Abstract

Distractions affect postural control, but this mechanism is not well understood. Diversion of resources during cognitive stress may lead to decreased motor drive and postural muscle tone. This may appear as decreased postural stiffness and increased postural sway amplitude. We hypothesized that dual tasking leads to decreased stiffness and increased sway amplitude. Postural sway (center of pressure; COP) data were used from 724 participants aged 77.9 ± 5.3 yr, a representative sample of community-dwelling older adults, the MOBILIZE Boston Study cohort. Subjects stood barefoot with eyes open for 30 s per trial on a force plate. Five trials were performed each with and without a serial subtractions-by-3 task. Sway data were fit to a damped oscillator inverted pendulum model. Amplitudes (COP and center of mass), mechanical stiffness, and damping of the sway behavior were determined. Sway amplitudes and damping increased with the dual task (P < 0.001); stiffness decreased only mediolaterally (P < 0.001). Those with difficulty doing the dual task exhibited larger sway and less damping mediolaterally (P ≤ 0.001) and an increased stiffness with dual task anteroposteriorly (interaction P = 0.004). Dual task could still independently explain increases in sway (P < 0.001) after accounting for stiffness changes. Thus the hypothesis was supported only in mediolateral sway. The simple model helped to explain the dual task related increase of sway only mediolaterally. It also elucidated the differential influence of cognitive function on the mechanics of anteroposterior and mediolateral sway behaviors. Dual task may divert the resources necessary for mediolateral postural control, thus leading to falls.

INTRODUCTION

The injuries associated with falls contribute to >90% of all hip fractures and are the primary cause of accidental deaths in those ≥65 yr (Fuller 2000; Sterling et al. 2001). Increased postural sway during quiet standing is associated with elevated fall risk in older adults (Maki et al. 1994; Melzer et al. 2004). Cognitive distractions that divert attentional resources seem to impair postural control (Brown et al. 1999) and thus may increase fall risk in older adults. However, the mechanism by which cognitive distractions affect postural sway or fall risk is not clear (Melzer et al. 2001; Prado et al. 2007; Woollacott and Shumway-Cook 2002). In a healthy person, one task such as postural control may be performed requiring minimal attention, while the person is attentive to the secondary “dual task” such as a cognitive task. In the context of postural control, the performance of a secondary dual task is generally associated with increased postural sway, that is, the primary postural task suffers a dual task decrement.

However, the neurophysiological mechanisms responsible for the dual-task decrement on postural control are not yet clear (Herath et al. 2001). Cognitive distractions may interfere with the control of standing posture by competing for the same pool of neural resources. Attention, executive function, and the prefrontal cortex have been implicated as possible resources that are taxed (Yogev-Seligmann et al. 2008). The changes in postural behavior, particularly sway amplitude, with distractions suggests the lack of these attentional or neuronal resources during dual task may lead to inadequate or inappropriate activation of postural musculature (Donker et al. 2007; Melzer et al. 2001; Prado et al. 2007). However, to develop a better neurophysiological description of the changes in postural control and how these changes affect the ability to withstand perturbations that may cause falls, we also need a better dynamical and mechanical description of the postural sway behavior during the dual task.

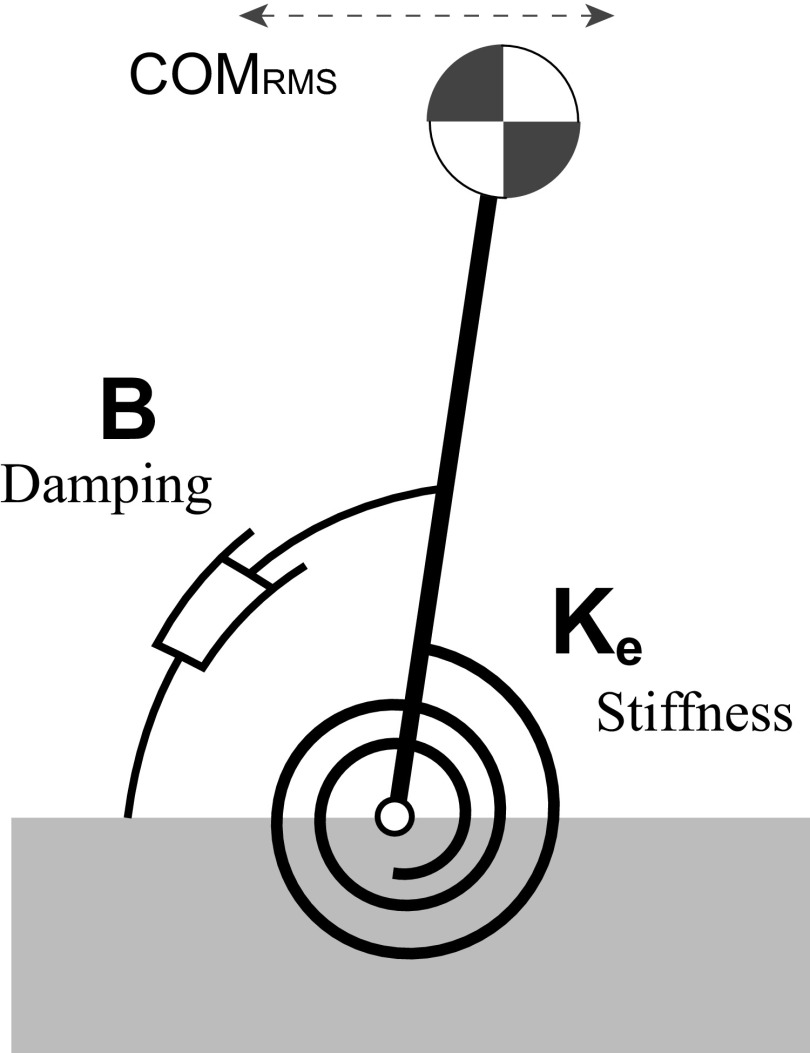

To describe the role of dual task on the mechanics of postural sway, we consider a simple model of standing postural control where upright standing is modeled as an damped-oscillator inverted pendulum that is held upright through mechanical stiffness in the ankle (Winter et al. 1998). This mechanical stiffness that keeps the body upright may reflect muscle tone or tendon properties and also reflexive and anticipatory control mechanisms (Fitzpatrick and Gandevia 2005; Loram et al. 2004, 2009; Morasso and Schieppati 1999). This model predicts that decreased stiffness would result in increased sway amplitude and vice versa. Thus we hypothesize that the changes in postural sway amplitudes due to dual task are mediated by the changes in postural stiffness.

In this study, we tested the effect of dual task on postural stiffness as determined from the inverted pendulum model of standing postural control in a representative sample of community-dwelling older adults. Our first goal was to examine the effect of dual task on the postural stiffness using a serial subtractions task. Second, we looked at the ability of the damped oscillator inverted pendulum model to explain the effect of dual task on postural dynamics.

METHODS

Subjects

This current study is a secondary analysis of the data from the MOBILIZE Boston Study (MBS), which stands for maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and zest in the elderly of Boston, a prospective cohort study examining risk factors for falls, including pain, cerebral hypoperfusion, and foot disorders in the older population. The study includes a representative population sample of 765 volunteers age ≥70 from the Boston area. After providing informed consent as approved by the Hebrew SeniorLife Institutional Review Board, all subjects underwent a standardized evaluation. A full description of the study design and the collected data are presented elsewhere (Leveille et al. 2008). Of the 765, static posturography data were used from 724 participants (Table 1). Of the 41 participants of the cohort of 765 that were not considered for analysis, 16 were unable to stand for 30 s at a time, 7 refused, and 3 had an amputation. Also data from 15 were excluded due to equipment problems.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and biomechanical descriptions

| S3 Able | S3 Unable | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 444 (61.3) | 280 (38.7) | |

| Age (years) | 77.38 (5.05) | 78.8 (5.66) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 261 (58.8) | 199 (71.0) | <0.001* |

| Non-white race | 104 (37.55) | 54 (12.16) | <0.001* |

| <HS education | 17 (3.83) | 60 (21.66) | <0.001* |

| Daily alcohol use | 78 (17.6) | 20 (7.1) | <0.001* |

| Vision ≤20/50 | 29 (6.67) | 22 (8.09) | 0.55* |

| MMSE | 28.9 (1.82) | 25.39 (2.83) | <0.001 |

| TMT-A | 48.73 (23.37) | 68.6 (43.46) | <0.001 |

| TMT-B | 113.89 (58.98) | 191.36 (83.02) | <0.001 |

| CES-D-R | 49.94 (9.69) | 51.56 (10.19) | 0.033 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 1.01 (0.25) | 0.885 (0.234) | <0.001 |

| Urinary Incontinence | 181 (40.71) | 111 (39.6) | 0.94* |

| Sensory loss in feet | 42 (13.9) | 40 (14.3) | 0.068* |

| Fall history | 178 (40.1) | 91 (32.5) | 0.048* |

| Activities of daily Living: | |||

| No difficulty | 373 (84.0) | 201 (72.6) | <0.001** |

| Some difficulty | 52 (11.7) | 50 (17.9) | |

| Lots of difficulty | 19 (4.3) | 27 (9.8) | |

| Height, m | 1.65 (0.10) | 1.62 (0.09) | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 74.2 (15.15) | 72.73 (16.09) | 0.22 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.25 (4.87) | 27.78 (5.48) | 0.19 |

| Ia − AP, kg-m2 | 72.67 (21.11) | 68.25 (20.12) | 0.006 |

| Ia − ML | 73.47 (21.34) | 69.00 (20.34) | 0.006 |

| Leg Strength, N | 300.57 (125.15) | 270.83 (112.45) | 0.007 |

| n = 354 | n = 187 |

Mean (SD) or N (% of each S3 group) Vision: using Snellen chart score; MMSE, Folstein Mini-mental status exam score; TMT-A, time to complete Trailmaking Test Part A, test of information processing speed; TMT-B, time to complete Trailmaking Test Part B, test of executive function; CES-D-R, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale, Hopkins revision; BMI, body mass index; Ia, moment of inertia of the body about the ankle; Leg press strength from 1 RM (maximum repetition) trial;

using Fischer's exact test;

using Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test.

Balance assessment

Subjects stood barefoot with eyes open on a 6-dof force platform (Kistler 9286AA). Stance width was freely chosen, ∼30 cm on average. No visual target was specified. The center of pressure (COP) displacements under their feet, in both anteroposterior (AP) and mediolateral (ML) directions were sampled at 240 Hz. Subjects performed two sets of five quiet standing trials, 30 s each. One set included a cognitive task (dual task challenge). The order of the two sets was randomized. Trials were grouped by sets of five to minimize carryover effects between conditions.

The dual task challenge consisted of serial subtractions. Each subject was asked to verbally count backward by 3 from 500 during the 30 s trial (subtractions by 3, or S3). S3 paradigm is a classic neuropsychological test. Counting was started at 500 to provide enough numbers to be processed during the trial. In subsequent dual task trials, subjects continued the subtractions where they previously left off. Performance of the dual task was monitored by asking the subject to verbalize the answers. To keep the task difficulty similar between subjects, if five errors were made during this task, the test was modified by having them count backward by 1 from 500. Data from these trials were included in subsequent analyses as they were not significantly different from other trials (Kang et al. 2009). If the subject still made five errors, the task was switched to counting backward by 1 from 100. If subjects also failed this task, they were then asked to name items found at a supermarket. Subjects were instructed to prioritize on counting. Participants sat and rested for 1 min between trials.

Postural model

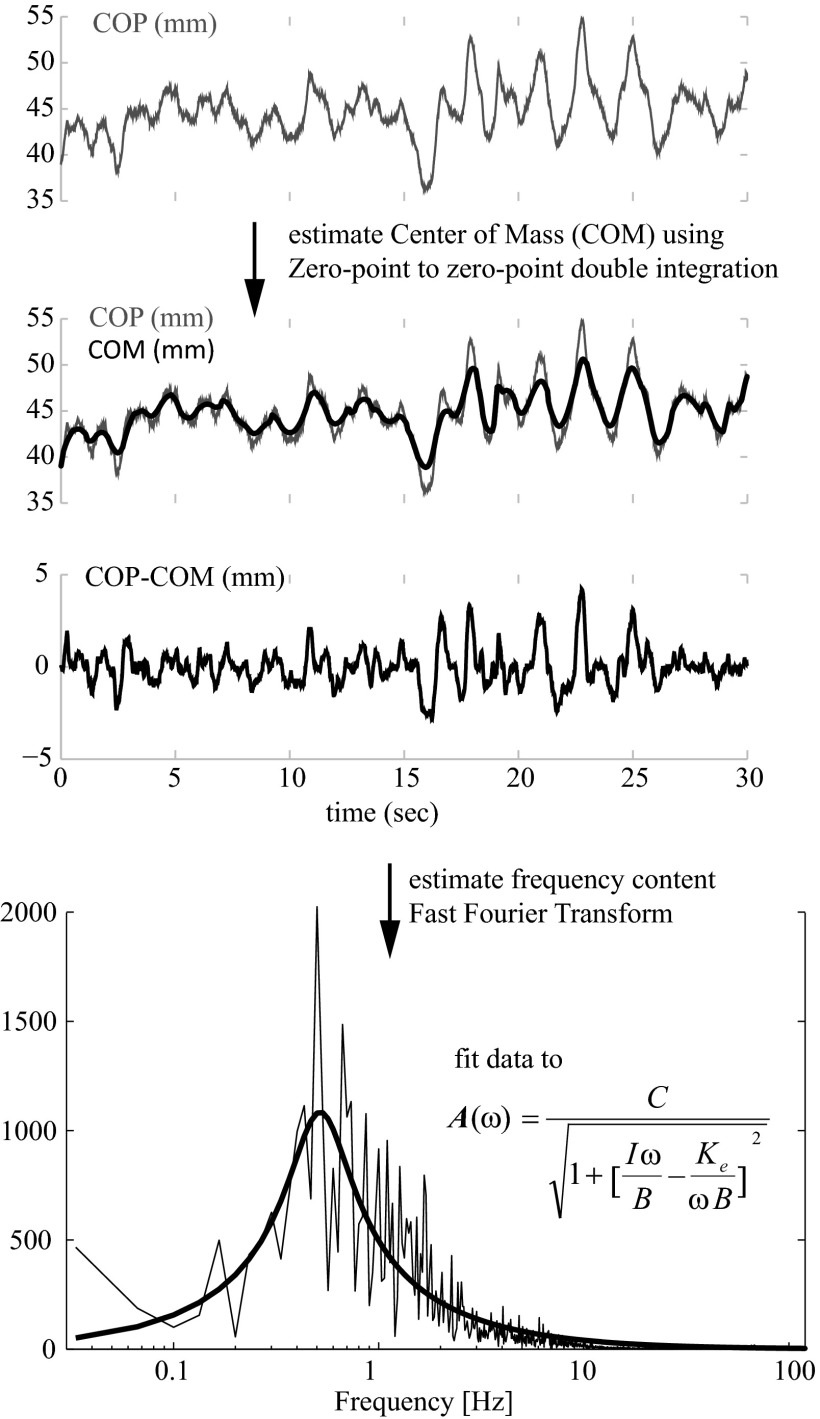

Postural model parameters were calculated from the COP data using methods described previously (Winter et al. 1998). Briefly, the postural system is modeled as an inverted pendulum with rotational stiffness and damping. This simple model of postural control can describes the basic mechanical behavior of the postural sway as a function of postural stiffness of the pendulum. Passive tissue properties and neurological control are simplified into the lumped stiffness and damping parameters (Fitzpatrick and Gandevia 2005; Loram et al. 2004, 2009; Morasso and Schieppati 1999). Movements of center of mass (COM) were estimated using the zero-point-to-zero-point double integration technique from the horizontal forces measured from the force platform (Lafond et al. 2004; Zatsiorsky and King 1997). This double integration technique was shown to be the most concordant with the estimates of the center of mass based on full-body motion capture (published RMS errors ∼0.5 mm) (Lafond et al. 2004) although motion capture was not available as part of this dataset. Fourier transform of the difference between COP and COM showed an amplitude spectrum A(ω) consistent with a damped oscillator, which was fit to the following function using a least-squares optimization routine

| (1) |

where C is a scaling constant, I is the moment of inertia about the ankle (Ledebt and Breniere 1994), Ke is stiffness, B is damping, and ω is the angular frequency (radian/s or 1/2π Hz).

In a simplified case without damping, the model predicts a power-law relationship (COMRMS ∝ Ke−0.5) between COMRMS and Ke (Winter et al. 1998). In both the damped and undamped models, the decreased postural stiffness will increase postural sway amplitude.

Model fit was generally good (AP: R2 = 0.75 ± 0.04, ML: R2 = 0.76 ± 0.05; mean ± SD, R2 = variance accounted for). Trials with poor fits (R2 < 0.6) were discarded (<0.25% of trials) for quality control. RMS amplitude of the center of mass sway (COMRMS) and of the center of pressure (COPRMS) was also determined. These variables were calculated using MATLAB 7.4 (Mathworks, Natick MA).

Clinical measures of physiologic function

We considered multiple clinical characteristics that may be related to balance or dual-task ability, including age, gender, vision, peripheral neuropathy in the feet, leg strength, fall history, and gait speed. Vision was determined using a Snellen chart. Peripheral neuropathy was defined as inability to sense either of two Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments (4.1 and 5.6 g) less than three times of four in either foot. Leg strength was assessed using maximum single repetition weight on leg press scaled to body weight. Fall history was defined as a self-report of any fall within 1 yr prior to data collection. We also quantified executive function (Yogev-Seligmann et al. 2008), the ability to plan, coordinate, and modulate behavior, using the Trail Making Test Part B (TMT-B) (Reitan and Wolfson 1993), a timed test of connecting the dots on a page in the 1-A-2-B-. sequence, and cognitive status using the Folstein mini-mental status examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al. 1975), a dementia screening instrument that assesses situational awareness, verbal memory, and arithmetic skills. Education (self-report of completing high school or higher education) and depression using the Center for Epidemiological Studies depression scale, Hopkins revision (CES-d-R) (Eaton et al. 2004) were also assessed.

Statistical analyses

First we determined the effect of dual task on dependent variables of sway amplitudes COPRMS, COMRMS, stiffness Ke, and damping B. A mixed-model ANOVA was used (SAS 9.1, Cary NC, proc mixed), with empirical (“sandwich”) standard error estimation (Zeger and Liang 1986) and unstructured covariance to account for multiple observations per condition and per subject. AP and ML data were analyzed separately.

To account for any differences in the ability to perform serial subtractions among participants, we further divided the population into those who could complete the serial subtraction S3 task (“S3-able” group) and who could not (“S3-unable” group), and tested if the two groups differed in their postural control parameters by adding a between-subjects term to the mixed-model ANOVA in the preceding text.

To account for the demographic, clinical, and body-size differences between the groups, the mixed model ANOVA were repeated with the biomechanically scaled variables (Hof 1996) and with the clinical characteristics as covariates in the mixed-model ANOVA. COPRMS, COMRMS, Ke, and B were scaled to (COPRMS/h), (COMRMS/h), (Ke/mgh), and (B/mgh), respectively, where m is body mass, h is height and g is 9.81 m/s2. These variables were log-transformed to attain a normal distribution. Covariates included age, gender, education, gait speed, CES-D-R, sensory loss, TMT-B, daily alcohol use, and fall history (Table 1).

Second, we also tested the inverted pendulum model's prediction on the power law relationship (COMRMS ∝ Ke−0.5) between center of mass sway and postural stiffness. We tested their relationship using a linear regression for a log-log slope of −0.5. Further, we determined whether the effect of dual task on COMRMS can be explained through changes in Ke by including Ke as a covariate when assessing the effect of the dual task on COMRMS in a mixed model analysis. Because both COMRMS and Ke were log-transformed, this also tests for a linear relationship in the log-log space.

RESULTS

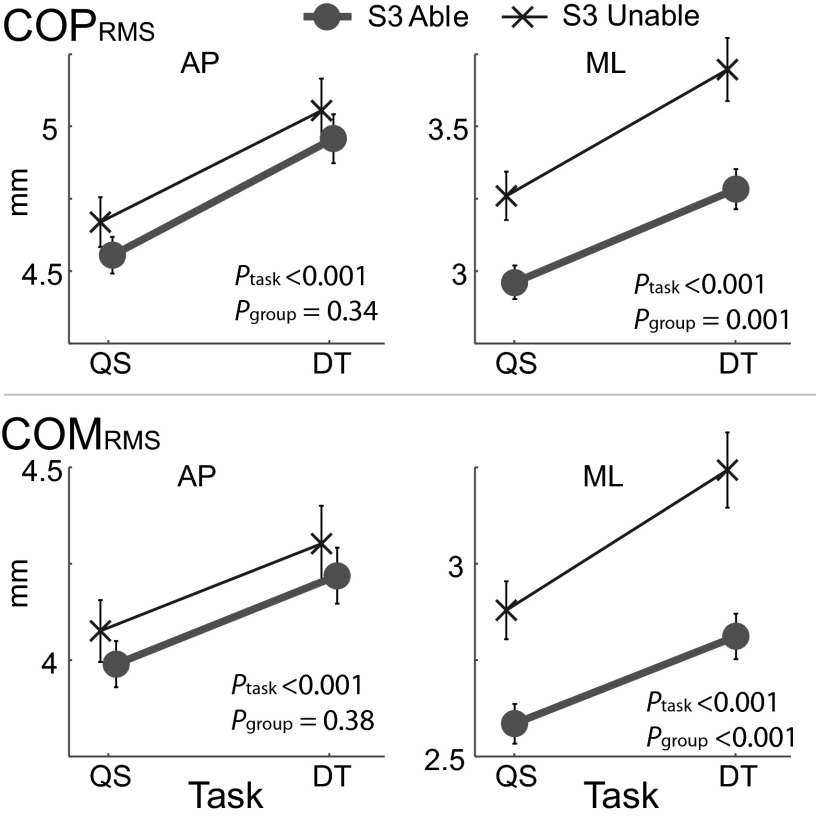

The MBS cohort includes relatively healthy community-dwelling older adults (Leveille et al. 2008) (Table 1). Sway amplitudes COPRMS and COMRMS increased with dual task (DT; P < 0.001) in both AP and ML directions. Stiffness Ke decreased (P < 0.001) in the ML direction during dual task but not in the AP (P = 0.32; Table 2). These results suggest that in AP, the increase in sway amplitude due to dual task come from something other than the decrease in Ke. In the ML direction, the increase in sway amplitude comes through the decrease in Ke. Damping B increased with dual task (P < 0.001) in both AP and ML directions.

Table 2.

Effect of dual task on inverted pendulum model parameters

| Quiet Stance | Dual Task | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP | |||

| COPRMS, mm | 4.65 ± 1.75 | 5.03 ± 2.17 | <0.001 |

| COMRMS, mm | 4.08 ± 1.70 | 4.29 ± 1.93 | <0.001 |

| Ke, N-m/rad | 876.5 ± 654.0 | 885.3 ± 683.3 | 0.32 |

| B, N-m-s/rad | 228.3 ± 101.9 | 242.8 ± 117.2 | <0.001 |

| ML | |||

| COPrms | 3.17 ± 1.57 | 3.57 ± 2.06 | <0.001 |

| COMrms | 2.82 ± 1.71 | 3.11 ± 1.98 | <0.001 |

| Ke | 712.4 ± 489.1 | 624.8 ± 460.0 | <0.001 |

| B | 164.3 ± 73.9 | 182.3 ± 89.6 | <0.001 |

COPRMS; RMS amplitude of center of pressure (COP) excursions; COMRMS: RMS amplitude of center of mass (COM) excursions; Ke, observed mechanical stiffness; B, observed mechanical damping; AP, anteroposterior sway; ML, mediolateral sway.

Group differences by dual tasking ability

Compared with the S3-able group, the S3-unable group was older, less educated, had poorer cognitive function, and more depression and included more women and those with a history of falls (Table 1). In addition, they were also shorter and had less leg strength. The magnitude of the stiffness parameter Ke was similar to previous reports (Webber et al. 2004; Winter et al. 1998). However, damping B was lower than previously reported values from young adults (Winter et al. 1998). In the AP direction, no group differences were observed in any of the biomechanical model parameters (P > 0.12; Table 3, Figs. 3 and 4). Yet in the ML direction, S3-unable group exhibited greater postural sway amplitude (COPRMS and COMRMS; P < 0.001), less stiffness Ke (P < 0.001), and less damping B (P = 0.005) than the S3-able group (Figs. 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Effect of dual task and group on mediolateral postural model parameters with adjustments

|

P |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Un-adjusteda | Body-size scaledb | Body-size + Covariate adjustedc | |

| COPRMS | Task | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| S3 group | 0.001 | <0.001d | 0.260e | |

| interaction | 0.250 | 0.535 | 0.730 | |

| COMRMS | Task | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| S3 group | <0.001 | <0.001d | 0.160e | |

| interaction | 0.120 | 0.454 | 0.620 | |

| Ke | Task | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| S3 group | 0.001 | 0.005d | 0.940e | |

| interaction | 0.090 | 0.022 | 0.190 | |

| B | Task | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| S3 group | 0.001 | 0.154d | 0.588e | |

| interaction | 0.368 | 0.122 | 0.070 | |

Only mediolateral (ML) results are shown, as no group differences were found in anteroposterior (AP) direction.

Mixed-model ANOVA with postural model parameters scaled to body size, according to Hof (1996) to account for differences in body size between subtraction-by-3 (S3) groups.

Covariate-adjusted mixed-model ANOVA with scaled postural model parameters: adjusted by age, gender, education, gait speed, CES-D-R, sensory loss, TMT-B, daily alcohol use, and fall history.

Group differences remained significant after scaling by body size, except for damping B.

Group differences were explained by the covariates.

Fig. 3.

Postural sway amplitudes between subtraction-by-3 (S3) groups and tasks. Postural sway (COPRMS and COMRMS) increased when performing the dual task. In anteroposterior (AP), no group differences were found between the S3 groups, but in mediolateral (ML), those with difficulty performing S3 task exhibited greater sway amplitude.

Fig. 4.

Dual task and pendulum model parameters Group differences were not significant in the AP direction. In ML, those with difficulty performing the S3 task exhibited lower stiffness and damping. Damping increased with dual task. Ke increased only in the S3-unable group in AP and decreased only in ML direction with dual task. Lines are offset for clarity.

Effect of dual task in S3 groups

After accounting for group differences in the ability to perform the dual task, the effect of dual task on the postural parameters were similar (Figs. 3 and 4). However, AP Ke exhibited an interaction between group and task (P = 0.004), where only the S3-unable group exhibited an increase in Ke (least-squares differences post hoc P = 0.004).

After scaling to body size and adjusting for clinical covariates, group differences were no longer significant (P = 0.15∼0.94; Table 3) in all variables. However, the effect of dual task remained significant (P < 0.002) after these adjustments. The interaction of group and task on AP Ke also remained significant (P = 0.048).

Predicted power-law relationship

The simplified undamped model predicts a log-log slope of −0.5 in the regression between COMRMS and Ke. In our population, COMRMS and Ke did show an inverse relationship, but the association was not as strong as predicted, with an attenuated regression slope closer to zero. Log-log slopes in the S3-unable group (AP: −0.11, ML −0.23) were less attenuated than in the S3-able group (AP: −0.086; ML −0.16). Using a random-intercepts regression model to account for individual differences did not affect the result. Including other covariates in this regression model also did not account for the attenuated slopes. Thus our data did not support this prediction from the undamped case, contrary to previous work (Winter et al. 1998).

Mediating role of Ke in sway amplitude

Because Ke decreased with dual task in the ML direction, we tested whether this decrease in Ke could explain the increase in sway amplitude due to the dual task. When Ke was included as a covariate in addition to those in the preceding text in the mixed model analysis, both Ke and dual task effects were statistically significant (both P < 0.001) in explaining changes in sway (Table 4). Thus changes in Ke did not fully explain the increase in sway amplitude. Furthermore, in AP, Ke did not decrease during dual task, and in fact increased in the S3-unable group. Therefore there must be other mechanisms that contribute to changes in postural sway during dual task.

Table 4.

Multivariate associations of ML COMRMS with experimental conditions and clinical covariates

| Effect | P |

|---|---|

| Task | <0.001 |

| S3 group | 0.15 |

| Task * Group | 0.47 |

| Ke | <0.001 |

Multivariate associations were determined using the mixed-model ANOVA. Covariates include: age, gender, education, gait speed, CES-D-R, sensory loss, TMT-B, daily alcohol use, and fall history. Ke was considered as a covariate only in the ML direction because Ke was not affected by the dual task in AP direction. Dual task-related changes in Ke did not fully explain the changes in COMRMS with dual task. Thus the biomechanical model does not fully explain the increase in postural sway amplitude due to dual task.

DISCUSSION

In this representative population-based sample of older adults, we found that dual task led to increased postural sway with the decrease of postural stiffness in the ML direction but not in the AP direction. Those with difficulty performing the serial subtractions dual task increased postural stiffness in the AP direction with the dual task. We also found S3 task ability is related to only ML postural dynamics. In our population, the increase in postural sway with dual task could be explained only partly through the changes in postural stiffness. Further, damping played an important role in postural control. This was evidenced by how damping was affected by both dual task and the S3 task ability. Also, the power-law relationship between sway amplitude and postural stiffness as predicted by the undamped model was not supported in our population.

Difference between AP and ML postural control

The results demonstrate the different involvement of cognitive resources on control of AP versus ML postural sway. Only in the ML direction, the S3-unable group has greater postural sway and less postural stiffness even after accounting for body size differences. This suggests that difficulty with performing the dual task is accompanied by changes in postural dynamics only in the ML direction. Also in AP, the increase in sway amplitude with dual task was not accompanied by a decrease in Ke. Yet in ML, increased sway with dual task was accompanied by a concurrent decrease in Ke. Thus the response of the postural system to the dual task stressor is different between AP and ML. Interestingly, in the S3-unable group, despite the increase in AP Ke, sway amplitude still increased, when the model predicts that increased postural stiffness should reduce sway amplitude. Also this indicates that the S3-unable group exhibits an altered postural control in response to the dual task. These differences in postural control mechanism could be detected using this simple model of postural control.

One possible mechanism for this difference between AP and ML postural control may be the nature of bipedal standing as it may afford additional natural stability in the ML direction due to the wider base of support but not in AP. During dual task, the CNS may be trying to maintain standing posture using the reduced attentional or neural resources that can be devoted to postural control. The CNS may be able to afford to not activate muscles that control ML motion, while it has to focus on AP postural control, which does not have the additional “free” postural stability. This prioritization may also explain why only ML dynamics are affected by the S3-task impairments. Yet if ML postural control is affected severely enough, a fall may ensue. Thus dual task may divert the resources necessary to maintain ML stability and thus lead to falls. That mediolateral postural, stepping, and gait dynamics are associated with falls (Hilliard et al. 2008; Kuo 1999; Maki et al. 1994; Melzer et al. 2004; Rogers and Mille 2003) supports this idea. Further, wider stance leads to increased mediolateral stiffness (Winter et al. 1998). However, more work is needed to confirm whether the observed differences in AP and ML postural control mechanisms are in fact in response to differences in wider base of support. This possibility could be tested in experiments using a single-leg stance or tandem stance (1 foot directly in front of the other). During single-leg stance, the performance of the dual task may affect postural control similarly in both AP and ML, whereas during tandem stance, the effects of dual tasking may switch from our observed results. Other postural challenges such as eyes-closed or standing on foam may amplify these effects. EMG data are needed to confirm these changes in muscle activation.

Those with difficulty performing serial subtractions increased postural stiffness as noted by the interaction of task and group on AP Ke. The increased stiffness may be an attempt to improve postural stability by co-contracting leg muscles (Melzer et al. 2001). However, this increased stiffness should have decreased sway amplitude as previously reported (Melzer et al. 2001) but instead was accompanied by an increase in sway amplitude. This suggests that a specific deficit exists in postural control of those with difficulty performing serial subtractions, where during the dual task impaired overall postural control as indicated by the sway amplitude plus increased muscular co-contraction. The increased co-contractions could slow and hamper the ability to generate the corrective reactions to environmental perturbations such as slips and trips, thus leading to falls.

Dual task also increased postural damping, but its physiological basis and clinical significance still remain to be explored. Postural damping may not only reflect passive tissue properties, but active reflexive control of posture as well (Fitzpatrick and Gandevia 2005; Loram et al. 2004, 2009; Morasso and Schieppati 1999). Greater damping would help absorb and withstand perturbations that could result in a fall. That older adults have less damping than young adults (Winter et al. 1998) especially in those with S3 task difficulties support this idea.

Validation and limitations of the damped oscillator inverted pendulum model

Even after scaling out the heterogeneity in the data due to body size, our data did not behave strictly like the power law relationship predicted by the simplified undamped model (COMRMS ∝ Ke), with a log-log slope of −0.5. This, combined with the increases in damping during dual task, indicates that damping is an important factor in postural sway behavior (Cenciarini et al. 2009, 2010; Maurer and Peterka 2005; Peterka 2000).

The increase in sway due to the dual task could only be partially explained by the concurrent changes in Ke in ML and not at all in AP direction, suggesting that there are other effects of dual task on postural sway amplitude that is not captured by this model. This may be because according to the damped oscillator model, sway amplitude is a nonlinear function of stiffness, damping and driving forces. Therefore it is reasonable to expect the Ke does not fully explain the variance in the sway amplitude. The change in damping is not a likely explanation, as increased damping would have the effect of slowing down the sway and likely lead to smaller sway amplitude, not greater. One explanation could be formulated in terms of a forcing function on the damped oscillator, which will be explored in future work. Also, this model does not explicitly account for cognitive and neural aspects as well as other mechanical aspects of postural control.

The inability to fully describe this role of cognitive distractions on postural control is a limitation of the simple mechanical lumped parameter model. This model in its current form does not separate the role of active versus passive control of posture, as suggested in the literature (Fitzpatrick and Gandevia 2005; Loram et al. 2004, 2009; Morasso and Schieppati 1999). It is not clear how much of postural stiffness is due to passive tissue properties, which could be modified using strength training and mechanical supports, versus active control, which could be modified using cognitive and sensory integration training, as these would be two different domains that counted be targeted for interventions to reduce falls in older adults. A more sophisticated model of postural control that separates the passive elements from the dynamics of sensory input, neural controller, and motor output may better explain the role of cognitive function and separate the contributions of active versus passive mechanisms and also the controller (nervous system) versus actuator (muscles) (Cenciarini et al. 2009, 2010; Mahboobin et al. 2007; Maurer and Peterka 2005; Peterka 2000). Also because older adults tend to use a hip strategy for postural control compared with using the ankle as with young adults (Horak and Nashner 1986), a multi-link system that includes the knee and the hip may better model quiet standing in older adults. However, such models would require data from perturbation-response experiments with full-body motion capture, which are difficult to obtain from large population-based epidemiological studies. Nevertheless mechanistic differences in postural sway behavior due to performing the dual task and the ability to perform them were captured using this simple model. Our results suggest that dual task compromises ML postural control in terms of increased sway amplitude and decreased stiffness and damping particularly in those with difficulty performing the S3 task, which may lead to falls. It provides mechanical explanations for the fact that ML postural, stepping, and gait dynamics explain fall risk (Bauby and Kuo 2000; Cenciarini et al. 2009, 2010; Hilliard et al. 2008; Maki et al. 1994; Melzer et al. 2004; Rogers and Mille 2003). Simple models, despite their limitations, can greatly add to the understanding of the physiology. Understanding a simple model of any physiological system is important before using these more complex models.

Heterogeneity of postural sway response to dual task in the literature

In our population based sample of community dwelling older adults, we found that the sway increases with dual task. Other small studies have found a decrease in sway with dual task (Prado et al. 2007). In one study, older adults reduced postural sway in response to performing a dual task when standing in narrow stance, by activating ankle muscles (Melzer et al. 2001). Inconsistent reports in the literature on the effect of dual task may be due to the different cognitive tasks (Prado et al. 2007; Sturnieks et al. 2008) or standing configuration (Melzer et al. 2001). We used a serial subtraction task, but the use of visual search (Prado et al. 2007) or sensory integration (Mahboobin et al. 2007) tasks may affect Ke differently as they may use different brain functions and influence motor functions. The reduction in sway and increase in EMG activity with dual task during narrow-base standing (Melzer et al. 2001) could be explained by Winter's inverted pendulum model. During narrow-base standing, Ke is decreased (Winter et al. 1998) and thus increased muscle activation may be necessary to compensate.

Task prioritization may also contribute to inconsistent findings (Bateni et al. 2004; Siu et al. 2008). Healthy individuals may prioritize the dual task and be able to accommodate resulting increases in sway magnitude. Unhealthy people may have to prioritize standing, leading to minimal changes in sway magnitude yet more mistakes on the dual task. It is possible that the relationship between S3 task performance and postural dynamics may be confounded by differences in task prioritization between the two groups. However, except for AP Ke, both groups responded similarly to the dual task, and therefore the difference in task prioritization is unlikely.

Limitations and future work

Although postural stiffness may be reflective of postural muscle tone and motor control function of the brain, we cannot directly infer any actual muscle activation or CNS deficits, as EMG and MRI data were not collected during this wave of the MOBILIZE Boston parent study. Future work will need to use muscle and brain activation dynamics in conjunction with posturography data to better understand the postural control mechanisms. Our population consisted of relatively healthy community-dwelling older adults, and therefore our findings need to be confirmed in a more frail population. Also the estimates of Ke are several steps removed from raw data after being fit to a model and thus may be more error-prone. This limitation of using noisy measures is mitigated by the use of large number of participants and trials.

In this population sample, the people with dual task difficulty also have other various physical impairments. Thus the differences in postural control between S3 groups may be caused by impairments other than the frontal lobes, as group differences could be explained by the covariates. However, the interaction between dual task and group remained significant even after accounting for other clinical measures of health, suggesting that our cognitive stress on the brain (Hayashi et al. 2000; Kazui et al. 2000) does affect postural control differently between the S3 groups.

This work, in our knowledge, is the first to quantify postural dynamics with dual task in a large cohort of representative population sample of community-dwelling older adults. Previous smaller studies have produced conflicting due to heterogeneities in methodology results (Melzer et al. 2001; Prado et al. 2007; Sturnieks et al. 2008). With this study, we can conclude that serial subtractions do increase sway amplitude in community-dwelling older adults. This work is also the first to describe the differential effects of dual task on AP and ML sway dynamics, thus providing mechanical explanations for the relationship between fall risk and ML postural and gait control (Hilliard et al. 2008; Kuo 1999; Maki et al. 1994; Melzer et al. 2004; Rogers and Mille 2003). This is also the first time a theoretical model of postural control has been tested against a large representative population sample of older adults.

In summary, the increase in postural sway due to performing a dual task in older adults occurred through a decrease of postural stiffness in ML but not in AP direction. Also, those with difficulty performing the dual task exhibited larger sway amplitudes and lower stiffness and damping, only in the ML direction. Performance of a serial subtraction task increased postural stiffness only in the AP direction in this group. In future work, separating the active versus passive postural stiffness in the postural system would better elucidate the role of cognitive/neural control of postural system and identify other factors that may lead to the increase in postural sway besides stiffness. The difference between AP and ML postural control requires further examination. An integrated two-dimensional model of postural control of both AP and ML movements may better explain these findings. The decrease in stiffness due to dual task in those with low stiffness may further exacerbate balance problems and increase fall risk. Further work is needed to see if postural stiffness and dual-task related changes are associated with future fall risk in older adults. (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2)

Fig. 1.

Inverted pendulum model diagram of the damped oscillator inverted pendulum model of posture described by Winter et al. The center of mass (COM) dynamics are influenced by stiffness Ke and damping B. COM motion is described by its root-mean square (RMS) amplitude or COMRMS.

Fig. 2.

Calculation of inverted pendulum parameters from data. A: measured center of pressure (COP) signal from force plate. B: movements of the COM is estimated by double-integrating horizontal forces along with COM. C: the difference between COP and COM. D: Fourier transform of the COP-COM signal. The damped oscillator model is fit to the amplitude spectrum using least-squares optimization.

GRANTS

This work was funded by Naitonal Institute on Aging Grants P01AG-004390 and T32AG-023480.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the MOBILIZE Boston research team and study participants for their time, effort, and dedication. We thank J. Hausdorff for help with the experimental design and review of the manuscript, B. Manor and E. Hsiao-Wecksler for helpful comments, and L. A. Cupples for help with the mixed model design.

REFERENCES

- Bateni et al., 2004. Bateni H, Zecevic A, McIlroy WE, Maki BE. Resolving conflicts in task demands during balance recovery: does holding an object inhibit compensatory grasping? Exp Brain Res 157: 49–58, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauby and Kuo, 2000. Bauby CE, Kuo AD. Active control of lateral balance in human walking. J Biomech 33: 1433–1440, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown et al., 1999. Brown LA, Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott MH. Attentional demands and postural recovery: the effects of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54: M165–M171, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenciarini et al., 2009. Cenciarini M, Loughlin PJ, Sparto PJ, Redfern MS. Medial-lateral postural control in older adults exhibits increased stiffness and damping. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2009: 7006–7009, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenciarini et al., 2010. Cenciarini M, Loughlin PJ, Sparto PJ, Redfern MS. Stiffness and damping in postural control increase with age. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 57: 267–275, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker et al., 2007. Donker SF, Roerdink M, Greven AJ, Beek PJ. Regularity of center-of-pressure trajectories depends on the amount of attention invested in postural control. Exp Brain Res 181: 1–11, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton et al., 2004. Eaton WW, Muntaner C, Smith C, Tien A, Ybarra M. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD–R). In: The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment, edited by Maruish ME. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2004, p. 363–377 [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick and Gandevia, 2005. Fitzpatrick RC, Gandevia SC. Paradoxical muscle contractions and the neural control of movement and balance. J Physiol 564: 2, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein et al., 1975. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: 189–198, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, 2000. Fuller GF. Falls in the elderly. Am Fam Physician 61: 2173–2174, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi et al., 2000. Hayashi N, Ishii K, Kitagaki H, Kazui H. Regional differences in cerebral blood flow during recitation of the multiplication table and actual calculation: a positron emission tomography study. J Neurol Sci 176: 102–108, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herath et al., 2001. Herath P, Klingberg T, Young J, Amunts K, Roland P. Neural correlates of dual task interference can be dissociated from those of divided attention: an fMRI study. Cereb Cortex 11: 796–805, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard et al., 2008. Hilliard MJ, Martinez KM, Janssen I, Edwards B, Mille ML, Zhang Y, Rogers MW. Lateral balance factors predict future falls in community-living older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89: 1708–1713, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof, 1996. Hof AL. Scaling gait data to body size. Gait Posture 4: 222–223, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Horak and Nashner, 1986. Horak FB, Nashner LM. Central programming of postural movements: adaptation to altered support-surface configurations. J Neurophysiol 55: 1369–1381, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang et al., 2009. Kang HG, Costa MD, Priplata AA, Starobinets OV, Goldberger AL, Peng CK, Kiely DK, Cupples LA, Lipsitz LA. Frailty and the degradation of complex balance dynamics during a dual-task protocol. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64: 1304–1311, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazui et al., 2000. Kazui H, Kitagaki H, Mori E. Cortical activation during retrieval of arithmetical facts and actual calculation: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 54: 479–485, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, 1999. Kuo AD. Stabilization of lateral motion in passive dynamic walking. Intl J Robot Res 18: 917–930, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Lafond et al., 2004. Lafond D, Duarte M, Prince F. Comparison of three methods to estimate the center of mass during balance assessment. J Biomech 37: 1421–1426, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledebt and Breniere, 1994. Ledebt A, Breniere Y. Dynamical implication of anatomical and mechanical parameters in gait initiation process in children. Hum Mov Sci 13: 801–815, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Leveille et al., 2008. Leveille SG, Kiel DP, Jones RN, Roman A, Hannan MT, Sorond FA, Kang HG, Samelson EJ, Gagnon M, Freeman M, Lipsitz LA. The MOBILIZE Boston Study: design and methods of a prospective cohort study of novel risk factors for falls in an older population. BMC Geriatr 8: 16, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loram et al., 2004. Loram ID, Maganaris CN, Lakie M. Paradoxical muscle movement in human standing. J Physiol 556: 683–689, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loram et al., 2009. Loram ID, Maganaris CN, Lakie M. Paradoxical muscle movement during postural control. Med Sci Sports Exerc 41: 198–204, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahboobin et al., 2007. Mahboobin A, Loughlin PJ, Redfern MS. A model-based approach to attention and sensory integration in postural control of older adults. Neurosci Lett 429: 147–151, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki et al., 1994. Maki BE, Holliday PJ, Topper AK. A prospective study of postural balance and risk of falling in an ambulatory and independent elderly population. J Gerontol 49: M72–M84, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer and Peterka, 2005. Maurer C, Peterka RJ. A new interpretation of spontaneous sway measures based on a simple model of human postural control. J Neurophysiol 93: 189–200, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer et al., 2001. Melzer I, Benjuya N, Kaplanski J. Age-related changes of postural control: effect of cognitive tasks. Gerontology 47: 189–194, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer et al., 2004. Melzer I, Benjuya N, Kaplanski J. Postural stability in the elderly: a comparison between fallers and non-fallers. Age Ageing 33: 602–607, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasso and Schieppati, 1999. Morasso PG, Schieppati M. Can muscle stiffness alone stabilize upright standing? J Neurophysiol 82: 1622–1626, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterka, 2000. Peterka RJ. Postural control model interpretation of stabilogram diffusion analysis. Biol Cybern 82: 308–318, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado et al., 2007. Prado JM, Stoffregen TA, Duarte M. Postural sway during dual tasks in young and elderly adults. Gerontology 53: 274–281, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan and Wolfson, 1993. Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. Tuscon, AZ: Neuropsychology Press, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Rogers and Mille, 2003. Rogers MW, Mille M-L. Lateral stability and falls in older people. Exercise Sport Sci Rev 31: 182–187, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu et al., 2008. Siu KC, Catena RD, Chou LS, van Donkelaar P, Woollacott MH. Effects of a secondary task on obstacle avoidance in healthy young adults. Exp Brain Res 184: 115–120, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling et al., 2001. Sterling DA, O'Connor JA, Bonadies J. Geriatric falls: injury severity is high and disproportionate to mechanism. J Trauma 50: 116–119, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturnieks et al., 2008. Sturnieks DL, St, George R, Fitzpatrick RC, Lord SR. Effects of spatial and nonspatial memory tasks on choice stepping reaction time in older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 63: 1063–1068, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber et al., 2004. Webber A, Virji-Babul N, Edwards R, Lesperance M. Stiffness and postural stability in adults with Down syndrome. Exp Brain Res 155: 450–458, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter et al., 1998. Winter DA, Patla AE, Prince F, Ishac M, Gielo-Perczak K. Stiffness control of balance in quiet standing. J Neurophysiol 80: 1211–1221, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woollacott and Shumway-Cook, 2002. Woollacott M, Shumway-Cook A. Attention and the control of posture and gait: a review of an emerging area of research. Gait Posture 16: 1–14 1211–1221, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogev-Seligmann et al., 2008. Yogev-Seligmann G, Hausdorff JM, Giladi N. The role of executive function and attention in gait. Mov Disord 23: 329–342; quiz 472, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatsiorsky and King, 1997. Zatsiorsky VM, King DL. An algorithm for determining gravity line location from posturographic recordings. J Biomech 31: 161–164, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger and Liang, 1986. Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 42: 121–130, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]