Copper-catalyzed Ullmann ether synthesis has been studied for many years because aryl ethers comprise important classes of medicinally active compounds and agrochemicals.[1,2] The traditional Ullmann-type reactions required high temperatures, use of polar and high-boiling solvents, and stoichiometric quantities of the copper salt. Recently, by combining the copper with a variety of different ligands, milder catalytic Ullmann reactions have been developed [Eq. (1)]. Examples

| (1) |

of such ligands include phenanthrolines,[3,4] N,N-dimethyl glycine,[5] various pyridine derivatives,[6] β-diketones,[7] and 1,1,1-tris(hydroxymethyl)ethane.[8]

Despite the progress toward improving the scope and developing milder reaction conditions for the coupling of aryl halides with phenoxides, a mechanistic basis for the relative reactivities of different catalysts toward various C–O coupling processes has not been established. Over 35 years ago, it was shown that the addition of the dative ligand pyridine improved the yield of the reaction of copper(I) phenoxide with phenyl bromide to produce Ph2O, but the species formed from the coordination of pyridine was not isolated, and little additional information has been gained on the reactivity of copper phenoxide complexes containing dative ligands.[9] Only recently have any isolated copper complexes been evaluated as intermediates in copper-catalyzed coupling reactions.[10,11] In one recent study, copper(I) imidates and amidates were isolated in pure form, structurally characterized, and shown to be intermediates in related copper-catalyzed Goldberg reactions,[10] and in another study kinetic data were obtained on copper amidates generated in situ.[12,13] The relationship between intermediates in copper-catalyzed coupling reactions that form C–N bonds and potential intermediates in couplings that form C–O bonds is unknown.

In the absence of clear information on the composition and structure of intermediates in the Ullmann ether synthesis, several distinct mechanisms for reactions of copper alkoxides and aryloxides with aryl halides have been proposed. The haloarene has been proposed to react with either anionic, two-coordinate cuprates, such as [Cu(OR)2]−,[14] or neutral copper alkoxides, such as CuOR.[15] The C–X bond-cleavage step has been proposed to occur either by oxidative addition of the C–X bond to yield a CuIII intermediate or through a one-electron transfer from the copper center to the haloarene to yield a haloarene radical anion that undergoes C–X cleavage. Moreover, because phenoxy radicals are particularly stable, reactions of copper aryloxide complexes could occur through radical pathways that would be less accessible to complexes containing other types of anionic ligands.

Herein we report the synthesis and structural identification of copper phenoxide complexes containing ancillary nitrogen-donor ligands, and the reactions of these species with haloarenes, including haloarenes containing or serving themselves as radical probes.[10] These studies reveal unexpected structures, demonstrate the competence of the isolated complexes to be intermediates in the catalytic process, provide arguments against the intermediacy of aryl radicals formed by electron transfer to the aryl halides, reveal quantitatively the effect of the electronic properties of the aryloxide ligand on the reactivity of these species with haloarenes, and reveal the relative rates for reactions of haloarenes with copper phenoxide, amidate, and imidate complexes.

The synthesis of the copper aryloxide complexes in this study containing 1,10-phenanthroline (phen), 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline (Me2phen), and trans-N,N′-dimethyl-1,2-cyclohexanediamine (dmcyda) is summarized in Scheme 1. Treating CuCl with 1 equivalent of NaOPh and subsequent addition of the dative ligand, led to the formation of complexes 1a–1c containing phen, Me2phen, and dmcyda as the ancillary dative ligand, and phenoxide as the anionic ligand. These phenoxide complexes were isolated in 87–98% yield.

Scheme 1.

All CuI aryloxide complexes were characterized by elemental analysis and NMR spectroscopy. The 1H NMR spectrum of each complex revealed a 1:1 ratio of the dative ligand to the phenoxide ligand, and all analytical data were consistent with this 1:1 ratio. However, the solid-state structures of these complexes differed from a simple neutral species containing a 1:1:1 ratio of dative ligand, phenoxide, and copper.

The solid-state structure of 1b was determined by X-ray diffraction. These data show that 1b (Figure 1) consists of a double salt containing one cationic tetrahedral copper center ligated by two of the dative Me2phen ligands and one relatively open, anionic, two-coordinate linear copper center ligated by just phenoxide ligands. A related structure containing a bis(imine) ligand was observed as part of a structural study of copper phenoxide complexes,[16] and certain CuI–imidate complexes, although more hindered, were shown to exist as related ionic structures. Such ionic structures of ligated copper alkoxides and aryloxides have rarely, if ever, been considered in mechanistic proposals, and they have not been structurally characterized with ligands that create catalysts for Ullman etherifications.

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagram of 1b at 30 % ellipsoids. Selected bond lengths [&] and angles[°]: Cu(1)–N(1) 2.027(3), Cu(1)–N(2) 2.048(3), Cu(1)–N(3) 2.050(3), Cu(1)–N(4) 2.028(3), Cu(2)–O(1) 1.816(4), Cu(2)–O(2) 1.787(4); O(1)-Cu(2)-O(2) 177.81(19).[36]

Conductivity was used to determine if these complexes were present in solution in either the ionic form as seen in the solid state or in the neutral form containing one dative ligand and one phenoxide. The molar conductivity of 1.0 mM solutions containing complexes 1a–c in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was high (37.1, 27.0, 31.9 Ω−1cm2mol−1, respectively), with respect to ferrocene (0.3 Ω−1cm2mol−1) as a neutral standard and [NBu4][BPh4] (23.5 Ω−1cm2mol−1) as an ionic standard. These data imply that each of the phenoxide complexes exists predominantly in the ionic form in polar solvents. The conductivity of a 65.5 mM tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution of 1c was 6.8 μΩcm−1 (0.104 Ω−1cm2mol−1). For comparison, the conductivity of a 65.5 mM THF solution of [(n-octyl)4N][Br] was 65.1 μΩ cm−1 (0.99 Ω−1cm2mol−1), and the value for a 65.5 mM solution of ferrocene was 0.0 μΩcm−1 (0.0 Ω−1cm2mol−1). These data indicate that the double salt and the neutral species depicted in [Eq. (1)] exist in equilibrium and that more of the neutral form is present in the less polar THF solvent than in the more polar DMSO solvent.

After isolation and full characterization of the phenoxide complexes 1a–c, we evaluated the potential of these complexes to serve as intermediates in the copper-catalyzed etherification of aryl halides. The reactions of 1 a–c with iodoarenes are summarized in [Eq. (2)]. Reaction of the

|

(2) |

phen-ligated complex 1a with 5 equivalents of p-iodotoluene in DMSO formed the coupled product in 91% yield after 75 minutes at 110°C, and reaction of the Me2phen-ligated complex 1b with 5 equivalents of p-iodotoluene in DMSO formed the coupled product in 90% yield after 19 hours at 110°C. The dmcyda-ligated complex 1c reacted much faster. The reaction of 1c with 5 equivalents of p-iodotoluene in DMSO formed the coupled product in 95% yield after 15 minutes at 110°C in DMSO. These data imply that the complexes containing the more electron-donating dative ligand (1c) form ether products faster and in higher yields than those containing the less electron-donating dative ligands, 1a and 1b. This result parallels related observations of the reactions of copper imidate and amidate complexes with haloarenes. As expected, the increased steric effect of the ortho,ortho′-disubstituted Me2phen ligand in 1b caused this complex to react more slowly than complex 1a containing the unsubstituted phen ligand.

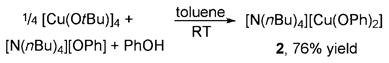

To address the ambiguity in past studies about the relative reactivity of neutral and anionic alkoxides and aryloxides, we compared the reactions of the isolated anionic species [Bu4N+][Cu(OPh)2−] (2) with the neutral complexes. Complex 2 was synthesized and isolated from the reaction of [Cu(OtBu)]4, [NBu4+][OPh−] and PhOH [Eq. (3)] and was

|

(3) |

characterized by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy and elemental analysis. Reaction of 2 with 5 equivalents of p-iodotoluene for 16 hours at 110°C in DMSO proceeded with low conversion and formed the biaryl ether product in only about 10% yield (Scheme 2).[17] In contrast, the reaction of a mixture of 2, 1 equivalent of the phen ligand, and 5 equivalents of p-iodotoluene for 135 minutes at 110°C in DMSO gave the ether product in 81% yield based on the number of phenoxide ligands (Scheme 2). These results imply that the ligated complexes produce aryl ethers more efficiently than do the anionic species.

Scheme 2.

The faster reaction of the ligated species is consistent with the effect of added ligand on the reactions of phen-ligated CuI phenoxide complex 1a with aryl halides. If the unligated species reacted with the aryl halide, the added ligand would be expected to retard reactions initiated with ligated complex 1a. However, reactions conducted with no added phenan-throline, 1 equivalent of added ligand, and 10 equivalents of added ligand occurred with rate constants of 4.1 × 10−4 s−1, 3.9 × 10−4 s−1, and 2.9 × 10−4 s−1, respectively. Although there was some variation in the rate constants, the roughly 25% change in the rate constant with a 10-fold increase in the amount of free ligand is consistent with a mechanism in which the ligated species reacts with the haloarene.

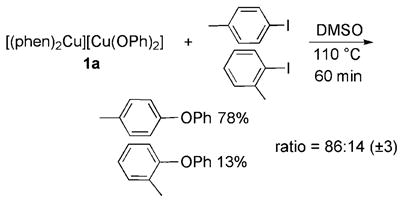

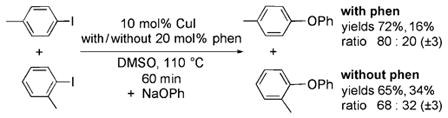

To evaluate further the potential intermediacy of the phenoxide compounds in copper-catalyzed etherification, we conducted competition reactions to measure the selectivity of two iodoarenes toward 1a in the stoichiometric reaction of the phenoxide complex with the iodoarenes [Eq. (4)], and in

|

(4) |

catalytic reactions of NaOPh with the two iodoarenes in the presence of 10 mol% CuI with and without 20 mol% phen [Eq. (5)], ]. We used the sensitivity of the reaction to steric effects as a probe for the potential intermediacy of the

|

(5) |

isolated copper complexes. Consistent with the intermediacy of these complexes in the catalytic process, the reaction of complex 1a with a 1:1 mixture of of p-iodotoluene and o-iodotoluene catalyzed by CuI and phen produced the two ether products in an 86:14 ratio [Eq. (4)], whereas the reaction of sodium phenoxide with a 1:1 mixture of the two iodoarenes formed the two aryl ethers in a nearly equal 80:20 ratio [Eq. (5)]. The presence of the phen ligand affects the selectivity of the metal for the two haloarenes. The reaction of a 1:1 ratio of the two iodoarenes catalyzed by CuI alone gave a different 68:32 ratio of the two ethers [Eq. (5)]. Thus, the similarity in the ratios of the products formed from the single-turnover and catalytic reactions indicates that complex 1 a is competent to be an intermediate in the reactions of aryl iodides with NaOPh catalyzed by the combination of CuI and phenanthroline.

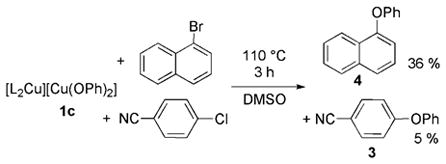

To probe for the potential intermediacy of free aryl radical intermediates and the potential for initial electron transfer, a series of experiments with specific aryl halides were conducted. To probe the potential of an electron-transfer mechanism, we studied the reactions of phenoxide complex 1a with 4-chlorobenzonitrile and 1-bromonaphthalene. The reduction potential of the chloroarene is more positive than that of the bromoarene, and the rate of chloride dissociation from the radical anion of 4-chlorobenzonitrile is known to be similar to that for bromide dissociation from the radical anion of 1-bromonaphthalene.[18,19] Therefore, reaction by an outer-sphere electron-transfer mechanism to generate a free or caged aryl radical should be faster with 4-chlorobenzonitrile than with 1-bromonaphthalene. However, reaction by a concerted oxidative addition to form an arylcopper(III) intermediate with the bromoarene should occur faster than that with the chloroarene.

The reactions of 1c in DMSO at 110°C after 3 hours with 4-chlorobenzonitrile and 1-bromonaphthalene produced the corresponding ether products in 13% (3) and 43% (4) yield, respectively. Consistent with this observation, the reaction of 1c with a mixture of 4-chlorobenzonitrile and 1-bromonaphthalene in DMSO at 110°C after 3 hours afforded the corresponding ether products 3 and 4 in 5% and 36% yield, respectively [Eq. (6)]. The low yield, presumably, results from

|

(6) |

the steric hindrance of the pseudo-ortho substituent in the naphthalene substrate. The higher reactivity of the bromoarene among this pair of haloarenes, nevertheless, argues against an outer-sphere electron-transfer pathway to form aryl radical anions that dissociate a halide to form aryl radicals, either free or in a solvent cage.

Reactions of o-(allyloxy)iodobenzene were studied to provide an additional probe for the formation of free aryl radicals. The corresponding aryl radical is known to undergo rapid cyclization to form a [3-(2,3-dihydrobenzofuran)]-methyl radical with a rate constant of 9.6 × 109 s−1 in DMSO with subsequent formation of 2-methyldihydrobenzofuran.[20] Therefore, the formation of coupled product without formation of accompanying cyclization products would indicate that the recombination of the radical with the copper aryloxide must occur with a rate constant greater than 1012 to 1013 s−1 if between 0.1% and 1% of the cyclized product can be detected.

The reaction of o-(allyloxy)iodobenzene with the p-cresolate analogue of 1a (5) [Eq. (7)] and reaction of o-(allyloxy)iodobenzene with p-CH3C6H4ONa catalyzed by CuI

|

(7) |

and phen [Eq. (8)] produced a mixture of the p-tolyl aryl ether 6 and phenyl allyl ether 7 as the sole products. The

|

(8) |

modest yield of coupled product, again, results from the presence of an ortho-alkoxy group.[21] The phenyl allyl ether formed from catalytic reactions in [D6]DMSO contained 57% deuterium, as determined by comparison of the GC/MS spectra of the mixture to that of nondeuterated phenyl allyl ether. The phenyl allyl ether formed from reactions of complex 5 in [D6]DMSO contained 30–66% deuterium, depending on the particular experiment. Therefore, the origin of all of the reducing equivalents is not certain, but the DMSO solvent is one source.

Although we cannot provide a definitive mechanism for formation of this hydrodehalogenation product, previous work showed that a hydrogen atom transfer to the free aryl radical does not compete significantly with cyclization.[20] Thus, the absence of products from cyclization and the higher reactivity of the copper phenoxide with 1-bromonapthalene than with 4-chlorobenzonitrile imply that free aryl radicals formed by initial electron transfer are unlikely to be intermediates in the stoichiometric or catalytic reactions of aryl halides with phenanthroline-ligated copper phenoxides.

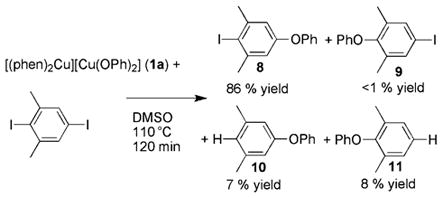

To probe the formation of aryl radicals that could be loosely bound to copper in a dynamic equilibrium, we conducted the reaction of phen-ligated phenoxide complex 1a with 1,4-diiodo-2,6-dimethylbenzene. Dissociation of the more hindered iodide has been shown to occur after electron transfer from enolates.[22] Consistent with the absence of free or loosely bound aryl radical anions leading to free aryl radicals, the reaction of the phen-ligated phenoxide complex 1a with 1,4-diiodo-2,6-dimethylbenzene at 110°C in DMSO yielded the aryl phenyl ether product 8 from cleavage of the less hindered C–I bond in 86% yield, along with minor amounts of the hydrodeiodination products 10 and 11 (7 and 8% yields, respectively), as determined by GC/MS analysis of the reaction mixture and comparison to independently synthesized compounds 8–11 [Eq. (9)].

|

(9) |

Finally, the ability to isolate pure aryloxide complexes which react with aryl halides allows a quantitative assessment of the effect of the electronic properties of the aryloxide ligand on the rate of the reaction with iodoarenes to form biaryl ethers. The rates of reaction of 4-fluoroiodobenzene with complexes containing para-hydrogen, para-methyl-, para-trifluoromethyl-, para-fluoro-, and para-methoxy substituents (1a, 5, 12, 13, and 14, respectively) were determined by 19F NMR spectroscopy. A plot of kobs versus σ was linear (R2 =0.98) with a ρ value of −1.52 (see the Supporting Information). These data indicate that the reaction is faster when the reactive ligand is more electron rich, most likely because it helps make the metal more electron rich and thereby accelerates oxidative addition of the aryl halide.

These data allow one to compare the rates of reaction of intermediates in Ullmann etherifications containing aryloxides with intermediates in Goldberg reactions containing amides. The phen-ligated phenoxide complex reacts faster than the phen-ligated phthalimidate (phth) complex [Cu-(phen)2][Cu(phth)2] and more slowly than the phen-ligated pyrrolidinonate (pyrr) complex [Cu(phen)2][Cu(pyrr)2] in the same DMSO solvent. These relative rates fall in line with the basicity of the anionic ligand, as judged by acidities of imides, amides, and phenoxides in DMSO.[23]

In conclusion, we have isolated copper phenoxide complexes which are kinetically and chemically competent to be intermediates in the copper-catalyzed etherification of aryl halides. All these complexes appear to exist in an ionic form in the solid state and in the polar solvents that are often used for copper-catalyzed coupling of phenoxides.[24–30] This ionic form contains two CuI sites, one bound by two chelating, dative ligands, and one by two phenoxides. In contrast to prior proposals of the reaction of anionic phenoxide complexes of copper, the isolated anion containing an ammonium counter-ion did not react with iodoarenes in high yields. Experiments that probe for redox processes and the generation of free or caged aryl radicals provide strong evidence against these process to form such radical intermediates and argue in favor of an oxidative addition to form an aryl–CuIII phenoxide complex that undergoes reductive elimination of ether. Although CuIII species are not common, alkylcopper(III)[31–34] and arylcopper(III)[11,35] species have been identified recently. Moreover, we have conducted computational studies by DFT on the energy of a phen-ligated arylcopper(III) halide phenoxide complex, and the ΔG for formation of this species from the [Cu(phen)(OPh)] and PhI is computed to be 22.1 kcalmol−1 [Eq. (10)]. This energy is consistent with the barrier corresponding to the conditions of the experiments in Eq. (2). Additional structural and mechanistic studies of related copper complexes are ongoing.

Experimental Section

Preparation of [bis(1,10-phenanthroline)Cu][bis(phenoxide)Cu] (1a): A solution of NaOPh (46.3 mg, 0.399 mmol) in 1 mL of THF was added to a suspension of CuCl (39.5 mg, 0.399 mmol) in 5 mL of THF, and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. The resulting light yellow mixture was filtered through a layer of Celite. To this filtrate was added a solution of 1,10-phenanthroline (72 mg, 0.40 mmol) in 1.5 mL of THF. The resulting solution turned reddish brown immediately and was additionally stirred at room temperature for 40 min. n-Pentane (12 mL) was added to precipitate the product. The product was separated from the supernatant by filtration through a fine fritted funnel and washed with 2 mL of pentane to afford 132 mg (98%) of 1a. 1H NMR (500 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ = 6.25 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 6.48 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H), 6.87 (t, J =7.0 Hz, 4H), 8.02–7.99 (m, 4H), 8.28 (s, 4H), 8.82 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H), 9.01 ppm (d, J =4 Hz, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δ = 113.4, 119.4, 126.4, 127.8, 129.4, 129.7, 138.0, 144.0, 150.2, 169.0 ppm; Anal. Calcd for C36H26Cu2N4O2: C, 64.18; H, 3.89; N, 8.32. Found: C, 64.45; H, 4.03; N, 7.94; Conductivity (25°C, 1.00 mM in DMSO): 37.1 Ωcm2mol−1.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We thank the NIH NIGMS (GM-55382) for support of this work. Z.W. thanks the National University of Singapore for support.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.200902245.

References

- 1.Ley SV, Thomas AW. Angew Chem. 2003;115:5558. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:5400. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sawyer JS. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:5045. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolter M, Nordmann G, Job GE, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2002;4:973. doi: 10.1021/ol025548k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gujadhur RK, Bates CG, Venkataraman D. Org Lett. 2001;3:4315. doi: 10.1021/ol0170105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma D, Cai Q. Org Lett. 2003;5:3799. doi: 10.1021/ol0350947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagan PJ, Hauptman E, Shapiro R, Casalnuovo A. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5043. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buck E, Song ZJ, Tschaen D, Dormer PG, Volante RP, Reider PJ. Org Lett. 2002;4:1623. doi: 10.1021/ol025839t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen YJ, Chen HH. Org Lett. 2006;8:5609. doi: 10.1021/ol062339h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawaki T, Hashimoto H. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1972;45:1499. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tye JW, Weng Z, Johns AM, Incarvito CD, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9971. doi: 10.1021/ja076668w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huffman LM, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9196. doi: 10.1021/ja802123p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strieter ER, Blackmond DG, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4120. doi: 10.1021/ja050120c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strieter ER, Bhayana B, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:78. doi: 10.1021/ja0781893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aalten HL, van Koten G, Grove DM, Kuilman T, Piekstra OG, Hulshof LA, Sheldon RA. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:5565. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitesides GM, Sadowski JS, Lilburn J. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:2829. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiaschi P, Floriani C, Pasquali M, Chiesi-Villa A, Guastini C. Inorg Chem. 1986;25:462. [Google Scholar]

- 17.As requested by a reviewer, we also conducted the reaction of cationic CuI species, [phen2Cu][PF6], with p-iodotoluene under the conditions of Scheme 2, and no reaction was observed.

- 18.Enemærke RJ, Christensen TB, Jensen H, Daasbjerg K. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 2001;2:1620. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrieux CP, SJM, Zann D. New J Chem. 1984;8:107. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annunziata A, Galli C, Marinelli M, Pau T. Eur J Org Chem. 2001:1323. [Google Scholar]

- 21.As a control, we conducted the reaction of o-(n-propoxy)iodo-benzene with 1a in DMSO at 110°C for 12 hours. Consistent with an ortho-alkoxy group leading to low yields from reaction with copper phenoxides, this reaction produced the biaryl ether product in 68% yield and phenyl n-propyl ether from hydrodeiodination in 31% yield. Reaction with 5 equivalents of the unhindered p-tert-butyl iodobenzene in DMSO at 110°C for 2 hours yielded the ether product in 80% yield and less than 2% yield of tert-butyl benzene derived from hydrodeiodination.

- 22.Branchi B, Galli C, Gentili P, Marinelli M, Mencarelli P. Eur J Org Chem. 2000:2663. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bordwell FG. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:456. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouali A, Spindler JF, Cristau HJ, Taillefer M. Adv Synth Catal. 2006;348:499. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao H, Jin Y, Fu H, Jiang Y, Zhao Y. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:3636. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia N, Taillefer M. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:6037. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Job GE, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2002;4:3703. doi: 10.1021/ol026655h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman RA, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2007;9:643. doi: 10.1021/ol062904g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niu J, Zhou H, Li Z, Xu J, Hu S. J Org Chem. 2008;73:7814. doi: 10.1021/jo801002c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lv X, Bao W. J Org Chem. 2007;72:3863. doi: 10.1021/jo070443m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertz SH, Cope S, Dorton D, Murphy M, Ogle CA. Angew Chem. 2007;119:7212. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:7082. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertz SH, Cope S, Murphy M, Ogle CA, Taylor BJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7208. doi: 10.1021/ja067533d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.G3rtner T, Henze W, Gschwind RM. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11362. doi: 10.1021/ja074788y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartholomew ER, Bertz SH, Cope S, Murphy M, Ogle CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11244. doi: 10.1021/ja801186c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xifra R, Ribas X, Llobet A, Poater A, Duran M, Sola M, Stack TDP, Benet Buchholz J, Donnadieu B, Mahia J, Parella T. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:5146. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CCDC-671252 (1b) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/datarequest/cif.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.