SUMMARY

Aim of the present report is to describe a case of radionecrosis related to radiotherapy of the larynx and to review the literature. A review was made of the hospital chart, surgery report, imaging studies and pathological findings of a 51-year-old male patient came to our attention. Results indicated that radionecrosis often requires total laryngectomy. It is very rare, but morbidity and mortality rates are high. The interval between conclusion of radiation therapy and development of radionecrosis ranges from 3 to 12 months. In this report, a case of radionecrosis is presented which has been managed using the organ sparing strategy. In conclusion, the larynx may be spared when radionecrosis occurs but more investigations are required in order to define the most appropriate treatment.

KEY WORDS: Larynx, Malignant tumours, Radiotherapy, Radionecrosis, Laryngocutaneous fistula reconstruction

RIASSUNTO

Scopo di questo studio è la descrizione di un caso di radionecrosi della laringe conseguente a radioterapia ed una revisione della letteratura sull’argomento. A questo scopo è stata effettuata una revisione della cartella clinica, del report chirurgico, delle indagini strumentali e degli esami istologici di un uomo di 51 anni, giunto alla nostra attenzione. I risultati indicano che la radionecrosi della laringe spesso richiede la laringectomia totale, in quanto, pur essendo un evento raro, presenta elevata morbidità e mortalità. Il periodo intercorso tra la fine della radioterapia e lo sviluppo di radionecrosi è in genere variabile tra i 3 e i 12 mesi. In questo articolo viene riportato un caso di radionecrosi della laringe che è stato trattato utilizzando una strategia conservativa. In conclusione, è possibile risparmiare la laringe in caso di radionecrosi ma occorrono maggiori dati per la definizione del trattamento più appropriato.

Introduction

Radiation has been used for treatment of laryngeal carcinomas for more than 60 years. With the advances in radiation technology and current trends of treating advanced- stage laryngeal tumours with organ sparing protocols, external-beam radiation has become the treatment modality of choice for certain stages of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). However, it should be borne in mind that every method has its complications, like its indication. There are several complications encountered during radiotherapy such as laryngeal oedema, skin damage, perichondritis and cartilage necrosis 1.

Permanent histological effects can occur within the soft tissues of the neck with radiation doses as low as 12 Gray (Gy). In 1979, Chandler proposed a grading system for laryngeal radionecrosis (Table I) 2. There is a direct relationship between the number of rads delivered and the severity of the subsequent radiation reaction. Grade I and II are expected as side-effects of radiation and do not require aggressive treatment except humidification, voice restraint, need to refrain from active or passive smoking and using N-acetylcysteine, etc.. Grade III and IV reactions are more severe, have less favourable outcomes, and are considered as major complications that usually require surgery. Although chondronecrosis of the larynx is a very rare complication in otorhinolaryngology, the incidence increases daily due to more frequent use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. If chondronecrosis occurs, it can result in serious sequelae or even in death, and it is known that there is no chance of recovery 1 3 4. The most frequent cause of chondronecrosis is radiotherapy but also recurrent perichondritis, long- or short-term intubations, infection, trauma, tracheotomy, and neoplasia can be included among the causes. The incidence is related to tumour grade as well as the radiotherapy dosage. The case is described of a 51-year-old white male with laryngeal carcinoma treated by radiotherapy.

Table I. Chandler classification for laryngeal radionecrosis.

| Symptoms | Signs | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade I | Slight hoarseness, slight dryness | Slight oedema, telengiectasis | Symptomatic care: humidification, anti-reflux therapy, smoking cessation |

| Grade II | Moderate hoarseness, moderate dryness | ||

| Grade III | Severe hoarseness with dyspnoea, moderate odynophagia and dysphagia | Severe impairment of vocal cord mobility or fixation of one cord, marked oedema, skin changes | Symptomatic care + steroids, antibiotics Tracheotomy or laryngectomy, if necessary |

| Grade IV | Respiratory, distress, severe odynophagia, weight loss dehydration | Fistula, fetororis, fixation of skin to larynx, airway obstruction, fever | Tracheotomy and/or laryngectomy |

Case report

A 51-year-old male patient came to our attention, in March 1999, complaining of hoarseness for 7 months. At the direct laryngoscopic examination of the patient, a mass was detected completely attacking the left vocal cord, filling the ventricule, expanding to the anterior commissure and causing fixation of the left cord. The specimen, taken at direct laryngoscopy, under general anaesthesia, was defined as epidermoid carcinoma. In the light of these data, the patient was accepted as T3N0MX. Surgery was offered primarily, but the patient chose radiotherapy.

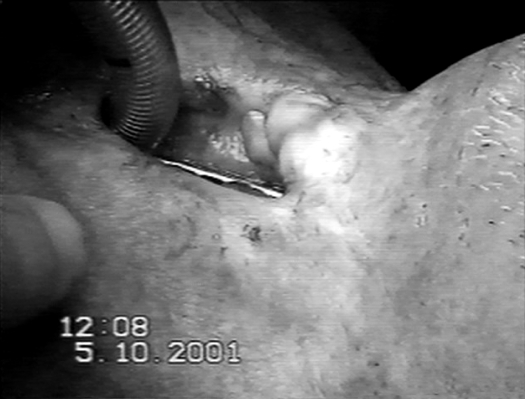

In this treatment, 2 daily dosages of 36 Gy fractions (total 72 Gy), with Co-60 tele therapy, to the primary tumour site, were applied + bilateral neck, daily 2 Gy dosage, total 60 Gy + supraclavicular region, daily 2 Gy dosage, total 60 Gy were applied. With the 42 Gy, medulla spinalis is preserved and, during radiotherapy, oral cavity, skull base and bilateral lung apex were preserved. At the end of the treatment, there were no major side-effects except grade II mouth dryness, grade I radiodermatitis and hoarseness. Increasing dyspnoea and difficulty in swallowing developed 2 months after the radiotherapy, consequently immediate tracheotomy was performed. Examination of the patient showed a widespread mass and/or oedema in the larynx and fixation in both cords and arytenoids. Halitosis and pain upon palpation of the neck were also observed. These findings were considered as a recurrence and a punch biopsy was taken. There was no carcinoma, only necrotic and fibrotic findings were found upon pathological investigation. Necrosis of the thyroid framework and adjacent soft tissue was revealed at Computed Tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1). Disrigidity of the thyroid cartilage and oedema of the mucosa led us to a diagnosis of radionecrosis of the larynx and total laryngectomy was offered. However, the patient refused the surgical treatment, and therefore symptomatic treatment was applied. A feeding tube was placed; treatment with ciproflaxacine, multivitamins (A, B and E), corticosteroids, non-steroidal antiin "ammatory drug and intravenous liquid replacement with isotonic solutions were administered. The patient was discharged at his request and followed as an outpatient. After two years, he was admitted to the hospital with a laryngo-cutaneous fistula at the middle line of the neck. At the endoscopic examination, the orifice of the fistula, inside the larynx, was observed just under the petiole. Both cords and the arytenoids were normal. Furthermore, there was no local tumour recurrence according to endoscopic and microscopic larynx examination and control biopsies. At the CT scan, a defect was identified at the centre of the thyroid lamina. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed normal findings except for a fistula. There were no problems at the cricoids and epiglottis cartilage. Therefore, laryngeal reconstruction was planned under general anaesthesia (Fig. 2) and the patient was operated via apron flap incision on October 5th, 2001. A tracheotomy was performed through the 4th-5th rings of the trachea. The thyroid cartilage was closed with the pulldown method by the epiglottis, and the skin defect was closed with turnover platysma myocutaneous flaps after wide local excision. Airway stabilization was provided by placing a silicone T tube for 8 weeks. One week later, a flap feeding disturbance occurred. The repaired cartilage had healed on the inner side of the fistula but the skin flap was ulcerated and the size of the wound had become larger than at the beginning. Meanwhile, we applied mitomycin C and daily scraping. There were no wound closures. The part of the skin presenting necrosis and the tracheotomy were reconstructed by pectoral myocutaneous flap after 8 weeks (Fig. 3). The flap was functionally adequate, both in the reconstruction of the tracheotomy and for repair of the large skin defect. On the 29th post-operative month, no local recurrence or distant metastasis have been seen yet. No concomitant chemotherapy was used.

Fig. 1. Laryngostoma due to radionecrosis.

Fig. 2. Pre-operative aspect of the laryngostoma.

Fig. 3. Results after myocutaneous flap reconstruction.

Discussion

The first report dates back to the 1940s when Stone conducted a series of clinical studies using an early cyclotron for the radiotherapy treatment at Berkeley. A total of 249 patients were treated, and about half of these patients had head neck tumours 5. Radiation therapies for SCC of the larynx have become increasingly safe and effective over the last 20 years. This is the consequence of the attempts to spare anatomy and function without compromising tumour control that have been developed. The incidence of severe reactions following 50-60 Gy had decreased from 5-12%, in the 1970s, to approximately 1%, in the 1990s. Radiotherapy induces a hypoxic environment by stimulating reactive fibrosis and end-arteritis of blood vessels, as well as obliteration and fibrosis of the lymphatic system. Oedema develops secondary to increased permeability and decreased lymphatic drainage, which leads to further reduction of the nutrient supply 3.

Major late complications, due to radiotherapy, typically occur following a latent period of approximately 3 months because of the long-standing hypo-vascularity6. Laryngeal oedema is the most frequently encountered complication, and, at the same time, the first symptom of chondronecrosis and this might cause false or late diagnosis. The rate of clearance of the oedema is related to radiation dose, volume of tissue radiated, addition of neck dissection and size and extent of the original lesion. The most common complication, persistent laryngeal oedema, occurs in 13.7% of patients who receive a dose less than 70 Gy but rises to 46.2% with doses of 70 Gy or more.

Of the patients undergoing radiotherapy, 1-5% may develop radiation-induced chondronecrosis. Risk factors for development of chondronecrosis include use of alcohol and tobacco (most significant), tumour invasion, post-operative infection, trauma, and the radiation technique. Intact perichondrium can tolerate large doses of radiation 3. The cartilaginous framework becomes defective and unstable in a patient with laryngeal chondronecrosis. This alters the airway size, mobility and structure. Patients may present clinically with any of the following: dysphagia, odinophagia, hoarseness, stridor, dyspnoea, respiratory obstruction, recurrent aspiration, fever, weight loss, and dehydration. Most patients become symptomatic within the first 3 months after radiotherapy. However, there are case reports of patients presenting necrosis 25, 44 and even 50 years after radiotherapy because of fibrosis and endarteritis continuing with time 6 7.

The typical patient with radiation-induced chondronecrosis initially develops symptoms of hoarseness and breathiness. The arytenoid cartilages are involved most frequently when chondronecrosis occurred in association with radiotherapy. The crico-arytenoid joint is usually affected, and the arytenoids may become partially fixed without complete rotation or medial sliding motion along the cricoid. Due to this limited mobility, the ability to fully abduct or adduct the vocal folds may be impaired. Without full abduction, mild stridor or exercise intolerance may occur and become progressive. Incomplete vocal fold closure causes breathiness and potential for aspiration. The usual course is to have greater difficulty with liquids than with solids, but progressive dysphagia may occur. The accessory laryngeal muscle activity may become impaired due to fibrosis, and thus, the normal laryngeal elevation needed for swallowing fails, leading to an unprotected airway. If an individual has recurrent aspiration secondary to poor swallowing function, pneumonia and respiratory compromise can occur. Recurrent pneumonia is a definitive indication for laryngectomy3.

The diagnosis of radiation necrosis is made on clinical presentation and examination. Although radio-imaging is often part of the work-up, both CT and MRI are not helpful in distinguishing between radio-necrosis and recurrent tumour 3 7. It has been suggested that Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanning may be beneficial in identifying occult malignancy in this situation. PET, according to McGuirt et al. 8, has proved reliable, with the ability to differentiate tumour from radiation effect in more than 80% of cases. The resolution of PET, however, is 6 mm. Therefore, microscopic deposits of cancer may not be seen, and larger deposits may be masked by pooled saliva 3.

The most common treatment modality of the laryngeal radionecrosis is total laryngectomy 3 4 6 7. Also the common opinion was the medical management offering only temporarily, symptomatic relief, which further requires surgical treatment for late stage reactions (Grade III and IV). Medical treatment options are limited and include antibiotics anti-reflux agents, corticosteroids, humidification, feeding tube and sputum for culture and sensitivity. Hyperbaric oxygen in radionecrosis is another proposed treatment modality. Ferguson et al. reported that signs and symptoms of radionecrosis were dramatically improved in 7/8 patients (Grade III and IV), with hyperbaric oxygen therapy 9. Filntisis et al. reported that 13 (72.2%) of the 18 patients (2 had grade III and 16 had grade IV radionecrosis), showed a major improvement after hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and none of them required total laryngectomy 10.

Surgical treatment of the grade III and IV patients is still a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. There is no clear evidence of how aseptic necroses start and what limits the necrosis. If airway obstruction is present, surgical management may start with a tracheotomy. At the same time, laryngeal endoscopy and biopsy is indicated to rule out the malignancy. Due to essential principles, necrotic tissue must be excised to promote healing. Therefore, if the effected laryngeal cartilages were removed, necrosis should stop and the larynx should heal. Instead of doing total laryngectomy primarily, removing necrotic cartilage and allowing secondary wound healing may result in a return of the progress. But these theories must be justified with more clinical and animal experiences. At the second stage, a myocutaneous flap from a nonradiated site should be used for closing the fistula because long-standing hypovascularity of the skin impairs the healing process. The pectoralis major flap is widely accepted on account of its versatility in head and neck cancer reconstructions. It is supplied by the thoraco-acromial artery, with additional circulation provided by the lateral thoracic artery 11.

Conclusions

Although total laryngectomy has been considered mandatory for the treatment of radionecrosis, we saw that it could be reconstructed without total laryngectomy. In spite of this case report, we cannot offer medical therapy. Progressivism and malignancy of the radionecrosis, which are considered as the causes of total laryngectomy, must be investigated again. Also radiated larynx and anterior neck defects may both be reconstructed functionally. Salvage surgery, after radiation failures, may be performed with an adequate technique and flaps. Vascularised tissue transfer and vascularised muscle transfer are both useful reconstruction methods for the treatment of necrosed tissues.

References

- 1.Rowley H, Walsh M, McShane D, et al. Chondroradionecrosis of the larynx: Still a diagnostic dilemma. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:218–220. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100129731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandler JR. Radiation fibrosis and necrosis of the larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979;88:509–514. doi: 10.1177/000348947908800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oppenheimer RW, Krespi YP, Einhorn RK. Management of laryngeal radionecrosis: animal and clinical experience. Head Neck. 1989;11:252–256. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880110311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez CA, Thorstad WL. Unusual nonepithelial tumors of the head and the neck. In: Halperin EC, Perez CA, Brady LA, editors. Principles and practice of radiation oncology. 5th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008. pp. 996–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone RS. Neutron therapy and specific ionization. Am J Roentgenol. 1948;59:771–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takiguchi Y, Okamura HO, Kitamura K, et al. Late laryngotracheal cartilage necrosis with external fistula 44 years after radiotherapy. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117:658–659. doi: 10.1258/002221503768200048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald PJ, Koch RJ. Delayed radionecrosis of the larynx. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20:245–249. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(99)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGuirt WF, Greven K, Williams D, 3rd, et al. PET scanning in head and neck oncology: a review. Head Neck. 1998;20:208–215. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199805)20:3<208::aid-hed5>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson BJ, Hudson WR, Farmer JC. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for laryngeal radionecrosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1987;96:1–6. doi: 10.1177/000348948709600101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filntisis GA, Moon RE, Kraft KL, et al. Laryngeal radionecrosis and hyperbaric oxygen therapy: report of 18 cases and review of the literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:554–562. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dedivitis RA, Guimaraes AV. Pectoralis major musculocutaneous flap in head and neck cancer reconstruction. World J Surg. 2002;26:67–71. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]