Abstract

Defects in excitation-contraction coupling have been reported in failing hearts, but little is known about the relationship between these defects and the development of heart failure (HF). We compared the early changes in intracellular Ca2+ cycling to those that underlie overt pump dysfunction and arrhythmogenesis found later in HF. Laser-scanning confocal microscopy was used to measure Ca2+ transients in myocytes of intact hearts in Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats and spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) at different ages. Early compensatory mechanisms include a positive inotropic effect in SHRs at 7.5–9 mo compared with 6 mo. Ca2+ transient duration increased at 9 mo in SHRs, indicating changes in Ca2+ reuptake during decompensation. Cell-to-cell variability in Ca2+ transient duration increased at 7.5 mo, decreased at 9 mo, and increased again at 22 mo (overt HF), indicating extensive intercellular variability in Ca2+ transient kinetics during disease progression. Vulnerability to intercellular concordant Ca2+ alternans increased at 9–22 mo in SHRs and was mirrored by a slowing in Ca2+ transient restitution, suggesting that repolarization alternans and the resulting repolarization gradients might promote reentrant arrhythmias early in disease development. Intercellular discordant and subcellular Ca2+ alternans increased as early as 7.5 mo in SHRs and may also promote arrhythmias during the compensated phase. The incidence of spontaneous and triggered Ca2+ waves was increased in SHRs at all ages, suggesting a higher likelihood of triggered arrhythmias in SHRs compared with WKY rats well before HF develops. Thus serious and progressive defects in Ca2+ cycling develop in SHRs long before symptoms of HF occur. Defective Ca2+ cycling develops early and affects a small number of myocytes, and this number grows with age and causes the transition from asymptomatic to overt HF. These defects may also underlie the progressive susceptibility to Ca2+ alternans and Ca2+ wave activity, thus increasing the propensity for arrhythmogenesis in HF.

Keywords: calcium alternans, calcium transients, excitation-contraction coupling, heart failure, spontaneously hypertensive rats

heart failure (HF) is a chronic maladaptive state in which perturbations of Ca2+ cycling occur concurrent with deteriorating cardiac function and increasing arrhythmogenesis (22). Cellular defects in cardiac excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling have been identified in failing hearts from human and animal models and contribute to mechanical and electrophysiological dysfunction (49). One particularly serious defect is a disruption in the T-tubule network (5) so that junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and ryanodine receptors (RYRs) that regulate Ca2+ release from the SR are isolated from the normal trigger supplied by L-type Ca2+ channels (LCCs). Activation occurs instead by diffusion from neighboring release units, a defect that was first identified in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) (45) but also found in mouse (35), human (34) and dog (5) hearts. The ensuing defective activation of “orphaned” RyRs (45) causes a poorly coordinated release of Ca2+ throughout the cell. In combination with a slowing of reuptake because of reduced activity of the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) (21), the result is a serious dysfunction in Ca2+ cycling.

In contrast to overt HF, there is little information on the progression of defects in Ca2+ cycling and E-C coupling and their electrophysiological implications during HF development. In the SHR model, early compensation in response to hypertension includes a period during which Ca2+ sparks are increased, suggesting an early positive inotropic response (44). However, the subsequent changes in Ca2+ cycling involved in the progression from compensated HF to the clinically apparent decompensated HF, both in animals and humans, are very poorly understood. Several studies have focused on active myocardial properties, fibrosis, Ca2+ sparks, and Ca2+ transients during the transition from hypertension to HF (46, 56). However, a comprehensive study of changes in Ca2+ cycling during the development of HF is lacking.

In addition, although previous aging studies have demonstrated negative inotropy in rodents and positive inotropic effects in sheep (15, 23, 25, 39, 58), there are few data regarding the Ca2+ handling properties at different stages throughout the aging process. Even fewer studies have compared Ca2+ cycling changes during normal aging to aging in HF animals. It is also important to note that all of these previous observations were made in isolated myocytes, with little information available about Ca2+ cycling at the cellular level in the intact heart.

The goal of this study was to investigate the early changes in intracellular Ca2+ cycling that occur in response to hypertension and before the development of overt HF in an intact rat heart model. These results from young animals were also compared with those obtained in old SHRs with overt HF similar to those reported by others (45). We tested the hypothesis that defects in intracellular Ca2+ cycling in HF are distinct, occur early (long before HF develops), and differ from those seen in normal aging. We chose to study the SHR model because hypertension occurs early (within 2 to 3 mo of age) and is maintained constant throughout life (12) and therefore mimics the clinical course of many patients who develop HF secondary to hypertension, making the SHR a particularly good model of the slow onset of hypertrophy and HF in response to hypertension. To investigate the cellular function in the intact heart in response to hypertension, we used laser-scanning confocal microscopy to measure intracellular Ca2+ cycling with sarcomere-level resolution in myocytes of whole hearts (1).

METHODS

All animal use protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Male SHRs and Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (80:8 mg/kg ip), and the heart was removed and placed on a Langendorff apparatus for retrograde perfusion with a modified Tyrode solution containing (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 17 NaHCO2, 0.5 MgCl2, 0.4 NaH2PO4, and 10 glucose and 2% bovine serum albumin (by weight), bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2 (pH 7.35). Four distinct age groups were studied: 6 mo (6–6.5 mo), 7.5 mo (7–8 mo), 9 mo (8.5–9.5 mo), and 22 mo (20–25 mo). The numbers were as follows (hearts/sites/myocytes): 6-mo WKY, 3/6/85; 6-mo SHR, 2/5/81; 7.5-mo WKY, 3/5/76; 7.5-mo SHR, 2/4/66; 9-mo WKY, 2/7/81; 9-mo SHR, 2/4/73; 22-mo WKY, 5/11/193; and 22-mo SHR, 6/13/212. Advanced stages of HF were demonstrated in the 22-mo population by high heart weight-to-body weight ratios (3.99 ± 0.19 mg/g in WKY rats compared with 8.88 ± 0.29 in SHRs, P < 0.001), fluid in the lungs, dyspnea, and greatly diminished activity levels in the SHRs. The heart was then placed in an experimental chamber on the stage of a Zeiss LSM510 laser-scanning confocal microscope. Temperature was maintained at 26 ± 1°C. Three successive additions of fluo-4 AM (10–15 μM diluted from an ethanol stock; Invitrogen) were made to the solution at 20-min intervals during recirculation, after which the heart was washed with normal solution for 10 min. Cytochalasin-D (50 μM dissolved in ethanol; Sigma) and blebbistatin (12 μM dissolved in ethanol; Sigma) were then added to the solution to prevent contraction, and recirculation was again initiated. The right atrium was crushed to slow the intrinsic heart rate. Hook platinum electrodes were inserted into the left ventricular apex so that basal pacing at a basic cycle length (BCL) of 700 ms could be interspersed with 10-s epochs of rapid pacing at different test cycle lengths (CLs).

Once dye loading was complete, a section of the left ventricular midepicardial surface was scanned to identify the sites with well-loaded myocytes. Fluo-4 was excited with 488-nm laser light from a 25-mW argon laser at ≤10% transmission, and fluorescence > 505 nm was collected via a long-pass filter. The scan line was then placed across the short axis of 10–25 myocytes, and pacing protocols were initiated. The characteristics of Ca2+ transients were recorded during both basal pacing (BCL = 700 ms) and rapid pacing. The rate sensitivity of Ca2+ transient alternans magnitude was measured as alternans ratio (53) (AR = 1 − small/large) at steady state (10 s) for each test BCL. Each epoch was followed by a 3-s pause before a return to basal pacing for 1 min before the next test train was initiated at a 10-ms shorter BCL. The effects of rapid pacing were tested in the range of BCL = 500–140 ms or until 2:1 block or tachycardia occurred. Ventricular tachycardia was defined as a train of at least five spontaneous beats following the test train. Details of these methods have been published elsewhere (1, 27, 48).

Confocal fluorescence images were measured using Zeiss and ImageJ software. Fluorescence intensities for each cell were cut from the original images, and intensity profiles were analyzed using MatLab and pCLAMP8 software. The SD of the mean for each parameter (35), also termed heterogeneity indexes (HIs) (48), was calculated to permit comparisons of the overall intercellular heterogeneity between the different sites. Gradient indexes (GIs) were calculated to compare cell-to-cell heterogeneity (or gradients between adjoining cells) and are defined as the SD of the difference between adjacent cells for each parameter. All results are expressed as means ± SE. Differences were analyzed by one-way and two-way ANOVA, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis. Results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Ca2+ transients during basal pacing.

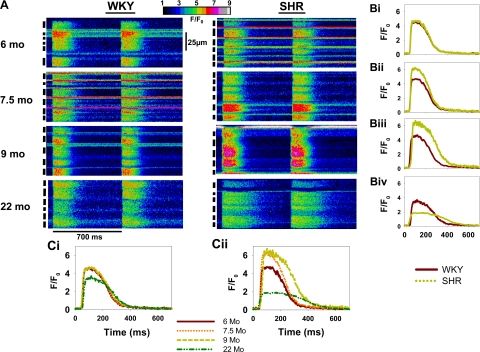

Figure 1 shows recordings of Ca2+ transients from each of the eight conditions studied during basal pacing: WKY (A, left) and SHR (A, right) hearts at 6, 7.5, 9, and 22 mo. All cells (black bars at left of each image) show simultaneous Ca2+ release during stimulation and subsequent decay as Ca2+ is removed from the cytoplasm (Fig. 1A). Figure 1B shows the average intensity profile for all WKY and SHR myocytes within the site, comparing WKY and SHRs at each time point. Figure 1C, i and ii, shows the intensity profiles of WKY and SHRs at all time points and reflects changes in Ca2+ cycling with age.

Fig. 1.

Line scan images comparing intracellular Ca2+ transients of intact Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) and spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) hearts. A: transverse recordings from multicellular sites of WKY (left) and SHR (right) hearts at 6, 7.5, 9, and 22 mo of age. Black bars at left indicate each cell. Two beats are shown at basal basic cycle length (BCL) = 700 ms. Intensity profiles of a single beat from a selected cell from each image are shown to the right of the line scan images and compare WKY and SHRs at the same age (B). C: superimposed intensity profiles at different ages.

Figure 1A shows changes in basal Ca2+ cycling that occur both in normal aging and in HF. Ca2+ transients in WKY and SHRs are similar in duration and amplitude at 6 mo and show little variability between myocytes. At 7.5 mo, the SHR heart demonstrated an overall positive inotropic effect but has a highly mixed population of Ca2+ transients in which some cells have increased amplitude and duration, whereas others are similar to the 6-mo animals, resulting in increased cell-to-cell variability. At 9 mo, most SHR cells have increased amplitude and duration but again exhibit less cell-to-cell variability. The Ca2+ transient duration is longer in the 22-mo SHR despite the decreased amplitude. Note also that the 22-mo WKY rat has longer Ca2+ transients than the younger WKY rats and lower intercellular variability in Ca2+ transient magnitude and duration.

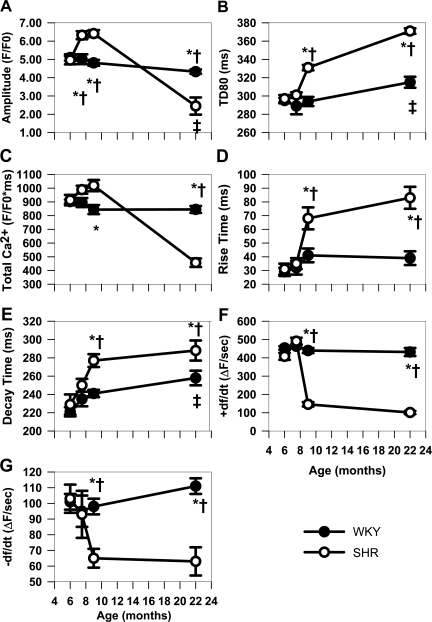

The time-dependent changes in Ca2+ transient characteristics during early development in WKY and SHR myocytes are summarized in Fig. 2. There were no differences between Ca2+ transients in SHRs and WKY rats at 6 mo (Fig. 1B,i). At 7.5 mo, the Ca2+ transients are similar in all characteristics except for the increased amplitude of the SHR myocytes. At 9 mo (Fig. 1B,iii), the increase in amplitude persists in the SHR myocytes, but there is now an increase in Ca2+ transient duration at 80% of recovery (TD80, Fig. 2B). Increased duration occurs as a result of both slower rising and falling phases (Fig. 2, D and E). Increased amplitude and duration result in an increased integral of Ca2+ release (Fig. 2C). Decreases in the maximal rate of Ca2+ release (+dF/dt, Fig. 2F) and maximal rate of decline (−dF/dt, Fig. 2G) are consistent with slower rise and decay times. In comparison, HF myocytes in 22-mo SHRs (Fig. 1B,iv) show smaller Ca2+ transient amplitudes than in WKY rats despite the increased duration (Fig. 2, B, D, and E), as is confirmed by the decreased Ca2+ transient integral (Fig. 2C). Both +dF/dt and −dF/dt were depressed in HF (Fig. 2, F and G).

Fig. 2.

Summary of characteristics of Ca2+ transients at basal pacing (BCL = 700 ms) for all groups. ±dF/dt, maximal rate of Ca2+ release and decline, respectively; TD80, Ca2+ transient duration at 80% of recovery. *P < 0.05 compared with WKY at the same age. †P < 0.05 compared with 6-mo SHR. ‡P < 0.05 compared with 6-mo WKY.

The normal aging process in WKY rats causes little change in Ca2+ transient amplitude and duration from 6 to 9 mo (Figs. 1C,i and 2). Only at 22 mo do WKY Ca2+ transients show decreased amplitude and increased duration (Fig. 2, A and B) compared with younger animals. This increased duration is due to the increased decay time at 22 mo in the absence of changes in the rise time and +dF/dt (Fig. 2, D and E). In contrast, SHRs show changes in Ca2+ cycling starting at 7.5 mo as an increase in amplitude (Figs. 1C,ii and 2A), whereas duration changes (TD80, rise and decay) occur starting at 9 mo (Fig. 2, B, D, and E).

Cell-to-cell variability of Ca2+ transients.

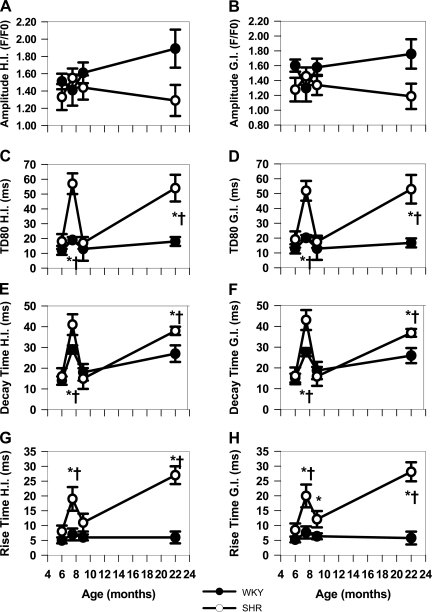

One of the most striking observations was increased cell-to-cell variability in Ca2+ transient characteristics within each recording site (Fig. 1A), particularly in Ca2+ transient duration. Figure 3, A, C, E, and G, summarizes the HI (48) for Ca2+ transient characteristics in WKY and SHR myocytes in each age group. HI compares intercellular heterogeneity for each parameter within a site (35). We found increased heterogeneity only in the characteristics related to duration (Fig. 3, C, E, and G) of SHR myocytes at 7.5 mo compared with both 6 and 9 mo with no changes in heterogeneity at any time during aging in WKY rats. A high variability in duration was also present in failing hearts (22-mo SHRs). These changes reflect the prolongation of Ca2+ transients that develops between 6 and 9 mo so that intercellular variability is greatest at 7.5 mo and the greatest uniformity occurs at 6 and 9 mo. Different processes affect E-C coupling in overt HF and will be discussed later.

Fig. 3.

WKY vs. SHRs heterogeneity indexes (HIs) and gradient indexes (GIs). Summary of HIs and GIs for basal Ca2+ transient characteristics as a function of age in WKY and SHRs. *P < 0.05 compared with WKY at the same age. †P < 0.05 compared with 6-mo SHR.

Further investigation of the source for intercellular variability is shown in measurements of the GIs shown in Fig. 3, B, D, F, and H, for amplitude and durational components of WKY and SHRs. GI is a measure of variability between adjoining cell pairs and is calculated as the SD of the differences in each parameter between each cell pair in a recording site. Once again, GI is greater for all three durational components of SHR myocytes at 7.5 mo and also in HF compared with WKY myocytes (Fig. 3, D, F, and H). Thus much of the intercellular variability within the sites for duration comes from the large heterogeneities that exist between adjoining cells.

Increased sensitivity to Ca2+ transient alternans development occurs early in SHRs.

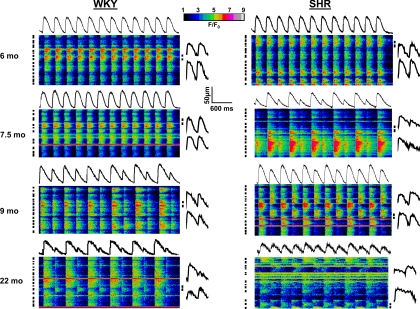

Figure 4 shows twelve consecutive beats at steady state during rapid pacing (BCL = 300 ms) in line scan images of sites from WKY and SHRs at 6, 7.5, 9, and 22 mo. The average intensity profiles of the site are shown above each image, and the profiles of two selected cells (black bars) are shown for the last two beats at the right of each image. Ca2+ transient amplitude, morphology, and duration are constant at 6 mo for both WKY and SHRs. At 7.5 mo, there is a small Ca2+ transient alternans in the WKY rat (AR = 0.13) and a large alternans in the SHR (AR = 0.54) at the same CL, although alternans phase is identical in all cells in each site (intercellular concordant alternans). At 9 mo, the WKY site shows increased Ca2+ transient alternans (AR = 0.46), but the SHR site, in addition to an increased overall cellular AR, now demonstrates intercellular discordant alternans where myocytes are phase mismatched and large Ca2+ transients in some cells occur while neighboring myocytes respond with small Ca2+ transients. Note that the overall intensity profile shows less Ca2+ transient alternans, as the average of simultaneous large-small and small-large cycles results in an overall site average Ca2+ transient alternans of intermediate magnitude. At 22 mo, both WKY and SHR sites display intercellular discordant alternans, with the WKY rat showing only one discordant cell (fifth from bottom), whereas the SHR shows ∼50% discordance.

Fig. 4.

Line scan recordings of intracellular Ca2+ transients in cells from intact WKY and SHR hearts during rapid pacing. Images from WKY (left) and SHRs (right) at each time point are shown. Average fluorescence intensity profiles for each cell are placed above the image. Images show 12 consecutive beats at 300-ms cycle length. Intensity profiles of 2 myocytes for the final 2 beats are shown to right of line scans.

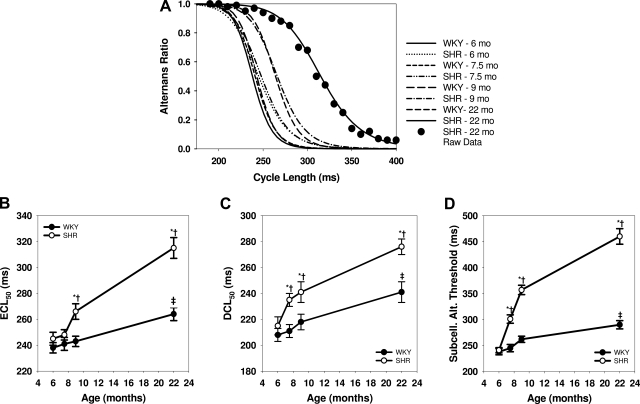

Figure 5A summarizes the rate sensitivity of AR for all conditions. The curves show fitted averages for all cells in each category (including original data points for all 22-mo SHR cells for comparison) and demonstrate that AR increases with heart rate. To quantify the rate sensitivity for Ca2+ transient alternans development, the estimated CL at 50% maximal alternans (ECL50) was calculated (1). The HF (22-mo SHR) myocytes are the most vulnerable of all groups to alternans and are therefore shifted farthest to the right in Fig. 5A and give the largest ECL50 values. Figure 5B shows increased vulnerability to alternans at both 9 and 22 mo in SHRs with no change between 6 and 7.5 mo. There were no changes in vulnerability to alternans in young WKY rats, although normal aging also increased alternans vulnerability, as shown by an increased ECL50 in the oldest WKY rats compared with younger WKY rats.

Fig. 5.

Heart failure and aging increase susceptibility to Ca2+ transient alternans. A: fitted sigmoidal curves of Ca2+ alternans ratio versus cycle length for all groups. Summary data points are shown on the 22-mo curve of SHRs, demonstrating a typical quality of fit. Curves are drawn for the mean of all myocytes in each group. B: estimated cycle length at 50% maximal concordant Ca2+ alternans (ECL50) for all data. C: cycle length at 50% maximal intercellular discordant Ca2+ alternans (DCL50) for all data. D: threshold cycle length at which subcellular Ca2+ alternans (Subcell Alt) threshold occurs for all groups. *P < 0.05 compared with WKY at the same age. †P < 0.05 compared with 6-mo SHR. ‡P < 0.05 compared with 6-mo WKY.

Intercellular discordant Ca2+ alternans was quantified by comparing the values of the CL at which 50% of maximal discordance (DCL50) is achieved. Note that DCL50 is the estimated CL at which 25% of cells are phase mismatched with the other 75%, since maximal discordance occurs when 50% of cells are out of phase. Figure 5C shows a plot of DCL50 for WKY and SHRs for each age group and shows more discordance in 7.5–22-mo SHRs compared with WKY rats. Intercellular discordant alternans also increases in 22-mo WKY rats compared with 6–9-mo WKY rats.

A third form of Ca2+ alternans, subcellular alternans, refers to Ca2+ alternans in which alternans in one cellular region is phase mismatched with other regions in the same cell (28). Figure 5D shows that the threshold for subcellular alternans is increased for SHRs at 7.5–22 mo over WKY rats. There is also an increased susceptibility to subcellular alternans with aging in the WKY group.

Another form of aberrant Ca2+ cycling behavior occurred rarely in WKY rats (Fig. 6A,i) but more commonly in SHRs. Both spontaneous (Fig. 6A,ii) and triggered Ca2+ waves (Fig. 6A,iii) occurred at a higher incidence at all ages in SHRs compared with WKY rats (Fig. 6B). Triggered Ca2+ waves are defined as Ca2+ waves that occur during pacing and are absent during quiescence, in contrast with spontaneous Ca2+ waves that occur only following pacing and during quiescence (49). These forms of Ca2+ cycling occur at all stages of disease development in SHRs compared with age-matched control WKY rats and are especially prevalent in HF, as we have reported previously (49).

Fig. 6.

Spontaneous and triggered Ca2+ waves in WKY and SHRs. A,i: Ca2+ transients activated by the last 3 stimulated beats (♦) (BCL = 280 ms) in a 22-mo WKY heart, followed by a 3-s pause when a spontaneous beat (◊) occurred. A,ii: a spontaneous wave (*) occurs in the second cell from top during the pause (22-mo SHR). A,iii: triggered waves during both basal and rapid pacing (arrows). B: summary of the incidence of spontaneous (Spont; B,i) and triggered (Trig; B,ii) waves in each experimental group. *P < 0.05 compared with WKY at the same age. †P < 0.05 compared with 6-mo SHR.

Altered restitution of SR Ca2+ release in early SHRs and aging.

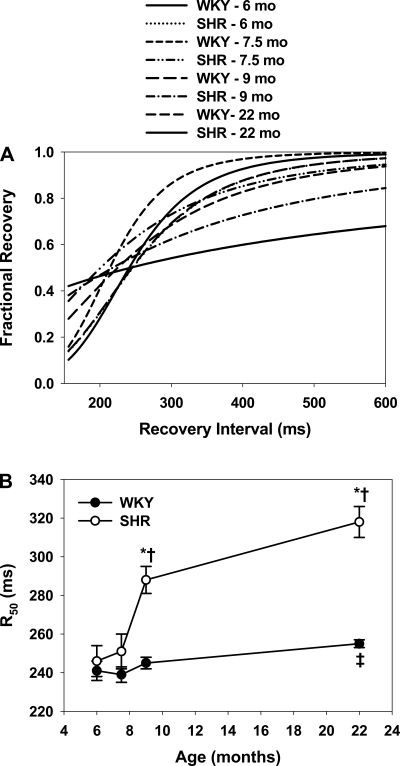

A major determinant of Ca2+ alternans is the rate of recovery of Ca2+ release from the SR during rapid stimulation (48). Figure 7A shows the averaged restitution of all WKY and SHR myocytes from 6–22 mo. Data from young WKY rats show a rapid recovery of SR release with an increasing interval, with nearly full recovery at ∼450 ms. Nearly identical results occurred in 6- and 7.5-mo SHRs, but the rate of restitution in SHRs is slowed at 9 mo and even more in HF where, in many instances, recovery was so slow that it was not possible to test short enough intervals without inducing ventricular tachycardia.

Fig. 7.

Rates of restitution of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in WKY and SHRs. A: average Ca2+ transient restitution curves for all groups. Curves are drawn for average of all myocytes. B: cycle length at 50% fractional recovery (R50) for all groups. *P < 0.05 compared with WKY at the same age. †P < 0.05 compared with 6-mo SHR. ‡P < 0.05 compared with 6-mo WKY.

Figure 7B summarizes this change in restitution by plotting the time of recovery of restitution for all the groups. R50 is the calculated CL at which fractional recovery of the sigmoid fit achieved 0.5. SHR myocytes showed slower restitution compared with WKY rats at 9 and 22 mo. Aging itself also slows restitution, with R50 in 22-mo WKY rats greater than that found in young animals, although this slowing is significantly less than that in HF.

DISCUSSION

The pathophysiology of HF has been studied in many animal models and has revealed numerous defects in Ca2+ cycling in both animal and human HF. The SHR model is particularly attractive because it mimics clinical developments common to many hypertensive patients. The early development of hypertension (11, 26) leads to a compensatory positive inotropic effect after 6 mo in SHRs (10, 44), but there is no information about the changes in Ca2+ cycling as this form of compensation transitions to decompensation. Contractile performance then declines slowly, ending in HF after 18 mo of age (7, 14, 40). Our investigation focused on the early changes in E-C coupling in the 6–9-mo window before decompensation occurs. We found distinct changes in E-C coupling that could explain both the late decline in pump function in HF and the increased vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias that occurs beginning as early as 4 mo in SHRs (17, 57).

Defects in Ca2+ cycling develop before HF.

We found that fundamental alterations in basal Ca2+ transients occur long before HF develops. The early positive inotropic effect has been reported previously (44, 47), and the negative inotropic state in overt HF has also been reported in numerous studies (20, 46). The positive inotropic phase may arise because of altered interactions between LCC and RyRs in junctional SR that enhance release without changing the LCC trigger (44), although no precise mechanisms have been proposed and no changes in LCC or RyR number have been reported. In contrast, the negative inotropic state in HF may develop because of the disruption in the T-tubule network, leaving orphaned RyRs without activation by LCC, which has been found in SHRs (45) and other HF models as well (5, 34, 35).

Our results are the first to document cellular changes in Ca2+ cycling during the transition from positive to negative inotropy. The first change was a prolongation of Ca2+ transient duration that occurred in a highly heterogeneous manner between individual myocytes even during the overall positive inotropic phase. Thus the greatest variability occurred at 7.5 mo, presumably because there was a nearly equal split between cell populations with short and long Ca2+ transients. Decreased SERCA (or Na+/Ca2+ exchange) expression or activity could be responsible for a slowing in Ca2+ removal from the cytoplasm. These results are consistent with the time course and heterogeneity of decay time and −dF/dt. Furthermore, the GIs for these parameters indicate that cell-to-cell differences occur randomly between myocytes and are not the result of systematic or regional changes in Ca2+ reuptake. This important early change in Ca2+ transient kinetics probably contributes to the development of diastolic dysfunction as the result of a slowing in relaxation which occurs despite the overall positive inotropic effect. Nearly identical time-dependent changes in Ca2+ release also occur. Not only is there a slowing in rise time and release rate (+dF/dt) between 6 and 9 mo, but the mixture of normal and defective cells peaks midway between these two time points and then declines with age. Presumably, the slowing in Ca2+ release rate could be the result of an early disruption in T-tubule organization, which would increase the number of orphaned RyRs (45), as has recently been reported in another model of hypertension-induced HF in rat heart (51).

We interpret these findings to mean that the defects in Ca2+ cycling present in HF actually are present at a much earlier stage of the disease process than would be predicted from the development of symptoms of HF. Even during the positive inotropic phase, the slowing in both Ca2+ release and reuptake begins to develop, possibly in response to a hypertensive stimulus and as part of the compensatory hypertrophy. Throughout this compensated phase, defects in E-C coupling continue to develop in individual myocytes so that there is a shift in the number of cells with normal to abnormal Ca2+ cycling, thus explaining the biphasic HI for both the rising and declining phases of the Ca2+ transient. At the end of this process (≥9 mo), more myocytes demonstrate defective E-C coupling, thus initiating a long decline from mild and asymptomatic dysfunction to abnormal pump function and symptomatic HF, consistent with the known literature (8).

The question then remains about why the heart is performing relatively normally while these myocytes are showing clear signs of altered Ca2+ cycling. One possible answer comes from our additional observations about spontaneous Ca2+ waves during the development of HF. Waves occur at a high incidence during HF, suggesting that additional defects in E-C coupling have developed during the transition from abnormal E-C coupling with normal function to abnormal E-C coupling and HF. Spontaneous Ca2+ waves occur when SR Ca2+ content exceeds the threshold for release, causing Ca2+ to be released spontaneously into the cytoplasm. Moreover, we found that triggered waves occur in myocytes whose normal E-C coupling mechanisms are overtly impaired, so that LCC activation is unable to activate normal Ca2+ transients even though SR Ca2+ load is high [current study and Wasserstrom et al. (49)]. One consequence of Ca2+ waves is an increase in resting cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels as a result of the slower release/reuptake cycling that both contributes to and is a product of the overall Ca2+ overload driving the spontaneous waves. This Ca2+ overload has also been shown to be critically important in causing apoptosis in these cells (13). Thus it is likely that the decline in cardiac function beginning after 9 mo in SHRs is the result of myocyte loss and replacement with fibrous tissue that occurs in HF. Not only is there a steady decline in myocytes with relatively normal E-C coupling throughout this period (reducing the efficiency of myocyte contraction), but there is also a decline in myocytes with even marginally functioning Ca2+ cycling. As cells develop defects that lead to increased spontaneous Ca2+ release, they are removed from providing any contribution to mechanical performance. HF development may also be influenced by the fact that these cells are likely to be replaced by fibrosis, which increases myocardial stiffness in addition to the loss of viable myocyte population. This possibility is supported by results from a completely different rat model of severe ventricular dysfunction as a result of aging where end-diastolic pressure was increased, first derivative of pressure was decreased, and fibrosis increased from 8 to 16% (3). Moreover, it has been suggested by others that collagen accumulation with age reduces myocardial compliance and may thus be responsible for both diastolic and systolic HF (4, 40, 50). Taken together, these data suggest that the development of HF occurs as a result of a slow loss of abnormally functioning myocytes that fall victim to defective Ca2+ cycling and Ca2+ overload.

Increased susceptibility to three forms of Ca2+ transient alternans: rate-dependent changes in Ca2+ cycling during the transition to HF.

T-wave alternans (TWA) is an important prognostic marker of arrhythmogenesis in HF (42) and is closely related to an increased susceptibility to Ca2+ transient alternans in HF (9, 16, 37, 49, 52). We found a progressive increase in susceptibility to several forms of cellular Ca2+ alternans, including intercellular concordant alternans, intercellular discordant alternans, and subcellular alternans. An increased vulnerability to intercellular concordant alternans, which is most closely associated with TWA, was greater in SHRs than in WKY animals at 9 and 22 mo. Ca2+ transient duration was also prolonged beginning at 9 mo as was the rate of restitution of Ca2+ release, both of which might contribute to an increased alternans susceptibility (1, 48) because less time is allowed for recovery of SR release between heart beats (48). This is an important finding since the current thinking is that intercellular concordant Ca2+ alternans may be responsible for the development of repolarization gradients, thus establishing the substrate for reentry. A greater susceptibility to intercellular concordant alternans at lower heart rates could explain why HF patients, whose resting heart rate is higher than normals, have a high incidence of TWA and are more vulnerable to arrhythmias. Furthermore, our data show a greater vulnerability to Ca2+ alternans when Ca2+ transient duration is prolonged (9 mo) and restitution is slowed, suggesting that these characteristics of HF might contribute to the development of Ca2+ alternans, pulses alternans, TWA, and reentry long before overt HF is detected (41).

We also found increased susceptibility to the highly heterogeneous state of Ca2+ cycling where intercellular discordant alternans ensues, also called dyssynchronous Ca2+ transient alternans (1), in SHRs as early as 7.5 mo. The fact that there is greater susceptibility to intercellular discordant alternans during the early peak of HI for Ca2+ transient duration is expected. Although the physiological significance of intercellular discordant alternans is not yet clear, it has been implicated as a precursor to lethal arrhythmias, especially in the setting of HF (6). This is not unexpected if intercellular discordant alternans emerged in a regionally heterogeneous manner, as the highly heterogeneous Ca2+ cycling in intercellular discordant alternans would (via Ca2+→voltage coupling) promote electrical heterogeneities (43). If, however, intercellular discordant alternans emerged in a more regionally homogeneous manner, the intercellular phase-mismatched Ca2+ alternans may be effectively averaged out across the myocardium, similar to the recordings of mean fluorescence in the 9- and 22-mo SHR recordings in Fig. 4. This may actually reduce the likelihood of reentrant arrhythmias and serve to maintain a more constant beat-to-beat cardiac output even at high rates, thus diminishing the impact of Ca2+ alternans on cardiac output in HF.

A third form of Ca2+ transient alternans, subcellular alternans (28), was also more prevalent in SHRs starting at 7.5 mo. It is not yet known how subcellular alternans affects cardiac function because of the small scale of any effects on mechanical and electrical activity. However, the fact that subcellular Ca2+ transient alternans is also increased at 7.5 mo suggests that the heterogeneity in Ca2+ cycling occurs not only on a cellular level but may also occur at the intracellular level, which together with rapid pacing-induced instabilities in Ca2+ cycling dynamics is sufficient to induce subcellular Ca2+ alternans (2). We have demonstrated a possible means by which subcellular alternans can lead to intercellular discordant alternans (2) and are currently examining the subcellular heterogeneities in Ca2+ cycling during HF development to further investigate the role of subcellular Ca2+ alternans in arrhythmogenesis susceptibility in normal versus diseased heart.

Ca2+ waves, reduced cardiac output, and arrhythmias.

The high incidence of Ca2+ waves, both spontaneous and triggered, is likely to have profound effects on both mechanical and electrophysiological function long before HF has developed. The presence of spontaneous Ca2+ waves is associated with spontaneous beats and triggered arrhythmias, so it is interesting that there is a higher incidence of both types of waves at all ages, suggesting the potential for triggered arrhythmias at all stages of disease progression but particularly in advanced HF. Ca2+ waves are thought to arise only under conditions of SR Ca2+ overload, although it is possible that the threshold for spontaneous release may be altered in HF because of an increased phosphorylation state (32). The same is probably true of triggered waves, but we found that these cells show extremely poor Ca2+ release during cardiac activation despite high SR load. Their failure to release during normal pacing leads to progressive Ca2+ overload in the form of a wave that is activated in response to normal E-C coupling mechanisms but which cannot induce uniform Ca2+ transients along the entire cell length (49). Thus the efficiency of E-C coupling is impaired in these cells, making them unable to contribute to mechanical function. This is probably not a major issue early when most cells can function fairly normally (through 9 mo) but may contribute later to a reduced mechanical performance and to an acceleration of HF as the proportion of defective myocytes increases.

Changes in E-C coupling with aging.

There are many studies that report changes in E-C coupling during aging which have generally shown a decrease in Ca2+ transient magnitude (and accompanying negative inotropic effect) in rodents but a positive inotropic effect in sheep (15, 23, 25, 58). Human studies show that cardiac contractile function is relatively well preserved at rest regardless of age, although the ability to increase contractile force in response to increased demand is compromised, and myocardial relaxation is slowed in older adults (29, 30). Similar results have been seen in rodents and related specifically to intracellular Ca2+ dynamics (23) where the decline in cardiac contractile function with aging occurs concurrently with alterations in Ca2+ handling (18, 25, 31, 54). In young myocytes, contractions and Ca2+ transients rise more rapidly at higher stimulation frequencies. However, aged myocytes produce much smaller increases in peak Ca2+ transients than younger cells when myocytes are paced at rapid rates. In addition, the rates of decay are prolonged in aged cells compared with younger cells under these experimental conditions. A reduced expression of SERCA in aged myocytes may be responsible for the observed effects (33) although this issue is controversial (55). In addition, a recent study showed that Na+/Ca2+ exchange activity actually increases with age in intact ventricular myocytes (36) which could compensate, at least in part, for the age-related decline in SERCA activity and help remove Ca2+ from the aging cardiac myocyte during relaxation. Proteins involved in SR Ca2+ release have also been shown to change with age, including a reduction in RyR2 expression in the aging heart (38). Aging also alters RyR2 function, with data suggesting that the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks increases with age in mouse ventricular myocytes, although the duration of individual Ca2+ sparks declines (24). These studies demonstrate both molecular and physiological changes in Ca2+ handling in normal ventricular myocytes with age, an observation that is strongly supported by our results in WKY, which provide more precision about when some of these changes occur during senescence. Interestingly, we found that Ca2+ transient amplitude and duration are unchanged until WKY rats are nearly 2 yr old. The prolongation of the Ca2+ transient occurs consequent to a slowed reuptake rate in these older rats just as described above in other normal rat models and which is consistent with reports that SERCA is less active (21). These older rats also show slowed Ca2+ transient restitution, possibly related to the slower SR reuptake, which is also likely to be responsible for an increased vulnerability to intercellular concordant alternans found in the present study and in studies of aging animals (19). These effects could explain why there is an increase in TWA and reentrant arrhythmias in elderly patients in the absence of fibrosis (52).

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-68733 and HL-071865 (to C. W. Balke) and HL-101196 (to R. Arora).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aistrup GL, Kelly JE, Kapur S, Kowalczyk M, Sysman-Wolpin I, Kadish AH, Wasserstrom JA. Pacing-induced heterogeneities in intracellular Ca2+ signaling, cardiac alternans, and ventricular arrhythmias in intact rat heart. Circ Res 99: e65–e73, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aistrup GL, Shiferaw Y, Kapur S, Kadish AH, Wasserstrom JA. Mechanisms underlying the formation and dynamics of subcellular calcium alternans in the intact rat heart. Circ Res 104: 639–649, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anversa P, Palackal T, Sonnenblick EH, Olivetti G, Meggs LG, Capasso JM. Myocyte cell loss and myocyte cellular hyperplasia in the hypertrophied aging rat heart. Circ Res 67: 871–885, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Averill DB, Ferrario CM, Tarazi RC, Sen S, Bajbus R. Cardiac performance in rats with renal hypertension. Circ Res 38: 280–288, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balijepalli RC, Lokuta AJ, Maertz NA, Buck JM, Haworth RA, Valdivia HH, Kamp TJ. Depletion of T-tubules and specific subcellular changes in sarcolemmal proteins in tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 59: 67–77, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belevych AE, Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Terentyeva R, Sridhar A, Nishijima Y, Wilson LD, Cardounel AJ, Laurita KR, Carnes CA, Billman GE, Gyorke S. Redox modification of ryanodine receptors underlies calcium alternans in a canine model of sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc Res 84: 387–395, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bing OH, Brooks WW, Robinson KG, Slawsky MT, Hayes JA, Litwin SE, Sen S, Conrad CH. The spontaneously hypertensive rat as a model of the transition from compensated left ventricular hypertrophy to failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 27: 383–396, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boluyt MO, O'Neill L, Meredith AL, Bing OH, Brooks WW, Conrad CH, Crow MT, Lakatta EG. Alterations in cardiac gene expression during the transition from stable hypertrophy to heart failure. Marked upregulation of genes encoding extracellular matrix components. Circ Res 75: 23–32, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks WW, Bing OH, Litwin SE, Conrad CH, Morgan JP. Effects of treppe and calcium on intracellular calcium and function in the failing heart from the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 24: 347–356, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooksby P, Levi AJ, Jones JV. Investigation of the mechanisms underlying the increased contraction of hypertrophied ventricular myocytes isolated from the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Cardiovasc Res 27: 1268–1277, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen-Izu Y, Chen L, Banyasz T, McCulle SL, Norton B, Scharf SM, Agarwal A, Patwardhan A, Izu LT, Balke CW. Hypertension-induced remodeling of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in ventricular myocytes occurs prior to hypertrophy development. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H3301–H3310, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen-Izu Y, Ward CW, Stark W, Jr, Banyasz T, Sumandea MP, Balke CW, Izu LT, Wehrens XH. Phosphorylation of RyR2 and shortening of RyR2 cluster spacing in spontaneously hypertensive rat with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2409–H2417, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X, Zhang X, Kubo H, Harris DM, Mills GD, Moyer J, Berretta R, Potts ST, Marsh JD, Houser SR. Ca2+ influx-induced sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ overload causes mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in ventricular myocytes. Circ Res 97: 1009–1017, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conrad CH, Brooks WW, Robinson KG, Bing OH. Impaired myocardial function in spontaneously hypertensive rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 260: H136–H145, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dibb KM, Rueckschloss U, Eisner DA, Isenberg G, Trafford AW. Mechanisms underlying enhanced cardiac excitation contraction coupling observed in the senescent sheep myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 37: 1171–1181, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dumitrescu C, Narayan P, Efimov IR, Cheng Y, Radin MJ, McCune SA, Altschuld RA. Mechanical alternans and restitution in failing SHHF rat left ventricles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1320–H1326, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans SJ, Levi AJ, Jones JV. Wall stress induced arrhythmia is enhanced by low potassium and early left ventricular hypertrophy in the working rat heart. Cardiovasc Res 29: 555–562, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fares E, Howlett SE. Effect of age on cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 37: 1–7, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frolkis VV, Frolkis RA, Mkhitarian LS, Shevchuk VG, Fraifeld VE, Vakulenko LG, Syrovy I. Contractile function and Ca2+ transport system of myocardium in ageing. Gerontology 34: 64–74, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez AM, Valdivia HH, Cheng H, Lederer MR, Santana LF, Cannell MB, McCune SA, Altschuld RA, Lederer WJ. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science 276: 800–806, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasenfuss G. Alterations of calcium-regulatory proteins in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 37: 279–289, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houser SR, Piacentino V, 3rd, Weisser J. Abnormalities of calcium cycling in the hypertrophied and failing heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 32: 1595–1607, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howlett SE. Age-associated changes in excitation-contraction coupling are more prominent in ventricular myocytes from male rats than in myocytes from female rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H659–H670, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howlett SE, Grandy SA, Ferrier GR. Calcium spark properties in ventricular myocytes are altered in aged mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1566–H1574, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isenberg G, Borschke B, Rueckschloss U. Ca2+ transients of cardiomyocytes from senescent mice peak late and decay slowly. Cell Calcium 34: 271–280, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito H, Goto K, Fuseno H, Hayase S. Action of anti-arrhythmic beta-blockaders. [In Japanese.] Nippon Rinsho 32: 2859–2864, 1974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapur S, Wasserstrom JA, Kelly JE, Kadish AH, Aistrup GL. Acidosis and ischemia increase cellular Ca2+ transient alternans and repolarization alternans susceptibility in the intact rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H1491–H1512, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kockskamper J, Blatter LA. Subcellular Ca2+ alternans represents a novel mechanism for the generation of arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 545: 65–79, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part II: the aging heart in health: links to heart disease. Circulation 107: 346–354, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakatta EG, Sollott SJ. Perspectives on mammalian cardiovascular aging: humans to molecules. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 132: 699–721, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim CC, Apstein CS, Colucci WS, Liao R. Impaired cell shortening and relengthening with increased pacing frequency are intrinsic to the senescent mouse cardiomyocyte. J Mol Cell Cardiol 32: 2075–2082, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Limas CJ, Cohn JN. Defective calcium transport by cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res 40: I62–I69, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lompre AM, Lambert F, Lakatta EG, Schwartz K. Expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase and calsequestrin genes in rat heart during ontogenic development and aging. Circ Res 69: 1380–1388, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louch WE, Bito V, Heinzel FR, Macianskiene R, Vanhaecke J, Flameng W, Mubagwa K, Sipido KR. Reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release with loss of T-tubules-a comparison to Ca2+ release in human failing cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res 62: 63–73, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Louch WE, Mork HK, Sexton J, Stromme TA, Laake P, Sjaastad I, Sejersted OM. T-tubule disorganization and reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release in murine cardiomyocytes following myocardial infarction. J Physiol 574: 519–533, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mace LC, Palmer BM, Brown DA, Jew KN, Lynch JM, Glunt JM, Parsons TA, Cheung JY, Moore RL. Influence of age and run training on cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchange. J Appl Physiol 95: 1994–2003, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narayan P, McCune SA, Robitaille PM, Hohl CM, Altschuld RA. Mechanical alternans and the force-frequency relationship in failing rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 27: 523–530, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicholl PA, Howlett SE. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release channels in ventricles of older adult hamsters. Can J Aging 25: 107–113, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orchard CH, Lakatta EG. Intracellular calcium transients and developed tension in rat heart muscle. A mechanism for the negative interval-strength relationship. J Gen Physiol 86: 637–651, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfeffer JM, Pfeffer MA, Fishbein MC, Frohlich ED. Cardiac function and morphology with aging in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 237: H461–H468, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res 88: 1159–1167, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salerno-Uriarte JA, De Ferrari GM, Klersy C, Pedretti RF, Tritto M, Sallusti L, Libero L, Pettinati G, Molon G, Curnis A, Occhetta E, Morandi F, Ferrero P, Accardi F. Prognostic value of T-wave alternans in patients with heart failure due to nonischemic cardiomyopathy: results of the ALPHA Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 1896–1904, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sato D, Shiferaw Y, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN, Qu Z, Karma A. Spatially discordant alternans in cardiac tissue: role of calcium cycling. Circ Res 99: 520–527, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shorofsky SR, Aggarwal R, Corretti M, Baffa JM, Strum JM, Al-Seikhan BA, Kobayashi YM, Jones LR, Wier WG, Balke CW. Cellular mechanisms of altered contractility in the hypertrophied heart: big hearts, big sparks. Circ Res 84: 424–434, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song LS, Sobie EA, McCulle S, Lederer WJ, Balke CW, Cheng H. Orphaned ryanodine receptors in the failing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 4305–4310, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor PB, Helbing RK, Kenno KA. Inotropic interventions and myocardial force-interval relation: a quantitative approach. Can J Cardiol 7: 331–337, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward ML, Pope AJ, Loiselle DS, Cannell MB. Reduced contraction strength with increased intracellular [Ca2+] in left ventricular trabeculae from failing rat hearts. J Physiol 546: 537–550, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wasserstrom JA, Kapur S, Jones S, Faruque T, Sharma R, Kelly JE, Pappas A, Ho W, Kadish AH, Aistrup GL. Characteristics of intracellular Ca2+ cycling in intact rat heart: a comparison of sex differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H1895–H1904, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wasserstrom JA, Sharma R, Kapur S, Kelly JE, Kadish AH, Balke CW, Aistrup GL. Multiple defects in intracellular calcium cycling in whole failing rat heart. Circ Heart Fail 2: 223–232, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weber KT, Janicki JS, Shroff SG, Pick R, Chen RM, Bashey RI. Collagen remodeling of the pressure-overloaded, hypertrophied nonhuman primate myocardium. Circ Res 62: 757–765, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei S, Guo A, Chen B, Kutschke W, Xie YP, Zimmerman K, Weiss RM, Anderson ME, Cheng H, Song LS. T-tubule remodeling during transition from hypertrophy to heart failure. Circ Res 107: 520–531, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson LD, Wan X, Rosenbaum DS. Cellular alternans: a mechanism linking calcium cycling proteins to cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1080: 216–234, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu Y, Clusin WT. Calcium transient alternans in blood-perfused ischemic hearts: observations with fluorescent indicator fura red. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H2161–H2169, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiao RP, Spurgeon HA, O'Connor F, Lakatta EG. Age-associated changes in beta-adrenergic modulation on rat cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. J Clin Invest 94: 2051–2059, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu A, Narayanan N. Effects of aging on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-cycling proteins and their phosphorylation in rat myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H2087–H2094, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoneda T, Kihara Y, Ohkusa T, Iwanaga Y, Inagaki K, Takeuchi Y, Hayashida W, Ueyama T, Hisamatsu Y, Fujita M, Hatac S, Matsuzaki M, Sasayama S. Calcium handling and sarcoplasmic-reticular protein functions during heart-failure transition in ventricular myocardium from rats with hypertension. Life Sci 70: 143–157, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaugg CE, Wu ST, Lee RJ, Wikman-Coffelt J, Parmley WW. Intracellular Ca2+ handling and vulnerability to ventricular fibrillation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 30: 461–467, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu X, Altschafl BA, Hajjar RJ, Valdivia HH, Schmidt U. Altered Ca2+ sparks and gating properties of ryanodine receptors in aging cardiomyocytes. Cell Calcium 37: 583–591, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]