Abstract

Background

3-(2,4-Dimethoxybenzylidene)-anabaseine (DMXB-A) is a partial agonist at α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that has been evaluated clinically for treatment of schizophrenia. The current study examined the effects of DMXB-A on default network activity as a biomarker for drug effects on pathological brain function associated with schizophrenia.

Methods

Placebo and two doses of DMXB-A were administered in a random, double-blind crossover design during a one-month Phase-2 study of DMXB-A. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was performed on 16 non-smoking patients with schizophrenia while they performed a simple eye movement task. Independent component analysis was used to identify the default network component. Default network changes were evaluated in the context of a polymorphism in CHRNA7, the α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit gene, which was previously found to be associated with schizophrenia.

Results

Compared to placebo, both 150 mg and 75 mg b.i.d. DMXB-A altered default network activity, including a reduction in posterior cingulate, inferior parietal cortex and medial frontal gyrus activity, and an increase in precuneus activity. The most robust difference, posterior cingulate activity reduction, was affected by CHRNA7 genotype.

Conclusion

The observed DMXB-A-related changes are consistent with improved default network function in schizophrenia. Pharmacogenetic analysis indicates mediation of the effect through the α7-nicotinic receptor. These results further implicate nicotinic cholinergic dysfunction in the disease and suggest that default network activity may be a useful indicator of biologic effects of novel therapeutic agents.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, functional magnetic resonance imaging, default network, nicotinic receptors, CHRNA7

Introduction

The limited efficacy of currently available treatments for schizophrenia has spurred recent interest in therapeutic compounds that extend beyond traditionally studied dopaminergic mechanisms. 3-(2,4-Dimethoxybenzylidene)-anabaseine (DMXB-A) is a partial agonist at α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Its potential value in the treatment of schizophrenia was based on studies of the expression, genetics and function of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in patients with schizophrenia, as well as their high cigarette smoking rates (1–5).

In healthy subjects, DMXB-A has been shown to improve attention, working memory and episodic memory (6). A proof-of-concept Phase-1 trial of DMXB-A in schizophrenia found that the drug improved neurpsychological measures and an EEG measure of neuronal inhibitory function in patients (7). A subsequent initial phase-2 trial found that DMXB-A was not associated with changes in cognitive measures over the treatment arms, but was associated with a significant improvement in clinical ratings of negative symptoms, and a trend towards improvement in ratings of positive symptoms (8). During the double-blind, crossover phase-2 two trial, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data also were obtained. A preliminary report on the effects of DMXB-A on hippocampal function during a smooth pursuit eye movement task described reduced activity associated with the drug, consistent with improved inhibitory function (9).

The present study expands on the initial task-related fMRI findings, examining the neuronal effects of DMXB-A on default network activity, a broader measure of brain function. The “default network” or “default mode network” is a functionally connected network of brain regions that include the posterior cingulate cortex, cuneus/precuneus, medial prefrontal cortex, medial temporal lobe and inferior parietal cortices (10). Activity in the default network is thought to reflect a baseline state of brain function, in which subjects are not focused on the external environment, but rather are focused on their internal mental state, which may include various forms of spontaneous cognition, self-reflective thought or attention to internal stimuli (10). Although first widely reported as network of brain regions that “disengages” or “deactivates” when people engage in goal-directed tasks, the default network now has been robustly detected both during the resting state and across a variety cognitive tasks. The synchronous response of brain regions in the network commonly is identified by seed-based or independent component analysis methods (11).

Default network activity has been studied and found to be significantly altered in patients with schizophrenia, relative to healthy comparison subjects (12). One of the most consistently reported alterations is greater posterior default network activity or connectivity in patients, relative to healthy comparison subjects (12–18). Because of its involvement in internal mentation, it has been postulated that over-activity in the network may play a role in the misattribution of thought, and the altered boundary between internal and external perceptions observed in schizophrenia (10).

Differences in such a broad measure of brain function, combined with the measure’s reproducibility and relative ease of detection, suggest that default network activity may be a useful metric of neuronal response in the context of therapeutic development. The present study examined the effects of DMXB-A on default network activity in patients with schizophrenia. We tested the hypothesis that compared to placebo, DMXB-A would decrease posterior default network activity in schizophrenia. We also tested the hypothesis that genetic variations in the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene CHRNA7 would impact drug effects on the default network.

Methods

Patients

Patients who met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia received 1 month each of placebo, DMXB-A at a 75 mg dose and a 150 mg dose in randomized, double-blind cross over trial detailed below. Patients were simultaneously treated with their own neuroleptic drug to prevent relapse of psychosis during the trial and because the antidopaminergic activity was considered to be a distinctly different therapeutic mechanism. Only non-smoking patients were studied to prevent possible interference of the effects of DMXB-A by nicotine. Other exclusion and inclusion criteria are detailed in a previous report, which also presents the clinical and neurocognitive outcomes and safety data (8). The trial was approved by the institutional review board and conducted under FDA IND 57,710. Primary neurocognitive and clinical outcomes were specified in the clinical trials registry (NCT00100165). Patients gave their informed consent.

Twenty patients agreed to participate in the fMRI study. Of the 20 patients, two were excluded due to excess movement (> 1.5 mm) during fMRI scans. One subject did not complete all scanning sessions and data from one subject was not useable due to technical problems. Data were analyzed from 16 patients, including seven women (average age of 50.7 years, SD 8.54) and 9 men (average age of 42.3 years, SD 8.96). Nine patients were treated with atypical neuroleptics, two with typicals, and four with clozapine. One subject was unmedicated.

Experimental Drug Protocol

DMXB-A was synthesized and placed into capsules as previously described (8). Identical-appearing placebo capsules also were prepared. After 1 week of screening, patients received 1 week of placebo to assess compliance. Patients were then assigned to 4 weeks of twice-daily placebo, 75 mg b.i.d. of DMXB-A, or 150 mg b.i.d. of DMXB-A. Both patients and investigators, except for the pharmacist and biostatistician, were blind to drug identity. All patients received each treatment in a balanced crossover design. The three treatment arms were separated by 1-week washout periods, during which the patients received placebo. Compliance with medication as judged by capsule counts exceeded 90%. The fMRI session detailed below, along with clinical and neurocognitive assessments, was repeated at the end of each 4-week treatment arm, immediately after the morning dose of drug. Clinical measures included the BPRS (19) and SANS (20). Neurocognitive measures also were evaluated and have been reported previously (8).

On the morning of the fMRI scan, patients came to the imaging center prior to their first dose of drug. They were administered the drug by an investigator, and waited 30 minutes before being scanned so that functional imaging could be performed 45 to 90 minutes post-administration, near the predicted peak of plasma levels . The actual average time to fMRI was 60.1 +/− 4 minutes. All subjects were scanned within 8 minutes of this time frame. Physiological measures, including pulse rate and blood pressure also were obtained for safety and to confirm that the fMRI measure was unrelated to generalized vascular changes.

Plasma Drug Level Assays

Plasma specimens for drug level assays were obtained 2.25 to 2.50 hours after the first morning dose on the 4th week of each treatment arm (approximately 20 minutes after scanning on days when scanning and drug level assays occurred on the same study day). The specimens were analyzed for DMXB-A by high-performance liquid chromatography as previously described (7, 21, 22). The 4-hydroxy metabolite of DMXB-A also was detected in the samples, but was generally below the level of reliable quantification.

MRI Methods

Prior to functional imaging, a high-resolution, T1-weighted 3D anatomical scan was acquired for each subject. Functional images were acquired with a gradient-echo T2* echo-planar blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) contrast technique, with TR=2000ms, TE=30ms, FOV=220mm2, 642 matrix, 30 slices, 4 mm thick, no gap, angled parallel to the planum sphenoidale using a quadrature head coil. Voxel size was 3.4 × 3.4 × 4 mm3. Additionally, one IR-EPI (TI=505ms) volume was acquired to improve coregistration between the echo planar images and gray matter templates used in preprocessing.

Head motion was minimized with a VacFix head-conforming vacuum cushion (Par Scientific A/S, Odense, Denmark). MR-compatible goggles (Resonance Technology, Inc, CA, USA) were used for visual stimuli.

fMRI Paradigm

fMRI data were acquired as patients performed a simple smooth pursuit eye movement task described previously (9). Briefly, the task consisted of visually tracking a small white dot that moved horizontally back and forth over a visual angle of 26° at a constant velocity of 16.7° per second followed by a 700-ms fixation period at the edges. Patients were asked to “follow the dot, wherever it goes.” During ‘rest,’ patients were asked to “look straight ahead” at a black screen. The paradigm used a block design with three 30 s cycles of task alternating with and rest, totaling 3 minutes. Data were acquired for 3 runs, 3 minutes each, for a total of 9 minutes. Ten additional seconds of task with scanning preceded each run as an equilibration period for the functional images. For the identification of the default network component (ICA analysis described below), data were collapsed across task and rest conditions and concatenated across the three runs to form one dataset per subject.

fMRI Data Analysis

The first four image volumes from each run were excluded for saturation effects. Data were analyzed using SPM5 (Wellcome Dept. of Imaging Neuroscience, London). Data from each subject were realigned to the first volume, normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute gray-matter template, using a gray-matter-segmented IR-EPI as an intermediate to improve registration, and smoothed with an 8 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel.

Group independent component analyses was conducted using the GIFT toolbox, (http://icatb.sourceforge.net) (23). Data were processed as three groups: placebo, 75 mg DMXB-A, and 150 mg DMXB-A. For each group, the dimensionality of the data from each subject was reduced using principle component analysis (PCA) and concatenated into an aggregate data set. Twenty independent sources were estimated with an independent component analysis (ICA) using the infomax algorithm (24). Individual subject ICA data sets were then back-reconstructed. The default network component was identified by selecting the component with the highest spatial correlation to a default network mask (12). The mask included the lateral posterior parietal cortex, precuneus, posterior cingulate cortex, frontal pole, and occipitotemporal junction, as defined anatomically from the WFU Pickatlas (http://www.fmri/wfubmc.edu). The anatomical mask was smoothed with an 8 mm FWHM kernel to match the functional data. For each group, only one component was significantly (p<0.05) correlated with the mask. Other components were not examined. Data were scaled to percent signal change from the mean to allow comparisons across subjects and conditions. Contrast maps of the default network component for each subject in each drug condition were evaluated on a voxel-wise basis with a second-level repeated-measures one-way ANOVA (levels: placebo, 75mg DMXB-A, 150mg DMXB-A) in SPM5. Planned comparisons (t-contrasts within the ANOVA) were used to evaluate the directionality of results. To ensure differences reflected only default network activity, results were masked with the main effect of drug (p< 0.05 uncorrected). The term “activity” as used in this manuscript reflects the amplitude of the default network signal identified by ICA and spatial template matching. For exploratory regression analyses between plasma drug levels, symptom ratings and imaging measures, responses were collapsed across drug doses.

Genetic Analysis

Genotyping was performed on an Applied Biosystems 3730 Gene Analyzer (Foster City CA). The rs3087454 A/C single nucleotide polyorphism (SNP) was chosen for analysis of possible pharmacogenetic enomic effects of the CHRNA7 locus because it has the most significant association with schizophrenia: P = 0.005, corrected for multiple comparisons, under an allelic model for Caucasians (25). The frequency of the minor allele C is 0.360. Genotypes were available for 16 subjects, all Caucasians. A 2 × 2 analysis of variance with repeated measures was used to assess genotype using an allelic model, DMXB-A and dose effects and their interaction (factor DRUG included: placebo – 75 mg DMXB-A, placebo – 150 mg DMXB-A, factor GENOTYPE included: C allele, no C allele). The imaging measure used for this analysis was the percent signal change from the local maximum of drug-related differences in posterior cingulate default network activity.

Results

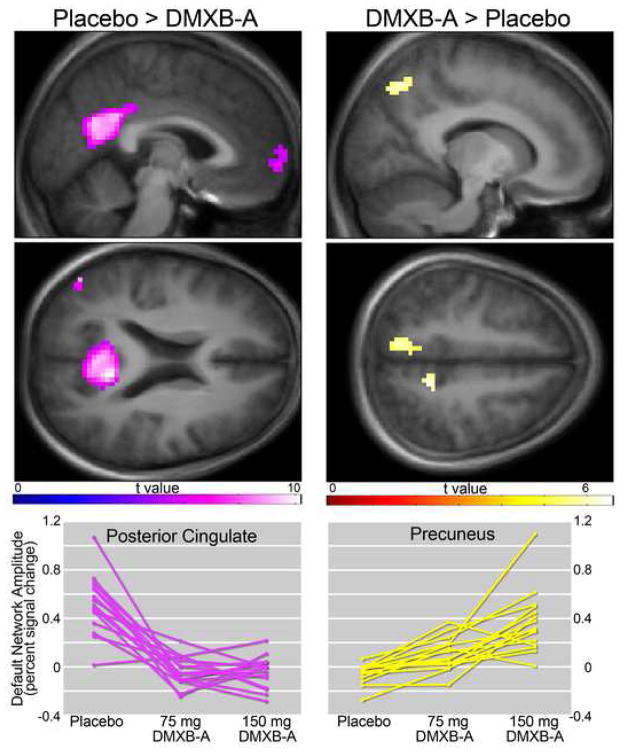

Compared to placebo, both 150 mg and 75 mg b.i.d. DMXB-A were associated with less default network activity in the posterior cingulate, inferior parietal cortex and medial frontal gyrus. The opposite response, greater default mode activity associated with drug, was observed in the precuneus. (Figure 1, Table 1). Neither dose effects, nor order effects were observed.

Figure 1.

Effects of DMXB-A on default network activity. Left panels indicate regions that showed reduced activity following administration of drug (collapsed across drug dose), compared to placebo administration. Right panels show areas of greater activity. Statistical maps thresholded at p < 0.05, FWE corrected. Data are shown in the radiological convention (R on L). Individual subject responses are shown in bottom panels.

Table 1.

| Placebo > DMXB-A* | coordinates | t value | spatial extent | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

| Posterior Cingulate (L) | −9 | −51 | 18 | 10.16 | 598 | <0.001 |

| Parietal Cortex (R) | 48 | −72 | 33 | 8.98 | 61 | <0.001 |

| Parietal Cortex (L) | −48 | −63 | 36 | 7.21 | 54 | <0.001 |

| Medial Frontal Gyrus | 0 | 63 | −3 | 6.72 | 58 | <0.001 |

| DMXB-A* > Placebo | ||||||

| Precuneus (R) | 15 | −69 | 48 | 6.27 | 50 | 0.001 |

| Precuneus (L) | −12 | −45 | 51 | 6.36 | 42 | 0.001 |

Coordinates in MNI space

All results are significant at p< 0.05, FWE corrected for multiple comparisons

DMXB-A values collapsed across doses

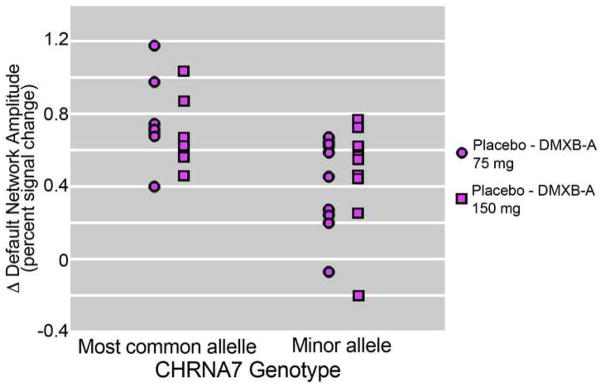

A two-way analysis of variance for the effect of the CHRNA7 rs3087454 SNP minor allele and dose of DMXB-A on the change in posterior cingulate default network activity, relative to placebo, showed a major effect of genotype (F = 6.45, df 1,14, p = 0.024) and no effect of dose. A trend was observed for an interaction between genotype and dose effects (F = 4.00, df 1, 14, p = 0.065). For DMXB-A 75 mg, default activity decreased by 0.77 (SD 0.25) for subjects who had the more common allele and 0.40 (SD 0.26) for subjects who had the minor allele associated with schizophrenia (t = 2.87, df 15, p = 0.012). For DMXB-A 150 mg, default network activity decreased by 0.70 (SD 0.19) for subjects who had the more common allele and 0.47 (SD 0.30) for subjects who had the minor allele associated with schizophrenia (t = 2.97, df 15, P = 0.094, ns). Figure 2 shows the effect of dose and genotype on default network activity.

Figure 2.

Effects of DMXB-A dose and CHRNA7 genotype (SNP rs3087454) on default network activity in 16 patients with schizophrenia. Most common allele indicates homozygosity for this genotype.

To examine the relationship between drug-related effects on the default network and task-associated effects, signal from the posterior cingulate and precuneus default network differences were regressed against the task-related decreases in the hippocampus reported previously (9). Significant correlations were not observed. Task-related hippocampal differences were, however, related to CHRNA7 genotype. As with default network differences, subjects who had the more common allele showed significantly greater task-related hippocampal response reductions, compared to subjects with the minor allele (t=2.14, p = 0.023).

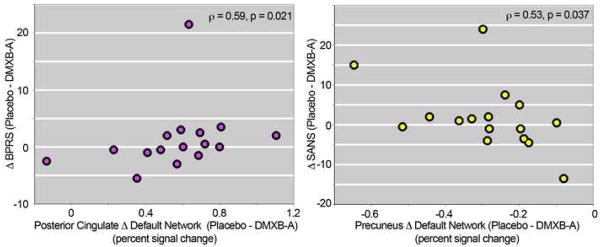

Decreases in posterior cingulate default network activity were positively correlated with decreases in total BPRS score (spearman correlation = 0.59, t=2.7, p = 0.021). Increases in precuneus default network activity were significantly correlated with decreases in SANS total score (spearman correlation = −0.53, t=2.4, p = 0.037) (Figure 3) A trend towards an inverse correlation was observed between DMXB-A plasma drug levels and posterior cingulate default network activity (r2 = 0.24, p = 0.055). These analyses are considered exploratory, however, and are not significant when corrected for multiple comparisons.. BPRS and SANS scores for the subjects who participated in the imaging study are listed in Table S1 (see Supplement). Detailed descriptions of the therapeutic effects on clinical ratings, neurocognitive measures and safety of DMXB-A have been reported previously (8).

Figure 3.

Relationship between difference in BPRS (left) and SANS (right) scores and difference in default network activity from placebo to DMXB-A (collapsed across dose).

Discussion

The primary finding of this study was that DMXB-A administration to patients with schizophrenia altered default network activity. Altered response was related to a polymorphism in the α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene CHRNA7.

The default network has been widely reported to be abnormal in schizophrenia (12). The majority of studies have identified greater posterior default network activity and connectivity in patients, relative to controls, across a wide variety of tasks (12–18). The most robust finding of the present study was reduced posterior cingulate activity in response to DMXB-A, consistent with more normal function of the network. This study also identified increased precuneus response. This pattern of decreased posterior cingulate and increased precuneus activity in response to drug suggests that its effect may be to partly normalize the two most significant pathological features in the network found by Garrity et al. in their relatively large study of default mode abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia compared to controls--greater posterior cingulate and less precuneus activity (12). Although the present results are consistent with improved default network function, the lack of a healthy comparison group and an unmedicated patient group in this study limits inferences about a putative normalization of network function.

Evidence was found for a pharmacogenetic effect of a SNP in the CHRNA7 gene on the effects of DMXB-A on default network activity. The minor allele was correlated with less improvement compared to placebo, particularly at the lower dose. Although the rs3087454 SNP, which occurs in the 5’ regulatory sequence of the CHRNA7 gene 1831 bp upstream of the translation start site, has no known function, it often occurs in conjunction with a set of rarer SNPs in the CHRNA7 core promoter that decrease its transcription and are also associated with schizophrenia (3, 25). These rare variants were not detected in the subjects in the current study, which suggests that rs3087454 may be in linkage disequilibrium with other variants in the gene as well.

Decreased expression of α7-nicotinic receptors is a pathological feature of schizophrenia (1). If the minor allele is associated with less expression of α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, then patients who have this variant may be less responsive to the agonist DMXB-A, particularly at lower doses. This possible explanation of the pharmacogenetic findings is consonant with the hypothesis that diminished expression of α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors leads to decreased endogenous nicotinic cholinergic neurotransmission in schizophrenia and the corollary that exogenous agonist stimulation of the receptors with drugs such as DMXB-A may be therapeutic.

A retrospective analysis of the effects of rs3087454 on the effects of DMXB-A on the change in neurocognitive performance in schizophrenia in an earlier single dose trial was performed (Olincy et al., 2006). The minor allele was associated with less change in performance of the Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Neuropsychological Status, compared to placebo, after DMXB-A 75 mg treatment (r = 0.65, P = 0.007), with a similar but non-significant finding after DMXB-A 150 mg (r = 0.50, P = 0.08). CHRNA7 SNP rs3087454 was also shown to influence differences between subjects with schizophrenia and controls in an independent components analysis of neuronal activity as assessed by fMRI in an auditory oddball task (26).

In conclusion, this preliminary study provides evidence that a broad and reliably detectable measure of brain function may be useful in assessing biological effects of novel therapeutic agents. Unlike our previous evaluation of task-specific hippocampal responses, which found drug effects only at the high drug dose, the current analysis of default network activity revealed drug effects at both low and high drug doses, suggesting this measure of neuronal function may provide high sensitivity to drug effects. Unlike our previous evaluation of task-specific hippocampal responses, which found drug effects only at the high drug dose, the current analysis of default network activity revealed drug effects at both low and high drug doses, suggesting this measure of neuronal function may provide high sensitivity to drug effects. In previous studies of neurocognitive effects in schizophrenia, larger effects were seen at low dose in the first clinical study (7) and at higher dose in the second study (8). However, significant differences between the two doses were not detected in either study. Lack of significant effect of dose may reflect the narrow range of doses employed. Finally, the effect of CHRNA7 genotype on the putative DMXB-A-related improvement in default network function observed in this study further supports the involvement of nicotinic cholinergic dysfunction in schizophrenia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the VA Biomedical Laboratory and Clinical Science Research and Development Service, by the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Centers of Veterans Integrated Service Networks 5 and 19, by NIMH grants MH-061412 and MH-086383, by the National Association for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders, by the Dana Foundation, and by NIDA grants DA-024104 and DA-027748, and the Institute for Children’s Mental Disorders. The authors would like to thank Dietmar Cordes, Ph.D. for critical comments during manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Listed in the clinical trials registry as: “Trial of DMXB-A in Schizophrenia,” NCT00100165, http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00100165

Disclosure: Drs. Leonard and Freedman have patents through the Department of Veterans Affairs on the CHRNA7 gene sequence. Drs. Kem and Soti have patents through the University of Florida on the manufacture and use of DMXB-A; Drs. Olincy and Johnson receive research support from Lundbeck. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Freedman R, Hall M, Adler LE, Leonard S. Evidence in postmortem brain tissue for decreased numbers of hippocampal nicotinic receptors in schizophrenia. BiolPsychiatry. 1995;38:22–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00252-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedman R, Coon H, Myles-Worsley M, Orr-Urtreger A, Olincy A, Davis A, et al. Linkage of a neurophysiological deficit in schizophrenia to a chromosome 15 locus. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 1997;94:587–592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leonard S, Gault J, Hopkins J, Logel J, Vianzon R, Short M, et al. Association of promoter variants in the alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit gene with an inhibitory deficit found in schizophrenia. ArchGenPsychiatry. 2002;59:1085–1096. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Mitchell JE, Dahlgren LA. Prevalence of smoking among psychiatric outpatients. AmJPsychiatry. 1986;143:993–997. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Leon J, Dadvand M, Canuso C, White AO, Stanilla JK, Simpson GM. Schizophrenia and smoking: an epidemiological survey in a state hospital. AmJPsychiatry. 1995;152:453–455. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitagawa H, Takenouchi T, Azuma R, Wesnes K, Kramer W, Clody D, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and effects on cognitive function of multiple doses of GTS-21 in healthy, male volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:542–551. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olincy A, Harris JG, Johnson LL, Pender V, Kongs S, Allensworth D, et al. Proof-of-concept trial of an {alpha} 7 nicotinic agonist in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:630. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman R, Olincy A, Buchanan RW, Harris JG, Gold JM, Johnson L, et al. Initial phase 2 trial of a nicotinic agonist in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1040–1047. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07071135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tregellas J, Olincy A, Johnson L, Tanabe J, Shatti S, Martin L, et al. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Effects of a Nicotinic Agonist in Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;35:938–942. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckner R, Andrews-Hanna J, Schacter D. The Brainís Default Network. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broyd S, Demanuele C, Debener S, Helps S, James C, Sonuga-Barke E. Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: A systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33:279–296. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrity AG, Pearlson GD, McKiernan K, Lloyd D, Kiehl KA, Calhoun VD. Aberrant “default mode” functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:450–457. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Y, Liang M, Tian L, Wang K, Hao Y, Liu H, et al. Functional disintegration in paranoid schizophrenia using resting-state fMRI. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;97:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison B, Y¸cel M, Pujol J, Pantelis C. Task-induced deactivation of midline cortical regions in schizophrenia assessed with fMRI. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;91:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sui J, Adali T, Pearlson G, Calhoun V. An ICA-based method for the identification of optimal FMRI features and components using combined group-discriminative techniques. Neuroimage. 2009;46:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim D, Manoach D, Mathalon D, Turner J, Mannell M, Brown G, et al. Dysregulation of working memory and default-mode networks in schizophrenia using independent component analysis, an fBIRN and MCIC study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009 doi: 10.1002/hbm.20807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Thermenos H, Milanovic S, Tsuang M, Faraone S, McCarley R, et al. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:1279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809141106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannell M, Franco A, Calhoun V, CaÒive J, Thoma R, Mayer A. Resting state and task-induced deactivation: A methodological comparison in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Human Brain Mapping. 2009 doi: 10.1002/hbm.20876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreasen NC. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Definition and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39:784. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahnir V, Lin B, Prokai-Tatrai K, Kem WR. Pharmacokinetics and urinary excretion of DMXBA (GTS-21), a compound enhancing cognition. Biopharmaceutics & drug disposition. 1998:19. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-081x(199804)19:3<147::aid-bdd77>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kem W, Mahnir V, Prokai L, Papke R, Cao X, LeFrancois S, et al. Hydroxy metabolites of the Alzheimer's drug candidate 3-[(2, 4-dimethoxy) benzylidene]-anabaseine dihydrochloride (GTS-21): their molecular properties, interactions with brain nicotinic receptors, and brain penetration. Molecular pharmacology. 2004;65:56. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calhoun V, Adali T, Pearlson G, Pekar J. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Human Brain Mapping. 2001;14:140–151. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell A, Sejnowski T. An information-maximization approach to blind separation and blind deconvolution. Neural computation. 1995;7:1129–1159. doi: 10.1162/neco.1995.7.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephens S, Logel J, Barton A, Franks A, Schultz J, Short M, et al. Association of the 5 -upstream regulatory region of the 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit gene (CHRNA7) with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;109:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Pearlson G, Windemuth A, Ruano G, Perrone-Bizzozero N, Calhoun V. Combining fMRI and SNP data to investigate connections between brain function and genetics using parallel ICA. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30:241. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens KE, Kem WR, Mahnir VM, Freedman R. Selective alpha7-nicotinic agonists normalize inhibition of auditory response in DBA mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;136:320–327. doi: 10.1007/s002130050573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.