Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether media literacy concerning tobacco use is independently associated with two clinically relevant outcome measures in adolescents: current smoking and susceptibility to smoking.

Methods

We asked high school students aged 14–18 years to complete a survey that included a validated 18-item smoking media literacy (SML) scale, items assessing current smoking and susceptibility to future smoking, and covariates shown to be related to smoking. We used logistic regression to assess independent associations between the two outcome measures and SML.

Results

Of the 1211 students who completed the survey, 19% reported current smoking. Controlling for all potential confounders of smoking, we found that an increase of one point (out of 10) in SML was independently associated with an odds ratio for smoking of .84 (95% confidence interval [CI] .71–.99). Compared with students below the median score on the SML scale, students above the median had an odds ratio for smoking of .57 (95% CI .37–.87). Of the students who were nonsmokers, 40% were classified as susceptible to future smoking. Controlling for all potential confounders of smoking, we found that an increase of one point (out of 10) was independently associated with and an odds ratio for smoking susceptibility of .68 (95% CI .58–.79). Compared with students below the median SML, students above the median SML had an odds ratio for smoking susceptibility of .49 (95% CI .35–.68).

Conclusions

In this sample of high school students, higher SML is independently associated with reduced current smoking and reduced susceptibility to future smoking. © 2006 Society for Adolescent Medicine. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Smoking, Tobacco, Media, Advertising, Television, Media messages, Movies, Media literacy, Media education, Adolescence, Aubstance abuse, Education, School-based

In the United States, cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death and disease [1]. About 90% of individuals with smoking-related deaths began smoking during their adolescence [2], and each day nearly 4400 American youth between the ages of 12 and 17 years initiate cigarette smoking [3]. Despite efforts to address this rapid uptake of smoking among adolescents, traditional school-based smoking prevention programs have not been successful in affecting clinically relevant smoking behaviors [4–6].

Youth aged 8–18 years are exposed to 8 hours and 33 minutes of media content daily [7], including content offering a substantial number of positive impressions of cigarette smoking [8–10]. Studies have demonstrated an association between exposure to certain media messages and smoking in adolescents. Over half of the cases of smoking initiation during adolescence are linked to watching smoking in movies [11,12], for instance, and the exposure to media messages such as tobacco promotions and advertisements also significantly increases the risk of smoking initiation during adolescence [2,13–16]. In light of these findings, media literacy may represent a promising framework for developing innovative school-based smoking prevention programs [17]. Acknowledging the effects of media on attitudes and behavior, media literacy teaches youth to understand, analyze, and evaluate advertising and other media messages, enabling them to actively process media messages rather than passively remain message targets [18,19]. Media literacy has been shown to be potentially useful in reducing other harmful health behaviors such as alcohol use, disordered eating, and aggression [20–22]. Additionally, media literacy’s potential efficacy is grounded in health behavior theory. In particular, media literacy should reduce certain positive attitudes and norms that, according to the Theory of Reasoned Action, can lead to harmful intentions and behaviors [23,24].

It is not surprising, therefore, that organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend media literacy to buffer the impact of media messages on adolescent smoking [17,25]. Indeed, antismoking media literacy lessons have been well liked by students and have shown initial promise [25–27], making media literacy attractive as an intervention. However, these studies focused on the outcomes such as student satisfaction, knowledge, and attitudes, and did not demonstrate that antismoking media literacy is associated with improvements in clinically relevant outcomes related to smoking. We therefore used a reliable, validated scale measuring the construct of smoking media literacy (SML) in youth [24] to determine the degree to which clinically relevant smoking-related outcomes are associated with SML scores in a large group of high school students. We hypothesized that higher media literacy scores would be associated with a decreased likelihood of current smoking and that, among current nonsmokers, those with higher media literacy would have a lower susceptibility to future smoking.

Methods

Participants and setting

The study population for our cross-sectional survey consisted of students attending a suburban public high school outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania with a total enrollment of 1690. The community served by this high school is primarily Caucasian and middle-income. Male and female students were eligible to participate if they were 14–18 years old and were available to take the survey on the regular school day in January 2005 when it was administered. On this date, 79 students were absent and 86 were unavailable because of in-school suspensions, field trips, or appointments with the nurse or guidance counselor; 1525 students were eligible to participate. The questionnaire was administered by classroom teachers that we trained in methods of minimizing bias and appropriately responding to student queries.

Approval to administer the study questionnaire was granted by the superintendent of the school district and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Pittsburgh. Both the superintendent and IRB agreed to a waiver of parental informed consent, because students would not be asked to place their names or any other unique personal identifiers on the questionnaire. The students were invited to complete the questionnaire during their social studies classes, and those who did so were given a packet of trail mix as a reimbursement for their time.

Survey Instrument

We recently developed a scale to measure the independent variable, smoking media literacy (SML). We began with a pool of 120 potential items, tested and refined the scale, and assessed its reliability and validity [24]. The final 10-point SML scale consists of 18 items, representing the three domains and eight core concepts of media literacy listed in Table 1 [24]. The scale contains four items representing the Authors/Audiences domain, nine representing the Meanings/Messages domain, and five representing the Representation/Reality domain. Representative items include “Tobacco companies are very powerful, even outside of the cigarette business” (Authors/Audiences domain), “When people make movies and TV shows, every camera shot is very carefully planned” (Messages/Meanings domain), and “Advertisements usually leave out a lot of important information” (Representation/Reality domain). Each item was evaluated with a four-point Likert scale, and the resulting 54-point scale was divided by 5.4 to generate a value on a 10-point scale. The complete scale can be obtained from the first author at bprimack@pitt.edu

Table 1.

Theoretical Model of Media Literacy

| Media literacy domain | Media literacy core concept |

|---|---|

| AA: Authors and Audiences | AA1: Authors create media messages for profit and/or influence |

| AA2: Authors target specific audiences | |

| MM: Messages and Meanings | MM1: Messages contain values and specific points of view |

| MM2: Different people interpret messages differently | |

| MM3: Messages affect attitudes and behaviors | |

| MM4: Multiple production techniques are used | |

| RR: Reality and Representation | RR1: Messages filter reality |

| RR2: Messages omit information |

The survey also assessed two clinically relevant smoking outcomes: current smoking, defined as having smoked at least once in the past 30 days, and susceptibility to future smoking, assessed with Pierce’s reliable and valid three-item scale [28]. According to this scale, a person is considered “nonsusceptible” only if he or she answers “definitely no” to the following three items: (1) Do you think that you will smoke a cigarette soon? (2) Do you think you will smoke a cigarette in the next year? (3) If one of your best friends were to offer you a cigarette, would you smoke it?

We also assessed several covariates shown previously to be related to current smoking. Demographic information included age, race/ethnicity, gender, and parental education (as a surrogate for socioeconomic status). We also assessed important elements of the students’ environment (responsive parenting [29], demanding parenting [29], parental smoking, sibling smoking, friend smoking, electronic media use, and stress) and students’ intrinsic characteristics (self-report of school grades, depression [30], self-esteem [31], rebellious behavior [32], sensation-seeking [33], and knowledge of the harm and addictiveness of tobacco). To minimize respondent burden for such a lengthy survey, we selected representative items from these surveys instead of including all items.

Survey Processing and Analysis

Before administering the survey, we established specific criteria to detect and eliminate questionnaires with inconsistent or inappropriate responses. We examined responses to nine specific open-ended items and flagged the data of students who provided impossible or extremely improbable responses (e.g., claims to smoke an average of six complete packs of cigarettes each day). These students’ complete data were further scrutinized, and if three or more total responses were deemed to be impossible or extremely improbable, we eliminated the questionnaire from the analysis. In addition, we included a final survey item asking the students to appraise their honesty in answering the survey questions, and we eliminated the surveys of those who admitted providing dishonest answers. We performed all analyses on data from the entire sample as well from the subset who said they were honest to ensure that elimination of data did not affect the overall results.

After performing a descriptive data analysis of the survey responses, we assessed the relationship between the SML scale score and each of the smoking outcomes graphically. We then used logistic regression techniques to determine the bivariate and multivariate associations between SML and current smoking. Finally, we used logistic regression techniques to determine the bivariate and multivariate relationship between SML and susceptibility to smoking among those students who were not current smokers. Our models included all of the potential confounders of current smoking or susceptibility to smoking except for Hispanic ethnicity, because we did not have a sufficient number of Hispanic subjects. We categorized SML in two different ways in these analyses: as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable divided at the median SML score. This method of treating SML as a discrete variable was chosen for its simplicity and potential ease of clinical application.

To ensure appropriateness of each of the logistic models, we performed Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit testing. We also computed the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves associated with all models to determine their overall discriminating power [34].

Results

Of the 1525 students who were eligible for the study, 1402 (92%) completed the questionnaire. We eliminated 44 surveys that showed a pervasive pattern of impossible or improbable responses and 147 surveys in which students admitted to providing dishonest answers. The number of surveys available for analysis was therefore 1211 (86% of the surveys completed). Those eliminated from the analysis were no different than those included in terms of age, race, or reported parental education, respectively. However, those eliminated were more likely to be male (71% vs. 48%; p < .001).

The mean age of the 1211 respondents with valid data was 15.9 years, about half (48%) were male, and 92% were white (Table 2). With regard to the smoking-related measures, 19% reported current smoking, and 40% of the non-smokers were classified as susceptible to future smoking.

Table 2.

Demographic and covariate characteristics of the total sample and of current smokers within the sample

| Range (For continuous variables) | Total samplea | Current smokera | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 14 | 186 (15.7) | 18 (8.4) | |

| 15 | 277 (23.3) | 36 (16.8) | |

| 16 | 328 (27.6) | 66 (30.8) | |

| 17 | 301 (25.3) | 75 (35.0) | |

| 18 | 95 (8.0) | 19 (8.9) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 572 (47.6) | 100 (46.7) | |

| Female | 630 (52.4) | 114 (53.3) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 1092 (91.7) | 203 (94.4) | |

| Black | 49 (4.1) | 4 (1.9) | |

| Other | 50 (4.2) | 8 (3.7) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 1199 (99.1) | 214 (99.1) | |

| Hispanic | 11 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Parental educationb | |||

| No more than one parent completed high school | 64 (5.4) | 22 (10.2) | |

| One parent completed college or both parents completed high school completed high school | 369 (31.0) | 75 (34.7) | |

| One parent completed college and one completed high school | 328 (27.6) | 64 (29.6) | |

| Both parents completed college | 430 (36.1) | 55 (25.5) | |

| Parental smoking | |||

| Yes | 467 (39.0) | 127 (58.8) | |

| No | 731 (61.0) | 89 (41.2) | |

| Sibling smoking | |||

| Yes | 267 (22.7) | 90 (42.7) | |

| No | 907 (77.3) | 121 (57.4) | |

| Friend smoking | |||

| Yes | 625 (56.9) | 197 (96.6) | |

| No | 473 (43.1) | 7 (3.4) | |

| Responsive parenting | 1–4 | 3.3 (.6) | 3.1 (.6) |

| Demanding parenting | 1–4 | 3.3 (.6) | 3.1 (.7) |

| Self-reported electronic media use in hours per day | 0–24 | 8.9 (5.2) | 10.0 (5.7) |

| Stress | 1–4 | 2.7 (.9) | 2.9 (.8) |

| Grades | 1–4 | 3.3 (.7) | 3.0 (.6) |

| Depression | 1–4 | 1.7 (.7) | 1.8 (.7) |

| Self-esteem | 1–4 | 3.1 (.6) | 3.1 (.6) |

| Rebelliousness | 1–4 | 1.9 (.6) | 2.3 (.6) |

| Sensation seeking | 1–4 | 2.7 (.7) | 3.1 (.5) |

| Knowledge of harm and addictiveness of smoking | 1–5 | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.0) |

Number (%) for nominal variables; Mean (SD) for continuous variables.

This measure was used as a surrogate for socioeconomic status.

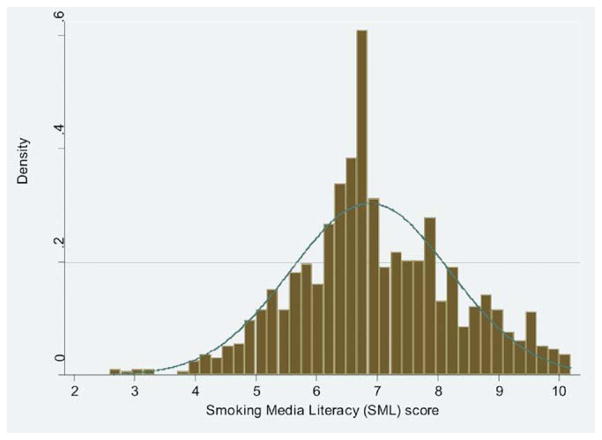

The mean SML score was 6.8 with a standard deviation of 1.3, and the scores followed a roughly normal distribution (Figure 1). As has been reported previously [24], in this sample SML was positively associated with socioeconomic status, responsive parenting, demanding parenting, and self-report of grades. It was negatively associated with rebelliousness and sensation-seeking. The level of SML was also lower in those with siblings, parents, and friends who smoke. With regard to the two primary outcome measures for this study, the SML score had a nearly linear relationship with each (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of smoking media literacy (SML) scores with overlaid normal curve.

Figure 2.

Association between smoking media literacy (SML) score and current smoking (top panel) and association between SML score and susceptibility to smoking (bottom panel) in adolescents. Data are based on raw scores in the 18-item SML scale, on self-report of current smoking (smoking in the past 30 days), and on responses to the three-item smoking susceptibility scale. Plots were created using LOWESS (locally-weighted scatter-plot smoothing) techniques in Stata 9.0.

In bivariate analyses, SML and the vast majority of the covariates were associated with the outcome of current smoking (Table 3). Only race, gender, and self-esteem were not significantly associated with current smoking. In multivariate analyses, we found an independent association between SML and current smoking (Table 3). A one-point decrease on the 10-point SML scale was associated with an odds ratio for smoking of .84 (95% CI .71–.99). Compared with individuals with SML below the median, the odds ratio for smoking for individuals with scores above the median of smoking was .57 (95% CI .37–.87).

Table 3.

Bivariate and multivariate relationships between predictors and current smokinga

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) for current smoking, bivariate | OR (95% CI) for current smoking, multivariate |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic | ||

| Age | 1.33 (1.17, 1.51)c | 1.34 (1.11, 1.62)c |

| Gender | 1.02 (.76, 1.38) | 1.14 (.73, 1.76) |

| African-American race | .43 (.15, 1.23) | .27 (.07, 1.10) |

| Other race | .97 (.44, 2.13) | .99 (.31, 3.13) |

| Parental educationb | .71 (.60, .83)c | .94 (.75, 1.18) |

| Environmental factor | ||

| Parent smoking | 2.86 (2.11, 3.88)c | 1.97 (1.28, 3.02)c |

| Sibling smoking | 3.58 (2.59, 4.95)c | 1.90 (1.21, 2.98)c |

| Friend smoking | 33.7 (15.7, 72.6)c | 13.33 (5.94, 29.9)c |

| Responsive parenting | .52 (.41, .66)c | 1.00 (.66, 1.51) |

| Demanding parenting | .48 (.38, .62)c | 1.16 (.79, 1.73) |

| Electronic media use | 1.05 (1.03, 1.08)c | 1.02 (.98, 1.06) |

| Stress | 1.44 (1.20, 1.73)c | 1.24 (.92, 1.66) |

| Intrinsic factor | ||

| Grades | .32 (.25, .42)c | .57 (.40, .82)c |

| Depression | 1.49 (1.22, 1.83)c | 1.04 (.75, 1.46) |

| Self-esteem | .88 (.68, 1.14) | .99 (.67, 1.46) |

| Rebelliousness | 4.77 (3.59, 6.33)c | 2.48 (1.63, 3.76)c |

| Sensation seeking | 3.47 (2.64, 4.56)c | 1.63 (1.08, 2.43)c |

| Knowledge of harm and addictiveness of smoking | .79 (.69, .92)c | .74 (.60, .91)c |

| SML leveld | ||

| SML as a continuous variable (1 point on a 10-point scale) | .68 (.60, .77)c | .84 (.71, .99)c |

| SML above median (vs below median) | .37 (.26, .51)c | .57 (.37, .87)c |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; SML = smoking media literacy.

Parental education was used as a surrogate for socioeconomic status.

Result is statistically significant (p < .05).

SML was measured in 3 different ways: as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable.

Several variables other than SML were also independently associated with current smoking. Better grades and higher knowledge of the harm and addictiveness of smoking had an independent inverse association with smoking (Table 3). Increasing age, parental smoking, sibling smoking, friend smoking, rebelliousness, and sensation-seeking all independently increased the odds ratio for smoking.

Analyses on susceptibility to smoking were performed only with students who were not current smokers, because this construct was validated in that population [28]. The majority of measured covariates had significant bivariate associations with susceptibility to smoking (Table 4). However, in multivariate models, only friend smoking, depression, self-esteem, rebelliousness, sensation-seeking, and SML retained independent associations with susceptibility to smoking. A one-point decrease on the 10-point SML scale was associated with an odds ratio for susceptibility to smoking of .68 (95% CI .58–.79). Compared with individuals with SML below the median, the odds ratio for susceptibility to smoking for individuals with scores above the median of smoking was .49 (95% CI .35–.68).

Table 4.

Bivariate and multivariate relationships between predictors and susceptibility to smokinga

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) for susceptibility to smoking, bivariate | OR (95% CI) for susceptibility to smoking, multivariate |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic | ||

| Age | 1.00 (.90, 1.11) | .91 (.79, 1.05) |

| Gender | .90 (.70, 1.17) | 1.12 (.78, 1.61) |

| African-American race | 1.11 (.58, 2.11) | .66 (.26, 1.68) |

| Other race | 1.41 (.70, 2.84) | 1.59 (.60, 4.18) |

| Parental educationb | 1.02 (.88, 1.17) | 1.10 (.91, 1.33) |

| Environmental factor | ||

| Parent smoking | 1.36 (1.03, 1.79)c | .92 (.64, 1.33) |

| Sibling smoking | 1.94 (1.39, 2.72)c | 1.14 (.73, 1.79) |

| Friend smoking | 4.28 (3.19, 5.73)c | 3.28 (2.30, 4.68)c |

| Responsive parenting | .61 (.48, .77)c | 1.15 (.79, 1.68) |

| Demanding parenting | .50 (.40, .64)c | .72 (.51, 1.03) |

| Electronic media use | 1.04 (1.01, 1.06) | 1.00 (.96, 1.03) |

| Stress | 1.07 (.92, 1.25) | 1.11 (.88, 1.40) |

| Intrinsic factor | ||

| Grades | .57 (.46, .71)c | .91 (.67, 1.23) |

| Depression | 1.05 (.87, 1.27) | .72 (.54, .96)c |

| Self-esteem | .63 (.50, .80)c | .54 (.39, .76)c |

| Rebelliousness | 2.72 (2.09, 3.53)c | 1.60 (1.09, 2.33)c |

| Sensation seeking | 2.25 (1.80, 2.81)c | 1.66 (1.22, 2.27)c |

| Knowledge of harm and addictiveness of smoking | 1.03 (.90, 1.16) | 1.00 (.85, 1.18) |

| SML leveld | ||

| SML as a continuous variable (1 point on a 10-point scale) | .64(.57, .71)c | .68 (.58, .79)c |

| SML above median (vs below median) | .42 (.32, .55)c | .49 (.35, .68)c |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; SML = smoking media literacy. For this analysis, the sample includes only those individuals who were not current smokers.

Parental education was used as a surrogate for socioeconomic status.

Result is statistically significant (p < .05).

SML was measured in two different ways: as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable.

Each of the final logistic regression models in which both current smoking and smoking susceptibility were used as dependent variables showed excellent ability to predict the outcomes with Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit testing and ROC curve analysis [34]. When data from all students were included (even from those whose data was eliminated from the final analysis because of having had poor data quality), the results were similar.

Discussion

In our analysis of surveys completed by adolescents in a large suburban high school, we found that higher levels of SML were independently associated with decreased odds ratios for current smoking and smoking susceptibility. In our logistic regression analysis, the association between smoking and SML scores was similar to the association between smoking and many other factors traditionally thought to be important predictors of smoking. Friend smoking, rebelliousness, and sensation-seeking were the only other variables independently associated with both current smoking and susceptibility to smoking. This may be particularly important because SML has been shown in other studies to be practical to teach [18,24,35], unlike characteristics such as rebelliousness and sensation-seeking.

Different methods of categorizing SML scores may be appropriate for different settings. In research settings, investigators may favor the analysis of scores as a continuous variable, because this will allow them to retain the most statistical information and make finer distinctions. In clinical settings, when encounters with patients are brief, however, it may not be feasible to determine a specific numerical SML score. It may be possible, however, to estimate whether an adolescent’s level of SML is high or low and then to counsel or intervene as appropriate. As the results of our study indicate, adolescents with SML above the median are about half as likely to smoke and to be susceptible to smoking as those with SML below the median, even when controlling for all measured covariates.

Because media messages have been shown to affect not only smoking behavior but also eating behavior, aggression, sexual behavior, and alcohol use [36–38], it may be useful to conduct similar studies to determine whether media literacy may also be useful in buffering harmful health behaviors other than smoking. Although it is important to continue to attempt to reduce the amount of exposure to potentially harmful media messages during adolescence, it is not always feasible to do so. Media literacy may therefore be a practical and empowering co-intervention.

Our study had several limitations that deserve mention. First, the study population was drawn from a single large high school. Although the adolescents in the study were homogeneous in terms of their racial and ethnic backgrounds, their baseline values for smoking and for susceptibility to smoking are, in fact, similar to values previously reported [28,39,40]. Nevertheless, our findings should be confirmed in more diverse populations. Second, although a cross-sectional study can show associations between SML and smoking, the more clinically relevant question would be whether individuals with different levels of SML will have different rates of initiating the use of cigarettes. This question could ideally be answered with a prospective cohort study, which would be the next logical step. Third, we relied on self-report of smoking, rather than biochemical verification of smoking. We did not verify smoking behavior, however, because of (1) the potential to introduce selection bias; (2) the fact that this would have necessitated active informed consent; and (3) the fact that only a very small proportion of the students were daily smokers in whom cotinine would be detected.

In summary, this study is the first of which we are aware that provides evidence for an independent association between smoking media literacy and both smoking behavior and susceptibility to future smoking among adolescents. Media literacy may therefore represent a promising tool for smoking prevention in this population.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Maurice Falk Foundation and Tobacco-Free Allegheny. Although each of these agencies provided financial support, they were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Fine was supported in part by a K-24 career development award from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (5K24 AI01769). Dr. Primack had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Tobacco Use among Young People, A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Trends in Initiation of Substance Abuse. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson AV, Jr, Kealey KA, Mann SL, et al. Hutchinson Smoking Prevention Project: long-term randomized trial in school-based tobacco use prevention—results on smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1979–91. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.24.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellickson PL, Bell RM, McGuigan K. Preventing adolescent drug use: long-term results of a junior high program. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:856–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flay BR, Koepke D, Thomson SJ, et al. Six-year follow-up of the first Waterloo school smoking prevention trial. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1371–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.10.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rideout V, Roberts D, Foehr U. Generation M: Media in the Lives of 8–18-Year-Olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dozier D, Lauzen M, Day C, et al. Leaders and elites: portrayals of smoking in popular films. Tob Control. 2005;14:7–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long JA, O’Connor PG, Gerbner G, Concato J. Use of alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco among characters on prime-time television. Subst Abus. 2002;23:95–103. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madden PA, Grube JW. The frequency and nature of alcohol and tobacco advertising in televised sports, 1990 through 1992. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:297–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, et al. Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: a cohort study. Lancet. 2003;362:281–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sargent JD, Beach ML, Dalton MA, et al. Effect of seeing tobacco use in films on trying smoking among adolescents: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001;323:1394–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, et al. Tobacco industry promotion of cigarettes and adolescent smoking. JAMA. 1998;279:511–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.7.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Rosbrook B. Are adolescents receptive to current sales promotion practices of the tobacco industry? Prev Med. 1997;26:14–21. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.9980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman DG, Levine DW, Coeytaux R, et al. Tobacco promotion and susceptibility to tobacco use among adolescents aged 12 through 17 years in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1590–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakefield MA, Ruel EE, Chaloupka FJ, et al. Association of point-of-purchase tobacco advertising and promotions with choice of usual brand among teenage smokers. J Health Commun. 2002;7:113–21. doi: 10.1080/10810730290087996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Media education. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Public Education. Pediatrics. 1999;104:341–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckingham D. Media Education: Literacy, Learning, and Contemporary Culture. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobbs R, Frost R. Measuring the acquisition of media-literacy skills. Read Res Q. 2003;38:330–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin EW, Johnson KK. Effects of general and alcohol-specific media literacy training on children’s decision making about alcohol. J Health Commun. 1997;2:17–42. doi: 10.1080/108107397127897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wade TD, Davidson S, O’Dea JA. A preliminary controlled evaluation of a school-based media literacy program and self-esteem program for reducing eating disorder risk factors. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33:371–83. doi: 10.1002/eat.10136. discussion 84–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voojis M, van der Voort T. Learning about television violence: the impact of a critical viewing curriculum on children’s attitudinal judgments of crime series. J Res Dev Educ. 1993;26:133–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Primack BA, Gold MA, Switzer GE, et al. Development and validation of a smoking media literacy scale. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:369–74. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MediaSharp: Analyzing Tobacco and Alcohol Messages. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Office of National Drug Control Policy. Helping Youth Navigate the Media Age: A New Approach to Drug Prevention. Washington, DC: Office of National Drug Control Policy; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin EW, Pinkleton BE, Hust SJT, Cohen M. Evaluation of an American Legacy Foundation/Washington State Department of Health Media Literacy Pilot Study. Health Commun. 2005;18:75–95. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1801_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, et al. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15:355–61. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee V. The Authoritative Parenting Index: predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25:319–37. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvajal S, Wiatrek D, Evans R, et al. Psychosocial determinants of the onset and escalation of smoking: cross-sectional and prospective findings in multiethnic middle school samples. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:255–65. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pierce J, Farkas A, Evans N. Tobacco Use in California 1992: A Focus on Preventing Uptake in Adolescents. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Human Services; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo M, Stokes G, Lahey B, et al. A sensation-seeking scale for children: further refinement and psychometric development. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1993;15:69–85. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metz C. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med. 1978;8:283–98. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(78)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hobbs R. Does media literacy work? An empirical study of learning how to analyze advertisements. Advert Soc Rev. 2004;5:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Primack B. Counseling patients on mass media and health. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:2545–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strasburger V, Donnerstein E. Children, adolescents, and the media in the 21st century. Adolesc Med. 2000;11:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villani S. Impact of media on children and adolescents: a 10-year review of the research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:392–401. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monitoring the Future. Monitoring the Future, Results from 2003. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buller DB, Borland R, Woodall WG, et al. Understanding factors that influence smoking uptake. Tob Control. 2003;12(suppl 4):IV16–IV25. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_4.iv16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]