Abstract

Fluorescent calcium indicators are becoming increasingly popular as a means for observing the spiking activity of large neuronal populations. Unfortunately, extracting the spike train of each neuron from a raw fluorescence movie is a nontrivial problem. This work presents a fast nonnegative deconvolution filter to infer the approximately most likely spike train of each neuron, given the fluorescence observations. This algorithm outperforms optimal linear deconvolution (Wiener filtering) on both simulated and biological data. The performance gains come from restricting the inferred spike trains to be positive (using an interior-point method), unlike the Wiener filter. The algorithm runs in linear time, and is fast enough that even when simultaneously imaging >100 neurons, inference can be performed on the set of all observed traces faster than real time. Performing optimal spatial filtering on the images further refines the inferred spike train estimates. Importantly, all the parameters required to perform the inference can be estimated using only the fluorescence data, obviating the need to perform joint electrophysiological and imaging calibration experiments.

INTRODUCTION

Simultaneously imaging large populations of neurons using calcium sensors is becoming increasingly popular (Yuste and Katz 1991; Yuste and Konnerth 2005), both in vitro (Ikegaya et al. 2004; Smetters et al. 1999) and in vivo (Göbel and Helmchen 2007; Luo et al. 2008; Nagayama et al. 2007), and will likely continue to improve as the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of genetic sensors continues to improve (Garaschuk et al. 2007; Mank et al. 2008; Wallace et al. 2008). Whereas the data from these experiments are movies of time-varying fluorescence intensities, the desired signal consists of spike trains of the observable neurons. Unfortunately, finding the most likely spike train is a challenging computational task, due to limitations on the SNR and temporal resolution, unknown parameters, and analytical intractability.

A number of groups have therefore proposed algorithms to infer spike trains from calcium fluorescence data using very different approaches. Early approaches simply thresholded dF/F [typically defined as (F − Fb)/Fb, where Fb is baseline fluorescence; e.g., Mao et al. 2001; Schwartz et al. 1998] to obtain “event onset times.” More recently, Greenberg et al. (2008) developed a dynamic programming algorithm to identify individual spikes. Holekamp et al. (2008) then applied an optimal linear deconvolution (i.e., the Wiener filter) to the fluorescence data. This approach is natural from a signal processing standpoint, but does not realize the knowledge that spikes are always positive. Sasaki et al. (2008) proposed using machine learning techniques to build a nonlinear supervised classifier, requiring many hundreds of examples of joint electrophysiological and imaging data to “train” the algorithm to learn what effect spikes have on fluorescence. Vogelstein and colleagues (2009) proposed a biophysical model-based sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) method to efficiently estimate the probability of a spike in each image frame, given the entire fluorescence time series. Although effective, that approach is not suitable for on-line analyses of populations of neurons because the computations run in about real time per neuron (i.e., analyzing 1 min of data requires about 1 min of computational time on a standard laptop computer).

In the present work, a simple model is proposed relating spiking activity to fluorescence traces. Unfortunately, inferring the most likely spike train, given this model, is computationally intractable. Making some reasonable approximations leads to an algorithm that infers the approximately most likely spike train, given the fluorescence data. This algorithm has a few particularly noteworthy features, relative to other approaches. First, spikes are assumed to be positive. This assumption often improves filtering results when the underlying signal has this property (Cunningham et al. 2008; Huys et al. 2006; Lee and Seung 1999; Lin et al. 2004; Markham and Conchello 1999; O'Grady and Pearlmutter 2006; Paninski et al. 2009; Portugal et al. 1994). Second, the algorithm is fast: it can process a calcium trace from 50,000 images in about 1 s on a standard laptop computer. In fact, filtering the signals for an entire population of >100 neurons runs faster than real time. This speed facilitates using this filter on-line, as observations are being collected. In addition to these two features, the model may be generalized in a number of ways, including incorporating spatial filtering of the raw movie, which can improve effective SNR. The utility of the proposed filter is demonstrated on several biological data sets, suggesting that this algorithm is a powerful and robust tool for on-line spike train inference. The code (which is a simple Matlab script) is available for free download from http://www.optophysiology.org.

METHODS

Data-driven generative model

Figure 1 shows data from a typical in vitro epifluorescence experiment (for data collection details see Experimental methods later in this section). The top panel shows the mean frame of this movie, including four neurons, three of which are patched. To build the model, the pixels within a region of interest (ROI) are selected (white circle). Given the ROI, all the pixel intensities of each frame can be averaged, to get a one-dimensional fluorescence time series, as shown in the bottom left panel (black line). By patching onto this neuron, the spike train can also be directly observed (black bars; bottom left). Previous work suggests that this fluorescence signal might be well characterized by convolving the spike train with an exponential and adding noise (Yuste and Konnerth 2005). This model is confirmed by convolving the true spike train with an exponential (gray line; bottom left) and then looking at the distribution of the residuals. The bottom right panel shows a histogram of the residuals (dashed line) and the best-fit Gaussian distribution (solid line).

Fig. 1.

Typical in vitro data suggest that a reasonable first-order model may be constructed by convolving the spike train with an exponential and adding Gaussian noise. Top panel: the average (over frames) of a field of view. Bottom left: true spike train recorded via a patch electrode (black bars), convolved with an exponential (gray line), superimposed on the Oregon Green BAPTA 1 (OGB-1) fluorescence trace (black line). Whereas the spike train and fluorescence trace are measured data, the calcium is not directly measured, but rather, inferred. Bottom right: a histogram of the residual error between the gray and black lines from the bottom left panel (dashed line) and the best-fit Gaussian (solid line). Note that the Gaussian model provides a good fit for the residuals here.

The preceding observations may be formalized as follows. Assume there is a one-dimensional fluorescence trace F from a neuron [throughout this text X indicates the vector (X1, … , XT), where T is the index of the final frame]. At time t, the fluorescence measurement Ft is a linear-Gaussian function of the intracellular calcium concentration at that time [Ca2+]t:

The parameter α absorbs all experimental variables influencing the scale of the signal, including the number of sensors within the cell, photons per calcium ion, amplification of the imaging system, and so on. Similarly, the offset β absorbs, for example, the baseline calcium concentration of the cell, background fluorescence of the fluorophore, and imaging system offset. The noise at each time εt is independently and identically distributed according to a normal distribution with zero mean and σ2 variance, as indicated by the notation

(0, 1). This noise results from calcium fluctuations independent of spiking activity, fluorescence fluctuations independent of calcium, and other sources of imaging noise.

(0, 1). This noise results from calcium fluctuations independent of spiking activity, fluorescence fluctuations independent of calcium, and other sources of imaging noise.

Then, assuming that the intracellular calcium concentration [Ca2+]t jumps by A μM after each spike and subsequently decays back down to baseline Cb μM, with time constant τ s, one can write:

| (2) |

where Δ is the time step size—which is the frame duration, or 1/(frame rate)—and nt indicates the number of times the neuron spiked in frame t. Note that because [Ca2+]t and Ft are linearly related to one another, the fluorescence scale α and calcium scale A are not identifiable. In other words, either can be set to unity without loss of generality because the other can absorb the scale entirely. Similarly, the fluorescence offset β and calcium baseline Cb are not identifiable, so either can be set to zero without loss of generality. Finally, letting γ = (1 − Δ/τ), Eq. 2 can be rewritten by replacing [Ca2+]t with its nondimensionalized counterpart Ct:

| (3) |

Note that Ct does not refer to absolute intracellular concentration of calcium, but rather, a relative measure (for a more general model see Vogelstein et al. 2009). The gray line in the bottom left panel of Fig. 1 corresponds to the putative C of the observed neuron.

To complete the “generative model” (i.e., a model from which simulations can be generated), the distribution from which spikes are sampled must be defined. Perhaps the simplest first-order description of spike trains is that at each time, spikes are sampled according to a Poisson distribution with some rate:

where λΔ is the expected firing rate per bin and Δ is included to ensure that the expected firing rate is independent of the frame rate. Thus Eqs. 1, 3, and 4 complete the generative model.

Goal

Given the above model, the goal is to find the maximum a posteriori (MAP) spike train, i.e., the most likely spike train n̂, given the fluorescence measurements, F:

| (5) |

where P[n|F] is the posterior probability of a spike train n, given the fluorescent trace F, and nt is constrained to be an integer ℕ0 = {0, 1, 2, … } because of the above assumed Poisson distribution. From Bayes' rule, the posterior can be rewritten:

| (6) |

where P[F] is the evidence of the data, P[F|n] is the likelihood of observing a particular fluorescence trace F, given the spike train n, and P[n] is the prior probability of a spike train. Plugging the far right-hand side of Eq. 6 into Eq. 5, yields:

| (7) |

where the second equality follows because P[F] merely scales the results, but does not change the relative quality of any particular spike train. Note that the prior P[n] acts as a regularizing term, potentially imposing sparseness or smoothness, depending on the assumed distribution (Seeger 2008; Wu et al. 2006). Both P[F|n] and P[n] are available from the preceding model:

| (8a) |

| (8b) |

where the first equality in Eq. 8a follows because C is deterministic given n, and the second equality follows from Eq. 1. Further, Eq. 8b follows from the Poisson process assumption, Eq. 4. Both P[Ft|Ct] and P[nt] can be written explicitly:

| (9a) |

| (9b) |

where both equations follow from the preceding model and the Poisson distribution acts as a sparse prior. Now, plugging Eq. 9 back into Eq. 8, and plugging that result into Eq. 7, yields:

| (10a) |

| (10b) |

where the second equality follows from taking the logarithm of the right-hand side and dropping terms that do not depend on n. Unfortunately, solving Eq. 10b exactly is analytically intractable because it requires a nonlinear search over an infinite number of possible spike trains. The search space could be restricted by imposing an upper bound k on the number of spikes within a frame. However, in that case, the computational complexity scales exponentially with the number of image frames—i.e., the number of computations required would scale with kT—which for pragmatic reasons is intractable.

Inferring the approximately most likely spike train, given a fluorescence trace

The goal here is to develop an algorithm to efficiently approximate n̂, the most likely spike train given the fluorescence trace. Because of the intractability described earlier, one can approximate Eq. 4 by replacing the Poisson distribution with an exponential distribution of the same mean (note that potentially more accurate approximations are possible, as described in the discussion). Modifying Eq. 10 to incorporate this approximation yields:

| (11a) |

| (11b) |

where the second equality follows from taking the log of the right-hand side (logarithm is a monotone function and therefore does not change the relative likelihood of particular spike trains) and dropping terms constant in nt. Note that the constraint on nt has been relaxed from nt ∈ ℕ0 to nt ≥ 0 (since the exponential distribution can yield any nonnegative number). The exponential prior, much like the Poisson prior, imposes a sparsening effect, by penalizing the objective function for large values of nt. Further, the exponential approximation makes the optimization problem concave in C, meaning that any gradient ascent method guarantees achieving the global maximum (because there are no local maxima, other than the single global maximum). To see that Eq. 11b is concave in C, rearrange Eq. 3 to obtain nt = Ct − γCt−1, so Eq. 11b can be rewritten:

| (12) |

which is a sum of terms that are concave in C, so the whole right-hand side is concave in C. Unfortunately, the integer constraint has been lost, i.e., the answer could include “partial” spikes. This disadvantage can be remedied by thresholding (i.e., setting nt = 1 for all nt greater than some threshold and the rest setting to zero) or by considering the magnitude of a partial spike at time t as a rough indication of the probability of a spike occurring during frame t. Note the relaxation of a difficult discrete optimization problem into an easier continuous problem is a common approximation technique in the machine learning literature (Boyd and Vandenberghe 2004; Paninski et al. 2009). In particular, the exponential distribution is a convenient nonnegative log-concave approximation of the Poisson (see the discussion for more details).

Although this convex relaxation makes the problem tractable, the “sharp” threshold imposed by the nonnegativity constraint prohibits the use of standard gradient ascent techniques. This may be rectified by using an “interior-point” method (Boyd and Vandenberghe 2004). Interior-point methods solve nondifferentiable problems indirectly by instead solving a series of differentiable subproblems that converge to the solution of the original nondifferentiable problem. In particular, each subproblem within the series drops the sharp threshold and adds a weighted barrier term that approaches −∞ as nt approaches zero. Iteratively reducing the weight of the barrier term guarantees convergence to the correct solution. Thus the goal is to efficiently solve:

| (13) |

where ln (·) is the “barrier term” and z is the weight of the barrier term (note that the constraint has been dropped). Iteratively solving for Ĉz for z going down to nearly zero guarantees convergence to Ĉ (Boyd and Vendenberghe 2004). The concavity of Eq. 13 facilitates using any number of techniques guaranteed to find the global maximum. Because the argument of Eq. 13 is twice analytically differentiable, one can use the Newton–Raphson technique (Press et al. 1992). The special tridiagonal structure of the Hessian enables each Newton–Raphson step to be very efficient (as described below). To proceed, Eq. 13 is first rewritten in more compact matrix notation. Note that:

| (14) |

where M ∈ ℝ(T−1)×T is a bidiagonal matrix. Then, letting 1 be a (T − 1)-dimensional column vector, β a T-dimensional column vector of β values, and λ = λΔ1 yields the objective function (Eq. 13) in more compact matrix notation (note that throughout we will use the subscript ⊙ to indicate element-wise operations):

| (15) |

where MC ≥⊙0 indicates an element-wise greater than or equal to zero, ln⊙(·) indicates an element-wise logarithm, and ‖x‖2 is the standard L2 norm, i.e., ‖x‖22 = Σi xi2. When using Newton–Raphson to ascend a surface, one iteratively computes both the gradient g (first derivative) and Hessian H (second derivative) of the argument to be maximized, with respect to the variables of interest (C here). Then, the estimate is updated using Cz ← Cz + sd, where s is the step size and d is the step direction obtained by solving Hd = g. The gradient and Hessian for this model, with respect to C, are given by:

| (16a) |

| (16b) |

where the exponents on the vector MC indicate element-wise operations. The step size s is found using “backtracking linesearches,” which finds the maximal s that increases the posterior and is between 0 and 1 (Press et al. 1992).

Standard implementations of the Newton–Raphson algorithm require inverting the Hessian, i.e., solving d = H−1g, a computation that scales cubically with T (requires on the order of T3 operations). Already, this would be a drastic improvement over the most efficient algorithm assuming Poisson spikes, which would require kT operations (where k is the maximum number of spikes per frame). Here, because M is bidiagonal, the Hessian is tridiagonal, so the solution may be found in about T operations, via standard banded Gaussian elimination techniques (which can be implemented efficiently in Matlab using H\g, assuming H is represented as a sparse matrix) (Paninski et al. 2009). In other words, the above approximation and inference algorithm reduces computations from exponential to linear time. appendix A contains pseudocode for this algorithm, including learning the parameters, as described in the next section. Note that once Ĉ is obtained, it is a simple linear transformation to obtain n̂, the approximate MAP spike train.

Learning the parameters

In practice, the model parameters θ = {α, β, σ, γ, λ} tend to be unknown. An algorithm to estimate the most likely parameters θ̂ could proceed as follows: 1) initialize some estimate of the parameters θ̂, then 2) recursively compute n̂ using those parameters and update θ̂ given the new n̂ until some convergence criterion is met. This approach may be thought of as a pseudoexpectation-maximization algorithm (Dempster et al. 1977; Vogelstein et al. 2009). In the following text, details are provided for each step.

INITIALIZING THE PARAMETERS.

Because the model introduced earlier is linear, the scale of F relative to n is arbitrary. Therefore before filtering, F is linearly mapped between zero and one, i.e., F ← (F − Fmin)/(Fmax − Fmin), where Fmin and Fmax are the observed minimum and maximum of F, respectively. Given this normalization, α is set to one. Because spiking is sparse in many experimental settings, F tends to be around baseline, so β is initialized to be the median of F and σ is initialized as the median absolute deviation of F, i.e., σ = mediant (|Ft − medians (Fs)|)/K, where mediani (Xi) indicates the median of X with respect to index i and K = 1.4785 is the correction factor when using the median absolute deviation as a robust estimator of the SD of a normal distribution. Because in these data the posterior tends to be relatively flat along the γ dimension (i.e., large changes in γ result in relatively small changes in the posterior), estimating γ is difficult. Further, previous work has shown that results are somewhat robust to minor variations in the time constant (Yaksi and Friedrich 2006); therefore γ is initialized at 1 − Δ/(1 s), which is fairly standard (Pologruto et al. 2004). Finally, λ is initialized at 1 Hz, which is between average baseline and evoked spike rate for data of interest.

ESTIMATING THE PARAMETERS GIVEN

n̂. Ideally, one could integrate out the hidden variables, to find the most likely parameters:

| (17) |

However, evaluating those integrals is not currently tractable. Therefore Eq. 17 is approximated by simply maximizing the parameters given the MAP estimate of the hidden variables:

| (18) |

where Ĉ and n̂ are determined using the above-described inference algorithm. The approximation in Eq. 18 is good whenever most of the mass in the integral in Eq. 18 is around the MAP sequence Ĉ.1 The argument from the right-hand side of Eq. 18 may be expanded:

| (19) |

Note that the right-hand side of Eq. 19 decouples λ from the other parameters. The maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) for the observation parameters {α, β, σ} is therefore given by:

| (20) |

Note that a rescaling of α may be offset by a complementary rescaling of Ĉ. Therefore because the scale of Ĉ is arbitrary (see Eqs. 2 and 3), α can be set to one without loss of generality. Plugging α = 1 into Eq. 20 and maximizing with respect to β yields:

| (21) |

Computing the gradient with respect to β, setting the answer to zero, and solving for β̂ yields β̂ = (1/T) ∑t (Ft − Ĉt). Similarly, computing the gradient of Eq. 20 with respect to σ, setting it to zero, and solving for σ̂ yields:

| (22) |

which is simply the root-mean-square of the residual error. Finally, the MLE of λ̂ is given by solving:

| (23) |

which, again, computing the gradient with respect to λ, setting it to zero, and solving for λ̂, yields λ̂ = T/(Δ ∑t n̂t), which is the inverse of the inferred average firing rate.

Iterations stop whenever 1) the iteration number exceeds some upper bound or 2) the relative change in likelihood does not exceed some lower bound. In practice, parameter estimates tend to converge after several iterations, given the above initializations.

Spatial filtering

In the preceding text, we assumed that the raw movie of fluorescence measurements collected by the experimenter had undergone two stages of preprocessing before filtering. First, the movie was segmented, to determine ROIs, yielding a vector F→t = (F1,t, … , FNp,t), which corresponded to the fluorescence intensity at time t for each of the Np pixels in the ROI (note that we use the X→ throughout to indicate row vectors in space vs. X to indicate column vectors in time). Second, at each time t, that vector was projected into a scalar, yielding Ft, the assumed input to the filter. In this section, the optimal projection is determined by considering a more general model:

where αx corresponds to the number of photons that are contributed due to calcium fluctuations Ct, and βx corresponds to the static photon emission at pixel x. Further, the noise is assumed to be both spatially and temporally white, with standard deviation (SD) σ, in each pixel (this assumption can always be approximately accurate by prewhitening; alternately, one could relax the spatial independence by representing joint noise over all pixels with a covariance matrix Σt, with arbitrary structure). Performing inference in this more general model proceeds in a nearly identical manner as before. In particular, the maximization, gradient, and Hessian become:

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

where F→ is an Np × T element matrix, 1T is a column vector of ones with length T, I is an Np × Np identity matrix, and ‖x‖F indicates the Frobenius norm, i.e., ‖x‖F2 = ∑i,j xi,j2, and the exponents and log operator on the vector MC again indicate element-wise operations. Note that to speed up computation, one can first project the background subtracted (Nc × T)-dimensional movie onto the spatial filter α→, yielding a one-dimensional time series F, reducing the problem to evaluating a T × 1 vector norm, as in Eq. 15.

The parameters α→ and β→ tend to be unknown and thus must be estimated from the data. Following the strategy developed in the previous section, we first initialize the parameters. Because each voxel contains some number of fluorophores, which sets both the baseline fluorescence and the fluorescence due to calcium fluctuations, let both the initial spatial filter and initial background be the median image frame, i.e., α̂x = β̂x = mediant (Fx,t). Given these robust initializations, the maximum likelihood estimator for each αx and βx is given by:

| (28a) |

| (28b) |

| (28c) |

| (28d) |

where the first equalities follow from Eq. 1 and the last equality follows from dropping irrelevant constants. Because this is a standard linear regression problem, let A = [Ĉ, 1T]T be a 2 × T element matrix and Yx = [αx, βx]T be a 2 × 1 element column vector. Substituting A and Yx into Eq. 28d yields:

| (29) |

which can be solved by computing the derivative of Eq. 29 with respect to Yx and setting to zero, or using Matlab notation: Ŷx = A\Fx. Note that solving Np two-dimensional quadratic problems is more efficient than solving a single (2 × Np)-dimensional quadratic problem. Also note that this approach does not regularize the parameters at all, by smoothing or sparsening, for instance. In the discussion we propose several avenues for further development, including the elastic net (Zou and Hastie 2005) and simple parametric models of the neuron. As in the scalar Ft case, we iterate estimating the parameters of this model θ = {α→, β→, σ, γ, λ} and the spike train n. Because of the free scale term discussed earlier, the absolute magnitude of α→ is not identifiable. Thus convergence is defined here by the “shape” of the spike train converging, i.e., the norm of the difference between the inferred spike trains from subsequent iterations, both normalized such that max(n̂t) = 1. In practice, this procedure converged after several iterations.

Overlapping spatial filters

It is not always possible to segment the movie into pixels containing only fluorescence from a single neuron. Therefore the above-cited model can be generalized to incorporate multiple neurons within an ROI. Specifically, letting the superscript i index the Nc neurons in this ROI yields:

|

where each neuron is implicitly assumed to be independent and each pixel is conditionally independent and identically distributed with variance σ2, given the underlying calcium signals. To perform inference in this more general model, let nt = [nt1, … , ntNc] and Ct = [Ct1, … , CtNc] be Nc-dimensional column vectors. Then, let Γ = diag (γ1, … , γNc) be an Nc × Nc diagonal matrix and let I and 0 be an identity and zero matrix of the same size, respectively, yielding:

| (32) |

and proceed as before. Note that Eq. 32 is very similar to Eq. 14, except that M is no longer bidiagonal, but rather, block bidiagonal (and Ct and nt are vectors instead of scalars), making the Hessian block-tridiagonal. Importantly, the Thomas algorithm, which is a simplified form of Gaussian elimination, finds the solution to linear equations with block-tridiagonal matrices in linear time, so the efficiency gained from using the tridiagonal structure is maintained for this block-tridiagonal structure (Press et al. 1992). Performing inference in this more general model proceeds similarly as before, letting α→ = [α→1, … , α→Nc]:

| (33) |

| (34) |

| (35) |

If the parameters are unknown, they must be estimated. Initialize β→ as above. Then, define αx = [αx1, … , αxNc]T and initialize manually by assigning some pixels to each neuron (of course, more sophisticated algorithms could be used, as described in the discussion). Given this initialization, iterations and stopping criteria proceed as before, with the minor modification of incorporating multiple spatial filters, yielding:

| (36) |

Now, generalizing the above single spatial filter case, let A = [Ĉ, 1T]T be an (Nc + 1) × T element matrix and Yx = [αx, βx]T be an (Nc + 1)-dimensional column vector. Then, one can again use Eq. 29 to solve to for α̂x and β̂x for all x.

Experimental methods

SLICE PREPARATION AND IMAGING.

All animal handling and experimentation were done according to the National Institutes of Health and local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Somatosensory thalamocortical or coronal slices 350–400 μm thick were prepared from C57BL/6 mice at age P14 as described (MacLean et al. 2005). Pyramidal neurons from layer V somatosensory cortex were filled with 50 μM Oregon Green BAPTA 1 hexapotassium salt (OGB-1; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) through the recording pipette or bulk loaded with an acetoxymethyl ester of Fura-2 (Fura-2 AM; Invitrogen). The pipette solution contained 130 mM K-methylsulfate, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.6 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM ATP-Mg, and 0.3 mM GTP-Tris (pH 7.2, 295 mOsm). After cells were fully loaded with dye, imaging was performed in one of two ways. First, when using Fura-2, images were collected using a modified BX50-WI upright microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) with a confocal spinning disk (Solamere Technology Group, Salt Lake City, UT) and an Orca charge-coupled device (CCD) camera from Hamamatsu Photonics (Shizuoka, Japan), at 33 Hz. Second, when using Oregon Green, images were collected using epifluorescence with the C9100-12 CCD camera from Hamamatsu Photonics, with arc-lamp illumination with excitation and emission band-pass filters at 480–500 and 510–550 nm, respectively (Chroma, Rockingham, VT). Images were saved and analyzed using custom software written in Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY.

All recordings were made using the Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), digitized with National Instruments 6259 multichannel cards and recorded using custom software written using the LabVIEW platform (National Instruments, Austin, TX). Square pulses of sufficient amplitude to yield the desired number of action potentials were given as current commands to the amplifier using the LabVIEW and National Instruments system.

FLUORESCENCE PREPROCESSING.

Traces were extracted using custom Matlab scripts to segment the mean image into ROIs. The Fura-2 fluorescence traces were inverted. Because some slow drift was sometimes present in the traces, each trace was Fourier transformed, and all frequencies <0.5 Hz were set to zero (0.5 Hz was chosen by eye); the resulting fluorescence trace was then normalized to be between zero and one.

RESULTS

Main result

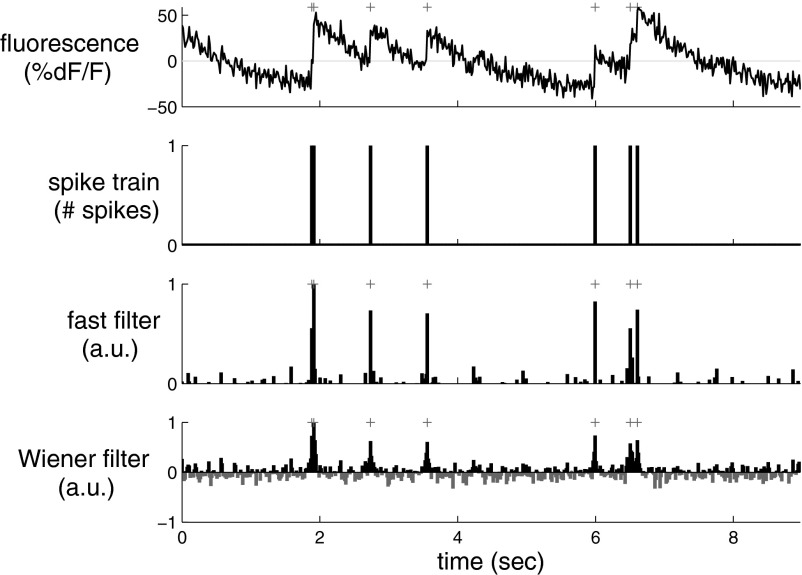

The main result of this study is that the fast filter can find the approximately most likely spike train n̂, very efficiently, and that this approach yields more accurate spike train estimates than optimal linear deconvolution. Figure 2 depicts a simulation showing this result. Clearly, the fast filter's inferred “spike train” (third panel) more closely resembles the true spike train (second panel) than the optimal linear deconvolution's inferred spike train (bottom panel; Wiener filter). Note that neither filter results in an integer sequence, but rather, each infers a real number at each time.

Fig. 2.

A simulation showing that the fast filter's inferred spike train is significantly more accurate than the output of the optimal linear deconvolution (Wiener filter). Note that neither filter constrains the inference to be a sequence of integers; rather, the fast filter relaxes the constraint to allow all nonnegative numbers and the Wiener filter allows for all real numbers. The restriction of the fast filter to exclude negative numbers eliminates the ringing effect seen in the Wiener filter output, resulting in a much cleaner inference. Note that the magnitude of the inferred spikes in the fast filter output is proportional to the inferred calcium jump size. Top panel: fluorescence trace. Second panel: spike train. Third panel: fast filter inference. Bottom panel: Wiener filter inference. Note that the gray bars in the bottom panel indicate negative spikes. Gray + symbols indicate true spike times. Simulation details: T = 400 time steps, Δ = 33.3 ms, α = 1, β = 0, σ = 0.2, τ = 1 s, λ = 1 Hz. Parameters and conventions are consistent across figures, unless indicated otherwise.

The Wiener filter implicitly approximates the Poisson spike rate with a Gaussian spike rate (see appendix B for details). A Poisson spike rate indicates that in each frame, the number of possible spikes is an integer, e.g., 0, 1, 2,.... The Gaussian approximation, however, allows any real number of spikes in each frame, including both partial spikes (e.g., 1.4) and negative spikes (e.g., −0.8). Although a Gaussian well approximates a Poisson distribution when rates are about 10 spikes per frame, this example is very far from that regime, so the Gaussian approximation performs relatively poorly. Further, the Wiener filter exhibits a “ringing” effect. Whenever fluorescence drops rapidly, the most likely underlying spiking signal is a proportional drop. Because the Wiener filter does not impose a nonnegative constraint on the underlying spiking signal, it infers such a drop, even when it causes nt to go below zero. After such a drop has been inferred, since no corresponding drop occurred in the true underlying signal here, a complementary jump is often then inferred, to realign the inferred signal with the observations. This oscillatory behavior results in poor inference quality. The nonnegative constraint imposed by the fast filter prevents this because the underlying signal never drops below zero, so the complementary jump never occurs either.

The inferred “spikes,” however, are still not binary events when using the fast filter. This is a by-product of approximating the Poisson distribution on spikes with an exponential (cf. Eq. 11a) because the exponential is a continuous distribution, versus the Poisson, which is discrete. The height of each spike is therefore proportional to the inferred calcium jump size and can be thought of as a proxy for the confidence with which the algorithm believes a spike occurred. Importantly, by using the Gaussian elimination and interior-point methods, as described in methods, the computational complexity of the fast filter is the same as an efficient implementation of the Wiener filter. Note that whereas the Gaussian approximation imposes a shrinkage prior on the inferred spike trains (Wu et al. 2006), the exponential approximation imposes a sparse prior on the inferred spike trains (Seeger 2008).

Figure 3 quantifies the relative performance of the fast and Wiener filters. The top left panel shows a typical simulated spike train (bottom), a corresponding relatively low SNR fluorescence trace (middle), and a relatively high SNR fluorescence trace (top), as examples. The top right panel compares the mean-squared-error (MSE) of the inferred spike trains using the fast (solid) and Wiener (dashed) filters, as a function of expected firing rate. Clearly, the fast filter has a better (lower) MSE for all rates. The bottom left panel shows a receiver-operator-characteristic (ROC) curve (Green and Swets 1966) for another simulation. Again, the fast filter dominates the Wiener filter, having a higher true positive rate for every false negative rate. Finally, the bottom right panel shows that the area under the curve (AUC) of the fast filter is better (higher) than that of the Wiener filter until the noise is very large. Collectively, these analyses suggest that for a wide range of firing rates and signal quality, the fast filter outperforms the Wiener filter.

Fig. 3.

In simulations, the fast filter quantitatively and significantly achieves higher accuracy than that of the Wiener filter. Top left: a spike train (bottom) and 2 simulated fluorescence traces, using the same spike train, one with low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) (middle) and one with high SNR (top). Simulation parameters: τ = 0.5 s, λ = 3 Hz, Δ = 1/30 s, σ = 0.6 (low SNR) and 0.1 (high SNR). Simulation parameters in other panels are the same, except where explicitly noted. Top right: mean-squared-error (MSE) for the fast (solid line) and Wiener (dashed-dotted line) filter, for varying the expected firing rate λ. Note that both axes are on a log-scale. Further note that the fast filter has a better (lower) MSE for all expected firing rates. Error bars show SD over 10 repeats. Simulation parameters: σ = 0.2, T = 1,000 time steps. Bottom left: receiver-operator-characteristic (ROC) curve comparing the fast (solid line) and Wiener (dashed-dotted line) filter. Note that for any given threshold, the Wiener filter has a better (higher) ratio of true positive rate to false positive rate. Simulation parameters as in top right panel, except σ = 0.35 and T = 10,000 time steps. Bottom right: area under the curve (AUC) for fast (solid line) and Wiener (dashed-dotted line) filter as a function of SD (σ). Note that the fast filter has a better (higher) AUC for all σ values until noise gets very high. The 2 simulated fluorescence traces in the top left panel show the bounds for SD here. Error bars show SD over 10 repeats.

Although in Fig. 2 the model parameters were provided, in the general case, the parameters are unknown and must therefore be estimated from the observations (as described in Learning the parameters in methods). Importantly, this algorithm does not require labeled training data, i.e., there is no need for joint imaging and electrophysiological experiments to estimate the parameters governing the relationship between the two. Figure 4 shows another simulated example; in this example, however, the parameters are estimated from the observed fluorescence trace. Again, it is clear that the fast filter far outperforms the Wiener filter.

Fig. 4.

A simulation showing that the fast filter achieves significantly more accurate inference than that of the Wiener filter, even when the parameters are unknown. For both filters, the appropriate parameters were estimated using only the data shown above, unlike Fig. 2, in which the true parameters were provided to the filters. Simulation details different from those in Fig. 2: T = 1,000 time steps, Δ = 16.7 ms, σ = 0.4.

Given the preceding two results, the fast filter was applied to biological data. More specifically, by jointly recording electrophysiologically and imaging, the true spike times are known and the accuracy of the two filters can be compared. Figure 5 shows a result typical of the 12 joint electrophysiological and imaging experiments conducted (see methods for details). As in the simulated data, the fast filter output is much “cleaner” than the Wiener filter: spikes are more well defined, and not spread out, due to the sparse prior imposed by the exponential approximation. Note that this trace is typical of epifluorescence techniques, which makes resolving individual spikes quite difficult, as evidenced by a few false positives in the fast filter. Regardless, the fast filter output is still more accurate than the Wiener filter, both as determined qualitatively by eye and as quantified (described in the following text). Furthermore, although it is difficult to see in this figure, the first four events are actually pairs of spikes, reflected by the width and height of the corresponding inferred spikes when using the fast filter. This suggests that although the scale of n is arbitrary, the fast filter can correctly ascertain the number of spikes within spike events.

Fig. 5.

In vitro data showing that the fast filter significantly outperforms the Wiener filter, using OGB-1. Note that all the parameters for both filters were estimated only from the fluorescence data in the top panel (i.e., not considering the voltage data at all). + symbols denote true spike times extracted from the patch data, not inferred spike times from F.

Figure 6 further evaluates this claim. While recording and imaging, the cell was forced to spike once, twice, or thrice for each spiking event. The fast filter infers the correct number of spikes in each event. On the contrary, there is no obvious way to count the number of spikes within each event when using the Wiener filter. We confirm this impression by computing the correlation coefficient, r2, between the sum of each filter's output and the true number of spikes, for all 12 joint electrophysiological and imaging traces. Indeed, whereas the fast filter's r2 was 0.47, the Wiener filter's r2 was −0.01 (after thresholding all negative spikes), confirming that the Wiener filter output cannot reliably convey the number of spikes in a fluorescence trace, whereas the fast filter can. Furthermore, varying the magnitude of the threshold for the Wiener filter to discard more “low-amplitude noise” could increase the magnitude of r2 (≤0.24), still significantly lower than the fast filter's r2 value. On the other hand, no amount of thresholding the fast filter yielded an improved r2, indicating that thresholding the output of the fast filter is unlikely to improve spike inference quality.

Fig. 6.

In vitro data with multispike events, showing that the fast filter can often resolve the correct number of spikes within each spiking event, while imaging using OGB-1, given sufficiently high SNR. It is difficult, if not impossible, to count the number of spikes given the Wiener filter output. Recording and fitting parameters as in Fig. 5. Note that the parameters were estimated using a 60-s-long recording, of which only a fraction is shown here, to more clearly depict the number of spikes per event.

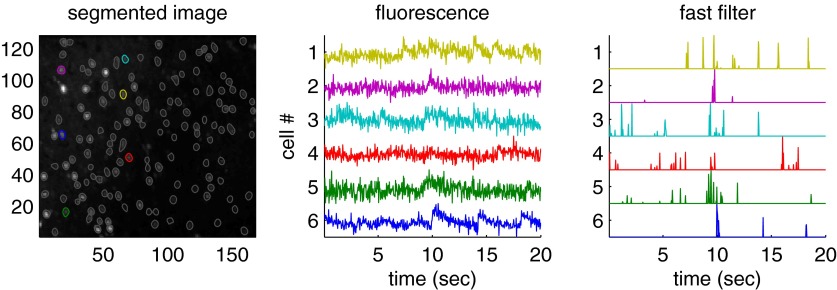

On-line analysis of spike trains using the fast filter

A central aim for this work was the development of an algorithm that infers spikes fast enough to use on-line while imaging a large population of neurons (e.g., >100). Figure 7 shows a segment of the results of running the fast filter on 136 neurons, recorded simultaneously, as described earlier in Experimental methods. Note that the filtered fluorescence signals show fluctuations in spiking much more clearly than the unfiltered fluorescence trace. These spike trains were inferred in less than imaging time, meaning that one could infer spike trains for the past experiment while conducting the subsequent experiment. More specifically, a movie with 5,000 frames of 100 neurons can be analyzed in about 10 s on a standard desktop computer. Thus if that movie was recorded at 50 Hz, whereas collecting the data would require 100 s, inferring spikes would require only 10 s, a 10-fold improvement over real time.

Fig. 7.

The fast filter infers spike trains from a large population of neurons imaged simultaneously in vitro, faster than real time. Specifically, inferring the spike trains from this 400-s-long movie including 136 neurons required only about 40 s on a standard laptop computer. The inferred spike trains much more clearly convey neural activity than the raw fluorescence traces. Although no intracellular “ground truth” is available from these population data, the noise seems to be reduced, consistent with the other examples with ground truth. Left: mean image field, automatically segmented into regions of interest (ROIs), each containing a single neuron using custom software. Middle: example fluorescence traces. Right: fast filter output corresponding to each associated trace. Note that neuron identity is indicated by color across the 3 panels. Data were collected using a confocal microscope and Fura-2, as described in methods.

Extensions

Earlier in methods, Data-driven generative model describes a simple principled first-order model relating the spike trains to the fluorescence trace. A number of the simplifying assumptions can be straightforwardly relaxed, as described next.

Replacing Gaussian observations with poisson.

In the preceding text, observations were assumed to have a Gaussian distribution. The statistics of photon emission and counting, however, suggest that a Poisson distribution would be more natural in some conditions, especially for two-photon data (Sjulson and Miesenböck 2007), yielding:

where αCt + β ≥ 0. One additional advantage to this model over the Gaussian model is that the variance parameter σ2 no longer exists, which might make learning the parameters simpler. Importantly, the log-posterior is still concave in C, as the prior remains unchanged, and the new log-likelihood term is a sum of terms concave in C:

| (38) |

The gradient and Hessian of the log-posterior can therefore be computed analytically by substituting the above likelihood terms for those implied by Eq. 1. In practice, however, modifying the filter for this model extension did not seem to significantly improve inference results in any simulations or data available at this time (not shown).

Allowing for a time-varying prior.

In Eq. 4, the rate of spiking is a constant. Often, additional knowledge about the experiment, including external stimuli or other neurons spiking, can provide strong time-varying prior information (Vogelstein et al. 2009). A simple model modification can incorporate that feature:

where λt is now a function of time. Approximating this time-varying Poisson with a time-varying exponential with the same time-varying mean (similar to Eq. 11a) and letting λ = [λ1, … , λT]TΔ, yields an objective function very similar to Eq. 15, so log-concavity is maintained and the same techniques may be applied. However, as before, this model extension did not yield any significantly improved filtering results (not shown).

Saturating fluorescence.

Although all the abovementioned models assumed a linear relationship between Ft and Ct, the relationship between fluorescence and calcium is often better approximated by the nonlinear Hill equation (Pologruto et al. 2004). Modifying Eq. 1 to reflect this change yields:

|

Importantly, log-concavity of the posterior is no longer guaranteed in this nonlinear model, meaning that converging to the global maximum is no longer guaranteed. Assuming a good initialization can be found, however, and Eq. 40 is more accurate than Eq. 1, then ascending the gradient for this model is likely to yield improved inference results. In practice, initializing with the inference from the fast filter assuming a linear model (e.g., Eq. 30) often resulted in nearly equally accurate inference, but inference assuming the above nonlinearity was far less robust than the inference assuming the linear model (not shown).

Using the fast filter to initialize the SMC filter.

A sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) method to infer spike trains can incorporate this saturating nonlinearity, as well as other model extensions discussed earlier (Vogelstein et al. 2009). However, this SMC filter is not nearly as computationally efficient as the fast filter proposed here. Like the fast filter, the SMC filter estimates the model parameters in a completely unsupervised fashion, i.e., from the fluorescence observations, using an expectation-maximization algorithm (which requires iterating between computing the expected value of the hidden variables—C and n—and updating the parameters). In Vogelstein and colleagues (2009), parameters for the SMC filter were initialized based on other data. Although effective, this initialization was often far from the final estimates and thus required a relatively large number of iterations (e.g., 20–25) before converging. Thus it seemed that the fast filter could be used to obtain an improvement to the initial parameter estimates, given an appropriate rescaling to account for the nonlinearity, thereby reducing the required number of iterations to convergence. Indeed, Fig. 8 shows how the SMC filter outperforms the fast filter on biological data and required only three to five iterations to converge on these data, given the initialization from the fast filter (which was typical). Note that the first few events of the spike train are individual spikes, resulting in relatively small fluorescence fluctuations, whereas the next events are actually spike doublets or triplets, causing a much larger fluorescence fluctuation. Only the SMC filter correctly infers the presence of isolated spikes in this trace, a frequently occurring result when the SNR is poor. Thus these two inference algorithms are complementary: the fast filter can be used for rapid, on-line inference, and for initializing the SMC filter, which can then be used to further refine the spike train estimate. Importantly, although the SMC filter often outperforms the fast filter, the fast filter is more robust, meaning that it more often works “out of the box.” This follows because the SMC filter operates on a highly nonlinear model that is not log-concave. Thus although the expectation-maximization algorithm used often converges to reasonable local maxima, it is not guaranteed to converge to global maxima and its performance in general will depend on the quality of the initial parameter estimates.

Fig. 8.

In vitro data with SNR of only about 3 (estimated by dividing the fluorescent jump size by the SD of the baseline fluorescence) for single action potentials depicting the fast filter, effectively initializing the parameters for the sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) filter, significantly reducing the number of expectation-maximization iterations to convergence, using OGB-1. Note that whereas the fast filter clearly infers the spiking events in the end of the trace, those in the beginning of the trace are less clear. On the other hand, the SMC filter more clearly separates nonspiking activity from true spikes. Also note that the ordinate on the third panel corresponds to the inferred probability of a spike having occurred in each frame.

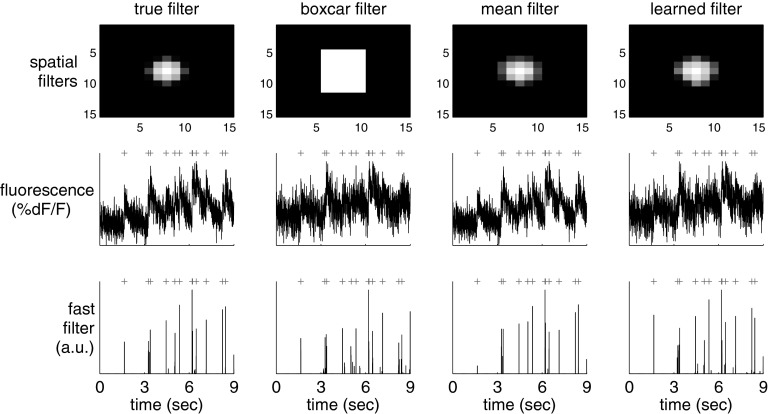

Spatial filter

In the preceding text, the filters operated on one-dimensional fluorescence traces. The raw data are in fact a time series of images that are first segmented into regions of interest (ROIs) and then (usually) spatially averaged to obtain a one-dimensional time series F. In theory, one could improve the effective SNR of the fluorescence trace by scaling each pixel according to its SNR. In particular, pixels not containing any information about calcium fluctuations can be ignored and pixels that are partially anticorrelated with one another could have weights with opposing signs.

Figure 9 demonstrates the potential utility of this approach. The top row shows different depictions of an ROI containing a single neuron. On the far left panel is the true spatial filter for this neuron. This particular spatial filter was chosen based on experience analyzing both in vitro and in vivo movies; often, it seems that the pixels immediately around the soma are anticorrelated with those in the soma (MacLean et al. 2005; Watson et al. 2008). This effect is possibly due to the influx of calcium from the extracellular space immediately around the soma. The standard approach, given such a noisy movie, would be to first segment the movie to find an ROI corresponding to the soma of this cell and then spatially average all the pixels found to be within this ROI. The second panel shows this standard “boxcar spatial filter.” The third panel shows the mean frame. The fourth panel shows the learned filter, using Eq. 29 to estimate the spatial filter and background. Clearly, the learned filter is very similar to the mean filter and the true filter.

Fig. 9.

A simulation demonstrating that using a better spatial filter can significantly enhance the effective SNR. The true spatial filter was a difference of Gaussians: a positively weighted Gaussian of small width and a negatively weighted Gaussian with larger width (both with the same center). Each column shows the spatial filter (top), one-dimensional fluorescence projection using that spatial filter (middle), and inferred spike train (bottom). From left to right, columns use the true, boxcar, mean, and learned spatial filter obtained using Eq. 29. Note that the learned filter's inferred spike train has fewer false positives and negatives than the boxcar and mean filters. Simulation parameters: α→ =  (0, 2I) − 0.5

(0, 2I) − 0.5 (0, 2.5I), where

(0, 2.5I), where  (μ, Σ) indicates a 2-dimensional Gaussian with mean μ and covariance matrix Σ, β→ = 0, σ = 0.2, τ = 0.85 s, λ = 5 Hz, Δ = 5 ms, T = 1,200 time steps.

(μ, Σ) indicates a 2-dimensional Gaussian with mean μ and covariance matrix Σ, β→ = 0, σ = 0.2, τ = 0.85 s, λ = 5 Hz, Δ = 5 ms, T = 1,200 time steps.

The middle panels of Figure 9 show the fluorescence traces obtained by background subtracting and then projecting each frame onto the corresponding spatial filter (black line) and true spike train (gray + symbols). The bottom panels show the inferred spike trains (black bars) using these various spatial filters and, again, the true spike train (gray + symbols). Although the performance is very similar for all of them, the boxcar filter's inferred spike train is not as clean.

Overlapping spatial filters

The preceding text shows that if the ROI contains only a single neuron, the effective SNR can be enhanced by spatially filtering. However, this analysis assumes that only a single neuron is in the ROI. Often, ROIs are overlapping, or nearly overlapping, making the segmentation problem more difficult. Therefore it is desirable to have an ability to crudely segment, yielding only a few neurons in each ROI, and then spatially filter within each ROI to pick out the spike trains of each neuron. This may be achieved in a principled manner by generalizing the model as described in Overlapping spatial filters in methods. The true spatial filters of the neurons in the ROI are often unknown and thus must be estimated from the data. This problem may be considered a special case of blind source separation (Bell and Sejnowski 1995; Mukamel et al. 2009). Figure 10 shows that given reasonable assumptions of spiking correlations and SNR, multiple signals can be separated. Note that separation occurs even though the signal is significantly overlapping (top panels). To estimate the spatial filters, they are initialized using the boxcar filters (middle panels). After a few iterations, the spatial filters converge to very close approximation to the true spatial filters [compare true (left) and learned (right) spatial filters for the two neurons]. Note that both the true and learned spatial filters yield much improved spike inference relative to the boxcar filter. This suggests that even when spatial filters of multiple neurons are significantly overlapping, each spike train is potentially independently recoverable.

Fig. 10.

Simulation showing that when 2 neurons' spatial filters are largely overlapping, learning the optimal spatial filters using Eq. 36 can yield improved inference of the standard boxcar type filters. The 3 columns show the effect of the true (left), boxcar (center), and learned (right) spatial filters. A: the sum of the 2 spatial filters for each approach, clearly depicting overlap. B: the spatial filters (top row), one-dimensional fluorescence projection, and inferred spike train (bottom row) for one of the neurons. C: same as B for the other neuron. Note that the inferred spike trains when using the learned filter are close to optimal, unlike the boxcar filter. Simulation parameters: α→1 =  ([−1, 0], 2I) − 0.5

([−1, 0], 2I) − 0.5 ([−1, 0], 2.5I), α→2 =

([−1, 0], 2.5I), α→2 =  ([1, 0], 2I) − 0.5

([1, 0], 2I) − 0.5 ([1, 0], 2.5I), β→ = 0, σ = 0.02, τ = 0.5 s, λ = 5 Hz, Δ = 5 ms, T = 1,200 time steps (not all time steps are shown).

([1, 0], 2.5I), β→ = 0, σ = 0.02, τ = 0.5 s, λ = 5 Hz, Δ = 5 ms, T = 1,200 time steps (not all time steps are shown).

DISCUSSION

Summary

This work describes an algorithm that finds the approximate maximum a posteriori (MAP) spike train, given a calcium fluorescence movie. The approximation is required because finding the actual MAP estimate is not currently computationally tractable. Replacing the assumed Poisson distribution on spikes with an exponential distribution yields a log-concave optimization problem, which can be solved using standard gradient ascent techniques (such as Newton–Raphson). This exponential distribution has an advantage over a Gaussian distribution by restricting spikes to be positive, which improves inference quality (cf. Fig. 2), is a better approximation to a Poisson distribution with low rate, and imposes a sparse constraint on spiking. Furthermore, all the parameters can be estimated from only the fluorescence observations, obviating the need for joint electrophysiology and imaging (cf. Fig. 4). This approach is robust, in that it works “out of the box” on all the in vitro data analyzed (cf. Figs. 5 and 6). By using the special banded structure of the Hessian matrix of the log-posterior, this approximate MAP spike train can be inferred fast enough on standard computers to use it for on-line analyses of over 100 neurons simultaneously (cf. Fig. 7).

Finally, the fast filter is based on a biophysical model capturing key features of the data and may therefore be straightforwardly generalized in several ways to improve accuracy. Unfortunately, some of these generalizations do not improve inference accuracy, perhaps because of the exponential approximation. Instead, the fast filter output can be used to initialize the more general SMC filter (Vogelstein et al. 2009), to further improve inference quality (cf. Fig. 8). Another model generalization allows incorporation of spatial filtering of the raw movie into this approach (cf. Fig. 9). Even when multiple neurons are overlapping, spatial filters may be estimated to obtain improved spike inference results (cf. Fig. 10).

Alternate algorithms

This work describes but one specific approach to solving a problem that does not admit an exact solution that is computationally feasible. Several other approaches warrant consideration, including 1) a Bayesian approach, 2) a greedy approach, and 3) different analytical approximations.

First, a Bayesian approach could use Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods to recursively sample spikes to estimate the full joint posterior distribution of the entire spike train, conditioned on the fluorescence data (Andrieu et al. 2001; Joucla et al. 2010; Mishchenko et al. 2010). Although enjoying several desirable statistical properties that are lacking in the current approach (such as consistency), the computational complexity of such an approach renders it inappropriate for the aims of this work.

Second, a common relatively expedient approximation to Bayesian sampling is a so-called greedy approach. Greedy algorithms are iterative, with each iteration adding another spike to the putative spike train. Each spike that is added is the most likely spike (thus the greedy term) or the one that most increases the likelihood of the fluorescence trace. Template matching, projection pursuit regression (Friedman and Stuetzle 1981), and matching pursuit (Mallat and Zhang 1993) are examples of such a greedy approach (the algorithm proposed by Grewe et al. (2010) could also be considered a special case of such a greedy approach).

Third, approximations other than the exponential distribution are possible. For instance, the Gaussian approximation is more appropriate for high firing rates, although in simulations, this more accurate approximation did not improve the Wiener filter output relative to the fast filter output (cf. Fig. 3). Perhaps the best approximation would use the closest log-concave relaxation to the Poisson model (Koenker and Mizera 2010). More formally, let P(i) represent the Poisson mass at i and let ln Q be some concave density. Then, one could find the log-density Q such that Q maximizes ∑i P(i)Q(i) − λ ∫ exp{Q(x)}dx over the space of all concave Q. The first term corresponds to the log-likelihood, equivalent to the Kullback–Leibler divergence (Cover and Thomas 1991), and the second is a Lagrange multiplier to ensure that the density exp{Q(x)} integrates to unity. This is a convex problem because the space of all concave Q is convex and the objective function is concave in Q. In addition, it is easy to show that the optimal Q has to be piecewise linear; this means that one need not search over all possible densities, but rather, simply vary Q(i) at the integers. Note that ∫ exp{Q(x)}dx can be computed explicitly for any piecewise linear Q. This optimization problem can be solved using simple interior point methods and, in fact, the Hessian of the inner loop of the interior point method will be banded (because enforcing concavity of Q is a local constraint). This approximation could potentially be more accurate than our exponential approximation. Further, this approximation encourages integer solutions for nt and is therefore of interest for future work.

The abovementioned three approaches may be thought of as complementary because each has unique advantages relative to the others. Both the greedy methods and the analytic approximations could potentially be used to initialize a Bayesian approach, possibly limiting the burn-in period, which can be computationally prohibitive in certain contexts. A greedy approach has the advantage of providing actual spike trains (i.e., binary sequences), unlike the analytic approximations. However, the actual spike trains could be quite far from the MAP spike train because greedy approaches, in general, have no guarantee of consistency. The analytic approximations, on the other hand, are guaranteed to converge to solutions close to the MAP spike train, where closeness is determined by the accuracy of the above approximation. Thus developing these distinct approaches and combining them is a potential avenue for further research.

Spatial filtering

Spatial filtering could be improved in a number of ways. For instance, pairing this approach with a crude but automatic segmentation tool to obtain ROIs would create a completely automatic algorithm that converts raw movies of populations of neurons into populations of spike trains. Furthermore, this filter could be coupled with more sophisticated algorithms to initialize the spatial filters when they are overlapping [for instance, principal component analysis (Horn and Johnson 1990) or independent component analysis (Mukamel et al. 2009)]. One could also use a more sophisticated model to estimate the spatial filters. One option would be to assume a simple parametric form of the spatial filter for each neuron (e.g., a basis set) and then merely estimate the parameters of that model. Alternately, one could regularize the spatial filters, using an elastic net type approach (Grosenick et al. 2009; Zou and Hastie 2005), to enforce both sparseness and smoothness.

Model generalizations

In this work, we made two simplifying assumptions that can easily be relaxed: 1) instantaneous rise time of the fluorescence transient after a spike and 2) constant background. In practice, often either or both of these assumptions are inaccurate. Specifically, genetic sensors tend to have a much slower rise time than that of organic dyes (Reiff et al. 2005). Further, the background often exhibits slow baseline drift due to movement, temperature fluctuations, laser power, and so forth, not to mention bleaching, which is ubiquitous for long imaging experiments. Both slow rise and baseline drift can be incorporated into our forward model using a straightforward generalization.

Consider the following illustrative example: the fluorescence rise time in a particular data set is quite slow, much slower than that of a single image frame. Thus fluorescence might be well modeled as the difference of two different calcium extrusion mechanisms, with different time constants. To model this scenario, one might proceed as follows: posit the existence of a two-dimensional time-varying signal, each like the calcium signal assumed in the simpler models described earlier. Therefore each signal has a time constant and each signal is dependent on spiking. Finally, the fluorescence could be a weighted difference of the two signals. To formalize this model and to generalize it, let 1) X = (X1, … , Xd) be a d-dimensional time-varying signal; 2) Γ be a d × d dynamics matrix, where diagonal elements correspond to time constants of individual variables, and off-diagonal elements correspond to dependencies across variables; 3) A be a d-dimensional binary column vector encoding whether each variable depends on spiking; and 4) α be a d-dimensional column vector of weights, determining the relative impact of each dimension on the total fluorescence signal. Given these conventions, we have the following generalized model:

Note that this model simplifies to the model proposed earlier when d = 1. Because X is still Markov, all the theory developed above still applies directly for this model. There are, however, additional complexities with regard to identifiability. Specifically, the parameters α and A are closely related. Thus we enforce that A is a known binary vector, simply encoding whether a particular element responds to spiking. The matrix Γ will not be uniquely identifiable, for the same reason that γ was not identifiable, as described in Learning the parameters in methods. Thus we would assume Γ was known, a priori. Note that other approaches to dealing with baseline drift are also possible, such as letting β be a time-varying state: βt = βt−1 + εt, where εt is a normal random variable with variance σβ2 that sets the effective drift rate. Both these models are the subjects of further development.

Concluding thoughts

In summary, the model and algorithm proposed in this work potentially provide a useful tool to aid in the analysis of calcium-dependent fluorescence imaging and establish the groundwork for significant further development.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant DC-00109 to J. T. Vogelstein; National Science Foundation (NSF) Faculty Early Career Development award, an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship, and a McKnight Scholar Award to L. Paninski; National Eye Institute Grant EY-11787 and the Kavli Institute for Brain Studies award to R. Yuste and the Yuste laboratory; and an NSF Collaborative Research in Computational Neuroscience award IIS-0904353, awarded jointly to L. Paninski and R. Yuste.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank V. Bonin for helpful discussions.

APPENDIX A: PSEUDOCODE

Algorithm 1 Pseudocode for inferring the approximately most likely spike train, given fluorescence data. Note that the algorithm is robust to small variations ξz, ξn. The equations listed below refer to the most general equations in the text (simpler equations could be substituted when appropriate). Curly brackets, {·}, indicate comments.

| 1: initialize parameters, θ (see Initializing the parameters in methods) |

| 2: while convergence criteria not met do |

| 3: for z = 1,0.1,0.01, … , ξz do {interior point method to find Ĉ} |

| 4: Initialize nt = ξn for all t = 1, … , T, C1 = 0 and Ct = γCt−1 + nt for all t = 2, … , T |

| 5: let Cz be the initialized calcium, and P̂z, be the posterior given this initialization |

| 6: while P̂z′ < P̂z do {Newton–Raphson with backtracking line searches} |

| 7: compute g using Eq. 34 |

| 8: compute H using Eq. 35 |

| 9: compute d using H\g {block-tridiagonal Gaussian elimination} |

| 10: let Cz′ = Cz + sd, where s is between 0 and 1, and P̂z′ > P̂z {backtracking line search} |

| 11: end while |

| 12: end for |

| 13: check convergence criteria |

| 14: update α→ and β→ using Eq. 36 {only if spatial filtering} |

| 15: let σ be the root-mean square of the residual |

| 16: let λ = T/(ΔΣtn̂t) |

| 17: end while |

APPENDIX B: WIENER FILTER

The Poisson distribution in Eq. 4 can be replaced with a Gaussian instead of an exponential distribution, i.e.,

(λΔ, λΔ) that, when plugged into Eq. 7, yields:

(λΔ, λΔ) that, when plugged into Eq. 7, yields:

| (B1) |

Note that since fluorescence integrates over Δ, it makes sense that the mean scales with Δ. Further, since the Gaussian here is approximating a Poisson with high rate (Sjulson and Miesenböck 2007), the variance should scale with the mean. Using the same tridiagonal trick as before, Eq. 11b can be solved using Newton–Raphson once (because this expression is quadratic in n). Writing the above in matrix notation, substituting Ct − γCt−1 for nt, and letting α = 1 yields:

| (B2) |

which is quadratic in C. The gradient and Hessian are given by:

| (B3) |

| (B4) |

Note that this solution is the optimal linear solution, under the assumption that spikes follow a Gaussian distribution, and is often referred to as the Wiener filter, regression with a smoothing prior, or ridge regression (Boyd and Vandenberghe 2004). Estimating the parameters for this model follows a pattern similar to that described in Learning the parameters in methods.

Footnotes

Equation 18 may be considered a crude Laplace approximation (Kass and Raftery 1995).

REFERENCES

- Andrieu et al., 2001. Andrieu C, Barat É, Doucet A. Bayesian deconvolution of noisy filtered point processes. IEEE Trans Signal Process 49: 134–146, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Bell and Sejnowski, 1995. Bell AJ, Sejnowski TJ. An information-maximisation approach to blind separation and blind deconvolution. Neural Comput 7: 1129–1159, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd and Vandenberghe, 2004. Boyd S, Vandenberghe L. Convex Optimization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Cover and Thomas, 1991. Cover TM, Thomas JA. Elements of Information Theory: New York: Wiley–Interscience, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham et al., 2008. Cunningham JP, Shenoy KV, Sahani M. Fast Gaussian process methods for point process intensity estimation. In: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2008) New York: IEEE Press, 2008, p. 192–199 [Google Scholar]

- Dempster et al., 1977. Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J R Stat Soc B Methodol 39: 1–38, 1977 [Google Scholar]

- Friedman and Stuetzle, 1981. Friedman JH, Stuetzle W. Projection pursuit regression. J Am Stat Assoc 76: 817–823, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- Garaschuk et al., 2007. Garaschuk O, Griesbeck O, Konnerth A. Troponin c-based biosensors: a new family of genetically encoded indicators for in vivo calcium imaging in the nervous system. Cell Calcium 42: 351–361, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göbel and Helmchen, 2007. Göbel W, Helmchen F. In vivo calcium imaging of neural network function. Physiology (Bethesda) 22: 358–365, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green and Swets, 1966. Green DM, Swets JA. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics. New York: Wiley, 1966 [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg et al., 2008. Greenberg DS, Houweling AR, Kerr JND. Population imaging of ongoing neuronal activity in the visual cortex of awake rats. Nat Neurosci 11: 749–751, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewe et al., 2010. Grewe BF, Langer D, Kasper H, Kampa BM, Helmchen F. High-speed in vivo calcium imaging reveals neuronal network activity with near-millisecond precision. Nat Methods 7: 399–405, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosenick et al., 2009. Grosenick L, Anderson T, Smith SJ. Elastic source selection for in vivo imaging of neuronal ensembles. In: Proceedings of the Sixth IEEE International Conference on Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro (ISBI '09) New York: IEEE Press, 2009, p. 1263–1266 [Google Scholar]

- Holekamp et al., 2008. Holekamp TF, Turaga D, Holy TE. Fast three-dimensional fluorescence imaging of activity in neural populations by objective-coupled planar illumination microscopy. Neuron 57: 661–672, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn and Johnson, 1990. Horn R, Johnson C. Matrix Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- Huys et al., 2006. Huys QJM, Ahrens MB, Paninski L. Efficient estimation of detailed single-neuron models. J Neurophysiol 96: 872–890, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegaya et al., 2004. Ikegaya Y, Aaron G, Cossart R, Aronov D, Lampl I, Ferster D, Yuste R. Synfire chains and cortical songs: temporal modules of cortical activity. Science 304: 559–564, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joucla et al., 2010. Joucla S, Pippow A, Kloppenburg P, Pouzat C. Quantitative estimation of calcium dynamics from radiometric measurements: a direct, nonratioing method. J Neurophysiol 103: 1130–1144, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass and Raftery, 1995. Kass R, Raftery A. Bayes factors. J Am Stat Assoc 90: 773–795, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Koenker and Mizera, 2010. Koenker R, Mizera I. Quasi-concave density estimation. Ann Stat 38: 2998–3027, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Lee and Seung, 1999. Lee DD, Seung HS. Learning the parts of objects by non-negative matrix factorization. Nature 401: 788–791, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin et al., 2004. Lin Y, Lee DD, Saul LK. Nonnegative deconvolution for time of arrival estimation. In: Proceedings of the 2004 International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP 2004) New York: IEEE Press, 2004, p. 377–380 [Google Scholar]

- Luo et al., 2008. Luo L, Callaway EM, Svoboda K. Genetic dissection of neural circuits. Neuron 57: 634–660, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean et al., 2005. MacLean J, Watson B, Aaron G, Yuste R. Internal dynamics determine the cortical response to thalamic stimulation. Neuron 48: 811–823, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat and Zhang, 1993. Mallat S, Zhang Z. Matching pursuit with time-frequency dictionaries. IEEE Trans Signal Process 41: 3397–3415, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Mank et al., 2008. Mank M, Santos AF, Direnberger S, Mrsic-Flogel TD, Hofer SB, Stein V, Hendel T, Reiff DF, Levelt C, Borst A, Bonhoeffer T, Hbener M, Griesbeck O. A genetically encoded calcium indicator for chronic in vivo two-photon imaging. Nat Methods 5: 805–811, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao et al., 2001. Mao B, Hamzei-Sichani F, Aronov D, Froemke R, Yuste R. Dynamics of spontaneous activity in neocortical slices. Neuron 32: 883–898, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham and Conchello, 1999. Markham J, Conchello J-A. Parametric blind deconvolution: a robust method for the simultaneous estimation of image and blur. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis 16: 2377–2391, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishchenko et al. Mishchenko Y, Vogelstein J, Paninski L. A Bayesian approach for inferring neuronal connectivity from calcium fluorescent imaging data. Ann Appl Stat http://www.imstat.org/aoas/nextissue.html [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel et al., 2009. Mukamel EA, Nimmerjahn A, Schnitzer MJ. Automated analysis of cellular signals from large-scale calcium imaging data. Neuron 63: 747–760, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama et al., 2007. Nagayama S, Zeng S, Xiong W, Fletcher ML, Masurkar AV, Davis DJ, Pieribone VA, Chen WR. In vivo simultaneous tracing and Ca2+ imaging of local neuronal circuits. Neuron 53: 789–803, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Grady and Pearlmutter, 2006. O'Grady PD, Pearlmutter BA. Convolutive non-negative matrix factorisation with a sparseness constraint. In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing, 2006 New York: IEEE Press, 2006, p. 427–432 [Google Scholar]

- Paninski et al., 2009. Paninski L, Ahmadian Y, Ferreira D, Koyama S, Rad KR, Vidne M, Vogenstein J, Wu W. A new look at state-space models for neural data. J Comput Neurosci. doi: 10.1007/s10827-009-0179-x, 1–20, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pologruto et al., 2004. Pologruto TA, Yasuda R, Svoboda K. Monitoring neural activity and [Ca2+] with genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. J Neurosci 24: 9572–9579, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portugal et al., 1994. Portugal LF, Judice JJ, Vicente LN. A comparison of block pivoting and interior-point algorithms for linear least squares problems with nonnegative variables. Math Comput 63: 625–643, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Press et al., 1992. Press W, Teukolsky S, Vetterling W, Flannery B. Numerical Recipes in C. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Reiff et al., 2005. Reiff DF, Ihring A, Guerrero G, Isacoff EY, Joesch M, Nakai J, Borst A. In vivo performance of genetically encoded indictors of neural activity in flies. J Neurosci 25: 4766–4778, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki et al., 2008. Sasaki T, Takahashi N, Matsuki N, Ikegaya Y. Fast and accurate detection of action potentials from somatic calcium fluctuations. J Neurophysiol 100: 1668–1676, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz et al., 1998. Schwartz T, Rabinowitz D, Unni VK, Kumar VS, Smetters DK, Tsiola A, Yuste R. Networks of coactive neurons in developing layer 1. Neuron 20: 1271–1283, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger, 2008. Seeger M. Bayesian inference and optimal design for the sparse linear model. J Machine Learn Res 9: 759–813, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Sjulson and Miesenböck, 2007. Sjulson L, Miesenböck G. Optical recording of action potentials and other discrete physiological events: a perspective from signal detection theory. Physiology (Bethesda) 22: 47–55, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetters et al., 1999. Smetters D, Majewska A, Yuste R. Detecting action potentials in neuronal populations with calcium imaging. Methods 18: 215–221, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein et al., 2009. Vogelstein JT, Watson BO, Packer AM, Yuste R, Jedynak B, Paninski L. Spike inference from calcium imaging using sequential Monte Carlo methods. Biophys J 97: 636–655, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace et al., 2008. Wallace DJ, zum Alten Borgloh SM, Astori S, Yang Y, Bausen M, Kgler S, Palmer AE, Tsien RY, Sprengel R, Kerr JND, Denk W, Hasan MT. Single-spike detection in vitro and in vivo with a genetic Ca2+ sensor. Nat Methods 5: 797–804, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson et al., 2008. Watson BO, MacLean JN, Yuste R. Up states protect ongoing cortical activity from thalamic inputs. PLoS ONE 3: e3971, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al., 2006. Wu MC-K, David SV, Gallant JL. Complete functional characterization of sensory neurons by system identification. Annu Rev Neurosci 29: 477–505, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksi and Friedrich, 2006. Yaksi E, Friedrich RW. Reconstruction of firing rate changes across neuronal populations by temporally deconvolved Ca2+ imaging. Nat Methods 3: 377–383, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste and Konnerth, 2005. Yuste R, Konnerth A. Editors. Imaging in Neuroscience and Development: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]