Short abstract

In Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde the main protagonists take a love potion, which has various side effects and possibly causes Isolde's death. Gunther Weitz argues that the symptoms fit with severe anticholinergic syndrome

In the opera Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner reports the poisoning of Tristan and Isolde by a “love potion.” Shortly after ingestion of the potion, the protagonists declare their love, and both die during the opera. The opera has been extensively interpreted by psychoanalysts1-3 and musicologists,4-6 but, although at least Isolde's death remains unexplained and might be due to the potion, the medical profession has not yet analysed the case. I present evidence to suggest that the lovers were affected by a severe anticholinergic syndrome and that this is the most likely cause of Isolde's death.

The story of Tristan and Isolde (Iseult), who fell in immortal love after drinking a magic potion, originated in the 6th century and was told in England, Ireland, and the north of France. It first appeared in writing in the 12th century, and Wagner used as his source the poetry of Gottfried von Strassburg, from around 1210.7 Although Strassburg was familiar with alchemy,8 he did not report the side effects of the love potion. Wagner's detailed description of the symptoms suffered by the protagonists may indicate his attention to possible ingredients.

Presentation of the case

Tristan, nephew of King Marke and knight of the Cornish court, and Isolde, princess of Ireland and King Marke's bride, try to commit suicide together by drinking poison which, however, turns out to be a “love potion.” Within moments the first symptoms of an intoxication occur that can be interpreted as tachycardia, flush, and blurred vision (see synopsis of symptoms in the table). Tristan and Isolde fall passionately in love, but confusion and disorientation ensue. A few days later in a nocturnal scene (Act II), light intolerance is evident. At dawn Tristan is injured in a fight with a rival and later dies from his injuries (Act III). Shortly afterwards, Isolde experiences hallucinations and dies.

Table 1.

Synopsis of the symptoms caused by the love potion described by Wagner9 and the symptoms of an anticholinergic syndrome caused by Solanaceae10-12

| Wagner's description of the symptoms | Symptoms of intoxication with Solanaceae |

|---|---|

| — | Dry mouth, intense thirst (initial symptoms)* |

| Act I, scene 5 | |

| They are seized with trembling | Tachycardia, palpitation |

| They clutch convulsively at their hearts [fast rhythm, Tristan chord] and raise their hands to their heads | Flush, hyperthermia |

| Then their eyes seek out one another, are cast down in confusion... | Blurred vision |

| — | Urinary retention* |

| Tristan—bewildered [fails to recognise King Marke]: “...Which King?” | Disorientation |

| [Tristan chord] Isolde—confused: “...Where am I? Am I alive?...” | Confusion |

| Isolde falls on his breast, unconscious | Coma |

| Act II, scene 3 (a few days later) | |

| [Intolerance of light] “Oh, now we were dedicated to night! | |

| Spiteful day with ready envy could part us with his tricks...” | Pupillary dilatation, photophobia (may persist for several days) |

| [Cluster of Tristan chords] | |

| Act III, scene 3 (a few weeks later) (“Liebestod”) | |

| Isolde, aware of nothing round about her, fixes her gaze with mounting ecstasy upon Tristan's body: | |

| “How softly and gently he smiles, how sweetly his eyes open—can you see it my friends, do you not see it?...Do I alone hear this melody, so wondrously and gently...” | Visual and auditory hallucinations |

| — | Ataxia, hyperactivity, convulsions* |

| Isolde dies [Tristan chord] | Death |

Symptoms not represented in the opera.

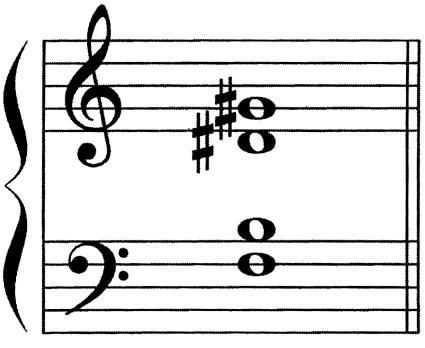

Wagner's use of the “Tristan chord” (fig 1) every time the potion or its effects are mentioned5 sheds some light on the toxicology of the active agent. Shortly after the drug is ingested, the Tristan chord changes from one notation to another, indicating a rapid onset of action. The symptoms described in the next scene are clearly attributed to the potion, and the Tristan chord is repeated prominently. In a love scene a few days later (Act II, scene 2) both protagonists express marked light intolerance, and that this is caused by the potion is suggested by a cluster of Tristan chords. At the moment of Tristan's death there is no Tristan chord, whereas Isolde's remarkable behaviour before her demise is explained as being due to the potion by the occurrence of a Tristan chord. This latter scene is widely known as the “Liebestod” (fig 2).

Fig 1.

The “Tristan chord” in Wagner's Tristan und Isolde

Love medicine in Europe

Medieval strategies for modulating mood drew extensively on Roman ideas.13 Food was believed to influence humors, and for specific effects meals were prepared according to elaborate and refined ceremonies.14 Many ingredients that were associated with aphrodisiac properties—such as egg, peacock, fowl, beef, venison, crustaceans, leek, turnip, asparagus, pomegranate, mustard, and pepper14,15—would not be recognised as such nowadays. Others have reproducible effects: cantharidin, an extract from dried bodies of blister beetles, causes urethral irritation sometimes followed by erection. Yohimbine, a central acting α receptor blocker derived from the bark of an African tree, has since been recommended for the treatment of impotence.15-17

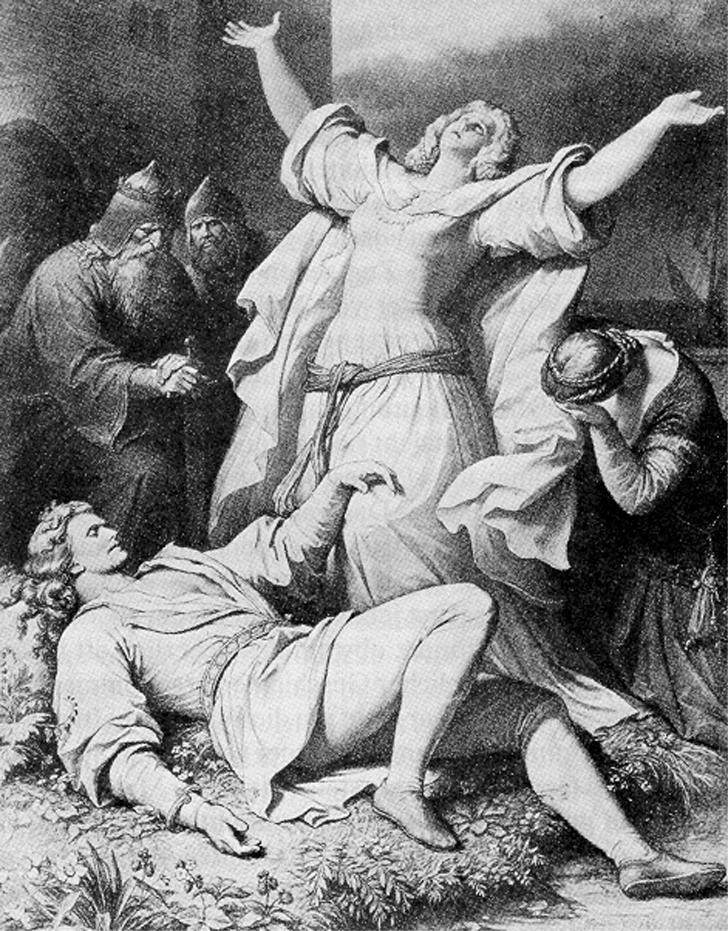

Fig 2.

The “Liebestod” in a picture by Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1866)

The variety of psychotropic drugs in medieval Europe was small, since only a few local plants are able to exert an action on the central nervous system. Wine and beer were widespread, but the most effective hallucinogenic agents were derived from nightshade plants (Solanaceae).18-20 Recipes of love stimulants frequently contained such plants, especially henbane (Hyoscyamus niger), mandrake (Mandragora officinarum), and in later times thorn apple (Datura stramonium).14,19,21 These plants have in common high concentrations of hyoscyamine, atropine, and scopolamine—anticholinergic alkaloids that act on both the peripheral and central nervous system. Hyoscyamine and atropine are found to have more exciting properties, and scopolamine more relaxing and hallucinogenic properties.22

Knowledge of the pharmacological properties of Solanaceae was handed down in folk medicine,18,21 and they were often referred to by Shakespeare in his plays.19,23 Their use as hallucinogens declined during the 19th century with the increasing availability of more effective drugs such as cannabis and cocaine.21

Discussion

Wagner's presentation of Tristan and Isolde's symptoms is as close to intoxication by Solanaceae as can be suggested in an opera (see table). The rapid onset of peripheral anticholinergic symptoms and the symptoms marked by the Tristan chord are typical of an overdose of this agent. The initial presentation of dry mouth and intense thirst is not described, perhaps because of difficulties in illustration. Instead, tremor is indicated, which would be unusual because the biochemical lesion is predominantly at muscarinic and not nicotinic sites except in massive overdosing, which is not described in the first scene. Hallucinations caused by Solanaceae are mostly visual and consist of simple images in natural colours—in contrast to other hallucinogens such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) or mescaline, which typically produce a brilliant and shifting interplay of light and colour.10 However, auditory hallucinations as in the “Liebestod” have also been described after ingestion of Solanaceae,11 and emphasising the audible may be a stylistic device in an opera. Fatalities in adults as a result of overdose of Solanaceae are rare and can be secondary to cardiac or respiratory arrest.10,12

The symptoms of an intoxication usually resolve within 24-48 hours; however, pupillary dilatation can persist for several days,10 as described in Act II. Much later, in his dying scene, Tristan is no longer intoxicated (no Tristan chord), and his death must therefore be attributed to his injuries. Isolde's psychotic behaviour when she approaches Tristan's body might be interpreted as hysteria, but this could not explain her death. Wagner's use of a Tristan chord in the moment of her death indicates that both hallucinations and death are attributable to the love potion. It is likely that she took a further draught. Wagner, unlike Gottfried von Strassburg, makes no reference to there being no love potion left after the first ingestion.

Alkaloids from Solanaceae may induce a delirious state, but, despite their frequent use in medieval love potions, they do not have specific eroticising properties. Wagner takes this into account by illustrating that Tristan and Isolde are in love before drinking the potion, though unable to admit it. Hence, the “love potion” only has a liberating effect. The German novelist Thomas Mann claimed that Tristan and Isolde could as well have drunk a glass of water.7 Nevertheless, Wagner's close description of an anticholinergic syndrome favours an ingestion of a potion containing Solanaceae and underlines his careful treatment of this issue.

Summary points

The article analyses the composition of the love potion in Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde from a medical view

The libretto and the music suggest that an anticholinergic compound is the active agent

Medieval love potions often contained anticholinergic alkaloids from plants of the Solanaceae family

The knowledge of the properties of Solanaceae was handed down in folk medicine until the 19th century

The unexplained death of Isolde at the end of the opera could be explained by a severe anticholinergic crisis

I gratefully acknowledge the substantial support of Jonathan Folb (London) in preparing the manuscript and the technical assistance of Sven Süfke (Lübeck).

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Gediman HK. On love, dying together and Liebestod fantasies. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1981;29: 607-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chessick RD. On falling in love: the mystery of Tristan and Isolde. In: Feder S, Karmel RL, eds. Psychoanalytic explorations in music. Madison, CT: International Universities Press, 1990: 465-83.

- 3.Haule JR. Divine madness. Archetypes of romantic love. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications, 1990.

- 4.Hill C. That Wagner-Tristan chord. Mus Rev 1984;45: 7-10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knapp R. The tonal structure of Tristan und Isolde: a sketch. Mus Rev 1984;45: 10-25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richey J. History and the Tristan chord. Mus Rev 1994;55: 97-103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pahlen K. Richard Wagner. Tristan und Isolde. München: Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, 1983.

- 8.Ober PC. Alchemy and the “Tristan” of Gottfried von Strassburg. Monatshefte für den Deutschunterricht 1965;57: 321-35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Translation of the libretto. Booklet with recording of Tristan und Isolde, conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler, 5562542. London: EMI Records, 1997.

- 10.Gowdy JM. Stramonium intoxication. Review of symptomatology in 212 cases. JAMA 1972;221: 585-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mikolich JR, Paulson GW, Cross CJ. Acute anticholinergic syndrome due to Jimson seed intoxication. Ann Intern Med 1975;83: 321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldsmith SR, Goldsmith IF, Ungerleider JT. Poisoning from ingestion of a Stramonium-Belladonna mixture. JAMA 1968;204: 169-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson SW. Unusual mental states in medieval Europe. I. Medical syndromes of mental disorders 400-1100 AD. J Hist Med Allied Sci 1972;27: 262-97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cosman MP. A feast for Aesculapius: Historical diets for asthma and sexual pleasure. Ann Rev Nutr 1983;3: 1-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shampo MA, Kyle RA. Medical mythology: Aphrodite (Venus). Mayo Clin Proc 1992;67: 477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karras DJ, Farrell SE, Harrigan RA, Henretig FM, Gealt L. Poisoning of “Spanish fly” (Cantharidin). Am J Emerg Med 1996;14: 478-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon M. Alternative medicines toxicology: A review of selected agents. Clin Toxicol 1999;37: 709-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Völger G, von Welck K. Rausch und Realität. Drogen im Kulturvergleich. Reinbek: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, 1982.

- 19.Müller JL. Love potions and ointment of witches: historical aspects of nightshade alkaloids. Clin Toxicol 1998;36: 617-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piomelli D, Pollio A. A study in Renaissance psychotropic plant ointments. Hist Phil Life Sci 1994;16: 241-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fühner H. Solanazeen als Berauschungsmittel. Eine historischethnologische Studie. Arch Exp Pathol 1926;111: 281-94. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Betz P, Janzen J, Roider G, Penning R. Psychopathologische Befunde nach oraler Aufnahme von Inhaltsstoffen heimischer Nachtschattengewächse. Arch Kriminol 1991;188: 175-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter AJ. Narcosis and nightshade. BMJ 1996;313: 1630-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]