Abstract

The voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 has been recently identified as a molecular target that allows the selective pharmacological suppression of effector memory T cells (TEM) without affecting the function of naïve T cells (TN) and central memory T cells (TCM). We found that Kv1.3 was expressed on glomeruli and some tubules in rats with anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis (anti-GBM GN). A flow cytometry analysis using kidney cells revealed that most of the CD4+ T cells and some of the CD8+ T cells had the TEM phenotype (CD45RC−CD62L−). Double immunofluorescence staining using mononuclear cell suspensions isolated from anti-GBM GN kidney showed that Kv1.3 was expressed on T cells and some macrophages. We therefore investigated whether the Kv1.3 blocker Psora-4 can be used to treat anti-GBM GN. Rats that had been given an injection of rabbit anti-rat GBM antibody were also injected with Psora-4 or the vehicle intraperitoneally. Rats given Psora-4 showed less proteinuria and fewer crescentic glomeruli than rats given the vehicle. These results suggest that TEM and some macrophages expressing Kv1.3 channels play a critical role in the pathogenesis of crescentic GN and that Psora-4 will be useful for the treatment of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

Keywords: WKY rats, crescentic glomerulonephritis, flow cytometric analysis

rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) is a syndrome characterized by a sudden and relentless decline in renal function associated with extensive crescent formation involving most glomeruli (21). RPGN is caused by autoimmune diseases, such as anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis (anti-GBM GN; also known as Goodpasture's syndrome), antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. RPGN is commonly treated with corticosteroid and/or immunosuppressive agents but is associated with a high mortality rate because of pulmonary hemorrhage, acute kidney injury, or infection caused by the disease itself or by the immunosuppressants. Thus a more specific treatment targeting the pathogenesis of the disease is urgently required.

The potassium (K+) channel is encoded by an extended superfamily of 76 genes and exhibits the largest diversity among all known ion channels in humans (25). The K+ channel hyperpolarizes the membrane potential and modulates excitability appropriate for the cell's function. Multiple K+ channel subtypes are usually expressed together on the cell surface membrane, and the expression pattern of K+ channels gives each cell its unique function. Therefore, a particular cell's function could be controlled if the cell-type-specific K+ channel were to be selectively activated or blocked (8, 22). K+ channels are expected to be key drug targets for the treatment of a variety of diseases (60). Examples include 1) a Kv1.5 blocker for atrial fibrillation (14), 2) a KCNQ2/3 activator for epilepsy and use as an analgesic agent (24), and 3) a KCNQ1 (Kv2.1) blocker for diabetes (62). Recently, researchers (8, 23) have observed distinct patterns in the expression of the voltage-gated K+ channel Kv1.3 and the calcium-activated K+ channel KCa3.1 that depend on the state of T-cell activation and differentiation.

Naïve T cells (TN) are mature T cells that have not yet encountered an antigen. Following an encounter with an antigen, the T cells divide and differentiate. Most of their progeny become short-lived effector cells, while some become long-lived memory cells. Effector memory T cells (TEM) are one type of memory cell. This cell type can move directly to the sites of inflammation and exert effector functions. Central memory T cells (TCM) are another type of memory cell that migrates to the lymph node before moving to the site of inflammation, requires longer to differentiate into effecter cells, and does not secrete many cytokines (41, 48). In rats, the subsets of memory T cells are divided by the expression pattern of the lymph node homing receptors CD62L (l-selectin) and CCR7 and the leukocyte common antigen CD45RC as follows: TN, CD45RC+CCR7+CD62Lhigh; TEM, CD45RC−CCR7−CD62Llow; and TCM, CD45RC−CCR7+CD62Lhigh. TEM express significantly higher levels of Kv1.3 channels and lower levels of KCa3.1 channels than TN and TCM (22, 59). Therefore, Kv1.3 blockers affect TEM selectively by depolarizing their membrane potential, thereby attenuating the Ca2+ signaling pathway necessary for T-cell activation (8).

Many studies have reported an association between Kv1.3-expressing TEM and autoimmune disease. Disease-associated autoreactive T cells from the blood of patients with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or type 1 diabetes display a TEM phenotype characterized by Kv1.3high in the blood, whereas T cells specific for disease-irrelevant antigens from the same patient populations or T cells specific for auto-antigens in control populations are CCR7+Kv1.3low TN or TCM (10, 43, 59). In rat models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and allergic contact dermatitis, the phenotype of T cells at the sites of inflammation is CCR7−CD45RC−Kv1.3high TEM (7, 55). Furthermore, the administration of a Kv1.3 blocker selectively suppresses the proliferation of TEM without persistently suppressing TN and TCM (8, 9, 55).

Although the expression of Kv1.3 channels has not yet been investigated in progressive renal diseases, several authors have speculated that TEM could be related to the progression of RPGN, such as ANCA-associated vasculitis (1, 2, 13, 44) and lupus nephritis (15). We therefore hypothesized that Kv1.3-expressing TEM may contribute to the pathogenesis of RPGN. The rat model of anti-GBM GN is characterized by the massive accumulation of T cells and monocytes/macrophages in the glomeruli and by a high rate of crescent formation in the glomeruli (51). T cells have been found to induce glomerular injury through macrophage recruitment and activation akin to delayed-type hypersensitivity as well as through their effector functions (30). In the work reported here, we investigated the association of Kv1.3-expressing TEM with anti-GBM in rats and subsequently investigated whether a Kv1.3 blocker, Psora-4, could prevent renal damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

Five- to six-week-old male Wistar-Kyoto rats obtained from Charles River (Atsugi, Japan) were used. Animal care was in accordance with the National Defense Medical College Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in Research. The study protocols were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of the National Defense Medical College. Anti-GBM GN was induced by the injection of rabbit anti-rat GBM antibody (19, 20) at a dose of 25.0 μl/100 g body wt on day 0. Psora-4 (5-[4-phenylbutoxy] psoralen) is a potent small-molecule Kv1.3 blocker that blocks Kv1.3 channels in a use-dependent manner; its Hill coefficient is 2 and its EC50 is 3 nM, which is 17- to 70-fold lower than the EC50 values for its blockade of all closely related Kv1-family channels (Kv1.1, Kv1.2, Kv1.4, and Kv1.7) other than Kv1.5 (EC50 = 7.7 nM; Ref. 55). Psora-4 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and was dissolved in a mixture of 25% CremophorEL and 75% PBS to prepare a concentration of 9 mg/ml.

To investigate differences between the results of early and delayed treatments with Psora-4 (n = 6 at each time point), rats were injected with a 9 mg/ml dose of Psora-4 from day 0 to day 21 in the early treatment group and from day 7 to day 21 in the delayed treatment group. The rats received four injections during the first 24 h, three injections during the second 24 h, and two injections from then onward (0.3 ml per dose of vehicle or Psora-4 at a concentration of 9 mg/ml ip). In the vehicle group, the intraperitoneal injection of only the vehicle (without Psora-4) was started on day 0 or day 7 after the injection of the anti-GBM serum. The animals were housed in metabolic cages to collect 24-h urine samples on days 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21; during these 24-h periods, the rats had free access to standard chow and water. Body weight was measured at the end of each 24-h urine collection. Rats were killed on days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 21. Rats injected with normal rabbit IgG were used as an untreated normal control group. Blood was collected from the abdominal aorta, and the serum levels of creatinine were measured using an enzymatic method (SRL, Tokyo, Japan). The kidneys were removed for histological examination. Urinary creatinine was also measured using an enzymatic method (SRL), and the creatinine clearance was calculated.

Histological examination and immunostaining.

The kidneys were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. All formalin-fixed kidney sections (3 μm) were stained with periodic acid-methenamine-silver. The percentage of glomeruli with crescent formation was counted by examining 50 consecutive glomeruli stained with periodic acid-methenamine-silver. Sections of the kidney were stained with primary antibodies (see Table 1) using standard indirect immunoperoxidase staining techniques. More than 50 glomeruli from each section were examined under a high-power field (×400), and the number of stained cells was counted. The number of interstitial infiltrating cells in 10 high-power fields was also counted.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in this study

| Specificity | Clone | Labeling | Origin | Pretreatment for IHC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3 | 1F4, 1F4, 4.18 | Unlabeled, Alexa−488, PE | c, c, a | Autoclave |

| CD4 | W3/25 | biotin | b | |

| CD8 | OX8 | PE-Cy5 | a | |

| CD11b/c | OX42 | PE | c, a | |

| CD45RC | OX22 | FITC, PE | c, c | Proteinase K |

| CCR7 | E75 | Unlabeled | e | Proteinase K |

| CD62L | OX85 | PE, biotin | c, c | |

| CD68 | ED1 | PE, unlabeled, Alexa-488 | c, c, c | Proteinase K |

| CD161a | 3.2.3 | PE | c | |

| Kv1.3 | L23/27, polyclonal | Unlabeled, FITC | d, f | Autoclave |

| αβTCR | R7/3 | PE, unlabeled | a, a | |

| γδTCR | V65 | PE, unlabeled | a, a | |

| Biotin | PE-Cy5, PE | a, a |

IHC, immunohistochemistry; proteinase K, incubated with proteinase K (Dako) for 8 min; autoclave, boiled in citrated buffer (pH 6) via autoclave (121°C) for 15 min; PE, phycoerythin. aBD bioscience; bBiolegend; cSerotec; dAlomone Lab; eEPTMICS; fNeuroMab.

Mononuclear cell preparation for flow cytometry analysis and immunohistochemistry.

The rats (each group: n = 5) in the normal kidney group and the vehicle group were killed on day 7, and the kidneys were removed. The kidney mononuclear cells were prepared as described previously (3, 37). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained using the standard method with PANCOLL (PAN Biotech). For three-color flow cytometry, cells from each sample were stained for 30 min at 4°C with the optimal dilution of the antibodies (see Table 1). The labeled cells were analyzed with a flow cytometry analyzer (EPICS XL; Beckman Coulter), and the obtained data were analyzed with Expo. 32 software (Beckman Coulter). Mononuclear cells isolated from the kidney (vehicle group killed on day 7) were also used for immunohistochemistry. The isolated cells were deposited onto microscope slides by centrifugal force (50 g for 5 min) using a Cytospin 4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), fixed for 10 min with acetone at −20°C before staining, and stained with anti-Kv1.3 mAb as a primary antibody (see Table 1). After being washed in PBS, the cells were incubated with Alexa-594-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Invitrogen) as the secondary antibody. After blocking with 10% normal mouse serum, the sections were stained with Alexa-488-conjugated anti-rat CD3 mAb or Alexa-488-conjugated anti-ED-1 mAb, followed by incubation with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma) for nuclear counterstaining. The slides were analyzed using confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510).

Magnetic cell sorting.

Kidney and peripheral blood cell suspensions were prepared using the same procedure as that used for the flow cytometry analysis. To obtain the CD8−αβ/γδTCR+ cell fraction (corresponding to the CD4+ T cells), the cell suspensions were first labeled with CD8 mAb and then depleted using anti-mouse IgG magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech). The depleted fractions were finally isolated αβ/γδ TCR+ T cells by positive selection using pan-T-cell MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec). The CD8−αβ/γδTCR+ cell fraction (corresponded to CD8+ T cells) was obtained using the same procedure as that used for the CD8−αβ/γδTCR+ cells. For the ED-1+ cell fractions, the cell suspensions were first labeled using anti-ED-1 mAb and then positively selected using anti-mouse IgG magnetic beads.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from the renal cortex and magnetically isolated cells using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A 5-μg aliquot of total RNA was reverse transcribed with SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The resulting complementary DNA (cDNA) was then used as a template for real-time quantitative PCR with the TaqMan Gene Expression Assays primer/probe sets for rat IL1-β (Rn00580432_m1), IL-17A (Rn01757168_m1), IFN-γ (Rn00594078_m1), TNF-α (Rn99999017_m1), and GAPDH (Rn99999916_s1); TaqMan Mastermix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was also used. Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The relative amount of mRNA was calculated using the comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) method. All specific amplification products were normalized against GAPDH mRNA, which was amplified in the same reaction as an internal control.

Statistical analysis.

The results are expressed as means ± SD. The data were statistically analyzed using an ANOVA followed by the Fishers correlation test. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

T cells infiltrating the kidney have an effector memory T-cell phenotype.

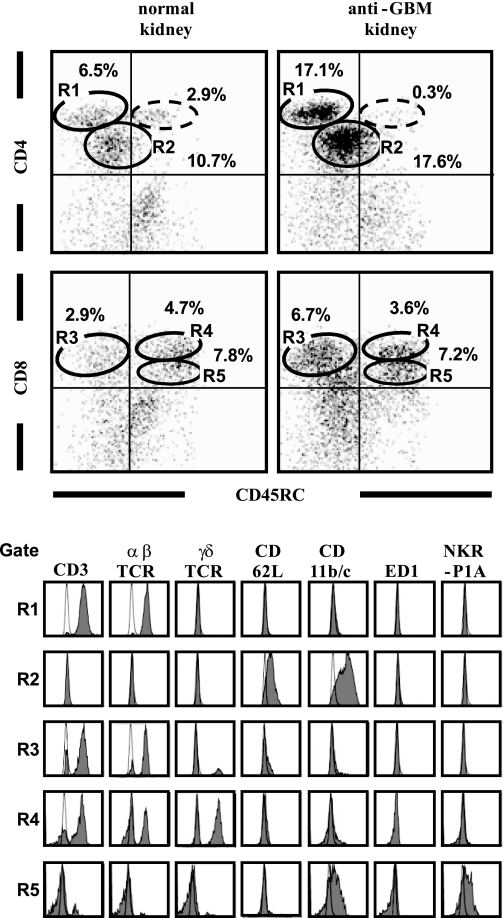

To identify the phenotype of T cells that had infiltrated the kidney, we performed a flow cytometric analysis of mononuclear cell suspensions from normal and anti-GBM GN kidneys obtained on day 7 (Fig. 1). By the analysis with CD45RC and CD4/CD8α, we found five major distinct populations in the isolated kidney cell suspensions: R1 to R5. In the anti-GBM kidney, the proportion of CD4bright cells (gate R1) and CD4intcells (R2), and CD8αbrightCD45RC−cells (R3) was increased compared with that in the normal rat kidney. The majority of CD4bright cells (R1) was positive for the T-cell markers CD3 and αβTCR and negative for CD45RC and CD62L, and thus corresponded to TEM. The CD8αbright cells, on the other hand, were divided into CD45RC+ and CD45RC− populations. The CD8αbrightCD45RC− cells (R3) were positive for CD3 and negative for CD62L and thus corresponded to TEM. The CD8αbrightCD45RC+ cells (R4) were positive for CD3 and negative for CD62L and did not correspond to any known phenotype of memory T cells. Interestingly, the majority of the CD8αbrightCD45RC+ (R4) cells was comprised of not αβTCR+, but rather γδTCR+ T cells, unlike the proportions in other T-cell subsets. Most cells in the R2 and R5 subsets were not T cells, since they lacked CD3, αβTCR, or γδTCR.

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometry analysis to determine the phenotype of T cells infiltrating the normal and anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis (anti-GBM GN) kidneys on day 7. After gating with a “lymphocyte gate” (based on forward and side scattering), the cell population was double-stained with mAbs for CD45RC and either CD4 or CD8α. Expression of CD3, αβTCR, γδTCR, CD62L, CD11b/c, ED-1, and NKR-P1A was analyzed after gating for CD4brightCD45RC− (gate R1), CD4dimCD45RC− (gate R2), CD8brightCD45RC− (gate R3), CD8brightCD45RC+ (gate R4), and CD8dimCD45RC+ (gate R5). Dotte-line circle indicates the gate of the CD4brightCD45RC+ cells. Numbers added near region gates in dot plot indicate percentage of gated cells within the lymphocyte gate. Shaded histograms show staining with the indicated mAbs. Open histograms show staining with isotype-matched controls.

We found differences in minor T-cell distribution population (CD4brightCD45RC+ cells; Fig. 1, dotted-line circle) between normal and anti-GBM GN kidneys. CD4brightCD45RC+ cells were rarely found in anti-GBM GN rat kidney. A larger proportion of CD4brightCD45RC+ cells was observed in the normal rat kidney (2.9%) compared with anti-GBM GN kidney (0.3%). These CD4brightCD45RC+ cells were positive for the T-cell markers CD3 and αβTCR and negative for CD62L (data not shown). We also found the following differences in T-cell distribution between normal and anti-GBM GN kidneys. The CD8αbrightCD45RC−-to-CD8αbright CD45RC+ cell ratio was increased three times in the anti-GBM kidney, and the αβTCR+-to-γδTCR+ cell ratio was increased twice in the anti-GBM GN kidney, compared with the normal kidney (data not shown).

Expression of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 on the proximal tubules of untreated normal rat kidney.

In normal rat kidney (without anti-GBM antibody), Kv1.3 was stained in most of the tubular epithelial cells, which contained varying amounts of weakly stained granular material in the cytoplasm. Kv1.3 staining was prominent in the cortex, rather than in the medulla, and was especially prominent on tubules with a brush border, which were suspected of being proximal tubules (Fig. 2A). Kv1.3+ staining was not found in the glomeruli (Fig. 2B), interstitium, or around the vessel walls in untreated normal kidneys.

Fig. 2.

Expression of the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3, as shown using mouse Kv1.3 mAb, in normal rat kidney (A and B) and anti-GBM GN rat kidney (C-E) and spleen (F). Kv1.3 was expressed on some tubules (A; original magnification, ×100) but not in the glomeruli (B; original magnification, ×200) in normal rat kidney. In contrast, Kv1.3+ cells were observed in the glomeruli (C and D; original magnification, ×200) and in the interstitium (E; original magnification, ×200) on day 7 after the induction of anti-GBM on day 0. Numerous Kv1.3+ cells were seen in the blood within the vessels of the spleen (F; original magnification, ×200).

Expression of the Kv1.3 channel on the glomeruli and interstitium in rats with anti-GBM GN.

In the anti-GBM kidney on days 3 and 7 (anti-GBM antibody was injected on day 0), many Kv1.3+ cells appeared in the glomeruli, interstitium, and in and around the vessel walls. Two patterns of heterogeneous staining for Kv1.3 were observed in the glomeruli. One pattern formed a large, round shape in relatively intact glomeruli (Fig. 2C), while the other type was comprised of small irregular deposits, the peripheries of which were sometimes faintly stained, that had accumulated in the injured glomeruli (Fig. 2D). On day 3, a few large round Kv1.3+ cells were observed in the glomeruli. On day 7, large round Kv1.3+ cells were more frequently observed around the peritubular capillaries (Fig. 2E), rather than in the glomeruli. In contrast, small Kv1.3+ deposits were less obvious on day 3, but many of these deposits had accumulated in the injured glomeruli on day 7. Kv1.3+ cells were abundantly observed in blood pooling in the vessels of the spleen (Fig. 2F) and had the same shape and size as infiltrates in the glomeruli and interstitium.

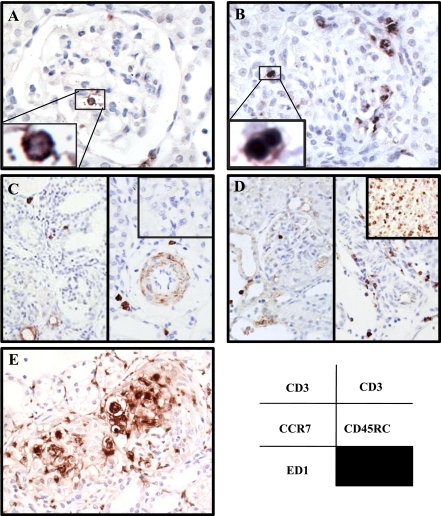

Localization of various cell phenotypes in the kidney of anti-GBM GN.

To identify the localization of immune cells, we performed an immunohistochemical study in anti-GBM GN kidney. CD3+ T cells were frequently seen in and around the glomeruli and in the interstitium. Two types of CD3+ staining patterns were distinguished: 1) a large, round type in relatively intact glomeruli (Fig. 3A), and 2) a smaller type in injured glomeruli (Fig. 3B). CCR7+ cells, which were thought to be TN or TCM, were not detected in the glomeruli, but a small number of these cells were seen in the interstitium around the vessels (Fig. 3C). More CD45RC+ cells were detected than CCR7+ cells, and most of them were observed around the vessels and rarely in the glomeruli (Fig. 3D). In contrast, numerous CCR7+ cells and CD45RC+ cells were observed on the parenchyma of the spleen (Fig. 3, C and D, top right insets). Numerous ED-1+ macrophages were diffusely accumulated in the glomeruli and interstitium. ED-1+ macrophages, which sometimes had a huge foamy appearance, were more variable in size and shape and had a higher tendency to aggregate than CD3+ T cells (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Localization of various phenotype cells in anti-GBM GN kidney on day 7. A: large, round CD3+ T cells have infiltrated the glomeruli. B: small CD3+ T cells have accumulated in the glomeruli. C: CCR7+ cells around the glomeruli (left) and in the interstitium around the vessels (right). D: CD45RC+ cells around the glomeruli (left) and in the interstitium around the vessels (right). Spleen tissue was used as a positive control for CCR7 and CD45RC (C and D, top right insets). CCR7 and CD62L are lymphoid tissue homing receptors expressed on TN and TCM. E: ED-1+ macrophages are present in and around the glomeruli. Original magnification: ×200.

Kv1.3 was expressed on CD3+ T cells and some ED-1+macrophages.

To better examine the localization of Kv1.3 on immune cell subsets, mononuclear cell suspensions that had been isolated from anti-GBM GN kidney on day 7 were observed after staining with anti-Kv1.3 mAb and anti-CD3 mAb or anti-ED-1 mAb. There were two types of CD3+ T cells that differed in size (large and small, suggesting they were CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells, respectively). Kv1.3 channels were expressed on the cell membrane as well as in the cytoplasm of both large and small CD3+ T cells isolated from anti-GBM GN kidney (Fig. 4A). Kv1.3 channels were also expressed on some ED-1+ macrophages, which have a larger cell size with an irregular cell border, compared with ED-1+ macrophages not expressing Kv1.3 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Confocal microscopy examining Kv1.3 channel and CD3 or ED-1 in mononuclear cell suspensions. A: double-immunofluorescent staining for CD3 (green) and Kv1.3 (red) with nuclear staining (Hoechst 33342: blue) on isolated mononuclear cells. Merged image is shown in far right lane. Large CD3+ T cells (arrowhead) and small CD3+ T cells (arrow) are visible (original magnification, ×200). Top right inset: high-magnification view of a large CD3+ T cell (original magnification, ×600). Kv1.3 was expressed on most of the CD3+ T cells. B: double-immunofluorescent staining for ED-1 (green) and Kv1.3 (red) with nuclear staining (Hoechst 33342: blue) on isolated mononuclear cells. Merged image is shown in the rightmost lane. Kv1.3 was expressed on some (*), but not all, of the ED-1+ macrophages (original magnification, ×200).

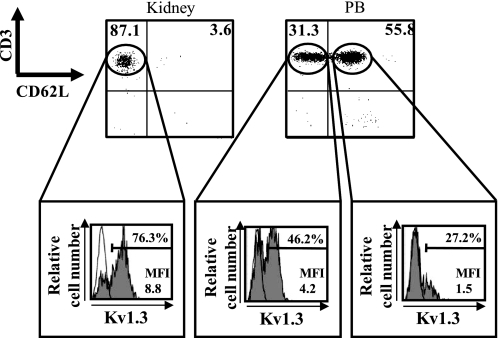

Difference in Kv1.3 expression between CD62L− T cells and CD62L+ T cells.

We analyzed the difference in the Kv1.3 expression level between the CD62L− fraction (including TEM) and the CD62L+ fraction (including TN and TCM) of the T cells (Fig. 5). αβ/γδTCR+ T cells, which were isolated by using magnetic cell sorting from the kidney and peripheral blood in the vehicle group on day 7, were used to minimize the contamination of the tubules as much as possible. In the kidney, most of the T cells were CD62L− T cells. Numerous CD62L+ T cells in the peripheral blood, which differed from those in the kidney, were observed. As expected, a higher intensity of Kv1.3 staining was observed in the CD62L− T cells than in the CD62L+ T cells.

Fig. 5.

Expression of the Kv1.3 channel on CD62L− T cells (corresponding to effector memory T cells) and CD62L+ T cells (corresponding to naïve T cells and central memory T cells). αβ/γδTCR+ T cells isolated from kidney and peripheral blood (PB) in the vehicle group on day 7 were stained with rabbit anti-Kv1.3 polyclonal Ab conjugated with FITC, CD3 mAb conjugated with PE-Cy5, and CD62L mAb conjugated with phycoerythin (PE). Expression of Kv1.3 was analyzed after gating for CD62L− T cell and CD62L+ T-cell subpopulations. Numbers in the top left and top right quadrants are percentages of CD62L− T cells and of CD62L+ T cells, respectively. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) levels are shown for each histogram. Shaded histograms show the level of expression of Kv1.3 measured with FITC-conjugated polyclonal rabbit anti-Kv1.3 antibody. Open histograms represent staining obtained with the FITC-conjugated rabbit IgG isotype control.

Both early and delayed treatments with Psora-4 reduced renal damage.

From the above results, we found that Kv1.3-expressing TEM had infiltrated the anti-GBM GN kidney tissue, indicating that the Kv1.3 channel is likely involved in the pathogenesis of anti-GBM GN. We therefore examined whether the blockade of the Kv1.3 channel could prevent renal damage in anti-GBM GN. As shown in Fig. 6A, a sharp rise in urinary protein excretion in the vehicle group (anti-GBM GN control without Psora-4 treatment) appeared on day 5, and marked urinary protein excretion (105.1 ± 19.3 mg/day) developed on day 7 and continued to increase after day 7. Both early treatment (from day 0 to day 21) and delayed treatment (from day 7 to day 21) with Psora-4 significantly reduced urinary protein excretion. No body weight differences between the groups were observed, except on day 21 (Fig. 6B). The increase in kidney weight in the Psora-4 group was significantly smaller than that in the vehicle group (Fig. 6C). Both early and delayed treatments restored creatinine clearances, which were significantly higher than the creatinine clearance in the vehicle group (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

A: effect of early and delayed Psora-4 treatments on urinary protein excretion. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle group. B: body weight. C: kidney weight. D: creatinine clearance (Ccr). Each plot shows the means ± SD for 6 rats. Closed circles, vehicle group. Open circles, early Psora-4 group (from day 0 to day 21). Double circles, delayed Psora-4 group (from day 7 to day 21). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle group.

Psora-4, a Kv1.3 blocker, reduced crescent formation, and the number of ED-1+ macrophages and CD3+ T cells but not the number of CCR7+ cells.

In the vehicle group, crescent formation and severe necrotizing lesions of the glomeruli were observed from day 7 onwards (Fig. 7A). In parallel with the urinary findings, early Psora-4 treatment reduced the proportion of crescentic glomeruli (Fig. 7B) on day 7 (81 ± 6.1 vs. 43 ± 12.1%; P < 0.05). Delayed Psora-4 treatment also significantly reduced the proportion of crescentic glomeruli significantly (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Representative photographs of histological features in vehicle group (A, C, E, and G) and group treated with Psora-4 (B, D, F, and H) on day 7. A and B: periodic acid-methenamine-silver staining was used to identify crescent formation. C and D: staining for macrophages with ED-1 antibody. E and F: staining for T cells with anti-CD antibody. G and H: staining for naïve T cells and central memory T cells with anti-CCR7 antibody. Original magnification: ×200.

Fig. 8.

Quantification analysis of crescent formation, ED-1+ macrophages, CD+ T cells, and CCR7+ cells. Results are means ± SD for each group. Closed bar, the vehicle group. Dotted bar, the early Psora-4 group. Hatched bar, the delayed Psora-4 group. Mφ, macrophages; glo, glomerulus; IS, interstitium. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

In the vehicle group, the immunohistochemical staining of renal tissue revealed increased numbers of glomerular ED-1+ macrophages (Fig. 7C) and CD3+ T cells (Fig. 7E). Numerous ED-1+ macrophages appeared in the glomeruli and interstitium in the vehicle group on day 3. In the glomeruli, the number of infiltrating ED-1+ macrophages peaked on day 7. The number of ED-1+ macrophages in the interstitium continued to increase throughout the experiment. The increased number of ED-1+ macrophages in the glomeruli was significantly reduced by Psora-4 treatment in both the early and the delayed treatment groups (Figs. 7D and 8). The increased number of ED-1+ macrophages in the interstitium was not reduced by delayed Psora-4 treatment but was significantly reduced by early Psora-4 treatment. A few CD3+ T cells were seen in the glomeruli and interstitium during the early stage (day 3). The number of CD3+ T cells had increased in the glomeruli and interstitium on day 7 and continued to increase after day 7. Psora-4 treatment caused significant reductions in these T cells in both the early and the delayed treatment groups (Figs. 7F and 8). A small number of CCR7+ cells were noted around the peritubular capillaries (Fig. 7G), but these cells were never seen in the glomeruli of either the vehicle or the Psora-4-treated group. Interestingly, Psora-4 treatment did not reduce the number of CCR7+ cells, compared with the vehicle group (Figs. 7H and 8).

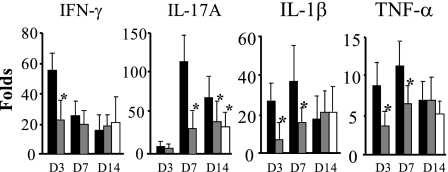

Psora-4 prevented the increased mRNA expressions of inflammatory cytokines in anti-GBM GN.

Figure 9 shows the mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines. In the vehicle group, the expression of IFN-γ mRNA was elevated, peaking during the early stage on day 3 (at a level 52.5-fold greater than the level in untreated normal rat kidney without the induction of anti-GBM GN) but promptly decreasing after day 7. The expression of IL-17A mRNAs peaked on day 7 (at level that was 119.1-fold greater than their levels in normal rat kidney, respectively). The expressions of IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA showed similar trends, with elevated expression levels observed on both days 3 and 7 and reduced expression levels observed on day 14. Early Psora-4 treatment significantly reduced these increases in the expression of cytokine mRNAs. On the other hand, delayed Psora-4 treatment did not reduce these increases with the exception of IL-17A, which was significantly reduced on day 14.

Fig. 9.

mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines. mRNAs were extracted from the renal cortex of kidneys from rats in the untreated normal rat, vehicle group (closed bar), early-Psora-4 group (dotted bar), and delayed-Psora-4 group (hatched bar) and were analyzed using real-time RT-PCR. Results in each graph are means (±SD; n = 6) of the fold increases over the corresponding levels for the untreated normal rat kidney. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle group.

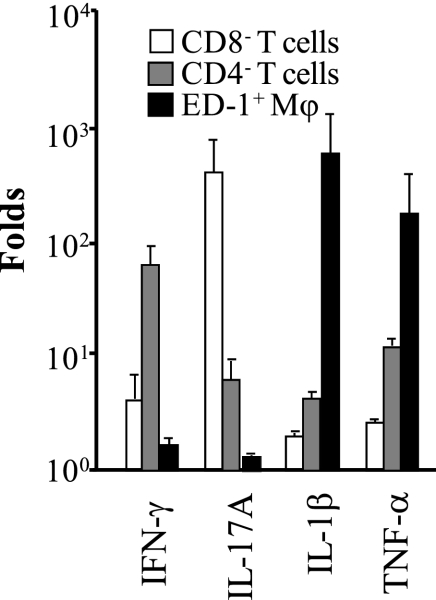

Cytokine mRNA profiles in isolated CD8− T cells, CD4− T cells, and ED-1+ macrophages from anti-GBM GN.

As shown in Fig. 10, IL-17A mRNA was predominantly expressed in the CD8− T-cell fraction (corresponding to CD4+ T cells) at levels 50.1-fold greater than those in CD4− T cells and 140.0-fold greater than those in ED-1+ macrophages. IFN-γ mRNA was predominantly expressed in the CD4− T-cell fraction (corresponding to CD8+ T cells) at levels 8.1-fold greater than those in CD8− T cells and 18.8-fold greater than ED-1+ macrophages. IL1-β and TNF-α were predominantly produced by the ED-1+ macrophages fraction, rather than the T-cell fraction.

Fig. 10.

Cytokine profiles in cells isolated from the vehicle group on day 7. To determine which cell populations expressed these cytokines, we isolated and fractionated the cells that had infiltrated the kidney using magnetic cell sorting. Open bar, CD8− T cells (corresponding to CD4+ T cells). Dotted bar, CD4− T cells (corresponding to CD8+ T cells). Hatched bar, ED-1+ macrophages. Isolated cells were analyzed for mRNA expression using real-time RT-PCR. Whole mononuclear cells isolated from untreated normal rat kidney (without the induction of anti-GBM GN) using the density gradient centrifugation method were used for calibration. Results are means ± SD for each group (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrated that numerous Kv1.3+ cells had infiltrated the kidneys of rats with anti-GBM GN. A flow cytometry analysis using a mononuclear cell suspension obtained from anti-GBM GN kidney revealed that most CD4+ T cells and some CD8+ T cells had a TEM phenotype (CD45RC−CD62L−). Double-immunofluorescent staining showed that Kv1.3 channels were highly expressed on CD3+ T cells and some ED-1+ macrophages (Fig. 4). Subsequently, we found that early treatment with a Kv1.3 blocker, Psora-4, reduced the numbers of CD3+ T cells and ED-1+ macrophages, glomerular crescent formation, and inflammatory cytokines and eventually restored renal function and reduced urinary protein excretion in anti-GBM GN. In addition, delayed Psora-4 treatment, which was started after crescent formation had been established, also reduced renal damage and restored renal function. Interestingly, while the total number of CD3+ T cells was reduced by Psora-4 treatment, the number of CCR7+ cells, which are expressed on TCM or TN, did not change. These results suggest that the Kv1.3 blocker Psora-4 may exert its immunosuppressive effect by selectively suppressing CCR7− TEM without affecting CCR7+ TN/TCM, as reported previously (10, 36). These findings indicated that Kv1.3-expressing TEM as well as some macrophages were responsible for the pathogenesis of anti-GBM GN and that Kv1.3 blocker may be useful for the treatment of patients with RPGN.

We showed that most of the T cells that had infiltrated the anti-GBM GN kidney tissues had a TEM phenotype and that these TEM expressed high mRNAs level of inflammatory cytokines. These TEM induced glomerular injury through a cytokine-secreting effector function, such as the secretion of IFN-γ during the early stage and of IL-17 during the late stage. TEM are essential mediators of numerous chronic inflammatory autoimmune diseases (10, 17, 54, 55). TEM exert an immediate effector function, which is achieved through the prompt secretion of large amounts of cytokines, such as IFN-γ or IL-4, at the site of antigen deposition and the initiation of a localized inflammatory immune response. A flow cytometry analysis of T cells in the urine of patients with IgA nephropathy, Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis, or ANCA-associated vasculitis showed that the urinary T cells mainly exhibited a TEM phenotype and expressed the mRNAs of the inflammatory cytokines IL-2 and IFN-γ (1, 44, 45). These TEM were also observed in and around the glomeruli, and the number of TEM was correlated with the degree of glomerular cell infiltration and crescent formation (45). In an experimental model, Totsuka and colleagues (18, 53) succeeded in inducing colitis by the adoptive transfer of only colitogenic CD4+ TEM into SCID mice (which do not contain any naïve T cells) and demonstrated a significant role of TEM in the development of colitis. In the field of kidney disease models, the infiltration of TEM-secreting IL-17 or IFN-γ was observed in the kidneys of unilateral ureteral obstruction (16) and ischemic reperfusion models (5).

Beside T cells, glomerular accumulation of macrophages is the striking feature in crescentic glomerulonephritis. Depletion studies (29, 47) have shown that macrophages can induce glomerular injury in experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis, suggesting that modulation of macrophage activation may be an important therapeutic strategy for the treatment of crescentic glomerulonephritis. Macrophages can produce many molecules that may cause renal damage. Macrophage-derived mediators, such as IL-1, TNF-α, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, and procoagulant activity, have been implicated in the development of crescent formation (6, 38). Administration of IL-1β and TNF-α exacerbates glomerular injury in anti-GBM GN, whereas blocking these cytokines suppresses the induction of glomerular injury (32, 50, 52).

Our results using whole kidney samples showed that the expressions of IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA, which were predominantly expressed on ED-1+ macrophages, were upregulated in the vehicle group and that Psora-4 significantly suppressed these increases. The time trend of IL-1β and TNF-α was paralleled with the number of ED-1+ macrophages in the anti-GBM kidney, suggesting that Psora-4 could have some effects on macrophages either directly or indirectly by modulating T-cell function. Our immunological study using fluorescent staining revealed that Kv1.3 channels were expressed on some, but not all, of the ED-1+ macrophages in anti-GBM GN kidney as well as CD3+ T cells (Fig. 4). A similar finding has been reported in a study examining the brain tissue of subjects with multiple sclerosis (43). Although Kv1.3 channels are present on T cells as well as on macrophages, B cells, and natural killer cells, the Kv1.3 channel only plays a dominant role in maintaining the resting membrane potential on TEM (12). At first, cells expressing Kv1.3 are sensitive to Kv1.3 blockers. However, with the exception of TEM, Kv1.3 inhibition can be rapidly escaped by the upregulation of other coexpressed potassium channels, as exemplified by the upregulation of KCa3.1 in TN and TCM (12, 59).

On the other hand, monocytes and macrophages express Kv1.5, the calcium-activated channels KCa1.1 and KCa3.1, and the inward-rectifier Kir2.1 in addition to Kv1.3 channels (11, 56). Especially, the association of Kv1.5 and Kv1.3 comprise the major voltage-dependent K+ channel in activated macrophages (11, 56). Macrophages express different Kv1.3-to-Kv1.5 ratios in cell type specification, leading to biophysically and pharmacologically distinct channels (58). High Kv1.3-to-Kv1.5 ratios, observed in bone marrow derived macrophages and TNF-α-activated Raw 264.7 macrophages, are sensitive to Kv1.3 blocker, whereas low Kv1.3-to-Kv1.5 ratios as observed in control Raw 264.7 macrophages have a low sensitivity to Kv1.3 blocker (57). The presence of Kv1.5 in macrophage lineage cells should be taken into account when designing Kv1.3-based therapies. Psora-4, a potent small-molecule Kv1.3 blocker (EC50 = 3 nM), is only 2.5-fold selective over the Kv1.5 channel (EC50 = 7.7 nM; Ref. 55), suggesting that Psora-4 may exert a direct inhibitory effect on some of the activated macrophages through the inhibition of the Kv1.3 and Kv1.5 channels, as well as an indirect effect on macrophages, through the suppression of T cells.

Several types of Kv channels, such as KCNQ1, KCNA10, and Kv1.3, are highly expressed at the apical membrane of renal tubules. Kv1.3 channels are reportedly expressed on the cortical collecting duct of the human kidney and may be involved in K+ secretion (61). Since serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase stimulates the activity of Kv1.3 channels (28), increases in the Kv channel activity induced by serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase may also contribute to aldosterone-mediated increases in K+ secretion. However, adverse effects, such as hyper-/hypokalemia, increases in serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, or morphological changes in the kidneys, have not been reported with the use of Kv1.3 blockers in rodent models (55). In a previous report (40), the acute and chronic administration of Kv1.3 blocker did not induce any apparent hematologic toxicity, and no marked fluctuations in the frequencies of the major T-cell lineages were noted, except for a temporary decrease in circulating lymphocytes with a coincident increase in neutrophils immediately after the administration of Kv1.3 blocker.

Kv1.3 blockers may have potential advantages over current immunomodulatory therapies with regard to several points. First, Kv1.3 blockers may not increase susceptibility to infections, because naïve and long-lived TCM (the main memory pool) would escape from its inhibition (10, 40). In addition, the Kv1.3 channel regulates glucose transporter type 4 trafficking in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue; therefore, Kv1.3 blockers are expected to be useful for the management of insulin resistance and diabetes (34).

The induction of anti-GBM GN increased the expression of the mRNAs of various inflammatory cytokines, and these increases were suppressed by Psora-4 treatment. IFN-γ is the most potent activator of mononuclear phagocytes and is predominantly secreted by natural killer and natural killer T cells as part of the innate immune response and by CD4+ and CD8+ effector T cells once antigen-specific immunity develops (46). However, the role of IFN-γ in anti-GBM GN remains controversial. Conflicting reports exist as to whether anti-GBM is ameliorated or exacerbated in IFN-γ gene knockout mice (33, 42). In anti-GBM GN, adoptive transfer of IFN-γ-activated macrophages substantially augmented macrophage-mediated renal injury (31). However, a consensus that IFN-γ is required for the induction of autoantibody formation and nephritis in lupus-prone mice has been established (26, 27). In our study, the IFN-γ mRNA level promptly increased on day 3 after the induction of anti-GBM GN, and IFN-γ was predominantly expressed in the CD4− T-cell fractions (corresponding to CD8+ T cells), indicating that IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells would be the major target of Psora-4 during the early stage of anti-GBM GN.

IL-17 has been defined as a proinflammatory cytokine and is produced by activated T cells (Th17). In humans, CD4+CD45RO+CCR7−CCR6+ TEM have been identified as the principal IL-17-secreting T cells under Th17-polarizing conditions (35). IL-17 is involved in the development of autoimmune disease models, such as experimental allergic encephalomyelitis, allergic contact dermatitis, and type II collagen-induced arthritis (4, 7, 49). Recently, both IL-23 p19−/− and IL-17−/− mice were reported to develop less severe nephritis as measured by renal function, proteinuria, and frequency of glomerular crescent formation (39). IL-17- and IFN-γ-producing CD3+ T cells were identified by intracellular cytokine staining after stimulation with PMA/ionomycin in the flow cytometric analysis of isolated renal T cells from nephritic wild-type mice, and IL-17 enhanced the production of the proinflammatory chemokines CCL2/MCP-1, CCL3/MIP-1α, and CCL20/LARC, which are implicated in the recruitment of T cells and monocytes, in mouse mesangial cells in vitro (39). In our real-time RT-PCR results, IL-17 mRNA was highly expressed on day 7 and was predominantly produced by the CD8− T-cell fraction (corresponding to CD4+ T cells). These increases were suppressed by Psora-4 treatment. Therefore, Psora-4 was suspected to exert its effect by suppressing IL-17-secreting CD4+ TEM.

In conclusion, the results of this study have demonstrated for the first time that the Kv1.3 blocker Psora-4 has effects in a rat model of anti-GBM GN that are likely mediated by inhibition of TEM and macrophages. If shown to be nontoxic in more detailed and long-term clinical toxicity tests, Psora-4 may become a very effective means of treating patients with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

GRANTS

The monoclonal antibody Kv1.3 was developed by and/or obtained from the University of California Davis/National Institutes of Health Neuromab Facility, supported by National Institutes of Health Grant U24NS050606, and maintained by the Department of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior, College of Biological Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Part of this study was presented at the American Society of Nephrology Meeting in 2007 (San Francisco, CA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdulahad WH, Kallenberg CG, Limburg PC, Stegeman CA. Urinary CD4+ effector memory T cells reflect renal disease activity in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 60: 2830–2838, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdulahad WH, Stegeman CA, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG. CD4-positive effector memory T cells participate in disease expression in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1107: 22–31, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando T, Wu H, Watson D, Hirano T, Hirakata H, Fujishima M, Knight JF. Infiltration of canonical Vgamma4/Vdelta1 gammadelta T cells in an adriamycin-induced progressive renal failure model. J Immunol 167: 3740–3745, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aranami T, Yamamura T. Th17 Cells and autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE/MS). Allergol Int 57: 115–120, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascon M, Ascon DB, Liu M, Cheadle C, Sarkar C, Racusen L, Hassoun HT, Rabb H. Renal ischemia-reperfusion leads to long term infiltration of activated and effector-memory T lymphocytes. Kidney Int 75: 526–535, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Song Q, Lan HY. Modulators of crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2271–2278, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azam P, Sankaranarayanan A, Homerick D, Griffey S, Wulff H. Targeting effector memory T cells with the small molecule Kv1.3 blocker PAP-1 suppresses allergic contact dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 127: 1419–1429, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beeton C, Pennington MW, Wulff H, Singh S, Nugent D, Crossley G, Khaytin I, Calabresi PA, Chen CY, Gutman GA, Chandy KG. Targeting effector memory T cells with a selective peptide inhibitor of Kv1.3 channels for therapy of autoimmune diseases. Mol Pharmacol 67: 1369–1381, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beeton C, Wulff H, Barbaria J, Clot-Faybesse O, Pennington M, Bernard D, Cahalan MD, Chandy KG, Beraud E. Selective blockade of T lymphocyte K(+) channels ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a model for multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13942–13947, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beeton C, Wulff H, Standifer NE, Azam P, Mullen KM, Pennington MW, Kolski-Andreaco A, Wei E, Grino A, Counts DR, Wang PH, LeeHealey CJ, S Andrews B, Sankaranarayanan A, Homerick D, Roeck WW, Tehranzadeh J, Stanhope KL, Zimin P, Havel PJ, Griffey S, Knaus HG, Nepom GT, Gutman GA, Calabresi PA, Chandy KG. Kv1.3 channels are a therapeutic target for T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 17414–17419, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blunck R, Scheel O, Muller M, Brandenburg K, Seitzer U, Seydel U. New insights into endotoxin-induced activation of macrophages: involvement of a K+ channel in transmembrane signaling. J Immunol 166: 1009–1015, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cahalan MD, Chandy KG. Ion channels in the immune system as targets for immunosuppression. Curr Opin Biotechnol 8: 749–756, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham MA, Huang XR, Dowling JP, Tipping PG, Holdsworth SR. Prominence of cell-mediated immunity effectors in “pauci-immune” glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 499–506, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decher N, Kumar P, Gonzalez T, Pirard B, Sanguinetti MC. Binding site of a novel Kv1.5 blocker: a “foot in the door” against atrial fibrillation. Mol Pharmacol 70: 1204–1211, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolff S, Abdulahad WH, van Dijk MC, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG, Bijl M. Urinary T cells in active lupus nephritis show an effector memory phenotype. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010May14 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong X, Bachman LA, Miller MN, Nath KA, Griffin MD. Dendritic cells facilitate accumulation of IL-17 T cells in the kidney following acute renal obstruction. Kidney Int 74: 1294–1309, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedrich M, Krammig S, Henze M, Docke WD, Sterry W, Asadullah K. Flow cytometric characterization of lesional T cells in psoriasis: intracellular cytokine and surface antigen expression indicates an activated, memory/effector type 1 immunophenotype. Arch Dermatol Res 292: 519–521, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujii R, Kanai T, Nemoto Y, Makita S, Oshima S, Okamoto R, Tsuchiya K, Totsuka T, Watanabe M. FTY720 suppresses CD4+CD44highCD62L− effector memory T cell-mediated colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G267–G274, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujinaka H, Yamamoto T, Feng L, Kawasaki K, Yaoita E, Hirose S, Goto S, Wilson CB, Uchiyama M, Kihara I. Crucial role of CD8-positive lymphocytes in glomerular expression of ICAM-1 and cytokines in crescentic glomerulonephritis of WKY rats. J Immunol 158: 4978–4983, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujinaka H, Yamamoto T, Takeya M, Feng L, Kawasaki K, Yaoita E, Kondo D, Wilson CB, Uchiyama M, Kihara I. Suppression of anti-glomerular basement membrane nephritis by administration of anti-monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 antibody in WKY rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1174–1178, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuta T, Hotta O, Horigome I, Chiba S, Noshiro H, Miyazaki M, Satoh M, Honda S, Taguma Y. Decreased CD4 lymphocyte count as a marker predicting high mortality rate in managing ANCA related rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Nephron 91: 601–605, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George Chandy K, Wulff H, Beeton C, Pennington M, Gutman GA, Cahalan MD. K+ channels as targets for specific immunomodulation. Trends Pharmacol Sci 25: 280–289, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grgic I, Wulff H, Eichler I, Flothmann C, Kohler R, Hoyer J. Blockade of T-lymphocyte KCa3.1 and Kv13 channels as novel immunosuppression strategy to prevent kidney allograft rejection. Transplant Proc 41: 2601–2606, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurney AM, Joshi S, Manoury B. KCNQ potassium channels: new targets for pulmonary vasodilator drugs? Adv Exp Med Biol 661: 405–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gutman GA, Chandy KG, Adelman JP, Aiyar J, Bayliss DA, Clapham DE, Covarriubias M, Desir GV, Furuichi K, Ganetzky B, Garcia ML, Grissmer S, Jan LY, Karschin A, Kim D, Kuperschmidt S, Kurachi Y, Lazdunski M, Lesage F, Lester HA, McKinnon D, Nichols CG, O'Kelly I, Robbins J, Robertson GA, Rudy B, Sanguinetti M, Seino S, Stuehmer W, Tamkun MM, Vandenberg CA, Wei A, Wulff H, Wymore RS. International Union of Pharmacology. XLI. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev 55: 583–586, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haas C, Ryffel B, Le Hir M. IFN-gamma is essential for the development of autoimmune glomerulonephritis in MRL/Ipr mice. J Immunol 158: 5484–5491, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas C, Ryffel B, Le Hir M. IFN-gamma receptor deletion prevents autoantibody production and glomerulonephritis in lupus-prone (NZB × NZW)F1 mice. J Immunol 160: 3713–3718, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henke G, Maier G, Wallisch S, Boehmer C, Lang F. Regulation of the voltage gated K+ channel Kv1.3 by the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2 and the serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase SGK1. J Cell Physiol 199: 194–199, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holdsworth SR, Neale TJ, Wilson CB. Abrogation of macrophage-dependent injury in experimental glomerulonephritis in the rabbit. Use of an antimacrophage serum. J Clin Invest 68: 686–698, 1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang XR, Tipping PG, Apostolopoulos J, Oettinger C, D'Souza M, Milton G, Holdsworth SR. Mechanisms of T cell-induced glomerular injury in anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) glomerulonephritis in rats. Clin Exp Immunol 109: 134–142, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikezumi Y, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Interferon-gamma augments acute macrophage-mediated renal injury via a glucocorticoid-sensitive mechanism. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 888–898, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karkar AM, Tam FW, Steinkasserer A, Kurrle R, Langner K, Scallon BJ, Meager A, Rees AJ. Modulation of antibody-mediated glomerular injury in vivo by IL-1ra, soluble IL-1 receptor, and soluble TNF receptor. Kidney Int 48: 1738–1746, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitching AR, Holdsworth SR, Tipping PG. IFN-gamma mediates crescent formation and cell-mediated immune injury in murine glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 752–759, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Wang P, Xu J, Desir GV. Voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 regulates GLUT4 trafficking to the plasma membrane via a Ca2+-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C345–C351, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Rohowsky-Kochan C. Regulation of IL-17 in human CCR6+ effector memory T cells. J Immunol 180: 7948–7957, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matheu MP, Beeton C, Garcia A, Chi V, Rangaraju S, Safrina O, Monaghan K, Uemura MI, Li D, Pal S, de la Maza LM, Monuki E, Flugel A, Pennington MW, Parker I, Chandy KG, Cahalan MD. Imaging of effector memory T cells during a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction and suppression by Kv1.3 channel block. Immunity 29: 602–614, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakagawa R, Nagafune I, Tazunoki Y, Ehara H, Tomura H, Iijima R, Motoki K, Kamishohara M, Seki S. Mechanisms of the antimetastatic effect in the liver and of the hepatocyte injury induced by alpha-galactosylceramide in mice. J Immunol 166: 6578–6584, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Atkins RC. The role of macrophages in glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16, Suppl 5: 3–7, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paust HJ, Turner JE, Steinmetz OM, Peters A, Heymann F, Holscher C, Wolf G, Kurts C, Mittrucker HW, Stahl RA, Panzer U. The IL-23/Th17 axis contributes to renal injury in experimental glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 969–979, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pereira LE, Villinger F, Wulff H, Sankaranarayanan A, Raman G, Ansari AA. Pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and functional studies of the selective Kv1.3 channel blocker 5-(4-phenoxybutoxy)psoralen in rhesus macaques. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 232: 1338–1354, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pipkin ME, Rao A. SnapShot: effector and memory T cell differentiation. Cell 138: 606 e601–602, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ring GH, Dai Z, Saleem S, Baddoura FK, Lakkis FG. Increased susceptibility to immunologically mediated glomerulonephritis in IFN-gamma-deficient mice. J Immunol 163: 2243–2248, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rus H, Pardo CA, Hu L, Darrah E, Cudrici C, Niculescu T, Niculescu F, Mullen KM, Allie R, Guo L, Wulff H, Beeton C, Judge SI, Kerr DA, Knaus HG, Chandy KG, Calabresi PA. The voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 is highly expressed on inflammatory infiltrates in multiple sclerosis brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11094–11099, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakatsume M, Gejyo F. Effector T cells and macrophages in urine as a hallmark of systemic vasculitis accompanied by crescentic glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 607–609, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakatsume M, Xie Y, Ueno M, Obayashi H, Goto S, Narita I, Homma N, Tasaki K, Suzuki Y, Gejyo F. Human glomerulonephritis accompanied by active cellular infiltrates shows effector T cells in urine. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2636–2644, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schoenborn JR, Wilson CB. Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv Immunol 96: 41–101, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schreiner GF, Cotran RS, Pardo V, Unanue ER. A mononuclear cell component in experimental immunological glomerulonephritis. J Exp Med 147: 369–384, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seder RA, Ahmed R. Similarities and differences in CD4+ and CD8+ effector and memory T cell generation. Nat Immunol 4: 835–842, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shahrara S, Huang Q, Mandelin AM, 2nd, Pope RM. TH-17 cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthriris Res Ther 10: R93, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang WW, Feng L, Vannice JL, Wilson CB. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist ameliorates experimental anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody-associated glomerulonephritis. J Clin Invest 93: 273–279, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tipping PG, Holdsworth SR. T cells in crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1253–1263, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tomosugi NI, Cashman SJ, Hay H, Pusey CD, Evans DJ, Shaw A, Rees AJ. Modulation of antibody-mediated glomerular injury in vivo by bacterial lipopolysaccharide, tumor necrosis factor, and IL-1. J Immunol 142: 3083–3090, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Totsuka T, Kanai T, Iiyama R, Uraushihara K, Yamazaki M, Okamoto R, Hibi T, Tezuka K, Azuma M, Akiba H, Yagita H, Okumura K, Watanabe M. Ameliorating effect of anti-inducible costimulator monoclonal antibody in a murine model of chronic colitis. Gastroenterology 124: 410–421, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varela-Calvino R, Ellis R, Sgarbi G, Dayan CM, Peakman M. Characterization of the T-cell response to coxsackievirus B4: evidence that effector memory cells predominate in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 51: 1745–1753, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vennekamp J, Wulff H, Beeton C, Calabresi PA, Grissmer S, Hansel W, Chandy KG. Kv1-blocking 5-phenylalkoxypsoralens: a new class of immunomodulators. Mol Pharmacol 65: 1364–1374, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vicente R, Escalada A, Coma M, Fuster G, Sanchez-Tillo E, Lopez-Iglesias C, Soler C, Solsona C, Celada A, Felipe A. Differential voltage-dependent K+ channel responses during proliferation and activation in macrophages. J Biol Chem 278: 46307–46320, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vicente R, Escalada A, Villalonga N, Texido L, Roura-Ferrer M, Martin-Satue M, Lopez-Iglesias C, Soler C, Solsona C, Tamkun MM, Felipe A. Kv1.5 association of Kv1.3 contributes to the major voltage-dependent K+ channel in macrophages. J Biol Chem 281: 37675–37685, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Villalonga N, Escalada A, Vicente R, Sanchez-Tillo E, Celada A, Solsona C, Felipe Kv A.3/Kv1.5. heteromeric channels compromise pharmacological responses in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 352: 913–918, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wulff H, Calabresi PA, Allie R, Yun S, Pennington M, Beeton C, Chandy KG. The voltage-gated Kv1.3 K(+) channel in effector memory T cells as new target for MS. J Clin Invest 111: 1703–1713, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wuttke TV, Lerche H. Novel anticonvulsant drugs targeting voltage-dependent ion channels. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 15: 1167–1177, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yao X, Chang AY, Boulpaep EL, Segal AS, Desir GV. Molecular cloning of a glibenclamide-sensitive, voltage-gated potassium channel expressed in rabbit kidney. J Clin Invest 97: 2525–2533, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshida M, Nakata M, Yamato S, Dezaki K, Sugawara H, Ishikawa SE, Kawakami M, Yada T, Kakei M. Voltage-dependent metabolic regulation of Kv2.1 channels in pancreatic beta-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 396: 304–309, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]