Abstract

Acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) is a central metabolite in carbon and energy metabolism. Because of its amphiphilic nature and bulkiness, acetyl-CoA cannot readily traverse biological membranes. In fungi, two systems for acetyl unit transport have been identified: a shuttle dependent on the carrier carnitine and a (peroxisomal) citrate synthase-dependent pathway. In the carnitine-dependent pathway, carnitine acetyltransferases exchange the CoA group of acetyl-CoA for carnitine, thereby forming acetyl-carnitine, which can be transported between subcellular compartments. Citrate synthase catalyzes the condensation of oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA to form citrate that can be transported over the membrane. Since essential metabolic pathways such as fatty acid β-oxidation, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and the glyoxylate cycle are physically separated into different organelles, shuttling of acetyl units is essential for growth of fungal species on various carbon sources such as fatty acids, ethanol, acetate, or citrate. In this review we summarize the current knowledge on the different systems of acetyl transport that are operational during alternative carbon metabolism, with special focus on two fungal species: Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans.

Candida albicans is an opportunistic commensal fungus that is part of the normal human microflora. The fungus has colonized the oral cavities of most infants by the age of 1 month (42) and resides in the gastrointestinal tract in the majority of adults (29). Opportunistic infections by C. albicans include invasion of oral and vaginal mucosal surfaces, but alterations in host immunity or physical perturbation (for example, through surgery) can cause invasion of the fungus into the bloodstream, resulting in life-threatening systemic infection. C. albicans seemingly promotes a sustainable commensal life style by negatively regulating its own population size in the gastrointestinal tract (53). During the commensal and pathogenic stages, the fungus encounters different niches in the body that vary widely with respect to physiology, pH, type of immunological defense, and availability of nutrients (3). To be able to survive and develop an infection in vivo, C. albicans needs to adapt to these changing environments. One important aspect of this adaptation is the ability of C. albicans to use a wide variety of carbon sources. Microarray studies have revealed that in plasma and tissue, glucose is the major carbon source (10, 49), whereas during phagocytosis by macrophages or neutrophils, fatty acid β-oxidation and the glyoxylate cycle are highly upregulated (9, 10, 24), suggesting that under the latter conditions the fungus metabolizes alternative carbon sources such as fatty acids. Independent of the carbon source that cells grow on, the C2 unit acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) is a central metabolite that serves as the substrate or product of various metabolic pathways. Acetyl-CoA is essential for the production of ATP, as it is used to replenish the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle with C2 units, and therefore acetyl-CoA supply in the mitochondrial matrix is essential for growth. However, growth on carbon sources other than glucose leads to the production of acetyl-CoA in peroxisomes or the cytosol and therefore requires transport of acetyl units over the organellar membrane(s). In this review we describe the current knowledge on pathways of alternative carbon metabolism in C. albicans, with special focus on the role of carnitine-dependent acetyl unit transport, and highlight major differences in carbon metabolism between this pathogenic fungus and the nonpathogenic model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

GLUCOSE METABOLISM

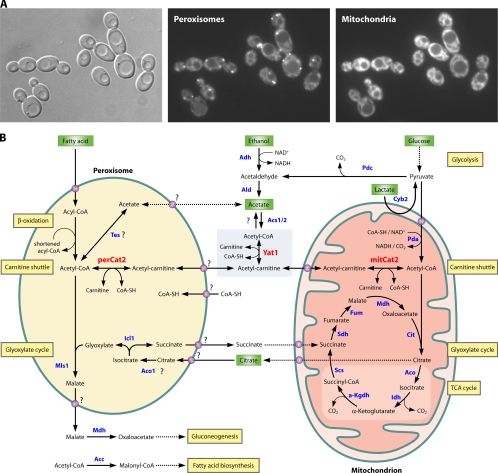

During growth on glucose, fungi can employ two major strategies for energy production: oxidative respiration or nonoxidative fermentation. Both respiration and fermentation employ glycolysis as the central pathway, but the former is more energetically efficient than the latter, as more NAD+ can be produced per molecule of glucose in the presence of oxygen. Most eukaryotes are obligate or facultative aerobes and therefore predominantly employ respiration in the presence of oxygen, while the fermentation pathway is used only in the absence of oxygen. However, it is well established that S. cerevisiae exhibits a unique dependence on the fermentation pathway and therefore ferments sugars to ethanol instead of using respiration, even under aerobic conditions (18). C. albicans, on the other hand is a facultative aerobe and predominantly oxidizes glucose via pyruvate to carbon dioxide through the TCA cycle. Glucose is taken up by the cell and phosphorylated by hexokinase (Hxk1), a reaction that requires ATP, to trap the molecule in the cell. The glucose-6-phosphate formed can enter the catabolic glycolysis where it is degraded to pyruvate, which can be transported over the mitochondrial membrane. The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (Pda), which is associated with the mitochondrial membrane, converts pyruvate into acetyl-CoA that is released in the mitochondrial matrix. Therefore, during growth on glucose, acetyl-CoA is directly synthesized in the mitochondrial matrix, and no transport of acetyl-CoA over the mitochondrial membrane is required (Fig. 1B). In the absence of added sources of acetyl-CoA, however, there is a strict requirement for the production of cytosolic acetyl-CoA, which is essential as a building block for the biosynthesis of fatty acids. In S. cerevisiae and C. albicans, cytosolic acetyl-CoA is synthesized via the pyruvate-acetaldehyde-acetate pathway (Fig. 1B). Of the two acetyl-CoA synthetases that have been identified in these yeast species (ACS1 and ACS2), ACS2 seems to play a major role in the generation of cytosolic acetyl-CoA when glucose is the carbon source (4, 50).

Fig. 1.

Central carbon metabolism in C. albicans. (A) Morphology of peroxisomes and mitochondria in glucose-grown C. albicans cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (POT1/orf19.7520). Peroxisomes were visualized by GFP fluorescence and mitochondria by MitoTracker Red staining. (B) Model for acetyl-CoA transport between peroxisomal, cytosolic, and mitochondrial compartments in C. albicans. Depicted biochemical pathways are β-oxidation of fatty acids, carnitine shuttle, glyoxylate cycle, TCA cycle, glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and fatty acid biosynthesis. Abbreviations: Acc, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; Aco, aconitase; Acs1/2, acetyl-CoA synthase; Adh, alcohol dehydrogenase; Ald, acetaldehyde dehydrogenase; α-Kgdh, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase; Cit, citrate synthase; Cyb2, l-lactate dehydrogenase; Fum, Fumarase; Icl1, isocitrate lyase; Idh, isocitrate dehydrogenase; Mdh, malate dehydrogenase; mitCat2, mitochondrial Cat2; Mls1, malate synthase; Pda, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; Pdc, pyruvate decarboxylase; perCat2, peroxisomal Cat2; Scs, succinyl-CoA synthetase; Sdh, succinate dehydrogenase; Tes, thioesterase; Yat1, carnitine acetyltransferase. •, putative carrier/transporter. Question marks indicate uncertainty about conversions or means of transport. (Adapted from reference 46 with permission of the publisher.)

Transcription factors Tye7 and Gal4 were shown to be the mayor regulators of expression of genes involved in glycolysis in C. albicans (2). Tye7 seems to be the main transcription factor that determines the flux between energy storage and energy production at the glucose-6-phosphate branch point, independently of the carbon source. Gal4, on the other hand bound more targets involved in pyruvate metabolism, and binding was carbon source dependent. The C. albicans tye7 null strain and a tye7/gal4 null strain showed severe growth defects during growth on fermentable carbon sources when respiration was inhibited or oxygen was limited. In addition, the strains showed severe virulence defects in both the Galleria mellonella and mouse intravenous models, showing that proper transcriptional regulation of glycolysis is essential during infection. The authors hypothesized that the virulence defect of the tye7 null and tye7/gal4 null strains is the result of growth defects due to a low-oxygen environment during invasive infection (2).

FATTY ACID β-OXIDATION

In mammals, very-long-chain fatty acids undergo shortening by peroxisomal β-oxidation, while shorter fatty acids are directly imported into mitochondria (20). In yeasts such as S. cerevisiae and C. albicans, fatty acid β-oxidation is exclusively peroxisomal (20). After import into the peroxisome, acyl-CoA is oxidized completely to acetyl-CoA units in four enzymatic steps performed by three different enzymes. The C. albicans genome encodes multiple isozymes for some of the enzymatic steps of β-oxidation (two acyl-CoA oxidases, one multifunctional enzyme, and three 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolases), a complexity that resembles that of the human β-oxidation pathway (three acyl-CoA oxidases, two multifunctional enzymes, and three 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolases) but not that of S. cerevisiae (one acyl-CoA oxidase, one multifunctional enzyme, and one 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase). The increased number of β-oxidation isozymes in C. albicans relative to S. cerevisiae might indicate that this fungus has undergone an adaptation toward a more sophisticated fatty acid metabolism compared to S. cerevisiae, allowing it to handle a wider variety of fatty acid substrates.

Transcriptional activation of β-oxidation genes in S. cerevisiae is regulated by the Pip2/Oaf1 heterodimer that binds to the upstream oleate-response element (ORE) (39). C. albicans does not encode orthologs of the Pip2/Oaf1 transcription factors but expresses a Zn2-Cys6 transcription factor called Ctf1 that binds a CCTCGG motif that is present in the majority of β-oxidation and glyoxylate cycle genes (16, 36). Ctf1 is an ortholog of transcription factors FarA and FarB of the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. These two transcription factors were shown to be essential for oxidation of short-chain fatty acids (FarB) or short- and long-chain fatty acids (FarA) (16) and are part of a large family of proteins with orthologs in multiple fungi. As FarA/FarB/Ctf1 orthologs are found in many other fungi, with the notable exception of S. cerevisiae (16), regulation of β-oxidation genes by this family of transcription factors seems to be a conserved trait, and the Pip2/Oaf1 system is most likely unique to S. cerevisiae and its closest relatives. Other relevant differences in the regulatory network for nonfermentable carbon metabolism between S. cerevisiae and C. albicans are the Cat8 and Adr1 transcription factors, which regulate the expression of glyoxylate cycle and gluconeogenesis enzymes in S. cerevisiae but do not seem to play similar roles in C. albicans (15, 36, 44).

THE GLYOXYLATE CYCLE

The products of the peroxisomal β-oxidation are shortened fatty acids and acetyl units, and the latter need to be transported to the mitochondrial TCA cycle for ATP generation. Unlike mammals, fungi can grow on fatty acids as sole carbon sources, as they not only are able to generate energy from acetyl (C2) units but also can synthesize sugars from C2. The pathway that is responsible for the generation of C4 from C2 units is the glyoxylate cycle, which consists of two key enzymes: isocitrate lyase (Icl1) and malate synthase (Mls1). The glyoxylate cycle is unique to plants and microorganisms such as Escherichia coli and fungi and is essential for growth on nonfermentable carbon sources such as fatty acids, ethanol, or acetate as sole carbon sources. Disruption or mutation of Icl1 or Mls1 leads to a complete growth defect on nonfermentable carbon sources (14, 25, 28). The glyoxylate cycle essentially is a shunt of the TCA cycle that acts on isocitrate, thereby excluding the decarboxylation steps of the TCA cycle catalyzed by isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idh1) and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (α-Kgdh) (Fig. 1B). The glyoxylate cycle was shown to be essential for virulence in C. albicans (25), and Lorenz's group also mapped the upregulation of C. albicans genes involved in alternative carbon metabolism during phagocytosis by macrophages (24). The upregulation of the β-oxidation machinery during phagocytosis suggested an important role of this metabolic pathway in virulence; however, C. albicans fox2 null strains that are unable to β-oxidize fatty acids exhibit no gross virulence defects (32, 35). In support of these findings, carnitine acetyltransferase (cat2) null strains that are unable to use carnitine for transport of acetyl units between compartments also do not display any virulence defects (47, 54). Therefore, the exact role of the glyoxylate cycle and the contribution of alternative carbon metabolism to C. albicans pathogenesis remain unclear.

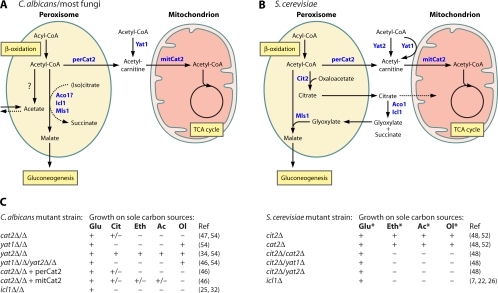

The subcellular distribution of the (key) glyoxylate cycle enzymes varies between organisms (reviewed in reference 22) (Fig. 2A and B). In C. albicans, Icl1 and Mls1 are compartmentalized in peroxisomes (31), as is the case in plants and fungi, with the exception of S. cerevisiae, where Icl1 is cytosolic and Mls1 is localized to the peroxisomes or cytosol depending on the growth conditions (21, 27). Aconitase (Aco), the glyoxylate/TCA enzyme that converts citrate to isocitrate, has been reported to be extramitochondrial in plants (5) and yeast (37). The C. albicans genome encodes two aconitase enzymes, Aco1 and Aco2, both of which have a predicted mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS), but Aco1 additionally has a putative peroxisomal targeting sequence (PTS1; -SKYCOOH). We determined the subcellular distribution of the aconitases experimentally and found a dual localization. The majority of the signal detected with an anti-Aco1 antibody cofractionated with the mitochondria, and some associated with the peroxisomes (our unpublished data). The presence of Aco1 in peroxisomes implies transport of citrate from mitochondria to peroxisomes, where it is converted to isocitrate and can feed into the glyoxylate cycle. Final proof for a peroxisomal localization of Aco1 and transport of citrate over the peroxisomal membrane in C. albicans, however, awaits further experiments.

Fig. 2.

Acetyl unit transport pathways in fungi. (A and B) Schematic representation of acetyl unit transport pathways in C. albicans and S. cerevisiae, respectively. (C) Growth phenotypes of deletion mutant strains on different carbon sources. Phenotypes of S. cerevisiae strains with a disrupted CIT2 gene were assessed in media containing l-carnitine (*). Abbreviations: Aco1, aconitase; β-ox, β-oxidation of fatty acids; Cit2, peroxisomal citrate synthase; Icl1, isocitrate lyase; mitCat2, mitochondrial Cat2; Mls1, malate synthase; perCat2, peroxisomal Cat2; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle; Yat1/Yat2, carnitine acetyltransferase; Glu, glucose; Cit, citrate; Eth, ethanol; Ac, acetate; Ol, oleate. +, growth; ±, weak growth; −, no growth.

Other nonfermentable carbon sources that can be utilized by fungi are ethanol and acetate. After uptake, these substrates are converted in the cytosol to acetyl-CoA (Fig. 1B). Because fungi possess the glyoxylate cycle, ethanol or acetate can be utilized not only as energy source but also as building blocks for higher-order carbohydrates. To accomplish this, cytosolic acetyl units need to be transported to both the mitochondrial TCA cycle and the peroxisomal glyoxylate cycle, the mechanism of which is discussed below. Therefore, growth of fungi on ethanol or acetate as the sole carbon source is dependent on the glyoxylate cycle enzymes Icl1 and Mls1 (14, 25, 28) but also on transport of acetyl units between subcellular compartments (46, 47, 54).

CARNITINE-DEPENDENT AND -INDEPENDENT TRANSPORT OF ACETYL UNITS

Because of its amphiphilic nature and bulkiness, acetyl-CoA cannot freely cross biological membranes (1, 40, 51). Two major pathways that allow the export of acetyl units generated by peroxisomal β-oxidation have been identified: (i) a carnitine shuttle in which carnitine-acetyltransferases reversibly link the carrier carnitine to the acetyl unit of acetyl-CoA, forming acetyl-carnitine that can cross the membrane, and (ii) through the action of peroxisomal citrate synthase that catalyzes the condensation of acetyl-CoA with oxaloacetate to form citrate, which can be transported over the peroxisomal membrane. The relative importance of the two modes of acetyl unit transport varies from species to species. In plants only the citrate synthase pathway is operational (33), whereas most fungi use the carnitine shuttle (Fig. 2A). A notable exception is S. cerevisiae, for which it has been shown that both pathways function in parallel (Fig. 2B) (52).

The genomes of C. albicans and S. cerevisiae encode three putative carnitine acetyltransferases: Cat2, Yat1, and Yat2 (also called CTN2, CTN1, and CTN3 in C. albicans) (34). Cat2 is the major carnitine acetyltransferase that has a dual localization to peroxisomes and mitochondria in both organisms (6, 47). A dual localization of Cat2 has also been shown for Candida tropicalis (19) and is predicted for most other fungi (our unpublished observations), suggesting that the carnitine shuttle is operational in most of these species. However, BLAST analysis of the sequenced fungal genomes has revealed that most fungal species seem to lack a predicted peroxisomal citrate synthase (47). Consistent with this, we have shown experimentally that C. albicans peroxisomes do not contain citrate synthase, and therefore this organism is completely dependent on Cat2 for the transport of acetyl units (47, 54) (Fig. 2A). The dependence of C. albicans on carnitine is also emphasized by the finding that this organism expresses a functional carnitine biosynthesis pathway (45), while S. cerevisiae is dependent on Cit2 activity in the absence of sufficient carnitine (52). Phylogenetic analysis suggests that in S. cerevisiae the mitochondrial and peroxisomal Cit originate from a recent gene duplication (12), again emphasizing that yeast is likely to represent the outlier among the fungi in the way that acetyl units are exported from peroxisomes.

Peroxisomal Cat2 generates acetyl-carnitine inside the organelle, which can subsequently be transported across the membrane. Upon arrival in the mitochondria, the acetyl units are released from acetyl-carnitine by the reverse reaction catalyzed by mitochondrial Cat2 (Fig. 1B). Although this metabolic scheme indicates that peroxisomal and mitochondrial Cat2 are equally important for acetyl unit transport from peroxisomes to mitochondria during growth on fatty acids, this does not seem to be the case. Remarkably, the study of C. albicans mutant strains that specifically lack either the mitochondrial Cat2 (perCAT2 strain) or the peroxisomal Cat2 (mitCAT2 strain) showed that peroxisomal Cat2 is not essential for fatty acid β-oxidation. The high levels of β-oxidation in the mitCAT2 strain (measured by CO2 production in whole cells) suggest that acetyl units are still exported from the peroxisomal matrix and enter the mitochondrial TCA cycle, even in the absence of peroxisomal Cat2 (46). A carnitine-independent route for exporting acetyl units has been demonstrated in mammals (23). Here, it was shown that peroxisomal thioesterases convert acetyl-CoA to acetate that is able to cross the peroxisomal membrane. We hypothesize that a similar pathway may exist in C. albicans. The C. albicans genome encodes four thioesterases that are predicted to be peroxisomal, a situation that again is more comparable to that in humans (three thioesterases) than to that in S. cerevisiae (a single thioesterase). In addition, transport of acetyl units from peroxisomes to mitochondria in the absence of peroxisomal CAT2 was shown to be dependent on cytosolic carnitine acetyltransferase Yat1 (Fig. 1B). This dependence suggests that transport of acetyl-CoA over the mitochondrial membrane and/or feeding into the TCA cycle in C. albicans requires formation of acetyl-carnitine in the cytosol (46). This is interesting, since experiments with S. cerevisiae suggest that acetate can be transported over the mitochondrial membrane under acid pH conditions (8). Surprisingly, while the mitCAT2 strain displays very high β-oxidation activity, it is unable to grow on fatty acids as sole carbon sources. This uncoupling of fatty acid oxidation and growth points toward a defect of the glyoxylate cycle and more specifically to a peroxisomal import defect of (iso)citrate when oleate is the carbon source but not when the mutant cells are grown on acetate or ethanol (46). During growth on acetate and ethanol, acetyl-CoA is produced in the cytosol and needs to be transported to the peroxisomal glyoxylate cycle and the mitochondrial TCA cycle. We have shown that in C. albicans growth on ethanol and acetate is dependent on the mitochondrial Cat2 but not strictly on the peroxisomal Cat2. This again suggests that acetate might be capable of crossing the peroxisomal membrane but not the mitochondrial (inner) membrane (46). This is fundamentally different in S. cerevisiae, as a cit2Δ/cat2Δ strain does not display any β-oxidation activity in intact cells, while normal β-oxidation takes place in total lysates of the cit2Δ/cat2Δ strain when membrane barriers are absent. These results strongly suggest that S. cerevisiae is unable to export acetyl units when both Cit2 and Cat2 are absent and support the notion that in yeast, acetyl-CoA (or acetate) cannot cross the peroxisomal membrane (51) (Fig. 2B).

The carnitine acetyltransferase homologs Yat1 and Yat2 localize to the cytosol in C. albicans (46), while S. cerevisiae Yat1 localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane (43) and Yat2 localizes to the cytosol (11) (Fig. 2). In S. cerevisiae disruption of either YAT1 or YAT2 in the cit2Δ background results in the same growth phenotype as in the cit2Δ/cat2Δ strain: all double knockouts are unable to grow on oleate, ethanol, or acetate (48) (Fig. 2C). It is currently unclear why all three carnitine acetyltransferases are essential for growth on nonfermentable carbon sources in a strain lacking peroxisomal citrate synthase. Because of their homology to carnitine acetyltransferases and their observed subcellular localization, both C. albicans Yat proteins were initially hypothesized to function as carnitine acetyltransferases acting on cytosolic acetyl-CoA derived from ethanol and acetate (Fig. 1B and 2A). However, the growth phenotypes of C. albicans YAT1 and YAT2 disruption strains are quite different: a yat1 null strain grows like the wild type on oleate but is unable to grow on ethanol or acetate, while a yat2 null strain does not display any growth defect (Fig. 2C) (34, 54). In addition, we recently showed that in C. albicans Yat1 is a genuine cytosolic carnitine acetyltransferase, but Yat2 does not contribute to acetyl-carnitine formation during growth on oleate or acetate (46). From these findings the picture emerges that in C. albicans Yat1 handles the conversion of cytosolic acetyl units and Yat2 is not a functional carnitine acetyltransferase. Establishing the true function of Yat2 remains an interesting challenge in the field.

CARNITINE TRANSPORTERS

Acetyl-carnitine is transported over the peroxisomal membrane in fungi, but a specific peroxisomal acetyl-carnitine transporter protein(s) has thus far not been identified. Acetyl-carnitine and acyl-carnitine transport over the mitochondrial membranes, on the other hand, has been well characterized in humans, where peroxisomal β-oxidation acts on very-long-chain fatty acids and shortened long-chain acyl units are transported to the mitochondrial matrix as acyl-carnitine for further oxidation. Long-chain fatty acids taken up by the cells are first activated in the cytosol to acyl-CoAs. The enzyme carnitine palmitoyl-transferase I (CPTI), which is associated with the outer mitochondrial membrane, then links carnitine to the acyl unit of acyl-CoA. Next, acyl-carnitine is transported over the outer mitochondrial membrane by diffusion or an unknown transporter and over the inner mitochondrial membrane via the specific carrier carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase (CACT). CPTII in the mitochondrial matrix links the acyl unit to intramitochondrial CoA, forming acyl-CoA that can enter mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. CACT is also able to transport acetyl-carnitine (reviewed in reference 41). The S. cerevisiae gene Yor100c (CRC1) was identified as the ortholog of human CACT (30, 52), and the human carrier was shown to functionally complement an S. cerevisiae cit2Δ/crc1Δ mutant (17). Based on sequence similarity, the likely C. albicans CACT/CRC1 ortholog is orf19.2599. Besides carnitine-mediated transport between organelles, carnitine can also be taken up from the extracellular medium. S. cerevisiae Agp2, a transporter that is a member of the amino acid permease family, was shown to localize to the plasma membrane, where it is responsible for the uptake of carnitine from the extracellular medium (52). We identified the C. albicans orf19.4679 as the most likely Agp2 ortholog based on BLAST analysis, but a disruption mutant was still able to import carnitine (our unpublished observations). The screen performed by Van Roermund et al. (52), aimed at isolation of S. cerevisiae mutants affected in acetyl unit transport from peroxisomes to mitochondria, failed to identify a peroxisomal acyl/acetyl-carnitine carrier. A possible explanation for this observation is that recent evidence suggests that the peroxisomal membrane contains pore-forming proteins that enable transfer of small molecules (with molecular masses of less than 400 Da) across the membrane (1, 13, 38, 40). This finding may suggest that a small molecule like acetyl-carnitine does not require a specific transporter but can pass the peroxisomal membrane through a pore-forming channel. Characterization of metabolite transport over the peroxisomal membrane remains a large challenge for the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Frans Hochstenbach for his valuable comments and suggestions.

This work was supported by a grant from the Academic Medical Center.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 October 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonenkov V. D., Sormunen R. T., Hiltunen J. K. 2004. The rat liver peroxisomal membrane forms a permeability barrier for cofactors but not for small metabolites in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 117:5633–5642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Askew C., Sellam A., Epp E., Hogues H., Mullick A., Nantel A., Whiteway M. 2009. Transcriptional regulation of carbohydrate metabolism in the human pathogen Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown A. J., Odds F. C., Gow N. A. 2007. Infection-related gene expression in Candida albicans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carman A. J., Vylkova S., Lorenz M. C. 2008. Role of acetyl coenzyme A synthesis and breakdown in alternative carbon source utilization in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 7:1733–1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courtois-Verniquet F., Douce R. 1993. Lack of aconitase in glyoxysomes and peroxisomes. Biochem. J. 294:103–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elgersma Y., van Roermund C. W., Wanders R. J., Tabak H. F. 1995. Peroxisomal and mitochondrial carnitine acetyltransferases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are encoded by a single gene. EMBO J. 14:3472–3479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez E., Moreno F., Rodicio R. 1992. The ICL1 gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 204:983–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleck C. B., Brock M. 2009. Re-characterisation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ach1p: fungal CoA-transferases are involved in acetic acid detoxification. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46:473–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fradin C., De Groot P., MacCallum D., Schaller M., Klis F., Odds F. C., Hube B. 2005. Granulocytes govern the transcriptional response, morphology and proliferation of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol. Microbiol. 56:397–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fradin C., Kretschmar M., Nichterlein T., Gaillardin C., d'Enfert C., Hube B. 2003. Stage-specific gene expression of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1523–1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franken J., Kroppenstedt S., Swiegers J. H., Bauer F. F. 2008. Carnitine and carnitine acetyltransferases in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a role for carnitine in stress protection. Curr. Genet. 53:347–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabaldon T., Snel B., van Zimmeren F., Hemrika W., Tabak H., Huynen M. A. 2006. Origin and evolution of the peroxisomal proteome. Biol. Direct. 1:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grunau S., Mindthoff S., Rottensteiner H., Sormunen R. T., Hiltunen J. K., Erdmann R., Antonenkov V. D. 2009. Channel-forming activities of peroxisomal membrane proteins from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS J. 276:1698–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartig A., Simon M. M., Schuster T., Daugherty J. R., Yoo H. S., Cooper T. G. 1992. Differentially regulated malate synthase genes participate in carbon and nitrogen metabolism of S. cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:5677–5686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedges D., Proft M., Entian K. D. 1995. CAT8, a new zinc cluster-encoding gene necessary for derepression of gluconeogenic enzymes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:1915–1922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hynes M. J., Murray S. L., Duncan A., Khew G. S., Davis M. A. 2006. Regulatory genes controlling fatty acid catabolism and peroxisomal functions in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 5:794–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IJlst L., van Roermund C. W., Iacobazzi V., Oostheim W., Ruiter J. P., Williams J. C., Palmieri F., Wanders R. J. 2001. Functional analysis of mutant human carnitine acylcarnitine translocases in yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280:700–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston M. 1999. Feasting, fasting and fermenting. Glucose sensing in yeast and other cells. Trends Genet. 15:29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawachi H., Atomi H., Ueda M., Hashimoto N., Kobayashi K., Yoshida T., Kamasawa N., Osumi M., Tanaka A. 1996. Individual expression of Candida tropicalis peroxisomal and mitochondrial carnitine acetyltransferase-encoding genes and subcellular localization of the products in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biochem. 120:731–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunau W. H., Dommes V., Schulz H. 1995. Beta-oxidation of fatty acids in mitochondria, peroxisomes, and bacteria: a century of continued progress. Prog. Lipid Res. 34:267–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunze M., Kragler F., Binder M., Hartig A., Gurvitz A. 2002. Targeting of malate synthase 1 to the peroxisomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells depends on growth on oleic acid medium. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:915–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunze M., Pracharoenwattana I., Smith S. M., Hartig A. 2006. A central role for the peroxisomal membrane in glyoxylate cycle function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763:1441–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leighton F., Bergseth S., Rortveit T., Christiansen E. N., Bremer J. 1989. Free acetate production by rat hepatocytes during peroxisomal fatty acid and dicarboxylic acid oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 264:10347–10350 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenz M. C., Bender J. A., Fink G. R. 2004. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1076–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenz M. C., Fink G. R. 2001. The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature 412:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCammon M. T. 1996. Mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with defects in acetate metabolism: isolation and characterization of Acn− mutants. Genetics 144:57–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCammon M. T., Veenhuis M., Trapp S. B., Goodman J. M. 1990. Association of glyoxylate and beta-oxidation enzymes with peroxisomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 172:5816–5827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKinney J. D., Honer zu Bentrup K., Munoz-Elias E. J., Miczak A., Chen B., Chan W. T., Swenson D., Sacchettini J. C., Jacobs W. R., Jr., Russell D. G. 2000. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature 406:735–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Odds F. C. 1987. Candida infections: an overview. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 15:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmieri L., Lasorsa F. M., Iacobazzi V., Runswick M. J., Palmieri F., Walker J. E. 1999. Identification of the mitochondrial carnitine carrier in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 462:472–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piekarska K., Hardy G., Mol E., van den Burg J., Strijbis K., van Roermund C., van den Berg M., Distel B. 2008. The activity of the glyoxylate cycle in peroxisomes of Candida albicans depends on a functional beta-oxidation pathway: evidence for reduced metabolite transport across the peroxisomal membrane. Microbiology 154:3061–3072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piekarska K., Mol E., van den Berg M., Hardy G., van den Burg J., van Roermund C., MacCallum D., Odds F., Distel B. 2006. Peroxisomal fatty acid beta-oxidation is not essential for virulence of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1847–1856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pracharoenwattana I., Cornah J. E., Smith S. M. 2005. Arabidopsis peroxisomal citrate synthase is required for fatty acid respiration and seed germination. Plant Cell 17:2037–2048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prigneau O., Porta A., Maresca B. 2004. Candida albicans CTN gene family is induced during macrophage infection: homology, disruption and phenotypic analysis of CTN3 gene. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:783–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramirez M. A., Lorenz M. C. 2007. Mutations in alternative carbon utilization pathways in Candida albicans attenuate virulence and confer pleiotropic phenotypes. Eukaryot. Cell 6:280–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramirez M. A., Lorenz M. C. 2009. The transcription factor homolog CTF1 regulates β-oxidation in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 8:1604–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Regev-Rudzki N., Karniely S., Ben-Haim N. N., Pines O. 2005. Yeast aconitase in two locations and two metabolic pathways: seeing small amounts is believing. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:4163–4171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rokka A., Antonenkov V. D., Soininen R., Immonen H. L., Pirila P. L., Bergmann U., Sormunen R. T., Weckstrom M., Benz R., Hiltunen J. K. 2009. Pxmp2 is a channel-forming protein in mammalian peroxisomal membrane. PLoS One 4:e5090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rottensteiner H., Kal A. J., Hamilton B., Ruis H., Tabak H. F. 1997. A heterodimer of the Zn2Cys6 transcription factors Pip2p and Oaf1p controls induction of genes encoding peroxisomal proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 247:776–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rottensteiner H., Theodoulou F. L. 2006. The ins and outs of peroxisomes: co-ordination of membrane transport and peroxisomal metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763:1527–1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubio-Gozalbo M. E., Bakker J. A., Waterham H. R., Wanders R. J. 2004. Carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase deficiency, clinical, biochemical and genetic aspects. Mol. Aspects Med. 25:521–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell C., Lay K. M. 1973. Natural history of Candida species and yeasts in the oral cavities of infants. Arch. Oral Biol. 18:957–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmalix W., Bandlow W. 1993. The ethanol-inducible YAT1 gene from yeast encodes a presumptive mitochondrial outer carnitine acetyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:27428–27439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon M., Adam G., Rapatz W., Spevak W., Ruis H. 1991. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae ADR1 gene is a positive regulator of transcription of genes encoding peroxisomal proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:699–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strijbis K., van Roermund C. W., Hardy G. P., van den Burg J., Bloem K., de Haan J., van Vlies N., Wanders R. J., Vaz F. M., Distel B. 2009. Identification and characterization of a complete carnitine biosynthesis pathway in Candida albicans. FASEB J. 23:2349–2359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strijbis K., van Roermund C. W., van den Burg J., van den Berg M., Hardy G. P., Wanders R. J., Distel B. 2010. Contributions of carnitine acetyltransferases to intracellular acetyl unit transport in Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 285:24335–24346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strijbis K., van Roermund C. W., Visser W. F., Mol E. C., van den Burg J., MacCallum D. M., Odds F. C., Paramonova E., Krom B. P., Distel B. 2008. Carnitine-dependent transport of acetyl coenzyme A in Candida albicans is essential for growth on nonfermentable carbon sources and contributes to biofilm formation. Eukaryot. Cell 7:610–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swiegers J. H., Dippenaar N., Pretorius I. S., Bauer F. F. 2001. Carnitine-dependent metabolic activities in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: three carnitine acetyltransferases are essential in a carnitine-dependent strain. Yeast 18:585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thewes S., Kretschmar M., Park H., Schaller M., Filler S. G., Hube B. 2007. In vivo and ex vivo comparative transcriptional profiling of invasive and non-invasive Candida albicans isolates identifies genes associated with tissue invasion. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1606–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van den Berg M. A., Steensma H. Y. 1995. ACS2, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene encoding acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase, essential for growth on glucose. Eur. J. Biochem. 231:704–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Roermund C. W., Elgersma Y., Singh N., Wanders R. J., Tabak H. F. 1995. The membrane of peroxisomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is impermeable to NAD(H) and acetyl-CoA under in vivo conditions. EMBO J. 14:3480–3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Roermund C. W., Hettema E. H., van den Berg M., Tabak H. F., Wanders R. J. 1999. Molecular characterization of carnitine-dependent transport of acetyl-CoA from peroxisomes to mitochondria in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and identification of a plasma membrane carnitine transporter, Agp2p. EMBO J. 18:5843–5852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White S. J., Rosenbach A., Lephart P., Nguyen D., Benjamin A., Tzipori S., Whiteway M., Mecsas J., Kumamoto C. A. 2007. Self-regulation of Candida albicans population size during GI colonization. PLoS Pathog. 3:e184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou H., Lorenz M. C. 2008. Carnitine acetyltransferases are required for growth on non-fermentable carbon sources but not for pathogenesis in Candida albicans. Microbiology 154:500–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]