Abstract

Phantom sensations and sensory hypersensitivity are disordered perceptions that characterize a variety of intractable conditions involving the somatosensory, visual, and auditory modalities. We report physiological correlates of two perceptual abnormalities in the auditory domain: tinnitus, the phantom perception of sound, and hyperacusis, a decreased tolerance of sound based on loudness. Here, subjects with and without tinnitus, all with clinically normal hearing thresholds, underwent 1) behavioral testing to assess sound-level tolerance and 2) functional MRI to measure sound-evoked activation of central auditory centers. Despite receiving identical sound stimulation levels, subjects with diminished sound-level tolerance (i.e., hyperacusis) showed elevated activation in the auditory midbrain, thalamus, and primary auditory cortex compared with subjects with normal tolerance. Primary auditory cortex, but not subcortical centers, showed elevated activation specifically related to tinnitus. The results directly link hyperacusis and tinnitus to hyperactivity within the central auditory system. We hypothesize that the tinnitus-related elevations in cortical activation may reflect undue attention drawn to the auditory domain, an interpretation consistent with the lack of tinnitus-related effects subcortically where activation is less potently modulated by attentional state. The data strengthen, at a mechanistic level, analogies drawn previously between tinnitus/hyperacusis and other, nonauditory disordered perceptions thought to arise from neural hyperactivity such as chronic neuropathic pain and photophobia.

INTRODUCTION

Subjective tinnitus, the ongoing perception of sound in the absence of any physical stimulus, is a common clinical condition lacking effective treatments. Severe hyperacusis, in which sound intensities considered comfortable by most people are unbearably loud (Baguley 2003), can accompany tinnitus. Importantly, “hyperacusis” does not imply a better-than-normal threshold sensitivity to sound, nor is it the same as loudness recruitment, the abnormally rapid growth in perceived loudness with increasing sound intensity that occurs with hearing loss (Tyler et al. 2003). Even people with clinically normal auditory thresholds can have hyperacusis, as was the case for participants in this study.

Tinnitus and hyperacusis have been hypothesized to arise from “abnormal gain” within the auditory pathway. The presumptive neural gain results in abnormal perception of sound without a physical stimulus (tinnitus) or of sound loudness (hyperacusis) (Levine and Kiang 1995; Salvi et al. 2000). Neural abnormalities suggestive of abnormal gain have been reported in animals showing behavioral evidence of tinnitus and in humans with tinnitus (Arnold et al. 1996; Kaltenbach et al. 2004; Lockwood et al. 1998). The defining characteristic of hyperacusis, reduced tolerance of sound on the basis of loudness, has yet to be linked to any neural abnormality.

These experiments build on the following finding shown with functional MRI (fMRI): on average, tinnitus subjects show elevated responses to sound in the auditory midbrain compared with non-tinnitus controls (Lanting et al. 2008; Melcher et al. 2009). Melcher et al. closely matched tinnitus and non-tinnitus subjects on major covariates of tinnitus, threshold sensitivity, depression, anxiety, and age, thus excluding the possibility that these variables, rather than tinnitus, accounted for the increased sound-evoked activity in the tinnitus group (Melcher et al. 2009). The study did not, however, consider a remaining and potentially crucial variable: hyperacusis. Thus it remains unclear whether the previously documented elevations in sound-evoked activation reflect tinnitus, hyperacusis, or both.

The possibility of a relationship between hyperacusis and the elevated sound-evoked activity seen in the midbrain of tinnitus subjects is raised because of 1) psychophysical data in normal subjects showing increases in perceived loudness with increasing sound intensity, repetition rate, or bandwidth, and 2) fMRI data, also in normal subjects, showing increases in midbrain activation for similar parameter variations (Brittain 1939; Harms and Melcher 2002; Hawley et al. 2005; Pollack 1951; Sigalovsky and Melcher 2006; Zwicker et al. 1957). Importantly, the increases in loudness and activation cannot be entirely attributed to increases in sound energy: increasing the bandwidth of sound while holding total sound energy constant still increases perceived loudness and fMRI activation of the midbrain (Hawley et al. 2005; Zwicker et al. 1957). This tendency in normal subjects leads to the following hypothesis: subjects abnormally intolerant of sound on the basis of loudness would have elevated activation to sound in the midbrain and possibly other auditory centers. This study tested this hypothesis and more generally addressed whether tinnitus, abnormal sound-level tolerance (SLT), or both contribute to the elevated activation to sound reported previously in tinnitus subjects.

Portions of this work were presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology (2008) and the 2nd Meeting of the Tinnitus Research Initiative (2007).

METHODS

Subjects

Twenty-seven subjects underwent behavioral testing followed by functional imaging. Thirteen subjects had tinnitus [age = 43 ± 3 (SD) yr; 10 male; 10 right-handed and 1 ambidextrous]. The remaining 14 did not have tinnitus (age = 45 ± 3 yr; 8 male; 13 right handed and 1 ambidextrous). Each subject's SLT was quantified as described below. Subjects had no known neurological disorders. Mean characteristics for tinnitus and nontinnitus subjects with normal and abnormal SLT are given in Table 1. Characteristics of individual subjects are given in Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of each subject group

| Tinnitus, Abnormal SLT | Nontinnitus, Abnormal SLT | Tinnitus, Normal SLT | Nontinnitus, Normal SLT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 7 | 5 | 6 | 9 |

| Age | 41 ± 4 | 45 ± 5 | 45 ± 5 | 45 ± 4 |

| Sex (% female) | 43 | 60 | 0 | 33 |

| Depression score | 10 ± 3 | 4 ± 2 | 10 ± 4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| Anxiety score | 8 ± 3 | 6 ± 4 | 6 ± 1 | 0.8 ± 0.3 |

| TRQ score | 28 ± 6 | 30 ± 10 | ||

| LDL (dB SPL) | 92 ± 2 | 106 ± 4 | 111 ± 1 | 113 ± 1 |

| SLTQ score | 0.69 ± 0.09 | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 0.96 ± 0.02 | 0.94 ± 0.03 |

| Threshold for continuous noise (dB SPL) | 20 ± 3 | 23 ± 2 | 17 ± 3 | 16 ± 2 |

Values are means ± SE. SLT, sound-level tolerance; TRQ, Tinnitus Reaction Questionaire; LDL, loadness discomfort level; SLTQ, SLT questionnaire.

All but one of the tinnitus subjects (10) were recruited through the Tinnitus Clinic at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary (MEEI). The remaining tinnitus subject and all nontinnitus subjects were recruited from advertisements in local newspapers and personal contacts. All of the subjects recruited through the Tinnitus Clinic reported tinnitus, not sound-level intolerance, as their primary complaint. Any abnormality of SLT was mild and not always self-recognized.

This study was approved by the institutional committees on the participation of human subjects at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts General Hospital, and MEEI. All subjects gave their written informed consent.

Hearing threshold

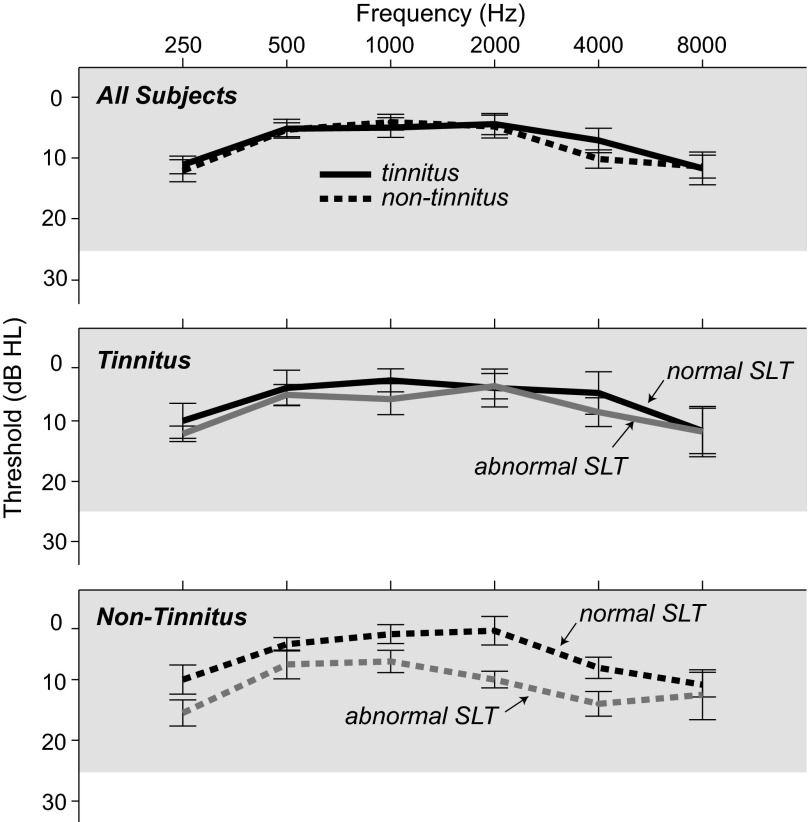

Subjects had normal pure tone thresholds (≤25 dB HL) at octave intervals from 250 through 8,000 Hz, except for two subjects (72 and 85), both with tinnitus, in whom the threshold at 8 kHz was 30–35 dB HL in one ear. Although elevated high-frequency thresholds are not the norm in subjects of these ages (45 and 52 yr), this finding is not uncommon clinically. Mean pure tone threshold for the tinnitus and non-tinnitus subjects differed by 3 dB or less at any given frequency (Fig. 1, top). Figure 1, middle and bottom, shows mean thresholds for tinnitus and non-tinnitus subjects, respectively, separating subjects into two SLT categories: normal and abnormal (categories defined below).

Fig. 1.

Mean pure tone thresholds for each subject group. Top: tinnitus and non-tinnitus subjects. Middle: tinnitus subjects divided according to sound-level tolerance (SLT; normal or abnormal) as shown in Fig. 3. Bottom: non-tinnitus subjects divided according to SLT. Bars indicate ±SE. Gray shading indicates clinically normal threshold range.

Measuring loudness discomfort level

The highest tolerable level of broadband noise, the stimulus used during imaging, was determined for each subject as follows (Cox et al. 1997). The noise was presented over headphones (TDH-39P) for ∼1 s at a time at progressively higher levels beginning with 35 dB SPL. The noise level was incremented in 5 dB steps until 115 dB SPL was reached or the subject indicated the stimulus was uncomfortably loud. For each sound level, subjects rated the perceived loudness on a numerical scale that ranged from 1 (very soft) to 7 (uncomfortably loud). Before testing, subjects were read a slightly modified form of the instructions given by Cox et al. (1997). The instructions were as follows:

“The purpose of this test is to find your judgment of the loudness of different sounds. You will hear sounds that increase in volume. You must make a judgment about how loud these sounds are. Pretend you are listening to the radio. How loud would it be? We will stop when you say the sound is uncomfortably loud (number 7). Please hold out as long as you can before indicating that the sound is uncomfortably loud.”

Each ear was tested four times, over which subjects converged on a highly repeatable assignment of number to level. The sound levels deemed “uncomfortable” during the last two of the four tests were averaged to obtain the loudness discomfort level (LDL) for the tested ear. LDL differed between ears by 6 dB or less in all but three subjects and by only 9 dB in those cases. Therefore LDL averaged between the two ears was used as the final LDL for a given subject. Note that this test of assigning a numerical rating to sounds of increasing level was used because it provided a systematic and reliable way to reach the well-defined endpoint of the range when the sound level is “uncomfortably loud” (i.e., 7). The test does not, however, provide an accurate measure of absolute loudness because the range of numbers available for assignment is restricted. Thus ratings below 7 are not considered further.

One subject with tinnitus (28) declined to do the full LDL test because of concerns about exposure to high-level sounds. He underwent an abbreviated procedure that tested each ear twice instead of four times, began the testing at 55, rather than 35, dB SPL, and did not provide loudness ratings other than an indication of 7 (uncomfortable). Of the two measurements made for each ear, the higher level deemed uncomfortably loud was taken to be the LDL.

Assessment of behavioral tinnitus characteristics

In tinnitus subjects, tinnitus pitch, tinnitus loudness, minimum masking level (MML), and residual inhibition were assessed. The pitch of the tinnitus was the pure tone frequency from 250 to 8,000 Hz deemed most similar in pitch to the tinnitus (determined with half-octave frequency resolution). Tinnitus loudness was determined by adjusting the level of monaural broadband noise to match the loudness of the tinnitus to within 5 dB. For subjects with unilateral tinnitus, the noise was presented to the tinnitus ear. For subjects with bilateral tinnitus, each ear was tested. MML was the lowest level of binaurally presented broadband noise needed to completely mask the tinnitus. Tinnitus loudness and MML were expressed relative to the detection threshold of the broadband noise [that is, in dB sensation level (dB SL)]. The test for residual inhibition established whether 1 min of binaurally presented broadband noise at 10 dB above MML resulted in complete tinnitus suppression for any length of time after the noise was turned off. In Table S3, the “residual inhibition” column indicates whether or not complete tinnitus suppression occurred.

Questionnnaires

All subjects completed a handedness questionnaire (Oldfield 1971) and inventories of depression and anxiety (Beck et al. 1961, 1988). For the latter, higher scores indicate greater symptom severity; the maximum score is 62 (depression) and 63 (anxiety).

All subjects also completed a questionnaire assessing SLT (SLTQ) (Tyler et al. 2003). This questionnaire asked subjects to rate their agreement with the following three statements by assigning a number from 0 (strongly disagree) to 100 (completely agree). 1) Many everyday sounds are unbearably loud to me. 2) Sounds that others believe are moderately loud are too loud to me. 3) I hear very soft sounds that others with normal hearing do not hear (taken from the Hyperacusis Intake questionnaire of Tyler et al. 2003). A score on the SLTQ was calculated as 1 minus the following: the sum of the three responses, divided by the maximum sum of 300. Because the third question on the SLTQ differs from the first two in that it probes the perceived loudness of near-threshold sounds, we examined whether it had an undue influence on SLTQ score and on our eventual categorization of subjects into normal and abnormal SLT groups. Two analyses indicated it did not: 1) the response to the third question was correlated with the sum of the responses to the first two questions (Spearman r = 0.4, P = 0.03); and 2) no subject's SLT category changed when question 3 was omitted from the calculation of the SLTQ score. (Note that in calculating the SLTQ score without question 3, the sum of the remaining two responses was divided by 200, not 300.)

Subjects with tinnitus completed two additional questionnaires: one asking about the characteristics of their tinnitus (e.g., quality of percept, location) and a second assessing the effects of tinnitus on quality of life [the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) of Wilson et al. 1991]. For the latter, higher scores indicate greater distress. The range of possible scores is 0 (no distress) to 104.

The questionnaire data for each subject are given in Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

Acoustic stimulation and visual task

During imaging, subjects were stimulated with 32-s segments of broadband continuous noise delivered binaurally at 50, 70, and 80 dB SPL. The periods of stimulation were separated by 36- or 38-s periods of no stimulation. Four alternations of stimulation/no stimulation comprised a single scanning run. Noise level was the same for all stimulation periods of a given run and was varied pseudorandomly across runs. The noise was low-pass filtered (10-kHz cut-off) and spectrally shaped to account for the frequency response of the insert earphones used for delivery of the sound stimulus (Sensimetrics, Malden, MA). The noise spectrum measured on an artificial ear was flat to within 5 dB.

In the scanner room, before imaging, detection threshold for the noise stimulus was measured separately for each ear to establish stimulus levels in dB SL. (The scanner coolant pump was turned off for these measurements and during the functional imaging described below.) Threshold ranged from 5 to 30 dB SPL [mean for tinnitus subjects: 19 ± 2 (SE) dB SPL; nontinnitus: 19 ± 2]. Thus the 50, 70, and 80 dB SPL stimulation levels corresponded to 20–45, 40–65, and 50–75 dB SL, respectively. Also, in the scanner room before imaging, subjects were presented with each stimulus level for the full 32-s duration to be used during imaging. Based on this exposure (longer than during the LDL test and in a different environment), eight subjects declined to be imaged with the 80 dB SPL stimulus.

Subjects were instructed to watch a black cross in their field of view that briefly turned red at random intervals throughout each run (throughout both stimulation and no stimulation periods). They were further instructed to press a button whenever the color changed. The average interval between color changes was ∼7 s, only short enough to prevent subjects from falling asleep.

Imaging

Subjects were imaged in a 3-T scanner using a 12-channel head coil (Siemens Trio with Matrix head coil). In each imaging session, the following occurred. 1) T1-weighted, high-resolution anatomical images of the whole head were acquired (128 slices, thickness = 1.33 mm, gap = 0.67 mm, in-plane resolution = 1 × 1 mm, TR = 2,530 ms, TI = 1,100 ms, TE = 3.39 ms). 2) The brain slices to be functionally imaged were selected based on the anatomical images. Ten parallel slices covered the brain stem, thalamus, and temporal lobe. The second posterior-most slice was positioned to intersect the inferior colliculi and cochlear nuclei. 3) Functional images were acquired using a blood oxygenation level–dependent (BOLD) sequence (gradient echo, TE = 30 ms, flip = 90°, slice thickness = 6 mm, gap = 2 mm, in-plane resolution = 3.125 × 3.125 mm). Images of the 10 selected slices were acquired, from posterior to anterior, in brief (<1 s) clusters with a TR of ∼8 s (Edmister et al. 1999; Hall et al. 1999). The onset of stimulus presentation was delayed by 0, 2, 4, or 6 s relative to the first cluster of each run, so that the effective temporal sampling interval within the overall data set would be ∼2 s. Typically, three runs were collected at each stimulus level, yielding 108 images per level. Functional image acquisition was synchronized to the subject's first pulse (measured using a pulse oximeter) following a minimum interimage interval of 7.5 s, yielding a TR of ∼8 s (Guimaraes et al. 1998).

Image processing

Image signal in the functional data were 1) corrected for slight movements of the head using SPM2, 2) corrected for drifts in amplitude over time, and 3) normalized such that the time-average signal had the same (arbitrary) value for all runs (Harms and Melcher 2002). The time series of images corresponding to functional runs at the same stimulus level were concatenated to form a single data set from which activation maps were derived by comparing image signal between sound on and off periods using an unpaired t-test (see Fig. 2A). A hemodynamic delay of 4 s was assumed in the assignment of images to the on and off periods. For subjects in whom two, rather than three, runs were obtained (1 or 2 stimulus levels in 3 subjects) or where four runs were obtained, the P value result of the t-test was adjusted to what it would have been if the number of runs had been three. This adjustment was to multiply the t-score by the square root of the following: the number of images in three runs divided by the actual number of images collected. Finally, for each stimulus level, the percent change in image signal was calculated on a voxel-by-voxel basis

where Son and Soff are the signals averaged over stimulus on and off periods, respectively.

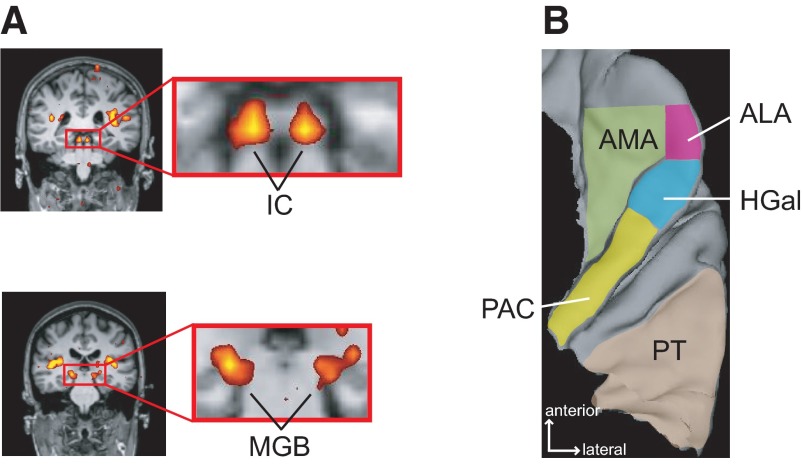

Fig. 2.

Regions of interest in functional MRI (fMRI) analysis. A: subcortical regions of interest (ROIs). Location of the inferior colliculus (IC) and medial geniculate body (MGB) is shown by the images from 1 subject (37). The IC and MGB are shown in enlargements of the rectangular area (red outline) in near-coronal images of the whole head. Sound-evoked activation (color) is localized to the inferior colliculi (top) and medial geniculate bodies (bottom). The significance of the activation is colorized on a red (P = 0.01) to yellow (P = 2 × 10−9) scale. The activation is superimposed on anatomical images obtained in the same imaging session (grayscale). B: cortical ROIs. The location of each analyzed region is indicated on a reconstructed superior temporal lobe. PAC, primary auditory cortex; HGal, anterolateral Heschl's gyrus; PT, planum temporale; ALA, anterolateral area; AMA, anteromedial area.

Quantification of activation

Activation was quantified within regions of interest (ROIs) defined relative to gross anatomical landmarks. These ROIs included three subcortical structures, the inferior colliculus (IC), medial geniculate body (MGB), and cochlear nucleus (CN), localized as described in Hawley et al. (2005) and Harms and Melcher (2002). They also included the following cortical ROIs (Fig. 2B):

primary auditory cortex (PAC), occupying the posterior medial two thirds of Heschl's gyrus (the more anterior 1, or 1st, when there are 2) and defined to coincide with primary auditory cortex (Rademacher et al. 2001; Sigalovsky et al. 2006),

anterolateral Heschl's gyrus (HGal), the remaining anterolateral third of first Heschl's gyrus, coinciding with primary-like areas on the gyrus,

anteromedial area (AMA), the region anterior and medial to PAC and HGal; AMA also extended rostrally with a lateral limit corresponding to the medial edge of HGal at its rostral limit.

anterolateral area (ALA), the region lateral to AMA and anterior to HGal,

planum temporale (PT), defined as the region lateral and posterior to Heschl's gyrus, but excluding any 2nd Heschl's gyrus (present on 1 side in 6 subjects).

Results of a previous cytoarchitectonic study of human superior temporal lobe guided the choice of cortical ROIs and their detailed definition. The study, by Fullerton and Pandya (2007), concluded that auditory cortex in humans has the same organizational plan as that of monkeys: a central core surrounded by medial and lateral belts. Furthermore, they showed the relationship between cytoarchitectonically defined core/belt areas and the gross anatomy of the human superior temporal lobe. These relationships were used to define AMA and PT to approximate the medial and lateral belt, respectively. PAC, HGal, and ALA correspond to the core.

Quantification of activation for each ROI was as follows. First, voxels showing a significant (P < 0.01) difference in image signal between stimulus on and off periods for at least one sound level were identified. Second, voxels with a percent signal change >4% for any sound level were excluded because the response was considered artifactual. Third, activation was quantified by averaging percent signal change across the remaining voxels. Note that the voxels included in this average were the same for all stimulus levels. Finally, for each structure (IC, MGB, etc.), a single activation value was obtained by averaging the activation of the left and right ROIs for that structure. This averaging was deemed appropriate because systematic differences in percent change between the left and right hemispheres were not seen for any structure or for any subject group. In instances where percent change could only be determined for the ROI on one side (because of poor signal-to-noise ratio on the other side), the activation from that one ROI was used instead of the average.

ROIs that failed to show activation at any sound level were handled in one of two ways depending on the most likely reason for the lack of activation, either ratio low percent signal change or poor signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), where SNR was defined as the mean signal over time divided by the SE. If at least two thirds of the voxels comprising an ROI had a high enough SNR at a particular level to detect signal changes of 0.5% or less, and yet no activation was detected, percent signal change for the ROI was assigned a value of zero at that level. All other ROIs failing to activate were excluded from analysis because they could not be reasonably assigned a percent signal change value of zero. (Because the SNR of most voxels in the ROI was low, percent changes in excess of 0.5% were possible, but not detectable.) The number of excluded ROIs was as follows: PAC 0/54 hemispheres, HGal 8/54 hemispheres, PT 4/54 hemispheres, AMA 5/54 hemispheres, ALA 10/54 hemispheres, IC 2/54 hemispheres, MGB 23/54 hemispheres, and CN 32/54 hemispheres. Because fewer than one half the CNs produced usable data and firm conclusions could not be drawn from the remaining data, the CN will not be considered further in this report.

RESULTS

Behavioral data: measurements of SLT

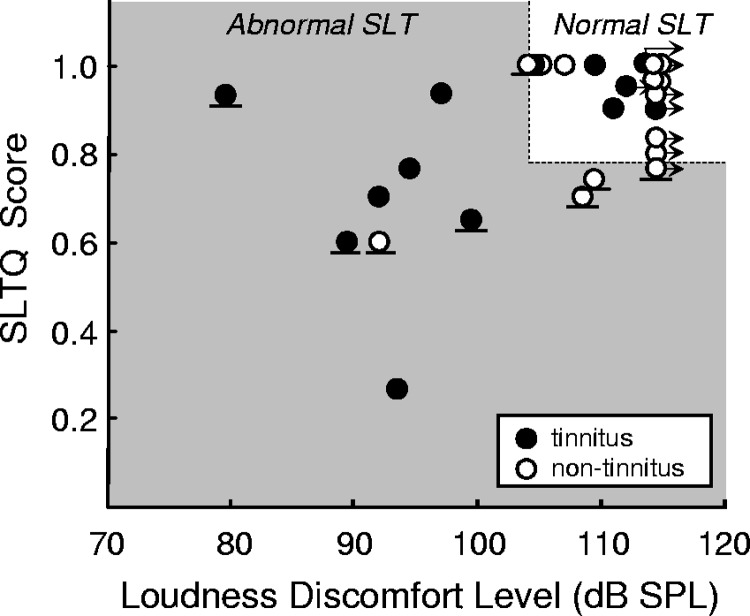

Subjects reported numerical loudness ratings that increased with increasing stimulus level: from 1 (very soft) to 7 (uncomfortably loud) or from 1 to 6 (loud, but okay) in nine subjects for whom even the highest intensity stimulus possible with our equipment was not uncomfortable. These data provided one of the two measures of SLT used in this study: LDL (the sound level assigned a 7) or a lower bound on LDL in subjects whose highest numerical rating of loudness was 6. The second measure was SLTQ score. The two measures generally confirmed each other in that subjects with high LDLs had SLTQ scores near 1, indicating normal SLT by both measures, whereas those with lower LDLs tended to have lower SLTQ scores, indicating an intolerance of sound levels usually considered comfortable (Fig. 3; r = 0.4, P = 0.05; Spearman correlation).

Fig. 3.

Classification of subjects by SLT. Subjects were classified as having abnormal (gray shaded area) or normal (white at top right) SLT based on loudness discomfort level (LDL) and a questionnaire assessing SLT (SLTQ) score. Each symbol corresponds to a subject. The division between normal and abnormal SLT regions was defined such that subjects unable to tolerate the 80 dB SPL stimulus during scanning (symbols with horizontal line below) would lie in the abnormal SLT region. Right arrows are placed next to the data for subjects who deemed no sound level “uncomfortable,” including the maximum possible level produced by our testing equipment. In 2 cases where the maximum level was not deemed “uncomfortable” for 1 ear and a lower level was deemed “uncomfortable” for the other ear, the average of the maximum possible level and the level deemed “uncomfortable” was defined as the LDL, and a right arrow was included.

Activation in the auditory midbrain and thalamus: dependencies on SLT and not tinnitus

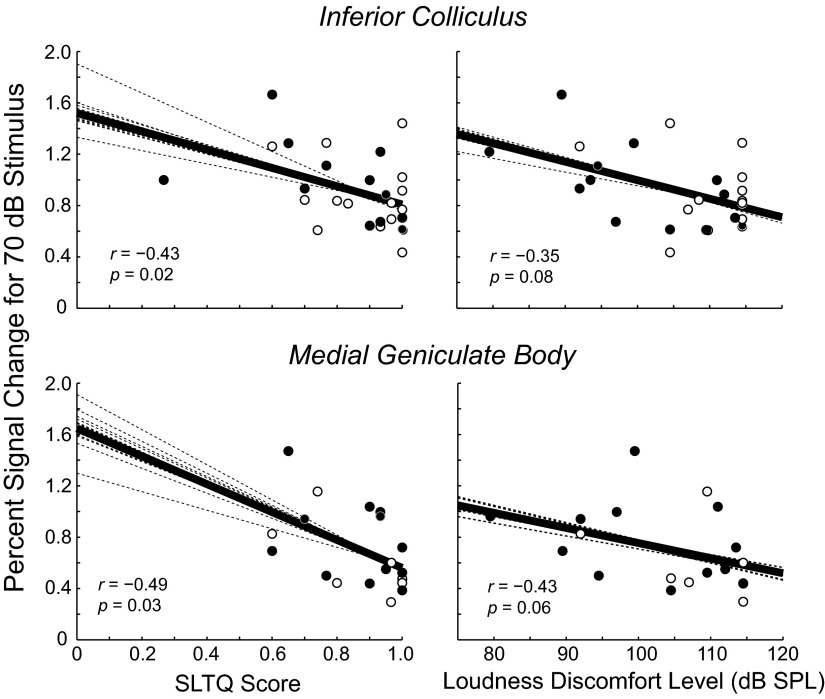

Figure 4 shows percent signal change to the 70 dB SPL sound stimulus plotted versus SLTQ score (left) and LDL (right) for the two subcortical structures that showed activation in a majority of subjects: IC and MGB (IC: 27 of 27 subjects; MGB: 19 of 27 subjects). The points in each panel correspond to individual subjects (tinnitus, ●; non-tinnitus, ○). The dark solid line in each panel is a linear fit to the data, whereas the lighter dotted lines each show what the fit would be if one of the data points were absent. There was a clear correlation between percent signal change and LDL and SLTQ score: percent change in IC and MGB increased with decreases in both of these measures. The fact that this trend is apparent in all of the dotted line fits to the data indicates that it is not reliant on any one data point. The correlation between percent signal change and SLTQ score was statistically significant in both IC and MGB (P = 0.02 and 0.03, respectively; Spearman correlation) and the correlation between MGB activation and LDL was nearly so (P = 0.06; correlation coefficients and P values are at the lower left of each panel in Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Activation in the IC and MGB increased with decreasing SLTQ score (left) and LDL (right). Stimulus level: 70 dB SPL. Each symbol in each panel corresponds to an individual tinnitus (filled symbol) or non-tinnitus (unfilled) subject. The solid line is a linear fit to all of the data. Spearman's coefficient and associated P value are given in the bottom left of each plot. Each dotted line is the result of a linear fit to all but 1 data point; a different data point was omitted for each line.

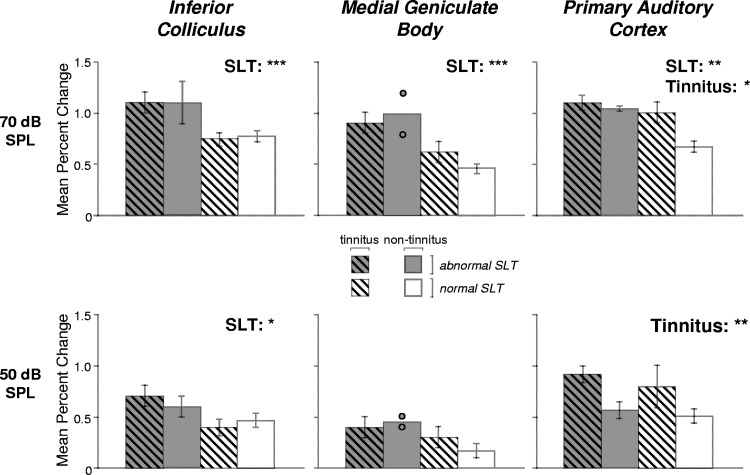

The dependence of percent signal change in the IC and MGB on SLT was confirmed by a complementary analysis that involved classifying tinnitus and non-tinnitus subjects into two SLT groups (normal and abnormal). Classification was based on LDL, SLTQ score, and whether subjects found the 80 dB SPL stimulus presented during scanning tolerable (see Fig. 3). Figure 5 (top row, left) shows the average percent signal change at 70 dB SPL in the IC for each of the four resulting subject groups: tinnitus and abnormal SLT, non-tinnitus and abnormal SLT, tinnitus and normal SLT, and non-tinnitus and normal SLT. Average percent change was greater for the two groups with abnormal SLT (Fig. 5, top left, 2 left-most bars) than for the two with normal SLT (2 right-most bars). A similar trend across groups was also apparent for MGB at 70 dB (Fig. 5, top middle).

Fig. 5.

Auditory activation in subject groups defined by SLT and tinnitus. Sound-evoked activation of the IC, MGB, and PAC showed a significant effect of SLT. PAC also showed a significant effect of tinnitus. The height of each bar indicates the mean percent signal change in response to 70 dB SPL (top row) or 50 dB SPL (bottom row) sound in IC (left column), MGB (middle column), or PAC (right column) for 1 of 4 subject groups defined based on SLT and tinnitus. Each subject contributed a single value to the mean. Error bars indicate ±SE. For MGB in the non-tinnitus, abnormal SLT group, circles indicate individual subject data because only 2 subjects contributed to the mean. Results of a 2-way ANOVA (tinnitus × SLT) are indicated at top right of each panel as follows: ***P ≤ 0.005, **P ≤ 0.01, *P ≤ 0.05.

At 70 dB, the two groups with normal SLT, one with tinnitus and one without, showed comparable percent signal change in both the IC and MGB, suggesting that there was little or no effect of tinnitus on the sound-evoked activation levels of these structures. This was confirmed by a two-way ANOVA (tinnitus × SLT) showing a significant effect of SLT (IC: P = 0.002, MGB: P = 0.004) but not tinnitus (P ≥ 0.7) and no interaction between these variables (P ≥ 0.4).

Figure 5 (bottom left and middle) shows percent signal change in the IC and MGB for each subject group at the lower stimulus level of 50 dB SPL. In the IC, average activation showed a distribution across the four subject groups defined by tinnitus and SLT that was qualitatively similar to the distribution for 70 dB (Fig. 5, left, compare top and bottom rows). A two-way ANOVA of the 50 dB data showed a significant effect of SLT (P = 0.03) but not tinnitus (P = 0.8). The 50 dB data for MGB showed a distribution across subject groups that was qualitatively similar to the 70 dB data but did not show statistically significant effects of SLT (P = 0.2, 2-way ANOVA) or tinnitus (P = 0.7), likely because of the lower percent signal changes produced generally by the 50 dB stimulus.

Even though eight of the subjects with abnormal SLT declined to be imaged with the 80 dB stimulus, activation at 80 dB SPL could still be compared between the two groups with normal SLT. Mean activation at 80 dB (Table 2) was similar for these two groups in both the IC (1.0 vs. 0.97%) and MGB (0.8 vs. 0.7%) and did not differ significantly (P ≥ 0.8; Wilcoxon rank-sum). Thus the 80 dB data supported the data at lower levels in indicating no effect of tinnitus on sound-evoked activation levels in the IC and MGB.

Table 2.

Percent signal change for each subject group, structure, and stimulus level

| Structure and Stimulus Level, dB SPL | Tinnitus, Abnormal SLT (n = 7) | Nontinnitus, Abnormal SLT (n = 5) | Tinnitus, Normal SLT (n = 6) | Nontinnitus, Normal SLT (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC 50 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 0.46 ± 0.07 |

| IC 70 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.74 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.06 |

| IC 80 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.97 ± 0.05 | ||

| MGB 50 | 0.4 ± 0.1 (6)1 | 0.45 (0.4, 0.5)2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.17 ± 0.07 (5) |

| MGB 70 | 0.9 ± 0.1 (6) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.45 ± 0.05 (5) |

| MGB 80 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 (5) | ||

| PAC 50 | 0.91 ± 0.08 | 0.57 ± 0.08 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.51 ± 0.07 |

| PAC 70 | 1.10 ± 0.07 | 1.04 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.67 ± 0.05 |

| PAC 80 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.94 ± 0.09 | ||

| HGal 50 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| HGal 70 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

| HGal 80 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | ||

| PT 50 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| PT 70 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| PT 80 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.87 ± 0.09 | ||

| AMA 50 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| AMA 70 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.58 ± 0.09 |

| AMA 80 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.73 ± 0.09 (8)3 | ||

| ALA 50 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.3 (4) | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| ALA 70 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 (4) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| ALA 80 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

Values are means ± SE.

The number of subjects (shown in parantheses) contributing to the mean is indicated whenever it is less than the total.

Only two subjects contributed to the mean, so the data for each are given instead of an SE.

Anatomical ROI met criterion (see text) for being assigned a percent change of zero at 50 dB and 70 dB but not 80 dB for one subject. SLT, sound-level tolerance; IC, inferior colliculus; MGB, medial geniculate body; PAC, primary auditory cortex; HGal, Heschl's gyrus; PT, planum temporale; AMA, anteromedial area; ALA, anterolateral area.

To address whether the activation might depend on some variable correlated with SLT rather than depending on SLT per se, the following analyses were performed. The IC and MGB activation data at 50 and 70 dB were cross-correlated with each of the following: age, threshold for the continuous noise stimulus, score on the anxiety inventory, and score on the depression inventory. Cross-correlation with these variables was performed separately for each of the two structures and each stimulus level. Although there was a nonsignificant tendency for IC activation at 70 dB to be correlated with age (r = −0.34; P = 0.08), none of the other cross-correlations showed even a trend (P ≥ 0.4; Spearman correlation). (Note that P value results of the correlations have not been corrected for multiple comparisons.) A three-way ANOVA (tinnitus × SLT category × age) also showed a tendency for IC activation at 70 dB to covary with age (P = 0.07; not corrected for multiple comparisons) but additionally confirmed a far more significant effect of SLT (P = 0.002) and none of tinnitus (P = 0.9). A three-way ANOVA was also performed on the activation data for each structure and stimulus level but replacing age with threshold, anxiety score, or depression score. The results again confirmed an effect of SLT, no effect of tinnitus, and, in most cases, no effect whatsoever of the third variable (P ≥ 0.1; not corrected). The only exception was an effect of anxiety in the IC data. However, this effect (50 dB: P = 0.05; 70 dB: P = 0.002) was far less significant than that of SLT (P = 0.005 and P = 0.00003, respectively). The results of the analysis suggest that age and anxiety may have played some role in determining the magnitude of IC activation, but indicate that, among the factors tested, the dominant factor in the IC, and indeed the only apparent factor in the MGB, was SLT. Note that SLT would have emerged as even more dominant if the P value results of the analyses had been corrected for multiple comparisons (and hence increased), especially because the correction is only applicable to those variables not hypothesized, a priori, to be related to activation (i.e., age, threshold, depression, anxiety, but not SLT, tinnitus).

Activation in auditory cortex: dependencies on both SLT and tinnitus

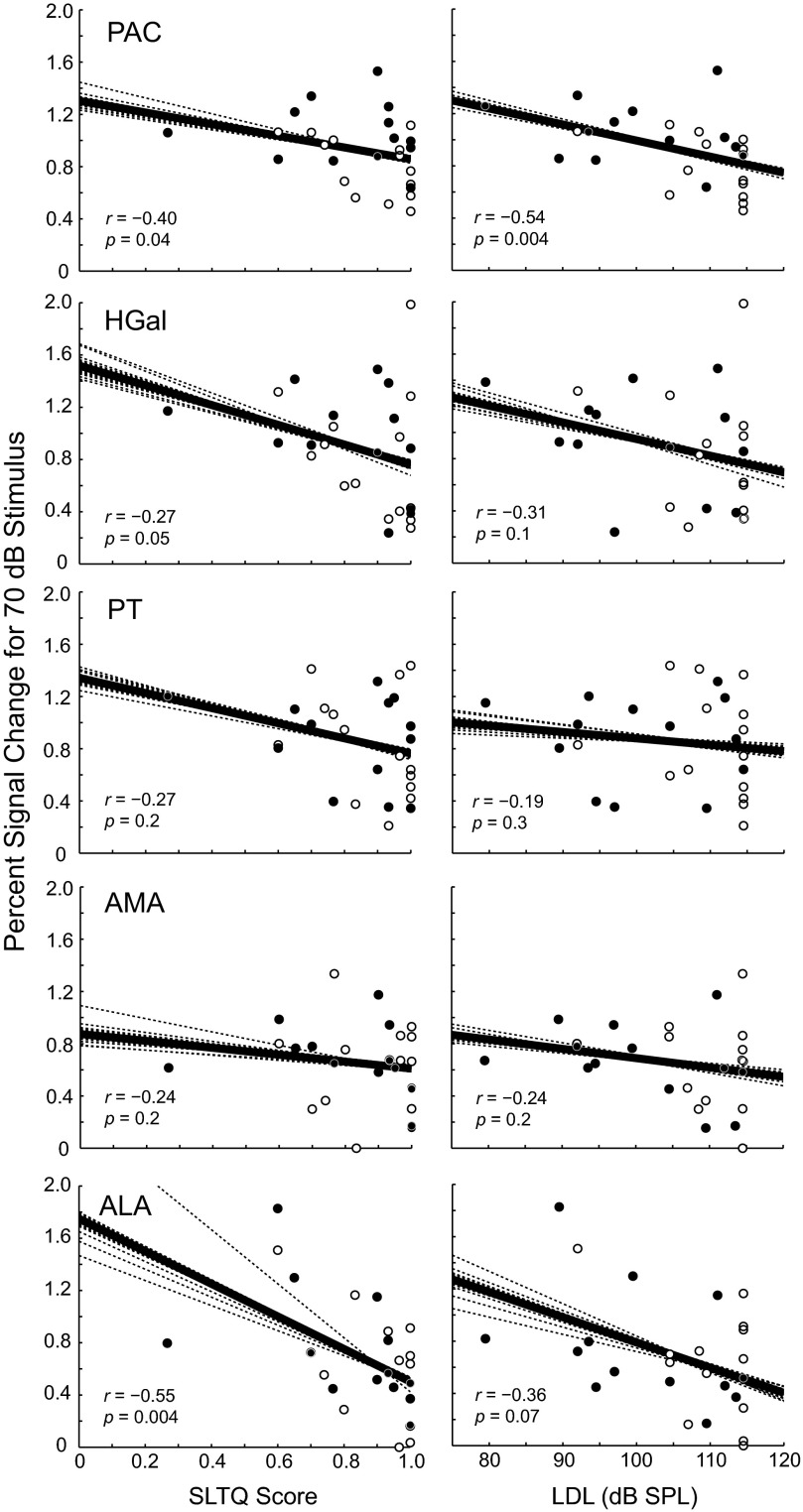

Figure 6 shows percent signal change for the 70 dB SPL stimulus plotted versus SLTQ score (left column) and versus LDL (right column) for the five cortical areas, which together contained almost all of the activation on the superior temporal lobe (PAC, HGal, PT, AMA, ALA; defined in Fig. 2B). As in the IC and MGB, percent signal change in the cortical areas tended to increase with decreasing LDL and with decreasing SLTQ score. Such trends were significant in three regions: PAC, which overlaps primary auditory cortex, and HGal and ALA, which comprise primary-like cortical areas anterior to PAC. In all three regions, the Spearman correlation between percent signal change at 70 dB and one or both of the SLT measures was significant (P ≤ 0.05; see bottom left of each panel in Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Activation in auditory cortical regions tended to increase with decreasing SLTQ score (left) and LDL (right). Stimulus level: 70 dB SPL. See Fig. 4 caption for explanation of symbols and line fits.

In contrast to IC and MGB, some of the cortical areas showing an effect of SLT also showed an effect of tinnitus. Data for one region showing dependencies on both variables, PAC, can be seen in Fig. 5 (top right), where, for the 70 dB stimulus, percent signal change in the tinnitus, normal SLT group is close in height to that of the groups with abnormal SLT and greater than that of the group with neither tinnitus nor abnormal SLT. A two-way ANOVA (tinnitus × SLT) on PAC activation at 70 dB showed a significant effect of tinnitus (P = 0.02) and SLT (P = 0.006; no significant interaction, P = 0.09). Mean activation of HGal and PT at 70 dB showed average differences between subject groups that resembled those of PAC (Table 2). However, only PAC showed statistically significant effects of tinnitus at 70 dB (P ≥ 0.7 for the other cortical ROIs).

For the 50 dB stimulus, the dependence of PAC activation on tinnitus was even more apparent than at 70 dB, and one other cortical region, HGal, also showed significant effects of tinnitus. The dependence of PAC activation at 50 dB on tinnitus can be seen in Fig. 5 (bottom right), where the two groups with tinnitus showed similar percent changes to the 50 dB stimulus and greater percent changes than the two non-tinnitus groups. A two-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of tinnitus in PAC (P = 0.006) but not of SLT (P = 0.4; no interaction, P = 0.8). HGal, the region immediately anterolateral to PAC showed similar results: a significant effect of tinnitus (P = 0.02) and no effect of SLT (P = 0.6; no interaction, P = 0.7). Neither PAC nor HGal activation at 50 dB was significantly correlated with age, threshold for the continuous noise stimulus, anxiety (P ≥ 0.1), or depression (P = 0.08; not corrected for multiple comparisons). A three-way ANOVA, tinnitus × SLT × age, sex, threshold, anxiety, or depression, showed no significant effect of any of these potentially confounding variables (HGal: P ≥ 0.3; PAC: P ≥ 0.2; not corrected) while confirming a significant effect of tinnitus (HGal: P ≤ 0.03; PAC: P ≤ 0.03). These analyses indicate that tinnitus, more than any other variable considered, influenced PAC and HGal activation levels at 50 dB.

DISCUSSION

Our subject cohort comprising people with and without tinnitus showed sound-evoked fMRI activation in the IC, MGB, and PAC that was significantly correlated with measures of subjects' SLT: LDL and SLTQ score. Importantly, the correlations were shown in subjects with clinically normal hearing thresholds using the same physical stimulus levels in all subjects. Furthermore, the correlations could not be attributed to other factors potentially affecting the magnitude of fMRI activation, including stimulus threshold, depression, anxiety, and age. Thus the results provide strong evidence for a relationship between the magnitude of sound-evoked fMRI activation in the auditory pathway and SLT. The nature of the relationship was as follows: activation from sound increased with decreasing SLT.

Physiological correlate of hyperacusis

These results are, to our knowledge, the first to directly show a physiological correlate of abnormal SLT, that is, hyperacusis. Our results pertain specifically to people with mild hyperacusis, because hyperacusis was never the primary complaint among the tinnitus patients recruited for this study and was self-recognized by only a few of the subjects who ultimately showed abnormal SLT under the controlled conditions of our testing. Interestingly, we had difficulty finding subjects with tinnitus and completely normal SLT as defined by our behavioral tests. Although anecdotal, this observation nevertheless suggests the possibility that abnormal SLT, by which we mean hyperacusis ranging from mild to severe, may be more directly related to tinnitus than generally appreciated.

Reinterpretation of previous fMRI studies of tinnitus patients

Whereas sound-evoked activation in the IC and MGB was correlated with SLT, it was not correlated with tinnitus. This result suggests that previous demonstrations of elevated sound-evoked fMRI activation in the IC of tinnitus subjects were likely related to abnormal perception of the sound stimulus rather than the phantom perception of sound, that is, tinnitus (Lanting et al. 2008; Melcher et al. 2009). We suspect that a sizable fraction of the tinnitus subjects in these previous studies had abnormal SLT, which would account for the previous findings of elevated activation in the subject groups with tinnitus.

Dependence of PAC activation on tinnitus: possible role of attention

Activation in PAC resembled that of the IC and MGB in showing an effect of SLT but also differed from the subcortical activation in two respects. First, PAC only showed a dependence on SLT at 70 dB; activation at the lower level of 50 dB showed no such dependence. Thus the activation enhancements seen subcortically at 50 dB were not simply reflected verbatim in cortex. The difference between subcortex and cortex could reflect a difference in the population neural coding of loudness and/or a difference in the fraction of total neural activity allocated to coding loudness versus other stimulus attributes, for instance. Second, PAC differed from the IC and MGB in showing a dependence of activation on tinnitus in addition to SLT. In particular, at both 50 and 70 dB, activation in the subject groups with tinnitus was elevated regardless of whether SLT was normal or abnormal. We can only speculate as to why this was the case, but one possibility is suggested by neuroimaging data showing that sound produces increased activation in auditory cortex during selective attention to the auditory domain (Degerman et al. 2006; Krumbholtz et al. 2007; Paltoglou et al. 2009; Woodruff et al. 1996). Perhaps the increased cortical activation among those with tinnitus reflected sustained “overattention” to the auditory domain that resulted in enhanced responses to sound. In other words, the elevations in sound-evoked cortical activation that occurred with tinnitus irrespective of SLT might not reflect the tinnitus percept per se but rather reflect attention drawn to the auditory domain by the presence of tinnitus. The absence of tinnitus-related effects in subcortical centers in our data is consistent with this attention-based hypothesis for the tinnitus-related effects in PAC because attentional state has a far subtler effect on subcortical compared with cortical auditory fMRI activation (Rinne et al. 2008).

However, undue attention drawn to the auditory domain by the tinnitus percept is just one possible explanation for the tinnitus-related elevations in PAC activation. Others include the possibility that cause and effect are reversed such that the tinnitus percept results because PAC activity is enhanced by overattention to the auditory domain (e.g., spontaneous activity is increased to the point that it is heard as sound). Also, enhancement of PAC activity and tinnitus perception might build on one another. The latter situation might occur in a manner suggested by the well-known “vicious cycle” of tinnitus and its hypothesized neurophysiological substrates (tinnitus causes distress; distress causes tinnitus; Jastreboff et al. 1996). For instance, aberrant auditory activity that is not consciously perceived as sound might become perceptible because it is assigned behavioral significance through what amounts to implicit aversive conditioning. The emergent percept reinforces the aversive response, enhancing the aberrant activity and hence the percept, and so on.

Cortical activation dependencies on SLT, tinnitus: core versus belt

Whereas cortical activation dependencies on SLT and tinnitus were most evident in PAC, other cortical ROIs showed dependencies as well. Because the cortical ROIs of this study were defined to follow the organization of auditory cortex into a core region of primary (PAC) and primary-like (HGal, ALA) areas and belt regions surrounding the core medially (AMA) and laterally (PT) (Kaas and Hackett 2000), these dependencies can be examined with respect to the core/belt distinction. Within the core, HGal and ALA, in addition to PAC, showed dependencies on SLT, and in the case of HGal, a dependence on tinnitus. In contrast, ROIs corresponding to the belt (AMA, PT) showed no significant activation dependencies on SLT or tinnitus. Thus any cortical dependencies on SLT and tinnitus seemed limited to the core of auditory cortex.

Relationship to animal work

The elevations in activation to sound seen in this study are highly suggestive of abnormal gain within the auditory pathway. Previous electrophysiological data from animals showing activity elevations in inferior colliculus and/or cortex in response to pharmacological agents or auditory peripheral damage offer some clues as to how such a gain might arise (Salvi et al. 1990, 2000; Syka et al. 1994). Perhaps the most directly relevant animal work is that showing abnormally elevated responses to sound in the inferior colliculus of acoustically traumatized animals, a finding potentially relevant to this study of subjects with normal audiograms, because it was seen for sound frequencies at which threshold was normal (i.e., for stimulus frequencies below the range of any hearing loss). The elevated responses in animals have been postulated to arise as a result of reduced GABA-mediated inhibition, a possible mechanism by which the elevations in fMRI activation seen here might arise.

Relationship to previous studies relating auditory cortical activation and loudness

Two previous studies showing increased activation of auditory cortex with increased sound loudness—as distinct from physical sound level—warrant consideration in light of these results. One study found that the amount of activation produced by a variety of pure and complex tone stimuli was better correlated with the calculated loudness of the sound stimuli than to their level (Hall et al. 2001). The other showed that activation increased similarly with loudness, but not level, for two subject groups: normal hearing listeners and hearing impaired listeners in whom loudness grew abnormally with stimulus level because of recruitment (Langers et al. 2007). Both studies indicated that the degree to which auditory cortex activates is directly related to the perceived loudness of a sound stimulus. Although these results are somewhat different in that they show a correlation between activation and the upper limit of comfortable loudness, they can be seen to be consistent with a dependence of activation on loudness by noting the following. Having normal thresholds for detecting sound, as in this study, but reaching uncomfortable loudness at a lower-than-normal sound level, implies the perception of greater-than-normal loudness for at least some sound levels below those deemed uncomfortable. Thus the elevated cortical activation seen for a stimulus level below uncomfortable (70 dB SPL) in subjects with abnormal SLT (Fig. 5, top right) may reflect the fact that the perceived loudness of the sound evoking the activation was greater than normal. Given the relationship between loudness and auditory midbrain activation described in the introduction, the elevated inferior colliculus activation seen for 50 and 70 dB SPL in subjects with abnormal SLT may also reflect abnormal (that is, heightened) loudness perception.

Clinical implications

These results provide an entrance to understanding and quantifying physiological effects of candidate treatments for tinnitus and hyperacusis, perhaps most particularly sound therapies designed to promote a reduction in central auditory gain (Davis et al. 2007; Norena and Chery-Croze 2007). Such therapies, which involve the delivery of controlled sounds in a prescribed manner, along with counseling, have been shown to ameliorate hyperacusis and reduce tinnitus severity as assessed from behavioral tests and questionnaire evaluations. Based on these results, we hypothesize that such improvements coincide with reductions in sound-evoked fMRI activation in the auditory pathway. This hypothesis could be tested by comparing measurements of sound-evoked fMRI activation, like those of this study, before and after administration of sound therapy.

A variety of clinical conditions are characterized by disordered perceptions that, like tinnitus and hyperacusis, have been hypothesized to arise from abnormal elevations in neural activity in the CNS. These include the phantom sensation of an amputated limb and chronic neuropathic pain, conditions analogous to tinnitus (Møller 2007). They also include conditions analogous to hyperacusis: the heightened sensitivity to light occurring with migraine and the lowered thresholds for stimulated pain (e.g., from pressure, thermal stimulation) occurring with chronic pain (Kosek et al. 1996). In some of these cases of disordered perception, there is evidence indicating underlying elevations in neural activity (Ambrosini and Schoenen 2006; Cook et al. 2004). These previous data combined with these results reinforce proposals that the neurophysiology behind tinnitus and hyperacusis may not be entirely unique to the auditory system but may rather have strong commonalities with the disordered perceptions characterizing other clinical conditions involving the visual and somatosensory domains.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the American Tinnitus Association, the Tinnitus Research Initiative, Jack and Shelley Blais, Kenneth Griffin, and National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants T32 DC-00038 and P30 DC-005209. Partial support was also provided by National Center for Research Resources Grant P41RR14075 and the Mental Illness and Neuroscience Discovery Institute.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Tyler for very helpful discussions concerning behavioral measurements and questionnaires. We also thank B. Norris for assistance with data collection and figure making, D. Langers for assistance with data collection and comments on an earlier version of this manuscript, E. Özdemir for assistance with data collection, and C. Shera for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Ambrosini and Schoenen, 2006. Ambrosini A, Schoenen J. Electrophysiological response patterns of primary sensory cortices in migraine. J Headache Pain 7: 377–388, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold et al., 1996. Arnold W, Bartenstein P, Oestreicher E, Romer W, Schwaiger M. Focal metabolic activation in the predominant left auditory cortex in patients suffering from tinnitus: a PET study with [18F]deoxyglucose. J Otorhinolaryngol 58: 195–199, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baguley, 2003. Baguley DM. Hyperacusis. J R Soc Med 96: 582–585, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck et al., 1988. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 56: 893–897, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck et al., 1961. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. J Arch Gen Psychiatry 4: 561–571, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain, 1939. Brittain FH. The loudness of continuous spectrum noise and its application to loudness measurements. J Acoust Soc Am 11: 113–117, 1939 [Google Scholar]

- Cook et al., 2004. Cook DB, Lange G, Ciccone DS, Liu W-C, Steffener J, Natelson BH. Functional imaging of pain in patients with primary fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 31: 364–378, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox et al., 1997. Cox RM, Alexander GC, Taylor IM, Gray GA. The contour test of loudness perception. Ear Hearing 18: 388–400, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis et al., 2007. Davis PB, Paki B, Hanley PJ. Neuromonics tinnitus treatment: third clinical trial. Ear Hearing 28: 242–259, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degerman et al., 2006. Degerman A, Rinne T, Salmi J, Salonen O, Alho K. Selective attention to sound location or pitch studied with fMRI. Brain Res 1077: 123–134, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmister et al., 1999. Edmister WB, Talavage TM, Ledden PJ, Weisskoff RM. Improved auditory cortex imaging using clustered volume acquisitions. Hum Brain Mapp 7: 89–97, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton and Pandya, 2007. Fullerton BC, Pandya DN. Architectonic analysis of the auditory-related areas of the superior temporal region in human brain. J Comp Neurol 504: 470–498, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu et al., 2008. Gu J, Halpin C, Nam E-C, Levine RA, Melcher JR. Elevated sound-evoked fMRI activation in the auditory midbrain of people with tinnitus and hyperacusis. Assoc Res Otolaryngol 31: 336, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes et al., 1998. Guimaraes AR, Melcher JR, Talavage TM, Baker JR, Ledden P, Rosen BR, Kiang NYS, Fullerton BC, Weisskoff RM. Imaging subcortical auditory activity in humans. Hum Brain Mapp 6: 33–41, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall et al., 1999. Hall DA, Haggard MP, Akeroyd MA, Palmer AR, Summerfield AQ, Elliott MR, Gurney EM, Bowtell RW. “Sparse” temporal sampling in auditory fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 7: 213–223, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall et al., 2001. Hall DA, Haggard MP, Summerfield AQ, Akeroyd MA, Palmer AR. Functional magnetic resonance imaging measurements of sound-level encoding in the absence of background scanner noise. J Acoust Soc Am 109: 1559–1570, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms and Melcher, 2002. Harms MP, Melcher JR. Sound repetition rate in the human auditory pathway: representations in the waveshape and amplitude of fMRI activation. J Neurophysiol 88: 1433–1450, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley et al., 2005. Hawley ML, Melcher JR, Fullerton BC. Effects of sound bandwidth on fMRI activation in human auditory brainstem nuclei. Hear Res 204: 101–110, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff et al., 1996. Jastreboff PJ, Gray WC, Gold SL. Neurophysiological approach to tinnitus patients. Am J Otol 17: 236–240, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach et al., 2004. Kaltenbach JA, Zhang J, Zacharek MA. Neural correlates of tinnitus. In: Tinnitus: Theory and Management, edited by Snow JB. London: BC Decker, 2004, p. 141–161 [Google Scholar]

- Kass and Hackett, 2000. Kass JH, Hackett TA. Subdivisions of auditory cortex and processing streams in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 11793–11799, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosek et al., 1996. Kosek E, Ekholm J, Hansson P. Sensory dysfunction in fibromyalgia patients with implications for pathogenic mechanisms. Pain 68: 375–383, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumbholtz et al., 2007. Krumbholtz K, Eickhoff SB, Fink GR. Feature- and object-based attentional modulation in the human auditory “where” pathway. J Cogn Neurosci 19: 1721–1733, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langers et al., 2007. Langers DRM, van Dijk P, Schoenmaker ES, Backes WH. fMRI activation in relation to sound intensity and loudness. Neuroimage 35: 709–718, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanting et al., 2008. Lanting CP, De Kleine E, Bartels H, Van Dijk P. Functional imaging of unilateral tinnitus using fMRI. Acta Otolaryngol 128: 415–421, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine and Kiang, 1995. Levine RA, Kiang NYS. A conversation about tinnitus. In: Mechanisms of Tinnitus, edited by Moller AR, Vernon J. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1995, p. 149–161 [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood et al., 1998. Lockwood AH, Salvi RJ, Coad ML, Towsley ML, Wack DS, Murphy BW. The functional neuroanatomy of tinnitus. Neurology 50: 114–120, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher et al., 2009. Melcher JR, Levine RA, Bergevin C, Norris B. The auditory midbrain of people with tinnitus: abnormal sound-evoked activity revisited. Hear Res 257: 63–74, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller, 2007. Møller AR. Tinnitus and pain. Prog Brain Res 166: 47–53, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norena and Chery-Croze, 2007. Norena AJ, Chery-Croze S. Enriched acoustic environment rescales auditory sensitivity. Neuroreport 18: 1251–1255, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield, 1971. Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropyschologia 9: 97–113, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paltoglou et al., 2009. Paltoglou AE, Sumner CJ, Hall DA. Examining the role of frequency specificity in the enhancement and suppression of human cortical activity by auditory selective attention. Hear Res 257: 106–118, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, 1951. Pollack I. On the threshold and loudness of repeated bursts of noise. J Acoust Soc Am 23: 646–650, 1951 [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher et al., 2001. Rademacher J, Morosan P, Schormann T, Schleicher KA, Werner C, Freund HJ, Zilles K. Probabilistic mapping and volume measurement of human primary auditory cortex. Neuroimage 13: 669–683, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne et al., 2008. Rinne T, Balk MH, Koistinen S, Autti T, Alho K, Sams M. Auditory selective attention modulates activation of human inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol 100: 3323–3327, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi et al., 1990. Salvi RJ, Saunders SS, Gratton MA, Arehole S, Powers N. Enhanced response amplitudes in the inferior colliculus of the chinchilla following acoustic trauma. Hear Res 50: 245–258, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi et al., 2000. Salvi RJ, Wang J, Ding D. Auditory plasticity and hyperactivity following cochlear damage. Hear Res 147: 261–274, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigalovsky et al., 2006. Sigalovsky IS, Fischl B, Melcher JR. Mapping an intrinsic MR property of gray matter in auditory cortex of living humans: a possible marker for primary cortex and hemispheric differences. Neuroimage 32: 1524–1537, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigalovsky and Melcher, 2006. Sigalovsky IS, Melcher JR. Effects of sound level on fMRI activation in human brainstem, thalamic and cortical centers. Hear Res 215: 67–76, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syka et al., 1994. Syka J, Rybalko N, Popelar J. Enhancement of the auditory cortex evoked responses in awake guinea pigs after noise exposure. Hear Res 78: 158–168, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler et al., 2003. Tyler RS, Bergan C, Preece J, Nagase S. Audiologische messmethoden de hyperakusis. In: Hyperakusis 6, edited by Nelting M. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme Verlag, 2003, p. 39–46 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson et al., 1991. Wilson PH, Henry J, Bowen M, Haralambous G. Tinnitus reaction questionnaire: psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. J Speech Hear Res 34: 197–201, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff et al., 1996. Woodruff PWR, Benson RR, Bandettini PA, Kwong KK, Howard RJ, Talavage T, Belliveau J, Rosen BR. Modulation of auditory and visual cortex by selective attention is modality-dependent. Neuroreport 7: 1909–1913, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker et al., 1957. Zwicker E, Flottorp G, Stevens SS. Critical band width in loudness summation. J Acoust Soc Am 29: 548–558, 1957 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.