Abstract

Sexual behavior is associated with body image, but the directionality of this association is unclear. This study used longitudinal data from a sample of previously abstinent college students (N = 100, 45% female, 49% European American, 26% Latino American, 25% African American) to test whether satisfaction with appearance changed after first intercourse. Male students were more satisfied with their appearance after first intercourse, whereas female students became slightly less satisfied with their appearance. These findings demonstrate that first intercourse can lead to changes in well-being, even if the transition takes places in late adolescence. In addition, they suggest that gendered cultural expectations regarding sexual behavior are associated with differing psychological outcomes for male and female adolescents.

Researchers have asserted that sexual behavior and well-being are associated and should be studied in tandem (Coleman, 2002; O’Sullivan, McCrudden, & Tolman, 2006). However, little work has examined how becoming sexually active is associated with well-being in adolescence, particularly for individuals who experience this transition after the age of 15. Body image is one aspect of well-being that may change after engaging in first intercourse. Appreciation of one’s body is a part of healthy sexual development in adolescence (Brooks-Gunn & Paikoff, 1993; Hafner, 1998). Positive feelings about appearance are associated with having ever engaged in sexual behaviors and having sex more often in both adolescents and young adults (Faith & Schare, 1993; Gillen, Lefkowitz, & Shearer, 2006; Lammers, Ireland, Resnick, & Blum, 2000; Schooler, Ward, Merriweather & Carruthers, 2005; Trapnell, Meston, & Gorzalka, 1997; Wiederman & Hurst, 1998). Most studies of this association have used cross-sectional data, yet interpreted their findings as demonstrating that individuals who are more satisfied with their appearance are more likely to be comfortable with and engage in sexual behavior. However, it is also possible that individuals’ feelings about their appearance change after engaging in sexual behavior. This study uses longitudinal data to test whether satisfaction with appearance changes after an individual has engaged in sexual intercourse for the first time, and how such changes may differ by gender.

Transition to First Sexual Intercourse

Both popular media (TV shows like Gilmore Girls and movies like American Pie) and research (Carpenter, 2001; Tsui & Nicoladis, 2004) have described an individual’s first experience of sexual intercourse as an important and memorable transition which involves movement from one distinct state to another. Although adolescents engage in other types of sexual behavior, intercourse is often viewed as subjectively different than non-coital behaviors. Adolescents see intercourse as more intimate than oral sex, and are more likely to see intercourse as “sex” or a loss of virginity compared to behaviors like kissing, genital touching and oral sex (Bersamin, Fisher, Walker, Hill & Grube, 2007; Chambers, 2007; Sanders & Reinisch, 1999). Intercourse is also associated with more positive and negative emotional states, such as pleasure, positive affect, regret and negative affect compared to oral sex, and thus may have a stronger link to well-being than non-coital behaviors (Eshbaugh & Gute, 2008; Halpern-Felsher, Cornell, Kropp & Tschann, 2005; Lefkowitz, Vasilenko & Maggs, 2010). Despite the focus on intercourse as an important transition, many psychological aspects of this event have been relatively unexplored. Although researchers have stated the importance of a normative perspective on adolescent sexual development (Brooks-Gunn & Paikoff, 1993; Welsh, Rotosky & Kawaguchi, 2000), many studies have viewed adolescent sexuality as inherently risky and problematic, and subsequently have focused on factors that predict whether or not adolescents engage in intercourse rather than the psychological consequences of the transition.

Existing research on psychological outcomes of first intercourse has been of three main types. First, studies have compared groups of people who transitioned to first intercourse at different ages, and have found that early or late timing of intercourse is associated with negative psychological outcomes (Bingham & Crockett, 1996; Tubman, Windle & Windle, 1996). Other research has focused on retrospective reports of first intercourse. Although both male and female adolescents frequently report positive consequences of their first intercourse, research has focused on the greater negative consequences for girls, who generally experience more negative and fewer positive feelings about first intercourse, and report more guilt and less pleasure than boys (Darling, Davidson & Passarello 1992; Smiler, Ward, Caruthers, & Merriweather, 2005; Sprecher, Barbee, & Schwartz, 1995). These gender differences may be a result of sexual double standards that suggest that sex outside of marriage is viewed more negatively for women (Crawford & Popp, 2003). Finally, more recent research has used longitudinal data to examine changes in well-being after first intercourse, and has found similar gender differences to those observed in accounts of first intercourse. Early initiation of intercourse is associated with more depressive symptoms and lower self-esteem for girls, but not boys (Hallfors, Waller, Bauer, Ford, & Halpern, 2005; Meier, 2007), although this effect does not extend into young adulthood (Spriggs & Halpern, 2008). Thus, some negative psychological effects of adolescent sexual behavior may be more pronounced in the early or middle adolescent period than in later adolescence.

Although sex in late adolescence may not be problematic, it is not known whether engaging in first intercourse during this period is associated with positive psychological outcomes. It is possible that some individuals, particularly boys or men, may feel more positively about themselves after engaging in first intercourse. Engaging in sexual activity with a partner for the first time may boost self-esteem, as an individual may feel a partner has found them desirable enough for sexual activity (Wiederman, 2005). Men may be more likely to experience such positive feelings, due to gendered cultural messages about sexual behavior. Sexual competence is seen as a critical component of masculinity, and sexual behavior can be a way for male adolescents to assert their manhood (Marsiglio, 1998). In addition, girls or women may be more choosy about sexual partners or engaging in sexual behavior, due to the influence of sexual double standards (Wiederman, 2005). Thus, men may feel more positively about their appearance after engaging in sexual behavior with a new female partner, as they may feel they are desirable to a woman who is seen as more particular in her selection of partners (Wiederman, 2005).

Body Image and Sexual Behavior

Body image is an important component of well-being that may be associated with sexual behavior. Adolescents who are more satisfied with their appearance have fewer depressive symptoms and higher self-esteem than adolescents who are less satisfied (Siegel, 2002; Stice & Bearman, 2001). Body image is an aspect of well-being that may be particularly influenced by the transition to intercourse and other sexual behaviors, as engaging in such intimate behaviors can be a situation in which another person can see and evaluate an individual’s body. Research has shown such associations, as satisfaction with appearance is associated with a variety of sexual behaviors, such as receiving oral sex (Weiderman & Hurst, 1998), engaging in intercourse (Faith & Schare, 1993; Gillen et al., 2006; Lammers et al.; 2000) and having more sexual experience across a range of behaviors (Faith & Schare, 1993; Schooler et al., 2005; Trapnell et al., 1997).

One explanation for associations between satisfaction with appearance and sexual behavior is that individuals who feel dissatisfied with their body are more likely to be self-conscious during sexual activity, which can diminish their interest in sex (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Masters and Johnson, 1970). Spectatoring, or engaging in a constant negative focus on the appearance or sexual functioning of one’s body may hinder sexual enjoyment by keeping individuals from focusing on their own pleasure (Masters & Johnson, 1970). Spectatoring may be particularly problematic for women; physical attractiveness is seen as especially important for women, which may lead them to be more concerned about their appearance and how other people view them (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Women may internalize an objectifying male gaze, and subsequently view themselves as objects to be evaluated by men. This internalization, or self-objectification, can lead to dissatisfaction with physical appearance and habitual body monitoring (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Studies of body image and sexual behavior using this framework suggest that individuals who feel more dissatisfied with their appearance may feel less interested in or satisfied with sex, and may refrain from sexual behavior (Faith & Schare, 1993; Wiederman & Hurst, 1998). However, although research has used the concept of spectatoring to explain how body image may predict engaging sexual behavior, only one study of adolescents has used longitudinal data to show that more positive feelings about appearance predicts engaging in intercourse (Lammers et al., 2000). It is possible that engaging in sex also affects feelings about appearance. Engaging in sexual behavior could lead individuals to feel more positive about their appearance, as they may feel a partner had found them desirable enough for sexual activity (Wiederman, 2005). However, objectification theory would suggest that such associations may exist only for men, who are less likely to engage in body monitoring when engaging in sexual intercourse with a partner (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997).

Differences by Gender

Most studies of body image have looked primarily at girls or women, likely due to the perceived greater salience of body image concerns for women. Women are more likely than men to be looked at in a sexually objectifying way in both their everyday lives and in media representations (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). The ideals of attractiveness for women presented in the media are far different from women’s actual bodies (Silverstein, Perdue, Peterson, & Kelly, 1986; Wiseman, Gray, Moismann, & Ahrens, 1990). Female college students report greater dissatisfaction with their body or appearance than male students (Gillen & Lefkowitz, 2006; Heatherton, Nichols, Mahamedi, & Keel, 1995). However, many male students report dissatisfaction with their appearance (Gillen & Lefkowitz, 2006; Olivardia, Pope, Borowiecki, & Cohane, 2004). Men and women also differ in what they perceive as a physical ideal; women typically see a figure that is thinner than their own as ideal, whereas men choose ideal figures both larger and smaller than themselves (Cohn & Adler, 1992). This difference could reflect the importance of muscularity in men’s body image concerns (McCreary & Susse, 2000).

Although gender differences in body image have been documented, it is less clear if body image is differentially associated with sexual behavior in men and women. Most studies have examined only women (Schooler et al., 2005; Weiderman & Hurst, 1998) or examined men and women in separate models (Faith & Schare, 1993; Lammers et al, 2000; Trapnell et al., 1997), making it difficult to test gender differences. Given that gender differences have been observed in psychological outcomes of first intercourse, it is particularly important to examine whether first intercourse may be differentially associated with satisfaction with appearance in male and female students. Male students may feel more positive about their appearance after first intercourse, due to their more positive feelings about their first intercourse experience (Darling et al., 1992; Smiler et al., 2005; Sprecher et al., 1995) as well as cultural values that equate male sexual behavior with masculinity and self-worth (Marsiglio, 1998; Wiederman, 2005). In addition, women’s’ greater likelihood of body monitoring may lead them to feel more self-conscious and critical of their appearance, and thus they may feel less satisfied with their appearance after first intercourse.

This study uses longitudinal data from male and female college students to assess whether individuals’ satisfaction with appearance changes after engaging in first intercourse. Because research has shown racial and ethnic differences in both age of first intercourse (Upchurch, Levy-Storms, Sucoff, & Aneschel, 1998) and body image (Akan & Grilo, 1995; Altabe, 1998; Lopez, Blix, & Gray, 1995; Wildes, Emery, & Simons, 2001), we will also include race/ethnicity as a covariate in the model. Our primary research question will examine gender differences in changes in satisfaction with appearance after first intercourse. Based on theory on sexual double standards and objectification, we predict that such changes will differ for male and female students. Women may be more likely to feel self-conscious during sexual activity (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), and thus could become more critical of their appearance after sexual activity with a partner. Subsequently, we predict that women will experience a decrease in satisfaction with appearance after engaging in first intercourse. Men, on the other hand, may feel more positive about their appearance after becoming sexually active, as they have engaged in behavior that is seen as a component of masculinity (Marsiglio, 1998) and may feel they have been found desirable by female partners whom are perceived to be more selective in who they choose to have sex with (Wiederman, 2005). Thus, we predict that male students will experience an increase in satisfaction with their appearance after engaging in first sexual intercourse.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a longitudinal study of 434 college students recruited during their first year at a large, Northeastern university. Using a list of all traditional age (17-19) first year students from the Registrar we contacted 845 students, consisting of all African American and Latino American first year students and a random sample of 9% of European American first-year students. The response rate was 52%. Of these 434 participants, 253 engaged in intercourse prior to the start of the study, 100 engaged in first intercourse during the period of the study, 59 were abstinent at the end of the study and 22 dropped out prior to the end of the study and before reporting ever engaging in sexual intercourse. To examine the impact of first sexual intercourse on satisfaction with appearance, we include only the participants (N=100) who at entry to the study responded “no” to the question, “Have you ever engaged in penetrative sex (sex in which the penis penetrates the vagina or anus)? ”, but answered “yes” to the question at one of three later measurement occasions.

The 100 participants included in this study were 45% female, 49% European American, 26% Latino American, 25% African American and were, on average, 18.4 years old at Time 1 (SD=0.3). They were, for the most part, from relatively educated families, with 65% of participants’ fathers and 55% of mothers having completed an associate’s degree or higher, and 16% of fathers and 23% of mothers having completed a high school degree or less. The majority identified as heterosexual (97%), and 3% identified as bisexual. To examine how this sample of previously abstinent students differed from those who had engaged in penetrative sex prior to the start of the study, we ran a series of 3 ANOVA and 3 chi-square tests on demographic and other study variables at Time 1. The participants included in this sample were not significantly different from those in the larger study with respect to gender, race/ethnicity, parents’ education, or satisfaction with their appearance.

Procedures

Participants received a letter asking them to participate in a study about their attitudes and experiences in relationships with other people. Project staff subsequently contacted them by phone or email to schedule questionnaire completion. Participants completed a paper and pencil questionnaire in a university classroom with up to 25 other students at four measurement occasions (Time 1: fall first year, Time 2: spring first year, Time 3: fall second year, Time 4: fall fourth year). They completed informed consent forms and received the following compensation: $25 at Time 1, $30 at Time 2, and $35 at Time 3 and 4.

Measures

We used self reports of satisfaction with physical appearance, timing of first intercourse, and demographic characteristics. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and ranges for Time 1 satisfaction with appearance and age of first intercourse in years, by gender and race/ethnicity

| Satisfaction with Appearance | Age of First Intercourse | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | |

| Sample | 24.6 | 5.6 | 11-35 | 19.59 | 10.3 | 17.9-21.6 |

| Male | 25.9 | 5.5 | 11-35 | 19.58 | 10.0 | 17.9-21.25 |

| Female | 23.0 | 5.4 | 11-33 | 19.60 | 10.8 | 18.2-21.6 |

| European American | 24.5 | 5.5 | 11-35 | 19.68 | 9.9 | 18.4-21.23 |

| African American | 26.5 | 6.3 | 11-34 | 19.38 | 10.8 | 18.21-22.3 |

| Latino American | 22.8 | 4.6 | 11-29 | 19.60 | 10.6 | 17.92- 21.6 |

Note. Ages are presented in years for ease of interpretation; age in months was used in analyses.

Satisfaction with appearance

We measured participants’ overall level of satisfaction with appearance using the Appearance Evaluation subscale of the Multidimensional Body Self Relationship Questionnaire (MBSRQ, Cash, 2000). This measure assesses general satisfaction with appearance, rather than a particular aspect, like thinness. Past research demonstrates construct validity in that the measure is correlated in expected ways with factors like BMI, media internalization and eating disorder symptoms in college students (Cheng & Mallinckrodt, 2009; McGee, Hewitt, Sherry, Parkin & Flett, 2005). The Appearance Evaluation subscale had good reliability in all four timepoints of our study (α=.89-.90). Participants indicated their agreement with seven statements on a five point Likert-type scale (1 = definitely disagree to 5 = definitely agree), including “Most people would consider me good-looking”. Summary scores, calculated as the sum of item responses, ranged from 11 to 35, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with appearance.

Timing of First Sexual Intercourse

At each of the four occasions of measurement, participants were asked, “Have you ever engaged in penetrative sex (sex in which the penis penetrates the vagina or anus)?” All participants in the sample had answered “no” at Time 1, but answered “yes” at a later occasion of measurement. Because research with younger adolescents has found that a sizeable minority of participants rescind lifetime reports of intercourse (Upchurch, Lillard, Aneshensel & Li, 2002) we checked for inconsistent responses (reporting no penetrative sex after reporting “yes” at an earlier measurement occasion). Only one participant reported an inconsistent response on this item. Results did not differ when this participant was excluded from the analysis, and based on our decision rule to use earliest reports of first intercourse, we kept this participant in the analyses presented. During the semester that they first reported having had penetrative sex, participants answered an additional question about the month and year in which they first had penetrative sex. We used this information to calculate two timing variables. The first was a time index measuring time to/from first intercourse (TTFI). We used the date at which participants completed each survey to calculate the time in months between their engaging in first intercourse and when they took each survey. The month at which they engaged in first intercourse was set at 0; if an individual completed a survey five months before they reportedly engaged in first intercourse, that survey would be coded as -5 on this time variable. In short, time was “person-centered” on each individual’s date of first intercourse. To facilitate comparisons between before-first-sex and after-first-sex reports of body image we created an after first intercourse (AFI) variable to indicate whether the measurements were obtained before (coded as 0) or after (coded as 1) the individual’s first sexual intercourse.

Demographics

We used two types of demographic variables in our analysis. We assessed gender with an item asking if the participant was female (0) or male (1). We determined race/ethnicity based upon participants’ self-reported race. For participants who reported more than one race/ethnicity, we coded their race based on registrar data, which allowed for reporting of only one race. In this analysis, we used two binary variables for African American and Latino American race/ethnicity with European American as the reference group.

Results

To determine if individuals’ feelings about their appearance changed after engaging in first sexual intercourse and whether these changes differed by gender, we used a multiphase growth curve model. Because research on our full study sample has indicated that body image changes over the college years (Gillen, Patrick & Lefkowitz, 2010) it was necessary to test whether engaging in first intercourse led to change over and above that of normal developmental processes. Therefore, we constructed a multiphase growth model (Preacher, Wichman, MacCallum & Briggs, 2008; Ram & Grimm, 2007; Singer & Willett, 2003) that tested whether normative trends in satisfaction with appearance were affected by engaging in first sexual intercourse. In the final model, within-person changes (Level 1) were modeled as:

The repeated measures of satisfaction with appearance obtained from person i at occasion t were modeled as a function of four parameters. First, an individual-specific intercept, β0i, indicates each individual’s predicted level of satisfaction with appearance at first intercourse. β1i represents an individual-specific rate of change and models each individual’s normative trend in satisfaction with appearance over time (centered around that individual’s month of first intercourse), and β2i indicates the discrete shift in satisfaction with appearance in the period following first sexual intercourse. Unexplained residuals are represented by rti. Each participants’ intercept, β0i, normative developmental trends, β1i, and the amount of discrete shift, β2i, were modeled (at Level 2) as a function of interindividual characteristics including race/ethnicity and gender. Specifically,

The γ coefficients represent sample level effects, and u0i and u1i represent unexplained interindividual differences. Of particular interest are the γ20 and γ21 coefficients that indicate the extent of change in females’ (γ20) and males’ (γ21) satisfaction with appearance in the period following first sexual intercourse, independent of normative developmental changes.

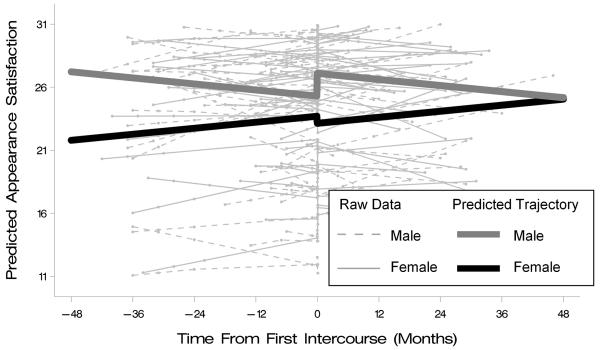

Results are presented in Table 2. Two significant differences between male and female students were found, and are plotted in Figure 1. First, the developmental trend in satisfaction with appearance differed for male and female students (γ11). On average, female students became more satisfied with their appearance over time, whereas male students’ satisfaction decreased. However, when examining patterns of appearance satisfaction after first intercourse, the opposite pattern was found (γ21). Transitioning to first intercourse was associated with a 1.80 point increase in satisfaction with appearance for male students. However, for female students, transitioning to first intercourse was associated with an average decrease of 0.57 points. These findings suggest that the association between transitioning to first intercourse and satisfaction with appearance was different for male and female students. On average female students in our sample became more satisfied with their appearance over time, but were somewhat less satisfied after first intercourse. Male students, on the other hand, became less satisfied with their appearance over time, but were more satisfied after first intercourse.

Table 2.

Multiphase growth curve model testing changes in satisfaction with appearance after first sexual intercourse, centered around month of first sexual intercourse

| Estimate | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | ||

| Intercept, γ00 | 23.71*** | 1.06 |

| Gender, γ01 | 1.59 | 0.18 |

| African American, γ02 | 1.67 | 1.27 |

| Latino American, γ03 | −1.30 | 1.27 |

| Time to/from First Intercourse (TTFI), γ10 | 0.04* | 0.02 |

| After First Intercourse (AFI), γ20 | −0.57 | 0.66 |

| TTFI × Gender, γ11 | −0.08* | 0.03 |

| AFI × Gender, γ21 | 2.37** | 0.89 |

| Random Effects | ||

| Variance Intercept, σ2u0 | 26.29*** | 4.20 |

| Covariance of Intercept and TTFI, σu0u1 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Variance of TTFI, σ2u1 | 0.01*** | 0.01 |

| Residual Variance, σ2r | 4.76*** | 0.52 |

Note. Time to/from First Intercourse (TTFI) refers to the time in months to/from an individuals’ reported month of first intercourse. After first intercourse (AFI) indicates whether a given measurement occasion is before or after an individual’s report of first intercourse. SE = standard error. Akaike Information Criteria=2009.1, -2 Log Likelihood=2001.1

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Figure 1.

Multiphase growth curve model showing trajectories of satisfaction with appearance over time and after first intercourse. Satisfaction with appearance scores have been centered around each individual’s month of first intercourse, where 0 indicates month of first intercourse, a negative time in months indicates a score from a measurement occasion before first intercourse, and a positive time in months indicates a score from a measurement occasion after first intercourse.

Discussion

This study used longitudinal data to explore whether previously abstinent college students’ satisfaction with appearance changes after engaging in first intercourse. We did not find an overall trend in changes in satisfaction with appearance, but instead found differing patterns for male and female students. On average, the male students in our sample became less satisfied with their appearance over time, and transitioning to first intercourse was associated with a more positive view of their appearance. A possible explanation for this finding is that male students who are abstinent at the start of college, and thus are late in timing of first intercourse, may feel less positive about their appearance over time because they have not engaged in behavior that that is a component of masculinity (Marsiglio, 1998). When these male students engaged in intercourse, they may have felt their masculinity was validated and subsequently felt more positive about their appearance. For male students, self-concept, which includes how they feel about their appearance, may be tied to their sexual behavior and feelings of sexual competence (Marsiglio, 1998; Wiederman, 2005). These findings suggest that associations between sexual behavior and male students’ body image observed in cross-sectional studies (Gillen et al., 2006; Trapnell et al., 1997) may be due in part to increases in satisfaction with appearance after first intercourse.

On average, female students who were abstinent at the start of college became more satisfied with their appearance over time, and transitioning to first intercourse had only a small negative impact on their body image. Adolescent girls are generally more dissatisfied with their adult body after puberty than boys, likely due to cultural expectations of thinness that are more typical of prepubescent girls than adult women (Stice, 2003). Thus, the overall increase in satisfaction with appearance for female students may reflect increased comfort with their appearance as they have become more accustomed to viewing themselves as mature adults. Becoming sexually active, however, may not have been associated with the increase in satisfaction with appearance experienced by male students, as women are more sexually objectified, and being physically attractive is seen as more important for women than men. Subsequently, female students may engage in more spectatoring or body monitoring, and thus may feel more self-conscious when engaging in sexual activity with a partner (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Masters & Johnson, 1970). In addition, girls and women generally report less positive feelings about first intercourse than boys and men (Darling et al., 1992; Smiler et al., 2005; Sprecher et al., 1995), possibly due to sexual double standards that encourage sexual behavior for men but restrict women’s sexual behavior (Crawford & Popp, 2003). Because women may feel less satisfied by and more guilty about their experience with first intercourse, they may feel less positive about themselves after engaging in first intercourse than their male peers, and subsequently may not experience an increase in satisfaction with appearance after first intercourse. Our finding for female students differs somewhat from cross-sectional research (Gillen et al., 2006; Trapnell et al., 1997) which suggests that both male and female students who are sexually active are more satisfied with their appearance than their abstinent peers. These results suggest that, for women, such cross-sectional associations may be due to other factors, such as more positive body image predicting engaging in sexual behavior (Lammers et al., 2000) or a third variable, such as greater physical attractiveness predicting both body image and likelihood of sexual behavior.

It is important to note that our finding represent average trajectories for men and women, and some women may feel more satisfied with their appearance after engaging in first intercourse. Thus, it is important to examine factors that may contribute to differences in individuals’ responses to first intercourse. Research on affective outcomes of first intercourse has found that many girls do experience positive feelings about this event (O’Sullivan & Hearn, 2008; Thompson, 1990), and sex in the context of a longer term relationship leads to a smaller gender difference in reaction to first intercourse (Sprecher et al., 1995). Future research should examine factors, such as the relationship with first sexual partner, that may be associated with more positive outcomes for girls and women after first intercourse.

These results contribute to the study of normative and healthy sexual development in several ways. First, this study examined associations between sexual behavior and satisfaction with appearance, which are important aspects of healthy sexual development (Brooks-Gunn & Paikoff, 1994). Our findings suggest that for women, engaging in sexual intercourse may linked to self-consciousness, and subsequently may not be associated with increased satisfaction with appearance. Thus, sexuality education programs could promote healthy sexual development by promoting body image in girls or young women. In addition, this study examined potential change in body image after first intercourse in individuals who were relatively late in their timing of first intercourse. Much of the research on psychological outcomes of first intercourse has reported negative correlates of engaging in first sex earlier than peers (e.g. Bingham & Crockett, 1996; Hallfors, Waller, Ford, Halpern, Brodish, & Iritani, 2004; Meier, 2007). However little is known about this transition in later adolescence or emerging adulthood. Our research suggests that the transition to first intercourse can have a positive impact on well-being for male adolescents and emerging adults, for whom sexual behavior may be seen as an important part of their masculine identity (Marsigllio, 1998). Future studies like this can contribute to a better understanding of sexual development by examining positive and negative psychological consequences of sex at different times in adolescence and emerging adulthood, in order to determine what factors lead to a more positive transition to first intercourse.

Although our results suggest that becoming sexually active can have a positive impact on some individuals’ well-being, it is important to consider how positive consequences of sex, such as the greater satisfaction with appearance, may relate to future sexual risk behaviors. The consequences of engaging in sexual behavior could influence future sexual risk behavior (Brady & Halpern-Felsher, 2007; Toates, 2009). Men with more positive body image engage in more risky sexual behaviors, and engaging in these behaviors may be a way of enhancing their masculinity and positive feelings about themselves (Gillen et al., 2006). Taken together with our finding that men feel more positively about their appearance after engaging in first intercourse, it is possible that men may engage in sexual behavior and possibly risky behaviors like sex with multiple partners, in order to experience more positive feelings about themselves. Thus, future research should address how experiencing positive consequences of sex, such as more positive body image or self-esteem, may influence future motivations for sex and sexual behavior.

There are several limitations to this study that future research could address. This sample consisted of college students who were abstinent at the start of the study. Thus it is not known whether these results would be replicated in samples of individuals who do not attend college, or with adolescents who engage in first intercourse at an earlier age. Longer-term longitudinal studies could examine how consequences of first intercourse may differ for individuals in different stages of adolescence and emerging adulthood. An additional limitation of this study is the amount of time between when individuals engaged in first intercourse and when they completed the surveys. We may not have been able to pick up on short term changes in satisfaction with appearance that occurred immediately after first intercourse. Future research could include surveys at monthly or weekly intervals in order to better detect shorter term changes in body image or other attitudes as a result of first intercourse. Finally, this study examined only penetrative sex, and future work should examine outcomes of other behaviors. Receiving oral sex appears to be particularly salient for body image in college women (Weiderman & Hurst, 1998), and research on younger adolescents suggests that transitions to earlier, non-coital behaviors may be more strongly associated with changes in sexual cognitions than intercourse (O’Sullivan & Brooks-Gunn, 2007). Including non-coital behaviors in future studies would give a fuller picture of adolescents’ sexual experience, including the experiences of lesbian adolescents.

Despite these limitations, this study makes several important contributions. First, it uses a longitudinal design to assess associations between body image and engaging in first sexual intercourse. These analyses suggest that, for male college students in particular, associations between body image and sexual behavior may be due at least partially to increased satisfaction with appearance after engaging in first intercourse. Second, this study examined the initiation of first intercourse in late adolescence, a topic that has received relatively little attention. In addition, this study adds to the knowledge of normative sexual development. Instead of using a risk perspective, we viewed sexual intercourse as a normative transition and explored a potentially positive outcome of transitioning to first intercourse. We found that first sexual intercourse can be associated with changes in psychological outcomes, even for individuals who experience this transition late relative to their peers. These findings underscore the importance of studying how sexual behavior is associated with psychological well-being.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sara A. Vasilenko, Pennsylvania State University S110 Henderson University Park, PA, 16802

Nilam Ram, Pennsylvania State University S110 Henderson University Park, PA, 16802 nilam.ram@psu.edu.

Eva S. Lefkowitz, Pennsylvania State University S110 Henderson University Park, PA, 16802 EXL20@psu.edu

References

- Akan GE, Grilo CM. Sociocultural influences on eating attitudes and behaviors, body image, and psychological functioning: A comparison of African-American, Asian-American, and Caucasian college women. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1995;18:181–187. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199509)18:2<181::aid-eat2260180211>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altabe MM. Ethnicity and body image: Quantitative and qualitative analysis. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;23:153–159. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199803)23:2<153::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersamin MM, Fisher DA, Walker S, Hill DL, Grube JW. Defining virginity and abstinence: adolescents’ interpretations of sexual behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham CR, Crockett LJ. Longitudinal adjustment patterns of boys and girls experiencing early, middle, and late sexual intercourse. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:647–658. [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, Halpern-Felsher BL. Adolescents’ reported consequences of having oral sex versus vaginal sex. Pediatrics. 2007;119:229–236. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Paikoff RL. “Sex is a gamble, kissing is a game”: Adolescent sexuality and health promotion. In: Millstein SG, Petersen AC, Nightingale EO, editors. Promoting the health of adolescents: New directions for the twenty-first century. Oxford University Press; New York: 1993. pp. 180–208. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LM. The ambiguity of “having sex”: The subjective experience of virginity loss in the United States. The Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38:127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF. Users’ manual for the multidimensional body-self relations questionnaire. Old Dominion University; Norfolk, VA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers WC. Oral sex: varied behaviors and perceptions in a college population. Journal of Sex Research. 2007;44:28–42. doi: 10.1080/00224490709336790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Mallinckrodt B. Parental bonds, anxious attachment, media internalization, and body image dissatisfaction: Exploring a mediation model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:365–375. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn LD, Adler NE. Female and male perceptions of ideal body shapes: Distorted views among Caucasian college students. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1992;16:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E. Promoting sexual health and responsible sexual behavior: An introduction. The Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford M, Popp D. Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. The Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:13–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling CA, Davidson JK, Passarello LC. The mystique of first intercourse among college youth: The role of partners, contraceptive practices, and psychological reactions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1992;21:97–117. doi: 10.1007/BF01536984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshbaugh E, Gute G. Hookups and sexual regret among college women. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;148:77–89. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.148.1.77-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Schare ML. The role of body image in sexually avoidant behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1993;22:345–356. doi: 10.1007/BF01542123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Roberts T. Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:173–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gillen MM, Lefkowitz EL, Shearer CL. Does body image play a role in risky sexual behavior and attitudes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Gillen MM, Lefkowitz ES. Gender role development and body image among male and female first year college students. Sex Roles. 2006;55:25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gillen MM, Patrick ME, Lefkowitz ES. A longitudinal study of body image in college students. 2010. Manuscript in preparation.

- Hafner DW. Facing facts: Sexual health for America’s adolescents. National Committee on Adolescent Sexual Health; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Bauer D, Ford CA, Halpern CT. Which comes first in adolescence--sex and drugs or depression? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Felsher BL, Cornell JL, Kropp RY, Tschann JM. Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: Perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;115:845–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Nichols P, Mahamedi F, Keel P. Body weight, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms among college students, 1982 to 1992. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;15:1623–1629. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers C, Ireland M, Resnick M, Blum R. Influences on adolescents’ decision to postpone onset of sexual intercourse: a survival analysis of virginity among youths aged 13 to 18 years. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26:42–48. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz ES, Vasilenko SA, Maggs JL. How positive affect, negative affect, and sexual partner vary by oral vs. vaginal sex. In: Lefkowitz ES, editor. Oral sex in adolescence: Timing, correlates, and subjective meaning; Symposium presented at the Society for Research on Adolescence; Philadelphia, PA. Mar, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez E, Blix GG, Gray A. Body image of Latinas compared to body image of non-Latina White women. Health Values. 1995;19:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W. Adolescent male sexuality and heterosexual masculinity: A conceptual model and review. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1998;3:285–303. doi: 10.1177/074355488833005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters W, Johnson V. Human sexual inadequacy. Little, Brown; Boston: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR, Sasse DK. An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:297–304. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee BJ, Hewitt PL, Sherry SB, Parkin M, Flett GL. Perfectionistic self-presentation, body image, and eating disorder symptoms. Body Image. 2005;2:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier AM. Adolescent first sex and subsequent mental health. The American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112:1811–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Olivardia R, Pope HG, Borowiecki JJ, Cohane GH. Biceps and body image: The relationship between muscularity and self esteem, depression, and eating disorder symptoms. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2004;5:112–120. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Brooks-Gunn J. The timing of changes in girls’ sexual cognitions and behaviors in early adolescence: a prospective, cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Hearn KD. Predicting first intercourse among urban early adolescent girls: The role of emotions. Cognition & Emotion. 2008;22:168–179. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, McCrudden MC, Tolman DL. To Your Sexual Health! Incorporating sexuality into the health perspective. In: Worell J, Goodheart CD, editors. Handbook of girls’ and women’s psychological health: Gender and well-being across the lifespan. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. pp. 192–199. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Wichman AL, MacCallum RC, Briggs NE. Latent growth curve modeling. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Grimm K. Using simple and complex growth models to articulate developmental change: Matching theory to method. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SA, Reinisch JM. Would you say you “Had sex” if … ? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:275–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler D, Ward LM, Merriwether A, Caruthers AS. Cycles of shame: Menstrual shame, body shame, and sexual decision-making. The Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42:324–334. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JM. Body image change and adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2002;17:27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein B, Perdue L, Peterson B, Kelly E. The role of the mass media in promoting a thin standard of bodily attractiveness for women. Sex Roles. 1986;14:519–532. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willet JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smiler AP, Ward LM, Caruthers A, Merriweather A. Pleasure, empowerment, and love: Factors associated with a positive first coitus. Sexuality Research Social Policy. 2005;2:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S, Barbee A, Schwartz P. “Was it good for you, too?”: Gender differences in first sexual intercourse experiences. The Journal of Sex Research. 1995;32:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs AL, Halpern CT. Sexual debut timing and depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:1085–1096. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9303-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. Puberty and body image. In: Hayward C, editor. Gender differences at puberty. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2003. pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Bearman SK. Body-image and eating disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: A growth curve analysis. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:597–607. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S. Putting a big thing into a little hole: Teenage girls’ accounts of sexual initiation. The Journal of Sex Research. 1990;27:341–361. [Google Scholar]

- Toates F. An integrative theoretical framework for understanding sexual motivation, arousal, and behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46:168–193. doi: 10.1080/00224490902747768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell PD, Meston CM, Gorzalka BB. Spectatoring and the relationship between body image and sexual experience: Self-focus or self-valence? The Journal of Sex Research. 1997;34:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui L, Nicoladis E. Losing it: Similarities and differences in first intercourse experiences of men and women. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2004;13:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Tubman JG, Windle M, Windle RC. The onset and cross-temporal patterning of sexual intercourse in middle adolescence: Prospective relations with behavioral and emotional problems. Child Development. 1996;67:327–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Levy-Storms L, Sucoff CA, Aneschel CS. Gender and ethnic differences in the timing of first sexual intercourse. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30:121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Lillard LE, Aneshensel CS, Li NF. Inconsistencies in reporting the occurrence and timing of first intercourse among adolescents. The Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39:197–197. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DP, Rotosky SS, Kawaguchi CM. A normative perspective of adolescent girls’ developing sexuality. In: Travis CB, White JW, editors. Sexuality, society and feminism. American Psychological Association; Washington: 2000. pp. 111–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman MW. The gendered nature of sexual scripts. The Family Journal. 2005;13:496–502. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman MW, Hurst SR. Body size, physical attractiveness, and body image among young adult women: Relationships to sexual experience and sexual esteem. The Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35:272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Wildes JE, Emery RE, Simons AD. The roles of ethnicity and culture in the development of eating disturbance and body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:521–551. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman CV, Gray JJ, Moismann JE, Ahrens AH. Cultural expectations of thinness in women: An update. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1990;11:85–89. [Google Scholar]