Scientific progress in biology typically relies on incremental advances that explain a small piece of an impossibly complex puzzle. But sometimes, understanding that one piece is enough. Scientists have long known that a rare cancer syndrome, called von Hippel–Lindau (VHL), had a hereditary component. First seen clustering in families over a century ago, the disease is characterized by vascular tumors, including retinal and central nervous system “hemangioblastomas” and clear-cell carcinomas of the kidney and adrenal glands. Just ten years ago, scientists identified the tumor suppressor gene, called VHL, that causes the disease and later discovered how loss of VHL leads to cancer.

It had appeared this pathway was uncommonly simple. VHL regulates HIF (hypoxia-inducible factor), a transcription factor that controls cellular responses to below-normal oxygen levels in the blood or tissue, a condition known as hypoxia. In the presence of oxygen, the VHL gene product pVHL forms a complex with other proteins and targets HIF for degradation. In response to hypoxia, HIF activity increases and induces the expression of a number of proteins that help cells adapt to low levels of oxygen. If VHL function is lost, it cannot target HIF, leading to a stable accumulation of HIF and a corresponding overproduction of the hypoxia-induced proteins. When aberrantly produced, these proteins contribute to tumor formation and growth through angiogenesis (the mass of blood vessels characteristic of hemangioblastomas) and unregulated cell growth. But subsequent studies suggested that VHL might have other targets, raising the possibility that HIF might not be the sole, or even primary, mediator of tumor formation in cells lacking pVHL. Now William Kaelin and colleagues report that inhibiting HIF is not only necessary to support pVHL's function as a tumor suppressor, but that it is also enough.

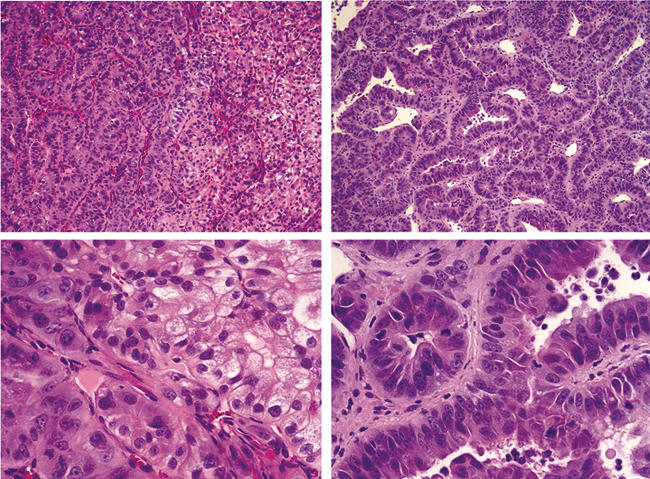

The researchers set out to determine whether the inhibition of HIF was specifically responsible for pVHL's reported tumor suppressive effects. When pVHL is reintroduced into human renal carcinoma cells lacking pVHL and overexpressing HIF2α, HIF2α levels go down, hypoxia-inducible gene expression goes down, and tumorigenesis is suppressed. Kaelin et al. found that introducing HIF2α variants lacking specific pVHL-binding sites into such cells was sufficient to negate pVHL's tumor suppressor activity, implying that inhibition of HIF is necessary for pVHL to suppress tumor growth. To see whether simply removing HIF2〈 would mimic the tumor suppressor activity of pVHL, the researchers introduced “short hairpin” RNAs (shRNAs) to “silence” HIF2α protein production. The shRNA-treated cells (which lacked functional VHL genes) showed decreased levels of HIF2α activity and were grossly impaired with respect to facilitating tumor formation in mice. These results suggest that, while pVHL may have multiple functions, inhibition of HIF can account for its ability to suppress tumor growth, at least in the context of renal carcinoma.

Tumor suppressor genes are defined by what happens in their absence—while their normal function is not always apparent, it is clear that their loss of function results in cancer susceptibility—and by the fact that they usually require loss of both versions, or alleles, for damage to occur. While patients with VHL inherit one mutated copy and later acquire a mutation in the second copy, patients with similar but nonhereditary vascular cancers have also lost both VHL alleles. Knowing HIF's role as the fulcrum between health and disease, scientists can now concentrate on just that one piece of the puzzle—HIF and its target genes—to develop customized preventive and therapeutic treatments not only for VHL patients but for those living with nonhereditary tumors, such as kidney cancers, that frequently result from pVHL inactivation.

Tumor suppression by HIF2α shRNA.