Abstract

Acute intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl, used to simulate a high-salt diet-induced increase of medullary osmolality, increases urine production and endothelin release from the kidney. To determine whether endothelin mediates this diuretic and natriuretic response, urine flow and Na+ excretion rate were measured during acute intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl in anesthetized rats, with or without endothelin receptor antagonism. Isosmotic NaCl was infused into the left renal medulla during an equilibration period and 30-min baseline period, followed by hyperosmotic NaCl for two additional 30-min periods. Hyperosmotic NaCl infusion significantly increased urine flow of vehicle-treated rats (from 5.9 ± 0.9 to 11.1 ± 1.8 μl/min). Systemic ETB receptor blockade enhanced this effect (A-192621; from 7.7 ± 1.1 to 18.7 ± 2.9 μl/min; P < 0.05), ETA receptor blockade (ABT-627) had no significant effect alone, but the diuresis was markedly attenuated by combined ABT-627 and A-192621 administration (from 4.4 ± 0.7 to 5.4 ± 0.9 μl/min). Mean arterial pressures overall were not significantly different between groups. Surprisingly, the natriuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion was not significantly altered by systemic endothelin receptor blockade, and furthermore, intramedullary ETB receptor blockade enhanced the diuretic and natriuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion. ETA receptor blockade significantly attenuated both the diuretic and natriuretic responses to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion in ETB receptor-deficient sl/sl rats. These results demonstrate an important role of endothelin in mediating diuretic responses to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl. Moreover, these data suggest ETA and ETB receptors are both required for the full diuretic and natriuretic actions of endothelin.

Keywords: salt and water excretion, blood pressure, kidney, endothelin

the renal endothelin system is important for control of salt and water excretion, and in particular for maintenance of normal blood pressure during high-salt intake. Urinary endothelin excretion, which reflects renal endothelin production (2), is increased by high-salt intake in rodents (3, 26) and correlates with sodium excretion in humans (17). In the healthy kidney, endothelin is thought to act as a diuretic and natriuretic agent, via inhibition of tubular Na+ and Cl− transport (6, 8, 11, 25, 37), inhibition of vasopressin-induced water reabsorption by the collecting duct (21, 24, 30, 31), and possibly via ETB receptor-mediated increases in medullary blood flow (15, 32), which is proposed to have a pronatriuretic effect (7). The majority of the diuretic and natriuretic effects of endothelin appear to be mediated by the ETB receptor, and impairment of ETB receptor function at the whole animal level (10, 26) or specifically in the collecting duct (12) causes salt-sensitive hypertension. Together, these data suggest that high-salt intake triggers an increase in renal endothelin production, which in turn acts on ETB receptors to produce a natriuretic and diuretic response, thereby facilitating excretion of excess sodium. However, work from Kohan's laboratory (13) suggests that both ETA and ETB receptors within the collecting duct operate in a possible synergistic manner to facilitate excretion of salt and water. These findings have been supported by more recent results from our own laboratory demonstrating that both ETA and ETB receptors contribute to the natriuretic response to intramedullary infusion of ET-1 in female rats (23).

The mechanism by which high-salt intake increases renal ET-1 production is still under investigation, but one possible signal is a change in medullary osmolality and/or associated increases in tubular flow rate. Outer medullary osmolality and tubular flow rate are increased by high-salt intake (16), and increases of culture media osmolality have been shown to stimulate endothelin release from medullary thick limb and collecting duct cells in some studies (16, 36) but not others (20). We previously demonstrated that exposing the renal medulla of rats to a hyperosmotic NaCl solution enhanced endothelin release in vivo (increased urinary endothelin excretion) (5). This enhanced endothelin release was accompanied by natriuresis and diuresis (5), consistent with the hypothesis that high-salt intake increases medullary osmolality, stimulating an increase in endothelin production and release, which facilitates excretion of the salt load. However, it has been suggested that increased luminal flow might act as a stimulus for endothelin release from collecting duct cells via a primary cilium Ca2+-dependent mechanism (27). It therefore remains to be determined whether the endothelin released in response to intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion plays an active role in mediating the diuretic and natriuretic response or merely occurs secondary to increased luminal flow generated by some other mechanism.

The current study therefore sought to determine whether endothelin actively contributes to the diuretic and natriuretic response to intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion, and to ascertain which endothelin receptor subtype is involved in mediating the response.

METHODS

General procedures.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 6–11 per group; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) and wild-type (WT) transgenic and ETB receptor-deficient (sl/sl) rats (n = 7–10, bred in-house) were used in these experiments (10). All protocols were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved in advance by the Medical College of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The surgical procedures were similar to our previous study (5). Rats were fasted overnight and then anesthetized (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; 100 mg/kg ip thiobutabarbitone), placed on a heating table to maintain body temperature at 37°C throughout the experiment, and a tracheotomy was performed to facilitate breathing. A catheter was inserted into the jugular vein and 6.2% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered NaCl was infused at 6 ml/h to 1.25% of the rat's body weight, followed thereafter by 0.9% NaCl at 1.5 ml/h to replace fluids lost and maintain euvolemia. Mean arterial pressure was measured via a catheter inserted into a femoral artery, with data recorded using a PowerLab data acquisition system. A midline incision was made and a stretched PE10 catheter was inserted 5 mm into the left kidney. Positioning of the catheter tip at the outer-inner medullary junction was confirmed at the end of each experiment by dissection. Once the catheter was in place, 0.9% (isosmotic) NaCl was infused directly into the renal medulla (0.5 ml/h). Urine was collected separately from the left (infused) and right (untouched) kidneys via catheters placed in each ureter. We found previously (5) that the effects of renal medullary interstitial infusion of hypertonic substances are largely confined to the kidney receiving the infusion, with very little to no effect on urine flow or sodium excretion observed in the contralateral kidney. Isosmotic (154 mM, or 284 mosmol/kgH2O) NaCl was infused into the renal medullary interstitium during the 1-h postsurgery stabilization period and 30-min baseline urine collection period. This was followed by two further 30-min urine collection periods during which rats either continued to receive isosmotic NaCl or the infusion was switched to hyperosmotic NaCl (0.9 M, or 1,669 mosmol/kgH2O measured by freezing point depression). Urine samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Role of endothelin in response to hyperosmotic NaCl.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized to one of four systemic treatment groups, with drugs being administered as an intravenous bolus (0.5 ml/kg via jugular vein catheter) 30 min before the end of the 1-h postsurgery stabilization period: 1) vehicle, 2) the selective ETB receptor antagonist A-192621 (10 mg/kg), 3) the selective ETA antagonist ABT-627 (5 mg/kg), or 4) A-192621 plus ABT-627 (both kindly provided by Abbott Laboratories). These doses are as high or higher than those administered previously in our laboratory (32) and by others (4). Urine was collected for 30-min periods at baseline (intramedullary infusion of isosmotic NaCl in all rats) and for two subsequent 30-min periods (isosmotic or hyperosmotic NaCl). At the completion of the experiment, a 0.3-nmol/kg bolus of ET-1 (American Peptide, Sunnyvale, CA) was given intravenously and the maximum decrease and increase in blood pressure were measured to verify appropriate receptor blockade. A-192621 alone or in combination with ABT-627 completely abolished the transient depressor response to ET-1 at 0.3 nmol/kg, which was on average −42 ± 2 mmHg in vehicle-treated rats. ABT-627 alone had no significant effect on the transient depressor response (−37 ± 2 mmHg), but when given alone or in combination with A-192621 significantly (P < 0.05) reduced the pressor response (to +11 ± 1 and +6 ± 1 mmHg, respectively) compared with the response in vehicle-treated rats (+18 ± 1 mmHg). A-192621 significantly enhanced the pressor response to ET-1 (to +44 ± 3 mmHg, P < 0.05). These findings are consistent with the antagonist treatments providing significant blockade of the intended endothelin receptors, for which the antagonists each show >1,000-fold selectivity for their targeted endothelin receptor subtype over the other subtype (33).

To further test the role of the ETB receptor in mediating the response to intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion, additional groups of rats underwent intramedullary NaCl solution infusions as described above, with or without the selective ETB receptor antagonist BQ-788 (EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA) included in the intramedullary infusion at 7 nmol/min. This dose of BQ-788 was identical to that administered via the renal artery previously by Just and colleagues (18) who observed complete blockade of ETB-dependent effects.

In separate experiments, male ETB receptor-deficient sl/sl rats and WT littermates underwent identical procedures to those described above but were either treated with vehicle or ABT-627 30 min before the end of the 1-h equilibration period and received intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl for the final two 30-min urine collection periods. In addition, an adjustable ligature was placed around the aorta proximal to the renal arteries, enabling renal perfusion pressure (estimated as femoral arterial pressure) to be held constant at normotensive levels in all four groups. This measure was taken to preclude differences in arterial pressure confounding interpretation of results in ETB-deficient sl/sl rats, which display substantial reductions in blood pressure following ETA receptor blockade.

Role of endothelin in response to hyperosmotic mannitol.

To further investigate whether endothelin plays a role in mediating the diuretic response to increased medullary osmolality, separate groups of male Sprague-Dawley rats received intramedullary infusions of isosmotic (0.3 M, or 297 mosmol/kgH2O) and hyperosmotic (1.6 M, or 1,496 mosmol/kgH2O) mannitol solutions with and without pretreatment with ABT-627 plus A-192621 for the same time periods as described above.

Assays.

Osmolality of infused solutions was determined by freezing point depression (μOsmette model 5004 Automatic Osmometer, Precision Systems, Natick, MA). Urine electrolyte concentrations were determined by ion-sensitive electrodes (Synchron EL-ISE, Beckman Instruments, Brea, CA). Urine flow was determined gravimetrically.

Statistical analysis.

Data from the three 30-min collection periods were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA with (Bonferroni) post hoc contrasts used when Pgroup*time < 0.05. All other data were analyzed by one-factor ANOVA. A two-tailed Dunnett post hoc test was used to compare maximal pressor responses to ET-1 between vehicle and endothelin receptor antagonist-treated groups. Values are presented as means ± SE, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Excretory response to hyperosmotic NaCl during endothelin receptor blockade.

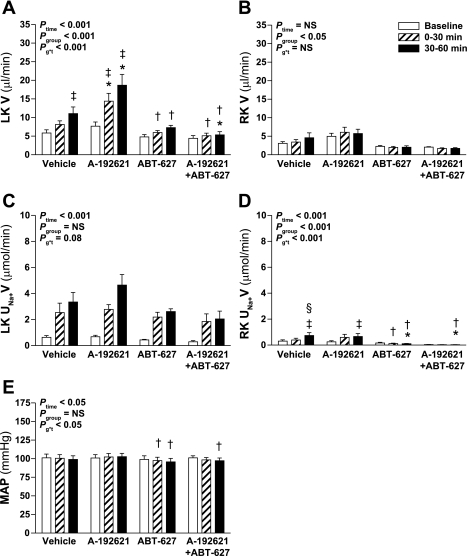

Intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion produced a significant increase in urine flow from the left (infused) kidney of Sprague-Dawley rats (Ptime < 0.001; Fig. 1A). Unexpectedly, pretreatment with the selective ETB receptor antagonist A-192621 significantly enhanced the diuretic response, whereas selective ETA receptor blockade with ABT-627 did not significantly alter the response compared with vehicle pretreatment. Pretreatment with both A-192621 and ABT-627 significantly attenuated the diuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion. There was no effect of hyperosmotic NaCl infusion on urine flow of the right (untouched) kidney (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effect of endothelin receptor blockade on response to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl into the left kidney (LK) of anesthetized rats. Data shown are urine flow (V; A and B) and Na+ excretion rate (UNa+V; C and D) for the LK (A and C) and right kidney (RK; B and D) and mean arterial pressure (MAP; E) measured during sequential 30-min periods in rats receiving intramedullary infusions of isosmotic (284 mosmol/kgH2O) NaCl at baseline followed by infusion of NaCl at 1,669 mosmol/kgH2O (n = 8, 7, 7, and 6 for vehicle, A-192621, ABT-627, and A-192621 + ABT-627 pretreatment groups, respectively). Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to test whether responses were affected by group (Pgroup), or time (Ptime), and whether responses differed between groups in a time-dependent manner (Pg*t). NS, not statistically significant. Post hoc contrasts: *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle for same time point; †P < 0.05 vs. A-192621 group at specified time point; ‡P < 0.05 vs. baseline in same group; §P < 0.05 vs. previous time point in same group.

The increase in Na+ excretion from the left kidney in response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion followed a similar pattern as urine flow, i.e., increased in response to infusion, although there were no statistically significant differences between antagonist-treated groups and control (Fig. 1C). Left kidney urine osmolality was measured where sample volume allowed, yielding n = 4–7 per time point in each group. There was no significant change in urine osmolality over time (Ptime = 0.4), although osmolality was significantly lower in A-192621-treated rats throughout the experiment compared with the other three groups (P < 0.05; data not shown). The right, noninfused kidney displayed significant increases in Na+ excretion only in the vehicle- and A-192621-treated rats (P < 0.05; Fig. 1D), but these changes were very small compared with the effects observed on the left (infused) kidney (Fig. 1C). Overall, mean arterial pressures were not significantly different between the four groups (Pgroup = 0.9), ranging between 96 ± 5 and 103 ± 5 mmHg (Fig. 1E). The only minor but statistically significant differences in mean arterial pressures were between A-192621-treated and the two other endothelin receptor antagonist-treated groups at certain time points (P < 0.05 by post hoc contrast; Fig. 1E); however, there was no difference in mean arterial pressure between these and the vehicle group at any time.

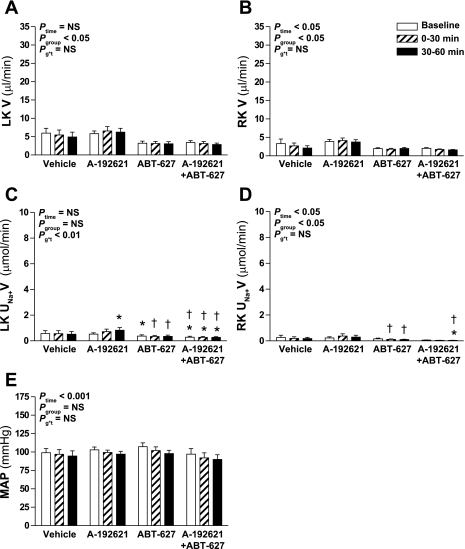

In rats receiving infusion of isosmotic NaCl into the medullary interstitium of the left kidney, urine flow from the left kidney did not change over time but was at slightly but significantly different levels between groups (Fig. 2A). Overall, there was a significant decrease in urine flow from the right kidney over time (Ptime < 0.05; Fig. 2B), but this effect was not significantly different between the four groups (Pgroup*time > 0.05). Although there was no overall difference in Na+ excretion by the left or right kidneys between the four groups (Pgroup > 0.2), there were some small but statistically significant differences between particular groups at specific time points as indicated in Fig. 2, C and D. However, it should be noted that Na+ excretion did not change significantly over time either overall (Ptime > 0.2), nor within any of the four groups by post hoc contrast. Mean arterial pressure decreased slightly but significantly over time to a similar degree in all four groups (Ptime < 0.001; Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Effect of endothelin receptor blockade on response to intramedullary infusion of isosmotic NaCl into the LK of anesthetized rats. Data shown are V (A and B) and UNa+V (C and D) for the LK (A and C) and RK (B and D) and MAP (E) measured during sequential 30-min periods in rats receiving intramedullary infusions of isosmotic (284 mosmol/kgH2O) NaCl (n = 6, 6, 7, and 6 for vehicle, A-192621, ABT-627, and A-192621 + ABT-627 pretreatment groups, respectively). Statistical analyses are as per Fig. 1. Post hoc contrasts: *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle for same time point; †P < 0.05 vs. A-192621 group at specified time point.

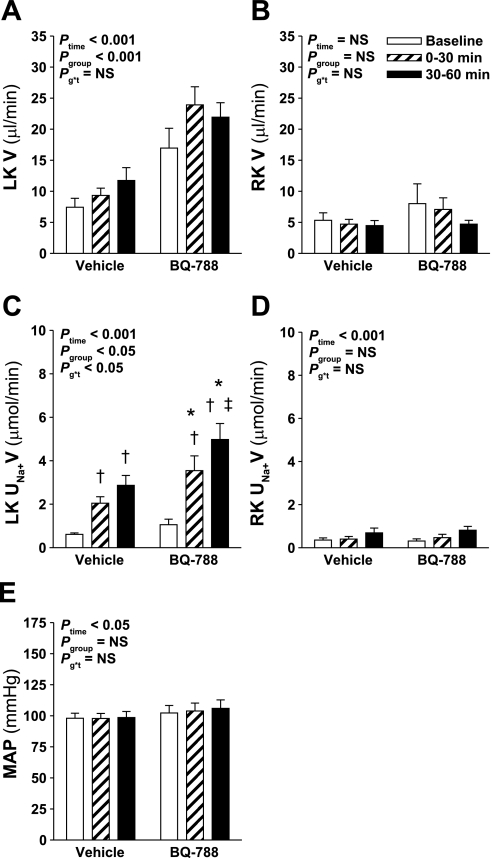

As an additional approach to determining whether ETB receptor blockade enhanced the diuretic and natriuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion, separate groups of rats received intramedullary infusions of NaCl with or without the selective ETB receptor antagonist BQ-788 being included in the infused solution. BQ-788 was included in the infusate commencing 30 min before the beginning of the baseline collection period. Similar to rats treated intravenously with the ETB receptor antagonist A-192621, intramedullary ETB receptor blockade with BQ-788 increased urine flow and also enhanced the natriuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion in the left kidney (Fig. 3, A and C). There was no difference in urine flow or Na+ excretion from the right kidney, or in mean arterial pressure between the two groups, although right kidney Na+ excretion and mean arterial pressure increased slightly but significantly over time in both groups (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of intramedullary ETB receptor blockade on the response to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl into the LK of anesthetized rats. Data shown are V (A and B) and UNa+V (C and D) for the LK (A and C) and RK (B and D) and MAP (E) measured during sequential 30-min periods in rats receiving intramedullary infusions of isosmotic (284 mosmol/kgH2O) NaCl at baseline followed by infusion of hyperosmotic (1,669 mosmol/kgH2O) NaCl for 2 further 30-min periods. In rats receiving BQ-788, BQ-788 was included in the isosmotic and hyperosmotic NaCl solutions at a concentration to give 7 nmol/min commencing 30 min before the beginning of the baseline collection period; n = 8–11 per group. Statistical analyses are as per Fig. 1. Post hoc contrasts: *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle for the same time point; †P < 0.05 vs. baseline in same group; ‡P < 0.05 vs. previous time point in same group.

Intramedullary NaCl in ETB receptor-deficient rats.

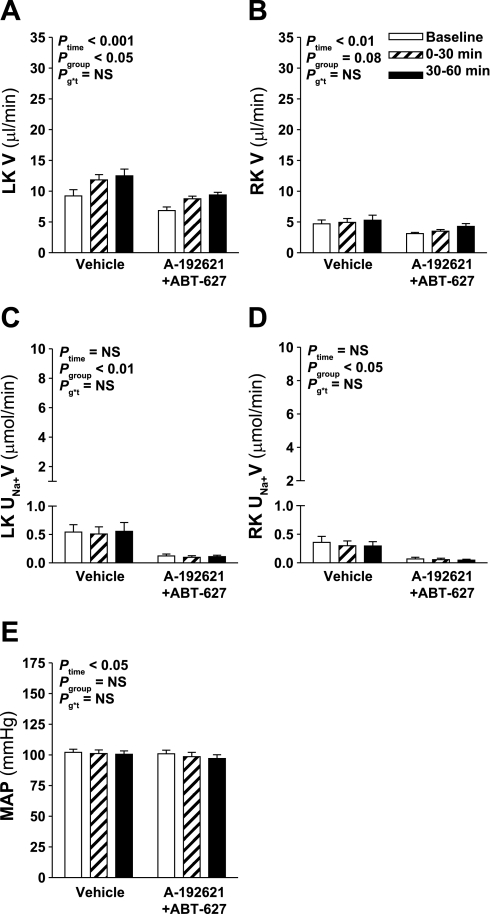

The results described above revealed a surprising effect of ETB receptor blockade to enhance the diuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion. In addition, these results suggest that rather than ETB receptors alone mediating the diuretic and natriuretic actions of endothelin in male rats, ETA and ETB receptors cooperate to facilitate salt and water excretion. To further examine the role of the ETB receptor and to test whether ETA receptors can indeed mediate diuretic and natriuretic responses, the effect of ETA receptor blockade on the response to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl was examined in WT and ETB receptor-deficient sl/sl rats. The ETB receptor-deficient sl/sl rat lacks functional ETB receptor expression other than that provided by a transgene containing a functional ETB receptor expressed under the control of the dopamine β-hydroxylase promoter and does not express detectable levels of ETB receptor mRNA in renal tubules or vasculature (10). Although the diuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion into the left kidney was not significantly affected by ABT-627 (Pgroup*time = 0.2), urine flow from the left kidney was significantly lower in ABT-627-treated WT rats across the experiment (Pgroup < 0.05; Fig. 4A). Similar to Sprague-Dawley rats (Fig. 1C), ABT-627 had no significant effect on the natriuretic response to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl in WT rats (Fig. 4C). Urine flow from the right kidney was significantly lower in ABT-627-treated WT rats compared with vehicle-treated WT rats but urine flow did not change over time in either group (Fig. 4B). The right, noninfused kidney displayed significant increases in Na+ excretion only in the vehicle-treated rats, and only during the final 30-min period (Fig. 4D), but this was again a much smaller effect than that observed on the left kidney (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Effect of ETA receptor blockade on the response to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl in wild-type (WT) rats. Data shown are V (A and B) and UNa+V (C and D) for the LK (A and C) and RK (B and D) and MAP (E) measured during sequential 30-min periods in rats receiving intramedullary infusions of isosmotic NaCl at baseline followed by infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl for 2 further 30-min periods; n = 8–10 per group. Statistical analyses are as per Fig. 1. Post hoc contrasts: *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle for the same time point; †P < 0.05 vs. baseline in same group; ‡P < 0.05 vs. previous time point in same group.

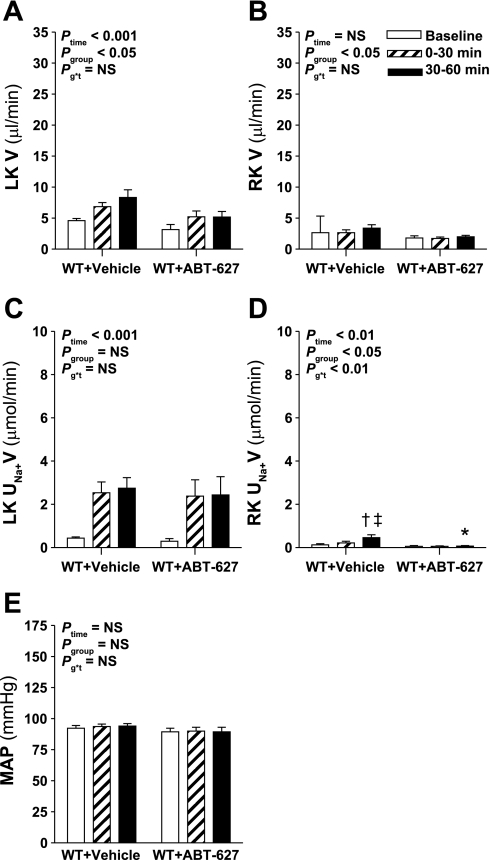

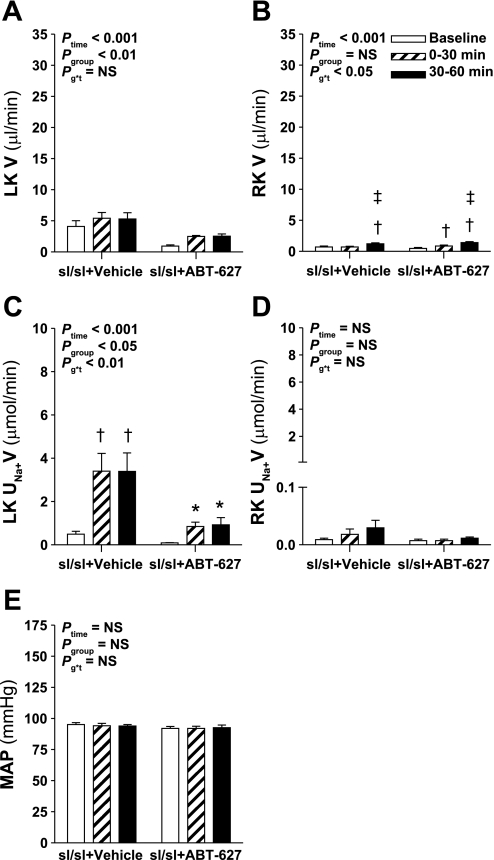

In contrast to pharmacological studies, ETB receptor-deficient rats did not display an exaggerated response to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl (Fig. 5, A and C). ETA receptor blockade in ETB receptor-deficient rats produced a reduction in urine flow from the left kidney across the three urine collection periods (Pgroup < 0.01; Fig. 5A) and significantly attenuated the natriuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion (Fig. 5C). The effects of ABT-627 on the diuretic and natriuretic responses to intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion occurred independent of any change in renal perfusion pressure, which was maintained constant and equal between the two groups by means of the adjustable ligature placed around the aorta (Fig. 5E). Over the course of the experiment, both groups displayed small but statistically significant increases in urine flow but not Na+ excretion from the right kidney (Fig. 5, B and D).

Fig. 5.

Effect of ETA receptor blockade on the response to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl in ETB receptor-deficient (sl/sl) rats. Data shown are V (A and B) and UNa+V (C and D) for the LK (A and C) and RK (B and D) and MAP (E) measured during sequential 30-min periods in rats receiving intramedullary infusions of isosmotic NaCl at baseline followed by infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl for 2 further 30-min periods; n = 7 per group. Statistical analyses are as per Fig. 1. Post hoc contrasts: *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle for same time point; †P < 0.05 vs. baseline in same group; ‡P < 0.05 vs. previous time point in same group.

Intramedullary hyperosmotic mannitol infusion.

To further investigate the role of endothelin in mediating diuresis, urine flow and Na+ excretion were measured in Sprague-Dawley rats receiving intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic mannitol with and without pretreatment with ABT-627 plus A-192621. When given alone, hyperosmotic mannitol produced a significant diuresis (Ptime < 0.001; Fig. 6A), but not natriuresis (Fig. 6C). Both urine flow and Na+ excretion rate were significantly reduced by combined ETA and ETB receptor blockade (Pgroup < 0.05; Fig. 6) without inducing a significant difference in mean arterial pressure between groups (Pgroup > 0.05; Fig. 6E), indicating an important role for endothelin in mediating Na+ and water excretion.

Fig. 6.

Effect of combined ETA and ETB receptor blockade on the response to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic mannitol into the LK of anesthetized rats. Data shown are V (A and B) and UNa+V (C and D) for the LK (A and C) and RK (B and D) and MAP (E) measured during sequential 30-min periods in rats receiving intramedullary infusions of isosmotic mannitol (297 mosmol/kgH2O) at baseline followed by infusion of hyperosmotic mannitol (1,496 mosmol/kgH2O) for 2 further 30-min periods; n = 10–11 per group. Statistical analyses are as per Fig. 1.

DISCUSSION

The hypothesis that changes in medullary osmolality may act as a control mechanism for renal endothelin production has been studied both in vitro by others (16, 20, 36), and more recently, in vivo by our group (5). We previously demonstrated that intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl increases urinary excretion of endothelin (5), suggesting that an increase in medullary osmolality, which has been reported to occur during high-salt intake (16), acts as a stimulus for endothelin release. The current study extends this finding, demonstrating that endothelin plays a critical role in the diuretic response induced by intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion.

The finding that endothelin participates in the diuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion, rather than urinary endothelin excretion merely increasing secondarily to increased urine flow, is not surprising given the reported pronatriuretic and -diuretic actions of this peptide. What was surprising is that ETB receptor blockade either systemically with A-192621 or locally with BQ-788 enhanced rather than attenuated the response to intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion. This finding is in contrast to the well-established role for ETB receptors functioning in a diuretic and natriuretic manner and so the mechanism for this effect is not evident. An alteration of reno-renal reflex sensitivity by ETB receptor blockade would not provide an explanation for this finding, since blocking ETB receptors in our study would be predicted to impair renal afferent nerve-induced inhibition of sympathetic outflow to the kidney (22). Moreover, urine flow from the right kidney did not change over the course of the experiment in either A-192621- or BQ-788-treated rats (Figs. 1B and 3B). Curiously, chronic lack of functional ETB receptors in sl/sl rats did not enhance the diuretic response to intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion. While on the one hand, this, too, is somewhat puzzling, the difference between pharmacological and genetic ablation of ETB receptors may be consistent with sl/sl rats having adapted to high levels of circulating ET-1 (10), whereas the acute blockade of ETB receptors in normal rats may produce an abrupt increase in ET-1 availability due to reduced binding to the ETB receptor (9), leading to enhanced activation of what appears to be prodiuretic ETA receptors. It is also possible that the smaller diuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion in the ETB-deficient rats compared with A-192621-treated Sprague-Dawley rats may be a consequence of the use of an adjustable clamp to equalize renal perfusion pressure between WT and ETB-deficient rats, thus shifting the ETB receptor-deficient rats down their pressure-natriuresis/diuresis curves.

Until recently (23), most data pointed toward anti-natriuretic and anti-diuretic actions of ETA receptors in the kidney. Activation of ETA receptors promotes renal vasoconstriction (18), and in the renal pelvis, ETA receptors suppress renal afferent sensory nerve activity, consequently promoting anti-natriuretic and anti-diuretic efferent sympathetic neural influences on the kidney (22). In addition, conditional knockout technology revealed that collecting duct ETA receptors enhance the anti-diuretic effect of vasopressin (14). In the current study, however, blockade of both ETA and ETB receptors clearly attenuated the diuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion in male Sprague-Dawley rats, and blockade of the ETA receptor in WT and ETB receptor-deficient rats also reduced urine flow independently of any effect on blood pressure. This effect of ABT-627 on urine flow did not reach statistical significance in Sprague-Dawley rats, possibly due to the analysis being underpowered to detect this effect. Together, these data indicate a role for the ETA receptor in promoting water excretion, a property that may become more obvious under conditions of abrogation of ETB receptor function, either by pharmacological or genetic means. Moreover, the diuretic properties of the ETA receptor run counter to the prevailing dogma that renal medullary ETB receptors are primarily responsible for the diuretic and natriuretic actions of endothelins while renal medullary ETA receptors do not promote Na+ and water excretion (1, 14, 19). Nonetheless, our findings across the different experimental groups suggest a cooperative role for the two endothelin receptors in control of urine flow, and perhaps of sodium excretion as well.

Recently, an ETA receptor nitric oxide synthase type 1 (NOS1)-dependent diuretic and natriuretic response to intramedullary ET-1 infusion was uncovered by our group in female but not male rats, with this response being particularly pronounced in female ETB receptor-deficient sl/sl rats (23). Our current data are consistent with ETA receptors also being capable of mediating the diuretic and natriuretic actions of endothelin in male rats, with ETB receptor blockade paradoxically enhancing diuresis and natriuresis during hyperosmotic NaCl infusion, and ETA receptor antagonist treatment producing marked effects on urine flow and Na+ excretion in ETB receptor-deficient rats. The apparent discrepancy in findings in male rats between the current study with intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion and the previous study with intramedullary infusion of ET-1 (23) may lie with the source of endothelin, i.e., endogenous vs. exogenous. It is likely that slightly different populations of endothelin receptors are being activated by the different experimental maneuvers used, uncovering a potential for ETA receptors in mediating natriuresis and diuresis in the current study, whereas this effect appeared to be counteracted by a reduction of renal medullary blood flow in the previous study with exogenous ET-1 infusion (23). Further experiments would be needed to discern whether changes in intrarenal hemodynamics may have contributed to the effects observed in our study.

Notably, ETA receptor antagonist treatment attenuated the natriuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion in ETB-deficient rats, whereas Na+ excretion was essentially unaffected by systemic ETA receptor or ETB receptor blockade in WT littermates and Sprague-Dawley rats. These observations suggest that factors other than endothelin are responsible for the bulk of the increase in Na+ excretion observed during hyperosmotic NaCl infusion. Indeed, if a large amount of paracellular Na+ flux occurred, this might obscure more modest effects of endothelin on Na+ excretion. We therefore examined whether hyperosmotic mannitol infusion elicited a natriuretic response and tested whether ETA and ETB receptor antagonism might affect this. We did not, however, observe natriuresis in response to hyperosmotic mannitol infusion. These results suggest that intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic solutions stimulates diuresis more effectively than natriuresis. Furthermore, these data suggest that the increase in Na+ excretion observed during intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl may arise via a process such as paracellular backleak of Na+ from the interstitium, rather than hyperosmolality-induced stimulation of natriuresis per se. Together with the lack of significant effect of endothelin receptor blockade on the increased Na+ excretion associated with hyperosmotic NaCl infusion, these data would suggest that the natriuresis observed in response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion is mediated by something other than pronatriuretic actions of hyperosmolality-induced ET-1 release.

Curiously, the natriuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion was significantly blunted by ETA receptor blockade only in ETB receptor-deficient sl/sl rats, with urinary Na+ excretion rate of ABT-627-treated rats being less than half that of vehicle-treated rats (Fig. 6C). It is not clear whether the seemingly unique role for the ETA receptor in mediating the natriuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion in sl/sl rats represents ETA receptor-mediated compensation for the chronic loss of functional ETB receptors in sl/sl rats, or might be related to the previously identified existence of an ET-3 binding site unique to the inner medulla of sl/sl rats (29). This atypical ET-3 binding site was shown in competition binding assays to bind the ETA receptor antagonist A-127722, a racemic mixture of which ABT-627 is the (+)-enantiomer, with high affinity (29). However, this binding site does not appear to be present in either Sprague-Dawley or heterozygous sl/+ rats (29). Nothing is currently known regarding the identity or function of this novel ET-3 binding site.

The mechanism by which ETA receptors promote diuresis and natriuresis and the cell types involved is not clear. It has been shown that ETA receptors stimulate NOS1 protein expression in inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD)-3 cells (28), and the ETA receptor-dependent diuretic and natriuretic response to intramedullary ET-1 infusion in female rats can be blocked with a NOS1 inhibitor (23). In addition to what is thought to be a small population of ETA receptors on IMCD cells (34), ETA receptors are also present on renal medullary interstitial cells, which release prostaglandin E2 in response to ET-1 (35), potentially enhancing Na+ and water excretion. The relative roles of NO, prostaglandins, or other mediators and the specific cell types involved in the ETA receptor-mediated diuretic response await future investigation.

Our findings that blockade or absence of both ETA and ETB receptor subtypes was necessary to markedly attenuate the diuretic response to hyperosmotic NaCl infusion suggest that one endothelin receptor subtype is able to compensate for impairment of the other under acute conditions. In a way, these data echo the phenotypes of collecting duct-specific endothelin receptor knockout mice. Selective deletion of ETA receptors from the collecting duct has little effect on blood pressure or Na+ excretion (14), whereas ETB receptor deletion produces salt-sensitive hypertension, although the increase in blood pressure is not as great as with collecting duct-specific knockout of ET-1 (12). Deletion of both ETA and ETB receptors, however, provides a hypertensive phenotype similar to collecting duct-specific knockout of ET-1 itself (3, 13). Together, these studies support a cooperative role for ETA and ETB receptors in controlling blood pressure and salt and water homeostasis.

It was surprising that ETA and ETB receptor blockade did not significantly attenuate the natriuretic response to intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl in Sprague-Dawley and WT rats given the large body of evidence implicating endothelin in the control of Na+ excretion. This suggests that the majority of the natriuretic response to intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion is due to factors other than the endothelin system, such as paracellular backleak. Indeed, factors other than the endothelin system may be called into play to help excrete the abrupt increase in intrarenal Na+ provided by intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl, although at this point we have not yet investigated other mechanisms. Finally, it should be borne in mind that acute intramedullary infusion of hyperosmotic NaCl is not the same as long-term exposure to a high-salt intake. Accordingly, the results of the current study do not negate previous studies by our group (26) and others (1, 10, 12, 13) demonstrating the importance of the endothelin system in responding to long-term changes in dietary salt intake.

In summary, our findings show that endothelin plays a critical role in mediating the diuretic response to intramedullary hyperosmotic NaCl infusion, further supporting the importance of the intrarenal endothelin system in salt and water handling by the kidney. In addition, our studies suggest that both ETA and ETB receptors contribute to this response and that abrogation of ETB receptor function unmasks a prodiuretic and natriuretic role for ETA receptors. These findings, together with recent findings of ETA receptor-mediated diuresis and natriuresis in female rats (23), show that the pronatriuretic and diuretic actions of endothelin are mediated by more than just the ETB receptor.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Post-Doctoral Fellowship and Beginning Grant-In-Aid from the American Heart Association (E. I. Boesen) and National Institutes of Health Grants HL-64776 and HL-74167 (D. M. Pollock).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. D. Kohan for invaluable scientific advice on this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abassi ZA, Ellahham S, Winaver J, Hoffman A. The intrarenal endothelin system and hypertension. News Physiol Sci 16: 152– 156, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abassi ZA, Tate JE, Golomb E, Keiser HR. Role of neutral endopeptidase in the metabolism of endothelin. Hypertension 20: 89– 95, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn D, Ge Y, Stricklett PK, Gill P, Taylor D, Hughes AK, Yanagisawa M, Miller L, Nelson RD, Kohan DE. Collecting duct-specific knockout of endothelin-1 causes hypertension and sodium retention. J Clin Invest 114: 504– 511, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballew JR, Watts SW, Fink GD. Effects of salt intake and angiotensin II on vascular reactivity to endothelin-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296: 345– 350, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boesen EI, Pollock DM. Acute increases of renal medullary osmolality stimulate endothelin release from the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F185– F191, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bugaj V, Pochynyuk O, Mironova E, Vandewalle A, Medina JL, Stockand JD. Regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel by endothelin-1 in rat collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1063– F1070, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowley AW., Jr Role of the renal medulla in volume and arterial pressure regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1– R15, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Jesus Ferreira MC, Bailly C. Luminal and basolateral endothelin inhibit chloride reabsorption in the mouse thick ascending limb via a Ca2+-independent pathway. J Physiol 505: 749– 758, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuroda T, Fujikawa T, Ozaki S, Ishikawa K, Yano M, Nishikibe M. Clearance of circulating endothelin-1 by ETB receptors in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 199: 1461– 1465, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gariepy CE, Ohuchi T, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Yanagisawa M. Salt-sensitive hypertension in endothelin-B receptor-deficient rats. J Clin Invest 105: 925– 933, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garvin J, Sanders K. Endothelin inhibits fluid and bicarbonate transport in part by reducing Na+/K+ ATPase activity in the rat proximal straight tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 976– 982, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ge Y, Bagnall A, Stricklett PK, Strait K, Webb DJ, Kotelevtsev Y, Kohan DE. Collecting duct-specific knockout of the endothelin B receptor causes hypertension and sodium retention. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F1274– F1280, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge Y, Bagnall A, Stricklett PK, Webb D, Kotelevtsev Y, Kohan DE. Combined knockout of collecting duct endothelin A and B receptors causes hypertension and sodium retention. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1635– F1640, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge Y, Stricklett PK, Hughes AK, Yanagisawa M, Kohan DE. Collecting duct-specific knockout of the endothelin A receptor alters renal vasopressin responsiveness, but not sodium excretion or blood pressure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F692– F698, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurbanov K, Rubinstein I, Hoffman A, Abassi Z, Better OS, Winaver J. Differential regulation of renal regional blood flow by endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 271: F1166– F1172, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrera M, Garvin JL. A high-salt diet stimulates thick ascending limb eNOS expression by raising medullary osmolality and increasing release of endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F58– F64, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson RW, Treiber FA, Harshfield GA, Waller JL, Pollock JS, Pollock DM. Urinary excretion of vasoactive factors are correlated to sodium excretion. Am J Hypertens 14: 1003– 1006, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Just A, Olson AJ, Arendshorst WJ. Dual constrictor and dilator actions of ET(B) receptors in the rat renal microcirculation: interactions with ET(A) receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F660– F668, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohan DE. The renal medullary endothelin system in control of sodium and water excretion and systemic blood pressure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 15: 34– 40, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohan DE, Padilla E. Osmolar regulation of endothelin-1 production by rat inner medullary collecting duct. J Clin Invest 91: 1235– 1240, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohan DE, Padilla E, Hughes AK. Endothelin B receptor mediates ET-1 effects on cAMP and PGE2 accumulation in rat IMCD. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 265: F670– F676, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Smith LA. Differential effects of endothelin on activation of renal mechanosensory nerves: stimulatory in high-sodium diet and inhibitory in low-sodium diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R1545– R1556, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakano D, Pollock DM. Contribution of endothelin A receptors in endothelin 1-ependent natriuresis in female rats. Hypertension 53: 324– 330, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oishi R, Nonoguchi H, Tomita K, Marumo F. Endothelin-1 inhibits AVP-stimulated osmotic water permeability in rat inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 261: F951– F956, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plato CF, Pollock DM, Garvin JL. Endothelin inhibits thick ascending limb chloride flux via ETB receptor-mediated NO release. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F326– F333, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Evidence for endothelin involvement in the response to high salt. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F144– F150, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strait KA, Stricklett PK, Kohan JL, Miller MB, Kohan DE. Calcium regulation of endothelin-1 synthesis in rat inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F601– F606, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan JC, Goodchild TT, Cai Z, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Endothelin(A) [ET(A)] and ET(B) receptor-mediated regulation of nitric oxide synthase 1 (NOS1) and NOS3 isoforms in the renal inner medulla. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 191: 329– 336, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor TA, Gariepy CE, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Unique endothelin receptor binding in kidneys of ETB receptor-deficient rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 284: R674– R681, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomita K, Nonoguchi H, Marumo F. Effects of endothelin on peptide-dependent cyclic adenosine monophosphate accumulation along the nephron segments of the rat. J Clin Invest 85: 2014– 2018, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomita K, Nonoguchi H, Terada Y, Marumo F. Effects of ET-1 on water and chloride transport in cortical collecting ducts of the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 264: F690– F696, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vassileva I, Mountain C, Pollock DM. Functional role of ETB receptors in the renal medulla. Hypertension 41: 1359– 1363, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Geldern TW, Tasker AS, Sorensen BK, Winn M, Szczepankiewicz BG, Dixon DB, Chiou WJ, Wang L, Wessale JL, Adler A, Marsh KC, Nguyen B, Opgenorth TJ. Pyrrolidine-3-carboxylic acids as endothelin antagonists. 4. Side chain conformational restriction leads to ET(B) selectivity. J Med Chem 42: 3668– 3678, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wendel M, Knels L, Kummer W, Koch T. Distribution of endothelin receptor subtypes ETA and ETB in the rat kidney. J Histochem Cytochem 54: 1193– 1203, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkes BM, Ruston AS, Mento P, Girardi E, Hart D, Vander Molen M, Barnett R, Nord EP. Characterization of endothelin 1 receptor and signal transduction mechanisms in rat medullary interstitial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F579– F589, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang T, Terada Y, Nonoguchi H, Ujiie K, Tomita K, Marumo F. Effect of hyperosmolality on production and mRNA expression of ET-1 in inner medullary collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 264: F684– F689, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeidel ML, Brady HR, Kone BC, Gullans SR, Brenner BM. Endothelin, a peptide inhibitor of Na+-K+-ATPase in intact renal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 257: C1101– C1107, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]