Abstract

While it has long been known that the reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide (NO) forms iron-nitrosyl-myoglobin and is the basis of meat curing, a greater biological activity of the nitrite anion has only recently been appreciated. In the stomach, NO is formed from acidic reduction of nitrite and increases mucous barrier thickness and gastric blood flow (see the related study beginning on page 106). Nitrite levels in blood reflect NO production from endothelial NO synthase enzymes, and recent data suggest that nitrite contributes to blood flow regulation by reaction with deoxygenated hemoglobin and tissue heme proteins to form NO.

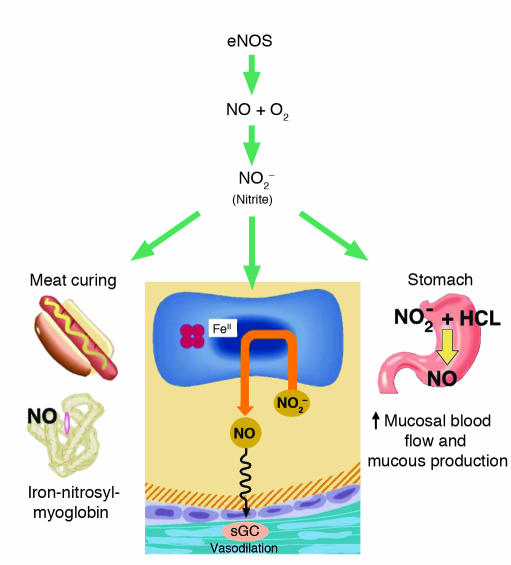

The identification of nitrite (NO2–) as the active ingredient in red meat–curing procedures dates to the late 19th century. J.S. Haldane, father of J.B.S. Haldane and famous for the description of the “Haldane effect,” whereby hemoglobin’s affinity for carbon dioxide is reduced by oxygen binding and vice versa, was the first to demonstrate that the addition of nitrite to hemoglobin produced a nitric oxide (NO)-heme bond, called iron-nitrosyl-hemoglobin (HbFeIINO). Hoagland confirmed this and suggested that the reduction of nitrite to NO by bacteria or enzymatic reactions in the presence of muscle myoglobin formed iron-nitrosyl-myoglobin (1). It is nitrosylated myoglobin that gives cured meat, including hot dogs, their distinctive red color, and protects the meat from oxidation and spoiling (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The broad biological activity of the nitrite anion. Nitrite levels in blood reflect NO production from endothelial NO synthase enzymes. Furthermore, nitrite contributes to blood flow regulation by reaction with deoxygenated hemoglobin and tissue heme proteins to form NO. In the stomach, NO is formed from acidic reduction of nitrite and increases mucous barrier thickness and gastric blood flow. Finally, the reaction of nitrite to form NO and iron-nitrosyl-myoglobin forms the basis of meat curing. sGC, soluble guanylyl cyclase.

Nitrate reductase activity of saliva

In the first half of this century scientists discovered that saliva contains high levels of both nitrite and nitrate (NO3–). Studies of 15NO3– ingestion in rats and humans suggest that an oral nitrate load is absorbed in the upper small intestine, after which 70% is excreted in the kidney and 25% is actively concentrated into saliva at tenfold its levels in plasma (recently reviewed by Duncan et al. in ref. 2). One and a half liters of saliva bathes the tongue daily, and salivary nitrate is rapidly reduced to nitrite by the nitrate reductase enzyme systems of commensal bacteria living in the posterior tongue epithelial clefts. In the current issue of the JCI, Björne and colleagues (3) measured salivary nitrite levels of fasting individuals and again after an oral nitrate load. The levels of salivary nitrite in fasting individuals were approximately 43 μM and increased to 2 mM after an oral nitrate load. This corresponds to the active reduction of approximately 20% of salivary nitrate to nitrite. The bacteria-derived nitrate reductase activity of human saliva can be inhibited by short courses of antibiotics (4), oral antiseptic mouthwashes (5), and filtering of saliva to remove bacteria (6).

Nitrite acidification in the stomach generates gastroprotective NO

Acidified nitrite in the stomach can nitrosate thiols, forming S-nitrosothiols, and nitrosate amines, forming N-nitrosamines, but in the presence of electron donors such as ascorbate or excess nitrite, the acidified nitrite largely generates NO gas (7–9). NO appears to play an important role in gastric mucosal defence, increasing mucosal blood flow and increasing mucous production (10, 11, and recently reviewed in ref. 12). It is this protective effect of NO that forms the rationale for ongoing clinical trials of novel aspirin–NO donor agents, designed to limit gastric and duodenal ulceration associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In addition to the effects of NO on mucosal integrity, acidified nitrite has bacteriocidal activity against Yersina, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli bacterial species (2). The lack of oral bacterial flora in newborns may be counterbalanced by the presence of xanthine oxido-reductase in breast milk, a human enzyme homologous to bacterial nitrate reductase, which has been shown to reduce nitrate and nitrite to NO (13–15) It should be noted that the gastroprotective effects of nitrite appear to outweigh the theoretical risk of nitrosamine carcinogenesis, a risk that has not been substantiated by numerous epidemiological studies (16–18).

The current study by Björne and colleagues (3) extends and synthesizes these disparate studies, elegantly showing that human saliva, after an oral nitrate load equivalent to 150–300 grams of spinach, contains micromolar concentrations of nitrite. The addition of human saliva to rat stomach mucosal preparations (treated with HCl or pentagastrin) induced the production of NO gas and S-nitrosothiol and increased both mucosal blood flow and mucous thickness. These effects were reproduced following direct administration of nitrite itself or the NO donor sodium nitroprusside and were dependent on the activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Production of gastric NO was also observed 2 hours after the in vivo treatment of rats with an oral nitrate load. The novelty of this work rests on the use of human saliva as the “NO donor agent” and documentation of a potent effect of this substrate on mucosal blood flow and mucous production.

Nitrite as a biomarker of endothelial NO synthase activity

These data are consistent with an expanding appreciation of the role of nitrite in physiology and global blood flow regulation. In human plasma, low levels of nitrite are formed from the auto-oxidation of NO, which is produced by endothelial NO synthase:

Reaction 1

2NO + O2 → 2NO2

Reaction 2

NO + NO2 → N2O3 → NO2– + NO+ (NO+ can form S-nitrosothiols and N-nitrosamines)

The relative stability of nitrite, compared with that of NO itself, has resulted in reported mammalian plasma nitrite levels ranging from 150 nM to 1 μM (19–21). However, nitrite is oxidized to nitrate by a reaction with oxyhemoglobin with a half-life of approximately 11 minutes. Thus, in order to measure physiological nitrite levels, plasma must be separated from erythrocytes immediately after blood sampling. Therefore, the relative stability of nitrite compared with that of NO and the elimination of nitrite by chemical reaction with hemoglobin create a species that can serve as a marker of acute NO synthase activity. Kelm and colleagues have demonstrated that nitrite levels present in venous blood reflect acute changes in NO synthase activity during both activation and inhibition, and plasma levels of nitrite are reduced by 70% in both endothelial NO synthase knockout mice and mice treated with the NO synthase inhibitor nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (known as L-NAME) (22, 23). Nitrate, on the other hand, has a relatively long half-life and is excreted mainly by the kidneys, and its levels are affected by both renal function and diet, confounding its use as a biomarker of NO production.

Nitrite as a vasodilator

Nitrite has been traditionally considered an end-product metabolite of NO reactions with oxygen and without intrinsic vasodilatory activity. However, recent studies from our group have revealed a striking effect of nitrite infusions on forearm and systemic blood flow (24). We infused supraphysiological (200 μM forearm vein nitrite concentrations) and near-physiological (2 μM) concentrations of sodium nitrite into the brachial arteries of 28 normal human volunteers. Blood flow significantly increased in all subjects and was associated with the formation of NO-modified hemoglobin (iron-nitrosyl-hemoglobin and, to a lesser extent, S-nitroso-hemoglobin). The formation of NO-modified hemoglobin was inversely correlated with hemoglobin oxygen saturation, consistent with a reaction of nitrite with deoxyhemoglobin to produce NO. These results were recapitulated in aortic ring preparations, in which the addition of nitrite to deoxyhemoglobin and deoxygenated erythrocytes resulted in vessel relaxation. This observation can be explained by a reaction between nitrite and deoxyhemoglobin to form NO, a chemical reaction first described in 1981 by Doyle and colleagues (25), and supports the idea of a novel function for nitrite in the regulation of hypoxic vasodilation.

Reaction 3

NO2– + HbFeII (deoxyhemoglobin) + H+ → HbFeIII (methemoglobin) + NO + OH–

Reaction 4

NO + HbFeII → HbFeIINO

Nitrite therapeutics?

Our new understanding of the role of nitrite in the physiological regulation of gastric barrier integrity and hypoxic vasodilation presents novel therapeutic opportunities. Can oral nitrite be administered for gastric ulcer prophylaxis to endotracheally intubated critically ill patients, thus obviating the need for acid-suppressive therapies that increase the risk of nosocomial pneumonia? Can nitrite infusions be used for selective NO delivery to ischemic sites at high risk for ischemia-reperfusion injury, such as cardiac and limb tissue after revascularization procedures? Nitrite infusions seem ideally suited for the treatment of hemolytic conditions associated with scavenging of NO by cell-free plasma hemoglobin, such as sickle cell disease or cardiopulmonary bypass (26). While powders of nitrite salts are present on almost every laboratory bench in the world, and nitrite anion preparations are currently available for human infusion in cyanide antidote kits, further clinical work is needed to address the safety and efficacy of this agent for the treatment of specific human diseases. At the very least, perhaps we should avoid mouthwash and feel slightly less guilty about eating hot dogs at the ball park.

Footnotes

See the related article beginning on page 106.

Conflict of interest: The author has declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: nitrite (NO2–); iron-nitrosyl-hemoglobin (HbFeIINO); nitrate (NO3–); deoxyhemoglobin (HbFeII).

References

- 1.Pegg, R.B., and Shahidi, F. 2000. Nitrite Curing of Meat. Food & Nutrition Press. Trumbull, Connecticut, USA. 268 pp.

- 2.Duncan C, et al. Protection against oral and gastrointestinal diseases: importance of dietary nitrate intake, oral nitrate reduction and enterosalivary nitrate circulation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 1997;118:939–948. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(97)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Björne H, et al. Nitrite in saliva increases gastric mucosal blood flow and mucus thickness. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:106–114. doi:10.1172/JCI200419019. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dougall HT, Smith L, Duncan C, Benjamin N. The effect of amoxycillin on salivary nitrite concentrations: an important mechanism of adverse reactions? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1995;39:460–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb04479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tannenbaum SR, Weisman M, Fett D. The effect of nitrate intake on nitrite formation in human saliva. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1976;14:549–552. doi: 10.1016/s0015-6264(76)80006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishiwata H, Boriboon P, Harada M, Tanimura A, Ishidata M. Changes of nitrite and nitrate concentration in incubated human saliva. J. Food Hyg. Soc. Jpn. 1975;16:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin N, et al. Stomach NO synthesis. Nature. 1994;368:502. doi: 10.1038/368502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKnight GM, et al. Chemical synthesis of nitric oxide in the stomach from dietary nitrate in humans. Gut. 1997;40:211–214. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundberg JON, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JM, Alving K. Intragastric nitric oxide production in humans: measurements in expelled air. Gut. 1994;35:1543–1546. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.11.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pique JM, Whittle BJ, Esplugues JV. The vasodilator role of endogenous nitric oxide in the rat gastric microcirculation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;174:293–296. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JF, Hanson PJ, Whittle BJR. Nitric oxide donors increase mucus gel thickness in rat stomach. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;223:103–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90824-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace JL, Miller MJ. Nitric oxide in mucosal defense: a little goes a long way. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:512–520. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, et al. Human xanthine oxidase converts nitrite ions into nitric oxide (NO) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1997;25:524S. doi: 10.1042/bst025524s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millar TM, et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase catalyses the reduction of nitrates and nitrite to nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions. FEBS Lett. 1998;427:225–228. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Samouilov A, Liu X, Zweier JL. Characterization of the magnitude and kinetics of xanthine oxidase-catalyzed nitrate reduction: evaluation of its role in nitrite and nitric oxide generation in anoxic tissues. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1150–1159. doi: 10.1021/bi026385a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forman D, Al-Dabbagh S, Doll R. Nitrates, nitrites and gastric cancer in Great Britain. Nature. 1985;313:620–625. doi: 10.1038/313620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pobel D, Riboli E, Cornee J, Hemon B, Guyader M. Nitrosamine, nitrate and nitrite in relation to gastric cancer: a case-control study in Marseille, France. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1995;11:67–73. doi: 10.1007/BF01719947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez CA, et al. Nutritional factors and gastric cancer in Spain. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1994;139:466–473. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gladwin MT, et al. Role of circulating nitrite and S-nitrosohemoglobin in the regulation of regional blood flow in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:11482–11487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rassaf T, et al. NO adducts in mammalian red blood cells: too much or too little? Nat. Med. 2003;9:481–483. doi: 10.1038/nm0503-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez J, Maloney RE, Rassaf T, Bryan NS, Feelisch M. Chemical nature of nitric oxide storage forms in rat vascular tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:336–341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0234600100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelm M, Preik-Steinhoff H, Preik M, Strauer BE. Serum nitrite sensitively reflects endothelial NO formation in human forearm vasculature: evidence for biochemical assessment of the endothelial L-arginine-NO pathway. Cardivasc. Res. 1999;41:765–772. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleinbongard P, et al. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;35:790–796. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cosby K, et al. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1498–1505. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doyle MP, Pickering RA, DeWeert TM, Hoekstra JW, Pater D. Kinetics and mechanism of the oxidation of human deoxyhemoglobin by nitrites. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:12393–12398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiter CD, et al. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat. Med. 2002;8:1383–1389. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]