Abstract

A novel pandemic influenza H1N1 (pH1N1) virus spread rapidly across the world in 2009. Due to the important role of antibody-mediated immunity in protection against influenza infection, we used an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based microneutralization test to investigate cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies against the 2009 pH1N1 virus in 229 stored sera from donors born between 1917 and 2008 in Taiwan. The peak of cumulative geometric mean titers occurred in donors more than 90 years old and declined sharply with decreasing age. Sixteen of 27 subjects (59%) more than 80 years old had cross-reactive antibody titers of 160 or more against the 2009 pH1N1 virus, whereas none of the donors from age 9 to 49 had an antibody titer of 160 or more. Interestingly, 2 of 51 children (4%) from 6 months to 9 years old had an antibody titer of 40. We further tested the antibody responses in 9 of the 51 pediatric sera to three endemic seasonal influenza viruses isolated in 2006 and 2008 in Taiwan, and the results showed that only the 2 sera from children with antibody responses to the 2009 pH1N1 virus had high titers of neutralizing antibody against recent seasonal influenza virus strains. Our study shows the presence of some level of cross-reactive antibody in Taiwanese persons 50 years old or older, and the elderly subjects who may already have been exposed to the 1918 virus had high titers of neutralizing antibody to the 2009 pH1N1 virus. Our data also indicate that natural infection with the Taiwan 2006 and 2008 seasonal H1N1 viruses may induce a cross-reactive antibody response to the 2009 pH1N1 virus.

Influenza A viruses have caused several pandemics during the past century and continue to cause epidemics around the world yearly. Pandemics are typically caused by the introduction of a virus with a hemagglutinin (HA) subtype that is new to human populations (14). In 2009, a novel pandemic influenza H1N1 (pH1N1) virus of swine origin spread rapidly and has caused variable disease globally via interhuman transmission (2, 3).

The 2009 pH1N1 virus contains a unique combination of gene segments from both the North American and Eurasian swine lineages and is antigenically distinct from any known seasonal human influenza virus (14). Since H1N1 influenza A viruses have been circulating in human populations for decades, much of the world has encountered these viruses repeatedly, either through infection or through vaccination. Under the threat of a pandemic outbreak, however, a major concern is whether preexisting immunity can provide some protection from the novel 2009 pH1N1 virus.

Recent reports from the United States suggested that 33% of individuals over the age of 60 years had neutralization antibodies to the novel 2009 pH1N1 virus, probably due to previous exposure to antigenically similar H1N1 viruses (1, 7). In Japan, however, appreciable neutralization antibodies against the 2009 pH1N1 virus were found only in individuals more than 90 years old (9). The differences in geographical location and vaccination programs against influenza in 1976 may account for the different age distributions of neutralization antibodies in the two countries. In the early 1900s, Taiwan had had a close relationship with Japan historically and geographically. The prevalence of influenza in Taiwan may be quite similar to that in Japan. In recent years, however, sequence analysis of epidemic influenza virus strains revealed that the Taiwanese strains usually circulate in Taiwan prior to their circulation in many other countries, including Japan. (16). The differences between the studies from United States and Japan, and the unique epidemic situation in Taiwan, highlight the need for us to assess the level of preexisting immunity in the Taiwanese population.

In this study, we measured the titers of neutralizing antibodies against the 2009 pH1N1 virus in sera obtained from previous influenza infection or vaccination of different age groups. In addition, we also assessed the antibodies against the local seasonal H1N1 strains isolated in Taiwan in 2006 and 2008 (A/Taiwan/N86/06, A/Taiwan/N94/08, and A/Taiwan/N510/08) to evaluate whether there is a cross-reactive antibody response between recent local strains and the 2009 pH1N1 virus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

We collected stored-serum panels from a previous study conducted in 2008. These human sera were collected from donors who visited or were admitted to the National Cheng Kung University Hospital between January and December 2008, with approval from the institutional review board; written informed consent was provided. The demographic data, history of seasonal influenza vaccination, clinical presentations, complications, and outcomes were retrospectively reviewed.

MicroNT-ELISA.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based microneutralization test (microNT-ELISA) modified from a previously described procedure (5) was used. Briefly, human sera were pretreated with a receptor-destroying enzyme, and 2-fold serial dilutions were performed in a 50-μl volume of diluent in 96-well tissue culture plates. The diluted sera were mixed with an equal volume of diluent containing influenza virus at 200 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50)/100 μl. In addition, four control wells of virus plus diluent (VC) or diluent alone (CC) were included on each plate. After a 2-h incubation at 37°C under 5% CO2, 100 μl of MDCK cells at 1.5 × 105/ml was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 18 h at 35°C under 5% CO2. The monolayers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were fixed in cold 80% acetone for 10 min. The fixed plates were then washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (wash buffer). The presence of influenza viral protein was detected by ELISA with a monoclonal antibody to the influenza A virus NP (Abcam). The anti-influenza virus antibody was diluted to 1 μg/ml (influenza A) in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% Tween 20; then 100 μl of diluted antibodies was added to each well. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The plates were washed four times in wash buffer, and 100 μl of 1:2,000 horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Kirkegaard & Perry) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and were then washed six times with wash buffer. After that, the freshly prepared substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (100 μl) (Life Technologies) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl of 2N sulfuric acid. Absorbance at 450 nm (A450) was measured. The neutralizing endpoint was determined by using a 50% specific signal (X) calculation. The endpoint titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum with an A450 value less than X, where X is calculated as [(average A450 of VC wells) − (average A490 of CC wells)]/2 + (average A450 of CC wells).

Neutralization antibody responses to A/California/07/2009 H1N1 in all serum samples were tested. In the pediatric group aged 6 months to 9 years, neutralization antibodies against Taiwanese seasonal influenza virus strains isolated in 2006 and 2008, A/Taiwan/N86/06, A/Taiwan/N94/08, and A/Taiwan/N510/08 H1N1, were also investigated for the comparison. All serum specimens were tested in duplicate.

RESULTS

Cross-reactive antibodies in populations of different ages.

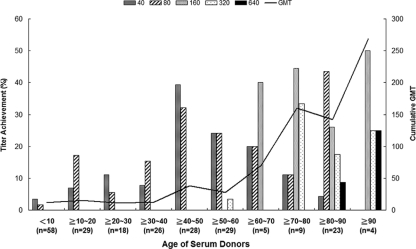

To investigate the age distribution of cross-reactive neutralization antibodies against the 2009 pH1N1 virus in Taiwanese populations, we tested a collection of 229 serum samples from donors born between 1917 and 2008. The donors were divided into 5 groups according to age: 6 months to <9 years (n = 51), 9 to <19 years (n = 33), 19 to <49 years (n = 71), 49 to <79 years (n = 47), and >79 years (n = 27). The serum samples were drawn between 2007 and 2008, prior to the pandemic outbreak. The peak of the cumulative geometric mean titers (GMT) occurred in donors over the age of 90 years (i.e., born in or before 1919), and GMT declined sharply with decreasing age (Fig. 1). Approximately 16 of the 27 subjects (59%) over the age of 79 (i.e., born before 1928) had a cross-reactive antibody titer of 160 or more. None of the donors from the age of 9 to 49 years had an antibody titer of 160 or more against the 2009 pH1N1 virus. Of the 51 children ranging in age from 6 months to 9 years, only 2 (4%) had an antibody titer of 40 against the 2009 pH1N1 virus (Table 1). Comprehensive bacterial and viral cultures had been performed for these 2 pediatric cases at the time of serum collection. By thorough medical chart reviews, we found that neither of these children had received seasonal flu vaccination before or had a documented history of flu infection. One of the children, however, had an underlying disease, idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis, and needed blood transfusions several times before neutralization antibody detection.

FIG. 1.

Titers of neutralizing antibody against the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus among serum donors, according to age distribution. Serum samples were collected between 2007 and 2008 and were tested by an ELISA-based microneutralization test. The proportions of individuals with neutralizing antibody titers of 40, 80, 160, 320, and 640 are plotted on the left ordinate, according to the age distribution of serum donors. The cumulative geometric mean titer for all subjects in each age decade is shown as a black line (right ordinate).

TABLE 1.

Cross-reactive microneutralization antibody response against pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus in children and adults

| Age group | No. of subjectsa | No. (%) with a microneutralization titer of ≥40 for children or ≥160 for adults |

|---|---|---|

| 6 mo-9 yr | 51 | 2 (4) |

| ≥9 yr-19 yr | 33 | 0 (0) |

| ≥19 yr-49 yr | 71 | 0 (0) |

| ≥49 yr-79 yr | 47 | 10 (21) |

| ≥79 yr | 27 | 16 (59) |

The total number of subjects was 229.

Cross-reactive antibody response from previous natural infection.

Since influenza infection could be asymptomatic, and we tried to figure out the reason why the 2 children bear cross-reactive antibodies against the 2009 pH1N1 strain, we next tested the cross-reactive antibody responses of the sera to the 2006 and 2008 endemic seasonal influenza viruses in Taiwan. We randomly selected 7 serum samples from children 6 months to 9 years old without titers of preexisting antibodies to the 2009 pH1N1 virus as a control group in order to determine whether children naturally infected with the 2006 or 2008 endemic influenza virus strains developed cross-reactive antibodies to the 2009 pH1N1 virus. We found that of 9 serum samples, only those 2 from the children with preexisting cross-reactive antibodies against the 2009 pH1N1 virus had high titers of neutralizing antibodies (1:1,280) to the A/Taiwan/N86/06, A/Taiwan/N94/08, and A/Taiwan/N510/08 strains (Table 2). In contrast, we could detect little or no antibody response to these Taiwanese seasonal H1N1 strains in any other children. We further randomly screened neutralizing antibodies against these 3 local seasonal influenza strains in the sera of adults between the ages of 19 and 49 years, older adults over the age of 80 years, pH1N1 virus-inflected adult patients, and healthy pH1N1 virus vaccinees. Generally, only the subjects who had high titers of neutralizing antibodies to these 3 local seasonal influenza strains between 2006 to 2008 would have cross-reactive antibodies to the 2009 pH1N1 virus, and vice versa (Table 2). In addition, we found that these three local endemic influenza virus strains (A/Taiwan/N86/06, A/Taiwan/N94/08, and A/Taiwan/N510/08) and A/Brisbane/59/07 had similar amino acid sequences at the 5 important antigenic sites reported previously.

TABLE 2.

Cross-reactive microneutralization antibody responses to endemic seasonal influenza A (H1N1) and pandemic influenza A (pH1N1) viruses in different groups of subjects

| Group and subject code | Microneutralization titer |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/Taiwan/N86/06 | A/Taiwan/N94/08 | A/Taiwan/N510/08 | A/California/7/09 | |

| 6 mo-9 yr | ||||

| 347 | 1,280 | 1,280 | 1,280 | 40 |

| 520 | 1,280 | 1,280 | 1,280 | 40 |

| 425 | <10 | 10 | <10 | 20 |

| 489 | <10 | 10 | <10 | 20 |

| ≥19-49 yr | ||||

| 176 | 40 | <10 | 80 | <10 |

| 99 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| 90 | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| 174 | 80 | 20 | 80 | <10 |

| ≥79 yr | ||||

| 20 | 1,280 | 320 | 1,280 | 640 |

| 360 | 640 | 640 | 1,280 | 320 |

| 699 | 160 | 80 | 160 | 160 |

| 704 | 160 | 80 | 640 | 320 |

| 705 | 320 | 320 | 640 | 640 |

| pH1N1 virus-infected adult patients | ||||

| P1 | 80 | 80 | 320 | 160 |

| P5 | 320 | 40 | 640 | 160 |

| P8 | 1,280 | 640 | 1,280 | 320 |

| P9 | 160 | 160 | 320 | 640 |

| Healthy pH1N1 vaccinees | ||||

| V2 | 1,280 | 640 | 1,280 | 320 |

| V5 | 40 | 40 | 320 | 1,280 |

| V6 | 640 | 320 | 640 | 1,280 |

| V8 | 160 | 320 | 640 | 1,280 |

| V9 | <10 | 20 | 40 | 80 |

| V10 | 40 | 20 | 80 | 1,280 |

Although neither of the two children had previously had a documented culture-proven influenza virus infection, these data suggested that natural infection with Taiwan 2006 and 2008 seasonal influenza H1N1 viruses may lead to the generation of serum antibodies that are, on some level, cross-reactive with the 2009 pH1N1 strain.

DISCUSSION

The data from our study showed the presence of some level of cross-reactive antibody in Taiwanese persons 50 years old or older. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies showing similar serum antibody responses to the 2009 pH1N1 virus for members of a birth year cohort (1, 7, 9). Furthermore, this study also indicated that elder subjects who may have been exposed to the 1918 virus had high titers of neutralizing antibodies to the 2009 pH1N1 virus.

Previous studies of the effects of the 1918 influenza pandemic indicated that this pandemic swept Taiwan in 2 waves, once at the end of 1918 and again in the spring of 1920, causing devastating loss of human life. This pandemic flu affected Taiwan for a long time (8). After that, whether there was small-scale infection caused by the same viral strain or closely related H1N1 viruses in Taiwan remains a mystery. In this study, we found that subjects born before 1928 had a cross-reactive antibody titer of 160 or more against the 2009 pH1N1 virus. In contrast to our data, Itoh et al. recently reported that no appreciable cross-reactive antibody was detected in individuals born after 1920 in Japan (9). The dissimilarity in the lengths of the 1918 flu epidemic in Taiwan and Japan may account for the differences in the distribution of appreciable neutralizing antibodies between the two studies.

In addition, the hemagglutinin of the 2009 pH1N1 virus has been reported to have greater antigenic and genetic similarity to the swine H1N1 influenza virus that caused an influenza outbreak in the United States in 1976 than to contemporary human seasonal influenza H1N1 viruses (4, 13). This outbreak then led to a national vaccination campaign (10). A report by Hancock et al. indicates that the national vaccination campaign in 1976 may have substantially boosted levels of cross-reactive antibodies to the 2009 pH1N1 virus in older adults in the United States (7). Although there were not enough documents indicating any unusual influenza outbreak or national vaccination campaign in 1976 in Taiwan, a recent study has shown Taiwan to be an evolutionarily leading region for the global circulation of influenza A (16). We suspected that the Taiwanese population may be exposed to such influenza viruses resembling the 1976 influenza virus or a closely related human H1N1 virus. Previous natural infection with these 2009 pH1N1 virus-like viruses in some older Taiwanese adults 50 to 80 years of age may contribute to the observed cross-reactive antibody response to the 2009 pH1N1 virus in our study.

Most of the serum samples from our children between the ages of 6 months and 9 years had no cross-reactive antibodies against the 2009 pH1N1 virus. Only 2 of these 51 children had a neutralization antibody titer of 40 against the 2009 pH1N1 virus. Although one child may have obtained the antibody passively by blood transfusion, the possibility of cross-reactive antibody induction by recent natural infection cannot be excluded. In our study, only these 2 children had much higher titers of neutralizing antibodies against the A/Taiwan/N86/06, A/Taiwan/N94/08, and A/Taiwan/N510/08 H1N1 viruses than those who had no cross-reactive antibodies to the 2009 pH1N1 virus. Similar results were also found for adults, the elder population, pH1N1 virus-infected patients, and healthy vaccinees. We analyzed these seasonal Taiwanese influenza virus strains and the 2009 pH1N1 virus at the 5 antigenic sites reported to be important and found that these recent seasonal influenza viruses from 2006 and 2008 had similar amino acid sequences at these sites but were quite different from the 2009 pH1N1 virus. Theoretically, it is hard to explain the cross-reactivity between endemic seasonal influenza virus strains and the pH1N1 virus. Study of similarities between these local strains and the 2009 pH1N1 virus at antigenic sites other than the 5 sites reported to be important is needed. Screening of more subjects for cross-reactivity is also warranted in the future.

Because antibody-mediated immunity plays a key role in protection against influenza infection, the presence of preexisting antibodies reflects the variance of disease incidence in different age populations. According to Taiwan CDC estimates, the peak age-specific incidence of 2009 pH1N1 virus-related hospitalization occurred in children less than 6 years old (1.1 to 1.3/10,000 population), in contrast to 0.25/10,000 populations for people more than 65 years old (http://flu.cdc.gov.tw/mp.asp?mp=151). This finding is consistent with the observed presence of preexisting cross-reactive antibodies in the elder population. However, with regard to disease severity, the incidence of clinically severe cases so far appears to be similar to that experienced for seasonal flu. In Taiwan, 41 patients died of 2009 pH1N1 virus infection (1.78/1 million population), and most of them were obese, pregnant, or affected by underlying diseases and thus were considered immunocompromised on some level. Previous studies demonstrated that in contrast to the B-cell antibody response, T-cell immunity contributes to the clearance of infected target cells and the lessening of disease severity (11, 12, 15, 17). In a recent study of preexisting immunity to the 2009 pH1N1 viruses in the general human population (6), the authors found that the new 2009 H1N1 virus conserves a large fraction of T-cell epitopes from seasonal influenza viruses, which may explain the relatively mild nature and course of disease of the 2009 pH1N1 virus compared to that of previous seasonal H1N1 influenza infections.

It is clear that optimal protection against the 2009 pH1N1 virus in a population will be achieved with the administration of a strain-specific vaccine. An influenza vaccination program against the 2009 pH1N1 virus was started in Taiwan in November 2009, and the vaccine coverage rate was about 24% of the entire population as of 13 January 2010. The current epidemiological evidence shows that viral activity has declined in Taiwan since January 2010. However, there is uncertainty as to whether additional generalized waves of activity might occur in future months. Our findings add to information supporting the evidence for antibody protection against diseases and the importance of vaccination. Meanwhile, continuation of surveillance and analyses of H1N1 isolates from patients with respiratory illness is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-ID-099-SP10/04 and NHRI-ID-099-PP12) and National Science Council (NSC-98-2321-B-006-007).

We thank Chao-Ping Liao for collecting the serum samples.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 September 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009. Serum cross-reactive antibody response to a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus after vaccination with seasonal influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58:521-524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen, J., and M. Enserink. 2009. Swine flu. After delays, WHO agrees: the 2009 pandemic has begun. Science 324:1496-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawood, F. S., S. Jain, L. Finelli, M. W. Shaw, S. Lindstrom, R. J. Garten, L. V. Gubareva, X. Xu, C. B. Bridges, and T. M. Uyeki. 2009. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:2605-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garten, R. J., C. T. Davis, C. A. Russell, B. Shu, S. Lindstrom, A. Balish, W. M. Sessions, X. Xu, E. Skepner, V. Deyde, M. Okomo-Adhiambo, L. Gubareva, J. Barnes, C. B. Smith, S. L. Emery, M. J. Hillman, P. Rivailler, J. Smagala, M. de Graaf, D. F. Burke, R. A. Fouchier, C. Pappas, C. M. Alpuche-Aranda, H. Lopez-Gatell, H. Olivera, I. Lopez, C. A. Myers, D. Faix, P. J. Blair, C. Yu, K. M. Keene, P. D. Dotson, Jr., D. Boxrud, A. R. Sambol, S. H. Abid, K. St George, T. Bannerman, A. L. Moore, D. J. Stringer, P. Blevins, G. J. Demmler-Harrison, M. Ginsberg, P. Kriner, S. Waterman, S. Smole, H. F. Guevara, E. A. Belongia, P. A. Clark, S. T. Beatrice, R. Donis, J. Katz, L. Finelli, C. B. Bridges, M. Shaw, D. B. Jernigan, T. M. Uyeki, D. J. Smith, A. I. Klimov, and N. J. Cox. 2009. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science 325:197-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Influenza Programme, World Health Organization. 2002. WHO manual on animal influenza diagnosis and surveillance. WHO/CDS/CSR/NCS/2002.5, rev. 1.World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/influenza/WHO_manual_on_animal-diagnosis_and_surveillance_2002_5.pdf.

- 6.Greenbaum, J. A., M. F. Kotturi, Y. Kim, C. Oseroff, K. Vaughan, N. Salimi, R. Vita, J. Ponomarenko, R. H. Scheuermann, A. Sette, and B. Peters. 2009. Pre-existing immunity against swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses in the general human population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:20365-20370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hancock, K., V. Veguilla, X. Lu, W. Zhong, E. N. Butler, H. Sun, F. Liu, L. Dong, J. R. DeVos, P. M. Gargiullo, T. L. Brammer, N. J. Cox, T. M. Tumpey, and J. M. Katz. 2009. Cross-reactive antibody responses to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 361:1945-1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh, Y. H. 2009. Excess deaths and immunoprotection during 1918-1920 influenza pandemic, Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1617-1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itoh, Y., K. Shinya, M. Kiso, T. Watanabe, Y. Sakoda, M. Hatta, Y. Muramoto, D. Tamura, Y. Sakai-Tagawa, T. Noda, S. Sakabe, M. Imai, Y. Hatta, S. Watanabe, C. Li, S. Yamada, K. Fujii, S. Murakami, H. Imai, S. Kakugawa, M. Ito, R. Takano, K. Iwatsuki-Horimoto, M. Shimojima, T. Horimoto, H. Goto, K. Takahashi, A. Makino, H. Ishigaki, M. Nakayama, M. Okamatsu, K. Takahashi, D. Warshauer, P. A. Shult, R. Saito, H. Suzuki, Y. Furuta, M. Yamashita, K. Mitamura, K. Nakano, M. Nakamura, R. Brockman-Schneider, H. Mitamura, M. Yamazaki, N. Sugaya, M. Suresh, M. Ozawa, G. Neumann, J. Gern, H. Kida, K. Ogasawara, and Y. Kawaoka. 2009. In vitro and in vivo characterization of new swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Nature 460:1021-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilbourne, E. D. 1997. Perspectives on pandemics: a research agenda. J. Infect. Dis. 176(Suppl. 1):S29-S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McElhaney, J. E., D. Xie, W. D. Hager, M. B. Barry, Y. Wang, A. Kleppinger, C. Ewen, K. P. Kane, and R. C. Bleackley. 2006. T cell responses are better correlates of vaccine protection in the elderly. J. Immunol. 176:6333-6339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMichael, A. J., F. M. Gotch, G. R. Noble, and P. A. Beare. 1983. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to influenza. N. Engl. J. Med. 309:13-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson, M. I., C. Viboud, L. Simonsen, R. T. Bennett, S. B. Griesemer, K. St George, J. Taylor, D. J. Spiro, N. A. Sengamalay, E. Ghedin, J. K. Taubenberger, and E. C. Holmes. 2008. Multiple reassortment events in the evolutionary history of H1N1 influenza A virus since 1918. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann, G., T. Noda, and Y. Kawaoka. 2009. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature 459:931-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rimmelzwaan, G. F., and J. E. McElhaney. 2008. Correlates of protection: novel generations of influenza vaccines. Vaccine 26(Suppl. 4):D41-D44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell, C. A., T. C. Jones, I. G. Barr, N. J. Cox, R. J. Garten, V. Gregory, I. D. Gust, A. W. Hampson, A. J. Hay, A. C. Hurt, J. C. de Jong, A. Kelso, A. I. Klimov, T. Kageyama, N. Komadina, A. S. Lapedes, Y. P. Lin, A. Mosterin, M. Obuchi, T. Odagiri, A. D. Osterhaus, G. F. Rimmelzwaan, M. W. Shaw, E. Skepner, K. Stohr, M. Tashiro, R. A. Fouchier, and D. J. Smith. 2008. The global circulation of seasonal influenza A (H3N2) viruses. Science 320:340-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webby, R. J., S. Andreansky, J. Stambas, J. E. Rehg, R. G. Webster, P. C. Doherty, and S. J. Turner. 2003. Protection and compensation in the influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:7235-7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]