Abstract

Distinct parasympathetic postganglionic neurons mediate contractions and relaxations of the guinea pig airways. We set out to characterize the vagal inputs that regulate contractile and relaxant airway parasympathetic postganglionic neurons. Single and dual retrograde neuronal tracing from the airways and esophagus revealed that distinct, but intermingled, subsets of neurons in the compact formation of the nucleus ambiguus (nAmb) innervate these two tissues. Tracheal and esophageal neurons identified in the nAmb were cholinergic. Esophageal projecting neurons also preferentially (greater than 70%) expressed the neuropeptide CGRP, but could not otherwise be distinguished immunohistochemically from tracheal projecting preganglionic neurons. Few tracheal or esophageal neurons were located in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Electrical stimulation of the vagi in vitro elicited stimulus dependent tracheal and esophageal contractions and tracheal relaxations. The voltage required to evoke tracheal smooth muscle relaxation was significantly higher than that required for evoking either tracheal contractions or esophageal longitudinal striated muscle contractions. Together our data support the hypothesis that distinct vagal preganglionic pathways regulate airway contractile and relaxant postganglionic neurons. The relaxant preganglionic neurons can also be differentiated from the vagal motor neurons that innervate the esophageal striated muscle.

Keywords: airway innervation, parasympathetic nervous system, non-adrenergic non-cholinergic, esophageal motor neurons, nucleus ambiguus

Introduction

The guinea pig is commonly used as a model for studying the neural control of airway smooth muscle tone. Electrical stimulation of the vagi produces both cholinergic contractile and non-adrenergic non-cholinergic relaxant responses which are mediated via distinct parasympathetic postganglionic neurons innervating the airway smooth muscle (reviewed in Mazzone and Canning, 2002a). The cholinergic contractile postganglionic neurons are located in intrinsic parasympathetic ganglia residing in or near the adventitial wall of the trachea and large airways (Baluk and Gabella, 1989; Canning and Undem, 1993; Myers, 2000; Mazzone and McGovern, 2010). By contrast, the relaxant neurons express neuronal nitric oxide synthase and vasoactive intestinal peptide (Fischer et al., 1998) and reside within the myenteric plexus of the adjacent esophagus (Canning and Undem, 1993; Fischer et al., 1998). Relaxant neurons are also distinct from another recently described population of esophageal myenteric neurons that project to the trachea as the latter are cholinergic and express the calcium binding protein calretinin (Mazzone and McGovern, 2010).

The existence of distinct postganglionic neurons controlling contractile and relaxant airway responses raises the question of whether these neurons are in turn regulated by common or distinct preganglionic inputs. In guinea pigs, postganglionic neurons innervating the airways receive input from motor neurons via the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) of the vagus (Baluk and Gabella, 1989; Canning and Undem, 1993). Previous anatomical and functional studies in a variety of species indicate that vagal motor neurons originate in either the nucleus ambiguus (nAmb) or the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (dmnX) or sometimes in the reticular formation region that lies between the dmnX and nAmb (known as the intermediate zone; Haxhiu and Loewy, 1996; Kc et al., 2004; Atoji et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2006; Mazzone and McGovern, 2010). Whilst, some RLN fibers comprise the preganglionic autonomic neurons innervating the parasympathetic postganglionic pathways that ultimately innervate end organs in the airways and esophagus, others are classic motor neurons that directly innervate skeletal muscles, within the larynx and esophagus. The brainstem organization of the vagal motor fibers contained in the guinea pig RLN is unknown as is the identity of the preganglionic neurons controlling airway contractile and relaxant responses. Thus the aim of the present study was to further characterize the anatomical and functional organization of the vagal pathways that control airway and esophageal muscles in the guinea pig. We hypothesize that brainstem topographical organization, neurochemical phenotype and functional attributes will distinguish distinct vagal subpopulations regulating airway contractile and relaxant responses.

Materials and Methods

All experiments, approved by accredited institutional Animal Ethics Committees, were performed on male Hartley guinea pigs (200–350 g; n = 63).

DiI retrograde tracing to map the brainstem distribution of airway and esophageal neurons

Surgery and DiI injections

DiI retrograde neuronal tracing was used to identify the anatomical location and origin of the vagal motor neuron pools that project to the extrathoracic airways (trachea and larynx) and esophagus using general methods previously described (Mazzone and McGovern, 2010). Guinea pigs (n = 15 in total) were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane in medical oxygen. The extrathoracic trachea and associated nerves were exposed via a ventral incision in the animals’ neck. Initially we set out to identify the brainstem origins of the entire population of motor neurons in the extrathoracic RLN. The central cut end of a RLN (either left or right, cut at the level of the thoracic inlet) was placed in a small fabricated isolation chamber and 10 μl of 2% DiI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) was applied to the nerve stump for 5 min (n = 4 experiments). After removing the excess DiI, the nerve was then returned to its original in situ position and the wound sutured. Using the same method, motor neurons whose axons remained in the distalmost end of the RLN were retrogradely labeled by applying DiI to the central cut end of the nerve at its termination at the base of the larynx (i.e., most tracheal and esophageal motor axons would have exited the nerve proximal to this site, leaving only the axons of laryngeal motor neurons) (n = 3 experiments). To selectively retrogradely trace tracheal and esophageal motor neurons, a total volume of 2 μl of 2% DiI was injected using a 10 μl Hamilton glass microsyringe into 2–3 location of either the extrathoracic tracheal adventitia (n = 4 experiments) or the cervical esophageal wall (n = 4 experiments) between the muscularis and mucosal layers (Mazzone and McGovern, 2010). In all instances, great care was taken to avoid unwanted spread of the dye onto neighboring tissues.

Tissue processing and analysis

Animals were allowed to recover for 7 days at which time they were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg i.p.) and transcardially perfused with 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brainstems were removed and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 2 h, then cryoprotected in 20% sucrose at 4°C overnight. Brainstems were rapidly frozen with gaseous CO2 and sectioned coronally at 50 μm using a Leica freezing microtome. Every section was collected in series from approximately 3 mm caudal to 3 mm rostral of the Obex, mounted onto gelatine-coated slides, coverslipped with buffered glycerol, and viewed immediately with an Olympus BX51 fluorescent microscope. The total number of traced neurons in both the nAmb and dmnX were counted for every section. Only cells displaying evidence of a nucleus were included in the counts (i.e., cells sectioned near the midline of the soma) in order to reduce the likelihood of recounting the same neuron in adjacent sections. In every animal, the section containing the Obex was identified (defined as the level at which the fourth ventricle transitions into the central canal) and designated as the reference point (or section number 0). Serial sections rostral and caudal to the Obex were numbered starting from 1 in each direction, allowing the rostrocaudal location (relative to the Obex) of traced neurons in any given section to be calculated by multiplying the number of the section in the series by the section thickness (50 μm). Representative examples of traced neurons from each location were photographed for offline assessment of somal size using analysis tools available in ImageJ software (NIH, USA http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Dual fluorescent cholera toxin B retrograde tracing to assess whether common or distinct brainstem neurons project to the airways and esophagus

Guinea pigs (n = 4) were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane. The extrathoracic trachea and esophagus were exposed following which a single injection (1 μl) of a 2% solution of cholera toxin B subunit (CTb) conjugated to AlexaFluor 594 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) was injected into the tracheal adventitia and (in the same animal) a single injection (1 μl) of a 2% solution of CTb conjugated to AlexaFluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) was injected into the cervical esophagus (as described above). Again, great care was taken to prevent unwanted spread of dye to neighboring tissues. Following the dual injections, animals were allowed to recover for 7 days at which time they were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg i.p.) and transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brainstems were removed and processed as described above. In each experiment, the total number of traced neurons (i.e., either red or green neurons) as well as the number of double labeled neurons (i.e., neurons that appeared both red and green) was quantified.

Immunohistochemical characterization of the neurochemical phenotype of cholera toxin B traced neurons

The neurochemical profile of neurons projecting to the trachea or esophagus was compared using standard immunohistochemical staining of retrogradely labeled neurons (Mazzone and McGovern, 2006, 2008, 2010). Guinea pigs (n = 23) were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane and 1–2 μl of CTb conjugated to AlexaFluor 488 was injected either into the tracheal adventitia or into the cervical esophagus as described above. Animals were allowed to recover for 7 days at which time they were transcardially perfused for tissue collection as described above. 50 μm sections were incubated for 1 h in blocking solution (10% horse serum), and then overnight (at room temperature) in PBS/0.3% Triton X-100/2% horse serum along with the primary antisera of interest (Table 1). Sections were washed several times with PBS, and then incubated with the appropriate AlexaFluor 594 conjugated secondary antisera (Table 1). Sections were washed with PBS, mounted onto gelatine slides, coverslipped with buffered glycerol and viewed immediately. In additional experiments, brainstems were harvested from animals (n = 6) that had not undergone prior retrograde tracing. These tissues were processed (as above) to quantify the expression of selected neurochemical markers in the general population of cholinergic neurons [Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) positive] in the nAmb or dmnX using double labeling immunohistochemistry. Negative control experiments were performed by excluding the primary antisera. We have previously used these antisera to characterize a variety of neural cell types (Mazzone and Canning, 2002c; Mazzone and McGovern, 2006, 2008, 2010). Data were quantified by counting and/or measuring cells as described above.

Table 1.

Details of primary and secondary antibodies used for immunohistochemical staining.

| Host | Dilution | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRIMARY ANTIBODIES | |||

| Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) | Goat | 1:100 | Millipore, Australia. |

| CGRP (catalog# RPN 1842) | Rabbit | 1:4000 | Amersham, UK. |

| Calbindin D28k | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Swant Bellinzona, Switzerland. |

| Calretinin | Rabbit | 1:1000 | Swant Bellinzona, Switzerland. |

| Neurofilament 160 kDa (clone NNI8) | Mouse | 1:1000 | Millipore, Australia. |

| Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) | Sheep | 1:4000 | Gift Dr Colin Anderson, University of Melbourne, Australia. |

| Substance P (clone NC1) | Rat | 1:200 | Millipore, Australia. |

| Vasoactive intestinal peptide | Rabbit | 1:400 | Millipore, Australia. |

| SECONDARY ANTIBODIES | |||

| AlexaFluor 594 anti-goat IgG (H + L) | Donkey | 1:200 | Molecular Probes Eugene, OR, USA. |

| AlexaFluor 594 anti-rat IgG (H + L) | Goat | 1:200 | Molecular Probes Eugene, OR, USA. |

| AlexaFluor 594 anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) | Donkey | 1:200 | Molecular Probes Eugene, OR, USA. |

| AlexaFluor 594 anti-mouse IgG (H + L) | Donkey | 1:200 | Molecular Probes Eugene, OR, USA. |

In vitro functional studies comparing vagally mediated airway and esophageal responses

Tissue dissection and physiological assays

Vagal cholinergic-mediated tracheal smooth muscle contractions, NANC tracheal relaxations, and cholinergic contractions of the longitudinal striated muscle in the esophagus were conducted using in vitro preparations similar to those described by others (Canning and Undem, 1993; Kerr, 2002). Guinea pigs (n = 12) were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg i.p.) and exsanguinated. The trachea and adjacent esophagus, along with the both vagi and the associated RLNs, were removed en bloc and pinned to the base of a sylgard-lined water-jacketed dissection dish that was continuously over-filled with warmed (37°C), oxygenated Krebs bicarbonate buffer [composition (mM) NaCl (118), KCl (5.4), NaHPO4 (1), MgSO4 (1.2), CaCl2 (1.9), NaHCO3 (25), and dextrose (11.1)]. Three micromolar indomethacin and 2 μM propranolol were added to the buffer to prevent any potential local effects of prostaglandins or catecholamines on the tissues under study (Mazzone and Canning, 2002d). The tissues were then cleaned of any excess connective tissue before proceeding.

For monitoring vagally evoked tracheal contractions, the esophagus was first carefully removed to prevent any opposing NANC relaxant influence. For NANC relaxation experiments, the esophagus was left intact and great care was taken not to disrupt the tissue interconnecting the trachea and esophagus (as this contains the axons of the NANC relaxant neurons that innervate the trachea; Fischer et al., 1998). In both of these preparations, the seventh and eighth cartilage rings (caudal to the larynx) were sutured to a Grass FT03C force transducer for monitoring isometric tension across the trachealis muscle. To measure esophageal striated muscle contractions, the trachea was first carefully removed from the preparation and the esophagus was cut open longitudinally along the ventral surface. The mucosa was removed using sharp dissection. The caudalmost end of the esophagus was sutured to a stationary glass rod while the rostral end was sutured to an isometric force transducer as described above. In all experiments, output from the force transducer was amplified and filtered (Grass Polygraph Model 79D, Grass Technologies RI, USA), digitized (Micro1401 A-D converter, CED, Cambridge, UK), and recorded using Spike II software (CED, Cambridge, UK). Baseline (passive) tracheal and esophageal tension was set at 1.5–2 g which is optimal for these preparations (determined in preliminary experiments or shown previously; Kerr, 2002; Mazzone and Canning, 2002d). Following 60 min of equilibration, 5 μM capsaicin was added to the buffer in attempt to functionally desensitize neuropeptide containing C-fibers (Canning and Undem, 1993; Kajekar and Myers, 2008). Any contractile effects of capsaicin were allowed to dissipate before continuing with the experiment. Esophageal contraction experiments also included 1 μM atropine to prevent the confounding effects of acetylcholine acting at muscarinic cholinergic receptors, while NANC tracheal relaxation experiments included both 1 atropine and 10 μM histamine to prevent opposing cholinergic contractile responses and to provide a basal tracheal contraction for studying relaxations, respectively (Mazzone and Canning, 2002d; Kesler et al., 2002). All buffer drugs were purchased from Sigma, Australia.

Vagi were stimulated using a custom built platinum bipolar electrode (0.5 mm diameter wire, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota USA) and a Grass Instruments s48 stimulator (RI, USA). Voltage and frequency response functions were generated by either varying voltage (1–20 V) at an optimum stimulating frequency or by varying frequency (1–180 Hz) at supramaximum voltage (n = 4 experiments each for tracheal contractions, tracheal relaxations, and esophageal contractions). Initially in all experiments the pulse duration was set at 0.5 ms, however the train duration was varied (1–10 s) between the three different experiment protocols to allow for the different response kinetics. That is, in preliminary experiments we determined that nicotinic cholinergic evoked esophageal contractions were maximal within 1 s of electrical stimulation, whereas 10 s trains were optimal for muscarinic cholinergic and NANC tracheal responses. After assessing the voltage and frequency-dependency of responses at pulse durations of 0.5 ms, responses evoked by the optimum stimulation voltage and frequency were reassessed at 2 ms pulse durations. In three experiments, voltage and frequency dependent esophageal contractile responses were compared before and 30 min after bath application of the effect of the CGRP1 receptor antagonist (CGRP8–37; 1 μM; Sigma, Australia).

Functional data analysis

The magnitude of each response (contraction or relaxation) for any given preparation was expressed as a percentage of the maximum vagus nerve evoked response irrespective of stimulation parameters. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and the voltage or frequency required to evoke 50% of the maximum response (EV50 and EF50, respectively) were calculated from each experiment using GraphPad Prism version 5.03 (for Windows).

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were made using t-tests or one way ANOVAs followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons method where appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Organization of vagal motor neurons in the nucleus ambiguus

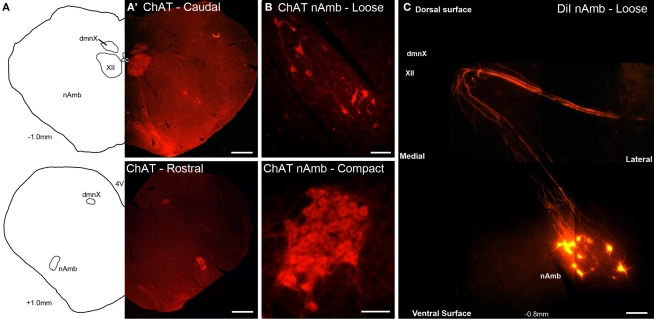

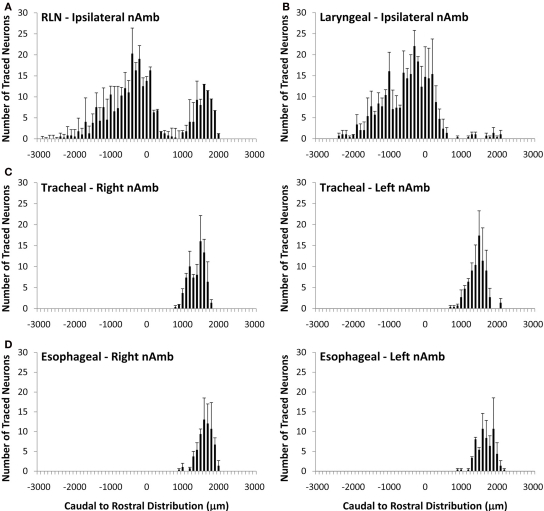

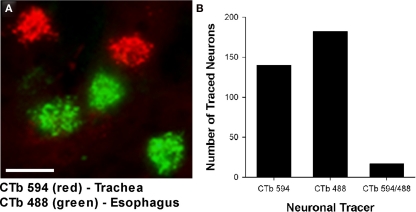

Cholinergic neurons in the guinea pig nAmb extended in a column from approximately 3 mm rostral to 3 mm caudal to the Obex (Figure 1A). The neurons in the rostral nAmb were smaller in size (ranging from 70 to 120 μm in perimeter), somewhat spherical in shape and displayed a compact arrangement. Neurons in the caudal nAmb were larger (ranging from 120 to 190 μm in perimeter), irregular in shape and more loosely arranged (Figure 1B). Retrograde tracing using DiI applied to the central cut end of the right or left cervical RLN (at the level of the thoracic inlet) labeled neurons throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the ipsilateral nAmb. Traced neurons were largely confined to two neuronal pools: one spanning from the Obex to 2.6 mm caudal to the Obex and the other spanning 1.0–2.6 mm rostral to the Obex (Figures 1C and 2A). No traced neurons were identified in the contralateral nAmb following unilateral nerve tracing (not shown). DiI labeling was intense in cell soma and also clearly visible in the axons and processes of nAmb neurons throughout the neuropil of the brainstem (Figure 1C). Retrograde tracing from the distal end of the cervical RLN (at the point immediately adjacent to the base of the larynx) labeled neurons only in the ipsilateral caudal nAmb neuronal pool (Figure 2B). By contrast, tracing from either the tracheal adventitia or the esophageal wall labeled cells bilaterally only in the rostral nAmb neuronal pool (Figures 2C,D). There was no apparent difference in the number of cells labeled from either the trachea or esophagus in the left and right nAmb (i.e., there was no anatomical evidence for lateral dominance in the pattern of innervation) nor was there any difference in neuronal size between tracheal and esophageal neurons (91.3 ± 8.6 and 88.6 ± 11.2 μm, respectively). Dual simultaneous retrograde neuronal tracing from the trachea and esophagus using cholera toxin B conjugated to different fluorophores revealed very few (5.0 ± 1.4%, n = 4 experiments) double labeled neurons in the rostral nAmb neuron pool, suggesting that distinct nAmb neurons project to the trachea and esophagus (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Representative photomicrographs showing the organization of cholinergic and retrogradely labeled neurons in the guinea pig nucleus ambiguus (nAmb). (A) Line drawing and (A′) choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) immunostained coronal hemisections of the guinea pig brainstem showing the nAmb and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (dmnX) at 1 mm caudal (upper panel) and 1 mm rostral (lower panel) to the Obex. (B) Higher power magnification of the ChAT immunoreactive neurons in the caudal loose formation and rostral compact formation of the nAmb. (C) Photographic montage showing neurons in the caudal nAmb and their associated axonal projections fluorescently labeled following the application of DiI to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. XII, hypoglossal nucleus; cc, central canal. Co-ordinates indicate the rostral (positive) and caudal (negative) level of the brainstem section relative to the Obex. Scale bars equal 500 μm in (A) and 100 μm in (B,C).

Figure 2.

Caudal to rostral distribution of retrogradely traced neurons in the guinea pig nucleus ambiguus (nAmb). Neurons were traced by administering 2% DiI (A) unilaterally to the mid cervical recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN), (B) unilaterally to the RLN at its termination at the base of the larynx (C) to the tracheal adventitia or (D) to the cervical esophageal muscle layers. The distribution co-ordinates show the caudal (negative) and rostral (positive) location relative to the Obex (0). Note, in (A,B), no traced neurons were identified in the contralateral nAmb. Data are the mean ± sem of 3–4 experiments. See text for further details.

Figure 3.

(A) Representative photomicrograph showing dual retrograde labeling of neurons in the guinea pig nucleus ambiguus (nAmb) following administration of different fluorophore-conjugated cholera toxin B (CTb) subunits to the trachea (red) and esophagus (green). (B) Bar chart displaying the cumulative number of single or double retrogradely labeled neurons in the nAmb (n = 4 experiments). The scale bar in (A) represents 50 μm.

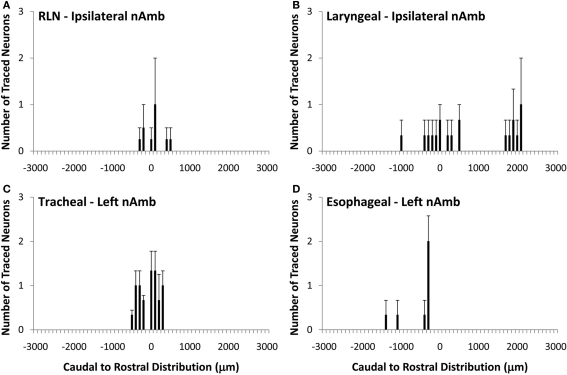

Organization of vagal motor neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve

Unlike the nAmb, very few neurons were retrogradely labeled in dmnX from any of the DiI injection sites (Figure 4). For example, whereas tracing from the cervical RLN in four experiments labeled a total of 1028 neurons in the ipsilateral nAmb, only 12 neurons were labeled in the ipsilateral dmnX in these same experiments. When identified, DiI labeled neurons in the dmnX were small (56–80 μm in perimeter) and showed no injection site specific rostrocaudal organization (Figure 4). There was also no evidence of double labeling of dmnX neurons following dual retrograde tracing from the trachea and esophagus (not shown).

Figure 4.

Caudal to rostral distribution of retrogradely traced neurons in the guinea pig dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (dmnX). Neurons were traced by administering 2% DiI (A) unilaterally to the mid cervical recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN), (B) unilaterally to the RLN at its termination at the base of the larynx (C) to the tracheal adventitia or (D) to the cervical esophageal muscle layers. The distribution co-ordinates represent the caudal (negative) and rostral (positive) location relative to the Obex (0). Note, in (A,B), no traced neurons were identified in the contralateral dmnX. Also note that whilst only the left dmnX is shown in (C,D), labeling was bilateral with a similar distribution density and location. Data are the mean ± sem of 3–4 experiments. See text for further details.

Immunohistochemical characterization of retrogradely traced tracheal and esophageal neurons in the nAmb and dmnX

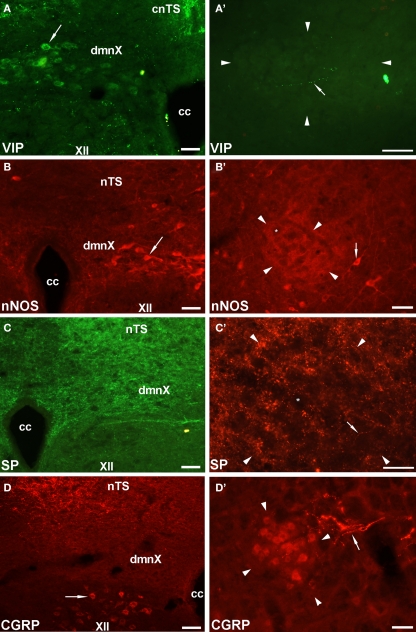

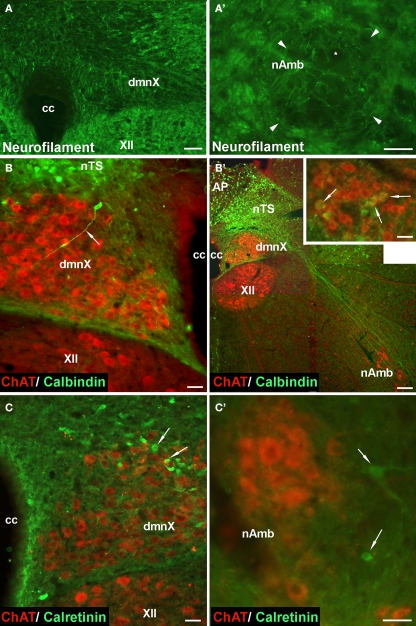

Given that the tracheal and esophageal projecting motor neurons are intermingled in the same pool of neurons in the nAmb and dmnX, we attempted to determine whether distinct neuronal populations could be defined using common immunochemical markers. Neurons in the nAmb that were retrogradely labeled from either the trachea or esophagus were almost all cholinergic (i.e., 98.2 ± 0.9 and 99.4 ± 0.6% ChAT positive, respectively). By contrast, 95.9 ± 3.6% of tracheal neurons and 86.9 ± 6.1% of esophageal neurons in the dmnX expressed detectable ChAT immunoreactivity. None (0 ± 0%) of the esophageal or tracheal projecting neurons in the nAmb or dmnX expressed detectable nNOS, substance P, VIP, neurofilament, calretinin or calbindin immunoreactivity (Figures 5 and 6). However, unidentified nNOS (Figure 5B) and calretinin (Figure 6B′) positive cells were visible in the dmnX and many examples of nerve fibers immunoreactive for each of these markers were clearly visible in both of the vagal motor nuclei (sometimes in close proximity to retrogradely labeled neurons; Figures 5 and 6). VIP positive nerve fibers, but not soma, were infrequently observed in the nAmb (Figure 5A′). VIP positive neurons and fibers were, however, consistently observed in the dmnX (Figure 5A) and although only a small number of traced neurons in the dmnX were assessed (due to the small number identified at this site), approximately 70% were immunoreactive for VIP, regardless of whether they projected to the trachea or esophagus.

Figure 5.

Representative photomicrographs showing the distribution of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), substance P (SP) and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in (A–D) the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (dmnX) and (A′–D′) the rostral nucleus ambiguus (nAmb). (A) VIP positive cells (arrow) were routinely observed in the dmnX. (B) VIP was not detected in nAmb neurons, but on occasion fine varicose VIP positive fibers (arrow) were seen adjacent to nAmb neurons. (B) nNOS was detected in some dmnX neurons (arrow). (B′) No neurons within the nAmb expressed nNOS, although nNOS positive neurons were often observed (arrow) outside the boundary of the rostral nAmb. (C,C′) SP labeling was not seen in any soma in either the dmnX or nAmb, but was expressed by many fine fibers in both nuclei (arrow). (D) CGRP was not expressed in dmnX neurons. Fibers in the adjacent nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS) and cells (arrow) in the hypoglossal nucleus (XII) were intensely CGRP positive. (D′) CGRP expressing neurons were observed in the nAmb as well as some axons in close proximity (arrow). In (A′–D′) the arrow heads delineate the boundary of the nAmb. The asterisks in (B′,C′) show the profile of unstained nAmb neurons. Note that different fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were used, hence the red or green immunostaining. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Cc, central canal; cnTS, commissural nTS.

Figure 6.

Representative photomicrographs showing the distribution of neurofilament, calbindin and calretinin in (A–C) the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (dmnX), and (A′–C′) the nucleus ambiguus (nAmb). (A,A′) No somal immunoreactivity for neurofilament was observed in the dmnX or nAmb. The arrow heads in (A′) delineate the boarder of the nAmb and the asterisk shows the profile of an unstained neuron which is surrounded by fine neurofilament positive fibers. In (B,B′,C,C′) brainstem sections have been counterstained for choline acteyltransferase (ChAT; red) to show the location of cholinergic neurons. (B) A calbindin immunoreactive neuron (ChAT negative) can be seen on the boarder of the nucleus of the solitary tract (nTS) and the dmnX, with its axon (arrow) penetrating deep into the dmnX. No Chat positive neurons in the dmnX expressed calbindin. (B′) Photographic montage showing calbinidin immunoreactive axons arising from nTS neurons projecting in the direction of the nAmb. Inset shows rostral nAmb neurons, several of which (arrows) are immunopositive for both ChAT and calbindin. No retrogradely traced nAmb neurons were calbindin positive (see text). (C) Several calretinin positive, ChAT negative neurons (arrows) can be seen within the dmnX. ChAT positive neurons within the dmnX are densely surrounded by calretinin immunoreactivity. (C′) Several calretinin positive neurons (arrows) can be seen outside of the boundary of the nAmb. No ChAT positive nAmb neurons expressed calretinin. The scale bars represent 50 μm except in (B′) where it represents 100 μm.

Immunoreactivity for CGRP appeared to distinguish between tracheal and esophageal traced neurons in the rostral nAmb (Figure 7). For example, although 39.1 ± 2.3% (303 out of 795 neurons counted) of the entire population of ChAT positive rostral nAmb neurons expressed CGRP, 77.9 ± 4.1% of the esophageal traced neurons compared to 21.5 ± 4.9% of the tracheal traced neurons were CGRP positive (P < 0.05; Figure 7D′). No cholinergic neurons in the dmnX (0 out of 1997 neurons counted), nor any traced neurons at this site were CGRP positive (Figures 5D and 7A,D). However, many neurons (presumably motor neurons) in the hypoglossal nucleus, caudal (laryngeal) nAmb and facial nucleus expressed CGRP (see Figures 5D and 7A–C) for example of CGRP expression in the hypoglossal nucleus).

Figure 7.

Analysis of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) expression in (A–D) the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (dmnX) and (A′–D′) the nucleus ambiguus (nAmb). (A,A′) Representative photomicrographs showing the distribution of CGRP (green) and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT; red) in the caudal dmnX and the rostral nAmb. No dmnX neurons expressed CGRP whereas a subpopulation of ChAT positive nAmb neurons expressed CGRP. (B,B′ and C,C′) show representative photomicrographs of the distribution of CGRP (red) in tracheal or esophageal neurons retrogradely labeled with cholera toxin B (green) in the dmnX and nAmb. No CTb labeled neurons in the dmnX (arrow heads) expressed CGRP. Some CTb labeled neurons in the nAmb (arrows) expressed CGRP (double labeled neurons appear yellow). (D,D′) Bar charts showing quantitative analysis of ChAT and CGRP expression in the general population of ChAT positive dmnX or nAmb neurons versus neurons retrogradely traced from either the trachea or esophagus. *P < 0.05 significantly less than the general population. *P < 0.05 significantly greater than the general population. The scale bars represent 100 μm. cc, central canal; nTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; XII, hypoglossal nucleus.

Functional studies

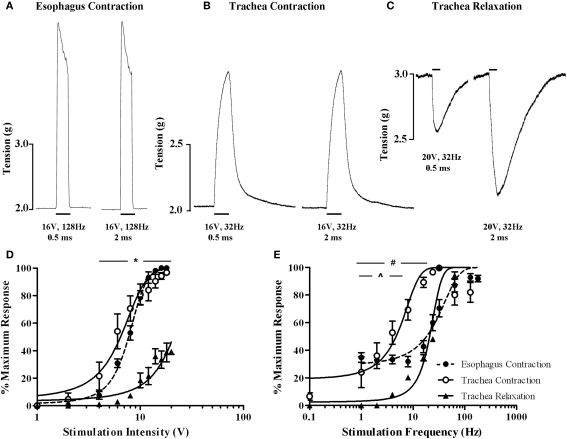

Electrical stimulation of the vagi, performed in the presence of 5 μM capsaicin in an attempt to prevent any contribution of antidromically activated vagal C-fibers, evoked both voltage and frequency dependent responses in the isolated innervated in vitro tracheal and esophageal preparations (Figure 8). End organ responses (esophageal contractions, tracheal contractions, and tracheal relaxations) differed in kinetics as well as voltage and frequency sensitivities. For example, tracheal contractions and tracheal relaxations were slow in onset, peaking after approximately 10 s of stimulation, whereas esophageal contractions peaked in less than 1 s and were not sustained with continued stimulation (Figures 8A–C). At optimum stimulating frequencies, tracheal contractions, and esophageal contractions were evoked at similar voltage thresholds (2–4 V) and displayed comparable EV50s (6.4 ± 0.4 and 7.7 ± 0.3 V, respectively; Figure 8D). By contrast, the voltage threshold for tracheal relaxations was significantly (P < 0.05) higher (8–10 V) and failed to reach 50% of the maximum attainable response at maximum stimulating voltages when using 0.5 ms pulses (Figure 8D). Indeed, whilst pulse durations of 0.5 ms were optimal for evoking maximum tracheal and esophageal contractions, maximum vagus nerve evoked tracheal relaxations at pulse durations of 0.5 ms were only 39.3 ± 1.9% of those evoked at 2 ms pulse durations (Figures 8A–C).

Figure 8.

In vitro functional characterization of vagal efferent neurons innervating the guinea pig trachea and esophagus. Representative recordings of vagus nerve stimulation-evoked (A) esophageal contraction, (B) tracheal contraction, and (C) tracheal relaxation. Note that increasing the stimulus pulse duration from 0.5 to 2 ms did not affect either esophageal or tracheal contractions, but dramatically enhanced the magnitude of tracheal relaxations. Scale bars represent 1 s in (A) and 10 s in (B,C). (D,E) show mean ± sem log stimulation dependent vagally mediated responses. In (D), stimulation frequency was optimal for each preparation and pulse duration was set at 0.5 ms. In (E), stimulation voltage was optimal for each preparation and pulse duration was set at either 0.5 ms for esophageal and tracheal contractions or 2 ms for tracheal relaxations (as 0.5 ms was insufficient to generate consistent frequency dependent responses). Each data point represents the peak percentage response at a given stimulus relative to the absolute maximal attainable response irrespective of stimulus parameters. *Peak tracheal relaxations P < 0.05) significantly different to peak tracheal and esophageal contractions. #Peak tracheal relaxations significantly (P < 0.05) different to peak tracheal contractions. ^Peak tracheal relaxations significantly (P < 0.05) different to peak esophageal contractions. See text for calculated voltage and frequency comparisons.

At optimum stimulating voltages, esophageal twitches of sizeable magnitude (approximately 40% of the maximum attainable vagus nerve evoked response) were produced at 1 Hz (i.e., a single pulse in the 1 s stimulation period; Figure 8E). Increasing pulse frequency initially evoked a comparable increase in the number of esophageal twitches, each of a similar magnitude. Individual twitches began to summate at approximately 16 Hz and maximal responses (peaking at 128 Hz) could be maintained at frequencies of upto 180 Hz (EF50 = 18.2 ± 1.6 Hz). By comparison, whilst the frequency threshold for tracheal contractions was approximately 0.1 Hz (i.e., one pulse in 10 s), the magnitude of such contractions were on average approximately 6% of the maximum. Tracheal smooth muscle contractions summated with each successive increase in stimulation frequency but peaked at 32 Hz (EF50 = 4.7 ± 0.7 Hz). Further increases in the frequency of stimulation resulted in a notable reduction in the maximum response (Figure 8E). Stimulation frequencies of less than 24 Hz with 0.5 ms pulse durations failed to evoke tracheal relaxant responses and were not studied further. At 2 ms pulse durations, the threshold for tracheal relaxant responses was approximately 4 Hz and again responses peaked at 32 Hz (EF50 = 20.1 ± 1.3 Hz; Figure 8E).

Pretreatment with the CGRP1 receptor antagonist (CGRP8–37) produced no discernable effects on vagally evoked esophageal contractions at any voltages or frequencies of stimulation studied (EV50 and EF50 values in the presence of CGRP8–37 were 8.1 ± 0.6 volts and 18.6 ± 2.1 Hz, respectively).

Discussion

We set out to test the hypothesis that anatomically and functionally distinct preganglionic neurons regulate contractile and relaxant postganglionic responses in the guinea pig airways. Our data indicate that airway contractions, airway relaxations, and esophageal contractions all depend upon distinct vagal motor neurons. However, anatomically these neurons are difficult to distinguish as they are intermingled within a common region of the nAmb. The expression of CGRP likely defines esophageal skeletal motor neurons, whereas preganglionic neurons mediating airway contractile and relaxant responses at present remain distinguishable only by function.

Location and phenotype of brainstem airway and esophageal neurons

The brainstem origin of the vagal inputs to the airways has been mapped in a variety of species (Haxhiu and Loewy, 1996; Pérez Fontán and Velloff, 1997; Kc et al., 2004; Atoji et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2006; Mazzone and McGovern, 2010). However there have been no attempts to differentiate the origins of preganglionic neurons that regulate airway smooth muscle contractions versus those that mediate relaxations. This may in part reflect the reported absence of a vagal relaxant pathway in muriform rodents (Manzini, 1992; Szarek et al., 1995). It may also reflect a difficulty in separating these circuits due to the intimate anatomical organization of contractile and relaxant postganglionic neurons in most species. In guinea pigs, however, the anatomical segregation of the contractile and relaxant postganglionic neurons provides an opportunity to study these pathways independent of each other.

Motor neurons projecting to the larynx were distinguished by their location in the caudal nAmb and larger somal size. By contrast, the vagal neurons projecting to the trachea and esophagus (which include airway contractile and relaxant preganglionic and esophageal motor neurons) were intermingled in the rostral nAmb. The peak location of these neurons (1.5–2 mm rostral to the Obex) is in agreement with previous tracing studies in other species (Haxhiu and Loewy, 1996; Kc et al., 2004; Atoji et al., 2005; Mazzone and McGovern, 2010) and a prior functional study in guinea pigs in which baseline cholinergic drive to the airways was abolished following microinjection of ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists into the nAmb at this site (Mazzone and Canning, 2002d). Although we were unable to demonstrate any topographical organization or somal size differences between tracheal and esophageal projecting neurons, dual tracing studies showed that distinct neurons amongst this intermingled population project to these two tissues.

All retrogradely labeled neurons in the nAmb expressed ChAT, confirming that the non-cholinergic phenotype of the airway relaxant pathway is confined to the postganglionic innervation. Indeed, in guinea pigs anti-cholinergic ganglion blockers abolish vagally mediated airway contractions and relaxations (Canning and Undem, 1993) and skeletal neuromuscular blockers inhibit esophageal contractions (Kerr, 2002). Our attempts to classify traced neuron subpopulations, using markers commonly employed to categorize other autonomic neurons, were largely unsuccessful. Neurons in the nAmb (retrogradely traced or not) did not express calcium binding proteins calbindin or calretinin, the neurotransmitters substance P, VIP or nitric oxide, or the cytoskeletal protein neurofilament.

CGRP, however, was expressed in a subpopulation of cholinergic neurons in the nAmb, predominately those retrogradely traced from the esophagus. Esophageal motor neurons in rats express CGRP, as do other skeletal muscle motor neurons (Lee et al., 1992; Kuramoto et al., 1996; Wörl et al., 1997; González-Forero et al., 2002; Grkovic et al., 2005). In agreement, we noted CGRP in cholinergic neurons in the hypoglossal, laryngeal nAmb and facial nuclei, but not in the dmnX. CGRP may play a role in the regulation of skeletal muscle EC coupling or the expression of acetylcholinesterase and/or cholinergic receptors (Buffelli et al., 2001; Rossi et al., 2003; Avila et al., 2007). In our studies vagally mediated esophageal contractions were unaffected by CGRP(8–37) (at a concentration that blocks CGRP mediated effects in other systems; Kajekar and Myers, 2008). Interestingly, CGRP is not contained in nerve terminals innervating esophageal motor end plates in guinea pigs (Kuramoto et al., 1996). We have noted (unpublished observations) that CGRP immunoreactive nerve fibers in the guinea pig esophagus are fine and varicose in appearance and absent after acute capsaicin treatment, suggesting that they are derived from a sensory origin. Thus at present the role for CGRP in esophageal neurons is unclear. It is worth noting that not all esophageal neurons expressed CGRP. Given the selectivity of CGRP for skeletal motor neurons, CGRP negative neurons may represent the putative relaxant preganglionic neuron subpopulation within the nAmb. However, this has to be reconciled with the fact that a small number of tracheal projecting neurons also expressed CGRP.

In contrast to the substantial projection of rostral nAmb neurons, our studies show that few motor neurons arising from the dmnX contribute to the vagal outflow to the cervical trachea and esophagus in guinea pigs. Retrogradely traced neurons in the dmnX were smaller in size than those in the nAmb, displayed no rostrocaudal organization, and were not always immunoreactive for ChAT. We had speculated at the outset of this study that the airway relaxant preganglionic neurons may originate in the dmnX as the cardiac and pulmonary dmnX motor neurons in cats conduct action potentials in the C-fiber range (Ford et al., 1990; Jones et al., 1998). However this seems unlikely given our data. Neurons in the dmnX may control lower esophageal sphincter tone (Rossiter et al., 1990; McDermott et al., 2001; Niedringhaus et al., 2008) but these neurons would not have been included in our tracing studies.

Functionally distinct vagal pathways regulate airway and esophageal muscle

In cats and guinea pigs the vagal projections to the airways and lungs are comprised of both myelinated and unmyelinated efferent axons, the latter of which may preferentially mediate non-cholinergic parasympathetic evoked bronchodilation (McAllen and Spyer, 1978; Lama et al., 1988; Canning and Undem, 1993). Furthermore, in anesthetized guinea pigs hypoxia or stimulation of the diving response (nasal submersion in cold water) reflexly increases cholinergic outflow to the airways without affecting non-cholinergic neurons (Mazzone and Canning, 2002b). By contrast, stimuli that excite airway and laryngeal nociceptors, rapidly adapting receptors and gastrointestinal afferents activate both the cholinergic and non-cholinergic pathways (Kesler et al., 2002; Mazzone and Canning, 2002b, c, d). This differentiation between stimuli that precipitate reflex-mediated airway contractions and relaxations presumably necessitates distinct vagal outflows from the brainstem.

Our data show that the electrical sensitivity of the vagal neurons that drive tracheal and esophageal contractions are comparable, whereas the preganglionic neurons responsible for evoking airway relaxations require significantly higher stimulation intensities (and longer pulse durations) to evoke measurable responses. This separation of electrical sensitivities would argue in favor of myelinated inputs to contractile neurons and unmyelinated inputs to relaxant neurons (Lama et al., 1988; Canning and Undem, 1993). It would also suggest that different efferent neuron populations are responsible for neuromuscular versus ganglionic transmission in the esophagus. The vastly different frequency-dependency of vagally mediated responses are also suggestive that three distinct vagal pathways control the end organ effects measured in the present study, however postsynaptic receptor or signaling mechanisms and/or ganglionic filtering effects could equally account for these latter observations.

Conclusion

These data indicate that the anatomically distinct parasympathetic postganglionic neurons which mediate airway contractions and relaxations in guinea pigs are in turn innervated by distinct preganglionic neurons. This complete segregation of contractile and relaxant pathways innervating the airways is in contrast to other viscera (for example the lower urinary tract) where effects are mediated by differential tissue responsiveness to contractile and relaxant neurotransmitters which are colocalized and released from common parasympathetic neurons. Furthermore, the relaxant postganglionic neurons that reside in the esophagus in guinea pigs are not regulated by esophageal motor neurons, but rather possess efferent inputs that are distinguishable by physiology and perhaps neurochemistry.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

These studies were funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia, grants 350333 and 566734. Stuart B. Mazzone holds an NHMRC of Australia Fellowship grant (454776).

References

- Atoji Y., Kusindarta D. L., Hamazaki N., Kaneko A. (2005). Innervation of the rat trachea by bilateral cholinergic projections from the nucleus ambiguus and direct motor fibers from the cervical spinal cord: a retrograde and anterograde tracer study. Brain Res. 1031, 90–100 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila G., Aguilar C. I., Ramos-Mondragón R. (2007). Sustained CGRP1 receptor stimulation modulates development of EC coupling by cAMP/PKA signalling pathway in mouse skeletal myotubes. J. Physiol. 584 (Pt 1), 47–57 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BaŁuk P., Gabella G. (1989). Innervation of the guinea pig trachea: a quantitative morphological study of intrinsic neurons and extrinsic nerves. J. Comp. Neurol. 285, 117–132 10.1002/cne.902850110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffelli M., Pasino E., Cangiano A. (2001). In vivo acetylcholine receptor expression induced by calcitonin gene-related peptide in rat soleus muscle. Neuroscience 104, 561–567 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00090-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning B. J., Undem B. J. (1993). Evidence that distinct neural pathways mediate parasympathetic contractions and relaxations of guinea-pig trachealis. J. Physiol. 471, 25–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Li M., Liu H., Wang J. (2006). The airway-related parasympathetic motoneurons in the ventrolateral medulla of newborn rats were dissociated anatomically and in functional control. Exp. Physiol. 92, 99–108 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.036079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A., Canning B. J., Undem B. J., Kummer W. (1998). Evidence for an esophageal origin of VIP-IR and NO synthase-IR nerves innervating the guinea pig trachealis: a retrograde neuronal tracing and immunohistochemical analysis. J. Comp. Neurol. 394, 326–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford T. W., Bennett J. A., Kidd C., McWilliam P. N. (1990). Neurones in the dorsal motor vagal nucleus of the cat with non-myelinated axons projecting to the heart and lungs. Exp. Physiol. 75, 459–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Forero D., De La Cruz R. R., Delgado-García J. M., Alvarez F. J., Pastor A. M. (2002). Correlation between CGRP immunoreactivity and firing activity in cat abducens motoneurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 451, 201–212 10.1002/cne.10267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grkovic I., Fernandez K., McAllen R. M., Anderson C. R. (2005). Misidentification of cardiac vagal pre-ganglionic neurons after injections of retrograde tracer into the pericardial space in the rat. Cell Tissue Res. 321, 335–340 10.1007/s00441-005-1145-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. F., Wang Y., Jordan D. (1998). Activity of C fibre cardiac vagal efferents in anaesthetized cats and rats. J. Physiol. 507 (Pt 3), 869–880 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.869bs.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxhiu M. A., Loewy A. D. (1996). Central connections of the motor and sensory vagal systems innervating the trachea. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 57, 49–56 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajekar R., Myers A. C. (2008). Calcitonin gene-related peptide affects synaptic and membrane properties of bronchial parasympathetic neurons. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 160, 28–36 10.1016/j.resp.2007.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kc P., Mayer C. A., Haxhiu M. A. (2004). Chemical profile of vagal preganglionic motor cells innervating the airways in ferrets: the absence of noncholinergic neurons. J. Appl. Physiol. 97, 1508–1517 10.1152/japplphysiol.00282.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr K. P. (2002). The guinea-pig oesophagus is a versatile in vitro preparation for pharmacological studies. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 29, 1047–1054 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesler B. S., Mazzone S. B., Canning B. J. (2002). Nitric oxide-dependent modulation of smooth-muscle tone by airway parasympathetic nerves. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165, 481–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto H., Kato Y., Sakamoto H., Endo Y. (1996). Galanin-containing nerve terminals that are involved in a dual innervation of the striated muscles of the rat esophagus. Brain Res. 734, 186–192 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00639-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lama A., Delpierre S., Jammes Y. (1988). The effects of electrical stimulation of myelinated and non-myelinated vagal motor fibres on airway tone in the rabbit and the cat. Respir. Physiol. 74, 265–274 10.1016/0034-5687(88)90035-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. H., Lynn R. B., Lee H. S., Miselis R. R., Altschuler S. M. (1992). Calcitonin gene-related peptide in nucleus ambiguus motoneurons in rat: viscerotopic organization. J. Comp. Neurol. 320, 531–543 10.1002/cne.903200410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzini S. (1992). Bronchodilatation by tachykinins and capsaicin in the mouse main bronchus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 105, 968–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone S. B., Canning B. J. (2002a). Central nervous system control of the airways: pharmacological implications. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2, 220–228 10.1016/S1471-4892(02)00151-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone S. B., Canning B. J. (2002b). Evidence for differential reflex regulation of cholinergic and noncholinergic parasympathetic nerves innervating the airways. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165, 1076–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone S. B., Canning B. J. (2002c). Synergistic interactions between airway afferent nerve subtypes mediating reflex bronchospasm in guinea pigs. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 283, R86–R98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone S. B., Canning B. J. (2002d). An in vivo guinea pig preparation for studying the autonomic regulation of airway smooth muscle tone. Auton. Neurosci. 99, 91–101 10.1016/S1566-0702(02)00053-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone S. B., McGovern A. E. (2006). Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporters and Cl− channels regulate citric acid cough in guinea pigs. J. Appl. Physiol. 101, 635–643 10.1152/japplphysiol.00106.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone S. B., McGovern A. E. (2008). Immunohistochemical characterization of nodose cough receptor neurons projecting to the trachea of guinea pigs. Cough 4, 9. 10.1186/1745-9974-4-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone S. B., McGovern A. E. (2010). Innervation of tracheal parasympathetic ganglia by esophageal cholinergic neurons: evidence from anatomic and functional studies in guinea pigs. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 298, L404–L416 10.1152/ajplung.00166.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllen R. M., Spyer K. M. (1978). Two types of vagal preganglionic motoneurones projecting to the heart and lungs. J. Physiol. 282, 353–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott C. M., Abrahams T. P., Partosoedarso E., Hyland N., Ekstrand J., Monroe M., Hornby P. J. (2001). Site of action of GABA(B) receptor for vagal motor control of the lower esophageal sphincter in ferrets and rats. Gastroenterology 120, 1749–1762 10.1053/gast.2001.24849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A. C. (2000). Anatomical characteristics of tonic and phasic postganglionic neurons in guinea pig bronchial parasympathetic ganglia. J. Comp. Neurol. 419, 439–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedringhaus M., Jackson P. G., Evans S. R., Verbalis J. G., Gillis R. A., Sahibzada N. (2008). Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus: a site for evoking simultaneous changes in crural diaphragm activity, lower esophageal sphincter pressure, and fundus tone. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 294, R121–R131 10.1152/ajpregu.00391.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Fontán J. J., Velloff C. R. (1997). Neuroanatomical organisation of the parasympathetic bronchomotor system in developing sheep. Am. J. Physiol. 273 (Pt 2), R121–R133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S. G., Dickerson I. M., Rotundo R. L. (2003). Localization of the calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor complex at the vertebrate neuromuscular junction and its role in regulating acetylcholinesterase expression. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24994–25000 10.1074/jbc.M211379200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter C. D., Norman W. P., Jain M., Hornby P. J., Benjamin S., Gillis R. A. (1990). Control of lower esophageal sphincter pressure by two sites in dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Am. J. Physiol. 259, G899–G906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szarek J. L., Stewart N. L., Spurlock B., Schneider C. (1995). Sensory nerve–and neuropeptide-mediated relaxation responses in airways of Sprague–Dawley rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 78, 1679–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wörl J., Mayer B., Neuhuber W. L. (1997). Spatial relationships of enteric nerve fibers to vagal motor terminals and the sarcolemma in motor endplates of the rat esophagus: a confocal laser scanning and electron-microscopic study. Cell Tissue Res. 287, 113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]