Abstract

Background

Low levels of dispositional anger and a good attention span are critical to healthy social emotional development, with attention control reflecting effective cognitive self-regulation of negative emotions such as anger. Using a longitudinal design, we examined attention span as a moderator of reciprocal links between changes in anger and changes in externalizing and internalizing problems from 4.5 to 11 years of age.

Method

Participants were children from the Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), assessed four times between 4.5 and 11 years. Composite scores for anger and attention were computed using indicators from multiple informants. Externalizing and internalizing problems were reported by mothers.

Results

Latent difference score analysis showed reciprocal lagged effects between increased anger and elevated levels of externalizing or internalizing problems. Significant moderating effects of attention indicated more persistent effects of anger on externalizing problems in the poor attention group. Although the poor and the good attention groups did not differ regarding the effects of anger on internalizing problems, significant moderating effects of attention indicated stronger and more persistent reciprocal effects of internalizing problems on anger in the poor attention group.

Conclusions

Attention control mechanisms are involved in self-regulation of anger and its connections with changes in behavioral and emotional problems. Strong attention regulation may serve to protect children with higher levels of dispositional anger from developing behavioral and emotional problems in middle childhood.

There is a noteworthy shift toward better self-control of anger in the transition from early (2–5 years) to middle (5–12 years) childhood. Current theory emphasizes a causal role of individual differences in effortful control of attention in the regulation of anger and other negative emotions (Posner & Rothbart, 2007, p. 19–22). Despite the well-established link between anger and behavioral and emotional problems, little is known about whether and how this link changes over the course of middle childhood, and much of the prior research has been cross-sectional and relied on data from a single informant. Therefore, in the current longitudinal study (4.5 to 11 years), we used data from multiple informants to examine the predictive links between changes in anger and changes in behavioral and emotional problems, as a function of level of attention regulation.

Anger and Attention

One of the most important components to healthy social-emotional development is the acquisition of skills to regulate anger and other negative emotions (Blair & Diamond, 2008). As children develop through early childhood and into middle childhood, most show clear improvements in self-control of anger and other negative emotions. This change co-occurs with improvements in attention and memory (i.e., executive function; Posner & Rothbart, 2007) as well as the acquisition of social and behavioral strategies for managing their anger. The result is that by 9–10 years of age, most children have acquired the capacity for controlling anger when it occurs—although there is wide individual variation in this apparent capacity over this entire developmental period (Bell & Deater-Deckard, 2007).

A substantial literature of human and animal research implicates distinct neural mechanisms for volitional control of attention in prefrontal cortex, and anger/frustration in the limbic system. Though distinct, the activity in these brain regions is integrated in ways that serve to regulate thought, emotion, and behavior (Gray, 2004; Posner & Rothbart, 2007). Consistent with this, temperament research points to a negative correlation between volitional control of attention and levels of negative affectivity and anger in particular (Calkins & Fox, 2002; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003)—a correlation that reflects a common underlying genetic etiology for poor emotion regulation and behavioral/emotional problems (Deater-Deckard, Petrill, & Thompson, 2007).

A common interpretation of the link between attention and anger—based on a large body of research that posits that affect, cognition and behavior is regulated in the frontal cortex (Luria, 1973)—is that volitional cognitive control of attention serves to modulate negative affect. Accordingly, children who are distractible and have difficulty maintaining attention are less able to engage attention to self-regulate negative emotions when they occur (Posner & Rothbart, 2007). The goal of the current study was to examine whether and how attention span—as a simple indicator of level of attention control—served to moderate the child’s level of dispositional anger. More importantly, we investigated whether this emotion regulation process was involved in growth or reduction in behavioral and emotional problems over middle childhood.

Within the cognitive neuroscience literature, much of the work implicating neural correlates of attention in moderation of behavior relies on direct measures of attention, acquired through cognitive tasks. Although direct, test-based laboratory measurement of attention regulation is ideal, it probably is not required to operationalize its effects at the level of behavior. Individual differences in questionnaire-based measures of attention span just like those utilized in the current study have been shown to be correlated with task-based measures of executive attention and other executive functions in children, for typical variation in temperament-based attention span, as well as inattention symptom severity for children with ADHD (for reviews see Rothbart, 2007; Willcutt, Doyle, Nigg, Faraone, & Pennington, 2005). However, one caveat is that these correlations are neither substantial nor specific to particular sub-components of attention regulation. As such, broad measurement of attention span in the current study provides a global “snapshot” of overall attention regulation.

Anger and Behavioral/Emotional Problems

There is wide variation in anger that is associated with individual differences in oppositional/aggressive behavior, i.e., externalizing, and emotional problems, i.e., internalizing (Eisenberg et al., 1995; Keane & Calkins, 2004). Children with high levels of anger in early childhood are more prone to develop externalizing and internalizing problems in childhood and adolescence (Bates, Pettit, Dodge, & Ridge, 1988; Eisenberg et al., 1995, 2009; Frick & Morris, 2004; Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

Through its self-regulatory capacity, cognitive control of attention may serve to moderate the effects of negative affect (including anger) on growth in behavioral/emotional problems (Gray, 2004; Posner & Rothbart, 2007). There appear to be joint contributions of anger and inattention to the development of behavioral/emotional problems in their additive and interactive effects. The combination of high levels of anger and poor attention regulation may be particularly detrimental to behavioral and emotional adjustment, whereas good attention may exert a protective effect on adjustment problems especially among chronically angry children. This general pattern has been detected in a number of community studies spanning early childhood to early adolescence, with the effects being more robust for externalizing problems compared to internalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2004, 2009; Lawson & Ruff, 2004; Oldehinkel, Hartman, Ferdinand, Verhulst, & Ormel, 2007). However, not all studies have found attention regulation to moderate the link between anger and adjustment problems (e.g., Belsky, Friedman, & Hsieh, 2001). The discrepancies between studies may be due to differences in samples (including children’s ages), designs (cross-sectional or longitudinal), and the informants and measures used.

Our goal in the current study was to conduct a comprehensive longitudinal analysis (4.5 to 11 years) using multiple informants and measures, to clarify developmental processes. Using structural equation modeling, we examined simultaneously changes in anger and changes in behavioral and emotional problems, as well as the temporally lagged prediction of changes in adjustment problems from prior levels of anger (and vice versa)—for all children, and also when comparing children with and without good attention spans. To our knowledge, the current study was the first to examine the moderating role of attention span in the link between dispositional anger and externalizing/internalizing problems into and through the transition to middle childhood, using multi-informant composite scores that serve to maximize predictive validity.

We addressed the following hypotheses and questions. First, we expected moderate to substantial (.4 to .6) stabilities across consecutive time points within both anger and inattention, and also explored whether there were systematic increases or decreases in stability from 4.5 to 11 years. Second, we expected to find a moderate (.2 to .4) contemporaneous correlation between higher anger and higher inattention, and explored whether this concurrent correlation changed systematically from 4.5 to 11 years of age. Finally, we investigated the cross-lagged effects over time between anger and internalizing/externalizing problems and examined whether attention moderates the dynamic processes between anger and internalizing/externalizing problems.

Method

Participants

We analyzed the public datasets of the National Institute of Child Health and Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development or SECCYD (http://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/supported/seccyd/datasets.cfm). Data collection began in 1991 in 9 states (Arkansas, California, Kansas, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin) and included 1,364 children (51.7% male) and their families when the children were one month of age. At the time of the child’s birth, all mothers were at least 18 and not more than 46 years old (M = 28.11, SD = 5.63). The current analyses include measures taken when the children were 4.5 years of age, and again in 1st, 3rd, and 5th grades. Since we were mainly interested in developmental changes in the links between temperament and psychopathology, the present sample included 1079 children who had mothers’ ratings of behavior problem measures for at least two time points over the four assessments. The sample was predominantly White (82%; Black, 12%; Asian, American Indian, or other, 6%). At the first time point (4.5 years) these 1079 children did not differ from the 66 children excluded from analyses (because they did not have at least two assessments of adjustment problems) with respect to race and family structure (two parent vs. one parent home). However, compared to the study sample, the excluded sample was more likely to include males, χ2 (1, N = 1145) = 3.46, p < .05, have a less educated mother, t (1143) = 4.36, p < .05), and have lower family incomes, t (1064) = 2.65, p < .05. Additional details about data collection procedures are documented in the study’s Manuals of Operation (http://secc.rti.org). The procedures of the current study were approved by the university’s internal review board as exempt status.

Measures

We used mothers’, fathers’, caregivers’ or teachers’ (depending on the child’s age), and observers’ ratings on items pertaining to several key indicators of anger and inattention (i.e., poor attention span or distractibility). The items were selected based on face validity from a variety of instruments (see Appendix).

Appendix.

Informants and item contents of the z-score composites, by time point, for mothers’ (M), fathers’ (F), caregivers’ (C), teachers’ (T), and observers’ (O) reports

| Age 4.5 | Age 7 | Age 9 | Age 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Behavior Checklist | M, F | M, F | M, F | M, F |

| Child Behavior Questionnaire | M, C | ----- | M, C | ----- |

| Child Behavior with Peers | ----- | ----- | M, F | M, F |

| Child-Parent Relationship Scale | M, F | M, F | M, F | M, F |

| Classroom Observation System | ----- | ----- | O | O |

| Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale | ----- | ----- | M, F, T | M, F, T |

| Social Skills Rating Scale | M, F | M, F, T | M, F, T | M, F, T |

| Teacher Report Form | C | T | T | T |

Child Behavior Checklist and Teacher Report Form

Inattention: can’t concentrate; fails to carry out assigned tasks; inattentive.

Child Behavior Questionnaire

Anger: the anger/frustration subscale.

Inattention: the attentional focusing subscale.

Child Behavior with Peers

Anger: loses temper easily; conflicts with peers.

Child-Parent Relationship Scale

Anger: child easily becomes angry at me; child angry/resistant after being disciplined.

Classroom Observation System

Inattention: the attention subscale

Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale

Anger: often loses temper; often is angry and resentful.

Inattention: often is easily distracted; often fails to pay close attention; often has difficulty continuously paying attention.

Social Skills Rating Scale

Anger: controls temper when arguing with other children; controls temper when in a conflict situation with parents or other adults.

Inattention: completes tasks within a reasonable time; attends to instructions.

Anger

We used the anger/frustration (α = .76) subscale from the Child Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001) and two items from the self-control scale (α = .82 for mothers, .77 for fathers, and .91 for teachers) of the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliott, 1990). Two items from the Oppositional Defiant Disorder subscale of the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBD; Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, 1992) were used across parents’ and teachers’ ratings (α = .85 and .93, respectively). We used mothers’ and fathers’ ratings on two items from the Child-Parent Relationship Scale that was adapted from the Student- Teacher Relationship Scale (Pianta, 1992) as well as mothers’ and teachers’ ratings on one item from the Child Behavior with Peers questionnaire (Ladd & Profilet, 1996).

Inattention

We used mothers’ and fathers’ reports on the CBCL and teachers’ reports on the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach, 1991) pertaining to inattention. We used the attentional focusing subscale (α = .74) from the CBQ, and one parent-rated item and one teacher-rated item from the SSRS. Three scores from the DBD were used across parents’ and teachers’ ratings (α = .86 and .91, respectively). Additoinally, we used the attention subscale from the Classroom Observation System, developed by the SECCYD Steering Committee, that records discrete child behaviors and interactions with others in the classroom (α = .79; inter-observer reliability, r = .96).

To develop composite scores for anger and inattention, and assess their internal consistency at each time point, we conducted principal components analyses (PCA) for each set of items, separately for each construct and each time point (8 PCA models in total), and by estimating the first principal component. Internal consistency was acceptable. For inattention, explained variance in the indicators ranged from 44% to 55% and loadings were from .35 to .89. For anger, internal consistency was slightly lower. Explained variance ranged from 29% to 33%, with loadings from .21 to .74. Items were reverse scored if necessary so that higher scores indicated higher levels of dispositional anger and inattention (poor attention span). Every indicator was standardized, averaged, and standardized again to yield composite z-scores within each of the four time points for anger (α = .70, .72, .86, and .87 for 4.5 years, 1st, 3rd, and 5th grades respectively), and inattention (α = .75, .81, .72, and .88 for 4.5 years, 1st, 3rd, and 5th grades respectively).

Behavioral and emotional problems

Total raw scores for both internalizing problems (somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression) and externalizing problems (delinquent behavior, aggression) were obtained using mothers’ reports on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) at 4.5 years and in 1st, 3rd, and 5th grades. When examined using t-scores, the mean levels of CBCL ratings approximated the normed mean of 50, and nearly 2% of children showed a clinical level of internalizing or externalizing problems.

Statistical Analysis

We tested latent difference score (LDS) models (McArdle & Hamagami, 2001) to predict dynamic changes in externalizing/internalizing problems from repeatedly measured anger from age 4.5 to 11. We used the Amos 7.0 program (Arbuckle, 2006) that estimated parameters incorporating full information maximum likelihood (FIML) methods. The FIML methods allow data from all individuals to be included regardless of their pattern of missing data and are more appropriate than other commonly used methods such as mean substitution. A notable strength of the LDS analysis lies in its provision of a statistical framework for evaluating dynamic longitudinal changes within time series data while considering interrelationships between multivariate change processes (McArdle, 2009). Other analytic approaches for studying changes, such as bivariate latent growth curve modeling, cannot represent time-based dynamic relations, where the effect on change in one variable depends on the state of another variable and any prior change in the system over time. Additionally, compared to the use of a manifest difference score, the LDS model offers an advantage of modeling change in perfectly reliable scores over a time series (by partitioning true scores from measurement errors), thus reducing the likelihood of bias in the estimates of parameters describing that change and enhancing power.

The hypothesized LDS model included the time-varying predictor of anger to examine the prospective effects of anger on developmental changes in behavioral/emotional problems. Because anger scores were standardized z-scores compositing different scales reported by multiple informants, its time series data were constructed as a Markov simplex model based on manifest variables instead of an LDS model. Furthermore, our hypothesized model included bi-directional cross-lagged effects between anger and behavioral/emotional problems as well as the concurrent correlations between the two constructs within each time point. Therefore, this model allowed us to test whether anger predicts changes in behavioral/emotional problems or vice versa, after accounting for the autoregressive effects of the prior anger or behavioral/emotional problems.

Results

Table 1 presents zero-order correlations among anger, inattention, and behavioral/emotional problems over time. Our first hypothesis was that anger and inattention would show moderate to substantial stabilities. In fact, effect sizes for anger stability were substantial, with stability correlations for consecutive assessments ranged from .55 to .70. Stability for inattention showed moderate effect sizes with the range between .45 and .60. Within each construct, stability gradually increased over time. Consistent with our second hypothesis, the concurrent correlations between anger and inattention were moderate and the anger-inattention association significantly increased from 4.5 (r = .33) to 11 years (r = .43), z = −2.63, p < .05. Although not part of our hypotheses, it is noteworthy that the concurrent correlations between anger and behavioral/emotional problems were higher for anger-externalizing problems (r = .53 to .66) than for anger-internalizing problems (r = .26 to .36).

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations among Anger, Inattention, and Externalizing and Internalizing Problems from Age 4.5 to 11

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Anger (54 mo) | – | |||||||||||||||

| 2. | Anger (7yr) | .55 | – | ||||||||||||||

| 3. | Anger (9yr) | .47 | .63 | – | |||||||||||||

| 4. | Anger (11yr) | .46 | .60 | .70 | – | ||||||||||||

| 5. | Inattention (54 mo) | .33 | .28 | .29 | .28 | – | |||||||||||

| 6. | Inattention (7yr) | .20 | .31 | .28 | .23 | .45 | – | ||||||||||

| 7. | Inattention (9yr) | .15 | .20 | .35 | .24 | .37 | .55 | – | |||||||||

| 8. | Inattention (11yr) | .21 | .27 | .34 | .43 | .40 | .59 | .60 | – | ||||||||

| 9. | Internalizing (54mo) | .26 | .23 | .19 | .19 | .19 | .10 | .12 | .11 | – | |||||||

| 10. | Internalizing (7yr) | .29 | .30 | .23 | .27 | .18 | .12 | .11 | .16 | .59 | – | ||||||

| 11. | Internalizing(9yr) | .25 | .24 | .36 | .30 | .18 | .11 | .21 | .19 | .50 | .64 | – | |||||

| 12. | Internalizing (11yr) | .25 | .24 | .30 | .36 | .22 | .11 | .16 | .25 | .49 | .64 | .65 | – | ||||

| 13. | Externalizing(54mo) | .53 | .46 | .43 | .43 | .41 | .24 | .23 | .26 | .57 | .43 | .37 | .44 | – | |||

| 14. | Externalizing(7yr) | .46 | .59 | .54 | .53 | .38 | .31 | .28 | .32 | .38 | .56 | .39 | .42 | .69 | – | ||

| 15. | Externalizing(9yr) | .42 | .51 | .66 | .55 | .35 | .30 | .34 | .35 | .32 | .39 | .55 | .41 | .60 | .73 | – | |

| 16. | Externalizing(11yr) | .37 | .42 | .53 | .62 | .36 | .24 | .28 | .41 | .32 | .40 | .41 | .60 | .60 | .68 | .73 | – |

Note. Bivariate N = 830 to 1007, all significant at p < .05 (two-tailed).

We conducted repeated-measures general linear modeling (GLM) analysis to examine whether there were significant developmental changes in the levels of problem behaviors differed by gender. Non-significant time by gender interactions suggested that changes in behavioral/emotional problems did not differ between boys and girls, F (3, 856) = .56, p = .64 for externalizing problems and F (3, 856) = .87, p = .46 for internalizing problems. Based on these results, child gender was not considered in the main LDS models.

Two-group structural equation models were used to test our third hypothesis regarding the moderating effects of attention in the link between anger and behavioral/emotional problems. We formed poor (above median, n = 540) vs. good attention (below median, n = 539) groups based on each individual’s grand mean of the inattention composites from 4.5 to 11 years. We first fit a Configural Invariance model in which all parameters were freely estimated across the two groups. The Configural Invariance model was the least restricted model among those tested. In subsequent models, we imposed equality constraints hierarchically to test numeric invariance between poor and good attention groups with respect to the effects of anger on behavioral/emotional problems (the Equal Anger Effect model) and the effects of behavioral/emotional problems on anger (the Equal Behavior Problem Effect model).

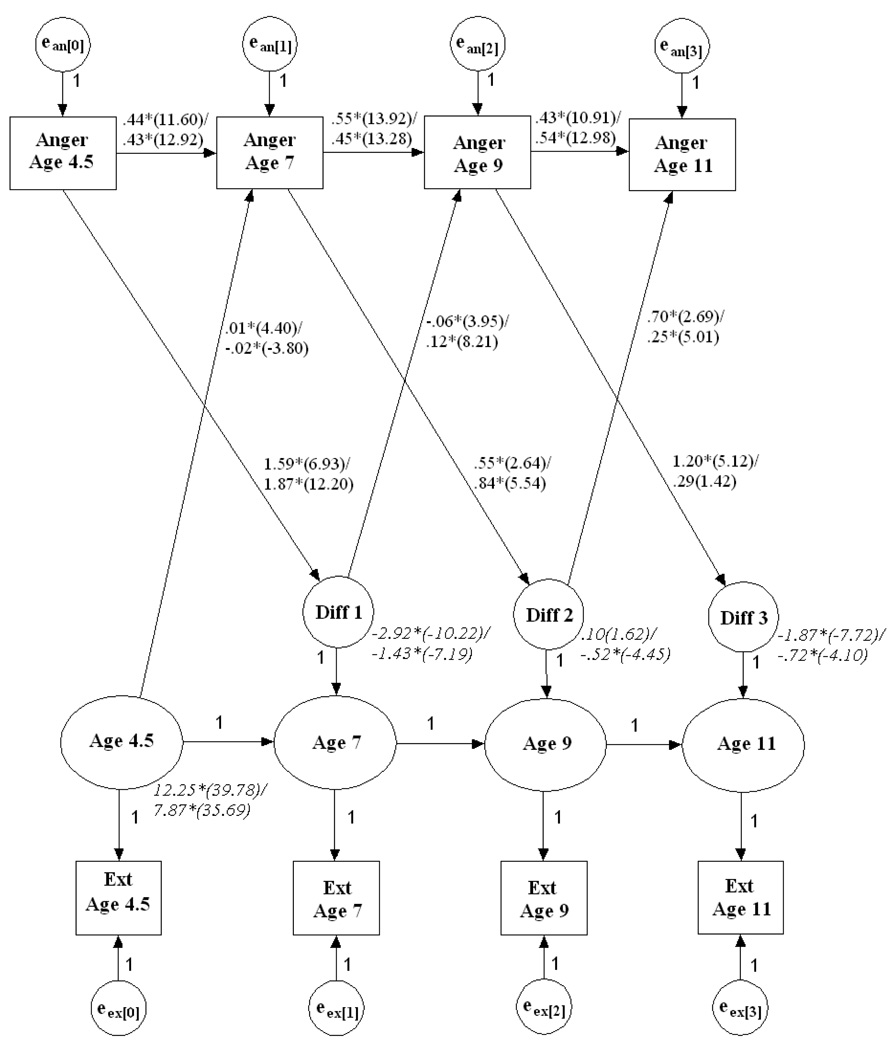

In Table 2, the chi-square difference tests comparing nested model fits indicated that the Configural Invariance model provided the best fit for externalizing problems. Poor and good attention groups showed significantly different patterns and magnitude for the effects of anger on externalizing problems as well as the effects of externalizing problems on anger. In particular, as shown in Figure 1, the poor attention group showed more persistent effects of anger on externalizing problems over time, compared to the good attention group. In the poor attention group, anger at 4.5, 7, 9, and 11 years consistently predicted smaller decreases, or in some cases larger increases, in externalizing problems from 4.5 to 7 years, from 7 to 9 years, and from 9 to 11 years. In addition, higher initial levels of externalizing problems at 4.5 years predicted increases in anger between 4.5 and 7 years. Larger increases in externalizing problems between 4.5 and 7 years were related to smaller increases in anger between 7 and 9 years, whereas larger increases in externalizing problems between 7 and 9 years were related to larger increases in anger between 9 and 11 years. The model-estimated mean levels of externalizing problems decreased from 12.25 to 7.56 over the four assessments, indicating significant decreases between 4.5 and 7 years and between 9 and 11 years.

Table 2.

Comparisons of Latent Difference Score Models for Anger and Externalizing/Internalizing Problems Moderated by Attention

| Model Label | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | Comparison | Δχ2 | Δdf | p(d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing Problems | ||||||||

| a. Configural Invariance | 349.12 | 38 | .93 | .09 | ||||

| b. Equal Anger Effects | 358.34 | 41 | .93 | .09 | a vs. b | 9.22 | 3 | < .05 |

| c. Equal Behavior Problem Effects | 460.98 | 41 | .90 | .10 | a vs. c | 111.86 | 3 | < .05 |

| Internalizing Problems | ||||||||

| a. Configural Invariance | 215.32 | 32 | .94 | .07 | ||||

| b. Equal Anger Effects | 218.98 | 35 | .94 | .07 | a vs. b | 3.65 | 3 | .30 |

| c. Equal Behavior Problem Effects | 248.94 | 38 | .93 | .07 | b vs. c | 29.97 | 3 | < .05 |

Note. Sample size is 540 for the poor attention group and 539 for the good attention group. CFI = comparative-fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; Δχ2 = difference in likelihood ratio tests; Δdf = difference in df; p(d) = probability of the difference tests. Best-fitting models are in bold face.

Figure 1.

Latent difference score model of the moderation of inattention between anger externalizing problems from age 4.5 to age 11. Ext. = externalizing problems; Diff = latent difference score factor; and e = measurement error. Values given are unstandardized coefficients with critical ratio (CR) in parentheses. CR that exceeds greater than 1.96 is significant using a significance level of .05. For each path, the coefficients (CR) are listed for poor attention/good attention groups. For the intercept (Age 4.5) and latent difference score (Diff) factors of externalizing problems, estimated means (CR) are presented in italics. For clarity of presentation, significant contemporaneous correlations between anger and externalizing problems are not shown: r = .45–.59 for the high inattention group and r = .41–.62 for the low inattention group. * p < .05.

For the good attention group, the effects of anger on externalizing problems decreased over time. Anger at 4.5 and 7 years predicted smaller decreases, or some cases larger increases, in externalizing problems from 4.5 to 7 years and from 7 to 9 years. However, the prospective effect of anger at 9 years on changes in externalizing problems from 9 to 11 years was not significant. Significant reciprocal effects of externalizing problems on anger indicated that higher initial levels of externalizing problems at 4.5 years were related to smaller increases in anger between 4.5 and 7 years. However, increases in externalizing problems between 4.5 and 7 years and between 7 and 9 years predicted increases in anger between 7 and 9 years and between 9 and 11 years. Children in the good attention group showed significantly lower initial levels of externalizing problems compared to those in the poor attention group, and their estimated means of externalizing problems decreased from 7.87 to 5.20 over the four repeated assessments indicating consistently significant decreases between consecutive time points.

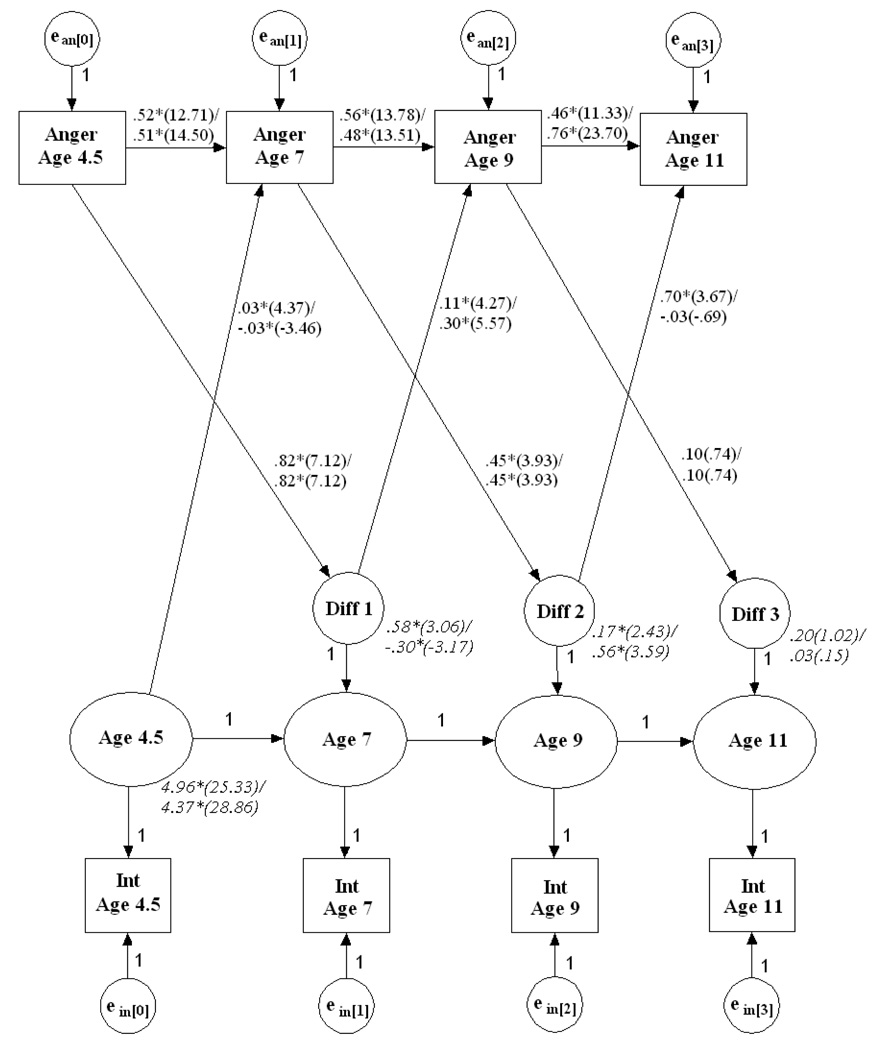

In Table 2, nested model comparisons indicated that the Equal Anger Effect model provided the best fit for internalizing problems. Results of the best-fitting model indicated that the reciprocal effects of internalizing problems on anger were stronger and more persistent in the poor attention group, but the two groups did not differ regarding the effects of anger on internalizing problems (see Figure 2). Regardless of inattention level, higher anger at 4.5 and 7 years predicted greater increases in internalizing problems from 4.5 to 7 years and from 7 to 9 years. Differential reciprocal effects between the two attention groups suggested that the patterns of reciprocal effects were more consistent and stronger in general for the poor attention group. For children in the poor attention group, higher initial levels of internalizing problems at 4.5 years and increases in internalizing problems between 4.5 and 7 years and between 7 and 9 years consistently predicted increased anger at the following assessment. The model-estimated mean levels of internalizing problems increased from 4.96 to 5.91 over the four repeated assessments, indicating significant increases between 4.5 and 7 years, and between 7 and 9 years.

Figure 2.

Latent difference score model of the moderation of inattention between anger internalizing problems from age 4.5 to age 11. Int. = internalizing problems; Diff = latent difference score factor; and e = measurement error. Values given are unstandardized coefficients with critical ratio (CR) in parentheses. CR that exceeds greater than 1.96 is significant using a significance level of .05. For each path, the coefficients (CR) are listed for poor attention/good attention groups. For the intercept (Age 4.5) and latent difference score (Diff) factors of internalizing problems, estimated means (CR) are presented in italics. For clarity of presentation, significant contemporaneous correlations between anger and internalizing problems are not shown: r = .19–.33 for the high inattention group and r = .22–.35 for the low inattention group. * p < .05.

In contrast, for the good attention group, higher initial levels of internalizing problems at 4.5 years were associated with smaller increases in anger between 4.5 and 7 years, and increases in internalizing problems between 4.5 and 7 years predicted increases in anger between 7 and 9 years. Changes in internalizing problems between 7 and 9 years did not predict changes in anger between 9 and 11 years. Children in the good attention group showed consistently lower levels of internalizing problems compared to those in the poor attention group, with some fluctuations. Their estimated means of internalizing problems showed significant decreases between 4.5 and 7 years (from 4.37 to 4.07), significant increases between 7 and 9 years (from 4.07 to 4.63), and then no significant changes between 9 and 11 years (from 4.63 to 4.66).

Discussion

We investigated longitudinal associations between dispositional anger and externalizing/internalizing problems from 4.5 to 11 years of age, in an effort to better understand the nature of the self-regulation mechanisms involving attention. We examined the bi-directional cross-lagged associations between anger and behavioral/emotional problems to see if there was any evidence of directionality from one construct predicting change in the other, or evidence for a moderating effect of attention. This investigation represents the first study to examine the moderating role of attention on these processes over the entire transition from early childhood through middle childhood.

There was moderate to substantial stability of individual differences in anger, attention span, externalizing and internalizing, with consecutive time point stability coefficients in the .5 to .7 range. However, these stability correlations also indicated that no more than half of the variance for any given construct or time point was explained by the prior assessment of that construct, indicating moderate to substantial change in individual rank order from one time point to the next. In particular, given that the composite z scores of anger and inattention included information from multiple informants and covered somewhat different measures across times, it is unlikely that these changes were simply due to random error. On the contrary, the most parsimonious explanation is that during the transition into and through middle childhood, children are systematically “shuffling” relative positions on these dimensions of temperament and maladjustment.

Turning to analysis of these changes, increased anger was related to elevated levels of both externalizing and internalizing problems as expected (Oldehinkel et al., 2007; Rydell, Berlin, & Bohlin, 2003). In addition, and in support of theory and research emphasizing a direct effect of effortful control of attention on healthy social-emotional development (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Posner & Rothbart, 2007), we found that children with relatively poor attention control consistently showed higher levels of externalizing and internalizing problems from 4.5 to 11 years, compared to children with good attention control.

With respect to attention serving cognitive self-regulation, levels of inattention moderated the link between anger and externalizing problems in a way that was suggestive of an emotion regulation process. For children with poor attention control, increases in anger predicted larger increases or smaller decreases in externalizing problems consistently across middle childhood. For children with good attention control, these lagged predictive effects notably decreased over time resulting in becoming non-significant by the end of middle childhood. Thus, the developmental link between changes in anger and changes in externalizing problems was more obvious and persistent over time for children with poor attention regulation—a longitudinal effect that is consistent with prior shorter-term longitudinal and cross-sectional studies (Eisenberg et al., 2004, 2009; Lawson & Ruff, 2004; Oldehinkel et al., 2007). However, we did not find evidence for a moderating effect of attention on the link between anger and changes in internalizing problems. This also is consistent with at least two prior studies showing statistical interactions between effortful control of attention and anger in the prediction of externalizing but not internalizing problems (Eisenberg et al., 2004; Lawson & Ruff, 2004). However, this lack of a moderated effect for anger-internalizing does not rule out other possible emotion regulation mechanisms involving dispositional fear (Oldehinkel et al., 2007).

Although anger predicted subsequent changes in adjustment problems, we also found a reciprocal effect whereby prior externalizing and internalizing problems predicted changes in anger and such reciprocal effects differed significantly between the poor vs. good attention groups. For externalizing problems, as expected, increases in externalizing problems were positively related to larger increases in anger among children with good attention. For children with poor attention, this effect was less consistent: Increases in externalizing problems between ages 4.5 and 7 were predictive of smaller increases in anger between ages 7 and 9, whereas increases in externalizing problems between ages 7 and 9 were predictive of larger increases in anger between ages 9 and 11. The negative association between changes in externalizing problems and changes in anger was not expected, nor do we know of any theoretical explanation for this pattern. Turning to anger-internalizing problem associations, increases in internalizing problems were consistently predictive of larger increases in anger over all time points among children with poor attention, whereas such cross-lagged effects were limited for anger changes between ages 7 and 9 among children with good attention. Therefore, there appeared to be more systematic pattern in the cross-lagged effects from anger to behavioral/emotional problems compared to the reciprocal cross-lagged effects from behavioral/emotional problems to anger.

The findings were clear in pointing to increases in the magnitude of anger-inattention connection from 4.5 to 11 years of age. The correlation between anger and inattention ranged between .31 and .43 over this entire age range, which falls in the middle of the range of effect sizes, typically from −.2 to −.4, found in previous studies of effortful control of attention and anger/negative affect (Deater-Deckard et al., 2007; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Rydell et al., 2003). This association between anger and poor attention control is in keeping with the theoretical notion that attentional skill may help attenuate negative affect such as anger (Posner & Rothbart, 2007). In general, the effects of anger on externalizing and internalizing problems appeared to decline over time with development in our LDS models, with the only exception being anger effects on externalizing problems among children with poor attention control, coinciding with the increased magnitude of the association between anger and attention span.

Caveats and Conclusions

There are several limitations of the current study to bear in mind. First, by examining items and scales from various informants across different instruments at any given point in time, we had to standardize the indicators of anger and inattention to create meaningful and interpretable composite z-scores. This means that we were not able to examine sample-wide mean-level changes over time for anger and inattention. A second limitation is that the approach we used did not permit examination of informant- or context-specific sources of variance. Although on the whole discarding such variance has the effect of improving reliability and predictive validity of a construct, it also is likely that at least some of the variance that is removed could yield further insights if it were examined in its own right. Third, this study is also limited in its generalizability of the findings to clinical samples because few participants evidenced clinical levels of internalizing and externalizing problems. Finally, our secondary data analysis for constructing anger and inattention composites was limited by there being only a few observational items and mostly questionnaire-based items. Ideally, a broader variety of informants and methods (e.g., observations in multiple settings, interviews) should be used. In future work, studies should integrate multiple levels of assessment (e.g., behavior in laboratory paradigms, behavior in naturalistic contexts, and informant and self reports). In addition, although we believe that the inattention scores in the current study are indicative of cognitive control mechanisms that serve self-regulation (based on the temperament and ADHD literatures; e.g., Rothbart, 2007; Willcutt et al., 2005), these scores were not direct assessments of the various components of attention and possibly conflated temperamental attention and behavioral attention. It should be noted that although the dimensions of cognitive, behavioral, and temperamental attention have similarities and are strongly related to the higher-order attention factor, the relations among these domains are still heavily debated (e.g., see Watson, Kotov, & Gamez, 2006).

Despite these limitations, this investigation addressed several shortcomings present within the temperament and psychopathology literatures. We examined a large diverse national sample that was assessed for an extended period of time. Also, the variables were composite scores based on multiple informants and methods. This approach maximizes power and the predictive validity of constructs by reducing random error, while it minimizes the study-wide type-1 error rate by vastly reducing the number of statistical tests conducted. In addition, we examined longitudinal change in both externalizing and internalizing problems, and use of LDS models (rather than latent growth models) permitted more precise estimation of the reciprocal dynamic of change. To our knowledge, the current study is the first study that examines the moderating role of cognitive control involving optimally reliable latent change scores using more than two measurement occasions, thus avoiding limitations of prior longitudinal research using two-wave panel models which allow predictions of only a single time lag.

In conclusion, contemporary developmental theories emphasize the crucial role of volitional control of attention on the self-regulation of negative affect (Calkins & Fox, 2002). Though any definite causal mechanism could not be tested using the correlational data in the current study, our findings illustrate detrimental effects of dispositional anger on the development of externalizing and internalizing problems in the transition into and throughout middle childhood. Importantly, the prospective effects of anger on externalizing problems were attenuated over time for children with good attention spans, whereas such effects of anger on internalizing problems were not moderated by attention span level. There is also evidence that the prospective, reciprocal effects of externalizing and internalizing problems on changes in anger were more pronounced among children with poor attention control. Thus, the current findings stress that attention regulation can modulate the dynamic processes between expressions of negative emotionality and the development of psychopathology. Furthermore, these results imply that enhancing attention skills in children may be an important target in the prevention and treatment of externalizing and internalizing problems among at-risk children who are prone to anger.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the SECCYD study participants and research staff. We also thank Zhe Wang for her assistance with the data preparation and Gregory Longo for his editorial assistance. This work was supported by NICHD HD54481. The Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development was conducted by the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, and was supported by NICHD through a cooperative agreement that calls for scientific collaboration between the grantees and the NICHD staff. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health And Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 7.0 Updated to the Amos User’s Guide. Chicago: Small Waters Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Ridge B. Interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:982–995. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, Deater-Deckard K. Biological systems and the development of self-regulation: Integrating behavior, genetics, and psychophysiology. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:409–420. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181131fc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Friedman SL, Hsieh K-H. Testing a core emotion-regulation prediction: Does early attentional persistence moderate the effect of infant negative emotionality on later development? Child Development. 2001;72:123–133. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Diamond A. Biological processes in prevention and intervention: The promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:899–911. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA. Self-regulatory processes in early personality development: A multilevel approach to the study of childhood social withdrawal and aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:477–498. doi: 10.1017/s095457940200305x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Petrill SA, Thompson L. Task persistence, anger/frustration, and conduct problems in childhood: A behavioral genetic analysis. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2007;48:80–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg R, Fabes RA, Murphy B, Maszk P, Smith M, Karbon M. The role of emotionality and regulation in children’s social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 1995;66:1360–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Losoya SH, Valiente C, Shepard SA. The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:193–211. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Cumberland A, Shepard SA, Thompson M. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children's resiliency and adjustment. Child Development. 2004;75:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, Losoya SH. Longitudinal relations of children's effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Morris AS. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:54–68. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JR. Integration of emotion and cognitive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. The social skills rating system. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Keane SP, Calkins SD. Predicting kindergarten peer social status from toddler and preschool problem behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:409–423. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030294.11443.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Knaack A. Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1087–1112. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Profilet SM. The Child Behavior Scale: A teacher-report measure of young children’s aggressive, withdrawn, and prosocial behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1008–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson KR, Ruff HA. Early attention and negative emotionality predict later cognitive and behavioural function. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Luria AR. Frontal lobes and the regulation of behavior. In: Pribram KH, Luria AR, editors. Psychophysiology of the frontal lobes. New York: Academic Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:577–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F. Latent difference score structural models for linear dynamic analyses with incomplete longitudinal data. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 139–175. [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Hartman CA, Ferdinand RF, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Effortful control as modifier of the association between negative emotionality and adolescents' mental health problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:523–539. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WEJ, Fabiano GA, Massetti GM. Evidence-Based Assessment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:449–476. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R. Student-Teacher Relationship Scale. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Educating the human brain. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Temperament, development, and personality. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;75:1336–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72:1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rydell A, Berlin L, Bohlin G. Emotionality, emotion regulation, and adaptation among 5- to 8-year-old children. Emotion. 2003;3:30–47. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Kotov R, Gamez W. Basic dimensions of temperament in relation to personality and psychopathology. In: Krueger RF, Tackett JL, editors. Personality and psychopathology. New York: Guildford Press; 2006. pp. 7–38. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]