-7, whereas the glycosylated IL-7Rα may restrict its structural conformations to those more conducive to interact with IL-7. Previous studies have determined that glycosylation of proteins and peptides restrict ϕ,φ space for β-turn structures and that glycosylation stabilizes the native state (relative to the unfolded state) in the face of temperature and chemical denaturation (reviewed in (39)). This may offer an explanation for the differences in the k1 rate changes observed between IL-7 and the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα (EC) relative to the glycosylated IL-7Rα (CHO) binding to IL-7 (102 to 106 M−1s−1). The results reported here with the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions potentially indicate that the orientations of the two molecules are most important, rather than the specific side-chain interactions, as has been demonstrated for the interactions of growth hormone and prolactin receptors (40). Extensive alanine-scanning mutagenesis of the individual residues at the IL-7/IL-7Rα interface is underway to further answer this question.

Another unexpected finding of this study was the lack of heat capacity changes (ΔCp) for either the equilibrium or transition-states for the two IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions. The IL-7/IL-7Rα binding interface is predominately apolar in nature (47% apolar vs. 33% polar residues), and one may have predicted a priori a significant negative ΔCp from potential conformational changes of the two unbound proteins and/or desolvation of the two surfaces upon formation (41). Similarly, the hydrophobic transfer of solutes into water results from negative ΔCp changes (41). However, both van't Hoff and Eyring analysis of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions showed linear dependencies as a function of temperature (ΔCp = 0). Analysis of the IL-7/IL-7Rα structures (2 nonglycosylated and 1 glycosylated complex structure) indicate an average buried surface of 740 Å2 (7). Several research groups have parameterized the calculation of ΔCp from the changes in accessible surface areas for apolar and polar groups at binding interfaces (42–45). Using these methods, the calculated ΔCp values of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interface range from −238 to −413 cal mol−1 K−1 with an average of −303 cal mol−1 K−1. The changes in the accessible surface areas were calculated with NACCESS (46) using a 1.4 Å probe as described previously (47). A survey of experimentally determined ΔCp values reflects an average value −80 ± 48 cal mol−1 K−1 for protein-protein interactions (48). The curvature induced with a ΔCp of −303 cal mol−1K−1 fitting to the Gibbs-Helmoltz equation would not be distinguishable from the linear regression of the van't Hoff and Eyring analysis that was performed for the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions. Future experiments using ITC will be used to measure any ΔCp changes for the nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions.

Structural-mechanistic roles of IL-7Rα glycosylation

The interaction between IL-7 and its IL-7Rα involves a favorable electrostatic effect that is independent of IL-7Rα glycosylation. The favorable electrostatic attraction of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction is also not controlled by the type of N-glycan composition of the α-receptor, as was the case for EPO binding EPOR. In that case, removal of the negatively charged sialic acids of the three N-glycans of EPO reduced the kon by 3-fold to the EPOR relative to fully N-glycosylated EPO (22). Further, the electrostatic energy (−U/RT) increased from 8.3 for EPO with sialic acids to 12.6 for asialo-EPO (22). The N-glycans of EPO do not contact the first or second binding interfaces of the EPORs (EPO binds to copies of EPOR) (49). We have previously demonstrated that the binding kinetics and affinities were similar between IL-7 to IL-7Rα produced from Schneider S2 insect cells, which produces uncharged paucimannose N-glycans, and IL-7Rα from CHO cells, which produces complex N-glycans with sialic acids (7). A similar electrostatic is likely to be seen between IL-7 and glycosylated IL-7Rα from S2 insect cells as seen in this study for the IL-7/IL-7Rα (CHO) interaction.

The attachment of N- or O-glycans to proteins may affect structure, folding/unfolding kinetics, stability, and binding/functional properties. Experiments are currently the only way to determine the extent, if any, to which glycans affect binding. Within the cytokine-receptor field, N- or O-linked glycosylation of the cytokine and/or receptor typically does not alter the binding and functional (in vitro) properties of these interactions. This has been illustrated in extensive studies of the growth hormone and prolactin receptors and their hormone ligands (reviewed in (34)). The majority of cytokines and cytokine receptors are glycoproteins. Glycosylation is important to a few cytokines or receptors, but the effects vary in magnitude and nature. For example, N-linked glycosylation of IL-5Rα is absolutely crucial to its binding interactions with its ligands (50). In another example involving N-linked glycosylation of EPO, the binding affinity is weakened for the EPOR relative to the nonglycosylated EPO (22). However, even with lower binding affinity to the EPOR, glycosylated EPO displays better in vivo pharmacokinetics than the nonglycosylated counterpart (51).

Several general effects of glycosylation have emerged from studies of glycoproteins versus their nonglycosylated forms. Glycosylation of proteins generally increases solubility, stability of the native state, and reversibility in temperature and chemical denaturations (39, 52, 53). Structurally, glycosylation of proteins may form stabilizing hydrogen bonds with surface groups, shield or reinforce hydrophobic patches on the surface of proteins, and stabilize clusters of unfavorable charged residues also on protein surfaces. Glycosylated proteins can have "chaperone" properties that enhance the overall stability of glycoproteins relative to their nonglycosylated counterparts. The attached glycans could affect the protein folding/unfolding pathways without affecting biological functions, as seen with protein chaperones (39, 52, 53). Entropic stabilization may be manifested in glycoproteins by reducing the disorder of the unfolded states of glycoproteins relative to their nonglycosylated proteins (39, 52, 53). A thorough study of the single N-glycan of human CD2 showed that the core trisaccharide structure of ManGlcNAc2 stabilized the β-sandwich structure by 3.1 kcal mol−1 and accelerated the glycoprotein folding rate 4-fold over the nonglycosylated form (54).

The structure of the glycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα complex revealed that the N-glycans of the IL-7Rα do not participate directly in the binding surface formed with IL-7 and do not induce large conformational changes in comparison to the nonglycosylated IL-7/IL-7Rα complex structure (Fig. 1) (7). Given the biophysical data presented here, which continually point to the binding constant differences between nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα in the first step of the reaction pathway with IL-7, we (my research group and I) posit that structural and energetic changes induced by glycosylation of the unbound IL-7Rα are being translated into enhanced allosteric binding effects to the IL-7/IL-7Rα interaction. To provide some support for this hypothesis, Fig. 9 displays the far-UV CD spectra of unbound nonglycosylated (EC) and glycosylated (S2) IL-7Rα ECDs. Also displayed in Fig. 9 is the far-UV CD spectra of the growth hormone receptor (hGHR) ECD. Both the nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7Rα have peaks at 230 nm with positive ellipticity. This peak has been observed for other homology class I cytokine receptors defined by the "WSXWS" primary sequence motif in the second fibronectin type III domain (55–57). The hGHR ECD does not display the 230 nm peak presumably because it contains a "YGEFS" sequence for the "WSXWS" sequence motif (IL-7Rα has a "WSEWS" sequence). The glycosylated IL-7Rα (S2) has a minimum negative ellipticity peak at ~212 nm, which is characteristic of β-sheet secondary structure (25). The minimum negative ellipticity peak for the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα (EC) shifts from ~212 nm in the glycosylated IL-7Rα (S2) to ~206 nm, representing increased random coil (25). The hGHR ECD, which also consists of two FNIII domains, displays a minimum negative ellipticity peak at ~210 nm that is between the two IL-7Rα spectra. Clearly, the CD wavelength scans of nonglycosylated and glycosylated IL-7R do not overlay with each other. We hypothesize that unbound glycosylated IL-7Rα is more thermodynamically stable than the unbound nonglycosylated IL-7Rα, and this enhanced stability is translated indirectly to the tighter binding to IL-7 through entropic stabilization. A further complication arises with IL-7Rα in that there are six potential N-linked glycosylation sites on the receptor: N29, N45, N131, N162, N212, and N213. Further mutagenesis and biophysical studies of the N-glycan sites of IL-7Rα will show which N-glycan(s) is/are critical to the enhanced binding constants with IL-7. In addition, structures of the nonglycosylated and glycosylated forms of the unbound IL-7Rα will aid in deciphering the allosteric mechanism induced by N-linked glycosylation of the α-receptor.

Figure 9.

Circular dichroism spectra of unbound forms of IL-7Rαs (EC and S2) and the human growth hormone receptor (hGHR) ECDs. The spectra display the far-UV regions of the nonglycosylated IL-7Rα (EC, blue), glycosylated IL-7Rα (S2, red), and hGHR (green).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

STRW dedicates this manuscript to Dr. Jeff Urbauer and Mrs. Ramona Bieber Urbauer.

Funding information: This research was supported by grants from the AHA (535131N) and NIH (AI72142) to STRW.

Abbreviations and Textual Footnotes

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- IL-7

interleukin-7

- IL-7Rα

interleukin-7 alpha receptor

- ECD

extracellular domain

- CD

circular dichroism

- GlcNAc

N-acetylglucosamine

- MAN

mannose

- ΔGo

free energy change

- ΔHo

enthalpy change

- ΔSo

entropy change

- pI

isoelectric point

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Bar graphs of the k−1, k2, and k−2 rate constants versus increasing salt concentration is provided in Fig. S1. Individual rate constants of the IL-7/IL-7Rα interactions are listed in Tables S1 for nonglycosylated interaction and S2 for glycosylated interaction. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mazzucchelli R, Durum SK. Interleukin-7 receptor expression: intelligent design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:144–154. doi: 10.1038/nri2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rochman Y, Spolski R, Leonard WJ. New insights into the regulation of T cells by gamma(c) family cytokines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:480–490. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puel A, Ziegler SF, Buckley RH, Leonard WJ. Defective IL7R expression in T(−)B(+)NK(+) severe combined immunodeficiency. Nat Genet. 1998;20:394–397. doi: 10.1038/3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji RC. Lymphatic endothelial cells, lymphangiogenesis, and extracellular matrix. Lymphat Res Biol. 2006;4:83–100. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2006.4.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonard WJ. TSLP: finally in the limelight. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:605–607. doi: 10.1038/ni0702-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin RG, Lupton S, Schmierer A, Hjerrild KJ, Jerzy R, Clevenger W, Gillis S, Cosman D, Namen AE. Human interleukin 7: molecular cloning and growth factor activity on human and murine B-lineage cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:302–306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McElroy CA, Dohm JA, Walsh ST. Structural and biophysical studies of the human IL-7/IL-7Ralpha complex. Structure. 2009;17:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wickham J, Jr., Walsh STR. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction of human interleukin-7 bound to unglycosylated and glycosylated forms of its alpha receptor. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2007;F63:865–869. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107042807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh ST, Jevitts LM, Sylvester JE, Kossiakoff AA. Site2 binding energetics of the regulatory step of growth hormone-induced receptor homodimerization. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1960–1970. doi: 10.1110/ps.03133903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh ST, Sylvester JE, Kossiakoff AA. The high- and low-affinity receptor binding sites of growth hormone are allosterically coupled. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17078–17083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403336101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morton TA, Myszka DG, Chaiken IM. Interpreting complex binding kinetics from optical biosensors: a comparison of analysis by linearization, the integrated rate equation, and numerical integration. Anal Biochem. 1995;227:176–185. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myszka DG, Morton TA. Clamp: a biosensor kinetic data analysis program. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:149–150. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bevington PR, Robinson DK. Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences, Vol. 3rd edition. Burr Ridge, Il: McGraw Hill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Record MT, Jr., Anderson CF, Lohman TM. Thermodynamic analysis of ion effects on the binding and conformational equilibria of proteins and nucleic acids: the roles of ion association or release, screening, and ion effects on water activity. Q Rev Biophys. 1978;11:103–178. doi: 10.1017/s003358350000202x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen BJ, Hage T, Sebald W. Global and local determinants for the kinetics of interleukin-4/interleukin-4 receptor alpha chain interaction. A biosensor study employing recombinant interleukin-4-binding protein. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240:252–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0252h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis-Harrison RL, Armstrong KM, Baker BM. Two different T cell receptors use different thermodynamic strategies to recognize the same peptide/MHC ligand. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:533–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreiber G, Haran G, Zhou HX. Fundamental Aspects of Protein-Protein Association Kinetics. Chem Rev. 2009;109:839–860. doi: 10.1021/cr800373w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vijayakumar M, Wong KY, Schreiber G, Fersht AR, Szabo A, Zhou HX. Electrostatic enhancement of diffusion-controlled protein-protein association: comparison of theory and experiment on barnase and barstar. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:1015–1024. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selzer T, Schreiber G. Predicting the rate enhancement of protein complex formation from the electrostatic energy of interaction. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:409–419. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selzer T, Albeck S, Schreiber G. Rational design of faster associating and tighter binding protein complexes. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:537–541. doi: 10.1038/76744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schreiber G. Kinetic studies of protein-protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darling RJ, Kuchibhotla U, Glaesner W, Micanovic R, Witcher DR, Beals JM. Glycosylation of erythropoietin affects receptor binding kinetics: role of electrostatic interactions. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14524–14531. doi: 10.1021/bi0265022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker BM, Murphy KP. Evaluation of linked protonation effects in protein binding reactions using isothermal titration calorimetry. Biophys J. 1996;71:2049–2055. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eyring H. The activated complex and the absolute rate of chemical reactions. Chem. Rev. 1935;17:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fersht A. Stucture and mechanism in protein science. New York: W. H. Freemand and Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hage T, Sebald W, Reinemer P. Crystal structure of the interleukin-4/receptor alpha chain complex reveals a mosaic binding interface. Cell. 1999;97:271–281. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80736-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laporte SL, Juo ZS, Vaclavikova J, Colf LA, Qi X, Heller NM, Keegan AD, Garcia KC. Molecular and Structural Basis of Cytokine Receptor Pleiotropy in the Interleukin-4/13 System. Cell. 2008;132:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinemer P, Sebald W, Duschl A. The Interleukin-4-Receptor: From Recognition Mechanism to Pharmacological Target Structure. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2000;39:2834–2846. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000818)39:16<2834::aid-anie2834>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreiber G, Fersht AR. Rapid, electrostatically assisted association of proteins. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:427–431. doi: 10.1038/nsb0596-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piehler J, Schreiber G. Biophysical analysis of the interaction of human ifnar2 expressed in E. coli with IFNalpha2. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:57–67. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone SR, Dennis S, Hofsteenge J. Quantitative evaluation of the contribution of ionic interactions to the formation of the thrombin-hirudin complex. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6857–6863. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wendt H, Leder L, Harma H, Jelesarov I, Baici A, Bosshard HR. Very rapid, ionic strength-dependent association and folding of a heterodimeric leucine zipper. Biochemistry. 1997;36:204–213. doi: 10.1021/bi961672y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kossiakoff AA. The structural basis for biological signaling, regulation, and specificity in the growth hormone-prolactin system of hormones and receptors. Adv Protein Chem. 2004;68:147–169. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)68005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kossiakoff AA, Koide S. Understanding mechanisms governing protein-protein interactions from synthetic binding interfaces. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cebon J, Nicola N, Ward M, Gardner I, Dempsey P, Layton J, Duhrsen U, Burgess AW, Nice E, Morstyn G. Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor from human lymphocytes. The effect of glycosylation on receptor binding and biological activity. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4483–4491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winzor DJ, Jackson CM. Interpretation of the temperature dependence of rate constants in biosensor studies. Anal Biochem. 2005;337:289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winzor DJ, Jackson CM. Interpretation of the temperature dependence of equilibrium and rate constants. J Mol Recognit. 2006;19:389–407. doi: 10.1002/jmr.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitra N, Sinha S, Ramya TN, Surolia A. N-linked oligosaccharides as outfitters for glycoprotein folding, form and function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horn JR, Sosnick TR, Kossiakoff AA. Principal determinants leading to transition state formation of a protein-protein complex, orientation trumps side-chain interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2559–2564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809800106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chandler D. Interfaces and the driving force of hydrophobic assembly. Nature. 2005;437:640–647. doi: 10.1038/nature04162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy KP, Freire E. Thermodynamics of structural stability and cooperative folding behavior in proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 1992;43:313–361. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60556-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spolar RS, Record MT., Jr. Coupling of local folding to sitespecific binding of proteins to DNA. Science. 1994;263:777–784. doi: 10.1126/science.8303294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makhatadze GI, Privalov PL. Energetics of protein structure. Adv Protein Chem. 1995;47:307–425. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myers JK, Pace CN, Scholtz JM. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2138–2148. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hubbard S, Thornton J. NACCESS, computer program. University College London: Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker BM, Murphy KP. Prediction of binding energetics from structure using empirical parameterization. Methods Enzymol. 1998;295:294–315. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)95045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stites WE. Protein-protein interactions: interface structure, binding thermodynamics, and mutational analysis. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:1233–1250. doi: 10.1021/cr960387h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Syed RS, Reid SW, Li C, Cheetham JC, Aoki KH, Liu B, Zhan H, Osslund TD, Chirino AJ, Zhang J, Finer-Moore J, Elliott S, Sitney K, Katz BA, Matthews DJ, Wendoloski JJ, Egrie J, Stroud RM. Efficiency of signalling through cytokine receptors depends critically on receptor orientation. Nature. 1998;395:511–516. doi: 10.1038/26773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johanson K, Appelbaum E, Doyle M, Hensley P, Zhao B, Abdel-Meguid SS, Young P, Cook R, Carr S, Matico R, et al. Binding interactions of human interleukin 5 with its receptor alpha subunit. Large scale production, structural, and functional studies of Drosophila-expressed recombinant proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9459–9471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Egrie JC, Browne JK. Development and characterization of novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein (NESP) British journal of cancer. 2001;84 Suppl 1:3–10. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dwek RA. Glycobiology: Toward Understanding the Function of Sugars. Chem Rev. 1996;96:683–720. doi: 10.1021/cr940283b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wyss DF, Wagner G. The structural role of sugars in glycoproteins. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1996;7:409–416. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanson SR, Culyba EK, Hsu TL, Wong CH, Kelly JW, Powers ET. The core trisaccharide of an N-linked glycoprotein intrinsically accelerates folding and enhances stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3131–3136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810318105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anaguchi H, Hiraoka O, Yamasaki K, Naito S, Ota Y. Ligand binding characteristics of the carboxyl-terminal domain of the cytokine receptor homologous region of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27845–27851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ozbek S, Grotzinger J, Krebs B, Fischer M, Wollmer A, Jostock T, Mullberg J, Rose-John S. The membrane proximal cytokine receptor domain of the human interleukin-6 receptor is sufficient for ligand binding but not for gp130 association. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21374–21379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hensley P, Doyle ML, Myszka DG, Woody RW, Brigham-Burke MR, Erickson-Miller CL, Griffin CA, Jones CS, McNulty DE, O'Brien SP, Amegadzie BY, MacKenzie L, Ryan MD, Young PR. Evaluating energetics of erythropoietin ligand binding to homodimerized receptor extracellular domains. Methods Enzymol. 2000;323:177–207. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)23367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeLano W. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roos H, Karlsson R, Nilshans H, Persson A. Thermodynamic analysis of protein interactions with biosensor technology. J Mol Recognit. 1998;11:204–210. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1352(199812)11:1/6<204::AID-JMR424>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.