Abstract

Surface Plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy is a useful technique for thermodynamically characterizing peptide–surface interactions; however, its usefulness is limited to the types of surfaces that can readily be formed as thin layers in nanometer scale on metallic biosensor substrates. Atomic force microscopy (AFM), on the other hand, can be used with any microscopically flat surface, thus making it more versatile for studying peptide–surface interactions. AFM, however, has the drawback of data interpretation due to questions regarding peptide-to-probe–tip density. This problem could be overcome if results from a standardized AFM method could be correlated with SPR results for a similar set of peptide–surface interactions so that AFM studies using the standardized method could be extended to characterize peptide–surface interactions for surfaces that are not amenable for characterization by SPR. In this paper, we present the development and application of an AFM method to measure adsorption forces for host–guest peptides sequence on surfaces consisting of alkanethiol self–assembled monolayers (SAMs) with different functionality. The results from these studies show that a linear correlation exists between these data and the adsorption free energy (ΔG°ads) values associated with a similar set of peptide–surface systems available from SPR measurements. These methods will be extremely useful to thermodynamically characterize the adsorption behavior for peptides on a much broader range of surfaces than can be used with SPR to provide information related to understanding protein adsorption behavior to these surfaces and to provide an experimental database that can be used for the evaluation, modification, and validation of force field parameters that are needed to accurately represent protein adsorption behavior for molecular simulations.

I. INTRODUCTION

Wei and Latour previously developed an experimental method for the characterization of peptide adsorption behavior that enables adsorption free energy (ΔG°ads) to be determined using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy in a manner that minimizes the effects of peptide–peptide interactions at the adsorbent surface and provides a direct means of determining bulk-shift effects.1 SPR was chosen because it is one of the most sensitive and directly applicable methods to characterize adsorption/desorption behavior to determine adsorption free energy.1–4 This technique is inherently suitable for use with gold–alkanethiol self-assembled monolayer (SAM) surfaces and has been widely applied in recent years to study both peptide and protein adsorption behavior.3, 5–6 After initial development, Wei and Latour applied this method to characterize the adsorption behavior of a large series of 108 different peptide–SAM systems involving 12 different zwitterionic host–guest peptides (TGTG–X–GTGT where G and T are glycine and threonine, with X = V, A, G, L, F, W, K, R, D, S, T and N (using the standard single-letter amino acid code); with charged NH3+ and COO− groups at the beginning and end of the peptide chain, respectively, (i.e., charged N- and C-termini) at pH=7.4) on nine different SAM surfaces (SAM–Y with Y = CH3, OH, NH2, COOH, OC 6H5, (OCH2CH2)3OH, NHCOCH3, OCH2CF3 and COOCH3) to represent common functional groups contained in organic polymers.3 These results provide values that can also be calculated by molecular simulation using a selected empirical force field,7 so that comparisons between the calculated and experimentally determined values of ΔG°ads can be used to assess the validity of the force field to accurately represent protein adsorption behavior. However, while SPR is a useful technique for measuring peptide–SAM surface interactions, its usefulness is limited to materials that can form high-quality uniform nanoscale–thick films on a metallic surface that can be used to generate an SPR signal. This limitation makes it prohibitively difficult to extend our previously developed SPR methods1, 3 for use to assess peptide adsorption behavior on many types of polymers and ceramic materials that are of direct interest in specific applications, such as the biomaterials field. Thus, alternative methods are needed to characterize peptide-surface interactions for these types of materials.

Compared to SPR, AFM has also been widely applied to characterize biological molecular recognition processes because of its high force sensitivity and the capability of operating under different physiological conditions and on any material with a microscopically flat surface.8–12 However, the use of AFM for these applications can result in difficulties in interpreting molecular force data (e.g., adsorption behavior) for peptide–surface interactions because: (i) force spectroscopy does not provide an immediate way to discriminate between the specific peptide-surface interactions from the nonspecific probe tip–surface interactions, and (ii) the absence of a direct way to determine the actual number of interacting molecules for a corresponding force measurement.13 A solution to the first difficulty is provided by linking the interacting molecules to the probe tip of an AFM tip or the substrate’s surface with long, flexible, hydrophilic molecular tethers that can provide a defined tip–sample distance to spatially isolate the nonspecific probe–sample interactions from the peptide–surface interaction. 14–19 In addition, if the tether length is longer than the peptides that are tethered, the tether will remain flexible during the adsorption process when the probe tip is brought closer than the extended length of the tether to the surface, thus allowing the peptide to adsorb in a manner that is minimally influenced by the tether.20–21 While the use of a tether provides a means of effectively separating the influence of the probe tip from the peptide-surface interactions, a method of dealing with the uncertainty in the number of tethered peptides per unit area of the probe tip remains to be found. One potential approach to overcome this problem would be to compare AFM results for peptide-surface interactions using a standardized methodology to consistently obtain the same probe tip density (although unknown) to thermodynamic measurements for the same systems obtained by SPR. If a strong correlation is found between these two measures of peptide adsorption behavior, then the standardized AFM method and SPR correlation plot could be applied to obtain effective thermodynamic values for other peptide-surface systems as well.

Based on this premise, in this study we developed a standardized AFM protocol to measure the force of peptide desorption (Fdes) from SAM surfaces and applied it to a large set of the same peptide-SAM surfaces that we used to generate our benchmark adsorption free energy (ΔG°ads) data set that we previously obtained by SPR.3 We then plotted the values of Fdes against ΔG°ads for this same set of peptide-SAM systems to determine the level of correlation between these two experimental parameters. If a strong correlation can be shown, this will provide a means of using this standardized AFM technique to characterize ΔG°ads for peptide adsorption processes.22 AFM studies using this standardized method could then be extended to effectively determine ΔG°ads values for peptide–surface interactions for surfaces that are not amenable for characterization by SPR. The significance of this work is two-fold. First, it will not only provide the ability to relate AFM results to a fundamental thermodynamic property characterizing peptide-surface interactions. Secondly, and possibly most importantly, it will also provide a much more versatile approach to generate benchmark adsorption free energy values that are currently lacking for the validation of empirical force field parameters for molecular simulations that can be used for a much broader range of materials than is currently available with the previously developed SPR methods alone.

As presented below, the host-guest peptide model that we used in our previous work was in the form of TGTG–X–GTGT.1, 3 However, to use this type of peptide model for AFM, it had to be slightly modified by the incorporation of a cysteine (C) residue so that it could be tethered to the AFM tip. The first objective of this research work was therefore to conduct studies to confirm that cysteine could be incorporated into this host-guest peptide model without substantially changing the adsorption behavior of the peptide. By confirming this equivalence, then our previous determined ΔG°ads values3 could be directly correlated with the AFM results using the modified peptide model. The subsequent objectives of this research were then to conduct AFM experiments to (i) measure peptide–surface desorption forces for a large set of peptide–surface systems for which ΔG°ads values are available from our previous SPR studies,1, 3 (ii) to determine if a linear correlation exists between the AFM and SPR data, and (iii) if a strong correlation is found, to then apply these methods to estimate the values of ΔG°ads for as set of peptide–surface systems that cannot be readily tested by SPR and assess the reasonableness of these results.

II. EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

II.a. Host–Guest Peptide Model

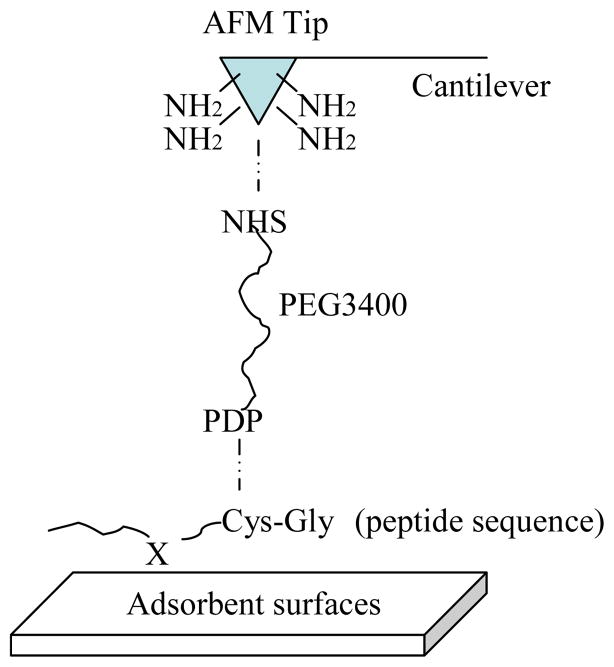

For our new SPR and force measurement studies by AFM, we used the same basic host–guest peptide with zwitterionic end–groups as we used for the SPR studies in our previous work,1, 3 but with the eighth amino acid (glycine) replaced by cysteine (i.e., G8C swap) to provide a means of tethering the peptide to an AFM tip by a 3.4 kDa PEG tether (polydispersity index =1.08) as illustrated in Figure 1. (i.e., TGTG–X–GTCT used in place of TGTG–X–GTGT, where G, T and C are glycine (–H side–chain), threonine (–CH(CH3)OH side–chain) and cysteine (–CH2SH side chain)). We used the following three X guest amino acids: valine (–CH(CH3)2 side chain), aspartic acid (–CH2COO− (pK = 3.97)23 side chain) and leucine (–CH2CH(CH3)2 side chain). These host–guest peptides were synthesized and characterized by analytical HPLC and mass spectral analysis by Synbiosci Corp., Livermore, CA, which showed that all of the peptides were ≧98% pure.

Figure 1.

AFM Tip linkage. Peptide sequences were coupled to AFM tips via a 3.4 kDa polyethylene glycol (PEG) crosslinker. The n–hydroxy–succinimide (NHS) end of the PEG was covalently bound to amines on the tip before the peptide was attached to the pyridyldithio–propionate (PDP) end via cysteine.

II.b. Surface Chemistry

For the SPR studies, alkanethiol SAM surfaces on gold and a spin–coated poly(methyl-methacrylate) film on gold were used to determine ΔG°ads values associated with peptide–surface interactions. For AFM studies, the same set of SAM surfaces used for the SPR studies plus material surfaces relevant to the biomaterials field that could not be readily characterized by SPR were tested and the measured peptide–surface desorption forces were compared with ΔG°ads values determined from SPR measurements.3

II.b.1. Alkanethiol SAM Surfaces

All alkanethiols used here for the formation of the SAM monolayers on gold had a structure of HS(CH2)11–R, with R representing a variable surface functional group. Preliminary studies for the purpose of evaluating whether the G8C change in the peptide sequence significantly influences its adsorption behavior were conducted with SAM surfaces functionalized with –OH, –NHCOCH3, and –CH3 groups to cover the full range of ΔG°ads values based on the results presented in our previous work. 3 The AFM studies were conducted with a wider range of R terminal groups, which included: –OH, –CH 3, –NH2, –NHCOCH3, –OCH2CF3 or –(OCH2CH2)3OH (i.e., –EG3OH, EG: ethylene glycol segment) (alkanethiols purchased from Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA; Prochimia, Sopot, Poland; or Asemblon, Redmond, WA, USA). The bare gold surfaces were purchased from Biacore (SIA Au kit, BR–1004–05, Biacore, Inc., Uppsala, Sweden). Prior to use, all of the surfaces were sonicated (Branson Ultrasonic Corporation, Danbury, CT) at 50 °C for 1 min in each of the following solutions in order: “piranha” wash (7:3 (v/v) H2SO4 (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ)/H2O2 (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA), and a basic solution (1:1:3 (v/v/v) NH4OH (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA)/H2O2/H2O). After each cleaning solution, the gold slides were rinsed with nano–pure water and dried under a steady stream of nitrogen gas (National Welders Supply Co., Charlotte, NC, USA). The cleaned slides were rinsed with ethanol and incubated into the appropriate 1.0 mM alkanethiol solution in 100% (absolute) ethanol (PHARMCO–AAPER, Shelbyville, KY, USA) for a minimum of 16 hours. The formation of monolayers from the amine–terminated alkanethiols required additional procedures to be applied to avoid either an upside-down monolayer and/or multilayer formation. These monolayers were assembled from basic solution to assure that the amine terminus remained deprotonated (i.e., uncharged), which helps prevent the formation of an upside-down monolayer and subsequent multilayer formation.24 Accordingly, the 100% (absolute) ethanol used to prepare the amine terminated thiols was adjusted to pH≈12 by adding a few drops of triethylamine solution (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). After these pretreatments, each of the SAM surfaces was stored in their respective alkanethiol solution in a dark environment until used to prepare the biosensor surfaces.

After incubation in their respective alkanethiol solution, all SAM surfaces were sonicated with 100% (absolute) ethanol, rinsed with nano–pure water, dried with nitrogen gas and characterized by ellipsometry (GES 5 variable–angle spectroscopic ellipsometer, Sopra Inc., Palo Alto, CA), contact angle goniometry (CAM 200 optical contact–angle goniometer, KSV Instruments Inc., Monroe, CT), and X–ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, performed at NESCA/BIO, University of Washington, Seattle, WA). All XPS spectra were taken on a Kratos Axis–Ultra DLD spectrometer and analyzed by the Kratos Vision2 program to calculate the elemental compositions from peak area.

II.b.2. Materials Used for AFM Studies

The materials used for the AFM studies included (i) polymer sheets (Acrylite@AR–abrasion resistant poly(methyl methacrylate) (AR-PMMA) (SLU0125–D, Small Parts, Miramar, FL) of size 1 cm × 1 cm × 0.3 cm, Nylon 6/6 (SRN0062–C, Small Parts, Miramar, FL) of size 1 cm × 1 cm × 0.16 cm, and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) (STE0015–B, Small Parts, Miramar, FL) of size 1 cm × 1 cm × 0.07 cm, (ii) a titanium plate surface (SMTI035–B, Small Parts, Miramar, FL) of size 1 cm × 1 cm × 0.09 cm, and (iii) microscope-cover glass (12–540A, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) of size 0.18 cm × 0.18 cm × 0.02 cm. Prior to being used for desorption force measurement by AFM, all of the surfaces were sonicated (Branson Ultrasonic Corporation, Danbury, CT) at room temperature for 30 min in 0.3 vol. % Triton X–100 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). After the cleaning solution, these surfaces were rinsed with nanopure water, dried under a steady stream of nitrogen gas (National Welders Supply Co., Charlotte, NC, USA), and characterized by contact angle goniometry (CAM 200 optical contact–angle goniometer, KSV Instruments Inc., Monroe, CT) and X–ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, performed at NESCA/BIO, University of Washington, Seattle, WA).

II.b.3. Spin–Coated Polymer Film on Gold

Poly(methyl–methacrylate) (PMMA) (Mw=120,000, Mw/Mn=1.2) was spun from toluene (1.5% at 5000 rpm for 60 sec) to form a thin layer of size 1 cm × 1 cm ×11 nm on bare gold SPR sensor chip (spin–coating conducted through the Polymer Division–Biomaterial Group, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Gaitherburg, MD). The bare gold surfaces were purchased from Biacore (SIA Au kit, BR–1004–05, Biacore, Inc., Uppsala, Sweden). Prior to being used for ΔG°ads measurement by SPR, surfaces were sonicated (Branson Ultrasonic Corporation, Danbury, CT) at room temperature for 3 min in 0.3 vol. % Triton X–100 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). After the cleaning solution, these surfaces were then gently rinsed with nanopure water, dried under a stream of nitrogen gas (National Welders Supply Co., Charlotte, NC, USA), and characterized by contact angle goniometry (CAM 200 optical contact–angle goniometer, KSV Instruments Inc., Monroe, CT) and X–ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, performed at NESCA/BIO, University of Washington, Seattle, WA).

II.c. SPR Method

To accurately determine ΔG°ads for peptide adsorption using SPR, the influence of solute-solute (peptide–peptide in our case) interactions on the surface.1, 25 should be accounted for. From a standard SPR analysis, an adsorption model, such as the Langmuir model, is generally used to calculate ΔG°ads on the basis of the overall shape of the adsorption isotherm.2, 26–27 This, however, creates complications because solute–solute interactions may occur on the surface as the surface sites become filled, which can substantially influence the shape of the isotherm and invalidate the application of the Langmuir adsorption model.1 If the Langmuir model is still used despite the occurrence of solute–solute interactions, then substantial error might be introduced into the calculated value of ΔG°ads.

To address this problem, we have developed a chemical potential-based model to enable the effects of solute-solute interactions to be minimized so that ΔG°ads can be more accurately determined from the resulting adsorption data. SPR methods were then conducted for the TGTG-X-GTCT peptides (X = leucine, aspartic acid, and valine) over three SAM surfaces (SAM–OH, –CH3, or –NHCOCH3) spanning the range of free energy values for comparison with our previous results with the TGTG-X-GTGT peptide model to confirm that cysteine could be incorporated into this host-guest peptide model without substantially changing the adsorption behavior of the peptide. While the details of the development of our experimental procedures for the SPR studies are presented in our previous papers,1, 3 a brief description of these methods will be presented in the following section. To determine ΔG°ads for peptide–surface interaction by SPR, the adsorption experiments were conducted using a Biacore X SPR spectrometer (Biacore, Inc., Piscataway, NJ) with 1x mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 140 mM NaCl, pH=7.4; Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) used as the running buffer, which was filtered and degassed before each SPR experiment.

II.c.1. Adsorption Experiments by SPR

Eight concentrations of each of the peptide solutions (0.039, 0.078, 0.156, 0.312, 0.625, 1.25, 2.50, 5.00 mg/mL) were prepared in the filtered and degassed 1x PBS buffer through serial dilutions of stock solutions of the peptide in clean vials. The pH of each stock solution was adjusted to 7.4 with 0.1 N NaOH (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) or 0.1 M HCl (Mallinckrodt Chemical, Inc, Paris, KY) before dilution. The actual concentration of the stock and diluted peptide solution was then calibrated by BCA analysis (BCA protein assay kit, prod. 23225, Pierce, Rockford, IL) against a BSA standard curve and by the measurement of solution refractive index (AR 70 Automatic Refractometer, Reichert, Inc., Depew, NY).

Before the adsorption experiment, the SPR sensor chip was docked in the instrument and pretreated following a standard protocol that involved several injections of 0.3 vol. % Triton X–100 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) followed by a “wash” operation, which is necessary to obtain a stable SPR sensorgram response using this instrument. After the initial preparation step, each surface was prepared for an adsorption measurement by running 50 μL injections of concentrated peptide solution (5.0 mg/mL) over the SAM surface several times followed by PBS wash until a fully reversible adsorption signal was obtained. Then, eight different concentrations of each peptide solution were injected over each functionalized–SAM SPR chip in random order with a flow rate of 50 μL/min followed by the PBS wash to desorb the peptide from the surface. Finally, a blank buffer injection was administered to flush the injection port and a set of regeneration solution injections was then performed to prepare the surface for the next series of peptide sample injections.

II.c.2. Data Analysis of ΔG°ads from SPR

As described in our previous work,1, 3 the equations that are used for the determination of ΔG°ads from the adsorption isotherms that are generated from the raw SPR data plots were derived based on the chemical potential of the peptide in its adsorbed state compared to being in bulk solution. SPR sensorgrams in the form of resonance units (RU; 1 RU = 1.0 pg/mm2)28 vs. time were recorded for six independent runs of each series of peptide concentrations over each SAM surface at 25 °C and the data were then used to generate isotherm curves for analysis by plotting the raw SPR signal vs. peptide solution concentration. During an SPR experiment to measure the adsorption of a peptide to a surface, the overall change in the SPR signal (i.e., the raw SPR signal) reflects both of the excess amount of adsorbed peptide per unit area, q (measured in RUs), and the bulk–shift response, which is linearly proportional to the concentration of the peptide in solution. This can be expressed as:

| (1) |

where Cb (moles/L, M) is the concentration of the peptide in bulk solution, C° is the peptide solution concentration under standard state conditions (taken as 1.0 M), m (RU/M) is the proportionality constant between the bulk shift in the SPR response and the peptide concentration in the bulk solution, K (unitless) is the effective equilibrium constant for the peptide adsorption reaction, and Q (RU) is amount of peptide adsorbed at surface saturation. Equation (1) was best–fitted to each isotherm plot of the raw SPR response vs. Cb by non–linear regression to solve for the parameters of Q, K, and m using the Statistical Analysis Software program (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To account for peptide-peptide interactions for a reversible adsorption process under equilibrium conditions, we use the concept that peptide-peptide interactions are minimized at very low solution concentrations, but then influence the isotherm shape (and thus Q) as the surface becomes crowded at higher values of Cb. The initial slope of the isotherm should thus not be influenced by peptide-peptide interactions. Accordingly, equation (2) was used (see reference 1 for derivation) to provide a relationship for the determination of ΔG°ads (kcal/mol) for peptide adsorption to a surface with minimal influence of peptide–peptide interactions based on experimentally determined parameters Q and K and the theoretically defined parameter δ (the thickness of the adsorbed layer of the peptide), where R (kcal/mol·K) is the ideal gas constant and T (K) is the absolute temperature.

| (2) |

The parameter δ is determined by assuming that its value is equal to twice the average outer radius of the peptide in solution with the peptide represented as being spherical in shape. Molecular dynamics simulations with similar peptides show this to be a very reasonable value for the adsorbed layer of this peptide.29, 33 Using theoretical values of δ, which are calculated for each peptide (see Table 1), combined with the values of Q and K, which are determined from the isotherm plots, ΔG°ads can be determined for each peptide–SAM system using equation (2). Although this procedure for the calculation of ΔG°ads involves this theoretical parameter, δ, it can be readily shown that the value of ΔG°ads is actually fairly insensitive to the values of δ1,3 thus providing a high level of robustness for the determination of ΔG°ads using this method.

Table 1.

Calculated values of δ for each peptide.

| Guest Residue (–X–) | –L– | –V– | –D– |

|---|---|---|---|

| δ (Å) | 12.1 | 12.0 | 12.1 |

II.d. AFM Methods

For the high–resolution force spectroscopy measurements in this study, we used a DimentionTM 3100 (di–Digital Instrument, Veeco Metrology Group, Santa Barbara, CA), and silicon nitride cantilevers (DNP–10 from Veeco Nanofabrication Center, Camarillo, CA). Imaging of AFM tips was performed with a Hitachi 4800–field emission gun scanning electron microscope (FEG–SEM). Tip radii, which are around 32 nm in our case, were measured by drawing a circle on the images such that an arc of the circle coincided with the curvature of the end of the tip.

II.d.1. Tip Chemistry

In order to link the host–guest peptide to the AFM tip, we used a heterobifunctional polyethylene-glycol tether (3.4–kDA pyridyldithio poly(ethyl-glycol) succinimidylpropionate (PDP–PEG–NHS), Creative PEGWorks, Winston Salem, NC). This molecule is composed of 77 ethylene glycol units with amine and thiol reactive end groups, thus enabling it to be used to covalently tether our peptide to silicon nitride tips. The tips were first cleaned by immersing them into a standard piranha solution, H2SO4/H2O2, 70:30 (v/v), for a couple seconds. The tips were then thoroughly rinsed with deionized water, followed again by an ethanol rinse and dried under nitrogen. To help drive off residual moisture, the cantilever tips were baked on a hotplate at 100 °C for approximately 30 minutes and then stored in cleaned glass petri dish. Immediately before functionalizing the tips, they were cleaned in chloroform for 10 minutes, washed with water and ethanol and dried under nitrogen. The tips were then amino–functionalized by incubating them overnight in a 55% (wt/vol) solution of ethanolamine chloride (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in dimethyl dulfoxide (DMSO) at room temperature in the presence of 0.3 nm molecular sieve beads and subsequently washed in DMSO and ethanol, dried under nitrogen gas. They were then immediately subjected the second step, which involved linking the PEG spacer molecule to the amine–functionalized tip. Binding of the PEG spacer to the amines on the tip surface was carried out at 3 mg/mL of PDP–PEG–NHS in a chloroform solution containing 0.5% triethylamine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for 2 hours. The tips were then washed in chloroform and dried under nitrogen gas. Our peptide sequences were then coupled to the PEG spacer via the free thiol group from both the PEG and the side chain of cysteine in our peptide sequence by incubating the tips for 1 hour in 5.0 mg/mL peptide solution. (peptide, TGTG–X–GTCT, in 1x phosphate buffered saline) (PBS; 140mM NaCl, pH=7.4; Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). Finally, the tips were then washed and stored in the same buffer in the cold room (4°C). Control groups were conducted with silicon nitrite tips tethered with a polyethylene glycol tether of the same length but functionalized at one end with NHS for binding to the amine groups of the AFM tip while the other end was capped with a hydroxyl group (3.4–kDa OH–PEG–NHS, Nanocs Inc, New York, NY). The effectiveness of this tip chemistry was developed and demonstrated by Hinterdorfer, et al. and Ebner, et al., by showing that it could be used to detect individual antibody- antigen recognition events by AFM.30–31 From their research work with similar tip chemistry, the surface density of protein attached to the probe tip was determined and calibrated by a sensitive high-resolution fluorescence imaging method and enzyme chip assay, which showed about 1,500–2,000 molecules per square micron. This molecular surface density translates to less than ten peptide molecules attached to AFM tip, which has an estimated surface area from Hertzian model (the simplest contact-mechanics model to use in AFM-based techniques)32 of ~ 6,000 nm2 in our case (surface area of hemi-spherical AFM tip end = 2πR2; R~32 nm).

II.d.2. Force Spectroscopy and Analysis

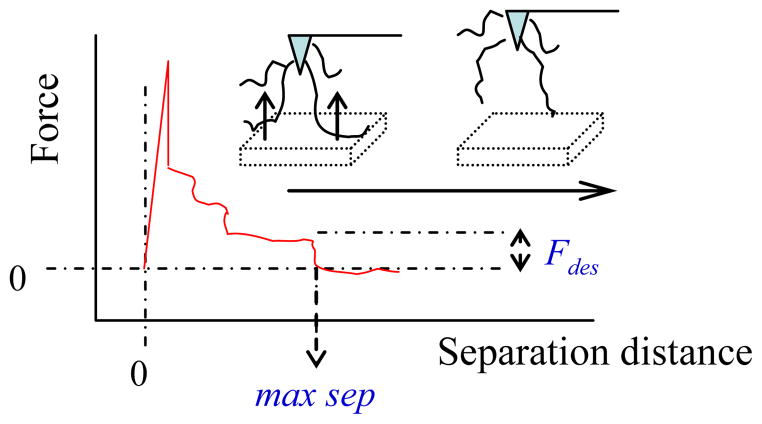

All force spectroscopy experiments were performed at room temperature in a fluid cell filled with droplets of PBS buffer (pH=7.4). The functionalized tip with the peptide was brought into contact with various SAM surfaces for 1 sec of surface delay and retracted at a constant vertical scanning speed of 0.1 μm/s. Tips with PEG–OH only were used as controls. The force–extension traces were obtained from the deflection piezo–path signal through Nanoscope software (Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA). The deflection signals (volts) were converted to force (Newton) through the use of the deflection sensitivity (40~100 nm/volts), spring constant of tips (0.058~0.065 N/m from the thermal–tune method33) and offset deflection. The peptide–surface interaction force, Fdes, was then recorded versus the tip–sample surface separation distance on approach (i.e., tip–probe advancing towards the sample surface at a constant rate) and retraction (i.e., tip–probe moving away from the sample surface at a constant rate). From the retraction force versus separation distance data, the unbinding force that was measured during the plateau region that ends right at the separation distance (max sep) that corresponds to the contour length of PEG spacer and the peptide sequence was taken as the force that characterizes the desorption of the peptide from the surface15–16 (as shown in Figure 2). All force analysis results were averaged from sixty experimental data scans collected for each peptide-SAM surface system (3 different site locations for each surface and 2 different SAM surface were used; ten repeating force curves were then collected from each spot; N=6). At each spot, the force-separation curves were chosen when the tips were laterally removed from the first contact spot to different locations on the surface under analysis to minimize the error offset coming from the layer compressibility of the target surface. We then wait until the force curve is stable (tip ramp size and start point is adjusted to just contact the surface with minimized repulsive region in the force curve). From this standardized protocol, we can obtain 60 reproducible force curves similar to the trace in Figure 2 with only variations in maximum separation distance and Fdes.

Figure 2.

Typical AFM force–separation curves. Fdes represents the measured pull–off force due to the desorption of peptide from adsorbent surface.

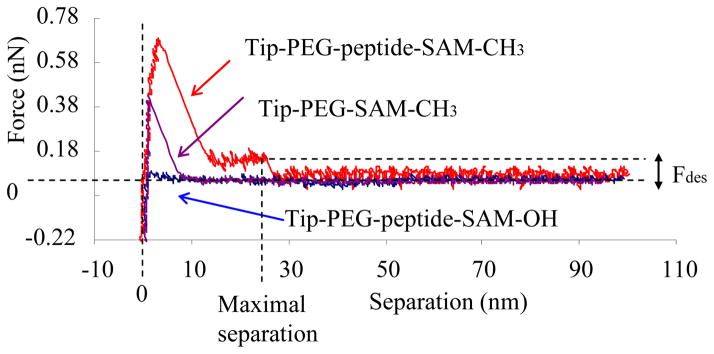

As shown in Figure 2, the larger force peak registered prior to this plateau region (usually < 10 nm separation distance) is caused by the interaction between the AFM tip material and the SAM surface.16, 18 The 3.4–kDa PEG consists of 77 units of ethylene-glycol (–OCH2CH2–) monomers with a contour length of 0.36 nm per monomer. Thus, the contour length of 3.4–kDa PEG in its fully extended conformation amounts to about 27.7 nm. The contour length of TGTG–X–GTCT, which consists of a total of 9 amino acids, with an approximate length of 0.37 nm per amino acid, amounts to a total length of approximately 3.3 nm, thus providing a total maximum separation distance of about 31.0 nm.

III. Results and Discussion

III.a. Surface Characterization

Table 2 presents the advancing water contact angle, layer thickness, and atomic composition for each of our surface chemistries. All of the values in Table 2 fall within the expected range for these types of surfaces.34–41

Table 2.

Atomic composition (by XPS), advancing contact angle (by deionized water in air) and layer thickness (by ellipsometry) results for surfaces with various functionalities. An asterisk (*) indicates negligible value for atomic composition results. The dimensions of the material surfaces other than the SAMs is provided in Section II.b.2. (Mean (± 95% confidence interval), N = 3.)

| Surface Moiety | C (%) | S (%) | N (%) | O (%) | F (%) | Contact Angle (°) | Thickness (Ǻ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAM–OH | 56.7 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.6) | * | 7.5 (0.2) | * | 15.5 (2.1) | 13.0 (1.0) |

| SAM–CH3 | 64.9 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.2) | * | * | * | 110.0 (3.0) | 11.0 (1.0) |

| SAM– (OCH2CH2)3OH | 54.8 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.1) | * | 13.2(0.6) | * | 32.0 (3.3) | 19.0 (3.0) |

| SAM–NH2 | 54.0 (0.9) | 2.0 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.3) | 3.3 (0.3) | * | 47.6 (1.8) | 14.7 (2.5) |

| SAM–NHCOCH3 | 48.6 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.1) | 4.0 (0.1) | 6.0 (0.7) | * | 48.0 (1.5) | 17.0 (2.0) |

| SAM–OCH2CF3 | 44.1 (2.0) | 1.7 (0.2) | * | 6.2 (1.1) | 13.0 (0.5) | 90.5 (0.8) | 16.1 (4.4) |

| Spin–coated PMMA | 67.2 (3.0) | * | * | 32.8 (1.2) | * | 70 (2.3) | 100 (10) |

| PTFE | 34.0 (1.5) | * | * | * | 66 (1.5) | 107 (2.5) | -- |

| Acrylite@AR** | 40.0 (0.4) | * | * | 42.0 (0.2) | * | 78 (3.4) | -- |

| Nylon 6/6 | 74.6 (0.7) | -- | 10.9 (0.3) | 14.5 (0.5) | -- | 63 (3.2) | -- |

| Glass slide** | 12.1 (0.5) | * | * | 61 (0.6) | * | 13 (3.0) | -- |

| Titanium** | 19.6 (1.0) | * | * | 54 (1.0) | * | 37 (5.2) | -- |

Acrylite@ AR represents PMMA sheet with surface modification which was found to contain Si (18.0±0.2% by XPS; not shown in the table) to increase surface hardness for abrasion resistant purposes.42–43 Glass also contains Zn (<1%), Na (<1%), K (<1%). Si (24.4±0.9%) and the titanium surface, which is actually TiO2, and contains Ti (23.3±0.5 %;) in atomic composition by XPS (not shown). The presence of carbon originated from surface contamination since the samples were exposed to air after cleaning processing. This is typical for adventitious, unavoidable hydrocarbon impurities, adsorbing spontaneously from ambient air onto the glass and titanium surface44–45.

The XPS results for the SAMs show that the surfaces contain the expected elemental composition with minimal levels of contamination, and the thicknesses indicate that each SAM surface is composed of a complete monolayer of the respective alkanethiol as opposed to multi–layers. These results thus indicate that the SAM surfaces used in this study were of high quality and appropriately represented the intended surface chemistries for our peptide adsorption experiments. Also, the contact angles for all of the surfaces are within expected values.

III.b. Comparison of Experimentally Measured ΔG°ads by SPR Between TGTG–X–GTCT and the Sequence TGTG–X–GTGT (X= Valine, Aspartic Acid and Leucine) on Different SAM Surfaces

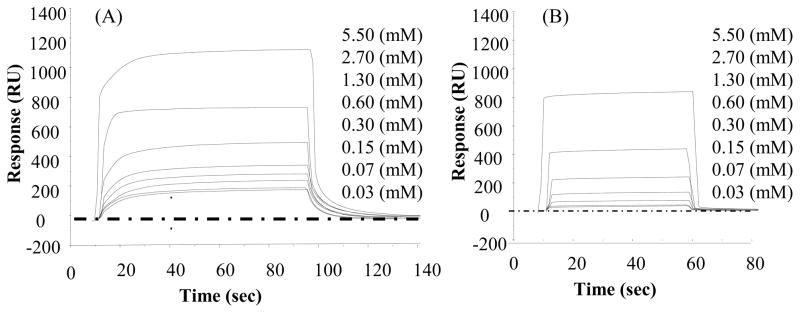

Adsorption isotherms for the peptide–SAM systems used in this research were generated from the raw SPR experimental data by plotting the changes in RU vs. peptide solution concentration as described in our previous work.1, 3 Examples of the raw SPR data (RU vs. time) and the corresponding isotherms (RU vs. solution concentration) for the TGTG-X-GTCT peptides are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. Values of the parameters Q, K, and m were then determined by fitting equation (1) to each of the data plots by non–linear regression using SAS. These parameters were then used to calculate ΔG°ads for each peptide–SAM system from equation (2) for comparison with the adsorption data for the TGTG-X-GTGT peptides, which were reported in our previous publication.3 The resulting values for Q, K, m and ΔG°ads values for both of the TGTG–X–GTGT and TGTG–X–GTCT peptides adsorbed on each of the six SAM surfaces are provided in supporting information.

Figure 3.

Response curves (SPR signal (RU) vs. time for TGTG–L–GTCT on (A) SAM–CH3 and (B) SAM–OH surface. (Not all of the concentration curves are listed for clarity sake because some of the low concentration curves overlap one another and are thus not separately distinguishable).

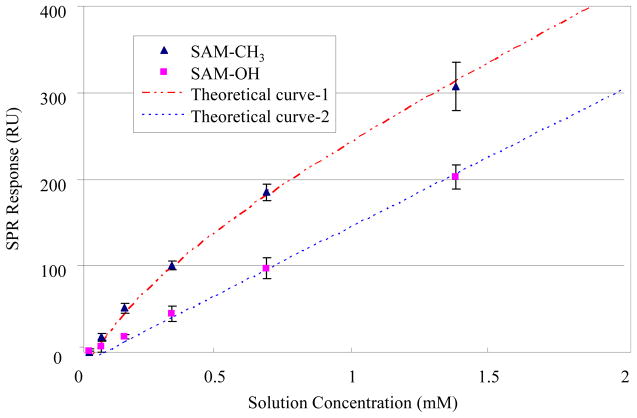

Figure 4.

Corresponding adsorption isotherm for TGTG–L–GTCT on both of SAM–CH3 surfaces (Δ presents experimental data which is fitted by equation (1): Theoretical curve-1, upper dotted line: Q=180 (RU), K=1800 (unitless) and m=148000 (RU/M)) and SAM–OH (□ presents experimental data which is fitted by equation (1): Theoretical curve-2, lower dotted line: Q=0.16 (RU), K=36 (unitless) and m=137000 (RU/M)). Note that the adsorption response plotted on the y–axis includes bulk–shift effects, which are linearly related to solution concentration. (Error bar represents 95% C.I., N = 6.)

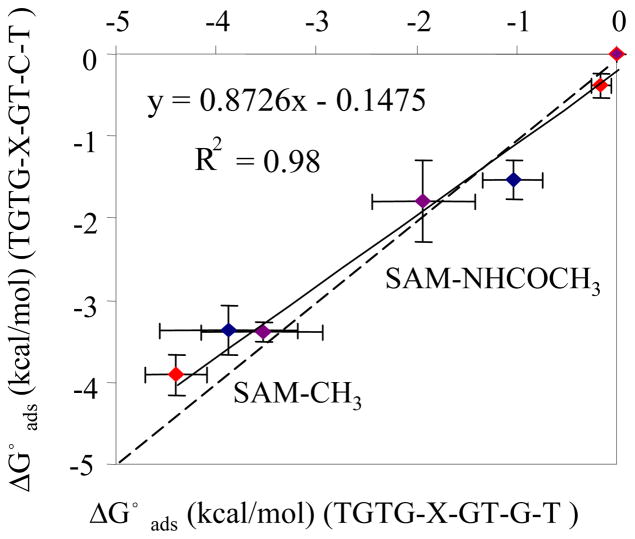

The calculated ΔG°ads values for the TGTG-X-GTGT peptide from the SPR studies are plotted against the ΔG°ads values for the TGTG-X-GTCT peptide for the three SAM surfaces in Figure 5. Two lines are indicated in this figure: a solid line that represents the best fit linear regression line (R2=0.98) comparing the two sets of data and a dashed line that indicates what the regression line should be for perfect agreement between these two data sets with R 2=1.0. A Student’s t–test analysis based on the 9 peptide-SAM surface combinations tested (3 measurements for each), at the 5% level of significance (α = 0.05) comparing these lines does not indicate a significant difference between their slope (p value = 0.089) or their y-axis intercept (p value = 0.27). Thus both of the R square values of these two lines and t-test results indicate that this amino acid substitution has negligible effect on the adsorption behavior of this peptide sequence design, thus supporting that the TGTG-X-GTCT can be used in the AFM studies as an equivalent model of the TGTG-X-GTGT peptide that has previously been extensively characterized by SPR. This conclusion is further supported by the fact that in an AFM experiment the TGTG-X-GTCT peptide is tethered to the AFM tip by the cysteine amino acid residue, thus minimizing its likelihood of contributing strongly to the peptide’s adsorption behavior during an AFM test. The results shown in Figure 5 were not unexpected. Although cysteine has more complex side group than glycine (i.e., –CH2SH vs. H, respectively), both amino acids are generally characterized as having neutral hydrophilic character. They also have similar hydrophobicity based on Wolfenden, et al.’s46 and Kyte and Doolittle’s hydrophobicity scales,47 which have been generally shown to reflect the adsorption behavior of individual amino acid residues.1, 48–50

Figure 5.

Comparison of experimentally measured ΔG°ads (kcal/mol) by SPR between TGTG–X–GTCT and the sequence TGTG–X–GTGT. X= valine (red), aspartic acid (purple) and leucine (blue) on different SAMs. (Error bar: 95% C.I., N = 3). Solid line shows the linier correlation between new and old peptide sequence on the same SAM surfaces; dashed line presents the theoretical relationship if there were no difference in the adsorption behavior between these two peptide sequences on SAMs.

III.c. AFM Desorption Force Data Analysis

For the analysis of AFM force measurements, Figure 2 shows a typical force–distance curve which can be roughly separated into three separate regions: At low separations, there is strong tip–surface interaction, which may mask the desorption event of peptides, especially on a hydrophobic surface. Continuous desorption of successive chain segments, which comes from the multiple polymer chain–surface interactions, is reflected by a stepwise plateau of constant force in the middle separation region. 21 Complete desorption of the tethered peptides from the surface results in a sudden drop of the force to zero (Fdes) when the tethered peptide contour length is reached for all peptides and the final peptides detach from the surface. Examples of the force curve (force vs. separation) are presented in Figure 6. As shown, the desorption force to pull TGTG–V–GTCT from the SAM–CH3 surface can be measured directly from the top-most (red) force curve with comparable separation distance (25 ± 5.5 nm) (mean ± 95% confidence interval, N = 6) to the contour length of our peptide–PEG assembling (~31.0 nm). A control AFM experiment was carried out with the AFM tip being functionalized with PEG only (without peptide attached) on this same SAM–CH3 surface. The corresponding force–separation curve (middle, purple curve) only shows one force peak within a short separation distance (<10 nm), which is associated with the probe tip-surface response, with no Fdes observed thereafter due to the lack of an adsorbing peptide for this system.

Figure 6.

AFM force–separation curves recorded during adsorption–desorption of TGTG–V–GTCT that are covalently attached to an AFM tip on an adsorbent surface. Fdes represents the measured pull–off force due to desorption of the peptide from the adsorbent surface. The upper (red) curve represents the peptide on the SAM–CH3 surface, the bottom (blue) curve represents the peptide on the SAM–OH surface, and the middle (purple) curve represents a control group with the AFM tip without the peptide (only covered with PEG) on a SAM–CH3 surface.

Comparison of the Fdes values (mean ± 95% confidence interval, N = 6) for TGTG–V–GTCT on a hydrophilic SAM–OH surface vs. a SAM–CH3 surface resulted in Fdes < 0.02 nN (SAM-OH, lowest blue curve in Figure 6) and Fdes = 0.107±0.015 nN (SAM-CH3, top red curve in Figure 6), respectively. As shown, the hydrophobic SAM–CH3 strongly adsorbed the TGTG–V–GTCT peptide with the Fdes value on this surface being significantly higher than on the SAM–OH surface (p < 0.001), thus demonstrating that this proposed method is sufficiently sensitive to determine the Fdes with significant differences for peptides adsorbed on surfaces with extremely different hydrophobicity. The resulting values from force–separation curves for Fdes and the maximal separation distances corresponding to other peptide–SAM systems are presented in Figures 7–9, with values and distribution plots from the complete data set presented in the supporting information.

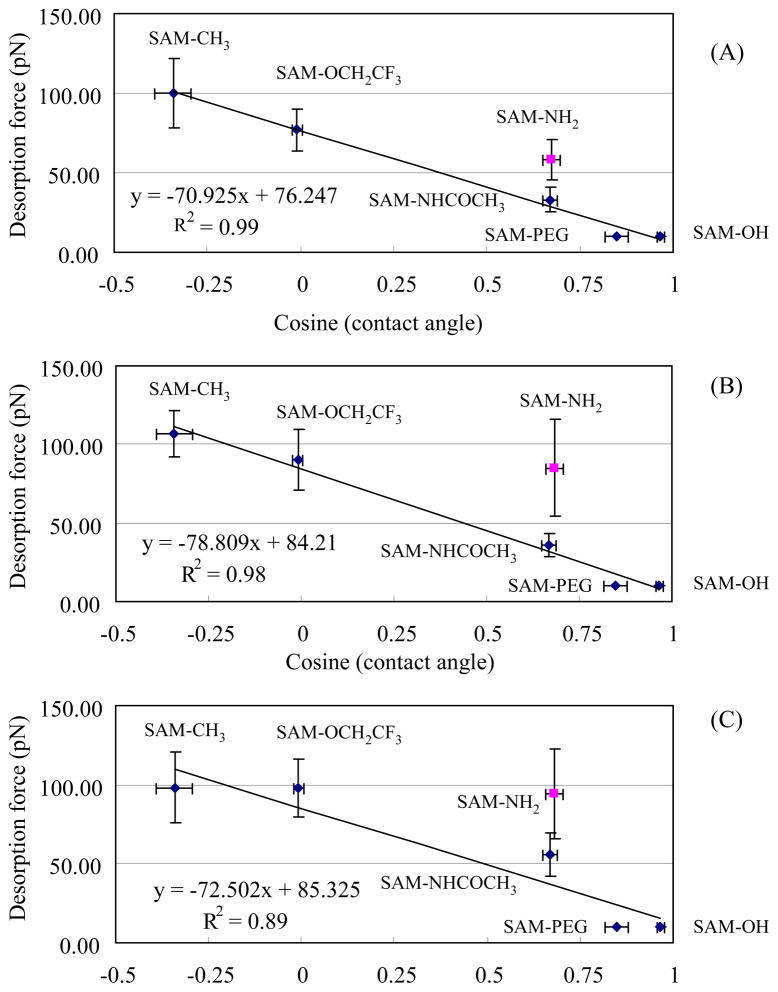

Figure 7.

Desorption force vs. cosine (contact angle) for TGTG–X–GTCT (X = (A) L, (B) V, and (C) D) on SAM surfaces with various functionalities. The trend lines show the linear regression for the non–charged SAM surfaces (i.e., excluding the SAM–NH2 surface, pK=6.5,51 which presents positive charged surface in PBS pH=7.4). The error bar represents the 95% C.I. with N = 6.

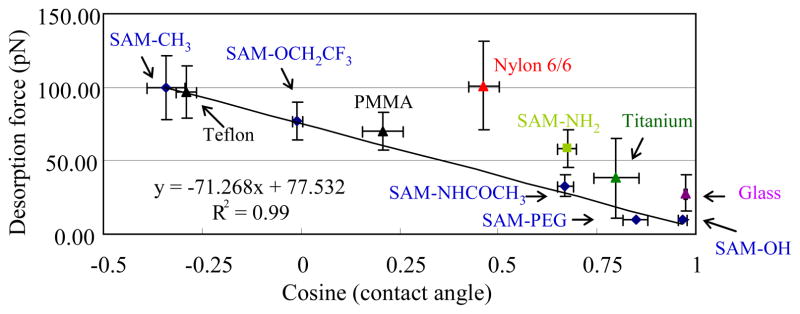

Figure 9.

Desorption force vs. cosine of the advancing water contact angle for TGTG–L–GTCT on SAM surfaces with various functionalities and bulk material surfaces. The trend line shows the linear regression for the non–charged surfaces (i.e., excluding Nylon 6/6 and the surfaces expected to have significant surface charged density: SAM–NH2 surface, pK=6.5,51 which presents positive charged surface in PBS pH=7.4, and titanium and glass, which are expected to be negatively charged due to the outmost oxidized layer at pH=7.4.60–61). The error bar represents the 95% C.I. with N = 6. The PMMA in this figure represents abrasion resistant PMMA.

III.d. Correlation between Peptide Desorption Force and Surface Hydrophobicity

Figure 7 presents a plot of the Fdes values for TGTG–X–GTCT (X=L, V and D) on SAM surfaces versus the respective cosine of the advancing water contact angle values for each SAMs (contact angle values are presented in Table 2). The cosine of contact angle values here can be related to the surface energy of the displacement of water at the surface with the adsorbed peptide monolayer.36

As clearly indicated in Figure 7, there is a high correlation between the Fdes values measured by our standard AFM method and the cosine of the advancing water contact angle of the surface for the non–charged surfaces. These results are similar to our previous findings from SPR3 that there is a general relationship holding for each of the neutrally charged SAM surfaces, with peptide adsorption affinity increasing (i.e., ΔG°ads gets more negative) in a manner that strongly correlates in a linear manner with the hydrophobicity of the SAM surfaces over the full range of contact angles. For the charged SAM-NH2 surface (pK = 6.551), there is the strength of adsorption that is substantially higher than the correlation line for the non-charged surfaces, reflecting the additional contribution to adhesion provided by electrostatic interactions between the peptides and this surface. These results clearly show that the Fdes values determined by our standardized AFM method provide a very similar general relationship to the cosine of the contact angle as the values of ΔG°ads determined by SPR3 for this set of SAM surfaces. This suggests that a close relationship exists between these two independent methods of measuring peptide adsorption and supports our hypothesis that Fdes is strongly correlated to ΔG°ads values determined by SPR, and thus should enable Fdes to be used to determine effective values of ΔG°ads for surfaces that are not readily amenable for use with SPR. In addition to this similarity, it is also important to note that both of these methods reveal that the water contact angle to present surface hydrophobicity itself does not completely determine adsorption behavior, with specific interactions between the functional groups of the peptide and the SAM surfaces playing a significant role, especially when charged surfaces are involved. Thus the contact angle method alone does not provide a reliable means of directly gauging protein adsorption study and biocompatibility analysis.

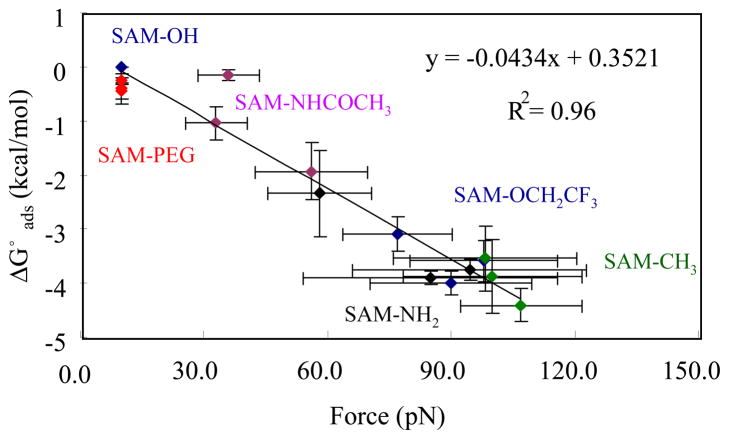

III.e. Correlation between Desorption Force Measured by AFM and ΔG°ads by SPR for Peptide–Surface Interactions

Figure 8 represents the results from the set of AFM studies that were conducted for the series of similar peptide–SAM surface systems with the benchmark values of ΔG°ads determined by SPR3 plotted against the corresponding AFM pull–off force (Fdes) measured in this research. As shown, the averaged AFM desorption force results from three different types of the host–guest peptides with an amino acid sequence of TGTG–X–GTCT (X = leucine, aspartic acid, and valine) on a set of six different SAM surfaces (SAM–OH, –CH3, –NH2, –NHCOCH3, –OCH2CF3, and –(OCH2CH2)3OH) are linearly related to the ΔG°ads results obtained by SPR, with a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.96. This linear correlation of the AFM measured desorption force with ΔG°ads suggests that this standardized AFM method should be able to be extended to estimate ΔG°ads for peptide–surface systems that are not amenable for evaluation by SPR.

Figure 8.

Correlation between ΔG°ads by SPR and desorption force by AFM for an equivalent set of peptide–SAM systems. Mid–chain amino acid (X) = leucine (L), aspartic acid (D), and valine (V) in PBS; pH=7.4. (Error bar represents 95% C.I.; N = 6)

III.f. Force Measurements to Estimate the Adsorption Free Energy for Surfaces that are not Readily Amenable for Evaluation by SPR

The final aim of this research was to apply the standardized AFM methods developed under the previous sections to estimate the values of ΔG°ads for peptide adsorption to materials that are not amenable to being studied using SPR. The materials tested were polymer sheets (abrasion resistant poly(methyl methacrylate) (AR-PMMA), Nylon 6/6, and Teflon), a metal plate (titanium), and a glass surface. The correlation equation shown in Figure 6–8 was used to calculate the effective ΔG°ads values for peptide adsorption on these new types of material surfaces from the corresponding measured values of Fdes. Accordingly, our standardized AFM method was applied to measure the Fdes for a TGTG–L–GTCT peptide on each of these surfaces. The results of these studies (Fdes, Max Sep, and ΔG°ads) are presented in Table 3 with corresponding distribution plots in support information.

Table 3.

Desorption force, maximum separation distance, and estimation for TGTG–L–GTCT on selected surfaces in PBS; pH=7.4., Mean (± 95% confidence interval for Fdes and sep; and ± 95% prediction interval for estimated ), N = 6. is estimated from the simple linear correlation derived from data in Figure 6–8 with corresponding prediction interval.52–53 Max sep represents maximal separation distance (nm). For comparison sake, mean value (± 95% confidence interval) for TGTG-V-GTGT on spin–coated PMMA film determined by SPR method also is listed here.

| Name | Fdes (pN) | Max sep (nm) | ΔGoads (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teflon | 97 (18) | 32 (4) | −3.85 (0.83) |

| Nylon 6/6 | 101 (30) | 35 (4) | −4.03 (0.84) |

| Glass Slide | 28 (12) | 36 (5) | −0.86 (0.82) |

| Titanium | 38 (27) | 30 (5) | −1.30 (0.81) |

| Abrasion resistant PMMA | 70 (13) | 30 (5) | −2.68 (0.81) |

| Spin-coated PMMA | −2.44 (0.50) |

As shown in Table 3, the Max sep values for each peptide-surface were very close to the theoretical value of 31.0 nm, thus supporting the validity of the test results, and ΔG°ads values were able to be estimated for each material from the measured Fdes values. Considering the data presented in Table 3, we would also like to note an experimental observation that was unique to the Nylon 6/6 surface, which gave the highest Fdes value. For all of these surfaces, except Nylon 6/6, the AFM trace provided a very distinct force signal when the probe tip contacted the solid material surface. This was very different for the Nylon 6/6, however, in which case contact with the surface was found to be much more indistinct, which we believe reflected that the chains on the surface of the Nylon 6/6 were in a swollen, somewhat hydrogel-like state due to their relatively high degree of hydrophilicity compared to the other surfaces.54–56

Our initial approach to directly validate the estimated ΔG°ads values for these selected surfaces by existing techniques such as isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)57 or by the area under force plateau58 are limited by the assumptions or the practical difficulties involved. For example, in ITC, the material may need to be in bead or particle form to increase the surface area. However, the bead or particle variants of inorganic crystalline materials (i.e., metals and ceramics) will likely involve unknown differences in the distribution of the exposed crystalline faces, thereby making it difficult to directly compare the peptide adsorption data on flat surfaces with that on a particulate. Additionally, with relatively hydrophobic polymers in aqueous solution, surfactants are commonly used to prevent particle aggregation (e.g., HDPE59), which will influence the peptide adsorptive behavior on the surfaces, thus making ITC unsuitable for measuring the desired thermodynamic properties for these types of materials. In AFM, although the free energies of adsorption could be estimated directly from the area under the velocity-independent force plateau, this method only provides a valid method of determining values of free energy per mole of adsorbed peptide if the number of adsorbed peptides is known. In our case this is not known, thus preventing this approach from being applied.

Although no other feasible methods that can be used to directly compare the validity of these ΔG°ads values for these surfaces, we can evaluate the reasonableness of these data by plotting the estimated Fdes values to the cosine of the advancing water contact angle of these surfaces along with the SAM surfaces as an additional check on the validity of these results. The results of these comparisons are presented in Figure 9.

As shown in Figure 9, the relationship between the cosine of the advancing water contact angle and Fdes for this set of additional material surfaces agrees extremely well with the data for the noncharged SAM surfaces except for Nylon 6/6, which is clearly not falling into the trend. Similar to what is shown in Figure 7, surfaces that can be expected to have substantial surface charge density (e.g., glass, titanium, SAM-NH2) result in an additional degree of surface attraction, resulting in a higher force of desorption, compared to the noncharged surfaces, in a manner that is very similar to what we have observed from our SPR results3. We speculate that the higher desorption force for Nylon 6/6 than expected from its contact angle is attributed to the swollen state of the Nylon 6/6 chains at the surface and leading to a condition where the tethered peptides were able to partially entangle with the hydrated Nylon 6/6 chains, leading to a distinctly higher desorption force.54–56

V. Conclusions

In this research work, our previous SPR results were correlated with standardize AFM methods that we developed to measure peptide–surface desorption forces for a similar set of peptide–SAM surface systems. The desorption forces obtained from AFM studies were found to strongly correlate in a linear manner with the ΔG°ads values measured from SPR as reported in our previous work, thus providing a means to estimate ΔGoads for peptide–surface systems that are not amenable to the test by SPR. The developed AFM method and its correlation with values of ΔG°ads were then applied to estimate ΔG°ads for peptide–surface interactions for a set of five material surfaces that were not amenable for analysis using SPR. The peptide desorption forces measured by AFM for both the SAM surfaces and the new set of non–charged material surfaces (excluding Nylon 6/6) were also shown to correlate strongly with the cosine of the advancing water contact angle for both the SAM surfaces and the bulk materials surfaces studied, with surfaces presenting charged functional groups resulting in an additional contributions to the desorption force that are not reflected in the cosine of the contact angle. The additional desorption force for the Nylon 6/6 surface is believed to be due to the swelling of the polymer chains at the surface of the material leading to increased interactions with the tethered peptides over simple surface adsorption. The strong correlation between peptide desorption force and the cosine of the advancing water contact angle is proposed as a means of qualitatively assessing the reasonableness of the AFM desorption force results for non–charged surfaces prior to using the data to estimate ΔG°ads for a given peptide–surface system, with this relationship expected to underestimate the desorption force for materials with charged functional groups on the surface or relatively hydrophilic polymers.

These methods provide a means of overcoming the limitations of SPR for the determination of values of ΔG°ads, which requires the ability to form nanothick films of the material over biosensor surfaces. This method thus provides the capability to greatly expand the benchmark data set for peptide-surface interactions to include a much broader range of materials surfaces. The developed methodology can be used to provide important thermodynamic insights into the fundamental amino acid–surface interactions that govern protein–surface interactions as well as fundamental data that is essential for the evaluation, modification, and validation of empirical force field parameters that are needed to enable protein adsorption behavior to be accurately represented by molecular simulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge NIH for funding support for this research (NIBIB grant # R01 EB006163). We also would like to thank Dr. James E. Harriss of Clemson University for assistance with the various aspects of SPR biosensor chip fabrication for these studies; Dr. Matthew Becker of Polymer Division–Biomaterial Group, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Gaitherburg, MD (presently Associate Professor of Polymer Science, University of Akron) for the assistance with the spin–coated PMMA films on gold chip; and Ms. Megan Grobman, Dr. Lara Gamble, and Dr. David Castner of NESAC/BIO at the University of Washington for assistance with surface characterization with XPS under the funding support by NIBIB (grant # EB002027).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. This supporting information contains (i) the data sheets of the parameters Q, K, and m determined by fitting equation (1) to each of our peptide–SAM systems plots, and (ii) the resulting values from force–separation curves by AFM for Fdes and maximal separation distance corresponding to peptide–SAM systems presented.

References

- 1.Wei Y, Latour RA. Determination of the adsorption free energy for peptide-surface interactions by SPR spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2008;24(13):6721–9. doi: 10.1021/la8005772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh N, Husson SM. Adsorption thermodynamics of short-chain peptides on charged and uncharged nanothin polymer films. Langmuir. 2006;22(20):8443–51. doi: 10.1021/la0533765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei Y, Latour RA. Benchmark Experimental Data Set and Assessment of Adsorption Free Energy for Peptide Surface Interactions. Langmuir. 2009;25(10):5637–5646. doi: 10.1021/la8042186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seker UOS, Wilson B, Sahin D, Tamerler C, Sarikaya M. Quantitative Affinity of Genetically Engineered Repeating Polypeptides to Inorganic Surfaces. Biomacromolecules. 2008;10(2):250–257. doi: 10.1021/bm8009895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luk Y-Y, Kato M, Mrksich M. Self-Assembled Monolayers of Alkanethiolates Presenting Mannitol Groups Are Inert to Protein Adsorption and Cell Attachment. Langmuir. 2000;16(24):9604–9608. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matharu Z, Bandodkar AJ, Sumana G, Solanki PR, Ekanayake EMIM, Kaneto K, Gupta V, Malhotra BD. Low Density Lipoprotein Detection Based on Antibody Immobilized Self-Assembled Monolayer: Investigations of Kinetic and Thermodynamic Properties. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2009;113(43):14405–14412. doi: 10.1021/jp903661r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vellore NA, Yancey JA, Collier G, Latour RA, Stuart SJ. Assessment of the Transferability of a Protein Force Field for the Simulation of Peptide-Surface Interactions. Langmuir. 2010;26(10):7396–7404. doi: 10.1021/la904415d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allison DP, Hinterdorfer P, Han W. Biomolecular force measurements and the atomic force microscope. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2002;13(1):47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lal R, John SA. Biological applications of atomic force microscopy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1994;266(1):C1–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C-K, Wang Y-M, Huang L-S, Lin S. Atomic force microscopy: Determination of unbinding force, off rate and energy barrier for protein-ligand interaction. Micron. 2007;38(5):446–461. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller DJ, Dufrene YF. Atomic force microscopy as a multifunctional molecular toolbox in nanobiotechnology. Nat Nano. 2008;3(5):261–269. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willemsen OH, Snel MM, Cambi A, Greve J, De Grooth BG, Figdor CG. Biomolecular interactions measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J. 2000;79(6):3267–81. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76559-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchette CD, Loui A, Ratto TV. Tip Functionalization: Applications to Chemical Force Spectroscopy. Handbook of Molecular Force Spectroscopy. 2008:185–203. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hards A, Zhou C, Seitz M, Brauchle C, Zumbusch A. Simultaneous AFM manipulation and fluorescence imaging of single DNA strands. Chemphyschem. 2005;6(3):534–40. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horinek D, Serr A, Bonthuis DJ, Bostrom M, Kunz W, Netz RR. Molecular hydrophobic attraction and ion-specific effects studied by molecular dynamics. Langmuir. 2008;24(4):1271–83. doi: 10.1021/la702485r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horinek D, Serr A, Geisler M, Pirzer T, Slotta U, Lud SQ, Garrido JA, Scheibel T, Hugel T, Netz RR. Peptide adsorption on a hydrophobic surface results from an interplay of solvation, surface, and intrapeptide forces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(8):2842–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707879105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamruzzahan ASM, Ebner A, Wildling L, Kienberger F, Riener CK, Hahn CD, Pollheimer PD, Winklehner P, Holzl M, Lackner B, Schorkl DM, Hinterdorfer P, Gruber HJ. Antibody Linking to Atomic Force Microscope Tips via Disulfide Bond Formation. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2006;17(6):1473–1481. doi: 10.1021/bc060252a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pirzer T, Geisler M, Scheibel T, Hugel T. Single molecule force measurements delineate salt, pH and surface effects on biopolymer adhesion. Phys Biol. 2009;6(2):25004. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/6/2/025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scherer A, Zhou C, Michaelis J, Brauchle C, Zumbusch A. Intermolecular Interactions of Polymer Molecules Determined by Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy. Macromolecules. 2005;38(23):9821–9825. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geisler M, Pirzer T, Ackerschott C, Lud S, Garrido J, Scheibel T, Hugel T. Hydrophobic and Hofmeister effects on the adhesion of spider silk proteins onto solid substrates: an AFM-based single-molecule study. Langmuir. 2008;24(4):1350–5. doi: 10.1021/la702341j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seitz M, Friedsam C, Jostl W, Hugel T, Gaub HE. Probing solid surfaces with single polymers. Chemphyschem. 2003;4(9):986–90. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200300760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chilkoti A, Boland T, Ratner BD, Stayton PS. The relationship between ligand-binding thermodynamics and protein-ligand interaction forces measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys J. 1995;69(5):2125–30. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80083-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandapativ RR, Mahalakshmi A, Moganty RR. Specific interactions between amino acid side chains - a partial molar volume study. Can J Chem. 1988;66:487–490. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Chen S, Li L, Jiang S. Improved Method for the Preparation of Carboxylic Acid and Amine Terminated Self-Assembled Monolayers of Alkanethiolates. Langmuir. 2005;21(7):2633–2636. doi: 10.1021/la046810w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vernekar VN, Latour RA. Adsorption thermodynamics of a mid-chain peptide residue on functionalized SAM surfaces using SPR. Mater Res Innovations. 2005;9:337–353. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Husson SM. Adsorption of dansylated amino acids on molecularly imprinted surfaces: a surface plasmon resonance study. Biosens Bioelectron. 2006;22(3):336–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seker UO, Wilson B, Dincer S, Kim IW, Oren EE, Evans JS, Tamerler C, Sarikaya M. Adsorption behavior of linear and cyclic genetically engineered platinum binding peptides. Langmuir. 2007;23(15):7895–900. doi: 10.1021/la700446g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.BIAtechnology Handbook. Biacore AB; Uppsala: 1998. pp. 4–1–4–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raut VP, Agashe MA, Stuart SJ, Latour RA. Molecular dynamics simulations of peptide-surface interactions. Langmuir. 2005;21(4):1629–39. doi: 10.1021/la047807f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebner A, Hinterdorfer P, Gruber HJ. Comparison of different aminofunctionalization strategies for attachment of single antibodies to AFM cantilevers. Ultramicroscopy. 2007;107(10–11):922–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinterdorfer P, Baumgartner W, Gruber HJ, Schilcher K, Schindler H. Detection and localization of individual antibody-antigen recognition events by atomic force microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(8):3477–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kopycinska-Müller M, Geiss RH, Hurley DC. Contact mechanics and tip shape in AFM-based nanomechanical measurements. Ultramicroscopy. 2006;106(6):466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulletin of statistics on world trade in engineering products. United Nations; New York: 1966. p. v. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sigal GB, Mrksich M, Whitesides GM. Effect of Surface Wettability on the Adsorption of Proteins and Detergents. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120(14):3464–3473. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silin VV, Weetall H, Vanderah DJ. SPR Studies of the Nonspecific Adsorption Kinetics of Human IgG and BSA on Gold Surfaces Modified by Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) J Colloid Interface Sci. 1997;185(1):94–103. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1996.4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siegel RR, Harder P, Dahint R, Grunze M, Josse F, Mrksich M, Whitesides GM. On-line detection of nonspecific protein adsorption at artificial surfaces. Anal Chem. 1997;69(16):3321–8. doi: 10.1021/ac970047b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mark SS, Sandhyarani N, Zhu C, Campagnolo C, Batt CA. Dendrimer-functionalized self-assembled monolayers as a surface plasmon resonance sensor surface. Langmuir. 2004;20(16):6808–17. doi: 10.1021/la0495276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toworfe GK, Composto RJ, Shapiro IM, Ducheyne P. Nucleation and growth of calcium phosphate on amine-, carboxyl- and hydroxyl-silane self-assembled monolayers. Biomaterials. 2006;27(4):631–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubois LH, Nuzzo RG. Synthesis, Structure, and Properties of Model Organic Surfaces. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 1992;43(1):437–463. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanahashi M, Matsuda T. Surface functional group dependence on apatite formation on self-assembled monolayers in a simulated body fluid. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;34(3):305–15. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19970305)34:3<305::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sethuraman A, Han M, Kane RS, Belfort G. Effect of Surface Wettability on the Adhesion of Proteins. Langmuir. 2004;20(18):7779–7788. doi: 10.1021/la049454q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee MS, Jo NJ. Coating of Methyltriethoxysilane—Modified Colloidal Silica on Polymer Substrates for Abrasion Resistance. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology. 2002;24(2):175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanglumlert W, Prasassarakich P, Supaphol P, Wongkasemjit S. Hard-coating materials for poly(methyl methacrylate) from glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane-modified silatrane via a sol-gel process. Surface and Coatings Technology. 2006;200(8):2784–2790. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serra J, González P, Liste S, Serra C, Chiussi S, León B, Pérez-Amor M, Ylänen HO, Hupa M. FTIR and XPS studies of bioactive silica based glasses. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 2003;332(1–3):20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winkelmann M, Gold J, Hauert R, Kasemo B, Spencer ND, Brunette DM, Textor M. Chemically patterned, metal oxide based surfaces produced by photolithographic techniques for studying protein- and cell-surface interactions I: Microfabrication and surface characterization. Biomaterials. 2003;24(7):1133–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolfenden R, Andersson L, Cullis PM, Southgate CCB. Affinities of amino acid side chains for solvent water. Biochemistry. 1981;20(4):849–855. doi: 10.1021/bi00507a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157(1):105–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiggins PM. Hydrophobic hydration, hydrophobic forces and protein folding. Physica A: Statistical and Theoretical Physics. 1997;238(1–4):113. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai YS, Lin FY, Chen WY, Lin CC. Isothermal titration microcalorimetric studies of the effect of salt concentrations in the interaction between proteins and hydrophobic adsorbents. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2002;197(1–3):111. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perkins TW, Mak DS, Root TW, Lightfoot EN. Protein retention in hydrophobic interaction chromatography: modeling variation with buffer ionic strength and column hydrophobicity. Journal of Chromatography A. 1997;766(1–2):1. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fears KP, Creager SE, Latour RA. Determination of the Surface pK of Carboxylic- and Amine-Terminated Alkanethiols Using Surface Plasmon Resonance Spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2008;24(3):837–843. doi: 10.1021/la701760s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allen TT. Introduction to engineering statistics and six sigma: statistical quality control and design of experiments and systems. 1. Springer; London: 2006. p. xxii.p. 529. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Montgomery DC, Runger GC, Hubele NF. Engineering statistics. 4. John Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2007. p. xxiii.p. 487. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giannotti MI, Vancso GJ. Interrogation of single synthetic polymer chains and polysaccharides by AFM-based force spectroscopy. Chemphyschem. 2007;8(16):2290–307. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200700175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hodges CS. Measuring forces with the AFM: polymeric surfaces in liquids. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2002;99(1):13–75. doi: 10.1016/s0001-8686(02)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saitta AM, Klein ML. First-Principles Study of Bond Rupture of Entangled Polymer Chains. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2000;104(10):2197–2200. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang H-M, Chen W-Y, Ruaan R-C. Microcalorimetric studies of the mechanism of interaction between designed peptides and hydrophobic adsorbents. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2003;263(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9797(03)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geisler M, Balzer BN, Hugel T. Polymer Adhesion at the Solid–Liquid Interface Probed by a Single–Molecule Force Sensor. Small. 2009;5(24):2864–2869. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zangi R, Berne BJ. Aggregation and Dispersion of Small Hydrophobic Particles in Aqueous Electrolyte Solutions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2006;110(45):22736–22741. doi: 10.1021/jp064475+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lori JA, Hanawa T. Characterization of adsorption of glycine on gold and titanium electrodes using electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance. Corrosion Science. 2001;43(11):2111–2120. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sabia R, Ukrainczyk L. Surface chemistry of SiO2 and TiO2-SiO2 glasses as determined by titration of soot particles. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 2000;277(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.