Abstract

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter spp. has been a growing public health concern globally. The objectives of this study were to determine the prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility, and genetic relatedness of Campylobacter spp. recovered by the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) retail meat program. Retail meat samples (n = 24,566) from 10 U.S. states collected between 2002 and 2007, consisting of 6,138 chicken breast, 6,109 ground turkey, 6,171 ground beef, and 6,148 pork chop samples, were analyzed. A total of 2,258 Campylobacter jejuni, 925 Campylobacter coli, and 7 Campylobacter lari isolates were identified. Chicken breast samples showed the highest contamination rate (49.9%), followed by ground turkey (1.6%), whereas both pork chops and ground beef had <0.5% contamination. The most common resistance was to doxycycline/tetracycline (46.6%), followed by nalidixic acid (18.5%), ciprofloxacin (17.4%), azithromycin and erythromycin (2.8%), telithromycin (2.4%), clindamycin (2.2%), and gentamicin (<0.1%). In a subset of isolates tested, no resistance to meropenem and florfenicol was seen. C. coli isolates showed higher resistance rates to antimicrobials, with the exception of doxycycline/tetracycline, than those seen for C. jejuni. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) fingerprinting resulted in 1,226 PFGE profiles among the 2,318 isolates, with many clones being widely dispersed throughout the 6-year sampling period.

Campylobacter is a leading bacterial cause of food-borne diarrheal illness worldwide, with more than two million cases each year in the United States alone (1, 24). Raw or undercooked poultry has long been recognized as a major source of infection, but other sources, such as beef, pork, lamb, milk, water, and seafood, also have been associated with Campylobacter infections (8, 14, 16, 18). Although Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli cause indistinguishable diarrheal illness, C. jejuni accounts for more than 90% of human campylobacteriosis cases in the United States (8). C. jejuni has been identified as a predominant bacterial cause of Guillain-Barré syndrome and reactive arthritis (3). Campylobacter enteritis is usually self-limiting and does not require antimicrobial therapy. In severe and prolonged cases of enteritis, or cases of bacteremia, septic arthritis, and other extraintestinal infections, erythromycin (ERY) or a fluoroquinolone is the drug of choice (10, 34). In some regions, tetracycline (TET) or doxycycline (DOX) and select beta-lactams have been used for treating intestinal infections. Gentamicin (GEN), meropenem (MER), clindamycin (CLI), telithromycin (TEL), and azithromycin (AZI) show potent in vitro activity and may have potential value as alternative treatments (21).

The use of antimicrobials in food animals and their role in promoting resistance in food-borne pathogens are subjects of an ongoing debate. Several studies have shown that human infections with fluoroquinolone-resistant (FQr) Campylobacter have increased worldwide, coinciding with the approval of fluoroquinolones in animal husbandry (7, 9, 11, 15, 30, 32). In the United States, sarafloxacin was introduced for food animals in 1995 and enrofloxacin in 1996. Approximately 12% of C. jejuni isolates from human cases of infection were resistant to ciprofloxacin (CIP) in 1997, 21% were resistant in 2002, and 26% were resistant in 2007, whereas no isolates were resistant to CIP in 1989 and 1990, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study (11). In other countries, including Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Netherland, Italy, Spain, and Thailand, and in the United Kingdom, infection by FQr Campylobacter showed an increase following the introduction of fluoroquinolones for food animals (7).

The increased international attention to the risk of antibiotic use in animal production helped spur the development of numerous surveillance systems and networks (37). In the United States, the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) monitors antimicrobial resistance of food-borne pathogens and identifies the source and magnitude of antimicrobial resistance in the food supply. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility, and genetic relatedness of Campylobacter strains isolated from fresh retail meat purchased in the United States between 2002 and 2007.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retail meat sampling.

Retail meat samples were purchased at retail outlets and cultured for Campylobacter at the CDC Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) sites. Each FoodNet site obtained up to 40 retail meats per month: 10 samples (each) of chicken breast with skin on, ground turkey, ground beef, and pork chops from grocery stores. Six FoodNet sites participated in 2002 (CT, GA, MD, MN, OR, and TN), and two additional sites were added in 2003 (CA and NY) and 2004 (NM and CO). FoodNet sites used a convenience sampling approach from 2002 to 2004 in which samples were collected from grocery stores in close proximity to the health department, with the goal to purchase as many different brands of fresh meat and poultry as possible. A stratified random-sampling scheme was instituted in 2005, whereby samples were collected from a geocoded list of grocery stores within zip codes representing highly populated areas for each site. The zip codes were partitioned into quadrants, and grocery stores were randomly selected for sample collection using SAS software, version 9.1.3. For each sample, the FoodNet sites logged the store name, lot number (if available), sell-by date, purchase date, and laboratory processing date. Samples were kept cold during transport from the grocery store(s) to the laboratory before being tested. For chicken breast and pork chop samples, one piece of meat was examined, and for ground beef and ground turkey, 25-g portions of meat were analyzed.

Microbiological analysis.

Each sample was placed in a separate sterile plastic bag with 250 ml of buffered peptone water (Fisher Scientific, Inc.). After vigorous shaking, 50 ml of the rinsate was transferred to a sterile flask for isolation and identification of Campylobacter spp. Fifty milliliters of double-strength Bolton broth (Oxoid, Cambridge, United Kingdom) was added to the 50 ml of rinsate and mixed thoroughly, and the mixture was incubated at 42°C for 24 h using gas-generating kits (Campy Pak; BBL-Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) or a compressed gas mixture containing 85% nitrogen, 10% carbon dioxide, and 5% oxygen. By using a swab, the first quadrant of a Campy Cefex agar (CCA; Remel, Lenexa, KS) plate was inoculated with the incubated Bolton broth culture. The remainder of each plate was streaked with a loop to obtain isolated colonies, and the CCA plates were incubated at 42°C in the above-mentioned atmosphere for 24 to 48 h. A single well-isolated colony from each CCA plate was subcultured to a blood agar plate (BAP) and incubated as described for the CCA plates. Isolates were examined by Gram staining and tested for catalase, oxidase, hippurate activity, and motility. All presumptive Campylobacter isolates were frozen at −80°C in Brucella broth with 20% glycerol. The isolates were further confirmed as Campylobacter by using an AccuProbe Campylobacter identification test (Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA) prior to identification to the species level by multiplex PCR as previously described (19, 36).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The isolates recovered from 2002 to 2003 were tested by agar dilution for susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (CIP), doxycycline (DOX), erythromycin (ERY), gentamicin (GEN), and meropenem (MER). Beginning in 2004, susceptibility was measured by broth microdilution and nine antimicrobials were tested, including CIP, ERY, GEN, tetracycline (TET), azithromycin (AZI), clindamycin (CLI), florfenicol (FFN), nalidixic acid (NAL), and telithromycin (TEL). The methods were controlled using C. jejuni ATCC 33560 per CLSI standards. CLSI interpretive criteria, based on epidemiological cutoff values, are available for CIP (≥4 μg/ml), TET (≥16 μg/ml), ERY (≥32 μg/ml), and DOX (≥8 μg/ml). NARMS resistance breakpoints used for other agents were >8 μg/ml for GEN, >16 μg/ml for MER, >8 μg/ml for AZI, >8 μg/ml for CLI, >64 μg/ml for NAL, and >16 μg/ml for TEL (24). For FFN, only a susceptible breakpoint was used (MIC, <4 μg/ml) due to the absence of a resistant population. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as resistance to ≥2 antimicrobial classes.

PFGE.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed to determine genomic DNA fingerprinting profiles of Campylobacter isolates according to the protocol developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (29). Agarose-embedded DNA was digested with 40 U of SmaI (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) for least 2 h at room temperature. The restriction fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 14°C for 18 h using a Chef Mapper electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with pulse times of 6.76 to 35.38 s. Salmonella enterica serovar Braenderup H9812 was used as the control strain. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide, and DNA bands were visualized by UV transillumination (Bio-Rad). PFGE results were analyzed using BioNumerics software (Applied-Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium), and banding patterns were compared using Dice coefficients with a 1.5% band position tolerance. All Campylobacter isolates recovered from 2002 to 2005 were analyzed with SmaI and KpnI restriction enzymes. For 2006 to 2007 isolates, only Cipr and Eryr isolates were subjected to PFGE analysis using both enzymes. All PFGE patterns were submitted to the CDC PulseNet database.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Cochran-Armitage trend test in SAS. ANOVA was used to test for significant differences in prevalence between the FoodNet sites and differences in resistance between C. coli and C. jejuni. The Cochran-Armitage trend test was used for trend analyses of prevalence and resistance over time.

RESULTS

Campylobacter prevalence.

The number of participating FoodNet sites expanded from six sites in 2002 to 10 sites in 2004 (CA, CO, CT, GA, MD, MN, NM, NY, OR, TN), except for 2007, when MD did not participate. A total of 40 retail meat samples were purchased per month, comprised of 10 samples (each) of chicken breast with skin on, ground turkey, ground beef, and pork chops. The types and numbers of retail meats sampled over time were similar between all participating FoodNet sites, with few exceptions (Table 1). Between 2002 and 2007, a total of 24,566 meat samples were examined, consisting of 6,138 chicken breasts, 6,109 ground turkey samples, 6,171 ground beef samples, and 6,148 pork chops.

TABLE 1.

Number of retail meat samples tested and prevalence of Campylobacter from 2002 to 2007a

| Type of meat | No. of samples tested in year indicated (% prevalence of Campylobacter) |

Total no. of samples (% prevalence) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | ||

| Chicken breast | 616 (46.8) | 897 (52.3) | 1,172 (60.2) | 1,190 (46.6) | 1,193 (47.9) | 1,070 (44.4) | 6,138 (49.9) |

| Ground turkey | 642 (0.6) | 857 (0.6) | 1,165 (1.0) | 1,195 (1.7) | 1,185 (2.0) | 1,065 (3.2) | 6,109 (1.6) |

| Ground beef | 642 (0) | 880 (0.1) | 1,186 (0) | 1,196 (0) | 1,196 (0) | 1,071 (0.5) | 6,171 (0.1) |

| Pork chop | 613 (0.8) | 899 (0.4) | 1,176 (0.3) | 1,196 (0.2) | 1,192 (0.3) | 1,072 (0.4) | 6,148 (0.3) |

| Total | 2,513 (11.8) | 3,533 (13.6) | 4,699 (15.3) | 4,777 (12.1) | 4,766 (12.6) | 4,278 (12.1) | 24,566 (13.0) |

There were 6 states participating in the NARMS retail meat program in 2002, 8 states in 2003, 10 states in 2004 to 2006, and 9 states in 2007.

Overall, 13% (n = 3,190) of 24,566 retail meat samples were positive for Campylobacter, with the majority of the isolates having been recovered from chicken breasts (n = 3,964; 49.9%) followed by ground turkey samples (n = 99, 1.6%). Campylobacter was rarely recovered from pork chops (n = 20; 0.3%) and ground beef samples (n = 6; 0.1%) (Table 1). The numbers of Campylobacter isolates were 2,258 for C. jejuni, 925 for C. coli, and 7 for C. lari (Table 2). Over the 6 years, there were no significant differences in the Campylobacter isolation rate by month within a test area, although some months had slightly higher isolation rates than others (data not shown). There were significant differences in Campylobacter isolation rates between the FoodNet sites (P < 0.05), ranging from 0.6% to 20.8%. Over the testing time period, CA maintained the highest positive isolation rate, with an average of 18.5%, whereas NM had the lowest positive isolation rate, with an average of 8.4% (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Campylobacter species identified from retail meats, 2002 to 2007a

| Meat type | Species | No. of samples testing positive for Campylobacter in year indicated |

Total no. of samples testing positive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |||

| Chicken breast | C. jejuni | 198 | 325 | 510 | 403 | 426 | 332 | 2,194 |

| C. coli | 90 | 142 | 196 | 151 | 145 | 143 | 867 | |

| C. lari | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| Total | 288 | 469 | 706 | 554 | 572 | 475 | 3,064 | |

| Ground turkey | C. jejuni | 2 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 20 | 55 |

| C. coli | 2 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 41 | |

| C. lari | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Total | 4 | 5 | 12 | 20 | 24 | 34 | 99 | |

| Ground beef | C. jejuni | 1 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| C. coli | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| C. lari | 0 | |||||||

| Total | 1 | 5 | 6 | |||||

| Pork chop | C. jejuni | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| C. coli | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 6 | ||

| C. lari | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Total | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 21 | |

The total number of meat samples tested (24,566) for Campylobacter between 2002 and 2007 includes the following: chicken breast (n = 6,138), ground turkey (n = 6,109), ground beef (n = 6,171), and pork chop (n = 6,148).

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

For susceptibility testing, the CLSI-approved agar dilution susceptibility testing method was replaced by a broth microdilution method in 2004, when a standardized broth method was developed (22) and approved by the CLSI (6). A comparison of 300 Campylobacter strains showed that the two methods showed a 96 to 100% correlation for CIP, ERY, and GEN (data not shown). For TET, for which the bimodal MIC distributions are less distinct, the correlation was 77 to 91% (data not shown).

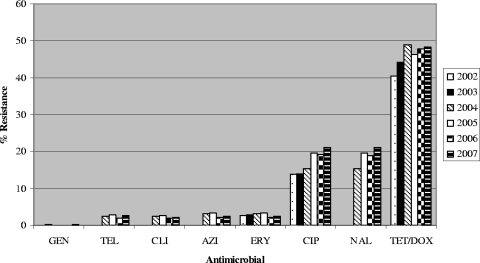

Campylobacter isolates displayed resistance most frequently to DOX/TET (40.4 to 48.3%), followed by NAL (15.4 to 21%), CIP (13.8 to 21%), ERY and AZI (2.2 to 3.3%), TEL (1.8 to 2.8%), CLI (1.8 to 2.6%), and GEN (0 to 0.2%) (Fig. 1). All isolates that were tested were susceptible to MER and FFN. Since chicken breast samples had the highest contamination rate, levels of resistance to different antimicrobials and resistance trends for C. jejuni and C. coli isolates from chicken breast were compared.

FIG. 1.

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Campylobacter isolates recovered from retail meats, 2002 to 2007. From 2002 to 2003, isolates were tested by agar dilution using ciprofloxacin (CIP), doxycycline (DOX), erythromycin (ERY), gentamicin (GEN), and meropenem (MER). From 2004 to 2007, testing was done by broth microdilution using CIP, ERY, GEN, tetracycline (TET), azithromycin (AZI), clindamycin (CLI), florfenicol (FFN), nalidixic acid (NAL), and telithromycin (TEL). A total of 3,190 Campylobacter isolates were tested, including 297 in 2002, 479 in 2003, 721 in 2004, 576 in 2005, 599 in 2006, and 518 in 2007.

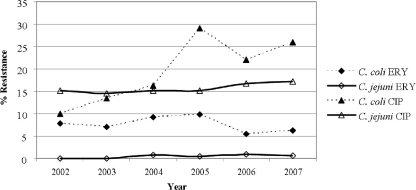

In a comparison of isolates from chicken meat, C. coli displayed greater resistance than C. jejuni to all antimicrobials except DOX/TET, for which resistance levels were similar for C. jejuni (46.2%) and C. coli (45.2%) (data not shown). Overall, C. coli resistance levels for CLI, TEL, AZI, and ERY are statistically significantly higher than those for C. jejuni (P < 0.05). In a comparison of the trends in resistance to ERY and CIP over the years, resistance to ERY was consistently low. For C. jejuni, resistance was between 0.0% and 0.9%, and for C. coli, resistance was between 5.5% and 9.9%; resistance to CIP increased mainly for C. coli, from 10% in 2002 to 25.9% in 2007 (P < 0.0001). For C. jejuni, there was a slight increase from 15.2% in 2002 to 17.2% in 2007 (P = 0.2858) (Fig. 2). Resistance trends for isolates from other sources could not be evaluated due to low numbers. However, C. jejuni and C. coli isolated from ground turkey tended to show higher levels of resistance to CIP, NAL, and DOX/TET than did isolates from chicken (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Erythromycin and ciprofloxacin resistance among C. jejuni and C. coli isolates from chicken breasts by year, 2002 to 2007. The 3,064 Campylobacter isolates tested included 2,194 C. jejuni, 867 C. coli, and 3 C. lari isolates. The numbers of isolates by year were 288 in 2002, 469 in 2003, 706 in 2004, 554 in 2005, 572 in 2006, and 475 in 2007.

Overall, 45.4% of Campylobacter isolates were pansusceptible (47.3% of C. jejuni and 40.6% of C. coli isolates). Resistance to ≥2 antimicrobials was detected for 13.8% of C. jejuni and 25.7% of C. coli isolates. More than 99% of Nalr isolates were also Cipr, and all Eryr isolates were Azir. In addition, >94% of isolates showed cross-resistance to CLI and TEL. The top five MDR profiles were CIP/NAL-TET (n = 248), AZI/ERY-CLI-TEL (n = 30), AZI/ERY-CLI-TEL-TET (n = 20), AZI/ERY-TET (n = 10), and AZI/ERY-CIP/NAL-TET (n = 6) (Table 3). C. coli was resistant to more antimicrobials with more diverse resistance profiles than C. jejuni. There were four isolates (one C. jejuni isolate from ground turkey and three C. coli isolates, one from ground turkey and two from chicken breast) that showed resistance to five of the seven antimicrobial classes tested, including quinolones, tetracyclines, ketolides, lincosamides, and macrolides. The details of MIC distributions for each antimicrobial from 2002 to 2007 are displayed on the Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) website (http://www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/SafetyHealth/AntimicrobialResistance/NationalAntimicrobialResistanceMonitoringSystem/ucm164662.htm).

TABLE 3.

Resistance profiles for C. jejuni and C. coli isolates from retail meatsa

| Resistance profile | No. of samples |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| C. jejuni | C. coli | Total | |

| Pansusceptible | 1,068 | 376 | 1,444 |

| AZI/ERY-TET | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| CIP/NAL-TET | 161 | 87 | 248 |

| AZI/ERY-CIP/NAL-TET | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| AZI/ERY-CLI-TEL | 3 | 27 | 30 |

| AZI/ERY-TEL-TET | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| AZI/ERY-CLI-TEL-TET | 6 | 14 | 20 |

| AZI/ERY-CIP/NAL-TEL-TET | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| AZI/ERY-CIP/NAL-CLI-TEL-TET | 1 | 3 | 4 |

Shown are the numbers of pansusceptible isolates and the major MDR profiles for C. jejuni and C. coli isolates from retail meats. Cases in which there was resistance to ≥2 antimicrobial classes with ≥3 isolates are shown. The five antimicrobials tested from 2002 to 2003 were ciprofloxacin (CIP), doxycycline (DOX), erythromycin (ERY), gentamicin (GEN), and meropenem (MER). The nine antimicrobials tested from 2004 to 2007 were CIP, ERY, GEN, tetracycline (TET), azithromycin (AZI), clindamycin (CLI), florfenicol (FFN), nalidixic acid (NAL), and telithromycin (TEL).

PFGE profiles.

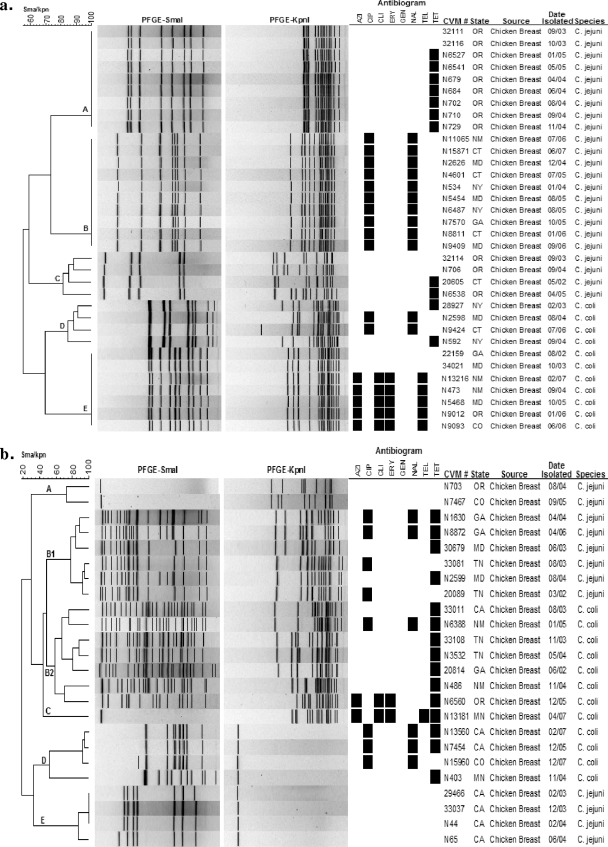

PFGE was used to assess the genetic relatedness of strains. Genomic DNA digestion with SmaI generated 827 PFGE profiles, and further analysis combined with KpnI produced 1,226 PFGE profiles (data not shown). Adding a second enzyme for PFGE analysis significantly increased PFGE discriminatory power (Fig. 3a, clusters C and D). Even with double-enzyme analysis, there were some clones (Fig. 3a, clusters B and E) that were repeatedly isolated from different states throughout the sampling years. Other clones were seen only in particular states (Fig. 3a, clone A). Additionally, a small portion of isolates of both C. jejuni and C. coli could not be cut by SmaI or KpnI alone (Fig. 3b, clusters A, C, D, and E), perhaps due to DNA methylation. Approximately 26 C. jejuni and 20 C. coli isolates showed unusual PFGE patterns with multiple high-molecular-weight bands with SmaI digestions (Fig. 3b, clusters B1 and B2), which added up approximately to a doubled genome size. This perhaps is due to the presence of two genetically different strains of Campylobacter in the culture, which resist separation by subculturing (25). The PFGE profiles showed a good correlation with Campylobacter species, excepting those with unusual PFGE patterns or no enzyme digestion (Fig. 3a and b).

FIG. 3.

SmaI/KpnI PFGE profiles for selected C. jejuni and C. coli clones (a) and uncommon PFGE profiles for C. jejuni and C. coli (b).

Some PFGE profiles of Campylobacter isolates showed a good correlation with their antimicrobial resistance profiles. For instance, all 10 isolates in clone B (Fig. 3a) were Cipr and Nalr, and four isolates in cluster E (Fig. 3b) were susceptible to all antimicrobials tested. However, some other clones/clusters had less correlation between PFGE results and resistance profiles. For example, clones/clusters A, C, and E in Fig. 3a contain both resistance and susceptible strains, and clusters B1, B2, and D in Fig. 3b have isolates with different resistance profiles.

DISCUSSION

We report the prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility, and PFGE data for Campylobacter isolates generated over a 6-year sampling interval of the NARMS retail meat program. Campylobacter was recovered mainly from chicken breast samples (50%), and most isolates (70.8%) were C. jejuni. A more limited survey of meats collected around the Washington, DC, area in 1999 to 2000 (36) found Campylobacter in chicken (70%), turkey (14.5%), pork (1.7%), and beef (0.5%) samples. These differences may be due to the fact that three to five presumptive colonies were selected from the primary isolation medium; also, whole chicken carcasses rather than breasts, and turkey breast rather than ground meat, were tested in that study. Various recovery rates are reported in other studies from the United States and abroad, but all have demonstrated a higher contamination rate in chicken than in turkey, pork, and beef retail products (2, 12, 27, 32, 36).

We did not observe a significant difference in the prevalence of Campylobacter by month; however, there were statistically significant differences in the positive isolation rate (P < 0.05) among the 10 FoodNet laboratories. California had the highest isolation rate, averaging 18.5% over the 6-year sampling period, whereas New Mexico had the lowest, with an average prevalence of 8.4%. Interestingly, the 2009 FoodNet report showed that California also had the highest incidence of campylobacteriosis cases in the country (5).

Susceptibility testing of chicken isolates showed that resistance to macrolides (AZI, ERY), TEL, CLI, and GEN remained at <1% for C. jejuni and <10% for C. coli, with no significant changes over the 6 years of testing. Resistance to TET/DOX increased from 38.4% in 2002 to 48.6% in 2007 for C. jejuni and decreased from 44.4% in 2002 to 39.9% in 2007 for C. coli. In contrast, resistance to quinolones increased mainly for C. coli, for which Cipr rose from 10% to 25.9% (P < 0.0001), compared with a slight increase of from 15.2% to 17.2% (P = 0.2858) for C. jejuni. Similar observations have been reported for human clinical isolates of Campylobacter, where Cipr was 20.7% in 2002 and 25.8% in 2007 among C. jejuni isolates, compared with 12% in 2002 and 28.6% in 2007 among C. coli isolates (4).

Overall, C. coli showed a greater prevalence of resistance to all antimicrobials than C. jejuni except for DOX/TET. Similar data were reported for chicken abattoir and human isolates (26). High occurrences of resistant C. jejuni and C. coli in retail meats have also been reported from other U.S. studies as well as those from other countries (4, 13, 30, 31). Ge et al. (9) examined 378 Campylobacter isolates from retail meats and found that 35% of isolates were Cipr. Smith et al. (32) reported that 20% of Campylobacter spp. isolated from chicken from Minnesota retailers between 1992 and 1998 were resistant to CIP. A survey study in northeastern Italy by Pezzotti et al. (28) showed that C. coli and C. jejuni isolated from chicken meats showed a higher resistance to quinolones (79% and 53%, respectively) than isolates from other meat types. A recent report from Canada (16) showed that Cipr was significantly more frequent in human isolates acquired abroad than in those acquired domestically (50% versus 5.9%), while Tetr was more common in chicken and human isolates acquired locally (58.9% and 45.8%, respectively). In addition, Eryr was significantly higher in chicken isolates than human, water, and raw milk isolates (16).

The development of resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones is of particular concern since these antimicrobials are advocated as first- and second-line therapies for treating Campylobacter infections. Since these infections are largely food-borne, the role of food animal antibiotic use in promoting the spread of resistant Campylobacter through the food chain is under continuous scrutiny. Numerous reports worldwide associate fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter infections with the approval of fluoroquinolone use in poultry production (7, 9, 11, 15, 30, 32). To combat the emergence of FQr Campylobacter in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration withdrew the approval for the use of the fluoroquinolone enrofloxacin in poultry in September 2005. The use of the fluoroquinolone sarafloxacin in poultry was previously withdrawn voluntarily from the market in April 2001 in response to safety questions raised by FDA. Following these withdrawals, Cipr has remained stable or increased slightly overall (P = 0.7549). Interestingly, Cipr Enterococcus isolated from the same chicken breasts as those in which Campylobacter was found declined from 23.2% in 2005 to 11.5% in 2007, while the presence of Nalr Escherichia coli in the same chicken breasts dropped from 6.6% in 2005 to 3.0% in 2007 (26), implying that the different species respond very differently to the change in selection pressure.

Previous work in our laboratories (23) showed that the use of fluoroquinolones specific for veterinary use in chickens generated a rapid increase in the MIC of CIP for C. jejuni, from 0.25 μg/ml to 32 μg/ml, and that this increase appeared within the treatment time frame and persisted throughout the production cycle. In addition, a study by Luo et al. (20) showed that certain FQr Campylobacter isolates could out-compete the majority of isogenic susceptible strains in in vivo challenge assays, indicating that resistant Campylobacter isolates may have a colonization advantage in the chicken host. This study also showed that prolonged colonization in vivo did not lead to reversion or loss of the specific gyrA mutation conferring this advantage (20). The relationship between resistance and host colonization is not fully understood, but the apparent advantage of strains with gyrA mutations might help explain the persistence of Cipr in Campylobacter since the approvals for fluoroquinolones in poultry were withdrawn.

Because of the genomic diversity of Campylobacter spp., there is no agreement on the optimal typing method for determining strain relatedness. Currently, PFGE is a preferred method for outbreak investigations, while multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is being investigated for its advantages in making evolutionary comparisons. At NARMS, we continue to employ PFGE to characterize isolates at the genomic level, where PFGE correlated well with species. As shown by others (33, 35, 38), the use of a second enzyme increases the discriminatory power of PFGE. This is particularly important for outbreak investigations and for tracing etiologic agents to their sources, especially for isolates that do not cut with SmaI. Despite the diversity of Campylobacter spp., some clones can persist in the meat supply. Our PFGE data showed that several clones repeatedly contaminated the same meat product, in some instances being distributed among different retail outlets in the same state over the 6-year survey. Other clones were detected among different brands and store chains in several states. Such data could provide critical information for determining where contamination may originate. Recently, Lienau et al. (17) reported that PFGE was used successfully to trace flock-related Campylobacter clones in Germany from the farm through slaughter to the final products. Some clones in the flocks during primary production were also recovered from carcasses at different stages throughout processing to the final products, whereas others were seen only in the carcasses after air chilling. These studies support the application of PFGE in epidemiological investigations and the use of a second enzyme, such as KpnI, to confirm the genetic relatedness of Campylobacter isolates. Our PFGE data also showed that some PFGE profiles have a good correlation with their resistance profiles, which could strengthen the utility of molecular subtyping for monitoring and tracking the MDR clones from “farm to fork.”

In summary, our results demonstrated a high prevalence of tetracycline and quinolone resistance in Campylobacter isolates recovered from retail chicken meat. Because retail meats represent a point of exposure close to the consumer, monitoring the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among food-borne pathogens from such commodities is particularly important to public health. The integration of susceptibility data with PFGE analysis by the NARMS and PulseNet programs in the United States is important in understanding emerging MDR food-borne pathogens and the manner of MDR pathogen dissemination in the animal production environment, retail foods, and humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank the CDC and all FoodNet sites for their contributions to the NARMS retail meat program. We also thank David White and William Flynn for their critical reviews and comments in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 October 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allos, B. M. 2001. Campylobacter jejuni infections: update on emerging issues and trends. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1201-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atanassova, V., and C. Ring. 1999. Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in poultry and poultry meat in Germany. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 51:187-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser, M. J. 1997. Epidemiologic and clinical features of Campylobacter jejuni infections. J. Infect. Dis. 176(Suppl. 2):S103-S105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. 2008. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System: enteric bacteria, 2007. Human isolates final report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA.

- 5.CDC. 2010. Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food—10 states, 2009. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 59:418-422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently-isolated or fastidious bacteria; approved guideline. CLSI document M45-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 7.Engberg, J., F. M. Aarestrup, D. E. Taylor, P. Gerner-Smidt, and I. Nachamkin. 2001. Quinolone and macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli: resistance mechanisms and trends in human isolates. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:24-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman, C. R., J. Neimann, H. C. Wegener, and R. V. Tauxe. 2000. Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections in the United States and other industrialized nations, p. 121-135. In I. Nachamkin and M. J. Blaser (ed.), Campylobacter, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 9.Ge, B., D. G. White, P. F. McDermott, W. Girard, S. Zhao, S. Hubert, and J. Meng. 2003. Antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter species from retail raw meats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3005-3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerrant, R. L., T. Van Gilder, T. S. Steiner, N. M. Thielman, L. Slutsker, R. V. Tauxe, T. Hennessy, P. M. Griffin, H. DuPont, R. B. Sack, P. Tarr, M. Neill, I. Nachamkin, L. B. Reller, M. T. Osterholm, M. L. Bennish, and L. K. Pickering. 2001. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:331-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta, A., J. M. Nelson, T. J. Barrett, R. V. Tauxe, S. P. Rossiter, C. R. Friedman, K. W. Joyce, K. E. Smith, T. F. Jones, M. A. Hawkins, B. Shiferaw, J. L. Beebe, D. J. Vugia, T. Rabatsky-Ehr, J. A. Benson, T. P. Root, and F. J. Angulo. 2004. Antimicrobial resistance among Campylobacter strains, United States, 1997-2001. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1102-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hariharan, H., T. Wright, and J. R. Long. 1990. Isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni from slaughter hogs. Microbiologica 13:1-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Igimi, S., Y. Okade, A. Ishiwa, M. Yamasaki, N. Morisaki, Y. Kubo, H. Asakura, and S. Yamamoto. 2008. Antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter: prevalence and trends in Japan. Food Addit. Contam. 2008:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs-Reitsma, W. 2000. Campylobacter in the food supply, p. 467-482. In I. Nachamkin and M. J. Blaser (ed.), Campylobacter, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 15.Kinana, A. D., E. Cardinale, F. Tall, I. Bahsoun, J. M. Sire, B. Garin, S. Breurec, C. S. Boye, and J. D. Perrier-Gros-Claude. 2006. Genetic diversity and quinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolates from poultry in Senegal. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3309-3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levesque, S., E. Frost, and S. Michaud. 2007. Comparison of antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from humans, chickens, raw milk, and environmental water in Quebec. J. Food Prot. 70:729-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lienau, J. A., L. Ellerbroek, and G. Klein. 2007. Tracing flock-related Campylobacter clones from broiler farms through slaughter to retail products by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Food Prot. 70:536-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindmark, H., S. Boqvist, M. Ljungstrom, P. Agren, B. Bjorkholm, and L. Engstrand. 2009. Risk factors for campylobacteriosis: an epidemiological surveillance study of patients and retail poultry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2616-2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linton, D., A. J. Lawson, R. J. Owen, and J. Stanley. 1997. PCR detection, identification to species level, and fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli direct from diarrheic samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2568-2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo, N., S. Pereira, O. Sahin, J. Lin, S. Huang, L. Michel, and Q. Zhang. 2005. Enhanced in vivo fitness of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:541-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDermott, P. 2010. Campylobacter. In P. Courvalin, R. Leclercq, and L. B. Rice (ed.), Antibiogram. ESKA Publishing, Portland, OR.

- 22.McDermott, P. F., S. M. Bodeis-Jones, T. R. Fritsche, R. N. Jones, and R. D. Walker. 2005. Broth microdilution susceptibility testing of Campylobacter jejuni and the determination of quality control ranges for fourteen antimicrobial agents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:6136-6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDermott, P. F., S. M. Bodeis, L. L. English, D. G. White, R. D. Walker, S. Zhao, S. Simjee, and D. D. Wagner. 2002. Ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter jejuni evolves rapidly in chickens treated with fluoroquinolones. J. Infect. Dis. 185:837-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mead, P. S., L. Slutsker, V. Dietz, L. F. McCaig, J. S. Bresee, C. Shapiro, P. M. Griffin, and R. V. Tauxe. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:607-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller, W. G., A. H. Bates, S. T. Horn, M. T. Brandl, M. R. Wachtel, and R. E. Mandrell. 2000. Detection on surfaces and in Caco-2 cells of Campylobacter jejuni cells transformed with new gfp, yfp, and cfp marker plasmids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5426-5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS). NARMS 2006 executive report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Laurel, MD.

- 27.Ono, K., and K. Yamamoto. 1999. Contamination of meat with Campylobacter jejuni in Saitama, Japan. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 47:211-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pezzotti, G., A. Serafin, I. Luzzi, R. Mioni, M. Milan, and R. Perin. 2003. Occurrence and resistance to antibiotics of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in animals and meat in northeastern Italy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 82:281-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribot, E. M., C. Fitzgerald, K. Kubota, B. Swaminathan, and T. J. Barrett. 2001. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for subtyping of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1889-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serichantalergs, O., A. Dalsgaard, L. Bodhidatta, S. Krasaesub, C. Pitarangsi, A. Srijan, and C. J. Mason. 2007. Emerging fluoroquinolone and macrolide resistance of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates and their serotypes in Thai children from 1991 to 2000. Epidemiol. Infect. 135:1299-1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skjot-Rasmussen, L., S. Ethelberg, H. D. Emborg, Y. Agerso, L. S. Larsen, S. Nordentoft, S. S. Olsen, T. Ejlertsen, H. Holt, E. M. Nielsen, and A. M. Hammerum. 2009. Trends in occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolates from broiler chickens, broiler chicken meat, and human domestically acquired cases and travel associated cases in Denmark. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 131:277-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, K. E., J. M. Besser, C. W. Hedberg, F. T. Leano, J. B. Bender, J. H. Wicklund, B. P. Johnson, K. A. Moore, and M. T. Osterholm. 1999. Quinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections in Minnesota, 1992-1998. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:1525-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thakur, S., D. G. White, P. F. McDermott, S. Zhao, B. Kroft, W. Gebreyes, J. Abbott, P. Cullen, L. English, P. Carter, and H. Harbottle. 2009. Genotyping of Campylobacter coli isolated from humans and retail meats using multilocus sequence typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106:1722-1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams, M. D., J. B. Schorling, L. J. Barrett, S. M. Dudley, I. Orgel, W. C. Koch, D. S. Shields, S. M. Thorson, J. A. Lohr, and R. L. Guerrant. 1989. Early treatment of Campylobacter jejuni enteritis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:248-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xi, M., J. Zheng, S. Zhao, E. W. Brown, and J. Meng. 2008. An enhanced discriminatory pulsed-field gel electrophoresis scheme for subtyping Salmonella serotypes Heidelberg, Kentucky, SaintPaul, and Hadar. J. Food Prot. 71:2067-2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao, C., B. Ge, J. De Villena, R. Sudler, E. Yeh, S. Zhao, D. G. White, D. Wagner, and J. Meng. 2001. Prevalence of Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli, and Salmonella serovars in retail chicken, turkey, pork, and beef from the greater Washington, D.C., area. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5431-5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao, S., P. F. McDermott, S. Friedman, J. Abbott, S. Ayers, A. Glenn, E. Hall-Robinson, S. K. Hubert, H. Harbottle, R. D. Walker, T. M. Chiller, and D. G. White. 2006. Antimicrobial resistance and genetic relatedness among Salmonella from retail foods of animal origin: NARMS retail meat surveillance. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3:106-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng, J., C. E. Keys, S. Zhao, J. Meng, and E. W. Brown. 2007. Enhanced subtyping scheme for Salmonella enteritidis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:1932-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]