Abstract

This study analyzed the change of breast density in women receiving tamoxifen treatment using 3-D MRI. Sixteen women were studied. Each woman received breast MRI before and after tamoxifen. The breast and the fibroglandular tissue were segmented using a computer-assisted algorithm, based on T1-weighted images. The fibroglandular tissue volume (FV) and breast volume (BV) were measured and the ratio was calculated as the percent breast density (%BD). The changes in breast volume (ΔBV), fibroglandular tissue volume (ΔFV), and percent density (Δ%BD) between two MRI studies were analyzed and correlated with treatment duration and baseline breast density. The ΔFV showed a reduction in all 16 women. The Δ%BD showed a mean reduction of 5.8%. The reduction of FV was significantly correlated with baseline FV (P<0.001) and treatment duration (P=0.03). The percentage change in FV was correlated with duration (P=0.049). The reduction in %BD was positively correlated with baseline %BD (p=0.02). Women with higher baseline %BD showed more reduction of %BD. 3D MRI may be useful for the measurement of the small changes of ΔFV and Δ%BD after tamoxifen. These changes can potentially be used to correlate with the future reduction of cancer risk.

Keywords: breast density, tamoxifen, 3D MRI, breast, fibroglandular tissue, percent breast density

INTRODUCTION

Mammographic density (MD) is a function of abundance of epithelial and connective tissue in the breast. MD has been proven as an independent risk factor for breast cancer [1–5]. Most of the current knowledge about breast density has been obtained using mammography. The relationship between MD and breast cancer risk is well established. Women with extensive dense breast tissue visible on a mammogram have a cancer risk 1.8 to 6.0 times that of women with low density [5]. Boyd et al. found a 2% increase in relative breast cancer risk for every 1% increase in percent mammographic density (PMD) [6]. With the relationship established by the epidemiology evidence [1–5], research effort has been devoted to incorporate breast density into risk assessment models [7–10]. It was found that a risk model based on breast density alone adjusted for age and ethnicity was as accurate as the Gail model [9], and a new model that can estimate 5-year risk for invasive breast cancer has also been developed [10].

For women who had been diagnosed with breast cancer, their cancer risk in the contralateral breast is increased [11–13], with the cumulative incidence of 15.4% at 20 years [11]. The risk among women diagnosed at younger age (< 50 years old) had a cumulative probability of nearly 40% after 15 years [14]. Adjuvant hormonal therapy is commonly used for preventing secondary cancer in patients with hormonal positive breast cancer. Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) to prevent estrogen from binding to the receptor, and is the most commonly used adjuvant hormonal therapy for hormone receptor-positive breast cancers. It has been demonstrated to reduce the incidence of contra-lateral breast cancers in breast cancer patients and to prevent the cancer risk by as much as 50% in healthy women [15, 16]. Tamoxifen and other estrogen receptor modulators, such as raloxifene, have also been shown to decrease breast density particularly in pre-menopausal woman [17–21]. The underlying mechanism is not well known yet, but reducing the proliferative activity of breast tissues seems to be one major reason [22–24].

A few studies assessing the change of breast density after adjuvant hormonal therapy using mammography have been reported. Most studies found consistent reduction of breast density in premenopausal women, either taking tamoxifen as a preventive measure against or as part of their treatment for breast cancer [19–21]. The evaluation of breast density based on mammogram bears some major problems, including tissue-overlapping, positioning difference of the woman, variation of the degree of compression, as well as the calibration of mammography units and the setting of kVp and mAs used to acquire the mammogram [25]. MRI provides a 3-dimensional view of the breast with strong soft tissue contrast distinguishing between fibroglandular and fatty tissues. As such, MRI does not suffer from the problems in mammography that come from the projection nature, hence may be advantageous for evaluating the change in breast density after receiving adjuvant hormonal therapy. The goal of this study was to use an MR-based method to measure the change of breast density following tamoxifen treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Subjects

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our Institution and was HIPAA-compliant. All patients gave written informed consent for participating in the MRI study. The enrollment criteria were patients who had completed cancer treatment and received tamoxifen as adjuvant hormonal therapy, and who had a pre-treatment and one post-treatment MRI studies done at the breast center. In a period of two and a half years (October 2006 to March 2009), 17 women were identified. All subjects had histologically confirmed, hormonal positive breast cancer, and were prescribed to take tamoxifen (20 mg oral tablet per day) for 5 years. One subject was excluded due to incomplete coverage of the whole breast in the baseline MRI study. The remaining 16 women (age 33–51, mean 43) were analyzed in this study. None of these 16 subjects had received any form of chemotherapy prior to or during the tamoxifen treatment period. Of the 16 subjects, 12 received unilateral mastectomy and 4 received breast conserving surgery prior to the tamoxifen treatment. In this study only the contralateral normal breast without any surgical intervention was analyzed.

The follow-up MRI was performed for surveillance purposes, and the duration between pre-treatment and follow-up studies ranged from 8 months to 26 months (17.5 ± 5.7 months). Three subjects had the treatment less than one year (8–11 months). Eleven were in between one to two years; and two were more than two years (25 and 26 months).

MRI Study Protocol

All MRI studies were acquired with a 1.5T MR scanner (Signa Excite HD, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with a dedicated 8-channel breast coil. The axial view T1-weighted images without fat suppression were used for the analysis of breast density in this study. The data were collected before the contrast injection. The parameters were: TR/TE/TI = 7.4/3.3/23 (ms), slice thickness = 2.0 mm, image matrix = 512 × 512 with pixel resolution 0.625 mm, FOV = 30cm. Depending on the size of breasts, some adjustments in TR, TE, and FOV were made. The number of slices varied according to the size of the breast, around 56 slices. The total imaging time for this imaging sequence was approximately 3 minutes.

Methods for Breast Segmentation and Breast Density Measurement

The analysis procedures include segmentation of breast from the body, and the segmentation between fibroglandular and fatty tissues within the breast. Firstly, the number of MRI slices (along the superior-inferior direction) containing the breast was defined. The first superior slice and the last inferior slice were determined when a layer of fatty breast tissue could be identified compared to the layer of body fat. Non-breast subcutaneous fat on the chest typically displays homogenous thickness across the chest wall. The selection had to ensure that no portion of the breast was excluded. Next, the lateral posterior margin of bilateral breasts was defined. The middle slice of the image sequence containing the most breast tissues was selected, and a horizontal line was drawn through the dorsal boundary of the sternum, resulting in a horizontally-cut image. The horizontal line defined on this image was then applied to all other slices.

The quantification of breast density was performed using a 3D MRI-based method [26]. Briefly, on the horizontally-cut image, a fuzzy c-means (FCM) based segmentation algorithm with the b-spline curve fitting was applied to obtain the breast boundary, and then the dynamic searching algorithm was applied to exclude the skin along the breast boundary. After the breast was segmented from the body, the total breast volume (BV) was calculated.

For fibroglandular tissue segmentation, the adaptive FCM was applied for bias field correction to remove image intensity non-uniformities, and for segmentation of the fibroglandular tissue from the surrounding fatty tissue. After completing the segmentation from all imaging slices, the volume of fibroglandular tissue (FV) was calculated, and the percent breast density (%BD) was obtained by normalizing FV to the BV.

The analysis of breast density in the follow-up MRI study of each patient was done by using her own pre-treatment MRI as reference. The number of slices containing the breast was fixed, also the number of clusters used for fibroglandular tissue segmentation was the same. This was to ensure that the analysis was performed using a matching setting, in order to minimize any variation that may come from the operator.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). For normality test, the distribution of each parameter was first tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Age, follow-up duration, BV at B/L (BV_B/L), BV at F/U (BV_F/U), %BD at B/L (%BD_B/L), %BD at F/U (%BD_F/U) were already normally distributed. No further transformations were needed for these four parameters. Square-root transformation was applied to FV at B/L (FV_B/L) and FV at F/U (FV_F/U) to ensure normal distribution for further statistical comparison. The stepwise linear regression was utilized to investigate the relationship between the changes in (sqrt) FV with baseline BV, baseline (sqrt) FV, age and treatment duration. The change in %BD was analyzed in the same way to investigate the association with baseline BV, baseline %BD, age and treatment duration. A P value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

The results measured in the baseline and the follow-up studies are summarized in Table 1. The baseline BV ranged from 69 to 688 cm3 (358±174 cm3). The follow-up BV ranged from 73 to 633 cm3 (331±157 cm3). The baseline FV ranged from 19 to 272 cm3 and the follow-up FV ranged from 9 to 175 cm3. The baseline %BD ranged from 5.1% to 39.5 % (22.1±2.6%). The follow-up %BD ranged from 2.6% to 30.8% (16.3±3.3%). The absolute reduction of %BD (Δ%BD) was 5.8%±3.8% compared to the baseline MRI. Seven subjects showed Δ%BD less than 5%; 7 were between 5–10%; and 2 showed larger than 10%. Overall, the group mean of BV, FV, and %BD between the baseline and the follow-up MRI all show significant reduction (Table 1).

Table 1.

The mean value and range of breast volume, fibroglandular tissue volume and the percent breast density in pre-treatment (B/L) and follow-up MRI studies

| B/L Range (median) Mean±STD |

F/U Range (median) Mean±STD |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Volume (cm3) | 69 – 688 (366) 358±174 |

73 – 633 (327) 331±157 |

P=0.01 |

| Fibro Volume (cm3) | 19 – 272 (53) 79±66 |

9 – 175 (45) 52±41 |

P<0.001 |

| Breast Density (%) | 5.1 – 39.5 (23.6) % 22.1±2.6 (%) |

2.6 – 30.8 (16.3) % 16.3±3.3 (%) |

P<0.001 |

The range (median) of each raw data set is shown. The beast volume and the percent density are normally distributed, and the mean ± standard deviation is also shown. The fibroglandular volume is not normally distributed, and the square root transformation is applied before performing the t-test.

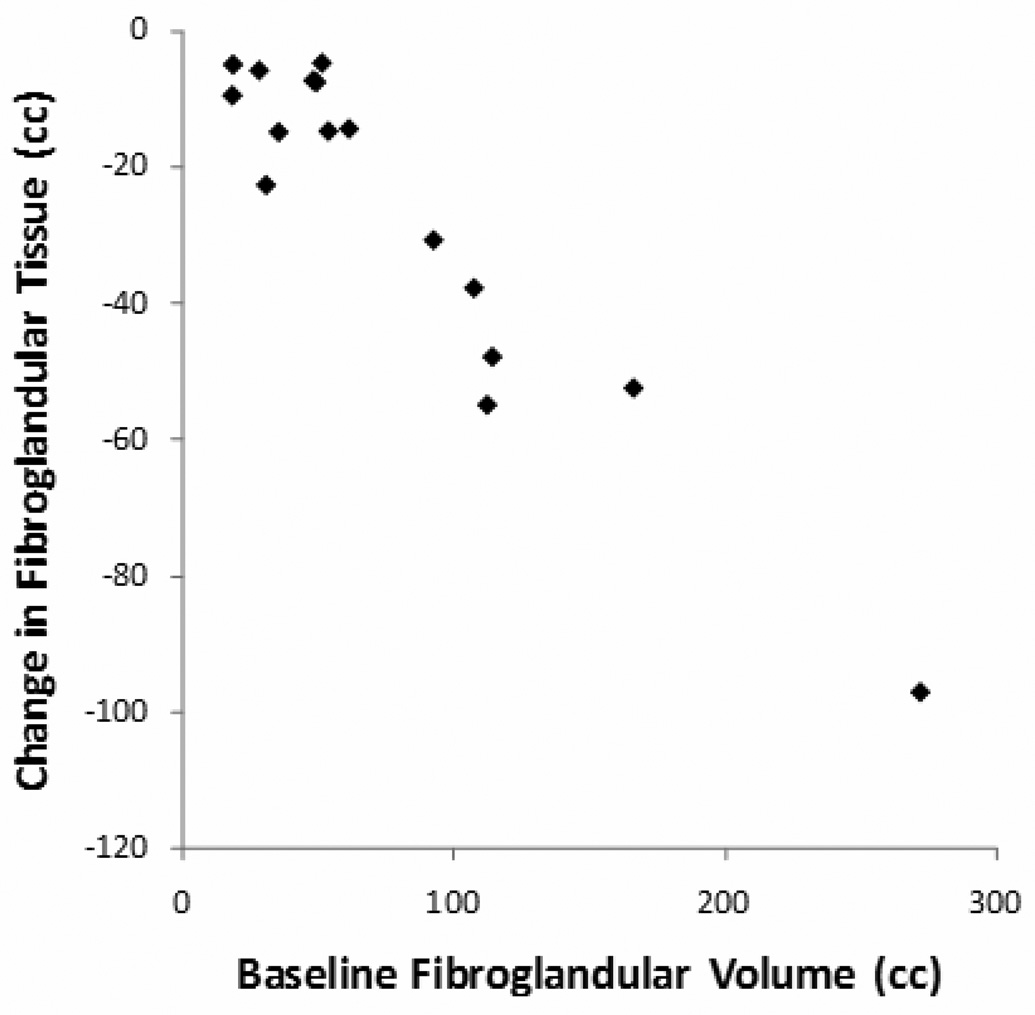

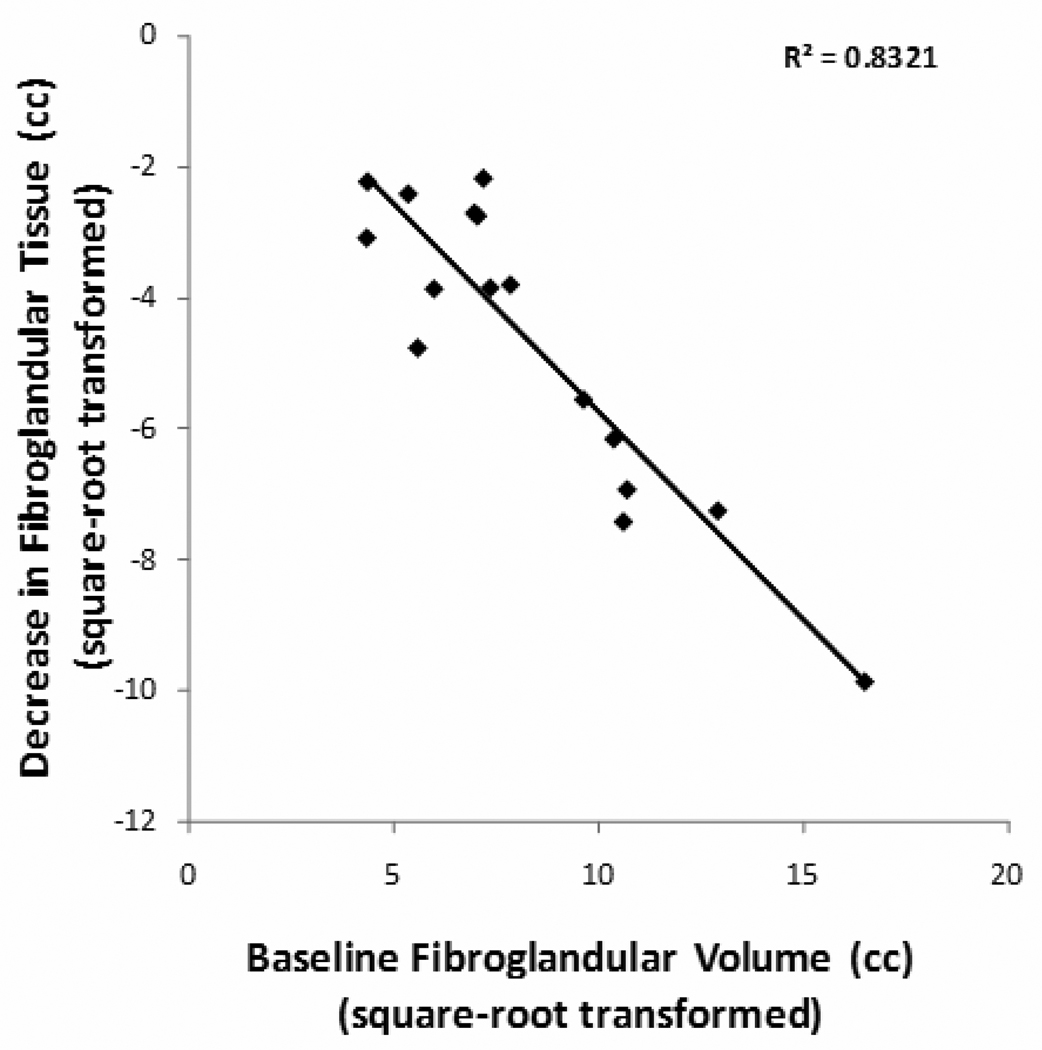

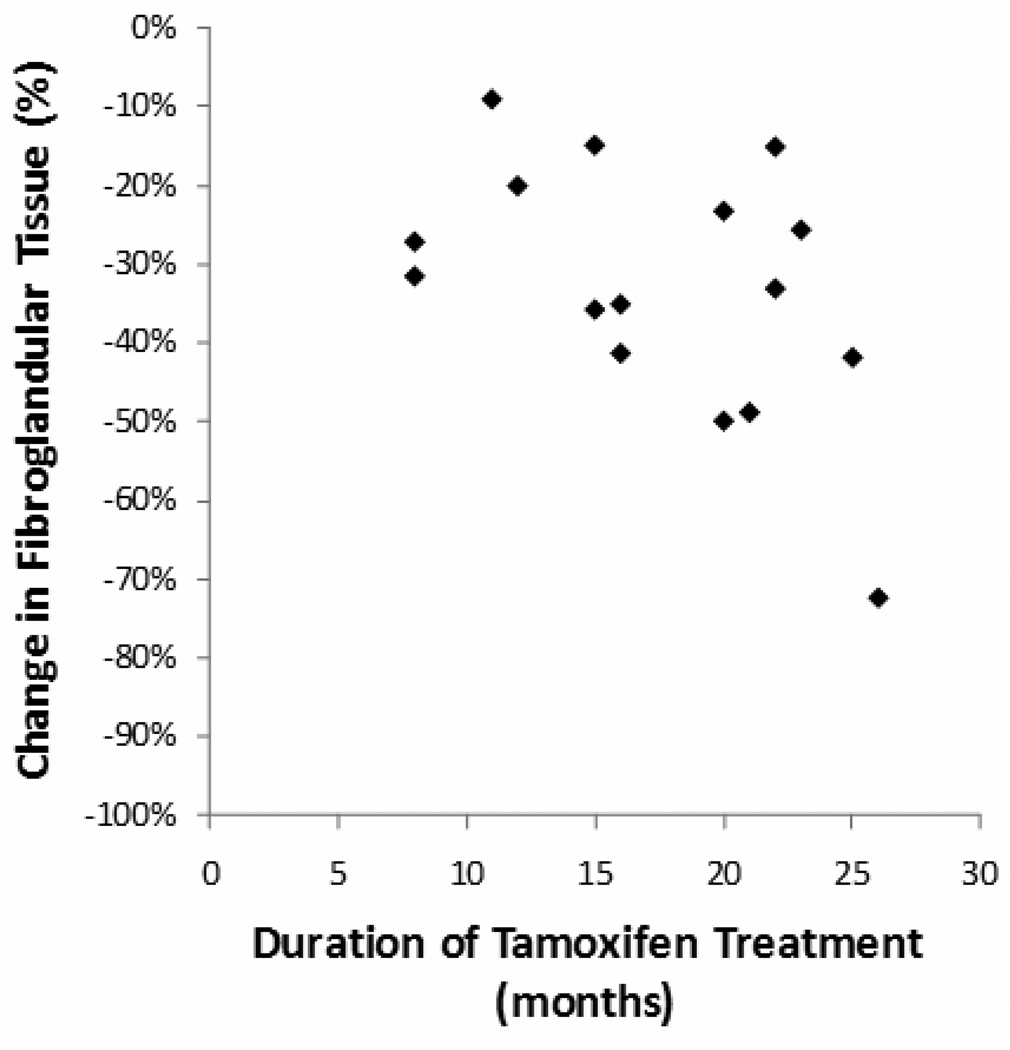

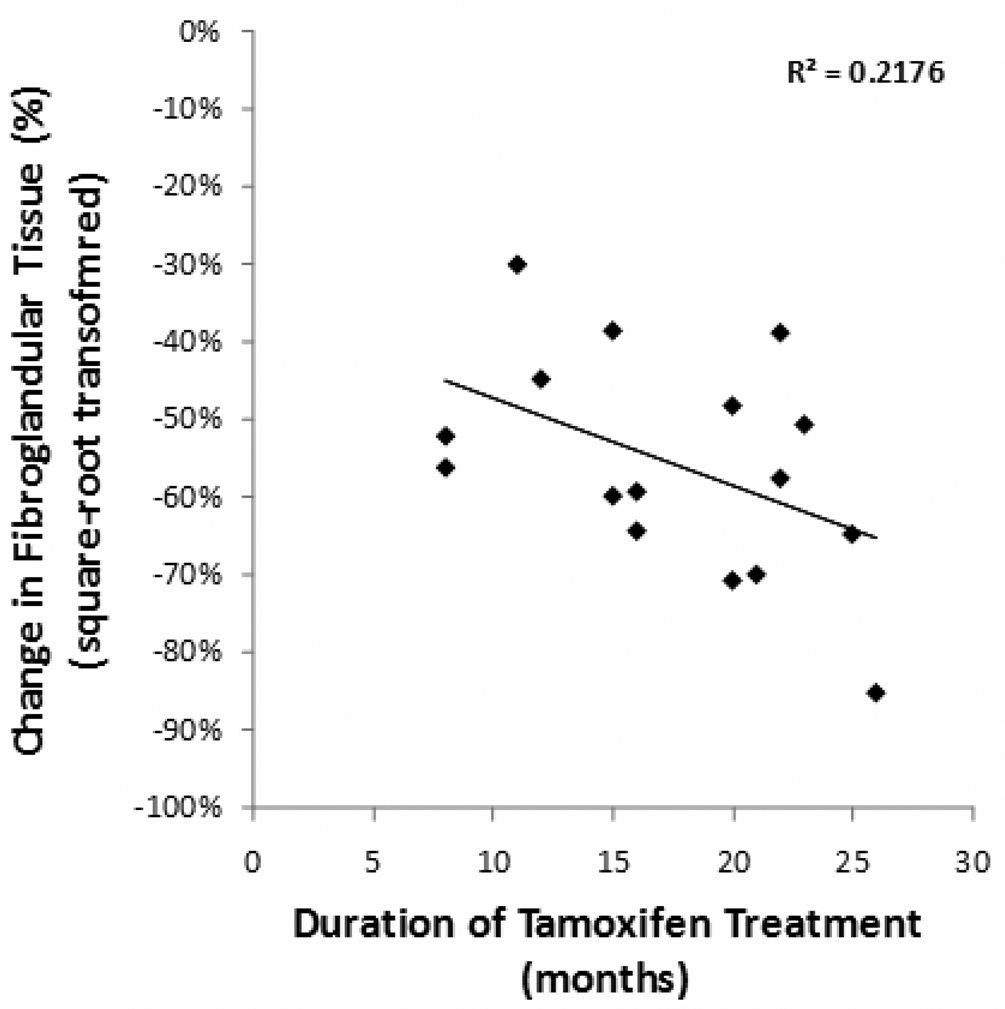

The change of BV, FV, and %BD between the baseline and the follow-up MRI for each patient was calculated, and the results are summarized in Table 2. The stepwise linear regression was used to check the relationship between the changes in (sqrt) FV with baseline BV, baseline (sqrt) FV, age and the follow-up duration. The results showed that the reduction of FV and (sqrt) FV was correlated with baseline FV (P<0.001) (Figure 1) and the duration of tamoxifen treatment (P=0.03). Patients with a higher baseline density showed a greater reduction. When normalized to the baseline FV, the %ΔFV reduction ranged from 9.0% to 72.0%. This percentage change in (sqrt) FV was significantly correlated with the duration of treatment (P=0.049) (Figure 2). Patients receiving a longer tamoxifen treatment had a greater FV reduction. The Δ%BD was also correlated with baseline %BD (p=0.02). A case example is illustrated in Figure 3. The results suggest that tamoxifen treatment causes significant reduction in breast density, and that the reduction is positively correlated with the baseline density and the treatment duration.

Table 2.

The changes in breast volume, fibroglandular tissue volume and the percent breast density between the baseline and the follow-up MRI of each patient.

| Range (median) | Mean±STD 95% CI |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BV(B/L)-BV(F/U) cm3 | −17.8–94.6 (25.6) | 26.7 ± 35.5 [7.7–45.6] |

P=0.01 |

| FV(B/L)-FV(F/U) cm3 | 4.7–97.0 (14.7) | 26.6 ± 24.8 [13.0–40.3] |

P<0.001 |

| BD(B/L)-BD(F/U) % | 0.3–11.9 (5.5) | 5.8 ± 3.8 (%) [3.7–7.8] |

P<0.001 |

Figure 1.

Figure 1A and 1B. The reduction of FV and square-root transformed FV was positively correlated with baseline FV and baseline square-root transformed FV, respectively.

Figure 2.

Figure 2A and 2B. The percentage reduction in FV and square-root transformed FV was significantly correlated with the duration of treatment.

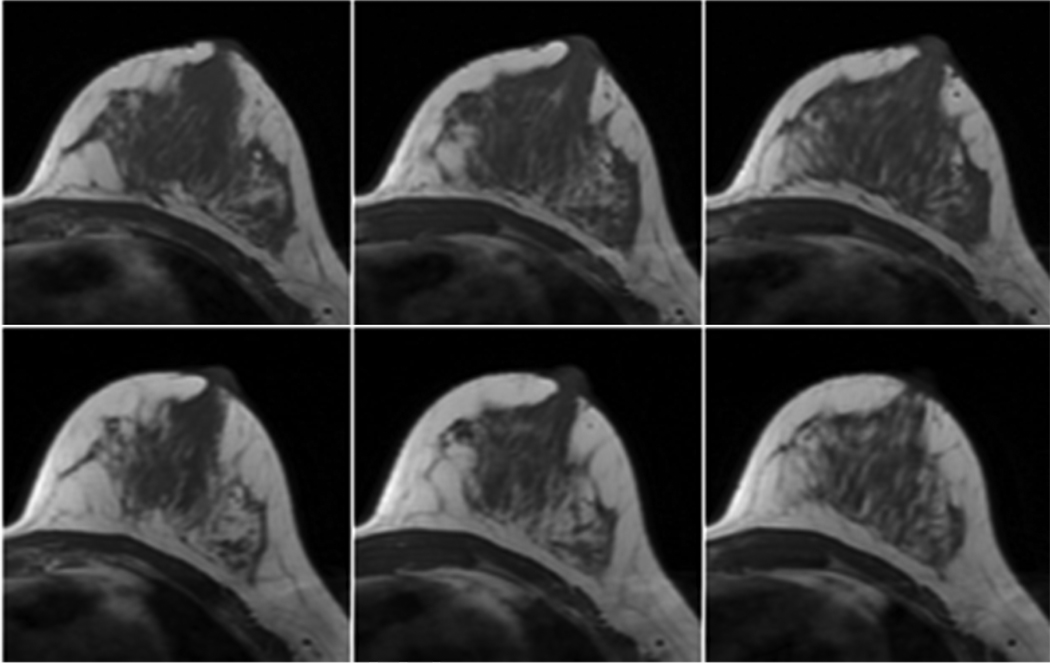

Figure 3.

A 38 year-old woman with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer in the right breast had received breast conserving surgery prior to her tamoxifen treatment. The upper row was the baseline MR images of the left breast before the treatment. The lower row was the MR images 25 months after the treatment. The baseline fibroglandular tissue volume was 114.4ml and the follow-up was 66.6ml, with a reduction of 47.8ml (41.8%). The reduction of percent breast density was 8.4%.

DISCUSSION

Although MD is an independent risk factor for breast cancer, the link between the change of breast density and the modified risk is less known [3, 27–30]. It was found that an increase in BIRADS density category within 3 years is associated with an increase in breast cancer risk; and a decrease in density is associated with a decreased risk [29]. Tamoxifen is known to reduce breast cancer risk. However, it was not clear that whether the reduced breast density can be used as a surrogate marker to predict the protective effect. Recently the missing link was elucidated by a study by Cuzick et al. reporting the density results analyzed from the International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS-1) trial in 2008 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. This trial enrolled 7154 high-risk women and randomized them to receive tamoxifen or placebo for 5 years. It was shown that women who had at least a 10% reduction in MD over the first 12 to 18 months of tamoxifen prophylaxis had a 63% reduction in breast cancer risk (P=0.002); whereas other women who had < 10% reduction in MD had no benefit from tamoxifen treatment (P=0.89). It was noted that most of the density reduction occurred during the first 18 months of treatment. The impact of tamoxifen on risk reduction thus seems to be predictable by changes in MD during the first 18 months of treatment [31]. In our study, the average treatment duration of tamoxifen was 17.5 months.

Despite of all the encouraging results reporting the role of MD, breast density can also be measured by other imaging modalities. Especially when the change of density measured from the same woman over time will be measured, the consistency of the imaging technique should be a main concern. A recent review article by Kopans raised question about the accuracy of breast density determined by mammography [32]. The author stressed that studies suggesting a link between MD and risk for breast cancer have methodological flaws, and concluded that studies showing small percentage differences between groups are likely to be inaccurate.

Measurement of breast density using MRI has been reported by several groups [18, 33–39]. Different from MD, the MRI provides full 3D coverage of the breast, and using appropriate segmentation procedures, the breast volume and the fibroglandular tissue volume can be measured. Several studies have compared the density measured by MRI and mammography. A recent study from 138 high-risk women by Khazen et al. has shown a significant correlation between MD and the density calculated from MRI (r = 0.78) [33]. Another study of 35 patients by Klifa [39] et al. also showed similar findings. The study reporting measurement of changes in breast density using MRI was scarce. A recent article by Eng-Wong et al. found that in women receiving raloxifene, the MD did not show change, but the fibroglandular tissue volume measured by MRI showed significant reduction. Based on the findings, they suggested that MR breast density is more sensitive for detecting small changes, thus it may provide a promising surrogate biomarker and should be investigated further in breast cancer prevention trials [18]. Our study also showed decreased fibroglandular tissue volume ΔFV after tamoxifen treatment. The mean Δ%BD was 5.8% after 17-month follow-up in our study.

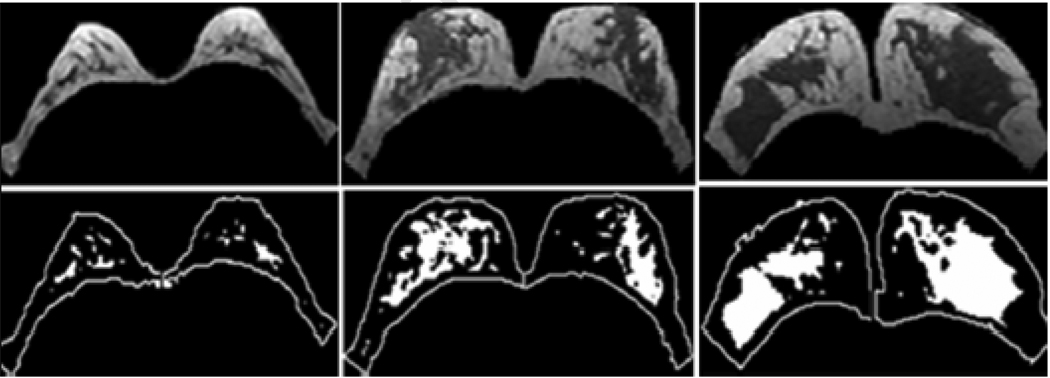

The 3D MR-based method used in this study [26] has small measurement errors. The average standard deviation for breast volume and percent density measurements was in the range of 3%–4% among three trials of one operator or among three different operators. When tested for different breast morphologies, including fatty breast, the method still showed small variation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Intra-operator variations on the measurement of the percent density in 3 different breast morphologies. The percent density variation is 2.2% for a 49 y/o Caucasian woman with fatty breast (left), 1.3% for a 49 y/o Asian with intermingled fat and fibroglandular tissue (middle), and 3.7% for a 33 y/o Asian with dense breast (right).

Many studies have reported reduction in MD after tamoxifen treatment. Cuzick et al. [17] investigated MD in asymptomatic high-risk women receiving tamoxifen for chemoprevention. They showed a greater density reduction in the tamoxifen group (7.9%) than in the placebo group (3.5%) within 18 months of treatment (P<.001). Meggiorini et al. studied 148 women and found a statistically significant difference in density reduction between the tamoxifen and the non-tamoxifen treated group after one year of treatment [40]. Similarly, Chow et al. studied 28 high risk women taking tamoxifen for two years, and found that digitized MD scores showed 4.3% decrease per year (P = 0.0007) [41]. In a study of women under age of 50, Brisson et al. reported that the mean Δ%BD was −12.1%±11% for the treatment group, and was −3.6%±4.5% for the control group (p< 0.01) [19]. Another study performed by Son et al. [21] evaluated the effects of 20mg/day tamoxifen in 102 patients and 50 control patients, and showed that 60% of tamoxifen-treated women demonstrated a marked decrease in breast density on mammography as compared to 36% of control patients.

Our study also showed that the change in fibroglandular tissue volume (ΔFV) was correlated with the baseline FV and the duration of treatment, with women showing higher ΔFV when their baseline FV was higher or duration of treatment was longer. Brisson et al. [19] studied 36 women and found the tamoxifen-associated reduction in breast density was apparent after 1.0 –3.4 years of treatment (6.9±11.1%). With 3.5–5 years of treatment, the density was further reduced to 10.9±12.4%. Similarly, Cuzick et al [17] found the breast density further reduced from 7.8% after 18 months to 13.7% after 54 months of treatment. The reason why women with higher baseline FV showed a greater ΔFV was not clear. Since MD may reflect cumulative estrogen effect on the breast tissue, it was anticipated that tamoxifen might work more effective on women with denser breast. There was also a significant correlation between baseline %BD and the reduction of %ΔBD. For measurement of breast density over time, either using mammography or MRI, a consistent breast segmentation is crucial in order to calculate the %BD accurately. This is usually difficult in longitudinal follow-up studies due to variation in patient’s positioning that might lead to different coverage in mammography. Whether a higher reduction of FV or %BD will correlate with a lower cancer risk in the future warrants further investigation.

In our study, the 16 patients showed different degree of density reduction with seven subjects showed Δ%BD less than 5%; 7 were between 5–10%; and 2 showed larger than 10%. The difference of density reduction might be accounted by the fact that breast response following tamoxifen may vary due to variation of liver enzyme necessary to metabolize tamoxifen into an active form [42].

In our study, none of the 16 subjects had received chemotherapy prior to or during their tamoxifen treatment period. Many studies have found the association of breast density with ovarian function. Various chemotherapy agents, especially the alkylating category, have been associated with premature ovarian failure [43–45]. Through this effect, the breast density may be reduced.

Besides density reduction, decrease of enhancement of the fibroglandular tissue has also been reported following treatment with selective estrogen receptor modulators [46, 47]. In a study of 10 peri- or postmenopausal patients who received a short-term tamoxifen medication, 6 patients showed a significant decrease of enhancement [46]. However, in a study to analyze the influence of breast density on background enhancement at MRI in pre- and postmenopausal women [48], no correlation was found.

Tamoxifen and other estrogen receptor modulators can also affect body fat distribution [49, 50]. In a study of 50 postmenopausal women, after 1 yr, subjects receiving raloxifene had a slight reduction of fat mass in trunk and central region and an increase in legs and, in relation to the control group, with significantly lower values of adiposity in trunk and abdominal region [49]. Tamoxifen was found to induce fatty liver. Increased hepatic steatosis was detected in 15 of 34 (44%) patients after 3 months of tamoxifen therapy [50]. In our study, the slight reduction of breast volume (Table 1 and Table 2) following the tamoxifen treatment might be accounted by its effect on the body fat distribution.

In this study, we did not have a control group. It would be interesting to compare such variations with variations measured between baseline and follow-up in the tamoxifen-treated subjects. Once we know what the %change is in normal volunteers (repositioning in the MRI device), then we can conclude that %change measured in the treated population is due to treatment effect. Our density methodology paper [26], however, has shown that the body position dependence, performed in two volunteers at five different positions, had small variation in the range of 3%–4%.

Other limitations existing in our study included: 1) The study was based on retrospective review with small number of patients. 2) The duration for the F/U MRI after the tamoxifen treatment was not consistent. 3) Body mass index (BMI) was not considered. However, all subjects did not showed obvious body weight change during their treatment period.

In conclusion, our preliminary data based on 3D MR method showed a significant reduction in FV and %BD after tamoxifen treatment, and the density reduction was positively correlated with the baseline density. Since breast density is affected by many variables, it is difficult to estimate a woman’s risk based on the measure of density at one time point. When the baseline density of a woman is known to serve as her own control, a reliable method, such as 3D MRI, may be used to measure changes over time. For a patient receiving adjuvant hormonal therapy, such a method may be very helpful to evaluate her own benefit in terms of reducing breast density, thus cancer risk.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported in part by NIH/NCI R03 CA136071 and California BCRP 14GB-0148.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jan 18;356(3):227–236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Jun;15(6):1159–1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vachon CM, Pankratz VS, Scott CG, et al. Longitudinal trends in mammographic percent density and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007 May;16(5):921–928. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaffe MJ, Boyd NF, Byng JW, et al. Breast cancer risk and measured mammographic density. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1998 Feb;7 Suppl 1:S47–S55. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199802001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd NF, Dite GS, Stone J, et al. Heritability of mammographic density, a risk factor for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002 Sep 19;347(12):886–894. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd NF, Byng JW, Jong RA, Fishell EK, Little LE, Miller AB, Lockwood GA, Tritchler DL, Yaffe MJ. Quantitative classification of mammographic densities and breast cancer risk: results from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:670–675. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.9.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Pee D, Ayyagari R, et al. Projecting absolute invasive breast cancer risk in white women with a model that includes mammographic density. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 Sep 6;98(17):1215–1226. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santen RJ, Boyd NF, Chlebowski RT, et al. Critical assessment of new risk factors for breast cancer: considerations for development of an improved risk prediction model. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007 Jun;14(2):169–187. doi: 10.1677/ERC-06-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Ziv E, Kerlikowske K. Mammographic breast density and the Gail model for breast cancer risk prediction in a screening population. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005 Nov;94(2):115–122. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-5152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Kerlikowske K. Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Mar 4;148(5):337–347. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill-Kayser CE, Harris EE, Hwang WT, Solin LJ. Twenty-year incidence and patterns of contralateral breast cancer after breast conservation treatment with radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006 Dec 1;66(5):1313–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tilanus-Linthorst MM, Alves C, Seynaeve C, Menke-Pluymers MB, Eggermont AM, Brekelmans CT. Contralateral recurrence and prognostic factors in familial non-BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2006 Aug;93(8):961–968. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji J, Hemminki K. Risk for contralateral breast cancers in a population covered by mammography: effects of family history, age at diagnosis and histology. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007 Oct;105(2):229–236. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9445-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahedi K, Emanuelsson M, Wiklund F, Gronberg H. High risk of contralateral breast carcinoma in women with hereditary/familial non-BRCA1/BRCA2 breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2006 Mar 15;106(6):1237–1242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bao T, Prowell T, Stearns V. Chemoprevention of breast cancer: tamoxifen, raloxifene, and beyond. Am J Ther. 2006 Jul–Aug;13(4):337–348. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200607000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponzone R, Biglia N, Jacomuzzi ME, Mariani L, Dominguez A, Sismondi P. Antihormones in prevention and treatment of breast cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006 Nov;1089:143–158. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuzick J, Warwick J, Pinney E, Warren RM, Duffy SW. Tamoxifen and breast density in women at increased risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004 Apr 21;96(8):621–628. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eng-Wong J, Orzano-Birgani J, Chow CK, et al. Effect of Raloxifene on mammographic density and breast magnetic resonance imaging in premenopausal women at increased risk for breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Jul;17(7):1696–1701. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brisson J, Brisson B, Cote G, et al. Tamoxifen and mammographic densities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Pre. 2000;9:911–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkinson C, Warren R, Bingham SA, Day NE. Mammographic patterns as a predictive biomarker of breast cancer risk: effect of tamoxifen. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:863–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Son HJ, Oh KK. Significance of follow-up mammography in estimating the effect of tamoxifen in breast cancer patients who have undergone surgery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:905–909. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.4.10511146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Souza Sales JF, Jr, Cabello C, Alvarenga M, Torresan RZ, Duarte GM. Nonproliferative epithelial alteration and expression of estrogen receptor and Ki67 in the contralateral breast of women treated with tamoxifen for breast cancer. Breast. 2007 Apr;16(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernardes JR, Jr, Nonogaki S, Seixas MT, et al. Effect of a half dose of tamoxifen on proliferative activity in normal breast tissue. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999 Oct;67(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(99)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.da Silva BB, Lopes IM, Gebrim LH. Effects of raloxifene on normal breast tissue from premenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006 Jan;95(2):99–103. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harvey JA, Bovbjerg VE. Quantitative Assessment of Mammographic Breast Density: Relationship with Breast Cancer Risk. Radiology. 2004;230:29–41. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2301020870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nie K, Chen JH, Chan S, Chau MK, Yu HJ, Bahri S, Tseng T, Nalcioglu O, Su MY. Development of a Quantitative Method for Analysis of Breast Density Based on 3-Dimensional Breast MRI. Medical Physics. 2008;35(12):5253–5262. doi: 10.1118/1.3002306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habel LA, Dignam JJ, Land SR, Salane M, Capra AM, Julian TB. Mammographic density and breast cancer after ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004 Oct 6;96(19):1467–1472. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maskarinec G, Pagano I, Lurie G, Kolonel LN. A longitudinal investigation of mammographic density: the multiethnic cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Apr;15(4):732–739. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerlikowske K, Ichikawa L, Miglioretti DL, et al. Longitudinal measurement of clinical mammographic breast density to improve estimation of breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007 Mar 7;99(5):386–395. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guthrie JR, Milne RL, Hopper JL, Cawson J, Dennerstein L, Burger HG. Mammographic densities during the menopausal transition: a longitudinal study of Australian-born women. Menopause. 2007 Mar–Apr;14(2):208–215. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000232278.82218.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuzick J, Warwick J, Pinney L, et al. Change in breast density as a biomarker of breast cancer risk reduction; results from IBIS-I; presented at the annual meeting of San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; 2008. Abstract 61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kopans DB. Basic physics and doubts about relationship between mammographically determined tissue density and breast cancer risk. Radiology. 2008;246(2):348–353. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461070309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khazen M, Warren R, Boggis C, et al. A pilot study of compositional analysis of the breast and estimation of breast mammographic density using three-dimensional T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(9):2268–2274. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei J, Chan HP, Helvie MA, et al. Correlation between mammographic density and volumetric fibroglandular tissue estimated on breast MR images. Med. Phys. 2004 Apr;31(4):923–942. doi: 10.1118/1.1668512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Engeland S, Snoeren PR, Huisman H, Boetes C, Karssemeijer N. Volumetric breast density estimation from full-field digital mammograms. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006 Mar;25(3):273–282. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.862741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee NA, Rusinek H, Weinreb J, et al. Fatty and fibroglandular tissue volumes in the breasts of women 20–83 years old: comparison of X-ray mammography and computer-assisted MR imaging. AJR. 1997;168:501–506. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.2.9016235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao J, Zujewski JA, Orzano J, Prindiville S, Chow C. Classification and calculation of breast fibroglandular tissue volume on SPGR fat suppressed MRI. Med Imag Proc SPIE. 2005:1942–1949. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klifa C, Carballido-Gamio J, Wilmes L, et al. Quantification of breast tissue index from MR data using fuzzy cluster. Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soci. 2004;3:1667–1670. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2004.1403503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klifa C, Carballido-Gamio J, Wilmes L, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for secondary assessment of breast density in a high-risk cohort. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009 Jul 22; doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.05.040. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meggiorini ML, Labi L, Vestri AR, Porfiri LM, Savelli S, De Felice C. Tamoxifen in women with breast cancer and mammographic density. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;29(6):598–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chow CK, Venzon D, Jones EC, et al. Effect of tamoxifen on mammographic density. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000 Sep;9(9):917–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Briest S, Stearns V. Tamoxifen metabolism and its effect on endocrine treatment of breast cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2009;7(3):185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oktem O, Oktay K. Quantitative assessment of the impact of chemotherapy on ovarian follicle reserve and stromal function. Cancer. 2007;110(10):2222–2229. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gadducci A, Cosio S, Genazzani AR. Ovarian function and childbearing issues in breast cancer survivors. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007;23(11):625–631. doi: 10.1080/09513590701582406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swain SM, Land SR, Ritter MW, et al. Amenorrhea in premenopausal women on the doxorubicinand- cyclophosphamide-followed-by-docetaxel arm of NSABP B-30 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:315–320. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9937-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heinig A, Lampe D, Kölbl H, Beck R, Heywang-Köbrunner SH. Suppression of unspecific enhancement on breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) by antiestrogen medication. Tumori. 2002 May–Jun;88(3):215–223. doi: 10.1177/030089160208800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oksa S, Parkkola R, Luukkaala T, Mäenpää J. Breast magnetic resonance imaging findings in women treated with toremifene for premenstrual mastalgia. Acta Radiol. 2009 Nov;50(9):984–989. doi: 10.3109/02841850903168083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cubuk R, Tasali N, Narin B, Keskiner F, Celik L, Guney S. Correlation between breast density in mammography and background enhancement in MR mammography. Radiol Med. 2010 Jan 15; doi: 10.1007/s11547-010-0513-4. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Francucci CM, Daniele P, Iori N, Camilletti A, Massi F, Boscaro M. Effects of raloxifene on body fat distribution and lipid profile in healthy post-menopausal women. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005 Jul–Aug;28(7):623–631. doi: 10.1007/BF03347261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen MC, Stewart RB, Banerji MA, Gordon DH, Kral JG. Relationships between tamoxifen use, liver fat and body fat distribution in women with breast cancer. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001 Feb;25(2):296–298. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]